Key Points

Question

Is there a difference in the association of fish consumption with risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or of mortality between individuals with and individuals without vascular disease?

Findings

In this analysis of 4 international cohort studies of 191 558 people from 58 countries on 6 continents, a lower risk of major CVD and total mortality was associated with higher fish intake of at least 175 g (2 servings) weekly among high-risk individuals or patients with vascular disease, but not in general populations without vascular disease; a similar pattern of results was observed for sudden cardiac death. Oily fish but not other types of fish were associated with greater benefits.

Meaning

Study findings suggest that fish intake of at least 175 g (2 servings) weekly is associated with lower risk of major CVD and mortality among patients with prior CVD, but not in the general population.

Abstract

Importance

Cohort studies report inconsistent associations between fish consumption, a major source of long-chain ω-3 fatty acids, and risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality. Whether the associations vary between those with and those without vascular disease is unknown.

Objective

To examine whether the associations of fish consumption with risk of CVD or of mortality differ between individuals with and individuals without vascular disease.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This pooled analysis of individual participant data involved 191 558 individuals from 4 cohort studies—147 645 individuals (139 827 without CVD and 7818 with CVD) from 21 countries in the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study and 43 413 patients with vascular disease in 3 prospective studies from 40 countries. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated by multilevel Cox regression separately within each study and then pooled using random-effects meta-analysis. This analysis was conducted from January to June 2020.

Exposures

Fish consumption was recorded using validated food frequency questionnaires. In 1 of the cohorts with vascular disease, a separate qualitative food frequency questionnaire was used to assess intake of individual types of fish.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Mortality and major CVD events (including myocardial infarction, stroke, congestive heart failure, or sudden death).

Results

Overall, 191 558 participants with a mean (SD) age of 54.1 (8.0) years (91 666 [47.9%] male) were included in the present analysis. During 9.1 years of follow-up in PURE, compared with little or no fish intake (≤50 g/mo), an intake of 350 g/wk or more was not associated with risk of major CVD (HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.86-1.04) or total mortality (HR, 0.96; 0.88-1.05). By contrast, in the 3 cohorts of patients with vascular disease, the HR for risk of major CVD (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.96) and total mortality (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.74-0.91) was lowest with intakes of at least 175 g/wk (or approximately 2 servings/wk) compared with 50 g/mo or lower, with no further apparent decrease in HR with consumption of 350 g/wk or higher. Fish with higher amounts of ω-3 fatty acids were strongly associated with a lower risk of CVD (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.92-0.97 per 5-g increment of intake), whereas other fish were neutral (collected in 1 cohort of patients with vascular disease). The association between fish intake and each outcome varied by CVD status, with a lower risk found among patients with vascular disease but not in general populations (for major CVD, I2 = 82.6 [P = .02]; for death, I2 = 90.8 [P = .001]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Findings of this pooled analysis of 4 cohort studies indicated that a minimal fish intake of 175 g (approximately 2 servings) weekly is associated with lower risk of major CVD and mortality among patients with prior CVD but not in general populations. The consumption of fish (especially oily fish) should be evaluated in randomized trials of clinical outcomes among people with vascular disease.

This analysis pools data from 4 large cohort studies conducted in 58 countries to assess whether associations of fish consumption with risk of cardiovascular disease or mortality differ between individuals with and individuals without vascular disease.

Introduction

Dietary guidelines recommend at least 2 servings of fish per week for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD).1,2 Fish is a major source of the long-chain ω-3 fatty acids docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid, which have been suggested to have beneficial effects on cardiovascular health.3,4,5 In interventional studies, fish and ω-3 consumption have been shown to improve some cardiovascular risk markers, including triglycerides and blood pressure, especially in people with triglycerides of 500 mg/dL or greater (to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113).6,7 Two recent meta-analyses of randomized trials in high-risk individuals showed that ω-3 supplementation (typically approximately 1 g/d) was not associated with risk of cardiovascular events, coronary heart deaths, coronary heart disease events, stroke, heart irregularities, or all-cause mortality.8,9 By contrast, another recent meta-analysis10 that included 3 new trials11,12,13 showed that ω-3 supplementation was associated with significant benefit against risk of CVD outcomes (summary relative risk of 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86-0.98),10 even after excluding a recent trial of patients with elevated triglyceride levels that used a much higher dose of fish oil (4 g daily).13 Observational cohorts of participants without diagnosed vascular disease have found modest protective associations of moderate fish consumption (approximately ≥2 servings/wk) with fatal coronary heart disease (ie, summary relative risks in multiple meta-analyses ranging from 2% to 15% lower risk) and, usually less strongly, with total CVD.14 To date, most cohort studies evaluating fish consumption and CVD events have been conducted in Europe, North America, Japan, and China, with little information from other world regions, where varying amounts and types of fish are consumed. Furthermore, whether the associations of fish consumption with CVD events vary between those with and those without vascular disease is unclear.

Because increasing fish intake may improve blood lipid levels, especially among high-risk individuals,6,7 we hypothesized that there would be differences in the association between fish intake and major CVD outcomes and mortality among individuals with vascular disease compared with those without vascular disease. In the present pooled analysis, we studied 191 558 people (51 731 with vascular disease and 139 827 generally healthy individuals) from 58 countries who had been included as participants in 4 large prospective studies.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Details of the studies’ designs and population characteristics have been published before and are described in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

In brief, the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study15,16,17,18,19 is an ongoing large-scale epidemiologic cohort study that has enrolled 166 762 individuals, 35 to 70 years of age, in 21 low-, middle-, and high-income countries on 5 continents. For the present analysis, we included 147 645 participants (including 7818 [5.3%] with a history of CVD) with complete information on their diet (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). We included all outcome events known until July 31, 2019.

The Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination With Ramipril Global End Point Trial (ONTARGET) is a randomized clinical trial of antihypertension medication (ramipril, telmisartan, and their combination) for 25 620 patients aged 55 years or older with vascular disease or diabetes.20 The Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) was a randomized clinical trial of telmisartan vs placebo for 5926 participants.21 For the present analysis, we included 31 491 participants from ONTARGET and TRANSCEND with dietary assessments in 40 countries on 6 continents.

The Outcome Reduction With Initial Glargine Intervention (ORIGIN) trial was a randomized clinical trial of insulin glargine therapy or standard care and ω-3 fatty acid or placebo supplementation (2 × 2 factorial design) that included 12 537 people (mean [SD] age, 63.5 [7.8] years) with cardiovascular risk factors plus impaired fasting glucose or diabetes.22,23 For the present analysis, we included 12 422 participants from ORIGIN with dietary assessments in 40 countries on 5 continents. We collected information on the type of fish consumed in ORIGIN but not in other studies. All studies were coordinated by the Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton Health Sciences and McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Procedures

The information about the study variables was collected with similar approaches and data collection forms in each of the studies. Information about demographic factors, lifestyle, health history, and medication use was recorded. Physical assessments included weight, height, waist and hip circumferences, and blood pressure.

In PURE, participants’ habitual food intake was recorded using country-specific validated food frequency questionnaires (FFQs; eAppendix in the Supplement).24,25 In ONTARGET and TRANSCEND, dietary information was obtained using a 19-item qualitative FFQ.20,21 In ORIGIN, a 25-item qualitative FFQ was used to obtain information on individual foods or food groups, except for fish.22,23 A separate 28-item qualitative FFQ was used to assess fish intake (24 types of fish and 4 types of shellfish) (eAppendix in the Supplement).

Standardized case report forms were used to capture clinical data and to record major CVD events and death during follow-up in each study. Major cardiovascular events and deaths during follow-up were recorded and adjudicated centrally in each country using standard definitions. Events were classified according to the definitions used in each study, but these definitions were broadly similar.

Statistical Analysis

Median fish intake was calculated overall and according to geographic region and country, with adjustment for age and sex. For all 3 cohorts, participants were grouped according to fish consumption into lower than 50 g/mo, 50 g/mo to lower than 175 g/wk, 175 to lower than 350 g/wk, and 350 g/wk or higher (ie, equivalent to fixed increments of about 25 g/d); the lowest intake group was used as the reference. Analysis of covariance was performed to calculate mean blood lipid levels and blood pressure levels among fish intake groups, adjusting for covariates.

We used a 2-stage individual participant data meta-analysis.26 First, we assessed the associations between fish intake and events in each cohort separately. For the PURE cohort, estimates were obtained overall and separately for 2 subcohorts of people with or without CVD (the other 3 cohort studies were composed entirely of patients with vascular disease). Second, the cohort-specific hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs were pooled (separately by cohort of people with or without CVD) in a random-effects meta-analysis.27 The proportionality assumption was tested using the global goodness-of-fit test with Schoenfeld residuals in each cohort. No evidence of a violation was found. Tests of heterogeneity were conducted using the I2 statistic.

