Abstract

We study open and closed string amplitudes at tree-level in string perturbation theory using the methods of single-valued integration which were developed in the prequel to this paper (Brown and Dupont in Single-valued integration and double copy, 2020). Using dihedral coordinates on the moduli spaces of curves of genus zero with marked points, we define a canonical regularisation of both open and closed string perturbation amplitudes at tree level, and deduce that they admit a Laurent expansion in Mandelstam variables whose coefficients are multiple zeta values (resp. single-valued multiple zeta values). Furthermore, we prove the existence of a motivic Laurent expansion whose image under the period map is the open string expansion, and whose image under the single-valued period map is the closed string expansion. This proves the recent conjecture of Stieberger that closed string amplitudes are the single-valued projections of (motivic lifts of) open string amplitudes. Finally, applying a variant of the single-valued formalism for cohomology with coefficients yields the KLT formula expressing closed string amplitudes as quadratic expressions in open string amplitudes.

Introduction

The beta function

As motivation for our results, it is instructive to consider the special case of the Euler beta function (Veneziano amplitude [Ven68])

| 1 |

The integral converges for , . Less familiar is the complex beta function (Virasoro–Shapiro amplitude [Vir69], [Sha70]), given by

| 2 |

The integral converges in the region , .

The beta function admits the following Laurent expansion

| 3 |

and the complex beta function has a very similar expansion

| 4 |

It is important to note that these Laurent expansions are taken at the point which lies outside the domain of convergence of the respective integrals.

The coefficients in (4) can be expressed as ‘single-valued’ zeta values which satisfy:

for The Laurent expansion (4) can thus be viewed as a ‘single-valued’ version of (3). To make this precise, we define a motivic beta function which is a formal Laurent expansion in motivic zeta values:

| 5 |

whose coefficients are motivic periods of the cohomology of the moduli spaces of curves relative to certain boundary divisors. It has a de Rham version , obtained from it by applying the de Rham projection term by term. One has

where is the single-valued period map which is defined on de Rham motivic periods. We can therefore conclude that the Laurent expansions of and are deduced from a single object, namely, the motivic beta function (5).

The first objective of this paper is to generalise all of the above for general string perturbation amplitudes at tree-level.

Cohomology with coefficients

There is another sense in which (1) is a single-valued version of (2) that does not involve expanding in s, t and uses cohomology with coefficients.

For generic values of s, t (i.e., ), it is known how to interpret as a period of a canonical pairing between algebraic de Rham cohomology and locally finite Betti (singular) homology:

| 6 |

where , is the integrable connection

on the rank one algebraic vector bundle , and is the rank one local system generated by , which is a flat section of (see Example 6.13). An important feature of this situation is Poincaré duality which gives rise to de Rham and Betti pairings between (6) for (s, t) and for . Compatibility between these pairings amounts to the following functional equation for the beta function:

| 7 |

where the factor in brackets on the left-hand side is the de Rham pairing of with itself and the factor in brackets on the right-hand side is the inverse of the Betti pairing of with .

As in the case of relative cohomology with constant coefficients studied in [BD20], there exists a single-valued formalism for cohomology with coefficients in this setting for which we give an integral formula (Theorem 7.8). This formula implies that is a single-valued period of (6), which amounts to the equality

| 8 |

and proves the second equality in (2).

Applying the functional equation (7) we then get the following ‘double copy formula’ expressing a single-valued period as a quadratic expression in ordinary periods:

| 9 |

This formula is an instance of the Kawai–Lewellen–Tye (KLT) relations [KLT86].

In conclusion, there are three different ways to deduce the complex beta function from the classical beta function: via (8) or the double copy formula (9), or by applying the single valued period map term by term in its Laurent expansion.

General string amplitudes at tree level

The general N-point genus zero open string amplitude is formally written as an integral which generalises (1):

where is a meromorphic form with certain logarithmic singularities (see Sect. 3.2), and are Mandelstam variables satisfying momentum conservation equations (30).

It turns out that one can write the closed string amplitudes in the form

Later we shall rewrite the domain of integration as the complex points of the compactified moduli space of curves of genus 0 with N ordered marked points. Then, the form

is logarithmic and has poles along the boundary of the domain of integration of the open string amplitude. It is in fact the image of the homology class of this domain under the map defined in [BD20].

The first task is to interpret the open and closed string amplitudes rigourously as integrals over the moduli space of curves . An immediate problem is that the poles of the integrand lie along divisors which do not cross normally. Using a cohomological interpretation of the momentum conservation equations in Sect. 3.1, we show how to resolve the singularities of the integral by rewriting it in terms of dihedral coordinates. These are certain cross-ratios in the , indexed by chords c in an N-gon, whose zero loci form a normal crossing divisor. Thus, for example, we write in Sect. 3.3:

where is the locus where all and the are linear combinations of the . This rewriting of the amplitude evinces the divergences of the integrand and the potential poles in the Mandelstam variables. A similar expression holds for the closed string amplitude, in which is replaced by and in which the domain of integration is replaced by the complex points of the Deligne–Mumford compactification .

By an inclusion-exclusion procedure close in spirit to renormalisation1 of algebraic integrals in perturbative quantum field theory [BK13], we can explicitly remove all poles using properties of dihedral coordinates and the combinatorics of chords. The renormalisation fundamentally hinges on special properties of morphisms between moduli spaces which play the role of counter-terms and are described in Sect. 4.

Theorem 1.1

There is a canonical ‘renormalisation’

indexed by sets J of non-crossing chords in an N-gon, where is explicitly defined. The integrals on the right-hand side are convergent around . They are by definition products of convergent integrals over domains of various dimensions.

This theorem provides an interpretation of the poles in the Mandelstam variables in terms of the poles of (see for example (51)). A similar statement holds for the closed string amplitude (Theorem 4.24). Having extended the range of convergence of the integrals using the previous theorem, we are then in a position to take a Laurent expansion around . The coefficients in this expansion, which are canonical, are products of convergent integrals of the form:

where the product ranges over chords c in a polygon and . We then show how to interpret these integrals as periods of moduli spaces for larger by replacing the logarithms with integrals (non-canonically). A key, and subtle point, is that they are integrals over a domain of a global regular form with logarithmic singularities. We can therefore interpret the previous integrals as motivic periods of universal moduli space motives, and hence define a motivic version of the string amplitude.

Theorem 1.2

There is a motivic string amplitude:

which is a Laurent expansion with coefficients in the ring of motivic multiple zeta values of homogeneous weight. Its period is the open string amplitude

It follows that the coefficients of are multiple zeta values.

The first statement has been used implicitly in [SS13], [SS19] by assuming the period conjecture for multiple zeta values. The fact that the Laurent coefficients are multiple zeta values is folklore. A subtlety in the previous theorem is that the motivic lift is a priori not unique, as there are many possible ways to express the logarithms as integrals. We believe that one could fix these choices if one wished. In any case, the period conjecture suggests that the motivic amplitude is independent of these choices.

By applying the general theorems on single-valued integration proved in the prequel to this paper [BD20] we deduce that the closed string amplitude is the single-valued version of the motivic amplitude.

Theorem 1.3

Let denote the de Rham projection map from effective mixed Tate motivic periods to de Rham motivic periods (which maps to ), and the single-valued period map (which maps to ). Then

It follows that the coefficients in the canonical Laurent expansion of the closed string amplitudes are single-valued multiple zeta values.

This theorem, for periods (i.e., assuming the period conjecture) was conjectured in [Sti14], [ST14] and proved independently by a very different method from our own in [SS19]. Since the first draft of this paper was written, yet another approach to computing the closed string amplitudes appeared in [VZ18]. An interesting consequence of Theorem 1.3 is that it suggests that the space generated by closed string amplitudes might be closed under the action of the de Rham motivic Galois group. It is important to note that the proof of the previous theorem, in contrast to the approach sketched in [SS19], uses no prior knowledge of multiple zeta values or polylogarithms, and merely involves an application of our general results on single-valued integrals.

