Abstract

Approximately 3 in 1000 children in the US under 4 years of age are affected by hearing loss. Currently, cochlear implants represent the only line of treatment for patients with severe to profound hearing loss, and there are no targeted drug or biological based therapies available. Gene replacement is a promising therapeutic approach for hereditary hearing loss, where viral vectors are used to deliver functional cDNA to “replace” defective genes in dysfunctional cells in the inner ear. Proof-of-concept studies have successfully used this approach to improve auditory function in mouse models of hereditary hearing loss, and human clinical trials are on the immediate horizon. The success of this method is ultimately determined by the underlying biology of the defective gene and design of the treatment strategy, relying on intervention before degeneration of the sensory structures occurs. A challenge will be the delivery of a corrective gene to the proper target within the therapeutic window of opportunity, which may be unique for each specific defective gene. Although rescue of pre-lingual forms of recessive deafness have been explored in animal models thus far, future identification of genes with post-lingual onset that are amenable to gene replacement holds even greater promise for treatment, since the therapeutic window is likely open for a much longer period of time. This review summarizes the current state of adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene replacement therapy for recessive hereditary hearing loss and discusses potential challenges and opportunities for translating inner ear gene replacement therapy for patients with hereditary hearing loss.

1. Introduction:

Hearing loss is a common disorder affecting newborns and children. Clinically significant hearing loss is confirmed in nearly 3 out of 1000 children under the age of 4 in the United States each year1-3. Approximately half of these affected children have a genetic cause of their hearing loss4. Currently, novel and rare variants in over 150 identified deafness genes have been reported5, and as a whole these individual genetic variants represent a prevalent problem6. Universal newborn hearing screening is mandatory in every US state to identify affected patients at birth, and genetic diagnosis typically takes place after a child has failed the initial screen and follow-up7. The majority (80%) of hereditary hearing loss involves autosomal recessive inheritance and causes sensorineural hearing loss, where the source of hearing loss is localized to specialized cells within the inner ear7. These cells are encased within the fluid-filled cochlea and include sensory hair cells, auditory neurons, and non-sensory cells involved in maintaining the unique structure and ionic environment of the inner ear8. Typically, those with autosomal recessive hearing loss are severely hearing impaired at birth and are born to hearing parents that are unknowing carriers of a loss-of-function mutation or deletion in the same gene7. A mutant allele of the gene inherited from each parent results in either limited or none of the protein product being produced by the cells, or the production of a non-functional protein.

The treatment options for patients with hereditary hearing loss are limited. While patients with mild-to-moderate hearing loss may benefit from hearing aids, those with severe to profound hearing loss usually require cochlear implantation to improve their auditory perception. While cochlear implants are revolutionary in their ability to improve speech perception for severely hearing-impaired patients, many aspects of hearing remain challenging for implant wearers, such as music perception, sound localization, and the ability to understand speech in a noisy environment9. Inner ear gene therapy has the potential of restoring normal cellular function in the cochlea, thereby improving auditory function. Over the past few years, several studies have successfully applied inner ear gene therapy to animal models of hereditary hearing loss10-29. The most commonly used strategy for inner ear gene therapy is gene replacement, where normal copies of the cDNA of the target gene are delivered into the inner ear to compensate for the lack of functional gene product caused by the defective gene. Gene replacement is a useful strategy for treating loss-of-function mutations, and is the most straightforward approach in gene therapy. In contrast, dominant forms of hearing loss are often caused by mutations that lead to the production of an abnormal protein product which may interfere with normal cellular function30. Therefore, variants associated with dominant forms of hearing loss are typically not good targets for gene replacement, but are good targets for strategies which inhibit the expression of the dominant mutant allele19,31.

Gene replacement therapy has recently been approved by the FDA to treat a rare form of hereditary blindness called Leber’s congenital amaurosis (Luxturna, approved in 2017), as well as spinal muscular atrophy (Zolgensma, approved in 2019). The approval of these therapies represents a major milestone in the development of advanced precision therapeutics designed to treat inherited diseases. Both approved therapies are based on a gene delivery vector known as adeno-associated virus (AAV). AAV is a parvovirus that is dependent on adenovirus or herpesvirus co-infection for efficient replication32,33. It is non-pathogenic in humans. Replication deficient AAV vectors are derived from the naturally occurring virus by replacing the viral DNA with an expression cassette containing the therapeutic transgene, which is then packaged into the viral capsid composed of AAV structural proteins32. This is accomplished by flanking the transgene cassette with the viral inverted terminal repeat (ITR) elements that act as DNA packaging signals for the AAV non-structural proteins. Recombinant vectors are generated and packaged in producer cells by providing a plasmid for the structural (Cap) and non-structural (Rep) viral proteins separate from the plasmid that contains the ITR flanked transgene cassette, as well as the adenovirus or herpes virus helper genes32. After target cell entry, AAV vector genomes typically persist in the nucleus in an extrachromosomal form, such as an episome or high molecular weight concatamers34,35. An AAV vector-based approach for gene delivery has many advantages, such as high gene transfer efficiency, stable transgene expression, broad cellular tropism, low immunogenicity, and rare integration into the host DNA32. AAV vectors are produced from many different naturally occurring capsids, including serotypes 1-12 and over 100 primate isolates36. The capsid proteins are semi-modular, with conserved regions that do not tolerate alteration and distinct variable regions amenable to protein engineering approaches that have been used to generate synthetic capsids with improved transduction efficiency and cell targeting37. The main disadvantage of AAV is the fact that the packaging capacity for AAV is only approximately 4.2kb, assuming the minimal lengths for the ITR, promoter, and poly-A sequences38. Despite this disadvantage, AAV remains one of the most commonly used viral vectors in human gene therapy clinical trials today due to its well characterized biosafety profile39.

In this review, we will summarize the published studies on the application of AAV gene replacement therapy to various mouse models of autosomal recessive hereditary hearing loss. We will also discuss the opportunities and challenges that lie ahead for the translation of inner ear gene replacement therapy to patients with hereditary hearing loss.

2. Gene replacement studies for hereditary hearing loss (Figure 1, Table 1):

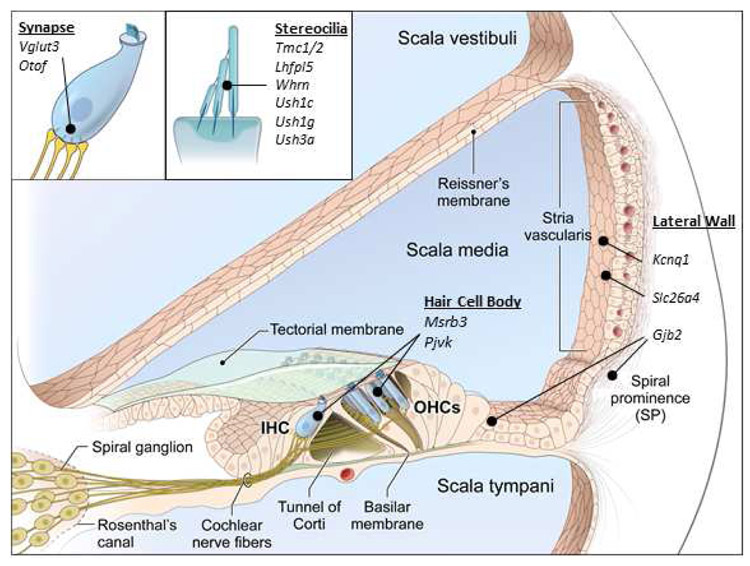

Figure 1: Variants in genes with diverse functions can cause hereditary hearing loss.

This figure illustrates the location of genes that have been successfully targeted for inner ear gene replacement therapy in the cochlea (figure modified from Faridi et al., 2018123).

Table 1.

