Abstract

Background

Suaeda glauca (S. glauca) is a halophyte widely distributed in saline and sandy beaches, with strong saline-alkali tolerance. It is also admired as a landscape plant with high development prospects and scientific research value. The S. glauca chloroplast (cp) genome has recently been reported; however, the mitochondria (mt) genome is still unexplored.

Results

The mt genome of S. glauca were assembled based on the reads from Pacbio and Illumina sequencing platforms. The circular mt genome of S. glauca has a length of 474,330 bp. The base composition of the S. glauca mt genome showed A (28.00%), T (27.93%), C (21.62%), and G (22.45%). S. glauca mt genome contains 61 genes, including 27 protein-coding genes, 29 tRNA genes, and 5 rRNA genes. The sequence repeats, RNA editing, and gene migration from cp to mt were observed in S. glauca mt genome. Phylogenetic analysis based on the mt genomes of S. glauca and other 28 taxa reflects an exact evolutionary and taxonomic status of S. glauca. Furthermore, the investigation on mt genome characteristics, including genome size, GC contents, genome organization, and gene repeats of S. gulaca genome, was investigated compared to other land plants, indicating the variation of the mt genome in plants. However, the subsequently Ka/Ks analysis revealed that most of the protein-coding genes in mt genome had undergone negative selections, reflecting the importance of those genes in the mt genomes.

Conclusions

In this study, we reported the mt genome assembly and annotation of a halophytic model plant S. glauca. The subsequent analysis provided us a comprehensive understanding of the S. glauca mt genome, which might facilitate the research on the salt-tolerant plant species.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-021-07490-9.

Keywords: Suaeda glauca, Mitochondrial genome, Repeats, Phylogenetic analysis

Background

Chenopodiaceae is among the large families of angiosperms that mainly include Spinacia oleracea, Chenopodium quinoa Willd, and Beta vulgaris [1–3]. Chenopodiaceae plants are mostly annual herbs, half shrubs, shrubs, living in the desert, and saline soil areas. Therefore, they often show xerophytic adaptation. As an annual herb of Chenopodiaceae, S. glauca grows in saline-alkali land and beaches. It displays a strong salt tolerance and drought tolerance capacity and has high value as medicine and food material [4–6]. Moreover, S. glauca possesses immense ecological importance as it can tolerate heavy metals at higher levels and could be used as a super accumulator of heavy metals. The environmental protection and remediation of contaminated soil make it a natural resource with significant economic and ecological importance [7].

Plant mt is involved in numerous metabolic processes related to energy generation and the synthesis and degradation of several compounds [8]. Margulis’ endosymbiosis theory suggests that mt originated from archaea living in nucleated cells when eukaryotes swallowed the bacteria. Later it evolved into organelles with special functions during the long-term symbiosis [9–11], incorporated as an additional mt genome. Mitochondria convert biomass energy into chemical energy through phosphorylation and provide energy for life activities. Besides, it is involved in cell differentiation, apoptosis, cell growth, and cell division [12–15]. Therefore, mitochondria play a crucial role in plant productivity and development [16]. For most seed plants, nuclear genetic information is inherited from both parents, while cp and mt are inherited from the maternal parent. This genetic mechanism eliminates the paternal lines’ influence, thus reducing the difficulty of genetic research and facilitating the study of genetic mechanisms [17].

With the development of sequencing technology, an increasing number of mt genomes have been reported. Up to Jan. 2021, 351 complete mt genomes have been deposited in GenBank Organelle Genome Resources. Long periods of mutualism leave mitochondria with some of their original DNA lost, and some of them transferred, leaving only the DNA that codes for it [18, 19]. Mt DNA has long been recognized as tending to integrate DNA from various sources through intracellular and horizontal transfer [20]. Therefore, the mt genome in plants has significant differences in length, gene sequence, and gene content [21]. The mt genome length of the smallest known terrestrial plant is about 66 Kb, and the largest terrestrial plant mt genome length is 11.3 Mb [22, 23]. As a result, the amount of genes in terrestrial plants varies widely, typically between 32 and 67 [24]. In this study, we sequenced and annotated the mt genome of S. glauca and compared it with the genomes of other angiosperms (as well as gymnosperms), which provides additional information for a better understanding of the genetics of the halophyte S. glauca.

Results

Genomic features of the S. glauca mt genome

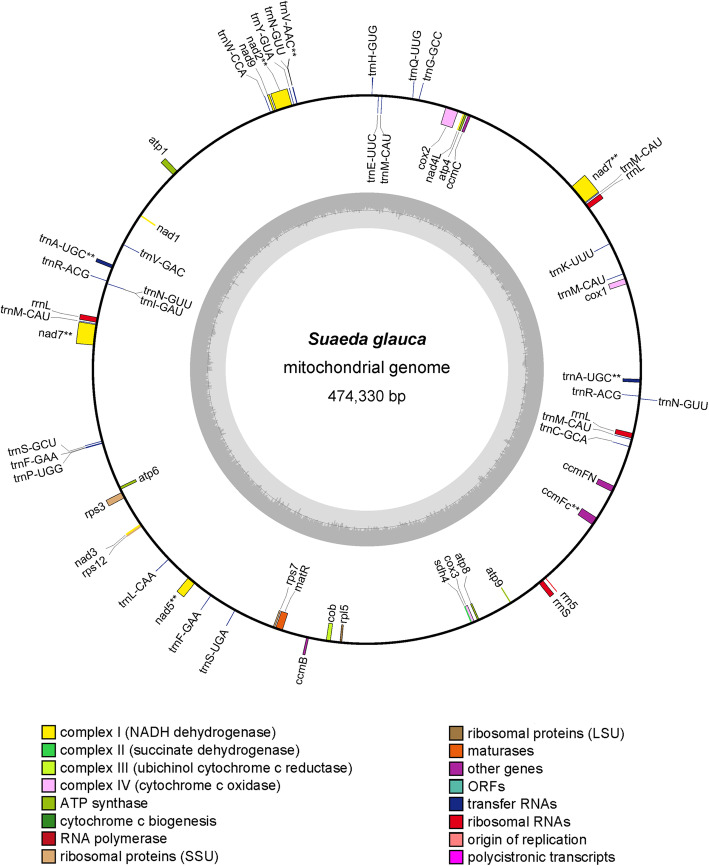

The S. glauca mt genome is circular with a length of 474,330 bp. The base composition of the genome is A (28.00%), T (27.93%), C (21.62%), G (22.45%). There are 61 genes annotated in the mt genome, including 27 protein-coding genes, 29 tRNA genes, and 5 rRNA genes. The functional categorization and physical locations of the annotated genes were presented in Fig. 1. According to our findings, the mt genome of S. glauca encodes 26 different protein (nad7 has two copies) that could be divided into 9 classes (Table 1): NADH dehydrogenase (7 genes), ATP Synthase (5 genes), Cytochrome C Biogenesis (4 genes), Cytochrome C oxidase (3 genes), Ribosomal proteins (SSU) (3 genes), Ribosomal proteins (LSU) (1 gene), Transport membrane protein (1 gene), Maturases (1 gene), and Ubiquinol Cytochrome c Reductase (1 gene). The homologs of S. glauca mt genes in the mt genomes of H. sapiens, S. cerevisiae, and A. thaliana were identified and listed in Table S1. All of the protein-coding genes used ATG as starting codon, and all three stop codons TAA, TGA, and TAG were found with the following utilization rate: TAA 44.4%, TGA 37.04%, and TAG 18.52% (Table S2). It is reported that the mt genomes of land plants contain variable number of introns [25]. In the mt genome of S. glauca, there are 8 intron-containing genes (nad2, nad5, nad7 with two copyies, cox2, ccmFc, trnA-UGC, and trnV-AAC) harboring 15 introns in total with a total length of 16,743 bp. The intron lengths varied from 105 bp (trnV-AAC) to 2103 bp (nad2). The gene nad7 has two copies in the mt genome, and each copy contains 4 introns, which is the highest intron number. The trnV-AAC, instead, contains only one intron with a length of 105 bp, which is the smallest intron.

