Summary

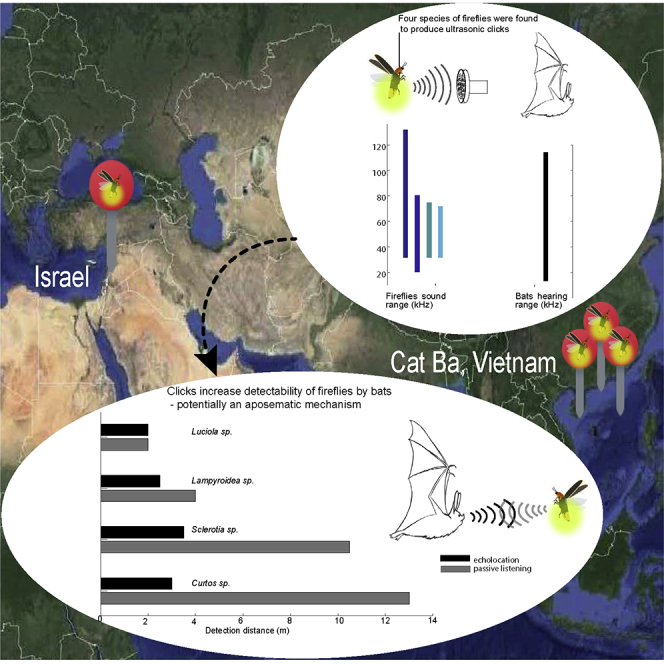

Fireflies are known for emitting light signals for intraspecific communication. However, in doing so, they reveal themselves to many potential nocturnal predators from a large distance. Therefore, many fireflies evolved unpalatable compounds and probably use their light signals as anti-predator aposematic signals. Fireflies are occasionally attacked by predators despite their warning flashes. Bats are among the most substantial potential firefly predators. Using their echolocation, bats might detect a firefly from a short distance and attack it in between two flashes. We thus aimed to examine whether fireflies use additional measures of warning, specifically focusing on sound signals. We recorded four species from different genera of fireflies in Vietnam and Israel and found that all of them generated ultrasonic clicks centered around bats' hearing range. Clicks were synchronized with the wingbeat and are probably produced by the wings. We hypothesize that ultrasonic clicks can serve as part of a multimodal aposematic display.

Subject areas: environmental science, ecology, biological sciences, zoology, ethology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Fireflies of four genera were found to produce ultrasonic clicks during flight

-

•

The clicks were synchronized with the wingbeats

-

•

Clicks increase detectability of fireflies by bats

-

•

The signals can potentially serve as a part of multimodal aposematic display

Environmental science; ecology; biological sciences; zoology; ethology

Introduction

Sexual signaling often increases predation risk. Although salient communication signals promote higher mating success, they might also assist predators or parasites who learn to eavesdrop on these signals to locate their prey or host (Zuk and Kolluru, 1998). The evolution of such signals is, thus, a trade-off between these two pressures. In many cases, predators evolve highly specialized sensory systems to enhance the detectability of prey communication signals (Arthur and Hoy, 2006) imposing a serious cost on their broadcast (Halfwerk et al., 2014). When the potential prey is unpalatable, however, it might evolve intra-species communication signals irrespective of the predator's sensing abilities, and under certain circumstances, it might even adapt its signals to advertise its unpalatability to potential predators (Rojas et al., 2018)

This is probably the case with fireflies, which are unpalatable or even noxious to predators (de Cock and Matthysen, 2001, 2003; Eisner et al., 1978; Fu et al, 2006, 2007; Knight et al., 1999; Long et al., 2012; Underwood et al., 1997; Vencl et al., 2016), and use bioluminescent light signals for intersexual communication (Demary et al., 2006; Forrest and Eubanks, 1995). When emitting light signals at night, fireflies expose themselves to a high risk of predation by various nocturnal predators including some bats, which, in contrast to the common belief, often rely on vision in many of their activities (Boonman et al., 2013; Danilovich et al., 2015). Previous studies suggested that firefly bioluminescence serves as an anti-bat aposematic advertisement in addition to its role in attracting mates (Goldman and Henson, 1977; Moosman et al., 2009), and a recent study showed that bats can learn to associate firefly bioluminescence with their noxiousness (Leavell et al., 2018). Some studies even suggest that bioluminescence evolved as an anti-predatory signal mechanism first (Branham and Wenzel, 2003; Martin et al., 2017).

