Summary

S. mutans, a major etiological agent of human dental caries, produces membrane vesicles (MVs) that contain protein and extracellular DNA. In this study, functional genomics, along with in vitro biofilm models, was used to identify factors that regulate MV biogenesis. Our results showed that when added to growth medium, MVs significantly enhanced biofilm formation by S. mutans, especially during growth in sucrose. This effect occurred in the presence and absence of added human saliva. Functional genomics revealed several genes, including sfp, which have a major effect on S. mutans MVs. In Bacillus sp. sfp encodes a 4’-phosphopantetheinyl transferase that contributes to surfactin biosynthesis and impacts vesiculogenesis. In S. mutans, sfp resides within the TnSmu2 Genomic Island that supports pigment production associated with oxidative stress tolerance. Compared to the UA159 parent, the Δsfp mutant, TW406, demonstrated a 1.74-fold (P<0.05) higher MV yield as measured by BCA protein assay. This mutant also displayed increased susceptibility to low pH and oxidative stressors, as demonstrated by acid killing and hydrogen peroxide challenge assays. Deficiency of bacA, a putative surfactin synthetase homolog within TnSmu2, and especially dac and pdeA that encode a di-adenylyl cyclase and a phosphodiesterase, respectively, also significantly increased MV yield (P<0.05). However, elimination of bacA2, a bacitracin synthetase homolog, resulted in a >1.5-fold (P<0.05) reduction of MV yield. These results demonstrate that S. mutans MV properties are regulated by genes within and outside of the TnSmu2 island, and that as a major particulate component of the biofilm matrix, MVs significantly influence biofilm formation.

Introduction

Streptococcus mutans is a major cariogenic bacterium that lives primarily on the tooth surface in high density and high diversity communities. The bacterium possesses multiple mechanisms to colonize the tooth surface (Bowen, Burne, Wu, & Koo, 2017; Bowen & Koo, 2011; Lemos et al., 2019). It produces at least three glucosyltransferase (Gtfs) that utilize sucrose as a substrate to generate extracellular polysaccharides (also called glucans and mutans), which including the α(3,1)-linked water insoluble glucans from GtfB in particular are major constituents of the extracellular matrices of the plaque biofilms (reviewed by Bowen and Koo, 2011) (Bowen & Koo, 2011). Gtfs and their adhesive products, along with several small non-enzymatic glucan-binding proteins (Gbps), play critical roles in sucrose-mediated plaque accumulation and dental caries development (Bowen & Koo, 2011; Wen et al., 2017). The bacterium can also colonize the tooth surface in the absence of sucrose via the multi-functional adhesin SpaP (aka P1, PAc, AgI/II), which binds to the gp340 glycoprotein within the salivary pellicle (Crowley, Brady, Michalek, & Bleiweis, 1999; Lemos et al., 2019). SpaP, as well as the WapA surface protein and Smu_63c, a secreted negative regulator of competence and biofilm cell density, form amyloid fibrils within the extracellular matrix (Besingi et al., 2017). Inhibition of amyloid fibrilization is associated with reduced S. mutans biofilm formation (Besingi et al., 2017). S. mutans also actively releases extracellular deoxyribonucleic acid (eDNA), an integral component of the extracellular matrix that interacts with extracellular polysaccharides, and likely also amyloid fibrils, to enhance bacterial surface adherence and to increase biofilm formation in in vitro models (Besingi et al., 2017; Liao et al., 2014). Both in vitro and in vivo model studies have shown that S. mutans also facilitates the establishment and persistence of other bacterial species, such as Lactobacillus spp, within a cariogenic consortium supporting their ability to colonize the tooth surface and accumulate within the plaque biofilms (Wen et al., 2017; Wen, Yates, Ahn, & Burne, 2010). Physical retention of the bacteria within biofilm matrices is thought to be a major mechanism. Our recent studies have shown that adhesin SpaP and GtfB are among the key underlying factors (Wen et al., 2017).

Extracellular membrane vesicles (MV) are multi-functional bi-layered nanoparticles originally found to bleb from the outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria (Kaparakis-Liaskos & Ferrero, 2015; Schwechheimer & Kuehn, 2015). More recent studies have shown that MVs are also produced by Gram-positive bacteria, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus (Brown, Kessler, Cabezas-Sanchez, Luque-Garcia, & Casadevall, 2014; Jiang, Kong, Roland, & Curtiss, 2014; Lee et al., 2009; Rath et al., 2013; Resch et al., 2016; Rivera et al., 2010). As an important particulate component of the biofilm matrix (Brown et al., 2014; Mashburn & Whiteley, 2005; Rath et al., 2013; Schooling & Beveridge, 2006), MVs are considered as a potential source of eDNA (Whitchurch, Tolker-Nielsen, Ragas, & Mattick, 2002), and can interact with other components of the polymeric matrix to modulate intercellular signaling and biofilm formation (Liao et al., 2014; Remis et al., 2014; Schooling, Hubley, & Beveridge, 2009). While details of vesiculogenesis remain incomplete, MV biogenesis has been shown to be a highly regulated, active process (Brown et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2018; Rath et al., 2013; Resch et al., 2016; Volgers, Savelkoul, & Stassen, 2018; White, Elliott, Odean, Bemis, & Tischler, 2018). In B. subtilis and B. anthracis, surfactin was shown to play an active role in disruption of extracellular vesicles and subsequent release of vesicular cargo. Therefore, deficiency of a 4′-phosphopantetheinyl transferase (Sfp), an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of surfactin, resulted in accumulation of MVs (Brown et al., 2014). In Clostridium perfringens, MV production is triggered by the master sporulation factor Spo0 in response to environmental conditions (Obana et al., 2017). In addition, multiple orphan sensor kinases necessary for sporulation were required to maximize MV production in C. perfringens. In S. pyogenes, MV production is negatively regulated by the two-component system CovRS (Resch et al., 2016), and in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the transcriptional regulator VirR significantly influences MV release (Rath et al., 2013). In addition, the protein secretion apparatus has been shown to play a role in MV biogenesis in M. tuberculosis (White et al., 2018).

Our recent studies have shown that S. mutans also produces MVs, and that like S. pyogenes, C. perfringens and several others (Lee et al., 2009; Liao et al., 2014; Popkin, Theodore, & Cole, 1971; Rivera et al., 2010), S. mutans MVs also carry eDNA which are mostly localized outside of the MVs (Liao et al., 2014). Similar to what has been shown in M. tuberculosis (White et al., 2018), the highest levels of eDNA release in multiple species are observed during growth in iron deficient conditions, and mutant strains deficient in genes of the protein secretion apparatus also produce eDNA at higher levels than the wildtype (Liao et al., 2014). Together, these findings suggest a potential role for iron homeostasis and protein secretion systems in MV biogenesis. In addition, deficiency of SMU.833, which encodes a putative glucosyltransferase, significantly reduced glucan production and biofilm formation, and also led to higher levels of eDNA release and MV production in S. mutans (Rainey, Michalek, Wen, & Wu, 2019). In the current study, we used an in vitro biofilm model and found that when added to the culture medium, MVs significantly enhanced S. mutans biofilm formation especially when the bacterium was grown in the presence of sucrose. In addition, we used a functional genomics approach and identified several genes including sfp, bacA, bacA2, dac, and pdeA that impact MV biogenesis in this Gram-positive organism.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and cultivation.

S. mutans strains, including wild-type UA159 and its derivatives (Table 1) were maintained in brain heart infusion (BHI, Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI). When necessary, antibiotics kanamycin (Kan, 1 mg/mL), spectinomycin (Spc, 1 mg/mL), and /or erythromycin (Erm, 10 μg/mL) were added to the growth medium. For membrane vesicle preparation and stability, the bacterial strains were grown in chemically defined medium FMC with glucose as the carbohydrate source (Terleckyj, Willett, & Shockman, 1975; Wen et al., 2017). For biofilm formation, bacteria were grown in semi-defined biofilm medium (BM) with glucose (20 mM, BMG), sucrose (20 mM), and /or glucose plus sucrose (18 mM and 2 mM, respectively, BMGS) as the supplemental carbohydrate and energy sources (Loo, Corliss, & Ganeshkumar, 2000; Wen & Burne, 2002).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strains /Plasmid | Major characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|

