Abstract

Background

Persons living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with resistance to antiretroviral therapy are vulnerable to adverse HIV-related health outcomes and can contribute to transmission of HIV drug resistance (HIVDR) when nonvirally suppressed. The degree to which HIVDR contributes to disease burden in Florida—the US state with the highest HIV incidence– is unknown.

Methods

We explored sociodemographic, ecological, and spatiotemporal associations of HIVDR. HIV-1 sequences (n = 34 447) collected during 2012–2017 were obtained from the Florida Department of Health. HIVDR was categorized by resistance class, including resistance to nucleoside reverse-transcriptase , nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase , protease , and integrase inhibitors. Multidrug resistance and transmitted drug resistance were also evaluated. Multivariable fixed-effects logistic regression models were fitted to associate individual- and county-level sociodemographic and ecological health indicators with HIVDR.

Results

The HIVDR prevalence was 19.2% (nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor resistance), 29.7% (nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor resistance), 6.6% (protease inhibitor resistance), 23.5% (transmitted drug resistance), 13.2% (multidrug resistance), and 8.2% (integrase strand transfer inhibitor resistance), with significant variation by Florida county. Individuals who were older, black, or acquired HIV through mother-to-child transmission had significantly higher odds of HIVDR. HIVDR was linked to counties with lower socioeconomic status, higher rates of unemployment, and poor mental health.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that HIVDR prevalence is higher in Florida than aggregate North American estimates with significant geographic and socioecological heterogeneity.

Keywords: HIV drug resistance, Antiretroviral therapy, HIV in the South

This study of 34 447 human immunodeficiency virus 1 sequences collected in Florida showed high prevalence of drug resistance with significant sociodemographic and geospatial heterogeneity. Resistance was linked to counties with lower socioeconomic status, higher unemployment, and poor mental health.

Despite the success of combined antiretroviral therapy (ART) in reducing both disease and deaths attributed to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, prevalence of HIV drug resistance (HIVDR) remains a global concern [1]. HIVDR can be transmitted or acquired and is characterized by mutations in the genetic structure of the virus, allowing it to escape the antiviral activity of ART [2]. The likelihood of HIVDR transmission relies on the prevalence of resistance mutations among persons living with HIV (PWH) engaged in high-risk behaviors in the population [3]. This population is vulnerable to adverse health outcomes, because persons who harbor drug-resistant infections are more likely to experience suboptimal viral suppression [2, 4, 5], accumulate additional resistance mutations [2, 6], discontinue ART [2], and die prematurely [2, 7]. Moreover, from a public health perspective, HIVDR presents substantial programmatic burden, and will contribute to roughly 9% of new infections by 2030 if current trends persist [7]. HIVDR surveillance, prevention, and response are therefore critical for achieving elimination of HIV as a public health threat by 2030 [2, 8].

In the United States, aggregate estimates of HIVDR prevalence seem stable over time when compared to other regions [3, 9]; however, HIV epidemic dynamics differ dramatically across regions within the United States [10]. Overall estimates for North America (NA) suggest that the prevalence of HIVDR among PWH with molecular sequences is 7.2% for resistance to protease inhibitors (PIs), 15.7% for nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), 23.4% for nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), 11.5% for 2-class resistance (or “multidrug” resistance [MDR]), and 13.0% for transmitted drug resistance (TDR) for the period 2007–2016 [9]. HIVDR prevalence at the regional level is not well understood, however. The US epidemic epicenter is concentrated in the South, which contributed more than half of all new HIV diagnoses in 2017 [11]. That same year, the Southern state Florida had the most new HIV diagnoses in the country [12], and the proportion of PWH who were virally suppressed (<200 copies/mL) was only 62% [13]. The extent to which HIVDR contributes to the burden of HIV in Florida, a contributor to poor treatment outcomes, is not understood.

In 2019, 7 largely urban Florida counties (Broward, Duval, Hillsborough, Miami-Dade, Orange, Palm Beach, and Pinellas), which include the major cities Jacksonville, Orlando, Tampa, and Miami, were identified as target regions for the Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America (EHE) initiative [14]. One of the key strategies of EHE is to rapidly respond to potential outbreaks using cluster detection techniques (eg, molecular surveillance), made possible through drug resistance testing [15]. Over the past decade the Florida Department of Health (FDOH) has been collecting viral isolate sequences on individuals with a recent HIV diagnosis. Collection of these sequences started as part of the Variant, Atypical and Resistant HIV Surveillance program, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is designed to monitor HIVDR starting in 2007 in Florida. About 60 000 HIV sequences have been collected by the FDOH since 2007.

To examine the burden of HIVDR among PWH in Florida, this study aimed to estimate the prevalence, investigate the sociodemographic and socioecological determinants, and describe the spatiotemporal characteristics of HIVDR in Florida during 2012–2017. This study capitalizes on the extensive HIV molecular sequence database maintained by the FDOH and involves analysis of the largest collection of sequence data in Florida to date.

METHODS

Ethics Approval

This analysis and a waiver of informed consent were approved as exempt by the institutional review boards at the University of Florida (IRB201703199) and the FDOH.

