Abstract

Background:

X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (XLRP) is a hereditary retinopathy that may present with cystoid macular edema (CME). The exact cause of CME in XLRP is unknown. We describe a case report of new onset CME precipitated by travel to high altitude in an adult with XLRP, but no known prior history of CME.

Case Description:

A 38-year-old man with XLRP caused by a hemizygous pathogenic variant in RPGR (c.372del; p.Glu125fs) reported sudden onset bilateral blurry vision 4 days after ascending to an altitude of 3,700 meters. He sought local ophthalmic care and was found to have severe bilateral CME. He was treated with topical and oral carbonic anhydrase inhibition and instructed to return to normal altitude. Follow-up imaging at normal altitude revealed that the CME was nearly completely resolved 4 days after initial presentation, and completely resolved 2 weeks after initial presentation.

Conclusion:

Vascular and metabolic changes caused by retinal degeneration in XLRP may predispose to development of CME under the hypoxic conditions experienced at high altitudes. We advise that retinal specialists treating patients with RP should caution them on traveling to high altitudes that could precipitate or exacerbate CME.

Introduction

Cystoid macular edema (CME) has been reported in up to 50% of patients with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) (1). The exact cause of RP-CME remains unknown and may be multifactorial (1). In the healthy retina, severe altitude-related changes typically do not occur until extreme altitudes above 7,500 meters. Here we describe a case of bilateral CME that developed acutely in a patient with X-linked RP (XLRP) after hiking at an altitude of 3,700 meters.

Case Description

A 38-year-old man with history of XLRP since age 6 presented with sudden onset blurry vision in both eyes after hiking at an elevation of 3,700 meters for 4 days. Clinical genetic testing had shown a hemizygous pathogenic variant in RPGR: c.372del (p.Glu125fs). He was otherwise healthy and denied history of hypertension or diabetes, and was not taking any systemic medications. Baseline best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) prior to presentation had been 20/40 in both eyes. On presentation, BCVA was 20/60 in both eyes. He had no prior history of CME and denied symptoms of altitude sickness. Anterior segment exam revealed mild bilateral posterior subcapsular cataracts. Fundus exam (Figure 1A and 1B) showed features of RP: optic disc pallor, attenuated retinal vessels, and bone spicule pigmentation in the mid-periphery. Fluorescein angiography showed late leakage of the bilateral optic discs (Figure 1C and 1D). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed bilateral intra-retinal fluid, right greater than left retinoschisis-like cavities, and mild left subretinal fluid, with central subfield thickness (CST) of 518 microns in the right eye and 294 microns in the left (Figure 2A and 2B). He was started on oral acetazolamide and topical dorzolamide, and returned home to a normal elevation of approximately 250 meters.

