Abstract

microRNAs regulate numerous biological processes, making them potential therapeutic agents. Problems with delivery and stability of these molecules have limited their usefulness as treatments. We demonstrate that synthetic high-density lipoprotein nanoparticles (HDL NPs) topically applied to the intact ocular surface are taken up by epithelial and stromal cells. microRNAs complexed to HDL NPs (miR-HDL NPs) are similarly taken up by cells and tissues and retain biological activity. Topical treatment of diabetic mice with either HDL NPs or miR-HDL NPs significantly improved corneal re-epithelialization following wounding compared with controls. Mouse corneas with alkali burn-induced inflammation, topically treated with HDL NPs, displayed clinical, morphological and immunological improvement. These results should yield a novel HDL NP-based eye drop for patients with compromised wound healing ability (diabetics) and/or corneal inflammatory diseases (e.g. dry eye).

Keywords: Corneal epithelium, microRNA, alkali burn, diabetic cornea, EphA2

Summary:

HDL nanoparticles are the core of a novel eye drop for patients with compromised corneal wound healing ability and/or acute and chronic inflammation.

INTRODUCTION

The ocular anterior surface epithelia, in conjunction with the tear film, provides an efficient barrier to the external environment. While such a barrier is essential for the health of the eye, it can prevent delivery of drugs necessary to combat various disease states, such as inflammation and infections. Delivery is further compounded by the blink reflex, which in addition to removing debris and microorganisms from the ocular surface, can also remove topically applied medications. To circumvent this problem, a variety of topical ocular drug delivery systems have been developed. These include non-viscous eye drops, nanoparticles, liposomes, microspheres, as well as contact lenses, gels and solid inserts ([1, 2] and references therein). One of the problems with nanoparticles and microspheres is that particles can be quickly cleared from the ocular surface [1]. Chitosan-stabilized nanoparticles have mucoadhesive properties and have been used to deliver cyclosporine, acyclovir, and daptomycin to the cornea and conjunctiva ([3, 4] and references therein). Solid lipid nanoparticles were successfully used to deliver indomethacin topically to the anterior segmental tissues of rabbits [5]. Interestingly, nanoparticles have not been utilized to deliver miRNAs to the cornea, limbus or conjunctiva.

microRNAs (miRNAs) are small (~22 nucleotides in length), “noncoding” or “non-messenger” RNAs that are part of the RNAi silencing machinery (for reviews see [6–9]). As such they contribute to the regulation of a wide variety of biological processes in both normal and disease situations. Therefore, miRNAs hold great promise as potential therapeutic agents. A major hurdle to realizing this goal has been effective formulation and delivery of therapeutic miRNAs to the cytoplasm of target cells in a biologically active form. A conceptual breakthrough to this problem occurred with the demonstration that natural high-density lipoproteins (HDL), isolated from human serum, contained miRNAs and that these HDL-bound miRNAs had improved stability compared with naked miRNAs [10]. In addition, native HDLs deliver bound miRNAs to cells that express the high-affinity receptor of HDLs, called scavenger receptor type B-1 (SR-B1), whereupon the miRNA regulates target gene expression, as expected [10, 11]. In some ways to mimic this natural system, we have developed functional HDL-like nanoparticles (HDL NPs) [12–15]. HDL NPs: (i) are physically and chemically similar to natural mature HDLs; (ii) contain apolipoprotein A-1 (apoA-1), which is the main protein constituent of HDLs ([16] and references therein); (iii) selectively target cells that express SR-B1 [14, 15, 17]; and (iv) are not toxic to normal healthy cells in vivo or in vitro [14, 16–18]. Recently, we demonstrated that the HDL NP platform can be extensively tailored to efficiently deliver any desired individual (i.e. similar to miRNAs) or complementary pairs of RNA strands (e.g. siRNA duplex pairs) on separate HDL NPs or on the same HDL NP for potent target gene regulation [13]. In vitro and in vivo data have been published demonstrating that RNA-HDL NP conjugates specifically target SR-B1 and are therapeutically efficacious against prostate and ovarian cancers [13, 19, 20].

Herein we report that synthetic, functional HDL NPs can deliver miR-205 to primary human corneal epithelial cells (HCECs) and miR-146a to a macrophage cell line (J744). We chose miR-205 because of its positive role in corneal epithelial cell migration due to targeting SHIP2 [21, 22]. miR-146a was selected because it is a key gene mediator for proinflammatory signaling regulated by NF-ĸB [23]. Once in cells, the miRNAs interacted with their respective targets resulting in translational repression and alteration in downstream signaling activity. We demonstrate that topical application of HDL NPs in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) can penetrate the unperturbed ocular surface of mice and enter the corneal and limbal epithelial cells as well as the stromal keratocytes. Using a diet-induced obesity (DIO) mouse model of diabetes, we show that both a scrambled miR-HDL NP solution and a miR-205-HDL NP solution topically applied to corneal epithelial debridement wounds, significantly improved wound closure compared to controls. Furthermore, in a mouse model of corneal inflammation, we demonstrate that treatment by topical application of HDL NPs to the ocular surface, significantly resolves inflammation clinically, morphologically and immunologically compared with PBS and control NPs. Collectively our findings strongly suggest that topical delivery of either miR-HDL NPs or HDL NPs, alone, to corneal and limbal epithelia have vast treatment potential for many diseased situations such as diabetic wound repair, inflammation, infection, and correction of limbal stem cell deficiency.

RESULTS

HDL NPs are taken up by human corneal epithelial cells.