Summary of AAV-mediated inner ear gene replacemet thearpy for recessive inner ear dysfunction.

| Study (authors and date published) |

Therapeutic gene |

Vector Used | Promoter | Mouse Strain | Age of Injection |

Vector Copies per ear | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akil et al., 2012 | VGLUT3 | AAVl | CBA | Vglut3 KO | P0-P3, P10 | 2.3e10 vg | 50dB threshold improvement, best performers within 10dB of wild-type mice |

| yu, Wang et al., 2014 | GJB2 | AAV1 | CB7 | Gjb2 cKO | PD-P1 | 3e9 - 7.5e9 vg | No threshold improvement, improved cellular gap junction function |

| Crispino et al., 2017 | GJB2 | BAAV | CMV | Gjb6 KO | P4 | 1e9 vg | No threshld improvement |

| Chang, Wang et al., 2015 | KCNQ1 | AAVl | CB7 | Kcnq1 KO | PO-P2 | 2.5e9 - 1.5e10 vg | 50dB threshold improvement to within 20-30 dB of wild-type mice |

| Askew et al., 2015 | TMC1, TMC2 | AAVl | CBA | Tmc1 KO, TMC1 -Bth | P0-P2 | 1e10 vg | 30dB threshold improvement at lower frequencies |

| Nist-Lund, Pan et al., 2019 | TMC1 | AAV1, Anc80 | CMV | Tmc1 KO | P0-P2 | 1.4e11 vg | 40dB threshold improvement, best performers within 10-20dB of wild-type mice. Improved breeding efficiency, litter survival and normal growth rate |

| Chien et al., 2015 | WHRN | AAV8 | CMV | Whrn wi/wi | P1-P5 | 5e10 vg | Increased stereocilia length. No auditory threshold improvement |

| Isgrig et al., 2017 | WHRN | AAV8 | CMV | Whrn wi/wi | P0-P5 | 1e10 vg | 20dB threshold improvement, increased hair cell survival, improved vestibular function |

| Delmaghani et al., 2015 | PJVK | AAVB | CAG, CB7 | Pjvk KO | P3 | 2e10 vg | 20-30dB threshold improvement in the low frequencies |

| Kim et al., 2016 | MSRB3 | AAV1 | CMV | Msrb3 KO | E12.5 | 7e9 - 1e10 vg | 70-80dB threshold improvement to within 10dB of wild type |

| Gyorgy, Sage et al., 2017 | LHFPL5 | AAV1, AAV9, exo-AAV | CBA | Lhfpl5 KO | P1-P2 | 2.7e9 vg | 20-30dB threshold improvement in the mid frequencies |

| Pan, Askew, Galvin et al., 2017 | USH1C | AAV1, Anc80 | CMV | Ush1c c216G>A | P0-P1, P10-P12 | 1.6e9 - 2e9 vg | 40-60dB threshold improvement, best performers close to wild-type at low-mid frequencies, reduced circling behavior |

| Emptoz et al., 2017 | USH1G | AAVB | CB6 | Ush1g KO | P0-P3 | 2e10 vg | 20-30dB threshold improvement at low frequencies |

| Geng, Akil et al., 2017 | USH3A | AAV2, AAV8 | smCBA | Clrn1 cKO | P1-P3 | 2e10 vg | ~40dB threshold improvement |

| Dulon et al., 2018 | USH3A | AAVB | not reported | Clrn1 ex4−/−,cKO | P1-P3 | 1.2e10 vg | 10-20dB threshold improvement in KO mice, 30-40dB improvement in cKO mice. Hearing loss progressed over time |

| Gyorgy, Meijer, Ivanchenko et al., 2019 | USH3A | AAV-PHP.B | CBA | Clrn1 KO | P1 | 1.8e11 vg | ~20dB threshold improvement at low frequencies, best performers had 50dB improvement |

| Kim et al., 2019 | SLC26A4 | AAV1 | CMV | Slc26a4 KO, KI | E12.5 | 1.08e10 vg | 60-70dB threshold improvement to within 10-20 dB of wild type, though hearing fluctuation and hearin loss occurs over time |

| Al-Moyed et al., 2019 | OTOF | Dual AAV6 | HBA/CMV | Otof KO | P6-P7 | 1.2-1.38e10 vg each vector | 20-30dB threshold improvement in the low frequencies, best performers had 50dB improvement |

| Akil et al., 2019 | OTOF | Dual AAV2 quad Y-F | CAG | Otof KO | P10, P17, P30 | ~1e10 vg each vector | 50dB threshold improvement, best performers equal to wild-type mice |

VGLUT3 (Akil et al., 2012)11

The first study to successfully apply AAV-mediated gene replacement in a mouse model of hereditary hearing loss involved VGLUT3, which encodes a glutamate transporter necessary for inner hair cell synaptic transmission40. Mutations in VGLUT3 are associated with the non-syndromic autosomal dominant hearing loss DFNA2541. In this study, AAV1-chick β-actin (CBA)-Vglut3 (2.3x1013 vg/mL) was injected into the cochlea of Vglut3 knockout mice. The authors used both cochleostomy and round window membrane (RWM) injection routes at either P0-P3 or P10 days of age. RWM injection at P0-P3 rescued hearing thresholds in all treated mice to within 10 dB of wild-type animals, and the hearing rescue persisted for over a year. Cochleostomy at P0-P3 also resulted in hearing rescue, but only in approximately 20% of injected mice. Mice injected at P10 demonstrated initial rescue at 7 weeks post injection, but their thresholds deteriorated with age, indicating that the rescue was not durable when gene delivery was performed at P10. Since the outer hair cells are not involved in the pathology in this animal model, and none of the hair cells degenerate over time, it was a good model to demonstrate the proof-of-principle for gene replacement therapy. However, VGLUT3-related deafness is very rare in humans, and when it is present it causes autosomal dominant hearing loss (DFNA25), which may not be amenable to gene replacement strategy, as discussed previously.

GJB2 and GJB6 (Yu and Wang et al., 2014, Crispino et al., 2017)29,42

Connexins are a family of tetraspan proteins which form gap junctions43. Gap junctions play an important role in the intercellular coupling between the non-sensory cells in the mammalian inner ear44. GJB2 and GJB6 encode connexin 26 and connexin 30, respectively, and they are prominently expressed in the mammalian cochlea45. Mutations in GJB2 and GJB6 are common causes of inherited non-syndromic hearing loss in the United States46. In the study by Yu et al., Gjb2 gene replacement therapy was delivered to a conditional knockout mouse model of connexin 26 (cCx26KO)29. The conditional knockout of Gjb2 was achieved using Foxg1-Cre, which limits the gene knockout to the inner ear (at E19). Since connexin 26 is critical for potassium homeostasis and maintenance of the endocochlear potential, the structural and physiological development of the cochlear sensory epithelium arrests during the first postnatal week, and cochlear hair cells begin to degenerate after P14 in these mutant mice29. The authors delivered AAV1-CB7-Gjb2 (0.2-0.5μl of 1.5x1013 vg/mL) into the P0-P1 cCx26KO mouse cochlea via cochleostomy. They showed that over-expression of exogenous connexin 26 in wild-type cochlea is not detrimental to auditory function when using AAV1, even though AAV1 robustly infected hair cells (up to 44% transduced), which do not typically express connexin 26. Expression of exogenous GJB2 rescued propidium iodide diffusion between supporting cells, indicating restoration of the junctional complexes among these cells. Additionally, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) demonstrated that calcein AM dye diffuses from surrounding cells back into the bleached cell after AAV1-Gjb2 treatment, which does not occur in the knockout mouse. These assays demonstrated cellular level improvement of gap junction function in treated mutant mice. Unfortunately, no improvement in hearing thresholds were observed after treatment.

In the study by Crispino et al., they examined whether Gjb2 gene replacement therapy could improve the auditory function in the Gjb6 knockout mouse (Cx30−/−)42. This is based on a previous study which showed that overexpression of connexin 26 using a modified bacterial artificial chromosome could rescue hearing in the Cx30−/− knockout mice47. When the authors delivered Gjb2 to the Cx30−/− knockout mice at P4 using a bovine AAV, which has been shown to transduce inner ear hair cells and supporting (BAAV-CMV-Gjb2, ~1x109 vg), they found that hearing was not rescued in these Cx30−/− knockout mice. In summary, these two studies suggest that while gene replacement therapy may be able to restore gap junction function in the mouse inner ear, hearing recovery was not observed. This could be explained in part by the viral vectors used in these studies (AAV1 and BAAV), which may not be capable of transducing all the necessary cell types in the inner ear to restore auditory function. It is also possible that Gjb gene replacement therapy may need to be delivered at an even earlier time point in mouse auditory development (in utero) for hearing recovery to occur.

KCNQ1 (Chang and Wang et al., 2015)14

Variants of human KCNQ1 and KCNE1 are associated with Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome, characterized by deafness and prolonged QT interval in heart muscle contractions. KCNQ1 is a voltage-gated potassium channel expressed in marginal cells (epithelial) of the stria vascularis. KCNE1 is a β-subunit of this channel and complexes with KCNQ1 to secrete potassium into the endolymph and participates in the generation of the endocochlear potential48. The high potassium in the endolymph is critical for the maintenance of the endocochlear potential, which acts as an ionic battery that drives signaling in the hair cells. AAV1-CB7-Kcnq1 (0.5μl of 5x1012 to 1.5x1013 vg/mL) was injected into the inner ears of Kcnq1 knockout P0-P2 pups. Cochleostomy injection of AAV1-CB7-Kcnq1 in the Kcnq1 knockout mice resulted in transduction of 60-80% of marginal cells along the whole cochlea, and ectopic expression could be seen in neurons, hair cells, and fibrocytes. Gene replacement therapy improved auditory thresholds to within 20-30 dB of the wild-type animals. Endocochlear potential was also restored to wild-type level (~85mV). However, hearing began to deteriorate 4 months after injection. It is unclear if the endocochlear potential also degenerated along with the elevation in hearing thresholds, since it was not measured at later stages. This study was the first to demonstrate functional hearing rescue in a mouse model of lateral wall dysfunction.

