Abstract

Objectives

The majority of patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 can be managed using virtual care. Dyspnoea is challenging to assess remotely, and the accuracy of subjective dyspnoea measures in capturing hypoxaemia have not been formally evaluated for COVID-19. We explored the accuracy of subjective dyspnoea in diagnosing hypoxaemia in COVID-19 patients.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study of consecutive outpatients with COVID-19 who met criteria for home oxygen saturation monitoring at a university-affiliated acute care hospital in Toronto, Canada from 3 April 2020 to 13 September 2020. Dyspnoea measures were treated as diagnostic tests, and we determined their sensitivity (SN), specificity (SP), negative/positive predictive value (NPV/PPV) and positive/negative likelihood ratios (+LR/−LR) for detecting hypoxaemia. In the primary analysis, hypoxaemia was defined by oxygen saturation <95%; the diagnostic accuracy of subjective dyspnoea was also assessed across a range of oxygen saturation cutoffs from 92% to 97%.

Results

During the study period, 89/501 (17.8%) of patients met criteria for home oxygen saturation monitoring, and of these 17/89 (19.1%) were diagnosed with hypoxaemia. The presence/absence of dyspnoea had limited accuracy for diagnosing hypoxaemia, with SN 47% (95% CI 24% to 72%), SP 80% (95% CI 68% to 88%), NPV 86% (95% CI 75% to 93%), PPV 36% (95% CI 18% to 59%), +LR 2.4 (95% CI 1.2 to 4.7) and −LR 0.7 (95% CI 0.4 to 1.1). The SN of dyspnoea was 50% (95% CI 19% to 81%) when a cut-off of <92% was used to define hypoxaemia. A modified Medical Research Council dyspnoea score >1 (SP 98%, 95% CI 88% to 100%), Roth maximal count <12 (SP 100%, 95% CI 75% to 100%) and Roth counting time <8 s (SP 93%, 95% CI 66% to 100%) had high SP that could be used to rule in hypoxaemia, but displayed low SN (≤50%).

Conclusions

Subjective dyspnoea measures have inadequate accuracy for ruling out hypoxaemia in high-risk patients with COVID-19. Safe home management of patients with COVID-19 should incorporate home oxygenation saturation monitoring.

Keywords: COVID-19, infectious diseases, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of subjective dyspnoea in detecting hypoxaemia in the setting of COVID-19.

The diagnostic accuracy of patient-reported presence of dyspnoea in capturing hypoxaemia was evaluated across a range of oxygen saturation (SpO2) cutoffs from 92% to 97% and stratified based on age, presence of lung disease and date of symptom onset.

Objective dyspnea scales, including the modified Medical Research Council dyspnoea scale and Roth score were also evaluated.

Methodological limitations of the study include the retrospective study design and small sample size.

This study was limited to patients who were considered high risk for severe COVID-19, and the data collected for this study were from single patient assessments and did not assess whether changes in dyspnoea correlate with changes in SpO2 over time.

Introduction

As of 19 January 2021, there have been more than 93 million laboratory-confirmed novel COVID-19 cases and 2 million deaths documented globally.1 The spectrum of disease of COVID-19 ranges from asymptomatic or mild symptoms, to severe respiratory failure and death.2 Approximately 20% of patients with COVID-19 experience dyspnoea, which is more commonly associated with severe disease.3 Fatal cases of COVID-19 have higher rates of dyspnoea, lower blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) and greater rates of complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome.4 5

In an effort to reduce avoidable hospitalisations, healthcare contacts and transmission, most patients with COVID-19 can be managed in the community using virtual healthcare platforms, and transferred to hospital only if they develop progressive respiratory disease.6 Subjective dyspnoea can be assessed remotely using patient interview, and augmented by surrogate measures such as the Roth score7 and modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea Scale.8 However, the accuracy of these measures has not been formally evaluated in the context of COVID-19.6 7 Of great concern is the risk of false reassurance if patients develop hypoxaemia without the subjective sensation of dyspnoea. ‘Silent hypoxaemia’, or low SpO2 in the absence of dyspnoea, has been reported in the setting of COVID-19 and clinicians have speculated that it may be associated with increased out-of-hospital mortality9; case reports have described patients presenting to hospital with rapid deterioration and respiratory failure without signs of respiratory distress.10–12

Previous studies of the utility of dyspnoea measurement in diagnosing hypoxaemia in other respiratory conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure and lung cancer have yielded conflicting results.13–16 The association has not been studied during the COVID-19 pandemic despite the highly publicised concept of ‘silent hypoxaemia’. Therefore, we sought to determine the diagnostic accuracy of subjective dyspnoea measures in diagnosing hypoxaemia among a cohort of outpatients with COVID-19.