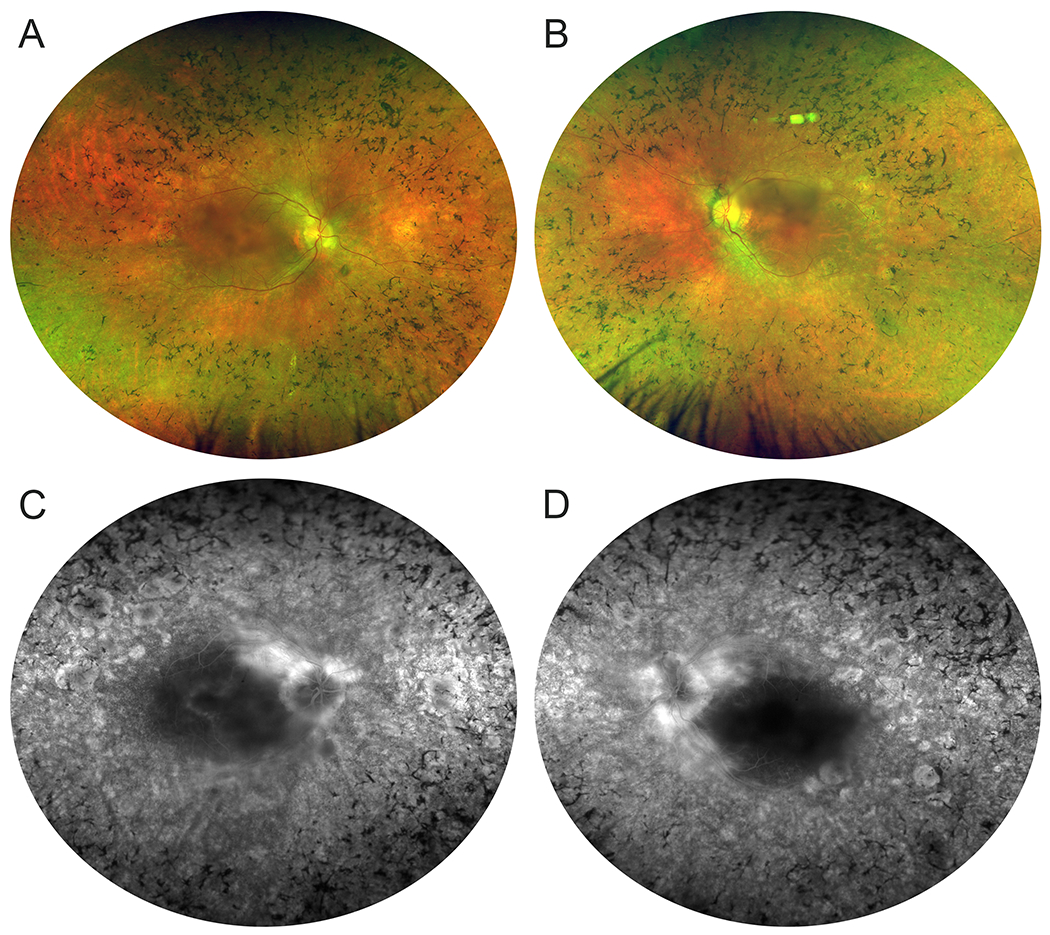

Figure 1.

A, B. Fundus imaging showing classic features of retinitis pigmentosa including waxy pallor of the optic discs, retinal vessel attenuation, and circumferential bone spicule pigmentation. Also notable is mild central media opacity caused by mild bilateral posterior subcapsular cataracts. C, D. Fluorescein angiography showing bilateral late disc leakage without macular leakage. In the right eye there are parafoveal window defects corresponding with areas of retinal pigment epithelium atrophy.