TMC1 (Askew et al., 2015; Nist-Lund and Pan et al 2019)13,26

TMC1 is part of the mechanotransduction channel at the tips of shorter-row stereocilia on the apical surface of hair cells and is required for the transduction of mechanical movement of the stereocilia bundle into electrical signals49-51. Loss of TMC1 results in loss of mechanotransduction, hair cell degeneration, and deafness49,52. Mutations in TMC1 are associated with the non-syndromic autosomal recessive hearing loss DFNB7/11, as well as the non-syndromic autosomal dominant hearing loss DFNA3653 In a study by Askew et al. (2015), AAV1-CBA-Tmc1 (1.0μl of 1x1013 vg/mL) was injected into P0-P2 Tmc1 mutant mice (Tmc1Δ/Δ) via RWM. The authors showed that AAV1-CBA-Tmc1 treatment in Tmc1Δ/Δ mutant mice restored hair cell mechanotransduction to near wild-type levels. However, since viral transduction was mostly confined to the inner hair cells and not the outer hair cells, the auditory improvement was approximately 20-30 dB SPL at low frequencies. Interestingly, inner ear delivery of AAV1-CBA-Tmc2 (a paralog of Tmc1) improved inner hair cell survival in the dominant gain-of-function Tmc1 mutant (Bth), demonstrating proof-of-principal for using gene substitution strategy as a treatment for autosomal dominant hearing loss.

In a subsequent study by the same group (Nist-Lund et al., 2019), the synthetic AAV AAV2/Anc80L65 was used to deliver Tmc1 cDNA into the inner ears of Tmc1Δ/Δ mutant mice. The AAV2/Anc80L65 was generated in the lab using modeling of possible ancestral sequences of the AAV capsid gene which could be common to most identified serotypes54. It has been shown to transduce both inner and outer hair cells in the cochlea, as well as vestibular hair cells with high efficiency54. The authors showed that the increased outer hair cell transduction by AAV2/Anc80L65 significantly improved the auditory function in treated Tmc1Δ/Δ mutant mice. ABR thresholds improved approximately 40dB SPL, with the best performers within 10-20dB of wild-type mice. In addition, the authors reported that AAV2/Anc80L65-CMV-Tmc1 delivery also restored vestibular function, breeding efficiency, litter survival and normal growth rate in the Tmc1Δ/Δ mutant mice26. These studies represent the first attempts at using a gene replacement strategy to treat genetic mutations affecting hair cell mechanotransduction. These studies also demonstrate that increasing viral transduction efficiency in targeted cell types is critical for the success of inner ear gene replacement therapy.

WHRN (Chien et al., 2015, Isgrig et al., 2017)15,23

Whirlin (WHRN) is a scaffold protein that is important for stereocilia elongation55. Mutations in the gene encoding whirlin are associated with Usher syndrome type 2D56, as well as the non-syndromic autosomal recessive hearing loss DFNB3155. The whirler mouse (Whrnwi/wi) has a non-sense mutation in Whrn which leads to the absence of functional whirlin protein production55. As a result, the Whrnwi/wi mutant mice have short and dysfunctional stereocilia, which results in deafness and vestibular dysfunction55. In a study by Chien et al. (2015), AAV8-CMV-Whrn (~0.5 μl at 1x1013 vg/ml) was injected into neonatal Whrnwi/wi mutant mice (P1-P5) via RWM. While stereocilia length was improved in transduced inner hair cells, auditory function was not improved. This was attributed to the low levels of inner hair cell transduction (~10-15%)15.

In a follow up study by the same group, Isgrig et al. (2017) showed that when AAV8-CMV-Whrn (1 μl at 1x1013 vg/ml) was delivered through the posterior semicircular canal approach to Whrnwi/wi mutant mice (P0-P5), hair cell transduction was greatly improved not only in the vestibular organs, but also in the cochlea23. Partial hearing recovery was observed, with ABR thresholds at 60-70dB SPL in some treated mutant mice. In addition, vestibular function was also improved, as evidenced by a reduction in circling behavior and improvement in rotarod and swim tests. Improvement in circling behavior lasted for at least 4 months, although the partial hearing recovery deteriorated during that time. Hair cell survival in treated Whrnwi/wi mutant mice was improved compared to untreated mutant mice. These two studies delivered the same viral gene replacement therapy (AAV8-CMV-Whrn) to neonatal Whrnwi/wi mice using two different surgical approaches (RWM vs. posterior semicircular canal), and showed that the posterior semicircular canal approach resulted in better auditory and vestibular recovery compared to the RWM gene delivery, likely due to the higher hair cell transduction efficiency obtained using the posterior semicircular canal approach. The results from these two studies demonstrate the importance of surgical approach selection for the success of inner ear gene replacement therapy.

PJVK (Delmaghani et al., 2015)16

Pejvakin (PJVK) is a peroxisome-associated protein that is involved with oxidative stress-induced peroxisome proliferation16. Mutations in PJVK are associated with the non-syndromic autosomal recessive hearing loss DFNB5957. Pjvk knockout mice have elevated hearing thresholds and are hyper-vulnerable to sound exposure16. When AAV8-Pjvk was delivered to the inner ears of the Pjvk knockout mice via the RWM (2μl, 1x1013 vp/ml), ABR threshold improvement of 20-30 dB SPL was achieved at low frequencies. In addition, the hair cell peroxisome proliferation response to noise exposure was also restored in treated Pjvk mutant mice16. This was the first study to apply gene replacement therapy to treat genetic mutations affecting the peroxisome system in the mammalian inner ear.

MsrB3 (Kim et al., 2016)24

Methionine sulfoxide reductase B3 (MsrB3) plays an important role in hair cell homeostasis58. Mutations in MSRB3 are associated with the non-syndromic autosomal recessive hearing loss DFNB7459, and the MsrB3 knockout mouse is profoundly deaf, similar to DFNB74 patients. In this study, AAV2/1-CMV-MsrB3-GFP (1.31.1013 vg/ml) was injected into the otocyst of MsrB3 knockout mice at E12.5, using a previously described in utero gene delivery protocol60. Significant improvement in auditory thresholds was observed in treated MsrB3 knockout mice compared to untreated mutant mice (70-80 dB SPL improvement). Unfortunately, the hearing improvement was not permanent, with hearing deterioration being observed starting at approximately 7 weeks postnatally24 The authors also found that the treated MsrB3 knockout mice have restored stereocilia morphology compared to untreated mutant mice, but the restoration of stereocilia morphology was also short-lived, with stereocilia degeneration occurring starting at 5 weeks postnatally24. This was the first attempt to apply an in utero gene replacement strategy in a mouse model of hereditary hearing loss.

LHFPL5 (Gyorgy and Sage et al., 2017)22

LHFPL5 (also known as TMHS) is present at the stereocilia tips of both inner and outer cochlear hair cells as well as vestibular hair cells61. It plays an important role in hair cell mechanotransduction by regulating tip-link assembly and channel conductance61. Loss of Lhfpl5/Tmhs causes both auditory and vestibular dysfunction and hair cell degeneration61. Mutations in LHFPL5 are associated with the non-syndromic autosomal recessive hearing loss DFNB6762. This study is unique in that they tested whether exosome-associated AAV (exo-AAV) improves viral transduction in the inner ear for AAV1 and AAV9. Additionally, they used self-complementary AAV vector genomes instead of single-stranded genomes used in prior studies. They found that exosome-associated AAV (1x1011 vg) increased hair cell transduction efficiency in vitro for AAV1 (20% AAV1 vs. 50% exo-AAV1) and AAV9 (70% AAV9 vs 100% exo-AAV9). While in vivo transduction of inner hair cells reaches up to 100%, outer hair cell transduction with AAV was approximately 15% with AAV alone and approximately 20-30% with exo-AAV. When exo-AAV1-CBA-Lhfpl5 (2.7x109 vg) was injected into the inner ears of P1-P2 Lhfpl5 knockout mice, partial hearing recovery was observed (up to 30 dB SPL improvement at low frequencies). The vestibular function in the Lhfpl5 knockout mice was also improved after exo-AAV1-CBA-Lhfpl5 treatment, as evidenced by a reduction in head tossing and circling behavior. This was the first study to utilize exosome-associated AAV in inner ear gene replacement.

