Abstract

Sand seas of Saudi Arabia cover about one-third of the Arabian Peninsula and are still poorly explored in scientific literature. This study aimed to address the floristic structure and association diversity of the inland sand seas in central Saudi Arabia after 20 years of protection. Twenty-three relevés were selected in Nafud Al-Urayq reserve to cover different sandy dune variations. These relevés are subjected to floristic and multivariate analysis of classification with TWINSPAN and ordination with DECORANA & CANOCO techniques. One hundred thirty-five species belonging to 108 genera in 37 families have been recorded. Annual and perennial species are equally represented. Four vegetation groups (i.e., plant associations) are identified as the following: VG I (Haloxylon salicornicum-Lycium shawii-Acacia raddiana), VG II (Calligonum comosum-Tetraena propinqua), VG III (Haloxylon persicum-Haloxylon salicornicum-Stipagrostis drarii), and VG IV (Pulicaria undulata-Citrullus colocynthis). The association of VG I inhabited in the wadi and non-dune or shallow sand habitat had the high species diversity indices (i.e., total species, species richness, species evenness and Shannon index). In contrast, the association of VG II inhabited hyper-arid and salinized habitat and had low species diversity indices. These associations are discussed and illustrated in accordance with competition and adaptation. The advantages of inland sand dune vegetation therefore apply specifically to habitat management and the conservation of plants. These studies extend the advantages of succession of sand dunes and show that rising vegetative diversity is consistent with the combat of desertification.

Keywords: Drought, Fine roots, Psammophytic, Nafud, Sand sea, Steppe vegetation

1. Introduction

The greater parts of Saudi Arabia, which constitute approximately 30% of the total area, are covered by various types of sand dunes (e.g., wind-formed and mobile dunes) and represent unique biological habitat. Most people of the Arabian Peninsula use the Arabic term “Nafud” for land covered by a “sand sea”, and another Arabic term ‘irq (pI. ‘uruq) meaning “vein” for any large, linear sand body. ‘irq is also used to describe a single, elongated sand ridge. These mobile inland dunes or nafuds are very prominent ecosystems in central Saudi Arabia (Alatar et al., 2012, Chaudhary, 1983, Chaudhary and Al-Jowaid, 1999, Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020, El-Sheikh et al., 2010, Mandaville, 1998, Vincent, 2008, Brown, 1960, El-Sheikh et al., 2013).

There is less competition between plants growing on the dunes, and these dune plants require several adaptations to thrive in dune environments. They are highly adapted to low soil water content, high temperature variation, solar radiation, and unstable soil substrate. Sand movement is a major limiting factor for plant growth. The primary adaptation of dune plants to moving sand is the rapid elongation of stems and roots to keep reproductive and photosynthetic organs above the accumulated sand level. Such elongation typically begins when the plants are seedlings and continues as they grow (Alharthi et al., 2020, Bowers, 1982, Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020, El-Sheikh et al., 2010, Mandaville, 1998, Vincent, 2008). Dunes that support enough plant growth and cover will be stabilized by root and stem elongation, and thus, sand movement will cease. Moreover, plant cover changes the shape of the dune and may eventually cause soil to develop. Low areas between dunes are called swales or interdune depressions and may hold permanent water if groundwater is very close to the surface (Bowers, 1982, El-Sheikh et al., 2010, Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020).

Nafud vegetation consists of a series of overlapping plant associations, and their nature depends on physical compositions such as the sediment distribution pattern and the retention capacity and depth of sand. Different associations are proxies for dune sediment. These different associations can be characterized as open dwarf shrubland with spring ephemerals and contain a mixture of widely distributed plants in sandy soils and plants found in adjacent, non-dune habitats (Al-Sodany et al., 2011, Bowers, 1982, Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020, El-Sheikh et al., 2010, Valentini et al., 2020, Vincent, 2008).

Several factors influence the conditions of sediment distribution and retention capacity, such as wind regimes, vegetation cover, runoff, and rainfall. Additionally, anthropogenic activities impact the morphological equilibrium of sand dunes as well as their water and nutrient distribution (El-Sheikh et al., 2010, Duran and Moore, 2013, Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020, Valentini et al., 2020). Zhang and Baas (2012) estimated that vegetation cover of at least 20% played an important role in reducing wind-blown sand transport; thus, the vegetation cover functions as sediment biostabilization for the next serial stage of succession species (Lancaster and Baas, 1998, Nickling and Neuman, 2009, Acosta et al., 2005, El-Sheikh et al., 2010, Leenders et al., 2011, Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020). Therefore, Valentini et al. (2020) stated that geomorphological processes as well as vegetation presence and absence mutually determine the evolution of dune systems, generally known as land–surface eco-morphodynamics. In this context, the spatial relationship between sediment distribution and vegetation cover (vegetated and non-vegetated areas) within dunes, especially inland “nafuds” in Saudi Arabia, still requires further investigation to determine spatial vegetation patterns. Thus, any future development plans for nafuds depend on these studies (El-Sheikh et al., 2010, Pelletier et al., 2015, Yousefi Lalimi et al., 2017, Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020).

To improve our understanding of the vegetation structure and spatial pattern relationships of the nafud environment’s sediment, we developed an approach to assess whether vegetation association, elevation, slope, and undulating topography are spatially correlated with sand cover after excluding human impacts. To test these hypotheses, vegetation and topographic characterizations were obtained using a multivariate analysis method (Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020, El-Sheikh et al., 2010, Holm, 1953) that enables the integration of observations in nafud environments with different tools. Our aims are to 1) examine the nafud vegetation structure and their floristic diversity after 20 years of protection, and 2) show how geomorphic features interact with the vegetation distribution spatial patterns.

