Abstract

Introduction

Pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) are at risk of adverse outcomes, including gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, and preterm delivery. This study was undertaken to determine if apolipoprotein (apo) levels differed between pregnant women with and without GDM and if they were associated with adverse pregnancy outcome.

Research design and methods

Pregnant women (46 women with GDM and 26 women without diabetes (ND)) in their second trimester were enrolled in the study. Plasma apos were measured and correlated to demographic, biochemical, and pregnancy outcome data.

Results

apoA2, apoC1, apoC3 and apoE were lower in women with GDM compared with control women (p=0.0019, p=0.0031, p=0.0002 and p=0.015, respectively). apoA1, apoB, apoD, apoH, and apoJ levels did not differ between control women and women with GDM. Pearson bivariate analysis revealed significant correlations between gestational age at delivery and apoA2 for women with GDM and control women, and between apoA2 and apoC3 concentrations and C reactive protein (CRP) as a measure of inflammation for the whole group.

Conclusions

Apoproteins apoA2, apoC1, apoC3 and apoE are decreased in women with GDM and may have a role in inflammation, as apoA2 and C3 correlated with CRP. The fact that apoA2 correlated with gestational age at delivery in both control women and women with GDM raises the hypothesis that apoA2 may be used as a biomarker of premature delivery, and this warrants further investigation.

Keywords: apolipoproteins, pregnancy, diabetes, gestational, diabetes mellitus, type 2

Significance of this study.

What is already known about this subject?

Pregnant women with gestational diabetes are at risk of adverse outcomes, including hypertension, pre-eclampsia, and pre-term delivery, and apolipoproteins (apos) may be mechanistically involved in the pathophysiology of these adverse outcomes.

What are the new findings?

apoA2, apoC1, apoC3 and apoE levels were reduced in women with gestational diabetes, while apoA2 correlated with gestational age at delivery in pregnant women with, as well as without, gestational diabetes.

apoA2 correlated with gestational age at delivery in pregnant women with, as well as without, gestational diabetes and therefore may be useful as a biomarker of premature delivery.

How might these results change the focus of research or clinical practice?

Decreased levels of apoA2, apoC1, apoC3 and apoE may promote inflammation in gestational diabetes, while apoA2 may serve as a useful biomarker of premature delivery.

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is the most frequent pregnancy-associated metabolic disorder occurring in ~7% of all pregnancies1 and is usually detected towards the end of the second trimester.2 GDM is associated with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, including pre-eclampsia, macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycemia and hyperbilirubinemia, during the perinatal period.3 Women with a history of GDM are at increased risk of subsequent development of cardiovascular disease (CVD)4 and have greater than seven fold increased risk of the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D).1 5

Pregnancy is accompanied by increased insulin resistance, a physiological, metabolic adaptation to accommodate the nutritional demands of the fetus.6 Insulin resistance is typically compensated for by an adaptive increase in glucose-stimulated insulin release,7 together with an adaptive increase in beta-cell mass.8 The insulin requirements in overweight or obese pregnant women are amplified, and when demand outstrips secretory capacity, gestational diabetes ensues.9 The underlying mechanisms driving insulin resistance in pregnancy are complex and are not fully understood; however, placental hormones, obesity, inactivity, poor diet, and genetic/epigenetic factors are known contributing factors.10

Risk factors for GDM include older maternal age, multiparity, ethnicity, family history of diabetes, weight gain during pregnancy11 and pregravid overweight or obesity.12 13 The identification of biochemical markers that might reliably predict the development of GDM and GDM-related maternal or fetal complications would have practical diagnostic and therapeutic utility. In addition, such markers may assist in understanding the biochemical pathways in GDM that are distinct from, or common to, those with T2D.

Apolipoproteins (apos), through their amphipathic properties, enable the transport of hydrophobic lipids in aqueous body fluids.14 To accomplish this, apos, together with other amphipathic molecules such as phospholipids, surround the hydrophobic lipid molecules to create water-soluble lipoproteins. Besides solubilizing lipids and stabilizing lipoprotein structure, apos also contribute to lipoprotein uptake and clearance through interaction with lipoprotein receptors and lipid transport proteins and act as enzyme cofactors during lipoprotein metabolism.15

The lipid and apo changes that occur during pregnancy have long been recognized16 and enable a continuous supply of nutrients to reach the fetus.6 Most notable is the elevation of serum triglycerides, and, to a lesser extent, cholesterol17 (apoA1 and apoB) also increases with the progression of pregnancy.16 18 Disturbances in lipid profiles in pregnancy, however, increase CVD risk and result in adverse maternal and fetal outcomes19 20 such as pre-eclampsia,20 21 GDM,22 23 fetal growth restriction (FGR) and premature delivery.19 24

