Abstract

Background

During infectious disease outbreaks, the weakest communities are more vulnerable to infection and its deleterious effects. In Israel, the Arab and Ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities have unique demographic and cultural characteristics that place them at higher risk of infection.

Objective

To examine socioeconomic and ethnic differences in rates of COVID-19 testing, confirmed cases and deaths, and to analyze patterns of transmission in ethnically diverse communities.

Methods

A cross-sectional ecologic study design was used. Consecutive data on rates of COVID-19 diagnostic testing, lab-confirmed cases, and deaths collected from March 31 through May 1, 2020, in 174 localities across Israel (84% of the population) were analyzed by socioeconomic ranking and ethnicity.

Results

Tests were performed on 331,594 individuals (4.29% of the total population). Of those, 14,865 individuals (4.48%) were positive for COVID-19 and 203 died (1.37% of confirmed cases). Testing rate was 26% higher in the lowest SE category compared with the highest. The risk of testing positive was 2.16 times higher in the lowest socioeconomic category, compared with the highest. The proportion of confirmed cases was 4.96 times higher in the Jewish compared with the Arab population.

The rate of confirmed cases in 2 Ultra-Orthodox localities increased relatively early and quickly. Other Jewish and Arab localities showed consistently low rates of confirmed COVID-19 cases, regardless of socioeconomic ranking.

Conclusions

Culturally different communities reacted differently to the COVID-19 outbreak and to government measures, resulting in different outcomes. Socioeconomic and ethnic variables cannot fully explain communities’ reaction to the pandemic. Our findings stress the need for a culturally adapted approach for dealing with health crises.

Keywords: COVID-19, Ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) Jews, Arabs, Socioeconomic, Diagnostic test, Confirmed case, Death

Background

Cultural, behavioral, structural, and societal differences, including socioeconomic status (SES), health-seeking behaviors, and intergenerational cohabitation may affect COVID-19 spread [1]. More deprived and less affluent communities are more vulnerable to the disease and its deleterious effects due to a higher prevalence of comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension [2]. Such populations are also characterized by low health literacy and less access to information channels, causing them to miss or misinterpret health authorities’ instructions and warnings [3]. Furthermore, employment in essential professions or manual jobs less amenable to remote working, and reliance on public transport, further increases exposure [4].

Ethnic and racial disparities related to COVID-19 infection and mortality have been reported: British intensive care data showed that rates of confirmed cases among Asian and Black patients were almost double that of the proportion of these ethnic minorities in the UK [5]. In the USA, African Americans are over-represented both in the number of cases and in the number of deaths, comprising, for example, 52% of COVID-19 cases and 69% of COVID-19 deaths in Chicago, despite accounting for just 30% of the population [6].

In addition, differences in SES also affect COVID-19 mortality. In England and Wales, mortality rates have been twice as high in the most deprived areas as compared with the most affluent [7].

Israel is a multiethnic multicultural country characterized by wide social disparities and a high proportion of people living in poverty. Poverty is disproportionally prevalent among two population groups: the Arab and the Ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) Jewish populations.

The Israeli Arab population accounts for 21% of the total of 9.1 million inhabitants. This population is generally younger, with 43% younger than 18 (median age, 22 years), compared with 28% in the Jewish population (median age, 34) [8]. In addition, compared with the Jewish population, household net income is lower among the Israeli Arab population, fewer people hold an academic degree and participate in the labor force. The average number of household family members is 4.9, compared with 3.4 in Jewish families. Crowded living (more than 2 members per room) characterizes 26.5% of the Israeli Arab families, compared with 4.6% of Jewish families [9]. There is a higher prevalence of smoking-related chronic lower respiratory disease among Arab men, while both genders have higher prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, compared with the Jewish population [9].

The Ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) live by Jewish law and tradition [10]. Accounting for 12% of the Israeli population, this group is younger, has larger families, and is characterized by residential crowding—26% have more than 2 people per room, compared with 2% of other non-orthodox Israeli Jews [11–13]. They reside mainly in Ultra-Orthodox-only cities or in separate neighborhoods in mixed cities. Employment rates in this population are low, and household incomes are the lowest among all Israeli population groups.

Despite the known direct correlation between SES and health, most of the Ultra-Orthodox population report very good health status and have a relatively high life expectancy [14], attributed to their high social capital, defined as “the information, trust, and norms of reciprocity inhering in one’s social networks” [15].

