Abstract

The cardiovascular effects of electronic cigarette use are unknown. Here we present a case describing a young, previously healthy patient without prior cardiopulmonary comorbidities who developed severe, acute cardiac dysfunction in the setting of e-cigarette use, in addition to the more commonly encountered respiratory symptoms. While pulmonary manifestations are characteristic of e-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury (EVALI), the acute and reversible cardiomyopathy seen here has not been previously described in association with either EVALI or e-cigarette use.

Keywords: heart failure, respiratory system, adult intensive care, occupational and environmental medicine, drug misuse (including addiction)

Background

Electronic cigarettes (ECs) are a new, increasingly popular nicotine product, even among non-smokers. EC use has increased substantially among teenagers and currently over one fifth of high school students use them.1 There are over 7700 flavours of EC, some of which, like bubblegum and cotton candy, appear to target teenagers. EC use predisposes children and teenagers to tobacco cigarette (TC) use in adulthood2 and the consequent diseases associated with TC use as adults.

The impact of delivery device, flavour, heat inhalation and inclusion of novel chemicals on the development of EC-associated cardiovascular toxicity is unknown and complicated due to minimal product regulation and lack of ingredient transparency. Chemicals to enhance flavours pose additional threats. Vitamin E acetate, used to thicken marijuana oil, is found commonly in broncho-alveolar lavage samples in patients who developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) after using tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing EC fluid.3 4

Case presentation

A 19-year-old woman was transferred from an outside hospital for tertiary centre evaluation and treatment of hypoxaemia.

She presented 1 week prior with progressive dyspnoea and productive cough. She was diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia and treated with azithromycin at home. Her symptoms worsened requiring hospitalisation. Her respiratory status continued to deteriorate despite antibiotics and treatment, requiring bilevel positive airway pressure, and she was transferred to a tertiary care centre.

On arrival, she reported symptoms including a minimally productive, non-bloody cough, dyspnoea, sinus and throat irritation, dizziness and headache. She denied fevers or chills. She denied any current or history of chest pain or palpitations. Her medical history included recreational benzodiazepine and oral opioid use, interstitial nephritis and exercise-induced asthma. Family history was negative for sudden cardiac death or congenital heart disease. Social history revealed an active lifestyle in lacrosse and a 3-year history of electronic Juice USB Lighting cigarette and vaporised marijuana use.

On examination, she was in significant respiratory distress, with supraclavicular and intercostal retractions. She was hypoxic, with escalating oxygen requirement to maintain oxygen saturations >90%. She was otherwise afebrile and normotensive. Cardiac examination revealed a normal S1 and S1, without murmurs or gallops, with brisk distal pulses. Lung auscultation revealed vesicular breath sounds without crackles or wheezes. The examination was otherwise normal.

Investigations

Initial ECG demonstrated normal sinus rhythm with non-specific ST segment depressions in V1 and V2 with T wave inversions in AVL and V3 and prolonged QTc. Initial transthoracic echocardiography showed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 55% with normal regional wall movement and no valvular dysfunction. Laboratory results included not detected antineutrophil antibody, negative Streptococcus pneumoniae antigen, negative Legionella antigen and negative HIV test. Lactate dehydrogenase 1817 μ/L (reference range 313–618 μ/L), haptoglobin 362 md/dL (reference range 30–178 mg/dL) and d-dimer tests 3360 ng/mL (reference range <499 ng/mL) were elevated. Initial troponin I was 0.415 ng/mL (reference range <0.04 ng/mL) and brain natriuretic peptide was 3750 pg/mL (reference range <125 pg/mL). (table 1).

Table 1.

Serum concentrations of troponin I, creatinine-kinase-MB isozyme (CK-MB), total creatine kinase (CK) and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT proBNP) over time

| Dates | Troponin I (ng/mL) | CK-MB (IU/L) | CK total (IU/L) | NT proBNP (pg/mL) |

