Abstract

Background

Tacrolimus is a powerful immunosuppressant and has been widely used in organ transplantation. In order to further explore the role of tacrolimus in liver transplantation, we conducted network pharmacology analysis.

Methods

GSE100155 was obtained from the GEO database, and the DEGs of liver transplantation were analyzed. The 2D structure of tacrolimus was obtained from the National Library of Medicine, and the pharmacophore model of tacrolimus was predicted using the online tool pharmmapper. Then a network of tacrolimus and target genes was constructed through network pharmacology, and visualization and GO enrichment analysis was performed through Cytoscape. In addition, we also analyzed the correlation between key genes and immune infiltrating cells. The data of GSE84908 was used to verify the changes of key gene expression levels after tacrolimus treatment.

Results

The results of network pharmacological analysis showed that tacrolimus had 43 target genes, and the GO enrichment results showed many potential functions. Further analysis found that there were 5 key target genes in DEGs, and these 5 genes were significantly down-regulated in liver transplant patients. Another important finding was that 5 genes were significantly related to some immune infiltrating cells. The results of the GSE84908 data analysis showed that after tacrolimus treatment, the expression of DAAM1 was significantly increased (p = 0.015).

Conclusion

Tacrolimus may inhibit the human immune response by affecting the expression of DAAM1 in liver transplant patients.

Keywords: Tacrolimus, Network pharmacology, GEO, Liver transplantation

Abbreviations: DEGs, Differentially expressed genes; GO, Gene Ontology; PPI, protein-protein interaction

1. Introduction

Liver transplantation is the only effective treatment for acute or chronic liver failure. After liver transplantation, acute allograft rejection is still an important cause of the disease. If not treated in time, it may cause graft dysfunction or failure. Transplant immunology is a constantly changing science. Further elucidation of the cellular mechanisms involved in the interaction between rejection and graft tolerance will be welcomed by transplant doctors and patients. The purpose of treatment is to maximize the effectiveness of immunosuppressive therapy and reduce the adverse side effects of immunosuppressive therapy, so as to improve the quality of the graft, extend the life of the graft, and extend the life of the patient. Immunosuppressive agents refer to drugs that have an inhibitory effect on the immune response of the body, which can inhibit the proliferation and function of cells related to the immune response, such as T cells, B cells, and other macrophages, thereby achieving the effect of reducing the immune response of antibodies (Schutte-Nutgen et al., 2018, Reske et al., 2015, Mika and Stepnowski, 2016, Neuhaus et al., 2007, Nguyen and Shapiro, 2014, Wang et al., 2020). Although the historical development of immunosuppressive agents is not long, it has made remarkable achievements in the field of organ transplantation. At present, organ transplants such as liver transplantation, kidney transplantation, skin transplantation, and heart transplantation have reached a fairly successful level, of which kidney transplantation and liver transplantation have the most clinical applications (Gorantla et al., 2000, Ivulich et al., 2018, Lee and Gabardi, 2012, Gaston, 2006, Khush and Valantine, 2009, Langman and Jannetto, 2016, Xie, 2010).

Tacrolimus (Tac, or FK506, trade name Prograf), is a new type of powerful immunosuppressant with a macrolide structure extracted from the fermentation broth of Streptomyces tsukubaensis by Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Company of Japan in 1984 (Cross and Perry, 2007, Bowman and Brennan, 2008 Mar, Zhang et al., 2018, Kalt, 2017). In 1994, Tac was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for liver transplantation. Tacrolimus belongs to calmodulin inhibitors. Its immunosuppressive mechanism is similar to cyclosporin A, but its ability to inhibit T cell activity is 10–100 times stronger than cyclosporin A. Its mechanism of action is mainly to combine with FK506 binding protein (FKBP) in the cytoplasm of T lymphocytes in the body to form the FK506-FKBP complex, which inhibits the phosphorylase activity of calcineurin phosphatase, thereby inhibiting Ca2 influx. Due to the loss of the ability of T cell nuclear factor to dephosphorylate, the transcription of various genes such as interleukin 2 (IL-2), IL-2 receptor, and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) is inhibited and exerted inhibition. The role of anti-host reaction and delayed allergy (Pennington and Park, 2015, Posadas Salas and Srinivas, 2014, Rallis et al., 2007, Ormerod, 2005, Lichvar et al., 2019). However, because tacrolimus has certain side effects on patients, and the individualization of different patients varies greatly, strengthen the study of the molecular mechanism of tacrolimus is needed. In recent years, the development of computer technology has enabled us to analyze the components of drugs through computers and systematically analyze the effects of drugs on diseases through network pharmacology, which has greatly improved our understanding of drug molecular networks and their properties.