Sequences

HIV nucleotide sequences were obtained from the FDOH’s enhanced HIV/AIDS reporting system (eHARs), collected as part of routine HIV surveillance in Florida, per Florida Administrative Code 64D-3.029. We selected HIV sequences of any subtype with a known sample year (2007–2017), encompassing the whole protease region (1–99 amino acids), at least the first 250 amino acids of the reverse-transcriptase and/or ≥288 of the integrase region, using recommended consensus B and HXB2 nucleotide numbering as references [16]. Analyses were restricted to sequences collected during 2012–2017, because sequences received by eHARs increased dramatically during this period when the Variant, Atypical and Resistant program HIV Surveillance expanded reporting to all laboratories in the state. Only one sequence per person per year was retained, with no restriction on time from diagnosis, choosing the earliest sequence when there were multiple entries per year.

Drug Resistance

Drug resistance mutations were categorized according to their effect on ART drug classes: NNRTIs, NRTIs, PIs, and integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs). All eligible sequences were aligned to consensus B and HXB2 reference sequences, checking similarity and alignment quality, and then mutations were extracted from the reference in the protease, reverse-transcriptase, and integrase regions through a local in-house program that uses a Smith-Waterman aligner (with modifications to the indel coding according to Stanford University’s HIVdb v.8.6.1 convention [17]). Mutation figures were passed on to another in-house program that calculated resistance to NRTIs, NNRTIs, PIs, and INSTIs, using Stanford’s HIVdb mutation scoring algorithm.

We had previously verified the consistency between our in-house program and the Stanford’s HIVdb Web service. Resistance to a drug class (NRTI, NNRTI, PI, or INSTI) was defined as standardized intermediate or resistant scoring for ≥1 drug belonging to that class. MDR was calculated as the presence of intermediate/resistant scoring for ≥2 drug classes (NRTI, NNRTI, or PI). We did not include integrase in the calculation of MDR, because most of the population lacked sequencing coverage of this region. TDR was estimated separately using the World Health Organization 2009 list of surveillance drug resistance mutations [18]. Subtyping was performed using the Context-based Modeling for Expeditious Typing alignment-free subtyping tool, which is comparable in performance to phylogeny-based methods [19]. Unassigned sequences were resolved with BLAST (the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool), using the recombinant form reference set available from Los Alamos we described previously [9]. The reference set for subtyping was redundant with about 3 representatives per subtype or circulating recombinant form to increase robustness.

Covariates

Demographic information was accessed via eHARS and included age category (≤25, 26–33, 34–45, or ≥46 years), sex at birth (male or female), race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic/Latino, or other [American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or multirace]), transmission category (heterosexual contact, injection drug use [IDU], male-to-male sexual contact, mother-to-child transmission [MCT], or unknown), country of birth (categorized as world region of birth: NA, Africa, Asia Pacific, Caribbean, Europe, or Latin America), test year, treatment status (ie, prior exposure to NRTIs, NNRTIs, PIs, entry or fusion inhibitors, and INSTIs), and any evidence of viral suppression. County-level socioecological indicators were retrieved via the publicly accessible data sets available on the County Health Rankings Web site (http://www.countyhealthrankings.org) [20], which reports rankings and statistics for >50 health indicators calculated for every county [21]. Higher rankings (eg, socioeconomic factors rank) correspond to worse health. In this analysis, we considered indicators reported without interruption in all 67 Florida counties from 2012 to 2017. The complete list of indicators considered in this analysis can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Statistical Analysis

Prevalence was calculated for resistance to NNRTIs, NRTIs, PIs, and INSTIs as well as MDR for the ART-experienced population. TDR prevalence was calculated for presumed ART-naive individuals who lacked an ART initiation date at the time of sample collection. Overall prevalence was calculated for each resistance outcome as the proportion of resistant sequences of all sequences genotyped over the study period. Annual prevalence was calculated as the proportion of sequences containing drug resistance mutations of all sequences tested per year, with only 1 sequence permitted per person. Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing interpolation and data bootstrapping were performed to account for uncertainty in prevalence estimates. For simplicity of data presentation, demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population were compared across 2 periods of genotype testing: 2012–2014 and 2015–2017. Prevalence quintiles were mapped for each county reporting ≥ 10 sequences over the study period. Counties with prevalence estimates above or below 2 standard deviations of the state prevalence were considered to have a significantly high or low prevalence of HIVDR, respectively.

Socioecological variables were evaluated for associations with HIVDR in univariable and multivariable models. Relative risks for the univariable associations between HIVDR prevalence and county-level socioecological health indicators were estimated using a Bayesian conditional autoregressive model. Generalized linear mixed effects models were fitted to account for both individual- and county-level variations simultaneously in the estimation of county-level coefficients. Univariable and multivariable (bidirectional stepwise-selected) fixed-effects logistic regression models were fitted to associate individual (sociodemographic and clinical) characteristics and county-level socioecological health indicators with HIVDR.

Correlations between socioecological variables were computed and assessed before multivariable model fitting. Highly correlated variables (Pearson correlation coefficient ≥|0.5|) were identified, and only the variables with the strongest association to MDR in the univariable mixed-effects regression models were retained. Bonferroni correction to control the false discovery rate was applied to P values obtained by means of univariate analysis. All analyses were performed using R software, version 3.5.1 [22]. The ggplot2 and maptools packages were used to generate geographic maps by county and a relative risk heat map of socioecological associations [23, 24].

