Abstract

This is the first study to assess human health risks due to the exposure of ‘repurposed’ pharmaceutical drugs used to treat Covid-19 infection. The study used a six-step approach to determine health risk estimates. For this, consumption of pharmaceuticals under normal circumstances and in Covid-19 infection was compiled to calculate the predicted environmental concentrations (PECs) in river water and in fishes. Risk estimates of pharmaceutical drugs were evaluated for adults as they are most affected by Covid-19 pandemic. Acceptable daily intakes (ADIs) are estimated using the no-observed-adverse-effect-level (NOAEL) or no observable effect level (NOEL) values in rats. The estimated ADI values are then used to calculate predicted no-effect concentrations (PNECs) for three different exposure routes (i) through the accidental ingestion of contaminated surface water during recreational activities only, (ii) through fish consumption only, and (iii) through combined accidental ingestion of contaminated surface water during recreational activities and fish consumption. Higher risk values (hazard quotient, HQ: 337.68, maximum; 11.83, minimum) were obtained for the combined ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities and fish consumption exposure under the assumptions used in this study indicating possible effects to human health. Amongst the pharmaceutical drugs, ritonavir emerged as main drug, and is expected to pose adverse effects on r human health through fish consumption. Mixture toxicity analysis showed major risk effects of exposure of pharmaceutical drugs (interaction-based hazard index, HIint: from 295.42 (for lopinavir + ritonavir) to 1.20 for chloroquine + rapamycin) demonstrating possible risks due to the co-existence of pharmaceutical in water. The presence of background contaminants in contaminated water does not show any influence on the observed risk estimates as indicated by low HQadd values (<1). Regular monitoring of pharmaceutical drugs in aquatic environment needs to be carried out to reduce the adverse effects of pharmaceutical drugs on human health.

Abbreviations: ADI, acceptable daily intake; BCF, bio-concentration factor; BAF, bio-accumulation factor; EMEA, European Medicines Evaluation Agency; HQ, hazard quotient; HI, hazard index; HIint, hazard index interaction; NOEL, no observed effect level; NOAEL, no-observed-adverse-effect-level; OECD, The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; PEC, predicted environmental concentrations; PNEC, predicted no-effect concentrations; WHO, World Health Organization

Keywords: Novel coronavirus, Covid-19, Pharmaceuticals, Rivers, PECs, Risk estimation

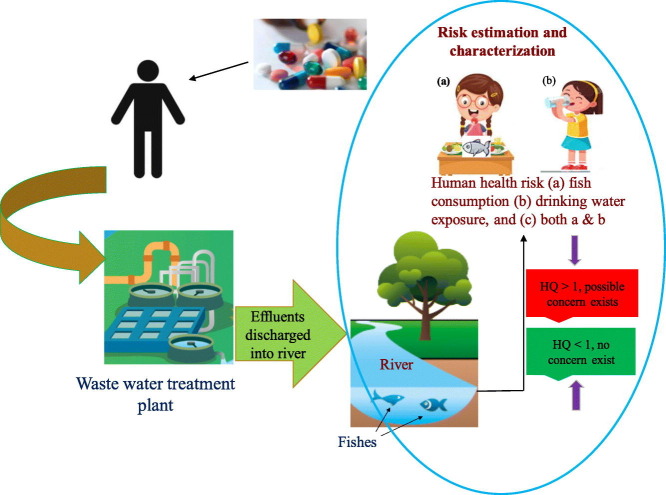

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

At the end of Dec 2019, Wuhan, an emerging business hub of China, experienced an outbreak of a novel coronavirus that killed more than eighteen hundred and infected over seventy thousand individuals within the first fifty days of the epidemic (Liu et al., 2020). Looking into the lethal effect of coronavirus, the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus (Covid-19) designated as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), as a global pandemic in March 2020 (WHO, 2020a). Till the time of writing, the coronavirus epidemic has infected more than 107 million people, and nearly 2.36 million has died as per the WHO statistics (WHO, 2020b).

Research investigations reported that coronavirus is an enveloped virus with single stranded RNA as the genetic material (Fung and Liu, 2019). Since the discovery of coronavirus, no vaccine and/or specific therapeutic drugs were available for treating SARS-CoV-2 illness (Liu et al., 2020), and to overcome this problem, ‘repurposed’ drugs are used (Singh et al., 2020). Repurposed drugs can be defined as those drugs which have been used to treat similar kind of viruses. Some of the drugs include anti-retroviral drugs (AIDS virus, Ebola virus, SARS virus), anti-malarial drugs, chemotherapeutic agents, etc. (Dagens et al., 2020; Franquet-Griell et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020). However, the effectiveness of these treatment programs needs to be certified by suitably planned clinical trials. Countries like US, Germany, Italy, France, Russia etc., are using anti-retroviral drugs as an alternative to treat Covid-19 patients. Recently, in Jan 2021, some of the countries, for instance, UK, USA, India (Krishnan, 2021) have achieved success in developing vaccines to combat this deadly disease and the vaccines are now available for use. But still the vaccines are not available globally since the demand is more than supply and majority of the nations are still depending on repurposed drugs for treating covid-19 patients.

Since the outbreak of Covid-19 pandemic, a considerable increase in use of repurposed therapeutic drugs has been reported (Singh et al., 2020). Because of their over-use, enormous amount of these drugs are excreted unchanged as parental compound through human metabolism. Studies demonstrated that the conventional wastewater treatment plants are not specifically designed for removing these specified drugs, as a result, large quantity of untreated effluent is being discharged into the surrounding water bodies such as rivers, lakes, and streams (Xu et al., 2007; Choi et al., 2008). Incessant discharge of untreated pharmaceutical drugs will increase the pharmaceutical load of the receiving water bodies (Wollenberger et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2014; Yan et al., 2016) and plants (Migliore et al., 2003; Pan and Chu, 2016) and may lead to possible bioaccumulation and their subsequent bio-magnification in the underlying aquatic organisms specially fishes (Edwards et al., 2009). The accumulation of pharmaceutical drugs in the aquatic environment can pose risk to the underlying organisms possibly through food chain transfer, even at low concentrations (Wellington et al., 2013; Sharma et al., 2016). Possible human health risk exposure can occur if the contaminated water is accidentally ingested by human beings during recreational activities or through consumption of fish grown in contaminated waters, or both (Kumari and Kumar, 2020a; Parsai and Kumar, 2020). This study addresses health risk exposure effects of repurposed pharmaceutical drugs to humans. No such studies are available in published literature to the author's best knowledge till date. The prime objective of this study was to assess the health risk effects by the exposure of repurposed drugs used for treating Covid-19 infected patients. The study applied the recommended risk assessment framework for estimating human health risk exposure effects of repurposed drugs. Human health risks is estimated for three different exposure pathways (i) accidental ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities, (ii) consumption of fishes grown in contaminated waters, and (iii) both the exposure routes combined together. For the purpose, five different repurposed drugs named as lopinavir (LOP), ritonavir (RIT), chloroquine (CHQ) or hydroxychloroquine, ribavirin (RIB), and sirolimus or rapamycin (RAP) were selected.

The pharmaceutical drugs were selected based on their effectiveness in treating SARS-CoV-2 infection as reported by clinical trial studies (WHO, 2020c). The proposed structure can be used in determining health risks exposure of other-related drugs as well. The outcome of the study can benefit risk evaluators in estimating risk due to exposure of repurposed drugs, and also furnish details to controllers in identifying the need for treating the water bodies prior to its use, and also restricting fish extraction from contaminated water.