| 17 September 2019 | 30 | |||

| 18 September 2019 | 3750 | |||

| 20 September 2019 | 0.415 | 16 200 | ||

| 21 September 2019 | 0.23 | 14 000 | ||

| 23 September 2019 | <0.2 | |||

| 27 September 2019 | 676 | |||

| 28 August 2019 | 116 |

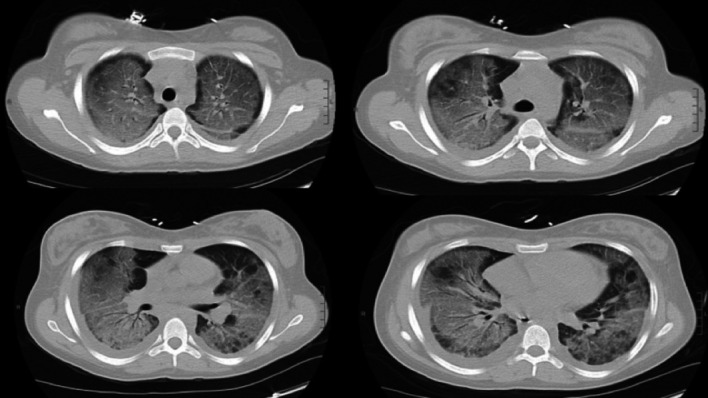

Chest CT (figure 1) showed, in addition to findings consistent with EVALI including diffuse peribronchial ground-glass opacities with peripheral sparing,5 prominent septal lines and pleural effusions, suggesting volume overload. Repeat transthoracic echocardiogram was therefore done, demonstrating a newly reduced ejection fraction of 35%–40% with diffuse left ventricular hypokinesis. Serial electrocardiograms were unchanged and demonstrated normal sinus rhythm, normal axis and no evolving ischaemic changes. Her troponin I decreased to 0.23 ng/mL, creatine kinase-MB was <0.2 ng/mL and brain natriuretic peptide remained elevated to 14 000 pg/mL. Additional laboratory work up included negative antinuclear, rheumatoid factor, scleroderma, anti-RNP, anticentromere, anti-Smith and parvovirus IgM antibodies and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 45 mm/hour (reference range 0–20 mm/hour) and C reactive protein 5 mg/dL (reference range <1 mg/dL). Respiratory viral panel and influenza tests were negative. This case preceded the appearance of SARS-CoV-2, and therefore, no evaluation for SARS-CoV-2 was done.

Figure 1.

Four CT chest images showing diffuse ground glass infiltrates, prompting transfer to our tertiary care centre for escalation of care.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for this patient’s acute cardiomyopathy included impaired perfusion due to coronary plaque rupture, coronary vasospasm or myocardial bridge, hypoxic demand ischaemia, infiltrative or infectious cardiomyopathy, coronary vasospasm or direct toxic effect from EC use.

Treatment

As is standard for EVALI, high-dose steroids were given with plans for a long taper along with pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PCP) prophylaxis with sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim.6 As the diacetyl present in vape liquid can worsen bronchoconstriction, scheduled bronchodilators were also employed. She was treated for concomitant volume overload with aggressive diuresis with furosemide. Empiric antimicrobial therapy was continued with levofloxacin. After 9 days, supplemental oxygen was weaned off entirely.

Outcome and follow-up

Repeat transthoracic echocardiogram showed resolution of global hypokinesis and recovery of ejection fraction to 55%. Patient reported resolution of symptoms and return to regular vigorous exercise.

Discussion

The effects of EC are unknown, while substantial research clarifies TC cardiovascular effects. Several authors compare TC to EC, extrapolating previously identified mechanisms to demonstrate how EC might impact cardiovascular health.7–13 Few reports associating acute cardiovascular disease with EC use exist, and there remains no widely understood mechanism to explain acute cardiac dysfunction from EC exposure.14

Here we present a case describing a previously healthy patient without prior cardiopulmonary comorbidities who developed respiratory distress and transient severe systolic dysfunction in the setting of EC use. While the pulmonary manifestations suggest EVALI, the acute, reversible cardiomyopathy has not been previously described in association with EVALI.5 Hypoxaemia associated with EVALI is common, but cardiomyopathy is not.15 Further, hypoxaemia was treated immediately with increasing support to adequate oxygen saturations in this case, making hypoxaemia as a driver of cardiomyopathy unlikely. Coronary vasospasm was not supported clinically as electrocardiograms remained stable, without evolving ischaemic changes, and she lacked chest pain throughout the hospitalisation. No other toxins known to contribute to vasospasm such as cocaine were identified. Testing for viruses that cause cardiomyopathy was negative. The patient was unknown to have any congenital cardiac predisposition to cardiomyopathy. Most myocardial bridges are symptomatic. Her lifelong tolerance of vigorous exercise without symptoms argued against pursuing diagnostic testing for myocardial bridge. Acute coronary syndrome secondary to plaque rupture was unlikely given the patient’s young age. The acuity of this presentation would be unusual for an infiltrative cardiomyopathy, like sarcoidosis or amyloidosis, and evaluation lacked support such as low voltage on ECG or echocardiography findings like ventricular hypertrophy, evidence of ground-glass myocardium, sparing of wall motion abnormalities or strain pattern. Therefore, further imaging such as a cardiac MRI was not pursued. Sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy was considered; however, an infectious source was not identified and hypotension did not develop. Autoimmune cardiomyopathy was deemed unlikely because all autoimmune laboratory tests were normal.