The first patient with a confirmed COVID-19 infection arrived in Israel from the “Diamond Princess” quarantined cruise ship on February 21, 2020. On February 27, the first community-acquired case was diagnosed, and on March 20, the first COVID-19-related death was documented. Until May 1, 16,101 cases and 203 deaths have been documented nationally.

Mask wearing in public became obligatory on April 12, but was hardly enforced during the first weeks. The first wave of COVID-19 spread climaxed in early April with nearly 10,000 active cases and 500–700 additional confirmed cases a day. Viral spread subsequently began to slow down. Starting April 19, lockdown restrictions were gradually relaxed.

During the first wave of the pandemic, most localities adopted a combination of stay-at-home and social distancing rules, encouraging people to avoid going outside (except for certain defined essential activities) and to maintain a safe distance from people outside their own household. The results showed an unprecedented behavioral change across the country. However, this compliance came at tremendous social and economic costs, as many people lost their jobs, education was severely disrupted, and ordinary life was completely upended.

Following the call to identify and address the toll of the pandemic on diverse populations, including racial and ethnic minorities and economically disadvantaged groups [16,17], we aimed to examine the socioeconomic and ethnic differences in relation to rates of COVID-19 testing, confirmed cases and deaths, and to analyze patterns of transmission in diverse communities across Israel.

Methods

Data Sources

Data were obtained from the Israeli Ministry of Health’s (MOH) publicly available open COVID-19 database (https://data.gov.il/dataset/covid-19), which includes information on 174 medium or large urban communities/localities (5000 inhabitants or more) and is updated daily.

The database contains the number of COVID-19 diagnostic tests performed, the number of confirmed cases (i.e., those that tested positive by real-time quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assay), and deaths in Israel. Notably, the incidence rate is conditional on the rate of testing (i.e., test positivity rate).We linked each locality in the MOH database to its socioeconomic (SE) cluster. SE clusters are homogenous units on a scale of 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) that are determined by the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) according to population demography, education, employment, and standard of living. SE clusters are further grouped by the CBS into four categories based on common characteristics with 1 as the lowest SE ranking (clusters 1–3), 2 (clusters 4 and 5), 3 (clusters 6 and 7), and 4 as the highest SE ranking (clusters 8–10). Categories 1, 2, 3, and 4 account for 28.5%, 18.3%, 27.2%, and 25.9%, respectively, of the Israeli population.

Data Analysis

Our analysis included MOH data from March 31 to May 1, 2020 (31 consecutive days).

MOH data on tests performed, confirmed COVID-19 cases, and case fatality rate (CFR, defined as the ratio between confirmed deaths and confirmed cases) were analyzed by SE categories, ethnicity (Arab vs .Jewish), and religiosity (Ultra-Orthodox Jewish vs. non-Ultra-Orthodox Jewish). After April 26, 2020, mortality data and ethnicity were no longer reported at the localities level in the MOH database; therefore after this date, deaths reported in each hospital were allocated to the SE category of the hospital’s catchment area.

For the comparison between the Jewish and Arab populations, only localities in which more than 90% of the population is Jewish or Arab were included. Mixed cities were excluded because of the impossibility to accurately identify ethnicity in these cities.

The outcome and the explanatory variables are measured at an aggregate level.

Descriptive and frequency statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB version 2020a and Python 3.6.5 software.

Results

The 174 communities included in the analysis comprise 7.72 million inhabitants, or 84.0% of the population of Israel. The largest category (51 localities, accounting for 42.9% of the study population) belongs to the lower-mid SE category (SE category 2).

Table 1 presents data on COVID-19 testing rate, lab-confirmed cases, and mortality rate by SE category. As of May 1, 2020, COVID-19 tests had been performed on 331,594 individuals (4.3% of the total population). Of those, 14,865 individuals (4.48%) were positive for the infection and 203 deaths were reported (1.37% of confirmed cases).

Table 1.