In the PURE study, Cox frailty models with random effects (to account for clustering within study centers) were used to assess the association between fish intake and the outcomes.28 In a minimally adjusted model, we adjusted for age, sex, and study center (as a random effect). The primary model adjusted for age, sex, study center (as a random effect), body mass index, educational level, wealth index, smoking status, urban or rural location, physical activity, history of diabetes, use of statin or antihypertension medication, and fruit, vegetables, red meat, poultry, dairy, and total energy intake, as in articles previously published by members of our group.24,25,29 To test for linear trends, we used the median fish intake value in each of the categories of fish intake and included the variable as a quantitative risk factor. In ONTARGET and TRANSCEND, because the entry criteria and study conduct were similar for the 2 trials, we pooled the data from both studies in our analysis. As in the PURE analyses, in ONTARGET/TRANSCEND and in ORIGIN, we used Cox frailty models with similar adjustment models, but additionally adjusted for treatment allocation.

In sensitivity analyses for each study, estimates were assessed in the primary models after removing potential associated factors (body mass index, waist to hip ratio, diabetes, and hypertension). In addition, we assessed whether the association of fish intake varied by geographic region using tests of interaction. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. The present analysis was conducted from January to June 2020.

Results

Participant characteristics from each study are provided in Table 1.15,19 Overall, 191 558 participants with a mean (SD) age of 54.1 (8.0) years (91 666 [47.9%] males) were included in the present analysis. The median duration of follow-up was 7.5 years (interquartile range [IQR], 4.9-9.4 years), with follow-up completed for 96% of the participants. The median follow-up in PURE was 9.1 years (IQR, 6.8-10.4 years), 4.5 years (IQR, 4.4-5.0 years) in ONTARGET and TRANSCEND, and 6.2 years (IQR, 5.8-6.7 years) in ORIGIN.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Participants by Category of Fish Intake and by Study.

| Characteristic | Category of fish intake | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 g/mo | 50 g/mo to <175 g/wk | 175 to <350 g/wk | ≥350 g/wk | |

| PURE trial (n = 147 541) | ||||

| No. of participants | 37 514 | 61 950 | 21 661 | 25 225 |

| Intake, median (IQR), g/wk | 0.07 (0 to 7.0) | 67.9 (32.9 to 109.9) | 231.0 (197.4 to 273.7) | 593.6 (450.1 to 1050) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 50.2 (10.3) | 50.5 (9.9) | 51 (9.9) | 51.3 (9.9) |

| Male, No. (%) | 15 020 (40.0) | 26 449 (42.7) | 9525 (44.0) | 10 472 (41.5) |

| Location, No. (%) | ||||

| Urban | 18 226 (48.6) | 31 516 (50.9) | 14 346 (66.2) | 13 804 (54.7) |

| Rural | 19 288 (51.4) | 30 434 (49.1) | 7315 (33.8) | 11 421 (45.3) |

| Geographical region, No. (%) | ||||

| South Asia | 13 460 (35.9) | 10 000 (16.1) | 1769 (8.2) | 5017 (19.9) |

| China | 10 610 (28.3) | 22 884 (36.9) | 6564 (30.3) | 5378 (21.3) |

| Southeast Asia | 238 (0.6) | 1246 (2) | 2500 (11.5) | 7378 (29.2) |

| Africa | 1462 (3.9) | 2700 (4.4) | 840 (3.9) | 735 (2.9) |

| North America or Europe | 1468 (3.9) | 10 391 (16.8) | 4947 (22.8) | 2870 (11.4) |

| Middle East | 2596 (6.9) | 4338 (7) | 1607 (7.4) | 1702 (6.7) |

| South America | 7680 (20.5) | 10 391 (16.8) | 3434 (15.9) | 2145 (8.5) |

| Educational level, No. (%) | ||||

| None, primary, or unknown | 20 962 (56.1) | 26 492 (42.9) | 6663 (30.8) | 8368 (33.2) |

| Secondary, high, or higher secondary | 11 496 (30.8) | 23 407 (37.9) | 8988 (41.6) | 11 357 (45.1) |

| Trade, college, or university | 4912 (13.1) | 11 890 (19.2) | 5979 (27.6) | 5461 (21.7) |

| Wealth index, median (IQR)a | –0.26 (–1.14 to 0.42) | 0.14 (–0.70 to 0.82) | 0.48 (–0.15 to 1.07) | 0.21 (–0.60 to 0.91) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 25.2 (5.4) | 25.9 (5.2) | 26.5 (5.1) | 26 (5) |

| Waist to hip ratio, mean (SD) | 0.873 (0.09) | 0.872 (0.084) | 0.877 (0.084) | 0.876 (0.083) |

| Blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | ||||

| Systolic | 130.2 (22.6) | 131.3 (22.6) | 131.5 (21.8) | 132.7 (21.8) |

| Diastolic | 81.7 (13.7) | 82.2 (17.3) | 81.9 (14) | 81.6 (13.5) |

| Smoking, No. (%) | ||||

| Former | 3247 (8.7) | 7786 (12.7) | 3402 (15.8) | 2883 (11.5) |

| Current | 7605 (20.5) | 13 952 (22.7) | 4252 (19.8) | 4306 (17.2) |

| Never | 26 309 (70.8) | 39 711 (64.6) | 13 813 (64.3) | 17 847 (71.3) |

| Alcohol, No. (%) | ||||

| Former | 1625 (4.4) | 2974 (4.9) | 947 (4.5) | 908 (3.6) |

| Current | 6553 (17.7) | 17 378 (28.4) | 7577 (36.3) | 5875 (23.6) |

| Never | 28 808 (77.9) | 40 853 (66.7) | 12 356 (59.2) | 18 163 (72.8) |

| Physical activity, No. (%) | ||||

| Low | 7122 (20.9) | 9329 (16) | 3617 (17.5) | 4760 (20.4) |

| Moderate | 12 514 (36.8) | 22 439 (38.4) | 8061 (39) | 8656 (37.1) |

| High | 14 380 (42.3) | 26 693 (45.7) | 9010 (43.6) | 9886 (42.4) |

| History of diabetes, No. (%) | 2775 (7.4) | 4392 (7.1) | 1875 (8.7) | 2854 (11.3) |

| History of hypertension, No. (%) | 7430 (19.8) | 12 860 (20.8) | 4631 (21.4) | 5865 (23.3) |

| Energy, mean (SD) | ||||

| Intake, kcal | 1970 (778) | 2026 (733) | 2197 (784) | 2624 (887) |

| From carbohydrate % | 63.6 (12.3) | 62.7 (11.5) | 58.3 (10.5) | 55.8 (9.2) |

| From protein % | 14 (3.6) | 15 (3.2) | 16.4 (3.1) | 17 (3.8) |

| From total fat % | 22.4 (10.2) | 22.3 (9.3) | 25.4 (8.4) | 27.3 (7.5) |

| Alternative Healthy Index score, mean (SD) | 33.0 (7.7) | 34.5 (7.8) | 35.3 (8.2) | 36.6 (9.0) |

| Dairy, mean (SD), servings/d | 1.1 (1.4) | 1.5 (2.0) | 1.8 (2.3) | 1.4 (1.9) |

| Fruits, mean (SD), servings/d | 1.3 (1.8) | 1.7 (2.1) | 2 (2.2) | 2.2 (2.8) |

| Vegetables, mean (SD), servings/d | 2 (2.1) | 2.7 (2.8) | 3.5 (3.9) | 3.3 (3.8) |

| Meats, mean (SD), servings/d | 1.9 (2.8) | 2.6 (3.5) | 3.6 (5.7) | 4.2 (5.8) |

| Red and processed meat, mean (SD), servings/d | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.9) | 1 (1.0) | 0.8 (0.9) |

| White meat, mean (SD), servings/d | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.6 (0.4) | 1.6 (1.3) |

| Breads and cereals, mean (SD), servings/d | 5.7 (3.2) | 5 (2.8) | 5.2 (3.2) | 6.2 (3.8) |

| ONTARGET and TRANSCEND (n = 31 491) | ||||

| No. of participants | 2801 | 16 377 | 7335 | 4978 |

| Intake, median (IQR), g/wk | 2.8 (0 to 9.2) | 119.7 (55.3 to 119.7) | 240.1 (200.2 to 249.9) | 450.1 (359.8 to 720.3) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 66.7 (7.5) | 66.5 (7.2) | 66.6 (7.3) | 66.3 (7.0) |