While apos have emerged as screening tools for cardiovascular risk assessment and have proven to be even more predictive biomarkers than serum lipids,25 26 they also have potential as biomarkers for adverse pregnancy outcomes.27 28 In the setting of FGR, apoB100 levels were reduced in maternal serum.28 A high level of apoA1 in maternal serum was associated with early miscarriage,29 and an increase in apoA2 has been associated with gestational age.30 Elevations of apoE, apoB:apoA1 ratio and triglycerides are associated with a higher risk of pre-eclampsia,31 which is associated with increased cardiovascular risk in later life.32 33 However, in pregnant women, serum apoA1 was shown not to be associated with insulin resistance or GDM.34 More recently, postpartum apo levels, specifically elevated apoC3 and the ratios of apoC3:apoA1, apoC3:apoA2, apoC3:apoC2, and apoC3:apoE, have been shown to represent independent risk factors for the development of T2D in women who have GDM.35

This study aimed to determine whether serum apo levels in a cohort of second trimester pregnant women differed in those with and without GDM, and if they were associated with inflammation and/or adverse pregnancy outcome.

Research design and methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study in 68 pregnant women (42 women with GDM and 26 women without diabetes (ND)) who were recruited during their second trimester at the antenatal clinic at the Women’s Wellness and Research Center of Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar, from 2016 to 2017. Demographics, anthropometrics, and medical history data were collected, including age, ethnicity, socioeconomic background, vital signs, height, weight, menstrual cycle, the period of infertility, medications, complications, comorbidities, and family medical history. All pregnant women were screened in the first antenatal care visit using fasting blood glucose (FBG). If the FBG at the first visit was <5.1 mmol/L (92 mg/dL), 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was performed at 24 weeks' gestation. The WHO criteria (FBG≥5.1 mmol/L (92 mg/dL), 1-hour post-OGTT≥10.0 mmol/L (180 mg/dL) or 2-hour post-OGTT≥8.5 mmol/L (153 mg/dL)) were used to diagnose GDM. Patients with GDM were enrolled as soon as the diagnosis was confirmed (within 1 week of the OGTT and before 25 weeks’ gestation), when the blood sample was drawn. Patients with GDM were started on a nutritional therapy diet for 2 weeks to achieve an FBG of ≤5.3 mmol/L (95 mg/dL) and the 2-hour postprandial glucose being ≤6.8 mmol/L (120 mg/dL) in ≥80% of the readings. If more than 20% of the readings were above target, then metformin therapy was implemented and increased incrementally to a maximum of 2 g/day, followed by insulin supplementation when glucose targets were not achieved.

Collection and analysis of blood samples

Blood samples were collected and immediately processed and stored frozen at −80°C pending analysis, as previously reported.36 “The thyroid-stimulating hormone, insulin and C reactive protein (CRP) were measured in the Chemistry Laboratory at Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar, and measured by an immunometric assay with fluorescence detection on the DPC Immulite 2000 analyzer using the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. Total cholesterol, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels were measured enzymatically using a Synchron LX20 analyzer (Beckman-Coulter, High Wycombe, UK). Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was calculated using the Friedewald equation. Serum insulin was assayed using a competitive chemiluminescent immunoassay performed on the manufacturer’s DPC Immulite 2000 analyzer (Euro/DPC, Llanberis, UK). The analytical sensitivity of the insulin assay was 2μU/mL; the coefficient of variation was 6%; and there was no stated cross-reactivity with proinsulin. Plasma glucose was measured using a Synchron LX 20 analyzer (Beckman-Coulter), using the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. The coefficient of variation for the assay was 1.2% at a mean glucose value of 5.3 mmol/L during the study period. Pregnancy outcomes of gestational age at delivery, birth weight, maternal weight, blood pressure, and fetal outcome were recorded and collated with the apo profile for all subjects who participated in the study.

Apolipoproteins assay protocol

apos were measured from EDTA plasma samples. apo levels were determined using the Bio-Plex Pro Human Apolipoprotein 10-Plex Assay Panel (Cat # 12003081; Bio-Rad, Hertfordshire, UK). This is a sensitive magnetic bead-based multiplexing protein panel that measures quantitative levels of these proteins simultaneously in plasma. Apoprotein levels in the samples were quantitated by the 5PL (five parameters) logistic regression algorithms that come with the Bioplex manager six software, which were used for quantification of samples in reference to standards. The measurements were run on Bioplex-200 (Bio-Rad) instrument. The plasma samples were diluted 50 000 times to get the apoprotein levels within the range of the standard curve. The sensitivity, working range and assay precision for different apos were as follows: apoA1, 140–0.093 ng/mL, intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) 6% and interassay CV 9%; apoA2, 30–0.045 ng/mL, intra-assay CV 5% and interassay CV 6%; apoB, 300–0.38 ng/mL, intra-assay CV 10% and interassay CV 15%; apoC1, 17–0.024 ng/mL, intra-assay CV 2% and interassay CV 5%; apoC3, 33–0.029 ng/mL, intra-assay CV 4% and interassay CV 5%; apoD, 25–0.070 ng/mL, intra-assay CV 4% and interassay CV 6%; apoE, 12–0.019 ng/mL, intra-assay CV 3% and interassay CV 12%; apoH, 210–0.34 ng/mL, intra-assay CV 3% and inter-assay CV 4%; apoJ, 170–0.14 ng/mL, intra-assay CV 7% and interassay CV 7%; and CRP, 12–0.013 ng/mL, intra-assay CV 4% and interassay CV 6%.