RESULTS

HIVDR Prevalence

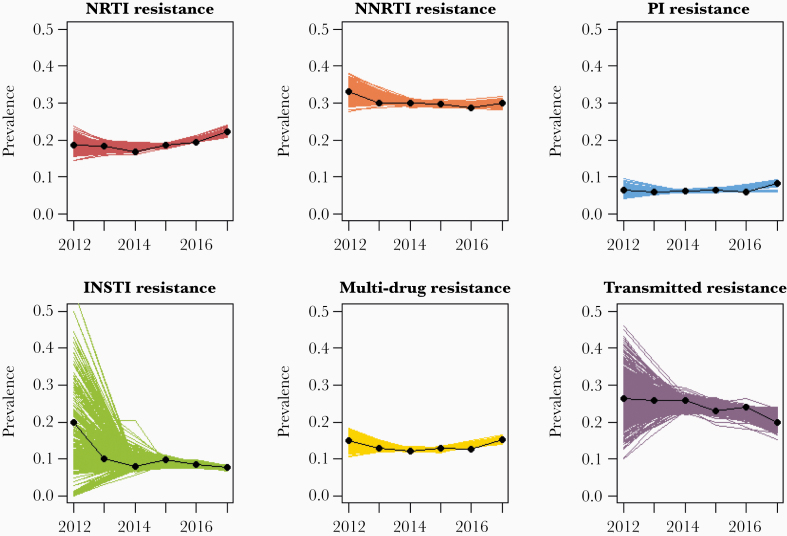

A total of 34 447 sequences (n = 28 923 unique PWH with an average of 1.2 sequences per person) met criteria for analysis of resistance to NRTI, NNRTI, and PI drug classes, in addition to MDR and TDR outcomes. Additionally, 11 107 sequences (n = 10 290 unique PWH with an average of 1.1 sequences per person) were available to evaluate resistance to INSTIs. HIVDR prevalence over the study period was 29.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 29.2%–30.2%) for NNRTI, 19.2% (18.8%–19.6%) for NRTI, 23.5% (22.1%–24.9%) for TDR, 13.2% (12.8%–13.6 for MDR, 8.2% (7.7%–8.7%) for INSTI, and 6.6% (6.3%–6.9%) for PI (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Annual prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus drug resistance outcomes in Florida by test year, between 2012 and 2017. Estimates indicate annual prevalence per-year. Line estimates are drawn via locally weighted scatterplot smoothing interpolation and data bootstrapping (500 times). Abbreviations: INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

Characteristics of Study Population

Overall, the population was majority male, aged ≥34 years, and born in NA (Table 1). The proportion male increased from 68.4% (95% CI, 67.5%–69.2%) in 2012–2014 to 70.8% (70.3%–71.4%) in 2015–2017. The most frequent race/ethnicity was black for both periods; however, the proportion of Hispanic/Latino individuals increased from 19.0% (95% CI, 18.3%–19.7%) in earlier years to 21.4% (20.8%–21.9%) in later years. Likewise, the proportion of Latin American–born individuals increased from 3.9% (95% CI, 3.5%–4.3%) in earlier years to 5.4% (5.1%–5.7%) in later years. Male-to-male sexual contact was the most frequent transmission category, increasing from 43.0% (95% CI, 42.0%–43.9%) in earlier years to 47.4% (46.7%–48.0%) more recently. B was the predominant subtype in this population; however, we observed a modest increase in the proportion of other recombinant subtypes (from 0.8% [95% CI , .6%–.9%] in 2012–2014 to 1.2% [1.0%–1.3%] in 2015–2017). Subtype classification with the Rega tool yielded >96% concordance overall, and 99% with the subtype B set.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Population in Florida, 2012–2017

| Genotype Test Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012–2014 | 2015–2017 | |||

| Characteristic | No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) |

| Age group, y | ||||

| 0–25 | 1207 | 10.9 (10.3–11.4) | 2506 | 10.7 (10.3–11.1) |

| 26–33 | 1970 | 17.7 (17.0–18.4) | 4373 | 18.7 (18.2–19.2) |

| 34–45 | 3209 | 28.9 (28.0–29.7) | 6099 | 26.1 (25.6–26.7) |

| ≥46 | 4729 | 42.5 (41.6–43.5) | 10 354 | 44.4 (43.7–45.0) |

| Sex at birth | ||||

| Male | 7599 | 68.4 (67.5–69.2) | 16 530 | 70.8 (70.3–71.4) |

| Female | 3516 | 31.6 (30.8–32.5) | 6802 | 29.2 (28.6–29.7) |

| Region of birth | ||||

| Africa | 33 | 0.3 (.2–.4) | 97 | 0.4 (.3–.5) |

| Asia Pacific | 55 | 0.5 (.4–.6) | 117 | 0.5 (.4–.6) |

| Caribbean | 1589 | 14.3 (13.6–14.9) | 3509 | 15.0 (14.6–15.5) |

| Europe | 40 | 0.4 (.2–.5) | 159 | 0.7 (.6–.8) |

| Latin America | 433 | 3.9 (3.5–4.3) | 1261 | 5.4 (5.1–5.7) |

| North America | 8516 | 76.6 (75.8–77.4) | 17 131 | 73.4 (72.9–74.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black | 6264 | 56.4 (55.4–57.3) | 12 638 | 54.2 (53.5–54.8) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 2111 | 19.0 (18.3–19.7) | 4982 | 21.4 (20.8–21.9) |