Fig. 1.

The circular map of S. glauca mt genome. Gene map showing 61 annotated genes of different functional groups

Table 1.

Gene profile and organization of S. glauca mt genome

| Group of genes | Gene name | Length | Start codon | Stop codon | Amino acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NADH dehydrogenase | nad1 | 327 | ATG | TGA | 108 |

| nad2a | 915 | ATG | TAA | 304 | |

| nad3 | 357 | ATG | TAA | 118 | |

| nad4L | 273 | ATG | TAA | 90 | |

| nad5a | 1452 | ATG | TGA | 483 | |

| nad7 a (2) | 1092 | ATG | TAG | 363 | |

| nad9 | 579 | ATG | TAA | 192 | |

| ATP synthase | atp1 | 1521 | ATG | TAA | 506 |

| atp4 | 597 | ATG | TAG | 198 | |

| atp6 | 741 | ATG | TAA | 246 | |

| atp8 | 480 | ATG | TGA | 159 | |

| atp9 | 240 | ATG | TGA | 79 | |

| Cytochrome c biogenesis | ccmB | 621 | ATG | TGA | 206 |

| ccmC | 744 | ATG | TAA | 247 | |

| ccmFCa | 1338 | ATG | TAG | 445 | |

| ccmFN | 1635 | ATG | TGA | 544 | |

| Cytochrome c oxidase | cox1 | 1575 | ATG | TAA | 524 |

| cox2a | 768 | ATG | TAA | 255 | |

| cox3 | 798 | ATG | TGA | 265 | |

| Maturases | matR | 1968 | ATG | TAG | 655 |

| Ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase | cob | 1182 | ATG | TGA | 393 |

| Ribosomal proteins (LSU) | rpl5 | 555 | ATG | TAA | 184 |

| Ribosomal proteins (SSU) | rps3 | 1680 | ATG | TAA | 559 |

| rps7 | 447 | ATG | TAA | 148 | |

| rps12 | 381 | ATG | TGA | 126 | |

| Transport membrane protein | sdh4 | 294 | ATG | TGA | 97 |

| Ribosomal RNAs | rrn5 | 119 | |||

| rrnS | 1303 | ||||

| rrnL (3) | 1369 | ||||

| Transfer RNAs | trnA-UGCa,b (2) | (73, 73) | |||

| trnC-GCA | 76 | ||||

| trnE-UUC | 72 | ||||

| trnF-GAA (2) | (74, 74b) | ||||

| trnG-GCC | 74 | ||||

| trnH-GUGb | 76 | ||||

| trnI-GAUb | 79 | ||||

| trnK-UUU (2) | (73,73) | ||||

| trnL-CAA | 83 | ||||

| trnM-CAU (4) | (74b,76,76,76) | ||||

| trnN-GUU (3) | (74b,74b,74) | ||||

| trnP-UGG | 90 | ||||

| trnQ-UUG | 72 | ||||

| trnR-ACG b (2) | (75,75) | ||||

| trnS-GCU | 91 | ||||

| trnS-UGA | 88 | ||||

| trnV-GACb | 72 | ||||

| trnV-AACa | 94 | ||||

| trnW-CCA | 74 | ||||

| trnY-GUA | 84 |

Notes: The numbers after the gene names indicate the duplication number. Lowercase a indicates the genes containing introns, and lowercase b indicates the cp-derived genes

It has been reported that most land plants contain 3 rRNA genes [9, 11]. Consistently, three rRNA genes rrn5 (119 bp), rrnS (1303 bp), and rrnL (1369 bp) were annotated in S. glauca mt genome. Besides, 20 different transfer RNAs were identified in S. glauca mt genome transporting 18 amino acids, since more than one transfer RNAs might transport the same amino acid for different codons. For example, trnS-UGA and trnS-GCU transport Ser for synonymous codons UCA and AGC, respectively. Moreover, we observed that transfer RNA trnF-GAA, trnM-CAU, and trnN-GUU have two different structures with the same anticodon. Taking trnM-CAU as an example, both A and B structures share the same anticodon CAU transporting amino acid Met (Figure S1).

Repeat sequences anaysis

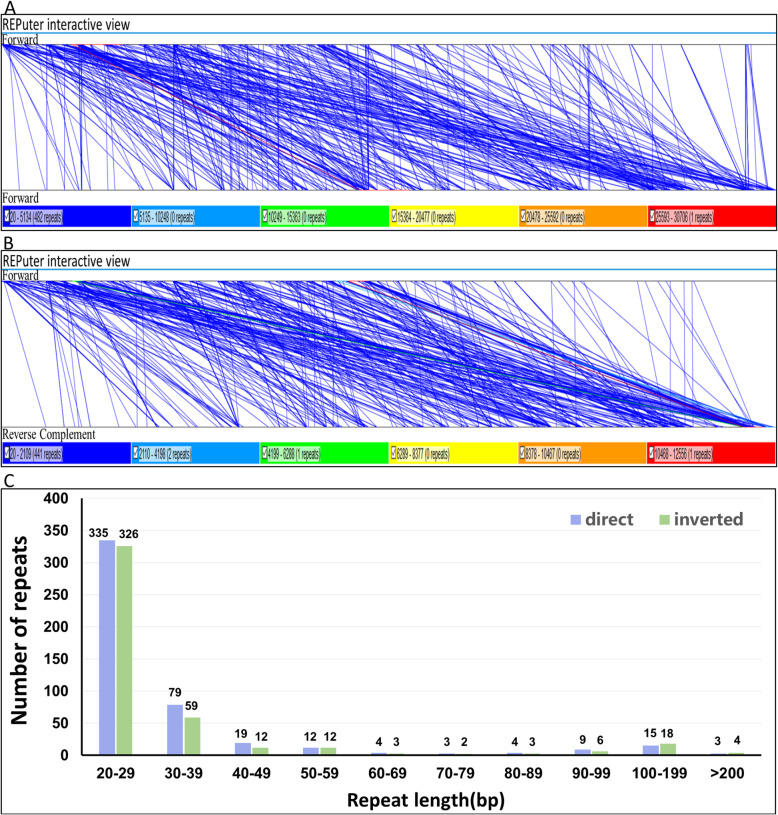

Microsatellites, or simple sequence repetitions (SSRs), are DNA fragments consisting of short units of sequence repetition of 1–6 base pairs in length [26]. The uniqueness and the value of microsatellites are due to their polymorphism, codominant inheritance, relative abundance, extensive genome coverage, and simplicity in PCR detection [27]. SSRs in the mt genome of S. glauca were identified with Tandem Repeats Finder software [28]. As a result, 361 SSRs were found in the mt genome of S. glauca, and the proportion of different forms were shown in Figure S2. SSRs in monomer and dimer forms accounted for 78.67% of the total SSRs present. Adenine (A) monomer repeats represented 46.28% (56) of 121 monomer SSRs, and AT repeat was the most frequent type among the dimeric SSRs, accounting for 58.15%. There are only two hexameric SSRs presented in S. glauca mt genome, located between nad4L and cox2, and between trnQ-UUG and trnM-CAU. The specific locations of pentamer and hexamer are shown in Table 2. Tandem repeats, also named satellite DNA, refer to the core repeating units of about 1 to 200 bases, repeated several times in tandem. They are widely found in eukaryotic genomes and in some prokaryotes [29]. As shown in Table 3, a total of 12 tandem repeats with a matching degree greater than 95% and a length ranging from 13 bp to 38 bp were present in the mt genome of S. glauca. The non-tandem repeats in S. glauca mt genome were also detected using REPuter software [30]. As a result, 928 repeats with the length equal to or longer than 20 were observed, of which 483 were direct, and 445 were inverted. The longest direct repeat was 30,706 bp, while the longest inverted repeat was 12,556 bp (Supplementary data sheet 1). The length distribution of the direct and inverted repeats are shown in Fig. 2. It is shown that the 20–29 bp repeats are most abundant for both repeat types.