This paper aims to assess the vegetation association structure of the inland sand dunes of central Saudi Arabia. Only active dunes or dune fields with substantial active areas are discussed in detail.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study area

Although the study area is covered by sand, there are also some microhabitat areas such as differently sized sandy dunes, small rock formations, hills or hillocks, wadis, and depressions. Nafud Al-Urayq is a protected area situated in the central region of Saudi Arabia. It is located between 24.750174 and 25.552082 N and 42.437837–42.580600 E with an area of 1641 km2, length of 144 km, width of 7–17 km, and perimeter of 397 km2 (Fig. 1). The area is composed of Quaternary aeolian sand overlying the crystalline rocks. Surrounded by several small villages, the area is fully covered by dunes, rising to a maximum of approximately 100 m. It is a long and narrow sand body. Two major wadis and their tributaries join at the northern edge of the area. During the rainy season, water flows from west to east, which provides a supply channel for both tributaries, and disseminates to the protected area. Although sand covers the entire area, small rock formations, hills, and hillocks can be found on the entire eastern side just outside the main sand body. The northeastern sides of the protected areas are also bordered by isolated rocky hillocks and granite inselbergs, mostly devoid of vegetation. During rainy days, the depressions collect water; these water bodies often remain for several weeks, creating silty habitats conducive for annual growth.

Fig. 1.

Location map of nafud Al-Urayq.

2.2. Climate

Based on weather reports collected during 2005–2014, the mean climate data for the area is as follows: high temperature (44 °C), low temperature (7 °C), average temperature (26 °C), precipitation (0.9 mm), humidity (30%), dew point (3 °C), wind (11 km/h), pressure (1009 mbar), and visibility (10 km). The climate diagram of temperature and precipitation readings was drawn and obtained during the same period at Prince Naif Bin Abdulaziz Airport in the Qassim region. Nafud Al-Urayq inland dunes lie in hot and hyper-arid regions, where summer temperatures typically exceed 40 °C in June, July, and August. The maximum precipitation was 96.00 mm in January, and annual precipitation was 0.9 mm per year (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Climate diagram of nafud Al-Urayq.

2.3. Data collection

Twenty-three relevés, approximately 50 × 50 m in size, in the nafud protected area (~397 km2) were selected to represent all microhabitat variations and analyze the study area’s vegetation structure. Data collection occurred in the spring of 2016. In each relevé, species were listed and identified, and their life forms and chorotypes were classified according to (Collenette, 1999, Chaudhary, 1999-2001). The plant cover value of all species in each relevé was estimated as the abundance cover percentage, according to (Kent, 2012).

2.4. Data analysis

To obtain the classification and ordination of vegetation groups or associations, two-way indicator species analysis (TWINSPAN) and detrended correspondence analysis (DECORANA) programs (Hill, 1979, Hill, 1979) of multivariate analysis were applied to the matrix dataset (23 relevés × 106 species cover values). TWINSPAN produces a classification of vegetation groups (i.e., plant associations), and these associations were named after their dominant species. DECORANA was applied to the same set of dataset to confirm the separation between the vegetation groups identified by TWINSPAN. Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) was performed using Canoco 4.5 to correlate between the relevés, species, and community variables in the dataset (Ter Braak and Smilauer, 2002).

Species richness of each vegetation group or association was calculated as the average number of species per relevé. The species cover importance value was used to assess the species relative evenness using the Shannon-Weaver index:, and the species relative concentration dominance using the Simpson index: C where (s) is the species number and (pi) is the relative cover value of the (ith) species. More details about these indices are available in (Magurran, 1988, Pielou, 1975, Whittaker, 1972).

Biplot score of community variables (i.e., diversity indices and relevé elevation) correlation was used to analyze the relationship of these variables with the DCA axes; this technique enables the elimination of insignificant variables, and only those that had the most important correlations with dependent variables were selected by CCA (Ter Braak and Smilauer, 2002). The significance of variation in the vegetation units’ diversity indices and elevation variables was tested using one-way ANOVA.

3. Results

3.1. Floristic diversity and phytogeography

One hundred thirty-five species belonging to 108 genera from 37 plant families have been recorded. Among these, Poaceae and Asteraceae (each with 19 spp.) represent the largest families, followed by Fabaceae with 11 species. Sixteen families are represented by only one species each. Tree species are sparse in the surveyed area and represent only 2 (1.5%) species, namely, Acacia raddiana and Tamarix aphylla. Annuals herbs and sub-shrubs (perennial herbs) are the major groups with 63 (47.7%) and 38 (28.1%) species, respectively, followed by perennial grasses and shrubs with 16 (11.9%) and 11 (8.1%) species, respectively. The proportion of annual grasses in the study area is insignificant, represented by only 5 (3.7%) species, such as Aristida adscensionis, Phalaris minor, and Schismus barbatus (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Life-form spectrum of nafud Al-Urayq.

Since the protected area is located within the Saharo-Arabian phytogeographical zone, the highest number of species comes from this zone. Approximately 44% (48 spp.) belong to this category, followed by 14% (19 spp.) from Saharo-Arabian-Somalia-Masai, and Saharo-Arabian-Irano-Turanian 10% (11 spp.) categories. However, there are incursions of species from other phytogeographical zones such as Irano-Turanian, Mediterranean, Somalia Masai, Sahelian, and tropical regions (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Chorotype spectrum of nafud Al-Urayq. The categories are: IT (Irano-Turanian); ME (Mediterranean); SA (Saharo-Arabian); SH (Sahelian); SM (Somalian); Pal (Paleotropical); TR (Tropical).

3.2. Vegetation structure

Twenty-three relevés were selected as sampling spots to record the cover value of the 106 species. An analysis of these values has shown that the entire vegetation can be divided into four vegetation groups, or associations, each located in a specific habitat. Some species are widely distributed with appreciable abundance, while others have a restricted distribution range. The characteristic communities are as follows: VG I: Haloxylon salicornicum-Lycium shawii-Acacia raddiana; VG II: Calligonum comosum-Tetraena propinqua; VG III: Haloxylon persicum-Haloxylon salicornicum-Stipagrostis drarii; and VG IV: Pulicaria undulata-Citrullus colocynthis (Table1, Table 2, Fig. 5 and Fig. 7).

Table1.

