Abstract

Background

Nivolumab has been associated with immune‐related adverse events, including nephritis, with acute interstitial nephritis being the most commonly reported renal manifestation.

Case

We describe the first case to our knowledge of minimal change disease with nephrotic syndrome associated with the PD‐1 checkpoint inhibitor, Nivolumab. Minimal change disease has been reported with other immune checkpoint inhibitors; however, this is the first reported case with Nivolumab. We report development of nephrotic syndrome with acute kidney injury in a 57‐year‐old man, 1 month after commencement of Nivolumab for metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Minimal change disease was confirmed by renal biopsy. Management with corticosteroids and cessation of Nivolumab failed to improve kidney function or nephrosis.

Conclusion

This case adds to current literature identifying minimal change as an additional complication of immune checkpoint inhibitor‐associated acute kidney injury. Given the increasing use of immune checkpoint inhibitors for a range of malignancies, nephrologists, oncologist and generalists should be aware of the spectrum of kidney pathologies associated with their use.

Keywords: immune related adverse event, immune‐mediated nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, Nivolumab, onconephrology

1. BACKGROUND

Use of immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibition (ICPI) for treatment of metastatic solid organ cancers and lymphoma has rapidly increased. Their efficacy is derived from blockade of the interaction between T cell receptors (Programmed Death‐1 [PD‐1] and cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte‐associated protein‐4 [CTLA‐4]), and their ligands expressed by tumor cells (PD‐Ligand‐1) and antigen presenting cells (CD80/86). Engagement of these T cell receptors by their ligands leads to T cell deactivation. Thus, blocking engagement frees T cells from such inhibition and promotes an antitumor response. Nivolumab is a monoclonal antibody that specifically blocks the PD‐1 receptor. 1 Although precise mechanisms are yet to be elucidated, subsequent modulation of T‐cell regulation is the proposed mechanism underlying the common occurrence of immune‐related adverse events, including nephritis. 2 Immune nephritis has been reported at rates of up to 5% with combination immunotherapy (CTLA4 and PD‐1 inhibitors) 3 and 2% with single‐agent PD‐1 inhibition. 4 Acute interstitial nephritis has predominantly been reported, although case reports detail other immune‐mediated glomerulonephritis, acute tubular injury, and minimal change disease with other ICPIs. 5 Here we report the first case, to our knowledge, of minimal change disease, with nephrotic syndrome, associated with PD‐1 receptor antibody, Nivolumab.

1.1. Case presentation

A 57‐year‐old male with metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue‐commenced palliative, second‐line immunotherapy with Nivolumab. Prior treatment included primary surgical resection followed by palliative chemotherapy with three cycles of 5‐Fluorouracil and carboplatin, following the development of bone, liver, and lung metastases 2 months postsurgical resection (Table 1). He had a suboptimal response to chemotherapy, at which point Nivolumab was initiated.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Patient characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age | 57 |

| Race | Caucasian |

| Sex | Male |

| Malignancy | Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, tongue |

| Baseline creatinine | ~70 μmol/L |

| Comorbidities | Atrial fibrillation, cardiomyopathy, rectal carcinoma, transient ischemic attack, peptic ulcer disease, gout |

