Abstract

Aims

Effectiveness of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) for smoking cessation has not been evaluated in low income countries, such as Syria, where it is expensive and not widely available. We evaluated whether nicotine patch boosts smoking cessation rates when used in conjunction with behavioral support in primary care clinics in Aleppo, Syria.

Design

Two arm, parallel group, randomized, placebo controlled, double-blinded multi-site trial.

Setting

Four primary care clinics in Aleppo, Syria.

Participants

Two hundred and sixty-nine adult primary care patients received behavioral cessation counseling from a trained primary care physician and were randomized to receive six weeks of treatment with nicotine versus placebo patch.

Measurements

Primary end-points were prolonged abstinence (no smoking after a 2-week grace period) at end of treatment, and 6 and 12 months post-quit day, assessed by self-report and exhaled carbon monoxide levels of <10 p.p.m.

Findings

Treatment adherence was excellent and nicotine patch produced expected reductions in urges to smoke and withdrawal symptoms, but no treatment effect was observed. The proportion of patients in the nicotine and placebo groups with prolonged abstinence was 21.6% and 20.0%, respectively, at end of treatment, 13.4% and 14.1% at 6 months, and 12.7% and 11.9% at 12 months.

Conclusions

Nicotine patches may not be effective in helping smokers in low-income countries to stop when given as an adjunct to behavioural support.

Keywords: Effectiveness, nicotine patch, primary care, randomized controlled trial, smoking, Syria

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco kills more than five million people globally each year. This annual toll is expected to increase to 10 million within the next 20–30 years, with 80% of deaths occurring in developing countries [1]. In Syria, an Eastern Mediterranean region (EMR) nation of 23 million people, 57% of men and 17% of women smoke cigarettes [2]—quit rates are very low [2,3] and nicotine dependence is an important barrier to cessation [4]. To date, no clinical practice standards, specialty cessation clinics or pharmacological agents are available to assist them [4–6]. Since it’s inception in 2002, the Syrian Center for Tobacco Studies (SCTS; http://www.scts-sy.org) has conducted research to characterize, intervene on and guide policy on the tobacco epidemic in the EMR [2,7].

Given the efficacy of combined behavioral/ pharmacological cessation interventions in higher-income countries [8,9] there is great interest in Syria to integrate cessation services within primary care [5]. Primary care centers in Syria reach large numbers of smokers and physicians are viewed as credible sources of smoking cessation assistance [4]. This study is the first randomized smoking cessation effectiveness trial conducted in a low-income country setting.

METHOD

Study design

The study was a two-arm, parallel group, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded, multi-site trial conducted in primary care clinics in Aleppo, Syria. All patients received physician-delivered face-to-face behavioral counseling and brief telephone support, and were randomly assigned to receive either six weeks of active or placebo nicotine patch. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of The University of Memphis and Syrian Center for Tobacco Studies, and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01085032).

Patients

Patients resided in Aleppo, Syria’s second largest city, and were registered at one of four primary care centers participating in the study. Participants were 18–65 years of age and smoked ≥5 cigarettes/day for ≥1 year. Exclusion criteria were (i) a diagnosis of generalized dermatology disease, liver failure, hyperthyroidism or pheochromocytoma; (ii) current use of psychotropic drugs; (iii) past year history of drug or alcohol abuse; (iv) current unstable cardiovascular or psychiatric illness, or any other debilitating disease based on their physician’s assessment; (v) currently pregnant, lactating or intending to become pregnant during the next three months.

Primary care clinics

Four clinics were enrolled with the goal of including a broad range of patients in terms of socio-economic status, religion (Muslim, Christian) and ethnicity (Arabian, Armenian, Kurdish). We randomly selected 3 of 21 clinics operated by non-governmental organizations that provide a range of basic health services to low-and middle-income patients. A fourth private clinic was included to ensure representation of higher socio-economic status patients.