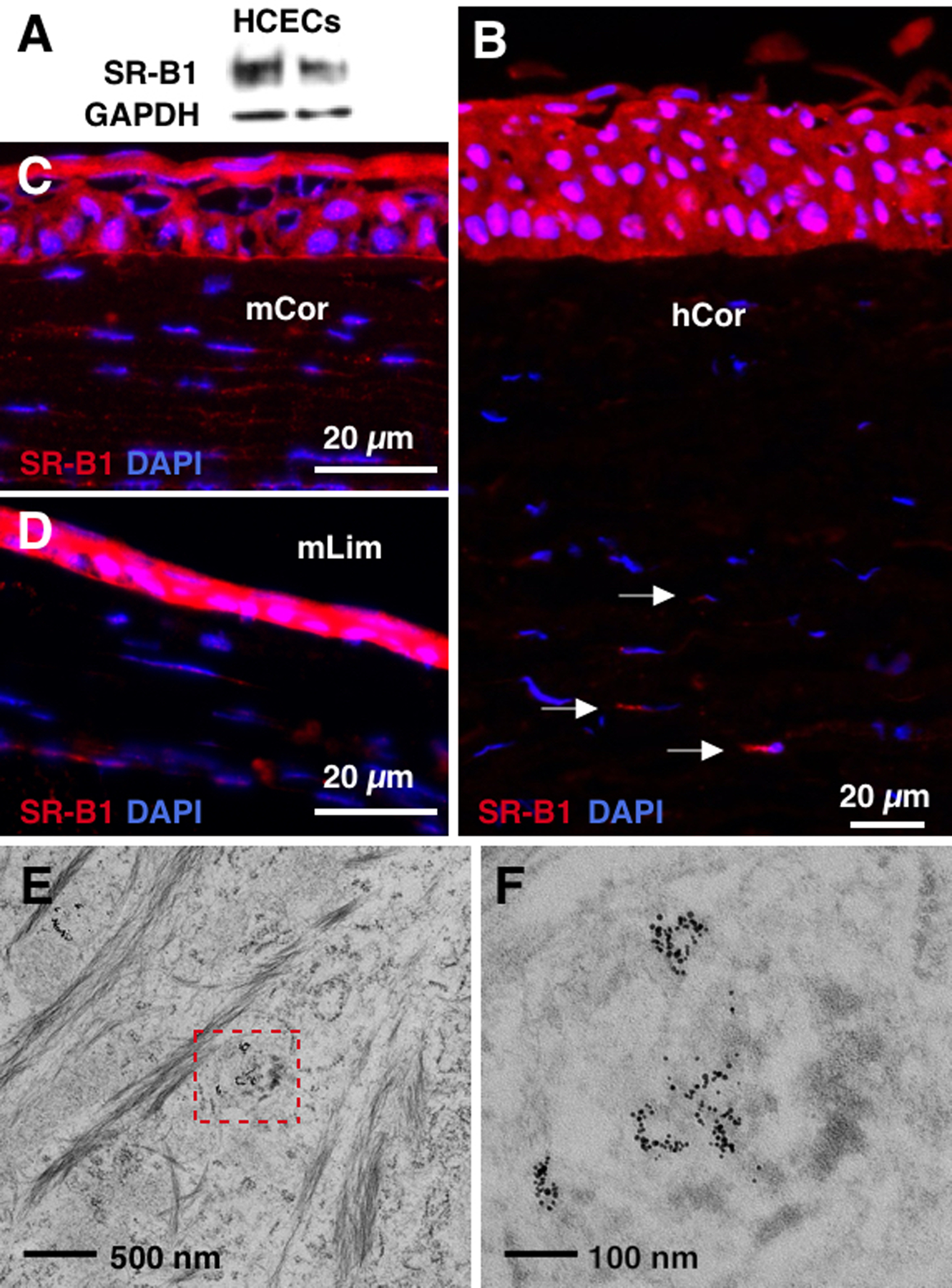

HDLs are essential components of the lipid transport system and SR-B1 is the major receptor that controls the selective uptake of HDL cargo into cells ([24] and references therein). SR-B1 is primarily expressed in the liver and tissues involved in steroid metabolism (e.g., adrenal glands and gonads), as well as malignant cells [25–27]. However, SR-B1 has been detected on cultured human keratinocytes as well as in mouse and human epidermis [28]. Using immunofluorescence and immunoblotting, we determined that SR-B1 is prominently expressed on HCECs (Figure 1A) as well as human and mouse corneal and limbal epithelia (Figures 1B–D). SR-B1 is also present on the stromal keratocytes (Figure 1B–D). HDL NPs were synthesized and characterized as previously reported demonstrating size and charge similar to native HDL (Table S1 and Figure S1) [13]. To demonstrate that HDL NPs target HCECs in an SR-B1 dependent manner, HCECs were treated with fluorescently-labeled DiI-HDL NPs and/or an SR-B1 blocking antibody. Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in uptake of HDL NPs into HCECs which is reduced by adding the SR-B1 blocking antibody (Figure S2). To determine further whether the HDL NPs were taken up by HCECs, a 50 nM solution of HDL NPs in PBS was added to the cultures for 24 hrs. Cells were fixed and processed for transmission electron microscopy in order to directly visualize the gold nanoparticle (AuNP) core of the synthetic HDL NPs. At this time point, non-membrane-bound Au NPs were readily found, free in the cytoplasm; few if any particles were detected in the nucleus or in proximity of the cell membrane (Figure 1E–F and Figure S3). This suggests a non-endocytic mechanism of HDL NP transport into HCECs via SR-B1, similar to what has been described in other cells [24, 29, 30]. Of note, testing reveals that the miR-HDL NP conjugates remain stable under the conditions and over the time course (i.e. 24 hrs) that the cell assay was conducted (Figure S4A).

Figure 1. Corneal epithelial cells and stromal keratocytes express SR-B1 for HDL NP targeting.

(A) Western blotting shows that SR-B1 is expressed by HCECs. N=5. (B-D) Immunostaining detects SR-B1 in human and mouse corneal epithelia and keratocytes. hCor: human cornea. mCor: mouse cornea. mLim: mouse limbus. N=3. (E, F) 24 hrs after exposure, TEM showed that HDL NP (black dots) uptake was observed in the cytoplasm of HCECs. Inset: high mag image of HDL NPs.

miRs-205 and −146a complexed with HDL NPs maintain functionality in vitro.

To assess whether miRNAs complexed to HDL NPs would retain their function, we chose miR-205 and miR-146a as “proof-of-concept” miRNAs. For example, we reported that miR-205 negatively regulates the lipid phosphatase SHIP2 in epithelial cells resulting in the activation of Akt signaling [22]. One of the functions of SHIP2 is to limit epithelial cell migration [21]. Consequently by suppressing SHIP2, miR-205 promotes epithelial migration via cofilin activation [21]. Therefore, we assessed the efficacy of miR-205-HDL NPs as a wound healing agent. We have demonstrated the complexation of RNAs to HDL NPs in the past [13]. Briefly, RNA is condensed with lipids into a particle whose surface contains HDL NPs. In this form, the RNAs are relatively protected from nuclease degradation and the conjugates are targeted to SR-B1[13]. Our working model for the cytosolic delivery of particle-associated miRNA is that HDL NP binding of SR-B1 enables membrane fusion and subsequent delivery of the miRNA to the cytoplasm of the recipient cell. Physical and chemical characterization of a pair of miR-HDL NPs is provided in Figure S1.

In order to test binding of the conjugates to target cells and delivery of miRNAs, a single strand miR-205 or miR-146a mimic was complexed to HDL NPs and HCECs were exposed to the miR-HDL NPs. A scrambled miRNA-HDL NP (NC-miR-HDL NP) served as a control. Cells were collected and washed at various time points and then the UV-Vis absorbance values were obtained at 260 and 520 nm to determine the concentration of RNA and Au NP, respectively. Data reveal that the concentration of gold in the cells stays constant over time, and the amount of RNA increased in the cells over time. These observations demonstrate stable binding and uptake of RNA by target cells (Figure S4B).

In order to test the function of the miR-HDL NPs, HCECs were exposed to miR-205-HDL NP or NC-miR-HDL NP (48 hrs). Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates revealed that miR-205-HDL NPs decreased SHIP2 (Figure 2A) and increased p-Akt levels (Figure 2B) when compared with the NC-miR-HDL NP. To determine whether miR-205-HDL NPs had biological activity in vitro, we conducted a series of scratch wound assays using a limbal-derived corneal epithelial cell line (hTCEpi) [31, 32]. Mitomycin C-treated cells grown to confluence received linear scratch wounds followed by treatment with 10 nM solutions of NC-miR-HDL NP or miR-205-HDL NP. Cells were imaged in a Nikon Biostation at 3 hr intervals until wound closure (18 hr). miR-205-HDL NP treatment resulted in wound closure after 6 hrs compared to an 18 hr closure time for the NC-miR-HDL NP treatment (Figure 2C, Figure S5). This is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that miR-205 enhanced cell migration [21] and establishes miR-205-HDL NPs as having biological activity in vitro.