Methods

Study participants

All consecutive patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 followed as outpatients by the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre COVID-19 Expansion to Outpatients (COVIDEO) virtual care service from 3 April 2020 to 13 September 2020 were included in this retrospective cohort study. The patients were diagnosed based on a positive mid-turbinate or nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19 RNA detected by real-time PCR. COVIDEO is a virtual care model for monitoring of outpatients with COVID-19 at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, and is the basis of similar programmes at other hospitals.17 Patients were contacted by an infectious diseases physician for assessment and monitoring either by telephone or through the Ontario Telemedicine Network virtual platform.

A portable pulse oximeter was delivered to the homes of high-risk patients as defined by age >60 years, pregnancy, extensive comorbidities or presence of cardiorespiratory symptoms, such as chest pain or dyspnoea. The requirement for informed consent was waived.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Data collection

The demographic characteristics, clinical data, measures of subjective dyspnoea (presence of shortness of breath, mMRC dyspnoea scale score, Roth score), physical examination findings and SpO2 readings for study participants were collected from electronic medical records by one investigator (either AZ or SM). For the analysis, values were obtained from the patient’s initial virtual care assessment with a pulse oximeter, and subjective dyspnoea measures were taken at the same time as the objective measure of hypoxia.

Predictor variables

The primary predictor of interest was patient-reported presence of dyspnoea. Secondary predictor variables were patient-reported breathing faster at rest, breathing harder than normal, feeling more breathless today than yesterday, as well as dyspnoea as measured by the mMRC dyspnoea scale and the Roth score.

The mMRC dyspnoea scale has been studied extensively in a variety of respiratory conditions.8 It is composed of five categories that describe the degree of activity limitation due to worsening breathlessness. The participant assigns themselves a score ranging from 0 to 4 based on their perception of which activities result in dyspnoea, with higher scores indicating a greater impairment in their ability to perform daily activities.

The Roth score is a tool for quantifying the severity of dyspnoea, in which the patient is asked to count audibly to 30 in their native language, and the maximal count and counting time are recorded. A prior validation study demonstrated a strong positive correlation between pulse oximetry measurement and both counting time (r=0.59; p<0.001) and maximal count (r=0.67; p<0.001) achieved in one breath.7

Outcomes

The reference measure was SpO2 as measured by a ChoiceMMed pulse oximeter (model MD300C20). In the primary outcome definition, hypoxaemia was considered to be present if SpO2 was <95% in order to provide sufficient power to estimate the diagnostic test characteristics. Secondary outcomes included hypoxaemia cut-offs varying from 92% to 97%. Patients received instructions on correct pulse oximeter use and were told to wait 5–10 s for readings to calibrate prior to recording the SpO2 measurements.

Statistical analysis

In the primary analysis, the subjective dyspnoea measures were treated as diagnostic tests, and the specificity (SP), sensitivity (SN), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive likelihood ratio (+LR) and negative LR (−LR) were determined in order to evaluate the predictive value in detecting hypoxaemia. For the continuous predictors, the test characteristics were provided across a range of different score thresholds.

Diagnostic test characteristics of the primary dyspnoea measure were also determined in subgroups stratified based on patient characteristics, including (1) age <60 vs >60 years, (2) presence versus absence of underlying lung disease, and date from symptom onset (<7 vs >7 days). The Wilson method with continuity correction was used to calculate 95% CIs in order to avoid a negative lower limit.

A secondary analysis examined the strength of association between the presence of dyspnoea and hypoxaemia with a χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test (for sample sizes <5) with dyspnoea treated as a binary variable (present or absent). This relationship is represented by a violin plot. In additional analyses, a correlation coefficient was calculated to assess whether there was an association between the participants’ Roth scores and their SpO2 measurements. These associations were displayed graphically with a scatter plot (online supplemental figures 1 and 2). The relationship between the mMRC dyspnoea scale and hypoxaemia was analysed with a χ2 test and represented by violin plot.

bmjopen-2020-046282supp001.pdf (37.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-046282supp002.pdf (36.5KB, pdf)

All analyses were conducted in SAS Statistical Software V.9.3. For all statistical analyses, p<0.05 was considered significant.

Sample size calculation

The primary test characteristic of interest was the SN of dyspnoea as a test for hypoxaemia. The sample size was estimated based on a test of single proportion, namely SN. It was estimated that 62 patients would be required in order to estimate SN with a 10% margin of error and 95% CI if the true SN was 80%.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of outpatients with COVID-19

From 3 April to 13 September 2020, a total of 501 patients with COVID-19 were followed by COVIDEO. Of these patients, 89 (17.8%) met criteria for home SpO2 monitoring (age >60 years, pregnancy, extensive comorbidities or presence of cardiorespiratory symptoms). One patient was lost to follow-up after provision of the oxygen monitoring device.