Statistical analysis

Based on a study on apo levels that showed significant differences of apoA2 and apoC levels in metabolic syndrome,37 a population sample size of 38 patients was calculated, giving 80% power to detect a difference with a two-sided alpha error of 0.05 (nQuery, Statsol, USA). Descriptive statistics and means±SDs were calculated for all continuous variables in the study. Student’s t-test was used to compare mean differences between control and GDM groups. Pearson rank correlation was performed to understand the associations between apos and demographic variables. All statistical analysis was done using statistical analysis SPSS V.26 software. A statistical significance level (p value) of <0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Demographics

General characteristics of participants

Seventy-two young (31.5±5.5 years) overweight/obese (32.2±7.1 kg/m2) pregnant women were included in this study (46 women with GDM and 26 control women ND). The women with GDM were older than the control women (32.8±5.4 vs 29.1±4.9 years, women with GDM vs control women, p<0.01). BMI was matched in both groups (33.2±6.6 vs 30.2±7.8 kg/m2, women with GDM vs control women, p=not significant (ns)). Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were comparable in both groups. GDM was diagnosed at 20.5±5.1 weeks’ gestation. By definition, fasting glucose was elevated in the GDM group (5.4±0.9 vs 4.6±0.2 mmol/L, women with GDM vs control women, p=0.029). HbA1c did not differ significantly between groups (5.2±0.4 vs 5.1%±0.4%, women with GDM vs control women, p=ns), reflecting the recent onset of elevated plasma glucose in the GDM women. Biochemical profile, most notably, lipids (cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL and LDL), did not differ between groups, neither was there a difference in gestational age at delivery between groups (38.2±1.5 vs 38.4±2.1 weeks, women with GDM vs control women, p=ns) (table 1). Out of the 72 pregnancies, 70 resulted in live births (two fetuses from the GDM group died in utero). Of note, the high rate of fetal demise reported in this study is entirely due to the sample size being small and a consequence of rare events, such as severe congenital abnormalities. From the same population, we have previously reported on two cohorts of women with gestational diabetes; in the first, the rate of fetal demise was 0.25%,12 and in the second larger cohort, the rate of fetal demise was 0.1%.38

Table 1.

Demographic data of the women with GDM (n=46) and control (n=26) women

| Control women | Women with GDM | t-Test | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P value | |

| Maternal characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 29.1 | 4.9 | 32.8 | 5.4 | 0.006 |

| Prepregnancy weight (kg) | 57.2 | 13.2 | 62.5 | 11.9 | 0.42 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 30.2 | 7.8 | 33.2 | 6.6 | 0.09 |

| SBP baseline (mm Hg) | 109 | 11 | 112 | 12 | 0.41 |

| DBP baseline (mm Hg) | 65 | 8 | 63 | 7 | 0.17 |

| Second-term SBP (mm/Hg) | 120 | 11 | 120 | 10 | 0.96 |

| second-term DBP (mm Hg) | 72 | 7 | 72 | 9 | 0.75 |

| Maternal weight at delivery (kg) | 82 | 16.2 | 84.9 | 14 | 0.44 |

| Biochemical variables | |||||

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 4.6 | 0.2 | 5.4 | 0.9 | 0.03 |

| Insulin result (IU/L) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.14 |

| Glycated hemoglobin (%) | 5.1 | 0.4 | 5.2 | 0.4 | 0.24 |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (mU/L) | 2.5 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 0.8 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/l) | 12.9 | 10 | 17.4 | 11.7 | 0.11 |

| Aspartate transaminase (U/L) | 16.6 | 5.8 | 21.1 | 16.9 | 0.2 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5 | 1.1 | 4.9 | 1.1 | 0.65 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.41 |

| High-density lipoprotein (mmol/L) | 1.5 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.15 |

| Low-density lipoprotein (mmol/L) | 3 | 0.9 | 3 | 0.9 | 0.95 |

| Newborn characteristics | |||||

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 38.4 | 2.1 | 38.2 | 1.5 | 0.65 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3061 | 509 | 3037 | 596 | 0.875 |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Apolipoproteins

apoA2 was higher in control women compared with women with GDM (268.7±39.4 vs 241.0±30.5 µg/mL, control women vs women with GDM, p=0.002). Likewise, apoC1, apoC3 and apoE were higher in control women compared with women with GDM (apoC1: 300.7±50.6 vs 260.3±53.8 µg/mL, control women vs women with GDM, p=0.003; apoC3: 77.5±28.7 vs 56.5±14.6 µg/mL, control women vs women with GDM, p=0.0002; apoE: 18.6±7.0 vs 15.2±4.2 µg/mL, control women vs women with GDM, p=0.015). The CRP level was higher in the GDM group (117±93 vs 57±52 µg/mL, women with GDM vs control women, p=0.003). apoA1, apoB, apoD, apoH and apoJ levels did not differ between control women and women with GDM (table 2).