Procedures

Physician training

Physicians who provided adult primary care underwent two hours of training in brief intervention strategies [8] and were instructed on the study protocol. Each clinic had a cessation coordinator, a primary care physician who liaised between other physicians and staff to ensure the protocol was followed, and delivered the intervention to all interested patients. Eight physicians (seven males, one female) were trained for this role; one discontinued training voluntarily and another was judged not to have adequately mastered the protocol. Five physicians served as cessation coordinators throughout the study (one worked at each of three clinics and two shared this role at the other clinic) and another was kept in reserve but not used. Training lasted for six hours and included instruction in cognitive-behavioral cessation strategies through lectures, role plays and competency testing/certification. All cessation coordinators received ongoing group supervision from two physician trainers to ensure that standardized procedures were being followed (e.g. having patients record their smoking status on clinic intake forms and flagging smokers’ medical records to alert physicians to deliver a brief cessation intervention), audiotaped treatment sessions were reviewed and difficult cases were problem-solved.

Intervention delivery

Physicians were trained to deliver a brief ‘5A’-based intervention (ask, advise, assess, assist arrange) [8] to all smokers at each visit. Patients interested in quitting were referred by their physician to the cessation coordinator. Upon referral, the cessation coordinator described the study, screened and obtained written informed consent. Patients who were not interested and/or ineligible were provided with self-help materials and referred back to their physician.

Patients were then allocated to treatment using random permuted blocks stratified according to clinic and patient gender. Allocation assignments were contained in opaque, sequentially-numbered envelopes and were maintained in the biostatistics unit of the SCTS, a facility geographically separated from the clinics. A statistician, not otherwise involved in the trial, made each allocation after receiving a request from a cessation coordinator, prepared the treatment package, including patches, and had it delivered to the clinic. Patients, interventionists and data collectors were blind to allocation.

Patch was selected as the form of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) based on its ease of use, favorable side effects and contraindications profiles, it’s well-researched and documented efficacy [8], and acceptability to Syrian patients in our pilot work [4]. Patients in the nicotine condition received a six-week supply of Nicotinell™ patches, 24-hour dose, using a step-down algorithm. Patients who smoked ≥10 cigarettes/day received a 2-week supply of 21-mg patches, then a 2-week supply of 14-mg patches, then a 2-week supply of 7-mg patches. Patients who smoked 5–9 cigarettes per day received a 4-week supply of 14-mg patches, then a 2-week supply of 7-mg patches. Patients in the placebo condition received the same step-down algorithm. Placebo patches were provided by a local manufacturer. Prior to their use, placebo and nicotine patches were compared by 10 independent judges who rated the shape, size, color and packaging of the two types of patches as identical and were not able to correctly identify the patch type other than by chance.

All patients received behavioral cessation counseling using strategies shown to be effective in higher-income countries [8,10] and adapted for Syrian/Arab culture based on our formative work [4]. Three individual, in-person sessions (approximately 30 minutes each) and 5 brief (approximately 10-minute) phone calls, were delivered by the cessation coordinator. Intervention contacts began 4 days prior to, and ended 45 days after, quit day. All treatment, including patches, was provided at no cost. The treatment manual is included as online supporting information (Appendix S1).

Measures

Primary end-point

The primary end-point was prolonged abstinence from cigarettes at end of treatment (46 days post-quit day) and 6 and 12 months post-cessation assessed by self-report and exhaled carbon monoxide levels of <10 p.p.m. Prolonged abstinence is defined as complete abstinence after a two-week grace period following the quit day [11]. Criteria for the primary end-point conformed to the ‘Russell standard’ [12], with the exception that a self-report of any smoking (rather than allowing up to five cigarettes in total) was used to define loss of abstinence.

Our target enrolment was 250 patients to be powered to detect 12-month, biochemically-confirmed prolonged abstinence rates of 25% and 10% in the nicotine and placebo groups respectively (two-tailed test, alpha = 0.05, beta = 0.20).

Secondary end-point

Because it is commonly used in the cessation literature [8] we assessed seven day point prevalent abstinence, defined as no cigarette use during the past seven days at each follow-up, based on self-report and carbon monoxide levels of <10 p.p.m.

Baseline predictors

Socio-demographic variables included age, gender, marital status, years of education and religion. Tobacco-related variables included number of years as a cigarette smoker; current amount smoked; whether a cessation attempt lasting at least 24 hours had been made in the previous six months; the Readiness To Quit Ladder [13]; a single item, Likert-type scale assessing confidence in one’s ability to quit; the three subscales of the Smoking Self-Efficacy/Temptations Questionnaire (Long Form)—Positive Affect/Social Situations, Negative Affect Situations, and Habitual/Craving Situations [14]; the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) [15]; and current waterpipe use.

