Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to identify the predictors of hospitalization in older (≥60 years) patients with coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

Patients were randomly selected from a COVID-19 database maintained by the Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia. All patients were aged ≥60 years, had reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)-confirmed COVID-19, and were registered in the database during March 2020 to July 2020. Medical and sociodemographic characteristics were retrieved from the database. Additional data were collected by telephone interviews conducted by trained health professionals. Descriptive statistics and multiple logistic regression analyses were used to analyze the relationship between patient characteristics and the risk of hospitalization.

Results

Of the 613 included patients (51.1% females), more than half (57.3%) were between 60 to 69 years of age, and 53% (324/613) had been hospitalized. The independent predictors of hospitalization included age ≥65 years (OR = 2.35, 95% CI: 1.66–3.33, P < 0.001), having more than one comorbidity (OR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.09–2.20, P = 0.01), diabetes mellitus (OR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.09–2.11, P = 0.01), hypertension (OR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.007–1.97, P = 0.04), chronic kidney disease (OR = 3.87, 95% CI: 1.41–10.58, P = 0.008), and history of hospital admission within the preceding year (OR = 1.69, 95% CI: 1.11–2.55, P = 0.013). Risk of hospitalization was lower in males (OR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.43–0.90, P = 0.01) and in patients co-living with health care workers (OR = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.43–0.96, P = 0.03).

Conclusion

Factors associated with higher risk of COVID-19-associated hospitalization should be used in prioritizing older adults’ admission. Future studies with more robust designs should be conducted to examine the risk of COVID-19-associated illness severity and mortality.

Keywords: COVID-19, older adults, hospitalization, diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

The coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has ravaged the world for more than a year and caused more than two million deaths.1,2 Multiple studies have shown that older adults with COVID-19 have high risk of mortality, mainly due to the presence of multiple comorbidities.3–7 In addition, many studies have shown that older patients are more likely to need intensive care unit (ICU) admission for management of respiratory complications.8–11 Among the elderly, heart failure, peripheral artery disease, C-reactive protein level, need for oxygen support, respiratory rate, presence of lung crackles at presentation, shorter interval from onset of symptoms to hospitalization, length of hospital stay, and male sex have been shown to be associated with higher risk of mortality;12 however, old age remains an independent risk factor for both hospitalization and mortality after controlling for a myriad of factors.13–16

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia reported its first case of COVID-19 on March 2, 2020, and by November 17, 2020, a total of 353,918 confirmed COVID-19 cases had been reported.17,18 As in other countries, it is highly likely that older Saudi patients with COVID-19 — especially those with comorbidities such as, diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and bronchial asthma — have higher risk of hospitalization and death.12–16,19–21 However, no study has so far explored the predictors of hospitalization in this vulnerable population in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, in this study we aimed to determine the sociodemographic and clinical predictors of hospitalization in older adults with COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. Better awareness regarding the risk factors for hospitalization will be useful for health policy planning and will enable more efficient allocation of limited resources.