| Othera | 266 | 2.4 (2.1–2.7) | 507 | 2.2 (2.0–2.4) |

| White | 2474 | 22.3 (21.5–23.0) | 5205 | 22.3 (21.8–22.8) |

| Transmission category | ||||

| Heterosexual contact | 4147 | 37.3 (36.4–38.2) | 8333 | 35.7 (35.1–36.3) |

| IDU | 1527 | 13.7 (13.1–14.4) | 2577 | 11.0 (10.6–11.4) |

| MTM | 4776 | 43.0 (42.0–43.9) | 11 050 | 47.4 (46.7–48.0) |

| MCT | 244 | 2.2 (1.9–2.5) | 550 | 2.4 (2.2–2.6) |

| Unknown | 421 | 3.8 (3.4–4.1) | 822 | 3.5 (3.3–3.8) |

| HIV-1 subtype | ||||

| B | 10 822 | 97.4 (97.1–97.7) | 22 542 | 96.6 (96.4–96.8) |

| B recombinant | 130 | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 368 | 1.6 (1.4–1.7) |

| Non-B | 79 | 0.7 (.6–.9) | 148 | 0.6 (.5–.7) |

| Other recombinant | 84 | 0.8 (.6–.9) | 274 | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IDU, injection drug use; MCT, mother-to-child transmission MTM, male-to-male sexual contact.

a“Other” race/ethnicity included American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and multirace.

Geographic Associations

Spatial distributions of HIVDR prevalence are mapped by county in Figure 2. Counties with <10 sequences were excluded from the analysis. Prevalence of HIVDR varied significantly by county, with few discernable geographic trends. Counties with high HIVDR prevalence were often rural, including Glades, Washington, and Hardee counties. Interestingly, prevalence of HIVDR was not significantly higher or lower in any of the 7 Florida counties included in EHE, where the major cities Miami, Orlando, Jacksonville, and Tampa are located.

Figure 2.

Maps of human immunodeficiency virus drug resistance prevalence by Florida county, between 2012 and 2017. Darker regions correspond to higher prevalence of resistance. Counties with <10 sequences were excluded from analysis. Drug resistance outcomes included nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), protease inhibitor (PI), and integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) resistance, multidrug resistance (MDR), and transmitted drug resistance (TDR).

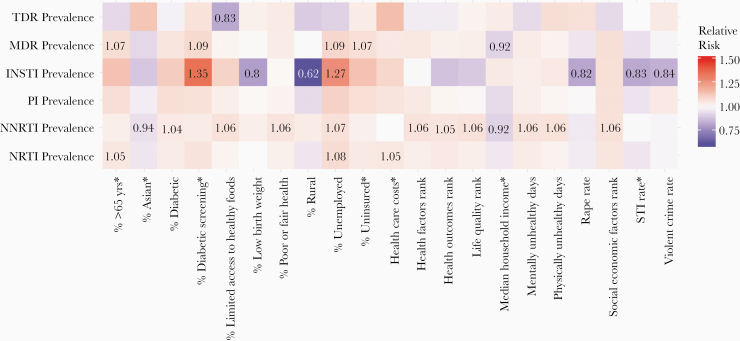

Associations Between HIVDR and County-Level Socioecological Health Indicators

A relative risk heat map demonstrating univariate associations between HIVDR prevalence and county-level socioecological health indicators is presented in Figure 3. Notably, higher rates of resistance were consistently associated with higher percent unemployed. We also noted associations between NNRTI resistance and county-level rankings. County rankings for health factors, health outcomes, life quality, and socioeconomic factors were all associated with higher NNRTI resistance, as well as the percentages in poor or fair health, with limited access to healthy foods, unemployed, or diabetic, and physically and the number of physically and mentally unhealthy days. Furthermore, median household income was inversely associated with MDR and NNRTI resistance.

Figure 3.

Relative risk heat map showing univariable associations between drug resistance prevalence and county-level socioecological health indicators, from County Health Rankings [20]. Relative risk estimates significant at the 5% level are shown. Asterisks indicate log-transformed variables. Note that none of the factors was significantly associated with protease inhibitor (PI) resistance. Abbreviations: INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor (resistance); MDR, multidrug resistance; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor (resistance); NRTI, nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor (resistance); STI, sexually transmitted infection. TDR, transmitted drug resistance.

Multivariable Associations of Individual Characteristics and Socioecological Factors With HIVDR

Multivariable analyses revealed associations between HIVDR and individual sociodemographic characteristics, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and region of birth. Older individuals (aged ≥46 years), had significantly higher resistance than individuals aged ≤25 years in all models except for TDR (Table 2). In ART-naive individuals, we observed decreased odds of TDR for those aged 26–33 years (versus ≤25 years) (odds ratio [OR], 0.73; 95% CI, .55–.97). Modest sex differences were also observed in this population in relation to MDR and NRTI resistance, with male individuals experiencing slightly higher odds. Compared with black individuals, white individuals tended to have lower odds of HIVDR—particularly for NRTI, NNRTI, INSTI, and MDR—but higher odds of PI resistance (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.16–1.48). Hispanic and Latino individuals had higher odds of PI resistance (vs black individuals) (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.06–1.37). Associations between region of birth and HIVDR were significant for NNRTIs only among those born in the Caribbean (vs NA), in whom we observed decreased odds (OR, 0.86; 95% CI, .79–.93).

Table 2.