2. Methodology

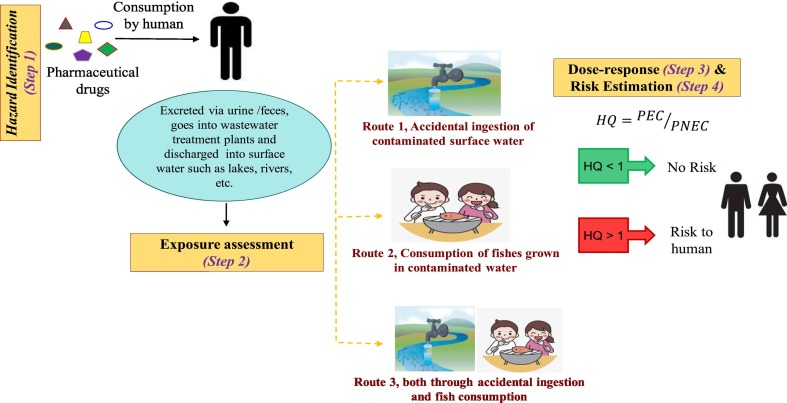

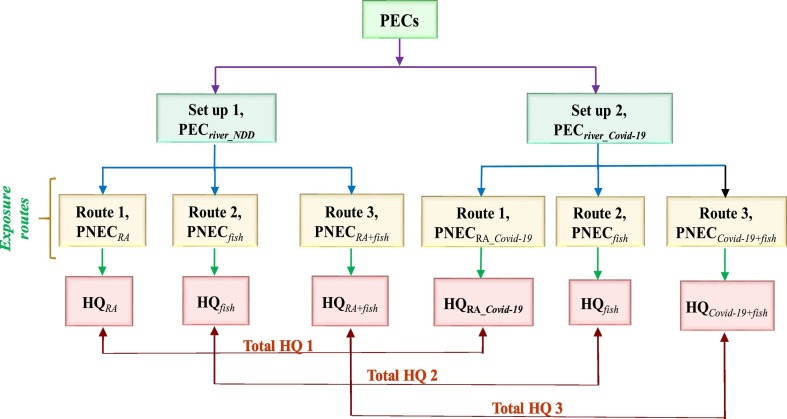

The diagrammatic representation of the proposed methodology to determine the human health risks of repurposed drugs used to fight Covid-19 infection is given in Figure1. This study evaluated risk exposures for three different pathways which will be discussed later on. The study applied a six-step approach comprising of hazard identification, dose-response assessment, exposure assessment, risk estimation, risk characterization and management to estimate human health risks (Sohaili et al., 2017; Parsai and Kumar, 2020). Briefly, this framework (Fig. 1 ) assumes that pharmaceutical drugs taken via the oral route are excreted through feces and urine either metabolized or un-metabolized as parental drugs. The untreated pharmaceutical wastewater effluents are usually discharged into the near-by surface water from which these drugs can enter into aquatic organisms through food chain. Surface water is the major source of water used by human beings for recreational activities, but uncontrolled and untreated discharge of pharmaceutical wastewater effluent makes the water contaminated. Under any circumstances, if this contaminated water is accidentally ingested, they might show adverse health effects and possible risk (Gibs et al., 2013; Yao et al., 2017). Pharmaceutical drugs present in the surface water can also get accumulated in fish muscles and tissues which on consumption by human leads to possible exposure. Both the accidental ingestion of pharmaceutical contaminated water and consumption of fishes might have detrimental effects on human health.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of methodology adopted to determine human health risk exposure though accidental ingestion of surface water, fish consumption, and both the routes. PEC is the predicted environmental concentration of drugs; PNEC is the predicted no-effect concentration of drugs; HQ is the hazard quotient.

2.1. Hazard identification

Hazard identification is the first step in the risk assessment process. This step involves identifying the toxicity of contaminants selected for risk exposure.

2.1.1. Selection of pharmaceutical drugs

This study selected five different pharmaceutical drugs named as lopinavir (LOP), ritonavir (RIT), chloroquine (CHQ), ribavirin (RIB), and sirolimus or rapamycin (RAP) on the basis of their efficacy in conducted clinical trials to treat Covid-19 infection (Gordon et al., 2020; WHO, 2020c). LOP-RIT has been projected as a possible treatment for COVID-19 based on preclinical and empirical studies (Horby et al., 2020). LOP is a HIV-1 protease inhibitor, which is combined with ritonavir to increase its plasma half-life. LOP is also an inhibitor of SARS-CoV main protease, which is crucial for replication and was found to be exceedingly conserved in SARS-CoV-2 (Nukoolkarn et al., 2008; Liu and Wang, 2020). RIB, an antiviral agent, is generally used in combination with lopinavir-ritonavir and helps in minimizing the risk of dreadful clinical aftermaths besides reducing viral load amongst patients infected with SARS (Chu et al., 2004; Rabi et al., 2020). CHQ, an antimalarial drug, and could be effective tool against SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 (Colson et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2020). Sirolimus, also known as RAP, is an immunosuppressant and its immuno-therapeutic potential (mTOR inhibitor) has been found to be effective against COVID-19 infection (Omarjee et al., 2020) which is currently under phase 2 trial in USA (NCT04341675) (NIH, 2020). Table 1 shows detailed information about the repurposed drugs including their therapeutic class, Chemical Abstract Registry Number (CASR No.), molecular weight, chemical structure, log Kow values, and administered drug dose.

Table 1.

Information of selected drugs.

| Drugs | Therapeutic class | CASR no. | Chemical formula & mol. wt. (g/mol) |

Log Kow | Dose of pharmaceuticals (mg/person/day) |

Clinical trial dose, Covid-19⁎ (mg/person/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lopinavir | Antiretroviral protease inhibitor | 192725-17-0 | C37H48N4O5, 628.80 | 5.94 | 800#1 | 400 mg twice a day |

| Ritonavir | HIV protease inhibitor | 155213-67-5 | C37H48N6O5S2, 720.94 | 6.29 | 1200#1 | 100 mg twice a day |

| Ribavirin | Antiviral agent | 36791-04-5 | C8H12N4O5, 244.20 | −1.8 | 800#2 | 600 mg twice a day |

| Chloroquine | Antimalarial | 54-05-7 | C18H26ClN3, 319.827 | 4.496 | 71.4#2 | 400 mg once a day |

| Rapamycin or Sirolimus | Immunosuppressant | 20830-81-3 | C51H79NO13, 914.187 | 4.80 | 2#3 | 2 mg once a day |

Landscape analysis of therapeutics WHO.

2.1.2. PEC estimation

Limited information is available on the environmental occurrence of selected pharmaceutical drugs in published literature (Abafe et al., 2018; Wood et al., 2015). Predicted environmental concentrations (PECs) is a practical approach (Franquet-Griell et al., 2015) to identify the concentration level of pharmaceutical drugs in water environment. This approach has been successfully used to predict the concentration of antibiotics (Kumari and Kumar, 2020a), and other related drugs (Burns et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2016) in drinking water, wastewater and surface waters. In this study, PEC values of selected pharmaceutical drugs were estimated for two different set-ups. The methodological approach is represented in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of the methodology used to determine risk estimates. PECriver_NDD is PEC in river (surface water) under normal drug dose; PECriver_Covid-19 is the PEC in river for drug dose used to treated Covid-19 infection; PNECRA is the predicted no effect concentration due to the accidental ingestion of contaminated surface water during recreational activities; PNECfish is the predicted no effect concentration due to fish consumption exposure; PNECRA+fish is the combined predicted no effect concentration due to the accidental ingestion of contaminated surface water during recreational activities and fish consumption exposure. HQRA is the hazard quotient exposure to the accidental ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities; HQfish is hazard quotient during fish consumption exposure; HQRA+fish is the hazard quotient during combined exposure to the accidental ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities and fish consumption.

Under set-up 1, dose of pharmaceutical drugs was considered under normal conditions and is referred as PECriver_NDD. In set up-2, PEC was estimated for dose of drugs used for treating Covid-19 infection (PECCovid-19). PEC values (PECriver_NDD and PECCovid-19) were calculated in accordance with the Guideline on the Environmental Risk Assessment of Medicinal Products for Human Use (EMEA, 2006) and the Technical Guidance Document on Risk Assessment part II, TGD (EC, 2003) EMA guidelines as represented by Eq. (1). For set-up 1, drug dose data of pharmaceutical drugs, Dose*inhab in Eq. (1) was extracted from well-known drugs sites such as www.drugbank.ca and www.drugs.com. For set-up 2, PECriver_Covid-19, drugs dose information of pharmaceuticals “repurposed drugs” is based on conducted clinical trials and the data is retrieved from Landscape analysis of therapeutics (WHO, 2020c, WHO, 2020d).

| (1) |

where, Dose*inhab (mg/person/day) is the consumed amount of each pharmaceutical drug administered per person per day in USA; Fpen is market penetration and represents the fraction of the total population that consumes the pharmaceutical on any given day. A default value of 0.01 was applied for PECriver_NDD whereas, for PECriver_Covid-19, the value is taken as 0.47 (Elflein, 2020b); FExec is the fraction of parent drug excreted unaltered via human metabolism. Both urine and feces are considered. Excretion profile of the drugs was extracted from the published literature, and the drug bank database. For those pharmaceutical drugs whose data was not available, a default value of 0.5 was applied, assuming that a drug will not be completely eliminated as parental drug (Gómez-Canela et al., 2019); FWWTP indicates the removal fraction in WWTPs. Here, the values are taken from published literature and for those drugs whose values could not be found, a default value of 0.5 was considered. 1-FWWTP, is the fraction of pharmaceutical's emission from WWTPs to surface waters; WWinhab (L/person/day) is the amount of wastewater per person per day. A default value of 200 L/person/day was used (EC, 2003). W represents the number of person in a defined zone (in this case USA population was considered), and lastly, DF is the dilution factor from WWTP effluents to surface waters. Discrepancies in this data can differ the results by more than 100-fold (Elflein, 2020a). A default value (DF = 10) recommended by the European Medical Agency (EMA) was applied (Gómez-Canela et al., 2019).