The absence of any other cardiomyopathy aetiology, therefore, suggests that the cardiomyopathy may have been a direct effect of EC toxicity itself. The inflammatory cascade after inhalation of chemical compounds in EC, particularly vitamin E acetate and other volatile hydrocarbons, is the cornerstone behind the development of the sterile pneumonitis that characterises EVALI.16 Similar to the cytokine effects on cardiac function in sepsis, this inflammatory cascade in response to inhaled EC compounds might explain the acute decreased cardiac function in this patient.

Additionally, rapid escalation of sympathetic tone in EVALI caused by the high concentrations of nicotine found in EC can explain some of the impaired cardiac function exhibited in our patient. Heart rate variability (HRV) is a measure of sympathetic activation and, when elevated, is associated with increased cardiac mortality.7 10 Specifically, elevated HRV increases the risk of acute life-threatening arrhythmias, acute ischaemia and activation/progression of inflammatory atherosclerosis. EC users demonstrate the same pattern of abnormal HRV that has been identified in TC users and is associated with increased cardiovascular risk.8 10 While these findings implicate long-term cardiovascular effects in chronic EC users, to date, no clear studies show EC use causes significant acute variations in cardiovascular function. One small observational study did not show acute differences in various cardiovascular measures (including heart rate, blood pressure, endothelial function (via flow-mediated dilation) and arterial stiffness (via cardio-ankle vascular index)) in young, healthy, non-smoking patients who used menthol-flavoured EC with 0% or 5.4% nicotine.7

Compounds in EC contain heavy metals, aldehydes and other oxidants. ECs have similar oxidant activity as TC.7 Studies have compared oxidised low -density lipoprotein (LDL) in chronic versus non-EC users and plasma myeloperoxidase as a marker of oxidant stress in placebo versus EC without nicotine and EC with nicotine. In the former study, oxidised LDL was significantly higher in EC users when compared with non-smokers, and the later study showed EC with nicotine acutely raised myeloperoxidase levels, while placebo and non-nicotine EC did not, implicating nicotine as the culprit.7 9 Myocardial ischaemia as a result of platelet activation in the coronary arteries is a serious adverse event that is associated with TC use. Whether long-term EC use carries the same risks of thrombus formation as TC is unclear. TC and EC acutely elicit similar rates of platelet activation in chronic TC users.13 This result was not replicated in non-smokers, where TC was associated with significantly greater platelet dysfunction.

The cardiovascular implications of the sympathetic nervous system activation in EC and TC users have been investigated for impact on cardiovascular disease and mortality. Through the spleno-cardiac axis, the sympathetic nervous system activates the bone marrow to produce progenitor cells that mature and multiply into proinflammatory monocytes.17 Monocytes then enter the systemic circulation, which results in oxidative stress and increased prothrombotic factors that accelerate atherosclerosis in arterial vessels.18 By measuring F-flurorodeoxyglucose (F-FDG) uptake (a marker of metabolic activity), Boas et al demonstrated a dose–response relationship between FDG uptake in the aorta vascular wall and EC or TC use. F-FDG uptake was lowest in non-users, intermediate in EC users and highest in TC users, correlating with increased inflammation.18

Surrogate markers, such as blood flow and changes in endothelial progenitor cells, suggest that EC and TC might lead to comparable inflammation. Flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and arterial stiffness as measured by pulse wave velocity (PWV) are independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease that have been noted in TC use. Studies comparing the acute changes to FMD and PWV after TC or EC use showed that both resulted in changes to the FMD, suggesting impairment of endothelial function.12 TC and EC use result in comparable acute changes in PWV, supporting the belief that EC portends some of the same cardiovascular risks as TC.13 Equivalent increases of endothelial progenitor cells are seen among TC and EC users, representing similar rates of vascular endothelial damage.18 While these studies identify known adverse cardiovascular effects associated with TC in EC users, further study of the long-term cardiovascular effects of EC is required. Additionally, traditional goal-directed cardiomyopathy therapy must be evaluated for outcomes among those with EC-related cardiomyopathy.