Table 2.

apo levels in women with GDM and control women

| Control women | Women with GDM | t-Test | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P value | |

| apoA1 (µg/mL) | 1838.0 | 449.7 | 1704.0 | 289.9 | 0.14 |

| apoA2 (µg/mL) | 268.7 | 39.4 | 241.0 | 30.5 | 0.002 |

| apoB (µg/mL) | 1213.4 | 364.6 | 1352.5 | 341.7 | 0.12 |

| apoC1 (µg/mL) | 300.7 | 50.6 | 260.3 | 53.8 | 0.003 |

| apoC3 (µg/mL) | 77.5 | 28.7 | 56.5 | 14.6 | 0.0002 |

| apoD (µg/mL) | 45.4 | 26.4 | 44.5 | 14.8 | 0.86 |

| apoE (µg/mL) | 18.6 | 7.0 | 15.2 | 4.2 | 0.02 |

| apoH (µg/mL) | 583.8 | 306.5 | 620.5 | 336.1 | 0.65 |

| apoJ (µg/mL) | 157.3 | 102.7 | 183.9 | 117.3 | 0.34 |

| CRP (µg/mL) | 57.3 | 51.9 | 117.1 | 93.0 | 0.003 |

apo, apolipoprotein; CRP, C reactive potein; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus.

Because the maternal age and Body Mass Index (BMI) of the women with GDM and the control group were not comparable, we performed a linear regression analysis after adjusting for age and BMI as confounding factors. The analysis showed that apoA2 (p=0.019), apoC1 (p=0.005), apoC3 (p<0.0001) and apoE (p=0.042) still remained significantly different between the women with GDM and the control group, suggesting that age and BMI did not impact the levels of these proteins in our study subjects.

For the combined group (control women and women with GDM inclusive), we used Pearson bivariate analysis to examine for correlation between apoprotein levels and demographic, clinical and biochemical data. A positive significant correlation was found between apoA2 and gestational age delivery for the whole group (r=0.390, p=0.001; table 3) that was also observed individually for both women with GDM (r=0.323, p<0.04) and for control women (r=0.46, p<0.02; data not shown). For the whole group, apoC3 correlated with the gestational age at GDM diagnosis (r=0.330, p=0.006). Significant negative correlations were observed between CRP levels with apoA2 (r=−0.268, p=0.027) and apoC3 (r=−0.247, p=0.042) (table 3) for the whole group, but CRP did not correlate with either apoA2 or apoC3 in women with GDM or in control women individually.

Table 3.

Pearson correlations of apoA2, apoC1, apoC3 and apoE with demographic, biochemical data from combined cohort (control women and women with GDM)

| apoA2 | apoC1 | apoC3 | apoE | CRP | ||||||

| r | P value | r | P value | r | P value | r | P value | r | P value | |

| BMI | −0.192 | 0.117 | −0.053 | 0.666 | 0.134 | 0.278 | −0.043 | 0.728 | 0.123 | 0.318 |

| SBP baseline (mm Hg) | −0.088 | 0.474 | −0.028 | 0.818 | 0.074 | 0.550 | −0.021 | 0.865 | 0.029 | 0.813 |

| DBP baseline (mm Hg) | 0.174 | 0.156 | 0.010 | 0.937 | −0.073 | 0.552 | −0.119 | 0.334 | −0.052 | 0.671 |

| HOMA-IR | −0.204 | 0.239 | 0.013 | 0.940 | −0.008 | 0.964 | 0.095 | 0.586 | 0.025 | 0.887 |

| Gestational age at GDM diagnosis (weeks) | −0.081 | 0.512 | 0.132 | 0.281 | 0.330* | 0.006 | 0.109 | 0.375 | 0.115 | 0.349 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 0.100 | 0.539 | 0.003 | 0.984 | 0.086 | 0.598 | 0.016 | 0.920 | 0.072 | 0.659 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | −0.175 | 0.280 | −0.219 | 0.168 | 0.029 | 0.861 | −0.192 | 0.236 | −0.037 | 0.822 |

| High-density lipoprotein (mmol/L) | 0.003 | 0.985 | 0.201 | 0.214 | 0.077 | 0.641 | 0.175 | 0.287 | 0.106 | 0.519 |

| Low-density lipoprotein (mmol/L) | 0.111 | 0.509 | −0.035 | 0.831 | 0.060 | 0.720 | 0.060 | 0.719 | 0.081 | 0.627 |

| CRP (mg/mL) | −0.268* | 0.027 | −0.056 | 0.649 | −0.247*† | 0.042 | −0.119 | 0.334 | 1.000 | |

| Second-term SBP (mm Hg) | −0.143 | 0.256 | −0.025 | 0.842 | 0.019 | 0.882 | 0.135 | 0.285 | −0.230 | 0.066 |

| Second-term DBP (mm Hg) | −0.003 | 0.983 | 0.053 | 0.677 | 0.040 | 0.750 | −0.127 | 0.312 | 0.041 | 0.746 |