Time-varying predictors

At baseline, session 2 (7 days post-quit), session 3 (15 days post-quit), end of treatment (46 days post-quit), and at the 6- and 12-month follow-up sessions, we assessed perceived social support [16,17], depressive symptomatology using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [18,19] and tobacco withdrawal symptomatology using the Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS). We calculated the mean of eight scale items to obtain a total withdrawal score: anxiety, depression/feeling blue, difficulty concentrating, hunger, increased appetite, insomnia, irritability/ frustration/anger and restlessness [20–22]. We also used a single item ‘urges to smoke’, scored in the same manner.

To assess blindness during treatment, patients indicated during all in-person and phone contact whether they believed they had received nicotine or placebo patch.

Treatment process measures

Satisfaction with treatment was assessed at end of treatment using four items: ‘How did you feel about the smoking cessation program?’, ‘How helpful was the interventionist?’, ‘How well did the interventionist teach you the smoking cessation techniques?’ and ‘Were the smoking cessation techniques helpful in your quit attempt?’. Patients responded using four-point Likert-type scales.

Statistical analysis

Between-group differences in baseline characteristics, indices of treatment implementation, adherence, retention, safety, treatment perceptions and crude abstinence rates were assessed using χ2 or t-tests. Effects of nicotine and placebo patch on withdrawal symptoms and urges to smoke among patients with prolonged abstinence until the end of treatment were examined in repeated measures analyses of variance. To examine multivariable predictors of prolonged abstinence through 12 months, a generalized estimating equation (GEE) analysis for binary data was performed using PROC GENMOD in PASW Statistics version 18 (2009). This procedure allowed us to consider observations between patients as independent and observations within patients as correlated. Several baseline and time-varying variables were included, as indicated in Table 3. Analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis, with individuals with missing outcome data or self-reported abstinence not confirmed by carbon monoxide at any follow-up point classified as not quit.

Table 3.

Predictors of smoking status from end of treatment to 12-month follow-up determined by generalized estimating equation (GEE) logistic regression with available data.

| Odds Ratio | 95% OR | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline variables | |||

| Age | 1.02 | 0.98–1.07 | 0.251 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1.37 | 0.48–3.89 | 0.552 |

| Male | Ref | ||

| Treatment | |||

| Nicotine | 0.81 | 0.31–2.12 | 0.672 |

| Placebo | Ref | ||

| Treatment center | |||

| Center 4 | 2.36 | 0.49 | 0.285 |

| Center 3 | 3.22 | 0.81 | 0.098 |

| Center 2 | 1.49 | 0.46 | 0.511 |

| Center 1 | Ref | ||

| Water pipe smoking | |||

| Never | 1.32 | 0.24–7.28 | 0.746 |

| Previous | 0.63 | 0.05–7.95 | 0.724 |

| Current | Ref | ||

| Successful quit attempts | |||

| No | 1.29 | 0.35–4.67 | 0.701 |

| Yes | Ref | ||

| Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence | 0.86 | 0.65–1.13 | 0.284 |

| Motivation (how motivated are you to quit) | 0.92 | 0.59–1.42 | 0.695 |

| Confidence (how confident are you that you can quit smoking) | 1.27 | 1.03–1.58 | 0.026 |

