Abstract

Objective

To summarize the colorectal cancer (CRC) burden and trend in the world, and compare the difference of CRC burden between other countries and China.

Methods

Incidence and mortality data were extracted from the GLOBOCAN2018 and Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. Age-specific incidence trend was conducted by Joinpoint analysis and average annual percent changes were calculated.

Results

About 1.85 million new cases and 0.88 million deaths were expected in 2018 worldwide, including 0.52 million (28.20%) new cases and 0.25 million (28.11%) deaths in China. Hungary had the highest age-standardized incidence and mortality rates in the world, while for China, the incidence and mortality rates were only half of that. CRC incidence and mortality were highly correlated with human development index (HDI). Unlike the rapid increase in Republic of Korea and the downward trend in Canada and Australia, the age-standardized incidence rates by world standard population in China and Norway were rising gradually. The age-specific incidence rate in the age group of 50−59 years in China was increasing rapidly, while in Republic of Korea and Canada, the fastest growing age group was 30−39 years.

Conclusions

The variations of CRC burden reflect the difference of risk factors, as well as levels of HDI and screening (early detection activities). The burden of CRC in China is high, and the incidence of CRC continues to increase, which may lead to a sustained increase in the burden of CRC in China in the future. Screening should be expanded to control CRC, and focused on young people in China.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, burden, China, trend

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the mainly prevalent malignant cancer in the world which is a collective term for colon cancer, rectal and anal cancer. Adenocarcinoma formed by glandular epithelial cells is the mainly pathological type of CRC (1,2). Although it is believed that CRC is mainly prevalent in developed countries, the incidence is also rising rapidly in countries undergoing economic development and changing lifestyles. The United States and other affluent countries are gradually reducing incidence and mortality through screening and improved treatment (3,4). However, the prevention and control measures in developing countries are still limited (5).

The etiology and trend changes of CRC are all related to economic and social factors, and many countries like China have experienced tremendous economic changes in just a few decades. Therefore, we try to figure out the differences between different economies by analyzing burden and trends of major countries worldwide. Comparing the current situation of China’s CRC burden in the world, we can clarify the possible problems in the next stage. This research provides scientific data support for the formulation of cancer prevention and control policies through the analysis of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) public database.

Materials and methods

Data sources

World CRC incidence and mortality data were extracted from GLOBOCAN2018 (6). The GLOBOCAN2018 systematically estimated the incidence and mortality in 185 countries or territories for 36 cancer major types in 2018. According to International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10), colon cancer, rectal and anal cancer coded as C18 and C19-21 were extracted for analysis. We used the same regional classification criteria as GLOBOCAN2018 dividing the world into 20 major regions. The human development index (HDI) was derived from the Human Development Report 2019 (7) released by the United Nations Development Programme. For trend analysis, data were extracted from Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (CI5) (8). According to the rank of age-standardized incidence rate by world standard population (ASIRW) in GLOBOCAN2018, countries with the highest incidence in each continent and China were selected for comparative analysis.

Statistical analysis

The ASIRW was used for trend analysis, grouped by sex and subsite in Canada, Republic of Korea, Uganda, Norway, Australia and China, because data from other countries are not available. The Joinpoint Regression Program (Version 4.3.1.0, National Cancer Institute) (8) was used to analyze the trend change of age-specific incidence in China, Republic of Korea and Canada, grouped by sex. Temporal trend was divided into three periods at most and trends were expressed as average annual percentage change (AAPC) (9-11). The Z test was used to analyze statistical differences.

Results

CRC incidence and mortality in 2018

Approximately there were 1.85 million new cases worldwide in 2018. The crude incidence rate was 24.2 per 100,000 and the ASIRW was 19.7 per 100,000. We selected countries with the highest ASIRW in each region for regional burden comparisons. Of the 20 regions in the world, countries in Europe generally had a high incidence rate. The ASIRW in four European countries had exceeded 35 per 100,000, and the crude incidence rate in Hungary had even exceeded 100 per 100,000. However, the incidence rate of CRC was generally low in African countries and varied greatly in Asia, America and Oceania. China had the largest cases, accounting for 28.20% of the world. The ASIRW and crude incidence of China were both in a medium to high level. The trend was basically the same in both sexes (Table 1 ).