Figure 2. miRs-205 and −146a complexed with HDL NPs maintain functionality in vitro.

(A, B) hTCEpi cells were treated with miR-205-HDL NP or NC-miR-HDL NP (control NP). Western blotting showed that miR-205-HDL NP treatment decreased SHIP2 (A) and increased p-Akt (B). *: p<0.05. N=3. (C) Confluent hTCEpi cells were scratch wounded and then allowed to migrate until wounds were closed. miR-205-HDL NP enhanced cell migration. *: p<0.05. N=3. (D) Colorimetric assay showed that miR-146a-HDL NP inhibits NF-κB activity in J774-dual cell line. *: p<0.05. N=6. Unpaired t-tests were conducted.

miR-146a plays a role in maintaining limbal epithelial cells but is not involved in corneal epithelial differentiation [33]. This miRNA is upregulated in diabetic limbal epithelial cells and delays cell migration and wound closure in diabetic limbal and corneal epithelial cells [33]. However, we have chosen miR-146a, as this miRNA is considered a key gene regulator for proinflammatory signaling regulated by NF-ĸB [23, 34, 35]. Therefore, we assessed the efficacy of miR-146a-HDL NPs as an anti-inflammatory agent using mouse J774-dual macrophages, which express the secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) gene downstream of the NF-ĸB consensus transcriptional response element. After addition of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), NF-ĸB activity was quantified by sampling the cell culture media for SEAP using a QUANTI-Blue colorimetric assay. A miR-146a mimic was complexed to HDL NPs and J774-dual murine macrophages were exposed to the miR-146a-HDL NP (48 hrs). Compared to a NC-miR HDL NP, HDL NPs carrying miR146a significantly reduced the signal of LPS-induced SEAP (Figure 2D). This indicates that miR-146a complexed to HDL NPs has biological activity in vitro.

HDL NPs penetrate the intact ocular anterior epithelia after topical application.

Having established in vitro efficacy, it was important to determine whether HDL NPs could penetrate an intact epithelium following topical application. To this end, we applied 3 μl of a Cy3-tagged miR-HDL NP (1 μM in PBS) to intact non-wounded mouse corneas every 30 min for 4 hrs. Mice were sacrificed 3 hrs later, eyes were harvested, embedded in OCT, sectioned and viewed with a fluorescent microscope. No fluorescence was detected in the HDL NPs lacking Cy3 (Figure 3A, B) whereas Cy3 could be readily detected in the superficial and basal corneal epithelial cells as well as in the stromal keratocytes (Figure 3C–E). As a positive control, mice were treated with the Cy3-tagged miR-HDL NPs immediately following a 1 mm central corneal epithelial debridement wound. 24 hrs post-treatment, mice were sacrificed and eyes harvested and prepared as described above. As expected, more signal was observed throughout the cornea and limbus of the wounded eyes (Figures 3F–J). While little Cy3 signal was observed in the conjunctiva from the non-wounded eyes, Cy3 signal was detected in the conjunctival epithelium (Figure S6) and stromal cells from the mice with corneal epithelial debridement wounds (Figure 3H, I). This is strong evidence that the HDL NP construct can be used to deliver miRNAs topically to cells and tissues of the intact as well as compromised ocular anterior segment.

Figure 3. Cy3–tagged HDL NPs penetrate the cornea.

Apotome optical sections of resting (A-D) and wounded (F-I) corneas treated with Cy3–tagged HDL NPs (C,D and H,I) or untreated (A, B and F, G). Cy3 signal (red) is easily detected in the cytoplasm of resting (C, D) and wounded (H, I) corneal epithelial cells and keratocytes. Keratin 12 (green) was used as a marker for corneal epithelium. s: superficial layer. w: wing cells. b: basal layer. k: keratocytes. Cy3 positive fluorescence intensity in unwounded (E) and wounded (J) corneal epithelium was measured using ImageJ. *: p<0.05. N=3. Unpaired t-tests were conducted.

HDL NPs and miR-205-HDL NPs exhibit biological activity in vivo.

We wanted to establish whether miR-205, which is a positive regulator of corneal epithelial migration and wound healing [21], could restore proper wound healing in mouse corneas when complexed with HDL NPs. Mice on normal diets heal corneal epithelial debridement (1 mm) wounds extremely rapidly, often within 24 hrs [36]. Conversely, diet-induced obesity (DIO) mice are a well-recognized model for diabetes [37, 38] and mimic aspects of this disease such as delayed wound healing [39, 40]. Thus mice on a conventional diet and DIO mice were anesthetized, and a 1 mm area of central corneal epithelium was removed with a rotating diamond burr [31, 41]. Immediately following wounding, DIO mice (6) received 1 μl of a miR-205-HDL NP solution (1 μM in PBS) or a NC-miR-HDL NP solution topically, every 30 min for 2 hrs. Use of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid as an anesthetic attenuates blinking for approximately 2 hours thus aiding to maximize the amount of solution in contact with the surface. The degree of healing was monitored clinically using a 0.5% fluorescein stain, and the rate of epithelial healing was evaluated by measuring the wound size with image processing software (ImageJ v.1.5). As expected, untreated mice on normal diets sealed wounds within 24 hrs, whereas untreated DIO mice showed little evidence of healing at this time point (Figures 4A). This was contrasted by the NC-miR-HDL NP and miR-205-HDL NP treatments, which were equally effective in sealing wounds as evidenced by approximately 60% closure, 24 hr-post wounding (Figures 4A). Interestingly, because of the observed similarities in the data obtained with the HDL NPs carrying scrambled miR and miR-205, repeated studies confirmed that HDL NPs, alone, and miR-205-HDL NPs sealed wounds equally; however, the kinetics were different (Figure 4B). HDL NPs sealed wounds in a linear fashion, whereas miR-205-HDL NPs had an initial 12 hr lag period, followed by a rapid closure over the next 12 hrs (Figure 4B). Notably, because of the stability of the miR-HDL NP conjugates (Figure S4), the data support that HDL NP without miRNA is superior in this context, not because of degradation of the miRNAs, but because of the enhanced kinetics of HDL NP activity. Based on these unexpected findings, we concentrated on the HDL NP as a novel therapeutic modality for accelerating ocular surface wound healing.

Figure 4. HDL NP treatment improves corneal wound closure in DIO mice.

(A) Corneal images and (B) epithelial corneal wound closure percentage in DIO mouse corneas treated with NC-miR-HDL NP, miR-205-HDL NP, HDL NPs or control (PBS). ND PBS represents non-diabetic control mice treated with PBS. Green fluorescence represents areas devoid of epithelium (i.e., corneal wounds). (N = 8). *: p < 0.05. Unpaired t-tests were conducted.

HDL NPs upregulate p-Akt and increase actin filaments in HCECs following wounding.