| S. mutans UA159 | wild-type | |

| S. mutans TW406 | UA159/Δsfp, Kanr | This study |

| S. mutans TW406e | UA159/Δsfp, Ermr | This study |

| S. mutans TW406Cm | UA159/Δsfp/pDL278::Psfp, Kanr, Spcr | This study |

| S. mutans TW406Cs | UA159/Δsfp/gtfA::Psfp, Kanr, Spcr | This study |

| S. mutans TW445 | UA159/ΔbacA2, Ermr | This study |

| S. mutans TW405 | UA159/ΔbacC, Kanr | This study |

| S. mutans TW407 | UA159/ΔbacA, Kanr | This study |

| S. mutans TW426 | UA159/ΔcovR, Kanr | This study |

| S. mutans Mub | UA159/ΔTnSmu2, Kanr | (Wu et al., 2010) |

| S. mutans SMU20 | Clinic isolate, sfp+, bacA | (Palmer et al., 2013) |

| S. mutans SMU56 | Clinic isolate, sfp+, sfp+, bacA+ | (Palmer et al., 2013) |

| S. mutans SMU57 | Clinic isolate, sfp+, sfp+, nrpS+, bacA | (Palmer et al., 2013) |

| S. mutans SMU69 | Clinic isolate, sfp+, nrpS+, bacA | (Palmer et al., 2013) |

| S. mutans 27-3 | Clinic isolate, sfp+, bacA+ | This study |

| S. mutans ΔPdeA | UA159/ΔpdeA, Kanr | (Peng, Zhang, et al., 2016) |

| S. mutans ΔDac | UA159/Δdac, Ermr | (Peng, Michalek, et al., 2016) |

| S. mutans ΔDac/ΔPdeA | UA159/ΔpdeA/Δdac, Kanr, Ermr | (Peng, Michalek, et al., 2016; Peng, Zhang, et al., 2016) |

| pDL278 | Shuttle vector, Spcr | (LeBanc & Lee, 1991) |

| pBGK3 | Integration vector, Kanr | (De et al., 2017) |

| pBGS | Integration vector, Spcr | This study |

| E. coli DH10B | Cloning host, mcrA, mcrBC, mrr, and hsd | Invitrogen, Inc. |

Note: Kanr, Ermr and Spcr for kanamycin, erythromycin and spectinomycin resistance, respectively.

Human saliva collection.

Unstimulated human whole saliva was collected from fifteen healthy individuals with oral consent (IRB# 8758). The saliva was pooled and clarified by centrifugation at 3,000 x g at 4°C for 10 minutes, and then aliquoted and stored at −20°C before use as described previously (Ahn, Wen, Brady, & Burne, 2008).

Genetic manipulations.

To analyze the role of selected genes in regulation of MV biogenesis and/or stability, targeted mutants with deletion and replacement of selected genes by a non-polar kanamycin-, spectinomycin- or erythromycin resistance element were constructed by allelic exchange mutagenesis (Bitoun et al., 2013; Lau, Sung, Lee, Morrison, & Cvitkovitch, 2002; Zeng, Wen, & Burne, 2006). Briefly, the 5’ and 3’ flanking regions with the size around 1.0 kb of the target gene were PCR amplified with proper restriction sites incorporated using gene-specific primers (Table S1) and high fidelity DNA polymerase Q5 (New England Biolabs). Following Sanger sequencing to verify sequence accuracy, the PCR amplicons were digested with proper restriction enzymes and then ligated to a proper antibiotic resistance element that was digested with similar enzymes. The ligation mixture was used to directly transform S. mutans with the inclusion of competence stimulating peptide, and mutants were selected on BHI agar plates supplemented with proper antibiotics. The resulting mutants were further examined by PCR and Sanger sequencing to verify the accuracy of the target mutations. For complementation of deletion mutants, the wild-type copy of the coding sequence along with its putative promoter region was PCR amplified using Q5 DNA polymerase as described above (Table S1). Following sequence verification by Sanger sequencing, the coding sequence and cognate promoter region were cloned in integration vector pBGK3 (De et al., 2017) or pBGS that differs from pBGK3 by replacement of the kanamycin resistance marker with a non-polar spectinomycin resistance element (Huang et al., 2016). The resulting constructs were used to transform the respective deletion mutant strains, and as a result of double crossover homologous recombination at the gtfA locus, the complement strains were isolated on BHI-agar plates with proper antibiotics (Wen & Burne, 2001). In some specified cases, the coding sequence plus its cognate promoter region was cloned into and delivered to the deletion mutant via the multi-copy shuttle vector pDL278 (Table 1) (Wen, Baker, & Burne, 2006).

Membrane vesicle preparation.

Membrane vesicles (MVs) were prepared as described previously (Liao et al., 2014). Briefly, S. mutans cultures were grown in FMC medium with glucose at 20 mM overnight. Following centrifugation at 6,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, the cell-free culture supernatants were filtered first through 0.45-μm syringe filters (Pall Life Science) followed by filtration through 0.22-μm filters (Millipore) to remove residual cells. MVs in the cell-free supernatants were harvested and washed once with sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 20 mM potassium phosphate and 154 mM sodium chloride), pH 7.2 after centrifugation at 100,000 × g at 4°C for 90 min. After washing, MV pellets were resuspended in 200 μL sterile PBS, pH 7.2. MV yield was estimated by measuring the protein concentration of each sample using a micro-bicinchoninic (BCA) assay kit (Pierce). For evaluation of stability, MV preps were stained with the lipophilic dye FM 1–43 (Invitrogen) that confers red fluorescence (excitation 510 nm, emission 626 nm), and the number of the fluorescent particulates, as a reflection of MV stability, was measured using a BD Accuri C6 Plus Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences) (de Rond et al., 2018; Gorgens et al., 2019).

Biofilm analysis.

For biofilm formation, S. mutans strains were grown either on polystyrene surface in wells of 96-well plates (Corning, New York) or on hydroxylapatite discs (HA) as previously described (Wen & Burne, 2002, 2004). Briefly, for the 96-well plate model, biofilms were stained using 0.1% crystal violet, destained using a mixture of ethanol:acetone (4:1) and then quantitated using a spectrophotometer at 575 nm (Wen & Burne, 2002). In some cases, pooled human whole saliva was added to the growth medium at 10% (v/v) (Ahn et al., 2008). For microscopic analysis, biofilms were grown on HA discs that were vertically deposited in 24 well plates (Corning, New York) for 24- or 48-hours, and were further analyzed using a field emission-scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) and/or a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) as described previously (Bitoun et al., 2013; Wen et al., 2006).

Immunogold labeling and TEM analysis of MVs and eDNA nanofibers in biofilms were carried out as previously described (Besingi et al., 2017; Bitoun et al., 2013; Hung et al., 2013). Briefly, biofilms and MVs prepared similarly as described above were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.0 for 30 minutes at room temperature. For immunolabeling and negative staining, fixed samples were allowed to absorb onto freshly glow-discharged nickel grids for 10 minutes. Samples were blocked with 5% fetal bovine serum and 5% normal goat serum for 30 minutes at room temperature and subsequently incubated with primary anti-dsDNA antibody (category #AB27156, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) for 1 hour, followed by the appropriate colloidal gold-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove PA) for 1 hour. Grids were washed in PIPES buffer followed by a water rinse, and stained with 0.3% uranyl acetate/2% methyl cellulose and analyzed on a JEOL 1200EX transmission electron microscope (JEOL USA, Peabody, MA) equipped with an AMT 8 megapixel digital camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Woburn, MA).

Matrix protein release analysis.

To analyze the effects of pH and eDNA on biofilm extracellular matrix protein release, assays were carried out similarly as described by Dengler et al. (Dengler, Foulston, DeFrancesco, & Losick, 2015). S. mutans biofilms were grown on glass slides in BM-glucose and sucrose (18, 2 mM, respectively) (Wen et al., 2010), and after 48 hours of growth were scraped into PBS, pH 5.0 or 7.0, with inclusion of proteinase inhibitors (Sigma). Following proper sonication and vortexing, samples were divided into halves and spun down by centrifugation at 3,000 x g at 4°C for 10 minutes. One set was resuspended in 2 mL sterile PBS, pH 5.0, and the other in PBS, pH 7.5. The cell suspensions were mixed, and 200 μL was aliqouted into two sets of microfuge tubes, with one set treated with DNase I (100 μg/mL) for 1 hour, and the other serving as negative control receiving buffer only. Following incubation, samples were centrifuged at 21,130.00 x g, 4ºC for 10 minutes, and the supernatants were saved. The cell pellets were resuspended in 200 μL PBS, pH 7.5, incubated at 4°C for another hour, and cell pellets and supernatants collected as above. Alternatively, biofilms were grown using 12 well polystyrene culture plates (Corning, New York) with addition of DNase I (100 μg/mL) to the biofilm medium 3 hours after culture set up. Untreated and treated biofilms were processed similarly as above, and the supernatant proteins of both treated and untreated biofilms were concentrated using trichloroacetic acid precipitation. Proteins released from biofilms were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE, and the gels were stained using a silver staining kit (Pierce™ Sliver Staining kit, ThermoFisher Scientific).