1. Estimated incidence of CRC in the world’s major burden countries and China in 2018.

| Area | Population | Both | Male | Female | ||||||||

| New

cases |

Crude rate (1/105) | ASIRW (1/105) | New

cases |

Crude rate (1/105) | ASIRW (1/105) | New

cases |

Crude rate (1/105) | ASIRW (1/105) | ||||

| CRC, colorectal cancer; ASIRW, age-standardized incidence rate by world standard population; a, Democratic Republic of Congo; b, Polynesia and Micronesia; c, Australia and New Zealand. | ||||||||||||

| World | 1,849,518 | 24.2 | 19.7 | 1,026,215 | 26.6 | 23.6 | 823,303 | 21.8 | 16.3 | |||

| China | 521,490 | 36.6 | 23.7 | 303,853 | 41.5 | 28.1 | 217,637 | 31.5 | 19.4 | |||

| Asia | ||||||||||||

| Eastern | Republic of Korea | 42,363 | 82.8 | 44.5 | 26,143 | 102.1 | 59.5 | 16,220 | 63.4 | 31.3 | ||

| South

Eastern |

Singapore | 4,202 | 72.5 | 36.8 | 1,994 | 69.7 | 38.9 | 2,208 | 75.4 | 34.0 | ||

| South

Central |

Kazakhstan | 3,049 | 16.6 | 15.4 | 1,392 | 15.6 | 17.7 | 1,657 | 17.5 | 14.1 | ||

| Western | Turkey | 20,031 | 24.5 | 21.0 | 11,548 | 28.6 | 27.4 | 8,483 | 20.4 | 16.0 | ||

| Europe | ||||||||||||

| Western | Netherlands | 14,921 | 87.3 | 37.8 | 8,513 | 100.1 | 45.3 | 6,408 | 74.7 | 31.1 | ||

| Northern | Norway | 4,887 | 91.3 | 42.9 | 2,530 | 93.6 | 46.9 | 2,357 | 88.9 | 39.3 | ||

| Eastern | Hungary | 10,809 | 111.6 | 51.2 | 6,115 | 132.6 | 70.6 | 4,694 | 92.4 | 36.8 | ||

| Southern | Slovenia | 1,987 | 95.5 | 41.1 | 1,301 | 125.8 | 58.9 | 686 | 65.5 | 25.5 | ||

| Americas | ||||||||||||

| Northern | Canada | 24,617 | 66.6 | 31.5 | 13,039 | 71.1 | 35.2 | 11,578 | 62.2 | 28.0 | ||

| Central | Costa Rica | 1,128 | 22.8 | 16.7 | 560 | 22.6 | 17.6 | 568 | 22.9 | 15.9 | ||

| Caribbean | Barbados | 219 | 76.5 | 38.9 | 118 | 86.1 | 50.3 | 101 | 67.6 | 28.8 | ||

| South | Uruguay | 2,273 | 65.5 | 35.0 | 1,152 | 68.7 | 43.8 | 1,121 | 62.5 | 28.3 | ||

| Africa | ||||||||||||

| Northern | Algeria | 5,537 | 13.2 | 13.9 | 2,910 | 13.7 | 14.8 | 2,627 | 12.6 | 13.0 | ||

| Eastern | Mauritius | 288 | 22.7 | 14.7 | 156 | 24.9 | 17.4 | 132 | 20.6 | 12.6 | ||

| Southern | South Africa | 6,937 | 12.1 | 14.4 | 3,508 | 12.5 | 18.1 | 3,429 | 11.7 | 12.0 | ||

| Middle | Congoa | 3,568 | 4.2 | 9.1 | 1,627 | 3.9 | 9.0 | 1,941 | 4.6 | 9.2 | ||

| Western | Mali | 917 | 4.8 | 10.5 | 385 | 4.0 | 9.0 | 532 | 5.6 | 11.7 | ||

| Oceania | ||||||||||||

| Melanesia | Papua New Guinea | 684 | 8.1 | 13.0 | 439 | 10.3 | 19.3 | 245 | 5.9 | 8.4 | ||

| Polynesiab | Samoa | 37 | 18.7 | 22.6 | 24 | 23.5 | 30.6 | 13 | 13.6 | 14.8 | ||

| Australiac | Australia | 17,782 | 71.8 | 36.9 | 9,643 | 78.1 | 41.9 | 8,139 | 65.5 | 32.4 | ||

There were 0.88 million deaths worldwide in 2018. The crude mortality rate was 11.5 per 100,000 and the age-standardized mortality rate by world standard population (ASMRW) was 8.9 per 100,000. Hungary’s crude mortality rate was 52.4 per 100,000, which was the highest in the world. The mortality rate of CRC was low in Africa and Oceania and varies greatly in Asia and America. China had the largest deaths in the world, accounting for 28.11%. The ASMRW and crude mortality rate of China were higher than the world level in both sexes (Table 2 ).