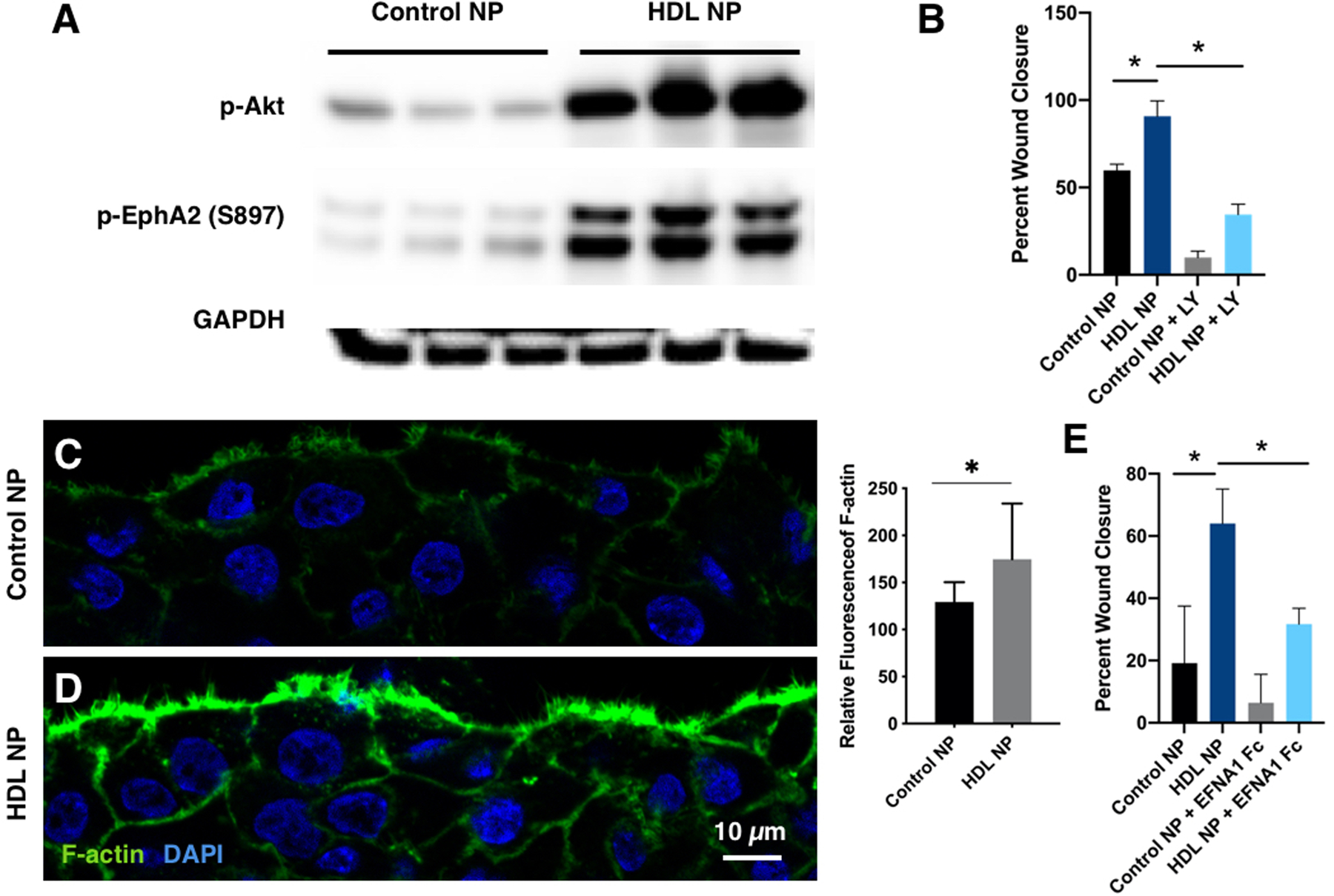

Given the similarity in response between miR-205-HDL NPs and NC-HDL NPs with respect to wound closure in vivo (Figures 4), we postulated that the HDL NPs might be affecting the Akt signaling pathway in a manner similar to miR-205 [22]. A scratch wound assay was performed using HCECs treated with HDL NPs (10 nM) or control NPs (10 nM). For these experiments, control NPs were synthesized using the same inert AuNP core, thus, sharing the same size and shape as HDL NPs, but their surfaces were passivated with polyethyleneglycol (PEG). Twenty four hr-post wounding cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. Not surprisingly, the HDL NP treatment resulted in a marked up-regulation of p-Akt compared with the control-NP-treated samples (Figure 5A). To confirm that the positive effect of HDL NPs on cell migration was via the Akt signaling pathway, the scratch wound assay was repeated in corneal epithelial cells treated overnight with HDL NPs + LY294002, which inactivates PI3K. PI3K signals through Akt [42], thus if HDL NPs are working via Akt signaling, such treatment should negatively affect wound closure. As expected, when compared with HDL NP treatment, HDL NP + LY294002 sealed scratch wounds at a slower rate (Figure 5B, Figure S7A), thus confirming that HDL NPs seal wounds via Akt signaling.

Figure 5. HDL NP treatment affects Akt and EphA2 signaling.

(A) Immunoblotting showing that HDL NPs increased p-Akt and pS897-EphA2. N=3. (B) hTCEpi cells were treated with HDL NPs or control NPs as well as LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor; 30 μM). Confluent cells were scratch wounded and then allowed to migrate until wounds were closed. *: p<0.05. N=3. (C, D) HDL NPs increase F-actin at the wound edge. hTCEpi cells were scratch wounded. 3 hrs after scratching, immunostaining showed a more distinct actin filament meshwork at the wound edge of HDL NP treated cells compared with controls. Fluorescence intensity of F-actin in C and D was measured using Image J. *: p<0.05. N=7. (E) hTCEpi cells were treated with HDL NPs or control NPs as well as EFNA1 Fc, which inhibits p-EphA2-S897. Confluent cells were scratch wounded and then allowed to migrate until wounds were closed. *: p<0.05. N=3. Unpaired t-tests were conducted.

Following a wounding stimulus, the initial response of a cell is to polarize and extend protrusions in the direction of migration. These protrusions can be large, broad lamellipodia or spike-like filopodia, and are usually driven by actin polymerization [43]. As actin remodeling and cell migration can be regulated, in part via Akt signaling [44], we investigated the distribution of filamentous actin (F-actin) in HDL NP-treated HCECs following wounding (Figures 5C, D). There was a marked increase in F-actin as shown by phalloidin staining at the leading edge of the HDL NP-treated migrating cells compared with the control NP-treated cells (Figures 5C, D). This suggests that HDL NPs are positive regulators of F-actin polymerization during the initial migratory phase of cell migration [45]. We also investigated the status of p-EphA2-S897, since phosphorylation by Akt at S897, can signal in a ligand-independent manner to increase cell migration [46]. Treatment of cells with HDL NPs resulted in a dramatic increase in p-EphA2-S897 expression compared with control NPs (Figure 5A). To confirm the role of EphA2-S897 in this signaling axis, we introduced EphrinA1 (EFNA1), a specific ligand for EphA2 [47] into HCECs that were scratch wounded and treated with HDL NPs or control NPs. EFNA1 inhibits S897 phosphorylation and induces ligand-dependent signaling of EphA2, which leads to EphA2 degradation [46]. As expected, treatment with EFNA1-Fc dramatically attenuated the HDL NP-enhanced cell migration following scratch wounding (Figure 5E, Figure S7B). This is strong evidence that HDL NPs positively affect cell migration via targeting EphA2. EphA2-S897 phosphorylation is associated with the reorganization of actin filaments at the leading edge of a migrating sheet [46]. Collectively, these findings provide a mechanistic explanation for how HDL NPs function to enhance re-epithelialization.

