Abstract

Hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 (HCA2) is vital for sensing intermediates of metabolism, including β-hydroxybutyrate and butyrate. It also regulates profound anti-inflammatory effects in various tissues, indicating that HCA2 may serve as an essential therapeutic target for mediating inflammation-associated diseases. Butyrate and niacin, endogenous and exogenous ligands of HCA2, have been reported to play an essential role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis. HCA2, predominantly expressed in diverse immune cells, is also present in intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), where it regulates the intricate communication network between diet, microbiota, and immune cells. This review summarizes the physiological role of HCA2 in intestinal homeostasis and its pathological role in intestinal inflammation and cancer.

Keywords: HCA2, intestinal homeostasis, anti-inflammatory, intestinal inflammation, colon cancer, mucosal immunity, microbiota

Introduction

The intestinal tract is an organ system with specialized architecture that functions to digest food, and extract and absorb energy and nutrients. It also secretes over 20 different hormones and harbors more than 640 different species of bacteria (1). Physiological and pathophysiological events that trigger the breakdown of intestinal homeostasis negatively impact intestinal health, and may result in intestinal disorders including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and colitis-associated cancer. IBD is a chronic and life-threating disease characterized by prolonged inflammation of the digestive tract (2, 3). IBD encompasses two conditions, Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Crohn's disease can affect any part and layer of the gastrointestinal tract, while ulcerative colitis is usually limited to the innermost layer of the colon and rectum (4). Both Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis are characterized by episodes of fatigue, abdominal cramping, rectal bleeding, diarrhea, weight loss, and the influx of immune cells that produce cytokines, proteolytic enzymes, and free radicals (5, 6). Patients with IBD are at increased risk of developing colitis-associated cancer which is difficult to treat and has high mortality (>50%) (7, 8). In 2015, an estimated 1.3% of US adults reported living with IBD, with cases increasing worldwide (9, 10). The global spread of IBD is associated with the host genetic background, intestinal microbiota, diets, environments and immunological dysregulation (4, 11, 12).

The intestinal tract represents the largest compartment of the immune system in the body (13), with intestinal health implicated in controlling disease development not only within itself but also throughout the body. To maintain intestinal homeostasis, a multi-pronged approach including the immune system, microbial ecosystem and diet is necessary. A versatile receptor, hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 (HCA2), is capable of both nutrient sensing and immunomodulation, lending to its popularity as a potential target for the promotion of intestine health.

In 1993, HCA2 was identified as an orphan receptor (GPR109A) (14, 15), and later described in mice as a “protein upregulated in macrophages by interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)” (PUMA-G) (16). In 2003, several studies reported that HCA2 is a receptor for niacin and functions to mediate its antilipolytic effects in adipocytes (17–19). Benyó et al. and Hanson et al. subsequently demonstrated that binding of niacin to HCA2 on Langerhans cells and keratinocytes is also responsible for the niacin-induced cutaneous flushing reaction, involving release of prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) (20, 21). In 2005, the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate (β-OHB) was identified as an endogenous ligand of HCA2 (22). This resulted in the deorphanization of the receptor, which was subsequently renamed hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 (HCA2) (23). Most recently, butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) bacterial product in the colon lumen generated at high concentrations (10–20 mM) from dietary fiber fermentation, was recognized as an endogenous ligand of HCA2 (24). Butyrate activation of HCA2 plays an important role in the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis (24). New synthetic ligands of HCA2 have been developed, such as acipimox, GSK256073 and derivatives of pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid or cyclopentapyrazole (25–27).

HCA2 is widely expressed in various tissues and cell types, including adipose tissue, spleen, lung, lymph node and intestine. HCA2 is predominantly expressed not only in both white and brown adipocytes, but also in diverse immune cells, including dendritic cells (DCs), monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils and epidermal Langerhans cells, but not lymphocytes (16, 18, 21, 28, 29). Interestingly, several cytokines show the ability to regulate the expression of HCA2 in immune cells. HCA2 expression is upregulated in macrophages and monocytes after IFN-γ treatment (16), and the expression of HCA2 in macrophages is significantly increased by proinflammatory stimulants lipopolysaccharide (LPS), interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-1β (30). Colony-stimulating factor 2 (CSF2) increases HCA2 expression level in neutrophils (29). HCA2 is also present in intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), retinal pigment epithelium, hepatocytes, keratinocytes and microglia (21, 31–34). Notably, both mRNA and protein levels of HCA2 in IECs are drastically reduced in germ-free mice compared to conventional mice, due to the absence of gut bacteria. These changes are reversed when the intestinal tract of germ-free mice is re-colonized (35).

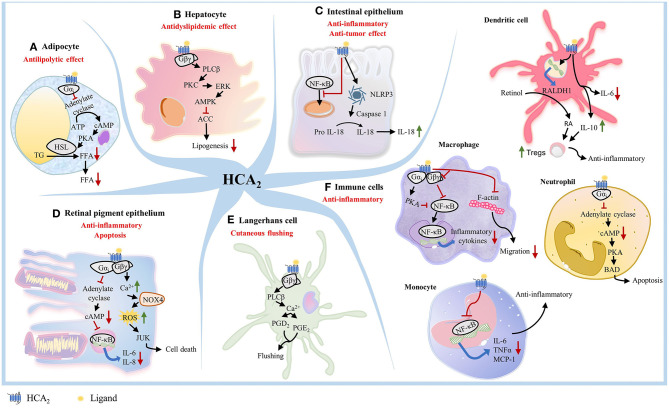

While the anti-lipolytic effects of HCA2 are well-known, more recent studies have demonstrated that activation of HCA2 by endogenous and exogenous ligands is associated with anti-inflammatory effects in numerous disease states (25, 31, 36–41). Early studies showed that activation of HCA2 in various cell types could trigger different downstream signaling events and effects (26) (Figures 1A–F). In adipocytes, activation of HCA2 inhibits lipolysis (18, 42, 43) (Figure 1A). In hepatocytes, HCA2 mediates hepatic de novo lipogenesis and decreases lipid accumulation in liver (44, 45) (Figure 1B). In IECs, ligand binding to HCA2 activates NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, which promotes the maturation of IL-18 for secretion (46, 47) (Figure 1C). IL-18 is a critical effector molecule in intestinal disorders and is required for IEC proliferation (48). HCA2 also suppresses basal and LPS-induced nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) activation in normal and cancer colonocytes (24) (Figure 1C). In retinal pigment epithelium, HCA2 exerts dual effects depending on the concentration of the agonist. 4-hydroxynonenal, an HCA2 agonist, can induce either an anti-inflammatory response or apoptosis (49) (Figure 1D). In Langerhans cells, HCA2 causes cutaneous flushing reaction (20, 21) (Figure 1E). In macrophages, activation of HCA2 exerts an anti-inflammatory effect (50, 51) (Figure 1F). HCA2 also represses chemokine-induced migration of macrophages (30) (Figure 1F). HCA2 shows anti-inflammatory effects in microglia and human monocytes (52–54) (Figure 1F). In DCs, HCA2 activation decreases IL-6 levels and increases IL-10 levels and upregulates expression of RALDH1, which synthesizes retinoic acid (RA) from retinol. RA is necessary for promoting regulatory T cells (Tregs) function and proliferation, especially in the gut in both murine and human DCs (55–57) (Figure 1F). In neutrophils, niacin-mediated HCA2 activation increases Bcl-2 associated agonist of cell death (BAD) levels, a pro-apoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family (58) (Figure 1F). Collectively, these studies clearly demonstrate that HCA2 plays a critical role in nutrient sensing and host protection against pro-inflammatory insults in multiple cell types using various signaling mechanisms.