Learning points.

Much remains unknown about the potential long-term cardiovascular effects of electronic cigarette (EC) use, especially in patients who begin using EC in adolescence and young adulthood.

The inflammatory cascade and hypoxaemia caused by e-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury itself can lead to acutely compromised cardiovascular function.

EC contains compounds and nicotine levels that are known to adversely affect cardiovascular health, but more studies need to be done to determine the acute and long-term cardiovascular effects of EC use.

Footnotes

Twitter: @RAmirahmadi

Contributors: RA wrote and edited most of the manuscript, as well as contributed to the literature review. JC contributed significantly to the literature review. SP also contributed to the literature review, as well as the chart review about the patient’s history and hospital course. L-AW guided the focus of the case study and edited the manuscript at each stage of drafting.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Products C . 2018 NYTS data: a startling rise in youth e-cigarette use. FDA, 2020

- 2.The University of Maryland . The American Heart Association takes on vaping: full text finder results. Available: http://resolver.ebscohost.com.proxy-hs.researchport.umd.edu/openurl?sid=EBSCO:cmedm&genre=article&issn=15383598&ISBN=&volume=&issue=&date=20200103&spage=&pages=&title=JAMA&atitle=The%20American%20Heart%20Association%20Takes%20on%20Vaping.&aulast=Abbasi%20J&id=DOI:10.1001/jama.2019.20781 [Accessed 12 Feb 2020].

- 3.Cobb NK, Solanki JN. E-cigarettes, vaping devices, and acute lung injury. Respir Care 2020;65:713–8. 10.4187/respcare.07733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carnevale R, Sciarretta S, Violi F, et al. Acute impact of tobacco vs electronic cigarette smoking on oxidative stress and vascular function. Chest 2016;150:606–12. 10.1016/j.chest.2016.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kligerman S, Raptis C, Larsen B, et al. Radiologic, pathologic, clinical, and physiologic findings of electronic cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury (EVALI): evolving knowledge and remaining questions. Radiology 2020;294:491–505. 10.1148/radiol.2020192585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel DA, Jatlaoui TC, Koumans EH, et al. Update: interim guidance for health care providers evaluating and caring for patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury — United States, October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:919–27. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6841e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cossio R, Cerra ZA, Tanaka H. Vascular effects of a single bout of electronic cigarette use. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2020;47:3–6. 10.1111/1440-1681.13180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Middlekauff HR, Park J, Moheimani RS. Adverse effects of cigarette and Noncigarette smoke exposure on the autonomic nervous system. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:1740–50. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middlekauff HR. Cardiovascular impact of electronic-cigarette use. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2020;30:S1050173819300519 10.1016/j.tcm.2019.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rovere MTL, Bigger JT, Marcus FI, et al. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart-rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. The Lancet 1998;351:478–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11144-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaumont M, de Becker B, Zaher W, et al. Differential effects of e-cigarette on microvascular endothelial function, arterial stiffness and oxidative stress: a randomized crossover trial. Sci Rep 2018;8:10378. 10.1038/s41598-018-28723-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vlachopoulos C, Ioakeimidis N, Abdelrasoul M, et al. Electronic cigarette smoking increases aortic stiffness and blood pressure in young smokers. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:2802–3. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kavousi M, Pisinger C, Barthelemy J-C. Electronic cigarettes and health with special focus on cardiovascular effects: position paper of the European association of preventive cardiology (EAPC). Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020;16. 10.1177/2047487320941993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King BA, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, et al. The EVALI and youth vaping epidemics — implications for public health. New England Journal of Medicine 2020;382:689–91. 10.1056/NEJMp1916171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chand HS, Muthumalage T, Maziak W, et al. Pulmonary toxicity and the pathophysiology of electronic cigarette, or Vaping product, use associated lung injury. Front Pharmacol 2019;10:1619. 10.3389/fphar.2019.01619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Libby P, Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK. Leukocytes link local and systemic inflammation in ischemic cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:1091–103. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boas Z, Gupta P, Moheimani RS, et al. Activation of the "Splenocardiac Axis" by electronic and tobacco cigarettes in otherwise healthy young adults. Physiol Rep 2017;5:e13393. 10.14814/phy2.13393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antoniewicz L, Bosson JA, Kuhl J, et al. Electronic cigarettes increase endothelial progenitor cells in the blood of healthy volunteers. Atherosclerosis 2016;255:179–85. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.09.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]