However, light flashing might not be enough to prevent a bat from an attack. Some bats have poor vision (Bell and Fenton, 1986; Boonman et al., 2013; (Suthers et al., 1969)), and from some angles, the flash of the firefly might be missed. Moreover, fireflies' flight speed is low, and their flashing rate can sometimes be as slow as once every 7 s (Charles and Snyder, 1920). When also considering the short detection range enabled by echolocation, and the very rapid nature of bat attacks (Kalko, 1995; Schnitzler et al, 1987, Schnitzler et al., 1988; Vanderelst and Peremans, 2018), a bat might occasionally intercept a firefly with a blink of an eye (in between two flashes). Indeed, because of such identification mistakes, defense displays in nature evolve multimodal patterns, increasing their reception by a potential predator. For example, many diurnal insects combine distinct coloration with various sounds to deter predators (Rowe and Halpin, 2013). We thus hypothesized that fireflies might signal their noxiousness using more than only light. Specifically, we examined whether they also produce sounds that could be detected by bats. We examined both males and females of species of three genera of fireflies (Sclerotia, Curtos, and Luciola) common in Cát Bà, Vietnam. We recorded them in flight and tested their behavioral response to ultrasonic playbacks of bat echolocation calls. We found that all three species constantly produced click sounds during flight centered at bats' hearing range (Heffner et al, 2003, 2013; Koay et al, 1998, 2002, 2003; (Moss and Schnitzler, 1995)) in synchrony with their wingbeats. To examine the generality of the phenomenon, we also recorded a species common to Israel (genus Lampyroidea) and found that it too produces sound clicks in flight. We hypothesize that these sounds can be learned by bats and serve as an additional aposematic signal.