Figure 1.

HCA2 triggers different downstream signaling pathway in different cell types. (A) In adipocytes, activation of HCA2 triggers a Gαi-mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase activity, which leads to lower intracellular cAMP levels, reduced protein kinase A (PKA) activity, and further reduces the activity of hormone sensitive lipase (HSL), an important lipolytic enzyme. This inhibition of lipolysis results in a decreased release of free fatty acids into the circulation. (B) In hepatocytes, activation of HCA2 mediates the protein kinase C (PKC)-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway, leading to phosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and inhibition of acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC). This results in an inhibition of hepatic de novo lipogenesis and a remarkable decrease of lipid accumulation in liver. (C) In colonocytes, ligand binding to HCA2 suppresses NF-κB activation and activates NLRP3 inflammasome, which recruits caspase-1 and promotes the maturation of IL-18 for secretion. (D) In retinal pigment epithelium, HCA2 exerts either an anti-inflammatory response through the Gαi/cAMP/NF-κB pathway, or apoptosis through the Gβγ/Ca2+/NOX4/ROS/JNK pathway. (E) Within Langerhans cells, HCA2-mediated Gαi activation primarily results in the Gβγ-complex released from activated Gαi, thereby increasing intracellular calcium concentration by mobilizing Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum and ultimately driving the formation of PGD2 and PGE2, which are released to the dermal layer and cause cutaneous flushing reaction. (F) In macrophages, activation of HCA2 involves inhibition of NF-κB, thereby exerting an anti-inflammatory effec. HCA2 activation in macrophages also represses F-actin and blocks Gβγ signaling to inhibit chemokine-induced migration of macrophages. HCA2 also shows anti-inflammatory effects in Parkinson's disease models by inhibiting the phosphorylation of the NF-κB p65 signaling pathway in microglia. HCA2 suppresses LPS-induced NF-κB activation in human monocytes, resulting in decreased transcription of IL-6, TNFα, and MCP-1. In DCs, HCA2 activation decreases IL-6 level and increases IL-10 level, also upregulates expression of RALDH1, which synthesizes RA from retinol. RA and IL-10 promote Treg cell proliferation. In neutrophils, niacin-mediated HCA2 activation inhibits PKA activity and subsequently increase BAD levels, which drives apoptosis of neutrophils.

Intestinal Homeostasis and HCA2: Immune Cells, Intestinal Epithelium, Microbiome, and Metabolites

The intestinal tract, comprised of small intestine, large intestine/colon, and rectum, is the central location for nutrient and water absorption. It harbors more than 1013 microorganisms, contains over 20 different hormones, and serves as the single largest immune compartment in the body (13, 59). Consequently, building and maintaining a homeostatic intestinal tract is a highly complex and broad concept that encompasses a multi-disciplinary approach including the immune system, host cells, gut microbiota and nutrients. Further complexity arises from the mutual interactions between the intestinal tract and other organ systems.

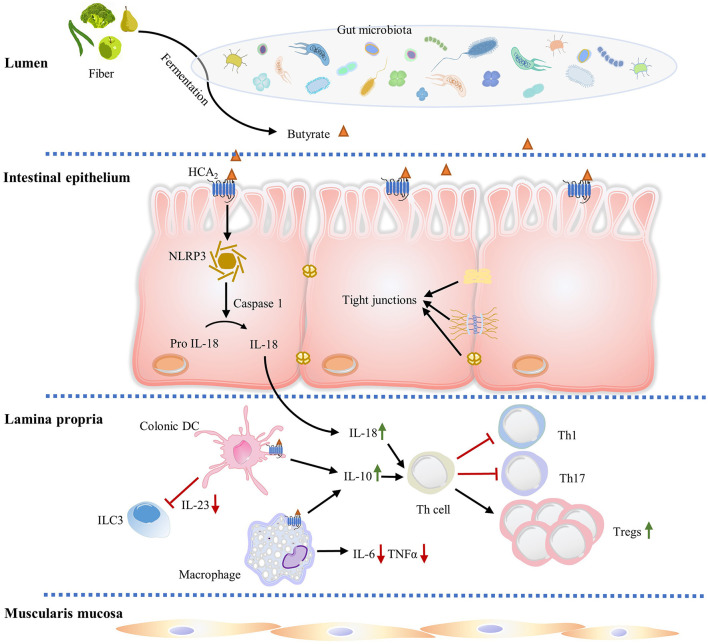

The intestinal mucosa, a crucial site of innate and adaptive immune regulation, is comprised of IECs, lamina propria and muscularis mucosa (Figure 2). IECs are specialized epithelia comprised of many different cell types: epithelial stem cells which continuously self-renew by dividing and generate all differentiated intestinal cell types, enterocytes which absorb water and nutrients, goblet cells which secrete mucins to form a mucus layer boundary between the gut microbiota and host tissue, Paneth cells which secrete anti-microbial peptides, enteroendocrine cells which secrete hormones and cytokines capable of systemic or local effects, and microfold cells (M cells) which connect to the intestinal lymphoid follicles (60–63). The intestinal epithelium is bound together by tight junction proteins, which regulate the paracellular permeability and are essential for the integrity of the epithelial barrier. Tight junction proteins prevent harmful substances such as LPS, foreign antigens, toxins and microorganisms from entering into the blood stream (64).

Figure 2.

HCA2 regulates gut immune homeostasis. Butyrate produced by gut microbiota fermentation activates HCA2 expressed on IECs, macrophages, and dendritic cells. In IECs, HCA2 stimulation is associated with increased inflammasome activation, which processes pro-IL-18 into mature IL-18, which is critical in regulating mucosal immunity and epithelial integrity. IL-18 and ligand induced anti-inflammatory IL-10 (from intestinal macrophages and dendritic cells) promote naïve T cells differentiation and proliferation into immunomodulator Treg cells, which protect intestine from inflammation and colitis associated cancer. IL-18 and IL-10 also decrease the proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 cell number. In addition, HCA2 decreases proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 and TNF-α expression in intestinal macrophages and inhibits dendritic cell-induced IL-23 production to suppress ILC3-associated colonic inflammation.

IECs are well-equipped to recognize luminal pathogens by expressing different pattern recognition receptors, including NOD-like receptors (NLRs) in the cytosol and Toll-like receptors (TLRs) on the apical membrane and in endosomes, with the capacity to sample gram-positive and gram-negative infectious bacteria (65, 66). Additionally, various immune cells, including intraepithelial γδ-T cells and specialized mucosal macrophages, reside intercalated in the IEC layer, and function to sample pathogens from the lumen (67). IECs also express multimeric protein complexes known as inflammasomes that are important for intestinal immune homeostasis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Ligand stimulation of HCA2 expression is associated with increased NLRP3 inflammasome activation, which processes the proIL-18 into IL-18, an anti-inflammatory cytokine which is critical in regulating mucosal immunity and epithelial integrity (46) (Figure 2). Recent studies demonstrate that mice deficient in IL-18 have increased pathogenesis of colitis and colon cancer, and dysregulation of IL-1β expression exacerbates IBD (48, 68).

