Abstract

Background

The MindSpot Clinic provides services to Australians with anxiety and depression. Routine data collection means that MindSpot has been able to monitor trends in mental health symptoms and service use prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and these have been reported in two earlier studies. This third study describes user characteristics and volumes in the first 8 months of COVID-19, including a comparison between users from states and territories with significantly different COVID-19 infection rates.

Methods

We examined trends in demographics and symptoms for participants starting an online assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic, from March to October 2020. Participants from the state of Victoria (n = 4203), which experienced a significantly larger rate of COVID-19 infections relative to the rest of Australia, were compared to participants from the rest of Australia (n = 10,500). Results were also compared to a baseline “comparison period” prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

A total of 14,703 people started a mental health assessment with MindSpot between 19th March and 28th October 2020. We observed two peaks in service demand, one in the early weeks of the pandemic, and the second in August–September when COVID-19 transmission was high in Victoria. Mean symptom scores on standardised measures of distress (K-10), depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) were lower during this second peak in service demand, but there were significantly higher levels of concern about COVID-19 in participants from Victoria, and a higher proportion of Victorian respondents reported that they had made significant changes in response to the pandemic. Many respondents reported changes to their mental health, such as increased feelings of worry. Most respondents reported implementing strategies to help manage the psychological impact of COVID-19, such as maintaining social connections and limiting exposure to news or social media.

Conclusions

We did not observe increased levels of clinical anxiety or depression on standardised symptom measures. However, there were increases in service demand, and increased levels of concern and difficulties related to COVID-19, particularly in Victoria. Encouragingly, a significant proportion of participants have implemented coping strategies. These results continue to suggest that the mental health impacts of COVID-19 represent a normal response to an abnormal situation rather than an emerging mental health crisis. This distinction is important as we develop individually appropriate and proportional mental health system responses.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Internet, Mental health, Anxiety, Depression

Highlights

-

•

We describe patient characteristics and regional variation for users of a digital mental health service in Australia.

-

•

In Australia from July to October, the state of Victoria was disproportionally affected by COVID-19.

-

•

Service demand and concern about COVID-19 were high in Victoria compared to the rest of Australia.

-

•

Encouragingly, a significant proportion of participants implemented coping strategies.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to have social, economic, psychological and health impacts across the world. The severity of these impacts is highly heterogenous, both between and within countries (Hendrie, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020). For example, in Australia to date, the overall rate of COVID-19 infections has been amongst the lowest in the world (Woodley, 2020). However, the state of Victoria, which has 26% of the Australian population, was disproportionately affected by COVID-19. As of 31st October 2020, Australia had 27,582 cases of COVID-19, with 907 deaths recorded. Almost three-quarters of these cases (20,347) and 90% of these deaths (819) had occurred in Victoria (Australian Government, 2020).

In Australia, as in many countries, there was an initial outbreak of COVID-19 in March–April 2020 that led to state, territory, and federal government restrictions (Saul et al., 2020). As cases declined, government restrictions were eased. However, from early July 2020, there was a resurgence of COVID-19 community transmission in Victoria, and strict control measures were reintroduced to that state. These included restrictions on travel, social gatherings and non-essential business, school closures, state border closures, and mandatory face coverings. These measures were successful and by late October, community transmission had declined and restrictions were again eased (Saul et al., 2020, Victorian Government, 2020a, Victorian Government, 2020b). On 31st October, zero cases of community transmission were recorded in Victoria, and by 28th November, the state reached the benchmark for local elimination of COVID-19, recording 28 consecutive days without a locally acquired case (SBS News, 2020).

The psychological effects of COVID-19 are expected to be significant (Brooks et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020), and while these effects are disproportionately severe in some populations (Bartone et al., 2020; Ryan et al., 2020), the psychological impacts may generally be considered appropriate adjustments to unprecedented circumstances (Fisher et al., 2020; Staples et al., 2020; Titov et al., 2020b). In either case, it is important that appropriate mental health services are in place and available to support people, both in the acute stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, and in the longer-term.