Results

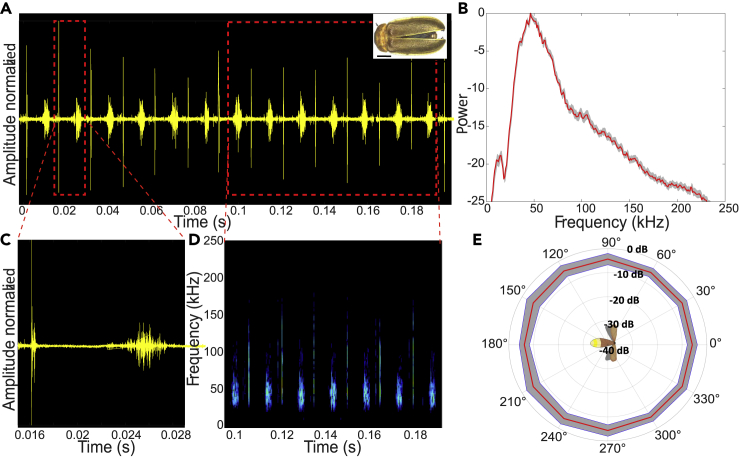

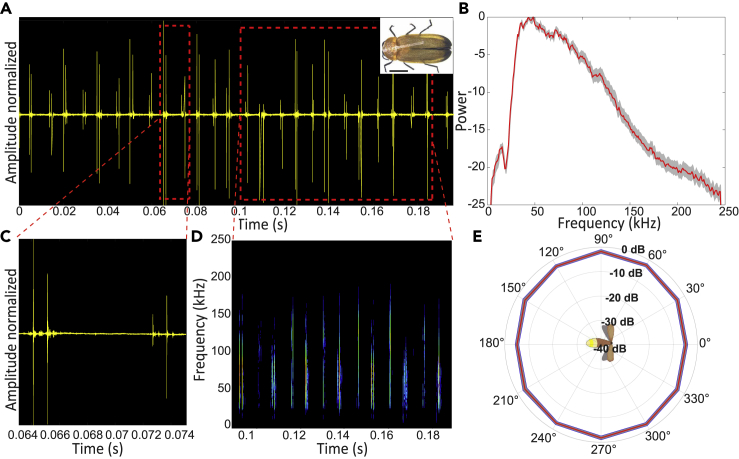

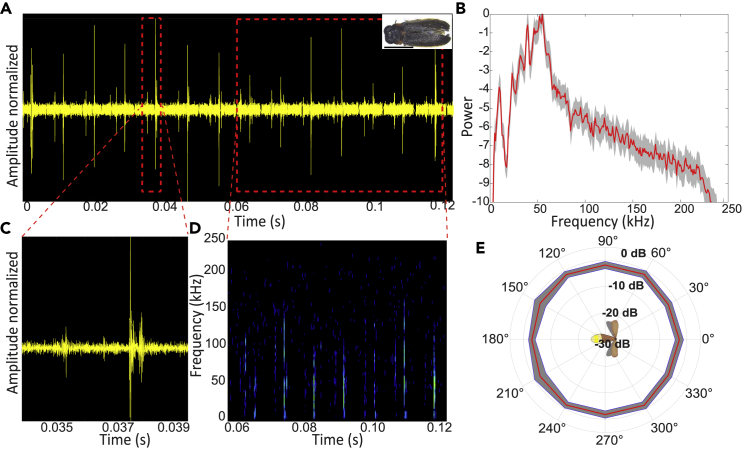

The reported experiment was performed on tethered fireflies. Initial recordings, though, were performed in a box with freely-flying (non-tethered) fireflies and also revealed clicking so that the recorded clicks were not an artifact of the tether. All Four species of fireflies that we examined produced ultrasonic clicks in tethered flight (see Figures 1, 2, 3 (see Figure S4 for setup), and Figure S1). The frequency range of the clicks ranged between 20 and 130 kHz (Figures 1, 2, 3A–3D, and S1) with peak frequencies between 40 and 50 kHz (see Table 1 for the exact frequencies). These peak frequencies overlap with the prime hearing sensitivity of a substantial proportion of bat species ((Jakobsen et al., 2013)). The intensity of the clicks at 1 m distance was similar in the two larger Sclerotia and Curtos species (59- and 60-dB SPL, respectively), but substantially weaker in the smaller Luciola and Lampyroidea species (25 and 37 dB SPL, respectively). All the SPL values were measured peak to peak. We were able to record from both sexes in two of the four species (females of Lampyroidea are not airborne) and found that males and females produced signals with roughly the same power density profile (Figures S2 and S3), suggesting that these signals are not used in courtship behavior.

Figure 1.

Acoustic characteristics of Sclerotia

All panels show data for the first most intense click.

(A) The waveform of the clicks. Right upper corner: photograph of the specimen. Scale bar, 2 mm.

(B) Average power spectrum of both (higher and lower clicks), mean (red) ± SE (gray).

(C) Zoom-in on one pair of clicks.

(D) Spectrogram of the signal.

(E) Beam directionality analysis reveals that the beams are omnidirectional in the horizontal plain, mean (red) ± SD (gray). Intensity values were measured for the most intense frequency at a 17 cm distance.

Figure 2.

Acoustic characteristics of Сurtos

All panels show data for the first most intense click.

(A) The waveform of the clicks. Right upper corner: photograph of the specimen. Scale bar, 2 mm.

(B) Average power spectrum of both (higher and lower clicks), mean (red) ± SE (gray).

(C) Zoom-in on one pair of clicks.

(D) Spectrogram of the signal.

(E) Beam directionality analysis reveals that the beams are omnidirectional in the horizontal plain, mean (red) ± SD (gray). Intensity values were measured for the most intense frequency at a 17 cm distance.

Figure 3.

Acoustic characteristics of Luciola

All panels show data for the first most intense click.

(A) The waveform of the clicks. Right upper corner: photograph of the specimen. Scale bar, 2 mm.

(B) Average power spectrum of both (higher and lower clicks), mean (red) ± SE (gray).

(C) Zoom-in on one pair of clicks.

(D) Spectrogram of the signal.

(E) Beam directionality analysis reveals that the beams are omnidirectional in the horizontal plain, mean (red) ± SD (gray). Intensity values were measured for the most intense frequency at a 2 cm distance.

Table 1.

Summary of acoustic analyses for four species of fireflies

| Species | Sclerotia | Curtos | Luciola | Lampyroidea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firefly wing length (mm) | ∼9 | ∼6 | ∼3 | ∼5 |

| Sound intensity (dB SPL re1m) | 59 ± 2.8 (n = 6) | 60 ± 5.7 (n = 5) | 25 ± 2.7 (n = 5) | 37 ± 2.6 (n = 4) |

| Peak frequency (kHz) | 50 ± 5.3 (n = 6) | 50 ± 5.4 (n = 5) | 50 ± 6.5 (n = 5) | 50 ± 5.8 (n = 4) |

| Low frequency (kHz) | 30 ± 12.7 (n = 6) | 30 ± 9 (n = 5) | 20 ± 10 (n = 5) | 30 ± 3.9 (n = 4) |

| High frequency (kHz) | 70 ± 8.8 (n = 6) | 130 ± 5.3 (n = 5) | 80 ± 8.8 (n = 5) | 73 ± 4 (n = 4) |

| Clicking rate (Hz) | 139 ± 7.3 (n = 5) | 142 ± 14 (n = 5) | 106 ± 7.3 (n = 5) | 67 ± 7 (n = 4) |

| Wing fluttering frequency (Hz) | 69 ± 5.6 (n = 3) | 71 ± 1.1 (n = 3) | 107 ± 4.4 (n = 1) | 72 ± 4.6 (n = 3) |

Mean ± SD, n = number of sampled individuals.

High and low frequencies were defined by a drop of 6 dB relative to the frequency with maximum energy.