COVID-19 tests, confirmed cases, and mortality, by SE category

| Category 1 | Category 2 | Category 3 | Category 4 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 1,667,076 | 3,312,699 | 1,502,970 | 1,237,666 | 7,720,411 |

|

Tested % of population |

84,282 (5.05%) |

139,197 (4.2%) |

58,712 (3.91%) |

49,403 (3.99%) |

331,594 (4.29%) |

|

Confirmed % of tested |

5263 (6.24%) |

6718 (4.83%) |

1453 (2.47%) |

1431 (2.89%) |

14,865 (4.48%) |

|

Deaths % of confirmed |

12 (0.23%) |

108 (1.61%) |

50 (3.44%) |

33 (2.31%) |

203 (1.37%) |

| Death per 100K population | 0.72 | 3.26 | 3.27 | 2.67 | 2.63 |

Category 1 low status, category 2 moderate status, category 3 high status, category 4 very high status

SE socioeconomic status

*Only low and low-mid SE clusters (1-4 out of 10) were included in the analysis

The analysis showed that the proportion of confirmed cases gradually decreased from SE categories 1 through 3, with a slight increase in category 4 (the highest of 4 categories). The lowest SE category (1) had the highest percentage of population tested for COVID-19 (5.05%)—1.26 times higher, compared with the highest SE category (in which 3.99% of the population was tested). The risk of testing positive for COVID-19 was 2.16 times higher in the lowest SE category, compared with the highest one (6.24% vs. 2.89%).

COVID-19-related deaths documented during the analysis period (n = 203) represent an overall mortality rate of 2.63 deaths per 100K inhabitants. The death rates were unevenly distributed among the SE rankings, with SE category 3 demonstrating the highest number of deaths per 100K population and SE category 1 the lowest (3.27 vs. 0.72). Categories 2 and 3 showed similar rates—3.26 and 3.27 deaths per 100K population, respectively.

CFR gradually increased from categories 1 (0.23%) through 3 (3.44%), with a decrease in category 4 (2.31%, Table 1).

Arab localities comprise the majority (80%) of the lowest SE clusters (1–3) and 40% of cluster 4. Their proportion in clusters 5 and 6 is less than 10%, and they are not represented at all in clusters 6–10 [18]. Therefore, only homogenous localities from clusters 1–4 were included in the ethnicity analysis. Of the total Israeli Arab population of 1.92 million, 1.09 million (56.9%) were included in the analysis.

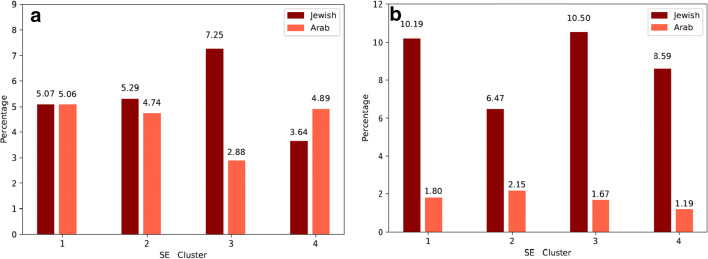

Overall, there were 538 cases per 100K in the Jewish population, and 78 confirmed cases per 100K in the Arab population. The proportion of confirmed cases among those tested was 4.96 times higher in Jewish compared with Arab localities. Figure 1 compares the Jewish and Arab populations at the low and mid-low SE clusters (1–4 out of 10). In SE clusters 2 and 3, 1.12 and 2.52 times more tests were performed, respectively, in the Jewish, compared with the Arab population, while in SE cluster 4, 1.38 more tests were performed in the Arab compared with the Jewish population. In all SE clusters, the rate of confirmed cases was greater among the Jewish localities compared with the Arab ones.

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 tests performed and confirmed cases by ethnicity and SE cluster. a Percent of population tested according to SE cluster. b Percent of confirmed cases from those tested according to SE cluster. Only low and low-mid SE clusters (1–4 out of 10) were included in the analysis. SES socioeconomic status

To understand the epidemiology of COVID-19 by ethnicity and religiosity, the proportion of confirmed COVID-19 cases was analyzed in six localities representing Arab, Ultra-Orthodox, and non-Ultra-Orthodox Jewish populations each associated with a different SE category (Table 2). Bene-Beraq and El’ad are two predomenantly Ultra-Orthodox cities with 195,298 and 47,600 inhabitants, respectively, which belong to the lowest SE category (1). As shown in Fig. 2, the rate of confirmed COVID-19 cases in these 2 cities increased relatively early and quickly (reflected by a steep slope). In comparison, Herzliya, Beer Sheba (both predominantly Jewish non-Ultra-Orthodox cities), and the predominantly Arab city, Nazareth, showed consistently low rates of confirmed COVID-19 cases during the entire period. Interestingly, Herzliya, which belongs to the highest SE category, showed higher rates of confirmed cases compared with Nazareth and Beer Sheba which are associated with SE categories 1 and 2, respectively. Hura, a Bedouin Arab locality, which is among the poorest communities in Israel (SE cluster 1 out of 10), demonstrated a dramatic, rather late increase in confirmed cases, reaching the level of Bene Beraq, with its highest percentage of confirmed cases within a period of just 7 days.