Fixed Effects Multivariable Model Associations of Individual (Sociodemographic and Clinical) Characteristics and Socioecological Factors With Resistance Outcomes in Florida, 2012–2017a

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any History of ART (n = 30 788) | ART Naive (n = 3659) | |||||

| Characteristic | NRTI Resistance (n = 6204) | NNRTI Resistance (n = 9333) | PI Resistance (n = 2110) | INSTI Resistance (n = 954) | MDR (n = 4265) | TDR (n = 859/3659) |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 26–33 vs 0–25 | 1.02 (.87–1.19) | 1.02 (.91–1.14) | 0.87 (.70–1.10) | 1.43 (.95–2.19) | 1.04 (.85–1.26) | 0.73 (.55–.97) |

| 34–45 vs 0–25 | 1.62 (1.39–1.89) | 1.21 (1.08–1.36) | 1.15 (.91–1.44) | 1.97 (1.32–3.04) | 1.86 (1.54–2.27) | 0.96 (.72–1.27) |

| ≥46 vs 0–25 | 2.27 (1.96–2.63) | 1.37 (1.23–1.52) | 2.10 (1.70–2.62) | 2.44 (1.65–3.72) | 2.82 (2.35–3.41) | 1.18 (.90–1.55) |

| Sex at birth: male vs female | 1.22 (1.12–1.32) | … | … | … | 1.19 (1.08–1.30) | … |

| Region of birth | ||||||

| Africa vs NA | … | 0.90 (.54–1.45) | … | … | … | … |

| Asia Pacific vs NA | … | 1.20 (.79–1.81) | … | … | … | … |

| Caribbean vs NA | … | 0.86 (.79–.93) | … | … | … | … |

| Europe vs NA | … | 1.02 (.70–1.46) | … | … | … | … |

| Latin America vs NA | … | 0.90 (.78–1.04) | … | … | … | … |

| Race/ethnicityb | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino vs black | 0.98 (.90–1.07) | 0.99 (.91–1.07) | 1.20 (1.06–1.37) | 1.10 (.92–1.32) | 1.03 (.93–1.13) | … |

| Other vs black | 0.79 (.64–.98) | 0.81 (.67–.97) | 1.03 (.73–1.41) | 0.92 (.55–1.46) | 0.84 (.66–1.07) | … |

| White vs black | 0.89 (.82–.96) | 0.87 (.82–.94) | 1.31 (1.16–1.48) | 0.78 (.64–.95) | 0.91 (.82–1.00) | … |

| Transmission category (vs heterosexual contact) | ||||||

| IDU | 0.81 (.74–.90) | 0.97 (.89–1.05) | 0.97 (.83–1.14) | 0.72 (.56–.92) | 0.78 (.70–.88) | 1.08 (.82–1.41) |

| MTM | 1.01 (.92–1.10) | 0.96 (.90–1.02) | 1.24 (1.10–1.39) | 1.12 (.95–1.32) | 1.01 (.91–1.12) | 1.11 (.93–1.34) |

| MCT | 4.87 (4.03–5.90) | 1.78 (1.50–2.11) | 5.79 (4.46–7.51) | 1.58 (.95–2.55) | 5.47 (4.40–6.80) | 3.09 (1.66–5.83) |

| Unknown | 1.15 (.97–1.35) | 1.01 (.88–1.16) | 1.71 (1.36–2.14) | 0.85 (.55–1.27) | 1.32 (1.10–1.58) | 0.50 (.24–.92) |

| Subtype (vs B) | ||||||

| B recombinant | … | 0.70 (.53–.91) | 1.43 (.92–2.13) | 1.14 (.95–1.37) | … | 0.60 (.30–1.07) |

| Non-B | … | 0.79 (.54–1.14) | 0.32 (.10–.76) | 2.56 (.94–5.93) | … | 0.16 (.01–.78) |

| Other | … | 0.57 (.40–.79) | 0.59 (.27–1.13) | 0.49 (.12–1.33) | … | 0.48 (.18–1.05) |

| Ever suppressed: no vs yes | 0.65 (.61–.70) | 0.67 (.63–.71) | 0.81 (.73–.91) | 0.63 (.58–.69) | … | |

| Test year | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) | 0.95 (.93–.98) | 1.15 (1.07–1.24) | 1.18 (1.01–1.39) | … | 0.77 (.61–.97) |

| Time from diagnosis ≥12 vs ≤12 mo) | 3.56 (3.17–4.01) | 1.67 (1.54–1.81) | 1.92 (1.63–2.26) | 4.25 (3.18–5.79) | 4.31 (3.70–5.05) | 2.26 (1.91–2.69) |

| Socioeconomic factors rank | 1.08 (1.03–1.14) | 1.07 (1.03–1.12) | … | … | … | 1.33 (1.04–1.69) |

| Physical environment rank | … | 1.03 (1.00–1.07) | … | 1.12 (1.02–1.24) | … | … |

| Number of mentally unhealthy days | 1.10 (1.05–1.16) | 1.08 (1.03–1.13) | … | 0.83 (.70–.98) | 1.11 (1.05–1.18) | … |

| Proportion (%) with variable | ||||||

| Low birth weight | … | … | 1.11 (1.01–1.22) | 0.88 (.74–1.04) | 1.07 (.99–1.15) | … |

| Diabetic screening | … | … | … | … | … | 1.18 (.96–1.46) |

| Unemployed | … | … | 1.22 (1.07–1.40) | 1.63 (1.25–2.12) | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) | 0.69 (.45–1.07) |

| Aged >65 y | … | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) | 1.07 (1.00–1.15) | … | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) | … |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | … | … | … | … | … | 1.25 (.94–1.64) |