| Weight at delivery (kg) | −0.023 | 0.856 | −0.050 | 0.692 | 0.152 | 0.228 | 0.021 | 0.869 | 0.088 | 0.486 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 0.390* | 0.001 | −0.058 | 0.645 | −0.002 | 0.986 | 0.013 | 0.917 | −0.078 | 0.537 |

| Baby weight (g) | 0.134 | 0.300 | 0.019 | 0.886 | 0.067 | 0.603 | 0.093 | 0.474 | 0.043 | 0.742 |

| apoA1 (mg/mL) | 0.264*† | 0.030 | 0.536* | 0.000 | 0.217 | 0.075 | 0.219 | 0.073 | 0.094 | 0.444 |

| apoA2 (mg/mL) | 1.000 | 0.319* | 0.008 | 0.574* | 0.000 | 0.497* | 0.000 | −0.268*† | 0.027 | |

| apoB (mg/mL) | −0.092 | 0.456 | 0.346* | 0.004 | −0.218 | 0.075 | 0.139 | 0.258 | 0.399* | 0.001 |

| apoC1 (mg/mL) | 0.319* | 0.008 | 1.000 | 0.353* | 0.003 | 0.562* | 0.000 | −0.056 | 0.649 | |

| apoC3 (mg/mL) | 0.574* | 0.000 | 0.353* | 0.003 | 1.000 | 0.714* | 0.000 | −0.247*† | 0.042 | |

| apoD (mg/mL) | −0.189 | 0.123 | 0.221 | 0.070 | −0.496* | 0.000 | −0.313* | 0.009 | 0.236 | 0.053 |

| apoE (mg/mL) | 0.497* | 0.000 | 0.562* | 0.000 | 0.714* | 0.000 | 1.000 | −0.119 | 0.334 | |

| apoH (mg/mL) | −0.290*† | 0.016 | 0.073 | 0.552 | −0.382* | 0.001 | −0.203 | 0.097 | 0.379* | 0.001 |

| apoJ (mg/mL) | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.068 | 0.582 | −0.108 | 0.378 | −0.100 | 0.415 | 0.199 | 0.104 |

*Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

†Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed).

apo, apolipoprotein; BMI, Body Mass Index; CRP, C reactive protein; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

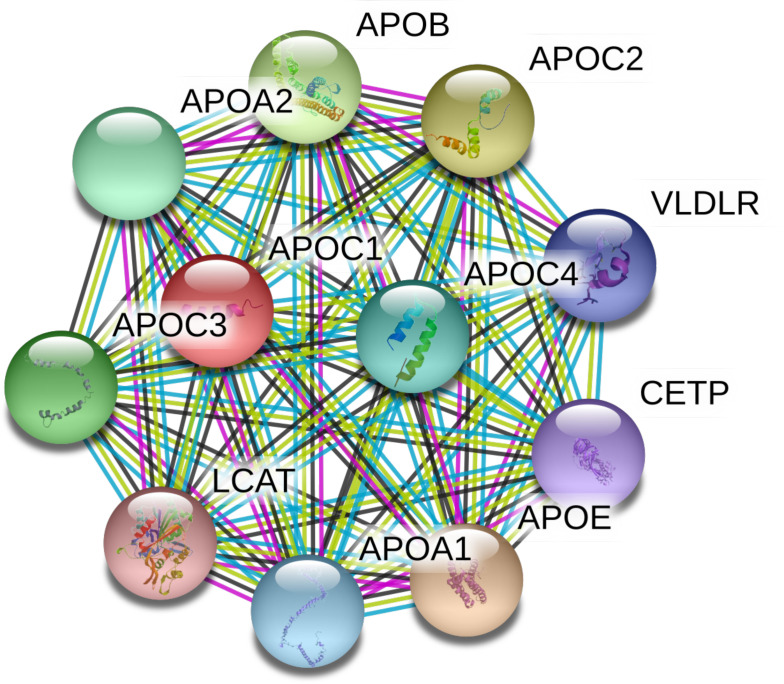

Several significant correlations were found between several apos, which reflect their coordinate regulation and physiological role in lipid metabolism (table 3). The close association between the different apos can be seen in the STRING analysis shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Search tool for retrieval of interacting genes (STRING) analysis (https://stringdb.org/) of human apoC1 protein–protein interaction network. apoC1 interacts with apoA2, apoC3 and apoE, all of which were found to differ between GDM and control women. STRING analysis illustrates the closest partners, based on evidence: magenta: experimentally determined; black: coexpression; blue: from curated databases. We acknowledge the use of the STRING technology that is freely available under a 'Creative commons by 4.0' license (https://string-db.org/cgi/access.pl?footer_active_subpage=licensing). APO, apolipoprotein; CETP, cholesteryl ester transfer protein; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; LCAT, lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase; VLDLR, very low-density lipoprotein receptor.

Discussion

The results of this study revealed lower apo levels for apoA2, apoC1, apoC3 and apoE in women with GDM versus control women and a significant correlation between apoA2 and gestational age was seen for both women with GDM and control women. apoA2 and apoC3 correlated significantly with CRP for the whole group.