Methods

Study Population and Data Collection

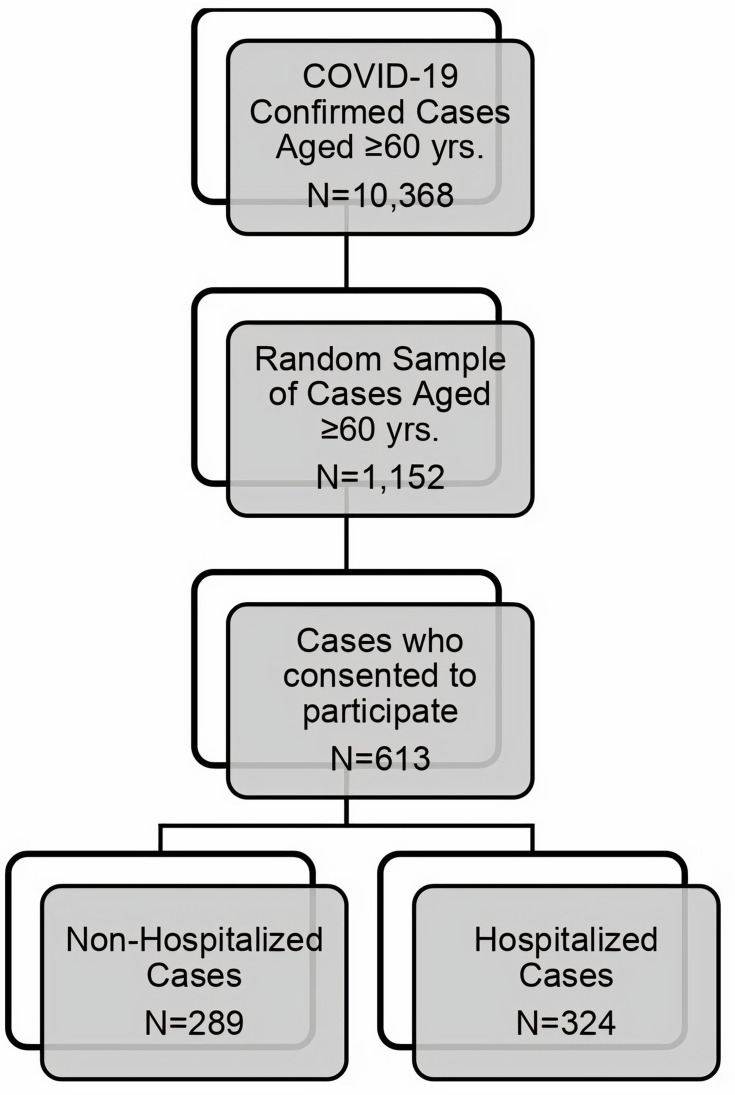

The study population was selected from the COVID-19 database maintained by the Ministry of Health (MOH) Saudi Arabia.18 This database, which is part of the Health Electronic Surveillance Network (HESN), contains the details of all reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)-confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. A total of 10,368 elderly (≥60 years) COVID-19 patients were registered in the database from March 2020 to June 2020. We performed systematic random sampling and selected every ninth patient for this cross-sectional study. The 1152 patients thus selected were contacted over the telephone and asked about their willingness to participate in the study. Only those who were willing to sign written informed consent and provide all requested information were included in the study.

Medical and sociodemographic data of the enrolled patients including proof of hospitalization were retrieved from the database. Further, seven trained MOH employees (one physician, five nurses, and one administrative assistant) contacted each patient over the telephone to collect additional data regarding marital status, educational level, smoking history, whether co-living with a healthcare worker (HCW), whether hospitalized for COVID-19, number and type of comorbidities, history of hospital admission for other diseases in the preceding year, symptoms, and so on. Comorbidities were classified according to the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10).22 The data collection took place between July and September 2020. The collected information was systematically entered into an electronic database that was regularly reviewed by the first and third authors to ensure consistency.

The ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were adhered to during collection, handling, and storage of data, and all care was taken to protect patient confidentiality. This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board Committee of the Central Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (No: 20–156M).

Statistical Analysis

Assuming a response rate of 50%, a minimum sample size of 371 would be required to detect a significant difference between groups with a margin of error of 5%. However, to ensure sampling adequacy, a sample size of at least 415 patients was planned. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages and compared between groups using the Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Numerical data were checked for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and summarized as medians (and interquartile ranges; IQR). For the median length of stay (LOS), the Mann–Whitney U-test and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare differences between two and more than two independent variables, respectively. Simple and multiple logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify the independent predictors of hospitalization, such as, age groups, gender, co-living with an HCW, smoking status, presence of any health condition, number of comorbidities, specific chronic health conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, CKD, heart disease, and history of admission within the past year; the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. The significance level was at α = 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Of the 1152 patients initially selected from the database, only 613 (53.21%) consented to participate and were interviewed. These patients were divided into two groups: a hospitalized group (324/613, 52.85%) and a nonhospitalized group (289/613, 47.1%) (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of the patients.

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing patient recruitment.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the COVID-19 Patients

| Characteristics | Total N = 613 | Hospitalized n = 324 | Nonhospitalized n = 289 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| 60–69 | 351 (57.3%) | 157 (48.5%) | 194 (67.1%) | <0.001 |

| 70–79 | 180 (29.4%) | 110 (34.0%) | 70 (24.2%) | |

| 80–89 | 62 (10.1%) | 44 (13.6%) | 18 (6.2%) | |

| ≥90 | 20 (3.3%) | 13 (4.0%) | 7 (2.4%) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 300 (48.9%) | 144 (44.4%) | 156 (54.0%) | 0.018 |

| Female | 313 (51.1%) | 180 (55.6%) | 133 (46.0%) | |

| Co-living with HCW | ||||

| Yes | 130 (21.2%) | 58 (17.9%) | 72 (24.9%) | 0.034 |

| No | 483 (78.7%) | 266 (82.1%) | 217 (75.1%) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Former smoker | 94 (15.3%) | 59 (18.2%) | 35 (12.1%) | 0.056 |

| Current smoker | 21 (3.4%) | 7 (2.2%) | 14 (4.8%) | |

| Never smoker | 495 (80.8%) | 257 (79.3%) | 238 (82.4%) | |

| Missing | 3 (0.5%) | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.7%) | |

