Abstract

Objectives:

Roughly 6.5 million U.S. residents engaged in prescription tranquilizer/sedative (e.g., benzodiazepines, Z-drugs) misuse in 2018, but tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives are understudied, with a need for nationally representative data and examinations of motives by age group. Our aims were to establish tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives and correlates of motives by age cohort, and whether motive-age cohort interactions existed by correlate.

Methods:

Data were from the 2015-18 U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, with 223,520 total respondents (51.5% female); 6,580 noted past-year prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives (2.4% overall, 50.3% female). Correlates included substance use (e.g., opioid misuse), mental (e.g., suicidal ideation) and physical health variables (e.g., inpatient hospitalization). Design-based, weighted cross-tabulations and logistic regression analyses were used, including analyses of age cohort-motive interactions for each correlate.

Results:

Prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives varied by age group, with the highest rates of self-treatment only motives (i.e., sleep and/or relax) in those 65 and older (82.7%), and the highest rates of any recreational motives in adolescents (12-17 years; 67.5%). Any tranquilizer/sedative misuse was associated with elevated odds of substance use, mental health, and physical health correlates, but recreational misuse was associated with the highest odds. Age-based interactions suggested stronger relationships between tranquilizer/sedative misuse and mental health in adults 50 and older.

Conclusions:

Any tranquilizer/sedative misuse signals a need for substance use and mental health screening, with intervention needs most acute in those with any recreational motives. Older adult tranquilizer/sedative misuse may be more driven by undertreated insomnia and anxiety/psychopathology than in younger groups.

Keywords: anti-anxiety agents, benzodiazepines, hypnotics and sedatives, prescription misuse, motives

INTRODUCTION

Prescription tranquilizer and/or sedative misuse is medication use without a prescription or use of one’s own prescription in ways not intended by the prescriber1 of sedative-hypnotic and anxiolytic medications (e.g., benzodiazepine, Z-drug, and barbiturate medications). Prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse is relatively common in United States (U.S.) residents, with nearly 6.5 million engaged in past-year misuse in 2018.2 Past-year tranquilizer/sedative misuse prevalence trails only alcohol, nicotine, marijuana, and prescription opioid misuse,3 with the highest rates in young adults (18-25 years) at 4.9%.2

Prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse is also associated with significant consequences. Rates of benzodiazepine-involved overdose increased by 65% from 2010 to 2018 in U.S. residents, and roughly 20% of opioid-involved overdoses in 2018 involved benzodiazepines. In older adults, Beers Criteria guidelines recommend against the use of benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and Z-drugs because of increased rates of falls and other accidents, cognitive and memory impairments, and overdose at relatively low doses.4 Beyond overdose, tranquilizer/sedative misuse is associated with concerning correlates, including other substance use, substance use disorders (SUD), psychiatric comorbidities, and lower educational attainment.3,5-9 In all, the prevalence, consequences, and correlates of tranquilizer/sedative misuse across the population are relatively well understood.

Much less research, however, has examined motives for tranquilizer/sedative misuse. Motives are a potentially modifiable factor that could direct screening and intervention to limit prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse. To illustrate, interventions for alcohol use that target motives are associated with significant use reductions,10,11 and cannabis use motives change in tandem with use patterns.12 As noted by Votaw and colleagues,3 the most common motives for tranquilizer/sedative misuse encompass self-treatment, primarily a desire to promote sleep and/or reduce anxiety. Recreational motives, such as to get high or experiment, also are common, and most studies associate recreational motives with a greater likelihood of other substance use, SUD, and psychiatric comorbidities.3 Limitations of studies of tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives include concentration on one age group, typically adolescents13,14 or young adults,15,16 use of local samples across adults,17,18 or focus on individuals with opioid use disorder.19,20

To the best of our knowledge, no published research has examined prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives and correlates across the age continuum using nationally representative data. Data on tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives in specific age groups could highlight treatment approaches for individual age groups to address unique underlying motives. As an example, higher prevalence of sleep-related motives in a specific age group could direct interventions towards non-pharmacological insomnia treatment. As with motive prevalence, data on the correlates of motives could highlight likely substance use, mental health, and physical health issues that also warrant attention, and could identify if such correlates (and consequent treatment needs) vary by age.

Aims

We used data from the 2015-18 nationally representative U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) to address two major aims. First, we examined the prevalence of individual prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives and motive categories (i.e., self-treatment only or any recreational) by age cohort; and second, we established substance use, SUD, mental health, and physical health correlates of motive categories by age cohort and whether age cohort interacted with motive category for each correlate.

METHODS

The NSDUH is an annual survey of substance use and related behaviors in U.S. residents, using an independent, multistage area probability sampling design. Person-level weights create unbiased and nationally representative estimates. Sensitive topics were assessed by audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) to maximize honesty, with skip-outs and consistency checks to maximize data completeness and accuracy. For 2015-18, the weighted screening response rate ranged from 79.7% to 73.3%, and the weighted interview rate ranged from 69.7% to 66.6%, similar to other nationally representative studies.21 The NSDUH was approved by the Research Triangle International IRB,22 and the Texas State University IRB exempted this work from further human subjects oversight. More information on the NSDUH is available elsewhere.22

Participants

Of the 223,632 individuals in the 2015-18 NSDUH public use files, 6,892 (2.5% weighted) engaged in past-year prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse. Of these, 312 were missing motive data (4.4% of the weighted past-year tranquilizer/sedative misuse sample), and these individuals were excluded from further analyses, resulting in an analytic sample of 6,580. Sociodemographic data are captured in Table 1.

