Abstract

Background

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrinopathy among young women. Insulin resistance is a key feature in the pathogenesis of PCOS; also high molecular weight adiponectin is a marker of insulin resistance. The aim of this study was to evaluate the insulin resistance, metabolic and androgenic profiles and high molecular weight adiponectin in obese and non-obese PCOS patients.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study in outpatient endocrinology clinics of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, 80 women aged 17–43 years old with PCOS were enrolled. Biochemical and hormonal assay was done on fasting blood sample on the third day of follicular phase.

Results

The individuals had a mean age of 28.39 ± 6.56 years, mean weight of 65.41 ± 12.59 Kg, mean BMI of 25.5 ± 4.9, and mean waist circumference of 88.0 ± 13.1 cm. Of all individuals 20% had frank insulin resistance with HOMA-IR > 3.8. Although the obese PCOS patients had lower levels of high molecular weight adiponectin (P = 0.03) than the normal weight PCOS individuals, the level of insulin and insulin resistance was not different in them (P = 0.13, 0.13). Patients with classic PCOS phenotype significantly had higher levels of insulin resistance and free androgen index (P < 0.001, 0.001). We found a significant correlation between the insulin level and free androgen index (correlation coefficient: 0.266 and P = 0.018) after adjusting for BMI.

Conclusion

This cross-sectional study showed a high incidence of insulin resistance in PCOS patients independent of obesity, and determined BMI related lower level of high molecular weight adiponectin in obese PCOS individuals. More detailed studies are warranted for evaluation of insulin resistance and its pathophysiologic role in PCOS.

Keywords: Polycystic ovary, Insulin, Adiponectin, Obesity

Background

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrinopathy among women in the reproductive age. The prevalence of PCOS varies between 10 and 15% [1]. Three criteria are used to define PCOS over the last decades: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria, Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AES-PCOS) criteria, and The Rotterdam criteria [2–4].

Obesity, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance are the most important metabolic abnormalities that affect PCOS patients. Hyperandrogenism, menstrual dysfunction, infertility, and hirsutism are the most common clinical symptoms in women with PCOS. In addition, the prevalence of dyslipidemia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases is higher in these patients than general population [5, 6].

Although the etiology of PCOS is still not well known [1], it seems that insulin resistance is a major pathophysiologic mechanism in developing clinical symptoms and other metabolic complications of PCOS [7]. Resistance to insulin leads to an increase in free androgen availability, and consequently alteration in follicular development and granulosa cell function [5, 8]. Increased insulin concentration in PCOS patients reduces the serum level of SHBG, which enhances the bioavailability of free testosterone level; also, these women have abnormal gonadotropin concentration and great androgen biosynthesis from the adrenal and ovaries, stimulated by high level of insulin [9].

Insulin resistance has a main role in the pathogenesis of PCOS independent of obesity [10], and there is possibility of considerable effect of hyperandrogenism on the insulin resistance in PCOS patients [11].

Various adipokines are secreted from the adipose tissue, which have different effects on insulin resistance. Some of these, such as visfatin can activate the insulin receptor and has insulin-like activity, but adiponectin has insulin-sensitizing effect [12]. Adiponectin, secreted from the adipocyte, is an abundant protein that exists as multimers including high molecular weight (HMW), medium-molecular-weight, and low-molecular-weight oligomers [13]. Although some studies showed the relationship between adiponectin and PCOS independent of BMI [13, 14], some other demonstrated that the adiponectin levels were negatively associated with BMI [1, 15]. These adipokines may be considered as markers of insulin resistance in PCOS patients irrespective of BMI.

We performed this study to evaluate and compare the level of insulin, insulin resistance, androgen, and HMWA between obese and non-obese women with PCOS and in four different PCOS phenotypes; in addition, we investigated the relationship between HMWA and the androgen level.

Methods

Subjects

The present study is a cross sectional investigation conducted from March 2016 to February 2017 in outpatient endocrinology clinics of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences in the south of Iran. Eighty women aged 17–43 years old diagnosed with PCOS (according to the Rotterdam criteria) [4] were enrolled in the study. Pregnant women, women with late onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia, hyperprolactinemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, Cushing syndrome, adrenal and ovarian tumor, and those using oral contraceptive pills, lipid lowering, antihypertensive, and antiandrogen agents were excluded.

A physician measured the participants’ weight and height. A standard scale was used to the nearest 0.1 kg (Seca, Germany), while the participant was wearing light clothing and was barefoot. We measured height to the nearest 0.5 cm with a wall-mounted meter while the participant was standing with no shoes. We also calculated the BMI by dividing the weight (in kilogram) by height per square meter. Finally, we measured the waist circumference to the nearest 0.1 cm just above the patient’s uppermost lateral border of the right ilium.