String amplitudes from the point of view of cohomology with coefficients and double copy formulae

In the final parts of this paper Sect. 6, 7, we consider the open string amplitude as a period of the canonical pairing between algebraic de Rham cohomology with coefficients in a certain universal (Koba–Nielsen) algebraic vector bundle with connection, and locally finite homology with coefficients in its dual local system:

As in the case of the beta function, Poincaré duality exchanges and and leads to quadratic functional equations for open string amplitudes generalising (7).

It is important to note that this interpretation of the open string amplitude, as a function of generic Mandelstam variables, is quite different from its interpretation as a Laurent series. After defining the single-valued period map, our main theorem (Theorem 7.8) provides an interpretation of the closed string amplitudes as its single-valued periods. Theorem 7.8 is in no way logically equivalent to the previous results since it is not obvious that the two notions of ‘single-valuedness’, namely as a function of the , or term-by-term in their Laurent expansion, coincide. The paper [BD19] provides yet another connection between these two different cohomological points of view.

As a consequence of Theorem 7.8, we immediately deduce an identity relating closed and open string amplitudes which involves the period matrix, its inverse, and the de Rham pairing. By the compatibility between the de Rham and Betti pairings, it in turn implies a ‘double copy formula’ which generalizes (9). It expresses closed string amplitudes as quadratic expressions in open string amplitudes but this time using the Betti intersection pairing (Corollary 7.10). Since Mizera has recently shown [Miz17] that the inverse transpose matrix of Betti intersection numbers coincides with the matrix of KLT coefficients, our formula implies the KLT relations.

Because our results for genus zero string amplitudes are in fact instances of a more general mathematical theory [BD20], valid for all algebraic varieties, we expect that many of these results may carry through in some form to higher genera. It remains to be seen, in the light of [Wit12], if this has a chance of leading to a possible double copy formalism for higher genus string amplitudes.

Contents

In §2 we review the geometry of the moduli spaces , dihedral coordinates, and the forgetful maps which play a key role in the regularisation of singularities. In §3 we recall the definitions of tree-level string amplitudes, their interpretation as moduli space integrals, and discuss their convergence. Section 4 defines the ‘renormalisation’ of string amplitudes via the subtraction of counter-terms which uses the natural maps between moduli spaces. It uses in an essential way the fact that the zeros of dihedral coordinates are normal crossing. Lastly, in Sect. 5 we construct the motivic amplitude and prove the main theorems using [BD20]. The final sections Sect. 6, 7 treat cohomology with coefficients as discussed above. In an appendix, we prove a folklore result that the Parke–Taylor forms are a basis of cohomology with coefficients.

Dihedral Coordinates and Geometry of

Let and let S be a set with elements, which we frequently identify with . Let denote the moduli space of curves of genus zero with marked points labelled by S. It is a smooth scheme over whose points correspond to sets of distinct points , for , modulo the action of . Since this action is simply triply transitive, we can place and define the simplicial coordinates to be the remaining n points. In other words, they are defined for as the cross-ratios

| 10 |

Note that the indexing differs slightly from that in [Bro09]. These coordinates identify as the hyperplane complement minus diagonals, and are widespread in the physics literature. We also use cubical coordinates:

| 11 |

Dihedral extensions of moduli spaces

A dihedral structure for S is an identification of S with the edges of an -gon (which we call , or simply S when is fixed) modulo dihedral symmetries. When we identify S with we take to be the ‘standard’ dihedral structure that is compatible with the linear order on S. Let denote the set of chords of . The dihedral extension of is a smooth affine scheme over of dimension n defined in [Bro09]. Its affine ring is the ring over generated by ‘dihedral coordinates’ , for each chord , modulo the ideal generated by the relations

| 12 |

for all sets of chords which cross completely (defined in [Bro09, §2.2]). We frequently use the following special case: if c, are crossing chords, then

| 13 |

where x is a product of dihedral coordinates which depends on

The zero locus of is denoted . We have

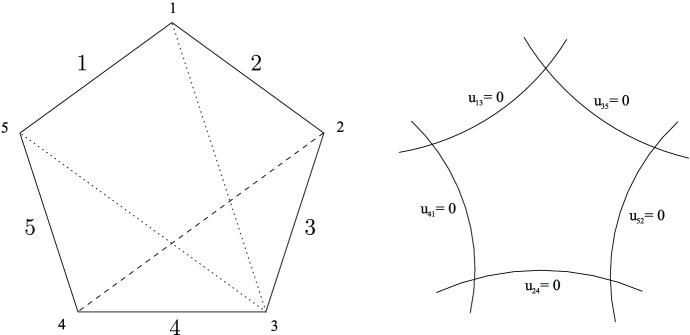

and D (also denoted by ) is a simple normal crossing divisor. Two components , intersect if and only if c, do not cross. In the case , , and the divisor D has two components, 0 and 1, corresponding to the two chords in a square. The case is pictured in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

On the left: three out of the five chords in a pentagon, corresponding to the dihedral coordinates (dashed), , (dotted). The figure illustrates the relation . On the right: the five divisors on defined by form a pentagon. Two divisors intersect if and only if the corresponding chords do not cross

Let us write for the Deligne–Mumford compactification of The open subspace can be obtained by removing all boundary divisors which are not compatible with the dihedral structure . The set of as ranges over all dihedral structures form an open affine cover of .

Morphisms

Given a subset with , let denote the dihedral structure on T induced by . There is a partially defined map induced by contracting all edges in not in T. Since some chords map to the outer edges of the polygon under this operation, it is only defined on the complementary set of such chords in . It gives rise to a ‘forgetful map’

whose associated morphism of affine rings is

| 14 |

where , and ranges over its preimages in . The forgetful map restricts to a morphism between the open moduli spaces.

A dihedral coordinate is such a morphism , where is the set of four edges which meet the endpoints of c.

Strata

Cutting along breaks the polygon S into two smaller polygons, and , with (see e.g. [Bro09, Figure 3]). There is a canonical isomorphism

| 15 |

In particular, the restriction of a dihedral coordinate to the divisor , where and c do not cross, is the dihedral coordinate on either or , depending on which component lies in.

Definition 2.1

Let be a set of k non-crossing chords. Cutting along J decomposes it into polygons , . Write

and similarly, If then set

There is a canonical isomorphism .

Trivialisation maps

A crucial ingredient in our ‘renormalisation’ of differential forms is to use dihedral coordinates to define a canonical trivialisation of the normal bundles of the divisors in a compatible manner. In order to define this, we shall fix a cyclic order on S, which is compatible with . Such a cyclic structure is simply a choice of orientation of the polygon .

Definition 2.2

Let c be a chord as above. Let be the subsets of S consisting of the edges in , respectively, together with the next edge in S with respect to the cyclic ordering . Let be the induced dihedral structures on . There are natural bijections and where in each case we identify the chord c with the next edge after or in the cyclic ordering. Consider the map

| 16 |

induced by , where is identified with . An illustration of this map is given in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

An illustration of the trivialisation map (the cyclic orientation is clockwise, induced by the numbering)

The first component is simply the dihedral coordinate , and hence the restriction of (16) to induces the isomorphism (15). Note that (15) is canonical, but depends on the choice of cyclic structure .

Lemma 2.3

If do not cross, then .

Proof

Cutting along decomposes the oriented polygon into three smaller polygons , , , where has one edge labelled by , has one edge labelled by , and two edges labelled . The graphs and each have one connected component and has exactly two components (one of which may reduce to a single vertex). Extending each such component by the next edge in the cyclic order defines sets where , , and . One checks from the definitions that

which is symmetric in . The point is that the operation of ‘extending by adding the next edge in the cyclic order’ does not depend on the order in which one cuts along the chords .

Definition 2.4

Let be a set of non-crossing chords, and define

for the composite of the maps , for , in any order, where . Its restriction to gives the canonical isomorphism .

When the cyclic ordering is fixed, we shall drop the from the notation.