Table 1:

Sociodemographics by Age Group (n = 226,320)

| 12 to 17 Years (n = 54,791) |

18 to 25 Years (n = 55,588) |

26 to 34 Years (n = 35,366) |

35 to 49 Years (n = 45,385) |

50 to 64 Years (20,305) |

65 Years and Older (n = 14,885) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Misuse | Total | Misuse | Total | Misuse | Total | Misuse | Total | Misuse | Total | Misuse | |

| SAMPLE SIZE | ||||||||||||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| FEMALE SEX | 49.1 | 51.7 | 49.8 | 48.3 | 50.4 | 49.0 | 51.0 | 51.9 | 51.7 | 48.8 | 55.2 | 63.0 |

| RACE/ETHNICITY | ||||||||||||

| Caucasian | 52.9 | 56.4 | 54.3 | 67.0 | 56.3 | 75.5 | 58.9 | 79.0 | 69.1 | 80.1 | 77.1 | 81.3 |

| African-American | 13.7 | 8.8 | 14.2 | 9.5 | 13.0 | 7.4 | 12.4 | 5.8 | 11.6 | 5.6 | 9.0 | 1.3 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 23.7 | 25.0 | 21.9 | 17.1 | 20.5 | 12.4 | 19.5 | 10.7 | 12.3 | 11.9 | 8.2 | 12.0 |

| Asian-American | 5.4 | 2.6 | 6.2 | 2.2 | 7.2 | 2.2 | 7.0 | 1.2 | 4.4 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 3.6 |

| American Indian | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Multiracial | 3.2 | 6.3 | 2.4 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.9 |

| HOUSEHOLD INCOME | ||||||||||||

| < $25,000 | 15.6 | 17.5 | 27.7 | 29.3 | 15.6 | 15.7 | 12.8 | 15.8 | 14.8 | 22.4 | 16.9 | 20.2 |

| $25,000-49,999 | 27.7 | 28.9 | 32.2 | 29.8 | 32.8 | 36.0 | 25.7 | 27.5 | 24.9 | 26.9 | 36.7 | 26.4 |

| $50,000-74,999 | 14.3 | 15.0 | 13.9 | 12.8 | 17.9 | 16.4 | 15.3 | 15.6 | 15.7 | 13.9 | 17.3 | 14.5 |

| ≥ $75,000 | 42.3 | 38.7 | 26.3 | 28.1 | 33.7 | 31.8 | 46.2 | 41.2 | 44.6 | 36.7 | 29.2 | 38.9 |

| POPULATION DENSITY | ||||||||||||

| CBSA ≥ 1 million persons | 54.8 | 53.6 | 54.1 | 54.3 | 58.1 | 59.9 | 57.1 | 53.8 | 52.8 | 55.5 | 48.4 | 53.5 |

| CBSA <1 million persons | 39.4 | 40.6 | 41.3 | 41.9 | 37.3 | 35.8 | 37.7 | 42.2 | 40.8 | 38.6 | 44.1 | 43.6 |

| Not in a CBSA | 5.8 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 5.2 | 4.0 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 7.5 | 2.9 |

Data: 2015-2018 NSDUH

Acronyms: CBSA = Core-based Statistical Area

Notes: “Total” denotes the entire available sample for an age cohort (i.e., those without tranquilizer/sedative misuse and those with complete tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives data); “Misuse” denotes the subsample within the age cohort with complete motives data

Measures

Independent Variables: Prescription Tranquilizer/Sedative Misuse Motives

All participants were first asked about lifetime and past-year use of tranquilizer and sedative medications (i.e., benzodiazepines, barbiturates, Z-drugs). Among those with any use, misuse was assessed, defined as medication use “in any way a doctor did not direct…including: using it without a prescription of your own; using it in greater amounts, more often, or longer than you were told to take it; using it in any other way a doctor did not direct.” Those endorsing past year tranquilizer/sedative misuse were then asked about misuse motives.

Survey respondents selected from eight prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives, choosing as many as applied: to relax, to experiment, to get high, to sleep, to help with emotions, to alter other drug effects, because I am “hooked,” and for some other reason. Per past research on prescription misuse motives,16,23 we grouped motives into self-treatment only (i.e., to sleep and/or relax only) or any recreational motives (i.e., all other motives). Self-treatment motives are consistent with FDA indications for benzodiazepine, barbiturate, and Z-drug medications.

Dependent Variables: Correlates

Substance use correlates included: past-month binge alcohol use, past-year marijuana use, past-year other illicit drug use, past-year prescription opioid misuse, past-year tranquilizer/sedative substance use disorder (SUD), and past-year any SUD. Past-year other illicit drug use captures heroin, cocaine, hallucinogen, methamphetamine, and/or inhalant use. Past-year any SUD is DSM-IV substance abuse/dependence from alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, methamphetamine, prescription opioid, tranquilizer, sedative, and stimulant use/misuse. Past-month binge alcohol is four or five alcoholic drinks (for females and males, respectively) during one occasion, per NIAAA guidelines.24

Mental health correlates were (all past-year) major depressive episode, suicidal ideation, serious psychological distress (SPD), and mental health treatment. SPD was derived the K6 assessment of non-specific psychological distress;25 past-year suicidal ideation was defined as “seriously thinking] about trying to kill[ing] yourself” in the past 12 months. SPD and suicidal ideation were not assessed in adolescents. Past-year physical health correlates were past-year emergency department use and past-year inpatient hospitalization.

Sociodemographic variables were sex, race/ethnicity, age group, household income, and population density (Table 1 contains specific categories). Age group was split into 12-17, 18-25, 26-34, 35-49, 50-64, and 65 and older.

Data Analyses

Analyses utilized STATA 16.1 (College Station, TX), incorporating the complex survey design and using the svy commands. Adjusted person-level weights (weight/four) were used, per guidelines.26 The Taylor series approximation, with adjusted degrees of freedom, created robust variance estimates.

First, analyses used weighted cross-tabulations to estimate prevalence of individual tranquilizer/sedative motives and motive categories by age group. For individual motives, logistic models examined significant pairwise differences in motive prevalence by age group. For tranquilizer/sedative motive category, a logistic model compared self-treatment only to any recreational motives. These models controlled for sociodemographics, with an a priori Bonferroni-corrected p-value of 0.0033 for pairwise comparisons (i.e., 0.05/15 comparisons).

Second, we examined differences in the substance use, mental and physical health correlates of tranquilizer/sedative misuse motive categories, versus the reference of no past-year misuse. Self-treatment only was the reference for tranquilizer/sedative SUD. Because of lower prevalence of tranquilizer/sedative misuse within adults 65 years and older, the 50-64 and 65 and older cohorts were aggregated for these analyses. Models were performed within each age cohort separately. A separate analysis occurred across age groups with an interaction term for age group by motive category for each correlate, examining if the magnitude of the correlate-motive category association varied by age. All regression models controlled for sociodemographics.