Synoptic table of the percentage frequency of the recorded species in nafud Al-Urayq. The characteristics species of vegetation groups after TWINSPAN are: VG I:Haloxylon salicornicum-Lycium shawii-Acacia raddiana; VGII: Calligonum comosum-Tetraena propinqua; VG III: Haloxylon persicum-Haloxylon salicornicum-Stipagrostis drarii and VG IV: Pulicaria undulata-Citrullus colocynthis.

| Group No. | Life Forms | Chorotypes | 1 234 |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of relevés | 4 2 13 4 | ||

| Haloxylon salicornicum | Sub-Shrub | SA | 75 . 77 75 |

| Pulicaria undulate | Sub-Shrub | SA-SM | 25 . .75 |

| Citrullus colocynthis | Sub-Shrub | SA | 75 . . 75 |

| Ajuga arabica | Sub-Shrub | IT | 25 . . 50 |

| Panicum turgidum | Perennial | SA-SM | 75 . 8 . |

| Launaea capitata | Ann. Herb | SA | 50 . 15 . |

| Stipagrostis drarii | Per. Grass | SA | 25 . 54 25 |

| Moltkiopsis ciliata | Sub-Shrub | SA | . 50 23 . |

| Calligonum comosum | Shrub | SA-IT | . 50 8 . |

| Tetraena propinqua | Sub-Shrub | SA | . 50 8 . |

| Eremobium lineare | Ann. Herb | SA | . . 23 25 |

| Haloxylon persicum | Shrub | IT | . . 54 . |

| Plantago boissieri | Ann. Herb | SA | . . 23 . |

| Polycarpaea repens | Sub-Shrub | SA-SM | . . 23 . |

| Cyperus conglomerates | Sub-Shrub | SA | . . 23 . |

| Anisosciadium lanatum | Ann. Herb | SA | . . 15 . |

| Anthemis deserti | Ann. Herb | SA | . . 15 . |

| Arnebia hispidissima | Ann. Herb | SA | . . 15 . |

| Asphodelus refractus | Ann. Herb | SA | . . 15 . |

| Atractylis carduus | Ann. Herb | SA | . . 15 . |

| Bassia muricata | Ann. Herb | SA-IT | . . 15 . |

| Acacia ehrenbergiana | Shrub | SM | . . 8 . |

| Andrachne telephioides | Sub-Shrub | ME-IT | …50 |

| Capparis spinosa | Shrub | ME-SA | …50 |

| Euphorbia dracunculoides | Sub-Shrub | SA | …50 |

| Lycium shawii | Shrub | SA-SH | 75… |

| Rhanterium epapposum | Sub-Shrub | SA | 50… |

| Aerva javanica | Sub-Shrub | Pal | 50… |

| Acacia raddiana | Tree | SM | 50… |

| Blepharis ciliaris | Ann. Herb | SA-SH | 50… |

| Ephedra foliate | Shrub | SA-IT | 50… |

| Farsetia aegyptiaca | Sub-Shrub | SA-SH | 50… |

| Gymnocarpos decander | Sub-Shrub | SA | 50… |

| Ochradenus baccatus | Shrub | SA-SM | 50… |

| Paronychia arabica | Ann. Herb | SA | 50… |

| Teucrium polium | Sub-Shrub | ME-IT | 50… |

| Hibiscus micranthus | Shrub | Pal | 50… |

| Heliotropium bacciferum | Sub-Shrub | SA-SH | 50… |

| Asphodelus tenuifolius | Ann. Herb | SA-SH | 25. 15. |

| Euphorbia retusa | Sub-Shrub | SA | 25.. 25 |

| Acacia tortilis | Shrub | SM | 25… |

| Althaea ludwigii | Ann. Herb | SA | 25… |

| Aristida adscensionis | Ann. Grass | SA | 25… |

| Asteriscus heirochunticus | Ann. Herb | SA | 25… |

| Centaurea bruguieriana | Ann. Herb | SA | 25… |

| Centaurea pseudosinaica | Ann. Herb | SA | 25… |

| Cheilanthus sp. | Sub-Shrub | SA-IT | 25… |

| Chrysopogon plumulosus | Per. Herb | SA-SM | 25… |

| Convolvulus oxyphyllus ssp. oxycladus | Sub-Shrub | SA | 25… |

| Convolvulus pilosellifolius | Sub-Shrub | IT | 25… |

| Cynodon dactylon | Per. Grass | TR | 25… |

| Diplotaxis acris | Ann. Herb | SA | 25… |

| Echinops polyceras | Sub-Shrub | IT | 25… |

| Emex spinosa | Ann. Herb | ME-SA | 25… |

| Enneapogon desvauxii | Per. Grass | SA-IT | 25… |

| Eragrostis barrelieri | Per. Grass | ME-SA | 25… |

| Erodium laciniatum | Ann. Herb | ME | 25. 15 |

| Fagonia bruguieri | Sub-Shrub | SA | 25… |

| Forsskaolea tenacissima | Sub-Shrub | SA-SM | 25… |

| Halothamnus iraqensis | Sub-Shrub | SA | 25… |

| Helianthemum lippii | Sub-Shrub | SA-SM | 25… |

| Hyparrhenia hirta | Ann. Grass | ME-IT-SA | 25… |