The data of this study mainly comes from the dataset of the GEO public platform. Through the analysis of the GSE100155 data set, DEGs after liver transplantation were obtained. Through the National Library of Medicine and the online tool pharmmapper, a regulatory network of tacrolimus and target genes was constrcuted. There were 5 genes in the intersection of the DEGs and the tacrolimus target genes, these genes were selected as key genes. In addition, the correlation between key genes and immune infiltrating cells was analyzed and then the levels of key genes after tacrolimus treatment through GSE84908 data were investigated. This study provides new insights into the role of tacrolimus in liver transplantation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data collection

GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) was a public functional genomics data repository. The GSE100155 (liver transplant) and GSE84908 (comparison of gene expression of human mesangial cells after 24 h Tacrolimus vs. control) data were obtained from the GEO database. The structure of the tacrolimus was obtained from the National Library of Medicine (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Then we used the online tool pharmmapper (http://www.lilab-ecust.cn/pharmmapper/) to predict the pharmacophore model of tacrolimus (Liu et al., 2010, Wang et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2017). Data were downloaded from the publicly available database hence it was not applicable for additional ethical approval.

2.2. Identification of DEGs

The “limma” package (Ritchie et al., 2015) was used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the GSE100155 data set (whole blood-Liver Transplant-Transplant and whole blood-Liver Transplant-Control). Genes with | log FC | > 1 and adjusted p value < 0.05 were defined as DEGs (Li et al., 2020, Fan et al., 2019, Zeng et al., 2020, Voorwerk et al., 2019).

2.3. Construction of network and GO analysis

In order to further analyze the molecular mechanism of tacrolimus, we used online tools (STRING; https://string-db.org/) to predict the interaction between target genes, with confidence > 0.9 as the cut-off criterion, and hide disconnected nodes in the network. Then constructed a regulatory network of compounds and target genes through Cytoscape 3.7.2. In addition, the Cytoscape plug-in ClueGO was used to perform Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis on target genes.

2.4. Estimation of immune cell type fractions

CIBERSORT is a powerful analysis tool that uses gene expression signatures composed of 547 genes. It uses a deconvolution algorithm to characterize each immune cell subtype and accurately quantify the components of different immune cells. A p < 0.05 was set as the cut-off criterion.

2.5. Statistics

In this paper, R software v3.6.3 was used to carry out systematic statistical research and calculation. The R software packages “ggsignif”, “ggpubr” and “ggplot2″ were used to make box plots and quantitative statistical studies of differential expression. If not specified above, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Construction tacrolimus and target genes network