RESULTS

Table 1 captures participant sociodemographics. Females and Caucasians composed a larger proportion of each cohort with increasing age, while residence in a high population density area fell with aging from peaks in middle adulthood.

Prescription Tranquilizer/Sedative Misuse Motives Across Age Groups

As captured in Table 2, most prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives differed greatly by age cohort. Notably, tranquilizer/sedative misuse to experiment or to get high peaked in adolescents (12-17 years) at 26.9% and 39.2%, respectively. Both decreased with aging, with particularly sharp decreases in experimentation. In contrast, tranquilizer/sedative misuse to promote sleep increased linearly with aging, from 23.9% in adolescents to 63.9% of adults 65 and older. The two other most common motives, to relax and to help with other emotions, evidenced non-linear associations with age: both peaked in the 26-34 cohort at 62.3% (to relax) and 26.3% (to help with other emotions). To relax displayed a more curvilinear relationship with age, starting at 44.0% in adolescents before peaking and declining to 32.5% in adults 65 and older. Prevalence of tranquilizer/sedative misuse to alter other drug effects, “because I’m hooked”, and for some other reason were much lower (< 7%).

Table 2:

Prevalence of Tranquilizer/Sedative Misuse Motives Across Age Groups

| 12 to 17 Years (a) |

18 to 25 Years (b) |

26 to 34 Years (c) |

35 to 49 Years (d) |

50 to 64 Years (e) |

65 Years and Older (f) |

Pairwise Comparisons |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAMPLE SIZE | (n = 993) | (n = 2,835) | (n = 1,271) | (n = 1,025) | (n = 352) | (n = 104) | |

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | ||

| INDIVIDUAL MOTIVES | |||||||

| to Relax | 44.0 (39.6-48.5) | 55.3 (53.1-57.4) | 62.3 (58.2-66.2) | 59.4 (54.3-64.2) | 48.9 (42.8-55.0) | 32.5 (24.3-41.9) | a, f < b, c, d b, e < c |

| to Experiment | 26.9 (23.8-30.3) | 20.4 (18.3-22.7) | 6.2 (4.8-8.0) | 3.6 (2.3-5.6) | 3.6 (1.8-7.0) | 2.2 (0.6-8.0) | c, d, e, f < b < a |

| to Get High | 39.2 (35.9-42.7) | 33.5 (31.0-36.1) | 18.4 (16.4-20.6) | 10.6 (8.7-12.8) | 4.6 (2.6-8.0) | 4.8 (1.6-13.5) | c, d, e, f < b < a d, e < c |

| to Sleep | 23.9 (21.2-26.9) | 33.7 (31.5-36.0) | 42.9 (40.4-45.4) | 48.3 (45.0-51.6) | 50.1 (44.3-55.8) | 63.9 (53.3-73.2) | a < b < c, d, e, f c < f |

| to Help with Emotions | 22.3 (19.5-25.5) | 24.0 (22.4-25.8) | 26.3 (23.0-29.9) | 21.0 (18.4-23.9) | 16.7 (12.0-22.8) | 9.2 (3.6-21.5) | e < c |

| to Alter Other Drug Effects | 2.5 (1.6-3.9) | 6.2 (5.1-7.4) | 5.1 (3.6-7.1) | 2.3 (1.4-3.6) | 2.0 (0.8-5.0) | 0.7 (0.1-4.8) | a, d < b |

| “Because I’m Hooked” | 0.4 (0.2-0.9) | 1.5 (1.0-2.1) | 1.2 (0.7-2.3) | 1.1 (0.5-2.4) | 1.5 (0.5-4.8) | 0.6 (0.1-4.0) | no differences |

| Some Other Reason | 4.9 (3.6-6.5) | 4.7 (3.8-5.7) | 5.4 (4.0-7.3) | 5.2 (3.9-6.7) | 4.9 (2.9-8.0) | 3.6 (1.3-9.8) | no differences |

| MOTIVE CATEGORIES | |||||||

| Sleep and/or Relax Motives Only | 32.5 (29.2-36.0) | 38.0 (35.8-40.4) | 54.9 (50.7-59.1) | 68.1 (64.8-71.3) | 74.6 (68.1-80.1) | 82.7 (71.4-90.1) | base outcome |

| Any Recreational Motives | 67.5 (64.0-70.8) | 62.0 (59.7-64.2) | 45.1 (40.9-49.3) | 31.9 (28.7-35.3) | 25.5 (19.9-31.9) | 17.3 (9.9-28.6) | d, e, f < c < b < a |

Data: 2018-18 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

95% CI = 95% confidence interval of the point prevalence estimate

Pairwise comparisons controlled for sex, race/ethnicity, household income and population density of residence and were Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons, with comparisons only noted when they differ at a p-level of 0.05 or less; columns add up to greater than 100%, as individuals could endorse multiple motives (and be included in the multiple sources group).

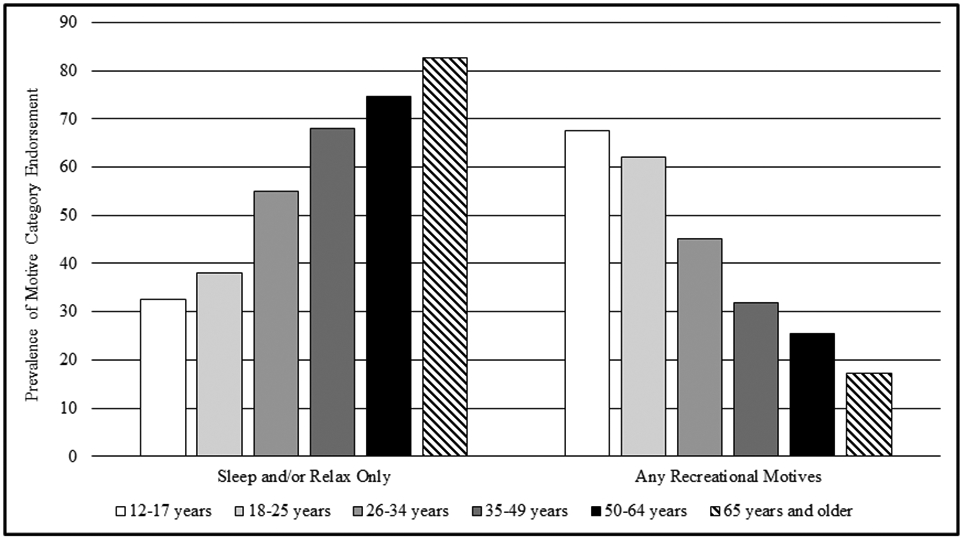

For motive categories (see Figure 1), self-treatment only motives increased greatly with age, while any recreational motives decreased sharply. Self-treatment only was present in 32.5% of adolescents engaged in tranquilizer/sedative misuse, increasing to 82.7% in adults 65 and older. The largest overall increase was 16.9%, from young adults (18-25 years) to adults 26-34 years. Conversely, recreational motives decreased in a significant stepwise fashion from adolescents (67.5%) to young adults (62.0%), and then to adults 26-34 years (45.1%); adults 35 and older had lower rates of recreational only motives (17.3-31.9%) than all younger cohorts.