Table 2.

Proportion of COVID-19 tests and confirmed cases in selected Israeli localities from diverse SE categories*, cultural and religious backgrounds

| Bene Beraq | Beer Sheba | Herzliya | Nazareth | El'ad | Hura | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE Category | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Population | 195,298 | 196,755 | 90,900 | 78,252 | 47,600 | 16,983 |

|

Tested (% of population) |

24,685 (12·6%) |

8,277 (4·2%) |

3,508 (3·86%) |

1,288 (1·64%) |

4,069 (8·55%) |

769 (4·53%) |

|

Confirmed (% of tested) |

2,831 (11·4%) |

173 (2·09%) |

102 (2·9%) |

20 (1·55%) |

383 (9·41%) |

82 (10·66%) |

| Confirmed % of population | 1·45% | 0·09% | 0·11% | 0·03% | 0·80% | 0·48% |

*SE category: (1) = clusters 1,2,3; (2) = clusters 4-5; (4) = clusters 8,9,10

Fig. 2.

Proportion of confirmed COVID-19 cases in selected Israeli localities: Trends over a 31-day period

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate the relation between socioeconomic and ethnic determinants on the epidemiology of COVID-19 in Israel.

Our analysis shows that more tests per population were performed among the most deprived populations compared with the least deprived groups. This might reflect the early awareness of the MOH to communities with high prevalence of confirmed cases, particularly the Ultra-Orthodox communities. As a result, epidemiological investigations and testing were directed to those communities.

A striking finding is the increasing rate of confirmed cases with decreasing SE categories, with rates more than double in the lowest category compared with the higher ones. A similar social gradient in health has been documented in New York City (NYC), where the proportion of positive tests was greater in poor neighborhoods, as well as in neighborhoods with larger households or a predominantly Black population [19].

CFRs were lower in low SE categories compared with higher SE categories. Due to the small number of COVID-19-related deaths in Israel, mortality data should be interpreted with caution. CFR in the Israeli population that was analyzed here (7.7 million) was 1.37%, compared with 4.2%, 5.8%, and 13.7% in Germany, the USA, and Italy, respectively [20]. Possible explanations for the relatively low mortality rate observed in Israel include the country’s good healthcare system with universal coverage of care [21], its younger population compared with other OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) members, which may be less affected by COVID-19 [22], and early establishment of national measures. These measures included stopping incoming flights and requirement of 14-day quarantine of those who arrived from abroad, social distancing measures, with an emphasis on self-isolation of the elderly, a national state of emergency, and almost complete lockdown between March 19 and May 3, 2020. In addition, frequent military operations and emergency situations have prepared the Israeli healthcare system for crises, contributing to its ability to effectively care for severely ill patients.

As reported for other countries [23], it is possible that the number of COVID-19-related deaths in Israel has been under-estimated due to deaths that occurred at home prior to a COVID-19 diagnosis. During the first weeks of the pandemic, all health maintenance organizations in Israel advised their members to shift to telehealth platforms as the main venue for communicating with their health providers, instead of visiting their clinics. Since both health literacy and digital literacy are lowest in the most deprived communities [24], they might be more vulnerable to disease deterioration. While all Israeli citizens have access to public healthcare, inequities do exist [2]. Chronic illnesses are more prevalent in ethnic minorities and lower SES groups, particularly in the Arab population, and access to healthcare is sometimes more difficult in more rural areas. Structural barriers to healthcare in Israel can include costs, transportation difficulties, or language barrier [25]. Furthermore, community physicians, hospital beds, and facilities are not equally distributed throughout the country [26]. However the possibility of major under-reporting of infection and death is unlikely. Moreover, during the study period, all-cause mortality, reported by the Israel Center for Disease Control, was within range of the multiannual average [27], supporting this assumption.