Table 2.

Distribution of penta and hexa SSRs in S. glauca mt genome

| No. | Type | SSR | Start | End | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | pentamer | (tatac) × 3 | 3006 | 3020 | cox1 |

| 2 | pentamer | (agaat) × 3 | 49,581 | 49,595 | nad7 |

| 3 | pentamer | (taagt) × 3 | 78,725 | 78,739 | IGS (nad7,trnI) |

| 4 | pentamer | (ggaaa) × 3 | 107,921 | 107,935 | IGS (trnQ-UUG,trnM-CAU) |

| 5 | pentamer | (cgggc) × 3 | 139,703 | 139,717 | IGS (nad2,nad9) |

| 6 | pentamer | (cttct) × 3 | 168,170 | 168,184 | IGS (trnW-CCA,atp1) |

| 7 | pentamer | (tcttg) × 3 | 201,546 | 201,560 | IGS (trnV-GAC,trnA-UGC) |

| 8 | pentamer | (agaat) × 3 | 225,057 | 225,071 | nad7 |

| 9 | pentamer | (ttctt) × 3 | 316,091 | 316,105 | IGS (trnF-GAA.trnS-UGU) |

| 10 | pentamer | (actag) × 3 | 330,081 | 330,095 | matR |

| 11 | pentamer | (caaaa) × 3 | 388,600 | 388,614 | IGS (atp8,atp9) |

| 12 | pentamer | (agaaa) × 3 | 401,486 | 401,500 | IGS (atp9, rrnS) |

| 13 | hexamer | (caaaat) × 3 | 92,262 | 92,279 | IGS (nad4L, cox2) |

| 14 | hexamer | (tagaaa) × 3 | 106,488 | 106,505 | IGS (trnQ-UUG, trnM-CAU) |

Table 3.

Distribution of perfect tandem repeats in S. glauca mt genome

| No. | Size | Repeat sequence | Copy | Percent Matches | Start | End |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 | TACTGTAGC | 4 | 96 | 37,660 | 37,694 |

| 9 | TTGTAGTTT | 3 | 100 | 37,689 | 37,714 | |

| 3 | 32 | CCATACTTGTTCCAAGTAAGTGAATTGCATTA | 6 | 99 | 48,018 | 48,212 |

| 4 | 31 | GAGACAAGTCTAGTATAGACGCAGGGTCGAA | 5 | 98 | 104,348 | 104,524 |

| 5 | 38 | TTTCGGAAGTTTTATCCTATAAGAATTGGCTTTTCCTT | 2 | 95 | 168,613 | 168,711 |

| 6 | 13 | TCTAATAGAAAAT | 2 | 100 | 201,473 | 201,497 |

| 7 | 16 | AATGTGTATTATCCAT | 2 | 100 | 294,569 | 294,601 |

| 8 | 18 | ATATCGTCACTAGCATCA | 2 | 100 | 296,770 | 296,808 |

| 9 | 9 | ATCGATGAT | 3 | 100 | 297,459 | 297,484 |

| 10 | 18 | AGTCTATCAACGCTACTG | 2 | 100 | 335,715 | 335,749 |

| 11 | 9 | TGAAGTTAT | 3 | 100 | 394,462 | 394,486 |

| 12 | 32 | GGTAATGCCAATTCACTTACTTGGAACAAGTAT | 6 | 99 | 454,228 | 454,422 |

Fig. 2.

The repeats in S. glauca mt genome. a The synteny between the mt genome and its forward copy showing the direct repeats. b The synteny between the mt genome and its reverse complementary copy showing the inverted repeats. c The length distribution of reverse and inverted repeats in S. glauca mt genome. The number on the histograms represents the repeat number of designated lengths shown on the horizontal axis

The prediction of RNA editing

RNA editing refers to the addition, loss, or conversion of the base in the coding region of the transcribed RNA [31], found in all eukaryotes, including plants [32]. In chloroplast and mitochondrion, the conversion of specific cytosine into uridine alters the genomic information [33]. This process improves protein preservation in plants by modifying codons. Without the support of the proteomics data, it is impossible to detect accurate RNA editing. However, Mower’s software PREP could be used to computationally predict the RNA edit site [34]. In this analysis, 216 RNA editing sites within 26 protein-coding genes (Table 4) were predicted in the mt genome of S. glauca, using PREP-MT program (Fig. 3). Among those protein-coding genes, cox1 does not have any editing site predicted, while ccmB has the most editing sites predicted (29). Of those editing sites, 35.19% (76) were located at the first position of the triplet codes, 63.89% (138) occurred with the second base of the triplet codes. And there was a particular editing case in which the first and second positions of the triplet codes were edited, resulting in an amino acid change from the original proline (CCC) to phenylalanine (TTC). After the RNA editing, the hydrophobicity of 42.13% of amino acids did not change. However, 45.83% of the amino acids were were predicted to change from hydrophilic to hydrophobic, while 11.11% were predicted to change from hydrophobic to hydrophilic. The RNA editing might lead to the premature termination of protein-coding genes, and this phenomenon is likely to occur with atp4 and atp9 in S. glauca mt genome. Our results also showed that the amino acids of predicted editing codons showed a leucine tendency after RNA editing, which is supported by the fact that the amino acids of 47.69% (103 sites) of the edits were converted to leucine (Table 4).

Table 4.

Prediction of RNA editing sites

| Type | RNA -editing | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| hydrophobic | CCA (P) = > CTA (L) | 20 | 31.02% |

| CCG (P) = > CTG (L) | 14 | ||

| CCC (P) = > CTC (L) | 7 | ||

| CCT (P) = > CTT (L) | 6 | ||

| CCC (P) = > TTC (F) | 2 | ||

| GCC (A) = > GTC (V) | 3 | ||

| GCG (A) = > GTG (V) | 2 | ||

| GCT (A) = > GTT (V) | 1 | ||

| GCA (A) = > GTA (V) | 1 | ||

| CTT (L) = > TTT (F) | 8 | ||

| CTC (L) = > TTC (F) | 3 | ||

| hydrophilic | CAT (H) = > TAT (Y) | 8 | 11.11% |

| CAC (H) = > TAC (Y) | 4 | ||

| CGT (R) = > TGT (C) | 10 | ||

| CGC (R) = > TGC (C) | 2 | ||

| hydrophobic-hydrophilic | CCT (P) = > TCT (S) | 9 | 11.11% |

| CCA (P) = > TCA (S) | 8 | ||

| CCC (P) = > TCC (S) | 7 | ||

| hydrophilic-hydrophobic | CGG (R) = > TGG (W) | 15 | 45.83% |

| TCC (S) = > TTC (F) | 11 | ||

| TCT (S) = > TTT (F) | 9 | ||

| TCA (S) = > TTA (L) | 37 | ||

| TCG (S) = > TTG (L) | 19 | ||

| ACC (T) = > ATC (I) | 3 | ||

| ACT (T) = > ATT (I) | 2 | ||

| ACA (T) = > ATA (I) | 1 | ||

| ACG (T) = > ATG (M) | 2 | ||

| hydrophilic-stop | CAA (Q) = > TAA (X) | 1 | 0.93% |

| CGA (R) = > TGA (X) | 1 |

Fig. 3.