Acid and oxidative tolerance assays.

The effects of deletion of target genes on the ability of S. mutans to withstand acid and oxidative stresses were assessed by using acid killing and hydrogen peroxide challenge assays as described previously. (Wen & Burne, 2004). Briefly, planktonic cultures of S. mutans strains were grown in BHI until mid-exponential phase (OD600nm = 0.3–0.4) and then subjected to acid killing at pH 2.8, or killing in glycine buffer containing 0.3% hydrogen peroxide (w/v, or 58 mM final concentration) for the specified period of time. (Wen & Burne, 2004)

Statistical analysis.

Quantitative data were analyzed using the Student t test. A P value of 0.05 or less is considered statistically significant.

Results

MV enhances S. mutans biofilm formation independently of saliva.

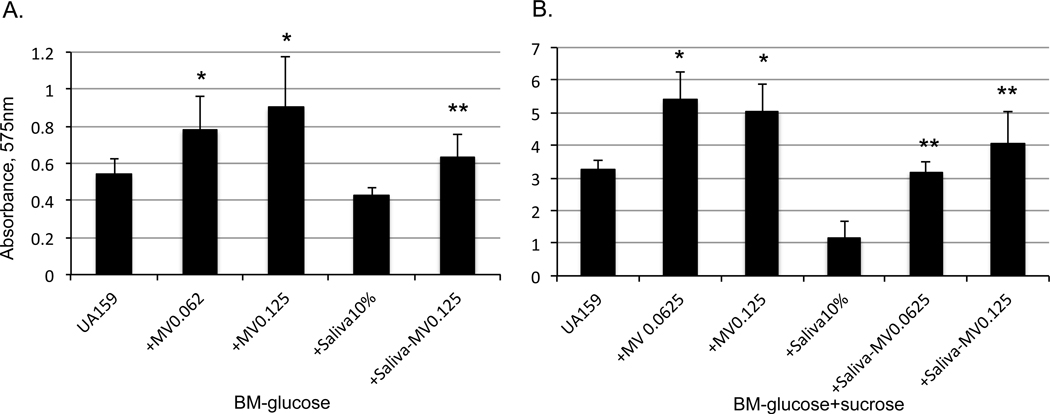

Previously, we showed that S. mutans produces MVs, but unlike Gram-negative bacteria, little information is available concerning the role of MVs in the pathophysiology of this bacterium (Liao et al., 2014). To assess how MVs affect S. mutans biofilm formation, exogenous MV preparations were added to biofilm medium containing glucose and /or sucrose in the presence or absence of pooled human whole saliva, which has been shown to influence biofilm development (Ahn et al., 2008). Inclusion of MVs in the culture medium resulted in significant increases of S. mutans biofilm formation after 24 hours as estimated using a 96-well plate assay (Fig. 1 A&B). Significantly increased biofilm formation was observed upon MV addition at both 0.0625 and 0.125 μg mL−1 protein levels, when bacteria were grown in biofilm medium (BM) with glucose (Fig. 1A), or BM with glucose and sucrose (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, controls that received similar amounts of bovine serum albumin (Sigma) showed significant reductions in biofilm formation (Fig. S1). Consistent with our previous findings (Ahn et al., 2008), inclusion of human whole saliva in the culture medium significantly reduced S. mutans biofilm formation, especially during growth in sucrose (Fig. 1B). When MVs were also included with saliva in the culture medium, biofilm formation was partially restored in cultures grown under both glucose- and sucrose-growth conditions. This demonstrates that S. mutans MVs enhance biofilm formation irrespective of whether human saliva is present or not.

Figure 1.

Effect of S. mutans MVs and saliva on biofilm formation. S. mutans UA159 was grown in 96 well plates in biofilm medium containing glucose (20 mM), or glucose plus sucrose (18, 2 mM, respectively), with and without inclusion of MVs at the indicated protein level (in mg), and in the presence or absence of pooled human whole saliva (saliva, at 10% (v/v). Data represent the average (±standard deviation) of at least three independent sets of experiments. * indicates P<0.001 vs UA159 without saliva, and ** indicates P<0.001 vs. UA159 plus saliva.

Sfp-deficiency significantly influences MV production.

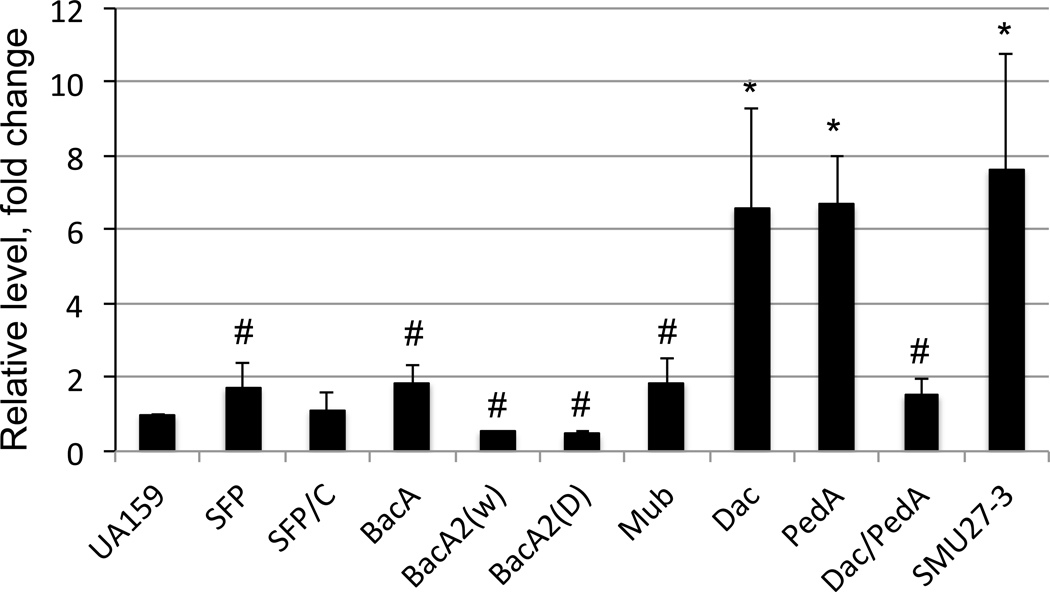

The sfp gene in B. subtilis, encodes a 4’-phosphopantetheinyl transferase, which contributes to biosynthesis of the lipopeptide antibiotic surfactin (Brown et al., 2014). In this organism, Sfp deficiency leads to a biofilm defect despite increased hyper-accumulation of MVs that results from their enhanced stability and impaired cargo release. When the amino acid sequence of Bacillus sp. Sfp was used as the query to BLAST search the genome databases (www.theseed.org), S. mutans was found to possess a gene (SMU.1217 or SMU1334) within the TnSmu2 genomic island that encodes a Sfp homolog. Interestingly, none of the other oral streptococci analyzed, including S. sanguinis and S. gordonii, appear to contain such a gene. Nor do group A or group B streptococci. To assess the role of Sfp in S. mutans MV biogenesis, a deletion mutant was constructed by replacing the sfp coding region with a non-polar kanamycin resistance marker via PCR-Ligation-Mutation strategy (Burne et al., 2011). Compared to the parent strain, UA159, the sfp-deficient mutant, TW406 displayed no significant differences in growth rate, but yielded a slightly higher cell mass overnight as indicated by optical density, when grown in regular BHI broth (Fig. S2). However, the TW406 MV yield as estimated by BCA protein assay was consistently higher than that of the parent strain (P<0.05) (Fig. 2). A similar result was also obtained with another allelic exchange mutant in which a non-polar erythromycin resistance element was used to replace the non-polar kanamycin resistance marker (data not shown). As expected, complementation with the wild-type copy of sfp and its cognate promoter via double-crossover integration into the chromosome restored the MV measurement to that of the parent strain (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of MV production by various S. mutans strains. S. mutans UA159, its targeted Δsfp deletion mutant (SFP) and complement strain (SFP/C), its targeted ΔbacA deletion mutant (BacA), two targeted ΔbacA2 deletion mutants with smooth wet (BacA2(w)) or rough dry (BacA2(d) colony morphology, its targeted Δdac (Dac), ΔpdeA (PdeA), and Δdac/ΔpdeA (Dac/PdeA) single and double mutants, its Mub gene cluster mutant (Mub), and clinic strain 27-3 were grown in FMC defined medium. MV yield was estimated by measurement of protein concentration of MV samples by BCA assay normalized against colony-forming-units and expressed as fold-change relative to the UA159 parent strain. *, # indicate significant differences vs UA159 at P<0.05 and 0.001, respectively.