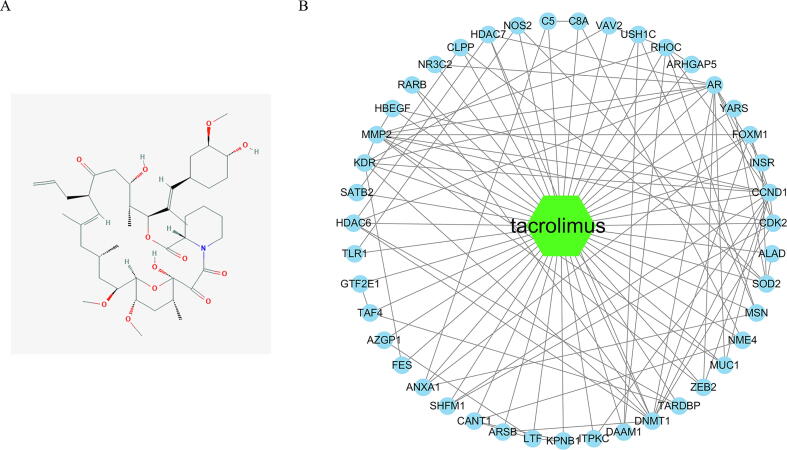

The 2D structure of tacrolimus was obtained from the National Library of Medicine, as shown in Fig. 1A. Then we predicted the pharmacophore model of tacrolimus through the online database pharmmapper, and then we analyzed and annotated the proteins that might bind, and obtained 58 target genes (Supplemental Table 1). We used an online tool (STRING; https://string-db.org/) to predict the interaction between target genes, with a confidence level > 0.9 as the cut-off standard, and hide disconnected nodes in the network, and obtained 43 Interacting proteins. Then we visualized it through Cytoscape and constructed a network between tacrolimus and the target genes (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Construction tacrolimus and target genes Network. (A) The 2D structure of tacrolimus; (B) The Network of tacrolimus and target genes.

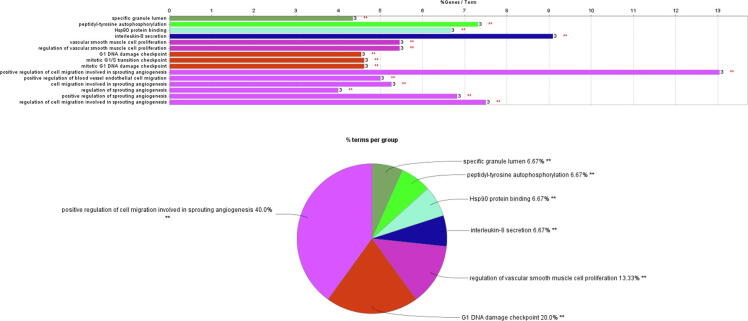

3.2. ClueGO analysis result

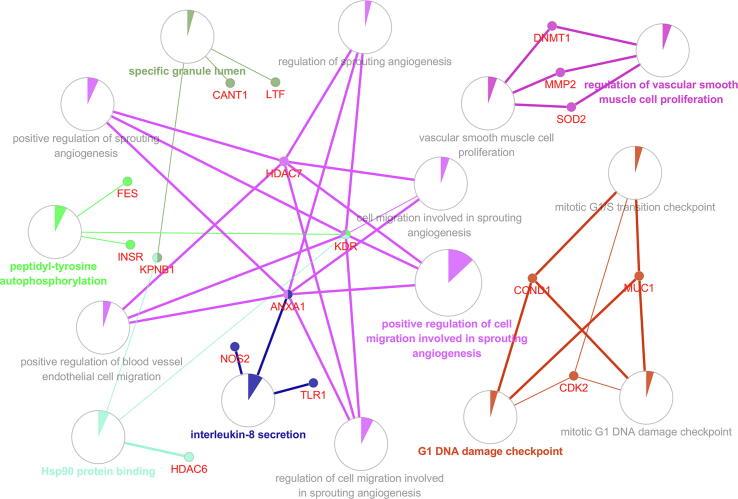

For further analysis of target genes, we used the Cytoscape plug-in ClueGO to analyze the biological process, molecular function, and cellular component of the gene ontology. ClueGO analysis results show that we have enriched a total of 15 GO terms (Fig. 2; Supplemental Table 2), of which positive regulation of cell migration involved in sprouting angiogenesis has the highest enrichment degree, accounting for 40% (Figure Supplementary figure 1).

Fig. 2.

GO enrichment network. The nodes in the network represent a specific GO term. The edges connecting the nodes are based on the kappa statistic that measures the overlap of shared genes between terms.