The patients were divided into 3 groups based on their BMI (less than 25, between 25 and 30, more than 30 Kg/m2). Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP) was measured in one arm in a sitting and standard position and recorded.

The patients were categorized into four different phenotypes according to their androgen level, history, and sonography. Phenotype 1: chronic anovulation and polycystic ovaries but no clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism; phenotype 2: hyperandrogenism and polycystic ovaries but ovulatory cycles; phenotype 3: hyperandrogenism and chronic anovulation but normal ovaries; and phenotype 4 (classic phenotype): hyperandrogenism, chronic anovulation, and polycystic ovaries [16].

Biochemical and hormonal assessment

Blood samples were obtained directly from all subjects from a cannulated vein on the third day of follicular phase after 8 h overnight fasting between 8:00–9:00 AM. We performed biochemical analysis for each individual. Fasting blood glucose, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, Insulin level (Insulin -I125- IRMA kit, Hungary), Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH), Prolactin, Luteinizing Hormone (LH) (I125-hLH IRMA kit, Hungary), Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) (I125- hFSH IRMA kit, Hungary), 17(OH) progesterone (ELISA, Germany), total testosterone (Microplate Enzyme Immunoassay kit, USA), Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (SHBG) (SHBG I125 IRMA, Hungary), free androgen index [(testosterone level/ SHBG)*100],dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEAS) (DHEA-SO4 /I125 Kit, Hungary), and High-molecular-weight adiponectin (HMWA) (quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique, USA) were measured. Insulin resistance was calculated by the homeostasis model (HOMA-IR) with the following formula: HOMA-IR = [fasting glucose (mg/dl) × fasting insulin (μU/ml))/22.5] and HOMA-IR index > 3.8 was considered as “high” with clear correlation with insulin resistance [17].

Statistical analysis

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed for normality of all continuous variables. The qualitative and quantitative data were described by frequency (percentage) and mean ± standard deviation (SD), respectively. Differences between the groups were evaluated using Student’s t-test and ANOVA for the quantitative variables with normal distribution, and Mann-Whitney U and kruskal-Wallis test for the variables without normal distribution. Pearson correlation was conducted to determine the relationships between the variables. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 22 for windows. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Data were collected from 80 PCOS individuals with a mean age of 28.39 ± 6.56 years, mean weight of 65.41 ± 12.59 Kg, mean waist circumference of 88.0 ± 13.3 cm, and mean hip circumference of 100.4 ± 11.5 cm. We found a mean BMI of 25.5 ± 4.9 kg/m2 (in the overweight range) in these patients. From these subjects, 39 (48.7%) had normal weight (BMI ≤24.9 Kg/m2), 26 (32.5%) were overweight (BMI = 25–29.9 Kg/m2), and 15 (18.8%) were obese (BMI ≥ 30 Kg/m2).

Mean level of HOMA-IR in these PCOS patients was 2.46 ± 1.30; 16 (20%) had frank insulin resistance with HOMA-IR > 3.8, and 15 (18.8%) had HOMA-IR 2.6–3.8.

From these individuals, 42.5% had PCOS phenotype1, 21.3% PCOS phenotype 2, 6.3% PCOS phenotype 3, and 30% of them had classic form of PCOS (phenotype 4). Table 1 shows anthropometric and biochemical measures in these four phenotypes.

Table 1.

Anthropometric and biochemical measures in four PCOS phenotypes (mean ± SD and median in brackets)

| Variable | PCOS phenotype 1 | PCOS phenotype 2 | PCOS phenotype 3 | PCOS phenotype 4 | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (Kg) | 64.3 ± 13.4 (62.0) | 63.0 ± 9.9 (63.0) | 61.0 ± 4.1 (61.0) | 70.0 ± 13.6 (68.5) | 0.23 |

| Height (cm) | 160.3 ± 6.5 (160.5) | 160.3 ± 5.0 (160.0) | 159.2 ± 3.3 (159.0) | 159.2 ± 5.9 (158.5) | 0.87 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 24.7 ± 4.5 (23.8) | 24.7 ± 5.0 (23.0) | 24.1 ± 1.6 (24.5) | 27.6 ± 5.6 (26.5) | 0.11 |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 86.8 ± 14.0 (85.0) | 82.8 ± 9.3 (83.0) | 84.6 ± 10.3 (80.0) | 94.1 ± 13.9 (94.5) | 0.04 |