| Rural | 0.83 (.77–.91) | … | … | 0.71 (.51–.94) | 0.88 (.80–.96) | 0.73 (.55–.98) |

| Diabetic | … | 0.96 (.93–.99) | 0.93 (.88–.98) | … | … | … |

| Uninsured adult | … | … | … | … | … | 0.89 (.80–1.00) |

| Violent crime rate | … | … | … | 0.80 (.70–.92) | … | … |

| Murder rate | 0.96 (.92–1.00) | … | … | 0.90 (.86–.94) | … | |

| Rape rate | 0.97 (.92–1.01) | 0.95 (.92–.99) | … | … | … | … |

| Robbery rate | 1.04 (.99–1.09) | 1.05 (1.01–1.10) | … | … | 1.05 (1.00–1.11) | … |

Blank cells indicate variables eliminated during the model selection procedure.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; IDU, injection drug use; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; MCT, mother-to-child transmission; MDR, multidrug resistance; MTM, male-to-male sexual contact; NA, North America; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; TDR, transmitted drug resistance.

aAll associations are adjusted for individual demographic and clinical characteristics and county-level sociodemographic factors.

b“Other” race/ethnicity included American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and multirace.

Differences in the odds of HIVDR by HIV transmission category were also observed. Persons with IDU had lower odds of HIVDR—particularly for NRTI, INSTI, and MDR compared with heterosexual transmission risk. Individuals with MCT had significantly increased odds for several resistance outcomes, including resistance to NRTIs (OR, 4.87; 95% CI, 4.03–5.90), NNRTIs (1.78; 1.50–2.11), PIs (5.79; 4.46–7.51), MDR (5.47; 4.40–6.80), and TDR (3.09; 1.66–5.83). Individuals with male-to-male sexual contact had higher odds of PI resistance (OR, 1.24; 95% CI,1.10–1.39).

HIV-1 subtype, genotype test year, and timing between diagnosis and genotype test were also associated with HIVDR. Compared with B subtypes, non-B subtypes were associated with lower odds of PI resistance (OR, 0.32; 95% CI, .10–.76) and B-recombinant and other-recombinant subtypes were associated with lower odds of NNRTI resistance (OR, 0.70 [95% CI, .53–.91] for B-recombinants and 0.57 [.40–.79] for other recombinants). We observed decreasing odds of TDR and NNRTI resistance and increasing odds of PIs and INSTI resistance with each incremental year increase (OR, 1.15 [95% CI, 1.07–1.24] for PIs and 1.18 [1.01–1.39] for INSTIs) over the study period (2012–2017). Individuals who received genotype tests >12 months after diagnosis had significantly greater odds of all HIVDR outcomes, compared with those who received the test within a year of diagnosis.

There were several associations between HIVDR and county-level socioecological factors (Table 2). Higher HIVDR rates were associated with higher socioeconomic factors rank (ie, lower socioeconomic status), higher percentage unemployed, more mentally unhealthy days, and higher percentage elderly (Table 2). Alternatively, lower rates of HIVDR were associated with higher crime rates and lower percentage rural population. Univariate model associations of sociodemographic, clinical, and socioecological factors with resistance outcomes are presented in Supplementary Tables 1–3.

DISCUSSION

This study analyzed the prevalence, sociodemographic, ecological, and spatiotemporal determinants of HIVDR among PWH in Florida during 2012–2017. The results indicate HIVDR prevalence is higher in Florida compared with current NA estimates [9] and may be increasing for PI and INSTI resistance. Compared with previously published estimates for NA from 2007 to 2016, HIVDR prevalence was higher in Florida for NRTI (15.7% vs 19.2%), NNRTI (23.4% vs 29.7%), and MDR (11.5% vs 13.2%) resistance [9]. Estimates were comparable for PI resistance (7.2% vs 6.6%); however, we observed a positive association between increasing genotype year and prevalence of PI resistance. We likewise observed a positive association between increasing genotype year and prevalence of resistance to newer INSTI therapies over the study period, although this result may be linked to the increased frequency of integrase testing in more recent years.

Multivariable analyses revealed that HIVDR was higher among PWH aged ≥ 46 years (vs ≤25 years), individuals who acquired HIV through MCT (vs heterosexual contact), black (vs white) individuals, and male (vs female) individuals. These findings are similar to those from a previous study reporting comparable racial and sex differences with the odds nonviral suppression in Florida [25]. Owing to exposure to ART in utero or through breast milk after birth, individuals who acquire HIV through MCT often have high rates of pretreatment drug resistance [26], which may explain why this transmission group had the highest odds of all HIVDR outcomes studied. In contrast, individuals who acquired HIV through IDU had lower odds of HIVDR in the current study. This funding was initially puzzling because rates of homelessness and unemployment (linked to decreased care linkage or retention), are high among people who inject drugs [27]; however, another study found a lower incidence of drug resistance mutations among people who inject as a result of the test-and-treat initiative [28]. Further analysis of this finding is warranted.

Geographic analyses revealed considerable heterogeneity in HIVDR prevalence by Florida county. Interestingly, high prevalence of resistance was not detected in counties with the highest proportion of PWH or resistance testing. The 7 Florida counties listed in the EHE, which together represent 73% of total PWH in the state, did not have significantly higher rates of HIVDR in the current study. The EHE targets largely urban Florida counties with fewer barriers to care, such as lack of specialty healthcare providers [29]. Given that HIVDR contributes to poorer overall treatment outcomes, continued monitoring of HIVDR in rural regions is needed. Analysis of HIV-1 subtypes in Florida revealed that most sequences were covered by the B subtype, which is typical in the United States, but the increasing presence of recombinants warrants further investigation of the contribution of imported HIV transmissions in Florida.