When the MV particulates from the wild-type and sfp-deficient strains were stained with the lipophilic fluorescent dye FM 1–43 and measured by flow cytometry, the results showed that during incubation at 37°C, the number of fluorescent particulates of both the wild-type and the mutant was reduced by ≥70% within two hours, indicative of MV lysis under the condition tested (Fig. S3A). The number of fluorescent particulates from the sfp mutant was reduced approximately ~9% (P<0.05) more than that of the wild-type, and this difference was maintained over the subsequent time points analyzed (Fig. S3A). In contrast, the particulates were relatively stable and no significant reduction in numbers of the fluorescent particulates were observed during incubation for up to 6 hours at room temperature (Fig. S3B). Interestingly, during extended incubation at room temperature for 24, 48 and 72 hours, the sfp-deficient mutant was found to possess higher numbers of fluorescent particulates than the parent strain, suggestive of increased stability in response to Sfp deficiency (Fig. S3C).

Sfp-deficiency leads to increased susceptibility to acid and oxidative stressors.

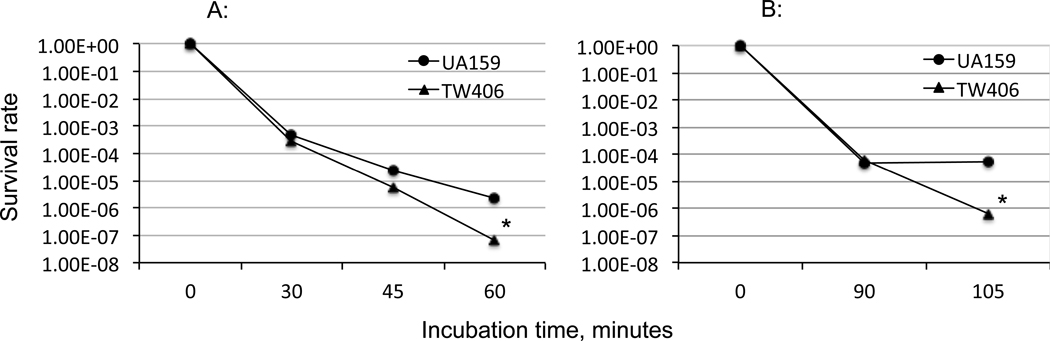

To further assess if Sfp-deficiency in S. mutans influences the deficient mutant to survive and adapt environmental stressors such as low pH and hydrogen peroxide, S. mutans UA159 and the sfp mutant were also grown in BHI, BHI adjusted to pH 6.5, and BHI containing methyl viologen, a chemical that induces oxidative stress via superoxide production. There was no significant differences in growth rates between the wild-type UA159 and its sfp-deficient strains in BHI at pH 6.5, although the sfp mutant did have an increased overnight cell mass as indicated by optical density (P<0.05). No significant difference was observed between the wild-type and the sfp mutant during growth in the presence of methyl viologen (Fig. S2). In contrast, however, when subjected to acid killing at pH 2.8 for 60 minutes, sfp mutant TW406 demonstrated >1-log reduced survival after 60 minutes compared to the UA159 parent (P<0.001) (Fig. 3A). Similarly, following incubation in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide, the sfp-deficient mutant demonstrated >2-log reduced survival after 105 minutes of incubation (P<0.001) (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that a lack of Sfp in S. mutans significantly weakens this organism’s ability to tolerate low pH and oxidative stressors. The sfp mutant was also examined for the impact of Sfp deficiency on biofilm formation. No significant difference in biofilm formation was measured between the sfp mutant and its parent strain when grown on 96-well plates (P>0.05) (Fig S4A), although slightly less biofilm was observed following growth on hydroxylapatite discs and analysis under FE-SEM (Fig. S4B), as compared to the UA159 parent. No notable differences in cell morphology of UA159 and the sfp mutant were observed under TEM (Fig. S4C).

Figure 3.

Acid killing and oxidative tolerance analysis. (A) Acid killing. S. mutans wild-type (UA159) and its Sfp mutant (TW406) were grown to mid-exponential phase in regular BHI broth, and following incubation in pH 2.8 buffer for the indicated time period, survival rates were calculated and plotted. (B) Hydrogen peroxide challenge assays. UA159 and TW406 were tested as in A with exposure to 0.3% H2O2 in glycine buffer for the indicated time period. Data represent results of three separate sets of experiments with * indicating P<0.001 compared to the parent strain.

Deficiency of BacA and BacA2 influences S. mutans MVs.

Clustered with sfp (also known as mubP) in the S. mutans TnSmu2 GI are genes responsible for biosynthesis of a hybrid nonribosomal peptide (NRP) and polyketide (PK) pigment termed mutanobactin (Mub). These are annotated as bacC (SMU.1339 or SMU1222), bacA2 (SMU.1342 or SMU1225), and bacA (SMU.1340 or SMU1223) for polypeptides with the highest homology to Brevibacillus texasporus bacitracin synthetase, Bacillus licheniformis bacitracin synthetase, and Bacillus licheniformis surfactin synthetase, respectively (Wu et al., 2010). Differences also exist in the sequences of these genes, and their organization and locations, among different S. mutans strains. Certain clinical isolates naturally lack BacA2 (isolates SMU57 and SMU69), or both BacA2 and NRP Synthetase (isolate SMU20), and some have duplicate of Sfp’s (isolates SMU56 and SMU57) (Table 1) (Palmer et al., 2013). When compared to UA159, the commonly used laboratory strain as a control, several of the clinic strains displayed a significantly higher MV yield as assessed by BCA protein assay (Fig. S5). An isogenic allelic exchange mutant of UA159, in which bacA was deliberately deleted and replaced with a non-polar kanamycin resistance marker, demonstrated an apparent 1.87-fold higher MV yield compared to its parent strain, UA159 (P<0.05) (Fig. 2). Further analysis of the bacA mutant showed that when compared to its parent strain, UA159, no major differences were observed in growth rate or overnight culture optical density when grown in regular BHI (Fig. S6). In addition, no significant difference in biofilm formation on 96-well plates was measured between the bacC mutant and the wild-type (Fig. S7).

In contrast to elimination of bacA, engineered allelic exchange mutants of bacA2 demonstrated an approximate 2-fold reduction in MV yield as estimated by protein measurement (Fig. 2). Interestingly, two individual mutant strains deficient in bacA2 displayed distinct colony morphologies, one that formed wet, mucoid round colonies with a smooth surface, and the other that formed dry colonies with rough surface similar to the parent strain (Fig. S8). Upon passage of colonies on agar plates, the wet colony phenotype remained stable, whereas smooth wet colonies could be propagated from the rough dry colony phenotype. Genome sequencing using an Illumina platform was performed on both mutant variants in an attempt to uncover the genetic basis for the two different colony phenotypes. The results of comparative genomic analysis of the two mutant variants and their parent strain UA159 confirmed deletion of bacA2 and its replacement with a non-polar erythromycin resistance gene, but no major differences in genetic composition were identified between the mutants and the wild-type parent strain. The molecular mechanisms that underlie the two distinct colony morphologies await further investigation. Further phenotypic analysis of the bacA2 mutants showed that both the dry and wet variants grew better in BHI adjusted to pH 6.5, with a faster growth rate and higher overnight cell density than the UA159 parent strain (Fig. S6 and S9). Despite this enhanced growth in broth, no significant differences in biofilm formation (Fig. S7), antibiotic resistance and hydrogen peroxide resistance were identified between the two bacA2 mutants and the wild-type UA159 (data not shown). An allelic exchange mutant of UA159 lacking bacC was also constructed, but unlike the bacA and bacA2 mutants, the bacC mutant did not show a significant difference in MV yield compared to the UA159 parent (data not shown). Similar to elimination of sfp or bacA, deletion of the entire mub cluster and its replacement with a non-polar kanamycin resistance marker (a gift from Dr. Fengxia Qi at the University of Oklahoma) (Wu et al., 2010), also resulted in a higher MV yield (P<0.05) (Fig 2), although the difference was not as pronounced as some of the clinical isolates with naturally occurring variations at this locus (Fig. S5).

Clinic strain 27-3 displays major genomic differences compared to UA159 as well as a significantly increased MV yield.