Overall, the median age of patients was 52 years (IQR 38–64 years) and 57 patients (64%) were female (table 1). The median number of days from symptom onset to clinical assessment was 6 (IQR 3–8). Among these patients, the most common comorbidities were hypertension (36%), obesity (20%), diabetes (17%), asthma (16%) and malignancy (16%). Twenty-nine patients (33%) had no comorbidities. The most common symptoms reported on intake assessment were fatigue/malaise (66%), cough (63%) and myalgias (45%). While the patients were being followed by COVIDEO, 11 (12%) required hospitalisation, with a median duration of hospitalisation of 3 days (IQR 2.5–7). Five (6%) patients were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), and the median length of ICU stay was 6 days (IQR 2–11). One patient was intubated, and no patients died within 30 days of their COVID-19 diagnosis.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics among outpatients with COVID-19 monitored with home oxygen saturation devices

| Demographic information | No (%) |

| Total no | 89 |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 52 (38–64) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 57(64) |

| Male | 32 (36) |

| Pregnant | 6 (7) |

| Days from symptom onset to clinical assessment, median (IQR) | 6 (3–8) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Cardiac disease | 7 (8) |

| Chronic lung disease | 3 (3) |

| Asthma | 14 (16) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 7 (8) |

| Moderate/severe liver disease | 2 (2) |

| Chronic neurological issues | 5 (6) |

| Malignancy | 14 (16) |

| Chronic haematological disease | 7 (8) |

| Diabetes | 15 (17) |

| Hypertension | 32 (36) |

| Rheumatic disorder | 3 (3) |

| Malnutrition | 1 (1) |

| Obesity | 18 (20) |

| None | 29 (33) |

| Signs and symptoms on intake assessment | |

| Fever | 35 (39) |

| Sore throat | 28 (31) |

| Runny nose | 29 (33) |

| Cough | 56 (63) |

| Shortness of breath | 23 (26) |

| Chills/rigours | 30 (34) |

| Conjunctivitis | 10 (11) |

| Ear pain | 7 (8) |

| Anosmia | 21 (24) |

| Dysgeusia | 25 (28) |

| Sputum | 10 (11) |

| Hemoptysis | 0 |

| Wheezing | 7 (8) |

| Chest pain | 19 (21) |

| Myalgia | 40 (45) |

| Arthralgia | 16 (18) |

| Abdominal pain | 14 (16) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 22 (25) |

| Diarrhoea | 25 (28) |

| Adenopathy | 0 |

| Rash | 1 (1) |

| Fatigue/malaise | 59 (66) |

| Headache | 37 (42) |

| Confusion | 5 (6) |

| Depression/anxiety | 15 (17) |

| Insomnia | 19 (21) |

| Anorexia | 33 (37) |

| Laboratory findings at admission, median (IQR) | |

| Leukocytes, x109/L (n=21) | 5.9 (4.2–7.5) |

| Lymphocytes, x109/L (n=21) | 1.1 (0.6–1.3) |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase, IU/L (n=4) | 216.0 (63.4–277.0) |

| D-dimer, mcg/L (n=5) | 906.0 (555.0–1082.5) |

| High-sensitivity Troponin T ng/L (n=11) | 9.7 (6.0–10.0) |

| Ferritin, mcg/L (n=3) | 1644.0 (153.5–2082.5) |

| Chest radiography done | 29 (33) |

| Abnormal | 23 (26) |

| Bilateral infiltrates | 18 (20) |

| Outcome | |

| ICU admission | 5 (6) |

| Length of ICU stay, median (IQR), days | 6 (2–11) |

| Intubation | 1 (1) |

| Duration of intubation, days | 15 (17) |

| Hospitalisation | 11 (12) |

| Duration of hospitalisation, median (IQR), days | 3 (2.5–7) |

| Multiple hospitalisations | 2 (2) |

| Death (within 30 days of diagnosis) | 0 |

ICU, intensive care unit.

Association of Dyspnoea measurements with detection of hypoxaemia

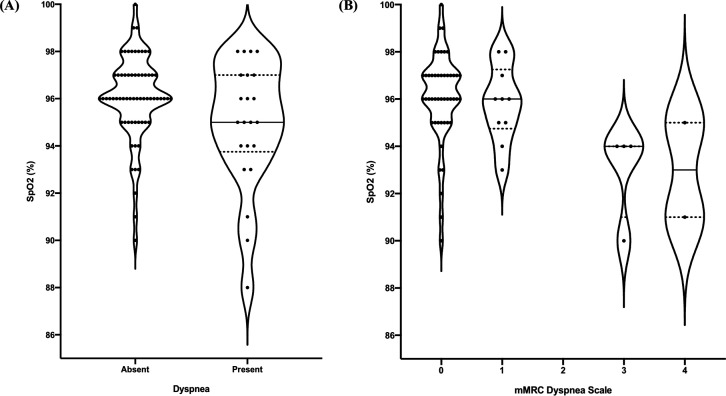

A total of 17 (19.1%) patients were diagnosed with hypoxaemia. hypoxaemia was significantly associated with the presence of dyspnoea (p=0.046), mMRC dyspnoea scale score over 0 (p=0.014), over 1 (p=0.001) and over 2 (p=0.001) (table 2). Weak associations were identified between patients’ Roth scores and their SpO2 measurements for maximum count (r=0.29; p=0.23) and counting time (r=0.12; p=0.617), respectively. The distribution of SpO2 (%) values in COVID-19 outpatients who reported dyspnoea and with various mMRC dyspnoea scale scores is shown in figure 1.