Digital Mental Health Services (DMHS) have played an important role in providing access to evidence-based services for people unwilling or unable to engage in face-to-face contact during the pandemic. DMHS are also well-placed to deliver brief crisis-focused interventions to assist people to manage stressful situations. The MindSpot Clinic is a national digital mental health service funded by the Australian Government to provide psychological assessment and treatment services for adults with symptoms of anxiety and depression (Titov et al., 2017; Titov et al., 2020a). Routine collection of data means that MindSpot has been able to monitor trends in those seeking mental health services from MindSpot throughout the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia and compare results with a pre-COVID sample. In a series of studies, we have reported trends in service use, symptoms, and concerns (Staples et al., 2020; Titov et al., 2020b). We have observed significant increases in service demand, however our results to date have also suggested a high level of resilience in the Australian community, with no significant score increases on standardised measures of depression or psychological distress, and no increase in the number of people reporting suicidal thoughts or plans. While these results are reassuring, we have noted other impacts of COVID-19, such as feelings of worry, financial and economic difficulties, and social isolation, that may affect mental health in the longer term. Therefore, the current study examines characteristics and trends for all users, and also compares outcomes for users from Victoria relative to the rest of Australia, from 19th March until the easing of restrictions in Victoria on the 28th October.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and design

Assessment data and responses to questions about COVID-19 were collected from consecutive participants starting an assessment between 19th March and 28th October 2020 (n = 14,703). All participants gave consent for their results to be used for quality assurance and service improvement activities. Ethical approval for collection of this data was obtained from the Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee (5201200912).

2.2. Measures

Participants provided demographic data, responses to questions regarding the impact of COVID-19, and responses to standardised symptom measures online, as previously described (Titov et al., 2020a). We used the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) as a measure of symptoms of generalized anxiety (Spitzer et al., 2006), and the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale (PHQ-9) as a measure of symptoms of depression (Kroenke et al., 2001). We also used the Kessler 10-Item Plus Scale (K-10+) as a measure of symptoms of general psychological distress and functional impairment (Kessler et al., 2002). The first ten items comprise the K-10 scale, and four additional questions assess the functional impact of the distress. In the current report we analysed two of the additional questions, which asked participants the number of full and part days within the previous four weeks that they had been unable to perform their usual work or activities.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Chi-square analyses and generalized linear models were used to compare eight by four-week time periods during COVID-19 with a baseline comparison period prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (1st to 28th September 2019; n = 1650). The comparison period represents a typical cohort and has been used as a baseline in our previous reports (Staples et al., 2020; Titov et al., 2020a; Titov et al., 2020b). Participants from Victoria (n = 4203) were compared to participants from the rest of Australia (n = 10,500). A significance level of 0.05 was used for all tests, with Bonferonni adjustments made for multiple comparisons.

3. Results

3.1. Service use

Over the COVID-19 time periods to date, we observed two peaks in service demand (Fig. 1). In Weeks 5–8 (corresponding to 16th April 2020 to 13th May 2020), a total 2096 assessments were started, most of which were from the state of New South Wales (33%). During Weeks 21–24 (corresponding to 6th August 2020 to 2nd September 2020), a total of 2065 assessments of started, most of which were from the state of Victoria (34%).

Fig. 1.

Assessments started during COVID-19 in Australia, over time and by state.

3.2. Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. We observed a significant decrease in the mean age of participants over the reported time periods, from 35 years at baseline and the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, to 32 years by Weeks 29–32. The proportions of females starting an assessment have generally been higher during the pandemic compared to baseline. Levels of reported employment dropped from the baseline of 61% to 53% in early weeks but returned toward baseline in later weeks. Self-reported symptoms of current depression have not changed significantly over the reported time periods. Self-reported current anxiety with recent onset (within two weeks) was highest in Weeks 1–4. The proportions of participants reporting suicidal thoughts or plans have decreased over the COVID-19 periods compared to baseline.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics over 32 weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia.