| Self-efficacy positive affect/social situation | 1.06 | 0.89–1.27 | 0.507 |

| Self-efficacy/negative affect situations | 0.92 | 0.76–1.12 | 0.408 |

| Self-efficacy/habitual/craving situation | 1.02 | 0.85–1.22 | 0.851 |

| Time-varying variables | |||

| Social support score | 1.00 | 0.96–1.04 | 0.928 |

| Depression score | 1.00 | 0.96–1.03 | 0.790 |

| Total withdrawal symptoms score | 0.97 | 0.96–0.99 | 0.005 |

| Subject perception of treatment allocation | |||

| Nicotine | Ref | ||

| Placebo | 0.51 | 0.19–1.37 | 0.182 |

RESULTS

Study population

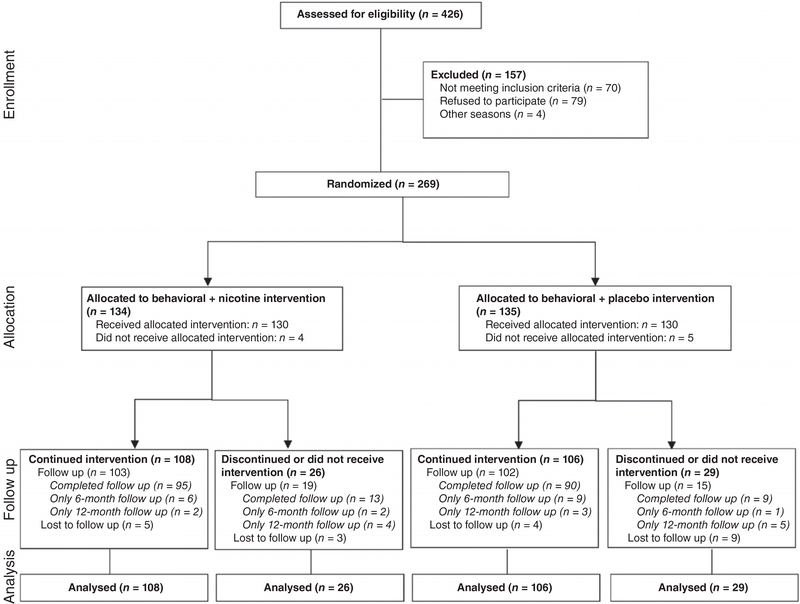

Recruitment began in June 2007 and ended in April 2008. Of approximately 1000 adult smokers treated during this time, 426 patients (43%) were referred by their physician to the cessation coordinator to assess eligibility for the trial. Of these, 70 did not meet eligibility criteria, 4 were missed and 83 refused to participate. Thus, 80% of referred, eligible patients consented to participate and were randomized, with 134 and 135 allocated to nicotine and placebo patch respectively (Fig. 1). The number of patients enrolled per clinic ranged from 33 to 99. Baseline characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient progression through the study

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by treatment condition.

| Placebo (n = 135) mean (SD) or % | Nicotine (n = 134) mean (SD) or % | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age (yrs) | 40.0 (11.4) | 39.9 (11.4) |

| Gender (% males) | 81.5 | 75.4 |

| Education (yrs completed) | 10.4 (4.1) | 10.2 (4.0) |

| Religion (% Muslim) | 74.8 | 74.6 |

| Marital status (% married) | 81.5 | 76.9 |

| Tobacco use | ||

| Amount smoked (cigarettes/day) | 27.4 (11.5) | 28.1 (13.9) |

| Age when smoked first cigarette | 17.9 (4.6) | 18.3 (4.9) |

| Age when began smoking smoked at least one cigarette/day | 18.6 (5.0) | 18.7 (5.6) |

| Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependencea | 5.6 (2.1) | 5.9 (2.3) |

| Carbon monoxide (p.p.m.) | 27.6 (15.7) | 27.4 (16.6) |

| Total withdrawal discomfort scoreb | 28.4 (17.9) | 29.5 (19.4) |

| Made quit attempt in last 6 months (%) | 31.9 | 32.1 |

| Readiness to quitc | 9.1 (1.3) | 8.9 (1.3) |

| Confidence in ability to quitd | 7.0 (2.3) | 6.9 (2.5) |

| Current water pipe user (%) | 11.1 | 10.4 |

| Psychosocial | ||

| Depression (CES-D) scoree | 17.2 (10.0) | 18.9 (10.2) |

| Social supportf | 44.8 (8.9) | 41.0 (11.2) |

Range of possible values for the Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence is 0–10.

Range of possible values for total withdrawal discomfort score is 0–100.

Range of possible values for readiness to quit is 0–10.

Range of possible values for confidence in ability to quit is 0–10.

Range of possible values for CES-D score is 0–60.

Range of possible values for the social support score is 0–60.

Treatment implementation, adherence and retention

All in-person sessions were audiotaped and a subsample was periodically reviewed by a researcher who was not involved in treatment delivery. A total of 25% of sessions was audited in this way, indicating that intervention was delivered accurately in more than 90% of sessions. Common examples of inaccurate delivery were not explaining printed self-help materials and not adequately assisting the patient to problem-solve tempting situations.