USH1C (Pan, Askew, Galvin et al., 2017)27

The USH1C gene encodes harmonin, a protein that is present at the tips of stereocilia and functions as a scaffold protein that anchors the upper tip-link63. Loss of harmonin results in reduced mechanotransduction currents and eventually hair cell death64,65. Mutations in USH1C cause a form of Usher syndrome type 1, which is a common cause of deafness-blindness66,67. The knock-in Ush1c mutant mouse which carries an analogous human mutation (Ush1c c.216G>A) is deaf and develops retinal degeneration68. In addition, these mutant mice also exhibit significant vestibular dysfunction, which is also seen in patients with type 1 Usher syndrome69. In a study by Pan et al. (2017), AAV2/Anc80L65 was used to deliver Ush1c cDNA to the knock-in Ush1c mutant mice27. AAV2/Anc80L65-CMV-Ush1c (titer 2x1012 vg/mL, 0.8-1.0 μl) was injected via RWM at age P0-P1. This resulted in average rescue of auditory thresholds to within 20dB of wild-type for low- to mid-frequency hearing, while high-frequency hearing thresholds remained elevated. Balance behavior was also rescued, as evidenced by the reduction in circling behavior, and improvement on the rotarod test27. Cochlear hair cell survival was significantly increased, resulting in nearly 100% of hair cells surviving in the low- to mid-frequency locations, while 80-90% of hair cells in the high-frequency location survived. However, injection at P10-P12 did not rescue any auditory function, which highlights the importance of determining the time interval when there is a therapeutic window for gene delivery to achieve hearing recovery.

USH1G (Emptoz et al., 2017)18

Another gene that is involved with type 1 Usher syndrome is USH1G, which encodes for the protein SANS. SANS is localized at the stereocilia tip and is important for proper hair cell function70. The Ush1g knockout mouse exhibits deafness as well as significant vestibular dysfunction, as evidenced by circling behavior18. The stereocilia bundles in cochlear and vestibular hair cells are abnormal and lack functional tip-links, which are critical for hair cell mechanotransduction. In this study, AAV8-CB6-Ush1g (1x1013 vg/mL, 2μl) was injected into the Ush1g knockout mice (P0-P3) via RWM. The authors found that AAV8-CB6-Ush1g treatment was able to rescue stereocilia bundle morphology in the Ush1g knockout mice Partial hearing improvement was also observed in treated mutant mice (ABR thresholds of ~80-100 dB SPL), though the hearing improvement appears to be short-lived, with progressive hearing loss by approximately 12 weeks postnatally.

USH3A (Geng and Akil, et al., 2017; Dulon et al., 2018; Gyorgy et al., 2019)17,20,21

Clarin-1 is a transmembrane protein that is critical for hair cell stereocilia bundle morphogenesis71,72. Mutations in clarin-1 (CLRN1) are associated with Usher syndrome type 3A73. Clarin-1 is an attractive target for inner ear gene therapy due to the fact that unlike most other genes that cause hearing loss due to loss-of-function mutations, mutations associated with CLRN1 usually cause delayed-onset hearing loss67. This potentially allows for a longer therapeutic window for inner ear gene therapy to act. The first study on Clrn1 gene replacement therapy was performed by Geng et al. (2017)20, where a mouse model of Ush3a was created which develops progressive hearing loss after birth (KO-TgAC1). This was achieved by creating a Clrn1 knockout mouse that carries a transgene containing the Clrn1 cDNA and its 3’ UTR under the control of the Atoh1 3’ enhancer/β-globin basal, which causes significant downregulation of Clrn1 soon after birth74. The authors used both AAV2 and AAV8 to deliver Clrn1 cDNA to neonatal (P1-P3) KO-TgAC1 mutant mice (8.60x1012 and 3.41x1013 vg/mL, respectively). Gene delivery was done through the RWM. They found that while delivery of AAV-smCBA-Clrn1 did not result in hearing improvement, delivery of AAV-smCBA-Clrnl-UTR did result in the delay of the progression of hearing loss, with average hearing improvement of 38 dB SPL up to 150 days postnatally20.

In a second study of Clrnl gene replacement, Dulon et al. (2018) generated two mutant mouse models of Ush3a, one with Clrn1 exon 4 deletion (Clrn1ex4−/−), and the other with postnatal Clrn1 exon 4 deletion restricted to the hair cells (Clrn1ex4fl/fl Myo15-Cre+− The Clrn1ex4−/− mutant mouse has profound hearing loss, whereas the Clrn1ex4fl/fl Myo15-Cre+− mutant mouse develops progressive hearing loss from P15-P60. When AAV2/8-Clrn1 was delivered to P1-P3 Clrn1ex4−/− mutant mice through the RWM, small amount of hearing recovery (~10-15 dB) was observed. Delivery of AAV2/8-Clrn1 into P1-P3 Clrn1ex4fl/fl Myo15-Cre+− mutant mice resulted in greater hearing improvement, with hearing thresholds of ~60-70 dB SPL at P60. Unfortunately hearing loss progresses from P60-P120, likely reflective of continued outer hair cell degeneration. AAV2/8-Clrn1 gene delivery also resulted in improved stereocilia structural preservation compared to untreated Clrn1ex4fl/fl Myo15-Cre+− mutant mice17.

One thing in common for the two above studies is the use of conventional AAVs (AAV2 and AAV8) for inner ear gene delivery, which transduces the inner hair cells at higher rate than outer hair cells. In a third study on Clrn1 gene replacement, a synthetic AAV, AAV9-PHP.B, was used to deliver Clrn1 cDNA to the Clrn1 knockout (Clrn1−/−) mice through the RWM21. Unlike patients with Usher syndrome type 3A, where hearing loss is progressive in nature, the Clrn1 knockout mouse has profound hearing loss throughout life. When AAV9-PHP.B-CBA-Clrn1 (1.8x1011 vg) was injected through the RWM of P1 Clrn1 knockout mice, high level of inner and outer hair cell transduction was achieved. Unfortunately, only partial hearing recovery was observed at low frequencies (4-8 kHz), likely due to a narrow window of therapeutic opportunity in this mouse model. These three studies of Clrnl gene replacement show that the hearing outcomes of inner ear gene therapy can vary greatly depending on the therapeutic window, animal models, or viral vectors used for gene delivery.

SLC26A4 (Kim et al., 2019)75

SLC26A4 encodes pendrin, which is a CI/HCO3 anion exchanger that is critical for fluid homeostasis in the inner ear76-78. Mutations in SLC26A4 cause Pendred syndrome (sensorineural hearing loss and thyroid goiter), which is a common cause of hereditary hearing loss79. In this study, the authors used two mouse models to study Slc26a4 gene replacement therapy: a Slc26a4 knockout mouse (Slc26a4Δ/Δ80 and a Slc26a4 knock-in mouse (Slc26a4m1Dontuh/tm1Dontuh)81. Since Slc26a4 is expressed as early as E11.5 in the mouse endolymphatic sac76, and the expression of Slc26a4 is critical during E16.5-P2 for hearing recovery82, the authors delivered AAV2/1-CMV-Slc26a4 (1.08x1010 vg) to the otocyst of the Slc26a4Δ/Δ and Slc26a4m1Dontuh/tm1Dontuh mutant mice in utero at E12.5. They found that Slc26a4 gene replacement therapy restored pendrin expression in the endolymphatic sac, increased outer hair cell survival, and prevented cochlear hydrops. Slc26a4 gene replacement therapy also improved the ABR thresholds to within 10-20 dB of wild-type mice, and improved endocochlear potential. However, hearing recovery was unstable in the injected mutant mice, with many animals developing fluctuating and progressive hearing loss between 3-11 weeks of age. In addition, vestibular function was not rescued by Slc26a4 gene replacement, as measured by absence of improvement in the rotarod test. The lack of stable hearing recovery and improvement in vestibular function may be due to the fact that pendrin expression was only transient and was only found in the endolymphatic sac, but not in the cochlear and vestibular organs. This could be a result of the viral vector used (AAV2/1), the gene delivery approach (in utero), and/or the biology of Slc26a4 in the mouse inner ear.

OTOF (Al-Moyed et al., 2019; Akil et al., 2019)10,12

A major limitation of using AAV for gene delivery is the fact that packaging capacity for AAV is only approximately 4.2kb, assuming minimal lengths for the ITR, promoter, and poly-A sequences38. This limits the number of candidate genes that can be targeted by AAV-mediated gene replacement. One way to overcome this limitation is by employing a dual-AAV approach, in which a large cDNA is broken into two smaller parts, and the smaller segments of the cDNA are delivered using two separate AAVs83. Two studies applied the dual-AAV approach to deliver otoferlin into the inner ears of otoferlin knockout mice10,12. Otoferlin (OTOF) is expressed primarily in the inner hair cells, and it is involved with synaptic vesicle reformation and exocytosis84. The otoferlin knockout mouse (Otof−/− has profound hearing loss throughout life84. In a study by Al-Moyed et al. (2019), dual-AAV2/6 was used to deliver the two segments of Otof cDNA into the inner ears of otoferlin knockout mice through the RWM. The human β-actin promoter/CMV enhancer was used to drive transgene expression and viral titer was 1.2-1.38 x 1010 vg/μl. Gene delivery was done at P6-P7. They found that inner ear gene delivery resulted in restoration of OTOF expression in approximately 50% of the inner hair cells. Auditory function was partially improved, with ABR thresholds approximately 60-80 dB SPL12.