Of the clinic strains analyzed, strain 27-3 (a kind gift of Dr. Justin Merritt at OHSU, Oregon, USA) demonstrated a significantly higher MV yield compared to the UA159 laboratory strain (Fig. 2). Unlike UA159, 27-3 produces yellow pigments similar to what has been reported for strain UA140 (Wu et al., 2010). When compared to UA140 and UA159, 27-3 appeared to display a slightly slower growth rate than UA159 and UA140 (P<0.05) when grown in regular BHI and BHI with pH adjusted to 6.5, although the differences were not statistically significant (P>0.05) (Fig. S10). However, during growth in BHI with inclusion of methyl viologen, 27-3 had a significantly higher overnight cell yield as measured by optical density than either UA159 or UA140 (P<0.001) (Fig. S10). These results indicate clinic isolate 27-3 has a better capacity to survive oxidative stressors than lab strains. When examined by TEM, an increased level of vesicular structures surrounding the bacterial cells was evident compared to UA159 (Fig. 4). In addition, 27-3 also displayed numerous particle-like structures of various sizes closely associated with the cell envelope (Fig. 4), although the nature and function these structures await further investigation.

Figure 4.

TEM analysis of S. mutans UA159 and clinic strain 27-3 when grown in BHI broth until mid-exponential phase (OD600nm ≈0.4). Besides more MVs, 27-3 also displays numerous particle-like structures of various sizes closely associated with the cell envelope (arrows), whose nature and function remain unknown, when compared to the lab strain UA159. Scale bars represent 100 nm.

In an effort to uncover any potential genetic factors that underlie the apparent alteration in of MV production and stronger capacity to tolerate oxidative stressors, the genome of 27-3 was sequenced using an Illumina platform. Comparative genomic analysis revealed numerous differences between UA159 and 27-3, including 192 gene additions and 275 gene deletions (BioProject ID: PRJNA665774). When the TnSmu2 GI, which is responsible for production of yellow pigment mutanobactin in UA140, was compared between the three strains, the 27-3 GI was found to be highly homologous to that of UA140 (Table S2). Whereas UA159 possesses four genes for NRP synthetases and two for PK synthetases, 27-3 has two NRP synthetase genes and four PK synthetase genes, similar to UA140. Also similar to UA140, but different from UA159, 27-3 possesses sfp but does not have bacA. Thus, natural deficiency of bacA likely contributes to the apparent increase in MV yield observed for 27-3; however, other factors that may contribute to this phenotype await further investigation.

Deficiency of di-adenylyl cyclase or phosphodiesterase also alters MV yield.

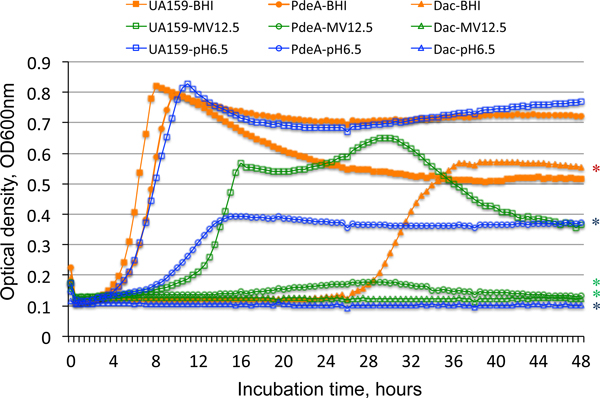

S. mutans di-adenylyl cyclase, encoded by dac, and phosphodiesterase, encoded by pdeA, have been shown to play important roles in modulation of c-di-AMP levels and the bacterial fitness and virulence (Peng, Michalek, & Wu, 2016; Peng, Zhang, Bai, Zhou, & Wu, 2016). Analysis of the mutants lacking these genes showed that when either dac or pdeA was deleted singly, MV yield as measured by BCA protein assay was significantly increased compared to the UA159 parent (Fig. 2) (P<0.001). In contrast, a ΔpdeA/dac double mutant displayed a far more modest increase in MV yield compared to UA159 (P<0.05). During growth in Bioscreen C under aerobic condition (with mineral oil overlay), the ΔpdeA mutant, and especially the Δdac mutant, also displayed notable growth defects, especially at pH 6.5 and in BHI containing methyl viologen, compared to the UA159 parent (Fig. 5). When grown in regular BHI broth, the doubling time for strain UA159 was approximately 90 minutes, while the ΔpdeA mutant had a 108 minute doubling time (P<0.05), and the Δdac mutant displayed an extended lag phase of more than 25 hours followed by a doubling time of 180 minutes (P<0.001). When grown in BHI adjusted to pH 6.5, the doubling time for UA159 was approximately 120 minutes, compared to 245 minutes for the ΔpdeA mutant (P<0.001), which also displayed decreased cell culture yield as measured by optical density (P<0.001). The Δdac mutant barely grew in BHI, pH 6.5. While UA159 displayed impaired growth in the presence of 12.5 mM methyl viologen, neither of the mutants grew at all under this condition (P<0.001).

Figure 5.

Evaluation of growth of Dac- and PdeA-deficient mutants. S. mutans wild-type UA159 and its targeted Δdac (Dac) and ΔpdeA (PdeA) mutants were grown aerobically at 37°C in regular BHI (in red), BHI adjusted to pH 6.5 (in blue), or BHI containing methyl viologen (12.5 mM) (in green) with the optical density at 600 nm being monitored continuously using a Bioscreen C. Data represent two independent sets of experiments. The results showed that relative to the wild-type (UA159), deficiency of pdeA (PdeA) and especially dac (Dac) led to major reduction in growth rate, especially when grown at pH 6.5 and in the presence of methyl viologen. Symbol * indicates significant differences when compared to UA159 under the same conditions, P<0.001.

eDNA-protein interactions in S. mutans biofilm matrices are influenced by pH.

Our previous studies showed that S. mutans MVs carry eDNA, although most of the MV-associated DNAs were found on the outer surface of the vesicles (Liao et al., 2014) (Morales-Aparicio et al., 2020). When analyzed by immunogold electron microscopy, reactivity of anti-dsDNA antibodies was detectable in 5-day biofilm matrices, but the signals were weak and limited in numbers (Fig. S11). This could be due in part to antigen masking and limited accessibility, likely stemming from previously identified eDNA-glucan and eDNA-protein interactions (Besingi et al., 2017; Liao et al., 2014). No anti-dsDNA antibody reactivity was detected inside the MVs following thin sectioning and /or de-roofing of the fixed MVs. The results further suggest that the MV-associated eDNA does not reside inside the vesicles.

Recent studies in S. aureus have shown that extracellular matrix proteins were associated with the bacterial cell surface at low pH in a so-called moonlighting phenomenon, a naturally occurring process during biofilm formation, but that the proteins were released when the biofilms were resuspended in buffer of neutral pH (Foulston, Elsholz, DeFrancesco, & Losick, 2014). eDNA is not required for the observed cell surface association (Dengler et al., 2015). Like S. aureus, a substantial amount of protein was released when S. mutans biofilms were suspended in buffer at pH 7.5 (Fig. 6A). In contrast, substantially less protein was visualized when the biofilms were suspended at pH 5.0. When cells were first exposed to pH 5.0, and subsequently resuspended at pH 7.5, there was a significant increase in the amount of protein released. This effect was not observed for cells that were exposed twice to pH 7.5. In fact, the amount of protein released decreased upon second exposure of the cells to pH 7.5, presumably because most of the proteins had already been released. When the same experiment was performed following incorporation of DNase I during biofilm cell growth, resuspension of harvested cells at either pH 5.0 or 7.5 resulted in substantial release of proteins (Fig. 6B). In this case, the amount of protein released from the cells upon subsequent resuspension at pH 7.5 was decreased irrespective of the buffer pH in which they had initially been resuspended. When biofilms were grown in the presence of DNase I, less protein was retained in the biofilm clusters under all conditions compared to biofilms that received no DNase I treatment. Moreover, qualitative differences appear to exist between the patterns of the separated proteins in TCA-precipitated samples following SDS-PAGE. These results suggest that the presence of eDNA inhibits matrix protein release from S. mutans biofilms, which differs from that reported for S. aureus (Dengler et al., 2015).

Figure 6.

Effect of pH and eDNA on extracellular protein release from S. mutans biofilm matrices. S. mutans strain UA159 was grown in biofilm medium for 24 hours on 24-well polystyrene plates with (A) or without (B) the addition of DNase I at 3 hours after the start of biofilm cultures. Biofilms were scraped in PBS with protein inhibitors cocktail, pH 7.5 and briefly sonicated as controls (C), and aliquots were then resuspended and incubated in PBS at the indicated pH. Released proteins were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining. Data shown are representative of two individual experiments.