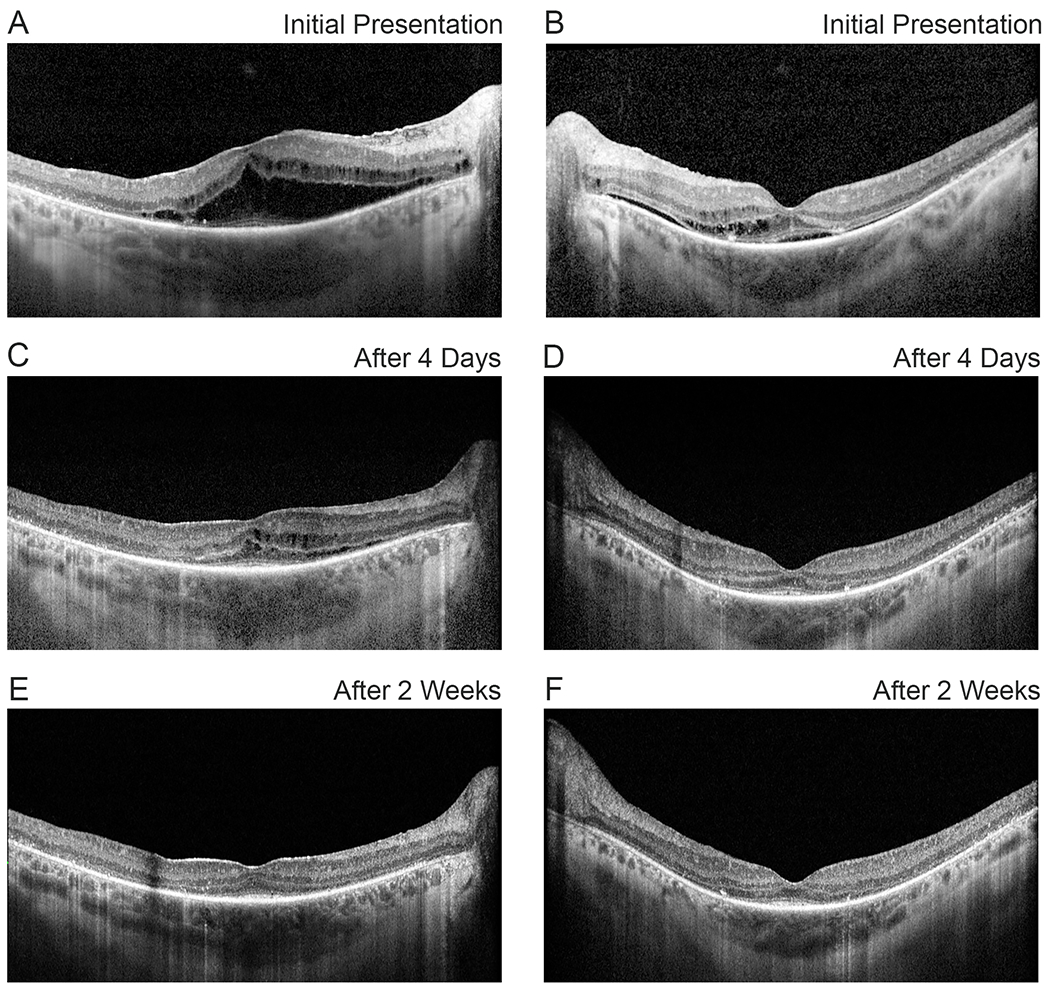

Figure 2.

Optical coherence tomography of the right (A, C, E) and left (B, D, F) eyes showing intra-retinal fluid, right greater than left retinoschisis-like cavities, and left subretinal fluid at initial presentation (A, B), and rapid resolution of the findings 4 days (C, D) and 2 weeks (E, F) after initial presentation.