Table 2.

Association of dyspnoea measurements with detection of hypoxaemia

| Dyspnoea measurement | Non-hypoxic patients (O2 sat >95%) | Hypoxic patients (O2 sat <95%) | P value |

| Shortness of breath | 14 | 8 | 0.046* |

| Breathing faster at rest | 3 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Breathing harder than normal | 2 | 0 | 1.00 |

| More breathless today than yesterday | 3 | 1 | 0.57 |

| mMRC dyspnoea scale | |||

| >0 | 9 | 7 | 0.014* |

| >1 | 1 | 5 | 0.001* |

| >2 | 1 | 5 | 0.001* |

| >3 | 1 | 1 | 0.37 |

| Roth Score: maximum count | |||

| <12 | 0 | 1 | 0.21 |

| <15 | 3 | 2 | 0.27 |

| <20 | 5 | 2 | 0.60 |

| <28 | 6 | 2 | 1.00 |

| Roth Score: count time | |||

| <8 s | 1 | 1 | 0.39 |

| <15 s | 10 | 2 | 0.60 |

| <20 s | 12 | 2 | 0.27 |

| <25 s | 13 | 3 | 0.53 |

*The significance level is 0.05.

mMRC, modified Medical Research Council.

Figure 1.

Comparison of SpO2 and measures of subjective dyspnoea. (A) Violin plots showing the distribution of SpO2 (%) values in COVID-19 outpatients who reported dyspnoea and those who did not. (B) Violin plots showing the distribution of SpO2 (%) values in COVID-19 outpatients with various mMRC dyspnoea scale scores. The width of each plot is proportional to the number of patients with the respective SpO2 (represented by black dots). The median SpO2 is indicated by the central horizontal black line and the dotted lines correspond to the IQR. mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; SpO2, oxygen saturation.

Diagnostic accuracy of dyspnoea measurements in the detection of hypoxaemia

The presence or absence of subjective dyspnoea had an SN 47% (95% CI 24% to 72%), SP 80% (95% CI 68% to 88%), NPV 86% (95% CI 75% to 93%), PPV 36% (95% CI 18% to 59%), +LR 2.4 (95% CI 1.2 to 4.7), −LR 0.7 (95% CI 0.4 to 1.1) for diagnosing hypoxaemia (table 3). The presence of subjective dyspnoea had lower SN (25% (95% CI 16% to 37%]), 27% (95% CI 17% to 41%], 40% (95% CI 23% to 59%) for detecting hypoxaemia as defined by thresholds of <97%,<96% and <95%, respectively. At a lower SpO2 threshold of <92%, the SN increased only slightly to 50% (95% CI 19% to 81%). The other binary measures of subjective dyspnoea, including breathing faster at rest, breathing harder than normal, and feeling more breathless than the day before had lower SN (0% (95% CI 0% to 24%], 0% (95% CI 0% to 24%) and 6.2% (95% CI 0.3% to 32%), respectively), and higher SP (96% (95% CI 87% to 99%], 97% (95% CI 89% to 100%) and 96% (95% CI 87% to 99%), respectively) (table 3).

Table 3.

Diagnostic accuracy of dyspnoea measurements in the detection of hypoxaemia: estimation of test characteristics including sensitivity (SN), specificity (SP), negative (NPV) and positive (PPV) predictive value and negative (−LR) and positive (+LR)

| Dyspnoea measurement | SpO2 cut-off | SN % (95% CI) | SP % (95% CI) | NPV % (95% CI) | PPV % (95% CI) | To LR (95% CI) | +LR (95% CI) |

| Shortness of breath | <97% | 25 (16 to 37) | 75 (47 to 92) | 19 (10 to 30) | 82 (59 to 94) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.6) |

| <96% | 27 (17 to 41) | 78 (60 to 90) | 39 (27 to 51) | 68 (45 to 85) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) | 1.3 (0.6 to 2.7) | |

| <95% | 40 (23 to 59) | 83 (70 to 91) | 72 (60 to 82) | 55 (33 to 75) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | 2.3 (1.1 to 4.7) | |