Experience gained in prior health crises as well as from emerging reports from the COVID-19 pandemic showed that ethnic minorities and deprived populations are more susceptible to being affected by the disease [5,6]. Therefore, it was expected that the Arab ethnic minority in Israel, which is demographically characterized by being less affluent, having larger families, greater population density, residence in geographical peripheries, and a higher prevalence of comorbidities, would demonstrate higher infection rates and more severe disease course compared with the general population. However, only moderate differences in testing were noted between the Jewish and Arab populations (5.6% vs. 4.1%), which might be explained by less access to healthcare services in a population of which more than half reside in geographical peripheries [18] and fear of stigma and social, cultural, and economic consequences of testing “positive.” To help overcome these obstacles, political representatives urged the MOH to increase testing among the Arab population.

The strikingly low rate of lab-confirmed cases among the Arab population—almost five times lower compared with the Jewish population—may be attributed to the following: (a) obedience of the population, which is predominantly (85%) Muslim and religious, to the official religious instructions (named “Fatwa” in Arabic) conveyed by the religious leaders (“Mufti”). The religious leaders instructed the population to follow the instructions of the MOH and relevant official bodies, to postpone or shorten cultural events, to perform funeral services with minimal participation, and to avoid any kind of gathering [28]. All mosques were closed, instructing people to pray at home instead, especially during Ramadan, which began on April 23. (b) Arab men and women are employed at high rates in the Israeli healthcare system as physicians, nurses, and pharmacists—the most prominent occupations of the COVID-19 crisis—contributing to the feeling that the Israeli Arab citizens are full partners in this struggle [29, 30]. This high rate of knowledgeable people could possibly contribute to maintaining social distancing and other measures to fight the disease. (c) Traditionally, Arab families take care of the elderly at home and do not place them in residential care facilities, reflecting a culture that is more tolerant toward older adults [31,32]. This may have been a protective factor, as a third of all COVID-19 deaths in Israel during the analysis period were documented among elderly living in residential homes. (d) Finally, the political alliance of the main Arab-majority political parties in Israel—the Joint List—showed involvement by focusing on issues relating to all vulnerable sectors [29]. Their voice was heard among their voters and among policy makers.

Despite what seems to be an optimistic situation among the Israeli Arabs, one must consider the possibilities of clusters of undiagnosed infections, particularly in remote, segregated communities that are isolated geographically. Lower access to healthcare services might also explain late testing, and consequently a relatively late explosion of cases. The last week of April and the first days of May saw a surge of confirmed cases in some Arab localities, such as the Bedouin locality of Hura (Fig. 2).

The presentation of COVID-19 in the Ultra-Orthodox community, which bears socioeconomic similarities to the Arab community, was completely different, manifesting early with very high infection rates, as shown in the two predominantly Ultra-Orthodox localities: Bene Beraq and El’ad (Fig. 2). The community participates only minimally in secular affairs and opposes features of Israeli public life, such as the national government and modern law. Typically, some sectors of the ultra-Orthodox take instruction from their own religious leaders over governmental instructions. This translates into segregation from the rest of Israeli society [33] The emergency orders and restrictions issued by the government hit the most fundamental components of their identity—group studies of the bible (Torah), prayer in a quorum of 10 men, and ritual baths. These traditions were stronger than the biblical rule that everything should be put aside for the sake of saving lives. The instructions for strict social distancing were rejected because they were not endorsed by the community’s own leaders. Moreover, the senior leader of this community loudly opposed the instructions to close schools and told his followers to continue group learning. These Ultra-Orthodox leaders stopped opposing the government’s instructions only after massive infection spread was seen in their communities. To curb the spread of infection and flatten the escalating curve, the Israeli government imposed hermetic quarantine on some Ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods.

Our analysis has several limitations: First, data were analyzed by locality, rather than by individuals. This ecologic approach misses possible differences in the composition and disease patterns within localities. We were not able to adjust for confounders such as age or employment and perform advanced statistical analysis [34]. Second, small towns and settlements, comprising less than 5000 residents, were not included in the MOH database and therefore were not analyzed. No data exist to evaluate this possible bias on disease measures. However, we do know that larger communities are usually more central (or less peripheral). In Israel, communities in the geographic periphery are characterized by lower perceived health, higher prevalence of cigarette smoking, and higher prevalence of overweight and obesity [35]. These risk factors might contribute to more severe COVID-19 disease.