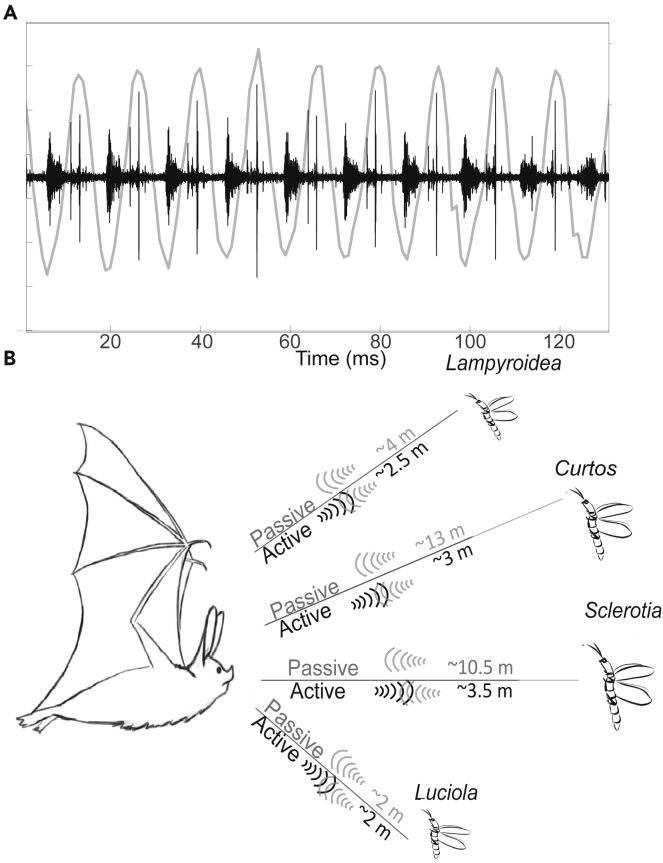

The fireflies' clicking rate was very similar to the rate of their wingbeat, suggesting that clicks are produced by the wings (Figure 4A and see Video S1). In the two larger species, the rate of the clicks was twice higher than the wingbeat rate, with one of the clicks being quieter and slightly different in spectrum than the other (suggesting that they are produced by different parts of the wingbeat cycle). In the two smaller species the rate of clicks was roughly the same as the wingbeat rate.

Figure 4.

Click and wingbeat synchronization and click detection range

(A) Synchronization of wing movement and clicks. Wing positions are depicted by gray line: high points for wings in the upstroke positions, low points for wings in the downstroke positions. Clicks' waveforms are depicted by black line. Because our high-speed imaging and sound recordings were not synchronized, the two lines can be out of phase, but the rates are correct.

(B) The schematic describes the maximal detection range of the fireflies by a bat when relying on passive hearing of the clicks or active echolocation, This was estimated for a bat emitting a call with an intensity of 110 dB SPL (Re 1m). Estimated detection distances for 120 dB SPL are 5.1 ± 0.32 m for Sclerotia, 4.66 ± 0.3 m for Curtos, 3 ± 0.2 m for Luciola, and 3.8 ± 0.25 m for Lampyroidea.

Filming rate is 960 Hz. Sound is not synchronized but slowed down to a similar speed. The gray line on the left is an audio spectrum.

An analysis of the directionality of the emission (Figures 1, 2, and 3E) showed that the click sounds spread in all directions almost equally. Therefore, bats should be able to hear the fireflies from a similar distance from all directions (at least in the horizontal plane). We estimated the maximum distances over which a bat could detect these fireflies based on their clicking to be ∼13.0 ± 2.2 m for Curtos and ∼10.5 ± 1.4 m for Sclerotia, but only ∼2.1 ± 0.4 m and 3.8 ± 0.65 m for Luciola and Lampyroidea, respectively. We also estimated the range from which a bat could detect them actively—using its echolocation—and found it to be ∼3.3 ± 0.2 m for Sclerotia, ∼3.0 ± 0.2 m for Curtos, ∼1.9 ± 0.1 m for Luciola, and 2.4 ± 0.2 for Lampyroidea (Figure 4B). Active detection ranges were estimated assuming a 110 dB dynamic range for the echolocation system (Methods). When assuming a 120 dB range, detection distances increased to 5.1 ± 0.3 m for Sclerotia, 4.6 ± 0.3 m for Curtos, 3.0 ± 0.2 m for Luciola, and 3.8 ± 0.25 for Lampyroidea (Figure 4B: mean ± standard deviation for all of the above).