Adherence was very good, with 94%, 84% and 80% of patients completing in-person treatment sessions 1, 2 and 3 respectively. In 120 randomly sampled in-person sessions, the average session length was 32.6 minutes (range 9–88 minutes) and did not differ by treatment group (P = 0.14). Completion of telephone treatment sessions averaged 88% across the five contacts, ranging from 98% at call 1 to 75% at call 5, averaged 7 minutes/ session, with no differences observed between treatment groups (P-values > 0.35).

Adherence to patch use, defined as a self-report of having used one patch each day over the past week, averaged 93% and 89% in the nicotine and placebo groups respectively. A significant time by group difference was observed (P = 0.006), indicating a high level of adherence in both groups in weeks 1–3, which decreased in weeks 4–6 only in the placebo group.

Overall, 82% of patients was retained through the 12-month follow-up period (85% and 79% of nicotine and placebo patients, respectively; P = 0.72).

Effects of patch on withdrawal and urges to smoke

For the 56 patients (29 nicotine and 27 placebo) with prolonged abstinence through end of treatment, group by time effects were not statistically significant for either total withdrawal symptoms (P = 0.129) or urges to smoke (P = 0.095). A comparison of nicotine and placebo groups at each assessment point indicated that withdrawal and urges were similar at session 0 (7 days before patch use was initiated; P = 0.889 for withdrawal, P = 0.343) for urges) and at session 2 (7 days after patch use was initiated; P = 0.707 for withdrawal, P = 0.304 for urges). At session 3 (15 days after patch use was initiated) both withdrawal and urges were lower among those receiving nicotine than placebo (P = 0.043 and P = 0.017). At end of treatment, withdrawal was lower amongst patients receiving nicotine patch compared with placebo (P = 0.013), but urges did not differ significantly (P = 0.156).

End-points

Primary end-point

The crude proportions of patients in the nicotine and placebo groups with prolonged abstinence were 21.6% and 20.0%, respectively, at end of treatment, 13.4% and 14.1% at 6 months, and 12.7% and 11.9% at 12 months. Between-group differences were not statistically significant at any follow-up (all P-values > 0.75) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cessation rates at end-points.

|

End of treatmenta |

Six months |

Twelve months |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 135) | Nicotine (n = 134) | Placebo (n = 135) | Nicotine (n = 134) | Placebo (n = 135) | Nicotine (n = 134) | |

| Prolongedb | 20.0% | 21.6% | 14.1% | 13.4% | 11.9% | 12.7% |

| Seven-day point prevalentc | 25.9% | 25.4% | 19.3% | 14.2% | 14.8% | 20.1% |

P > 0.05 for all comparisons (between nicotine and placebo arms).

End of treatment analysis conducted at day 46 post-quit day.

Defined as no self-reported smoking and carbon monoxide <10 p.p.m. following a grace period of two weeks after the scheduled quit day.

Defined as no self-reported smoking for the seven days preceding the follow-up visit and carbon monoxide <10 p.p.m.

Secondary end-point

No significant between-group differences were found for seven-day point prevalent abstinence. The crude proportions of patients in the nicotine and placebo groups abstinent were 25.4% and 25.9%, respectively, at end of treatment, 14.2% and 19.3% at 6 months, and 20.1% and 14.8% at 12 months (Table 2).

Predictors of cessation

Prolonged abstinence was similar among the four clinics. Greater quitting confidence at baseline and experiencing less withdrawal during treatment were associated with a greater likelihood of prolonged abstinence over 12 months (Table 3). Interactions of treatment group with baseline number of cigarettes smoked per day, baseline FTND score, and use of water pipe during treatment were not significant (P-values = 0.661, 0.058 and 0.386 respectively).

Safety

Only two symptoms were reported in ≥5% of patients in either the nicotine or placebo group over the course of treatment, and these did not differ significantly by group. Sleep difficulties (insomnia, nightmares) occurred in 8.3% and 10.3% of the nicotine and placebo groups respectively. Skin redness/irritation occurred in 9.1% and 11.6% of the nicotine and placebo groups respectively.