HDL NPs display anti-inflammatory properties in vivo.

Having established that HDL NPs complexed with miR-146a could attenuate NF-kB signaling in vitro (Figure 2D), we asked whether synthetic HDL NPs themselves had anti-inflammatory properties in the eye, as reported in other systems [48, 49]. To address this question, we used the venerable alkaline burn model to induce an inflammatory response in mouse corneas [50, 51]. In this model, a 1 mm filter paper disc soaked in 1 M NaOH is placed on the mouse cornea for 30 sec, removed, and then the ocular surface is vigorously washed. The corneal epithelium, stromal, and inflammatory cells are involved in the injury, repair, and wound healing processes, which are accompanied by the production of numerous cytokines [50, 51]. After wounding, groups of mice (n=5) were treated once daily for 4 days with either PBS (control), control NPs in PBS (control) or HDL NPs in PBS. Groups of mice (n=5) were sacrificed at 1, 3, 7, and 14 days post treatment, corneas were isolated and prepared for qPCR and histological examination. Prior to sacrifice all mice were evaluated clinically for corneal clarity based on the degree of haze [52] and surface integrity as determined by exclusion of fluorescein dye.

Following the alkali burn, corneal opacification could be easily visualized clinically (Figure 6). By day 7 post-wounding, PBS- and control NP-treated corneas remained opaque (Figures 6A, B) whereas the HDL NP-treated mice showed a 40–50% (p < 0.05) improvement in corneal opacity and surface integrity (Figures 6A, B). Equally impressive were the morphological changes between the control NP and HDL NP treatments at day 7 (Figures 6C–F; Figure S8). Control NP treated corneas displayed a range of thickened and disorganized corneal epithelia as well as a wide spectrum of stromal alterations, ranging from a stroma filled with inflammatory cells (Figure 6C) to randomly oriented collagen bundles resulting in a disorganized appearance (Figure 6D). The infiltrates were identified as T cells by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining [53] for CD3 at day 7 (Figure S9). In contrast, the HDL NP-treated corneas showed well-organized stratified epithelia (Figures 6E, F) and stroma with collagen bundles highly organized in a plywood-like fashion that were relatively devoid of inflammatory cells (Figures 6E, F and Figure S8). In some HDL NP treatment groups, stromal keratocytes were prominent (Figure 6F).

Figure 6. HDL NP treatment enhances the clarity of corneas after alkali burn.

Filter papers (1 mm) soaked in NaOH (1 M) were placed on the corneal surface of 6 wk old WT mice for 30 sec and the ocular surface washed extensively with PBS. Corneas were topically treated with HDL NPs, control NPs (inert AuNP core, passivated with polyethyleneglycol (PEG)) or PBS daily for 7 days. Uninjured eye is shown as a reference for normal conditions. Eyes were imaged (A) and the degree of haze was analyzed (B). (C-F) At 7 days post treatment, representative H&E images of mouse cornea from two control NPs (C, D) and two HDL NPs treated eyes (E, F). Arrowhead: vertical bundle of collagen fibers. Arrow: keratocytes. Mann-Whitney U Tests were conducted. N=8. *: p < 0.05.

We evaluated the temporal expression of interleukin (IL) - 1α, β, IL-6, CCL-2, iNOS, MMP-9 and MMP-12 following treatment of alkali-burned corneas. The corneal healing process is initiated immediately after epithelial injury through the release of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1α, β, and IL-6 [54–56]. Chemokines such as CCL2 play important roles in the recruitment of macrophages to the site of injury during an inflammatory event [57, 58], as well as the inflammatory mediator iNOS, which is associated with activated macrophages [59]. Elevated levels of Gelatinase or MMP-9 are associated with numerous diseases of the cornea and can facilitate corneal ulceration [60]. MMP-12 has been shown to inhibit corneal inflammation via regulation of CCL2 [51]. Day 1 post-injury, Il1a, Il1b, Il6 and Ccl2 were most highly expressed (Figure 7), which is consistent with an initial stage of inflammation. By day 3, HDL NP treatment significantly reduced the expression levels of Il1a, ll1b, Il6, Inos, Mmp9 and Ccl2 when compared with control NPs (Figure 7). All genes evaluated, returned to pre-treatment levels by day 7 (Figure 7). Collectively, these findings strongly indicate that topical application of HDL NPs to the corneal surface following a chemical burn can aid in attenuating the inflammatory response.

Figure 7. HDL NP has anti-inflammation activity.

Filter paper (1 mm) soaked in NaOH (1 M) were placed on the corneal surface of 6 wk old WT mice for 30 sec and then washed extensively with PBS. Corneas were topically treated with HDL NPs, control NPs (inert AuNP core, passivated with polyethyleneglycol (PEG)) or PBS daily for 7 days. Whole corneal tissues were dissected and total RNAs were isolated for RT-qPCR for inflammation-related genes at post injury day 1, 3, and 7 (N=8). *: p < 0.05. Unpaired t-tests were conducted.

CONCLUSIONS and OUTLOOK:

In this study, we show that topical application of synthetic, functional HDL NPs to the intact ocular surface can be taken up by corneal and limbal epithelial cells as well as stromal keratocytes. Furthermore, we demonstrate that HDL NPs are effective vehicles for the delivery of miRNAs to the cornea, and once taken up by cells, these miRNAs maintain biological activity. Of particular significance, HDL NPs inherently enhance re-epithelialization following corneal wounding in a mouse model of diabetes and can act as an anti-inflammatory agent following a chemical burn to the cornea. These novel observations on the therapeutic activity of HDLs in an ocular setting have vast translational significance. For example, diabetes-related ocular complications such as diabetic keratopathies are a general health problem and 46–67% of diabetic patients have problems with their ocular surface [61]. Corneal opacities resulting from inflammation are the cause of 3–5% of global blindness [62]. Dry eye disease with associated inflammation affects 16 million Americans [63], and it has been estimated that chemical injuries to the eye represent between 12%−22% of ocular traumas [64]. We believe the results presented herein will lead to the development of a HDL NP-based eye drop for patients with compromised wound healing ability and/or corneal inflammatory diseases.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