Domains

Let be the subset defined by the positivity of the dihedral coordinates , for all . In simplicial coordinates (10) it is the open simplex . In cubical coordinates (11) it is the open hypercube . It serves as a domain of integration. On the domain , every dihedral coordinate takes values in (0, 1) by (13). Given a cyclic ordering on S, (16) defines a homeomorphism

More generally, for any set J of k non-crossing chords (Definition 2.1) set

| 17 |

It follows by iterating the above that

| 18 |

The closure for the analytic topology is a compact manifold with corners which has the structure of an associahedron. Note that the maps do not extend to homeomorphisms of the closed polytopes .

Logarithmic differential forms

We define to be the graded -subalgebra of regular forms on generated by the , . These are functorial with respect to forgetful maps, i.e.

| 19 |

which follows from (14). One knows that all algebraic relations between the forms are generated by quadratic relations and furthermore, by Arnol’d–Brieskorn, that is formal, i.e., the natural map

| 20 |

is an isomorphism of -algebras. Consequently, one has [Bro09, §6.1]

| 21 |

Finally, it follows from mixed Hodge theory [Del71] (see, e.g., [BD20, §4]), that

are the global sections of the sheaf of regular r-forms over , with logarithmic singularities along .

Residues

Taking the residue of logarithmic differential forms defines a map

It can be represented graphically by cutting S along the chord c (see e.g. [DV17, Proposition 4.4 and Remark 4.5] where is denoted by up to a sign). Residues are functorial with respect to forgetful maps:

Lemma 2.5

Let as in Sect. 2.2 and . Let c be a chord in in the preimage of with respect to . Suppose that cutting along breaks into polygons , and cutting along c breaks into polygons , . Then the following diagram commutes:

Proof

This is simply the functoriality of the residue. It can also be checked explicitly using (14) and (21) which implies that

where x ranges over chords in the preimage of not equal to c. Thus the statement reduces to the equation , which is clear. For a form which does not have a pole along , we have . One checks using (14) and the fact that that .

In the opposite direction, a cyclic structure defines maps

| 22 |

which send to .

Lemma 2.6

We have

| 23 |

and

| 24 |

if c and cross.

Proof

The first equality follows from the definition. Suppose that cutting along c decomposes it into . Since crosses c, (13) implies that vanishes along . Hence forms in have no poles along , which proves the second equality.

Summary of structures

With a view to generalisations we briefly list the geometric ingredients in our renormalisation procedure. We have a simple normal crossing divisor whose induced stratification defines an operad structure (15). More precisely, this is a dihedral operad in the sense of [DV17]. We have spaces of global regular logarithmic forms equipped with

- (Residues)

- (Trivialisations, depending on a choice of cyclic structure on S)

satisfying a certain number of compatibilities. In this paper, we also use the property if and do not intersect, but we plan to return to the renormalisation of integrals in a more general context with a leaner set of axioms.

Examples

Let , and set with the natural dihedral structure . The square has two chords, and two dihedral coordinates

Here, and in the next example, a subscript ij denotes the chord meeting the edges labelled and [Bro09, Figure 2]. The scheme is isomorphic, via the coordinate x, to and its dihedral extension is . The domain is the open interval (0, 1). Its closure is [0, 1].

Let , and set with the natural dihedral structure . The five chords in the pentagon give rise to five dihedral coordinates which satisfy equations given in [Bro09, §2.2]. These equations define the affine scheme . The pair are cubical coordinates (11), and embed

Its image is the complement of the hyperbola . We can write all other dihedral coordinates using (12) in terms of these two to give:

The domain maps to the open unit square . The first coordinate, x, is the forgetful map which forgets the edge :

The induced map on affine rings satisfies , .

de Rham projection

We now fix a dihedral structure on S and write S for . There is a volume form on which is canonical up to a sign [Bro09, §7.1]. A cyclic structure on S defines an orientation on the cell and fixes the sign of if we demand that its integral over be positive. In simplicial coordinates it is given by [Bro09, (7.1)]:

| 25 |

with the convention , .

Definition 2.7

Writing we define

| 26 |

Note that the sign is the same as in [BD20, §4.5]. When the dihedral structure is clear from the context, we write for

Lemma 2.8

The form defines a meromorphic form on with logarithmic singularities, and has simple poles only along those divisors which bound the cell . In simplicial coordinates (10), and using the convention , ,

| 27 |

Proof

Using the equation , where A is the set of chords which cross , which as an instance of (12), we deduce that

Using the definition of dihedral coordinates as cross-ratios [Bro09, (2.6) and §2.1],

Using the fact that is positive on one obtains

after passing to simplicial coordinates. Equation (27) then follows from (25). From (27), we see that is, up to a sign, the cellular differential form [BCS10, §2] corresponding to . The rest follows from [BCS10, Proposition 2.7].

After passing to cubical coordinates one obtains the more symmetric expression

| 28 |

The following proposition follows from the computations in [BD20, §4].

Proposition 2.9

Let denote the class of the closure of the domain . Then, with as defined in [BD20, §4], we have

Working in cubical coordinates and using (28) we get the following compatibility between the and the maps . We set

Lemma 2.10

We have

The sign is compatible with the single-valued Fubini theorem discussed in [BD20, §5]: for , , we have

Let be a set of k non-crossing chords. With the notation of Definition 2.1 we may define

We have the compatibility

| 29 |

with a sign that is compatible with the single-valued Fubini theorem.

String Amplitudes in Genus 0

We give a self-contained account of open and closed string amplitudes in genus 0, recast them in terms of dihedral coordinates, and discuss their convergence. The results in this section are standard in the physics literature, which is very extensive. The seminal references are [GSW12], [KLT86]. More recent work, including [SS13], [Sti14], [ST14], [BSST14], served as the main inspiration for the results below.

Momentum conservation

Let and let for satisfying and . Let denote homogeneous coordinates on for Consider the functions

on . The former is multi-valued, the latter is single-valued.

Lemma 3.1

The functions , define (multi-valued, in the case of ) functions on the configuration space of distinct points if and only if

| 30 |

In this case, they are automatically -invariant and define (multi-valued, in the case of ) functions on the moduli space .

Proof

The functions , are invariant under scalar transformations if and only if (30) holds. The first part of the statement follows. For the second, observe that acts by left matrix multiplication on

Since each term is minus the determinant of the matrix formed from the columns i, j, acts via scalar multiplication. We have already established that scalar invariance is equivalent to (30), and hence proves the second part. The last part follows since the moduli space is the quotient of the configuration space of N distinct points in modulo the action of .

We call (30), together with and the momentum conservation equations. The solutions to these equations form a vector space (scheme) .

When they hold, denote the above functions simply by

where . The former has a canonical branch on the locus where the points are located on the circle in the natural order, which corresponds to the domain . When (30) holds, the differential 1-form

| 31 |

defines a logarithmic 1-form on . We therefore obtain a linear map

| 32 |

for any field of characteristic zero.

Lemma 3.2

The map (32) is an isomorphism.

Proof

It is injective: if were to vanish then its residue along , viewed as a divisor in the configuration space of N distinct points on the projective line, would vanish. Hence all . Next observe that , and that is generated by , for , subject to the single relation

Therefore . By injectivity, since is a point. Hence , which equals by (21), and so (32) is an isomorphism.

String amplitudes in simplicial coordinates

It is customary in the physics literature to write the open and closed string amplitudes in simplicial coordinates (10). We use the coordinate system on consisting of the for along with the and for . We use the notation . Let and let be a global logarithmic form. Let be a solution to the momentum conservation equations (30). The associated open string amplitude is formally written as the integral

| 33 |

with the convention , . In the literature (see Theorem 6.10 below), is typically of the form

| 34 |

for some permutation of .

Closed string amplitudes are written in the form

| 35 |

where was given in Definition 2.7. For of the form (34), we can rewrite (35) as

with the notation . Note that the apparently complicated sign in the definition of is such that all signs cancel in the previous formula, in agreement with the conventions in the physics literature.