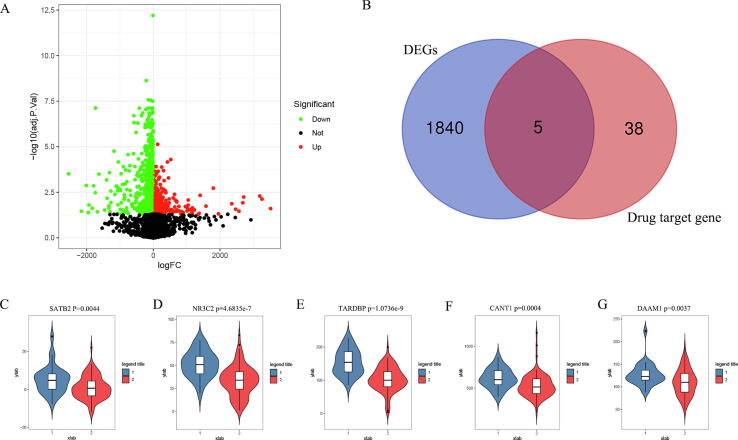

3.3. Identification of DEGs and key genes

In order to identify the DEGs in liver transplantation, the GSE100155 dataset was downloaded from the GEO database. There were 30 control groups and 94 condition groups. The analysis results showed that there were 1845 DEGs in total (Fig. 3A). The results of the Venn diagram showed that there were 5 drug target genes in DEGs (Fig. 3B). Another important finding was that the expression levels of these 5 genes (SATB2 p = 0.0044; NR3C2 p = 4.6835e-7; TARDBP p = 1.0736e-9; CANT1 p = 0.0004; DAAM1 p = 0.0037) were significantly decreased in condition groups (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Identification of key genes. (A) Identification of DEGs; (B) There were 5 genes in the intersection of DEGs and target genes; (C–G) 5 genes in the liver transplantation group were significantly down-regulated; 1 was the control groups, 2 was the liver transplantation groups.