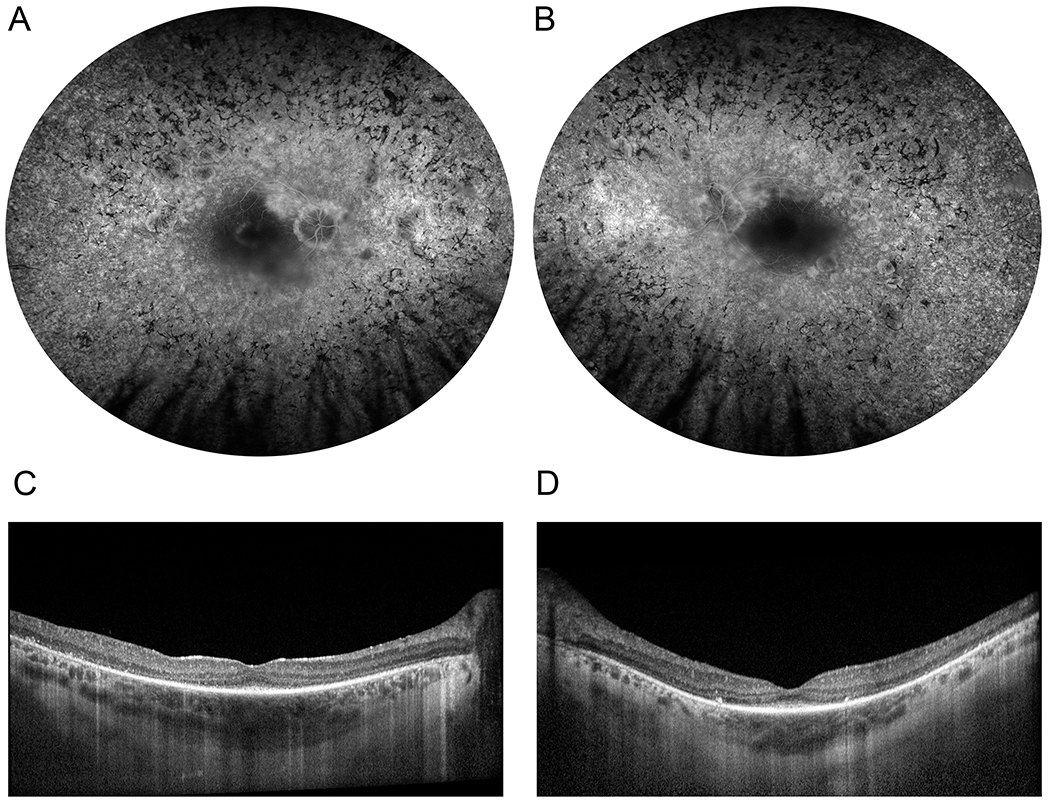

Four days after initial presentation, the patient followed up near his home at normal altitude. BCVA was 20/50 in the right eye and 20/60 in the left, and fundus appearance was unchanged. CME was markedly improved, with CST decreased to 331 microns in the right eye and 233 microns in the left (Figure 1C and 1D). He was instructed to continue acetazolamide and dorzolamide. Two weeks after initial presentation, his visual acuity remained stable at 20/50 in the right eye and 20/60 in the left. CME was completely resolved (Figure 1E and 1F), and acetazolamide was discontinued. Two months after initial presentation, BCVA returned to baseline of 20/40 in both eyes, and topical dorzolamide was discontinued. Six months later, repeat fluorescein angiogram (Figure 3A and 3B) showed resolution of disc leakage, and OCT remained without CME (Figure 3C and 3D).

Figure 3.

Retinal imaging 6 months after initial presentation. Fluorescein angiogram (A, B) showing resolution of disc leakage. There was no recurrence of cystoid macular edema on optical coherence tomography (C, D).

Discussion

We present a case of XLRP in which bilateral CME and disc leakage were detected after exposure to high altitude for several days. XLRP in this patient was caused by a pathogenic variant in RPGR. The RPGR gene is located on Xp21.1, and pathogenic variants in RPGR are the most common cause of XLRP. RPGR encodes two major alternative transcripts, the constitutive RPGREx1-19 isoform widely expressed in all body tissues, and the retina-specific RPGRORF15 isoform (2). RPGRORF15 is comprised of exons 1 to 14 of RPGREx1-19 plus ORF15, an continuation of exon 15 into intron 15 created through skipping of the splice donor site for exon 15. Variants that cause XLRP affect the RPGRORF15 isoform, and many variants are clustered within the ORF15 domain. CME is a common secondary finding affecting central vision in XLRP, and its frequency is similar in different forms of RP. However, the mechanisms of CME in RP are not entirely understood (1).

The patient’s clinical course suggests that CME was precipitated by high altitude, and subsequently rapidly resolved following descent to normal altitude. Topical and oral CAI therapy were also initiated, but typical RP-associated CME requires weeks or months of treatment for improvement (3). Exposure to high altitude is known to induce retinal vascular changes in healthy volunteers. Retinal vessel dilatation is the earliest observable change and occurs above 2,500 meters (4). Above 4,500 meters, there is peripheral capillary leakage and thickening of the ganglion cell and nerve fiber layers (5,6). Above 7,500 meters, the clinical condition known as high-altitude retinopathy manifests as intraretinal and preretinal hemorrhages, cotton-wool spots, and optic disc hyperemia, along with severe systemic sequelae (high-altitude pulmonary edema and cerebral edema) (7). Another possible explanation for the OCT and fluorescein angiogram findings of disc leakage and CME could be hypertensive retinopathy, since high altitude can be associated with mild elevation in blood pressure. The patient followed regularly with a primary care physician and denied any history of hypertension.