| Region of residence | ||||

| Riyadh | 209 (34.1%) | 99 (30.6%) | 110 (38.1%) | 0.139 |

| Eastern region | 141 (23.0%) | 66 (20.4%) | 74 (25.6%) | |

| Makkah | 160 (26.1) | 94 (29.0) | 66 (22.8) | |

| Madinah | 41 (6.7%) | 24 (7.4%) | 17 (5.9%) | |

| Al-Qassim | 12 (2.0%) | 8 (2.5%) | 4 (1.4%) | |

| Aseer | 16 (2.61) | 11 (3.4) | 5 (1.73) | |

| Najran | 8 (1.3%) | 6 (1.9%) | 2 (0.7%) | |

| Al-Baha | 5 (0.8%) | 4 (1.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Tabuk | 4 (0.7%) | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.7%) | |

| Hail | 4 (0.7%) | 3 (0.9%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Northern borders | 1 (0.2%) | - | 1 (0.3%) | |

Most of the patients (531/613, 86.7%) were between 60 and 79 years of age. The proportion of patients aged ≥70 years was significantly higher in the hospitalized group than in the nonhospitalized group: 51.5% (167/324) vs 32.9% (95/289), P < 0.001. The proportion of female patients was significantly higher in the hospitalized group than in the nonhospitalized group (55.6% vs 46.0%, P = 0.018). Overall, 21% (130/613) of patients reported co-living with HCWs; the proportion was significantly lower in the hospitalized group than in the nonhospitalized group: 17.9% (58/324) vs 24.9% (72/289), P = 0.034.

Clinical Characteristics

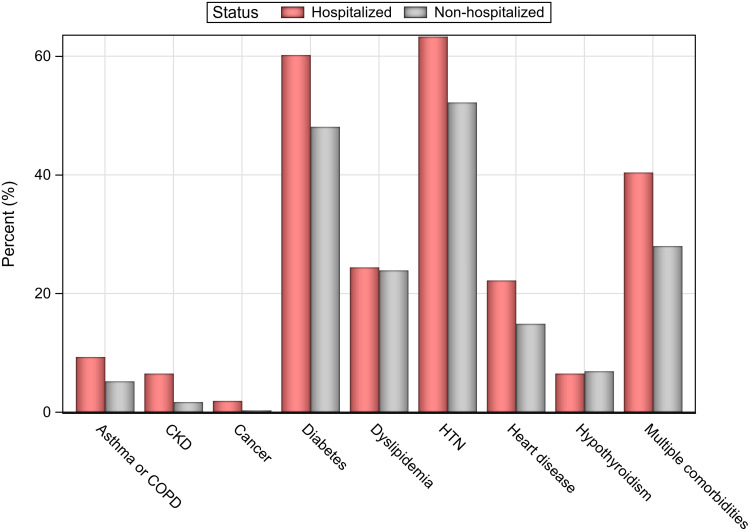

The majority of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 (270/324, 83.33%) were admitted to the hospital wards; only 54/324 (16.67%) patients were admitted to ICUs. Among the patients admitted to ICUs, the majority (45/54, 83.3%) were ≥65 years old. More than half of the patients admitted to ICUs (30/54, 55.6%) needed mechanical ventilation, and among these the majority (83.3%, 25/30) were ≥65 years. Table 2 lists the clinical characteristics of the patients. Comorbidities were significantly more common in hospitalized patients, with at least one comorbidity being present in 85.8% (278/324) of the patients in the hospitalized group vs 78.9% (228/289) of the patients in the nonhospitalized group (P = 0.024); moreover, a significantly larger proportion of hospitalized patients had more than one comorbidity: 40.4% of hospitalized patients vs 28% of nonhospitalized patients (P = 0.001). Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart disease, and CKD were all significantly more prevalent in hospitalized patients than in nonhospitalized patients (all P < 0.05; Figure 2). Only 13.5% (83/613) of patients reported receiving flu vaccination prior to COVID-19 infection; there was no significant difference between hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients. History of hospital admission within the past year was reported by 22.3% (137/613) of patients; the proportion was significantly higher in the hospitalized group than in the nonhospitalized group: 28.1% (91/324) vs 15.9% (46/289), P < 0.001.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of the Patients

| Characteristics | Total N = 613 | Hospitalized n = 324 | Nonhospitalized n = 289 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Any condition | 506 (82.5%) | 278 (85.8%) | 228 (78.9%) | 0.024 |