In another study on otoferlin gene replacement by Akil et al. (2019), Otof segments were delivered using a modified AAV2 where four surface tyrosine residues have been changed to phenylalanine residues (AAV2 quadY-F). A chimeric CMV-CBA promoter was used to drive gene expression and viral titers were 4.5-6.3 x 1012 vg/ml (2μl was delivered in each animal). Gene delivery was performed through the RWM at P10, P17, and P30. The authors found that Otof gene delivery not only resulted in restoration of OTOF expression in the inner hair cells in the Otof knockout mice, it also significantly improved the auditory functions of the treated mutant mice at all three gene delivery time points. The click ABR threshold improved to the level of wild-type animals and lasted up to 20 weeks after gene delivery. These studies demonstrate that large genes may be amenable to gene replacement therapy using the dual-AAV approach. The study by Akil et al. is also the first study to show hearing improvement when inner ear gene delivery is performed after the onset of hearing (P10-P12) in the mouse10.

3. Opportunities for gene replacement therapy as a treatment for hereditary hearing loss:

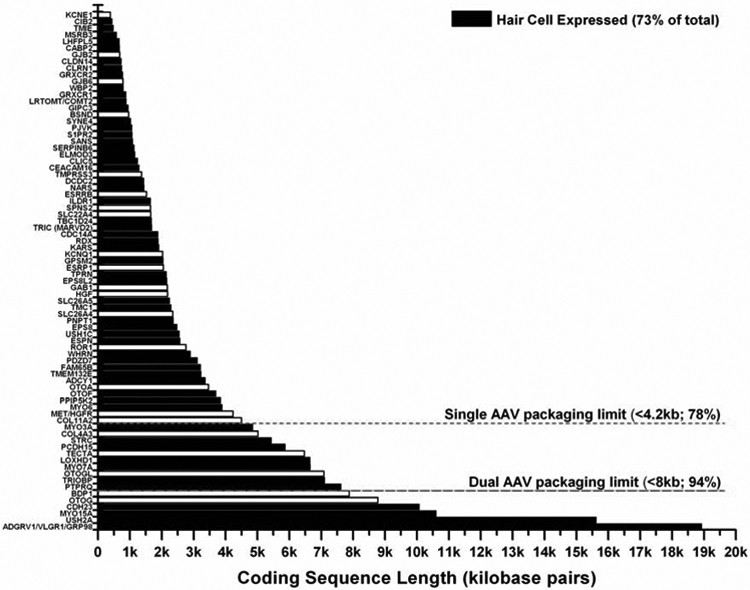

Since 2001, universal newborn hearing screening has been mandatory in all 50 states, and it has resulted in testing of 95% of children born in the US each year (CDC report Williams et al., 2015, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6413a4.htm). Newborn hearing screens are justified both because methods of treatment (e.g. hearing aids, cochlear implants) are available, and it is critical to identify children with hearing loss as early as possible in order to maximize their chances of learning and developing spoken language. Although cochlear implants are imperfect as a replacement for natural hearing, they are highly effective for enabling speech perception and facilitating verbal communication. Average cost of cochlear implantation currently runs around $50,000-$100,000 per ear. If gene therapy can improve upon the sound perception over that of cochlear implants, the biotech/pharma sector can rationalize pricing structures that should incentivize the development of gene therapy for hearing loss. The FDA recently approved Luxturna as the first AAV gene therapy in the US, for which there are an estimated 1,000-2,000 individuals in the US and 6,000 world-wide with an RPE65 gene deficiency that are candidate patients. Congenital blindness has a prevalence of 4 in 10,000 people in developed nations, which is roughly 1/8th the number of individuals with congenital deafness85. Although it is challenging to estimate the number of patients by single genetic target, surely many forms of inherited hearing loss will be attractive targets for companies interested in developing gene therapy treatments. Most (73%) of the identified deafness genes are expressed in the sensory hair cells of the inner ear. Furthermore, many identified deafness genes are under 4kb in length, the size that is currently feasible for AAV delivery in a single vector (Figure 2). Recently developed dual vector systems are now able to split larger genes between two AAV vectors for recombination once delivered to the same cell. Routes of administration are actively being investigated for large animal models and humans86. Compared to the eye, which contains over 100 million photoreceptors, there are just approximately 16,000 hair cells to target in the human cochlea and thus fewer cells to correct for sensory restoration.

Figure 2: Most genes that cause hereditary hearing loss affect mechanosensory hair cells in the cochlea.

This figure lists the genes that are associated with hereditary hearing loss by cDNA size. Most of the genes (73%) that cause hereditary hearing loss affect proper mechanosensory hair cell function (shown in black). The size limitations for single AAV and dual AAV gene delivery are also indicated.

4. Challenges to the translation of gene replacement therapy for hereditary hearing loss:

Genetic heterogeneity and window for therapeutic intervention

There are 300-400 human genetic loci predicted to be associated with hearing loss, where just over 150 deafness genes have been identified (www.hereditaryhearingloss.org). These genes are involved with a wide variety of cellular functions, and variants in most of these genes lead to early-onset hearing loss. It is a daunting task to explore a treatment for each gene, but the design of successful gene replacement therapy will require in-depth understanding of the unique functions of each individual protein and the optimal timing for gene replacement to take place. In many cases, we still do not understand enough about the functions of individual proteins, where they are expressed, and at what stage in development they are necessary. This provides a long list of opportunities to researchers eager to tease apart basic mechanisms. Furthermore, the most clinically treatable cases where gene replacement can be successfully applied will likely involve patients with progressive or delayed-onset hearing loss. This is because in patients with profound congenital hearing loss, the sensory structures of the inner ear may already be damaged at the time of treatment for gene replacement to be effective. Currently, the field has already begun to identify genes causing mild or progressive hearing loss87-90, which provides hope that there are still many genes left to be discovered that are amenable to postnatal treatment.

It is important to remember that while the mouse auditory system has many similarities to human ears in terms of anatomy, function, and genetics, there are some important differences. The most critical difference between the two species is in the timing of inner ear development: the human auditory system is developed by gestational week 1991, whereas the mouse auditory system is not fully developed until ~12 days postnatally92. Since most of the genes that cause recessive hearing loss are necessary early in the development of the inner ear93, it is possible that even though the window of therapeutic opportunity extends post-birth for some genes in mice, the window of opportunity for gene therapy may occur in utero in humans. The greatest potential for human translation of inner ear gene replacement begins with genes where critical inner ear cell types are preserved (e.g. OTOF, VGLUT3), or genes causing post-lingual or progressive hearing loss (e.g. CLRN1) that could be addressed by gene replacement after birth.

Effectiveness of gene delivery

Many of the genes that are involved with autosomal recessive hearing loss encode proteins that are non-secreted and must function within individual cells of the inner ear (e.g. GJB2, TMC1, WHRN). This presents the challenge that the vast majority of an entire cell population must be targeted and corrected with high efficiency by inner ear gene therapy. Therefore, finding the right viral vector with high transduction efficiency is critical for the success of inner ear gene therapy. Different AAV vectors have been shown to transduce various cell types in the inner ear, including hair cells, supporting cells, fibrocytes, mesenchyme, stria vascularis, spiral limbus, and spiral ganglion neurons94. However, most studies indicate that conventional AAVs tend to transduce the inner hair cells in the cochlea with the highest efficiency, and other cells types at much lower efficiency11,13,15,54,95. More recently, several synthetic AAVs have been reported to transduce various inner ear cells with high efficiency21,54,96-98. The higher transduction efficiency of synthetic AAVs to various cell types in the inner ear will likely improve the efficacy of inner ear gene therapy, as illustrated by Tmc1 gene therapy with AAV2/Anc80L65 vs. AAV113,26. Continued research to improve and refine viral transduction in the inner ear will be critical for the future success of inner ear gene therapy.