| Male, No. (%) | 1779 (63.5) | 11 667 (71.2) | 5216 (71.1) | 3464 (69.6) |

| Geographic region, No. (%) | ||||

| North America and Europe | 1547 (55.2) | 11 267 (68.8) | 4895 (66.7) | 2701 (54.3) |

| South America or Mexico | 855 (30.5) | 1365 (8.3) | 645 (8.8) | 443 (8.9) |

| Middle East | 24 (0.9) | 230 (1.4) | 97 (1.3) | 240 (4.8) |

| China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, or South Korea | 183 (6.5) | 1516 (9.3) | 536 (7.3) | 748 (15) |

| Southeast Asia | 19 (0.7) | 350 (2.1) | 378 (5.2) | 496 (10) |

| Africa | 48 (1.7) | 468 (2.9) | 224 (3.1) | 91 (1.8) |

| Australia or New Zealand | 125 (4.5) | 1181 (7.2) | 560 (7.6) | 259 (5.2) |

| Educational level, No. (%) | ||||

| None primary or unknown | 805 (28.7) | 5063 (30.9) | 2185 (29.8) | 1241 (24.9) |

| Secondary, high, or higher secondary | 1239 (44.2) | 5306 (32.4) | 2274 (31) | 1826 (36.7) |

| Trade, college, or university | 757 (27) | 6007 (36.7) | 2876 (39.2) | 1910 (38.4) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.1 (4.6) | 28.2 (4.5) | 28.1 (4.5) | 27.6 (4.6) |

| Waist to hip ratio, mean (SD) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) |

| Blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | ||||

| Systolic | 140.8 (17.2) | 141.7 (17.2) | 141.8 (17.2) | 142 (17.7) |

| Diastolic | 82 (10.3) | 82.1 (10.4) | 82 (10.2) | 81.8 (10.5) |

| Smoking, No. (%) | ||||

| Former | 1378 (49.2) | 8333 (50.9) | 3681 (50.2) | 2422 (48.7) |

| Current | 381 (13.6) | 2106 (12.9) | 808 (11.0) | 504 (10.1) |

| Never | 1039 (37.1) | 5921 (36.2) | 2839 (38.7) | 2047 (41.2) |

| Physical activity, No. (%) | ||||

| Low | 1256 (44.8) | 5817 (35.5) | 2332 (31.8) | 1512 (30.4) |

| Moderate | 573 (20.5) | 3828 (23.4) | 1732 (23.6) | 1054 (21.2) |

| High | 972 (34.7) | 6730 (41.1) | 3271 (44.6) | 2412 (48.5) |

| History of diabetes, No. (%) | 1028 (36.7) | 6103 (37.3) | 2675 (36.5) | 1902 (38.2) |

| History of hypertension, No. (%) | 2091 (74.7) | 11 542 (70.5) | 5076 (69.2) | 3392 (68.1) |

| Alternative Healthy Index score, mean (SD) | 21.8 (7.3) | 24.1 (7.1) | 26.5 (7.6) | 29.0 (7.9) |

| Fruits, mean (SD), servings/d | 1.1 (1.4) | 1.2 (1.3) | 1.5 (1.3) | 1.6 (2) |

| Leafy green vegetables, mean (SD), servings/d | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.9 (1.0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Dairy, mean (SD), servings/d | 0.9 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) |

| Meat or poultry, mean (SD), servings/d | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.8) | 0.8 (1) |

| ORIGIN trial (n = 12 422) | ||||

| No. of participants | 3572 | 5049 | 1995 | 1806 |

| Intake, median (IQR), g/wk | 2.2 (0 to 8.8) | 64.5 (28.0 to 119.7) | 248.5 (211.4 to 319.2) | 567.7 (445.2 to 874.3) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 63.6 (7.9) | 63.5 (7.8) | 63.7 (7.7) | 63.5 (7.8) |

| Male, No. (%) | 2136 (59.8) | 3249 (64.4) | 1372 (68.7) | 1317 (72.9) |

| Geographic region, No. (%) | ||||

| North America and Europe | 921 (25.8) | 2800 (55.5) | 1416 (70.9) | 1328 (73.5) |

| South America or Mexico | 1944 (54.4) | 1414 (28.0) | 301 (15.1) | 174 (9.6) |

| Middle East | 53 (1.5) | 90 (1.8) | 57 (2.9) | 52 (2.9) |

| South Asia | 289 (8.1) | 80 (1.6) | 8 (0.4) | 10 (0.6) |

| China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, or South Korea | 174 (4.9) | 219 (4.3) | 82 (4.1) | 109 (6.0) |

| Southeast Asia | 60 (1.7) | 40 (0.8) | 11 (0.6) | 22 (1.2) |

| Africa | 118 (3.3) | 347 (6.9) | 78 (3.9) | 52 (2.9) |

| Australia or New Zealand | 14 (0.4) | 59 (1.2) | 43 (2.2) | 60 (3.3) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 29.6 (5.4) | 29.9 (5.2) | 29.9 (5.2) | 29.8 (5.0) |

| Blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | ||||

| Systolic | 147.6 (22.7) | 145.9 (21.7) | 144.6 (20.7) | 143.4 (20.8) |

| Diastolic | 84.8 (12.4) | 84.4 (12.0) | 83.3 (11.6) | 83.0 (11.9) |

| Smoking, No. (%) | ||||

| Former | 1471 (41.2) | 2324 (46.0) | 1015 (50.9) | 927 (51.3) |

| Current smoker | 408 (11.4) | 635 (12.6) | 253 (12.7) | 243 (13.5) |

| Never | 1694 (47.4) | 2090 (41.4) | 728 (36.5) | 636 (35.2) |

| Low physical activity, No. (%) | 1127 (31.5) | 1050 (20.8) | 275 (13.8) | 260 (14.4) |

| History of diabetes, No. (%) | 3261 (91.3) | 4423 (87.6) | 1706 (85.5) | 1596 (88.3) |

| History of hypertension, No. (%) | 2856 (79.9) | 4054 (80.3) | 1561 (78.2) | 1400 (77.5) |

| Fruits, mean (SD), servings/d | 86.5 (76.6) | 95.2 (78.9) | 103.6 (81.8) | 118.3 (91.9) |

| Vegetables, mean (SD), servings/d | 133.5 (103.6) | 129.9 (99.7) | 146.1 (114.0) | 176.4 (142.8) |

| Dairy, mean (SD), servings/d | 94.4 (108.3) | 112.8 (111.5) | 109.8 (103.8) | 122.9 (112.2) |

| Meat or poultry, mean (SD), servings/d | 77.8 (70.8) | 73.1 (63.7) | 73.5 (60.5) | 106.3 (129.1) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); IQR, interquartile range; ONTARGET, Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination With Ramipril Global End Point Trial; ORIGIN, Outcome Reduction With Initial Glargine Intervention; PURE, Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology; TRANSCEND, Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease.

Overall, there were 8949 deaths (6.4%) among individuals without prior CVD and 6763 (13.1%) among individuals with prior CVD. There were 6825 (4.9%) major CVD events among individuals without prior CVD and 8565 (16.6%) among individuals with prior CVD.

Median fish intake ranged from 4.2 g/wk in South Asia to 468.3 g/wk in Southeast Asia (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). By country, fish intake was lowest in Argentina (0.7 g/wk) and India (1.4 g/wk) and highest in Malaysia (452.2 g/wk), Philippines (522.9 g/wk), and United Arab Emirates (1350 g/wk).