| Launaea mucronata | Ann. Herb | SA | 25. 15. |

| Launaea nudicaulis | Ann. Herb | SA | 25… |

| Medicago laciniata | Ann. Herb | SA | 25… |

| Morettia parviflora | Sub-Shrub | SM | 25… |

| Pergularia tomentosa | Sub-Shrub | SM-SH | 25.. 25 |

| Plantago ovate | Ann. Herb | SA-IT | 25… |

| Polygala erioptera | Sub-Shrub | SA-SM | 25… |

| Pulicaria incise | Sub-Shrub | SA | 25… |

| Salvia deserti | Sub-Shrub | SA | 25… |

| Senecio flavus | Ann. Herb | SA | 25… |

| Stipagrostis plumosa | Per. Grass | SA-IT | 25… |

| Tamarix nilotica | Shrub | SA | 25… |

| Tetrapogon villosus | Per. Grass | SA-SM | 25… |

| Tribulus terrestris var. terrestris | Ann. Herb | Pal | 25… |

| Trichodesma africanum | Sub-Shrub | SA-SH | 25… |

| Zilla spinosa | Ann. Herb | SA | 25… |

| Centaurea sp. | Ann. Herb | SA | .15. |

| Centropodia forsskalii | Per. Grass | SA-IT | . . 15 . |

| Cleome ambyocarpa | Ann. Herb | SA-SM | . . 15 . |

| Convolvulus buschiricus | Sub-Shrub | SA | . . 15 . |

| Euphorbia granulate | Sub-Shrub | SA-SM | . . 15 . |

| Fagonia glutinosa | Sub-Shrub | SA | . . 15 . |

| Farsetia stylosa | Sub-Shrub | SA-SH | . . 15 . |

| Calotropis procera | Shrub | SM-SH | . . 8 . |

| Cistanche phelypaeae | Sub-Shrub | SA-IT | . . 8 25 |

| Gisekia pharnaceoides | Ann. Herb | TR | …25 |

| Glossonema boveanum ssp. boveanum | Sub-Shrub | SM-SH | . . 15 . |

| Glossonema variens | Sub-Shrub | SM-SH | . . 15 . |

| Haplophyllum tuberculatum | Sub-Shrub | SA | . . 15 . |

| Horwoodia dcksoniae | Ann. Herb | SA | . . 15 . |

| Ifloga spicata | Ann. Herb | SA | . . 15 . |

| Kohautia caespitosa | Sub-Shrub | SA-SM | . . 15 . |

| Lotononis platycarpos | Ann. Herb | SA-SM | . . 15 . |

| Malva parviflora | Ann. Herb | ME-IT | . . 15 . |

| Monsonia nivea | Ann. Herb | SA-SM | . . 8 . |

| Neurada procumbens | Ann. Herb | SA | . . 23 . |

| Ochthochloa compressa | Per. Grass | SA-IT | . . 15 . |

| Plantago amplexicaulis | Ann. Herb | SA | . . 15 . |

| Plantago cilata | Ann. Herb | SA | . . 15 . |

| Reseda arabica | Ann. Herb | SA | . . 15 . |

| Savignya parviflora | Ann. Herb | SA | . . 15 . |

| Schismus barbatus | Ann. Grass | SA-IT | . . 8 . |

| Sclerocephalus arabicus | Sub-Shrub | SA | . . 15 . |

| Seetzenia lanata | Ann. Herb | SM | …15. |

| Senna italica | Sub-Shrub | SM | …25 |

| Tamarix aphylla | Tree | SM | 25… |

Categories, are: IT (Irano-Turanian); ME (Mediterranean); SA (Saharo-Arabian); SH (Sahelian); SM (Somalian); Pal (Paleotropical); TR (Tropical).

Table 2.

Biplot scores of the environmental variables with the ordination axes.

| N | NAME | AX1 | AX2 | AX3 | AX4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Total species | 0.8090*** | 0.3877 | 0.3914 | −0.0185 |

| 2 | Total cover % | 0.1347 | −0.5494** | 0.0977 | −0.2274 |

| 3 | Species richness | 0.7832*** | 0.4339* | 0.4125 | 0.0453 |

| 4 | Species Evenness | 0.4722* | 0.0438 | −0.0494 | 0.4792 |

| 5 | Shannon index | 0.7984*** | 0.2486 | 0.3484 | 0.1494 |

| 6 | Simpson index | −0.7292*** | 0.0246 | −0.2243 | −0.2135 |

| 7 | Altitude m. | 0.8307*** | −0.3585 | −0.0475 | 0.2361 |

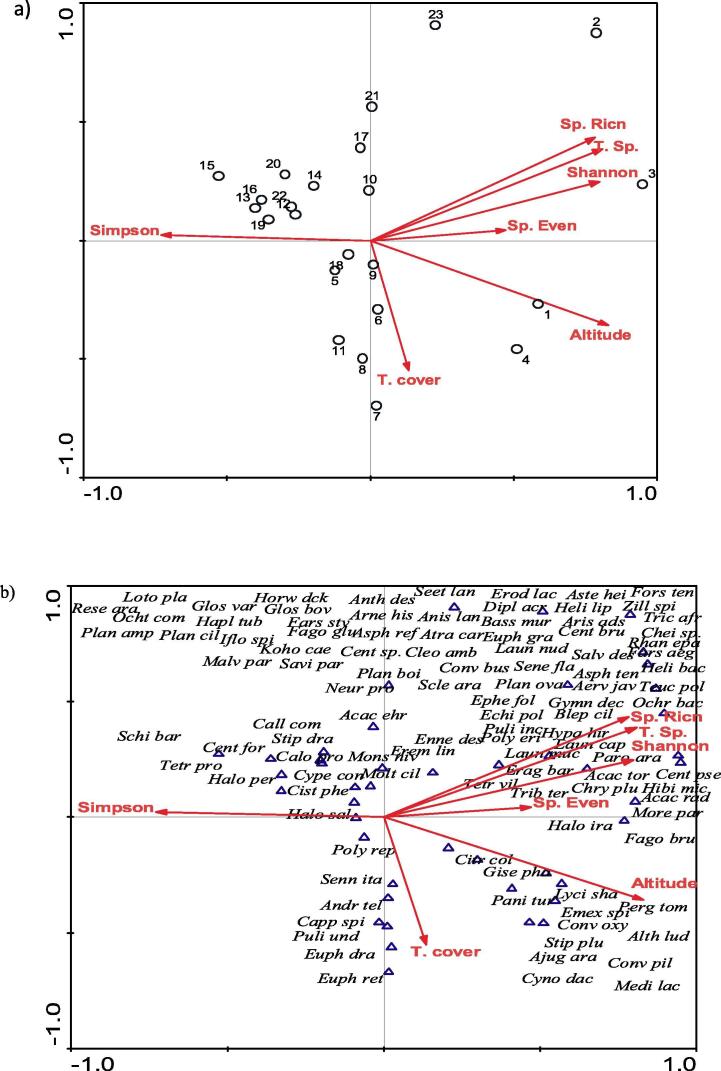

Fig. 5.

Multivariate analysis of the relevés by a)TWINSPAN and ordination b)DECORANA. Four vegetation groups identified after TWINSPAN are: VG I- Haloxylon salicornicum-Lycium shawii-Acacia raddiana; VGII- Calligonum comosum-Tetraena propinqua; VG III- Haloxylon persicum-Haloxylon salicornicum-Stipagrostis drarii and VG IV- Pulicaria undulata- Citrullus colocynthis.

Fig. 7.

Representation of the four associations with their dominant species on inland sand dunes of nafud Al-Urayq.