Figure 1:

Tranquilizer/Sedative Misuse Motive Category Prevalence by Age Group

Lifespan Differences in Substance Use by Prescription Tranquilizer/Sedative Motive Category

Across substance use correlates, any prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse was associated with significantly elevated odds versus the non-misuse reference group (see Table 3). The highest odds ratios (ORs) were with any recreational motives, except for past-month binge alcohol use in those 50 and older. Also, odds of past-year tranquilizer/sedative SUD were significantly higher in those with any recreational motives, versus the self-treatment only group. Finally, the correlate ORs were generally highest in adolescents, regardless of motive category.

Table 3:

Lifespan Differences in Substance Use Correlates of Tranquilizer/Sedative Motive Categories

| Age Group | Motive Category |

Past-Month Binge Alcohol Use |

Past-Year Marijuana Use |

Past-Year Other Illicit Drug Usea |

Past-Year Opioid Misuse |

Past-Year Tranquilizer- Sedative SUD |

Past-Year Any SUDb |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | OR (95% CI) |

% | OR (95% CI) |

% | OR (95% CI) |

% | OR (95% CI) |

% | OR (95% CI) |

% | OR (95% CI) |

||

| Adolescents (12-17 years) | Non-Misuse | 4.6 | 1.00 (ref.) | 11.3 | 1.00 (ref.) | 3.6 | 1.00 (ref.) | 2.5 | 1.00 (ref.) | 0.0 | N/A | 3.3 | 1.00 (ref.) |

| Sleep-Relax Only | 30.4 | 9.20 (6.77-12.51)*** | 59.8 | 11.73 (8.73-15.76)*** | 35.9 | 15.16 (11.45-20.07)*** | 37.2 | 22.87 (16.28-32.14)*** | 13.2 | 1.00 (ref.) | 37.0 | 17.00 (12.87-22.46)*** | |

| Any Recreational | 58.8 | 15.06 (12.16-18.65)*** | 84.2 | 42.11 (31.61-56.11)***+ | 53.2 | 30.80 (24.88-38.12)***+ | 51.3 | 40.86 (33.14-50.39)***+ | 22.8 | 1.94 (1.14-3.31)* | 61.4 | 46.10 (36.74-57.86)***+ | |

| Young Adults (18-25 years) | Non-Misuse | 35.7 | 1.00 (ref.) | 31.0 | 1.00 (ref.) | 8.3 | 1.00 (ref.) | 4.7 | 1.00 (ref.) | 0.0 | N/A | 12.5 | 1.00 (ref.) |

| Sleep-Relax Only | 63.4 | 3.04 (2.58-3.58)*** | 74.6 | 6.49 (5.57-7.56)*** | 41.9 | 7.98 (6.72-9.47)*** | 40.6 | 13.79 (11.72-16.22)*** | 8.0 | 1.00 (ref.) | 46.8 | 6.10 (5.14-7.23)*** | |

| Any Recreational | 65.9 | 3.39 (3.02-3.81)*** | 86.4 | 14.01 (11.83-16.59)***+ | 63.5 | 19.40 (16.83-22.36)*** | 51.6 | 21.69 (19.07-24.67)***+ | 15.0 | 2.02 (1.44-2.84)*** | 64.8 | 12.79 (11.28-14.52)***+ | |

| Early Middle Adults (26-34 years) | Non-Misuse | 36.3 | 1.00 (ref.) | 21.5 | 1.00 (ref.) | 5.8 | 1.00 (ref.) | 4.9 | 1.00 (ref.) | 0.0 | N/A | 10.4 | 1.00 (ref.) |

| Sleep-Relax Only | 61.5 | 2.78 (2.24-3.45)*** | 60.4 | 5.40 (4.49-6.50)*** | 35.0 | 8.77 (7.06-10.90)*** | 41.9 | 14.04 (11.78-16.72)*** | 5.0 | 1.00 (ref.) | 41.7 | 6.20 (5.05-7.60)*** | |

| Any Recreational | 58.1 | 2.38 (1.94-2.93)*** | 71.4 | 8.63 (6.82-10.93)***+ | 54.3 | 19.18 (15.39-23.91)***+ | 53.2 | 21.33 (17.25-26.36)*** | 15.2 | 3.39 (2.03-5.66)*** | 61.6 | 13.78 (11.21-16.95)***+ | |

| Middle Adults (35-49 years) | Non-Misuse | 29.4 | 1.00 (ref.) | 12.3 | 1.00 (ref.) | 2.5 | 1.00 (ref.) | 3.5 | 1.00 (ref.) | 0.0 | N/A | 7.1 | 1.00 (ref.) |

| Sleep-Relax Only | 47.9 | 2.22 (1.79-2.76)*** | 45.5 | 5.43 (4.36-6.78)*** | 18.3 | 8.23 (6.14-11.03)*** | 42.9 | 19.43 (15.85-23.81)*** | 5.2 | 1.00 (ref.) | 36.5 | 7.59 (5.76-9.21)*** | |

| Any Recreational | 57.2 | 3.22 (2.56-4.05)*** | 55.1 | 8.20 (6.37-10.56)*** | 36.2 | 22.89 (17.68-29.63)***+ | 53.1 | 29.98 (22.40-40.12)*** | 22.8 | 5.81 (3.15-10.72)*** | 63.6 | 23.52 (18.43-30.02)***+ | |