Associations of Fish Intake With CVD and Mortality

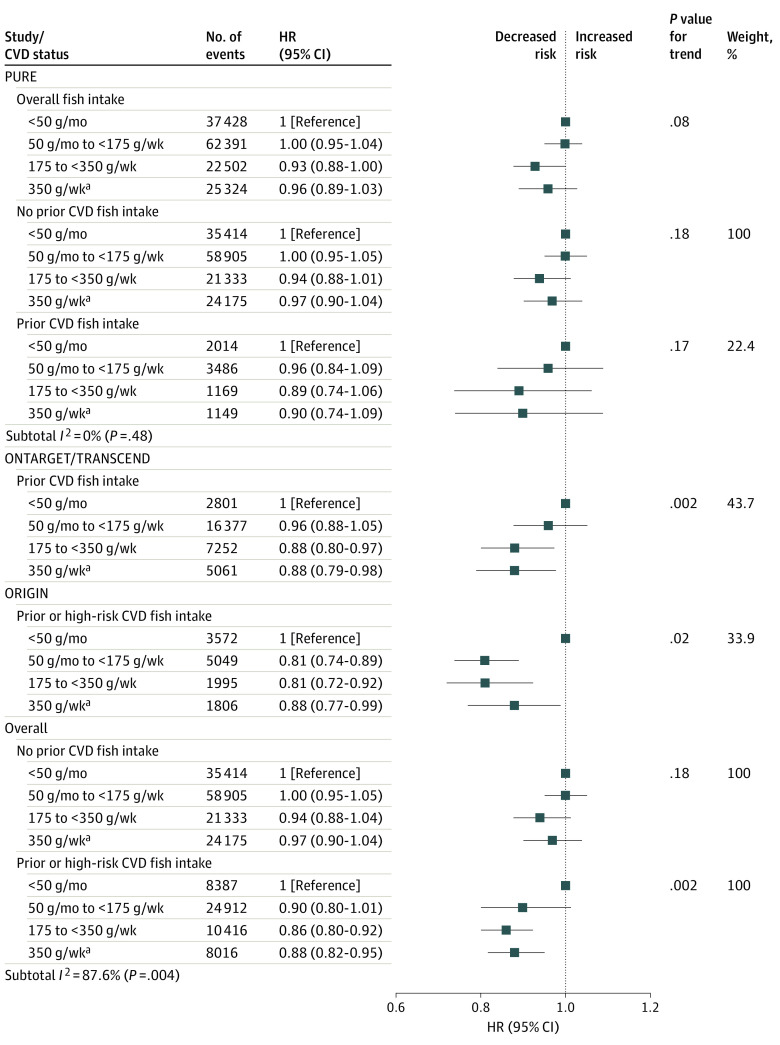

In PURE, no significant association between fish intake and any health outcome was found, after adjustment for known confounders. Compared with little or no fish intake (≤50 g/mo; reference category), an intake of 350 g/wk or more (approximately 4 servings) was not significantly associated with risk of major CVD (HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.86-1.04), CVD mortality (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.80-1.10), non-CVD mortality (HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.90-1.12), or total mortality (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.88-1.05) (Table 2; Figure 1). The association between fish intake and outcome events did not differ significantly by history of CVD status within PURE (Figure 1; eFigure 5 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Association Between Fish Intake and Clinical Events in Each Studya.

| Event | Category of fish intake, HR (95% CI) | P value for trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 g/mo | 50 g/mo to <175 g/wk | 175 to <350 g/wk | ≥350 g/wk | ||

| PURE trial (n = 147 541) | |||||

| Intake, median (IQR), g/wk | 0.1 (0.0-7.0) | 67.9 (32.9-109.9) | 231.0 (197.4-273.7) | 593.6 (450.1-1050.0) | |

| Composite of death or major CVD | |||||

| No. of participants | 37 428 | 62 391 | 22 502 | 25 324 | |

| No. (%) of events (n = 15 019) | 4338 (11.6) | 6331 (10.2) | 1799 (8.0) | 2551 (10.1) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) | 0.87 (0.81-0.92) | 0.90 (0.84-0.96) | <.001 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.95-1.04) | 0.93 (0.88-1.00) | 0.96 (0.89-1.03) | .08 |

| No history of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.95-1.05) | 0.94 (0.88-1.01) | 0.97 (0.90-1.04) | .18 |

| History of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 0.96 (0.84-1.09) | 0.89 (0.74-1.06) | 0.90 (0.74-1.09) | .17 |

| Total mortality | |||||

| No. of participants | 37 428 | 62 391 | 22 502 | 25 324 | |

| No. (%) of deaths (n = 10 076) | 3131 (8.4) | 4069 (6.5) | 1140 (5.1) | 1736 (6.9) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.95-1.05) | 0.89 (0.83-0.96) | 0.91 (0.84-0.99) | .005 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 1.02 (0.96-1.08) | 0.98 (0.90-1.07) | 0.96 (0.88-1.05) | .35 |

| No history of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 1.02 (0.96-1.08) | 0.98 (0.90-1.07) | 0.97 (0.88-1.06) | .48 |

| History of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 0.94 (0.79-1.11) | 0.92 (0.73-1.16) | 0.91 (0.71-1.16) | .36 |

| Major CVD events | |||||

| No. of participants | 37 428 | 62 391 | 22 502 | 25 324 | |

| No. (%) of events (n = 8201) | 2215 (5.9) | 3524 (5.6) | 1001 (4.4) | 1461 (5.8) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.98 (0.92-1.04) | 0.85 (0.78-0.92) | 0.90 (0.83-0.99) | .001 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.94-1.07) | 0.89 (0.82-0.97) | 0.95 (0.86-1.04) | .06 |

| No history of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.94-1.08) | 0.91 (0.83-1.00) | 0.97 (0.88-1.08) | .24 |

| History of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 0.97 (0.83-1.13) | 0.83 (0.67-1.03) | 0.86 (0.69-1.08) | .08 |

| Myocardial infarction | |||||

| No. of participants | 37 428 | 62 391 | 22 502 | 25 324 | |

| No. (%) of events (n = 3806) | 1146 (3.1) | 1486 (2.4) | 456 (2.0) | 718 (2.8) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.97 (0.89-1.06) | 0.90 (0.80-1.02) | 0.88 (0.77-1.00) | .03 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 1.01 (0.92-1.11) | 0.97 (0.85-1.10) | 0.90 (0.78-1.04) | .15 |

| No history of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 1.01 (0.91-1.12) | 0.97 (0.84-1.12) | 0.96 (0.82-1.11) | .46 |

| History of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 0.95 (0.76-1.18) | 0.96 (0.71-1.29) | 0.71 (0.51-0.99) | .07 |

| Stroke | |||||

| No. of participants | 37 428 | 62 391 | 22 502 | 25 324 | |

| No. (%) of events (n = 3925) | 986 (2.6) | 1827 (2.9) | 478 (2.1) | 634 (2.5) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.95 (0.87-1.04) | 0.80 (0.71-0.90) | 0.91 (0.80-1.03) | .01 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.97 (0.88-1.06) | 0.81 (0.72-0.92) | 0.95 (0.83-1.08) | .09 |

| No history of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 0.96 (0.87-1.06) | 0.84 (0.73-0.96) | 0.97 (0.84-1.11) | .22 |

| History of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.80-1.25) | 0.75 (0.55-1.03) | 0.91 (0.66-1.27) | .22 |

| Sudden cardiac death | |||||

| No. of participants | 37 428 | 62 391 | 22 502 | 25 324 | |

| No. (%) of events (n = 371) | 109 (0.3) | 189 (0.3) | 30 (0.1) | 43 (0.2) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.84 (0.64-1.09) | 0.91 (0.57-1.46) | 1.03 (0.64-1.65) | .79 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.78 (0.58-1.05) | 0.83 (0.49-1.40) | 0.99 (0.59-1.68) | .69 |

| No history of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 0.78 (0.56-1.08) | 0.75 (0.41-1.36) | 1.10 (0.64-1.89) | .91 |

| History of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 0.31 (0.11-0.87) | 0.80 (0.18-3.68) | 0.67 (0.02-19.2) | .50 |

| CVD death | |||||

| No. of participants | 37 428 | 62 391 | 22 502 | 25 324 | |

| No. (%) of events (n = 3102) | 993 (2.6) | 1206 (1.9) | 317 (1.4) | 586 (2.3) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 1.02 (0.93-1.12) | 0.87 (0.76-1.01) | 0.90 (0.78-1.04) | .07 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 1.06 (0.96-1.18) | 0.94 (0.81-1.10) | 0.94 (0.80-1.10) | .33 |

| No history of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 1.07 (0.96-1.20) | 0.97 (0.82-1.15) | 0.99 (0.84-1.20) | .84 |

| History of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 0.95 (0.75-1.19) | 0.81 (0.57-1.13) | 0.72 (0.51-1.03) | .047 |

| Non-CVD death | |||||

| No. of participants | 37 428 | 62 391 | 22 502 | 25 324 | |

| No. (%) of events (n = 5904) | 1820 (4.9) | 2414 (3.9) | 707 (3.1) | 963 (3.8) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.98 (0.92-1.05) | 0.91 (0.82-1.00) | 0.94 (0.85-1.04) | .11 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.93-1.07) | 1.00 (0.90-1.11) | 1.00 (0.90-1.12) | .99 |

| No history of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.92-1.07) | 0.98 (0.88-1.10) | 0.99 (0.88-1.10) | .76 |