2. Estimated mortality of CRC in the world’s major burden countries and China in 2018.

| Area | Population | Both | Male | Female | ||||||||

| Deaths | Crude rate (1/105) | ASMRW (1/105) | Deaths | Crude rate (1/105) | ASMRW (1/105) | Deaths | Crude rate (1/105) | ASMRW (1/105) | ||||

| CRC, colorectal cancer; ASMRW, age-standardized mortality rate by world standard population; a, Democratic Republic of Congo; b, Polynesia and Micronesia; c, Australia and New Zealand; | ||||||||||||

| World | 880,792 | 11.5 | 8.9 | 484,224 | 12.6 | 10.8 | 396,568 | 10.5 | 7.2 | |||

| China | 247,563 | 17.4 | 10.9 | 142,476 | 19.4 | 13.1 | 105,087 | 15.2 | 8.8 | |||

| Asia | ||||||||||||

| Eastern | Republic of Korea | 9,762 | 19.1 | 8.7 | 5,445 | 21.3 | 11.8 | 4,317 | 16.9 | 6.3 | ||

| South Eastern | Singapore | 1,980 | 34.2 | 17.3 | 1,050 | 36.7 | 20.2 | 930 | 31.7 | 14.6 | ||

| South Central | Kazakhstan | 2,108 | 11.5 | 10.5 | 1,023 | 11.5 | 13.3 | 1,085 | 11.4 | 8.9 | ||

| Western | Turkey | 10,033 | 12.2 | 10.2 | 5,571 | 13.8 | 13.1 | 4,462 | 10.7 | 7.9 | ||

| Europe | ||||||||||||

| Western | Netherlands | 6,442 | 37.7 | 13.8 | 3,443 | 40.5 | 16.5 | 2,999 | 35.0 | 11.5 | ||

| Northern | Norway | 1,750 | 32.7 | 13.2 | 915 | 33.8 | 15.3 | 835 | 31.5 | 11.3 | ||

| Eastern | Hungary | 5,076 | 52.4 | 21.5 | 2,867 | 62.2 | 31.2 | 2,209 | 43.5 | 14.8 | ||

| Southern | Slovenia | 740 | 35.6 | 12.5 | 423 | 40.9 | 17.1 | 317 | 30.3 | 8.9 | ||

| Americas | ||||||||||||

| Northern | Canada | 9,494 | 25.7 | 10.1 | 5,086 | 27.7 | 12.2 | 4,408 | 23.7 | 8.2 | ||

| Central | Costa Rica | 617 | 12.5 | 8.6 | 316 | 12.8 | 9.5 | 301 | 12.2 | 7.7 | ||

| Caribbean | Barbados | 101 | 35.3 | 16.6 | 53 | 38.7 | 21.4 | 48 | 32.1 | 12.4 | ||

| South | Uruguay | 1,093 | 31.5 | 15.0 | 555 | 33.1 | 19.3 | 538 | 30.0 | 12.1 | ||

| Africa | ||||||||||||

| Northern | Algeria | 3,027 | 7.2 | 7.5 | 1,684 | 7.9 | 8.5 | 1,343 | 6.5 | 6.6 | ||

| Eastern | Mauritius | 173 | 13.6 | 8.6 | 92 | 14.7 | 10.3 | 81 | 12.6 | 7.1 | ||

| Southern | South Africa | 3,664 | 6.4 | 7.6 | 1,898 | 6.7 | 10.2 | 1,766 | 6.0 | 6.1 | ||

| Middle | Congoa | 2,831 | 3.4 | 7.4 | 1,314 | 3.1 | 7.5 | 1,517 | 3.6 | 7.3 | ||

| Western | Mali | 686 | 3.6 | 8.3 | 290 | 3.0 | 7.3 | 396 | 4.2 | 9.1 | ||

| Oceania | ||||||||||||

| Melanesia | Papua New Guinea | 447 | 5.3 | 8.7 | 307 | 7.2 | 14 | 140 | 3.4 | 4.8 | ||

| Polynesiab | Samoa | 13 | 6.6 | 7.8 | 8 | 7.8 | 10.9 | 5 | 5.2 | 6.3 | ||

| Australiac | Australia | 6,131 | 24.7 | 10.9 | 3,237 | 26.2 | 12.8 | 2,894 | 23.3 | 9.2 | ||