The distribution of RNA-editing sites in S. glauca mt protein-coding genes. The gray bars represent the number of RNA-editing sites of each gene

DNA migration from chloroplast to mitochondria

Thirty-two fragments with a total length of 26.87 kb were observed to be migrated from cp genome to mt genome in S. glauca, accounting for 5.18% of the mt genome. There are 8 annotated genes located on those fragments, all of which are tRNA genes, namely trnA-UGC, trnF-GAA, trnH-GUG, trnI-GAU, trnR-ACG, trnM-CAU, trnN-GUU, and trnV-GAC. Our data also demonstrate that some chloroplast protein-coding genes, i.e. atpA, rrn16, rrn23, rpoC2, ndhA, psaB, and psbB migrated from cp to mitochondrion, even though most of them lost their integrities during evolution, and only partial sequences of those genes could be found in the mt genome nowadays (Table 5). The different destinations of transferred protein-coding genes and tRNA genes suggested that tRNA genes are much more conserved in the mt genome than the protein-coding genes, indicating their indispensable roles in mitochondria.

Table 5.

Fragments transferred from chloroplast to mitochondria in S. glauca

| Alignment length | Identity% | Mismatches | Gap opens | mt start | mt end | cp start | cp end | Gene | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3954 | 95.726 | 82 | 20 | 295,697 | 299,575 | 90,318 | 86,377 | |

| 2 | 3527 | 98.469 | 16 | 10 | 207,557 | 211,072 | 99,899 | 103,398 | trnA-UCG |

| 3 | 3527 | 98.441 | 16 | 11 | 468,275 | 471,789 | 128,572 | 132,071 | |

| 4 | 3142 | 97.581 | 18 | 15 | 292,489 | 295,603 | 93,422 | 90,312 | trnI-GAU |

| 5 | 2545 | 96.149 | 35 | 19 | 465,776 | 468,283 | 126,021 | 128,539 |

trnN-GUU, trnR-ACG |

| 6 | 2546 | 95.915 | 39 | 24 | 211,064 | 213,571 | 103,431 | 105,949 | |

| 7 | 2031 | 99.015 | 8 | 2 | 199,446 | 201,472 | 133,093 | 135,115 | trnV-GAC |

| 8 | 1063 | 93.509 | 20 | 12 | 201,516 | 202,548 | 96,852 | 95,809 | |

| 9 | 533 | 94.934 | 21 | 4 | 310,145 | 310,671 | 47,809 | 48,341 | trnF-GAA |

| 10 | 427 | 97.424 | 11 | 0 | 246,135 | 246,561 | 33,914 | 33,488 | |

| 11 | 427 | 97.424 | 11 | 0 | 70,659 | 71,085 | 33,914 | 33,488 | |

| 12 | 388 | 96.392 | 14 | 0 | 370,829 | 371,216 | 19,553 | 19,940 | |

| 13 | 351 | 95.442 | 16 | 0 | 438,325 | 438,675 | 118,358 | 118,008 | ndhAa |

| 14 | 279 | 95.341 | 13 | 0 | 307,665 | 307,943 | 71,873 | 71,595 | psbBa |

| 15 | 248 | 93.952 | 15 | 0 | 14,593 | 14,840 | 10,031 | 9784 | atpAa |

| 16 | 888 | 73.649 | 181 | 39 | 407,200 | 408,058 | 97,374 | 98,237 | rrn16a |

| 17 | 157 | 98.726 | 2 | 0 | 404,203 | 404,359 | 42,089 | 41,933 | |

| 18 | 289 | 85.121 | 16 | 10 | 309,891 | 310,153 | 46,981 | 47,268 | |

| 19 | 340 | 79.706 | 48 | 15 | 145,392 | 145,717 | 64,797 | 64,465 | trnW-CCAb |

| 20 | 111 | 96.396 | 4 | 0 | 349,247 | 349,357 | 97,265 | 97,155 | |

| 21 | 86 | 96.512 | 3 | 0 | 138,006 | 138,091 | 105,510 | 105,425 | trnN-GUU |

| 22 | 78 | 97.436 | 2 | 0 | 117,112 | 117,189 | 79 | 2 | trnH-GUG |

| 23 | 77 | 96.104 | 2 | 1 | 309,789 | 309,865 | 46,566 | 46,641 | |

| 24 | 76 | 93.421 | 5 | 0 | 114,384 | 114,459 | 51,243 | 51,168 | trnM-CAU |

| 25 | 79 | 92.405 | 6 | 0 | 353,124 | 353,202 | 141,760 | 141,838 | |

| 26 | 56 | 98.214 | 1 | 0 | 248,777 | 248,832 | 37,491 | 37,436 | psaBa |

| 27 | 56 | 98.214 | 1 | 0 | 73,301 | 73,356 | 37,491 | 37,436 | |

| 28 | 45 | 97.778 | 1 | 0 | 274,465 | 274,509 | 16,239 | 16,195 | rpoC2a |

| 29 | 42 | 97.619 | 1 | 0 | 239,555 | 239,596 | 101,136 | 101,095 | rrn23a |

| 30 | 42 | 97.619 | 1 | 0 | 64,079 | 64,120 | 130,834 | 130,875 | |

| 31 | 42 | 97.619 | 1 | 0 | 239,555 | 239,596 | 130,834 | 130,875 | |

| 32 | 61 | 88.525 | 4 | 3 | 353,019 | 353,077 | 96,110 | 96,169 | |

| Total | 27,513 |

Notes: Lowercase a indicates the partial sequence found in mt genome. Lowercase b indicates the mt-derived genes

Phylogenetic analysis within higher plant mt genomes

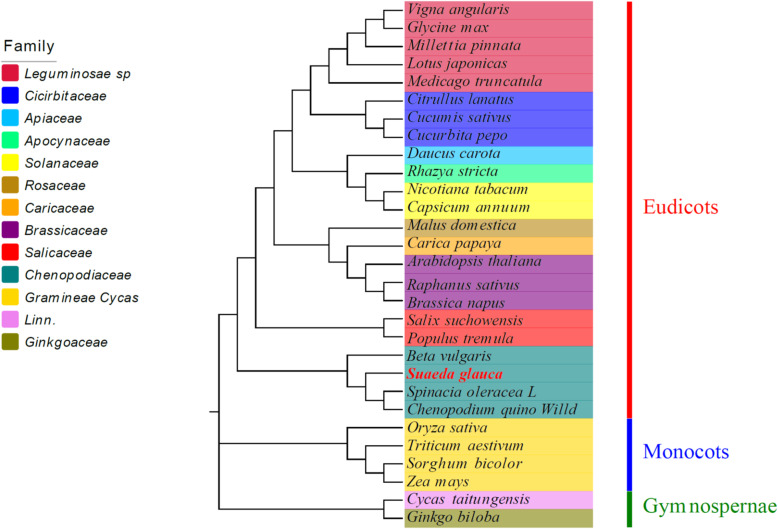

To understand the evolutionary status of S. glauca mt genome, the phylogenetic analyses was performed on S. glauca together with other 28 species, including 22 eudicots, 4 monocots, and 2 gymnosperms (designated as outgroups). Abbreviations and the accession number of mt genomes investigated in this study are listed in Table S3. A phylogenetic tree was obtained based on an aligned data matrix of 23 conserved protein-coding genes from these species, as shown in Fig. 4. The phylogenetic tree strongly supports the separation of eudicots from monocots and the separation of angiosperms from gymnosperms. Moreover, the taxa from 13 families (Leguminosae, Cucurbitaceae, Apiaceae, Apocynaceae, Solanaceae, Rosaceae, Caricaceae, Brassicaceae, Salicaceae, Chenopodiaceae, Gramineae, Cycadaceae, and Ginkgoaceae) were well clustered. The order of taxa in the phylogenetic tree was consistent with the evolutionary relationships of those species, indicating the consistency of traditional taxonomy with the molecular classification. Based on the phylogenetic relationships among the 29 species, different groups of plants were selected for further comparative analysis.