Convergence of these integrals is discussed below. As we shall see, a huge amount is gained by first rewriting them in dihedral coordinates.

String amplitudes in dihedral coordinates

Let be a set of cardinality and fix a dihedral structure. Suppose that are solutions to the momentum-conservation equations. It follows from Lemma 3.2 and (21) that we can uniquely write

where the are linear combinations of the indexed by each chord in . Thus the form a natural system of coordinates for the space . More precisely:

Lemma 3.3

Denoting a chord by a set of edges , we have

| 36 |

Proof

See [Bro09, (6.14) and (6.17)].

The coordinates are better suited than the for studying (33) and (35). By (36), we have on appropriate branches (e.g., on ) the equation:

Definition 3.4

For a tuple of complex numbers and a logarithmic form , define the open string amplitude, when it converges, to be:

| 37 |

Define the closed string amplitude, when it converges, to be:

| 38 |

These definitions are equivalent to (33) and (35), respectively, after passing to simplicial coordinates. For the closed string case, one can change its domain using the fact that differ by sets of Lebesgue measure zero.

In the physics literature, one usually wants to expand string amplitudes in the Mandelstam variables . However, the integrals (37) and (38) generally do not converge if is close to zero, as the following propositions show.

Convergence of the open and closed string amplitudes

Proposition 3.5

The integral of (37) converges absolutely for satisfying

Proof

Let be a set of non-crossing chords. The set J can be extended to a maximal set of non-crossing chords. The for form a system of local coordinates on [Bro09, §2.4]. For any , consider the set

The sets , for varying J, cover for sufficiently small . This follows because the latter is defined by the domain for all . Since and can only vanish simultaneously if c and do not cross by (13), it follows that

This implies the covering property by compactness of . It suffices to show that the integrand is absolutely convergent on each . In the local coordinates , the normal crossing property means that we can write the integrand of (37) as

where is the order of the pole of along , and has no poles on . Since is integrable on for , the condition for all guarantees absolute convergence over .

Note that the region of convergence does not permit a Taylor expansion at .

Proposition 3.6

Let . The integral of (38) converges absolutely for satisfying

| 39 |

Proof

Let denote the integrand of (38). Let be an irreducible boundary divisor. Supose first that D is a component of and is therefore defined by for some . By Lemma 2.8, has a simple pole along D. In the local coordinate , has at worst poles of the form:

In polar coordinates , the left-hand term is proportional to and hence integrable for , the right-hand term to and hence integrable for . Now consider a boundary divisor D which is a component of but which is not a component of (at ‘infinite distance’). It is defined by a local coordinate (which is a dihedral coordinate with respect to some other dihedral structure on S). By Lemma 2.8, has no pole along . Since has logarithmic singularities, is locally at worst of the form

where p is a linear form in the . Since any cross-ratio has at most a simple zero or pole along D, it follows that where (an explicit formula for p in terms of is given in [Bro09, §7.3]). By passing to polar coordinates one sees that the integrability condition reads . Assuming (39) one gets the inequality

and we are done.

Put differently, for any satisfying the assumptions (39), the integrand of (38) is polar-smooth on in the sense of Definition 3.7 of [BD20].

Example

Let , and set . We have for ,

This is the classical beta function , which converges for , . For the closed string amplitude we get

where . This is the complex beta function , which converges for , , .

‘Renormalisation’ of String Amplitudes

Formal moduli space integrands

Let us fix as above. We shall interpret the integrands of string amplitudes as formal symbols in dihedral coordinates, with a view to either taking a Taylor expansion in the variables , or specialising to complex numbers in the case when the integrals are convergent. This will furthermore enable us to treat the open and closed string integrands simultaneously. To this end, consider a fixed commutative monoid which is free with finitely many generators. The main example will be , the monoid of non-negative integer linear combinations of the symbols .

Definition 4.1

Denote by the -algebra generated by formal symbols , for and , modulo the relations and

Similarly, if c is a chord, let be the -algebra generated by for modulo the above relations. Let us write

and set

We write the elements of without the tensor product, as linear combinations of . Similarly, an element of is denoted .

Definition 4.2

Let be any subset of non-crossing chords as in Definition 2.1. Write . Let us define

Remark 4.3

There is no preferred linear order on J or on the set of polygons that are cut out by J. The tensor products in Definition 4.2 are therefore to be understood in the tensor category of graded vector spaces with the Koszul sign rule, where has degree , and has degree .

Remark 4.4

We can think of the formal function as a horizontal section of the formal connection on the trivial rank 1 bundle on the punctured (total space of the) normal bundle to .

A forgetful map defines a morphism via formula (14). By combining it with (19) we get a morphism

| 40 |

We can realise the formal moduli space integrands as differential forms as follows.

Definition 4.5

Given an additive map , define a -linear map

It is single-valued since and has a canonical branch on , which is the region . In a similar manner, we can define

Infinitesimal behaviour

We define a kind of residue of formal differential forms along boundary divisors which encodes the infinitesimal behaviour of functions in the neighbourhood of the divisor. We first define the evaluation map

as the morphism sending a formal symbol to 1 if crosses c, and all other symbols to identically named symbols.

Definition 4.6

For any we define the map

to be the tensor product of the evaluation map and the map of logarithmic differential forms .

Lemma 4.7

If do not cross, then .

Proof

The commutativity for the evaluation maps is clear. Since , the residues anticommute: . This sign is compensated by the Koszul sign rule (see Remark 4.3) for the tensor product .

Let be a subset of non-crossing chords as in Definition 2.1. By the previous lemma one can compute the iterated residue in any order, which provides a linear map

Trivialisation maps

Fix a cyclic ordering on S which is compatible with . Using the morphisms (40) define for each chord a trivialisation map

| 41 |

by (compare (22)). One checks that

| 42 |

Lemma 4.8

For , the difference lies in the ideal of generated by elements for all chords crossing c, and

Proof

Follows from the definitions.

By tensoring (41) with the map of logarithmic forms (22) one gets a map

| 43 |

Lemma 4.9

If do not cross, then .

Proof

The commutativity for the maps on the components of the tensor products involving formal symbols is clear. The claim is thus a consequence of Lemma 2.3, which treats the components which are logarithmic forms.

Let be a subset of non-crossing chords as in Definition 2.1. By the previous lemma one can compute the iterated trivialisation map in any order, which provides a map

Compatibilities

The maps and satisfy the following compatibilities.

Lemma 4.10

For every chord c we have .

For two crossing chords we have .

Proof

Lemma 4.11

Let be two chords in which do not cross. Cutting along the chord produces polygons , for with the induced cyclic or dihedral structures. Without loss of generality, suppose that lies in . Then

| 44 |

as a map from .

Proof

Use the notations of lemma 2.3. We wish to show the following diagram commutes, where the horizontal maps are induced by forgetful morphisms:

The commutativity of this diagram on the level of formal symbols is clear, and the commutativity on the level of logarithmic forms is a consequence of Lemma 2.5.

Note that (44) has to be understood via the Koszul sign rule.

We can simply write it in the unambiguous form since the source and target of a map or is uniquely determined by the data of c.

The following lemma will not be needed in our renormalisation procedure, but will play a role in the analysis of the convergence of string amplitudes.

Lemma 4.12

For and a chord , the difference is a linear combination of elements:

-

(i)

with and such that ;

-

(ii)

with and , for some chord crossing c and some .

Proof

This is a consequence of Lemma 4.8.

Integrability and residues

Proposition 4.13

Let such that for every chord c. There exists an such that:

is absolutely integrable on for any realisation such that for every generator m of M;

is absolutely integrable on for any realisation such that for every generator m of M.

Proof

It suffices to show that the integrand is absolutely convergent on each set , defined in the proof of Proposition 3.5. The normal crossing property implies that we only need to treat divergences in every local coordinate for c a chord. By Lemma 4.12 it is enough to consider integrands of the form (i) and (ii). Since is integrable around 0 if , it suffices to check in each case that is a linear combination of for and a smooth form with no poles along . The case (i) is clear. In the case (ii) we use (13) and write where has no pole along , to deduce that . Since forms in have at most logarithmic poles at , the claim follows.