| Baseline |

Weeks 1–4 |

Weeks 5–8 |

Weeks 9–12 |

Weeks 13–16 |

Weeks 17–20 |

Weeks 21–24 |

Weeks 25–28 |

Weeks 29–32 |

Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date range |

1/9/19 to 28/9/19 |

19/3/20 to 15/4/20 |

16/4/20 to 13/5/20 |

14/5/20 to 10/6/20 |

11/6/20 to 8/7/20 |

9/7/20 to 5/8/20 |

6/8/20 to 2/9/20 |

3/9/20 to 30/9/20 |

1/10/20 to 28/10/20 |

|

| Assessments started | n = 1650 | n = 1668 | n = 2096 | n = 1690 | n = 1821 | n = 1736 | n = 2065 | n = 1779 | n = 1848 | |

| Mean age (SD) and range | 35.0 (13.5) 18–86 |

34.9 (13.6) 18–92 |

35.9 (14.3) 18–100 |

35.9 (13.9) 18–93 |

34.2 (13.5) 18–83 |

34.4 (13.1) 18–84 |

34.2 (12.9) 18–83 |

32.8 (12.9) 18–91 |

32.0 (12.8) 18–82 |

F = 16.298 p < .001*** |

| Proportion female | 72.9% (1203/1650) | 76.9% (1282/1668) | 77.0% (1613/2096) | 75.2% (1271/1690) | 76.7% (1396/1821) | 75.6% (1313/1736) | 72.5% (1497/2065) | 77.1% (1372/1779) | 76.1% (1406/1848) | ꭙ2 = 111.831 p < .001*** |

| Capital city or surrounding suburbs | 60.4% (932/1544) | 58.7% (904/1541) | 64.1% (1245/1941) | 60.5% (926/1530) | 58.8% (1015/1725) | 62.3% (1035/1660) | 66.9% (1312/1961) | 61.9% (1020/1647) | 61.6% (1069/1736) | ꭙ2 = 42.881 p < .001*** |

| Born in Australia | 77.8% (1163/1500) | 78.6% (1188/1512) | 77.1% (1471/1911) | 78.3% (1194/1524) | 78.3% (1354/1729) | 78.2% (1302/1664) | 75.5% (1480/1959) | 78.6% (1298/1651) | 78.2% (1357/1735) | ꭙ2 = 9.414 p = .309 |

| Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islandera | 4.7% (55/1163) | 3.3% (39/1188) | 4.0% (59/1471) | 3.7% (44/1194) | 5.2% (70/1354) | 3.0% (39/1302) | 3.4% (50/1480) | 3.8% (49/1298) | 4.3% (58/1357) | ꭙ2 = 15.368 p = .052 |

| University degree | 42.4% (654/1543) | 41.2% (633/1535) | 44.2% (855/1936) | 42.3% (648/1531) | 42.0% (722/1721) | 43.8% (726/1658) | 50.2% (979/1952) | 44.4% (729/1642) | 41.1% (707/1722) | ꭙ2 = 46.304 p < .001*** |

| Employed full-time or part-time | 60.8% (939/1544) | 52.8% (811/1536) | 55.8% (1081/1939) | 58.5% (895/1530) | 57.6% (989/1718) | 57.5% (955/1661) | 60.3% (1184/1962) | 56.2% (925/1645) | 57.5% (994/1729) | ꭙ2 = 30.062 p < .001*** |

| Married (registered or de facto) | 36.9% (568/1541) | 34.7% (534/1539) | 35.5% (686/1934) | 35.9% (548/1526) | 35.3% (609/1724) | 36.7% (606/1652) | 34.9% (685/1962) | 33.5% (551/1647) | 32.1% (555/1729) | ꭙ2 = 14.033 p = .081 |

| Self-reported depression | 69.5% (1062/1528) | 69.0% (1037/1502) | 69.0% (1298/1887) | 69.3% (1045/1509) | 70.9% (1182/1667) | 68.1% (1100/1615) | 65.9% (1265/1919) | 69.2% (1115/1611) | 68.0% (1135/1670) | ꭙ2 = 12.703 p = .122 |

| Depression < two weeks | 4.0% (43/1062) | 6.8% (71/1037) | 5.9% (76/1298) | 6.2% (65/1045) | 5.6% (66/1182) | 4.7% (52/1100) | 4.4% (56/1265) | 6.3% (71/1115) | 4.6% (52/1135) | ꭙ2 = 45.925 p = .053 |