| History of CVD | 1 [Reference] | 0.96 (0.74-1.23) | 1.05 (0.75-1.49) | 1.09 (0.75-1.58) | .17 |

| ONTARGET and TRANSCEND (n = 31 491)b,c | |||||

| Intake, median (IQR), g/d | 2.8 (0 to 9.2) | 119.7 (55.3-119.7) | 240.1 (200.2-249.9) | 450.1 (359.8-720.3) | |

| Composite of death or major CVD | |||||

| No. of participants | 2801 | 16 377 | 7252 | 5061 | |

| No. (%) of events | 642 (22.9) | 3434 (21.0) | 1395 (19.2) | 979 (19.3) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.94 (0.86-1.03) | 0.85 (0.77-0.93) | 0.84 (0.75-0.93) | <.001 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.96 (0.88-1.05) | 0.88 (0.80-0.97) | 0.88 (0.79-0.98) | .002 |

| Total mortality | |||||

| No. of participants | 2801 | 16 377 | 7252 | 5061 | |

| No. (%) of events | 404 (14.42) | 2005 (12.24) | 825 (11.38) | 537 (10.61) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.90 (0.80-1.00) | 0.82 (0.72-0.92) | 0.75 (0.66-0.86) | <.001 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.92 (0.82-1.02) | 0.86 (0.76-0.98) | 0.81 (0.70-0.92) | <.001 |

| Major CVD events | |||||

| No. of participants | 2801 | 16 377 | 7252 | 5061 | |

| No. (%) of events | 504 (18.0) | 2752 (16.8) | 1116 (15.4) | 810 (16.0) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.96 (0.87-1.06) | 0.86 (0.77-0.96) | 0.87 (0.78-0.98) | .001 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.97 (0.88-1.08) | 0.89 (0.80-1.00) | 0.91 (0.81-1.03) | .02 |

| Myocardial infarction | |||||

| No. of participants | 2801 | 16 377 | 7252 | 5061 | |

| No. (%) of events | 151 (5.4) | 791 (4.8) | 360 (5.0) | 250 (4.9) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.86 (0.72-1.02) | 0.85 (0.70-1.03) | 0.84 (0.68-1.04) | .22 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.86 (0.72-1.03) | 0.86 (0.71-1.05) | 0.86 (0.69-1.06) | .34 |

| Stroke | |||||

| No. of participants | 2801 | 16 377 | 7252 | 5061 | |

| No. (%) of events | 118 (4.2) | 740 (4.5) | 285 (3.9) | 252 (5.0) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 1.07 (0.87-1.30) | 0.93 (0.75-1.16) | 1.15 (0.91-1.44) | .64 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 1.11 (0.91-1.36) | 0.99 (0.80-1.24) | 1.25 (1.00-1.58) | .20 |

| Sudden cardiac death | |||||

| No. of participants | 2801 | 16 377 | 7252 | 5061 | |

| No. (%) of events | 43 (1.5) | 221 (1.4) | 101 (1.4) | 66 (1.3) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 1.04 (0.74-1.47) | 1.03 (0.71-1.48) | 0.93 (0.62-1.39) | .30 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 1.04 (0.74-1.46) | 1.05 (0.72-1.52) | 0.94 (0.63-1.42) | .72 |

| CVD death | |||||

| No. of participants | 2801 | 16 377 | 7252 | 5061 | |

| No. (%) of events | 243 (8.7) | 1199 (7.3) | 497 (6.8) | 326 (6.4) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.91 (0.79-1.04) | 0.83 (0.71-0.98) | 0.76 (0.64-0.91) | <.001 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.92 (0.80-1.06) | 0.87 (0.74-1.02) | 0.80 (0.67-0.96) | .01 |

| Non-CVD death | |||||

| No. of participants | 2801 | 16 377 | 7252 | 5061 | |

| No. (%) of events | 161 (5.8) | 806 (4.9) | 328 (4.5) | 211 (4.2) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.87 (0.73-1.03) | 0.78 (0.64-0.94) | 0.73 (0.59-0.90) | .001 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.89 (0.75-1.06) | 0.83 (0.68-1.01) | 0.79 (0.64-0.98) | .02 |

| ORIGIN trial (n = 12 422)b,c | |||||

| Intake, median (IQR), g/d | 2.2 (0 to 8.8) | 64.5 (28.0-119.7) | 248.5 (211.4-319.2) | 567.7 (445.2-874.3) | |

| Composite of death or major CVD | |||||

| No. of participants | 3572 | 5049 | 1995 | 1806 | |

| No. (%) of events | 866 (24.2) | 1022 (20.2) | 395 (19.8) | 391 (21.6) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.76 (0.70-0.84) | 0.70 (0.62-0.79) | 0.77 (0.69-0.87) | <.001 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.81 (0.74-0.89) | 0.81 (0.72-0.92) | 0.88 (0.77-0.99) | .02 |

| Total mortality | |||||

| No. of participants | 3572 | 5049 | 1995 | 1806 | |

| No. (%) of events | 650 (18.2) | 707 (14.0) | 259 (13.0) | 261 (14.4) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.73 (0.66-0.81) | 0.65 (0.57-0.75) | 0.73 (0.63-0.85) | <.001 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.79 (0.71-0.88) | 0.77 (0.66-0.90) | 0.86 (0.74-1.00) | .01 |

| Major CVD events | |||||

| No. of participants | 3572 | 5049 | 1995 | 1806 | |

| No. (%) of events | 656 (18.4) | 781 (15.5) | 286 (14.3) | 297 (16.4) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.80 (0.72-0.89) | 0.72 (0.62-0.82) | 0.82 (0.72-0.95) | <.001 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.81 (0.73-0.90) | 0.77 (0.66-0.89) | 0.87 (0.76-1.01) | .02 |

| Myocardial infarction | |||||

| No. of participants | 3572 | 5049 | 1995 | 1806 | |

| No. (%) of events | 155 (4.34) | 224 (4.44) | 101 (5.06) | 111 (6.15) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.96 (0.79-1.18) | 1.06 (0.82-1.36) | 1.28 (1.00-1.63) | .04 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.90 (0.73-1.11) | 0.97 (0.74-1.25) | 1.16 (0.90-1.49) | .21 |

| Stroke | |||||

| No. of participants | 3572 | 5049 | 1995 | 1806 | |

| No. (%) of events | 173 (4.8) | 211 (4.2) | 75 (3.8) | 74 (4.1) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.83 (0.67-1.01) | 0.72 (0.55-0.95) | 0.79 (0.60-1.04) | .03 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.83 (0.68-1.02) | 0.75 (0.57-1.00) | 0.82 (0.62-1.09) | .09 |

| Sudden cardiac death | |||||

| No. of participants | 3572 | 5049 | 1995 | 1806 | |

| No. (%) of events | 202 (5.6) | 170 (3.4) | 63 (3.2) | 72 (4.0) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.56 (0.46-0.69) | 0.51 (0.38-0.68) | 0.64 (0.49-0.84) | <.001 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.61 (0.49-0.75) | 0.60 (0.45-0.81) | 0.73 (0.55-0.98) | .006 |

| CVD death | |||||

| No. of participants | 3572 | 5049 | 1995 | 1806 | |

| No. (%) of events | 416 (11.6) | 433 (8.6) | 138 (6.9) | 148 (8.2) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.70 (0.61-0.80) | 0.55 (0.45-0.66) | 0.65 (0.54-0.79) | <.001 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.76 (0.66-0.87) | 0.66 (0.54-0.80) | 0.78 (0.64-0.94) | <.001 |

| Non-CVD death | |||||

| No. of participants | 3572 | 5049 | 1995 | 1806 | |

| No. (%) of events | 234 (6.6) | 274 (5.4) | 121 (6.1) | 113 (6.3) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 [Reference] | 0.78 (0.66-0.93) | 0.84 (0.68-1.05) | 0.88 (0.70-1.10) | .23 |

| Multivariable | 1 [Reference] | 0.84 (0.70-1.01) | 0.97 (0.77-1.22) | 1.00 (0.79-1.26) | .86 |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; IQR, interquartile range; ONTARGET, Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination With Ramipril Global End Point Trial; ORIGIN, Outcome Reduction With Initial Glargine Intervention; PURE, Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology; TRANSCEND, Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease.

Adjusted for age, sex and study center (latter as random effect). Multivariable model is adjusted for age, sex, study center (random effect), body mass index, educational level (primary or less; secondary; trade, college, or university), smoking status (never, former, or current), alcohol intake, physical activity (low, <600; moderate, 600-3000; high, >3000 metabolic equivalent of task per minute per week), urban or rural location, history of diabetes, cancer, use of statin or antihypertension medications, and intake of fruit, vegetables, red meat, poultry, dairy, and total energy.