Immune cells are found in intestinal epithelium (intraepithelial lymphocytes) as well as in organized lymphoid tissues/organs, such as the Peyer's Patches (PPs) and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs). Substantial amounts of scattered innate and adaptive effector immune cells are also widely distributed in the lamina propria, which is a loosely packed connective tissue layer underlying the IEC layer (69–71) (Figure 2). Collectively, the lamina propria and IECs form a unique immunological compartment which contains the largest population of immune cells in the body, as well as supply the nerve, blood and lymph drainage for the entire mucosa (71). The lamina propria contains lymphocytes and numerous innate immune system-related cell populations, including eosinophils, macrophages, DCs, immunoglobulin (Ig) A secreting plasma cells, mast cells and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) (71–73) (Figure 2). ILCs are a family of three innate effector cells (ILC1, ILC2, and ILC3) that are critical modulators of mucosal immunity (74). Particularly, ILC3 is implicated in innate intestinal inflammation though production of IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22 under induction by IL-1β and IL-23 (75). Depletion of ILC3 abrogates innate colitis, suggesting ILC3 is responsible for the intestinal pathogenesis (75). Bhatt et al. showed that HCA2 signaling limits IL-23 production by DCs, which further suppresses ILC3-mediated colonic inflammation (76) (Figure 2). Activation of HCA2 expressed on immune cells in colon lamina propria also modulates the frequency and number of Treg cells and IL-10 producing T cells (34) (Figure 2).

The gut microbiota is considered a commensal metabolic organ with critical roles in energy salvaging and nutrient absorption. It also functions in systemic immunity regulation and protection of the colonized host by eliminating pathogenic bacteria (77). Tan et al. compared fecal microbiota composition between WT and HCA2−/− mice fed a high-fiber diet, and determined that loss of HCA2 alters microbiota composition dramatically (57). Specifically, HCA2−/− mice show an increase of Verrucomicrobiae, Alphaproteobacteria, and Bacilli, and a decrease of Bacteroidia (57). Germ-free animals show extensive impaired maturation of isolated lymphoid follicles, PPs and MLNs, and are also defective in antibody production and cytokine secretion compared to conventional animals (78). The status of germ-free animals converts after colonization with normal gut microbiota, suggesting a dynamic relationship between the commensal organism and host immune system. Gut microbiota also plays an irreplaceable role in the regulation of host intestinal gene expression with around 700 genes altered remarkably in mice under germ-free conditions. Among them, the expression of Hca2 is reduced significantly in the ileum and colon under germ-free conditions, which is restored to normal levels after introduction of gut bacteria (35).

When the balance of gut microbiota ecosystems is disturbed (dysbiosis), tight junction barrier is compromised. Antigens, toxins and microorganisms can pass through the epithelium and trigger the immune response. Intestinal dysbiosis is commonly associated with a series of intestinal and extra-intestinal pathological disorders, including obesity, diabetes mellitus, multisystem organ failure, allergy, asthma, colitis-associated cancer and IBD (77, 79). Specifically, IBD patients shift their gut microbiota composition to an enrichment of Desulfovibrio, Enterobacteriaceae, Ruminococcus gnavus, and depletion of Akkermansia Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and Lachnospiraceae (80).

Multiple evidence suggests that the composition of the intestinal microbiota can be altered by diet within hours to days, leading to aberrant immune responses (81–83). Extensive studies have demonstrated that the structure and function of the gut microbiota rapidly shifts and intestinal atrophy and low-grade inflammation occur under Western diets conditions within 1 day (84–89). Nevertheless, this influence is largely eliminated by manipulating the dietary fiber content in Western diets, allowing for protection against microbiota depletion, amelioration of the inflammation and restoration of colon length (84, 88). These beneficial aspects of fiber are largely attributed to bacterial fermentation products (SCFAs), including acetate, propionate and butyrate. SCFAs are sensed by specific immunomodulating receptors, including HCA2, GPR41, and GPR43, which are involved in intestinal immunoactivity, intestinal motility regulation and cytokine secretion (90).

Among the SCFAs, butyrate/HCA2-mediated signaling has received the most attention for its effects on intestinal homeostasis and may provide an important molecular link between gut bacteria and the host (91–94). Numerous studies have confirmed that antibiotic treatment causes gut microbiota dysbiosis by perturbing intestinal immune regulation, evidenced by a reduction in Treg cell numbers within the colon (95, 96). Niacin and HCA2 agonist supplementation efficiently rescues Treg cell depletion in antibiotic-treated WT mice, but this effect is nullified in HCA2−/− mice (34). HCA2−/− mice also show an inflammatory intestinal phenotype and enhanced susceptibility to azoxymethane (AOM) + dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis-associated colon cancer (34). Clinically, patients with ulcerative colitis and colitis-associated cancer suffer a remarkable depletion in the total amount of butyrate-producing bacteria in colon (97, 98), while irrigating the colon with butyrate significantly suppresses intestinal inflammation during ulcerative colitis (99). Hence, HCA2 is a critical link in the network of diet, microbiota, immune cells, and host cells which are necessary for the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis.

Role of HCA2 in Intestinal Inflammation

The role of HCA2 in regulating intestinal immunological response and inflammation is multifaceted. Singh et al. found that the colons of mice lacking HCA2 present a unique status of CD4+ T cells, also known as T helper cells (Th cells) (34). These cells play an important role in immune regulation, where they mediate the activation of other immune cells though the release of various cytokines. Among the CD4+ T cells, Tregs express the transcription factor Forkhead box protein P3 (Foxp3), which is capable of potently suppressing immune responses. In colonic lamina propria of HCA2−/− mice, the amount of Foxp3+/Treg cells among CD4+ T cells and anti-inflammatory IL-10 producing CD4+ T cells is significantly less than WT mice, while the frequency and number of CD4+ T cells producing the inflammatory cytokine IL-17 are increased (34). In contrast, a similar fraction of those cells distribute in splenic T cells from both WT and HCA2−/− mice, suggesting that only the colon CD4+ T cells are specifically influenced by a lack of HCA2−/− (34). Singh et al. reasoned that this proinflammatory phenotype of the HCA2−/− mice colon is dependent on colonic DCs and macrophages, since they both express HCA2 and are critical inducers of naive T cell differentiation (100, 101). They addressed this by testing the ability of colonic DCs and macrophages from both WT and HCA2−/− mice to induce differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells. As expected, HCA2−/− colonic DCs and macrophages are defective in expression of retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (RALDH1) and immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10, and express more proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 compared to WT DCs and macrophages. This change in expression leads naive CD4+ T cells to differentiate into proinflammatory Th17 cells, but not Treg cells and IL-10-producing CD4+ T cells (34). Likewise, HCA2−/− is necessary to maintain normal anti-inflammatory IL-18 levels, as both mRNA and protein expression of IL-18 are significantly decreased in IECs of HCA2−/− mice (34). Consistent with this evidence, Singh et al. also demonstrated that niacin treatment restored colonic Treg cell numbers in antibiotic-treated WT mice, and butyrate and niacin induced IL-10 and RALDH1 expression and promoted naïve T cells differentiation into Treg cells in macrophages and DCs in an HCA2-dependent manner (34) (Figure 2). In addition, butyrate and niacin increased expression of IL-18 in colonic epithelium of WT mice but not HCA2−/− mice (34).