Fireflies are not known to possess tympanic or other ultrasound-sensitive ears. Moreover, a careful examination of the fireflies we studied did not reveal ear-like structure in either of the three species. To further examine their ability to hear ultrasound, we performed several tests (on the three species from Vietnam). (1) We examined whether a non-flying firefly initiates flight or flashing in response to a loud playback (ca.70 dB SPL) of an approaching bat. (2) We tested whether a tethered flying firefly changes the characteristics of the sound it produces in the presence of the same playback. Bats typically emit calls at an intensity range of 130–110 dB SPL (Re 10 cm) ((Jakobsen et al., 2013)). Note that our playback is equivalent to a bat emitting at 130 dB SPL at a distance of ∼11.5 m from the firefly. For a bat emitting at 110 dB SPL the distance would be ∼4.5 m from the firefly. (3) We also observed the flying fireflies and looked for any behavioral indication that they can hear the sounds, such as changes in flashing rate or in posture and movement of legs or antennae (such as the ones described in [Yager and Spangler, 1997]). The fireflies of all three species showed no response in any of these tests, strongly suggesting that they cannot hear bats (and their own clicks). The intensity and the power spectrum of the clicks recorded during the bat playbacks also did not change significantly in the presence of bats' echolocation playback (Figures S2 and S3).

Discussion

In this study we show that fireflies (of four different genera) produce ultrasonic clicks during flight. Behavioral experiments imply that the fireflies are not sensitive to these signals, and thus they cannot serve for intra-specific communication. The main question is whether wing clicking evolved in fireflies, and more specifically, whether it evolved as an anti-bat aposematic signal? Clearly, we cannot fully answer this question without experiments that show that these clicks indeed deter bats. We cannot exclude, for example, that the clicks are an artifact of the wingbeating during flight. However, in the following paragraphs, we will discuss whether they could have evolved as aposematic signals.

Such ultrasonic clicks can be relatively easy to produce using a stridulation mechanism, for example, at the base of the wing. All firefly species that we examined clicked, and we hypothesize that most (if not all) firefly species click. Similar clicks are produced by many insects (not necessarily by the wings) for means of communication, including many species of beetles (Alexander et al., 1963; Barbero et al., 2009; Buchler et al., 1981; Conner and Corcoran, 2012; Corcoran and Hristov, 2014; Lyal and King, 1996). Some moths even evolved sound production mechanisms to disrupt bat echolocation (Corcoran et al., 2010; Corcoran and Hristov, 2014; Dunning and Roeder, 1965; M0hl and Miller, 1976; O'Reilly et al., 2019; ter Hofstede and Ratcliffe, 2016). Although most moths do not produce wingbeat clicks in flight, some noxious moths have evolved clicking probably as an aposematic mechanism (Corcoran et al., 2010; Corcoran and Hristov, 2014; Dunning and Roeder, 1965; Hristov and Conner, 2005; M0hl and Miller, 1976; O'Reilly et al., 2019; Rydell, 1998; ter Hofstede and Ratcliffe, 2016). Interestingly, the firefly clicks have hardly any energy below 20 kHz. Most stridulation mechanisms would generate wide band clicks with energy in audible frequencies too, so this high-frequency spectrum points toward a role of evolution. As most fireflies are noxious, if clicking evolved as an aposematic signal, it can be considered as a form of Müllerian mimicry where one species enjoys protection thanks to an encounter of the predator with another species.

If these clicks are indeed aposematic signals, why should fireflies evolve another warning signal considering their highly visible bioluminescence signals? There are several possible answers. (1) Fireflies sometimes do not emit light while flying, for example, when they fly in relatively high illumination (Firebaugh and Haynes, 2019). (2) Fireflies inter-flash interval vary between species and can sometimes be as long as 7 s (Ballantyne et al., 2013; Lloyd et al., 1989), depending on the temperature. Some studies also report lower flashing rates during flight than while perching. As explained earlier, such long intervals might result in a misidentification of the visual signal, by the hunting bats. Moreover, some bats indeed have poor vision and might miss the flashing. (3) Finally, many moths are known to signal their noxiousness using ultrasonic clicks with similar spectral characteristics (ter Hofstede and Ratcliffe, 2016). This includes moths that cannot hear bats, as has been recently shown (O'Reilly et al., 2019). Bats are known to avoid clicking moths (M0hl and Miller, 1976; ter Hofstede and Ratcliffe, 2016), so producing moth-like clicks (even if in a different rate) might assist fireflies to avoid predation through the act of inter-specific Mullerian mimicry.

In moths that produce aposematic clicks, it has been hypothesized that bats' detection range of these sounds should not surpass the detection range of their active echolocation (O'Reilly et al., 2019). It has been suggested that if this is not the case, bats could use the aposematic sounds emitted by these insects to localize them. In our study, the intense sounds produced by fireflies from the Sclerotia and Curtos genera enable bats to detect them from much farther than with echolocation. This was the case even though we assumed maximum insect reflectivity, which occurs when the wings are spread perpendicular to the sound wave. One explanation for these results is that the visual detection range of fireflies is mostly even larger than the acoustic detection range (depending on the visual system of the bat) so there is no point in “hiding” acoustically.