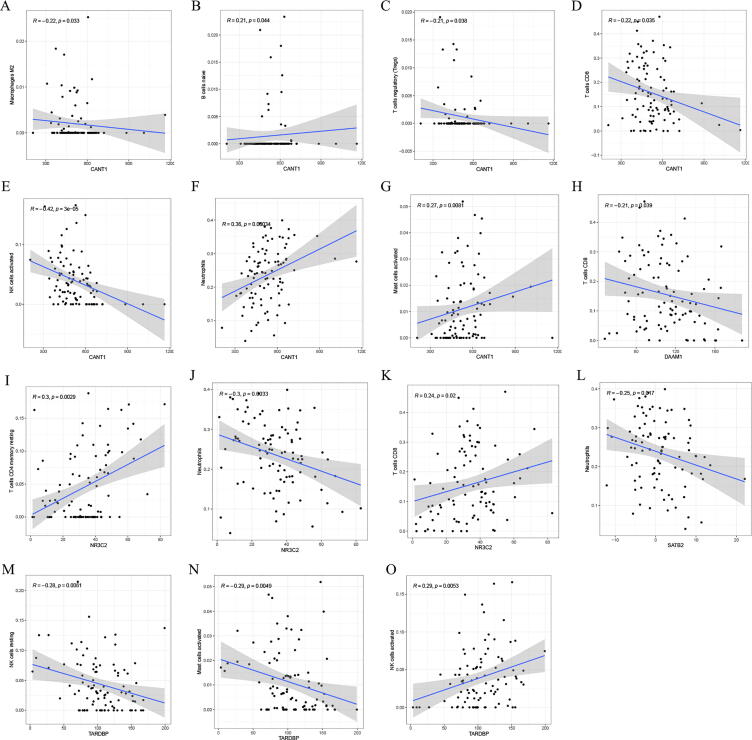

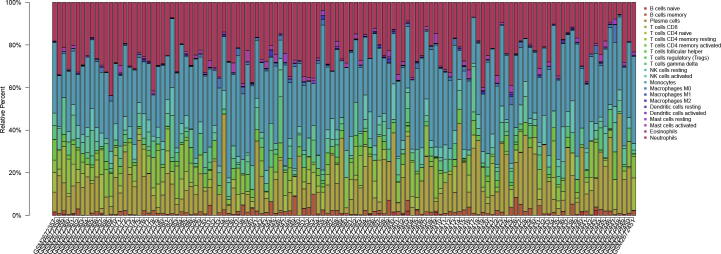

3.4. The relationship between key genes and immune infiltrating cells

In order to explore the relationship between immune infiltrating cells and key genes, the CIBERSORT algorithm was used to evaluate the composition of 22 immune cells in the GSE100155 (Figure Supplementary figure 2). The results (Fig. 4A–O) show that CANT1 has a negative correlation with Macrophages M2 (R = −0.22, p = 0.033), T cells regulatory (R = −0.21, p = 0.038), T cells CD8 (R = −0.22, p = 0.035) and NK cells activated (R = −0.42, p = 3e-05). CANT1 has a positive correlation with B cells native (R = 0.21, p = 0.044), Nautrophils (R = 0.36, p = 0.00034), and Mast cells activated (R = 0.27, p = 0.0081). DAAM1 has a negative correlation with T cells CD8 (R = -0.21, p = 0.039). NR3C2 has a positive correlation with T cells CD4 memory resting (R = 0.3, p = 0.0029), T cells CD8 (R = 0.24, p = 0.02), and a negative correlation with Neutrphils (R = −0.36, p = 0.0033). SATB2 has a negative correlation with Neutrphils (R = −0.25, p = 0.017). TARDBP has a negative correlation with NK cells resting (R = −0.28, p = 0.0061), Mast cells activated (R = -0.29, p = 0.0049), and a positive correlation with NK cells activated (R = 0.29, p = 0.0053).

Fig. 4.

Analysis of the correlation between genes and immune infiltrating cells. (A–O) The relationship between key genes and immune infiltrating cells.

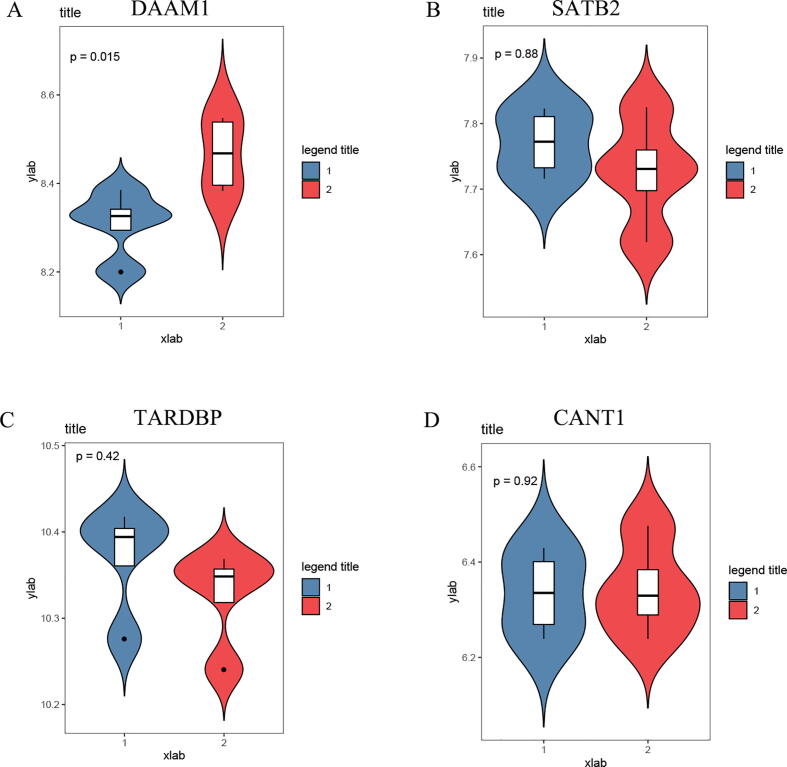

3.5. Tacrolimus may increase the expression of DAAM1

To further verify the influence of tacrolimus on the expression of these key genes, GSE84908 data was obtained from the GEO database. From the results (Fig. 5), we found that the expression level of DAAM1 (p = 0.015) was significantly increased after 24 h tacrolimus stimulus. Therefore, DAAM1 may be an important target for tacrolimus.