Fig. 4.

The phylogenetic relationships of S. glauca with other 28 plant species. The Neighbor-Joining tree was constructed based on the sequences of 23 conserved protein-coding genes. Colors indicate the families that the specific species belongs

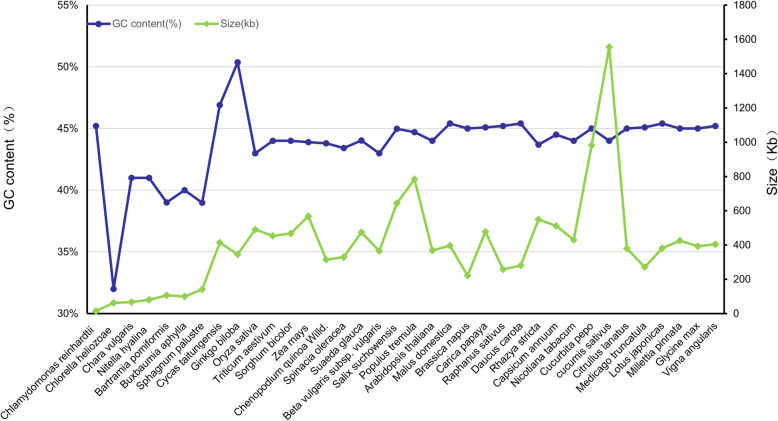

The comparison of mt genome size and GC content between S. glauca and other species

The size and GC content are the primary characteristics of an organelle genome. We compared the size and GC content of S. glauca with other 35 green plants, including 4 phycophyta, 3 bryophytes, 2 gymnosperms, 4 monocots, and 22 dicots. The abbreviations of species names of those plants and the accession numbers of their mt genomes are listed in Table S3. As shown in Fig. 5, the sizes of mt genomes varied from 15,758 bp (C. reinhardtii) to 1,555,935 bp (C. sativus). The sizes of mt genomes of phycophyta and bryophytes were generally smaller compared to land plants, while that of S. glauca (474,330 bp) has an average size. Similarly, the GC contents of the mt genomes were also variable, ranging from 32.24% in S. palustre to 50.36% in G. biloba. In general, the GC contents of angiosperms, including monocots and dicots, are larger than those of bryophytes but smaller than those of gymnosperms, suggesting that the GC contents frequently changed after the divergence of angiosperms from bryophytes and gymnosperms. Interestingly, our results also showed that the GC contents fluctuate widely in phycophyta. In contrast, the GC contents in angiosperms were much conserved during the evolution, although their genome sizes varied tremendously.

Fig. 5.

The sizes and GC contents of 36 mt plant genomes. The blue dots represent the GC content of the taxa, and the blue trendline shows the variation of GC content across the different taxa. The green dots represent the genome size, and the trendline shows the variation of GC content

Comparison of genome organization with ten green plant mt genomes

The S. glauca mt genome organization was extensively investigated for protein-coding genes, cis-spliced introns, rRNAs tRNAs, and non-coding regions. It was further compared with 10 other taxa, including 3 plants from Chenopodiaceae. As shown in Table 6, protein-coding genes and cis-introns regions represent 5.00% and 3.92% of the whole S. glauca mt genome sequence, respectively. In comparison, the proportions of rRNA and tRNA regions represent only 1.17% and 0.47%, respectively. The other three plants from Chenopodiaceae have similar proportions of protein-coding genes, slightly higher than that of S. glauca. However, the proportions of coding regions were significantly different across families, probably due to the different mt genome sizes.

Table 6.

Organization of mt genomes of S. glauca and other ten green plants

| Plant species | Family | Coding regions (%) | Non-coding regions (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-coding genes | Cis-spliced introns | rRNAs | tRNAs | |||

| G. biloba | Ginkgoaceae | 9.95 | 11.31 | 1.44 | 0.50 | 76.80 |

| Z. mays | Gramineae | 6.06 | 4.06 | 0.99 | 0.28 | 88.61 |

| B. vulgaris | Chenopodiaceae | 7.63 | 3.62 | 3.30 | 0.54 | 84.90 |

| C. quinoa Willd. | Chenopodiaceae | 8.47 | 4.89 | 1.71 | 0.51 | 84.43 |

| S. oleracea | Chenopodiaceae | 8.37 | 5.69 | 1.64 | 0.52 | 83.79 |

| S. glauca | Chenopodiaceae | 5.00 | 3.92 | 1.17 | 0.47 | 89.44 |

| S. suchowensis | Salicaceae | 4.68 | 4.21 | 0.83 | 0.27 | 90.01 |

| A. thaliana | Brassicaceae | 8.53 | 7.99 | 1.42 | 0.54 | 81.52 |

| N. tabacum | Solanaceae | 7.11 | 14.47 | 2.05 | 0.40 | 76.00 |

| C. papaya | Caricaceae | 7.12 | 6.27 | 1.14 | 0.30 | 85.17 |

| G. max | Leguminosae | 8.48 | 8.09 | 1.31 | 0.35 | 81.77 |

Gene duplication and lost in mt genomes of Chenopodiaceae plants

With the rapid development of sequencing technology, an increasing number of complete plant mt genomes were assembled and reported recently, facilitating the comparison analysis of the mt genome features among multiple plant species [35]. As described by Richardson et al., the mt genomes in plants vary considerably in size, gene content, and gene order [21]. The Chenopodiaceae plants have a relatively strong tolerance to biotic stress, especially to salt. Four mt genomes from this family: C. quinoa willd, S. oleracea, B. vulgaris, and S. glauca are already available. To understand whether those four plants have the same gene contents, the protein-coding genes from those 4 mt genomes were compared. As shown in Table S4, the specific gene duplication and gene loss were observed in different species. For example, nad7 was duplicated in S. glauca mt genome, and nad1 and rps7 were duplicated in B. vulgaris mt genome. The C. quinoa has the most intact mt genome, with only one gene (sdh4) loss, while atp4 and ccmC from B. vulgaris ssp, and nad1 and shh4 from S. oleracea were also lost. However, with five genes, nad4, nad6, rps4, rps13, and tatC, gene loss appears more frequent in the mt genome of S. glauca.

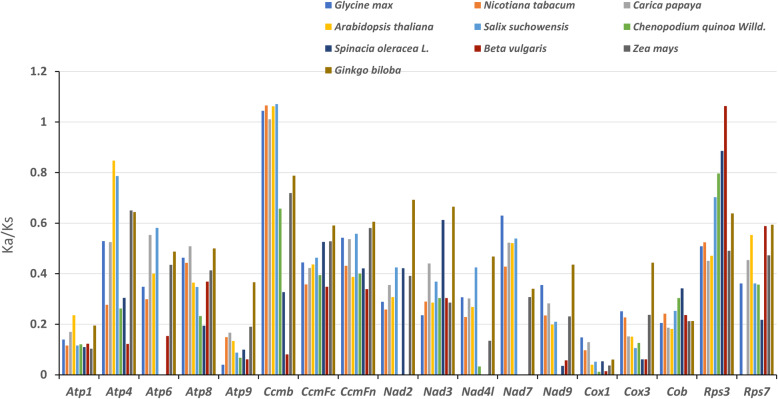

The substitution rates of protein-coding genes

The calculation of non-synonymous substitutions (Ka) and synonymous substitutions (Ks) is of great significance for the reconstruction of phylogeny and the understanding of evolutionary dynamics of protein-coding sequences in closely related species [36]. In genetics, Ka/Ks value could be used to determine whether selective pressure existed on a specific protein-coding gene during evolution: Ka/Ks > 1, positive selection; Ka/Ks = 1, neutral selection; and Ka/Ks < 1, negative selection [37]. The 18 protein-coding genes from S. glauca mt genome were compared with the mt genomes of 10 species, A. thaliana (NC_037304), B. vulgaris (NC_015099), C. papaya (NC_012116), G. max (NC_020455), S. suchowensis (NC_029317), Z. mays (NC_008332), C. quinoa Willd (NC_041093), S. oleracea (NC_035618), N. icotiana tabacum (NC_006581), and G. biloba (NC_027976) for Ka/Ks calculation. As shown in Fig. 6, the Ka/Ks values of S. glauca ccmB compared to G. max, S. suchowensis, A. thaliana, N. tabacum, and C. papaya were higher than 1, suggesting a positive selection occurred during evolution. However, the Ka/Ks values of most proteins in S. glauca were less than 1 compared to the other plant species, indicating the negative selections of those genes during evolution. Taken together, we conclude that the mt genes are highly conserved during the evolutionary process in green plants.