VG I (Haloxylon salicornicum-Lycium shawii-Acacia raddiana): This association abundantly inhabits the southern area and north periphery of Nafud Al-Urayq, where sand dunes are relatively absent. It dominates in the wadis, hill slopes, foothills, and some depression areas (Fig. 7a). The flat wadi beds running from rocky hills are inhabited by Acacia raddiana and Acacia tortilis trees, which are somewhat healthy. Some of these trees reach a height of approximately 6 m or more, indicating less grazing. Additionally, shrubs and sub-shrubs such as Ephedra foliata, Lycium shawii, Hibiscus micranthus, Rhanterium epapposum, and Gymnocarpos decander are common in this habitat (Fig. 7b). The terrain is rocky and overlaid by a sheet of less mobile sand and slopes of small hillocks, which support the growth annuals such as Launaea capitata, Citrullus colocynthis, Senecio flavus, and Launaea spp.. In some shallow depressions, two other species are evenly dominant: Pulicaria undulata, and the non-palatable species Euphorbia retusa. The most associated species of this community are: Panicum turgidum, Aerva javanica, Ajuga arabica, Citrullus colocynthis, Euphorbia retusa, Pulicaria undulata, Blepharis ciliaris, Farsetia aegyptiaca, Ochradenus baccatus, Paronychia arabica, Teucrium polium, Hibiscus micranthus, Heliotropium bacciferum, and Asphodelus tenuifolius.

VG II (Calligonum comosum-Tetraena propinqua): This association represents the study area’s hyper-arid and salinized habitat. It has fewer plant species. This association inhabits the top and edges of sand dune habitat as psammophytic species (Fig. 7c). This association’s co-dominant population inhabits the smallest semi-sabkhas among all other prominent ones and, therefore, is not significant in the study area (Fig. 7d). It is dominated by Tetraena propinqua (Syn.), Zygophyllum migahidii, and associated with Moltkiopsis ciliata.

VG III (Haloxylon persicum-Haloxylon salicornicum-Stipagrostis drarii): This association is the largest community in Nafud Al-Urayq, covering the majority of sandy seas of the protected area (Fig. 7e). Major parts of this habitat contain high mobile sand dunes, and most species recorded under this community are purely psammophytes possessing adapted xeromorphic features. H. persicum, the keystone species of the area, is a large shrub, reaching a height of approximately 3 m. This Irano-Turanian species is an important component of the sand seas, and its population often forms an isolated “island”. In the past, villagers used to gather its branches to use as firewood. Low lying areas between dunes, or “interdunes”, support a small population of Acacia ehrenbergiana. Other associated species sharing this community are as follows: Neurada procumbens, Cyperus conglomerates, Haloxylon salicornicum, Eremobium lineare, Moltkiopsis ciliata, Polycarpaea repens, Stipagrostis drarii, Plantago boissieri, Polycarpaea repens, Anisosciadium lanatum, Anthemis deserti, Arnebia hispidissima, Asphodelus refractus, Atractylis carduus, Centropodia forsskalei, Savignya parviflora, Horwoodia dicksoniae, Cistanche phylepaea, and Monsonia nivea.

VG IV (Pulicaria undulata-Citrullus colocynthis): This association dominates along the periphery of sand dunes in the southern and northern edge of lower plains in Nafud Al-Urayq and on sand sheets with less mobile sand on the northern side. Most species in this association are composed of herbaceous flora and two even-aged co-dominant species with high biomass (i.e., cover). For example, Capparis spinosa cohabits with Pulicaria undulata as co-dominant species with equal cover along the lower plain of Nafud Al-Urayq (Fig. 7f). The associated species are Haloxylon salicornicum, Ajuga arabica, Eremobium lineare, Andrachne telephioides, Capparis spinosa, Euphorbia dracunculoides, and Pergularia tomentosa.

3.3. Correlation analysis

To evaluate the correlation between major environmental factors, relevés and species Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA) was performed. Vector arrows represent gradients of various parameters which also separate relevés and species according to the match between environmental conditions (Table 2, Fig. 6). A correlation analysis matrix (Table 2, Fig. 6a) gives confirmation on the positive correlation of species diversity indices with the first axis AX1, and negative correlation of species concentration of dominance (Simpson index) AX1. Additionally, the total species cover exhibited negative correlation with AX2.

Fig. 6.

Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA): A bi-plot ordination of the relevés (a) and plant species (b) according to environmental variables. Species names are abbreviated to four letters; for a list of their full names, see Table 1.

Figure (6b) shows that the positive end of the first axis AX1 is associated with psammophytic species which correspond to sandy textures and higher elevations. In contrast, the higher concentration of the “halophytic” species with low elevations are correlated with the negative end of the AX1.

3.4. Community characteristics

The Haloxylon salicornicum-Lycium shawii-Acacia raddiana association (VG I) had the highest species number, species richness, species evenness, Shannon diversity, and altitude, and lower Simpson diversity value (Table 3). In contrast, the Calligonum comosum-Tetraena propinqua association (VG II) had the opposite values. The Pulicaria undulata-Citrullus colocynthis association (VG IV) had higher species total cover value, whereas Haloxylon persicum-Haloxylon salicornicum-Stipagrostis drarii (VG III) had the lowest cover value.

Table 3.

Mean and ± SD of the environmental variables of 4 vegetation groups: VG I- Haloxylon salicornicum-Lycium shawii-Acacia raddiana; VGII-Calligonum comosum-Tetraena propinqua; VG III-Haloxylon persicum- Haloxylon salicornicum-Stipagrostis drarii and VG IV- Pulicaria undulata-Citrullus colocynthis.

| Variables | VG I | VG II | VG III | VG IV | T. mean | F-value | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total species M | 22.00 | 2.00 | 6.38 | 5.25 | 8.52 | 4.269 | 0.018** |

| ±SD | 10.09 | 1.41 | 9.25 | 2.62 | |||

| Total cover M | 62.50 | 62.50 | 54.30 | 85.00 | 61.78 | 2.565 | 0.085 |

| ±SD | 30.55 | 17.67 | 16.28 | 16.63 | |||

| Species richness M | 5.24 | 0.23 | 1.36 | 0.95 | 1.86 | 4.080 | 0.021* |

| ±SD | 2.65 | 0.32 | 2.36 | 0.56 | |||

| Species Evenness M | 0.74 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.920 | 0.450 |

| ±SD | 0.16 | 0.55 | 0.33 | 0.23 | |||

| Shannon index H' M | 0.98 | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 4.761 | 0.012** |

| ±SD | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.19 | |||

| Simpson index CM | 0.20 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 3.851 | 0.026* |

| ±SD | 0.14 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.24 | |||

| Altitude m M | 1066.00 | 822.00 | 856.46 | 964.5 | 908.69 | 26.144 | 0.000*** |

| ±SD | 44.6 | 5.6 | 52.5 | 4.0 | 95.6 |

Maximum and minimum values are bold and underlined.

p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01 and *** p ≤ 0.01, according to one-way ANOVA.