| Older Adults (50 and older) | Non-Misuse | 17.3 | 1.00 (ref.) | 6.7 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.1 | 1.00 (ref.) | 2.0 | 1.00 (ref.) | 0.0 | N/A | 3.7 | 1.00 (ref.) |

| Sleep-Relax Only | 37.2 | 2.81 (2.15-3.68)*** | 27.2 | 5.24 (4.20-6.54)*** | 7.7 | 7.63 (4.50-12.92)*** | 29.1 | 20.38 (15.88-26.17)*** | 6.5 | 1.00 (ref.) | 27.0 | 9.85 (7.44-13.03)*** | |

| Any Recreational | 35.1 | 2.81 (1.77-4.47)*** | 28.8 | 5.44 (3.06-9.69)*** | 24.8 | 26.32 (13.62-50.86)***+ | 44.1 | 37.04 (23.36-58.74)***+ | 22.3 | 3.10 (1.48-6.49)** | 52.4 | 31.36 (18.71-52.58)***+ | |

| Age Group by Motive Category Interaction |

t = −1.71 p = 0.092 |

t = −6.35 p < 0.0001 |

t = −0.78 p = 0.44 |

t = 5.46 p < 0.0001 |

t = 4.60 p < 0.0001 |

t = 2.83 p = 0.007 |

|||||||

Data: 2015-18 National Survey on Drug Use and Health

OR = Odds Ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval of the odds ratio; SUD = Substance Use Disorder

Other Illicit Drug Use is composed of past-year heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, hallucinogen or inhalant use

Past-Year Any SUD is DSM-IV SUD from one or more of: alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogen, inhalant, methamphetamine, or prescription opioid use, and prescription tranquilizer, sedative, or stimulant misuse

All models controlled for sex, race/ethnicity, household income and population density of residence.

denotes p < 0.05

denotes p < 0.01

denotes p < 0.001

denotes significant difference between Sleep and/or Relax Motives Only and Recreational Motives categories (p < 0.01).

Notably, adolescents with any recreational motives had 39.9 times greater odds of past-year opioid misuse (51.3% prevalence rate) and 45.1 times greater odds of any past-year SUD (61.4% prevalence rate) than those without misuse (prevalence rates of 2.5% and 3.3%, respectively) and adults 50 and older had 36 times greater odds of opioid misuse (44.1% prevalence rate, versus 2.0% for no misuse) and 30.4 times greater odds of any SUD (52.4% prevalence rate, versus 3.7% for no misuse). Significant age-based interactions were observed for any SUD (p= 0.007), marijuana use, opioid misuse, and tranquilizer/sedative SUD (all ps< 0.0001). The past-year marijuana use interaction seemed based on OR reductions from adolescents to young adults and from young adults to all other adults; in contrast, the opioid misuse and any SUD interactions seemed to result from U-shaped age-based relationships, with the highest ORs in adolescents, declines with aging, before increases in middle and older adults (35 and older). For tranquilizer/sedative SUD, the age-OR relationship was an inverted U-shape, peaking in the 35-49 year cohort. Post hoc sensitivity analyses that split the any recreational motives group into recreational only and combined motives (i.e., both self-treatment and recreational motives) categories found limited differences between recreational only and combined motives; both had consistently higher ORs than the self-treatment only group.

Lifespan Differences in Mental and Physical Health by Tranquilizer/Sedative Motive Category

Per Table 4, any tranquilizer/sedative misuse (versus non-misuse) was associated with significantly higher odds of mental health correlates. Physical health correlates evidenced the same pattern, except in adults 50 and older, where only recreational motives were associated with inpatient hospitalization. Notably, mental health correlates displayed a stepwise association with tranquilizer/sedative misuse motive category in nearly every case, with significantly higher odds in those with any recreational motives than those with self-treatment motives only.

Table 4:

Lifespan Differences in Mental and Physical Health Correlates of Tranquilizer Sedative Motive Categories

| Age Group | Motive Category |

Past-Year Major Depression |

Past-Year Suicidal Ideation |

Past-Year Serious Psychological Distress |

Past-Year Mental Health Treatment |

Past-Year Emergency Department Use |

Past-Year Inpatient Hospitalization |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | OR (95% CI) |

% | OR (95% CI) |

% | OR (95% CI) |

% | OR (95% CI) |

% | OR (95% CI) |

% | OR (95% CI) |

||

| Adolescents (12-17 years) | Non-Misuse | 12.9 | 1.00 (ref.) | N/A | N/A | 23.2 | 1.00 (ref.) | 27.7 | 1.00 (ref.) | 4.8 | 1.00 (ref.) | ||

| Sleep-Relax Only | 24.2 | 2.20 (1.58-3.06)*** | 43.2 | 2.52 (1.89-3.35)*** | 51.5 | 2.75 (2.05-3.68)*** | 11.2 | 2.46 (1.60-3.80)*** | |||||

| Any Recreational | 39.6 | 4.67 (3.67-5.93)***+ | 48.1 | 3.05 (2.49-3.75)*** | 43.3 | 2.00 (1.62-2.47)*** | 15.0 | 3.48 (2.62-4.63)*** | |||||

| Young Adults (18-25 years) | Non-Misuse | 11.2 | 1.00 (ref.) | 8.7 | 1.00 (ref.) | 21.4 | 1.00 (ref.) | 12.8 | 1.00 (ref.) | 28.7 | 1.00 (ref.) | 6.6 | 1.00 (ref.) |

| Sleep-Relax Only | 20.6 | 2.04 (1.66-2.51)*** | 18.4 | 2.34 (1.91-2.87)*** | 37.9 | 2.19 (1.79-2.68)*** | 25.1 | 2.19 (1.79-2.68)*** | 38.9 | 1.57 (1.31-1.87)*** | 8.1 | 1.24 (0.92-1.66) | |

| Any Recreational | 27.4 | 3.04 (2.62-3.53)***+ | 27.0 | 3.89 (3.41-4.44)***+ | 48.1 | 3.24 (2.79-3.77)***+ | 32.1 | 3.24 (2.79-3.77)***+ | 40.9 | 1.75 (1.53-1.99)*** | 10.4 | 1.69 (1.34-2.14)*** | |