Even though all four species clicked, there were species-specific differences. The sound intensity of the two larger fireflies (Sclerotia and Curtos genera) were profoundly louder than those of the other two species. This could be an artifact of their size difference. It could also be an evolutionary outcome resulting from the difference in their active echolocation-based detection range (Figure 4B). Alternatively, the less-intense clicks could have evolved to match their different behavior. We hardly detected Luciola fireflies flying in the open. They were usually detected in stone crevices, in tall grass, or in tree crowns. Moreover, their flashing rate was rather high and constant, and they were usually observed in aggregations, probably lowering the significance of sound clicks as an aposematic mechanism.

The evolution of predator-prey communication is fascinating, with unpalatable prey evolving various multimodal measures of display. If ultrasonic clicks are indeed aposematic, then the combination of light flashes with ultrasonic clicks make fireflies' multimodal display of aposematism remarkably complex. Indeed, fireflies seems to avoid predation as revealed by several examinations of bat fecal pellets (the bats did consume firefly-sized beetles) (Goiti et al., 2003). Such a multimodal warning display could also assist bats' learning, helping them to distinguish truly unwanted targets from those displaying a Batesian mimicry. Additional research should focus on whether bats are deterred by these ultrasonic clicks and if so, on how they weigh different aposematic cues. All evidence suggests that fireflies cannot hear the clicks they produce. The idea of signals that cannot be sensed by their sender is intriguing. This is of course common in plants (Primack, 1982), but to our knowledge very rare in the animal kingdom.

Limitations of the study

The article has two main limitations that require further research:

-

1

.We did not perform behavioral experiments to show that firefly clicking sounds deter echolocating bats. Such experiments would be necessary to demonstrate the aposematic function of these signals.

-

2.

We did not fully clarify the sound production mechanisms of the clicks.

Both of these are needed to better understand the evolution of the clicks.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Yossi Yovel (yossiyovel@gmail.com).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

Original data have been deposited to Mendeley Data http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/r3hybw89zz.1

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying transparent methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank Associate Prof. Nguyen Thi Phuong Lien, Tran Thi Ngat, Ariel-Leib-Leonid Friedman, Ella Fishman, Itai Bloch, Dr. Gal Ribak, Y. Mersman, Oz Rittner, and Prof. Amir Ayali for their help in defining the genera of the fireflies and for looking into the existence of ear-like structures in the beetles. V.D.T. was funded by Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED) under grant number 106.05-2017.35. The work was supported by the University of Tuebingen and the Reinhard-Frank Stiftung. We thank H.-U. Schnitlzer, A. Denzinger, C. Moss, and the other members of the Animal Communication Course for helpful suggestions.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y; Methodology, Y.Y; Software, Y.Y., K.K., and A.B.; Formal Analysis, K.K. and A.B; Investigation, Y.Y, K.K., A.G, A.B., O.E., and J.B.-S.; Writing – Original Draft, Y.Y. and K.K.; Writing – Review & Editing, Y.Y. and K.K.; Project Administration, V.D.T.; Funding Acquisition, Y.Y. and V.D.T.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: March 19, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102194.

Supplemental information

References

- Alexander R.D., Moore T.E., Woodruff R.E. The evolutionary differentiation of stridulatory signals in beetles (Insecta: Coleoptera) Anim. Behav. 1963;11:111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur B.J., Hoy R.R. The ability of the parasitoid fly Ormia ochracea to distinguish sounds in the vertical plane. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2006;120:1546–1549. doi: 10.1121/1.2225936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne L., Fu X., Lambkin C., Jeng M.L., Faust L., Wijekoon W.M.C.D., Li D., Zhu T. Studies on South-east Asian fireflies: Abscondita, a new genus with details of life history, flashing patterns and behaviour of Abs. chinensis (L.) and Abs. terminalis (Olivier) (Coleoptera: lampyridae: Luciolinae. Zootaxa. 2013;3721:1–48. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3721.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbero F., Thomas J.A., Bonelli S., Balletto E., Schönrogge K. Queen ants make distinctive sounds that are mimicked by a butterfly social parasite. Science. 2009;323:782–785. doi: 10.1126/science.1163583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell G.P., Fenton M.B. Visual acuity, sensitivity and binocularity in a gleaning insectivorous bat, Macrotus californicus (Chiroptera: phyllostomidae) Anim. Behav. 1986;34:409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Boonman A., Bar-On Y., Yovel Y., Cvikel N. It’s not black or white—on the range of vision and echolocation in echolocating bats. Front. Physiol. 2013;4:248. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branham M.A., Wenzel J.W. The origin of photic behavior and the evolution of sexual communication in fireflies (Coleoptera: lampyridae) Cladistics. 2003;19:1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2003.tb00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchler E.R., Wright T.B., Brown E.D. On the functions of stridulation by the passalid beetle Odontotaenius disjunctus (Coleoptera: passalidae) Anim. Behav. 1981;29:483–486. [Google Scholar]