The retinal degeneration in XLRP leads to vascular changes that could increase retinal susceptibility to hypoxia at high altitude. Retinal vessels are narrowed, and venules develop increased oxygen saturation, suggesting either decreased perfusion or decreased metabolic demand (8). On OCT angiography, the foveal avascular zone is enlarged with dropout of capillaries from the deep and superficial plexuses (9). Therefore, the normal retinal autoregulatory mechanisms may have decreased ability to compensate for hypoxia and respiratory alkalosis caused by travel to high altitude. Daniele, et al. reported CME in a patient with history of diabetic macular edema precipitated by prolonged flight travel of 42 hours in a commercial aircraft, which is pressurized to approximately 2,500 meters. Our case also demonstrates development of CME in diseased retinal tissue, which may become susceptible at lower altitudes than healthy retinal tissue.

To our knowledge, this report is the first to describe acute onset of altitude-related CME in a patient with RP. Mishra, et al. report a case of CME in India attributed to high altitude in a patient without known retinal disease, but imaging data was only available from 1 year after onset of symptoms (10). The acute presentation and rapid resolution after return to normal altitude suggest a link between exposure to high altitude and development of CME. We hypothesize that the hypoxia and respiratory alkalosis caused by high altitude may have precipitated CME. Acetazolamide causes a mild metabolic acidosis by inhibiting kidney carbonic anhydrase, but its exact role in improving CME in this patient is uncertain. The CME and disc leakage may have resolved with only return to normal altitude, and without treatment. We caution that patients with RP should consult with a retinal specialist prior to traveling to altitudes above 2,500 meters.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This publication was supported by the Foundation Fighting Blindness (CD-CL-0619-0758-UMICH, Diana Davis Spencer Clinical/Research Fellowship Award to Peter Y. Zhao) and by the National Institutes of Health (2K12EY022299-06, K12 Michigan Vision Clinician-Scientist Development Program to Abigail T. Fahim).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have no relevant commercial relationships.

References

- 1.Strong S, Liew G, Michaelides M. Retinitis pigmentosa-associated cystoid macular oedema: pathogenesis and avenues of intervention. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017. January;101(1):31–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Megaw RD, Soares DC, Wright AF. RPGR: Its role in photoreceptor physiology, human disease, and future therapies. Exp Eye Res. 2015. September;138:32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liew G, Moore AT, Webster AR, Michaelides M. Efficacy and Prognostic Factors of Response to Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors in Management of Cystoid Macular Edema in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015. March 3;56(3):1531–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinchmann-Hansen O, Myhre K. Vascular response of retinal arteries and veins to acute hypoxia of 8,000, 10,000, 12,500, and 15,000 feet of simulated altitude. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1990. February;61(2):112–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke AK, Cozzi M, Imray CHE, Wright A, Pagliarini S, Birmingham Medical Research Expeditionary Society. Analysis of Retinal Segmentation Changes at High Altitude With and Without Acetazolamide. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019. 02;60(1):36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willmann G, Fischer MD, Schatz A, Schommer K, Gekeler F. Retinal Vessel Leakage at High Altitude. JAMA. 2013. June 5;309(21):2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiedman M, Tabin GC. High-altitude retinopathy and altitude illness. Ophthalmology. 1999. October;106(10):1924–6; discussion 1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ueda-Consolvo T, Fuchizawa C, Otsuka M, Nakagawa T, Hayashi A. Analysis of retinal vessels in eyes with retinitis pigmentosa by retinal oximeter. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 2015. September;93(6):e446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Battaglia Parodi M, Cicinelli MV, Rabiolo A, Pierro L, Gagliardi M, Bolognesi G, et al. Vessel density analysis in patients with retinitis pigmentosa by means of optical coherence tomography angiography. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(4):428–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishra A, Luthra S, Baranwal VK, Shyamsunder K. Bilateral cystoid macular oedema due to high altitude exposure: An unusual clinical presentation. Med J Armed Forces India. 2013. October;69(4):394–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]