| Hip Circumference (cm) | 101.7 ± 10.9 (100.5) | 94.6 ± 10.6 (97.0) | 95.4 ± 6.6 (96.0) | 103.7 ± 12.5 (103.0) | 0.05 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 89.7 ± 9.7 (88.5) | 92.1 ± 6.1 (90.0) | 92.4 ± 4.3 (94.0) | 92.2 ± 6.3 (92.5) | 0.13 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 170.6 ± 50.6 (170.0) | 167.9 ± 40.5 (173.0) | 181.4 ± 18.6 (187.0) | 170.0 ± 28.6 (169.0) | 0.69 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 44.7 ± 9.5 (46.0) | 43.8 ± 9.0 (44.0) | 47.2 ± 5.6 (47.0) | 41.7 ± 9.7 (41.5) | 0.53 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 72.2 ± 33.3 (71.0) | 68.5 ± 18.4 (68.0) | 73.0 ± 23.2 (72.0) | 69.0 ± 18.5 (70.0) | 0.97 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 113.6 ± 65.2 (99.0) | 126.5 ± 72.9 (96.0) | 100.2 ± 28.2 (92.0) | 133.4 ± 70.8 (127.0) | 0.54 |

| Insulin level (μIU/mL) | 7.8 ± 3.2 (7.7) | 8.7 ± 4.1 (7.5) | 10.7 ± 6.5 (7.5) | 16.6 ± 4.1 (16.5) | < 0.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.7 ± 0.8 (1.7) | 2.0 ± 0.9 (1.8) | 2.4 ± 1.5 (1.7) | 3.8 ± 1.0 (3.8) | < 0.001 |

| TSH (ng/dl) | 3.0 ± 1.7 (2.7) | 2.8 ± 1.8 (2.5) | 3.2 ± 2.3 (3.2) | 3.8 ± 2.5 (3.2) | 0.53 |

| Prolactin (ng/ml) | 11.6 ± 10.1 (8.4) | 6.3 ± 3.2 (5.3) | 6.8 ± 4.1 (5.0) | 9.5 ± 8.4 (7.1) | 0.34 |

| LH (mIU/ml) | 4.8 ± 4.0 (4.0) | 5.7 ± 3.6 (5.0) | 4.9 ± 1.8 (4.9) | 6.7 ± 5.6 (4.6) | 0.30 |

| FSH (mIU/ml) | 6.4 ± 2.2 (6.6) | 6.5 ± 2.6 (5.8) | 9.2 ± 3.8 (9.0) | 6.5 ± 2.1 (6.3) | 0.10 |

| 17(OH) progesterone (ng/ml) | 1.3 ± 0.9 (1.0) | 1.3 ± 0.7 (1.1) | 1.3 ± 0.7 (1.1) | 2.4 ± 3.3 (1.5) | 0.12 |

| Total Testosterone (nmol/l) | 0.5 ± 0.2 (0.4) | 0.5 ± 0.2 (0.4) | 0.4 ± 0.3 (0.4) | 0.7 ± 0.2 (0.7) | 0.009 |

| Free Androgen Index | 1.4 ± 0.9 (1.3) | 1.2 ± 0.5 (1.1) | 0.7 ± 0.6 (0.5) | 2.7 ± 2.2 (2.1) | 0.001 |

| DHEAS (μmol/l) | 2.9 ± 1.5 (3.0) | 2.8 ± 1.8 (3.0) | 2.7 ± 1.2 (2.5) | 3.9 ± 2.0 (3.8) | 0.12 |

| SHBG (nmol/l) | 54.5 ± 57.2 (35.0) | 44.5 ± 20.0 (41.0) | 71.0 ± 43.8 (63.0) | 36.7 ± 23.0 (30.0) | 0.07 |

| HMWA (ng/ml) | 2986.3 ± 1824.4 (2476.5) | 2628.5 ± 1098.9 (2390.0) | 2359.4 ± 1365.7 (1816.0) | 2798.0 ± 1813.7 (2372.0) | 0.88 |

HDL High-Density Lipoprotein, LDL Low-Density Lipoprotein, HOMA-IR Homeostatic Model Assessment – Insulin Resistance, TSH Thyroid Stimulating Hormone, LH Luteinizing Hormone, FSH Follicle Stimulating Hormone, DHEAS DeHydroEpiandrosterone Sulfate, SHBG Sex Hormone Binding Globulin, HMWA High Molecular Weight Adiponectin. Free Androgen Index: (Testosterone /SHBG)*100

* Difference between mean level, analyzed by ANOVA for normally distributed variables and kruskal-Wallis test for variables without normal distribution

Although the individuals with PCOS phenotype 4 had a higher mean BMI than other phenotypes, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.11). We found a significant difference in the waist circumference that was higher in patients with classic PCOS phenotype (P = 0.04).