For PECriver_Covid-19, Doseinhab ⁎ was calculated using the following approach. First, the data on numbers of seniors (65 + Yr) infected, for example, say “A” and hospitalization rate of seniors “B” is taken from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covidview/index.html). So, the total number of seniors affected by Covid-19 is equal to the number of seniors infected (A) multiplied by hospitalization rate of seniors (B). Now, dose of ‘repurposed’ drugs administered to seniors is determined by multiplying the number of seniors infected by Covid-19 with drug dose administered to seniors per day (based on clinical trial data).

Concentrations of pharmaceutical drugs in fishes were calculated using previously estimated concentration values of drugs in river (PECriver), bio-concentration factors (BCF) for fish, and bio-magnification factors (BMF), as given in Eq. (2). Since, the BCF values of selected pharmaceutical drugs are not available in published literature, the values were calculated using the octanol-water partition coefficient (Kow) values of drugs and lipid content fraction in fishes, using Eq. (3).

| (2) |

| (3) |

where, BCF is the bio-concentration factors (LKg−1); BMF is the bio-magnification factor of pharmaceutical drugs, the value is assumed to be 1 in this study (unit less); fW is water content fraction of the organism; flip is lipid content fraction of the organism; pHint is internal pH, and pHext is external pH; Dlip-water is lipid-water partition coefficient, and was calculated as log Dlip-water = 0.904 × log Kow + 0.515 (Fick et al., 2010).

2.2. Exposure assessment

This study estimated risks of pharmaceutical drugs to adults as they are reported to be the most sensitive sub-population category affected by SARS CoV-2 infection (Grant et al., 2020) and are prone to higher risks as suggested by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA. Exposure assessment study was carried out for two different set-ups considering three different exposure routes as mentioned in Fig. 1. Exposure route-1 indicates risks due to the accidental ingestion of contaminated surface water during recreational activities, exposure route-2 for consumption of fishes grown in pharmaceutical-contaminated water, and in route-3, exposure was estimated for the combined accidental ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities and through fish consumption.

2.2.1. Acceptable daily intake (ADI) estimation

The acceptable daily intake (ADI) is one of the crucial parameter in determining risk estimates. ADI signifies the highest intake level of a substance that does not give rise to minimal or no risk observable adverse effects (Dennis and Wilson, 2003). When clinical studies in humans are inappropriate or could not be found, the ADI is estimated from reliably conducted toxicity studies in laboratory animals by using the no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) or the no observable effect level (NOEL) associated with the most sensitive endpoint in the most sensitive species (Hurt et al., 2010). To account for differences between animals and humans (inter-species variability) and for intra-individual variability between humans, the NOAEL is divided by a safety (uncertainty) factor to establish an ADI. In this study, ADI values of ‘repurposed’ pharmaceutical drugs was estimated using NOAEL or NOEL values in rats, the conversion from rats to human was carried out using a safety factor of 100 as given in Eq. (4). A default safety factor of 100 takes into account both the differences in species and differences in toxicokinetics and toxicodynamics properties (Dankovic et al., 2015). It is generally based on the assumption that humans are 10 times more sensitive to a substance than experimental animals and that there is a 10-fold range in sensitivity within the human population (Gilsenan, 2011).

| (4) |

2.2.2. PNEC estimation

A PNEC signifies the concentration in surface water at or below which no adverse human health effects are expected to occur (Schwab et al., 2005). In this study, PNEC values were calculated for three different exposure routes (i) accidental ingestion of pharmaceutically contaminated surface water during recreational activities (PNECRA); (ii) consumption of fishes grown in pharmaceutically contaminated surface water (PNECfish); and (iii) combined exposure due to the accidental ingestion of contaminated surface water during recreational activities and through fish consumption (PNECriver+fish) using Eqs. (5), (6), (7).

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

where, ADI is the acceptable daily intake (mg kg-day−1); BW is the body weight (Kg); AT is the average lifetime (Days); IRDW is the surface water ingestion rate (L day−1); EF is the exposure frequency (days Year−1); ED is the exposure duration (Year). ED values were taken as per the scenario considered: for normal drug dose, ED value of 70 Yrs. was applied to estimate PNECs for the three different categories mentioned above. However, for Covid-19 case, ED value was considered to be 1 year assuming that the Covid-19 cases would decline in near future once the vaccine is developed; BCF is the bio-concentration factor in fish (L Kg−1). CRFish is the fish consumption rate (Kg day−1). Table S1 in the supplementary information provides the values of input parameters used for PNEC estimation.

2.3. Risk estimation

2.3.1. Risk estimation exposure of individual pharmaceutical drugs

The study estimated risk exposure effects for the hypothetical exposures of individual pharmaceutical drugs by means of hazard quotient, HQ. Hazard quotient value was calculated as a ratio of PEC/PNEC Eq. (8). In Eq. (8), PECs values are taken from the exposure assessment section and PNECs from the dose-response assessment section. If the calculated HQ are larger than 1 then concern exists to human health for the exposure route studied and vice versa (Kumari and Gupta, 2018). The total HQ of ‘repurposed’ pharmaceutical drugs was calculated by adding up the individual HQ values of surface water (river) and the individual HQ values of river_Covid-19 (Eq. (9)).

| (8) |

| (9) |

2.3.2. Risk estimation exposure of co-occurring pharmaceutical drugs

It is expected that under realistic scenario i.e. in surface waters, pharmaceutical drugs usually exist in mixture combinations and not as individual drugs. Therefore, it is essential to determine the risks exposure effects of co-existing pharmaceutical drugs on human health for the different exposure routes mentioned above. Risk estimation of pharmaceutical drugs in binary mixtures is represented as HIint, and was calculated using the modified USEPA weight of evidence approach, as given in Eqs. (10), (11), (12) (Kumari and Kumar, 2020a; US EPA, 2000).

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

where, HQi and HQj is the hazard quotient of ith compound and jth compound; fij is the toxicity hazard of jth compound (j ≠ 1). It is assumed that two pharmaceutical drugs can interact with each other, fij value is considered as 1.; Mij, represents the magnitude of interaction, a default values of 5 was applied as per the U.S. EPA recommendations (U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency), 2009c, U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency), 2009d). Bij is the score for the strength of evidence. Bij values for binary mixture combinations were obtained by category I and IV given in the Classification and Default Weighting Factors for The Modified Weight of Evidence (US EPA, 2000).

2.3.3. Risk estimation exposure of background contaminants with individual co-occurring pharmaceutical drugs

Comprehensive hazard risk assessment study was performed to determine the risk exposure effects of background contaminants on pharmaceutical drugs. It is believed that several type of background contaminants like nanoparticles, antibiotics, etc., might be present in aquatic environment (Gros et al., 2010; Osorio et al., 2016). This study considered antibiotics as background contaminants for calculating the overall health risk exposure to humans. Fluoroquinolones are the most frequently detected antibiotics in the environmental media (Sukul and Spiteller, 2007) of which ciprofloxacin (CIP) and norfloxacin (NOR) are primarily detected in higher concentrations (Mahmood et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2015; Yao et al., 2017). Drug-drug interaction data of binary mixture drugs are hardly available in scientific literature, hence, we have used the concentration or dose-addition approach to determine the total risk, referred to as HItotal. HItotal was calculated by summing up the individual HQ values of background contaminants and individual pharmaceutical drugs as given in Eq. (13). HI values of antibiotics CIP and NOR is taken from our previous published work (Kumari and Kumar, 2020a, Kumari and Kumar, 2020b), and HI values of individual pharmaceutical drugs is taken from risk estimation exposure of co-occurring pharmaceutical drugs Section 2.3.2.

| (13) |

2.4. Sensitivity index analysis

Sensitivity index analysis was performed to identify the most influential parameters governing risk estimates (Kumari and Gupta, 2018), and to determine the variability in HQ values with respect to change in several constant variables such as body weight, exposure duration, exposure frequency, ingestion rate, fish consumption rate, and BCF. Sensitivity index for the three different exposure routes was calculated using Eq. (14).

| (14) |

where, Var# denotes the variables (body weight, exposure duration, intake rate, fish consumption rate, BCF, and exposure frequency) considered for calculating the sensitivity index for the three different exposure routes. Varhigh, Varlow and Varaverage denotes the high, low and average values of the variables considered; HQhigh and HQlow values indicates the estimated high and low HQ values of the variables.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Predicted environmental concentrations, PEC

PEC values of pharmaceutical drugs in surface water were estimated for three different cases i.e. PECriver_NDD, PECriver_Covid-19, and PECfish. Table 1 enlists the estimated PEC values for three different exposure routes. For PECriver_NDD, RIB has the highest concentration values in surface water followed by CHQ, whereas LOP has the lowest concentration values. For PECriver_Covid-19, here also RIB reported the highest concentration values followed by LOP and RIT. It was observed that remarkably low concentration values were obtained for PECriver_Covid-19 compared to PECriver_NDD. This decrease in the concentration values can be attributed to the amount of drug dose administered to Covid-19 infected patients. It can also be seen that in both the cases RIB has the highest concentration in surface water. Study showed that RIB is one of the most frequently administered HIV drug to human (Pradat et al., 2014), and there is a chance that the untreated wastewater effluent is discharged into the nearby rivers or lakes resulting in high levels.