| Self-reported anxiety | 86.2% (1317/1528) | 89.3% (1341/1502) | 87.1% (1644/1887) | 86.9% (1311/1509) | 86.0% (1433/1667) | 87.4% (1411/1615) | 86.2% (1654/1919) | 88.0% (1418/1611) | 85.6% (1430/1670) | ꭙ2 = 378.576 p < .001*** |

| Anxiety < two weeks | 3.0% (39/1317) | 5.4% (73/1341) | 3.0% (49/1644) | 3.7% (49/1311) | 2.9% (41/1433) | 3.1% (45/1411) | 3.0% (50/1654) | 2.8% (39/1418) | 2.3% (33/1430) | ꭙ2 = 29.443 p < .001*** |

| Suicidal thoughts | 30.6% (423/1383) | 27.5% (367/1334) | 27.8% (476/1714) | 26.9% (363/1350) | 28.0% (421/1505) | 29.1% (428/1469) | 24.4% (428/1752) | 28.3% (416/1469) | 28.9% (428/1482) | ꭙ2 = 18.684 p < .05* |

| Suicidal intentions or plans |

3.7% (51/1383) | 2.9% (39/1334) | 2.2% (38/1714) | 2.1% (29/1350) | 2.0% (30/1505) | 2.8% (41/1469) | 1.4% (25/1752) | 3.2% (47/1469) | 3.3% (49/1482) | ꭙ2 = 24.743 p < .01** |

Only participants who answered yes to being born in Australia were asked about Indigenous status. Significance: ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

3.3. Psychological symptoms and days out of role

Mean symptom scores on the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and K-10 scales were compared across the eight COVID-19 time periods, and results for Victoria were compared to the rest of Australia. Mean whole days out of role, and mean part days out of role due to health symptoms were also analysed. Results are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences between Victoria and elsewhere on the PHQ-9 (F = 0.197, p = .657), GAD-7 (F = 0.266, p = .606), or K-10 (F = 1.372, p = .242), and there were no state by time-period interactions (K-10: F = 0.216, p = .982; PHQ-9: F = 0.476, p = .853; GAD-7: F = 0.393, p = .907).

Table 2.

Symptom scores during COVID-19: comparison of Victoria with the rest of Australia.

| Baseline |

Weeks 1–4 |

Weeks 5–8 |

Weeks 9–12 |

Weeks 13–16 |

Weeks 17–20 |

Weeks 21–24 |

Weeks 25–28 |

Weeks 29–32 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date range | 1/9/19 to 28/9/19 | 19/3/20 to 15/4/20 | 16/4/20 to 13/5/20 | 14/5/20 to 10/6/20 | 11/6/20 to 8/7/20 | 9/7/20 to 5/8/20 | 6/8/20 to 2/9/20 | 3/9/20 to 30/9/20 | 1/10/20 to 28/10/20 |

| Total for Australia | n = 1650 | n = 1668 | n = 2096 | n = 2098 | n = 1821 | n = 1736 | n = 2065 | n = 1779 | n = 1848 |

| PHQ-9 | 14.3 (6.2) | 14.4 (6.2) | 14.4 (6.2) | 14.1 (6.1) | 14.0 (6.2) | 14.0 (6.0) | 13.4 (6.1)⁎⁎ | 14.1 (6.2) | 14.1 (6.1) |

| GAD-7 | 12.1 (5.2) | 12.5 (5.3) | 12.2 (5.3) | 11.9 (5.2) | 11.9 (5.3) | 11.9 (5.1) | 11.3 (5.3)⁎⁎⁎ | 11.8 (5.2) | 11.9 (5.1) |

| K-10 | 31.2 (7.6) | 31.4 (7.8) | 31.0 (7.6) | 30.7 (7.4) | 30.9 (7.6) | 30.8 (7.4) | 30.0 (7.4)⁎⁎⁎ | 31.0 (7.5) | 31.1 (7.5) |