- We need to prove that is integrable in the neighbourhood of every irreducible component D of . Supose first that is a component of . By Lemma 2.8, has a logarithmic pole along . By Lemma 4.12 it is enough to treat the case of integrands (i) and (ii). We work with a local coordinate . In case (i) we see that the singularities of are of the type for some . Rewriting in polar coordinates , this is proportional to , which is integrable for . In case (ii) we use (13) to write

where and have no pole along . The singularities of are thus at worst of the type or , and the claim follows as in case (i). Now consider an irreducible component D of which is not a component of (at ‘infinite distance’). It is defined by a local coordinate . By Lemma 2.8, has no pole along and the singularities of are at worst of the type for some in the abelian group generated by M, by the same argument as in the proof of Proposition 3.6. This is integrable around for . Since there are finitely many such divisors, the latter condition is implied by the hypotheses (2) for sufficiently small

Remark 4.14

In the case of closed string amplitudes, an integrand satisfying the assumptions of Proposition 4.13 (2) is polar-smooth on in the sense of Definition 3.7 of [BD20].

Renormalisation of formal moduli space integrands

Definition 4.15

Define a renormalisation map

| 45 |

where J ranges over all sets of non-crossing chords in .

The reason for calling this map the renormalisation map, even though it does not agree with the notion of renormalisation in the strict physical sense, is that it is mathematically very close to the renormalisation procedure given in [BK13].

Proposition 4.16

For all ,

Proof

By the second part of Lemma 4.10, if J contains a chord which crosses c. Let us denote by the set of subsets consisting of non-crossing chords that do not cross c. Then, in , only the summands indexed by and , for , contribute. Therefore

Each summand is of the form

By the first part of Lemma 4.10, . By the commutation relation (44), this is , and therefore the previous expression vanishes.

We extend the renormalisation map to tensor products of forms by defining it be the identity on every . For it acts upon

via , and is denoted also by .

Proposition 4.17

Any form admits a canonical decomposition (depending only on the choice of cyclic ordering of S involved in the definition of ):

| 46 |

where the sum is over non-crossing sets of chords in .

Proof

We prove formula (46) by induction on |S|. Suppose it is true for all sets S with elements, and let . Then applying the formula (46) to each component of , for , we obtain

Now, substituting into the definition of , we obtain

Via the binomial formula,

and therefore

Rearranging gives (46) and completes the induction step. The initial case with is trivial, since .

Example 4.18

Let . Let and consider

Then and . We have

and formula (46) is the statement:

If we identify s, t and their images by a realisation then the renormalised open string integrand is integrable on [0, 1] if .

On the other hand, the renormalised closed string integrand is, up to the factor :

It is integrable on for and .

Laurent expansion of open string integrals

Let

| 47 |

be the integrand of (37), viewed inside where .

Definition 4.19

Let be a set of non-crossing chords. Set

| 48 |

where denotes the iterated residue along irreducible components of and denotes the set of chords in which do not cross any element of J. Let

| 49 |

The integral of over can be canonically renormalised as follows.

Theorem 4.20

For all satisfying the assumptions of Proposition 4.13 (1),

| 50 |

where the sum in the right-hand side is over all subsets of non-crossing chords (including the empty set). The integrals on the right-hand side converge for

Proof

For any subset J of non-crossing chords, we have

where tensors are omitted for simplicity. By Proposition 4.17, we have

By (18) we have . Each summand in the last term equals

which proves (50). Absolute convergence of every integral for is guaranteed by Proposition 4.13 (1) and Proposition 4.16.

The upshot is that each integral on the right-hand side of (50) now admits a Taylor expansion around which lies in the region of convergence:

Note that this integral is a linear combination of a product of integrals over , for various , by (17).

Corollary 4.21

The open string amplitude has a canonical Laurent expansion

By proposition 3.5, it only has simple poles in the corresponding to chords c such that . More precisely,

Corollary 4.22

The residue at of is

| 51 |

Proof

It follows from the formula (50) that:

By similar arguments to those in the proof of theorem 4.20, we have

Proposition 4.17 is stated for a form but holds more generally for a tensor products of forms in , where are the polygons obtained by cutting S along c. This is because the maps and are all compatible with tensor products. Therefore writing (Sweedler’s notation) with , , we deduce that equals

We therefore deduce that

where the last equality follows from the same arguments as in the proof of theorem 4.20. We have therefore shown that both sides of (51) coincide for all values of such that the integrals converge. Note that since the left-hand side admits a Laurent expansion, the same is true of the right-hand side.

Laurent expansion of closed string amplitudes

The following lemma is the single-valued version of the formula .

Lemma 4.23

For all the following Lebesgue integral equals

Proof

Since , the integrand equals

For small enough, let be the open subset of given by the complement of three open discs of radius around (in the local coordinates ). By Stokes’ theorem,

where the boundary is a union of three negatively oriented circles around . By using Cauchy’s theorem, we see that all integrals in the right-hand side are bounded as , and that the only one which is non-vanishing in the limit as is around the point 1, giving

Let be as in (47). We set

The closed string amplitudes can be canonically renormalised as follows.

Theorem 4.24

For all satisfying the assumptions of proposition 4.13 (2):

| 52 |

where the sum in the right-hand side is over all subsets of non-crossing chords (including the empty set). The integrals on the right-hand side converge if

Proof

As in the proof of Theorem 4.20 we have

We note that

is an isomorphism outside a set of Lebesgue measure zero. Using the compatibility (29) between and the forms , and making a change of variables via , we can write each summand in the above expression as

Corollary 4.25

The closed string amplitude has a canonical Laurent expansion

By Proposition 3.6, it only has simple poles in the corresponding to chords c such that . More precisely,

Corollary 4.26

The residue at of is

| 53 |

where cutting along c decomposes S into .

The proof is similar to the proof of (51).

Motivic String Perturbation Amplitudes

Having performed a Laurent expansion of string amplitudes, we now turn to their interpretation as periods of mixed Tate motives.

Decomposition of convergent forms

Let denote the ideal generated by for any , where is a chord which crosses c. More generally, for any set of chords set and

Let denote the subspace of forms whose residue vanishes along for all We have the following refinement of Lemma 4.12.

Lemma 5.1

Let be a subset of chords, and let such that for all chords . Then has a canonical decomposition

| 54 |

where I ranges over all subsets of , and

Proof

First observe that the case where is a single chord follows from Lemma 4.12, since implies that , and therefore

Although the sum is not direct, the decomposition into two parts can be made canonical. For this, consider the natural inclusion

corresponding to the inclusions This map satisfies . Observe that is the kernel of the map . The map simply sends to 1 for all crossing c, and preserves for all other chords. Now write

The first term is annihilated by , and so lies in . The second term satisfies by definition of , and hence lies in . This gives a canonical decomposition of the form (54) when .

In the general case, proceed by induction on the size of by setting:

Since the maps commute for different c, the definition does not depend on the order in which the chords in are taken, and the decomposition is canonical. By an identical argument to the one above, we check by induction that indeed

since and

Note that the sum of the spaces is not direct.

Logarithmic expansions

For each chord c, let be a formal symbol which we think of as corresponding to a logarithm of .

There is a continuous homomorphism of algebras defined on generators by

| 55 |

This extends to a map

| 56 |

For an additive map we have the realisation maps and from Definition 4.5. A form (resp. ) has a series expansion given by composing (56) with and by interpreting the formal symbols as:

Definition 5.2

A convergent monomial is one of the form

| 57 |

where for every such that , there exists another chord which crosses c such that .

Lemma 5.3

For a convergent monomial (57), the corresponding integrals

are convergent.