In order to predict the concentration of pharmaceutical drugs (PECs) in fishes, BCF values were first estimated. The calculated BCF values of the pharmaceutical drugs ranged from 1.32 L Kg−1 (for RIT) to 0.58 L Kg−1 (for RIB). Four of the five pharmaceutical drugs have BCF values of more than 1.0 L/kg either because the drug is ionic with a log K ow of less than 5 (2 of 5). Only one pharmaceutical drug has BCF value smaller than 1.0 L/kg because the drug is non-ionic but has a log K ow of less than 1.0 (Table 1). A bioconcentration factor greater than 1 is indicative of a hydrophobic or lipophilic chemical. It is an indicator of how probable a chemical is to bioaccumulate (Landis et al., 2011).

PEC values in fishes ranged from 2245 μg Kg−1 (for RIB) to 26 μg Kg−1 (for RAP). Concentration of RIB appeared to be maximum in fishes as indicated by high PEC values (Table 2 ). Since there is a possibility that pharmaceutical drugs might get accumulated in the fish tissues, hence, the bio-accumulative potential of drugs was also considered for predicting the concentration in fish tissues. Bio-accumulation factor (BAF, L Kg−1) was calculated as a ratio of pharmaceutical drug concentration in fish tissues to that in water. The results revealed that RIT showed the highest bio-accumulative potential followed by LOP, while RIB has the lowest BAF values. As observed in this study, BAF values of pharmaceutical drugs RIT, LOP, RAP and CHQ was more than 1, representing that the bio-accumulative potential. BAF values >1 show that the accumulation of pharmaceutical drugs in the fish tissues is greater than that of the medium, for instance, soil or water in which the drug is present (US EPA, 2009). Earlier studies have also reported that concentration of pharmaceuticals drugs in fishes is considerably higher in plasma than in ambient water (Fent et al., 2006).

Table 2.

PEC estimates of pharmaceutical drugs (highest value is shown as bold text (italics) for each water compartment and for fish).

| Drugs | PECriver_NDD (μg L−1) | PECriver_Covid-19 (μg L−1) | PECfish (μg Kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lopinavir, LOP | 186 | 1.89 × 10−4 | 239 |

| Ritonavir, RIT | 128 | 2.08 × 10−5 | 169 |

| Chloroquine, CHQ | 1678 | 3.78 × 10−6 | 1940 |

| Ribavirin, RIB | 3842 | 1.52 × 10−4 | 2245 |

| Rapamycin, RAP | 22 | 4.72 × 10−7 | 26 |

3.2. ADI estimates

ADI values of pharmaceutical drugs were calculated using NOAEL or NOEL values in rats. The conversion of NOAEL/NOEL values from rats to human was done using a safety factor as mentioned in the exposure assessment section. The estimated ADI values of pharmaceutical drugs was 0.1 mg kg−1 day−1 for LOP, RIT: 0.05 mg kg−1 day−1 CHQ: 16.6 mg kg−1 day−1, RIB: 15 mg kg−1 day−1, and RAP: 0.01 mg kg−1 day−1. It can be seen that CHQ has the highest ADI value whereas RIT has the lowest ADI values.

3.3. PNEC estimates

PNEC values of pharmaceutical drugs in adults were estimated for two different scenarios (1) for normal drug dose, and (2) for ‘repurposed’ drugs dose used to treat Covid-19 infection for three different exposure route as mentioned above in the exposure assessment section.

Table 3 shows the PNEC values of different scenarios considered for three different exposure pathways. Under set-up 1 (normal drug dose), PNEC values for the accidental ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities ranged from 1.05 × 108 μg L−1 (for RIB) to 7 × 103 μg L−1 (for RAP). For fish consumption exposure, PNECfish values ranged from 2.76 × 102 μg L−1 (RIB) to 9.04 × 10−2 μg L−1 (for RAP). For the combined exposure to ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities and fish consumption exposure, PNECfish+RA ranged from 2.36 × 102 μg L−1 (for RIB) to 8.34 × 10−2 μg L−1 (for RAP). Overall, it was witnessed that ribavirin has the maximum PNEC values for all the three exposure routes whereas rapamycin has the lowest. Thus, it is possible that ribavirin might show adverse effects to human health for the three exposure routes studied.

Table 3.

Estimated PNEC values of human health effects for normal drug dose (smallest PNEC value is highlighting as bold text and indicate drug-of-concern for a given exposure pathway; smallest PNEC value amongst all exposure pathway is shown as italicized and underline texts).

| Drugs | For normal drug dose |

For dose used in Covid-19 infection |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNECRA (μg L−1) |

PNECfish (μg L−1) |

PNECRA+fish (μg L−1) |

PNECRA (μg L−1) |

PNECfish (μg L−1) |

PNECRA+fish (μg L−1) |

|

| LOP | 7.0 × 104 | 8.30 × 101 | 7.75 × 10−1 | 7.0 × 104 | 8.35 × 101 | 7.75 × 101 |

| RIT | 3.50 × 104 | 4.07 × 101 | 3.79 × 10−1 | 3.50 × 104 | 4.07 × 101 | 3.79 × 101 |

| CHQ | 1.16 × 107 | 1.50 × 102 | 1.40 × 102 | 1.16 × 107 | 1.54 × 104 | 1.42 × 104 |

| RIB | 1.05 × 108 | 2.76 × 102 | 2.36 × 102 | 1.05 × 108 | 2.76 × 104 | 2.36 × 104 |

| RAP | 7.0 × 103 | 9.04× 10−2 | 8.34 × 10−2 | 7.0 × 103 | 9.04 × 10−2 | 8.34 × 10−2 |

In set-up 2 (drug dose, Covid-19 infection), the estimated PNEC values for all the three different exposure routes studied is quite similar to those observed for set-up 1. The sequence of exposure followed (maximum to minimum): fish consumption exposure only > combined ingestion of water and through fish consumption exposure > ingestion of water only (Table 3). Similar PNEC values obtained for the two set-ups could be attributed to variation in the values of input parameters considered, for instance, exposure duration value was taken as 70 years for normal drug dose whereas, ED of 1 year was assumed for Covid-19 infection. The similarity is also due to average lifetime, AT values taken for both these set-ups.

Comparative analysis study of the exposure routes indicated that PNECfish values are relatively higher compared to PNECRA and PNECfish+RA under the conditions assumed in this study. Higher PNECfish values may be attributed to low BCF values of the pharmaceutical drugs considered. Previous research studies have also reported high PNEC values in fishes for antibiotics like ciprofloxacin, azithromycin, erythromycin, etc. (Al-Khazrajy and Boxall, 2016; Schwab et al., 2005). The results revealed that consumption of fishes is unlikely to be the major route of exposure to humans for pharmaceutical drugs considered. Amongst the pharmaceutical drugs, RIB has the highest reported PNEC values for three different routes analyzed thus, its presence in either contaminated water or in fishes is unexpected to cause any health effects on humans. Lowest PNEC value indicates drug-of-concern for a given exposure pathway. The lower the PNEC values, higher is the concern. The lowest PNEC values are shown in bold text and have been italicized in the table provided below.