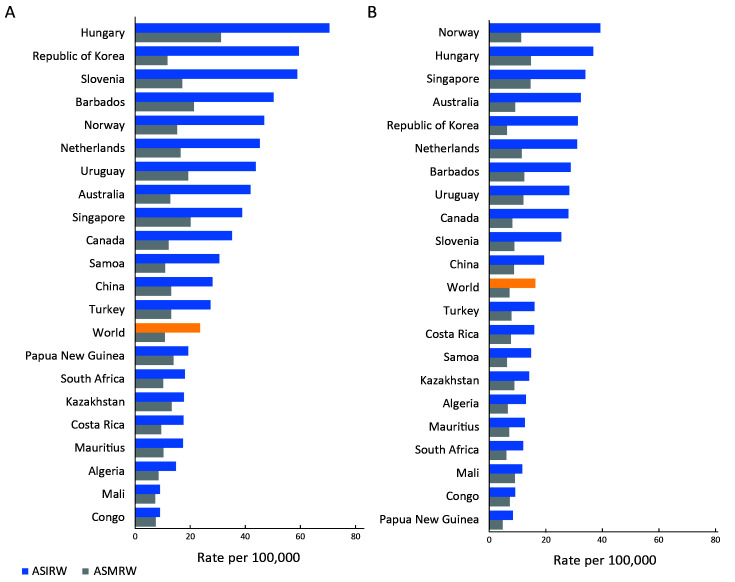

ASIRW of Hungary and Norway ranked first in males and females, respectively. Regardless of sex, European countries tended to rank higher while African countries ranked lower. China’s rate was just above the world level in both sexes. Hungary had a higher ASMRW among males, and there was little difference in ASMRW among females between countries. Republic of Korea had a high ASIRW but low ASMRW for both males and females (Figure 1 ).

1.

Rank of countries with major burden of CRC in (A) male and (B) female in 2018. CRC, colorectal cancer; ASIRW, age-standardized incidence rate by world standard population; ASMRW, age-standardized mortality rate by world standard population

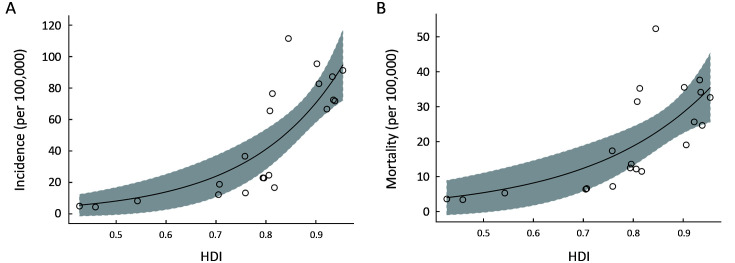

With the increase of the HDI, its incidence and mortality had increased rapidly. It was found that HDI had an exponential relationship with crude incidence and mortality rates. The correlation between incidence rate and HDI was stronger than correlation between mortality rate and HDI (Figure 2 ).

2.

Ecological correlation between a country’s HDI and CRC crude incidence rates (P<0.0001) (A) and mortality rates (P<0.0001) (B), respectively, in 2018. HDI, human development index; CRC, colorectal cancer.

Temporal trends in CRC incidence

Countries met the data quality and selection requirements were Canada (except Nunavut, Quebec and Yukon), Republic of Korea (5 registries), Uganda (Kampala), Norway and Australia. Their trend data from 2003 to 2012 were extracted for comparison with China (5 registries).