Proof

For any chord which crosses , equation (13) implies that

for some . By applying this to every chord c for which , we can rewrite the above integrals as linear combinations of

where F, G have at most logarithmic singularties near boundary divisors, is a subset of chords, and has no poles along , for all . Convergence in both cases follows from a very small modification of propositions 3.5, 3.6 to allow for possible logarithmic divergences. The latter do not affect the convergence since tends to zero as for any

Proposition 5.4

Let such that for all chords c. Then admits a canonical expansion which only involves convergent monomials (57).

Proof

Corollary 5.5

Renormalised amplitudes, where they converge, can be canonically written as infinite sums of integrals of convergent monomials in logarithms:

| 58 |

where lie in the -subalgebra of generated by . Each integral on the right-hand side converges.

Equivalently, if we treat the elements of M as formal variables then the open and closed string amplitudes admit expansions in whose coefficients are canonically expressible as -linear combinations of integrals of convergent monomials as above.

Example 5.6

We apply the above recipe to Example 4.18. By abuse of notation we identify s, t with their images under a realisation , and write , . In the open case we get

| 59 |

Note that vanishes at , and at , so the integrals on the right-hand side are convergent. In the closed case we get

| 60 |

Again, the integrals on the right-hand side are convergent.

Removing a logarithm

We can now replace each logarithm with an integral one by one. It suffices to do this once and for all for .

Example 5.7

(The logarithm) Consider the forgetful map of example 2.9. It is a fibration whose fibers are isomorphic to the projective line minus 4 points. More precisely, the forgetful maps and embed as the complement of in the product . The projection onto the first factor gives a commutative diagram

The projection restricts to the real domains whose fibers are identified with (0, 1) with respect to the coordinate y. Then

The function is the dihedral coordinate on and so

| 61 |

In this manner we shall inductively replace all logarithms of dihedral coordinates with algebraic integrals. Note that it is not possible to express the logarithmic dihedral coordinate as an integral of another logarithmic dihedral coordinate over the fiber in y with respect to the same dihedral structure. It is precisely this subtlety that complicates the following arguments.

From now on, we fix a dihedral structure , and consider a differential form of degree of the following type:

| 62 |

where . Suppose that it is convergent, i.e., for every chord c such that , there exists a which crosses c with . Define

We can remove one logarithm at a time as follows.

Lemma 5.8

Pick any chord c such that , and write

Then there exists an enlargement of , i.e., and , where the restriction of to S induces , and a differential form of degree which is a sum of convergent forms (62) such that

| 63 |

Furthermore, each monomial in has weight equal to that of .

Proof

The chord c on S is determined by four edges , where and are consecutive with respect to . This identifies and with the dihedral coordinate in . Consider the set , equipped with the dihedral structure obtained by inserting a new edge next to and in between and . Let be the set of five edges with the dihedral structure inherited from . Then (see example 5.7).

Consider the diagram

It commutes since forgetful maps are functorial. Let denote the form of example 5.7 whose integral in the fiber yields and set

The product induces a morphism

and an isomorphism . Since , we find by changing variables along the map f that

The second integral takes place on the fiber product and is computed using (61). This proves equation (63).

We now check that is of the required shape (62) with respect to and convergent. First of all, observe that for any forgetful morphism and any chords a, b in S which cross, we have by (14)

where range over chords in in the preimage of a and b respectively. Every pair crosses. It remains to check the convergence condition along the poles of the 1-form For this, denote the two chords in lying above the chord c by . The chord corresponds to edges and to . By (14), we have , and by example 5.7, ( corresponds to in example 2.9). We therefore check that

where crosses c. In the sum, ranges over the preimages of under , and necessarily crosses both and . It follows that is a sum of convergent monomials in logarithms. The statement about the weights is clear.

Remark 5.9

Note that depends on the choice of where to insert the new edge we called . Similarly, the computation in example 5.7 also involves a choice: we could instead have used

Thus there are two different ways in which we can remove each logarithm. One can presumably make these choices in a canonical way.

Corollary 5.10

Let be of the form (62) and convergent. Then the integral I of over is an absolutely convergent integral

| 64 |

where is a set with dihedral structure compatible with , and a logarithmic algebraic differential form with no poles along the boundary of . Furthermore, .

Proof

Apply the previous lemma inductively to remove the logarithms one at a time. At each stage the total degree of the logarithms decreases by one. One obtains a -linear combination of convergent integrals of the form (64). Add the integrands together to obtain a single integral of the required form.

Motivic versions of open string amplitude coefficients

Let denote the tannakian category of mixed Tate motives over with rational coefficients [DG05]. An object has two underlying -vector spaces (the de Rham realisation) and (the Betti realisation) together with a comparison isomorphism . For every integer we have an object in whose de Rham and Betti realisations are the usual relative de Rham and Betti cohomology groups of the pair [GM04], [Bro09].

Let us recall [Bro14b], [Bro17] the algebra of motivic periods of the category . Its elements can be represented as equivalence classes of triples with , and . It is equipped with a period map

defined by . Let us also recall the subalgebra of effective motivic periods of .

Corollary 5.11

Let be of the form (62) and convergent. Then the integral

is a period of a universal moduli space motive where is a set with dihedral structure compatible with , and . More precisely, we can write where

is an effective motivic period of weight and is a logarithmic differential form.

Proof

Let and be as in Corollary 5.10, set and define as in the statement. We have

by definition of the comparison isomorphism for H. The statement about the weight follows from the fact that is logarithmic in the following way. As for every mixed Tate motive, the weight filtration on is canonically split by the Hodge filtration [DG05, 2.9] and we have a weight grading on H; this splitting implies in particular that . The statement about the weight says that the class of is a homogeneous element of weight with respect to this grading, i.e., that . This can be checked after extending the scalars to and thus follows from Corollary 4.13 in [BD20] (compare with [Dup18, Proposition 3.12]).

Remark 5.12

Note that the motivic lift of I depends on some choices which go into Lemma 5.8. One expects, from the period conjecture, that it is independent of these choices. One can possibly make the lift canonical by fixing choices in the application of Lemma 5.8.

We deduce a number of consequences:

Theorem 5.13

The coefficients in the Laurent expansion of open string amplitudes with N particles are multiple zeta values. More precisely,

and each . Here, is a -linear combination of multiple zeta values of weight , where

Proof

Use the fact that the periods of universal moduli space motives are multiple zeta values [Bro09]. One can obtain the statement about the weights either by modifying the argument of loc. cit or as a corollary of the next theorem (using the fact that a real motivic period of weight n of an effective mixed Tate motive over is a -linear combination of motivic multiple zeta values of weight n).

Theorem 5.13 is well-known in this field using results scattered throughout the literature, but until now lacked a completely rigorous proof from start to finish.

Theorem 5.14

The above expansion admits a (non-canonical) motivic lift

| 65 |

where is a -linear combination of motivic multiple zeta values of weight , whose period is

Proof

Apply the Laurent expansions (58) to each renormalised integrand (50) and invoke Corollary 5.11. This expresses the terms in the Laurent expansion as linear combinations of products of motivic periods of the required type.

Remark 5.15

The existence of a motivic lift is a pre-requisite for the computations of Schlotterer and Stieberger [SS13], in which the motivic periods are decomposed into an ‘f-alphabet’ (rephrased in a different language, that paper and related literature studies the action of the motivic Galois group on ). In [SS19], this is achieved by assuming the period conjecture. The computation of universal moduli space periods in terms of multiple zeta values can be carried out algorithmically [Bro09], [Pan15], [Bog16]. This type of analytic argument (or [Ter02], [BSST14]) is used in the literature to deduce a theorem of the form 5.13, but it is not capable of proving the much stronger statement 5.14.

Example 5.16

(‘Motivic’ beta function). We now treat the case of the beta function (Example 4.18) by using the expansion (59) of the renormalised part. We can remove all logarithms at once and write, for :

where is the standard simplex. We thus get the following expansion:

which can be rewritten as

| 66 |

The above argument yields a ‘motivic’ beta function

| 67 |

whose period, applied termwise, gives back (66).