4. Discussion

Nafud Al-Urayq is located in the hyper-arid zone and is mainly composed of psammophilous and xeromorphic shrubs and herbs. Poaceae members or grasses are the dominant ground flora as these plants possess lighter, hairy small seeds and fruits that can be easily distributed along a large area of sand seas by anemochore and desmochore distribution (Shaltout and El-Sheikh, 2003, Danin, 1991). Moreover, the high number of perennial grass species such as Stipagrostis sp., Pennisetum sp., and Panicum sp., which are considered pioneer species, inhabited the mobile sands dunes in large parts of the study area (Al-Turki, 1997). These species form phytogenic hillocks which, are gradually taken over by later successional shrubby species. Also, the age of hillocks is positively correlated with perennial grasses and shrubs (Danin, 1991). In the layers consisting of very fine sand with a higher water holding capacity, the grass roots grow more or less horizontally, and shoot growth may occur using storage water from the older and thicker parts of the rhizomes and roots (Kutschera-Mitter, 1996). Additionally, these adventitious, fibrous grass roots are widely spread horizontally and often completely covered by extensive mucilage cover. The development of this layer is important for root growth as well as microorganism growth and soil biological processes (Kutschera-Mitter, 1996, Lawton, 1996, Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020). Therefore perennial grasses are very important to the sandy ecosystem. In contrast, therophytes are abundant on sandy seas since they either have xeromorphic adaptations or only live for a short period. The life cycle of annuals in this area varies from year to year, depending upon whether conditions are favorable. If the area receives a sufficient amount of rain in a season, the density and abundance of herbaceous flora are significantly high. However, in years of drought, only a few disseminules of the herbs can germinate and produce very few flowers and seeds. Depending on the amount of precipitation, the overall stature of these plants varies from retarded to normal heights (Watts and Al-Nafie, 2003, Al-Turki and AI-Olayan, 2003, Al-Walaie, 1989).

Although the terrain falls within the arid Saharo-Arabian phytogeographical zone and the majority of species belong to the Saharo-Arabian zone, there are intrusions of species from other phytogeographical zones such as Acacias and Astragalus of Somalia Masai, Mediterranean and Irano-Turanian zones respectively; this may be because Nafud Al-Urayq is considered a transitional zone or a midpoint between the Mediterranean and Saharo-Sindian flora of these neighboring zones (see Watts and Al-Nafie, 2003, Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020, Valentini et al., 2020).

The four vegetation units or associations are a diffuse plant cover of shrubs and tufted grasses. Their distribution and nature of these associations are related to the topography and physical characteristics of the sand, as well as seasonal factors. The VG I association (Haloxylon salicornicum-Lycium shawii-Acacia raddiana) inhabits and dominates wadis, hill slopes, foothills, hillocks, and shallow depressions of the southern area and along the periphery of the northern half of the Nafud Al-Urayq where the sand is slightly mobile. Acacia trees, xeromorphic dwarf shrublets and shrubs, and therophytes that dominate the protected area’s southern edge are mostly found at these habitats. Additionally, this association had the highest species number, species richness, species evenness, Shannon diversity and altitude, and a lower concentration of dominance. This result is because these species inhabit the transitional habitats between desert and sand seas, where there is more heterogeneity of substrates in these microhabitats (e.g., rocks, gravels, cracks, sands, silt, clay), and had less of sand mobility in the south and north periphery of Nafud. Therefore, the competition between species was low. For example, 1) the small wadi bed and runnels, where deep soil is accumulated with runoff water, supported dense woody plants (e.g., Acacias, xeromorphic shrubs, and grass vegetation) with high species richness during the rainy season. 2) The rocky terrain habitats overlaid by a sheet of less mobile sand and slopes of small hillocks with relative stability of sand are inhabited by dwarf shrubs and sub-shrubs. 3) Escarpment and cracks between their rocks support sub-shrubs and therophytes. 4) Shallow depressions, where their flat surfaces have accumulated sand, silt, and rainwater during rainy days, support the growth of grasses and annual herbs. Our findings are consistent with (Abbadi and El-Sheikh, 2002, Alatar et al., 2012, Chaudhary, 1983, Springuel et al., 2006, Valentini et al., 2020, Watts and Al-Nafie, 2003, Yousef and El-Sheikh, 1981).

On the other hand, the VG II association (Calligonum comosum-Tetraena propinqua) represented the study area’s hyper-arid and salinized habitat and had the lower species diversity value. It inhabits the top and edge of sand dunes that suffered from instability, wind erosion, evaporation, and drying. This is because the species are adapted to this habitat’s nature and are the best user plants of this arid and salinized habitat. The increasing aridity at its loose and unstable soil surface with high salinity due to excessive evaporation at its surface and high content of sand with poor fertility. Therefore, the adverse environmental factors in this habitat supported a few adapted psammophytic, phytogenic populations of sand binding plants with the highest concentration of their dominance and plays a major role in decreasing species diversity (Alatar et al., 2012, Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020, El-Sheikh and Chaudhary, 1988, Valentini et al., 2020, Watts and Al-Nafie, 2003, Hotzl et al., 1978). Calligonum comosum, a previously dominant population, cohabitating with H. persicum in the northern and central part of Nafud is now in a highly degraded state. The majority of these plants are either dead or possess few live branches. Therefore, the population of Calligonum comosum is in a highly depauperate stage, and most of the plants are in the dying stage. This is primarily due to intensive wood cutting by nearby villagers prior to Nafud becoming designated a protected area, and as a result of the dryness stress of this habitat. This shrub is very popular throughout the Arabian Peninsula for its excellent firewood, which can be used as long and clear burning firewood with less smoke (see Alshammari and Sharawy, 2010, Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020, Watts and Al-Nafie, 2003).