HDL nanoparticles (HDL NPs) synthesis

For HDL NP synthesis, we used an aqueous solution of 5nm diameter citrate stabilized gold nanoparticles (Au NP) (80 nM, Nanocomposix) or we used 5nm diameter Au NPs synthesized using standard protocols [65]. In either case, Au NPs were mixed with a 5-fold molar excess of purified human apoA-I (1.3mg/mL, MyBioSource, MBS135961) in a glass vial. The Au NP/apoA-I mixture was incubated for 1hr at room temperature (RT) on a flat bottom shaker at 60rpm. Next, 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[3-(2-pyridyldithio)propionate] (PDP-PE; Avanti Polar Lipids) dissolved in dichloromethane (CH2Cl2, 1 mM) was added to the Au NP/apoA-I solution in 250-fold molar excess to the Au NP. The solution was vortexed, and then a 1:1 solution of cardiolipin (heart, bovine) (CL; Avanti Polar Lipids) and 1,2-dilinoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1’-rac-glycerol) (18:2 PG; Avanti Polar Lipids) dissolved in CH2Cl2 (1mM) was added to the Au NP/apoA-I/PDP-PE solution at 250-fold molar excess to the Au NP and the solution was, again, vortexed. Mixing and brief sonication (~2 minutes) of the mixture caused it to become opaque and pink in color. The resulting mixture was gradually heated to ~40 ⁰C with constant stirring to evaporate CH2Cl2 and to transfer the phospholipids onto the particle surface and into the aqueous phase (~20 min). The reaction was complete when the solution returned to a transparent red color. The resultant HDL NPs were incubated overnight at RT on a flat bottom shaker at 60 rpm and then purified and concentrated using tangential flow filtration (TFF; KrosFlo Research Iiii TFF System, Repligen, model 900–1613). HDL NPs were stored at 4 ⁰C until use. The concentration of the HDL NPs was measured using UV-vis spectroscopy (Agilent 9453) where Au NPs have a characteristic absorption at λmax = 520 nm, and the extinction coefficient for 5 nm Au NPs is 9.696 × 106 M−1cm−1.

To synthesize miR-HDL NPs, miRNA and 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP, Avanti Polar Lipids) were mixed. Individual 3P and 5P miRNA sequences of miR-205, miR-146a, scrambled-miR, or Cy3-labeled scrambled-miR (Integrated DNA Technologies) were re-suspended in nuclease free water (500 μM, final). Complement pairs of each target were mixed in nuclease free water at a concentration enabling direct addition of HDL NPs (100 nM) at 25-fold molar excess to each RNA sequence (2.5 μM, final per RNA sequence). An ethanolic (EtOH) solution of DOTAP was then added at a 40-fold molar excess to the RNA. The mixture of DOTAP and RNA was briefly sonicated and vortexed (x3) and then incubated at RT for 15 min prior to addition to a solution of 100 nM HDL NPs in water. After the DOTAP-RNA mixture was added to the HDL NPs, the solvent mixture is 9:1 (v/v, water:EtOH). This solution was incubated overnight at RT on a flat bottom shaker at 60 rpm. Resulting miRNA-HDL NPs were purified via centrifugation (15,870 x g, 50 min) and the supernatant with unbound starting materials removed. The resulting pellet was re-suspended, and the concentration of the miRNA-HDL NPs was calculated as described for HDL NPs. For miR-HDL NPs, a strong absorption at λmax = 260 nm confirmed the presence of miRNA.

Control NP synthesis

For control NP synthesis, an aqueous solution of citrate stabilized gold nanoparticles (Au NP) (80 nM, 5 nm, Nanocomposix) were used. Au NPs were mixed with a 500-fold molar excess of triethylene glycol mono-11-mercaptoundecyl ether (PEG SH; Sigma) (3 mM in EtOH) in 20% EtOH. Materials were vortexed and incubated at RT at 60 rpm on a flat bottom orbital shaker overnight. The resultant control NPs were purified and concentrated via tangential flow filtration (TFF; KrosFlo Research Iiii TFF System, Repligen, model 900–1613). Control NPs were stored at 4 ⁰C until use. The concentration of the control NPs was calculated as described for HDL NPs.

Human and mouse cornea

Normal human corneal tissues were obtained from the Eversight eye banks (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and used for HCEC culturing and immunostaining (see protocols below). Wild-type male C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Charles River. Diet-induced obesity (DIO) mice were obtained from the Jackson laboratory. The onset and maintenance of diabetes was determined by glucose tolerance test (2 hr fasting >192 mg/dl) [66]. To generate central corneal debridement wounds, mouse corneal epithelia were removed by application of a rotating diamond burr to the surface of the central cornea. The limbal epithelium remained intact. For the alkali burn assay, 1 mm filter papers, soaked in 1 M NaOH were applied to the corneal surface for 30 sec. After removing filter papers, eyes were washed extensively with PBS. To visualize the wounded area, 0.5% fluorescein dye in PBS was applied topically at different time points and wound closure was measured using Image J. Clinical scores of cornea haze were determined with a dissecting scope as previously described [52]. At the end point of the experiment, mice were sacrificed, eyes removed, fixed in 10% Buffered Formalin solution, and corneal tissues were processed for paraffin embedding for histological analysis by H&E staining. In some experiments, corneal rims with cornea, limbus and underlying stroma were processed for total RNA isolation (see protocol below). Animal procedures were approved by the Northwestern University Animal Care and Use Committee (PI: R.M.L.; Protocol approval numbers IS00006868 and IS00001798).

Fluorescent and transmission electron microscopies

Immunofluorescence staining using human and mouse eyes was conducted as previously described [67] using antibodies against SR-BI (ab52629, knockout validated), or Keratin 12 (Santa Cruz biotechnology) with detection using an Alexa Fluor-488 or −555 nm–conjugated goat anti–mouse or anti–rabbit antibody (Invitrogen). Filamentous actin (F-actin) was detected by incubating coverslips for 2 hr at room temperature with Alexa-488-conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed as previously described [41]. Ultrathin sections were viewed with a FEI Tecnai Spirit G2 transmission electron microscope at 120 kV.

Cell culture

Epithelial cells were isolated as explants from human cornea as described before [68]. Cells (HCEC) were cultured in CnT-pr media (CELLnTEC, Bern, Switzerland), and first passage cells were used for experiments. Immortalized corneal epithelial cells, hTCEpi, were cultured in keratinocyte serum free media (Life Technologies) as described before [68]. Murine macrophage J774-dual cells (InvivoGen) were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS, 100 μg/mL Normocin, and Pen-Strep with selection antibiotics, 5 μg/mL Blasticidin and 100 μg/mL Zeocin.

Western blotting

Western blots were performed as described previously [41, 68]. The following antibodies were used: SR-B1 (ab52629: 1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), p-Akt (S473)(9271; 1:1000), p-EphA2 (S897) (6347, 1:1000), SHIP2 (2730, 1:500) (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA, USA), GAPDH (ab9485, 1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA).

Scratch wound assay

Cells were seeded at 300,000 cells/well, grown to confluence on 12-well plastic dishes and treated with HDL NPs (10nM). After 12 hr exposure to the NPs, linear scratch wounds (in triplicate) were created on the confluent monolayers using a 200 μl pipette tip. Wound closure was monitored using Nikon Biostation CT live cell imaging system at 3 hr intervals for 30 hrs. The percentage decrease in the wound gaps were calculated using ImageJ and normalized to the time 0 wounds. To remove cells from the cell cycle prior to wounding, mitomycin C (5 μg/ml) was added into the medium for 2 hrs as pretreatment.

NF-κB QUANTI-Blue assay

J774-dual cells were grown to confluence in T75 flask in selection antibiotics (5 μg/ml Blasticidin and 100 μg/ml Zeocin). 50,000 cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates. The following day, cells were treated with 1 ng/mL LPS (E.coli, O55:B5) and 25 nM HDL NP or miR-HDL NP. After 48 hours, inflammatory response was assessed by measuring SEAP activity by QUANTI-Blue assay according to manufacturer’s protocol (InvivoGen). Briefly, 20 μL of cell supernatant was moved from each well to a new 96 well plate. 180 μL of pre-warmed QUANTI-Blue solution (InvivoGen) was added to each sample. The absorbance was measured at 655 nm in a microplate plate reader (Synergy 2, BioTek).