| Early Middle Adults (26-34 years) | Non-Misuse | 7.8 | 1.00 (ref.) | 5.0 | 1.00 (ref.) | 14.2 | 1.00 (ref.) | 13.8 | 1.00 (ref.) | 26.5 | 1.00 (ref.) | 8.4 | 1.00 (ref.) |

| Sleep-Relax Only | 16.6 | 2.21 (1.72-2.83)*** | 12.4 | 2.57 (1.95-3.39)*** | 29.9 | 2.55 (2.06-3.16)*** | 30.2 | 2.55 (2.06-3.16)*** | 32.4 | 1.32 (1.14-1.54)*** | 6.6 | 0.78 (0.56-1.09) | |

| Any Recreational | 33.3 | 5.58 (4.45-6.99)***+ | 23.3 | 5.33 (4.08-6.97)***+ | 51.5 | 4.65 (3.74-5.78)***+ | 43.7 | 4.65 (3.74-5.78)***+ | 37.6 | 1.63 (1.35-1.96)*** | 12.7 | 1.68 (1.22-2.33)**+ | |

| Middle Adults (35-49 years) | Non-Misuse | 6.8 | 1.00 (ref.) | 3.3 | 1.00 (ref.) | 10.2 | 1.00 (ref.) | 15.5 | 1.00 (ref.) | 23.4 | 1.00 (ref.) | 7.3 | 1.00 (ref.) |

| Sleep-Relax Only | 19.9 | 3.00 (2.36-3.80)*** | 13.7 | 3.94 (2.99-5.18)*** | 31.0 | 2.95 (2.37-3.68)*** | 37.5 | 2.95 (2.37-3.68)*** | 33.4 | 1.49 (1.19-1.85)** | 10.8 | 1.39 (1.05-1.85)* | |

| Any Recreational | 32.5 | 6.26 (4.82-8.12)***+ | 25.2 | 8.86 (6.25-12.54)***+ | 48.3 | 6.35 (4.96-8.13)***+ | 55.0 | 6.35 (4.96-8.13)***+ | 36.1 | 1.76 (1.35-2.29)*** | 13.1 | 1.81 (1.26-2.59)** | |

| Older Adults (50 and older) | Non-Misuse | 4.5 | 1.00 (ref.) | 2.3 | 1.00 (ref.) | 5.8 | 1.00 (ref.) | 13.6 | 1.00 (ref.) | 26.1 | 1.00 (ref.) | 13.1 | 1.00 (ref.) |

| Sleep-Relax Only | 14.1 | 3.57 (2.47-5.20)*** | 9.2 | 4.42 (2.90-6.72)*** | 17.8 | 3.53 (2.68-4.64)*** | 34.5 | 3.53 (2.68-4.64)*** | 30.4 | 1.26 (0.95-1.68) | 16.2 | 1.30 (0.87-1.94) | |

| Any Recreational | 37.7 | 11.11 (6.87-17.95)***+ | 22.4 | 10.86 (6.04-19.54)*** | 43.9 | 9.55 (5.68-16.04)***+ | 61.2 | 9.55 (5.68-16.04)***+ | 39.2 | 1.57 (0.95-2.58) | 27.1 | 2.12 (1.26-3.57)** | |

| Age Group by Motive Category Interaction |

t = 6.52 p < 0.0001 |

t = 6.84 p < 0.0001 |

t = 7.71 p < 0.0001 |

t = 8.09 p < 0.0001 |

t = −1.26 p = 0.21 |

t = − 0.65 p = 0.52 |

|||||||

Data: 2015-18 National Survey on Drug Use and Health

OR = Odds Ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval of the odds ratio

All models controlled for sex, race/ethnicity, household income and population density of residence.

denotes p < 0.05

denotes p < 0.01

denotes p < 0.001

denotes significant difference between Sleep and/or Relax Motives Only and Recreational Motives categories (p < 0.01).

Across all age groups, those engaged in tranquilizer/sedative misuse for self-treatment only had over double the odds of past-year major depression, suicidal ideation, serious psychological distress, and mental health treatment than those without misuse. For recreational motives, the minimum increase in odds was 200% (or triple) for these outcomes, versus non-misuse. Compared to their non-misuse peers, adults aged 50 and older who engaged in tranquilizer/sedative misuse with recreational motives had 10.1 times greater odds of past-year major depression (37.7% prevalence rate versus 4.5% for no misuse) and 9.9 times greater odds of suicidal ideation (22.4% prevalence rate versus 2.3% for no misuse).

No physical health correlates displayed a significant age-based interaction with tranquilizer/sedative motive categories, while all mental health correlates did (ps< 0.0001). In mental health correlates, there was a linear increase in ORs in both self-treatment only and any recreational motive categories from young adults to adults 50 and older; adolescents often had higher odds of mental health correlates than young adults but lower ORs than in all age groups 26 and older. As with substance use, post hoc sensitivity analyses that included a combined motive group found limited differences between the recreational only and combined groups, with higher ORs in these groups than in the self-treatment only category.

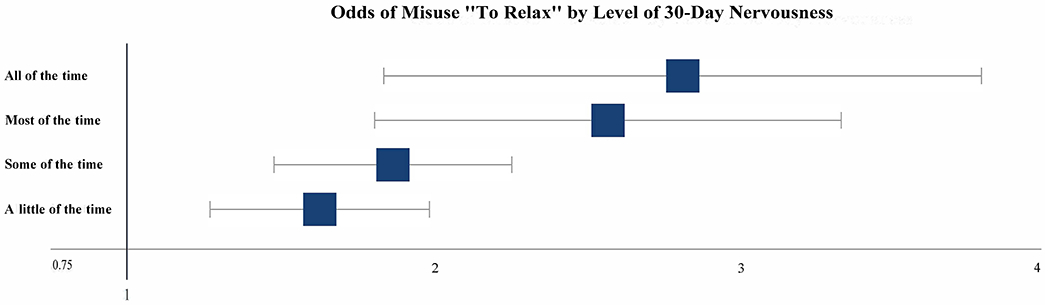

Finally, post hoc logistic regression analyses examined the relationship of the K6 question on level of past 30-day nervousness to endorsement of prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse to promote relaxation. As captured in Figure 2, any past 30-day nervousness (versus the reference group of “none”) was associated with increased odds of endorsement of “to relax”. Odds decreased with decreasing frequency of nervousness: 2.64 for “all of the time” (95% confidence interval [95% CI]= 1.84-3.80), 2.46 for “most of the time” (95% CI= 1.81-3.34), 1.83 for “some of the time” (95% CI= 1.49-2.26), and 1.59 for “a little of the time” (95% CI= 1.27-1.99).