| More than one condition | 212 (34.6%) | 131 (40.4%) | 81 (28.0%) | 0.001 |

| Flu vaccination | ||||

| Yes | 83 (13.5%) | 40 (12.3%) | 43 (14.9%) | 0.537 |

| No | 439 (71.6%) | 238 (73.5%) | 201 (69.6%) | |

| Not sure | 91 (14.8%) | 46 (14.2%) | 45 (15.6%) | |

| Hospital admission within the past year | ||||

| Yes | 137 (22.3%) | 91 (28.1%) | 46 (15.9%) | <0.001 |

| No | 476 (77.7%) | 233 (71.9%) | 243 (84.1%) | |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Fever | 426 (69.5%) | 242 (74.7%) | 184 (63.7%) | 0.005 |

| Cough | 348 (56.8%) | 205 (63.3%) | 143 (49.5%) | 0.002 |

| Sore throat | 232 (37.8%) | 124 (38.3%) | 108 (37.4%) | 0.518 |

| Runny nose | 120 (19.6%) | 61 (18.8%) | 59 (20.4%) | 0.450 |

| Shortness of breath | 269 (43.9%) | 176 (54.3%) | 93 (32.2%) | <0.001 |

| Vomiting | 96 (15.7%) | 64 (19.8%) | 32 (11.1%) | 0.012 |

| Nausea | 146 (23.8%) | 88 (27.2%) | 58 (20.1%) | 0.065 |

| Dizziness | 189 (30.8%) | 123 (38.0%) | 66 (22.8%) | <0.001 |

| Headache | 211 (34.4%) | 103 (31.8%) | 108 (37.4%) | 0.147 |

| Loss of smell or taste | 272 (44.4%) | 137 (42.3%) | 135 (46.7%) | 0.007 |

| Change in taste | 28 (4.6%) | 14 (4.3%) | 14 (4.8%) | 0.757 |

| Mouth ulcers | 6 (1.0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 5 (1.7%) | 0.105 |

| Diarrhea | 205 (33.4%) | 121 (37.3%) | 84 (29.1%) | 0.056 |

| Tiredness or general fatigue | 478 (78.0%) | 276 (85.2%) | 202 (69.9%) | <0.001 |

| Weight loss | 145 (23.7%) | 83 (25.6%) | 62 (21.5%) | 0.226 |

| Weight gain | 5 (0.8%) | 3 (0.9%) | 2 (0.7%) | >0.999 |

| Eye redness/itching | 21 (3.4%) | 9 (2.8%) | 12 (4.2%) | 0.350 |

| Back pain | 101 (16.5%) | 52 (16.0%) | 49 (17.0%) | 0.763 |

| Leg pain | 71 (11.6%) | 39 (12.0%) | 32 (11.1%) | 0.710 |

| Joint pain | 158 (25.8%) | 79 (24.4%) | 79 (27.3%) | 0.404 |

| Abdominal pain | 50 (8.2%) | 31 (9.6%) | 19 (6.6%) | 0.176 |

| Muscle spasms | 2 (0.3%) | 2 (0.6%) | – | 0.501 |

| Swollen ankles or feet | 3 (0.5%) | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0.604 |

| Chills | 15 (2.4%) | 10 (3.1%) | 5 (1.7%) | 0.278 |

| Loss of appetite | 279 (45.5%) | 172 (53.1%) | 107 (37.0%) | <0.001 |

| Hemoptysis | 2 (0.3%) | 2 (0.6%) | – | 0.501 |

| Altered smell of urine | 3 (0.5%) | 2 (0.6%) | 1 (0.3%) | >0.999 |

| Dark urine discoloration | 4 (0.7%) | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.7%) | >0.999 |

| Difficulty urinating | 12 (2.0%) | 7 (2.2%) | 5 (1.7%) | 0.701 |

| Fainting | 5 (0.8%) | 4 (1.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0.377 |

| Itching | 5 (0.8%) | 2 (0.6%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0.671 |

| Rash | 3 (0.5%) | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.6%) | 0.604 |

| Skin ulcers | 2 (0.3%) | 2 (0.6%) | – | 0.501 |

| Numbness or tingling | 20 (3.3%) | 10 (3.1%) | 10 (3.5%) | 0.795 |

| Presence of symptoms | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 50 (8.2%) | 17 (5.2%) | 33 (11.4%) | 0.005 |

| Symptomatic | 563 (91.8%) | 307 (94.8%) | 256 (88.6%) | |

Figure 2.

Rates of chronic health conditions among hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients.