In ONTARGET and TRANSCEND combined and in the ORIGIN trial, physical activity categories were: mainly sedentary (reference standard); 1 to 4 times per week; and more than 4 times per week.

ONTARGET and TRANSCEND combined and the ORIGIN trial also adjusted for treatment allocation.

Figure 1. Fish Intake vs Risk of Composite of Death or Major Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) by Study and by Prior Cardiovascular Disease.

aAdjusted for age, sex, study center (random effect), body mass index, educational level, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol intake, urban vs rural location, history of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, use of statin or antihypertension medication, and intake of fruit, vegetables, red meat, poultry, dairy, and total energy.

By contrast, in 2 cohorts of patients with vascular diseases (ONTARGET and TRANSCEND study, 40 countries, and 6 continents), a higher fish intake of at least 175 g/wk (approximately 2 servings/wk) was associated with lower risk of major CVD (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.80-1.00), CVD mortality (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.74-1.02), non-CVD mortality (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.68-1.01), and total mortality (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76-0.98) compared with 50 g/mo or lower, with no further apparent decrease in HR with consumption of 350 g/wk or higher (Table 2; eFigure 4 in the Supplement).

In the ORIGIN study of patients with vascular dieases (40 countries, 5 continents), a higher fish intake of at least 175 g/wk (approximately 2 servings/wk) was associated with lower risk of major CVD (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.66-0.89), CVD mortality (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.54-0.80), and total mortality (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.66-0.90) compared with 50 g/mo or lower, with no further apparent decrease in HR with consumption of 350 g/wk or higher (Table 2; eFigure 4 in the Supplement).

Collectively, in the 3 cohorts of patients with vascular disease, a minimal fish intake of 175 g/wk (approximately 2 servings/wk) was associated with lower major CVD (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.96) and total mortality (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.74-0.91) compared with 50 g/mo or lower, with no additional benefit with consumption of 350 g/wk or more.

Similar results were found when waist to hip ratio replaced body mass index in the multivariable models and also when waist to hip ratio, body mass index, hypertension, and diabetes were dropped from the models (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Lastly, when participants with an event in the first 2 years were excluded, the findings were unchanged (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

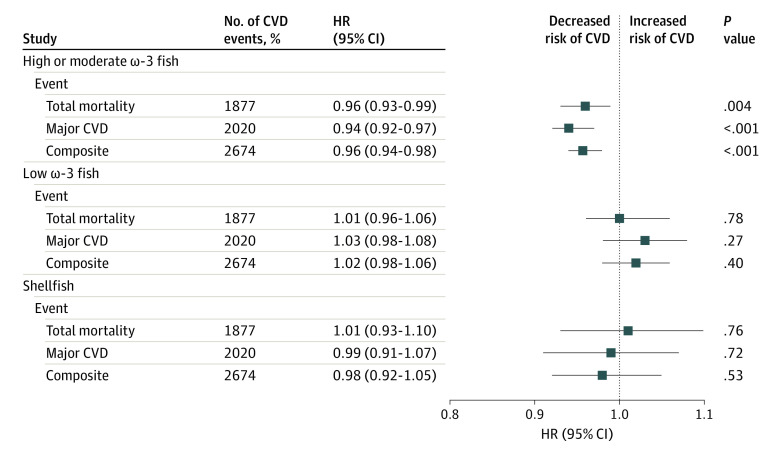

In the ORIGIN study, types of fish with higher amounts of ω-3 fats were strongly associated with a lower risk of major CVD events (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.92-0.97 per 5-g increment of intake), whereas other types of fish were neutral (Figure 2).30 Similar protective associations of high ω-3 fish were found for sudden cardiac death (HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.86-0.96 per 5-g increment of intake; P < .001), whereas other types of fish were found to be neutral (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.88-1.09; P = .69).

Figure 2. Associations Between Types of Fish (per 5-g Increment) and Clinical Events in the Outcome Reduction With Initial Glargine Intervention (ORIGIN) Trial (n = 12 422).

Data are adjusted for age, sex, study center (random effect), body mass index, educational level, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol intake, history of diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), cancer, use of statin or antihypertension medication, and intake of fruit, vegetables, red meat, poultry, and dairy. Fish with highest ω-3 levels included herring, mackerel, sable, salmon, tuna (steak), and sardine. Other fish with high ω-3 levels included anchovy, bluefish, oyster, tuna (can), salmon (can), and trout. Fish with lowest ω-3 levels included bass, barramundi, bream, flathead, flounder, perch, snapper, octopus, sword fish, tile fish, and shark. Shellfish included crab, lobster, scallop, and mussel.30 HR represents hazard ratio.

Heterogeneity of Associations in Those With or Without Vascular Disease

The association of fish intake with major CVD and CVD death varied significantly by history of CVD status (for major CVD, I2 = 82.6 [P = .02]; for death, I2 = 90.8 [P = .001]; for composite of death or CVD, I2 = 87.6 [P = .004]) (Figure 1; eFigure 4 in the Supplement).

Among high-risk individuals or patients with existing vascular disease, a minimal fish intake of 175 g/week (approximately 2 servings/week) was associated with lower risk of major CVD (compared with ≤50 g/month; HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.77-0.92; P = .008), total mortality (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.76-0.91; P < .001), and the composite of death or major CVD (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.80-0.92; P = .002), after adjustment for known confounders (Figure 1; eFigure 4 in the Supplement), with no further apparent decrease in HR with consumption of 350 g/week or higher. No significant heterogeneity in the associations with the composite outcome was found across regions.

By contrast, in general populations without vascular disease, a higher fish intake was not significantly associated with major CVD (comparing ≥350 g/wk vs ≤50 g/mo; HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.88-1.08; P = .24), total mortality (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.88-1.06; P = .48), or the composite of death or major CVD (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.90-1.04; P = .18) (Figure 1; eFigure 4 in the Supplement).

Similarly, among high-risk individuals or patients with existing vascular disease, a higher fish intake was associated with lower risk of sudden cardiac death (comparing ≥350 g/wk with ≤50 g/mo; HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.63-0.99; P = .04). By contrast, in general populations without vascular disease, a higher fish intake was not significantly associated with these events (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.64-1.89; P = .91).

Associations by Geographic Region

In PURE, higher fish intake appeared to be associated with a lower risk of composite events in China and Africa but appeared to be neutral in other regions. For patients with vascular disease, similar associations were found across regions.

Associations of Fish Intake With Cardiovascular Risk Markers

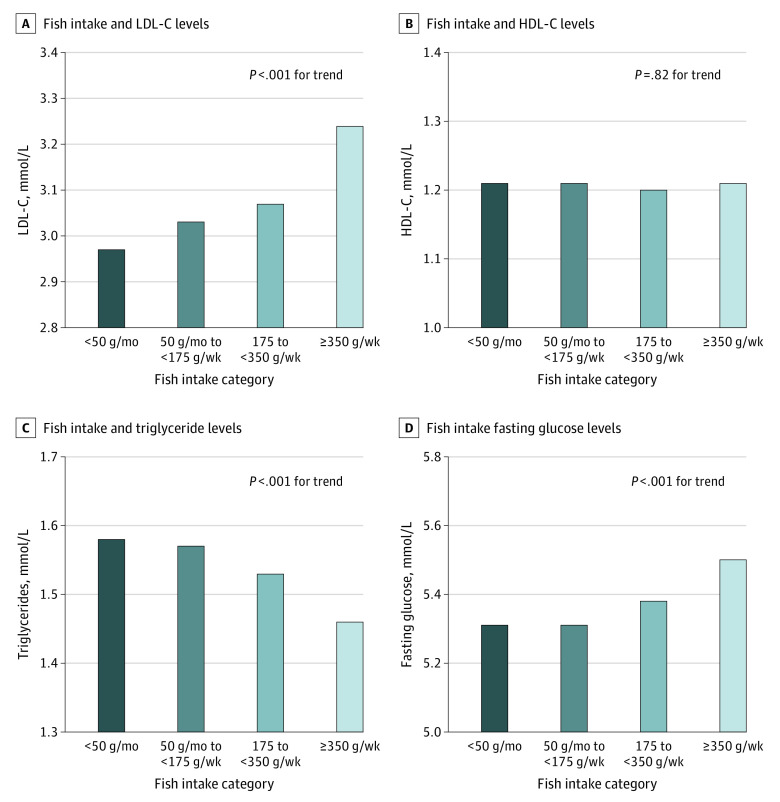

Higher fish intake was associated with lower triglyceride levels both among people with or without vascular disease (Figure 3; eTable 1 in the Supplement). However, no beneficial associations were found with other risk markers, and there were higher levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) (Figure 3; eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Figure 3. Mean Levels of Cardiovascular Risk Markers by Amount of Fish Intake in the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) Trial (n = 147 541).