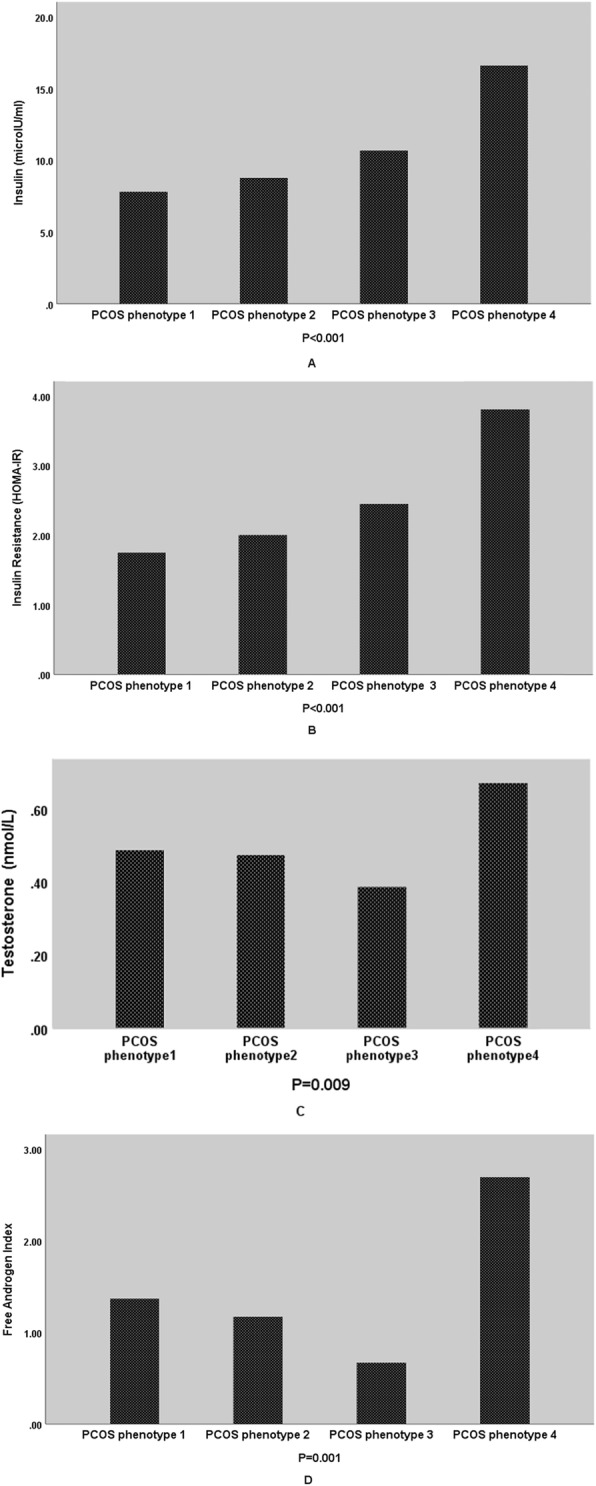

By comparison of hormonal profile of the participants in the four phenotypes, we found a significant difference in the insulin level and insulin resistance that was higher in patients with classic PCOS phenotype (both P < 0.001). In addition, we found a greater level of testosterone and free androgen index in classic PCOS patients (P = 0.009 and 0.001). Figure 1 shows these data in simple bars.

Fig. 1.

Mean level of Insulin (a), Insulin Resistance (b), Testosterone (c), and Free Androgen Index (d) in four groups of individuals based on PCOS phenotypes

We did not find a significant difference in HMWA among the four PCOS phenotypes (P = 0.88 by kruskal-Wallis test).

Table 2 shows biochemical parameters in all participants and separately in different BMI groups.

Table 2.

Biochemical measures of all study subjects and separately in normal weight, overweight, and obese PCOS individuals (mean ± SD and median in brackets)

| Variable | All participants | BMI groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 25 | 25–29.9 | ≥30 | P-value* | ||

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 91.19 ± 7.83 (90.0) | 90.59 ± 6.10 (90.0) | 92.62 ± 10.34 (92.0) | 90.27 ± 6.97 (89.0) | 0.65 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 170.55 ± 40.85 (172.0) | 170.15 ± 50.59 (173.0) | 177.23 ± 26.18 (174.0) | 160.00 ± 32.53 (162.0) | 0.37 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 43.78 ± 9.28 (44.0) | 44.72 ± 9.10 (46.0) | 43.54 ± 11.12 (42.0) | 41.73 ± 5.73 (43.0) | 0.57 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 70.56 ± 25.76 (70.0) | 72.36 ± 32.73 (70.0) | 71.27 ± 64.21 (70.0) | 64.67 ± 21.02 (63.0) | 0.46 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 121.48 ± 66.81 (101.0) | 109.08 ± 61.67 (91.0) | 147.04 ± 81.56 (125.0) | 109.40 ± 34.45 (113.0) | 0.04 |