VG III (Haloxylon persicum-Haloxylon salicornicum-Stipagrostis drarii): One morphological characteristic of the sandy deserts of Saudi Arabia is the dominance of Haloxylon persicum. It is a much larger xeromorphic, leafless shrub component of Nafud Al-Urayq, dominating the northern half of the surveyed area. Haloxylon persicum is characteristic of the partially mobile dune area, which is considered the main sandy binder. The net of stems can collect the sand particles around the plant and form phytogenic nabkhas. These nabkhas can be seen growing up more than 10 m or more in height over the parent surface of the desert and can connect with neighboring nabkhas to form a continuous series of high overlapping dunes over large areas such as sand seas or Nafud (Al-Hemaid, 1996, El-Ghanim et al., 2010, Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020, El-Sheikh et al., 2010, Ghazanfar and Fisher, 1998). Haloxylon persicum posses’ compensation factor as a strategy to overcome burial by sands through regenerating many new individuals as a result of its high rate of seed germination and water availability under sandy soil; thus, it is considered a highly adapted plant in the Nafud ecosystem (Bowers, 1982, Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020, El-Sheikh et al., 2010, Migahid and El-Sheikh, 1977, Valentini et al., 2020). After the relative stability of mobile sand around Haloxylon persicum the nabkhas act as shelter and home to a number of growing psammophytic sub-shrubs and herbs with low plant cover (Elmefregy and El-Sheikh, 2020, Vesey-Fitzgerald, 1957, Baierle and Frey, 1986).

The Pulicaria undulata-Citrullus colocynthis association (VG IV) inhabits the lower plains or sand sheets with less mobile sand at the Nafud edges, indicating that area could be considered a shallow depression that receives excessive amounts of clay, silt, sand, and rainwater from the runoff of neighboring rocky ridges or escarpments. This association had the higher species total plant cover and low species diversity because a couple of the herbaceous species are highly adapted to this habitat and are considered the best users of the resources considering the high competition with other species of this lower plains. For example, Capparis spinosa and Pulicaria undulata have a similar evenness cover and are co-dominant species. Moreover, in the lower plain habitats, herbaceous and sub-shrub species with shallow adventitious fine roots are dominant, while woody shrubs are absent due to the hardpan soil substrate (Abbadi and El-Sheikh, 2002, Alharthi et al., 2020, Blot and Hajar, 1994, Valentini et al., 2020).

5. Conclusion

The ecological diversity of flora and vegetation along the various habitats of the 'nafud' inland sand dunes in the Najd region was measured and compared. Four vegetation groups were recognized by TWINSPAN, from a sample of 22 surveys. The findings revealed that the wadi and non-dune or shallow sand habitat associations of VG I (Haloxylon salicornicum-Lycium shawii-Acacia raddiana) and VG III (Haloxylon persicum-Haloxylon salicornicum-Stipagrostis drarii), inhabited on the series of partially stable dunes, have high species diversity indices. These ecosystems have high soil humidity, less sand motion and less salinity which have favored the development of more psammophytic and woody plants. In comparison, the VG II (Calligonum comosum-Tetraena Propinqua), a living hyper-arid habitat with a low species diversity and with halophytic subshrubs, was dominated. The advantages of inland sand dune vegetation therefore apply specifically to habitat management and the conservation of plants. These studies extend the advantages of succession of sand dunes and show that rising vegetative diversity is consistent with the combat of desertification.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP-2020/182), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Alatar A.A., El-Sheikh M.A., Thomas J. Vegetation analysis of Wadi Al-Jufair, a hyper arid region in Central Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2012;19:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Alharthi A., El-Sheikh M.A., Elhag M., Alatar A.A., Abbadi G.A., Abdel-Salam E.M., Arif I.A., Baeshen A.A., Eid E.M. Remote sensing of 10 years changes in the vegetation cover of the northwestern coastal land of Red Sea. Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020;27:3169–3179. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hemaid F.M. Vegetation and distribution of the sand seas in Saudi Arabia. Geobios. 1996;23:2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Alshammari A.M., Sharawy S.M. Wild plants diversity of the Hema Faid region (Hail Province, Saudi Arabia) Asian J. Plant Sci. 2010;9:447–454. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sodany Y.M., Mosallam H.A., Baziad S.A. Vegetation analysis of Mahazat Al-Sayd Protected area: the second largest fenced nature reserve in the world. World Appl. Sci. J. 2011;15:1144–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Turki T.A. A preliminary checklist of the flora of Qassim. Saudi Arabia. Feddes Repert. 1997;108:259–280. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Turki, T.A., AI-Olayan, H.A., 2003. Contribution to The Flora Of Saudi Arabia: Hail Region. Saudi J. Bio. Sci. 10, 190-222.

- Al-Walaie, A.N., 1989. Factors contributing to the degradation of the environment in central, eastern and northern Saudi Arabia, in: Wildlife Conservation and devpt. in Saudi Arabia. Proceedings of the first symposium NCWCD, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, pp. 37-61.

- Abbadi G.A., El-Sheikh M.A. Vegetation analysis of Failaka Island (Kuwait) J. Arid Environ. 2002;50:153–165. doi: 10.1006/jare.2001.0855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta A., Carranza M.L., Izzi C.F. Combining land cover mapping of coastal dunes with vegetation analysis. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2005;8:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Baierle, H.U., Frey, W., 1986. A Vegetational transect through central Saudi Arabia (At-Taif-Ar-Riyadh) in Kurschner, H. (ed). 1986a, 111-136.

- Blot J., Hajar A.S. Report to the NCWCD; Riyadh: 1994. Evaluation of the ecological situation of the Raydah Protected area, first report. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers J.E. The plant ecology of inland dunes in western North America. J. Arid Environ. 1982;5:199–220. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.F., 1960. Geomorphology of Western and Central Saudi Arabia. 21st International Geol. Cong. Copenhagen, Re. 21, 150-159.

- Chaudhary S.A. Vegetation of Great Nafud. Saudi Arabian Nat. Hist. Soc. 1983;2:32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary S.A., Al-Jowaid A.A. Ministry of Agriculture and Water; Riyadh: 1999. Vegetation of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, S.A., 1999-2001. Flora of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Vol I-III, Ministry of Agriculture and Water, Riyadh.