Bhatt et al. recently described another anti-inflammatory effect of HCA2 in restraining microbiota-induced IL-23 production to suppress ILC3-associated colonic inflammation (76). To diminish the influence of the adaptive immune system, they bred HCA2−/− mice with recombination activating gene 1 (RAG1) deficient mice [no mature B and T lymphocytes (102)] to generate HCA2−/− Rag1−/− mice. HCA2−/− Rag1−/− mice spontaneously develop rectal prolapse and exhibit immune cell infiltration of the intestinal lamina propria, which is not seen in Rag1−/− mice under the same conditions (76). In addition, colons of HCA2−/− Rag1−/− mice are larger and hypercellular, over proliferative with hyperchromatic and pseudostratified nuclei and have significantly elevated number of neutrophils compared to Rag1−/− mice (76). As a result, HCA2−/− Rag1−/− mice have significantly higher colitis scores for colons and cecum compared to Rag1−/− mice (76). Importantly, HCA2−/− Rag1−/− mice have significantly increased numbers of ILC3 in the colonic lamina propria, mesenteric lymph nodes and small intestine, leading to a markedly higher frequency of IL-17 in the colonic lamina propria and mesenteric lymph nodes (76). Niacin significantly decreases IL-23 production by colonic DCs and the numbers of ILC3 in Rag1−/− mice, but fails to do so in HCA2−/− Rag1−/− mice (76). Furthermore, HCA2−/− Rag1−/− mice present signs of ongoing adenomatous transformation in the cecum and colonize a higher portion of IBD associated bacteria including Bacteroidaceae, Porphyromonadaceae, Prevotellaceae, Streptococcaceae, Christensenellaceae, Mogibacteriaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Mycoplasmataceae. Depletion of gut microbiota by antibiotics alleviates colonic inflammation by decreasing production of IL-23 and induction of ILC3 in HCA2−/− Rag1−/− mice (76).

Further detailed studies on the role of HCA2 in DSS-induced colitis treatment demonstrate that HCA2−/− mice are highly susceptible to colitis development, with all experimental animals succumbing to death 10 days after DSS administration (3). In contrast, WT counterparts all survive through the entirety of the DSS treatment (34). Sodium butyrate markedly reduces inflammation and improves IECs barrier integrity by activating HCA2 signaling and suppressing the AKT-NF-κB p65 signaling pathway in 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis, a model that resembles Crohn's disease (51, 52). In a similar study, a sodium butyrate-containing diet attenuates diarrhea symptoms and facilitates tight junction protein expression in the colon of piglets by acting on Akt signaling pathway in an HCA2-dependent manner (103). Another source of butyrate, tributyrin, is a chemically stable structured lipid that could be administered orally (104). Tributyrin supplementation prevents mice from chronic and acute ethanol-induced gut injury by improving gut barrier function (occludin, ZO-1) and increasing the expression of HCA2 in both ileum and proximal colon (105). In accordance with this, niacin administration attenuates iodoacetamide-induced colitis by a reduction in colon weight and colonic myeloperoxidase activity (a hallmark of colonic inflammation), and restores normal levels of colonic IL-10, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), angiostatin and endostatin in a rat model (106). This beneficial effect of niacin is largely abolished by mepenzolate bromide, a HCA2 receptor blocker, indicating niacin/ HCA2 signaling ameliorates iodoacetamide-induced colitis (106). In addition to it oral pharmacologic activity, niacin is also a microbial-derived metabolite, produced by specific gut microbiota, including Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bacteroides fragilis, Prevotella copri, Fusobacterium varium, Clostridium difficile, Bifidobacterium infantis, and Ruminococcus lactaris (76, 107, 108). Niacin deficiency is associated with intestinal inflammation and diarrhea (76).

Overall, these reports provide compelling evidence that HCA2 signaling modulates immune cells to inhibit production of several inflammatory cytokines, pathways, and enzymes, leading to the suppression of experimental models of colitis.

Role of HCA2 in Colon Cancer

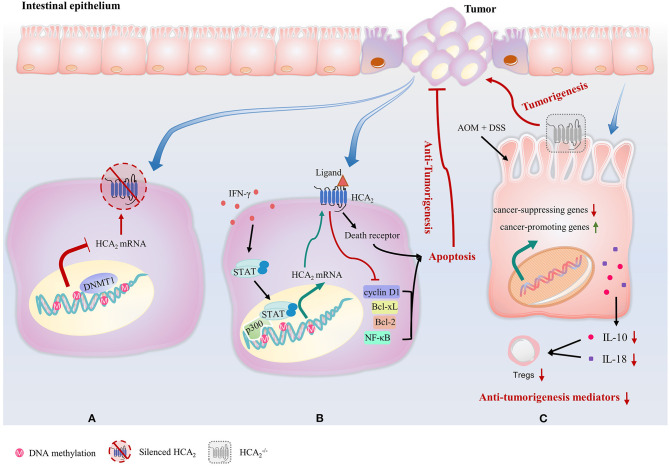

HCA2 not only plays a critical role in the suppression of intestinal inflammation, but also has a significant effect on colonic cancer development and progression. Expression of HCA2 is silenced in colon cancer cell lines, and in both mice and humans with colon cancer (24). The tumor-associated silencing of HCA2 involves DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1)-mediated DNA methylation (24) (Figure 3A). Reexpression of HCA2 in cancer cell lines induces apoptosis by inhibiting B-cell lymphoma (Bcl)-2, B-cell lymphoma-extra-large (Bcl-xL), cyclin D1 and NF-κB activity and upregulating the death receptor pathway in a ligand-dependent manner (Figure 3B). Butyrate is also an inhibitor of histone deacetylases, but this HCA2-mediated effort in colon cancer cells does not involve repressing histone deacetylation (24). Strikingly, Bardhan et al. discovered that IFN-γ reverses DNA methylation-mediated HCA2 silencing without altering the methylation status of the HCA2 promoter in colon carcinoma cells (109). Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) is rapidly activated by IFN-γ and binds to the p300 promoter to activate p300 transcription. p300 is a histone acetyltransferase and a master transcriptional mediator in mammalian cells, resulting in a permissive chromatin conformation at the HCA2 promoter to allow STAT1 to activate HCA2 transcription despite DNA methylation (109) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

HCA2 plays a critical role in the suppression of colonic cancer. (A) Expression of HCA2 is silenced in colon cancer cells. This tumor-associated silencing of HCA2 involves DNMT1-mediated DNA methylation. (B) IFN-γ reverses DNA methylation-mediated HCA2 silencing without altering the methylation status of the HCA2 promoter. STAT1 is rapidly activated by IFN-γ and binds to the p300 promoter to activate p300 transcription, resulting in a permissive chromatin conformation at the HCA2 promoter to allow HCA2 transcription in colon carcinoma cells. Reexpression of HCA2 in cancer cell lines induces apoptosis by inhibiting of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, cyclin D1, and NF-κB activity and upregulating the death receptor pathway in a ligand-dependent manner. (C) In mouse models of inflammation-associated colon cancer caused by AOM and DSS, the intestinal epithelium of HCA2−/− mice display upregulated expression of colon cancer-promoting genes and decreased genes that inhibit colitis and colon carcinogenesis. HCA2−/− mice also exhibit a severe impairment of IL-10 and IL-18 production, which leads to a decrease in Treg cell number.

Consistently, HCA2−/− mice are more susceptible to the development of colon cancer (34, 46, 106, 110). In mouse models of inflammation-associated colon cancer caused by AOM and DSS, colons of HCA2−/− mice shrink with highly increased myeloperoxidase activity, upregulated expression of colon cancer-promoting genes such as cyclin-D1, cyclin-B1, and cyclin-dependent kinase 1, decreased tight junction proteins expression and decreased expression of genes that inhibit colitis and colon carcinogenesis, such as transforming growth factor beta (Tgfb)1, Tgfb2, Solute Carrier Family 5 Member 8 (Slc5a8), MutS Homolog (Msh)2, and Msh3 (34) (Figure 3C). In addition, HCA2−/− mice exhibit a severe impairment of IL-10 and IL-18 production when compared to WT counterparts (34, 111) (Figure 3C). Histologically, crypt and epithelium structure damage, mucosa ulcerations and large amount of immune cell infiltration is observed in colons of AOM+DSS treated HCA2−/− mice group, indicating epithelial barrier breakdown (34). Systemically, levels of both colonic and serum cytokines that promote colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis such as amyloid A, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL) 1, C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL) 2, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-17 are all elevated. At the end of the AOM+DSS treatment regime, HCA2−/− mice demonstrate anemia and increased number of large polyps on colon (34). Remarkably, niacin administration suppresses colon tumor development in antibiotic-treated microbiota-depleted WT mice (34). However, it also promotes colitis-associated cancer in HCA2−/− mice, which is associated with an expansion of bacteria in Prevotellaceae family and TM7 phylum (34), suggesting microbiota/niacin protective effect is HCA2-dependent. In the same report, Singh et al. manipulated another mouse model of intestinal carcinogenesis, ApcMin/+, in which multiple intestinal neoplasia (Min) is a mutant allele of the murine adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc) locus (110). ApcMin/+ mice show significantly enlarged colonic polyp numbers, which were rescued by niacin treatment. However, niacin was not able to decrease the development of colonic polyps in HCA2−/−ApcMin/+ (34).