Note that Ohno and Zagier observed in [OZ01] that (66) agrees with the more classical expansion of the beta function (3). Likewise, one can verify using motivic-Galois theoretic techniques that (67) indeed coincides with the definition (5).

Single valued projection and single-valued periods

We let denote the algebra of motivic de Rham periods of the category [Bro17] (see also [BD20, §2.3]). It is equipped with a single-valued period map

defined in [Bro14a], [Bro17] (see also [BD20, §2]). The de Rham projection

on effective mixed Tate motivic periods was defined in [Bro14a] and [Bro17, 4.3] (see also [BD20, Definition 4.3]).

Definition 5.17

Given a choice of motivic lift (65), define its de Rham projection to be its image after applying term-by-term:

This makes sense since is effective. Likewise, define its single-valued version

It is a Laurent series whose coefficients are -linear combinations of single-valued multiple zeta values.

Since , we could equivalently have applied the map , which is specific to the mixed Tate situation (see [BD20, §2.6]). We now compute .

Lemma 5.18

For any ,

Proof

This follows from the computations of [BD20, §6.3] after a change of coordinates.

Theorem 5.19

Consider an integral of the form

where the integrand is convergent of the form (62). Let denote a choice of motivic lift (Corollary 5.11). Its single-valued period is

| 68 |

and in particular does not depend on the choice of motivic lift.

Proof

Repeated application of Lemma 5.8 (which may involve a choice at each stage), gives rise to a dihedral structure , a morphism

and a differential form with no poles along such that

The form satisfies where

and denote the coordinates on and correspond to the , with multiplicity , taken in some order. By [BD20, Theorem 3.16] and Corollary 2.9,

| 69 |

Since are logarithmic with singularities along distinct divisors, the integral converges. By repeated application of Lemma 2.10, we obtain that is, up to a sign, the pullback by f of the form

the sign being such that after changing coordinates via f we obtain:

Theorem 5.20

We have

| 70 |

In other words, the coefficients in the canonical Laurent expansion of the closed string amplitudes (52) are the images of the single-valued projection of the coefficients in any motivic lift of the expansion coefficients of open string amplitudes.

Proof

By (50), we write the open string amplitude as

| 71 |

By Corollary 5.5, each integrand on the right-hand side admits a Taylor expansion, whose coefficients are products of integrals over moduli spaces, each of which can be lifted to motivic periods by Corollary 5.11. Thus

for some formal power series in the , whose coefficients are effective motivic periods coming from tensor products of universal moduli space motives. Since is an algebra homomorphism, (68) yields

On the other hand, by (52) these integrals can be repackaged into

By abuse of notation, we may express the previous theorem as the formula

which is equivalent to the form conjectured in [Sti14].

Remark 5.21

Define a motivic version of closed string amplitudes by setting

where was defined in [Bro17, (4.3)] (see also [BD20, Remark 2.10]). Its period is which coincides with the closed string amplitude, by the previous theorem. This object is of interest because it immediately implies a compatibility between the actions of the motivic Galois group on the open and closed string amplitudes.

Background on (Co)homology of with Coefficients

Most, if not all, of the results reviewed below are taken from the literature. A proof that the Parke–Taylor forms are a basis for cohomology with coefficients can be found in the appendix. See [KY94a], [KY94b], [CM95], [Mat98], [MY03] and references therein for more details.

Koba–Nielsen connection and local system

Let S be a finite set with . Let be a solution to the momentum conservation equations (30). Let

| 72 |

be the subfields of generated by the and respectively.

Definition 6.1

Let denote the structure sheaf on . The Koba–Nielsen connection [KN69] is the logarithmic connection on defined by

and was defined in (31). The Koba–Nielsen local system is the -local system of rank one on defined by

Since is a closed one-form, the connection is integrable. The horizontal sections of the analytification define a rank one local system over the complex numbers that is naturally isomorphic to the complexification of :

| 73 |

We will also consider the dual of the Koba–Nielsen local system

| 74 |

Let be a dihedral structure. In dihedral coordinates,

Definition 6.2

A solution to the momentum conservation equations (30) is generic if

| 75 |

for every subset with , and .

Remark 6.3

Write . By formality (20) and (21), and Lemma 3.2, the form is the specialisation of the universal abelian one-form

which represents the identity in .

Remark 6.4

The formal one-form defines a logarithmic connection on the universal enveloping algebra of the braid Lie algebra. It is the universal connection on the affine ring of the unipotent de Rham fundamental group :

The Koba–Nielsen connection (viewed as a connection over the field , i.e., for the universal solution of the momentum-conservation equations) is its abelianisation. Given any particular complex solution to the moment conservation equations, the latter specialises to a connection over .

Singular (co)homology

Denote the (singular) homology, locally finite (Borel-Moore) homology, cohomology, and cohomology with compact supports of with coefficients in by

They are finite-dimensional -vector spaces. The second is the cohomology of the complex of formal infinite sums of cochains with coefficients in whose restriction to any compact subset have only finitely many non-zero terms.

Because of (74), duality between homology and cohomology gives rises to canonical isomorphisms of -vector spaces for all k:

Proposition 6.5

If the are generic in the sense of (75), then the natural maps induce the following isomorphisms:

| 76 |

| 77 |

Proof

Let denote the open immersion. We claim that the natural map is an isomorphism in the derived category of the category of sheaves on , which amounts to the fact that has zero stalk at any point of . Since is a normal crossing divisor we are reduced, by Künneth, to proving that has non-trivial monodromy around each boundary divisor. For a divisor defined by the vanishing of a dihedral coordinate , monodromy acts by multiplication by , since is generated by . Every other boundary divisor on is obtained from such a divisor by permuting the elements of S. From formula (36) and the action of the symmetric group, it follows that the monodromy of around a divisor D defined by a partition is given by where . It is non-trivial if and only if , which is equation (75). The first statement follows by applying to the isomorphism . The second statement is dual to the first.

Remark 6.6

Under the assumptions (75), Artin vanishing and duality imply that all homology and cohomology groups in Proposition 6.5 vanish if .

The inverse to the isomorphism (77) is sometimes called regularisation. For any dihedral structure on S, the function is well-defined on the domain and defines a class in . (Strictly speaking, this class is represented by the infinite sum of the simplices of a fixed locally finite triangulation of , and does not depend on the choice of triangulation). Its image under the regularisation map, assuming (75), defines a class we abusively also denote by . The following result is classical.

Proposition 6.7

Assume that the are generic in the sense of (75). Choose three distinct elements . A basis of is provided by the classes , where ranges over the set of dihedral structures on S with respect to which a, b, c appear consecutively, and in that order (or the reverse order).

Proof

We may assume that , , and work in simplicial coordinates by fixing , , . These coordinates give an isomorphism of with the complement of the hyperplane arrangement in consisting of the hyperplanes and for , and for . This arrangement is defined over and the real points of its complement is the disjoint union of the domains for a dihedral structure on S. Such a domain is bounded in if and only if it is of the form for some permutation , i.e., if and only if no simplicial coordinate is adjacent to in the dihedral ordering. Equivalently the points are consecutive and in that order (or its reverse) in the dihedral ordering . The proposition is thus a special case of [DT97, Proposition 3.1.4].

Betti pairing

Under the assumptions (75), Poincaré–Verdier duality combined with (76) defines a perfect pairing of -vector spaces in cohomology

which is dual to a perfect pairing in homology

If and are locally finite representatives for homology classes in and respectively, then the corresponding pairing

is the number of intersection points (with signs) of and where is a regularisation of and is in general position with respect to [KY94a], [KY94b]. The matrix of the cohomological Betti pairing is the inverse transpose of the matrix of the homological Betti pairing.

Algebraic de Rham cohomology

Let denote the algebraic de Rham cohomology of with coefficients in the algebraic vector bundle with integrable connection over . It is a finite-dimensional -vector space. Let denote the analytic rank one vector bundle with connection on obtained from . We have an isomorphism

| 78 |

where the right-hand side denotes the cohomology of the complex of global smooth differential forms on with differential . Recall from [BD20, §3] the notation for the complex of sheaves of smooth forms on with logarithmic singularities along .