Discussion

While the complete mechanism of vesiculogenesis remains unclear, the results presented here provide further evidence that like Gram-negative bacteria (Mashburn-Warren, McLean, & Whiteley, 2008; Schwechheimer & Kuehn, 2015; Volgers et al., 2018), multiple factors are involved in regulation of MV biogenesis in S. mutans. Among them are diadenylate cyclase (Dac) and the c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase (PdeA), two enzymes that regulate the level of c-di-AMP secondary message (Peng, Zhang, et al., 2016). As reported by Peng et al. (Peng, Michalek, et al., 2016; Peng, Zhang, et al., 2016), S. mutans c-di-AMP plays an important role in regulating diverse cellular pathways, including stress tolerance responses. Alterations in c-di-AMP levels influence bacterial cell growth, cell envelope homeostasis, acid tolerance, antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation and virulence. Consistently, both the Dac- and especially the PdeA-deletion mutants displayed major growth defects at low pH and in the presence of methyl viologen, a chemical commonly used to induce hydrogen peroxide production and oxidative stresses. Similar to Gram-negative bacteria, elevated MV yield by the Δdac and ΔpdeA mutants, but less so by the Δdac/ΔpdeA double mutant, also suggest that diminished environmental stress tolerance in response to the c-di-AMP alterations that stem from Dac- and/or PdeA-deficiency is among the underlying factors. Our early observations that the highest amount of cell lysis independent eDNA release was measured during exponential growth of S. mutans under iron limitation (Liao et al., 2014) also supports the notion that environmental conditions such as low pH and nutrient deficiency play a role in regulation of MV biogenesis.

Sfp is an enzyme that in Bacillus sp. is involved in biosynthesis of the antibiotic surfactin, whose deficiency leads to enhanced vesicle stability and accumulation of MVs, as well as defective biofilm formation (Brown et al., 2014). Unlike other oral streptococci and group A and B streptococci, S. mutans possesses an sfp within the TnSmu2 genomic island which also contains synthases and accessory factors for the biosynthesis of nonribosomal peptides and polyketides such as mutanobactin (Wu et al., 2010). While S. mutans is not known to produce surfactin, the S. mutans Sfp enzyme contributes to synthesis of mutanobactin, which is designated Mub in this context. Although not as striking as in Bacillus sp. (Brown et al., 2014), Sfp deficiency in S. mutans resulted in a measurably higher MV yield based on protein estimation. Unlike MVs from Bacillus sp., the S. mutans sfp deletion mutant demonstrated only a modest difference in MV stability following lipid dye staining and assessed by flow cytometry. The stability of S. mutans MVs from both the wild-type and the Δsfp strains was temperature-dependent as the number of fluorescent particulates did not decrease following incubation at room temperature. Of note, Sfp deficiency is associated with major alterations in the S. mutans MV proteome, and particularly lipidome, in comparison to those of the wild-type parent strain (Morales-Aparicio et al., 2020). In addition, the proteomes and lipidomes of S. mutans MVs compared to cytoplasmic membrane preparations derived from the same cultures are markedly different, and these differences are altered when sfp is deleted compared to the wild-type strain. Such protein and lipid differences may impact the stability and other properties of MVs from the Sfp-deficient strain, although the exact mechanisms await further investigation. Also of note, the flavonoid and polyketide composition of the S. mutans MVs was altered in the absence of Sfp. Because lipids, flavonoids and polyketides can all affect protein quantification by assays such as BCA, it is important to recognize that while commonly used in the study of MVs, this indirect measure of MV yield may not reflect the total number of MV particles produced by a given bacterial strain. Protein measurement is however at a minimum a valid indication of qualitative, if not quantitative, differences in MV biogenesis among strains. Sfp deficiency in S. mutans has no apparent effect on growth of the deletion mutant under non-stress conditions in rich medium, but the ability of the Δsfp strain to survive low pH and hydrogen peroxide challenge, major environmental stressors that S. mutans encounters frequently within the dental plaque, were significantly reduced. Considering the contribution of environmental stressors to MV production in Gram-negative bacteria (Mashburn-Warren et al., 2008; Schwechheimer & Kuehn, 2015; Volgers et al., 2018), reduced survival under low pH and oxidative stress conditions is consistent with our result that Sfp deficiency also impacts S. mutans MV biogenesis. While the Sfp deletion strain appeared to form less biofilms on hydroxylapatite discs when examined using confocal microscopy or SEM, the differences in a 96-well plate assay were not statistically significant. The increased MV yield, coupled with a possible diminution in biofilm formation, suggests that similar to observations in Bacillus spp (Brown et al., 2014), MVs from the S. mutans Δsfp strain may not be as effective in supporting biofilm development as those from the wild-type strain, and will be the focus of future studies.

In S. mutans, the sfp gene is clustered with other genes involved in biosynthesis of a yellowish pigment termed mutanobactin (Mub), a complex nonribosomal/polyketide peptide, deficiency of which has been shown to cause a defect in oxidative stress tolerance that results in growth retardation under aerobic conditions and in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (Wu et al., 2010). Interestingly, while this gene cluster is prevalent in sequenced S. mutans genomes, differences exist among strains in both the sequences of the genes themselves as well as in their organization and location. Thus, the discrepancy with respect to the observed differences in MV yield between natural isolates deficient in BacA, a surfactin biosynthetase homolog, and a deliberately engineered ΔbacA mutant of UA159, may be attributable to such genetic divergence. The colony morphology of clinic strain 27-3 is more similar to that of strain UA140 than that of strain UA159. Consistent with this finding, comparative genomics also revealed major differences in the genome sequences of strain 27-3 compared to UA159. Additional factors that may contribute to the apparent high level of MV production in this clinic strain await further investigation.

In Streptococcus pyogenes, the two-component system CovSR is known to play an important role in regulation of virulence expression. Recent studies by Resch et al. have shown that CovSR also negatively regulates the production of MVs in S. pyogenes, and such regulation is independent of cysteine protease SpeB and capsule biosynthesis (Resch et al., 2016). Blast search of the S. mutans genome, reveals that the two-component system with the most similarity to S. pyogenes CovSR is the VicSR system (Stipp et al., 2013), while orphan regulator CovR for its high similarity to the S. pyogenes homologue has been well documented (Biswas & Biswas, 2006; Stipp et al., 2013). An S. mutans allelic exchange mutant lacking the VicSR system was constructed and analyzed for the impact of VicSR deficiency on MV production in S. mutans, but no significant differences in MV yield between the mutant and its parent strain were observed. S. mutans CovR is involved in regulation of a large number of genes, including repression of those encoding glucosyltransferases B and C, as well as glucan binding protein C (Biswas & Biswas, 2006; Dmitriev et al., 2011; Stipp et al., 2013). An allelic exchange deletion mutant lacking CovR was made, but again no significant difference was observed in MV yield between this mutant and its parent strain. Taken together these results suggest that unlike S. pyogenes, S. mutans CovR-like regulators do not have a major impact on total MV yield, although their impact on content or functional attributes of the vesicles remains to be determined.

We and others have shown S. mutans eDNA to be a major constituent of the biofilm matrix and to play a significant role in biofilm formation and stability (Besingi et al., 2017; Das, Sharma, Krom, van der Mei, & Busscher, 2011; Liao et al., 2014). Our previous electron microscopy images of S. mutans biofilms identified eDNA nanofibers in a well-structured network with the ends of the fibers connected to both cells and substratum (Liao et al., 2014). Consistent with previous findings, current results of immunogold labelling electron microscopy also provided evidence of eDNA within the biofilm matrix. Our previous in vitro studies also showed that in the presence of eDNA and glucans, bacterial colonization was enhanced compared to eDNA alone or glucans alone (Liao et al., 2014). These results are strongly suggestive of interactions between eDNA and glucans that impact bacterial adherence and biofilm formation. In S. aureus, extracellular matrix proteins are reported to associate with the bacterial cell envelope at low pH, with increased pH significantly enhancing matrix protein release from the biofilm clusters (Dengler et al., 2015; Foulston et al., 2014). Similar to S. aureus, more proteins were released when S. mutans biofilms were resuspended in buffer of neutral pH rather than acidic pH. In contrast to S. aureus, however, this effect was not observed when S. mutans biofilms were treated with or grown in the presence of DNase I that would hydrolyze the DNA component within the matrix. These findings reinforce the notion that eDNA and proteins interact within S. mutans biofilms (Besingi et al., 2017), and further suggest that the presence of eDNA can significantly diminish the release of extracellular matrix proteins.

