Introduction

Syphilis is known as the “great imitator” for its varied clinical manifestations. The historically low rate of syphilis in the United States in the early 2000s has been followed by an epidemic of primary and secondary (P&S) infections, with a 71.4% increase between 2014 and 2018 (10.8 vs 6.3 cases per 100,000).1 In 2018, about 85.7% of all reported cases of P&S syphilis were observed in men, most of whom were men who have sex with men.1 Rates of P&S syphilis also increased by 30.4% in women between 2017 and 2018.1 In this case series, we describe 9 patients with condyloma lata (CL) seen in our tertiary academic medical center inpatient dermatology service between May 2015 and December 2018.

Case series

Between May 2015 and December 2018, our inpatient dermatology service was consulted on 12 patients for skin manifestations, which were ultimately diagnosed as secondary syphilis. Nine of 12 patients' primary manifestation of syphilis were CL. Five of the 9 patients diagnosed with CL were seen between July and September 2018. The onset of the lesions reported by the patients before hospital presentation ranged from 1 to 12 weeks (median, 3.5 weeks). Six of 9 patients presented between January and September 2018 and 5 of these 6 patients presented between July and September 2018. The patient age range was 22-50 years (median, 40 years) with a 5:4 male-to-female ratio. Patients were admitted to the hospital due to painful, worsening anogenital lesions (6/9), concern for neurosyphilis (1/9 presented with headache; 1/9 presented with hemifacial weakness and numbness), and congestive heart failure exacerbation (1/9), during which time our dermatology service was consulted.

Seven of the 9 patients reported homelessness. Eight of the 9 patients reported intravenous methamphetamine use. One patient with HIV diagnosed with AIDS on admission denied drug use. Four patients reported a partner with multiple sexual partners, 2 patients reported having multiple sexual partners of their own, and 3 patients reported having neither. Male patients denied having sex with other men. One patient was treated with 2 courses of acyclovir for presumptive genital herpes simplex virus infection in the 3 weeks before admission. Two patients were treated for an unknown sexually transmitted disease with unknown treatment one month before admission.

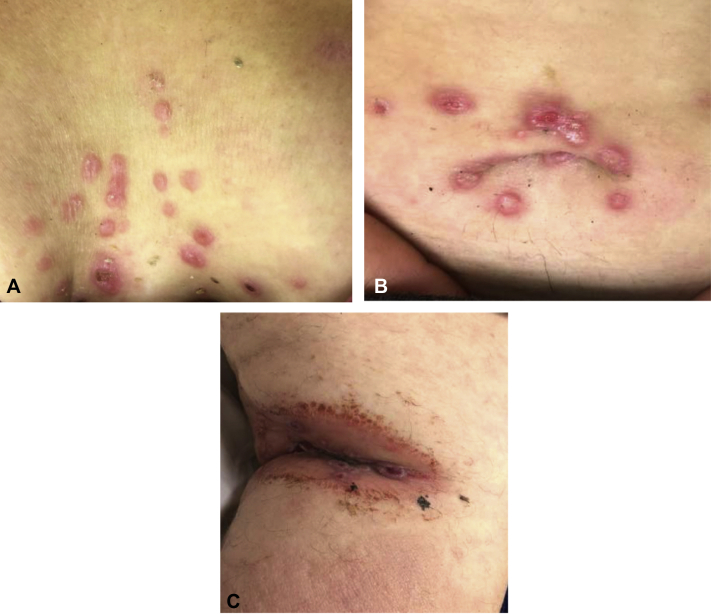

All 9 patients presented with moist appearing hypertrophic anogenital lesions (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Condyloma lata of the vulva.

Additionally, 2 patients also presented with umbilical lesions, with 1 of these 2 patients also presenting with CL of the groin, popliteal fossa, and chest as well as hard palate erosions (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Condyloma lata. Multiple eroded, smooth, pink-white papules on the chest A, umbilicus B, popliteal fossa (C).

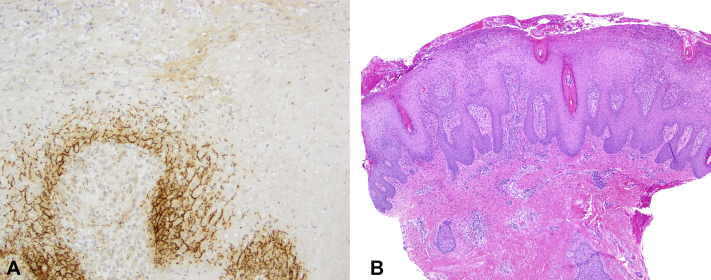

Two patients presented with a characteristic diffuse scaly maculopapular rash on the trunk and extremities. All 9 patients had reactive rapid plasma reagin ranging from 1:64 to 1:1024 (median 1:128). Six biopsies from 6 patients were confirmed to have syphilis by T. pallidum immunohistochemistry (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Histopathology of condyloma lata. A, Parakeratosis with neutrophilic crust, eroded irregular epidermal hyperplasia with hypogranulosis and superficial pallor, and a dense perivascular infiltrate with numerous neutrophils and plasma cells (original magnification, 40×) B, T. pallidum immunohistochemical testing revealed numerous spirochetal forms.

Six of 9 patients tested for syphilis immunoglobulins were positive for syphilis IgG antibodies. Seven of 9 patients were treated with one dose of intramuscular penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million units). Two of 9 patients received IV Penicillin G while being worked up for possible neurosyphilis and were eventually confirmed negative by CSF testing. All patients were advised to follow up for monitoring of rapid plasma reagin titers; however, no notes were available in our medical records for such visits for any of the patients. It is unknown whether the patients followed up elsewhere in the community.