Fig. 5.

Tacrolimus may increase the expression of DAAM1. (A–D) Changes in gene expression levels after tacrolimus stimulation; 1 was the control groups, 2 was the tacrolimus stimulation groups.

4. Discussion

Immunosuppressants are widely used in patients undergoing organ transplantation, but their safety and effectiveness should be considered. Tacrolimus has been used as a first-line immunosuppressant after liver transplantation in adults and children (Ge et al., 2019, Staatz et al., 2004, Wallin et al., 2011). However, due to the large individual differences in the oral bioavailability of tacrolimus, some patients still have adverse reactions (Suh et al., 2016, McDiarmid, 1998, Song et al., 2018, Woillard et al., 2017). The therapeutic index of tacrolimus is narrow, and the potential adverse consequences of sub-therapeutic and toxic concentrations are serious, and patient exposure to the drug needs to be closely monitored. Therefore, units that introduce tacrolimus imitation preparations must take measures to prevent negligence or unsupervised substitution of different preparations, especially when both tacrolimus preparations can be released immediately or sustained release. In addition to intentional switching, patients should only use a single dosage form of tacrolimus maintenance therapy. In order to improve the transplanted organs and the survival rate of patients requires further research on the molecular mechanism of tacrolimus.

In this study, we first predicted the pharmacophore model of tacrolimus, then analyzed and annotated the proteins that might bind, and obtained 58 target genes. The online tool STRING was used to predict the protein–protein interaction network, which was visualized by Cytoscape, and the regulatory network between the tacrolimus and the target genes was constructed (Fig. 1A). ClueGO analysis results show that we have enriched a total of 15 GO terms (specific granule lumen, peptidyl-tyrosine autophosphorylation, Hsp90 protein binding, interleukin-8 secretion, vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, G1 DNA damage checkpoint, mitotic G1/S transition checkpoint, mitotic G1 DNA damage checkpoint, positive regulation of cell migration involved in sprouting angiogenesis, positive regulation of blood vessel endothelial cell migration, cell migration involved in sprouting angiogenesis, regulation of sprouting angiogenesis, positive regulation of sprouting angiogenesis, and regulation of cell migration involved in sprouting angiogenesis). The results of the Supplementary Table 2 and Figure Supplementary figure 1 indicate the degree of enrichment of target genes and the percentage of different GO terms. In addition, through the analysis of GSE100155, we identified DEGs after liver transplantation, and we found that DEGs and tacrolimus target genes have 5 intersection genes (SATB2, NR3C2, TARDBP, CANT1, and DAAM1). We also analyzed the correlation between these 5 genes and immune infiltrating cells. Another important finding is that these 5 genes are significantly decreased after liver transplantation, but DAAM1 expression will be significantly increased after tacrolimus stimulation. DAAM1 has a negative correlation with T cells CD8 (R = −0.21, p = 0.039).

Disheveled-associated activator of morphogenesis 1 (DAAM1) is a Formin protein, which has been shown to be involved in the regulation of breast cancer metastasis, and has the ability to promote metastasis and invasion of various tumors (Xiong et al., 2018, Mei et al., 2019, Mei et al., 2020, Dai et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2018). However, there is no literature report on the role of DAAM1 in liver transplantation. In this study, we constructed the regulatory network of tacrolimus and target genes, identified the key genes, and analyzed the correlation between the key genes and immune infiltrating cells. In addition, we also analyzed the changes in the expression levels of key genes after tacrolimus treatment. The results show that tacrolimus can increase the expression of DAAM1, and DAAM1 has a negative correlation with T cells CD8. Therefore, we guess that tacrolimus can inhibit the body's immune response by acting on DAAM1. These results provide new insights into the role of tacrolimus in liver transplantation. The cost of immunosuppressive therapy is still high. Tacrolimus, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil can all be used as immunosuppressants, but the quality, safety and effectiveness of the drug should be particularly noteworthy. However, this study contains some limitations. Although the results obtained from network analysis implicated the function of tacrolimus in liver transplantation, the data was just extracted from two databases, more databases are needed to concrete our conclusion. In addition, the in vitro or in vivo experiments were lacked to verify our results. More studies are needed to be preformed in the future research to further elaborate tacrolimus role in liver transplantation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The information of this study is obtained by the GEO, and the National Library of Medicine database. We are grateful to them for the source of data used in our study.