| Medications | Digoxin, warfarin, bisoprolol, perindopril, colchicine |

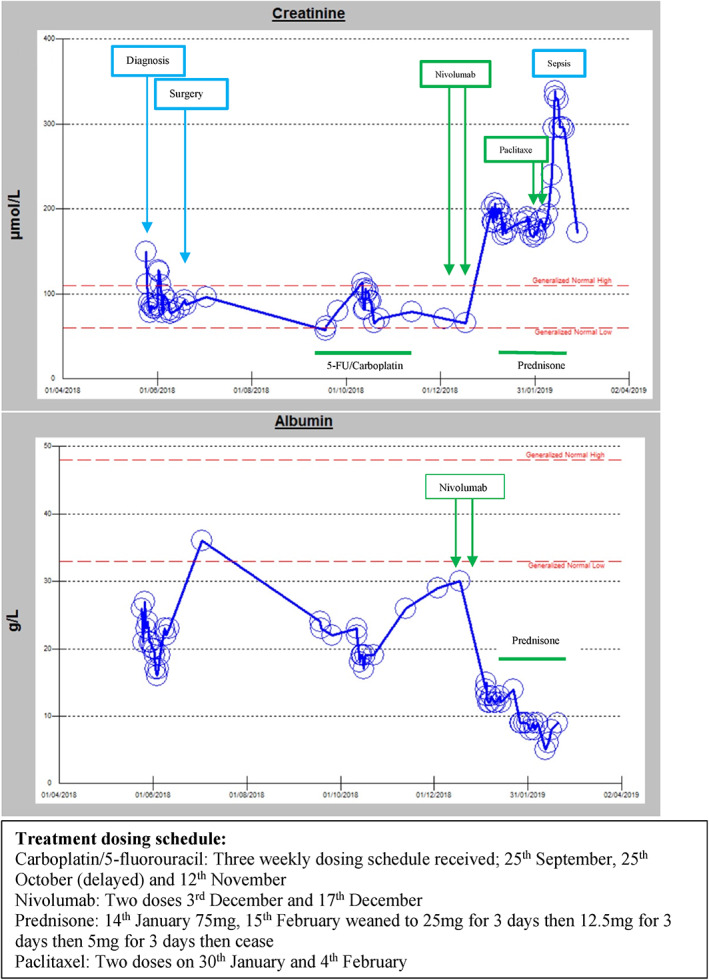

Comorbidities included an incidentally diagnosed synchronous early rectal adenocarcinoma, managed conservatively given his advanced head and neck cancer, alcohol‐induced cardiomyopathy (recent normal ejection fraction), atrial fibrillation, and peptic ulcer disease. Medications prior to commencing immunotherapy included digoxin, warfarin, bisoprolol, perindopril, and colchicine. There was no recent history of proton pump inhibitor use. Baseline kidney function was a creatinine between 70 and 90 μmol/L with no prior documented urinary sediment. Episodes of elevated creatinine prior to commencement of immunotherapy were in the context of surgical resection of the primary tumor and presumed prerenal kidney injury in the setting of chemotherapy and poor oral intake (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Graphical representation of kidney response to treatment

One month after commencing Nivolumab, having received two doses, symptomatic nephrotic syndrome developed with marked peripheral and scrotal edema and small bilateral pleural effusions. Serum creatinine increased from 70 μmol/L pre‐Nivolumab to 202 μmol/L, serum albumin was markedly reduced (14 g/L). Urine studies revealed an albumin/creatinine ratio of 2137 mg/mmol and normal urine microscopy and sediment; specifically, less than 109 red cells, white cells and no dysmorphic cells or casts. Viral serologies were negative for hepatitis B and C. Mild hypothyroidism (TSH 5.6 mIU/L, free T4 10.1 pmol/L, free T3 3.3 pmol/L) was present in the absence of detectable antithyroid antibodies. A renal ultrasound was normal. Nivolumab was discontinued and treatment with high dose prednisolone (75 mg/day) was initiated. An urgent kidney biopsy showed histopathology most consistent with minimal change disease, although was limited by processing artifact. Light microscopy displayed mildly ischemic glomeruli with periglomerular fibrosis. Electron microscopy revealed marked podocyte effacement, moderate focal ischemic changes, patchy interstitial infiltrate and no dense deposits. In addition to high dose steroids, furosemide 80 mg was commenced for symptomatic management of nephrotic syndrome. Renal function stabilized but did not improve; creatinine 199 μmol/L, albumin 12 g/L at point of discharge from hospital. Two weeks later he was readmitted with functionally limiting edema and hypoalbuminemia (creatinine 199 μmol/L, albumin 9 g/L). Progression of his head and neck malignancy, with significant growth of the right‐sided neck mass, was also noted and third line treatment with paclitaxel chemotherapy was commenced; 1 month after development of nephropathy (Figure 1). He received two doses of paclitaxel and subsequently developed febrile neutropenia, associated with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia bacteremia, and a further decline in his renal function. Following extensive discussions, a decision was made to cease active therapy, including additional immunosuppression for nephropathy, and pursue a palliative management approach. The patient died 77 days later.

2. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first case report of minimal change disease (MCD) causing nephrotic syndrome as an immune‐related adverse event secondary to Nivolumab use.

ICPI‐AKI occurred in 2.2% of patients in initial phase II and III clinical trials. 3 Similar event rates were reported in a recent meta‐analysis of patients treated with other PD‐1 therapies. 4 A spectrum of kidney diseases secondary to ICPI therapy have been recently described in single case reports, with the most commonly described lesion being acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (AIN). 6 , 7 , 8 Nivolumab has been associated with cases of AIN, 5 , 9 , 10 immune‐mediated glomerulonephritis, 11 membranous glomerulonephritis, 5 IgA nephropathy, 5 , 12 and nephrotic syndrome secondary to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. 13 Earlier case reports have detailed the increased risk of ICPI‐AKI with the use of dual or sequential therapy with PD‐1 and CTLA‐4‐inhibitors 3 , 6 and a variable time of disease onset posttreatment with acute interstitial nephritis generally manifesting as a later occurrence. 7 These findings were confirmed in a recent multicentered case series, including 138 patients, where they also described independent risk factors for ICPI‐AKI including poor baseline kidney function, proton pump inhibitor use, and combination therapy with CTLA‐4 and PD‐1 inhibitors. 14 In addition, concomitant extrarenal irAEs were found to be associated with failure to achieve kidney recover after AKI and failure of recovery was associated with an increased risk of mortality, as seen in our patient. On review of two earlier published immunotherapy nephritis case series; concurrent thyroid dysfunction was noted in six of 29 nephritis cases and concurrent immune‐toxicities, of any kind, in 17 of 26 cases. 5 , 15

Although this is the first reported case of MCD with Nivolumab, there have been other cases of MCD reported to occur with other CPI therapies including the CTLA‐4 inhibitor, Ipilimumab, 15 , 16 and other PD‐1 inhibitors; Pembrolizumab 17 and Camrelizumab 18 (Table 2), suggesting a common immunological mechanism underpinning the kidney pathology.

TABLE 2.

Minimal change disease associated with check point inhibitors

| Author | Disease | Immunotherapy | Time of onset (days) | Clinical presentation | Biopsy result | Treatment | Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidd and Gizaw 15 , 2016 | Metastatic melanoma | Ipilimumab (CTLA‐4 inhibitor) | — | NS, AKI |

EM: Diffuse podocyte effacement LM: Marked eosinophilic infiltration. IF negative |

Drug discontinuation. High dose prednisolone (2 mg/kg) | NS: CRAKI: PR |

| Bickel et al 17 , 2016 | Mesothelioma | Pembrolizumab (anti‐PD1) | 10 | NS | EM: Diffuse fusions of the epithelial foot processesNormal LM and negative IF |

Drug discontinuation Prednisolone (1 mg/kg) Diuretics ACE inhibition |

CR |

| Kitchlu et al 16 , 2017 (1) | Hodgkins lymphoma | Pembrolizumab (Anti‐PD1) | 28 | NS, AKI |

EM: Diffuse foot process effacement LM: Focal tubular injury and mild interstitial fibrosisIF linear IgG of basement membrane |

Drug discontinuation High dose prednisolone (2 mg/kg) Alternating dexamethasone |

PR |

| Kitchlu et al16, 2017 (2) | Metastatic melanoma | Ipilimumab (CTLA4 inhibitor) | 540 (18 mo) | NS | EM: diffuse foot process effacementLM: normal. negative IF | Drug discontinuation High dose prednisolone (1 mg/kg) |

CR Relapse with rechallenge |

| Gao 18 , 2018 | Hodgkins lymphoma | Camrelizumab (anti‐PD1) | 30 | NS | EM: diffuse podocyte foot process effacementNormal LM and negative IF | Drug discontinuation followed by prednisolone (1 mg/kg) | CR |

Abbreviations: ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; AKI, acute kidney injury; CR, complete remission; CTLA4 inhibitor, cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte‐associated protein‐4; EM, electron microscopy; IF; immunofluorescence; LM, light microscopy; NS, nephrotic syndrome; PR, partial remission; PD1, programmed death‐1 antibody.