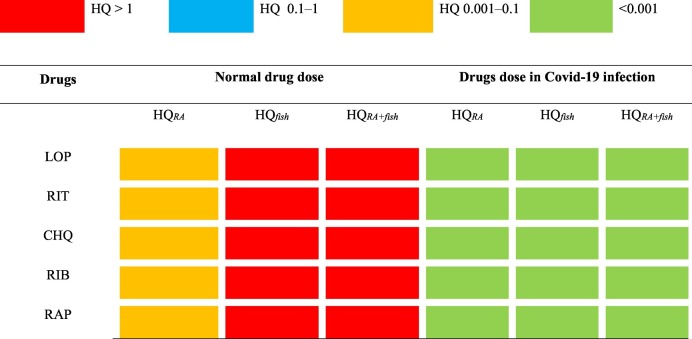

3.4. Risk estimation and characterization

3.4.1. Risk estimation of individual pharmaceutical drugs

Health risk assessment of individual pharmaceutical drugs was conducted for two different set-ups for three different exposure routes as mentioned above. Under set-up 1, HQ values were estimated using the calculated PEC values for normal drug dose conditions. Similarly, for set-up 2, PEC values for Covid-19 infection was used (Table 2). For set-up 1, HQRA in adults ranged from 3.6 × 10−3 (for RIT) to 3.6 × 10−4 (for RIB) which was lower than the acceptable risk level. HQfish values for all the pharmaceutical drugs were observed to be more than 1 with ritonavir showing the highest HQ values (HQ = 313.90) and chloroquine the lowest (HQ = 10.89). The estimated HQ values of pharmaceutical drugs was observed to be very high than the acceptable risk level. Consumption of fishes leads to higher risks than the accidental ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities. For the combined exposure due to the accidental ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities and through fish consumption, HQRA+fish values ranged from 337.68 (for RIT) to 11.83 (for CHQ). This indicates that HQ values of the pharmaceutical drugs were found to be more than 1 with ritonavir showing the highest HQ values. Amongst all, the maximum risk occurs due to the combined exposure to contaminated water and fish consumption, indicating possible health risk to humans.

For set up-2 (Covid-19 infection): similar to the above case here also HQRA values of adults were observed to be less than 1 for all the studied pharmaceutical drugs, indicating that no significant health risks exists to human for the accidental ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities. Similarly, HQfish and HQRA+fish values of adults were also less than the acceptable risk level for all the pharmaceutical drugs. Overall, it was observed that the pharmaceutical drugs do not show any significant human health risks for the three different exposure routes studied (HQs < 1).

The outcomes of this assessment show that the occurrence of low levels of pharmaceuticals drugs in surface waters pose no appreciable risk to human health during the accidental ingestion of contaminated water for both the set-ups considered. Earlier studies have also reported no adverse effect to human health from exposure to trace quantities of pharmaceuticals in drinking water or surface water (Schulman et al., 2002; Webb et al., 2003; Bercu et al., 2008). The combined route to contaminated water during recreational activities and consuming fishes grown in contaminated water pose maximum risks to human health under the conditions and assumptions used in this work. This is mainly because at the moment no specific treatment methods are available which can remove these pharmaceuticals from wastewater effluents (Osborne et al., 2020). The untreated effluents are discharged into the surrounding water-bodies and via food chain transfer the drugs can enter into aquatic organisms and gets accumulated in their muscles and tissues. The high HQ levels of pharmaceuticals observed in this study under the assumptions used can be indicative of the bio-accumulative potential of the drugs in fish tissues which on consumption by humans leads to potential health risks (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

HQ values of individual pharmaceutical drugs for risks to human health.

3.4.1.1. Total HQ estimation

As we know that under the current Covid-19 pandemic, number of cases are increasing day by day which has increased the consumption of drugs creating an additional burden to the existing pollution load in water. It is important to estimate health risks considering both the set-ups to get a realistic HQ values which will help in better assessing the associated human health risks. For this purpose, total HQ values of individual pharmaceutical drugs were calculated by summing up the observed HQ values in set-up 1 and set-up 2. The calculated HQtotal of pharmaceutical drugs is given in Table 5 .

Table 5.

A summary of total risk estimates due to exposure of single pharmaceutical for different exposure routes.

| Drugs | HQtotal, route 1 | HQtotal, route 2 | HQtotal, route 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOP | 2.6 × 10−3 | 222.53 | 239.81 |

| RIT | 3.65 × 10−3 | 313.90 | 337.68 |

| CHQ | 1.44 × 10−4 | 10.89 | 11.84 |

| RIB | 3.66 × 10−4 | 13.89 | 16.28 |

| RAP | 3.12 × 10−3 | 241.64 | 261.93 |

For the accidental ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities, HQtotal of individual pharmaceutical drugs were less than 1 and falls within the acceptable risk level (HQtotal < 1). This indicates that the accidental ingestion of contaminated surface water does not pose any risks to human health. For fish consumption exposure, HQtotal values of pharmaceutical drugs ranged from 313.90 (for RIT) to 10.89 (for CHQ) and are very high, exceeding the acceptable risk levels. RIT, RAP, and LOP emerged as the top three pharmaceutical drugs. Higher values of these pharmaceuticals can be due to high PECs/PNECs ratio. For the combined exposure to inadvertent ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities, calculated HQtotal values of all pharmaceutical drugs were higher than 1 (HQtotal > 1) and exceeded the acceptable risk levels (Table 5). Amongst the three exposure routes, no health risk exists to humans for exposure to ingestion of contaminated water. Higher risk effects of exposure come through the combined ingestions of contaminated water and fish consumption than through consuming fishes grown in contaminated water under the conditions assumed this work. The results obtained in this study gives a vital information as none of the studies reported on Covid-19 has considered and investigated the risk assessment aspect of ‘repurposed’ pharmaceutical drugs involved for any of the exposure routes studied. Though in some occasions the risk estimates were observed to be less than 1 and display no health effects, however, continuous monitoring of these pharmaceutical drugs in water and fishes is required.

3.4.2. Effects of co-existence on risk due to pharmaceutical drugs

HI interaction values were calculated to determine the effects of co-existence of pharmaceutical drugs (Kumari and Kumar, 2020a). It was observed that combined exposure of pharmaceutical drugs through the accidental ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities gives higher HQ values than the other two exposure routes therefore, the risk exposure effects of co-existence of pharmaceutical drugs was investigated considering this particular route only (Table 6). The results revealed that the HIint values for mixture combinations ranged from 295.42 (for LOP + RIT) to 1.20 (for CHQ + RAP). HIint values more than 1 indicates possible health risks and significant concerns due to the co-occurrence of pharmaceutical drugs in water under the assumptions applied in this study. Higher HIint values can be attributed to obtained high HQ values of single pharmaceutical drugs. Previous studies have also reported even higher HIint values for nanoparticle exposure (Parsai and Kumar, 2020). The findings of this study can provide an important information about health risk issues due to the co-exposure of pharmaceutical drugs in water. Co-occurrence of pharmaceutical drugs in water shows detrimental effects to human health and needs to be monitored.

Table 6.

A summary of calculated risk during the combined exposure to pharmaceutical drugs for the accidental ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities and through fish consumption.

| Binary mixtures of drugs | HQi | HQj | HQadd | Bij | HIint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOP + RIT | 239.81 | 337.68 | 536.45 | 1 | 295.42 |

| LOP + CHQ | 239.81 | 11.83 | 251.64 | 0.75 | 84.88 |

| LOP + RIB | 239.81 | 16.27 | 256.08 | 0 | 29.25 |

| LOP + RAP | 239.81 | 261.93 | 501.74 | 0 | 59.89 |

| RIT + CHQ | 337.68 | 11.83 | 349.52 | 0.75 | 102.12 |

| RIT + RIB | 337.68 | 13.90 | 353.96 | 0 | 35.36 |

| RIT + RAP | 337.68 | 261.93 | 599.61 | 0 | 83.74 |

| CHQ + RIB | 11.83 | 11.83 | 28.11 | 0 | 2.92 |

| CHQ + RAP | 11.83 | 261.93 | 273.76 | 0 | 1.20 |

| RIB + RAP | 16.27 | 261.93 | 278.21 | 0 | 1.91 |

3.4.3. Risks of background contaminants with individual pharmaceutical drugs

Table 7 provides summary information on the calculated comprehensive risks due to the hypothetical exposures of background contaminants and pharmaceutical drugs in water. HQadd was estimated assuming that dose addition assumption holds true for the interaction of background contaminants with individual pharmaceutical drugs. In this particular study, HQ values of the top three pharmaceutical drugs (LOP, RIT and RAP) is considered. The study observed that HQadd for all the possible binary mixture combinations was found to be less than 1 (Table 7). This indicated that no significant health risk effects exist to humans due to the presence of these background contaminants in water environment. Though insignificant risk was witnessed using dose-addition approach, still more specific studies using the USEPA weight-of-evidence approach need to be performed to attain precision in risk estimates.

Table 7.