| Whole days out of role | 5.5 (7.4) | 6.1 (7.7) | 6.0 (7.7) | 6.3 (8.0) | 6.3 (8.1) | 6.1 (7.9) | 5.5 (7.2) | 6.6 (8.3) | 6.4 (7.8) |

| Part days out of role | 8.6 (8.0) | 9.0 (8.1) | 9.1 (8.2) | 9.5 (8.8) | 8.8 (8.5) | 8.7 (8.2) | 9.3 (8.6) | 9.7 (9.0) | 9.6 (8.8) |

| Victoria | 406/1650 | 431/1668 | 565/2096 | 415/2098 | 483/1821 | 559/1736 | 705/2065 | 539/1779 | 506/1848 |

| PHQ-9 | 13.7 (6.1) | 14.6 (6.2) | 14.6 (6.0) | 14.0 (6.2) | 13.7 (6.1) | 14.0 (6.1) | 13.3 (6.2) | 14.1 (6.2) | 14.1 (6.0) |

| GAD-7 | 11.6 (5.0) | 12.6 (5.3) | 11.9 (5.2) | 12.0 (5.2) | 11.9 (5.2) | 12.0 (5.1) | 11.3 (5.2) | 11.6 (5.1) | 11.8 (5.2) |

| K-10 | 30.8 (7.5) | 31.5 (7.7) | 30.8 (7.6) | 30.5 (7.4) | 30.6 (7.7) | 30.7 (7.7) | 29.8 (7.5) | 30.9 (7.4) | 31.2 (7.4) |

| Whole days out of role | 4.7 (6.3) | 6.0 (7.2) | 6.0 (7.7) | 6.6 (8.7) | 6.4 (8.0) | 6.3 (8.0) | 5.2 (6.8) | 6.9 (8.4) | 7.3 (8.1) |

| Part days out of role | 8.5 (7.9) | 9.0 (7.8) | 8.6 (7.8) | 9.8 (9.0) | 8.8 (8.2) | 8.2 (7.7) | 9.1 (8.1) | 10.2 (9.0) | 9.9 (8.5) |

| Other states and territories | 1244/1650 | 1237/1668 | 1531/2096 | 1275/2098 | 1338/1821 | 1177/1736 | 1360/2065 | 1240/1779 | 1342/1848 |

| PHQ-9 | 14.5 (6.3) | 14.3 (6.2) | 14.3 (6.3) | 14.2 (6.1) | 14.1 (6.3) | 14.0 (6.0) | 13.5 (6.0) | 14.1 (6.3) | 14.1 (6.1) |

| GAD-7 | 12.3 (5.2) | 12.5 (5.3) | 12.2 (5.3) | 11.9 (5.2) | 12.0 (5.3) | 11.9 (5.1) | 11.4 (5.3) | 11.8 (5.3) | 12.0 (5.1) |

| K-10 | 31.3 (7.6) | 31.4 (7.9) | 31.1 (7.5) | 30.8 (7.4) | 31.0 (7.5) | 30.8 (7.3) | 30.1 (7.4) | 31.1 (7.5) | 31.1 (7.5) |

| Whole days out of role | 5.8 (7.7) | 6.2 (7.9) | 5.9 (7.6) | 6.1 (7.8) | 6.2 (8.1) | 6.0 (7.8) | 5.6 (7.3) | 6.5 (8.2) | 6.1 (7.7) |

| Part days out of role | 8.7 (8.1) | 9.0 (8.2) | 9.3 (8.3) | 9.4 (8.7) | 8.9 (8.6) | 9.0 (8.4) | 9.3 (8.8) | 9.5 (9.0) | 9.5 (8.9) |

Table shows mean scores and standard deviations in parentheses. Significance of Bonferroni post-hoc tests: No significant differences between Victoria and the rest of the country.

Significantly different to baseline at p < .001.

Significantly different to baseline at p < .01.