| Insulin level (μIU/mL) | 10.84 ± 5.43 (9.2) | 9.39 ± 4.47 (8.2) | 12.17 ± 6.10 (12.7) | 12.33 ± 5.88 (11.0) | 0.13 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.4 ± 1.3 (2.0) | 2.13 ± 1.10 (1.8) | 2.81 ± 1.45 (3.0) | 2.76 ± 1.37 (2.3) | 0.13 |

| TSH (ng/dl) | 3.19 ± 2.02 (2.8) | 3.18 ± 2.15 (2.9) | 2.84 ± 1.39 (2.6) | 3.85 ± 2.55 (3.0) | 0.60 |

| Prolactin (ng/ml) | 9.54 ± 8.44 (7.6) | 9.92 ± 7.64 (7.7) | 10.50 ± 10.66 (8.9) | 6.91 ± 5.58 (5.9) | 0.38 |

| LH (mIU/ml) | 5.54 ± 4.37 (4.4) | 6.26 ± 4.45 (4.8) | 5.65 ± 5.07 (4.4) | 3.51 ± 1.49 (4.0) | 0.07 |

| FSH (mIU/ml) | 6.64 ± 2.40 (6.6) | 6.81 ± 2.28 (6.8) | 6.75 ± 2.35 (6.0) | 6.03 ± 2.83 (6.0) | 0.55 |

| 17(OH) progesterone (ng/ml) | 1.63 ± 1.96 (1.2) | 1.49 ± 0.84 (1.3) | 1.97 ± 3.22 (1.1) | 1.41 ± 1.02 (1.1) | 0.50 |

| Total Testosterone (nmol/l) | 0.53 ± 0.25 (0.4) | 0.56 ± 0.26 (0.5) | 0.51 ± 0.26 (0.5) | 0.51 ± 0.23 (0.5) | 0.77 |

| Free Androgen Index | 1.67 ± 1.54)1.3) | 1.47 ± 1.21 (1.2) | 1.80 ± 2.06 (1.4) | 2.02 ± 1.27 (1.6) | 0.16 |

| DHEAS (μmol/l) | 3.18 ± 1.78 (3.2) | 3.39 ± 2.09 (3.3) | 3.11 ± 1.43 (3.0) | 2.79 ± 1.48 (2.4) | 0.45 |

| SHBG (nmol/l) | 48.09 ± 42.3 (35.0) | 57.51 ± 53.3 (40.0) | 43.86 ± 29.70 (36.0) | 30.91 ± 15.54 (30.5) | 0.04 |

| HMWA (ng/ml) | 2814.61 ± 1649.3 (2381.5) | 3342.35 ± 1840.83 (2914.5) | 2331.00 ± 1280.62 (1847.0) | 2280.73 ± 1307.31 (1690.0) | 0.03 |

HDL High-Density Lipoprotein, LDL Low-Density Lipoprotein, HOMA-IR Homeostatic Model Assessment – Insulin Resistance, TSH Thyroid Stimulating Hormone, LH Luteinizing Hormone, FSH Follicle Stimulating Hormone, DHEAS DeHydroEpiandrosterone Sulfate, SHBG Sex Hormone Binding Globulin, HMWA High Molecular Weight Adiponectin. Free Androgen Index: (Testosterone /SHBG)*100

* Difference between mean level, analyzed by ANOVA for normally distributed variables and kruskal-Wallis test for variables without normal distribution

We found that sex hormone binding globulin and HMWA were significantly lower in obese PCOS individuals (p = 0.04, 0.03); other hormonal parameters were not significantly different in the individuals with various BMI.

Table 3 demonstrates the correlation between anthropometric and biochemical parameters. We found a significant correlation between the insulin level and free androgen index (correlation coefficient: 0.305 and P = 0.006) that remained significant (R: 0.244, P = 0.032) after correction for weight, BMI, and waist circumference. In addition, we observed a significant correlation between the level of insulin resistance and free androgen index (correlation coefficient: 0.263 and P = 0.018).

Table 3.

Pearson Correlation between different anthropometric and biochemical parameters (r and p value reported)

| BMI (Kg/m2) | Waist Circumference (m) | Insulin (μIU/mL) | Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (nmol/l) | Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) | High Molecular Weight Adiponectin (ng/ml) | Total Testosterone (nmol/l) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free Androgen Index | 0.172 (0.12) | 0.141 (0.21) | 0.305 (0.006) | −0.427 (< 0.001) | 0.263 (0.01) | −0.067 (0.55) | 0.601 (< 0.001) |

| Total Testosterone (nmol/l) | −0.019 (0.86) | 0.043 (0.70) | 0.212 (0.059) | −0.012 (0.91) | 0.202 (0.07) | 0.079 (0.48) | |

| High Molecular Weight Adiponectin (ng/ml) | −0.275 (0.014) | −0.259 (0.02) | − 0.038 (0.73) | 0.169 (0.13) | − 0.036 (0.75) | ||

| Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) | 0.330 (0.003) | 0.297 (0.007) | 0.985 (< 0.001) | −0.128 (0.25) | |||

| Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (nmol/l) | −0.295 (0.008) | −0.205 (0.06) | − 0.118 (0.29) | ||||

| Insulin (μIU/mL) | 0.336 (0.002) | 0.303 (0.006) | |||||

| Waist Circumference (m) | 0.763 (< 0.001) |

We did not find any association between free androgen index with BMI or HMWA.