Little is known about the role of apoA2 in pregnancy. apoA2 levels were unchanged in normal pregnancy complicated by pre-eclampsia39; however, modified apoA2 isoforms were reported to be significantly elevated in plasma from mothers who delivered prematurely relative to term controls,30 in accord with the findings reported for both the women with GDM and the control women here. This strong correlation seen between apoA2 in both control women and women with GDM raises the possibility that apoA2 may be a biomarker for premature delivery.

apoC1 is involved in lipid transport and metabolism.40 apoC1 is the only identified inhibitor of cholesteryl ester transfer protein,41 a function that is impaired in patients with dyslipidemia and coronary artery disease.42 Results of several studies, taken together, indicate that apoC1 plays a role in the development of diabetes.40 The role of apoC1 both in GDM and in pregnancy generally is unclear, though the results of this study suggest that its role in GDM needs clarification.

apoC3 regulates triglyceride-rich lipoprotein metabolism.43 apoC3 overexpression contributes to the development of atherosclerosis.44 In patients with T2D, raised apoC3 levels are associated with raised triglycerides and coronary artery calcification.45 apoC3 transgenic mice with abnormal lipid metabolism showed gestational hypertension in an animal model,46 and a raised plasma apoC3:apoC2 ratio was predictive of pre-eclampsia in later pregnancy,47 suggesting an important role in pregnancy, perhaps through inflammation,48 that would be in accord with its association with CRP seen here. apoC3 was found to correlate with gestational age at the time that GDM was diagnosed, suggesting that apoC3 levels may predict GDM. It was anticipated that apoC3 would be associated with blood pressure as noted previously,47 but that was not seen. There were no other correlations of the apos and pregnancy outcomes, and the negative results seen for apoA1, apoC2 and apoC3 were in accord with others who showed no correlation with gestational age.30

apoE is an important component of the reverse cholesterol transport pathway, essential for the uptake and clearance of atherogenic lipoproteins.49 apoE modifies inflammatory responses in foam cells and therefore plays an important role in atherosclerosis.50 apoE polymorphisms have been associated with recurrent pregnancy loss, though the role of apoE during gestation is unclear.51

The close association of the apoproteins with each other was seen in the results found here and exemplified by the STRING analysis that was performed and shown in figure 1. However, of particular interest in this study was the association of apoA2, apoC1, apoC3 and apoE that appear to be evolutionarily connected with apoA1, though no association with GDM was found in the latter.52

While most work on apos and inflammation has been done in the context of CVD,53 the negative correlation of apoA2 and apoC3 with CRP seen here suggests a more generalizable relationship between apos and inflammation. The association of apoC3 with CRP would indicate that inflammation may be driving the insulin resistance and hence the elevation in CRP in women with GDM; however, the converse could be the case as noted earlier,54 and the role of apoproteins in women with GDM requires clarification.

The study limitations include relatively small numbers of pregnant women in each group, which may have prevented the detection of differences between groups. As a cross-sectional study with serum analysis at a single time point during the second trimester, dynamic changes in apo levels throughout pregnancy could not be assessed. While likely generalizable, these findings should be confirmed in other ethnic populations.

In conclusion, apoA2, apoC1, apoC3 and apoE were lower in women with GDM and may have a role in inflammation, as both apoA2 and C3 correlated with CRP. apoC3 correlated with gestational age at GDM diagnosis, and apoA2 correlated with early gestational delivery in both women with GDM and control women, warranting its further investigation as a biomarker of premature delivery.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Qatar Metabolic Institute, Medical Research Center, Translational Research Institute, Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar. Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar for the support. Medical Research Center, Hamad Medical Corporation and Qatar National Library for the article processing fees.

Footnotes

MR and AEB contributed equally.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published. The Acknowledgements section has been updated.

Contributors: MR and IB performed the apolipoprotein measurements and contributed to the manuscript. MR, LA, ASMM, MAE, and ABA-S helped with data analysis and contributed to manuscript preparation. AEB researched the data and wrote the manuscript. SCH helped with statistical analysis. ASMM researched data and contributed to manuscript preparation. MB and SLA were involved in study design, sample collection and data analysis. MR, AEB, SLA and ABA-S designed the experiments, supervised progress, analyzed data, and revised and approved the final version of the article.

Funding: MR was supported by Qatar Metabolic Institute, and this study was supported by Qatar Metabolic Institute, Hamad Medical Corporation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All underlying data relating to this study will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

All patients gave written informed consent, and the conduct of the study was in accordance with International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Protocols were approved by institutional review boards of the Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar (15101/15) and Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar (15–00016).