There were significant differences in symptoms scores across the time periods on the K-10 (F = 4.931, p < .001), PHQ-9 (F = 3.808, p < .001) and GAD-7 (F = 6.222, p < .001). Post-hoc analysis revealed that mean scores during weeks 21–24 were significantly lower than baseline, despite this period (6/8/20 to 2/9/20) corresponding to a second peak in COVID-19 cases in Australia (primarily Victoria), and a peak in the number of people of contacting MindSpot (Fig. 1). We therefore looked at the frequency distribution of scores in weeks 21–24 compared to the baseline group. As shown in Fig. 2, there was an increase in the number of assessments started by participants with lower symptoms scores.

Fig. 2.

Frequency distribution of scores in Weeks 21–24 compared to baseline.

There were no significant overall differences between Victoria and elsewhere in the mean number of whole days out of role (F = 0.544, p = .461) or part days of role (F = 0.044, p = .834). There were significant differences across the time periods, with an increase in mean whole and part days out of role at Weeks 25–28, and Weeks 29–32. (Whole days out of role: F = 332.533, p < .001; part days out of role: F = 3.935, p < .001). There was also a significant state by time-period interaction for whole days out of role (F = 2.025, p < .05), with the increase at Weeks 29–32 continuing for Victoria but dropping for the rest of Australia.

3.4. Concern about COVID-19 in Victoria compared to the rest of Australia

Participants were asked about personal contact with COVID-19, their degree of concern, changes to their routine, and about the main difficulties they had experienced. Table 3 shows the responses of participants from Victoria, compared with the rest of Australia. While participants from Victoria were significantly more likely to know someone with COVID-19 or to have been diagnosed with it themselves, the majority of participants in this study reported no personal contact to date (93% of respondents from Victoria, and 97% of respondents from elsewhere in Australia).

Table 3.

Response to COVID-19 specific questions – Victoria compared to the rest of Australia.

| Victoria | Other states and territories | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have you, or has anyone you know, been diagnosed with COVID-19? | n = 3826 | n = 9540 | |

| No | 93.3% (3569) | 96.7% (9223) | ꭙ2 = 80.543 p < .001*** |

| Yes, myself | 0.3% (11) | 0.1% (6) | |

| Yes, someone I know | 6.3% (242) | 3.2% (308) | |

| Both myself and someone I know | 0.1% (4) | <0.1% (3) | |

| How concerned are you about COVID-19? | n = 3822 | n = 9554 | |

| Not at all concerned | 10.7% (410) | 15.9% (1517) | ꭙ2 = 134.015 p < .001*** |

| Slightly concerned | 36.1% (1381) | 40.8% (3900) | |

| Moderately concerned | 39.6% (1513) | 33.8% (3234) | |

| Extremely concerned | 13.6% (518) | 9.5% (903) | |

| Have you had to make any changes to manage the impact of COVID-19? | n = 3825 | n = 9540 | |