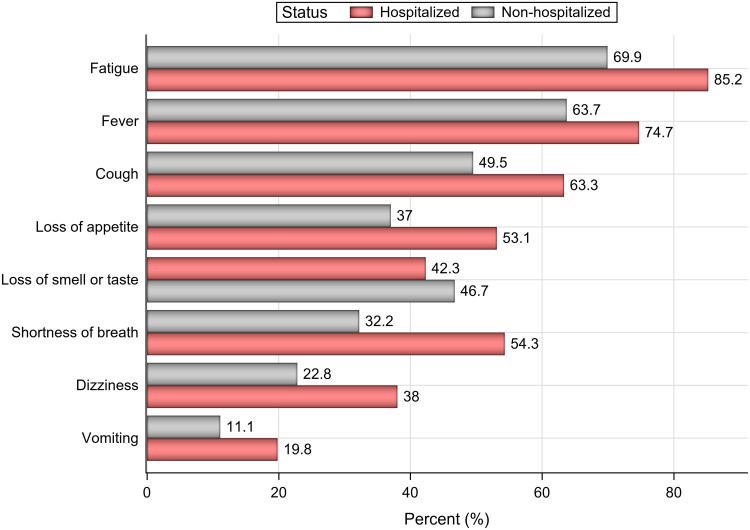

COVID-19-related symptoms (such as fatigue, fever, cough, loss of appetite, shortness of breath, dizziness, and vomiting) were significantly more common in the hospitalized group than in the nonhospitalized group (P < 0.05; Figure 3); however, loss of smell/taste was more common among nonhospitalized patients (P = 0.007).

Figure 3.

Rates of commonly reported symptoms in hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients.

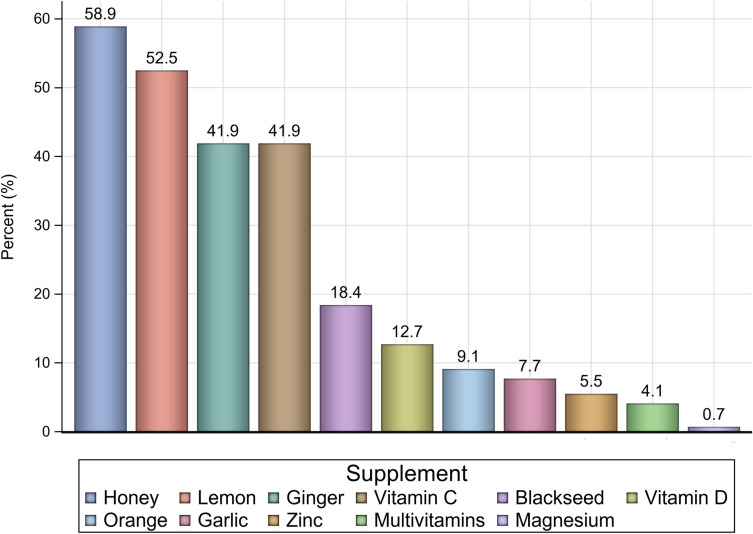

In the hospitalized group, median length of hospital stay was 10 days (IQR, 11.5 days). The median length of stay was significantly longer for those with heart disease than for those without heart disease (13.5 days vs 10.5 days, P = 0.04), and for patients with CKD than for those without CKD (19 days vs 10 days, P = 0.01). Table 3 shows the median length of hospital stay across some patients’ characteristics. Herbal and food supplements were largely utilized among patients in the study. Honey, ginger, lemon, and vitamin C were used by at least 40% of the patients, as shown in Figure 4.

Table 3.

Total Length of Stay in the Hospital (Ward/ICU) Stratified by Some Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristics | Median (IQR) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 10 (11.5) | – |

| Age (years) | ||

| <65 | 10 (12) | 0.979 |

| ≥65 | 11 (11) | |

| Age-group | ||

| 60–69 | 10 (12.5) | 0.957 |

| 70–79 | 12 (10.0) | |

| 80–89 | 10 (9.0) | |

| ≥90 | 11 (9.5) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 10 (14.0) | 0.784 |

| Female | 11 (9.0) | |

| Co-living with HCW | ||

| Yes | 13 (12.0) | 0.164 |

| No | 10 (10.0) | |

| Comorbidity | ||

| Yes | 11 (13.0) | 0.157 |

| No | 9.0 (7.0) | |

| More than one comorbidity | ||

| Yes | 12.5 (12.0) | 0.087 |

| No | 10 (11.25) | |

| Diabetes | ||

| Yes | 11 (13) | 0.545 |

| No | 10 (8.0) | |

| Hypertension | ||

| Yes | 11 (12.0) | 0.540 |

| No | 10 (8.5) | |

| Heart disease | ||

| Yes | 13.5 (10.5) | 0.044 |

| No | 10 (12.0) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | ||

| Yes | 19 (17.5) | 0.010 |

| No | 10 (10) | |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; HCW, healthcare worker.