Fig. 6.

The Ka/Ks values of 18 protein-coding genes of S. glauca versus ten species

Discussion

Mitochondria are the powerhouse of the plants that produce the required energy to carry out life processes. Plant mitochondria possess more complex genomes than animals, with extensive size variations, sequence arrangements, repeat content, and a highly conserved coding sequence [38]. Understanding the mt genome structure is required to unravel its function, replication, inheritance, and evolutionary trajectories [38]. In the current study, we studied the characteristics of the mt genome of S. glauca, a crucial salt tolerance plant with great value as a food source and phytoremediation agent. According to the reported data, most of the mt genome is circular, and few mt genomes are linear such as the mt genome of Polytomella parva [39, 40]. The mt genome of S. glauca reported in this study is circular with 474,330 bp in size.

The repeat sequences widely exist in the mt genome, and these repeats include tandem, short, and large repeats [41, 42]. Previous studies have shown that repeats in mitochondria are vital for intermolecular recombination. For this reason, the repeat sequences play a pivotal role in shaping the mt genome [43]. In this study, the SSRs, longer tandem repeats, and non-tandem repeats were intensively investigated (Fig. 2). The mt genome of S. glauca harbors abundant repeat sequences that might indicate that the intermolecular recombination frequently happens in the mt genome, which dynamically changes the sequence and conformation during the evolution. We also investigated the genome structure and organization of S. glauca in comparison with other land plants. Conclusively, the mt genome characteristics of S. glauca were consistent with those of other terrestrial green plants.

RNA-editing is a posttranscriptional process that occurs in the cp and mt genomes of higher plants, contributing to the better folding of proteins [44]. Investigating the RNA-editing sites helps to understand the gene expression of the cp and mt genes in plants. Previous studies reported approximately 441 RNA-editing sites within 36 genes in Arabidopsis and 491 RNA-editing sites within 34 genes in rice [39, 45]. In this study, 216 RNA-editing sites within 26 genes were identified. The identification of RNA editing sites provides essential clues for predicting gene functions with novel codons. As the cytoplasmic genome, migration of cp DNA to the mt genome occurred during the plant evolution. We found that 32 fragments were transferred from the cp genome to mt with 8 integrated genes, which are all tRNA genes (Table 5). Transfer of tRNA genes from cp to mt is common in angiosperms [44].

Further, we have analyzed the phylogenetic relationship of S. glauca with representative taxa based on the mt genome information. The resulted phylogenetic tree reflected a clear taxonomic relationship among the taxa. We also analyzed GC content of the mt genome in S. glauca along with other green plants. The result supports the conclusion that GC content is highly conserved in higher plants. The Ka/Ks analysis and the comparison of genome features with other plant’s mt genomes provide a comprehensive understanding of plant mt evolution. Generally, most of the results in this study were consistent with previous reports. The genes that undergone neutral and negative selections were also identified in S. glauca. However, most of the protein-coding genes in S. glauca mt had negative selection compared with other selected species, which is consistent with the previous studies, indicating that the protein-coding genes in the mt genome are conserved across the land plants. The ccmB gene is the only gene that underwent positive selection during the evolution.

In crop plants, deciphering and understanding the mt genome is essential for plant breeding. Understanding of mt genome will set a foundation for the evolutionary analysis, cytoplasmic male sterility, and molecular biological information for plant breeding. Even though S. glauca is not a crop plant, its biological significance and edible values are being examined. As a halophytic model plant with prominent salt-tolerance, whose mt genome has not been reported, the accomplishment of the mt genome provides an opportunity to conduct further genomic studies in S. glauca. Therefore, our study provides essential background information for future understanding of this plant [44].

Conclusion

In this study, we assembled and annotated the mt genome of S. glauca and performed extensive analyses based on the DNA sequences and amino acid sequences of the annotated genes. The S. glauca mt genome is circular, with a length of 474,330 bp. 61 genes, including 27 protein-coding genes, 29 tRNA genes, and 5 rRNA genes, were annotated in the genome. The repeats sequences and RNA editing in S. glauca mt genome were analyzed subsequently. The gene conversation between mt and cp genome was also observed in S. glauca by detecting gene migration. Moreover, our result also indicates consistency in molecular and taxonomic classification, besides GC contents in angiosperms, were also found conserved despite their genome sizes that varied tremendously. The Ka/Ks analysis based on code substitution revealed that most of the coding genes had undergone negative selections, indicating the conservation of mt genes during the evolution. This study provides extensive information about the mt genome for S. glauca, facilitating deciphering the salt resistance mechanism in plants.

Methods

Plant growth conditions, DNA extraction, and sequencing

The S. glauca seeds were provided by Chunyin Zhang (Yancheng Lvyuan Salt Soil Agricultural Technology Co. Ltd., Yancheng, Jiangsu, Southeast China, http://www.ychpz.com/index.asp). Seeds were treated with 0.03% Gibberellin for 24 h and germinated at 25 °C in a growth chamber. The seedlings were planted at 25 °C in the greenhouse with 16/8 h of light-dark photoperiod cycle. Leaves from about 40 days old plants were used for DNA isolation using CTAB method [46]. The DNA sample quality was examined with agarose-gel electrophoresis, and the concentration was measured using Nanodrop instrument (2000c UV-Vis). The qualified samples were sent to the Annoroad Gene Technology (http://www.annoroad.com/) for Pacbio sequencing.

Assembly and annotation of the mitochondrial genome

The mitochondrial sequences of S. glauca were selected with blast software using the conserved mitochondrial sequences of Beta vulgaris, Spinacia oleracea, and Chenopodium quinoa Willd as queries. The mt genome was assembled using Canu v1.8 with the selected reads [47]. The assembled contigs were polished (Pilon v 1.18) with Illumina reads to correct read errors. The GE-Seq tool on MPI-MP CHLOROBX website [48] (https://chlorobox.mpimp-golm.mpg.de) was used for the mt genome annotation using the mt genomes of the following species as references: Arabidopsis thaliana (NC_037304), Beta vulgaris (NC_002511), Brassica napus (NC_008285), Carica papaya (NC_012116), Chenopodium quinoa Willd (NC_041093), Daucus carota (NC_017855), Glycine max (NC_020455), Nicotiana tabacum (NC_006581), Spinacia oleracea. (NC_035618), and Salix suchowensis (NC_029317) as references. The threshold for protein search identity was 55%, and that of rRNA, tRNA, and DNA search identity was 85%. The annotation results from Ge-Seq were manually adjusted with Mega 7.0 [49]. The output genebank format file was manually confirmed, and the mitochondrial circular map was drawn using Organellar Genome DRAW (OGDRAW) [50].