Surgical approaches for inner ear gene delivery

In most inner ear gene replacement studies that have successfully improved auditory function in mouse models of hereditary hearing loss, the round window or canalostomy approach was used for gene delivery10-13,17,18,20-23,26-28,31. AAV gene therapy can be introduced safely into the perilymphatic fluid of the mammalian inner ear by round window membrane or canalostomy injection routes without disrupting the high potassium endolymphatic space99,100. This avoids perturbation of the polarized ionic environment that creates the endocochlear potential which serves as the battery to drive mechanosensory signaling and is necessary for proper auditory hair cell function95,101,102. In neonatal mice, the otic capsule is cartilaginous. Therefore, a glass micropipette can penetrate directly through the posterior canal wall for gene delivery. Similarly, the bulla in neonatal mice is much easier to open to expose the round window membrane. In contrast, the adult mouse otic capsule is completely ossified. Therefore, the bony covering of the posterior semicircular canal needs to be carefully opened for gene delivery. Similarly, the bulla in adult mouse needs to be carefully removed in order to expose the round window membrane. This makes adult inner ear gene delivery more challenging. The inner ear fluid volume is ~2μl in mice86. Generally, a 1μl volume is sufficient to perfuse reporter vectors throughout the mouse inner ear, and several prior studies have established that a minimum of 1x109 viral genomes (vg) of AAV is necessary for vector transduction, while doses in the range of 1x109 to 1x1010 are typical10-29. The inner fluid volume in rhesus macaque is roughly 60μl in volume, and delivery of 10μl-30μl containing 1x1011 to 1x1012 viral genomes of AAV vector have been shown to effectively transduce inner ear hair cells21,86. In addition, delivery of up to 30μl of fluid volume in the rhesus macaque inner ear, via either the round window or the stapedotomy, has been shown to be safe, with no adverse effect on the auditory and vestibular functions, as measured by auditory brainstem responses and vestibulo-ocular reflexes, respectively86.

Several surgical approaches are currently in use to access the human inner ear. The round window approach is commonly used for cochlear implantation103. Surgical procedures to access all three semicircular canals have been described: the superior semicircular canal is accessed for superior semicircular canal dehiscence repair104; the posterior semicircular canal is accessed for plugging in patients with intractable benign positional vertigo105; and the horizontal semicircular canal is accessed during fenestration procedure for otosclerosis (which has been supplanted by stapedotomy)106 Stapedotomy, commonly used to treat otosclerosis, offers access to the vestibule107. In addition, the endolymphatic sac is commonly accessed for endolymphatic shunt placement in patients with Meniere disease who suffer from intractable vertigo (though the efficacy of this surgical procedure for controlling vertigo is highly controversial)108. The human inner ear fluid volume is roughly ~190 μl86. In the “Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy for CGF166 in Patients with Unilateral or Bilateral Severe-to-Profound Hearing Loss” clinical trial (NCT02132130, ClinicalTrials.gov), where the human Atonal transcription factor HATH1 cDNA is delivered to the inner ears of patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss using an adenovirus (AdV5) vector, 60 μl is injected through the stapedotomy approach. While the results of this study are unavailable at the time of this writing, no significant adverse side-effects have been reported in study patients according to the principal investigator (Dr. Hinrich Staecker). It remains to be seen which surgical approach would be the best for AAV gene delivery in human inner ears.

Safety and toxicity

The inner ear is encased in bone and relatively isolated from the rest of the body, making it both an attractive target and a challenge for gene therapy. While direct delivery of vectors to the inner ear fluid can result in distribution along the cochlear spiral, in animal models the vector can also be communicated into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), transducing the brain as well as transducing the opposite ear via a patent cochlear aqueduct27,54. Off-target administration may be less of an issue in humans since the human cochlear aqueduct is usually not completely patent109. Many hearing loss genes are unique to hair cells and require a complex protein environment to function, which means off-target functioning should be limited in non-hair cells. However, ectopic expression of ion channel or gap junction proteins could be detrimental if expressed by the wrong cell types. Theoretically, hair cells could be electrically silenced by expressing gap junction or channel proteins that ionically couple them to nearby supporting cells or the extracellular fluid. Additionally, the same issue has the potential to affect generation and maintenance of the endocochlear potential, as well as neuronal action potential generation and propagation. Therefore, when working with a specific subset of genes it may be necessary to ensure that the viral vector is restricted to expressing the transgene only in targeted cell types in order to avoid off-target transgene expression. One approach is to limit off-target expression or functioning of therapeutic genes using cell-specific microRNA binding elements that are incorporated into the vector cassette and can silence gene expression in cells expressing that specific microRNA110. This approach is facilitated by recently developed single-cell transcriptomic databases specific to the inner ear (gEAR portal, https://umgear.org/; and the SHIELD portal, https://shield.hms.harvard.edu/) to search for and identify novel cell-specific microRNAs. Another method to regulate gene expression is through the use of a target cell-specific promoter or enhancer. Currently, most vectors make use of ubiquitous promoters like the CMV or CBA promoter with gene expression activity that is not restricted to specific cell types. Limited inner ear cell-specific promoters have been identified, especially ones that are small enough to fit within an AAV transgene cassette while leaving enough room for the therapeutic transgene111. This is due to the challenge of identifying tissue specific enhancers and promoters, which can be found hundreds of kilobases upstream or downstream of the gene of interest. However, newly developed bioinformatics tools and experimental techniques have enabled powerful reductionist approaches to interrogate up to a megabase of DNA for enhancer/promoter function112-114. Finally, from a dosage perspective of gene expression, recent studies have demonstrated that strong constitutive promoters in the eye can have detrimental consequences on cell survival in the retina presumably due to protein over expression115. This effect can be mitigated by decreasing the overall vector dose but will likely come at the expense of decreased numbers of corrected cells. Therefore, control over protein expression using gene appropriate promoters or enhancers is the most attractive method to maximize the number of corrected cells while minimizing toxicity from both over-expression and off-target expression. Continued research in these areas is necessary to allow investigators to target specific cell types in the mammalian inner ear without off-target transgene expression, in order to improve the safety of inner ear gene therapy.

Longevity of therapeutic effects

Even though gene replacement therapy has been successfully applied to several mouse models of hereditary hearing loss, the longevity of the therapeutic effect varies greatly, with many studies showing hearing deterioration after a couple of months and others showing sustained hearing improvement up to 12 months of age. The longevity of various inner ear gene replacement therapy is likely dependent on the pathophysiology of hearing loss associated with specific genes, as well as the animal models used in these studies. Whether the longevity of therapeutic effectiveness from mouse studies can be extrapolated to humans with hearing loss remains to be seen. Since many of the cell types in the mammalian inner ear are post-mitotic and lack the ability to regenerate116, this should theoretically allow the transduced target cells to have persistent transgene expression throughout the cells’ entire lifespan without the need for re-administration. However, should the need for gene therapy readministration arise, its efficacy may be reduced due the production of neutralizing antibodies against the viral vector and/or transgene117.These considerations should be kept in mind when designing future inner ear gene therapy clinical trials.

Diagnosis and clinical translation

One of the major barriers to the translation of inner ear gene therapy to patients with hereditary hearing loss is the fact that genetic testing for hearing loss is presently not commonly performed. Currently, successful identification of genetic causes of hearing loss is achieved in only 40%-50% of the tested patients118-120, leaving patients without answers and those researching potential treatments without a solid estimate of the size of the patient pool. Early identification of the underlying genetic cause of hearing loss will allow clinicians to collect data on the natural history of hearing loss caused by specific mutations. This information is critical for the determination of the optimal therapeutic window for inner ear gene delivery. As the inner ear gene replacement animal studies reviewed above illustrate, identification of the appropriate therapeutic window for gene delivery is a key factor for successful hearing recovery. Another major barrier for translating inner ear gene therapy to patients is the fact that there is currently no reliable tool to monitor the level of cell survival in the inner ear in real time.

In order for inner ear gene therapy to be successful, the targeted cell type in the inner ear must be viable at the time of gene delivery. The existing imaging modalities do not have the required resolution to yield this critical information in real time. However, improvements are being made in this area121,122, and electrophysiological measures may also be helpful to monitor the status of the inner ear (e.g. distortion product otoacoustic emissions, electrocochleography).

5. Conclusions:

Over the past few years, several studies have demonstrated that inner ear gene replacement therapy can be used to improve auditory function in mouse models of hereditary hearing loss. These studies targeted genes that mediate a wide range of inner ear cellular functions (Figure 1), including synaptic transmission (e.g. Vglut3, Otof), ion channels (e.g. Tmc1, Kcnq1, Slc26a4), gap junctions (e.g. Gjb2, Gjb6), peroxisome proliferation (e.g. Pjvk), stereocilia function and maintenance (e.g. Whrn, Lhfpl5, Ush1c, Ush1g, Clrn1), and defense against oxidative stress (MsrB3). The fact that inner ear gene replacement therapy has been successfully applied to these genes with diverse roles in the mammalian inner ear illustrates the great potential for inner ear gene replacement therapy as a treatment for hearing loss caused by different etiologies. However, many challenges still lie ahead for the successful translation of gene replacement therapy to patients with hereditary hearing loss. A deep understanding of the gene target is required for assessing the therapeutic window for effective inner ear gene delivery. Viral capsid engineering will hopefully continue to provide the field with viral vectors that have high transduction efficiency and specificity for the targeted cell types. The use of cell-specific promoters and microRNAs can control the safety and dosage of gene expression while further limiting unwanted off-target transgene expression. In addition, better imaging and electrophysiological tests will eventually allow investigators to select the appropriate patients for inner ear gene replacement therapy administration and monitor its efficacy in real time. Given the recent FDA approval of gene therapy treatments for Leber’s congenital amaurosis and spinal muscular atrophy, it is our hope that there will be new gene therapy treatments available for patients with hereditary hearing loss in the foreseeable future.