Figure 4.

The rates of herbal and food supplements’ utilization among the study sample.

Predictors of Hospitalization

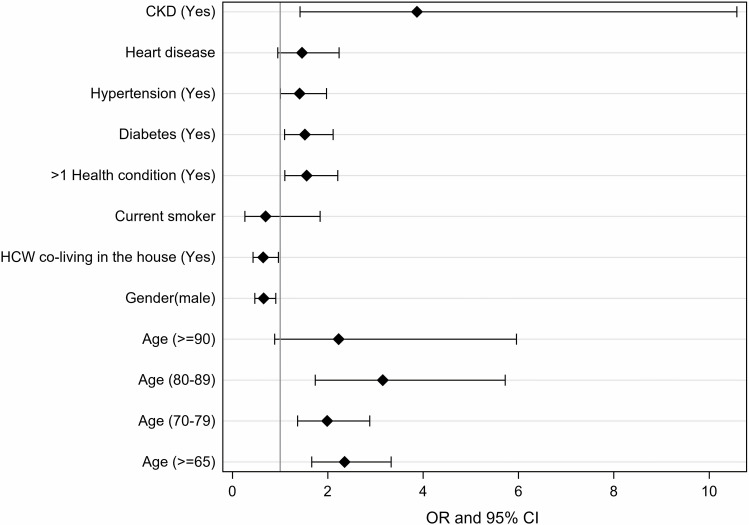

Table 4 and Figure 5 show how different sociodemographic and clinical variables were associated with higher risk of hospitalization. Patients aged ≥65 years had more than two times higher risk of hospitalization than patients aged <65 years (OR = 2.35, 95% CI: 1.66–3.33, P < 0.001). Male patients had 34.7% lower risk of hospitalization than female patients (OR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.47–0.90, P = 0.01). Patients living with HCWs had 35.5% lower risk of hospitalization than patients not living with HCWs (OR = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.43–0.96, P = 0.03). Patients with more than one comorbidity had 55.8% higher risk of hospitalization than patients with only one or no comorbidity (OR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.09–2.20, P = 0.01). Patients with diabetes had 52.1% higher risk of hospitalization than patients without diabetes (OR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.09–2.11, P = 0.01). Patients with hypertension had 40.9% higher risk of hospitalization than patients without hypertension (OR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.007–1.97, P = 0.04). Patients with CKD had almost four times higher risk of hospitalization than patients without CKD (OR = 3.87, 95% CI: 1.41–10.58, P = 0.008). Patients with history of admission to hospital in the past year had 69.2% higher risk of hospitalization than patients without history of hospital admission within the past year (OR = 1.69, 95% CI: 1.11–2.55, P = 0.013). Patients with heart disease had 63.5% higher risk of hospitalization than patients without heart disease, but it was not statistically significant (OR = 1.45, 95% CI: 0.95–2.23, P = 0.08).

Table 4.

Unadjusted Odds Ratios (ORs) for the Risk of Hospitalization of Selected Patients’ Characteristics

| Characteristics | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Age (≥65 years) | 2.287 (1.623–3.221) | <0.001 |

| Age-group | ||

| 60–69 (ref) | - | - |

| 70–79 | 1.922 (1.332–2.772) | <0.001 |

| 80–89 | 2.989 (1.661–5.380 | <0.001 |

| ≥90 | 2.271 (0.885–5.380) | 0.088 |

| Sex (male) | 0.682 (0.496–0.938) | 0.019 |

| Co-living with HCW (Yes) | 0.657 (0.445–0.970) | 0.035 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never (ref) | - | - |

| Current smoker | 0.463 (0.184–1.167) | 0.103 |

| Former smoker | 0.463 (0.042–5.140) | 0.531 |

| Comorbidity (Yes) | 1.617 (1.061–2.463) | 0.025 |

| More than one comorbidity (Yes) | 1.464 (1.156–1.855) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus (Yes) | 1.631 (1.184–2.248) | 0.003 |

| Hypertension (Yes) | 1.574 (1.140–2.175) | 0.006 |

| Heart disease (Yes) | 1.635 (1.078–2.479) | 0.021 |

| Chronic kidney disease (Yes) | 3.937 (1.465–10.580) | 0.007 |

| Hospital admission within the past year (Yes) | 2.063 (1.386–3.070) | <0.001 |

Abbreviation: HCW, healthcare worker.

Figure 5.

Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of some patients’ characteristics.

Discussion

This study aimed to identify the factors associated with risk of hospitalization among adults aged 60 years and above in Saudi Arabia. We found age ≥65 years to be an independent predictor of hospitalization. This is consistent with several previous studies, including a recently published study from Denmark that found older age to be a significant predictor of hospitalization and mortality after controlling for sex and a number of comorbidities.14 Consistent with earlier studies, we found that the presence of multiple comorbidities — which is common in this age-group — increased the risk of hospitalization.5,14–16,19,20

Specific health conditions that were associated with higher risk of hospitalization included diabetes, hypertension, and CKD. A recently published meta-analysis of 47 studies (with a total sample size of 13,268 COVID-19 patients) found diabetes to be significantly associated with a higher risk of severe disease and mortality.23 This is very concerning, given the high prevalence of diabetes in the Saudi population in general and in older adults in particular, where the prevalence is as high as 20%.24 Although hypertension has been found to be associated with worse clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients, no study has so far shown hypertension to be an independent risk factor for severe COVID-19 illness or mortality.25 In the present study, we found that hypertension and CKD were independent predictors of hospitalization and longer hospital stay. Multiple previous studies have reported significantly increased risk of mortality among COVID-19 patients with compromised renal function.14,26 Williamson et al analyzed a large database in England and found that patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate <30/min/1.73 m2 and those on dialysis had significantly higher risk of morality.26 This is alarming because there is a high prevalence of CKD among older adults in Saudi Arabia.27 Cardiovascular disease (including coronary artery disease and heart failure) has been previously shown to be associated with higher risk of hospitalization and mortality in patients with COVID-19.14,26 In the present study, however, although heart disease was associated with high risk of hospitalization and prolonged hospital stay, it was not an independent predictor of these outcomes; the failure to demonstrate a significant association may have been because of the relatively small number of patients with heart disease in our sample.14,26 In a previous study, severe asthma (ie, with history of recent use of oral corticosteroid) was a risk factor for mortality in COVID-19 patients.26 In our study, bronchial asthma was not significantly associated with risk of hospitalization; however, we did not stratify patients based on history of recent use of oral corticosteroids.

Interestingly, in the present study, male sex was associated with lower risk of hospitalization. While most previous studies have found that male patients have significantly higher risk of hospitalization, ICU admission, and death,14,26,28–30 a recently published study from Saudi Arabia found no significant difference in mortality between male and female patients hospitalized for COVID-19.31 Meanwhile, it should be emphasized that the lower risk of hospitalization that we found among older adult males does not necessarily mean lower mortality, as this study did not follow-up patients post-discharge.

Another interesting finding was the lower risk of hospitalization among patients co-living with HCWs. This is likely due to the better, and more informed care provided to family members by HCWs.32 In our sample, history of hospital admission within the past year was an independent predictor of hospitalization for COVID-19. This is in line with a previous Danish study on a large cohort of COVID-19 patients.14 Current smoking was not associated with risk of hospitalization, which is in accordance with the Williamson et al study.26

COVID-19-related symptoms such as fatigue, fever, cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, vomiting, dizziness, and loss of appetite were common in all patients, though they were relatively more common among hospitalized patients. This finding is consistent with two previously published studies from Saudi Arabia.28,33

This study has many limitations. First, the study only included older adults who survived COVID-19 infection since complete data were not available on patients who died. Second, the study findings are subject to information and documentation bias since the data were retrieved from an electronic database or via telephone interviews.34 Moreover, the cognitive strain on older adults asked multiple questions over the telephone may have resulted in an acquiescence bias.35 Third, nonresponse bias cannot be excluded, since not all selected patients agreed to participate in the study, which can influence the results significantly.36 Finally, this was a cross-sectional study and so no causal relationship between any of the examined clinical/sociodemographic variables and the risk of hospitalization can be established.

Conclusion

The factors associated with high risk of hospitalization for COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia include older age; presence of multiple comorbidities; presence of diabetes, hypertension, or CKD; female sex; and hospital admission within the previous year. Further well-designed studies are necessary to confirm our findings. Future studies should examine the factors associated with higher risk of hospitalization and mortality among elderly patients with COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia using more robust study designs, which will help in efficient allocation of health resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the help and support of data collectors at the Saudi Ministry of Health.

The first and third authors contributed equally to this study and are both corresponding authors for this paper.

Abbreviations

CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease-19; HESN, Health Electronic Surveillance Network; HCW, healthcare worker; ICD-10, international classification of diseases-10; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; MOH, Ministry of Health; OR, odds ratio; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

Data Sharing Statement

Study data are de-identified and can be made available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 24October, 2020.