| <94% | 47 (24 to 72) | 80 (68 to 88) | 86 (75 to 93) | 36 (18 to 59) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.1) | 2.4 (1.2 to 4.7) | |

| <93% | 46 (18 to 75) | 78 (66 to 86) | 91 (80 to 96) | 23 (9 to 46) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) | 2.0 (0.9 to 4.4) | |

| <92% | 50 (19 to 81) | 77 (66 to 85) | 95 (86 to 99) | 14 (4 to 36) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.5) | 2.1 (0.9 to 5.2) | |

| Breathing faster at rest | <94% | 0 (0 to 24) | 96 (87 to 99) | 81 (70 to 88) | 0 (0 to 69) | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.1) | 0 |

| Breathing harder than normal | <94% | 0 (0 to 24) | 97 (89 to 100) | 81 (71 to 88) | 0 (0 to 80) | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.1) | 0 |

| More breathless today than yesterday | <94% | 6.2 (0.3 to 32) | 96 (87 to 99) | 82 (71 to 89) | 25 (1 to 78) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.5 (0.2 to 13.1) |

| mMRC dyspnoea scale: | |||||||

| >0 | <94% | 54 (26 to 80) | 82 (68 to 91) | 87 (74 to 95) | 44 (21 to 69) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.0) | 3.0 (1.4 to 6.5) |

| >1 | <94% | 39 (15 to 68) | 98 (88 to 100) | 86 (74 to 93) | 83 (37 to 99) | 0.6 (0.4 to 1.0) | 19.2 (2.4 to 151) |

| >2 | <94% | 39 (15 to 68) | 98 (88 to 100) | 86 (74 to 93) | 83 (37 to 99) | 0.6 (0.4 to 1.0) | 19.2 (2.4 to 151) |

| >3 | <94% | 8 (0.4 to 38) | 98 (88 to 100) | 80 (68 to 89) | 50 (9.5 to 91) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 3.9 (0.3 to 57.4) |

| Roth Score: maximum count | |||||||

| <12 | <94% | 25 (1.3 to 78) | 100 (75 to 100) | 83 (58 to 96) | 100 (6 to 100) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.3) | N/A |

| <15 | <94% | 50 (15 to 85) | 80 (51 to 95) | 86 (56 to 98) | 40 (7 to 83) | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.7) | 2.5 (0.6 to 10.2) |

| <20 | <94% | 50 (15 to 85) | 67 (39 to 87) | 83 (51 to 97) | 29 (5.1 to 70) | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.1) | 1.5 (0.5 to 5.1) |

| <28 | <94% | 7.7 (0.4 to 38) | 94 (82 to 98) | 79 (66 to 88) | 25 (1.3 to 78) | 1.0 (0.3 to 2.4) | 1.3 (0.4 to 4.0) |

| Roth Score: count time | |||||||

| <8 s | <94% | 25 (1.3 to 78) | 93 (66 to 100) | 82 (56 to 95) | 50 (10 to 91) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.4) | 3.8 (0.3 to 47.7) |

| <15 s | <94% | 50 (15 to 85) | 33 (13 to 61) | 71 (30 to 95) | 17 (2.9 to 49) | 1.5 (0.5 to 5.1) | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.1) |

| <20 s | <94% | 50 (15 to 85) | 20 (5.3 to 49) | 60 (17 to 93) | 14 (2.5 to 44) | 2.5 (0.6 to 10.2) | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.7) |

| <25 s | <94% | 75 (22 to 99) | 13 (2.3 to 42) | 67 (13 to 98) | 19 (5.0 to 46) | 1.9 (0.2 to 15.8) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.6) |

| All predictors combined* | <94% | 59 (34 to 81) | 67 (55 to 78) | 87 (75 to 94) | 30 (16 to 49) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.1) | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.0) |

*This represents a single variable in which all of the measurements were combined into a single predictor: dyspnoea or breathing faster or breathing harder or more breathless or mMRC >0 or Roth mximum count <20 or Roth count time <20.

+LR/−LR, positive/negative likelihood ratios; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; SpO2, oxygen saturation.

mMRC dyspnoea scale scores were recorded and available for 63 patients (70.8%). An mMRC dyspnoea scale score of greater than 0 was determined to have an SN of 54% (95% CI 26% to 80%), SP 82% (95% CI 68% to 91%), NPV 87% (95% CI 74% to 95%), PPV 44% (95% CI 21% to 69%), −LR 0.6 (95% CI 0.3 to 1.0) and +LR 3.0 (95% CI 1.4 to 6.5) for the detection of hypoxaemia. At higher cut-off values, the SN of the mMRC dyspnoea scale was reduced to 39% (95% CI 15% to 68%) for scores greater than 1 and 2% and 8% (95% CI 0.4% to 38%) for scores greater than 3. The SP for mMRC dyspnoea scale scores greater than 1, 2 and 3 at capturing hypoxaemia was 98% (95% CI 88% to 100%).