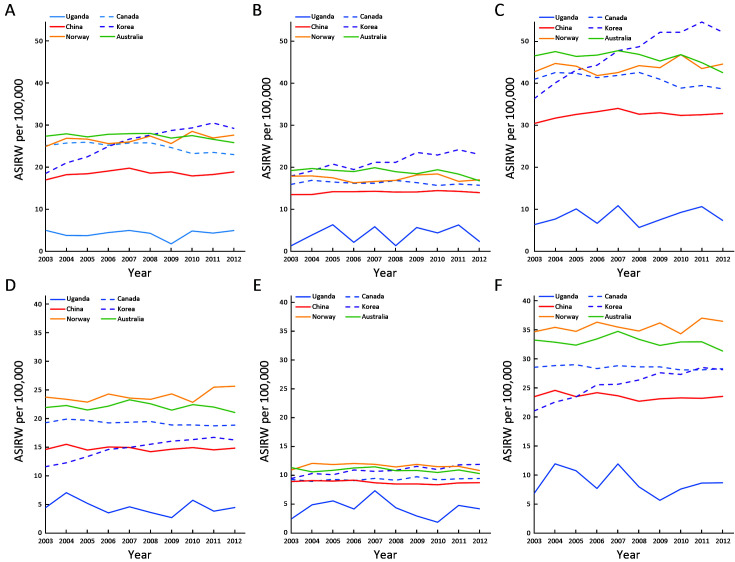

The trend in CRC for males showed that ASIRW in Republic of Korea had rapidly increased to the first, while Australia had gradually decreased from first to third. Canada had a slowly downward trend, while China and Norway had gradually upward trend. Although ASIRW of China had been rising, it was still the fifth in 2012. In males, the ASIRW of rectal cancer was lower than that of colon cancer, but the trend was basically the same. The trend change had become more obvious after combination of colon cancer and rectal cancer (Figure 3 ).

3.

Trend changes of ASIRW of CRC in China and major burden countries in five continents. (A) Male colon incidence; (B) Male rectum and anus incidence; (C) Male CRC incidence; (D) Female colon incidence; (E) Female rectum and anus incidence; (F) Female CRC incidence. ASIRW, age-standardized incidence rate by world standard population; CRC, colorectal cancer.

The trend in CRC for females showed that ASIRW in Norway was higher than that in other countries consistently. In Republic of Korea and Australia, the trend of change in females was not as obvious as that in males. In the trend analysis of rectal cancer, Republic of Korea showed an obvious upward trend. The trend of CRC was similar to that of colon cancer (Figure 3 ).

Age-specific incidence trend

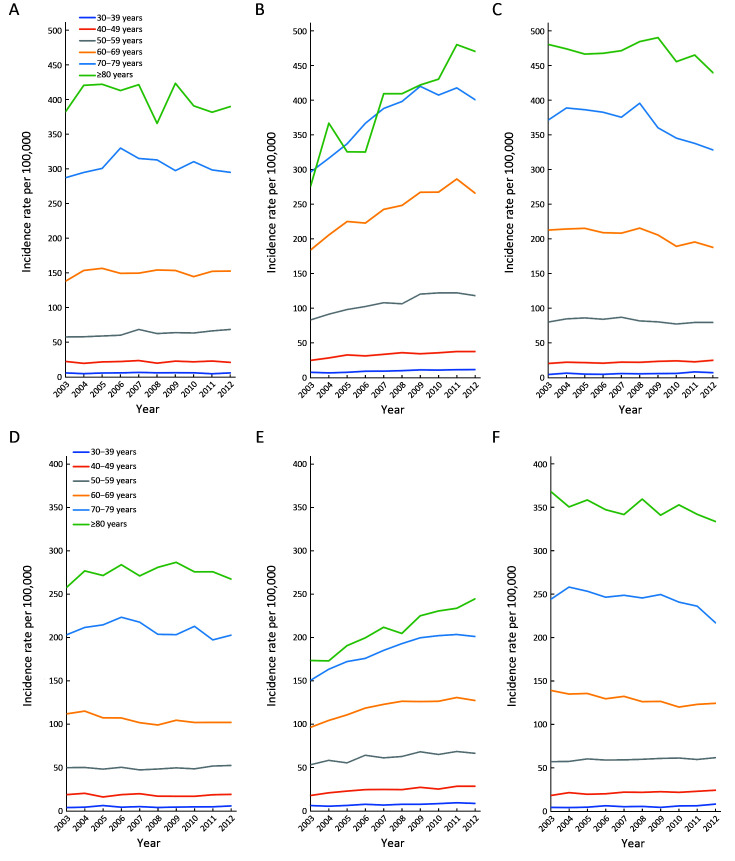

Trends for age-specific incidence rate were compared between Republic of Korea, Canada and China. Both males and females in the age group of 40−59 years in China had an upward trend. The upward trend in the Republic of Korea was more obvious than that in China, especially for males in the age group of 60−69 years. Although the incidence of Korean females was rising, the incidence rate of people over 60 years old was lower than that of China and Canada. However, the incidence rate in Canada had a downward trend in 2003−2012 (Figure 4 ).

4.

Age-specific incidence trends in CRC between Republic of Korea, Canada and China. (A) Males of China; (B) Males of Republic of Korea; (C) Males of Canada; (D) Females of China; (E) Females of Republic of Korea; (F) Females of Canada. CRC, colorectal cancer.

The incidence rate of Chinese males aged 50−59 years showed an increasing trend, with an AAPC of 1.8 (95% CI: 0.8, 2.8). However, females aged 60−69 years had a decreasing trend with an AAPC of −1.2 (95% CI: −2.0, −0.4). All age groups of males and females in Korea showed an upward trend and the males aged 30−39 years had the most significant growth with an AAPC of 6.2 (95% CI: 4.5, 8.0). In Canada, the high-age group showed a downward trend while the low-age group showed an upward trend (Table 3 ).