Process evaluation

Patient perceptions about group assignment

The percentage of patients in the nicotine and placebo groups who believed they were receiving nicotine were 65.4% and 56.8%, respectively, at call 2 (P = 0.164); 59.5% and 54.5% at session 2 (P = 0.454), 69.2% and 51.8% at call 3 (P = 0.007), 64.6% and 51.0% at session 3(P = 0.043), 60.4% and 53.1% at call 4 (P = 0.288), and 54.1% and 48.4% at call 5 (P = 0.191).

Patient evaluations of the intervention

Patients in both the nicotine and placebo groups evaluated the intervention very positively, with 92% and 96%, respectively, rating their interventionist as ‘very helpful’ (P = 0.221); 92% and 97%, respectively, reporting that the interventionist taught the smoking cessation techniques ‘very well’ (P = 0.101); 88% and 97%, respectively, reporting that they liked the intervention program ‘a lot’ (P = 0.021), and 84% and 95%, respectively, reporting that the smoking cessation techniques were ‘very helpful’ (P = 0.028).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effectiveness of an evidence-based smoking cessation intervention in a low-income country. No treatment effect of nicotine patch was observed. Overall, 12% and 17% of patients achieved prolonged and past 7-day abstinence, respectively, at 1 year. These rates are lower than the estimated 23% point prevalence abstinence rate for nicotine patch observed in efficacy trials [8], but are consistent with effectiveness data from the UK, where 15% of patients receiving government-sponsored behavioral/ pharmacological treatment had one year carbon monoxide-confirmed abstinence [23].

Although, for ethical reasons, we did not employ a‘usual care’ or minimal intervention comparison group, abstinence rates are higher than what would be expected under such conditions. Long-term quit rates among unaided quitters are typically in the range of 5–7% [24–26]. Brief quitting advice from a physician is associated with an estimated point prevalent abstinence rate of 10% compared with 8% when no advice to quit is provided [8].

Withdrawal symptoms predicted failure to achieve long-term abstinence, regardless of treatment group, indicating that residual withdrawal during NRT treatment is a barrier to abstinence. This is consistent with evidence that NRT increases abstinence both by alleviating withdrawal and restoring the rewarding effects of smoking [27–30]. It is possible that Syrian smokers, who are highly dependent smokers, require more intensive NRT. Patients received six weeks of patch and it seems unlikely that extending the number of weeks of treatment after quitting would produce better outcomes, as duration of NRT is unrelated to cessation [8,31]. More promising approaches may be either to increase the dose and route of administration by combining NRT products (e.g. patch plus gum) [28,32,33] or to begin NRT prior to cessation [34,35]. Both approaches have been shown to increase long-term abstinence compared with the standard recommended dose and length of patch treatment, as was used in this study.

The lack of a treatment effect is inconsistent with a large literature, derived mainly from efficacy trials, showing that patch use doubles the odds of long-term cessation [8,31]. We can rule out several potential explanations for this lack of effect. First, differential attrition could bias outcomes if dropout occurred for disparate reasons in the two treatment groups. However, retention was uniformly high and did not differ by treatment group. Second, adherence to patch use was high in both groups, although it dropped off somewhat in the placebo group later in treatment, which may reflect patient un-blinding (discussed below). Third, nicotine patch may not have produced the expected pharmacological effect, for example if the dose or length of use was inadequate. These possibilities do not seem plausible, however, because patients were provided with a six-week supply of patch, which has been shown to be a sufficient duration to aid cessation [8,31], adherence in the nicotine patch group was excellent throughout treatment, and expected reductions in urges to smoke and other withdrawal symptoms occurred for the nicotine patch, but not the placebo patch. Fourth, similar to what has been observed in many NRT trials [36], patients assigned nicotine were more likely to believe they received nicotine than patients assigned placebo. This differential un-blinding occurs because nicotine is a psychoactive drug and can be discriminated from placebo [37], and nicotine replacement reliably reduces withdrawal symptoms and craving [38], which smokers anticipate from previous quit attempts. Patient un-blinding, however, was only partial, with an average of 40% of patients assigned to the nicotine patch incorrectly guessing their assignment. Further, belief in patch assignment did not independently predict outcome. Thus, this partial un-blinding seems unlikely to account substantially for the lack of treatment effect. Lastly, owing to the high level of dependence in our population, the study was powered to detect a larger than average effect (25% versus 10% for NRT versus placebo, respectively, versus 23% versus 14% from meta-analysis [8]). However, our observed effect was so small that lack of power is not a plausible explanation for the null finding.