Taken together, these data demonstrate that HCA2 mediates cancer development and progression by promoting intestine mucosal immunity and decreasing cancer-promoting genes.

Anti-Inflammatory Effects of HCA2 in Other Diseases

HCA2 signaling plays an essential role in preventing and reducing inflammation in the intestine. In addition, HCA2 has also been associated with anti-inflammatory effects in numerous disease states. In particular, various studies report that activation of HCA2 reduces inflammation in atherosclerosis (36), diabetes mellitus (25), diabetic retinopathy (31), neurodegenerative diseases (37, 38), sepsis (39), mammary cancer (40) and pancreatitis (41). Activation of HCA2 on immune cells in the vasculature by niacin reduces the progression of atherosclerosis and suppresses macrophage recruitment to atherosclerotic plaques (36). Chronic activation of HCA2 by niacin increases serum adiponectin in obese men with metabolic syndrome, suggesting a role in diabetes mellitus and obesity (112, 113). Additionally, in pancreatic islets of diabetic db/db mice as well as in type 2 diabetic (T2D) patients, HCA2 expression is decreased (114). Administration of GSK256073, a HCA2 agonist, notably reduced serum glucose and non-esterified fatty acids without inducing the niacin-associated side effect of cutaneous flushing in diabetic patients (25). In retinal pigmented epithelial cells, niacin-mediated activation of HCA2 suppresses TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation and IL-6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) secretion (31). HCA2 ligands have been also reported to attenuate inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's disease (115), Huntington's disease (38), Alzheimer's disease (116), multiple sclerosis (37), ischemic stroke (117) and traumatic brain injury (118), although, the mechanisms behind many of these beneficial effects have yet to be fully elucidated. In sepsis, niacin attenuated kidney and lung inflammation by decreasing NF-κB activation and subsequently decreasing inflammatory cytokines (39, 119, 120). As was the case in colon cancer, HCA2 functions as a tumor suppressor in mammary cancer via inhibition of genes involved in cell survival and anti-apoptotic pathways in human breast cancer cell lines (40). In pancreatitis, β-OHB supplementation inhibits macrophage NF-κB activation in an HCA2-dependent manner, and limits sterile inflammation (41). Moreover, HCA2 plays an antiviral role in reducing the Zika virus replication. HCA2 expression is significantly induced by Zika virus infection, while depletion of HCA2 resulted in significant increase of Zika virus RNA levels and viral yields, indicating that HCA2 can serve as a restriction factor for Zika virus and providing a potential target for anti- Zika virus therapeutic (121).

Conclusion

There is mounting evidence summarized in this review that HCA2 plays an important role in modulating inflammation and carcinogenesis in the intestine. Ligands for the HCA2 receptor mediate a wide variety of inflammation-suppressing signaling events. NF-κB, NLRP3 and prostaglandins PGD2 and PGE2 have all been implicated as downstream targets of the HCA2 receptor, suggesting activation of one pathway may have beneficial or undesirable effects that are tissue-dependent. Therefore, tissue-specific, pharmacologic ligands which trigger bias signaling cascades, and therefore minimize less desirable downstream effects, are required. In addition, these pathways interweave the process of inflammatory and metabolic disorders through HCA2. Thus, this interplay of gut microbiota, HCA2 signaling and immune responses is a double-edged sword of inducing inflamed intestinal diseases or colon cancer and promoting intestinal homeostasis.

Author Contributions

ZL was primarily responsible for researching and writing the manuscript (including the generation of figures). KM was responsible for writing specific sections and reviewing the manuscript. RJ proposed the topic of the review and supervised the writing and review of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by Auburn University, Intramural Grant Program and the Boshell Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases Research Program.