Analysis of repeated sequences

Microsatellite identification tool was used to detect simple sequence repeats [51] (https://webblast.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/index.php). The repeats of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 bases with 8, 4, 4, 3, 3, and 3 repeats numbers, respectively, were identified in this analysis. The tandem repeats with > 6p repeat unit were detected using Tandem Repeats Finder v4.09 software [28] (http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.submit.options.html) with default parameters. The direct and inverted repeats were detected using REPuter software [30] (https://bibiserv.cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de/reputer) with the minimal repeat size set to 20 bp.

Chloroplast to mitochondrion DNA transformation and RNA editing analyses

DNA migration is common in plants and varies from species to species [52]. This phenomenon occurs during autophagy, gametogenesis, and fertilization [53]. The cp genome of S. glauca (NC_045302.1) was downloaded from NCBI Organelle Genome Resources Database. Blastn software on NCBI was used to identify the protein-coding and tRNA genes transferred from chloroplasts to mitochondria. Screening criteria were set as the matching rate ≥ 70%, E-value ≤ 1e − 10, and length ≥ 40. The editing sites in the mitochondrial RNA of S. glauca were revealed using the mt gene encoding proteins of plants as references. The analysis was conducted on the Plant Predictive RNA Editor (PREP) suite [34] (http://prep.unl.edu/) with a cut off value of 0.2.

Phylogenetic tree construction and Ka/Ks analysis

The conserved protein-coding genes from mt genomes of S. glauca and other 28 taxa were used for phylogenetic tree construction. The mt genomes were downloaded from NCBI, and the conserved protein-coding genes (atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8, atp9, ccmB, ccmC, ccmFc, ccmFn, cob, cox1, cox2, cox3, matR, nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4L, nad5, nad6, nad7, and nad9) were extracted using TBtool software [54], and then aligned using Muscle software [55]. Subsequently, a Neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was constructed by Mega 7.0 software using the Poisson model with a bootstrap of 1000 [49]. C. taitungensis and G. biloba were designated as the outgroup in this analysis. The synonymous (Ks) and non-synonymous (Ka) substitution rates of the protein-coding genes in S. glauca mt genome were analyzed using ten representative species (Table S3) as references. In this analysis, Mega 7.0 [49] was used for sequence alignment, and DNAsP v.6.12 [56] was used to calculate Ka/Ks.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. The secondary structure of tRNA. A and B are two different structures of trnM-CAU. Figure S2. The distribution of SSRs in S. glauca mt genome. The colors represent different types of SSRs. The area on the pie chart indicates the percentages of different SSR types. Table S1. The mt homologous genes in S. glauca, A. thaliana, H. sapiens, and S. cerevisiae. Table S2. The stop codes of protein-coding genes in S. glauca mt genome. Table S3. The abbreviations and NCBI accession numbers of mt genomes used in this study. Table S4. Protein-coding genes annotated in S. gluaca mt genome in comparison to related species.

Additional file 2: The sequence and annotation of S. glauca mt genome.

Additional file 3: Additional data sheet 1. The distribution of repeats in the S. glauca mt genome.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chunyin Zhang for providing the original seeds of Suaeda glauca.

Abbreviations

- S. glauca

Suaeda glauca

- mt

mitochondria

- cp

chloroplast

Authors’ contributions

YC and YQ concieved and designed the research. XH, YW, LY, CS, KY, QZ, ZL, FD and LC performed the experiments. MA helped with a critical discussion on the work. XH and YC wrote the paper. SP, MA, and YQ revised the paper. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Y.C. is supported by a grant from National Natural Science Foundation, China (31671267). A grant from the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2018 J01704). Y.Q. is supported by a grant from National Natural Science Foundation, China (31970333) and Guangxi Distinguished Experts Fellowship. The Funding bodies were not involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The sequence and annotation of S. glauca mt genome was provided as Additional file 2. The accession number in Gene Banks is MW561632.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yan Cheng and Xiaoxue He contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Cai X, Jiao C, Sun H, Wang X, Xu C, Fei Z, Wang Q. The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of spinach, Spinacia oleracea L. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2017;2(1):339–340. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2017.1334518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maughan PJ, Chaney L, Lightfoot DJ, Cox BJ, Tester M, Jellen EN, Jarvis DE. Mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes provide insights into the evolutionary origins of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36693-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubo T, Nishizawa S, Sugawara A, Itchoda N, Estiati A, Mikami T. The complete nucleotide sequence of the mitochondrial genome of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) reveals a novel gene for tRNACys (GCA) Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(13):2571–2576. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.13.2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang W, Li W, Niu Z, Xie Z, Liu X. Interactive effect of salinity and drought on the germination of dimorphic seeds of suaeda salsa. In: Sabkha Ecosystems. Dordrecht: Springer; 2014 (47), pp. 143–53.

- 5.Song J, Fan H, Zhao Y, Jia Y, Du X, Wang B. Effect of salinity on germination, seedling emergence, seedling growth and ion accumulation of a euhalophyte Suaeda salsa in an intertidal zone and on saline inland. Aquat Bot. 2008;88(4):331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2007.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang W, Li Z-G, Qiao H-L, Li C-Z, Liu X-J. Interactive effect of sodium chloride and drought on growth and osmotica of Suaeda salsa. Chin J Eco Agric. 2008;16:173–178. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Li M, Yang H, Li X, Cui Z. Physiological responses of Suaeda glauca and Arabidopsis thaliana in phytoremediation of heavy metals. J Environ Manag. 2018;223:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shtolz N, Mishmar D. The mitochondrial genome–on selective constraints and signatures at the organism, cell, and single mitochondrion levels. Front Ecol Evol. 2019;7:342. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2019.00342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavalier-Smith T. The origin of nuclei and of eukaryotic cells. Nature. 1975;256(5517):463–468. doi: 10.1038/256463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry S. Endosymbiosis and the design of eukaryotic electron transport. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics. 2003;1606(1–3):57–72. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(03)00084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Archibald JM. Origin of eukaryotic cells: 40 years on. Symbiosis. 2011;54(2):69–86. doi: 10.1007/s13199-011-0129-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonora M, De Marchi E, Patergnani S, Suski J, Celsi F, Bononi A, Giorgi C, Marchi S, Rimessi A, Duszyński J. Tumor necrosis factor-α impairs oligodendroglial differentiation through a mitochondria-dependent process. Cell Death Differentiation. 2014;21(8):1198–1208. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Loo G, Saelens X, Van Gurp M, MacFarlane M, Martin S, Vandenabeele P. The role of mitochondrial factors in apoptosis: a Russian roulette with more than one bullet. Cell Death Differentiation. 2002;9(10):1031–1042. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroemer G, Reed JC. Mitochondrial control of cell death. Nat Med. 2000;6(5):513–519. doi: 10.1038/74994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rehman J, Zhang HJ, Toth PT, Zhang Y, Marsboom G, Hong Z, Salgia R, Husain AN, Wietholt C, Archer SL. Inhibition of mitochondrial fission prevents cell cycle progression in lung cancer. FASEB J. 2012;26(5):2175–2186. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-196543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogihara Y, Yamazaki Y, Murai K, Kanno A, Terachi T, Shiina T, Miyashita N, Nasuda S, Nakamura C, Mori N. Structural dynamics of cereal mitochondrial genomes as revealed by complete nucleotide sequencing of the wheat mitochondrial genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(19):6235–6250. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace DC, Singh G, Lott MT, Hodge JA, Schurr TG, Lezza A, Elsas LJ, Nikoskelainen EK. Mitochondrial DNA mutation associated with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Science. 1988;242(4884):1427–1430. doi: 10.1126/science.3201231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon C, Frati F, Beckenbach A, Crespi B, Liu H, Flook P. Evolution, weighting, and phylogenetic utility of mitochondrial gene sequences and a compilation of conserved polymerase chain reaction primers. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1994;87(6):651–701. doi: 10.1093/aesa/87.6.651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knoop V. The mitochondrial DNA of land plants: peculiarities in phylogenetic perspective. Curr Genet. 2004;46(3):123–139. doi: 10.1007/s00294-004-0522-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergthorsson U, Richardson AO, Young GJ, Goertzen LR, Palmer JD. Massive horizontal transfer of mitochondrial genes from diverse land plant donors to the basal angiosperm Amborella. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;101(51):17747–17752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408336102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson AO, Rice DW, Young GJ, Alverson AJ, Palmer JD. The “fossilized” mitochondrial genome of Liriodendron tulipifera: ancestral gene content and order, ancestral editing sites, and extraordinarily low mutation rate. BMC Biol. 2013;11(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skippington E, Barkman TJ, Rice DW, Palmer JD. Miniaturized mitogenome of the parasitic plant Viscum scurruloideum is extremely divergent and dynamic and has lost all nad genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112(27):E3515–E3524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504491112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sloan DB, Alverson AJ, Chuckalovcak JP, Wu M, McCauley DE, Palmer JD, Taylor DR. Rapid evolution of enormous, multichromosomal genomes in flowering plant mitochondria with exceptionally high mutation rates. PLoS Biol. 2012;10(1):e1001241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu CL, Mullin BC. Physical characterization of mitochondrial DNA from cotton. Plant Mol Biol. 1989;13(4):467–468. doi: 10.1007/BF00015558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao X, Zhao Y, Kong X, Khan A, Zhou B. Complete sequence of kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus) mitochondrial genome and comparative analysis with the mitochondrial genomes of other plants. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17765-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Y-c L, Liu S, Liu D-C, Wei Y-X, Liu C, Yang Y-M, Tao C-G, Liu W-S. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of EST-SSR markers in blueberry (Vaccinium) and their cross-species transferability in Vaccinium spp. Sci Hortic. 2014;176:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.07.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powell W, Machray GC, Provan J. Polymorphism revealed by simple sequence repeats. Trends Plant Sci. 1996;1(7):215–222. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(96)86898-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(2):573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.GAO H, KONG J. Distribution characteristics and biological function of tandem repeat sequences in the genomes of different organisms. Zool Res. 2005;26(5):555–564. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, Giegerich R. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(22):4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brennicke A, Marchfelder A, Binder S. RNA editing. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1999;23(3):297–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1999.tb00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malek O, Lättig K, Hiesel R, Brennicke A, Knoop V. RNA editing in bryophytes and a molecular phylogeny of land plants. EMBO J. 1996;15(6):1403–1411. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schallenberg-Rüdinger M, Knoop V. Coevolution of organelle RNA editing and nuclear specificity factors in early land plants. Advances in Botanical Research, vol. 78. Elsevier, University of Birmingham, Academic Press; 2016, pp. 37–93.