Roth scores were available for 19 patients (29.7%). The Roth score had a higher SN at higher cut-off values for counting time. A maximum count of less than 12 had an SN of 25% (95% CI 1.3% to 78%), SP 100% (95% CI 75% to 100%), NPV 83% (95% CI 58% to 96%), PPV 100% (95% CI 6% to 100%) and a −LR of 0.75 (95% CI 0.4 to 1.3).

The diagnostic test with the highest SN for diagnosing hypoxaemia was a Roth score maximum counting time of less than 25 s, which still had an SN of only 75% (95% CI 22% to 99%), and inadequate SP 13% (95% CI 2.3% to 42%), NPV 67% (95% CI 13% to 98%), PPV 19% (95% CI 5.0% to 46%), −LR 1.88 (95% CI 0.2 to 16) and +LR 0.87 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.6). When all subjective dyspnoea predictors are combined in a single variable, the SN is 59% (95% CI 34% to 81%), SP 67% (95% CI 55% to 78%), NPV 87% (95% CI 75% to 94%), PPV 30% (95% CI 16% to 49%), −LR 0.6 (95% CI 0.3 to 1.1) and +LR 1.8 (95% CI 1.0 to 3.0).

The diagnostic accuracy of dyspnoea presence in the detection of hypoxaemia was most impacted when stratified by the presence of underlying lung disease. In the patients with underlying lung disease, the SN and SP of the presence of dyspnoea in detecting hypoxaemia was 100% (95% CI 20%– to 100%) and 80% (95% CI 51%– to 95%), respectively. A lower SN (22% (95% CI 3.9% to 60%)) and high SP (96% (95% CI 79% to 100%)) was observed for patients over 60 years when results were stratified based on age. Stratifying based on days from symptom onset did not impact the diagnostic accuracy of dyspnoea in detecting hypoxaemia (table 4).

Table 4.

Diagnostic accuracy of the presence of dyspnoea in the detection of hypoxaemia stratified based on patient characteristics, including age, presence versus absence of underlying lung disease and date from symptom onset

| SN % (95% CI) |

SP % (95% CI) |

NPV % (95% CI) |

PPV % (95% CI) |

-LR (95% CI) |

+LR (95% CI) |

|

| Age | ||||||

| <60 years | 75 (36 to 96) | 70 (54 to 83) | 94 (78 to 99) | 32 (14 to 57) | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.2) | 2.5 (1.3 to 4.5) |

| >60 years | 22 (3.9 to 60) | 96 (79 to 100) | 79 (61 to 90) | 67 (13 to 98) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.2) | 6.0 (0.6 to 58.6) |

| Underlying lung disease | ||||||

| Yes | 100 (20 to 100) | 80 (51 to 95) | 100 (70 to 100) | 40 (7.3 to 83) | 0 | 5.0 (1.8 to 13.8) |

| No | 40 (18 to 67) | 80 (67 to 89) | 83 (70 to 92) | 35 (15 to 61) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | 2.0 (0.9 to 4.5) |

| Days from symptom onset | ||||||

| <7 days | 50 (19 to 81) | 83 (68 to 93) | 92 (78 to 98) | 30 (8.1 to 65) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.4) | 3.0 (1.1 to 8.6) |

| >7 days | 50 (24 to 76) | 71 (48 to 88) | 75 (51 to 90) | 46 (18 to 75) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.4) | 1.8 (0.7 to 4.4) |

+LR/−LR, positive/negative likelihood ratios; NPV/PPV, negative/positive predictive value; SN, sensitivity negative; SP, specificity negative.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of subjective dyspnoea in detecting hypoxaemia in the setting of COVID-19. Self-reported shortness of breath has very limited utility for detecting hypoxaemia, with an SN of only 47% and SP of only 80% for detecting SpO2 levels below 95%. Using a lower SpO2 threshold of less than 93% did not meaningfully improve the SN of subjective dyspnoea in diagnosing hypoxaemia (SN 50%). Other binary measures of subjective dyspnoea, including breathing faster at rest, breathing harder than normal and feeling more breathless than yesterday offered high SP. Similarly, an mMRC dyspnoea score exceeding 1, a Roth maximal count less than 12 and Roth counting time under 8 s offered high SP and +LR to rule in hypoxaemia. Identifying patients with these features may be helpful in the remote assessment of COVID-19 outpatients. However, none of these measures offered sufficient SN or –LR to help rule out hypoxaemia—which is the more clinically important consideration for these patients. Even when all variables were combined into a single maximally sensitive predictor, the SN was just 59%.