References

- 1.Choct M. Managing gut health through nutrition. Br Poult Sci. (2009) 50:9–15. 10.1080/00071660802538632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abedi V, Lu P, Hontecillas R, Verma M, Vess G, Philipson CW, et al. Phase III placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial with synthetic Crohn's disease patients to evaluate treatment response. Computational Modeling-Based Discovery of Novel Classes of Anti-Inflammatory Drugs that Target Lanthionine Synthetase C-Like Protein. Emerg Trends Comput Biol Bioinform Syst Biol Syst Appl. (2015) 2:169. 10.1016/b978-0-12-804203-8.00028-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. (2011) 474:298–306. 10.1038/nature10208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaser A, Lee A-H, Franke A, Glickman JN, Zeissig S, Tilg H, et al. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. (2008) 134:743–56. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stokkers P, Hommes D. New cytokine therapeutics for inflammatory bowel disease. Cytokine. (2004) 28:167–73. 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan Q, Zhang J. Recent advances: the imbalance of cytokines in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Mediat Inflamm. (2017) 2017:4810258. 10.1155/2017/4810258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feagins LA, Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Carcinogenesis in IBD: potential targets for the prevention of colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2009) 6:297–305. 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinugasa T, Akagi Y. Status of colitis-associated cancer in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastrointest Oncol. (2016) 8:351. 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i4.351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sairenji T, Collins KL, Evans DV. An update on inflammatory bowel disease. Prim Care. (2017) 44:673–692. 10.1016/j.pop.2017.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahlhamer JM, Zammitti EP, Ward BW, Wheaton AG, Croft JB. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease among adults aged≥ 18 years—United States, 2015. Morbid Mortal Week Rep. (2016) 65:1166–9. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6542a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monteleone G, Fina D, Caruso R, Pallone F. New mediators of immunity and inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. (2006) 22:361–4. 10.1097/01.mog.0000231808.10773.8e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guan Q. A comprehensive review and update on the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol Res. (2019) 2019:7247238. 10.1155/2019/7247238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kraehenbuhl J-P, Neutra MR. Molecular and cellular basis of immune protection of mucosal surfaces. Physiol Rev. (1992) 72:853–79. 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.4.853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nomura H, Nielsen BW, Matsushima K. Molecular cloning of cDNAs encoding a LD78 receptor and putative leukocyte chemotactic peptide receptors. Int Immunol. (1993) 5:1239–49. 10.1093/intimm/5.10.1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gille A, Bodor ET, Ahmed K, Offermanns S. Nicotinic acid: pharmacological effects and mechanisms of action. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. (2008) 48:79–106. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaub A, Fütterer A, Pfeffer K. PUMA-G, an IFN-γ-inducible gene in macrophages is a novel member of the seven transmembrane spanning receptor superfamily. Eur J Immunol. (2001) 31:3714–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soga T, Kamohara M, Takasaki J, Matsumoto S-I, Saito T, Ohishi T, et al. Molecular identification of nicotinic acid receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2003) 303:364–9. 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00342-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tunaru S, Kero J, Schaub A, Wufka C, Blaukat A, Pfeffer K, et al. PUMA-G and HM74 are receptors for nicotinic acid and mediate its anti-lipolytic effect. Nat Med. (2003) 9:352. 10.1038/nm824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wise A, Foord SM, Fraser NJ, Barnes AA, Elshourbagy N, Eilert M, et al. Molecular identification of high and low affinity receptors for nicotinic acid. J Biol Chem. (2003) 278:9869–74. 10.1074/jbc.M210695200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benyó Z, Gille A, Kero J, Csiky M, Suchánková MC, Nüsing RM, et al. GPR109A (PUMA-G/HM74A) mediates nicotinic acid–induced flushing. J Clin Investig. (2005) 115:3634–40. 10.1172/JCI23626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanson J, Gille A, Zwykiel S, Lukasova M, Clausen BE, Ahmed K, et al. Nicotinic acid–and monomethyl fumarate–induced flushing involves GPR109A expressed by keratinocytes and COX-2–dependent prostanoid formation in mice. J Clin Investig. (2010) 120:2910–9. 10.1172/JCI42273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taggart AK, Kero J, Gan X, Cai T-Q, Cheng K, Ippolito M, et al. (D)-β-hydroxybutyrate inhibits adipocyte lipolysis via the nicotinic acid receptor PUMA-G. J Biol Chem. (2005) 280:26649–52. 10.1074/jbc.C500213200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Offermanns S, Colletti SL, Lovenberg TW, Semple G, Wise A, IJzerman AP. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXII: nomenclature and classification of hydroxy-carboxylic acid receptors (GPR81, GPR109A, and GPR109B). Pharmacol Rev. (2011) 63:269–90. 10.1124/pr.110.003301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thangaraju M, Cresci GA, Liu K, Ananth S, Gnanaprakasam JP, Browning DD, et al. GPR109A is a G-protein–coupled receptor for the bacterial fermentation product butyrate and functions as a tumor suppressor in colon. Cancer Res. (2009) 69:2826–32. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobbins R, Shearn S, Byerly R, Gao F, Mahar K, Napolitano A, et al. GSK256073, a selective agonist of G-protein coupled receptor 109A (GPR109A) reduces serum glucose in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab. (2013) 15:1013–21. 10.1111/dom.12132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed K, Tunaru S, Offermanns S. GPR109A, GPR109B and GPR81, a family of hydroxy-carboxylic acid receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. (2009) 30:557–62. 10.1016/j.tips.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Semple G, Skinner PJ, Gharbaoui T, Shin Y-J, Jung J-K, Cherrier MC, et al. 3-(1 H-tetrazol-5-yl)-1, 4, 5, 6-tetrahydro-cyclopentapyrazole (MK-0354): a partial agonist of the nicotinic acid receptor, G-protein coupled receptor 109a, with antilipolytic but no vasodilatory activity in mice. J Med Chem. (2008) 51:5101–8. 10.1021/jm800258p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maciejewski-Lenoir D, Richman JG, Hakak Y, Gaidarov I, Behan DP, Connolly DT. Langerhans cells release prostaglandin D2 in response to nicotinic acid. J Investig Dermatol. (2006) 126:2637–46. 10.1038/sj.jid.5700586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yousefi S, Cooper PR, Mueck B, Potter SL, Jarai G., cDNA representational difference analysis of human neutrophils stimulated by GM-CSF. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2000) 277:401–9. 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi Y, Lai X, Ye L, Chen K, Cao Z, Gong W, et al. Activated niacin receptor HCA2 inhibits chemoattractant-mediated macrophage migration via Gβγ/PKC/ERK1/2 pathway and heterologous receptor desensitization. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:42279. 10.1038/srep42279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gambhir D, Ananth S, Veeranan-Karmegam R, Elangovan S, Hester S, Jennings E, et al. GPR109A as an anti-inflammatory receptor in retinal pigment epithelial cells and its relevance to diabetic retinopathy. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2012) 53:2208–17. 10.1167/iovs.11-8447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graff E, Norris O, Sandey M, Kemppainen R, Judd R. Characterization of the hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 in cats. Domest Anim Endocrinol. (2015) 53:88–94. 10.1016/j.domaniend.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ge H, Weiszmann J, Reagan JD, Gupte J, Baribault H, Gyuris T, et al. Elucidation of signaling and functional activities of an orphan GPCR, GPR81. J Lipid Res. (2008) 49:797–803. 10.1194/jlr.M700513-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh N, Gurav A, Sivaprakasam S, Brady E, Padia R, Shi H, et al. Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity. (2014) 40:128–39. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cresci GA, Thangaraju M, Mellinger JD, Liu K, Ganapathy V. Colonic gene expression in conventional and germ-free mice with a focus on the butyrate receptor GPR109A and the butyrate transporter SLC5A8. J Gastrointest Surg. (2010) 14:449–61. 10.1007/s11605-009-1045-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lukasova M, Malaval C, Gille A, Kero J, Offermanns S. Nicotinic acid inhibits progression of atherosclerosis in mice through its receptor GPR109A expressed by immune cells. J Clin Investig. (2011) 121:1163–73. 10.1172/JCI41651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hao J, Liu R, Turner G, Shi F-D, Rho JM. Inflammation-mediated memory dysfunction and effects of a ketogenic diet in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e35476. 10.1371/journal.pone.0035476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim S, Chesser AS, Grima JC, Rappold PM, Blum D, Przedborski S, et al. D-β-hydroxybutyrate is protective in mouse models of Huntington's disease. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e24620. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwon WY, Suh GJ, Kim KS, Kwak YH. Niacin attenuates lung inflammation and improves survival during sepsis by downregulating the nuclear factor-κB pathway. Crit Care Med. (2011) 39:328–34. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181feeae4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elangovan S, Pathania R, Ramachandran S, Ananth S, Padia RN, Lan L, et al. The niacin/butyrate receptor GPR109A suppresses mammary tumorigenesis by inhibiting cell survival. Cancer Res. (2014) 74:1166–78. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoque R, Mehal WZ. Inflammasomes in pancreatic physiology and disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2015) 308:G643–51. 10.1152/ajpgi.00388.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carlson LA Orö L . The effect of nicotinic acid on the plasma free fatty acids demonstration of a metabolic type of sympathicolysis. Acta Med Scand. (1962) 172:641–5. 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1962.tb07203.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanson J, Gille A, Offermanns S. Role of HCA2 (GPR109A) in nicotinic acid and fumaric acid ester-induced effects on the skin. Pharmacol Ther. (2012) 136:1–7. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ye L, Cao Z, Lai X, Shi Y, Zhou N. Niacin ameliorates hepatic steatosis by inhibiting de novo lipogenesis via a GPR109A-mediated PKC–ERK1/2–AMPK signaling pathway in C57BL/6 mice fed a high-fat diet. J Nutr. (2020) 150:672–84. 10.1093/jn/nxz303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ye L, Cao Z, Lai X, Wang W, Guo Z, Yan L, et al. Niacin fine-tunes energy homeostasis through canonical GPR109A signaling. FASEB J. (2019) 33:4765–79. 10.1096/fj.201801951R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macia L, Tan J, Vieira AT, Leach K, Stanley D, Luong S, et al. Metabolite-sensing receptors GPR43 and GPR109A facilitate dietary fibre-induced gut homeostasis through regulation of the inflammasome. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:6734. 10.1038/ncomms7734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zaki MH, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti T-D. The Nlrp3 inflammasome: contributions to intestinal homeostasis. Trends Immunol. (2011) 32:171–9. 10.1016/j.it.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rathinam VA, Fitzgerald KA. Inflammasome complexes: emerging mechanisms and effector functions. Cell. (2016) 165:792–800. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gautam J, Banskota S, Shah S, Jee JG, Kwon E, Wang Y, et al. 4-Hydroxynonenal-induced GPR109A (HCA2 receptor) activation elicits bipolar responses, Gαi-mediated anti-inflammatory effects and Gβγ-mediated cell death. Br J Pharmacol. (2018) 175:2581–98. 10.1111/bph.14174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Offermanns S, Schwaninger M. Nutritional or pharmacological activation of HCA2 ameliorates neuroinflammation. Trends Mol Med. (2015) 21:245–55. 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zandi-Nejad K, Takakura A, Jurewicz M, Chandraker AK, Offermanns S, Mount D, et al. The role of HCA2 (GPR109A) in regulating macrophage function. FASEB J. (2013) 27:4366–74. 10.1096/fj.12-223933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fu S-P, Wang J-F, Xue W-J, Liu H-M, Liu B-R, Zeng Y-L, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of BHBA in both in vivo and in vitro Parkinson's disease models are mediated by GPR109A-dependent mechanisms. J Neuroinflamm. (2015) 12:1–14. 10.1186/s12974-014-0230-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fu S-P, Li S-N, Wang J-F, Li Y, Xie S-S, Xue W-J, et al. BHBA suppresses LPS-induced inflammation in BV-2 cells by inhibiting NF-κ B activation. Mediat Inflamm. (2014) 2014:983401. 10.1155/2014/983401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Digby JE, Martinez F, Jefferson A, Ruparelia N, Chai J, Wamil M, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of nicotinic acid in human monocytes are mediated by GPR109A dependent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2012) 32:669–76. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vitali, Mingozzi F, Broggi A, Barresi S, Zolezzi F, Bayry J, et al. Migratory, not lymphoid-resident, dendritic cells maintain peripheral self-tolerance and prevent autoimmunity via induction of iTreg cells. Blood. (2012) 120:1237–45. 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bakdash G, Vogelpoel LT, Van Capel TM, Kapsenberg ML, de Jong EC. Retinoic acid primes human dendritic cells to induce gut-homing, IL-10-producing regulatory T cells. Mucosal Immunol. (2015) 8:265–78. 10.1038/mi.2014.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tan J, McKenzie C, Vuillermin PJ, Goverse G, Vinuesa CG, Mebius RE, et al. Dietary fiber and bacterial SCFA enhance oral tolerance and protect against food allergy through diverse cellular pathways. Cell Rep. (2016) 15:2809–24. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kostylina G, Simon D, Fey M, Yousefi S, Simon H-U. Neutrophil apoptosis mediated by nicotinic acid receptors (GPR109A). Cell Death Differ. (2008) 15:134–42. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Yamada T, Mende DR, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. (2011) 473:174–80. 10.1038/nature09944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karaki S-I, Mitsui R, Hayashi H, Kato I, Sugiya H, Iwanaga T, et al. Short-chain fatty acid receptor, GPR43, is expressed by enteroendocrine cells and mucosal mast cells in rat intestine. Cell Tissue Res. (2006) 324:353–60. 10.1007/s00441-005-0140-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weiser MM. Intestinal epithelial cell surface membrane glycoprotein synthesis I. An indicator of cellular differentiation. J Biol Chem. (1973) 248:2536–41. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)44141-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peterson LW, Artis D. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. (2014) 14:141–53. 10.1038/nri3608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Umar S. Intestinal stem cells. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. (2010) 12:340–8. 10.1007/s11894-010-0130-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gonzalez-Mariscal L, Betanzos A, Nava P, Jaramillo B. Tight junction proteins. Progr Biophys Mol Biol. (2003) 81:1–44. 10.1016/S0079-6107(02)00037-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hisamatsu T, Suzuki M, Reinecker H-C, Nadeau WJ, McCormick BA, Podolsky DK. CARD15/NOD2 functions as an antibacterial factor in human intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. (2003) 124:993–1000. 10.1053/gast.2003.50153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abreu MT. Toll-like receptor signalling in the intestinal epithelium: how bacterial recognition shapes intestinal function. Nat Rev Immunol. (2010) 10:131–44. 10.1038/nri2707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen Y, Chou K, Fuchs E, Havran WL, Boismenu R. Protection of the intestinal mucosa by intraepithelial γδ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2002) 99:14338–43. 10.1073/pnas.212290499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zaki MH, Boyd KL, Vogel P, Kastan MB, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti T-D. The NLRP3 inflammasome protects against loss of epithelial integrity and mortality during experimental colitis. Immunity. (2010) 32:379–91. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Niess JH, Brand S, Gu X, Landsman L, Jung S, McCormick BA, et al. CX3CR1-mediated dendritic cell access to the intestinal lumen and bacterial clearance. Science. (2005) 307:254–8. 10.1126/science.1102901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Varol C, Vallon-Eberhard A, Elinav E, Aychek T, Shapira Y, Luche H, et al. Intestinal lamina propria dendritic cell subsets have different origin and functions. Immunity. (2009) 31:502–12. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mowat AM, Agace WW. Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. (2014) 14:667–85. 10.1038/nri3738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hooper LV, Macpherson AJ. Immune adaptations that maintain homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota. Nat Rev Immunol. (2010) 10:159–69. 10.1038/nri2710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bernink JH, Krabbendam L, Germar K, de Jong E, Gronke K, Kofoed-Nielsen M, et al. Interleukin-12 and-23 control plasticity of CD127+ group 1 and group 3 innate lymphoid cells in the intestinal lamina propria. Immunity. (2015) 43:146–60. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Artis D, Spits H. The biology of innate lymphoid cells. Nature. (2015) 517:293–301. 10.1038/nature14189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Buonocore S, Ahern PP, Uhlig HH, Ivanov II, Littman DR, Maloy KJ, et al. Innate lymphoid cells drive interleukin-23-dependent innate intestinal pathology. Nature. (2010) 464:1371–5. 10.1038/nature08949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bhatt B, Zeng P, Zhu H, Sivaprakasam S, Li S, Xiao H, et al. Gpr109a limits microbiota-induced IL-23 production to constrain ILC3-mediated colonic inflammation. J Immunol. (2018)200:2905–14. 10.4049/jimmunol.1701625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guarner F, Malagelada J-R. Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet. (2003) 361:512–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12489-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. (2009) 9:313–23. 10.1038/nri2515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Carding S, Verbeke K, Vipond DT, Corfe BM, Owen LJ. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb Ecol Health Dis. (2015) 26:26191. 10.3402/mehd.v26.26191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Berry D, Reinisch W. Intestinal microbiota: a source of novel biomarkers in inflammatory bowel diseases? Best practice & research. Clin Gastroenterol. (2013) 27:47–58. 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brown K, DeCoffe D, Molcan E, Gibson DL. Diet-induced dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota and the effects on immunity and disease. Nutrients. (2012) 4:1095–119. 