Because most evidence for NRT has come from efficacy trials, its usefulness in ‘real world’ settings has been questioned. For example, published studies demonstrate greater efficacy of NRT in pharmaceutical industry-supported trials than non-industry trials [39]. In addition, there is conflicting evidence as to whether quit rates with NRT are as high when purchased over-the-counter compared with when prescribed by health-care providers or delivered in clinical trials [40–45]. Many of these findings have been based on observational studies and likely suffer from selection bias [42]. Few randomized effectiveness trials have been conducted in which NRT is evaluated in settings and with populations in which NRT use is intended, and the current study is the first one to be conducted in a low-income country [46]. Our results do not support the incremental value of providing NRT in addition to behavioral counseling. Certainly, these results need confirmation from other randomized effectiveness trials, particularly as in many low- and middle-income countries, including Syria, NRT is costly and not widely available [5].

Our results support the feasibility of implementing primary care-based smoking cessation treatment in a low-income country, where considerable work remains to be done to make effective cessation treatments available to all smokers [1,46,47]. Clinics were very receptive to implementing the program, and participation by physicians and patients was high. Although the level of intervention (three visits, five telephone calls) would likely be prohibitive in many US primary care settings, this was not a barrier to implementation in Syria.

Limitations should be noted. A minimal intervention comparison group might have allowed us to more definitely assess the effectiveness of the behavioral intervention, including its optimal ‘dose’. This trial was conducted under more ‘real world’ conditions than any previous trial in a low- or middle-income country setting— including enrollment of patients with minimal exclusion criteria, delivery of the intervention by primary care physicians, and using a delivery format and intensity deemed feasible for this practice setting, and the provision of free NRT, which is likely to maximize use and effectiveness in this low-income population [21,48]—but patients, nonetheless, may differ from willing-to-quit smokers who chose not to participate.

Despite these limitations, the study makes a novel contribution by demonstrating that a comprehensive, evidence-based smoking cessation program can be implemented successfully in a low-income, Arab primary care setting that reaches large numbers of smokers. Smoking pharmacotherapy is expensive and often not widely available in low-income countries such as Syria. The lack of effectiveness of nicotine patch, despite excellent adherence, questions its utility to improve long-term abstinence in such settings beyond what can be accomplished through behavioral counseling. Additional effectiveness trials are needed to study this issue further.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by PHS grant 1R01DA024876 (W. Maziak, PI). We wish to thank Dr Fouad M. Fouad, the physicians and staff of the participating primary care clinics, and the dedicated physicians who served as cessation coordinators at the clinics: Rabi Yacoub MD, Ghamez Moukeh MD, Nader Akl Kassis MD, Talal As’ad MD and Hasan Fattah MD.

Footnotes

Clinical trial registration

Declarations of interest

None.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the on-line version of this article.