- 34.Mower JP. The PREP suite: predictive RNA editors for plant mitochondrial genes, chloroplast genes and user-defined alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(suppl_2):W253–W259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei S, Wang X, Bi C, Xu Y, Wu D, Ye N. Assembly and analysis of the complete Salix purpurea L. (Salicaceae) mitochondrial genome sequence. SpringerPlus. 2016;5(1):1894. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-3521-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fay JC, Wu C-I. Sequence divergence, functional constraint, and selection in protein evolution. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2003;4(1):213–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.4.020303.162528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Z, Li J, Zhao XQ, Wang J, Wong KS, Yu J. KaKs_Calculator: calculating Ka and Ks through model selection and model averaging. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2006;4(4):259–263. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(07)60007-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kozik A, Rowan BA, Lavelle D, Berke L, Schranz ME, Michelmore RW, Christensen AC. The alternative reality of plant mitochondrial DNA: one ring does not rule them all. PLoS Genet. 2019;15(8):e1008373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Notsu Y, Masood S, Nishikawa T, Kubo N, Akiduki G, Nakazono M, Hirai A, Kadowaki K. The complete sequence of the rice (Oryza sativa L.) mitochondrial genome: frequent DNA sequence acquisition and loss during the evolution of flowering plants. Mol Gen Genomics. 2002;268(4):434–445. doi: 10.1007/s00438-002-0767-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith DR, Lee RW. Mitochondrial genome of the colorless green alga Polytomella capuana: a linear molecule with an unprecedented GC content. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25(3):487–496. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo W, Zhu A, Fan W, Mower JP. Complete mitochondrial genomes from the ferns Ophioglossum californicum and Psilotum nudum are highly repetitive with the largest organellar introns. New Phytol. 2017;213(1):391–403. doi: 10.1111/nph.14135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gualberto JM, Mileshina D, Wallet C, Niazi AK, Weber-Lotfi F, Dietrich A. The plant mitochondrial genome: dynamics and maintenance. Biochimie. 2014;100:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dong S, Zhao C, Chen F, Liu Y, Zhang S, Wu H, Zhang L, Liu Y. The complete mitochondrial genome of the early flowering plant Nymphaea colorata is highly repetitive with low recombination. BMC Genomics. 2018;19(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4368-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bi C, Paterson AH, Wang X, Xu Y, Wu D, Qu Y, Jiang A, Ye Q, Ye N: Analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the diploid cotton Gossypium raimondii by comparative genomics approaches. BioMed Res Int. 2016;2016(Article 5040598):1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Unseld M, Marienfeld JR, Brandt P, Brennicke A. The mitochondrial genome of Arabidopsis thaliana contains 57 genes in 366,924 nucleotides. Nat Genet. 1997;15(1):57–61. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doyle J. DNA protocols for plants-CTAB total DNA isolation. In: Molecular techniques in taxonomy. Berlin: Springer; 1991 (57), pp: 283–93.

- 47.Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 2017;27(5):722–736. doi: 10.1101/gr.215087.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tillich M, Lehwark P, Pellizzer T, Ulbricht-Jones ES, Fischer A, Bock R, Greiner S. GeSeq–versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(W1):W6–W11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Greiner S, Lehwark P, Bock R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3. 1: expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W59–W64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beier S, Thiel T, Münch T, Scholz U, Mascher M. MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(16):2583–2585. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang S, Wang Y, Lu J, Gai J, Li J, Chu P, Guan R, Zhao T. The mitochondrial genome of soybean reveals complex genome structures and gene evolution at intercellular and phylogenetic levels. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang CY, Ayliffe MA, Timmis JN. Direct measurement of the transfer rate of chloroplast DNA into the nucleus. Nature. 2003;422(6927):72–76. doi: 10.1038/nature01435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, Xia R. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020;13(8):1194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rozas J, Ferrer-Mata A, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Guirao-Rico S, Librado P, Ramos-Onsins SE, Sánchez-Gracia A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34(12):3299–3302. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. The secondary structure of tRNA. A and B are two different structures of trnM-CAU. Figure S2. The distribution of SSRs in S. glauca mt genome. The colors represent different types of SSRs. The area on the pie chart indicates the percentages of different SSR types. Table S1. The mt homologous genes in S. glauca, A. thaliana, H. sapiens, and S. cerevisiae. Table S2. The stop codes of protein-coding genes in S. glauca mt genome. Table S3. The abbreviations and NCBI accession numbers of mt genomes used in this study. Table S4. Protein-coding genes annotated in S. gluaca mt genome in comparison to related species.

Additional file 2: The sequence and annotation of S. glauca mt genome.

Additional file 3: Additional data sheet 1. The distribution of repeats in the S. glauca mt genome.

Data Availability Statement

The sequence and annotation of S. glauca mt genome was provided as Additional file 2. The accession number in Gene Banks is MW561632.