Figure 2:

Odds of Misuse "To Relax" by Level of 30-Day Nervousness

Bars represent 95% confidence intervals of the odds ratio estimate

DISCUSSION

For the first aim, examining age-based differences in prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives, we found misuse to promote sleep or self-treatment overall increased clearly with increasing age. Also, misuse to experiment, get high, or for any recreational motive decreased with increasing age. In contrast, tranquilizer/sedative misuse motivated by anxiolysis (i.e., to relax) or to help with emotions displayed an inverted U-shape across age cohorts, peaking in the 26-34 cohort. Elevated recreational motives in younger age groups and elevated self-treatment motives in older adults are consistent with previous research on prescription opioid misuse motives across age groups27 and research in adolescents and young adults on tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives.14,16

In the second aim, examining correlates of tranquilizer/sedative misuse and age-motive category interactions across ages, any prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse (i.e., with self-treatment only or any recreational motives) was associated with increased odds of all examined substance use correlates in each age cohort. While odds were highest in those with any recreational motives, they were significantly different from the self-treatment only odds roughly half the time. Finally, analyses revealed four interactions between age cohort and motive category (i.e., past-year marijuana use, opioid misuse, tranquilizer/sedative SUD, and any SUD), though the pattern of the age-based interaction was not consistent.

With each examined mental health correlate, odds were highest in those with any recreational motives. Odds significantly increased from self-treatment only (always significantly higher than for non-misuse) to any recreational motives in all but two cases, and all mental health variables evidenced a significant motive category by age interaction. For the interaction, odds of the mental health correlate increased with age. Physical health was weakly associated with tranquilizer/sedative misuse motive categories, though both self-treatment only and recreational motives for misuse were generally associated with elevated odds of emergency department use and hospitalization. While self-treatment motives for prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse may be seen as less problematic, membership in the self-treatment only group was associated with elevated odds of every substance use/SUD and mental health correlate. Any tranquilizer/sedative misuse signals greater odds of poor outcomes.

Nonetheless, recreational tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives were associated with significantly higher odds of past-year any SUD, major depression, SPD, suicidal ideation, and mental health treatment versus self-treatment only motives, with slight exceptions for suicidality and mental health treatment. Recreational motives were often also associated with other illicit substance use, meaning that past-year polysubstance use (i.e., tranquilizer/sedative misuse plus another substance) is also more common in those with recreational motives. Tranquilizer/sedative misuse with recreational motives thus marks highest risk for substance use and psychopathology. For elevated rates of psychopathology, links between PDM and psychopathology are well established,3,6,9 but links with recreational motives are less well established and future research is needed to understand this link.

For elevated substance use, misuse motivated by experimentation or euphoria seeking is possible with a variety of drugs, including alcohol, marijuana, other controlled prescriptions, and other illicit drugs. Thus, tranquilizer/sedative misuse in those with recreational motives may be motivated less by the desire for a specific drug or medication than desire for a drug that alters mood, consistent with affect regulation models of substance use.28 Similarly, higher levels of recreational motives among adolescents and young adults suggests motivations that could apply to many different drugs. This is consistent with the higher levels of overall substance use in these age groups.2

In contrast, elevations in prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives to relax that occur in middle adulthood may reflect increased responsibilities and stressors that co-occur with employment, marriage/partnership, and parenting.29,30 A key caveat is that “to relax” could be interpreted differently by age cohort: as anxiolysis and calming in middle and older adults, but as “to chill” by younger respondents, with may also connote mild euphoria. This warrants further investigation, likely with qualitative methods to discern interpretation of response options for motives. The sharp increases in tranquilizer/sedative misuse to promote sleep in older adults are mirrored by low levels of any recreational tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives, suggesting such misuse is for specific medical purposes indicated with tranquilizer/sedative use. Thus, the medication may be an instrument to achieve sleep and/or anxiolysis, consistent with drug instrumentalization theory, which states that a substance is a tool (or instrument) used to achieve a specific outcome.31 Consistent increases by age group in the odds of mental health outcomes associated with any tranquilizer/sedative misuse may support this by signaling greater likelihood of mental health issues in older adults with misuse, with misuse attempting to ameliorate symptoms, regardless of motive. Given the cross-sectional nature of the data, this is speculation that needs further evaluation.

Clinical Implications

Our findings suggest that screening and prevention programs may need to consider different approaches by age group among those at-risk for tranquilizer/sedative misuse. Research by Spoth and colleagues found that a seven-session parent-child prevention program for 11- and 12-year-old children targeting emotional regulation, prosocial behavior, parent-child interactions, and negative peer influences is associated with significantly lower rates of prescription drug misuse at 17/18, 21, and 27 years of age.32-34 Thus, universal prevention may limit substance use more generally and prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse specifically. Screening for prescription tranquilizer/sedative access and misuse is warranted in adolescents and young adults with elevated levels of other substance use. For middle adults, screening for significant life stressors and anxiety may be indicated, in addition to screening for elevated other substance use.

Screening in older adults may need to focus primarily on insomnia, though anxiety and other substance use are key issues as well. Treatment in middle and older adults may necessitate non-tranquilizer/sedative and/or non-pharmacological options for insomnia, anxiety, and life stress, but the greatly elevated odds for other substance use emphasize that substance use treatment in this population should not be ignored. Given the small sample size of adults 65 years and older engaged in tranquilizer/sedative misuse, we were unable to examine correlates of this older adult group separately; future research is needed on tranquilizer/sedative misuse in this age group, given their particular emphasis on tranquilizer/sedative misuse for self-treatment.