Author’s contributions

Lijian Chen and Yuming Peng performed data analysis work and aided in writing the manuscript. Chunyi Ji, Miaoxian Yuan, and Qiang Yin design the study, assisted in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Scientific Research Project of Hunan Provincial Health Commission (20200737).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.12.050.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Supplementary figure 1.

Supplementary figure 2.

References

- Bowman L.J., Brennan D.C. The role of tacrolimus in renal transplantation. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2008;9(4):635–643. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.4.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross S.A., Perry C.M. Tacrolimus once-daily formulation: in the prophylaxis of transplant rejection in renal or liver allograft recipients. Drugs. 2007;67(13):1931–1943. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767130-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai B., Shen Y., Yan T. Wnt5a/ROR1 activates DAAM1 and promotes the migration in osteosarcoma cells. Oncol. Rep. 2020;43(2):601–608. doi: 10.3892/or.2019.7424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z., Xiao K., Lin J. Functionalized DNA enables programming exosomes/vesicles for tumor imaging and therapy. Small. 2019;15(47) doi: 10.1002/smll.201903761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston R.S. Current and evolving immunosuppressive regimens in kidney transplantation. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2006;47(4 Suppl 2):S3–S21. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge P., Wang W., Li L. Profiles of immune cell infiltration and immune-related genes in the tumor microenvironment of colorectal cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019;118 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorantla V.S., Barker J.H., Jones J.W., Jr Immunosuppressive agents in transplantation: mechanisms of action and current anti-rejection strategies. Microsurgery. 2000;20(8):420–429. doi: 10.1002/1098-2752(2000)20:8<420::aid-micr13>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivulich S., Westall G., Dooley M. The evolution of lung transplant immunosuppression. Drugs. 2018;78(10):965–982. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0930-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalt D.A. Tacrolimus: a review of laboratory detection methods and indications for use. Lab. Med. 2017;48(4):e62–e65. doi: 10.1093/labmed/lmx056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khush K.K., Valantine H.A. New developments in immunosuppressive therapy for heart transplantation. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs. 2009;14(1):1–21. doi: 10.1517/14728210902791605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langman L.J., Jannetto P.J. Individualizing immunosuppressive therapy for transplant patients. Clin. Chem. 2016;62(10):1302–1303. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2016.260380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R.A., Gabardi S. Current trends in immunosuppressive therapies for renal transplant recipients. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2012;69(22):1961–1975. doi: 10.2146/ajhp110624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Chen X., Hao L. Exploration of immune-related genes in high and low tumor mutation burden groups of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Biosci. Rep. 2020;40(7) doi: 10.1042/BSR20201491. BSR20201491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichvar A., Tremblay S., Naik D. Evaluation of clinical and safety outcomes following uncontrolled tacrolimus conversion in adult transplant recipients. Pharmacotherapy. 2019;39(5):564–575. doi: 10.1002/phar.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Ouyang S., Biao Y.u. PharmMapper Server: a web server for potential drug target identification via pharmacophore mapping approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W609–W614. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Yan T., Li X. Daam1 activates RhoA to regulate Wnt5a–induced glioblastoma cell invasion. Oncol. Rep. 2018;39(2):465–472. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.6124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDiarmid S.V. The use of tacrolimus in pediatric liver transplantation. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1998;26(1):90–102. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199801000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei J., Huang Y., Hao L. DAAM1-mediated migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells are suppressed by miR-208a-5p. Pathol Res Pract. 2019;215(7) doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2019.152452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei J., Xu B., Hao L. Overexpressed DAAM1 correlates with metastasis and predicts poor prognosis in breast cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2020;216(3) doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2019.152736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mika A., Stepnowski P. Current methods of the analysis of immunosuppressive agents in clinical materials: a review. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016;5(127):207–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus O., Kieseier B.C., Hartung H.P. Immunosuppressive agents in multiple sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4(4):654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen C., Shapiro R. New immunosuppressive agents in pediatric transplantation. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2014;69(Suppl 1):8–16. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2014(Sup01)03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormerod A.D. Topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus and the risk of cancer: how much cause for concern? Br. J. Dermatol. 2005;153(4):701–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington C.A., Park J.M. Sublingual tacrolimus as an alternative to oral administration for solid organ transplant recipients. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2015;72(4):277–284. doi: 10.2146/ajhp140322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posadas Salas M.A., Srinivas T.R. Update on the clinical utility of once-daily tacrolimus in the management of transplantation. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2014;1(8):1183–1194. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S55458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rallis E., Korfitis C., Gregoriou S. Assigning new roles to topical tacrolimus. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2007;16(8):1267–1276. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.8.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reske A., Reske A., Metze M. Complications of immunosuppressive agents therapy in transplant patients. Minerva Anestesiol. 2015;81(11):1244–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie M.E., Phipson B., Wu D., Hu Y., Law C.W., Shi W., Smyth G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7) doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte-Nutgen K., Tholking G., Suwelack B. Tacrolimus - pharmacokinetic considerations for clinicians. Curr. Drug Metab. 2018;19(4):342–350. doi: 10.2174/1389200219666180101104159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J.L., Li M., Yan L.N. Higher tacrolimus blood concentration is related to increased risk of post-transplantation diabetes mellitus after living donor liver transplantation. Int. J. Surg. 2018;51:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staatz C.E., Taylor P.J., Lynch S.V. A pharmacodynamic investigation of tacrolimus in pediatric liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2004;10(4):506–512. doi: 10.1002/lt.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh S.W., Lee K.W., Jeong J. Risk factors for the adverse events after conversion from twice-daily to once-daily tacrolimus in stable liver transplantation patients. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2016;31(11):1711–1716. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorwerk L., Slagter M., Horlings H.M. Immune induction strategies in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer to enhance the sensitivity to PD-1 blockade: the TONIC trial. Nat. Med. 2019;25(6):920–928. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin J.E., Bergstrand M., Wilczek H.E. Population pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in pediatric liver transplantation: early posttransplantation clearance. Ther. Drug Monit. 2011;33(6):663–672. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31823415cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Pan C., Gong J. Enhancing the enrichment of pharmacophore-based target prediction for the polypharmacological profiles of drugs. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016;56:1175–1183. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Shen Y., Wang S. PharmMapper 2017 update: a web server for potential drug target identification with a comprehensive target pharmacophore database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W356–W360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A., Xu Y., Fei Y. The role of immunosuppressive agents in the management of severe and refractory immune-related adverse events. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;16(4):201–210. doi: 10.1111/ajco.13332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woillard J.B., Debord J., Monchaud C. Population pharmacokinetics and bayesian estimators for refined dose adjustment of a new tacrolimus formulation in kidney and liver transplant patients. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017;56(12):1491–1498. doi: 10.1007/s40262-017-0533-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H.G. Personalized immunosuppressive therapy in pediatric heart transplantation: progress, pitfalls and promises. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010;126(2):146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong H., Yan T., Zhang W. miR-613 inhibits cell migration and invasion by downregulating Daam1 in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell. Signal. 2018;44:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H., Huang Y., Chen L. Exploration and validation of the effects of robust co-expressed immune-related genes on immune infiltration patterns and prognosis in laryngeal cancer. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020;85 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Lin G., Tan L. Current progress of tacrolimus dosing in solid organ transplant recipients: Pharmacogenetic considerations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;102:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.