| No changes | 9.2% (352) | 15.8% (1504) | ꭙ2 = 275.753 p < .001*** |

| Slight changes | 29.0% (1110) | 36.2% (3454) | |

| Moderate changes | 33.2% (1270) | 29.9% (2849) | |

| Significant changes | 28.6% (1093) | 18.2% (1733) |

***p < .001

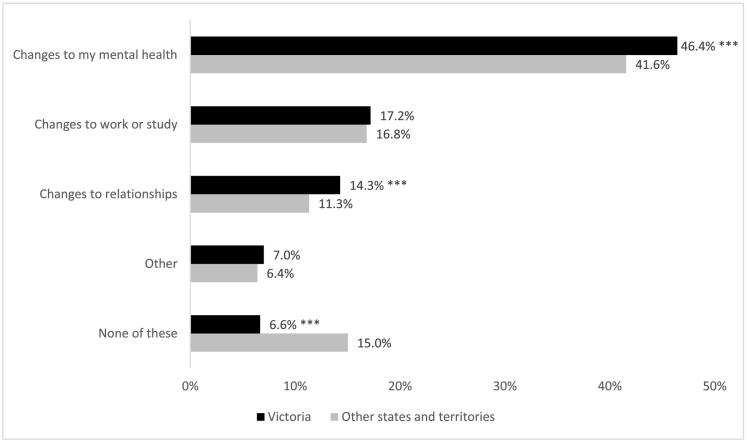

Participants from Victoria were significantly more likely to report extreme concern about COVID-19 and were more likely to have made significant changes to routines in response to the pandemic. Fig. 3 shows the trajectory of reported concern and change by week. Participants were also asked what was causing them the most difficulty during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 4). Only 6.6% of respondents from Victoria said they were not experiencing any difficulties, compared with 15.0% respondents from elsewhere in Australia. Difficulties due to changes in mental health, such as increased feeling of anxiety, were common around Australia, but significantly higher in Victoria (46.4% in Victoria compared to 41.6% elsewhere). Respondents from Victoria were also more likely to report difficulties due to changes in their relationships with family or friends (14.3% in Victoria compared to 11.3% elsewhere).

Fig. 3.

Reported levels of extreme concern and significant change due to COVID-19 by week - comparison of Victoria with other states and territories.

Fig. 4.

Main reported difficulties due to COVID-19 in Victoria compared to the rest of Australia.

Question was introduced in Week 6. ***Significant at p < .001.

Most participants were using helpful strategies to manage the psychological difficulties imposed by COVID-19 (Fig. 5). Less than 15% of respondents had not found any strategies to be helpful. Most commonly, people reported that they were maintaining social connections online or via telephone, establishing new routines, and/or staying physically active. Use of these strategies was higher in Victoria compared to elsewhere in Australia.

Fig. 5.

Use of helpful strategies in Victoria compared to the rest of Australia.

Question was introduced in Week 6. Respondents could choose multiple responses, except when “none of these” was indicated.

4. Discussion

This paper reports service use and symptoms for users of a digital mental health clinic during the first 32 weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. We have observed two peaks in service demand to date, the first in the early weeks of the pandemic (mid-March to mid-April 2020), and the second corresponding to a period in August–September 2020, when COVID-19 transmission was high in Victoria and the state was in a protracted second lockdown (Saul et al., 2020; Victorian Government, 2020b). Interestingly, the mean symptom scores on standardised measures of distress (K-10), depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7), decreased during this second peak in service use, attributed to an increased number of participants from Victoria with mild to moderate symptoms contacting the Clinic.

While we have not observed an increase in standardised symptom scores suggestive of increasing severity of mental health disorders in the community, we have seen a significant impact of COVID-19. Most participants report some level of concern about the virus, and most people report making changes to manage the psychological impact of the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, this has been particularly true of participants from Victoria, who experienced a long period of lockdown in an effort to reduce COVID-19 transmission in the state. Of interest, despite the closure of many businesses, and a reduction in the number of people who reported being employed, we did not find a significant increase in self-reported days out of role from that state. A possible explanation is the ready adaptation of many people to working remotely. Consistent with this, we also found that most people have implemented strategies to help them face the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic.

It should be noted that our study focused on the characteristics of people choosing to use the MindSpot Clinic and does not provide population-wide estimates of severity or distress. Further, we note that the results may not be relevant to other parts of the world, where transmission levels are considerably higher. Despite these limitations, a key strength of the study is the ongoing collection and reporting of symptom levels in large and consecutive samples of people from all parts of Australia during very challenging times, and the large sample size allows a naturalistic comparison between geographical regions of Australia differentially affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Conclusion

While Australia has been relatively successful in containing COVID-19 infections, Victoria experienced a peak in community transmission in August–September 2020. Unsurprisingly, the current report found increased levels of concern about COVID-19 in Victoria during this period, relative to the rest of Australia. Nonetheless, a significant proportion of our cohort have implemented coping strategies to help them manage the impact of the pandemic. At this point in time, our results continue to suggest that at a community level, we are observing normal psychological responses to an unprecedented situation rather than a widespread mental health crisis. This distinction is important as we develop individually appropriate and proportional mental health system responses, which recognise that in the context of COVID-19, many of the stressors facing patients may be increasingly psychosocial - including financial, employment, relationship, and other pressures.