Limitations

These results are limited by the cross-sectional NSDUH data, which prevents inference of any causal processes, including the influence of age on tranquilizer/sedative motives. Also, the data are limited by self-report bias and self-selection bias. Nonetheless, evidence indicates that self-report substance use data are reliable and valid,35,36 and the NSDUH design minimizes bias through weighting to correct for non-response, and use of ACASI methods, medication pictures and trade and generic medication names.37 Such methods, however, cannot correct for the 4.4% of those engaged in past-year tranquilizer/sedative misuse who did not provide adequate motives data. Given that the sample is from the non-institutionalized, civilian US population, results cannot be generalized to different (e.g., imprisoned, homeless) populations. Finally, the NSDUH under-samples older adults living in nursing facilities and other controlled access dwellings, despite specific efforts to increase their participation.38

CONCLUSIONS

This research indicates tranquilizer/sedative motives vary significantly by age group, with greater prevalence of any recreational motives in younger groups and self-treatment only motives in middle and older adults. While only having self-treatment motives for tranquilizer/sedative misuse was associated with increased odds of concurrent substance use, SUD, mental health, and physical health correlates, recreational motives were associated with the highest odds. Interactions between age cohort and motive category were most consistent for mental health and suggested greater levels of mental health problems in older adults engaged in tranquilizer/sedative misuse, versus younger groups. Future research that examines longitudinal processes is needed to fully tease out the relationships between prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse motives, self-treatment, substance use, and mental health across the age continuum.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support:

Ty S. Schepis received grants R01DA043691 and R01DA042146 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Sean Esteban McCabe received grant R01DA031160, also from NIDA. The NSDUH is sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and NIDA. The content is the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the views of NIDA or SAMHSA.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrett SP, Meisner JR, Stewart SH. What constitutes prescription drug misuse? Problems and pitfalls of current conceptualizations. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1(3):255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed tables. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Votaw VR, Geyer R, Rieselbach MM, McHugh RK. The epidemiology of benzodiazepine misuse: A systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;200:95–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria(R) for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schepis TS. Age cohort differences in the nonmedical use of prescription zolpidem: findings from a nationally representative sample. Addict Behav. 2014;39(9):1311–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schepis TS, Teter CJ, Simoni-Wastila L, McCabe SE. Prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse prevalence and correlates across age cohorts in the US. Addict Behav. 2018;87:24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maree RD, Marcum ZA, Saghafi E, Weiner DK, Karp JF. A Systematic Review of Opioid and Benzodiazepine Misuse in Older Adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(11):949–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd CJ, West B, McCabe SE. Does misuse lead to a disorder? The misuse of prescription tranquilizer and sedative medications and subsequent substance use disorders in a U.S. longitudinal sample. Addict Behav. 2018;79:17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schepis TS, Simoni-Wastila L, McCabe SE. Prescription opioid and benzodiazepine misuse is associated with suicidal ideation in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(1):122–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: a meta-analytic review. Addict Behav. 2007;32(11):2469–2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canale N, Vieno A, Santinello M, Chieco F, Andriolo S. The efficacy of computerized alcohol intervention tailored to drinking motives among college students: a quasi-experimental pilot study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2015;41(2):183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blevins CE, Banes KE, Stephens RS, Walker DD, Roffman RA. Change in motives among frequent cannabis-using adolescents: Predicting treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;167:175–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd CJ, McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Young A. Adolescents' motivations to abuse prescription medications. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2472–2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCabe SE, Cranford JA. Motivational subtypes of nonmedical use of prescription medications: results from a national study. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(5):445–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva K, Kecojevic A, Lankenau SE. Perceived Drug Use Functions and Risk Reduction Practices Among High-Risk Nonmedical Users of Prescription Drugs. J Drug Issues. 2013;43(4):483–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Teter CJ. Subtypes of nonmedical prescription drug misuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;102(1-3):63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nattala P, Leung KS, Abdallah AB, Murthy P, Cottler LB. Motives and simultaneous sedative-alcohol use among past 12-month alcohol and nonmedical sedative users. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(4):359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rigg KK, Ibanez GE. Motivations for non-medical prescription drug use: a mixed methods analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;39(3):236–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stein MD, Kanabar M, Anderson BJ, Lembke A, Bailey GL. Reasons for Benzodiazepine Use Among Persons Seeking Opioid Detoxification. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;68:57–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fatséas M, Lavie E, Denis C, Auriacombe M. Self-perceived motivation for benzodiazepine use and behavior related to benzodiazepine use among opiate-dependent patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37(4):407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant BF, Chu A, Sigman R, et al. Source and accuracy statement: National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III). Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological resource book (Section 8, data collection final report). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Cranford JA, Teter CJ. Motives for nonmedical use of prescription opioids among high school seniors in the United States: self-treatment and beyond. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(8):739–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA Newsletter, Winter 2004. Bethesda, MD: Office of Research Translation and Communications, NIAAA; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological Resource Book (Section 13: Statistical Inference Report). In. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schepis TS, Wastila L, Ammerman B, McCabe VV, McCabe SE. Prescription Opioid Misuse Motives in US Older Adults. Pain Med. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Cheetham A, Allen NB, Yucel M, Lubman DI. The role of affective dysregulation in drug addiction. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(6):621–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Statistics Canada. Table 13-10-00-04: Perceived life stress, by age group.

- 30.Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. The Health and Well-Being of Children: A Portrait of States and the Nation, 2011-2012. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller CP, Schumann G. Drugs as instruments: a new framework for non-addictive psychoactive drug use. Behav Brain Sci. 2011;34(6):293–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spoth R, Trudeau L, Redmond C, Shin C. Replicating and extending a model of effects of universal preventive intervention during early adolescence on young adult substance misuse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84(10):913–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spoth R, Trudeau L, Shin C, et al. Longitudinal effects of universal preventive intervention on prescription drug misuse: three randomized controlled trials with late adolescents and young adults. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(4):665–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spoth R, Trudeau L, Shin C, Redmond C. Long-term effects of universal preventive interventions on prescription drug misuse. Addiction. 2008;103(7):1160–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Reliability and consistency in self-reports of drug use. Internati J Addict. 1983;18:805–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM. Issues of validity and population coverage in student surveys of drug use. NIDA Res Monogr. 1985;57:31–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): Summary of methodological studies, 1971-2014. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cunningham D, Flicker L, Murphy J, Aldworth J, Myers S, Kennet J. Incidence and Impact of Controlled Access Situations on Nonresponse. American Association for Public Opinion Research 60th Annual Conference; 2015; Miami Beach, FL. [Google Scholar]