Discussion

PCOS is the most common endocrine disorder of the reproductive-aged women. Over the past 30 years, it has been clearly documented that insulin resistance plays an important role in the pathogenesis of the reproductive and metabolic abnormalities of this disorder [18–21].

This study aimed to assess the importance of the insulin level and insulin resistance in PCOS patients based on obesity. We found BMI unrelated insulin resistance in PCOS individuals and a significant correlation between insulin level and free androgen index, irrespective of weight.

Human body is composed of fat mass and fat free mass. Body composition is different by sex and age and this difference is determined by the androgens level [22]. Apart from BMI, among women with PCOS, there is a high prevalence of upper-body obesity, as shown by increased waist circumference and waist-hip ratio as compared to the BMI-matched control women [23–25]. The effect of abdominal obesity on PCOS is probably greater than anticipated because this phenotype is associated with further hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance [26, 27]. In agreement with this idea, the results of this cross-sectional study showed that PCOS individuals had central obesity with a mean waist circumference of 88.0 ± 13.3; also, the patients with classic PCOS phenotype had larger waist circumference and higher level of insulin, insulin resistance, and testosterone compared to other phenotypes.

Some previous studies have investigated the impact of obesity on the hyperandrogenic state in women with PCOS. They uniformly showed higher insulin resistance, lower SHBG plasma levels, and greater evidence of hyperandrogenism in obese PCOS women compared to their normal weight counterparts [5, 8, 28]. The results of some the other studies demonstrated that insulin resistance was present in both obese and non-obese women with PCOS [29–31]. In this study, although obese PCOS individuals had lower SHBG levels, we did not find a significant difference in insulin resistance and testosterone level between obese and non-obese PCOS patients. It is well known that most PCOS patients have some degrees of insulin resistance regardless of their weight and BMI. This feature can be explained by increased phosphorylation of the serine residue of the insulin receptor substrate-1 molecule, and inhibition of insulin receptor signaling in lean PCOS individuals [32].

Moghetti et al. revealed that approximately 70% of PCOS women were insulin resistant; they also mentioned that insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism are two correlated components in the pathogenesis of PCOS. They also evaluated insulin resistance in different types of PCOS phenotypes and found that insulin resistance increased in a statically significant relationship with the severity of PCOS [33].

In this study, we observed higher waist circumference, greater level of insulin, insulin resistance, and androgen in individuals with classic phenotype of PCOS. These findings are inconsistent with the results of a previous study in a representative sample of Iranian women, which did not find a significant difference in insulin resistance and metabolic characteristics among different PCOS phenotypes [34]. This discrepancy can be the result of different study designs, and variable diagnostic criteria for classification of obesity and PCOS phenotypes in these investigations. In addition, it can suggest that there are different pathogenic pathways for different PCOS phenotypes [16].

In this cross-sectional study, we measured the level of high molecular weight adiponectin, a circulating protein produced by adipocytes. Hara and coworkers found higher predictive value of HMWA than total adiponectin for assessment of insulin resistance [35]. We observed that obese PCOS patients had lower level of HMWA. Although it seems that high concentration of testosterone in PCOS patients inhibits the secretion of HMWA by the adipocytes [36], we did not find any association between the androgen level and this adipokine. It seems that there is a complex mechanism for HMWA inhibition by androgen; also, there is debate in the relative influence of estrogens and androgens on HMWA [37].

Conor et al. in their study showed that HMWA was selectively reduced in women with PCOS, independent of BMI [13]. Our study showed that reduction in HMWA level was significantly related to BMI. This difference can be explained by different genetic characteristics and variable patterns of fat deposition in various population.