HDL penetration assay

Mice were anesthetized with gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (i.p. 1000 mg/kg), which allows them to stay sedated for up to 4 hours, then 3 μl of a Cy3-tagged HDL NP (1 μM in PBS) were applied topically onto intact non-wounded or wounded corneas of anesthetized WT mice every 30 min for 4 hrs. Mice were sacrificed 3 hrs later, eyes were harvested, embedded in OCT, sectioned and viewed with a fluorescent microscope.

Real time qPCR

Total RNAs were isolated and purified with a miRNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Real-time qPCR was performed with a Roche LightCycler 96 System using the Roche FastStart Essential DNA Green Master (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

To determine statistical significance, unpaired t-test with two tailed distribution were performed in Excel, Mann-Whitney U Test were conducted in R, and Pearson’s Chi squared test was used for 2-sample test for equality of proportions without continuity correction using prop.test() in R. The data are shown as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) in line graphs and means ± standard deviation (SD) in bar graphs. The differences were considered significant for p values of <0.05. All experiments were replicated at least three times.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The NU-SBDRC Skin Tissue Engineering and Morphology Core facility assisted in morphologic analysis. The NU-SBDRC Is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Grant AR075049. Imaging work was performed at the Northwestern University Center for Advanced Microscopy generously supported by NCI CCSG P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center. High content imaging was performed on the Nikon Biostation CT system purchased with the support of NIH 1S10OD021704-01. This research is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY06769, EY017539 and EY019463 (to R.M.L.); a Dermatology Foundation research grant and Career Development Award (to H.P.); and an Eversight research grant (to H.P.); the Northwestern University Post Graduate Program in Cutaneous Biology of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32AR060710 (to A.E.C); AR064144 and AR071168 (to K.Q.L.); the Prostate Cancer Foundation (to C.S.T.), the Center for Regenerative Nanomedicine (CRN), and the Nanyang Technological Institute-Northwestern University (NTU-NU) Institute for Nanomedicine (to C.S.T.).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Subrizi A; Del Amo EM; Korzhikov-Vlakh V; Tennikova T; Ruponen M; Urtti A, Drug Discov Today 2019. DOI 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phua JL; Hou A; Lui YS; Bose T; Chandy GK; Tong L; Venkatraman S; Huang Y, Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19 (10). DOI 10.3390/ijms19102977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krishnaswami V; Kandasamy R; Alagarsamy S; Palanisamy R; Natesan S, Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 110, 7–16. DOI 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.01.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao Y; Tan YF; Wong YS; Liew MWJ; Venkatraman S, Mar Drugs 2019, 17 (6). DOI 10.3390/md17060381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balguri SP; Adelli GR; Majumdar S, Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2016, 109, 224–235. DOI 10.1016/j.ejpb.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berezikov E, Nat Rev Genet 2011, 12 (12), 846–60. DOI 10.1038/nrg3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman RC; Farh KK; Burge CB; Bartel DP, Genome Res 2009, 19 (1), 92–105. DOI 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavker RM; Jia Y; Ryan DG, Hum Genomics 2009, 3 (4), 332–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis BP; Burge CB; Bartel DP, Cell 2005, 120 (1), 15–20. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vickers KC; Palmisano BT; Shoucri BM; Shamburek RD; Remaley AT, Nat Cell Biol 2011, 13 (4), 423–33. DOI 10.1038/ncb2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu Z; Shen WJ; Kraemer FB; Azhar S, Mol Cell Biol 2012, 32 (24), 5035–45. DOI 10.1128/MCB.01002-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plebanek MP; Mutharasan RK; Volpert O; Matov A; Gatlin JC; Thaxton CS, Scientific reports 2015, 5, 15724. DOI 10.1038/srep15724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMahon KM; Plebanek MP; Thaxton CS, Adv Funct Mater 2016, 26 (43), 7824–7835. DOI 10.1002/adfm.201602600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang S; Damiano MG; Zhang H; Tripathy S; Luthi AJ; Rink JS; Ugolkov AV; Singh AT; Dave SS; Gordon LI; Thaxton CS, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110 (7), 2511–6. DOI 10.1073/pnas.1213657110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luthi AJ; Lyssenko NN; Quach D; McMahon KM; Millar JS; Vickers KC; Rader DJ; Phillips MC; Mirkin CA; Thaxton CS, J Lipid Res 2015, 56 (5), 972–85. DOI 10.1194/jlr.M054635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thaxton CS; Rink JS; Naha PC; Cormode DP, Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2016, 106 (Pt A), 116–131. DOI 10.1016/j.addr.2016.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rink JS; Yang S; Cen O; Taxter T; McMahon KM; Misener S; Behdad A; Longnecker R; Gordon LI; Thaxton CS, Mol Pharm 2017, 14 (11), 4042–4051. DOI 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plebanek MP; Bhaumik D; Bryce PJ; Thaxton CS, Mol Cancer Ther 2018, 17 (3), 686–697. DOI 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murmann AE; Gao QQ; Putzbach WE; Patel M; Bartom ET; Law CY; Bridgeman B; Chen S; McMahon KM; Thaxton CS; Peter ME, EMBO Rep 2018, 19 (3). DOI 10.15252/embr.201745336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murmann AE; McMahon KM; Haluck-Kangas A; Ravindran N; Patel M; Law CY; Brockway S; Wei JJ; Thaxton CS; Peter ME, Oncotarget 2017, 8 (49), 84643–84658. DOI 10.18632/oncotarget.21471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu J; Peng H; Ruan Q; Fatima A; Getsios S; Lavker RM, FASEB J 2010, 24 (10), 3950–9. DOI 10.1096/fj.10-157404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu J; Ryan DG; Getsios S; Oliveira-Fernandes M; Fatima A; Lavker RM, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105 (49), 19300–5. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0803992105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taganov KD; Boldin MP; Chang KJ; Baltimore D, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103 (33), 12481–6. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0605298103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhainds D; Brissette L, Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2004, 36 (1), 39–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mooberry LK; Sabnis NA; Panchoo M; Nagarajan B; Lacko AG, Front Pharmacol 2016, 7, 466. DOI 10.3389/fphar.2016.00466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rhainds D; Bourgeois P; Bourret G; Huard K; Falstrault L; Brissette L, J Cell Sci 2004, 117 (Pt 15), 3095–105. DOI 10.1242/jcs.01182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahzad MM; Mangala LS; Han HD; Lu C; Bottsford-Miller J; Nishimura M; Mora EM; Lee JW; Stone RL; Pecot CV; Thanapprapasr D; Roh JW; Gaur P; Nair MP; Park YY; Sabnis N; Deavers MT; Lee JS; Ellis LM; Lopez-Berestein G; McConathy WJ; Prokai L; Lacko AG; Sood AK, Neoplasia 2011, 13 (4), 309–19. DOI 10.1593/neo.101372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuruoka H; Khovidhunkit W; Brown BE; Fluhr JW; Elias PM; Feingold KR, The Journal of biological chemistry 2002, 277 (4), 2916–22. DOI 10.1074/jbc.M106445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMahon KM; Mutharasan RK; Tripathy S; Veliceasa D; Bobeica M; Shumaker DK; Luthi AJ; Helfand BT; Ardehali H; Mirkin CA; Volpert O; Thaxton CS, Nano Lett 2011, 11 (3), 1208–14. DOI 10.1021/nl1041947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang M; Jin H; Chen J; Ding L; Ng KK; Lin Q; Lovell JF; Zhang Z; Zheng G, Small 2011, 7 (5), 568–73. DOI 10.1002/smll.201001589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng H; Kaplan N; Yang W; Getsios S; Lavker RM, Am J Pathol 2014, 184 (12), 3262–71. DOI 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robertson DM; Li L; Fisher S; Pearce VP; Shay JW; Wright WE; Cavanagh HD; Jester JV, Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2005, 46 (2), 470–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winkler MA; Dib C; Ljubimov AV; Saghizadeh M, PLoS One 2014, 9 (12), e114692. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0114692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reale M; D’Angelo C; Costantini E; Laus M; Moretti A; Croce A, J Immunol Res 2018, 2018, 7510174. DOI 10.1155/2018/7510174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tahamtan A; Teymoori-Rad M; Nakstad B; Salimi V, Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1377. DOI 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stepp MA; Zieske JD; Trinkaus-Randall V; Kyne BM; Pal-Ghosh S; Tadvalkar G; Pajoohesh-Ganji A, Experimental eye research 2014, 121, 178–93. DOI 10.1016/j.exer.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rebuffe-Scrive M; Surwit R; Feinglos M; Kuhn C; Rodin J, Metabolism 1993, 42 (11), 1405–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Surwit RS; Kuhn CM; Cochrane C; McCubbin JA; Feinglos MN, Diabetes 1988, 37 (9), 1163–7. DOI 10.2337/diab.37.9.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen Y; Pfluger T; Ferreira F; Liang J; Navedo MF; Zeng Q; Reid B; Zhao M, Scientific reports 2016, 6, 26525. DOI 10.1038/srep26525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kneer K; Green MB; Meyer J; Rich CB; Minns MS; Trinkaus-Randall V, Experimental eye research 2018, 175, 44–55. DOI 10.1016/j.exer.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park JK; Peng H; Katsnelson J; Yang W; Kaplan N; Dong Y; Rappoport JZ; He C; Lavker RM, The Journal of cell biology 2016, 215 (5), 667–685. DOI 10.1083/jcb.201604032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vlahos CJ; Matter WF; Hui KY; Brown RF, The Journal of biological chemistry 1994, 269 (7), 5241–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ridley AJ; Schwartz MA; Burridge K; Firtel RA; Ginsberg MH; Borisy G; Parsons JT; Horwitz AR, Science 2003, 302 (5651), 1704–9. DOI 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kakinuma N; Roy BC; Zhu Y; Wang Y; Kiyama R, The Journal of cell biology 2008, 181 (3), 537–49. DOI 10.1083/jcb.200707022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moftah H; Dias K; Apu EH; Liu L; Uttagomol J; Bergmeier L; Kermorgant S; Wan H, Cell Adh Migr 2017, 11 (3), 211–232. DOI 10.1080/19336918.2016.1195942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miao H; Li DQ; Mukherjee A; Guo H; Petty A; Cutter J; Basilion JP; Sedor J; Wu J; Danielpour D; Sloan AE; Cohen ML; Wang B, Cancer Cell 2009, 16 (1), 9–20. DOI 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaplan N; Ventrella R; Peng H; Pal-Ghosh S; Arvanitis C; Rappoport JZ; Mitchell BJ; Stepp MA; Lavker RM; Getsios S, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2018, 59 (1), 393–406. DOI 10.1167/iovs.17-22941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henrich SE; Hong BJ; Rink JS; Nguyen ST; Thaxton CS, J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141 (25), 9753–9757. DOI 10.1021/jacs.9b00651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Foit L; Thaxton CS, Biomaterials 2016, 100, 67–75. DOI 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sotozono C; He J; Matsumoto Y; Kita M; Imanishi J; Kinoshita S, Curr Eye Res 1997, 16 (7), 670–6. DOI 10.1076/ceyr.16.7.670.5057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolf M; Clay SM; Zheng S; Pan P; Chan MF, Scientific reports 2019, 9 (1), 11579. DOI 10.1038/s41598-019-47831-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gupta N; Kalaivani M; Tandon R, Br J Ophthalmol 2011, 95 (2), 194–8. DOI 10.1136/bjo.2009.173724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J; Kaplan N; Wysocki J; Yang W; Lu K; Peng H; Batlle D; Lavker RM, FASEB J 2020. DOI 10.1096/fj.202001020R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghasemi H, Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2018, 26 (1), 37–50. DOI 10.1080/09273948.2016.1277247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Osthoff M; Brown KD; Kong DC; Daniell M; Eisen DP, Mol Vis 2014, 20, 38–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilson SE; Mohan RR; Mohan RR; Ambrosio R Jr.; Hong J; Lee J, Prog Retin Eye Res 2001, 20 (5), 625–37. DOI 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Combadiere C; Potteaux S; Rodero M; Simon T; Pezard A; Esposito B; Merval R; Proudfoot A; Tedgui A; Mallat Z, Circulation 2008, 117 (13), 1649–57. DOI 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.745091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luster AD, N Engl J Med 1998, 338 (7), 436–45. DOI 10.1056/NEJM199802123380706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lowenstein CJ; Padalko E, J Cell Sci 2004, 117 (Pt 14), 2865–7. DOI 10.1242/jcs.01166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaufman HE, Cornea 2013, 32 (2), 211–6. DOI 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182541e9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sayin N; Kara N; Pekel G, World J Diabetes 2015, 6 (1), 92–108. DOI 10.4239/wjd.v6.i1.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roongpoovapatr V; Prabhasawat P; Isipradit S; Shousha MA; Charukamnoetkanok P, Infectious Keratitis: The Great Enemy. In Visual Impairment and Blindness, IntechOpen: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Farrand KF; Fridman M; Stillman IO; Schaumberg DA, Am J Ophthalmol 2017, 182, 90–98. DOI 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Haring RS; Sheffield ID; Channa R; Canner JK; Schneider EB, JAMA Ophthalmol 2016, 134 (10), 1119–1124. DOI 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Piella J; Bastus NG; Puntes V, Bioconjug Chem 2017, 28 (1), 88–97. DOI 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Menichella DM; Jayaraj ND; Wilson HM; Ren D; Flood K; Wang XQ; Shum A; Miller RJ; Paller AS, Mol Pain 2016, 12. DOI 10.1177/1744806916666284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kaplan N; Wang J; Wray B; Patel P; Yang W; Peng H; Lavker RM, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2019, 60 (10), 3570–3583. DOI 10.1167/iovs.19-27656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peng H; Kaplan N; Hamanaka RB; Katsnelson J; Blatt H; Yang W; Hao L; Bryar PJ; Johnson RS; Getsios S; Chandel NS; Lavker RM, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109 (35), 14030–4. DOI 10.1073/pnas.1111292109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.