References

- 1.Zhu Y, Zhang C. Prevalence of gestational diabetes and risk of progression to type 2 diabetes: a global perspective. Curr Diab Rep 2016;16:7. 10.1007/s11892-015-0699-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association . 2. classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016;39 Suppl 1:S13–22. 10.2337/dc16-S005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group, Metzger BE, Lowe LP, et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1991–2002. 10.1056/NEJMoa0707943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patti AM, Pafili K, Papanas N, et al. Metabolic disorders during pregnancy and postpartum cardiometabolic risk. Endocr Connect 2018;7:E1–4. 10.1530/EC-18-0130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pallardo F, Herranz L, Garcia-Ingelmo T, et al. Early postpartum metabolic assessment in women with prior gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 1999;22:1053–8. 10.2337/diacare.22.7.1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butte NF. Carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in pregnancy: normal compared with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;71:1256S–61. 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1256s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moyce B, Dolinsky V. Maternal β-cell adaptations in pregnancy and placental signalling: implications for gestational diabetes. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:3467. 10.3390/ijms19113467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler AE, Cao-Minh L, Galasso R, et al. Adaptive changes in pancreatic beta cell fractional area and beta cell turnover in human pregnancy. Diabetologia 2010;53:2167–76. 10.1007/s00125-010-1809-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchanan TA, Xiang AH. Gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 2005;115:485–91. 10.1172/JCI200524531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plows J, Stanley J, Baker P, et al. The pathophysiology of gestational diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:3342. 10.3390/ijms19113342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedderson MM, Gunderson EP, Ferrara A. Gestational weight gain and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:597–604. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cfce4f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bashir M, E Abdel-Rahman M, Aboulfotouh M, et al. Prevalence of newly detected diabetes in pregnancy in Qatar, using universal screening. PLoS One 2018;13:e0201247. 10.1371/journal.pone.0201247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon CG, Willett WC, Carey VJ, et al. A prospective study of pregravid determinants of gestational diabetes mellitus. JAMA 1997;278:1078–83. 10.1001/jama.1997.03550130052036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feingold KR, Grunfeld C, et al. Introduction to Lipids and Lipoproteins. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramasamy I. Recent advances in physiological lipoprotein metabolism. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014;52:1695–727. 10.1515/cclm-2013-0358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montes A, Walden CE, Knopp RH, et al. Physiologic and supraphysiologic increases in lipoprotein lipids and apoproteins in late pregnancy and postpartum. Possible markers for the diagnosis of "prelipemia". Arteriosclerosis 1984;4:407–17. 10.1161/01.ATV.4.4.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piechota W, Staszewski A. Reference ranges of lipids and apolipoproteins in pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1992;45:27–35. 10.1016/0028-2243(92)90190-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillman L, Schonfeld G, Miller JP, et al. Apolipoproteins in human pregnancy. Metabolism 1975;24:943–52. 10.1016/0026-0495(75)90086-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emet T, Ustüner I, Güven SG, et al. Plasma lipids and lipoproteins during pregnancy and related pregnancy outcomes. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013;288:49–55. 10.1007/s00404-013-2750-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlton F, Tooher J, Rye K-A, et al. Cardiovascular risk, lipids and pregnancy: preeclampsia and the risk of later life cardiovascular disease. Heart Lung Circ 2014;23:203–12. 10.1016/j.hlc.2013.10.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spracklen CN, Smith CJ, Saftlas AF, et al. Maternal hyperlipidemia and the risk of preeclampsia: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2014;180:346–58. 10.1093/aje/kwu145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang C, Zhu W, Wei Y, et al. The predictive effects of early pregnancy lipid profiles and fasting glucose on the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus stratified by body mass index. J Diabetes Res 2016;2016:1–8. 10.1155/2016/3013567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryckman KK, Spracklen CN, Smith CJ, et al. Maternal lipid levels during pregnancy and gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2015;122:643–51. 10.1111/1471-0528.13261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pecks U, Brieger M, Schiessl B, et al. Maternal and fetal cord blood lipids in intrauterine growth restriction. J Perinat Med 2012;40:287–96. 10.1515/jpm.2011.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Contois JH, McConnell JP, Sethi AA, et al. Apolipoprotein B and cardiovascular disease risk: position statement from the AACC lipoproteins and vascular diseases division Working group on best practices. Clin Chem 2009;55:407–19. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.118356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holme I, Aastveit AH, Hammar N, et al. Lipoprotein components and risk of congestive heart failure in 84,740 men and women in the apolipoprotein mortality risk study (AMORIS). Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11:1036–42. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang H, Zhang Y, Yang F, et al. Complement component C4A and apolipoprotein A-I in plasmas as biomarkers of the severe, early-onset preeclampsia. Mol Biosyst 2011;7:2470–9. 10.1039/c1mb05142c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wölter M, Okai CA, Smith DS, et al. Maternal apolipoprotein B100 serum levels are diminished in pregnancies with intrauterine growth restriction and differentiate from controls. Proteomics Clin Appl 2018;12:e1800017. 