Proposition 6.8

Under the assumptions (75) we have a natural isomorphism

Proof

This is a smooth version of [Del70, Proposition 3.13]. The assumptions of [loc. cit.] are implied by (75) and one can check that its proof can be copied in the smooth setting.

By a classical argument due to Esnault–Schechtman–Viehweg [ESV92], we can replace global logarithmic smooth forms with global algebraic smooth forms and the cohomology group is given, under the assumptions (75), by the cohomology of the complex . In particular, is simply the quotient of by the subspace spanned by the elements for . The following theorem gives a basis of that quotient.

Theorem 6.9

Assume that the are generic in the sense of (75). A basis of is provided by the classes of the differential forms

for the tuples with and where we set .

Proof

This is a special case of [Aom87, Theorem 1].

The following more symmetric basis is more prevalent in the string theory literature. Its elements are called Parke–Taylor factors [PT86]. Therefore we shall refer to it as the Parke–Taylor basis, as opposed to the Aomoto basis of Theorem 6.9. Although the following theorem is frequently referred to in the literature, we could not find a complete proof for it and therefore provide one in “Appendix 7.4”.

Theorem 6.10

Assume that the are generic in the sense of (75). A basis of is provided by the classes of the differential forms

for permutations , where we set and .

Other bases can be found in the literature, e.g., the nbc bases of Falk–Terao [FT97].

de Rham pairing

Under the assumptions (75) there is an algebraic de Rham version of the intersection pairing, which is a perfect pairing

of -vector spaces. This is easily checked after extending the scalars to by working with smooth de Rham complexes. The only part to check is that this pairing is algebraic, i.e., defined over Indeed, it can be defined algebraically (see [CM95] for the general case of curves), and computed explicitly for hyperplane arrangements [Mat98], which contains the present situation as a special case.

If are logarithmic n-forms, let be a smooth -closed n-form on which represents and has compact support. Then

Our normalisation differs from the one in the literature by the factor of .

Periods

Since algebraic de Rham cohomology is defined over , we can meaningfully speak of periods. Using (73) we see that integration induces a perfect pairing of complex vector spaces:

which is well-defined by Stokes’ theorem. By (78) it induces an isomorphism:

| 79 |

We will use the notation when we want to make the dependence on explicit. If we choose a -basis of the left-hand vector space, and a -basis of the right-hand vector space, the isomorphism can be expressed as a matrix , and we will sometimes abusively use the notation instead of .

Theorem 6.11

(Twisted period relations [KY94a], [CM95]) Assume that the are generic in the sense of (75). Let be logarithmic n-forms giving rise to classes in and respectively. We have the equality:

| 80 |

where the cohomological Betti pairing is naturally extended by -linearity.

Proof

This follows from the fact that the (iso)morphisms (76) and (77) and Poincaré–Verdier duality are compatible with the comparison isomorphisms.

The reason for the factor in the formula (80) is because of our insistence that the de Rham intersection pairing be algebraic and have entries in

Proposition 6.12

Assume that the are generic in the sense of (75). Let be a dihedral structure on S and let be a regular logarithmic form on of top degree. If the inequalities of Proposition 3.5 hold then we have

Proof

- We first prove that the formula holds for any algebraic n-form on with logarithmic singularities along , provided for every chord . By definition we have for every the formula:

where is a global section of with compact support which is cohomologous to , i.e., such that , with a global section of . Thus, we need to prove that the integral of on vanishes if for all chords . We note that in general has singularities along the boundary of unless for all chords , so that we cannot apply Stokes’ theorem directly. We can write

where the sum is over subsets of chords and extends to a smooth form on (i.e., has no poles along the boundary of ). By properties of dihedral coordinates, we can furthermore assume that if J contains two crossing chords. Indeed, a form extends to a regular form on if every chord in J is crossed by another chord in J by (13). It is therefore sufficient to consider a single term given by a set consisting of chords that do not cross. We write and set so that we have

The forgetful maps (18) give rise to a diffeomorphism with and . We can thus write

where the are the coordinates on , corresponding to the dihedral coordinates for . Now the boundary of has components for c a chord that does not cross any chord in J. Thus, if for every chord c we have that , and hence , vanishes on the boundary of , and the inner integral is zero by Stokes’ theorem for manifolds with corners. Now, for as in the statement of the proposition, let be the divisors along which does not have a pole. Applying the first step of the proof to the product yields the result.

Example 6.13

Let . Then is one-dimensional. The locally finite homology is spanned by the class of where is the open interval (0, 1). The algebraic de Rham cohomology group is one-dimensional spanned by the class of where

The period matrix is the matrix whose entry is the beta function:

| 81 |

For any small , a representative for the regularisation of is

where denotes the small circle of radius winding positively around i. From this one easily deduces the intersection product with the class of . It is

| 82 |

See, e.g., [CM95], [KY94a, §2], or [MY03, §2]. Dually:

On the other hand, the de Rham intersection pairing [Mat98] is

| 83 |

In this case, equation (80) reads

| 84 |

using (82) and (83), as observed in [CM95], or in terms of the gamma function:

| 85 |

This can easily be deduced from the well-known functional equation for the gamma function , and is in fact equivalent to it (set ).

Self-duality

It is convenient to reformulate the above relations as a statement about self-duality. Consider the object

and denote the comparison

The results in the previous section can be summarised by saying that the triple of objects is self-dual. In other words, the Betti and de Rham pairings induce isomorphisms

which are compatible with the comparison isomorphism P. With these notations, equation (80) can be written in the simpler form:

| 86 |

Single-Valued Periods for Cohomology with Coefficients

We fix a solution of the momentum conservation equations over the complex numbers.

Complex conjugation and the single-valued period map

We can define and compute a period pairing on de Rham cohomology classes by transporting complex conjugation which is the anti-holomorphic diffeomorphism:

| 87 |

Since it reverses the orientation of simple closed loops, and since a rank one local system on is determined by a representation of the abelian group we see that we have an isomorphism of local systems:

| 88 |

We thus get a morphism of local systems on :

which at the level of cohomology induces a morphism of -vector spaces

We call the real Frobenius or Frobenius at the infinite prime. We will use the notation when we want to make dependence on explicit. One checks that the Frobenius is involutive: .

Remark 7.1

The isomorphism (88) is induced by the trivialisation of the tensor product given by the section

Thus, the action of real Frobenius on homology

is given by the formula

Remark 7.2

A morphism similar to was considered in [HY99] and leads to similar formulae but has a different definition. Our definition only uses the action of complex conjugation on the complex points of , whereas the definition in [loc. cit.] conjugates the field of coefficients of the local systems. Note that our definition does not require the to be real.

Definition 7.3

The single-valued period map is the -linear isomorphism

defined as the composite

In other words, it is defined by the following commutative diagram:

|

The single-valued period map can be computed explicitly by choosing a -bases and for and respectively and a -basis for . In these bases, the isomorphism (79) is represented by a matrix with entries

By Remark 7.1 the entries of are

The single-valued period matrix (the matrix of ) is then the product

This formula is often impractical because one needs to compute all the entries of the period matrix in order to compute any single entry of the single-valued period matrix.

Example 7.4

With the notation of Example 6.13 we have since (0, 1) is real, and the single-valued period matrix is

The single-valued period pairing via the Betti pairing

If the are generic in the sense of (75), the single-valued period map and the de Rham pairing induce a single-valued period pairing

given for by the formula

One can use the compatibility between the de Rham and the Betti pairings to express the single-valued pairing in terms of the latter.

Proposition 7.5

Assume that the are generic in the sense of (75). Let and denote by , their classes in . The corresponding single-valued period is given by the formula

and can be computed explicitly by a sum

where and range over a basis of and respectively, and are the dual bases.

Proof

We have

where the first equality is the definition of the single-valued period map, and the second equality follows from Theorem 6.11. The second formula follows from the definition of and Remark 7.1.

Example 7.6