Previous studies examining the correlation between subjective dyspnoea and hypoxaemia in other respiratory conditions have yielded inconsistent findings. The strongest confirmation of the potential diagnostic utility of dyspnoea emerged from a study of 76 patients admitted to the emergency department with acute exacerbations of COPD, in which dyspnoea scores exceeding 3 or 4 on a five-stage scoring system were found to have a sensitivity of 93.5% for detecting hypoxaemia.14 Additionally, the mMRC dyspnoea scale has been found to be significantly correlated with SpO2 in measurements obtained during exercise among patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.18 Conversely, several other studies have shown no correlation between perceived dyspnoea and hypoxaemia in conditions such as advanced lung cancer, COPD and palliative care patients.15 16 19 While previous studies show variable relationships between dyspnoea and hypoxaemia in various respiratory pathologies, our study shows that neither binary measures of subjective dyspnoea, the mMRC dyspnoea scale, or the Roth score can be used to rule out hypoxaemia in the setting of COVID-19.

Discrepancies between respiratory rate and SpO2 in COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory failure have been highlighted previously, suggesting that a normal respiratory rate may belie profound hypoxaemia in this setting.20 High levels of anxiety may contribute to feelings of dyspnoea in patients who are non-hypoxaemic. There are also a growing number of case reports documenting silent hypoxaemia among COVID-19 patients, where patients present with hypoxaemia in the absence of respiratory symptoms.10 11 21 The underlying mechanism responsible for severe hypoxaemia in the absence of dyspnoea is not well elucidated. It has been postulated that this clinical picture may be consistent with a phenotype of COVID-19 pneumonia (L-phenotype) characterised by low elastance, low ventilation-perfusion ratio and near normal compliance.12 The relatively high compliance results in preserved gas volumes, while hypoxaemia may result due to a ventilation–perfusion mismatch caused by impaired lung perfusion regulation and loss of hypoxic vasoconstriction.22 23 Additionally, the absence of dyspnoea despite severe hypoxaemia may reflect pulmonary vaso-occlusive disease, whereby patients develop clinically silent microvascular thrombi in early stages of the disease, which if left untreated, results in worsening hypercoagulability and rapid clinical deterioration due to a thromboinflammatory cascade.24 25 While at this point the exact mechanism remains speculative, our data suggest that the discrepancy between dyspnoea and hypoxaemia makes it difficult to accurately assess patients remotely and emphasises the importance of SpO2 monitoring in order to avoid missing patients with developing respiratory failure.

This study has several limitations. The data collected for this study were from patients’ initial pulse oximeter assessment and did not assess whether changes in dyspnoea correlate with changes in SpO2 over time. This is a potentially important notion when monitoring patients who are (or are not) becoming increasingly dyspneic while self-isolating in their homes. While the number of patients included was sufficient for the primary analysis, they were insufficient for precise estimates of subgroups stratified by age, presence of lung disease, date of symptom onset and for calculation of the diagnostic test characteristics at lower SpO2 cutoffs. In our study, less than 20% of included patients were diagnosed with hypoxaemia. While this represents a small sample of patients with hypoxaemia, it is clear that in order to prevent missing any patients with hypoxaemia who require admission all high risk patients require SpO2 monitoring.

Additionally, our study was limited to patients who were considered at high risk of severe disease, and it is possible that the diagnostic test characteristics might differ in younger and healthier patients. Lastly, pulse oximeters may have variable accuracy as individuals become increasingly hypoxic and are further impacted by individual patient characteristics; however, a perfect reference standard of invasive blood oxygen measurement would be neither practical nor ethical in the outpatient setting.26

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that subjective dyspnoea does not accurately capture hypoxaemia in patients with COVID-19. Although some dyspnoea scores have high specificity and +LR for identifying hypoxaemia, none of these measures have sufficient sensitivity to rule out hypoxaemia. Therefore, relying on surrogate measures of dyspnoea alone is not sufficient to remotely monitor high-risk outpatients with COVID-19. Home SpO2 monitoring should be a mandatory component of remote management all high-risk outpatients with COVID-19.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The authors all stand behind the conclusions of this manuscript, agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, and support its publication. LB contributed to the planning, conception and study design, data analysis, interpretation of the data, and reporting of the work. AZ contributed to data analysis, interpretation of the data, and reporting of the work. NA contributed to the planning, conception, study design, study conduct, data acquisition and reporting of the work. AKC contributed to the planning, conception, study design, study conduct, data acquisition and reporting of the work. JE-C contributed to data analysis, interpretation of the data and reporting of the work. AG contributed to the interpretation of the data and reporting of the work. PWL contributed to the planning, conception, study design, study conduct, data acquisition and reporting of the work. JAL contributed to the planning, conception, study design, study conduct, data acquisition and reporting of the work. SMP contributed to the planning, conception, study design, study conduct, data acquisition and reporting of the work. SM contributed to the planning, conception, study design, study conduct, data acquisition and reporting of the work. AES contributed to the planning, conception, study design, study conduct, data acquisition and reporting of the work. ND contributed to the planning, conception, and study design, study conduct, data acquisition, data analysis, interpretation of the data and reporting of the work. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation and have given approval for its submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the institutional review board at Sunnybrook Health Sciences as minimal risk research, using data collected for routine clinical practice.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. Deidentified data are available on reasonable request.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Weekly epidemiological update, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update---19-january-2021