Third, data on localities comprising mixed Arab-Jewish ethnicities were excluded from the analysis, because it was not possible to distinguish between the ethnicity of individuals in the database. Arab communities in large mixed cities might present with different disease patterns. Last, after April 26, 2020, mortality data and ethnicity were no longer reported at the localities level in the MOH database; however, due to intensive media coverage of fatalities, including the naming of most of those who died, we believe that large numbers of Arab deaths could have not escaped public awareness.

Our analysis shows that we should treat assumptions about ethnic minorities with caution as it is not always possible to predict how such communities would react in times of crisis. The Israeli Arab community mostly demonstrated responsible behavior, following governmental instruction that were mediated by the community’s religious leaders. Although the Ultra-Orthodox community did not abide by the government’s instructions because it regards its religious leaders’ instructions as more relevant, it is important not to stigmatize a community “en-bloc.” Such labeling of the whole community is unjust and counterproductive. Instead, the more cooperative leaders of the community should be strengthened so that their voice may be heard.

Conclusions

Some lessons learnt from our analysis might be of value for the international audience. First, researchers and policymakers should adopt a “tailor-made” perspective and measures to deal with culturally different communities during epidemics. Specifically, the cases presented here, which showed that the reactions to the crisis of two culturally different communities from similar socioeconomic backgrounds resulted in completely different outcomes, emphasize the need for designing a culturally adapted approach to curb viral spread. Second, our data suggest that socioeconomic and ethnic variables cannot fully forecast and explain communities’ reaction to a crisis. The case of Nazareth, an Arab city with a deprived population that had lower infection rates compared with Herzliya, which is among the least deprived Jewish cities, is one example. Last, but not least, the collaboration of community leaders—whether religious or political representatives of the community—is essential for helping to change the course of the infection in their communities.

Abbreviations

- MOH

Ministry of Health

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- SES

Socioeconomic status

Author Contribution

MS: contribution to the study design, data analyses and interpretation, critical drafting of the whole article, final approval of the submitted article, accountability for all aspect of the work. TS and VM: contribution to the study design, data analyses and interpretation, accountability for all aspect of the work. OM: contribution to the study design, data interpretation, critical drafting of the whole article, final approval of the submitted article, accountability for all aspect of the work. RWM: contribution to the study design, data interpretation, writing of the introduction, discussion and conclusion section, critical drafting of the whole article, final approval of the submitted article, accountability for all aspect of the work.

All authors have read and agreed to the content of the manuscript and confirmed the ICMJE.org authorship criteria.

Data availability

All data can available in https://govextra.gov.il/ministry-of-health/corona/corona-virus-en/

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All data retrieved from the MOH open data source.

Consent for Publication

All authors declare the consent for publication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mor Saban, Email: mors@gertner.health.gov.il, Email: morsab1608@gmail.com.

Vicki Myers, Email: vickimg@gertner.health.gov.il.

Tal Shachar, Email: tshachar1@gmail.com.

Oren Miron, Email: orenmir@post.bgu.ac.il.

Rachel R Wilf-Miron, Email: rachelwm@gertner.health.gov.il.

References

- 1.Pareek M, Bangash MN, Pareek N, et al. Ethnicity and COVID-19: an urgent public health research priority. thelancet.com. 2020. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30922-3. Accessed September 24 , 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Muhsen K, Green MS, Soskolne V, Neumark Y. Inequalities in non-communicable diseases between the major population groups in Israel: achievements and challenges. Lancet. 2017;389(10088):2531–2541. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.A P. Low health literacy prevents equal access to care. Lancet. 2000. https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(05)73297-9.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, Sia IG, Wieland ML. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2020; https://academic.oup.com/cid/article-abstract/doi/10.1093/cid/ciaa815/5860249. Accessed January 28, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Rimmer A. Covid-19: disproportionate impact on ethnic minority healthcare workers will be explored by government. BMJ. 2020;369:m1562. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323(19):1891–1892. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Office for National Statistics. Deaths involving COVID-19 by local area and socioeconomic deprivation: deaths occurring between 1 March and 31 July 2020.; 2020. https://backup.ons.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/08/Deaths-involving-COVID-19-by-local-area-and-socioeconomic-deprivation-deaths-occurring-between-1-March-and-31-.pdf. Accessed December 31, 2020.

- 8.Bleikh H. Poverty and inequality in Israel: trends and decompositions.; 2016. http://taubcenter.org.il/wp-content/files_mf/povertyandinequality.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2020.