10.3390/nu4081095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Howe A, Ringus DL, Williams RJ, Choo Z-N, Greenwald SM, Owens SM, et al. Divergent responses of viral and bacterial communities in the gut microbiome to dietary disturbances in mice. ISME J. (2016) 10:1217–27. 10.1038/ismej.2015.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cummings J, Jenkins D, Wiggins H. Measurement of the mean transit time of dietary residue through the human gut. Gut. (1976) 17:210–8. 10.1136/gut.17.3.210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chassaing B, Miles-Brown J, Pellizzon M, Ulman E, Ricci M, Zhang L, et al. Lack of soluble fiber drives diet-induced adiposity in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2015) 309:G528–41. 10.1152/ajpgi.00172.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alou MT, Lagier J-C, Raoult D. Diet influence on the gut microbiota and dysbiosis related to nutritional disorders. Hum Microbiome J. (2016) 1:3–11. 10.1016/j.humic.2016.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Buford TW. (Dis) Trust your gut: the gut microbiome in age-related inflammation, health, and disease. Microbiome. (2017) 5:80. 10.1186/s40168-017-0296-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Solas M, Milagro FI, Ramírez MJ, Martínez JA. Inflammation and gut-brain axis link obesity to cognitive dysfunction: plausible pharmacological interventions. Curr Opin Pharmacol. (2017) 37:87–92. 10.1016/j.coph.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zou J, Chassaing B, Singh V, Pellizzon M, Ricci M, Fythe MD, et al. Fiber-mediated nourishment of gut microbiota protects against diet-induced obesity by restoring IL-22-mediated colonic health. Cell Host Microbe. (2018) 23:41–53. e44. 10.1016/j.chom.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Martinez KB, Leone V, Chang EB. Western diets, gut dysbiosis, and metabolic diseases: are they linked? Gut Microbes. (2017) 8:130–42. 10.1080/19490976.2016.1270811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Priyadarshini M, Kotlo KU, Dudeja PK, Layden BT. Role of short chain fatty acid receptors in intestinal physiology and pathophysiology. Compr Physiol. (2018) 8:1091–115. 10.1002/cphy.c170050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mukhopadhya I, Segal JP, Carding SR, Hart AL, Hold GL. The gut virome: the ‘missing link'between gut bacteria and host immunity? Ther Adv Gastroenterol. (2019) 12:1756284819836620. 10.1177/1756284819836620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rooks MG, Garrett WS. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. (2016) 16:341–52. 10.1038/nri.2016.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Levy M, Blacher E, Elinav E. Microbiome, metabolites and host immunity. Curr Opin Microbiol. (2017) 35:8–15. 10.1016/j.mib.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kelly D, Conway S, Aminov R. Commensal gut bacteria: mechanisms of immune modulation. Trends Immunol. (2005) 26:326–33. 10.1016/j.it.2005.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, Imaoka A, Kuwahara T, Momose Y, et al. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. (2011) 331:337–41. 10.1126/science.1198469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly-Y M, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. (2013) 341:569–73. 10.1126/science.1241165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Frank DN, Amand ALS, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2007) 104:13780–85. 10.1073/pnas.0706625104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang T, Cai G, Qiu Y, Fei N, Zhang M, Pang X, et al. Structural segregation of gut microbiota between colorectal cancer patients and healthy volunteers. ISME J. (2012) 6:320–9. 10.1038/ismej.2011.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hamer HM, Jonkers D, Venema K, Vanhoutvin S, Troost F, Brummer RJ. The role of butyrate on colonic function. Alim Pharmacol Ther. (2008) 27:104–19. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03562.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Cárcamo CV, Hall J, Sun C-M, Belkaid Y, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-β-and retinoic acid–dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. (2007) 204:1757–64. 10.1084/jem.20070590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Manicassamy S, Reizis B, Ravindran R, Nakaya H, Salazar-Gonzalez RM, Wang Y-C, et al. Activation of β-catenin in dendritic cells regulates immunity vs. tolerance in the intestine. Science. (2010) 329:849–53. 10.1126/science.1188510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mombaerts P, Iacomini J, Johnson RS, Herrup K, Tonegawa S, Papaioannou VE. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. (1992) 68:869–77. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Feng W, Wu Y, Chen G, Fu S, Li B, Huang B, et al. Sodium butyrate attenuates diarrhea in weaned piglets and promotes tight junction protein expression in colon in a GPR109A-dependent manner. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2018) 47:1617–29. 10.1159/000490981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wächtershäuser A, Stein J. Rationale for the luminal provision of butyrate in intestinal diseases. Eur J Nutr. (2000) 39:164–71. 10.1007/s003940070020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cresci GA, Bush K, Nagy LE. Tributyrin supplementation protects mice from acute ethanol-induced gut injury. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. (2014) 38:1489–501. 10.1111/acer.12428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Salem HA, Wadie W. Effect of niacin on inflammation and angiogenesis in a murine model of ulcerative colitis. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:1–8. 10.1038/s41598-017-07280-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kurnasov O, Goral V, Colabroy K, Gerdes S, Anantha S, Osterman A, et al. NAD biosynthesis: identification of the tryptophan to quinolinate pathway in bacteria. Chem Biol. (2003) 10:1195–204. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gazzaniga F, Stebbins R, Chang SZ, McPeek MA, Brenner C. Microbial NAD metabolism: lessons from comparative genomics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. (2009) 73:529–41. 10.1128/MMBR.00042-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bardhan K, Paschall AV, Yang D, Chen MR, Simon PS, Bhutia YD, et al. IFNγ induces DNA methylation–silenced GPR109A expression via pSTAT1/p300 and H3K18 acetylation in colon cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. (2015) 3:795–805. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li Y, Kundu P, Seow SW, de Matos CT, Aronsson L, Chin KC, et al. Gut microbiota accelerate tumor growth via c-jun and STAT3 phosphorylation in APC Min/+ mice. Carcinogenesis. (2012) 33:1231–8. 10.1093/carcin/bgs137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Offermanns S. Hydroxy-carboxylic acid receptor actions in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. (2017) 28:227–36. 10.1016/j.tem.2016.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Plaisance EP, Lukasova M, Offermanns S, Zhang Y, Cao G, Judd RL. Niacin stimulates adiponectin secretion through the GPR109A receptor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2009) 296:E549–58. 10.1152/ajpendo.91004.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Plaisance EP, Grandjean PW, Brunson BL, Judd RL. Increased total and high–molecular weight adiponectin after extended-release niacin. Metabolism. (2008) 57:404–9. 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang N, Guo D-Y, Tian X, Lin H-P, Li Y-P, Chen S-J, et al. Niacin receptor GPR109A inhibits insulin secretion and is down-regulated in type 2 diabetic islet beta-cells. Gen Comp Endocrinol. (2016) 237:98–108. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2016.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tieu K, Perier C, Caspersen C, Teismann P, Wu D-C, Yan S-D, et al. D-β-Hydroxybutyrate rescues mitochondrial respiration and mitigates features of Parkinson disease. J Clin Investig. (2003) 112:892–901. 10.1172/JCI200318797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Van der Auwera I, Wera S, Van Leuven F, Henderson ST. A ketogenic diet reduces amyloid beta 40 and 42 in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Nutr Metab. (2005) 2:28. 10.1186/1743-7075-2-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Puchowicz MA, Zechel JL, Valerio J, Emancipator DS, Xu K, Pundik S, et al. Neuroprotection in diet-induced ketotic rat brain after focal ischemia. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab. (2008) 28:1907–16. 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hu Z-G, Wang H-D, Qiao L, Yan W, Tan Q-F, Yin H-X. The protective effect of the ketogenic diet on traumatic brain injury-induced cell death in juvenile rats. Brain Injury. (2009) 23:459–65. 10.1080/02699050902788469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gurujeyalakshmi G, Wang Y, Giri SN. Taurine and niacin block lung injury and fibrosis by down-regulating bleomycin-induced activation of transcription nuclear factor-κB in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2000) 293:82–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cho K-H, Kim H-J, Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Vaziri ND. Niacin ameliorates oxidative stress, inflammation, proteinuria, and hypertension in rats with chronic renal failure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2009) 297:F106–13. 10.1152/ajprenal.00126.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ma X, Luo X, Zhou S, Huang Y, Chen C, Huang C, et al. Hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 is a Zika virus restriction factor that can be induced by Zika virus infection through the IRE1-XBP1 pathway. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2019) 9:480. 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]