- Collenette I.S. National Commission for Wildlife Conservation; Riyadh: 1999. Wildflowers of Saudi Arabia. [Google Scholar]

- Danin A. Plant adaptations in desert dunes. J. Arid Environ. 1991;21(193–21):2. [Google Scholar]

- Duran O., Moore L.J. Vegetation controls on the maximum size of coastal dunes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:17217–17222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307580110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ghanim W.M., Hassan L.M., Galal T.M., Badr A. Floristic composition and vegetation analysis in Hail region north of central Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2010;17:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmefregy M., El-Sheikh M.A. Ecological status of sand binder plant white saxaul (Haloxylon persicum) at the managed area of Qassim, Saudi Arabia. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2020;18:2781–2794. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh A.M., Chaudhary S.A. Plants and plant communities of the Al-Harrah protected areas. Proc. Saudi Biol. Soc. 1988;11:211–235. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M.A., Abbadi G.A., Bianco P.M. Vegetation ecology of phytogenic hillocks (nabkhas) in coastal habitats of Jal Az-Zor National Park, Kuwait: Role of patches and edaphic factors. Flora. 2010;205:832–840. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh, M.A., Thomas, J., Alatar, A.A., Hegazy, A.k., Abbady, G.A., Alfarhan, A.H., Okla, M.I., 2013. Vegetation of Thumamah Nature Park: a managed arid land site in Saudi Arabia. Rend. Fis. Acc. Lincei 24, 349–367.

- Ghazanfar S.A., Fisher M. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht: 1998. Vegetation of the Arabian Peninsula. [Google Scholar]

- Hill M.O. DECORANA: A FORTRAN Program for Detrended Correspondence Analysis and Reciprocal Averaging. Section of Ecology and Systematics. Cornell University; NY: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hill M.O. of Ecology and Systematics. Cornell University; NY: 1979. TWINSPAN: A FORTRAN Program for Arranging Multivariate Data in an Ordered Two-way Table by Classification of the Individuals and Attributes. Section. [Google Scholar]

- Holm D.A. Dome-shaped dunes of Central Nejd, Saudi Arabia. International Geolog. Congress, 19th, Algeiro. 1952. Comptes Rendus. 1953;7:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hotzl, H., Felber, H., Maurin, V., Zotl, J.G., 1978. Regions of Investigation: Cuesta region of the Tuwayq mountains, in: Al-Sayari, S.S., Zotl, J.G. (Eds.), Quaternary Period in Saudi Arabia Vol. 2. Sedimentological, Hydrological, Geomorphological, Geochronological and limatological investigations in Central and Eastern Saudi Arabia. Springer Verlag, Wien., pp. 194-226.

- Kutschera-Mitter, L. 1 996. Growth strategies of plant roots in different climatic regions. Acta Phytogeogr. Suec. 81, Uppsala.

- Kent M. Vegetation Description and Data Analysis: A Practical Approach. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster N., Baas A. Influence of vegetation cover on sand transport by wind: Field studies at Owens Lake California. Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 1998;23:69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton R.M. The ecological importance of root systems in the woodlands of Central Africa and in the desert plants of Oman. Acta Phytogeogr. Suec. 1996;81:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Leenders J.K., Sterk G., Van Boxel J.H. Modelling wind-blown sediment transport around single vegetation elements. Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 2011;36:1218–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran A.E. Ecological Diversity and its Measurement. Chapman & Hall; London: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Mandaville J.P. Vegetation of the Sands. In: Ghazanfar S.A., Fisher M., editors. Vegetation of the Arabian Peninsula. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Migahid A.M., El-Sheikh A.M. Types of desert habitat and their vegetation in Central and Eastern Saudi Arabia. Prod. Saudi Bio. Soc. 1977;2:5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Nickling W.G., Neuman C.M. Springer:; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2009. Aeolian sediment transport., in: Geomorphology of Desert Environments; pp. 517–555. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier J.D., Brad Murray A., Pierce J.L., Bierman P.R., Breshears D.D., Crosby B.T., Ellis M., Foufoula-Georgiou E., Heimsath A.M., Houser C. Forecasting the response of Earth’s surface to future climatic and land use changes: A review of methods and research needs. Earth’s Future. 2015;3:220–251. [Google Scholar]

- Pielou E.C. Ecological Diversity. Wiley; New York: 1975. p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- Shaltout K.H., El-Sheikh M.A. Vegetation of the urban habitats in the Nile Delta region. Egypt. Urban Ecosys. 2003;6:205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Springuel I., Sheded M., Darius F., Bornkamm R. Vegetation dynamics in an extreme desert wadi under the influence of episodic rainfall. Polish Botanical Studies. 2006;22:459–472. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Braak C.F.G., Smilauer P. CANOCO Reference Manual and CanoDraw for Window’s User’s Guide: Software for Canonical Community Ordination(Version 4.5) CANOCO; Ithaca, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Valentini E., Taramelli A., Cappucci S., Federico Filipponi F., Xuan A.N. Exploring the dunes: the correlations between vegetation cover pattern and morphology for sediment retention assessment using airborne multisensor acquisition. Remote Sens. 2020;12:1229. [Google Scholar]

- Vesey-Fitzgerald D.F. The vegetation of Central and Eastern Saudi Arabia. J. Eco. 1957;45:779–798. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent P. Taylor & Francis Group; London, UK: 2008. Saudi Arabia: An Environmental Overview. [Google Scholar]

- Watts D., Al-Nafie A.H. Kegan Paul; England: 2003. Vegetation and biogeography of the sand seas of Saudi Arabia. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker R.H. Evolution and measurement of species diversity. Taxon. 1972;21:213–251. [Google Scholar]

- Yousef M.M., El-Sheikh A.M. Observations on the vegetation of gravel desert areas with special reference to succession in Central Saudi Arabia. J. Coll. Sci. 1981;12:331–351. [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi Lalimi F., Silvestri S., Moore L.J., Marani M. Coupled topographic and vegetation patterns in coastal dunes: Remote sensing observations and ecomorphodynamic implications. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2017;122:119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Baas A.C. Mapping functional vegetation abundance in a coastal dune environment using a combination of LSMA and MLC: A case study at Kenfig NNR. Wales. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2012;33:5043–5071. [Google Scholar]

Further reading

- Schultz E., Whitney J.W. Vegetation in north-central Saudi Arabia. J. Arid Environ. 1986;10:175–186. [Google Scholar]