3. Age-specific incidence trends in CRC between Republic of Korea, Canada and China.

| Country | Age group (year) | Trend 1 | Trend 2 | 2003−2012

AAPC (95% CI) (%) |

||||

| Period | APC (95% CI) (%) | Period | APC (95% CI) (%) | |||||

| CRC, colorectal cancer; APC, annual percentage change; AAPC, average annual percentage change; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; *, P<0.05. | ||||||||

| Male | ||||||||

| China | 30−39 | 2003−2012 | 0.1 (−3.0, 3.2) | 0.1 (−3.0, 3.2) | ||||

| 40−49 | 2003−2012 | 0.3 (−1.3, 2.0) | 0.3 (−1.3, 2.0) | |||||

| 50−59 | 2003−2012 | 1.8* (0.8, 2.8) | 1.8* (0.8, 2.8) | |||||

| 60−69 | 2003−2012 | 0.3 (−0.6, 1.3) | 0.3 (−0.6, 1.3) | |||||

| 70−79 | 2003−2006 | 4.1* (0.8, 7.6) | 2006−2012 | −1.4* (−2.5, −0.3) | 0.4 (−0.6, 1.4) | |||

| 80+ | 2003−2012 | −0.6 (−1.9, 0.8) | −0.6 (−1.9, 0.8) | |||||

| Republic of Korea | 30−39 | 2003−2012 | 6.2* (4.5, 8.0) | 6.2* (4.5, 8.0) | ||||

| 40−49 | 2003−2005 | 13.4* (1.5, 26.8) | 2005−2012 | 2.4* (0.9, 3.9) | 4.8* (2.6, 7.0) | |||

| 50−59 | 2003−2010 | 5.4* (3.7, 7.1) | 2010−2012 | −2.2 (−13.3, 10.3) | 3.6* (1.3, 6.0) | |||

| 60−69 | 2003−2012 | 4.4* (3.1, 5.7) | 4.4* (3.1, 5.7) | |||||

| 70−79 | 2003−2009 | 5.9* (4.7, 7.2) | 2009−2012 | −1.8 (−5.2, 1.7) | 3.3* (2.2, 4.4) | |||

| 80+ | 2003−2012 | 5.5* (3.4, 7.6) | 5.5* (3.4, 7.6) | |||||

| Canada | 30−39 | 2003−2012 | 4.4* (1.1, 7.9) | 4.4* (1.1, 7.9) | ||||

| 40−49 | 2003−2012 | 1.8* (0.9, 2.7) | 1.8* (0.9, 2.7) | |||||

| 50−59 | 2003−2012 | −0.7 (−1.6, 0.1) | −0.7 (−1.6, 0.1) | |||||

| 60−69 | 2003−2012 | −1.5* (−2.2, −0.7) | −1.5* (−2.2, −0.7) | |||||

| 70−79 | 2003−2008 | 0.2 (−1.2, 1.7) | 2008−2012 | −4.2* (−6.1, −2.2) | −1.8* (−2.7, −0.8) | |||

| 80+ | 2003−2012 | −0.5 (−1.3, 0.2) | − 0.5 (−1.3, 0.2) | |||||

| Female | ||||||||

| China | 30−39 | 2003−2012 | 1.6 (−2.2, 5.6) | 1.6 (−2.2, 5.6) | ||||

| 40−49 | 2003−2012 | −0.4 (−2.5, 1.7) | −0.4 (−2.5, 1.7) | |||||

| 50−59 | 2003−2008 | −0.9 (−2.9, 1.2) | 2008−2012 | 2.2 (−0.8, 5.2) | 0.5 (−0.8, 1.8) | |||

| 60−69 | 2003−2012 | −1.2* (−2.0, −0.4) | −1.2* (−2.0, −0.4) | |||||

| 70−79 | 2003−2012 | −0.5 (−1.5, 0.4) | −0.5 (−1.5, 0.4) | |||||

| 80+ | 2003−2012 | 0.3 (−0.5, 1.1) | 0.3 (−0.5, 1.1) | |||||

| Republic of Korea | 30−39 | 2003−2012 | 5.2* (3.2, 7.1) | 5.2* (3.2, 7.1) | ||||