Paraneoplastic nephropathy was a key differential in this case, given the synchronous rectal and head and neck cancers. MCD is the second most common paraneoplastic glomerulopathy after membranous nephropathy. It has been reported to occur in association with numerous types of solid organ cancers, most commonly colorectal, lung, renal cell cancers and thymoma. 19 To our knowledge, MCD has not been reported in head and neck cancer; however, it has been reported rarely with rectal cancer. 20 Stabilization of kidney function despite progressive malignancy, and after commencement of steroids and cessation of Nivolumab favors this to be an immune‐related adverse event. Concurrent immunotoxicity with thyroid dysfunction, suggesting Nivolumab had induced an immune response, also favors immunotoxicity over a paraneoplastic phenomenon. The timing after commencing Nivolumab in our case is also consistent with previous case reports, where other PD‐1 inhibitors have been associated with MCD (range 10 to 30 days); a much earlier onset than with AIN or malignancy‐associated MCD. 16 , 17 , 18 At presentation there were no concurrent nephrotoxic medications, intercurrent infections, nor any recent imaging with contrast identified that may have contributed to kidney injury.

The predominant histopathological finding in our patient was podocyte effacement with mild ischemic changes. Although podocyte effacement may coexist with CPI‐mediated AIN histology, 15 the degree of podocyte effacement and severity of nephrotic syndrome in our case favors an alternative predominant immunological process. The pathophysiological mechanisms underpinning the development of minimal change are poorly understood, although T‐cell dysregulation with imbalance of regulatory T cells has been the primary hypothesis. 2 Glomerular epithelial cells give rise to podocytes, the microscopic structure, which support the protein filtration barrier in the glomerulus. We hypothesize that the predisposition to T‐cell‐mediated podocyte damage becomes unmasked as PD‐1 inhibition alters the balance in favor of T effectors over T regulatory cells. This immune mediated podocyte destruction and effacement leads to excessive urinary protein loss and clinically significant nephrotic syndrome, as seen in our patient.

The mainstay treatment for CPI‐induced immune‐related adverse events is high dose corticosteroids. Typically, prednisolone is initiated at doses of 0.5 to 2 mg/kg and continued until there is an improvement in serum creatinine to less than twice baseline levels. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2018 guidelines on immune‐related nephritis recommend tapering over at least 4 weeks, once nephritis has resolved to grade 1, where creatinine is 1.5 to 2 times over baseline. 21 All known reported cases of CPI‐related minimal change disease have been shown to have partial or complete remissions with drug discontinuation and commencement of corticosteroid therapy, especially in cases where renal parenchyma was normal to light microscopy 16 , 17 , 18 (Table 1). If nephritis is severe (grades 3 and 4) and steroid refractory, with no improvement over 2 to 5 days, consideration of additional immunosuppression such as mycophenolate, is recommended. 21 Immune‐related nephritis can be severe and steroid refractory, resulting in the need for dialysis. 3 The lack of response to steroid therapy in our patient may be attributed to duration of therapy, underlying ischemic changes of kidney parenchyma, or an additional risk factor for mortality.

3. CONCLUSIONS

In an era of increasing CPI use for hematological and solid organ malignancies, oncologists, nephrologists, and generalists must be aware of the array of associated adverse kidney immunotoxicities that can occur. The development of minimal change disease following Nivolumab therapy in this case adds to current literature identifying minimal change disease as another autoimmune complication of ICPI therapy. Further research regarding the underlying immune mechanisms and management of immunotherapy induced nephritis is required.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have not received financial or nonfinancial support for the preparation of this manuscript. The authors have stated explicitly that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Conceptualization, E.V., E.C., M.H., S.C.; Methodology, E.V., E.C., M.H., S.C.; Investigation, E.V., E.C., M.H., S.C.; Formal Analysis, E.V., E.C., M.H., S.C.; Resources, E.V., E.C., M.H., S.C.; Writing—Original Draft, E.V., E.C., M.H., S.C.; Writing—Review and Editing, E.V., E.C., M.H., S.C.; Visualization, E.V., E.C., M.H., S.C.; Supervision, E.V., E.C., M.H., S.C.; Funding Acquisition, E.V., E.C., M.H., S.C.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

Verbal consent was obtained from the patient and documented in the medical record.