Our early studies showed that, like Gram-negative bacteria, S. mutans MVs carry known virulence factors including the multi-functional adhesin P1, glucosyltransferase GtfB and Glucan-binding protein GbpC (Liao et al., 2014). Our recent MV proteomic analysis revealed the presence of additional factors known to contribute to bacterial adherence and biofilm formation, a trait critical to the pathogenicity of the bacterium. These include surface protein WapA, GtfB, C and D, GbpB, C, and D, fructanase FruA, and fructosyltranferase Ftf, and bacteriocin. (Morales-Aparicio et al., 2020). In addition, prominent components of S. mutans MVs were the AtlA autolysin (Ahn & Burne, 2006) and the negative regulator of competence and biofilm cell density, Smu_63C (Besingi et al., 2017). Thus S. mutans MVs deliver to the extracellular environment multiple cargo proteins that support cell envelope and biofilm architecture, as well as those that enhance competitive fitness compared to other oral microorganisms. Similar to other bacteria, including Gram-positive species (Barnes, Ballering, Leibman, Wells, & Dunny, 2012; Jiang et al., 2014; Whitchurch et al., 2002), S. mutans MVs also carry eDNA, although the most eDNA are localized to the outside of the bilayered vesicles (Liao et al., 2014) (Morales-Aparicio et al., 2020). Sucrose-independent adhesins like P1 and WapA, in concert with sucrose-dependent adherence mediated by Gtf enzymes, especially GtfB, that produce adhesive glucose polymers with sucrose as a substrate, ensure that S. mutans is able to adhere to tooth surfaces in tenacious biofilms that resist physical disruption. S. mutans GftB can also bind to the surface of other bacteria associated with dental caries within polymicrobial consortia such as L. casei and Candida albicans (Gregoire et al., 2011; Wen et al., 2017). Other macromolecular interactions, such as between eDNA and glucan, also facilitate S. mutans adherence and biofilm development (Liao et al., 2014). The results presented in the current study demonstrate that the presence of eDNA diminishes protein release from S. mutans biofilms, reiterating the importance of eDNA-protein interactions within the biofilm matrix. While all underlying mechanisms remain unclear, S. mutans eDNA is integral to bacterial adherence to surfaces, intercellular adherence, biofilm formation, and biofilm stability (Liao et al., 2014). Taken together, previous and current results demonstrate that S. mutans MVs significantly enhance S. mutans biofilm formation, especially in the presence of sucrose, and their effects are likely enhanced as a result of eDNA-protein and eDNA-glucan interactions.