- Conner W.E., Corcoran A.J. Sound strategies: the 65-million-year-old battle between bats and insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2012;57:21–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-121510-133537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran A.J., Conner W.E., Barber J.R. Anti-bat tiger moth sounds: form and function. Curr. Zoolog. 2010;56:358–369. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran A.J., Hristov N.I. Convergent evolution of anti-bat sounds. J. Comp. Physiol. A. 2014;200:811–821. doi: 10.1007/s00359-014-0924-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles D., Snyder A.v. ’t H. The flashing interval of fireflies—its temperature coefficient—an explanation of synchronous flashing. Am. J. Physiol. 1920;51:536–542. [Google Scholar]

- Danilovich S., Krishnan A., Lee W.J., Borrisov I., Eitan O., Kosa G., Moss C.F., Yovel Y. Bats regulate biosonar based on the availability of visual information. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:R1124–R1125. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cock R., Matthysen E. Glow-worm larvae bioluminescence (Coleoptera: lampyridae) operates as an aposematic signal upon toads (Bufo bufo) Behav. Ecol. 2003;14:103–108. [Google Scholar]

- de Cock R., Matthysen E. Do glow-worm larvae (Coleoptera: lampyridae) use warning coloration? Ethology. 2001;107:1019–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Demary K., Michaelidis C.I., Lewis S.M. Firefly courtship: behavioral and morphological predictors of male mating success in photinus greeni. Ethology. 2006;112:485–492. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning D.C., Roeder K.D. Moth sounds and the insect-catching behavior of bats. Science. 1965;147:173–174. doi: 10.1126/science.147.3654.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner T., Wiemer D.F., Haynes L.W., Meinwald J. Lucibufagins: defensive steroids from the fireflies Photinus ignitus and P. marginellus (Coleoptera: lampyridae) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1978;75:905–908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.2.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firebaugh A., Haynes K.J. Light pollution may create demographic traps for nocturnal insects. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2019;34:118–125. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest T.G., Eubanks M.D. Variation in the flash pattern of the firefly, photuris versicolor quadrifulgens 1 (Coleoptera: lampyridae) J. Insect Behav. 1995;8:33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Fu X., Nobuyoshi O., Meyer-Rochow V.B., Wang Y., Lei C. Reflex-bleeding in the firefly pyrocoelia pectoralis (Coleoptera: lampyridae): morphological basis and possible function. Coleopt. Bull. 2006;60:207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Fu X., Vencl F.v., Nobuyoshi O., Meyer-Rochow V.B., Lei C., Zhang Z. Structure and function of the eversible glands of the aquatic firefly Luciola leii (Coleoptera: lampyridae) Chemoecology. 2007;17:117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Goiti U., Vecin P., Garin I., Saloña M., Aihartza J.R. Diet and prey selection in Kuhl’s pipistrelle Pipistrellus kuhlii (Chiroptera: vespertilionidae) in south-western Europe. Acta Theriol. 2003;48:457–468. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman L.J., Henson O.W. Prey recognition and selection by the constant frequency bat, Pteronotus P. Parnellii. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1977;2:411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Halfwerk W., Dixon M.M., Ottens K.J., Taylor R.C., Ryan M.J., Page R.A., Jones P.L. Risks of multimodal signaling: bat predators attend to dynamic motion in frog sexual displays. J. Exp. Biol. 2014;217:3038–3044. doi: 10.1242/jeb.107482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner R.S., Koay G., Heffner H.E. Hearing in American leaf-nosed bats. IV: the Common vampire bat, Desmodus rotundus. Hearing Res. 2013;296:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner R.S., Koay G., Heffner H.E. Hearing in American leaf-nosed bats. III: Artibeus jamaicensis. Hearing Res. 2003;184:113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristov N.I., Conner W.E. Sound strategy: acoustic aposematism in the bat-tiger moth arms race. Naturwissenschaften. 2005;92:164–169. doi: 10.1007/s00114-005-0611-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen L., Brinkløv S., Surlykke A. Intensity and directionality of bat echolocation signals. Front. Physiol. 2013;4:89. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalko E.K.V. Insect pursuit, prey capture and echolocation in pipestirelle bats (Microchiroptera) Anim. Behav. 1995;50:861–880. [Google Scholar]

- Knight M., Glor R., Smedley S.R., González A., Adler K., Eisner T. Firefly toxicosis in lizards. J. Chem. Ecol. 1999;25:1981–1986. [Google Scholar]