Comprehensive risk due to hypothetical exposures of background contaminants present in water and pharmaceutical drugs considered in this study under the conditions assumed.

| Mixture of contaminants in water | HQ1⁎ | HQ2# | HQadd |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIP + RIT | 1.40 × 10−2 | 3.65 × 10−3 | 1.80 × 10−3 |

| CIP + RAP | 1.40 × 10−2 | 3.12 × 10−3 | 1.71 × 10−3 |

| CIP + LOP | 1.40 × 10−2 | 2.65 × 10−3 | 1.66 × 10−3 |

| NOR + RIT | 1.24 × 10−9 | 3.65 × 10−3 | 3.65 × 10−3 |

| NOR + RAP | 1.24 × 10−9 | 3.12 × 10−3 | 3.11 × 10−3 |

| NOR + LOP | 1.24 × 10−9 | 2.65 × 10−3 | 2.66 × 10−3 |

HQ1⁎ indicates background contaminants; HQ2# indicates pharmaceutical drugs considered in this study.

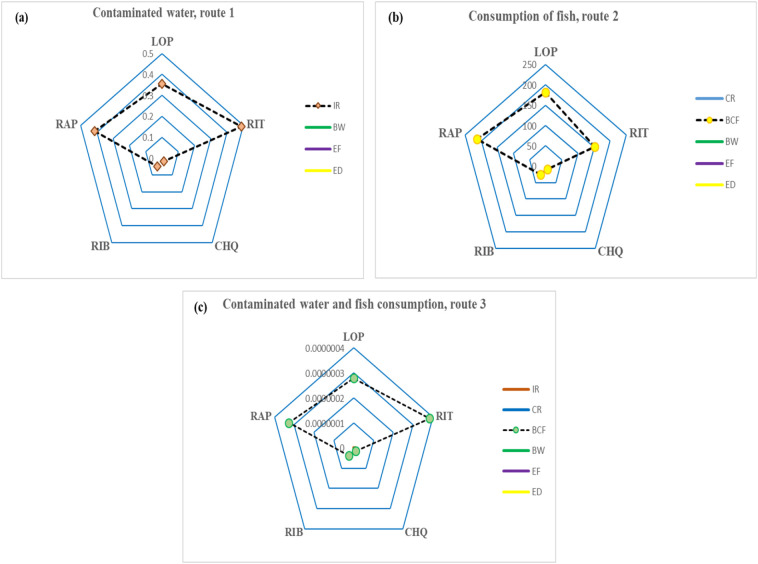

3.5. Sensitivity analysis to determine the effects of variables on risk analysis

Sensitivity index analysis was carried out to identify the effect of variables on risk estimates for the three different exposure routes. The results of sensitivity index analysis for the three exposure routes is depicted using spider chart diagram as given in Fig. 3 . For route-1 (the accidental ingestions of contaminated water during recreational activities), IR showed highest sensitivity and appeared as the major parameter affecting risk estimates which was closely followed by body weight, BW (Fig. 3a). For fish consumption exposure (route 2), BCF has the highest sensitivity index values and showed major effects on calculated HQ values (Fig. 3b) followed by BW, EF, ED, and CR. Similarly, for route-3 (combined ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities and fish consumption exposure), BCF has the maximum sensitivity index values which was followed by water intake rate (Fig. 3c). Sensitivity index of variables were in the sequence of BCF > IR > BW > EF > ED > CR. The findings of this study indicate that a variation in BCF values was observed to have significant effects on HQ, and is the most sensitive variable amongst all studied. A variation in BCF values can either lead to an increase or decrease in estimated HQ values. Body weight was the second most sensitive parameter affecting HQ values. Previous studies have also suggested the influence of body weight on risk estimates for oral ingestion of drinking water (Kumari and Kumar, 2020a; Kumar and Xagoraraki, 2010).

Fig. 3.

Sensitivity index analysis of HQ variables of pharmaceutical drugs for three different exposure routes.

3.6. Uncertainty in risk assessment

An understanding of uncertainty in risk assessment studies is important in conveying the likelihood of an adverse event or the magnitude of its consequences (Kumari and Kumar, 2020a; Kumari and Gupta, 2018). Reductions in uncertainty do not change the risks, but they increase the mathematical precision of evaluation. It is necessary to address the uncertainty associated with risk assessment studies (Parsai and Kumar, 2020; Kumari et al., 2015). Uncertainty may also arise due to variation in input parameters used to estimate PECs and PNECs for risk estimation. Some of these are discussed below.

-

•

Uncertainty may arise due to scarcity of environmental occurrence data of drugs considered. Because of beneficial health effects and economic importance of these pharmaceutical drugs, the best available evidence should be used to fully evaluate any additional actions that may be required to reduce environmental burden as a result of perceived human health risks. A thorough monitoring and analysis of these drugs is required to achieve more clarity on the data obtained.

-

•

DF is another parameter which creates uncertainty in data analysis. For consumer products, an average DF value of 10 is recommended for sewage from municipal wastewater treatment plants (Al-Khazrajy and Boxall, 2016). This is the default value and should be used only if no specific data are available. This study applied the default value to predict the concentrations of drug in surface water. For specific studies, the value of DF may vary depending on treatment methods used to treat wastewater.

-

•

Amongst all parameters used in PEC estimation, variability of the results might occur due to variation in parameters like Fexec and FWWTP. Regarding excretion rate, several published literatures have reported different excretion factors for each pharmaceutical drug. The obtained differences can possibly be due to genomically distinct absorbing capabilities, different modes of administration, gender, age, and health conditions of the studied inhabitants (Wishart et al., 2018). In contrast, removal rates of pharmaceuticals in WWTPs principally depend on the nature and characteristics (hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity) of the substances. Hydrophilic substances are generally a part of treated effluents and hydrophobic ones in the sludge. Expected removals in WWTPs can be deduced to a certain extent using the degradation rates and Kow values of the substances (Lindim et al., 2016).

-

•

BCF is an important parameter to estimate the concentrations of pharmaceutical drugs in fish tissues. Several regression equations have been reported in scientific literature to calculate BCF values (Lindim et al., 2016; Veith et al., 1979; Mackay, 1982). In this study BCF values are determined using pKa and logKow of the contaminants, and lipid fraction of the organism but the available regression equations do not consider the lipid content involved which may lead to some kind of uncertainty in BCF values.

-

•

ADI is another parameter which needs to be studied carefully. Due to lack of information on ADI values of the pharmaceutical drugs, this study used the NOAEL or NOEL values in rats to determine the ADI values, and transition to humans was made using a safety factor which might add uncertainty in risk estimates. Specific human based studies in vivo are required and must be carried out to avoid inaccuracy in risk estimates.

-

•

The estimated HQ values show the point estimate of the magnitude of probable risk due to the three exposure routes. Apart from water intake rate and BCF values, HQ values mostly depends on ADI values, and are anticipated to vary around point estimate depending on variability of ADI. Therefore, it is necessary and significant to provide uncertainty bounds to point estimate values of HQ for different pharmaceutical drugs analyzed.

4. Summary and conclusions

-

1)

RIB has the highest consumption rate which is indicated by their high concentrations (PEC values = 3840 μg L−1) in surface water and in fishes (2245 μg Kg−1) Therefore, regular monitoring of must be carried out in water and in fishes to protect the human health from their adverse health effects.

-

2)

High risk values (HQ > 1) were obtained for the combined exposure to the accidental ingestion of contaminated water during recreational activities and fish consumption than the other two exposure routes, indicating significant concerns to human health. Amongst the pharmaceutical drugs studied, RIT is expected to pose adverse health effects followed by RAP and LOP. Our findings indicate that RIT emerged as the priority contaminant which needs to be regularly monitored in wastewater effluents discharged to nearby rivers and lakes to reduce risks.

-

3)

Mixture toxicity risk exposure analysis revealed also showed high HI interaction values (HIint > 1) for all the studied combinations. Total risk assessment revealed that the presence of background contaminants in the water environment does not pose any significant risk to humans. Proper drug-drug interaction data (synergistic/antagonistic effects) must be taken into account for future risk assessment studies.

-

4)

Sensitivity analysis index showed that BCF (SI = 181.80) and intake rate (0.35) are the two most sensitive variable affecting risk estimates, the contribution of other variables was found to be insignificant.