Data adjusted for age, sex, study center (random effect), body mass index, educational level, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol intake, urban vs rural location, history of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, use of statin or antihypertension medication, and intake of fruit, vegetables, red meat, poultry, dairy, and total energy. LDL-C represents low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Discussion

In this analysis of 4 international prospective cohort studies with 15 390 major CVD events and 15 712 deaths, among 191 558 people from 58 countries in 6 continents, we noted significant heterogeneity in the association between fish intake and major CVD events by history of CVD status. Lower risk of major CVD, total mortality, and their composite was found with higher fish intake of at least 175 g/wk (approximately 2 servings) among high-risk individuals or patients with vascular disease, but not in general populations without vascular disease. A similar pattern of results was found for sudden cardiac death, with significant protective associations observed among patients with vascular disease, but neutral in general populations without vascular disease. Furthermore, the data available from 1 study on types of fish suggested that oily fish but not other types of fish were associated with greater benefits.

Dietary guidelines generally encourage consumption of a variety of fish, preferably oily types (eg, salmon, sardines, tuna, and mackerel), at least twice a week for CVD prevention.1,2,31,32,33 High-dose fish oil has been shown to lower triglyceride levels in people with severe hypertriglyceridemia.6,7 Furthermore, short-term trials showed that 2 servings of fatty fish per week (roughly 112 g [4 oz] each) decreased triglyceride levels by 11.4% but also slightly increased LDL-C levels compared with the control diet.34,35 Our findings are consistent with this information, both among people with and among persons without vascular disease (8% decrease in triglyceride level with approximately 2 standard servings of fish per week but with slightly higher LDL-C level). The increase in LDL-C level associated with fish intake may not suggest an increased CVD risk because this risk may be offset by the positive effects on lipoproteins.36 Our finding of higher blood glucose levels associated with higher fish intake is consistent with some trial data for patients with diabetes,37 but other trials of fish or fish oil consumption have been neutral regarding this factor.38 Cohort studies of fish intake and incident diabetes have shown variable results.39,40 Cooking methods, mercury levels, and the presence of polychlorinated biphenyls or other environmental contaminants in fish are potential factors associated with the different findings across studies,41 but further work is needed in this area. Given that there are associations with CVD risk markers, some of which may be protective and others harmful, and that some fish may contain contaminants,42,43 studying the association of fish intake with outcome events is essential to inform recommendations for populations.

To our knowledge, there are no primary prevention trials on fish intake and CVD outcomes. Some prospective cohort studies among mostly healthy people have found an inverse association between fish intake and CVD mortality, whereas others do not.44 A recent umbrella review of cohort studies found modest protective associations of fish consumption with fatal coronary heart disease (ie, summary relative risks ranging from 2% to 15% lower risk).14 Compared with fatal cardiac events, fish consumption has weaker associations with nonfatal cardiac events and stroke.14,44 However, those meta-analyses were not based on combining individual data from each study and thus were not able to fully adjust for all potential confounders. In PURE, which covers fish intake in numerous world regions in which various amounts and types of fish are consumed, we found no significant association of fish intake with outcome events. In analyses by geographic region, we found considerable heterogeneity across geographic regions, but associations were neutral in most regions except for China and Africa, where protective associations between fish intake and composite events were detected. Taken together, the results suggest that higher fish consumption may be modestly associated with CVD outcomes or mortality in generally healthy populations.

Our findings of favorable associations of fish intake with CVD events and mortality among patients with vascular disease are consistent with the DART-1 (Diet and Reinfarction) trial,45 but not the DART 2 study46 or 2 recent meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials of fish oil supplementation for high-risk individuals, which showed that fish oil (approximately 1 g/d) had no association with CVD outcomes or total mortality.8,9 More recently, in 2018, 2 trials of a 1-g/d ω-3 formulation found no significant effect of supplementation on major CVD, but there was significant lowering of fatal myocardial infarction, total coronary heart disease,12 and fatal CVD.11 In a 2019 meta-analysis10 that included those new trials,11,12 individuals who received ω-3 supplementation had significantly better CVD outcomes, even after excluding the recent REDUCE-IT randomized clinical trial of patients with elevated triglyceride levels that used a much higher dose of fish oil (4 g daily).13 In our study, CVD risk was lowest with a moderate amount of fish (ie, at least 175 g/wk, or approximately 2 servings/wk), with no further apparent decrease in risk with higher fish intake (ie, >350 g/wk, or >3-4 servings/wk). Similarly, previous cohort studies of mostly generally healthy populations showed that approximately 2 or more servings/wk (150 g/wk) is associated with the lowest CVD risk.14,44 On this basis, 2 servings of fish per week may be the minimal amount of fish needed to reach maximum benefit (an amount consistent with current recommendations for CVD prevention),1,2,31,32,33 with little additional benefit with higher intakes among patients with vascular disease. As expected in ORIGIN, for which we collected information on types of fish, consumption of fish with higher amounts of ω-3 fats was strongly associated with a lower risk of major CVD, whereas consumption of other types of fish was found to be neutral. These findings are compatible with trials showing favorable effects of oily fish intake on CVD risk markers.6 In addition, fish may have selective antiarrhythmic effects and accompanying protection against sudden cardiac death.3,4,8 Some47 but not all48,49 trials of patients with vascular disease found that fish oil use results in a lower risk of sudden cardiac death. In our cohorts of patients with vascular disease, we found protective associations of fish intake (mainly from high ω-3 fish) with sudden death (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.63-0.99, comparing >350 g/wk vs <50 g/mo). Collectively, a possible modest cardiovascular benefit (ie, approximately 10%-15% risk lowering) was found to be associated with consuming an equivalent of at least 175 g (2 servings) of fish weekly and with similar protection for more than 350 g (approximately 4 servings) weekly for secondary prevention. However, our findings require confirmation from randomized clinical trials evaluating the effects of increasing fish consumption (especially oily fish) on the clinical outcomes of people with vascular disease.

Limitations

The first potential limitation of this study is that diet was self-reported, and variations in reporting may lead to random errors that could dilute real associations between fish intake and clinical outcomes. Second, we were not able to consider cooking methods, how the fish was consumed (with sauces, smoked, salted, etc), or contaminants in fish, which may also affect the results. Furthermore, we were not able to conduct a separate assessment of oily fish in PURE, which could at least partly explain the overall null findings. Third, in observational studies, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be completely ruled out (eg, fish intake may be a proxy for poverty or access to health care). However, our results persisted despite extensive adjustments for all known confounders, including the use of 4 markers of socioeconomic status (educational level, wealth, urban vs rural location, and geographic location). In addition, we adjusted for study center as a random effect, which takes into account socioeconomic factors and clustering by community, leading to comparisons within countries (eAppendix in the Supplement). Lastly, some misclassification of fish intake cannot be ruled out because we did not have repeated measures of diet in all studies, and a full-length FFQ was used only in PURE. However, the ORIGIN study, in which we conducted repeated diet assessments at 2 years, showed similar results based on the first vs second diet assessments, indicating that misclassification of fish intake during follow-up was not a major factor in our findings (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Conclusions

In summary, this study found that a minimal fish intake of 175 g (approximately 2 servings) weekly was associated with lower risk of major CVD events and total mortality among high-risk individuals or patients with existing vascular disease but not in the general population.

eAppendix 1. Methods

eReferences.

eFigure 1. PURE Participants Included in These Analyses

eFigure 2. Median Fish Consumption (Grams per Week) by Geographic Region in PURE

eFigure 3. Mean Values of Other Cardiovascular Risk Markers by Level of Fish Intake in PURE

eFigure 4. Fish Intake and Mortality

eFigure 5. Fish Intake and Major Cardiovascular Disease

eTable 1. Fish Intake and Risk Markers in the ONTARGET/TRANSCEND and ORIGIN studies

eTable 2. Sensitivity Analyses of Associations of Fish Intake vs Composite of Death or Major CVD

eTable 3. Comparison of the Associations of Initial and Repeat Fish Intake Measures at 2-years vs Composite of Death or Major CVD Events in the ORIGIN Study

eTable 4. PURE Country Institution Names

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Population nutrient intake goals for preventing diet-related chronic diseases. Accessed December 15, 2019. https://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/5_population_nutrient/en/