Vaughan E, Connolly E, Hui M, Chadban S. Minimal change disease in a patient receiving checkpoint inhibition: Another possible manifestation of kidney autoimmunity? Cancer Reports. 2020;3:e1250. 10.1002/cnr2.1250

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Luke JJ, Ott PA. PD‐1 pathway inhibitors: the next generation of immunotherapy for advanced melanoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(6):3479‐3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anderson R, Rapoport BL. Immune dysregulation in cancer patients undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment and potential predictive strategies for future clinical practice. Front Oncol. 2018;8:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cortazar FB, Marrone KA, Troxell ML, et al. Clinicopathological features of acute kidney injury associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Kidney Int. 2016;90(3):638‐647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Manohar S, Kompotiatis P, Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Herrmann J, Herrmann SM. Programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitor treatment is associated with acute kidney injury and hypocalcemia: meta‐analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34(1):108‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mamlouk O, Selamet U, Machado S, et al. Nephrotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors beyond tubulointerstitial nephritis: single‐center experience. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wanchoo R, Karam S, Uppal NN, et al. On behalf of cancer and kidney international network workgroup on immune checkpoint inhibitors: adverse renal effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a narrative review. Am J Nephrol. 2017;45(2):160‐169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Perazella MA, Shirali AC. Nephrotoxicity of cancer immunotherapies: past, present and future. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(8):2039‐2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Izzedine H, Mateus C, Boutros C, et al. Renal effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2016;32(6):936‐942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koda R, Watanabe H, Tsuchida M, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor (nivolumab)‐associated kidney injury and the importance of recognizing concomitant medications known to cause acute tubulointerstitial nephritis: a case report. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Belliere J, Meyer N, Mazieres J, et al. Acute interstitial nephritis related to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(12):1457‐1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jung K, Zeng X, Bilusic M. Nivolumab‐associated acute glomerulonephritis: a case report and literature review. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17(1):188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kishi S, Minato M, Saijo A, et al. A case of IgA nephropathy after nivolumab therapy for postoperative recurrence of lung squamous cell carcinoma. Intern Med. 2018;57(9):1259‐1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Daanen RA, Maas RJH, Koornstra RHT, Steenbergen EJ, van Herpen CML, Willemsen A. Nivolumab‐associated nephrotic syndrome in a patient with renal cell carcinoma: a case report. J Immunother. 2017;40(9):345‐348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cortazar FB, Kibbelaar ZA, Glezerman IG, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitor‐associated AKI: a Multicenter study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(2):435‐446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kidd JM, Gizaw AB. Ipilimumab‐associated minimal‐change disease. Kidney Int. 2016;89(3):720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kitchlu A, Fingrut W, Avila‐Casado C, et al. Nephrotic syndrome with cancer immunotherapies: a report of 2 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(4):581‐585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bickel A, Koneth I, Enzler‐Tschudy A, Neuweiler J, Flatz L, Fruh M. Pembrolizumab‐associated minimal change disease in a patient with malignant pleural mesothelioma. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gao B, Lin N, Wang S, Wang Y. Minimal change disease associated with anti‐PD1 immunotherapy: a case report. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jhaveri KD, Shah HH, Calderon K, Campenot ES, Radhakrishnan J. Glomerular diseases seen with cancer and chemotherapy: a narrative review. Kidney Int. 2013;84(1):34‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kittanamongkolchai WW, Cheungpasitporn WW, LeCates WW. Acute kidney injury in rectal cancer‐associated minimal change disease: a case report. J Nephrol Ther. 2012;2(4):119. https://www.hilarispublisher.com/open‐access/acute‐kidney‐injury‐in‐rectal‐cancer‐associated‐minimal‐change‐disease‐a‐case‐report‐2161‐0959.1000119.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al. Management of immune‐related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(17):1714‐1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.