- 2.WHO. Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020. accessed 25October 2020.

- 3.Liu K, Chen Y, Lin R, Han K. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: a comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J Infect. 2020;80(6):e14–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song J, Hu W, Yu Y, et al. A Comparison of clinical characteristics and outcomes in elderly and younger patients with COVID-19. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e925047. doi: 10.12659/MSM.925047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li P, Chen L, Liu Z, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of elderly patients with COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;97:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niu S, Tian S, Lou J, et al. Clinical characteristics of older patients infected with COVID-19: a descriptive study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;89:104058. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104058) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):934–943. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou L, Dai l, zhang y, et al. clinical characteristics and risk factors for disease severity and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in wuhan, china. Front Med. 2020;7:532. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendes A, Serratrice C, Herrmann FR, et al. Predictors of in-hospital mortality in older patients with COVID-19: the COVIDAge study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(11):1546–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bialek S, Boundy E, Bowen V, COVID TC, Team R. Severe Outcomes Among Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) — united States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343–346. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reilev M, Kristensen KB, Pottegard A, et al. Characteristics and predictors of hospitalization and death in the first 11 122 cases with a positive RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 in Denmark: a nationwide cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49(5):1468–1481. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tehrani S, Killander A, Astrand P, Jakobsson J, Gille-Johnson P. Risk factors for death in adult COVID-19 patients: frailty predicts fatal outcome in older patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmieri L, Vanacore N, Donfrancesco C, et al. Clinical characteristics of hospitalized individuals dying with COVID-19 by age group in Italy. J Gerontology. 2020;75(9):1796–1800. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MOH News M.O.H. Reports First Case of Coronavirus Infection; 2020. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News-2020-03-02-002.aspx. Accessed 5April 2020.

- 18.COVID-19 Daily Updates. Saudi Arabia: ministry of Health; 2020. Available from: https://covid19.moh.gov.sa/. accessed 14June 2020.

- 19.Guo T, Shen Q, Guo W, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Elderly Patients with COVID-19 in Hunan Province, China: a Multicenter, Retrospective Study. Gerontology. 2020;29:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medetalibeyoglu A, Senkal N, Kose M, et al. Older adults hospitalized with Covid-19: clinical characteristics and early outcomes from a single center in Istanbul, Turkey. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khoja AT, Aljawadi MH, Al-Shammari SA, et al. The health of Saudi older adults; results from the Saudi National Survey for elderly health (SNSEH) 2006–2015. Saudi Pharm J. 2018;26(2):292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2017.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ICD-10 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. World Health Organization; 2019. Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en. Accessed 5September 2020.

- 23.Varikasuvu SR, Dutt N, Thangappazham B, Varshney S. Diabetes and COVID-19: a pooled analysis related to disease severity and mortality. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021;15(1):24–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2020.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whiting DR, Guariguata L, Weil C, Shaw J. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94(3):311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang S, Wang J, Liu F, et al. COVID-19 patients with hypertension have more severe disease: a multicenter retrospective observational study. Hypertension Res. 2020;1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alsuwaida AO, Farag YMK, Al Sayyari AA, et al. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (SEEK-Saudi investigators) - a pilot study. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant. 2010;21(6):1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan AA, Althunayyan SM, Alsofayan YM, Alotaibi RN, Mubarak AM. Risk factors associated with worse outcomes in COVID-19: a retrospective study in Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26(11):1371–1380. doi: 10.26719/emhj.20.130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gebhard C, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Neuhauser HK, Morgan R, Klein SL. Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe. Biol Sex Differ. 2020;11(1):1–3. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00304-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mallapaty S. The coronavirus is most deadly if you are older and male-new data reveal the risks. Nature. 2020;16–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan AA, AlRuthia Y, Balkhi B, et al. Survival and estimation of direct medical costs of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the kingdom of saudi arabia (Short Title: COVID-19 Survival and Cost in Saudi Arabia). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7458. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bianchetti A, Bellelli G, Guerini F, et al. Improving the care of older patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32(9):1883–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alsofayan Y, Althunayyan S, Khan A, Hakawi A, Assiri A. Clinical characteristic of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: a national retrospective study. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(7):920–925. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matt V, Matthew H. The retrospective chart review: important methodological considerations. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2013;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bowling A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J Public Health (Bangkok). 2005;27(3):281–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheung KL, Peter M, Smit C, de Vries H, Pieterse ME. The impact of non-response bias due to sampling in public health studies: a comparison of voluntary versus mandatory recruitment in a Dutch national survey on adolescent health. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]