However, while we have not yet found evidence of increasing anxiety or depressive disorders in our cohort, it is likely that the long-term or chronic consequences of COVID-19 are yet to fully emerge. Until an effective vaccine is widely available, it is also likely that different regions will continue to experience episodes of infections, resulting in the temporary re-introduction of restrictions which will in turn affect access to, or availability of, traditional mental health services. Given the importance of ensuring access and availability, we encourage mental health services in Australia and overseas to continue to offer care via digital means, and in the interests of supporting informed decision making by funders and planners, we encourage these services to monitor and report outcomes.

Sources of funding

MindSpot is funded by the Australian Department of Health. There was no external funding for this study.

Access to data and manuscript review

All authors had access to the data and reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: N. Titov and B. Dear are authors and developers of the treatment courses used at the MindSpot Clinic but derive no personal or financial benefit from them.

References

- Australian Government Department of Health; 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19) current situation and case numbers. https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/coronavirus-covid-19-current-situation-and-case-numbers Retrieved 31 October 2020, from.

- Bartone T., Hickie I., McGorry P. 2020. COVID-19 Impact Likely to Lead to Increased Rates of Suicide and Mental Illness. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J., Tran T.D., Hammargerg K., Sastry J., Nguyen H., Rowe H., Popplestone S., Stocker R., Stubber C., Kirkman M. Preprint; Medical Journal of Australia: 2020. Mental health of people in Australia in the first month of COVID-19 restrictions: a national survey. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrie D. NewsGP; 2020. Why does the coronavirus fatality rate differ so much around the world? https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/clinical/why-does-the-coronavirus-fatality-rate-differ-so-m Retrieved 22/11/2020, from.

- Kessler R.C., Andrews G., Colpe L.J., Hiripi E., Mroczek D.K., Normand S.L., Walters E.E., Zaslavsky A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan B., Edmonds C., Scott S. ABC News; Sydney, Australia: 2020. Coronavirus Pandemic Plan for Mental Health Too Small, Suicides Likely to Increase, Expert Says. [Google Scholar]

- Saul A., Scott N., Crabb B.S., Majumdar S.S., Coghlan B., Hellard M.E. Impact of Victoria's Stage 3 lockdown on COVID-19 case numbers. Med. J. Aust. 2020;213(11):494–496.e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50872. Epub 2020 Nov 23. PMID: 33230817; PMCID: PMC7753834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SBS News . 2020. NSW Hits 22 Days With No Local Coronavirus Cases, While Victoria Marks 30 ‘Donut Days’. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staples L., Nielssen O., Kayrouz R., Cross S., Karin E., Ryan K., Dear B., Titov N. Rapid report 2: symptoms of anxiety and depression during the first 12 weeks of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Australia. Internet Interv. 2020;22:100351. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2020.100351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Dear B.F., Staples L.G., Bennett-Levy J., Klein B., Rapee R.M., Andersson G., Purtell C., Bezuidenhout G., Nielssen O.B. The first 30 months of the MindSpot Clinic: evaluation of a national e-mental health service against project objectives. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2017;51(12):1227–1239. doi: 10.1177/0004867416671598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Dear B., Nielssen O., Wootten B., Kayrouz R., Karin E., Genest B., Bennett-Levy J., Purtell C., Bezuidenhout G., Tan R., Minissale C., Thadhani P., Webb N., Willcock S., Andersson G., Hadjistavropoulos H., Mohr D., Kavanagh D., Cross S., Staples L. Health in press; Lancet Digital: 2020. User characteristics and outcomes from a national digital mental health service: an observational study of registrants of the Australian MindSpot Clinic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Staples L., Kayrouz R., Cross S., Karin E., Ryan K., Dear B., Nielssen O. Rapid report: early demand, profiles and concerns of mental health users during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Internet Interv. 2020;21:100327. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2020.100327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Government . 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Business Support and the Industry Coordination Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Government Coronavirus update for Victoria - Saturday 21 November. 2020. https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/coronavirus-update-victoria-21-november-2020 Retrieved 22/11/2020, 2020, from.

- Woodley M. NewsGP; RACGP: 2020. How Does Australia Compare in the Global Fight Against COVID-19? [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations During the COVID-19 Outbreak. [Google Scholar]