In summary, the results presented herein demonstrate that S. mutans MV biogenesis is regulated, likely through the concerted functions of multiple factors, in response to environmental cues. As such, they would have significant impacts on the ability of S. mutans to colonize and accumulate on the tooth surface, and cause carious diseases. Current effort is directed to further evaluation of factors underlying the process of S. mutans vesiculogenesis, as well as mechanisms involved in the contributions of eDNA to colonization and biofilm formation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Sara Palmer at the Division of Biosciences, School of Dentistry, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, and Dr. Justin Merritt at the Department of Restorative Dentistry, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR for providing some of S. mutans strains used in this study and for their expert insights in related aspects. We also thank Ms. Joyce C. Morales-Aparicio at the University of Florida College of Dentistry, Gainesville, FL for technical discussions and editorial input, and Dr. Dorota D. Wyczechowska at School of Medicine, the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center and Louisiana Cancer Research Center, New Orleans, LA for her expert assistance on flow cytometry. This work was supported in part by NIH/NIDCR grants DE025438 to ZTW and LJB and DE19452 to ZTW.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest with this manuscript and have no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- Ahn SJ, & Burne RA (2006). The atlA operon of Streptococcus mutans: role in autolysin maturation and cell surface biogenesis. J. Bacteriol, 188(19), 6877–6888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn SJ, Wen ZT, Brady LJ, & Burne RA (2008). Characteristics of biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans in the presence of saliva. Infect Immun, 76(9), 4259–4268. doi:IAI.00422-08 [pii] 10.1128/IAI.00422-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes AM, Ballering KS, Leibman RS, Wells CL, & Dunny GM (2012). Enterococcus faecalis produces abundant extracellular structures containing DNA in the absence of cell lysis during early biofilm formation. MBio, 3(4), e00193–00112. doi:mBio.00193-12 [pii] 10.1128/mBio.00193-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besingi RN, Wenderska IB, Senadheera DB, Cvitkovitch DG, Long JR, Wen ZT, & Brady LJ (2017). Functional Amyloids in Streptococcus mutans, their use as Targets of Biofilm Inhibition and Initial Characterization of SMU_63c. Microbiology, 163(4):488–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S, & Biswas I. (2006). Regulation of the glucosyltransferase (gtfBC) operon by CovR in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol, 188(3), 988–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitoun JP, Liao S, McKey BA, Yao X, Fan Y, Abranches J, . . . Wen ZT (2013). Psr is involved in regulation of glucan production, and double deficiency of BrpA and Psr is lethal in Streptococcus mutans. Microbiology, 159(3), 493–506. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.063032-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen WH, Burne RA, Wu H, & Koo H. (2017). Oral Biofilms: Pathogens, Matrix, and Polymicrobial Interactions in Microenvironments. Trends Microbiol. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen WH, & Koo H. (2011). Biology of Streptococcus mutans-Derived Glucosyltransferases: Role in Extracellular Matrix Formation of Cariogenic Biofilms. Caries Res, 45(1), 69–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L, Kessler A, Cabezas-Sanchez P, Luque-Garcia JL, & Casadevall A. (2014). Extracellular vesicles produced by the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis are disrupted by the lipopeptide surfactin. Mol Microbiol, 93(1), 183–198. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burne RA, Abranches J, Ahn SJ, Lemos JA, Wen ZT, & Zeng L. (2011). Functional Genomics of Streptococcus mutans. In Kolenbrander PE (Ed.), Oral Microbial Communities: Genomic Inquires and Interspecies Communication. (pp. 185–204): ASM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley PJ, Brady LJ, Michalek SM, & Bleiweis AS (1999). Virulence of a spaP mutant of Streptococcus mutans in a gnotobiotic rat model. Infect. Immun, 67(3), 1201–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das T, Sharma PK, Krom BP, van der Mei HC, & Busscher HJ (2011). Role of eDNA on the adhesion forces between Streptococcus mutans and substratum surfaces: influence of ionic strength and substratum hydrophobicity. Langmuir, 27(16), 10113–10118. doi: 10.1021/la202013m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De A, Liao S, Bitoun JP, Roth R, Beatty WL, Wu H, & Wen ZT (2017). Deficiency of RgpG Causes Major Defects in Cell Division and Biofilm Formation, and Deficiency of LytR-CpsA-Psr Family Proteins Leads to Accumulation of Cell Wall Antigens in Culture Medium by Streptococcus mutans. Appl Environ Microbiol, 83(17). doi: 10.1128/AEM.00928-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rond L, van der Pol E, Hau CM, Varga Z, Sturk A, van Leeuwen TG, . . . Coumans FAW (2018). Comparison of Generic Fluorescent Markers for Detection of Extracellular Vesicles by Flow Cytometry. Clin Chem, 64(4), 680–689. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.278978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dengler V, Foulston L, DeFrancesco AS, & Losick R. (2015). An Electrostatic Net Model for the Role of Extracellular DNA in Biofilm Formation by Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol, 197(24), 3779–3787. doi: 10.1128/JB.00726-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitriev A, Mohapatra SS, Chong P, Neely M, Biswas S, & Biswas I. (2011). CovR-controlled global regulation of gene expression in Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One, 6(5), e20127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulston L, Elsholz AK, DeFrancesco AS, & Losick R. (2014). The extracellular matrix of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms comprises cytoplasmic proteins that associate with the cell surface in response to decreasing pH. MBio, 5(5), e01667–01614. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01667-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorgens A, Bremer M, Ferrer-Tur R, Murke F, Tertel T, Horn PA, . . . Giebel B. (2019). Optimisation of imaging flow cytometry for the analysis of single extracellular vesicles by using fluorescence-tagged vesicles as biological reference material. J Extracell Vesicles, 8(1), 1587567. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2019.1587567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire S, Xiao J, Silva BB, Gonzalez I, Agidi PS, Klein MI, . . . Koo H. (2011). Role of Glucosyltransferase B in Interactions of Candida albicans with Streptococcus mutans and with an Experimental Pellicle on Hydroxyapatite Surfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol, 77(18), 6357–6367. doi:AEM.05203-11 [pii] 10.1128/AEM.05203-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Palmer SR, Ahn SJ, Richards VP, Williams ML, Nascimento MM, & Burne RA (2016). A Highly Arginolytic Streptococcus Species That Potently Antagonizes Streptococcus mutans. Appl Environ Microbiol, 82(7), 2187–2201. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03887-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung C, Zhou Y, Pinkner JS, Dodson KW, Crowley JR, Heuser J, . . . Hultgren SJ (2013). Escherichia coli biofilms have an organized and complex extracellular matrix structure. MBio, 4(5), e00645–00613. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00645-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Kong Q, Roland KL, & Curtiss R 3rd. (2014). Membrane vesicles of Clostridium perfringens type A strains induce innate and adaptive immunity. Int J Med Microbiol, 304(3–4), 431–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaparakis-Liaskos M, & Ferrero RL (2015). Immune modulation by bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Nat Rev Immunol, 15(6), 375–387. doi: 10.1038/nri3837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau PCY, Sung CK, Lee JH, Morrison DA, & Cvitkovitch DG (2002). PCR ligation mutagenesis in transformable streptococci: application and efficiency. J. Microbiol. Methods, 49, 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBanc D, & Lee L. (1991). Replication function of pVA380–1. In Dunny G, Cleary PP, & Mckay LL (Eds.), Genetics and Molecular Biology of Streptococci, Lactococci, and Enterococci. (pp. 235–239). Washington, DC.: ASM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee EY, Choi DY, Kim DK, Kim JW, Park JO, Kim S, . . . Gho YS (2009). Gram-positive bacteria produce membrane vesicles: proteomics-based characterization of Staphylococcus aureus-derived membrane vesicles. Proteomics, 9(24), 5425–5436. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Jun SH, Choi CW, Kim SI, Lee JC, & Shin JH (2018). Salt stress affects global protein expression profiles of extracellular membrane-derived vesicles of Listeria monocytogenes. Microb Pathog, 115, 272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.12.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos JA, Palmer SR, Zeng L, Wen ZT, Kajfasz JK, Freires IA, . . . Brady LJ (2019). The Biology of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol Spectr, 7(1). doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0051-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao S, Klein MI, Heim KP, Fan Y, Bitoun JP, Ahn SJ, Burne RA, Brady LJ, Wen ZT (2014). Streptococcus mutans extracellular DNA is upregulated during growth in biofilms, actively released via membrane vesicles, and influenced by components of the protein secretion machinery. J Bacteriol, 196(13), 2355–2366. doi: 10.1128/JB.01493-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo CY, Corliss DA, & Ganeshkumar N. (2000). Streptococcus gordonii biofilm formation: identification of genes that code for biofilm phenotypes. J. Bacteriol, 182(5), 1374–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashburn LM, & Whiteley M. (2005). Membrane vesicles traffic signals and facilitate group activities in a prokaryote. Nature, 437(7057), 422–425. doi: 10.1038/nature03925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashburn-Warren L, McLean RJ, & Whiteley M. (2008). Gram-negative outer membrane vesicles: beyond the cell surface. Geobiology, 6(3), 214–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2008.00157.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Aparicio JC, Lara Vasquez P, Mishra S, Barrán-Berdón AL, Kamat M, Basso KB, Wen ZT and Brady LJ (2020) The Impacts of Sortase A and the 4′-Phosphopantetheinyl Transferase Homolog Sfp on Streptococcus mutans Extracellular Membrane Vesicle Biogenesis. Front. Microbiol 11:570219. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.570219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obana N, Nakao R, Nagayama K, Nakamura K, Senpuku H, & Nomura N. (2017). Immunoactive Clostridial Membrane Vesicle Production Is Regulated by a Sporulation Factor. Infect Immun, 85(5). doi: 10.1128/IAI.00096-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer SR, Miller JH, Abranches J, Zeng L, Lefebure T, Richards VP, . . . Burne RA (2013). Phenotypic heterogeneity of genomically-diverse isolates of Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One, 8(4), e61358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Michalek S, & Wu H. (2016). Effects of diadenylate cyclase deficiency on synthesis of extracellular polysaccharide matrix of Streptococcus mutans revisit. Environ Microbiol, 18(11), 3612–3619. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Zhang Y, Bai G, Zhou X, & Wu H. (2016). Cyclic di-AMP mediates biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol, 99(5), 945–959. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin TJ, Theodore TS, & Cole RM (1971). Electron microscopy during release and purification of mesosomal vesicles and protoplast membranes from Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol, 107(3), 907–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainey K, Michalek SM, Wen ZT, & Wu H. (2019). Glycosyltransferase-Mediated Biofilm Matrix Dynamics and Virulence of Streptococcus mutans. Appl Environ Microbiol, 85(5). doi: 10.1128/AEM.02247-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath P, Huang C, Wang T, Wang T, Li H, Prados-Rosales R, . . . Nathan CF (2013). Genetic regulation of vesiculogenesis and immunomodulation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 110(49), E4790–4797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320118110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remis JP, Wei D, Gorur A, Zemla M, Haraga J, Allen S, . . . Auer M. (2014). Bacterial social networks: structure and composition of Myxococcus xanthus outer membrane vesicle chains. Environ Microbiol, 16(2), 598–610. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resch U, Tsatsaronis JA, Le Rhun A, Stubiger G, Rohde M, Kasvandik S, . . . Charpentier E. (2016). A Two-Component Regulatory System Impacts Extracellular Membrane-Derived Vesicle Production in Group A Streptococcus. MBio, 7(6). doi: 10.1128/mBio.00207-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera J, Cordero RJ, Nakouzi AS, Frases S, Nicola A, & Casadevall A. (2010). Bacillus anthracis produces membrane-derived vesicles containing biologically active toxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 107(44), 19002–19007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008843107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooling SR, & Beveridge TJ (2006). Membrane vesicles: an overlooked component of the matrices of biofilms. J Bacteriol, 188(16), 5945–5957. doi: 10.1128/JB.00257-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooling SR, Hubley A, & Beveridge TJ (2009). Interactions of DNA with biofilm-derived membrane vesicles. J Bacteriol, 191(13), 4097–4102. doi: 10.1128/JB.00717-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwechheimer C, & Kuehn MJ (2015). Outer-membrane vesicles from Gram-negative bacteria: biogenesis and functions. Nat Rev Microbiol, 13(10), 605–619. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipp RN, Boisvert H, Smith DJ, Hofling JF, Duncan MJ, & Mattos-Graner RO (2013). CovR and VicRK regulate cell surface biogenesis genes required for biofilm formation in Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One, 8(3), e58271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terleckyj B, Willett NP, & Shockman GD (1975). Growth of several cariogenic strains of oral streptococci in a chemically defined medium. Infect. Immun, 11(4), 649–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volgers C, Savelkoul PHM, & Stassen FRM (2018). Gram-negative bacterial membrane vesicle release in response to the host-environment: different threats, same trick? Crit Rev Microbiol, 44(3), 258–273. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2017.1353949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen ZT, Baker HV, & Burne RA (2006). Influence of BrpA on critical virulence attributes of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol, 188(8), 2983–2992. R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen ZT, & Burne RA (2001). Construction of a new integration vector for use in Streptococcus mutans. Plasmid, 45, 31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen ZT, & Burne RA (2002). Functional genomics approach to identifying genes required for biofilm development by Streptococcus mutans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol, 68(3), 1196–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen ZT, & Burne RA (2004). LuxS-mediated signaling in Streptococcus mutans is involved in regulation of acid and oxidative stress tolerance and biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol, 186(9), 2682–2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen ZT, Liao S, Bitoun JP, De A, Jorgensen A, Feng S, Xu X, Chain PSG, Caufield PW, Li Y. (2017). Streptococcus mutans Displays Altered Stress Responses While Enhancing Biofilm Formation by Lactobacillus casei in Mixed-Species Consortium. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 7, 524. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen ZT, Yates D, Ahn SJ, & Burne RA (2010). Biofilm formation and virulence expression by Streptococcus mutans are altered when grown in dual-species model. BMC Microbiol, 10, 111. doi:1471-2180-10-111 [pii] 10.1186/1471-2180-10-111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitchurch CB, Tolker-Nielsen T, Ragas PC, & Mattick JS (2002). Extracellular DNA required for bacterial biofilm formation. Science, 295(5559), 1487. doi: 10.1126/science.295.5559.1487295/5559/1487 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DW, Elliott SR, Odean E, Bemis LT, & Tischler AD (2018). Mycobacterium tuberculosis Pst/SenX3-RegX3 Regulates Membrane Vesicle Production Independently of ESX-5 Activity. MBio, 9(3). doi: 10.1128/mBio.00778-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Cichewicz R, Li Y, Liu J, Roe B, Ferretti J, Merritt J, Qi F. (2010). Genomic island TnSmu2 of Streptococcus mutans harbors a nonribosomal peptide synthetase-polyketide synthase gene cluster responsible for the biosynthesis of pigments involved in oxygen and H2O2 tolerance. Appl Environ Microbiol, 76(17), 5815–5826. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03079-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L, Wen ZT, & Burne RA (2006). A novel signal transduction system and feedback loop regulate fructan hydrolase gene expression in Streptococcus mutans. Mol. Microbiol, 62(1), 187–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.