10.1002/prca.201800017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verma P, Nair RR, Singh S, et al. High level of ApoA1 in blood and maternal fetal interface is associated with early miscarriage. Reprod Sci 2019;26:649–56. 10.1177/1933719118783266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flood-Nichols SK, Tinnemore D, Wingerd MA, et al. Longitudinal analysis of maternal plasma apolipoproteins in pregnancy: a targeted proteomics approach. Mol Cell Proteomics 2013;12:55–64. 10.1074/mcp.M112.018192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serrano NC, Guio-Mahecha E, Quintero-Lesmes DC, et al. Lipid profile, plasma apolipoproteins, and pre-eclampsia risk in the GenPE case-control study. Atherosclerosis 2018;276:189–94. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Funai EF, Friedlander Y, Paltiel O, et al. Long-term mortality after preeclampsia. Epidemiology 2005;16:206–15. 10.1097/01.ede.0000152912.02042.cd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Irgens HU, Reisaeter L, Irgens LM, et al. Long term mortality of mothers and fathers after pre-eclampsia: population based cohort study. BMJ 2001;323:1213–7. 10.1136/bmj.323.7323.1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Retnakaran R, Ye C, Connelly PW, et al. Serum ApoA1 (apolipoprotein A-1), insulin resistance, and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in human Pregnancy-Brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2019;39:2192–7. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lappas M, Georgiou HM, Velagic A, et al. Do postpartum levels of apolipoproteins prospectively predict the development of type 2 diabetes in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus? Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2019;127:353–8. 10.1055/a-0577-7700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dargham SR, Ahmed L, Kilpatrick ES, et al. The prevalence and metabolic characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome in the Qatari population. PLoS One 2017;12:e0181467. 10.1371/journal.pone.0181467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boiko AS, Mednova IA, Kornetova EG, et al. Apolipoprotein serum levels related to metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. Heliyon 2019;5:e02033. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bashir M, Aboulfotouh M, Dabbous Z, et al. Metformin-treated-GDM has lower risk of macrosomia compared to diet-treated GDM- a retrospective cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2020;33:2366–71. 10.1080/14767058.2018.1550480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosing U, Samsioe G, Olund A, et al. Serum levels of apolipoprotein A-I, A-II and HDL-cholesterol in second half of normal pregnancy and in pregnancy complicated by pre-eclampsia. Horm Metab Res 1989;21:376–82. 10.1055/s-2007-1009242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fuior EV, Gafencu AV. Apolipoprotein C1: its pleiotropic effects in lipid metabolism and beyond. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:5939. 10.3390/ijms20235939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gautier T, Masson D, de Barros JP, et al. Human apolipoprotein C-I accounts for the ability of plasma high density lipoproteins to inhibit the cholesteryl ester transfer protein activity. J Biol Chem 2000;275:37504–9. 10.1074/jbc.M007210200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pillois X, Gautier T, Bouillet B, et al. Constitutive inhibition of plasma CETP by apolipoprotein C1 is blunted in dyslipidemic patients with coronary artery disease. J Lipid Res 2012;53:1200–9. 10.1194/jlr.M022988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ooi EMM, Barrett PHR, Chan DC, et al. Apolipoprotein C-III: understanding an emerging cardiovascular risk factor. Clin Sci 2008;114:611–24. 10.1042/CS20070308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khetarpal SA, Zeng X, Millar JS, et al. A human APOC3 missense variant and monoclonal antibody accelerate apoC-III clearance and lower triglyceride-rich lipoprotein levels. Nat Med 2017;23:1086–94. 10.1038/nm.4390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qamar A, Khetarpal SA, Khera AV, et al. Plasma apolipoprotein C-III levels, triglycerides, and coronary artery calcification in type 2 diabetics. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2015;35:1880–8. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ding X, Yang Z, Han Y, et al. Adverse factors increase preeclampsia-like changes in pregnant mice with abnormal lipid metabolism. Chin Med J 2014;127:2814–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flood-Nichols SK, Stallings JD, Gotkin JL, et al. Elevated ratio of maternal plasma ApoCIII to apoCII in preeclampsia. Reprod Sci 2011;18:493–502. 10.1177/1933719110390390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gong T, Zhou R. ApoC3: an 'alarmin' triggering sterile inflammation. Nat Immunol 2020;21:9–11. 10.1038/s41590-019-0562-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mahley RW, Huang Y, Weisgraber KH. Putting cholesterol in its place: apoE and reverse cholesterol transport. J Clin Invest 2006;116:1226–9. 10.1172/JCI28632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Curtiss LK, Boisvert WA. Apolipoprotein E and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol 2000;11:243–51. 10.1097/00041433-200006000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li J, Chen Y, Wu H, et al. Apolipoprotein E (apo E) gene polymorphisms and recurrent pregnancy loss: a meta-analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet 2014;31:139–48. 10.1007/s10815-013-0128-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barker WC, Dayhoff MO. Evolution of lipoproteins deduced from protein sequence data. Comp Biochem Physiol B 1977;57:309–15. 10.1016/0305-0491(77)90060-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ference BA, Graham I, Tokgozoglu L, et al. Impact of lipids on cardiovascular health: JACC health promotion series. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1141–56. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kampmann U, Knorr S, Fuglsang J, et al. Determinants of maternal insulin resistance during pregnancy: an updated overview. J Diabetes Res 2019;2019:1–9. 10.1155/2019/5320156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All underlying data relating to this study will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.