Highlights.

Over the past few years, several studies have demonstrated that inner ear gene replacement therapy can be used to improve auditory function in mouse models of hereditary hearing loss.

Because of its strong biosafety profile, adeno-associated virus (AAV) was the viral vector of choice for the majority of these studies.

Inner ear gene replacement therapy has been successfully applied to genes with diverse roles in the mammalian inner ear.

A deep understanding of the gene target is required for assessing the therapeutic window for effective inner ear gene delivery.

Viral capsid engineering can develop viral vectors that have high transduction efficiency and specificity for the targeted cell types.

The use of cell-specific promoters and microRNAs can limit unwanted off-target transgene expression.

Better imaging and electrophysiologic tests will allow investigators to select the appropriate patients for inner ear gene replacement therapy administration and monitor its efficacy in real time.

Acknowledgement:

We thank Dr. Lisa Cunningham and Dr. Tom Friedman for reading and commenting on the manuscript. This work is supported by NIDCD Division of Intramural Research Grant DC000082-02 to W.W.C., an American Hearing Research Foundation grant and Pfizer-North Carolina Biotechnology Center Distinguished Post-doctoral Fellowship in Gene Therapy to C.A..

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Vohr B Overview: Infants and children with hearing loss-part I. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 9, 62–64, doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10070 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vohr B Infants and children with hearing loss--part 2: Overview. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 9, 218–219, doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10082 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morton CC & Nance WE Newborn hearing screening--a silent revolution. N Engl J Med 354, 2151–2164, doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050700 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koffler T, Ushakov K & Avraham KB Genetics of Hearing Loss: Syndromic. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 48, 1041–1061, doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2015.07.007 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azaiez H et al. Genomic Landscape and Mutational Signatures of Deafness-Associated Genes. Am J Hum Genet 103, 484–497, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.08.006 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raviv D, Dror AA & Avraham KB Hearing loss: a common disorder caused by many rare alleles. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1214, 168–179, doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05868.x (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alford RL et al. American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guideline for the clinical evaluation and etiologic diagnosis of hearing loss. Genet Med 16, 347–355, doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.2 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickles JO Auditory pathways: anatomy and physiology. Handb Clin Neurol 129, 3–25, doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-62630-1.00001-9 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiam NT, Caldwell MT & Limb CJ What Does Music Sound Like for a Cochlear Implant User? Otol Neurotol 38, e240–e247, doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001448 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akil O et al. Dual AAV-mediated gene therapy restores hearing in a DFNB9 mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 4496–4501, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1817537116 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akil O et al. Restoration of hearing in the VGLUT3 knockout mouse using virally mediated gene therapy. Neuron 75, 283–293, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.05.019 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Moyed H et al. A dual-AAV approach restores fast exocytosis and partially rescues auditory function in deaf otoferlin knock-out mice. EMBO Mol Med 11, doi: 10.15252/emmm.201809396 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Askew C et al. Tmc gene therapy restores auditory function in deaf mice. Sci Transl Med 7, 295ra108, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab1996 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang Q et al. Virally mediated Kcnq1 gene replacement therapy in the immature scala media restores hearing in a mouse model of human Jervell and Lange-Nielsen deafness syndrome. EMBO Mol Med 7, 1077–1086, doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404929 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chien WW et al. Gene Therapy Restores Hair Cell Stereocilia Morphology in Inner Ears of Deaf Whirler Mice. Mol Ther 24, 17–25, doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.150 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delmaghani S et al. Hypervulnerability to Sound Exposure through Impaired Adaptive Proliferation of Peroxisomes. Cell 163, 894–906, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.023 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dulon D et al. Clarin-1 gene transfer rescues auditory synaptopathy in model of Usher syndrome. J Clin Invest 128, 3382–3401, doi: 10.1172/JCI94351 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emptoz A et al. Local gene therapy durably restores vestibular function in a mouse model of Usher syndrome type 1G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 9695–9700, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708894114 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao X et al. Treatment of autosomal dominant hearing loss by in vivo delivery of genome editing agents. Nature 553, 217–221, doi: 10.1038/nature25164 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geng R et al. Modeling and Preventing Progressive Hearing Loss in Usher Syndrome III. Sci Rep 7, 13480, doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13620-9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gyorgy B et al. Gene Transfer with AAV9-PHP.B Rescues Hearing in a Mouse Model of Usher Syndrome 3A and Transduces Hair Cells in a Non-human Primate. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 13, 1–13, doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.11.003 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gyorgy B et al. Rescue of Hearing by Gene Delivery to Inner-Ear Hair Cells Using Exosome-Associated AAV. Mol Ther 25, 379–391, doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.12.010 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isgrig K et al. Gene Therapy Restores Balance and Auditory Functions in a Mouse Model of Usher Syndrome. Mol Ther 25, 780–791, doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.01.007 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim MA et al. Methionine Sulfoxide Reductase B3-Targeted In Utero Gene Therapy Rescues Hearing Function in a Mouse Model of Congenital Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Antioxid Redox Signal 24, 590–602, doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6442 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lentz JJ et al. Rescue of hearing and vestibular function by antisense oligonucleotides in a mouse model of human deafness. Nat Med 19, 345–350, doi: 10.1038/nm.3106 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nist-Lund CA et al. Improved TMC1 gene therapy restores hearing and balance in mice with genetic inner ear disorders. Nat Commun 10, 236, doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08264-w (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan B et al. Gene therapy restores auditory and vestibular function in a mouse model of Usher syndrome type 1c. Nat Biotechnol 35, 264–272, doi: 10.1038/nbt.3801 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shibata SB et al. RNA Interference Prevents Autosomal-Dominant Hearing Loss. Am J Hum Genet 98, 1101–1113, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.03.028 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu Q et al. Virally expressed connexin26 restores gap junction function in the cochlea of conditional Gjb2 knockout mice. Gene Ther 21, 71–80, doi: 10.1038/gt.2013.59 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang KW Genetics of Hearing Loss--Nonsyndromic. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 48, 1063–1072, doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2015.06.005 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gyorgy B et al. Allele-specific gene editing prevents deafness in a model of dominant progressive hearing loss. Nat Med 25, 1123–1130, doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0500-9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naso MF, Tomkowicz B, Perry WL 3rd & Strohl WR Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) as a Vector for Gene Therapy. BioDrugs 31, 317–334, doi: 10.1007/s40259-017-0234-5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samulski RJ & Muzyczka N AAV-Mediated Gene Therapy for Research and Therapeutic Purposes. Annu Rev Virol 1, 427–451, doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085355 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J et al. Concatamerization of adeno-associated virus circular genomes occurs through intermolecular recombination. J Virol 73, 9468–9477 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCarty DM, Young SM Jr. & Samulski RJ Integration of adeno-associated virus (AAV) and recombinant AAV vectors. Annu Rev Genet 38, 819–845, doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143717 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao G et al. Clades of Adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J Virol 78, 6381–6388, doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6381-6388.2004 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee EJ, Guenther CM & Suh J Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Vectors: Rational Design Strategies for Capsid Engineering. Curr Opin Biomed Eng 7, 58–63, doi: 10.1016/j.cobme.2018.09.004 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu Z, Yang H & Colosi P Effect of genome size on AAV vector packaging. Mol Ther 18, 80–86, doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.255 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lundstrom K Viral Vectors in Gene Therapy. Diseases 6, doi: 10.3390/diseases6020042 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seal RP et al. Sensorineural deafness and seizures in mice lacking vesicular glutamate transporter 3. Neuron 57, 263–275, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.032 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruel J et al. Impairment of SLC17A8 encoding vesicular glutamate transporter-3, VGLUT3, underlies nonsyndromic deafness DFNA25 and inner hair cell dysfunction in null mice. Am J Hum Genet 83, 278–292, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.07.008 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crispino G et al. In vivo genetic manipulation of inner ear connexin expression by bovine adeno-associated viral vectors. Sci Rep 7, 6567, doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06759-y (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang EH, Van Camp G & Smith RJ The role of connexins in human disease. Ear Hear 24, 314–323, doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000079801.55588.13 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kikuchi T, Kimura RS, Paul DL & Adams JC Gap junctions in the rat cochlea: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Anat Embryol (Berl) 191, 101–118, doi: 10.1007/bf00186783 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahmad S, Chen S, Sun J & Lin X Connexins 26 and 30 are co-assembled to form gap junctions in the cochlea of mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 307, 