The increased burden of HIVDR in Florida observed in this study may reflect the overall US HIV epidemic. Florida, like other Southern states, has a disproportionately high burden of HIV infection compared with other regions. Nearly half of all HIV diagnoses in the United States occur in the South, even though this region accounts for only one-third of the US population [30]. Factors thought to be driving the HIV epidemic in the South include poverty, income inequality, cultural issues (eg, homophobia, transphobia, and racism), and higher rates of comorbid conditions (eg, obesity, diabetes, and cancer) [30]. Although this analysis could not account for factors such as socioeconomic status or comorbid conditions at the individual level, we did assess some of these factors at the county level and found that HIVDR was significantly associated with socioeconomic status, income level, unemployment, and mental health. This suggests that there are socioeconomic and mental health factors contributing to acquired HIVDR, and future studies should investigate this relationship further at the individual level.

The current analysis had many strengths. To our knowledge, it was the largest and most comprehensive study of transmitted and acquired HIVDR in a state to date. Previous smaller-scale studies have reported the prevalence and correlates of TDR in other US regions [31–33]; however, fewer studies exist to describe trends in acquired HIVDR at the state level, and no studies have assessed associations with spatiotemporal or socioecological factors. Our multivariable models combined individual-level sociodemographic and clinical factors with county-level health indicators to account for socioecological factors contributing to HIVDR patterns. The study provides important epidemiological information on the geographic regions and subpopulations with the greatest burden of HIVDR in a region with disproportionately high incidence of HIV. Moreover, these results justify the need for clinicians to order genotype tests to ensure ART regimen compatibility and for continued molecular surveillance to inform precision public health interventions in Florida.

This analysis also had limitations. Importantly, we lacked data on prescription ART, which prevented the ability to consider the impact of prescribing practices on HIVDR patterns. This may explain the significant annual increase in resistance to the newest group of therapies (INSTI) observed in this study, because we were unable to account for expected increased rates of INSTI prescriptions in more recent years. Another limitation of our analysis was the method of MDR determination. Although we did not assess specific mutations, presumably, the majority of NRTI resistance was M184V, and the majority of NNRTI resistance was K103N and related efavirenz (EFV) resistance mutations. Because many people with resistance to EFV also have resistance to M184V (owing to the use of combination drugs like Truvada), this explains the similarly high prevalence of resistance to these 2 classes and the apparent high prevalence of MDR. Thus, MDR estimates may be artificially inflated owing to resistance to EFV plus lamivudine or emtricitabine. Because cross-resistance to specific drugs within ART classes can be common and pooled estimates contain less measurement error than resistance to single drugs, we preferred to perform the analysis by ART class.

Future studies should examine single drugs as well as commonly prescribed combination drugs in drug resistance analyses. In addition, although coverage of genotype testing was near or above 50% throughout the study period according to the FDOH, selection bias likely occurred, because our study population only included diagnosed PWH who received a genotype test, representing less than half of PWH in the state.

These findings do not necessarily represent the burden of resistance among nonvirally suppressed PWH in Florida. Another potential limitation is that our modeling approach did not account for individuals contributing >1 sequence; however, the impact of this was likely inconsequential, given that the mean number of sequences available per person was 1.2. Furthermore, results of the socioecological analysis of health indices at the county level should not be interpreted at the individual level. This approach was selected to improve model fitness and provide a source of socioeconomic data that would have otherwise been omitted. Deeper analysis of the individual-level sociodemographic or behavioral factors contributing to HIVDR patterns in the community (eg, medication adherence) is needed.