- Koay G., Bitter K.S., Heffner H.E., Heffner R.S. Hearing in American leaf-nosed bats. I: Phyllostomus hastatus. Hearing Res. 2002;171:96–102. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koay G., Heffner R.S., Bitter K.S., Heffner H.E. Hearing in American leaf-nosed bats. II: Carollia perspicillata. Hearing Res. 2003;178:27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koay G., Heffner R.S., Heffner H.E. Hearing in a megachiropteran fruit bat (rousettus aegyptiacus) J. Comp. Psychol. 1998;112:371–382. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.112.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavell B.C., Rubin J.J., McClure C.J.W., Miner K.A., Branham M.A., Barber J.R. Fireflies thwart bat attack with multisensory warnings. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:eaat6601. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat6601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd J.E., Wing S.R., Hongtrakul T. Flash behavior and ecology of Thai Luciola fireflies (Coleoptera: lampyridae) Fla. Entomol. 1989;72:80. [Google Scholar]

- Long S.M., Lewis S., Jean-Louis L., Ramos G., Richmond J., Jakob E.M. Firefly flashing and jumping spider predation. Anim. Behav. 2012;83:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lyal C.H.C., King T. Elytro-tergal stridulation in weevils (insecta: Coleoptera: curculionoidea) J. Nat. Hist. 1996;30:703–773. [Google Scholar]

- M0hl B., Miller L.A. Ultrasonic clicks produced by the peacock butterfly: a possible bat-repellent Mechanism. J. Exp. Biol. 1976;64:639–644. [Google Scholar]

- Martin G.J., Branham M.A., Whiting M.F., Bybee S.M. Total evidence phylogeny and the evolution of adult bioluminescence in fireflies (Coleoptera: lampyridae) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2017;107:564–575. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosman P.R., Cratsley C.K., Lehto S.D., Thomas H.H. Do courtship flashes of fireflies (Coleoptera: lampyridae) serve as aposematic signals to insectivorous bats? Anim. Behav. 2009;78:1019–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Moss S.F., Schnitzler H.U. Behavioral studies of auditory information processing. In: Popper A.N., Fay R.R., editors. Hearing by Bats. Springer; 1995. pp. 87–145. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly L.J., Agassiz D.J.L., Neil T.R., Holderied M.W. Deaf moths employ acoustic Müllerian mimicry against bats using wingbeat-powered tymbals. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37812-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack R.B. Ultraviolet patterns in flowers, or flowers as viewed by insects. Arnoldia. 1982;42:139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas B., Burdfield-Steel E., de Pasqual C., Gordon S., Hernández L., Mappes J., Nokelainen O., Rönkä K., Lindstedt C. Multimodal aposematic signals and their emerging role in mate attraction. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018;6:93. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe C., Halpin C. Why are warning displays multimodal? Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2013;67:1425–1439. [Google Scholar]

- Rydell J. Bat defence in lekking ghost swifts (Hepialus humuli), a moth without ultrasonic hearing. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 1998;265:1373–1376. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler H.U., Kalko E., Miller L., Surlykke A. The echolocation and hunting behavior of the bat, Pipistrellus kuhli. J. Comp. Physiol. A. 1987;161:267–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00615246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler H.-U., Kalko E., Miller L., Surlykke A. How the bat, Pipistrellus kuhli, hunts for insects. In: Nachtigall P.E., Moore P.W.B., editors. Animal Sonar. Springer US; 1988. pp. 619–623. [Google Scholar]

- Suthers R., Chase J., Braford B. Visual form discrimination by echolocating bats. Biol Bull. 1969;137:535–546. doi: 10.2307/1540174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Hofstede H.M., Ratcliffe J.M. Evolutionary escalation: the bat-moth arms race. J. Exp. Biol. 2016;219:1589–1602. doi: 10.1242/jeb.086686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood T.J., Tallamy D.W., Pesek J.D. Bioluminescence in firefly larvae: a test of the aposematic display hypothesis (Coleoptera: lampyridae) J. Insect Behav. 1997;10:365–370. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderelst D., Peremans H. Modeling bat prey capture in echolocating bats: the feasibility of reactive pursuit. J. Theor. Biol. 2018;456:305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2018.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vencl F.v., Ottens K., Dixon M.M., Candler S., Bernal X.E., Estrada C., Page R.A. Pyrazine emission by a tropical firefly: an example of chemical aposematism? Biotropica. 2016;48:645–655. [Google Scholar]

- Yager D.D., Spangler H.G. Behavioral response to ultrasound by the tiger beetle Cicindela marutha dow combines aerodynamic changes and sound production. J. Exp. Biol. 1997;200:649–659. doi: 10.1242/jeb.200.3.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuk M., Kolluru G.R. Exploitation of sexual signals by predators and parasitoids. Q. Rev. Biol. 1998;73:415–438. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Filming rate is 960 Hz. Sound is not synchronized but slowed down to a similar speed. The gray line on the left is an audio spectrum.

Data Availability Statement

Original data have been deposited to Mendeley Data http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/r3hybw89zz.1