Limitations

This study had some limitations such as small sample size and lack of BMI matched non-PCOS control group.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results indicate the high incidence of insulin resistance in PCOS patients independent of obesity. In addition, the findings of this study demonstrated that the patients with classic PCOS phenotype had central obesity; and higher level of insulin and insulin resistance despite lack of BMI difference with other phenotypes. These findings imply the insulin resistance as the main pathophysiologic feature in PCOS patients. More detailed studies are warranted for evaluation of insulin resistance and its biomarkers in PCOS patients independent of obesity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran and Center for Development of Clinical Research of Nemazee Hospital and Dr. Nasrin Shokrpour for editorial assistance.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- DHEAS

De Hydro Epi Androsterone- Sulfate

- FSH

Follicle-Stimulating Hormone

- HDL

High-Density Lipoprotein

- HMWA

High Molecular Weight Adiponectin

- HOMA-IR

Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance

- LH

Luteinizing Hormone

- PCOS

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

- SHBG

Sex Hormone Binding Globulin

- TSH

Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone

Authors’ contributions

M.J., F.K.H.S. contributed to conception and design. F.K.H.S.contributed to all experimental work, data and statistical analysis, and interpretation of data. M.J. was responsible for overall supervision. Z.kh. drafted the manuscript, which was revised by M.J. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of the Shiraz University of Medical Science approved this study (IR.SUMS.med. REC.1394.S39). The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Farnaz Kamali Haghighi Shirazi, Email: f.kamali85@gmail.com.

Zohre Khodamoradi, Email: zohre.khodamoradi@gmail.com.