| 40−49 | 2003−2005 | 13.8 (−1.4, 31.4) | 2005−2012 | 2.8* (0.9, 4.8) | 5.2* (2.4, 8.0) | |||

| 50−59 | 2003−2012 | 2.5* (1.4, 3.7) | 2.5* (1.4, 3.7) | |||||

| 60−69 | 2003−2007 | 6.4* (5.0, 7.9) | 2007−2012 | 0.6 (−0.3, 1.6) | 3.2* (2.5, 3.8) | |||

| 70−79 | 2003−2009 | 4.6* (3.6, 5.6) | 2009−2012 | 0.0 (−2.7, 2.9) | 3.1* (2.2, 3.9) | |||

| 80+ | 2003−2012 | 4.0* (3.3, 4.7) | 4.0* (3.3, 4.7) | |||||

| Canada | 30−39 | 2003−2012 | 5.3* (1.6, 9.1) | 5.3* (1.6, 9.1) | ||||

| 40−49 | 2003−2012 | 2.4* (1.3, 3.6) | 2.4* (1.3, 3.6) | |||||

| 50−59 | 2003−2012 | 0.7* (0.3, 1.1) | 0.7* (0.3, 1.1) | |||||

| 60−69 | 2003−2012 | −1.4* (−1.9, −0.9) | −1.4* (−1.9, −0.9) | |||||

| 70−79 | 2003−2010 | −0.3 (−1.3, 0.7) | 2010−2012 | −5.6 (−12.6, 1.9) | −1.5* (−2.9, −0.1) | |||

| 80+ | 2003−2012 | −0.7* (−1.3, −0.1) | −0.7* (−1.3, −0.1) | |||||

Discussion

In this study, we comprehensively performed an epidemiological analysis of CRC incidence and mortality in 20 worldwide regions and compared the ten-year incidence trend changes in countries of each continent with China. We also separately compared the trends in age-specific incidence rates in China, Republic of Korea and Canada. The incidence rate of CRC in China was relatively low compared with that of developed countries. However, the burden of CRC would continue to increase in the future due to China’s large population and the current upward trend.

According to the IARC estimates, in 2018, CRC accounted for 10.2% of all incidence in the world, with approximately 1,026,215 cases in men and 823,303 cases in women (12). CRC was the second leading cause of cancer death in 2018 with about 484,224 and 396,568 deaths estimated in males and females, respectively. CRC is considered to be related to changes in lifestyles after economic and social development (13). The burden of developed countries is generally heavier than developing countries, but with development, the incidence in developing countries is increasing rapidly. Genetics contribute to individual risk (14), but CRC incidence is largely affected by modifiable diet and lifestyle factors (13). CRC’s risk factor mainly includes obesity, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol drinking and dietary patterns. Immigration epidemiological studies have shown that after immigrants change their eating habits, the incidence rate quickly approaches local residents (15). Therefore, the key to controlling the incidence of CRC is to correct lifestyles in time. Physical activity is the most direct method of prevention which can benefit gut motility, the immune system and metabolic hormones (16).

In comparison between countries of five continents and China, the incidence rate of most countries is increasing from 2003 to 2012. These five countries represent the highest level of incidence in each continent in CI5. Although incidence in China is lower, the increasing trend of incidence is clear. There are some differences in the etiology of colon and rectum cancer but the trend of change is basically the same. The proportion of pathological types in different populations is significantly different. Proximal colon cancer is more prevalent in women and descending colon cancer is more common in men (17). Proximal colon cancer is the most common subtype among white and black Americans, and rectal cancer accounts for the highest proportion among Koreans (13,18,19).

There are many methods for CRC screening, including fecal occult blood test (FOBT) and fecal immunochemical test (FIT), and even multitarget stool DNA testing. These testing methods are non-invasive, low cost, easy to accept, and convenient to carry out in the large population. But colonoscopy, the gold-standard screening method, is a highly sensitive test. Colonoscopy can reduce the incidence and mortality of CRC, and over-diagnosis and over-treatment caused by colonoscopy are also acceptable (20,21). Some studies also confirm that screening is cost-effective compared with no screening (22). Many countries combine colonoscopy with FOBT and FIT to develop their own screening programs to deal with the high disease burden. Generally, the age for CRC screening is set at 50−74 years old. Canada formulated the Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control (CSCC) in 2005 and implemented it in 2006 (23). The CSCC has gradually carried out CRC screening projects throughout Canada. Republic of Korea began screening for five common cancers including CRC in 1999, and continued to expand the scale of screening (24). China launched the Rural Cancer Screening Project in 2004. In 2005, Haining and Jiashan in Zhejiang province took the lead in starting CRC screening and the project gradually expanded to 33 sites nationwide. The three countries are at different stages of screening. Screening in China is gradually expanding, and Korea has already in the stage where the incidence rate is rising rapidly after a large number of cases have been detected through screening. In Canada, the incidence rate has decreased, but the incidence in the younger age group has begun to rise. With the expansion of screening, the trend in Korea and Canada will also happen in China.