- 9.TAUB CENTER For Social Policy Studies In Israel. The singer series: state of the nation report 2017.; 2017.

- 10.Chernichovsky D, Kaplan A, Regev E, … JS-C for SPS in, 2017 U. Long-Term Care in Israel: Funding and Organization Issues.; 2017.

- 11.L MG& C. 2019 Statistical Report on Ultra-Orthodox Society in Israel: Highlights - The Israel Democracy Institute.; 2019. https://en.idi.org.il/articles/29348. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- 12.Schnall E. Multicultural Counseling and the Orthodox Jew. J Couns Dev. 2006;84(3):276–282. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2006.tb00406.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malach G CL. The Yearbook of Ultra-Orthodox Society in Israel.; 2018. https://en.idi.org.il/publications/25651. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- 14.Chernichovsky D, Bisharat B, Bowers L, Brill A SC. The Health of the Arab Israeli Population. Jerusalem Taub Cent Soc Policy Stud Isr. 2017.

- 15.society MW-T. U. Social capital and economic development: toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. JSTOR. 1998:1998 https://www.jstor.org/stable/657866. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- 16.Haynes N, Cooper LA, Albert MA. At the heart of the matter: unmasking and addressing the toll of COVID-19 on diverse populations. Circulation. 2020;142(2):105–107. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laurencin CT, Mcclinton A. The COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action to identify and address racial and ethnic disparities. (n.d.). doi:10.1007/s40615-020-00756-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Dov Chernichovsky BBLB, Aviv Brill and CS. The Health of the Arab Israeli Population.; 2017. www.taubcenter.org.il. Accessed May 25, 2020.

- 19.Borjas G. Demographic determinants of testing incidence and COVID-19 infections in New York city neighborhoods. Cambridge, MA; 2020. doi:10.3386/w26952

- 20.Calderon-Margalit Weissam Abu-Ahmed Arie Ben-Yehuda Ehud Horwitz Michal Krieger Orly Manor Ora Paltiel Yiska Weisband Yael Wolff-Sagy R. National Program for Quality Indicators in Community Healthcare in Israel.; 2019. [PubMed]

- 21.OECD reviews of health care quality: Israel 2012. OECD; 2012. doi:10.1787/9789264029941-en

- 22.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):846–848. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaye B, Fanidi A, Jouven X. Denominator matters in estimating COVID-19 mortality rates. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3500. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armenta A, Serrano A, Cabrera M, Conte R. The new digital divide: the confluence of broadband penetration, sustainable development, technology adoption and community participation. Inf Technol Dev. 2012;18(4):345–353. doi: 10.1080/02681102.2011.625925. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daeem R, Mansbach-Kleinfeld I, Farbstein I, et al. Barriers to help-seeking in Israeli Arab minority adolescents with mental health problems: results from the Galilee study. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2019;8(1). 10.1186/s13584-019-0315-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Averbuch E AS. Disparities in Distribution of Infrastructure, Personnel and Hospital Beds.; 2020.

- 27.Ministry of Health. Monitoring of COVID-19 in Israel: report for the week that ends in 2 May 2020.; 2020.

- 28.The house of Fatwa and Islamic Research in the Plasetinian interior. 2020. https://www.facebook.com/DarEftaa48/. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- 29.Sheleg Y. The Coronavirus and Israel’s Ultra-Orthodox and Arab Communities. Jerusalem: The Israeli Democracy Institute. The Israeli Democracy Institute.

- 30.Chernichovsky D, Bisharat B, Bowers L, Brill A, Sharony C. The Health of the Arab Israeli Population A Chapter from The State of the Nation. n.d..

- 31.Bergman YS, Bodner E, Cohen FS. Cross-cultural ageism: ageism and attitudes toward aging among Jews and Arabs in Israel. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;25:6–15. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212001548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suleiman K, Walter-Ginzburg A. A nursing home in Arab-Israeli society: targeting utilization in a changing social and economic environment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(1):152–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sivan ECK. Israeli Haredim: integration Without Assimilation? The Van Leer Jerusalem Institute and Hakibbutz Hameuchad; 2003.

- 34.Clark WAV, Avery KL. The effects of data aggregation in statistical analysis. Geogr Anal. 2010;8(4):428–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-4632.1976.tb00549.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaps between center and periphery selected data from the society in Israel Report.; 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data can available in https://govextra.gov.il/ministry-of-health/corona/corona-virus-en/