5. Implications and future work

Regular and seasonal monitoring of receiving surface/ground water bodies and drinking water supplies for the presence of drugs is required to reduce spatial and temporal variability in drugs concentration. Continuous monitoring of priority contaminants in surface water must be carried out to protect aquatic organisms and human beings from their prolonged exposure and subsequent adverse health effects. The results presented in this study indicate only point estimates which might have added uncertainty in risk estimates (Kumari and Kumar, 2020a; Kumar and Xagoraraki, 2010). Therefore, to reduce uncertainty and variability in risk assessment, Monte Carlo based simulation study must be carried out in future risk studies. There is an urgent need for establishment of PNECs based on experimental data, and the consequences involved in not regulating releases of pharmaceutical drugs into the environment could further escalate a problem that might reach very serious proportion under the current Covid-19 pandemic. Research investigations must be carried out to determine ADI values based on appropriate toxicological studies to determine risk estimates, and to reduce variability in evaluating HQ values for characterizing the risk (Kumar and Xagoraraki, 2010). Due to limited information available on drug-drug interaction data of the pharmaceutical drugs, we have used dose addition approach to calculate total risk exposure of additional background contaminants in water environment. There is a need to use weight of evidence approach to conduct human health risk evaluation of these drugs in either binary or tertiary mixture using drug-drug interaction data and magnitude of interaction. Many risk assessment approaches, particularly those focused on human health protection, are based on the assumption of binary pair toxicity predicting the mixture effects of an overall mixture. In an environmental context where there are so many potential combinations might often be present as unidentified components and it is difficult to address all of binary mixtures at a time. To address this problem, certain approaches or rank based system can be developed to assess the risk due to the exposure of binary mixture of samples in contaminated water.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Values of parameters to estimate human health effects.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Minashree Kumari: Conceptualization, Organization, Data collection and analysis, Writing - original draft and editing.

Arun Kumar: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology (Delhi, India) for supporting this study. The work carried is a part of the corresponding author (Dr. Minashree Kumari) research from her Post-Doctoral work.

Editor: Dimitra A Lambropoulou

References

- Abafe O.A., Spath J., Fick J., Jansson S., Buckley C., Stark A., Pietruschka B., Martincigh B.S. LC-MS/MS determination of antiretroviral drugs in influents and effluents from wastewater treatment plants in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Chemosphere. 2018;200:660–670. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.02.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khazrajy O.S.A., Boxall A. Risk-based prioritization of pharmaceuticals in the natural environment in Iraq. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016;23:15712–15726. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6679-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bercu J.P., Parke N.J., Fiori J.M., Meyerhoff R.D. Human health risk assessments for three neuropharmaceutical compounds in surface waters. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2008;50:420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns E.E., Carter L.J., Kolpin D.W., Thomas-Oates J., Boxall A.B.A. Temporal and spatial variation in pharmaceutical concentrations in an urban river system. Water Res. 2018;137:72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K., Kim Y., Park J., Park C.K., Kim M., Kim H.S., Kim P. Seasonal variations of several pharmaceutical residues in surface water and sewage treatment plants of Han River, Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 2008;405:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C.M., Cheng V.C.C., Hung I.F.N., Wong M.M.L., Chan K.H., Kao R.Y.T., Poon L.L.L., Wong C.L.P., Guan Y., Peiris J.S.M., Yuen K.Y., HKU/UCH SARS Study Group Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: initial virological and clinical finding. Thorax. 2004;59(3):252–256. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colson P., Rolain J.M., Lagier J.C., Brouqui P., Raoult D. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as available weapons to fight COVID-19. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;105932 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagens A., Sigfrid L., Cai E., et al. Scope, quality, and inclusivity of clinical guidelines produced early in the covid-19 pandemic: rapid review. BMJ. 2020;369:1936. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dankovic, D A, Naumann B D, Maier, A, Dourson, M L, Levy, L S, 2015. The Scientific Basis of Uncertainty Factors Used in Setting Occupational Exposure Limits. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 12(sup1), S55-S68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dennis, M J, Wilson, L A, Nitrates and nitrites. In book: Encyclopedia of food sciences and nutrition, Editor-in-chief: Benjamin Caballero. 2nd Edition, pp 4136–4141. Academic Press, (2003) ISBN 978–0–12-227055-0.

- Ducharme J., Farinotti R. Clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism of chloroquine. Focus on recent advancements. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1996;31(4):257–274. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199631040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards M., Topp E., Metcalfe C.D., Li H., Gottschall N., Bolton P., Curnoe W., Payne M., Beck A., Kleywegt S. Pharmaceutical and personal care products in tile drainage following surface spreading and injection of dewatered municipal bio-solids to an agricultural field. Sci. Total Environ. 2009;407:4220–4230. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elflein J. COVID-19 incidence rate in the U.S. from January 22 to May 30, 2020, by age. 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1112993/covid-19-incidence-rate-us-by-age/

- Elflein J. Statistica; 2020. Canada: COVID-19 cases by province. [Cited 2020 May 12] [Google Scholar]

- EMEA (2006) Guideline on the environmental risk assessment of medicinal products for human use. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. EMEA/CHMP/SWP/4447/00. (December), 1-12.

- European Commission, Technical guidance document in support of Commission Directive 93/67/EEC on Risk assessment for new notified substances and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1488/94 on Risk assessment for existing substances and Commission Directive (EC) 98/ 8 on Biocides, 2nd Ed. European Commission, Luxembourg, Part 1, 2 and 3, 760p (2003).

- Fent K., Weston A., Caminada D. Ecotoxicology of human pharmaceuticals. Aquat. Toxicol. 2006;76:122–159. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick J., Lindberg R.H., Tysklind M., Larsson D.G.J. Predicted critical environmental concentrations for 500 pharmaceuticals. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010;58:516–523. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franquet-Griell H., Gómez-Canela C., Ventura F., Lacorte S. Predicting concentrations of cytostatic drugs in sewage effluents and surface waters of Catalonia (NE Spain) Environ. Res. 2015;138:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franquet-Griell H., Gómez-Canela C., Ventura F., Lacorte S. Anticancer drugs: consumption trends in Spain, prediction of environmental concentrations and potential risks. Environ. Pollut. 2017;229:505–515. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung T.S., Liu D.X. Human coronavirus: host-pathogen interaction. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;73(2019):29–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-020518-115759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibs J., Heckathorn H.A., Meyer M.T., Klapinski F.R., Alebus M., Lippincott R.L. Occurrence and partitioning of antibiotic compounds found in the water column and bottom sediments from a stream receiving two wastewater treatment plant effluents in Northern New Jersey. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;458-460:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilsenan, M B, Additives in Dairy foods, In book: Encyclopedia of dairy sciences, Editor-in-chief: John W. Fuquay. 2nd Edition, pp 55–60. (2011) Academic Press ISBN 978-0-12-374407-4.

- Gómez-Canela, C, Pueyo, V, Barata, C, Lacorte, S, Maria Marcé R, 2019. Development of predicted environmental concentrations to prioritize the occurrence of pharmaceuticals in rivers from Catalonia. Sci. Total Environ 57–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gordon D.E., Jang G.M., Bouhaddou M., Xu J., Obernier K., et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M.C., Geoghegan L., Arbyn M., Mohammed Z., McGuinness L., Clarke E.L., Wade R.G. The prevalence of symptoms in 24,410 adults infected by the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis of 148 studies from 9 countries. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros M., Petrović M., Ginebreda A., Barcelo D. Removal of pharmaceuticals during wastewater treatment and environmental risk assessment using hazard indexes. Environ. Int. 2010;36:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J., Sinclair C.J., Selby K., Boxall A.B.A. Toxicological and ecotoxicological riskbased prioritization of pharmaceuticals in the natural environment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016;35:1550–1559. doi: 10.1002/etc.3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horby P., Mafham M., Linsell L., et al. medRxiv (2020) 2020. Effect of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: preliminary results from a multi-centre, randomized, controlled trial. published online July 15. (preprint) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt, S, Ollinger, J, Arce, G, Bui, Q, Tobia, A J, vanRavenswaay, B, Dialkyldithiocarbamates (EBDCs)-Dose response In book: Hayes' Handbook of Pesticide Toxicology (Third Edition), Chapter, pp 1689-1710, Edited by Robert Krieger, (2010), Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-374367-1.

- Krishnan M. Covid-19 vaccine: can India balance local and international demand? 2021. https://p.dw.com/p/3nmtn

- Kumar A., Xagoraraki I. Human health risk assessment of pharmaceuticals in water: an uncertainty analysis for meprobamate, carbamazepine, and phenytoin. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010;57(2–3):146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari M., Gupta S.K. Age dependent adjustment factor (ADAF) for the estimation of cancer risk through trihalomethanes (THMs) for different age groups- a innovative approach. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018;148:960–968. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari M., Kumar A. Human health risk assessment of antibiotics in binary mixtures for finished drinking water. Chemosphere. 2020;240:124864. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari M., Kumar A. Identification of component-based approach for prediction of joint chemical mixture toxicity risk assessment with respect to human health: a critical review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020;143:111458. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari M., Gupta S.K., Mishra B.K. Multi-exposure cancer and non-cancer risk assessment of trihalomethanes in drinking water supplies - a case study of Eastern region of India. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015;113:433–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis, W G, Sofield, R M, Yu, M H, 2011. Introduction to Environmental Toxicology: Molecular Structures to Ecological Landscapes (Fourth Ed.) Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Pp. 117–162. ISBN 978-1-4398-0410-0.