The phenomenon of early-onset cases of CRC needs to be focused on. People under 50 years old in Canada show an increasing trend in both sexes, and AAPC is statistically significant. This increasing trend weakens with age increases. Considering disease progression of CRC takes time, studies believe that these people have been in a westernized lifestyle and diet for a long time in childhood (25). Therefore, the early onset of CRC is worth studying and special attention should be paid to childhood obesity and living habits.

The disadvantage of this study is that the data set used is a public database and lacks pathological types. If the composition comparison and trend analysis of pathological types can be carried out, it can have more valuable references for health policy formulation.

Conclusions

The incidence of CRC in China was in the world average level, but was lower than that of developed countries. However, because of the large population in China and the increasing trend of CRC, the burden of this disease will continue to increase in the future with the development of social economy and population aging. Developed countries have gone through this process and explored feasible screening programs to reduce the burden of CRC. Facing the growth burden of CRC, China should learn the experience of developed countries and formulate comprehensive prevention and control policies. Screening should be expanded to control CRC and more attention should be paid to young people in China.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Chinese Academic of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (No. 2018-I2M-3-003 and No. 2019-I2M-2-002).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Rongshou Zheng, Email: zhengrongshou@163.com.

Wenqiang Wei, Email: weiwq@cicams.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Fleming M, Ravula S, Tatishchev SF, et al Colorectal carcinoma: Pathologic aspects. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3:153–73. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2012.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China National guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer 2020 in China (English version) Chin J Cancer Res. 2020;32:415–45. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2020.04.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner H, Stock C, Hoffmeister M Effect of screening sigmoidoscopy and screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BMJ. 2014;348:g2467. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: Colorectal cancer screening, incidence, and mortality — United States, 2002-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:884–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schreuders EH, Ruco A, Rabeneck L, et al Colorectal cancer screening: a global overview of existing programmes. Gut. 2015;64:1637–49. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-309086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2020. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today

- 7.Human Development Report 2019. New York: the United Nations Development Programme, 2019. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr2019.pdf

- 8.Ferlay J, Colombet M, Bray F. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, CI5plus: IARC CancerBase No. 9. Lyon: IARC, 2018. Available online: http://ci5.iarc.fr

- 9.NCI DoCCaPS. Joinpoint Trend Analysis Software. Available online: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/

- 10.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, et al Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19:335–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doll R, Cook P Summarizing indices for comparison of cancer incidence data. Int J Cancer. 1967;2:269–79. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910020310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keum N, Giovannucci E Global burden of colorectal cancer: emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:713–32. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jasperson KW, Tuohy TM, Neklason DW, et al Hereditary and familial colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2044–58. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mousavi SM, Fallah M, Sundquist K, et al Age- and time-dependent changes in cancer incidence among immigrants to Sweden: colorectal, lung, breast and prostate cancers. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:E122–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruiz-Casado A, Martin-Ruiz A, Perez LM, et al Exercise and the hallmarks of cancer. Trends cancer. 2017;3:423–41. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy N, Ward HA, Jenab M, et al Heterogeneity of colorectal cancer risk factors by anatomical subsite in 10 European countries: A multinational cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1323–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy G, Devesa SS, Cross AJ, et al Sex disparities in colorectal cancer incidence by anatomic subsite, race and age. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1668–75. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin A, Kim KZ, Jung KW, et al Increasing trend of colorectal cancer incidence in Korea, 1999-2009. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:219–26. doi: 10.4143/crt.2012.44.4.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welch HG, Black WC Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:605–13. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.PDQ Screening and Prevention Editorial Board. Colorectal Cancer Screening (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US), 2002. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65825/

- 22.Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB, Brenner H Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening. Epidemiol Rev. 2011;33:88–100. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxr004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Council TCSfCCC. Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control. 2006. Available online: https://www.cancer.ca

- 24.Li N, Li Q, Chen YH, et al A survey of cancer prevention and control in Korea. Zhongguo Zhong Liu. 2011;20:251–55. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu PH, Wu K, Ng K, et al Association of obesity with risk of early-onset colorectal cancer among women. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:37–44. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]