In conclusion, this was the most comprehensive analysis of HIVDR in Florida to date. It covered all 67 Florida counties, encompassed several consecutive years of genotype sampling, and analyzed associations with numerous epidemiological, spatiotemporal, and socioecological factors to provide a complete depiction of HIVDR in a region with a disproportionately high burden of HIV. Our findings indicate that the prevalence of HIVDR in Florida is higher than published NA estimates, with considerable heterogeneity by geographic region. These results warrant further surveillance of HIV molecular epidemiology in Florida in support of EHE.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. M. S. and M. P. conceived of the idea for the study, with input from S. N. R., K. P., and E. C. S.; K. P. and E. C. S. were responsible for data procurement; S. N. R. completed the data analysis, with assistance from H. H., R. L. C., and M. P.; and K. P., C. M., R. L. C., E. C. S., and M. P. assisted S. N. R. with data interpretation. All authors contributed to writing, and S. N. R. had full access to all of the data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Disclaimer. The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the official positions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the authors’ affiliated institutions. The funders had no role in the decision to submit for publication.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Florida Department of Health (grant CODNY-P-01), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant R21-AI138815-01), and the University of Florida’s “Creating the Healthiest Generation” Moonshot initiative, which is supported by the University of Florida Office of the Provost, Office of Research, College of Medicine, and Clinical and Translational Science Institute and University of Florida Health,.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Global action plan on HIV drug resistance 2017–2021. License CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. HIV drug resistance report 2017. License CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ross LL, Shortino D, Shaefer MS. Changes from 2000 to 2009 in the prevalence of HIV-1 containing drug resistance-associated mutations from antiretroviral therapy-naive, HIV-1-infected patients in the United States. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2018; 34:672–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hamers RL, Schuurman R, Sigaloff KC, et al. ; PharmAccess African Studies to Evaluate Resistance (PASER) Investigators . Effect of pretreatment HIV-1 drug resistance on immunological, virological, and drug-resistance outcomes of first-line antiretroviral treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:307–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kantor R, Smeaton L, Vardhanabhuti S, et al. ; AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) A5175 Study Team . Pretreatment HIV drug resistance and HIV-1 subtype C are independently associated with virologic failure: results from the multinational PEARLS (ACTG A5175) clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1541–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barth RE, Aitken SC, Tempelman H, et al. Accumulation of drug resistance and loss of therapeutic options precede commonly used criteria for treatment failure in HIV-1 subtype-C-infected patients. Antivir Ther 2012; 17:377–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Phillips AN, Stover J, Cambiano V, et al. Impact of HIV drug resistance on HIV/AIDS-associated mortality, new infections, and antiretroviral therapy program costs in sub-Saharan Africa. J Infect Dis 2017; 215:1362–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clutter DS, Jordan MR, Bertagnolio S, Shafer RW. HIV-1 drug resistance and resistance testing. Infect Genet Evol 2016; 46:292–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zazzi M, Hu H, Prosperi M. The global burden of HIV-1 drug resistance in the past 20 years. PeerJ 2018; 6:e4848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States and dependent areas. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/ataglance.html. Accessed 19 June 2019.

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States by geography. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/geographicdistribution.html. Accessed 16 October 2018.

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report. HIV/AIDS statistics overview. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/index.html. Accessed 20 June 2019.

- 13. Florida Department of Health. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Program guides public health services. HIV Data Center, 2018. http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/aids/surveillance/index.html. Accessed 12 June 2019.

- 14. US Department of Health and Human Services. Ending the HIV epidemic: counties, territories, and states. https://files.hiv.gov/s3fs-public/Ending-the-HIV-Epidemic-Counties-and-Territories.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2019.

- 15. US Department of Health and Human Services. What is “Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America?”https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview. Accessed 20 June 2019.

- 16. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Consensus and ancestral sequence alignments. HIV sequence database. https://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/HIV/CONSENSUS/Consensus.html. Accessed 20 June 2019.

- 17. Stanford University. HIV drug resistance database. https://hivdb.stanford.edu/. Accessed 20 June 2019.

- 18. Bennett DE, Camacho RJ, Otelea D, et al. Drug resistance mutations for surveillance of transmitted HIV-1 drug-resistance: 2009 update. PLoS One 2009; 4:e4724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Struck D, Lawyer G, Ternes AM, Schmit JC, Bercoff DP. COMET: adaptive context-based modeling for ultrafast HIV-1 subtype identification. Nucleic Acids Res 2014; 42:e144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. 2018. www.countyhealthrankings.org Accessed 29 April 2019.

- 21. Remington PL, Catlin BB, Gennuso KP. The County Health Rankings: rationale and methods. Popul Health Metr 2015; 13:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 30 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wickham H ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. New York, NY:Springer-Verlag New York; 2016. http://ggplot2.org. Accessed 30 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bivand R, Lewin-Koh N. maptools: Tools for handling spatial objects. 2018. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=maptools. Accessed 30 April 2019.

- 25. Sheehan DM, Fennie KP, Mauck DE, Maddox LM, Lieb S, Trepka MJ. Retention in HIV care and viral suppression: individual- and neighborhood-level predictors of racial/ethnic differences, Florida, 2015. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017; 31:167–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. World Health Organization, Department of HIV/AIDS, World Health Organization, Department of HIV/AIDS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.), Global Fund to Fight AIDS T and Malaria, et al. HIV drug resistance report 2017. 2017.http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/255896/1/9789241512831-eng.pdf. Accessed 16 October 2018.

- 27. Iyengar S, Kravietz A, Bartholomew TS, Forrest D, Tookes HE. Baseline differences in characteristics and risk behaviors among people who inject drugs by syringe exchange program modality: an analysis of the Miami IDEA syringe exchange. Harm Reduct J 2019; 16:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Milloy MJ, Wood E, Kerr T, et al. increased prevalence of controlled viremia and decreased rates of HIV drug resistance among HIV-positive people who use illicit drugs during a community-wide treatment-as-prevention initiative. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:640–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Trepka MJ, Niyonsenga T, Maddox LM, Lieb S. Rural AIDS diagnoses in Florida: changing demographics and factors associated with survival. J Rural Health 2013; 29:266–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the Southern United States. 2016. May. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies/cdc-hiv-in-the-south-issue-brief.pdf. Accessed 16 October 2018.

- 31. Panichsillapakit T, Smith DM, Wertheim JO, Richman DD, Little SJ, Mehta SR. Prevalence of transmitted HIV drug resistance among recently infected persons in San Diego, CA 1996–2013. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 71:228–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kassaye SG, Grossman Z, Balamane M, et al. Transmitted HIV drug resistance is high and longstanding in metropolitan Washington, DC. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:836–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Levintow SN, Okeke NL, Hué S, et al. Prevalence and transmission dynamics of HIV-1 transmitted drug resistance in a Southeastern cohort. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018; 5:ofy178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.