Discussion

CL are highly infectious, flat-topped, well-demarcated hypertrophic papules or plaques, which often present in intertriginous areas, such as the genitals and anus, but also in other areas such as the nasolabial folds, axilla, umbilicus, web space between toes, palate, ankle, and neck.2, 3, 4 CL may resemble other anogenital lesions such as Buschke-Lowentsein tumors, condyloma acuminata, malignant tumors, or genital herpes. CL are usually diagnosed by their characteristic physical appearance confirmed by darkfield microscopy and/or skin biopsy along with serological tests.

CL have been reported to occur in about 6%-23% of patients with secondary syphilis.3,5, 6, 7, 8 While the anogenital chancres of primary syphilis are usually painless, CL of secondary syphilis can be painful. It is important to note that chancres can occasionally be painful and can also present as multiple lesions, especially in patients who have HIV.6 Furthermore, the chancre of primary syphilis can also be present during the secondary stage of syphilis.6

Seventy five percentage of patients with secondary syphilis on our inpatient service presented with CL, which may have been related to various factors, including environmental influences, socioeconomic status, a variant strain of syphilis, and methamphetamine use. Moisture, heat, and friction of intertriginous areas are thought to perpetuate the growth and coalescence of syphilitic papules during the secondary stage, leading to plaque-like condylomas.3 Since many of the patients presented during warmer months, it is possible that chafing of intertriginous areas in hot weather ultimately led to the development of CL. The presence of anti-syphilis IgG antibodies suggests that the patients likely had syphilis for a longer period of time than reported, thus the characteristic maculopapular rash of secondary syphilis may have been present at some point. Homelessness is also associated with decreased access to healthcare,9 and delayed treatment in our patient population may have played a role in the perpetuation of syphilitic papules.

The unusually high incidence of CL in our patients suggests the possibility that a specific strain of T. pallidum may have played a role, as variations of T. pallidum have been reported.10 Limited data has shown T. pallidum strains associated with neurosyphilis, but not ocular syphilis.11,12 Most contemporary syphilis strains have been found to be members of an azithromycin-resistant pandemic strain cluster, which emerged from a common ancestor strain in the mid-twentieth century.10 Additional research is necessary to determine the relationship between the clinical presentation of syphilis and the T. pallidum subtype.

It is unclear whether methamphetamine use contributed to the formation of CL in particular. Our patients had many risk factors predisposing them to contracting syphilis. The increased incidence of heterosexual syphilis in the United States is thought to be associated with the increase in percentage of persons with P&S syphilis reporting use of methamphetamine, injection drugs, and heroin, as well as sex with a person who injects drugs.13 Methamphetamine use likely played a role in unsafe sexual practices, and is associated with an increased risk of sexually transmitted diseases including syphilis.14 Methamphetamines have been detected in sweat glands 2 hours after use and up to 1 week after multiple uses; however, the direct effects of methamphetamines on the skin's microbiome or metabolites are still not known.14 Methamphetamine-induced immunosuppression predisposes the host to contracting progressive diseases such as HIV14; however, this impact remains to be explored in the pathogenesis of syphilis.

While the unique characteristics of our patient population may not necessarily be generalizable, there are several key points that are of value for every clinician. It is important to recognize the rising rates of P&S syphilis nationally and worldwide and to consider syphilis in the differential diagnosis of skin conditions. While secondary syphilis typically presents with a diffuse maculopapular rash, CL may be the only manifestation of secondary syphilis and may also present in extragenital locations. Flat-topped papules in intertriginous areas may also be a diagnostic clue for CL. A thorough social history is important, given the increased prevalence of methamphetamine use and cases of heterosexual syphilis. A dermatologist can play a key role in early diagnosis of syphilis, facilitating prompt treatment and preventing disease transmission in communities.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

References

- 1.CDC . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta: 2019. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minkin W., Landy S.E., Cohen H.J. An unusual solitary lesion of secondary syphilis. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pavithran K. Solitary condyloma latum on the umbilicus. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:597–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1992.tb02729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Z., Wang L., Zhang G., Long H. Warty mucosal lesions: oral condyloma lata of secondary syphilis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:277. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.191129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapel T.A. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161–164. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198010000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rompalo A.M., Joesoef M.R., O'Donnell J.A. Clinical manifestations of early syphilis by HIV status and gender: results of the syphilis and HIV study. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:158–165. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200103000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mindel A., Tovey S.J., Timmins D.J., Williams P. Primary and secondary syphilis, 20 years' experience. 2. Clinical features. Genitourin Med. 1989;65:1–3. doi: 10.1136/sti.65.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magdaleno-Tapial J., Hernández-Bel P., Valenzuela-Oñate C., Miquel VA-d. Whitish dots provide the key to diagnosing condyloma lata: a report of 5 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:892–895. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2019.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baggett T.P., O'Connell J.J., Singer D.E., Rigotti N.A. The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: a national study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1326–1333. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng R.R., Wang A.L., Li J., Tucker J.D., Yin Y.P., Chen X.S. Molecular typing of Treponema pallidum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marra C.M., Sahi S.K.S., Tantalo L.C. Enhanced molecular typing of Treponema pallidum: geographical distribution of strain types and association with neurosyphilis. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1380–1388. doi: 10.1086/656533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliver S., Sahi S.K., Tantalo L.C. Molecular typing of Treponema pallidum in ocular syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43:524–527. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kidd S.E., Grey J.A., Torrone E.A., Weinstock H.S. Increased methamphetamine, injection drug, and heroin use Among women and heterosexual men with primary and secondary syphilis–United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:144–148. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salamanca S.A., Sorrentino E.E., Nosanchuk J.D., Martinez L.R. Impact of methamphetamine on infection and immunity. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:445. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]