362–368, doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01166-5 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith RJH & Jones MKN in GeneReviews((R)) (eds Adam MP et al). (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahmad S et al. Restoration of connexin26 protein level in the cochlea completely rescues hearing in a mouse model of human connexin30-linked deafness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 1337–1341, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606855104 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wangemann P K+ cycling and the endocochlear potential. Hear Res 165, 1–9, doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00279-4 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawashima Y et al. Mechanotransduction in mouse inner ear hair cells requires transmembrane channel-like genes. J Clin Invest 121, 4796–4809, doi: 10.1172/JCI60405 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pan B et al. TMC1 Forms the Pore of Mechanosensory Transduction Channels in Vertebrate Inner Ear Hair Cells. Neuron 99, 736–753 e736, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.07.033 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pan B et al. TMC1 and TMC2 are components of the mechanotransduction channel in hair cells of the mammalian inner ear. Neuron 79, 504–515, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.019 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marcotti W, Erven A, Johnson SL, Steel KP & Kros CJ Tmc1 is necessary for normal functional maturation and survival of inner and outer hair cells in the mouse cochlea. J Physiol 574, 677–698, doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095661 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hilgert N et al. Mutation analysis of TMC1 identifies four new mutations and suggests an additional deafness gene at loci DFNA36 and DFNB7/11. Clin Genet 74, 223–232, doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01053.x (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Landegger LD et al. A synthetic AAV vector enables safe and efficient gene transfer to the mammalian inner ear. Nat Biotechnol 35, 280–284, doi: 10.1038/nbt.3781 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mburu P et al. Defects in whirlin, a PDZ domain molecule involved in stereocilia elongation, cause deafness in the whirler mouse and families with DFNB31. Nat Genet 34, 421–428, doi: 10.1038/ng1208 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ebermann I et al. A novel gene for Usher syndrome type 2: mutations in the long isoform of whirlin are associated with retinitis pigmentosa and sensorineural hearing loss. Hum Genet 121, 203–211, doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0304-0 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Delmaghani S et al. Mutations in the gene encoding pejvakin, a newly identified protein of the afferent auditory pathway, cause DFNB59 auditory neuropathy. Nat Genet 38, 770–778, doi: 10.1038/ng1829 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kwon TJ et al. Methionine sulfoxide reductase B3 deficiency causes hearing loss due to stereocilia degeneration and apoptotic cell death in cochlear hair cells. Hum Mol Genet 23, 1591–1601, doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt549 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ahmed ZM et al. Functional null mutations of MSRB3 encoding methionine sulfoxide reductase are associated with human deafness DFNB74. Am J Hum Genet 88, 19–29, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.010 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bedrosian JC et al. In vivo delivery of recombinant viruses to the fetal murine cochlea: transduction characteristics and long-term effects on auditory function. Mol Ther 14, 328–335, doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.04.003 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiong W et al. TMHS is an integral component of the mechanotransduction machinery of cochlear hair cells. Cell 151, 1283–1295, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.041 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shabbir MI et al. Mutations of human TMHS cause recessively inherited non-syndromic hearing loss. J Med Genet 43, 634–640, doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.039834 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lefevre G et al. A core cochlear phenotype in USH1 mouse mutants implicates fibrous links of the hair bundle in its cohesion, orientation and differential growth. Development 135, 1427–1437, doi: 10.1242/dev.012922 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grillet N et al. Harmonin mutations cause mechanotransduction defects in cochlear hair cells. Neuron 62, 375–387, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.006 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Michalski N et al. Harmonin-b, an actin-binding scaffold protein, is involved in the adaptation of mechanoelectrical transduction by sensory hair cells. Pflugers Arch 459, 115–130, doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0711-x (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kimberling WJ et al. Frequency of Usher syndrome in two pediatric populations: Implications for genetic screening of deaf and hard of hearing children. Genet Med 12, 512–516, doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181e5afb8 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Friedman TB, Schultz JM, Ahmed ZM, Tsilou ET & Brewer CC Usher syndrome: hearing loss with vision loss. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 70, 56–65, doi: 10.1159/000322473 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lentz JJ et al. Deafness and retinal degeneration in a novel USH1C knock-in mouse model. Dev Neurobiol 70, 253–267, doi: 10.1002/dneu.20771 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eppsteiner RW & Smith RJ Genetic disorders of the vestibular system. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 19, 397–402, doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32834a9852 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yan J, Pan L, Chen X, Wu L & Zhang M The structure of the harmonin/sans complex reveals an unexpected interaction mode of the two Usher syndrome proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 4040–4045, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911385107 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Geng R et al. Usher syndrome IIIA gene clarin-1 is essential for hair cell function and associated neural activation. Hum Mol Genet 18, 2748–2760, doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp210 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Geng R et al. The mechanosensory structure of the hair cell requires clarin-1, a protein encoded by Usher syndrome III causative gene. J Neurosci 32, 9485–9498, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0311-12.2012 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Joensuu T et al. Mutations in a novel gene with transmembrane domains underlie Usher syndrome type 3. Am J Hum Genet 69, 673–684, doi: 10.1086/323610 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lumpkin EA et al. Math1-driven GFP expression in the developing nervous system of transgenic mice. Gene Expr Patterns 3, 389–395 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim MA et al. Gene therapy for hereditary hearing loss by SLC26A4 mutations in mice reveals distinct functional roles of pendrin in normal hearing. Theranostics 9, 7184–7199, doi: 10.7150/thno.38032 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim HM & Wangemann P Epithelial cell stretching and luminal acidification lead to a retarded development of stria vascularis and deafness in mice lacking pendrin. PLoS One 6, e17949, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017949 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakaya K et al. Lack of pendrin HCO3- transport elevates vestibular endolymphatic [Ca2+] by inhibition of acid-sensitive TRPV5 and TRPV6 channels. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292, F1314–1321, doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00432.2006 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wangemann P et al. Loss of cochlear HCO3- secretion causes deafness via endolymphatic acidification and inhibition of Ca2+ reabsorption in a Pendred syndrome mouse model. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292, F1345–1353, doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00487.2006 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hilgert N, Smith RJ & Van Camp G Forty-six genes causing nonsyndromic hearing impairment: which ones should be analyzed in DNA diagnostics? Mutat Res 681, 189–196, doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.08.002 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Everett LA et al. Targeted disruption of mouse Pds provides insight about the inner-ear defects encountered in Pendred syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 10, 153–161, doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.2.153 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lu YC et al. Establishment of a knock-in mouse model with the SLC26A4 c.919-2A>G mutation and characterization of its pathology. PLoS One 6, e22150, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022150 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Choi BY et al. Mouse model of enlarged vestibular aqueducts defines temporal requirement of Slc26a4 expression for hearing acquisition. J Clin Invest 121, 4516–4525, doi: 10.1172/JCI59353 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dyka FM, Boye SL, Chiodo VA, Hauswirth WW & Boye SE Dual adeno-associated virus vectors result in efficient in vitro and in vivo expression of an oversized gene, MYO7A. Hum Gene Ther Methods 25, 166–177, doi: 10.1089/hgtb.2013.212 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roux I et al. Otoferlin, defective in a human deafness form, is essential for exocytosis at the auditory ribbon synapse. Cell 127, 277–289, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.040 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Solebo AL, Teoh L & Rahi J Epidemiology of blindness in children. Arch Dis Child 102, 853–857, doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-310532 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dai C et al. Rhesus Cochlear and Vestibular Functions Are Preserved After Inner Ear Injection of Saline Volume Sufficient for Gene Therapy Delivery. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 18, 601–617, doi: 10.1007/s10162-017-0628-6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bowl MR et al. A large scale hearing loss screen reveals an extensive unexplored genetic landscape for auditory dysfunction. Nat Commun 8, 886, doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00595-4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ingham NJ et al. Mouse screen reveals multiple new genes underlying mouse and human hearing loss. PLoS Biol 17, e3000194, doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000194 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lewis MA et al. Whole exome sequencing in adult-onset hearing loss reveals a high load of predicted pathogenic variants in known deafness-associated genes and identifies new candidate genes. BMC Med Genomics 11, 77, doi: 10.1186/s12920-018-0395-1 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Potter PK et al. Novel gene function revealed by mouse mutagenesis screens for models of age-related disease. Nat Commun 7, 12444, doi: 10.1038/ncomms12444 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hepper PG & Shahidullah BS Development of fetal hearing. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 71, F81–87, doi: 10.1136/fn.71.2.f81 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shnerson A & Willott JF Ontogeny of the acoustic startle response in C57BL/6J mouse pups. J Comp Physiol Psychol 94, 36–40, doi: 10.1037/h0077648 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]