- 2.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596-e646. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimmig LM, Karalis DG. Do omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids prevent cardiovascular disease? a review of the randomized clinical trials. Lipid Insights. 2013;6:13-20. doi: 10.4137/LPI.S10846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gebauer SK, Psota TL, Harris WS, Kris-Etherton PM. n-3 Fatty acid dietary recommendations and food sources to achieve essentiality and cardiovascular benefits. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(6)(suppl):1526S-1535S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1526S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tørris C, Småstuen MC, Molin M. Nutrients in fish and possible associations with cardiovascular disease risk factors in metabolic syndrome. Nutrients. 2018;10(7):E952. doi: 10.3390/nu10070952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mozaffarian D, Wu JH. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: effects on risk factors, molecular pathways, and clinical events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(20):2047-2067. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu JH, Mozaffarian D. ω-3 Fatty acids, atherosclerosis progression and cardiovascular outcomes in recent trials: new pieces in a complex puzzle. Heart. 2014;100(7):530-533. Published online January 23, 2014. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-305257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizos EC, Ntzani EE, Bika E, Kostapanos MS, Elisaf MS. Association between omega-3 fatty acid supplementation and risk of major cardiovascular disease events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;308(10):1024-1033. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdelhamid AS, Brown TJ, Brainard JS, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7:CD003177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu Y, Hu FB, Manson JE. Marine omega-3 supplementation and cardiovascular disease: an updated meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials involving 127 477 participants. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(19):e013543. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowman L, Mafham M, Wallendszus K, et al. ; ASCEND Study Collaborative Group . Effects of n-3 fatty acid supplements in diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(16):1540-1550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. ; VITAL Research Group . Marine n-3 fatty acids and prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):23-32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al. ; REDUCE-IT Investigators . Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):11-22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jayedi A, Shab-Bidar S. Fish consumption and the risk of chronic disease: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies. Adv Nutr. 2020;11(5):1123-1133. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmaa029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yusuf S, Islam S, Chow CK, et al. ; Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) Study Investigators . Use of secondary prevention drugs for cardiovascular disease in the community in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (the PURE Study): a prospective epidemiological survey. Lancet. 2011;378(9798):1231-1243. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61215-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corsi DJ, Subramanian SV, Chow CK, et al. Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study: baseline characteristics of the household sample and comparative analyses with national data in 17 countries. Am Heart J. 2013;166(4):636-646.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chow CK, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, et al. ; PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology) Study investigators . Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA. 2013;310(9):959-968. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.184182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teo K, Lear S, Islam S, et al. ; PURE Investigators . Prevalence of a healthy lifestyle among individuals with cardiovascular disease in high-, middle- and low-income countries: the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. JAMA. 2013;309(15):1613-1621. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yusuf S, Rangarajan S, Teo K, et al. ; PURE Investigators . Cardiovascular risk and events in 17 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):818-827. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al. ; ONTARGET Investigators . Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(15):1547-1559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yusuf S, Teo K, Anderson C, et al. ; Telmisartan Randomised AssessmeNt Study in ACE iNtolerant subjects with cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Investigators . Effects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9644):1174-1183. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61242-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerstein HC, Bosch J, Dagenais GR, et al. ; ORIGIN Trial Investigators . Basal insulin and cardiovascular and other outcomes in dysglycemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(4):319-328. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosch J, Gerstein HC, Dagenais GR, et al. ; ORIGIN Trial Investigators . n-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with dysglycemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(4):309-318. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mente A, Dehghan M, Rangarajan S, et al. ; Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study investigators . Association of dietary nutrients with blood lipids and blood pressure in 18 countries: a cross-sectional analysis from the PURE study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(10):774-787. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30283-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dehghan M, Mente A, Zhang X, et al. ; Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study investigators . Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2017;390(10107):2050-2062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32252-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burke DL, Ensor J, Riley RD. Meta-analysis using individual participant data: one-stage and two-stage approaches, and why they may differ. Stat Med. 2017;36(5):855-875. doi: 10.1002/sim.7141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Groll A, Hastie T, Tutz G. Selection of effects in Cox frailty models by regularization methods. Biometrics. 2017;73(3):846-856. doi: 10.1111/biom.12637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dehghan M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, et al. ; Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study investigators . Association of dairy intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 21 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2018;392(10161):2288-2297. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31812-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements . Omega 3 fatty acids. Accessed March 15, 2020. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Omega3FattyAcids-HealthProfessional/

- 31.Brownie S, Muggleston H, Oliver C. The 2013 Australian dietary guidelines and recommendations for older Australians. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44(5):311-315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Department of Health . Dietary guidelines for Americans 2015–2020, eighth edition. Published December 2015. Accessed January 2021. https://health.gov/our-work/food-nutrition/previous-dietary-guidelines/2015

- 33.Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(29):2315-2381. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajaram S, Haddad EH, Mejia A, Sabaté J. Walnuts and fatty fish influence different serum lipid fractions in normal to mildly hyperlipidemic individuals: a randomized controlled study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(5):1657S-1663S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raatz SK, Johnson LK, Rosenberger TA, Picklo MJ. Twice weekly intake of farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) positively influences lipoprotein concentration and particle size in overweight men and women. Nutr Res. 2016;36(9):899-906. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2016.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Theobald HE, Chowienczyk PJ, Whittall R, Humphries SE, Sanders TA. LDL cholesterol-raising effect of low-dose docosahexaenoic acid in middle-aged men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(4):558-563. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.4.558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karlström BE, Järvi AE, Byberg L, Berglund LG, Vessby BO. Fatty fish in the diet of patients with type 2 diabetes: comparison of the metabolic effects of foods rich in n-3 and n-6 fatty acids. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(1):26-33. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.006221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen C, Yu X, Shao S. Effects of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on glucose control and lipid levels in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0139565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wallin A, Di Giuseppe D, Orsini N, Patel PS, Forouhi NG, Wolk A. Fish consumption, dietary long-chain n-3 fatty acids, and risk of type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(4):918-929. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forouhi NG, Misra A, Mohan V, Taylor R, Yancy W. Dietary and nutritional approaches for prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. BMJ. 2018;361:k2234. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nanri A, Mizoue T, Noda M, et al. ; Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study Group . Fish intake and type 2 diabetes in Japanese men and women: the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(3):884-891. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.012252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheehan MC, Burke TA, Navas-Acien A, Breysse PN, McGready J, Fox MA. Global methylmercury exposure from seafood consumption and risk of developmental neurotoxicity: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(4):254-269F. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.116152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sioen I, De Henauw S, Van Camp J, Volatier JL, Leblanc JC. Comparison of the nutritional-toxicological conflict related to seafood consumption in different regions worldwide. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2009;55(2):219-228. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2009.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mozaffarian D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: a comprehensive review. Circulation. 2016;133(2):187-225. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burr ML, Fehily AM, Gilbert JF, et al. Effects of changes in fat, fish, and fibre intakes on death and myocardial reinfarction: diet and reinfarction trial (DART). Lancet. 1989;2(8666):757-761. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90828-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burr ML, Ashfield-Watt PA, Dunstan FD, et al. Lack of benefit of dietary advice to men with angina: results of a controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57(2):193-200. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Casula M, Soranna D, Catapano AL, Corrao G. Long-term effect of high dose omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for secondary prevention of cardiovascular outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo controlled trials. Atheroscler Suppl. 2013;14(2):243-251. Published correction appears in Atheroscler Suppl. 2014;233(1):122. doi: 10.1016/S1567-5688(13)70005-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hooper L, Thompson RL, Harrison RA, et al. Risks and benefits of omega 3 fats for mortality, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332(7544):752-760. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38755.366331.2F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marik PE, Varon J. Omega-3 dietary supplements and the risk of cardiovascular events: a systematic review. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32(7):365-372. doi: 10.1002/clc.20604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Methods

eReferences.

eFigure 1. PURE Participants Included in These Analyses

eFigure 2. Median Fish Consumption (Grams per Week) by Geographic Region in PURE

eFigure 3. Mean Values of Other Cardiovascular Risk Markers by Level of Fish Intake in PURE

eFigure 4. Fish Intake and Mortality

eFigure 5. Fish Intake and Major Cardiovascular Disease

eTable 1. Fish Intake and Risk Markers in the ONTARGET/TRANSCEND and ORIGIN studies

eTable 2. Sensitivity Analyses of Associations of Fish Intake vs Composite of Death or Major CVD

eTable 3. Comparison of the Associations of Initial and Repeat Fish Intake Measures at 2-years vs Composite of Death or Major CVD Events in the ORIGIN Study

eTable 4. PURE Country Institution Names