- 2.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA 2020;323:1239–42. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan W-J, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1708–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng Y, Liu W, Liu K, Yan D, Wei L, Kui L, et al. Clinical characteristics of fatal and recovered cases of coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective study. Chin Med J 2020;133:1261-1267. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ 2020;368:m1091. 10.1136/bmj.m1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenhalgh T, Koh GCH, Car J. Covid-19: a remote assessment in primary care. BMJ 2020;368:m1182. 10.1136/bmj.m1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chorin E, Padegimas A, Havakuk O, et al. Assessment of respiratory distress by the Roth score. Clin Cardiol 2016;39:636–9. 10.1002/clc.22586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fletcher CM. Standardised questionnaire on respiratory symptoms: a statement prepared and Approved by the MRC Committee on the aetiology of chronic bronchitis (MRC breathlessness score). BMJ 1960;2:1665.13688719 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman J, Calderón-Villarreal A, Bojorquez I. Excess out-of-hospital mortality and declining oxygen saturation documented by EMS during the COVID-19 crisis in Tijuana, Mexico. medRxiv 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ottestad W, Seim M, Maehlen JO. Covid-19 with silent hypoxemia. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2020. https://tidsskriftet.no/en/2020/04/kort-kasuistikk/covid-19-silent-hypoxemia 10.4045/tidsskr.20.0299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkerson RG, Adler JD, Shah NG, et al. Silent hypoxia: a harbinger of clinical deterioration in patients with COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med 2020;38:2243.e5–2243.e6. 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.05.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P, et al. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med 2020;46:1099–102. 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gondos T, Szabó V, Sárkány Ágnes, et al. Estimation of the severity of breathlessness in the emergency department: a dyspnea score. BMC Emerg Med 2016;17:13. 10.1186/s12873-017-0125-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Güryay MS, Ceylan E, Günay T, et al. Can spirometry, pulse oximetry and dyspnea scoring reflect respiratory failure in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation? Med Princ Pract 2007;16:378–83. 10.1159/000104812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higashimoto Y, Honda N, Yamagata T, et al. Exertional dyspnoea and cortical oxygenation in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2015;46:1615–24. 10.1183/13993003.00541-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka K, Akechi T, Okuyama T, et al. Factors correlated with dyspnea in advanced lung cancer patients: organic causes and what else? J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;23:490–500. 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00400-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lam PW, Sehgal P, Andany N, et al. A virtual care program for outpatients diagnosed with COVID-19: a feasibility study. CMAJ Open 2020;8:E407–13. 10.9778/cmajo.20200069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manali ED, Lyberopoulos P, Triantafillidou C, et al. Mrc chronic dyspnea scale: relationships with cardiopulmonary exercise testing and 6-minute walk test in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients: a prospective study. BMC Pulm Med 2010;10:32. 10.1186/1471-2466-10-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clemens KE, Quednau I, Klaschik E. Use of oxygen and opioids in the palliation of dyspnoea in hypoxic and non-hypoxic palliative care patients: a prospective study. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:367–77. 10.1007/s00520-008-0479-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jouffroy R, Jost D, Prunet B. Prehospital pulse oximetry: a red flag for early detection of silent hypoxemia in COVID-19 patients. Crit Care 2020;24:313. 10.1186/s13054-020-03036-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tobin MJ, Laghi F, Jubran A. Why COVID-19 silent hypoxemia is Baffling to physicians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;202:356–60. 10.1164/rccm.202006-2157CP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gattinoni L, Coppola S, Cressoni M, et al. COVID-19 Does Not Lead to a "Typical" Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;201:1299–300. 10.1164/rccm.202003-0817LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Rossi S. COVID-19 pneumonia: ARDS or not? Crit Care 2020;24:154. 10.1186/s13054-020-02880-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Low T-T, Cherian R, Lim SL, et al. Rethinking COVID-19 'pneumonia' - is this primarily a vaso-occlusive disease, and can early anticoagulation save the ventilator famine? Pulm Circ 2020;10:204589402093170–3. 10.1177/2045894020931702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Couzin-Frankel J. The mystery of the pandemic's 'happy hypoxia'. Science 2020;368:455–6. 10.1126/science.368.6490.455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luks AM, Swenson ER. Pulse oximetry for monitoring patients with COVID-19 at home. potential pitfalls and practical guidance. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2020;17:1040–6. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202005-418FR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-046282supp001.pdf (37.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-046282supp002.pdf (36.5KB, pdf)