Marjan Jeddi, Email: jedim@sums.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Polak K, Czyzyk A, Simoncini T, Meczekalski B. New markers of insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Investig. 2017;40(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s40618-016-0523-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zawadzki J, Dunaif A. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: towards a rational approach. In: Dunaif A, Givens HR, Haseltine FP, Merriam GR, editors. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Boston: Blackwell Scientific; 1992. pp. 377–384. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Escobar-Morreale HF, Futterweit W, et al. Criteria for defining polycystic ovary syndrome as a predominantly hyperandrogenic syndrome: an androgen excess society guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(11):4237–4245. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rotterdam E, Group A-SPCW Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(1):19. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebrahimi-Mamaghani M, Saghafi-Asl M, Pirouzpanah S, Aliasgharzadeh A, Aliashrafi S, Rezayi N, et al. Association of insulin resistance with lipid profile, metabolic syndrome, and hormonal aberrations in overweight or obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Health Popul Nutr. 2015;33(1):157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zahiri Z, Sharami SH, Milani F, Mohammadi F, Kazemnejad E, Ebrahimi H, et al. Metabolic syndrome in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome in Iran. Int J Fertil Steril. 2016;9(4):490–496. doi: 10.22074/ijfs.2015.4607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rojas J, Chávez M, Olivar L, Rojas M, Morillo J, Mejías J, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome, insulin resistance, and obesity: navigating the pathophysiologic labyrinth. Int J Reprod Med. 2014;2014:719050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Glueck CJ, Goldenberg N. Characteristics of obesity in polycystic ovary syndrome: etiology, treatment, and genetics. Metabolism. 2019;92:108–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.De Leo V, Musacchio MC, Cappelli V, Massaro MG, Morgante G, Petraglia F. Genetic, hormonal and metabolic aspects of PCOS: an update. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2016;14(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12958-016-0173-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng X, Xie YJ, Liu YT, Long SL, Mo ZC. Polycystic ovarian syndrome: correlation between hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance and obesity. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;502:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2019.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Layegh P, Mousavi Z, Tehrani DF, Parizadeh SMR, Khajedaluee M. Insulin resistance and endocrine-metabolic abnormalities in polycystic ovarian syndrome: comparison between obese and non-obese PCOS patients. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2016;14(4):263. doi: 10.29252/ijrm.14.4.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bannigida DM, Nayak SB. R V. serum visfatin and adiponectin - markers in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2020;126(4):283–286. doi: 10.1080/13813455.2018.1518987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Connor A, Phelan N, Tun TK, Boran G, Gibney J, Roche HM. High-molecular-weight adiponectin is selectively reduced in women with polycystic ovary syndrome independent of body mass index and severity of insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(3):1378–1385. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldani DP, Skrgatic L, Kasum M, Zlopasa G, Kralik Oguic S, Herman M. Altered leptin, adiponectin, resistin and ghrelin secretion may represent an intrinsic polycystic ovary syndrome abnormality. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2019;35(5):401–405. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2018.1534096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CI, Hsu MI, Lin SH, Chang YC, Hsu CS, Tzeng CR. Adiponectin and leptin in overweight/obese and lean women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015;31(4):264–268. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2014.984676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guastella E, Longo RA, Carmina E. Clinical and endocrine characteristics of the main polycystic ovary syndrome phenotypes. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(6):2197–2201. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ascaso JF, Pardo S, Real JT, Lorente RI, Priego A, Carmena R. Diagnosing insulin resistance by simple quantitative methods in subjects with normal glucose metabolism. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3320–3325. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.12.3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurliman A, Keller Brown J, Maille N, Mandala M, Casson P, Osol G. Hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance, not changes in body weight, mediate the development of endothelial dysfunction in a female rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Endocrinology. 2015;156(11):4071–4080. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cassar S, Misso ML, Hopkins WG, Shaw CS, Teede HJ, Stepto NK. Insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp studies. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(11):2619–2631. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koivuaho E, Laru J, Ojaniemi M, Puukka K, Kettunen J, Tapanainen J, et al. Age at adiposity rebound in childhood is associated with PCOS diagnosis and obesity in adulthood—longitudinal analysis of BMI data from birth to age 46 in cases of PCOS. Int J Obes. 2019;43(7):1370–1379. doi: 10.1038/s41366-019-0318-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Genazzani AD, Prati A, Marchini F, Petrillo T, Napolitano A, Simoncini T. Differential insulin response to oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in overweight/obese polycystic ovary syndrome patients undergoing to myo-inositol (MYO), alpha lipoic acid (ALA), or combination of both. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2019;35(12):1088–1093. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2019.1640200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghachem A, Lagacé J-C, Brochu M, Dionne IJ. Fat-free mass and glucose homeostasis: is greater fat-free mass an independent predictor of insulin resistance? Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31(4):447–454. doi: 10.1007/s40520-018-0993-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee CG, Boyko EJ, Barrett-Connor E, Miljkovic I, Hoffman AR, Everson-Rose SA, et al. Insulin sensitizers may attenuate lean mass loss in older men with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(11):2381–2386. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shan B, Cai J-h, Yang S-Y, Li Z-R. Risk factors of polycystic ovarian syndrome among Li people. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2015;8(7):590–593. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shorakae S, Ranasinha S, Abell S, Lambert G, Lambert E, de Courten B, et al. Inter-related effects of insulin resistance, hyperandrogenism, sympathetic dysfunction and chronic inflammation in PCOS. Clin Endocrinol. 2018;89(5):628–633. doi: 10.1111/cen.13808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spritzer PM, Lecke SB, Satler F, Morsch DM. Adipose tissue dysfunction, adipokines, and low-grade chronic inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome. Reproduction. 2015;149(5):R219–RR27. doi: 10.1530/REP-14-0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Couto Alves A, Valcarcel B, Mäkinen VP, Morin-Papunen L, Sebert S, Kangas AJ, et al. Metabolic profiling of polycystic ovary syndrome reveals interactions with abdominal obesity. Int J Obes. 2017;41(9):1331–1340. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jia J, Bai J, Liu Y, Yin J, Yang P, Yu S, et al. Association between retinol-binding protein 4 and polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis. Endocr J. 2014;61(10):995–1002. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ14-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daghestani MH. Evaluation of biochemical, endocrine, and metabolic biomarkers for the early diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome among non-obese Saudi women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;142(2):162–169. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pande AR, Guleria AK, Singh SD, Shukla M, Dabadghao P. Beta cell function and insulin resistance in lean cases with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2017;33(11):877–881. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2017.1342165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toosy S, Sodi R, Pappachan JM. Lean polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): an evidence-based practical approach. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2018;17(2):277–285. doi: 10.1007/s40200-018-0371-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seow K-M, Juan C-C, Hsu Y-P, Hwang J-L, Huang L-W. Low-Tone Ho Amelioration of insulin resistance in women with PCOS via reduced insulin receptor substrate-1 Ser312 phosphorylation following laparoscopic ovarian electrocautery. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(4):1003–1010. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moghetti P, Tosi F, Bonin C, Di Sarra D, Fiers T, Kaufman J-M, et al. Divergences in insulin resistance between the different phenotypes of the polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(4):E628–EE37. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hosseinpanah F, Barzin M, Keihani S, Ramezani Tehrani F, Azizi F. Metabolic aspects of different phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome: Iranian PCOS Prevalence Study. Clin Endocrinol. 2014;81(1):93–99. doi: 10.1111/cen.12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hara K, Horikoshi M, Yamauchi T, Yago H, Miyazaki O, Ebinuma H, Imai Y, Nagai R, Kadowaki T. Measurement of the high-molecular weight form of adiponectin in plasma is useful for the prediction of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(6):1357–1362. doi: 10.2337/dc05-1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu A, Chan KW, Hoo RL, Wang Y, Tan KC, Zhang J, et al. Testosterone selectively reduces the high molecular weight form of adiponectin by inhibiting its secretion from adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(18):18073–18080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merki-Feld GS, Imthurn B, Rosselli M, Spanaus K. Serum concentrations of high-molecular weight adiponectin and their association with sex steroids in premenopausal women. Metabolism. 2011;60(2):180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.