- Lindim C., van Gils J., Georgieva D., Mekenyan O., Cousins I.T. Evaluation of human pharmaceutical emissions and concentrations in Swedish river basins. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;572:508–519. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Wang X.J. Potential inhibitors against 2019-nCoV coronavirus M protease from clinically approved medicines. J Genet. Genomics. 2020;47:119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Xi, Chen H., Shang Y., Zhu H., Chen G., Chen Y., Liu S., Zhou Y., Huang M., Hong Z., Xia J. Efficacy of chloroquine versus lopinavir/ritonavir in mild/general COVID-19 infection: a prospective, open-label, multicenter, randomized controlled clinical study. Trials. 2020;21:622. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04478-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Li M., Wu M., Li Z., Liu X. Occurrence ad regional distributions of 20 antibiotics in water bodies during groundwater recharge. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;518-519:498–506. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.02.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay D. Correlation of bioconcentration factors. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1982;16:274–278. doi: 10.1021/es00099a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood A.R., Al-Haideri H.H., Hassan F.M. Detection of antibiotics in drinking water treatment plants in Baghdad City, Iraq. Adv. Public Health. 2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/7851354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Migliore L., Cozzolino S., Fiori M. Phytotoxicity to and uptake of enrofloxacin in crop plants. Chemosphere. 2003;52:1233–1244. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH, 2020. National Institute of Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, accessed on 11th October 2020 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04341675.

- Nukoolkarn V., Lee V.S., Malaisree M., Aruksakulwong O., Hannongbua S. Molecular dynamic simulations analysis of ritonavir and lopinavir as SARS-CoV 3CL(pro) inhibitors. J. Theor. Biol. 2008;254:861–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omarjee L., Janin A., Perrot F., Laviolle B., Meilhac O., Mahe G., et al. Targeting T-cell senescence and cytokine storm with rapamycin to prevent severe progression in COVID-19. Clin. Immunol. 2020;216 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne V., Davies M., Lane S., et al. Lopinavir–ritonavir in the treatment of COVID-19: a dynamic systematic benefit–risk assessment. Drug Saf. 2020;43:809–821. doi: 10.1007/s40264-020-00966-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio V., Larrañaga A., Aceña J., Perez S., Barcelo D. Concentration and risk of pharmaceuticals in freshwater systems are related to the population density and the livestock units in Iberian Rivers. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;540:267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.06.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan M., Chu L.M. Phytotoxicity of veterinary antibiotics to seed germination and root elongation of crops. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016;126:228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsai P., Kumar A. Tradeoff between risks through ingestion of nanoparticle contaminated water or fish: human health perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;740:140140. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradat P., Virlogeux V., Gagnieu M.-C., Zoulim F., Bailly F. Ribavirin at the era of novel direct antiviral agents for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection: relevance of pharmacological monitoring. Adv. Hepatol. 2014;493087 doi: 10.1155/2014/493087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rabi F.A., Zoubi M.S., Kasasbeh G.A., Salameh D.M., Al-Nasser A.D. SARS-CoV-2 and coronavirus disease 2019: what we know so far. Pathogens. 2020;9(3):231. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9030231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman L.J., Sargent E.V., Naumann B.D., Faria E.C., Dolan D.G., Wargo J.P. A human health risk assessment of pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment. Hum. Ecol. Risk. Assess. 2002;8(4):657–680. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab B.W., Hayes E.P., Fiori J.M., Mastrocco F.J., Roden N.M., Cragin D., Meyerhoff R.D., D’Aco V.J., Anderson P.D. Human pharmaceuticals in US surface waters: a human health risk assessment. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2005;42:296–312. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V.K., Johnson N., Cizmas L., McDonald T.J., Kim H. A review of the influence of treatment strategies on antibiotic resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes. Chemosphere. 2016;150:702–714. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.12.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh T.U., Parida S., Lingaraju M.C., Kesevan M., Kumar D., Singh R.K. Drug repurposing approach to fight COVID-19. Pharmacol. Rep. 2020;5:1–30. doi: 10.1007/s43440-020-00155-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohaili, S K, Muniyandi, R, Mohamad, R, 2017. Dose response and exposure assessment of household hazardous waste, Chapter 2, In book Household hazardous waste management, Edited by Daniel Mmereki.

- Sukul P., Spiteller M. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics in the environment. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2007;191:131–162. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-69163-3_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA, 2000. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Methodology for Deriving Ambient Water Quality Criteria for the Protection of Human Health. Oyce of Water, Oyce of Science and Technology. EPA-822-B-00-004, October 2000.

- U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency) Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation; Washington DC: 2009. Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund Vol I: Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part F, Supplemental Guidance for Inhalation Risk Assessment) [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency) Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation; Washington DC: 2009. Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund Volume 1: Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part F, Supplemental Guidance for Dermal Risk Assessment) [Google Scholar]

- US EPA . Environmental Fate and Effects Division, Office of Pesticide Programs, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; Washington, D.C.: 2009. KABAM Version 1.0 (Kow (Based) Aquatic BioAccumulation Model) [Google Scholar]

- Veith G.D., DeFoe D.L., Bergstedt B.V. Measuring and estimating the bioconcentration factor of chemicals in fish. J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 1979;36:1040–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Che B., Duan A., Mao J., Dahlgren R.A., Zhang M., et al. Toxicity evaluation of β-diketone antibiotics on the development of embryo-larval zebrafish (Danio rerio) Environ. Toxicol. 2014;29:1134–1146. doi: 10.1002/tox.21843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30(3):269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb S., Ternes T., Gibert M., Olejniczak K. Indirect human exposure to pharmaceuticals via drinking water. Toxicol. Lett. 2003;142:157–167. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(03)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellington E.M., Boxall A.B., Cross P., Feil E.J., Gaze W.H., Hawkey P.M., et al. The role of the natural environment in the emergence of antibiotic resistance in Gram negative bacteria. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013;13:155–165. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70317-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2020a Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID19-March 2020 (accessed 29 September, 2020).

- WHO, 2020b, statistics coronavirus. https://www.google.com/search?q=who+statistics+coronavirus&rlz=1C1CHBF_enIN737IN740&oq=WHO&aqs=chrome.0.69i59j69i57j69i59l2j35i39j0i131i433l2j69i61.1991j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 (accessed October 21, 2020).

- WHO. “Solidarity” clinical trial for COVID-19 treatments. Latest update on treatment arms. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/global-research-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/solidarity-clinical-trial-for-covid-19-treatments (accessed October 10, 2020). 2020c.

- WHO Landscape analysis of therapeutics. 2020. https://www.who.int/blueprint/priority-diseases/key-action/Table_of_therapeutics_Appendix_17022020.pdf?ua=1

- Wishart D.S., Feunang Y.D., Guo A.C., Lo E.J., Marcu A., Grant J.R., et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:1074–1082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollenberger L., Halling-Sørensen B., Kusk K.O. Acute and chronic toxicity of veterinary antibiotics to Daphnia magna. Chemosphere. 2000;40:723–730. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(99)00443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood T.P., Duvenage C.S.J., Rohwer E. The occurrence of anti-retroviral compounds used for HIV treatment in South African surface water. Environ. Pollut. 2015;199:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Zhang G., Li X., Zou S., Li P., Hu Z., Li J. Occurrence and elimination of antibiotics at four sewage treatment plants in the Pearl River Delta (PRD), South China. Water Res. 2007;41:4526–4534. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z., Lu G., Ye Q., Liu J. Long-term effects of antibiotics, norfloxacin, and sulfamethoxazole, in a partial life-cycle study with zebrafish (Danio rerio): effects on growth, development, and reproduction. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016;23:18222–18228. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L., Wang Y., Tong L., Deng Y., Li Y., Gan Y., Guo W., Dong C., Duan Y., Zhao K. Occurrence and risk assessment of antibiotics in surface water and ground water from different depths of aquifers: a case study at Jianghan Plain, Central China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017;135:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X., Ye F., Zhang M., Cui C., Huang B., Niu P. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Values of parameters to estimate human health effects.