Appendix S1 Transdermal nicotine therapy as an adjunct to behavioral smoking cessation counseling in Syrian primary care settings.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2009: Implementing Smoke-Free Environments. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Rastam S, Asfar T, Mzayek F, Fouad MF et al. The tobacco epidemic in Syria. Tob Control 2006; 15: i24–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maziak W. Smoking in Syria: profile of a developing Arab country. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2002; 6: 183–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asfar T, Vander Weg MW, Maziak W, Hammal F, Eissenberg T, Ward KD Outcomes and adherence in Syria’s first smoking cessation trial. Am J Health Behav 2008; 32: 146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maziak W, Eissenberg T, Klesges RC, Keil U, Ward KD Adapting smoking cessation interventions for developing countries: a model for the Middle East. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004; 8: 403–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asfar T, Al-Ali R, Ward KD, Vander Weg MW, Maziak W Are primary health care providers prepared to implement an anti-smoking program in Syria?, Patient Educ Couns 2011; 85: 201–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Klesges RC, Keil U The Syrian Center for Tobacco Studies: a model of international partnership for the creation of sustainable research capacity in developing countries. Promot Educ 2004; 11: 93–7. 116, 134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kottke TE, Battista RN, Defriese GH, Brekke ML Attributes of successful smoking cessation interventions in medical practice. A meta-analysis of 39 controlled trials. JAMA 1988; 259: 2883–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrams DB, Niaura R, Brown RA, Emmons KM, Goldstein MG, Monti PM The Tobacco Dependence Treatment Handbook: A Guide to Best Practices. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res 2003; 5: 13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.West R, Hajek P, Stead L, Stapleton J Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction 2005; 100: 299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biener L, Abrams DB. The Contemplation Ladder: validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychol 1991; 10: 360–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velicer WF, Diclemente CC, Rossi JS, Prochaska JO Relapse situations and self-efficacy: an integrative model. Addict Behav 1990; 15: 271–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO The fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict 1991; 86: 1119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess 1988; 52: 30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess 1990; 55: 610–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radloff LD. The CES-D: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977; 1: 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas JL, Jones GN, Scarinci IC, Mehan DJ, Brantley PJ. The utility of the CES-D as a depression screening measure among low-income women attending primary care clinics. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression. Int J Psychiatry Med 2001; 31: 25–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes JR, Hatsukami D. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43: 289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes JR, Wadland WC, Fenwick JW, Lewis J, Bickel WK Effect of cost on the self-administration and efficacy of nicotine gum: a preliminary study. Prev Med 1991; 20: 486–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughes J, Hatsukami DK Errors in using tobacco withdrawal scale. Tob Control 1998; 7: 92–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferguson J, Bauld L, Chesterman J, Judge K. The English smoking treatment services: one-year outcomes. Addiction 2005; 100: 59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baillie AJ, Mattick RP, Hall W. Quitting smoking: estimation by meta-analysis of the rate of unaided smoking cessation. Aust J Public Health 1995; 19: 129–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward KD, Klesges RC, Zbikowski SM, Bliss RE, Garvey AJ Gender differences in the outcome of an unaided smoking cessation attempt. Addict Behav 1997; 22: 521–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 2004; 99: 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dale LC, Hurt RD, Offord KP, Lawson GM, Croghan IT, Schroeder DR. High-dose nicotine patch therapy. Percentage of replacement and smoking cessation. JAMA 1995; 274: 1353–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fagerstrom KO, Schneider NG, Lunell E. Effectiveness of nicotine patch and nicotine gum as individual versus combined treatments for tobacco withdrawal symptoms. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993; 111: 271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levin ED, Westman EC, Stein RM, Carnahan E, Sanchez M, Herman S et al. Nicotine skin patch treatment increases abstinence, decreases withdrawal symptoms, and attenuates rewarding effects of smoking. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1994; 14: 41–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rose JE, Behm FM Extinguishing the rewarding value of smoke cues: pharmacological and behavioral treatments. Nicotine Tob Res 2004; 6: 523–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, Mant D, Lancaster T. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; 1: CD000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider NG, Cortner C, Gould JL, Koury MA, Olmstead RE. Comparison of craving and withdrawal among four combination nicotine treatments. Hum Psychopharmacol 2008; 23: 513–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith SS, Mccarthy DE, Japuntich SJ, Christiansen B, Piper ME, Jorenby DE et al. Comparative effectiveness of 5 smoking cessation pharmacotherapies in primary care clinics. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169: 2148–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rose JE, Herskovic JE, Behm FM, Westman EC Precessation treatment with nicotine patch significantly increases abstinence rates relative to conventional treatment. Nicotine Tob Res 2009; 11: 1067–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiffman S, Ferguson SG Nicotine patch therapy prior to quitting smoking: a meta-analysis. Addiction 2008; 103: 557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mooney M, White T, Hatsukami D. The blind spot in the nicotine replacement therapy literature: assessment of the double-blind in clinical trials. Addict Behav 2004; 29: 673–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perkins KA, D’amico D, Sanders M, Grobe JE, Wilson A, Stiller RL Influence of training dose on nicotine discrimination in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996; 126: 132–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hughes JR, Hatsukami DK, Pickens RW, Krahn D, Malin S, Luknic A Effect of nicotine on the tobacco withdrawal syndrome. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1984; 83: 82–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Etter JF, Burri M, Stapleton J The impact of pharmaceutical company funding on results of randomized trials of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Addiction 2007; 102: 815–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alpert HR, Connolly GN, Biener L. A prospective cohort study challenging the effectiveness of population-based medical intervention for smoking cessation. Tob Control 2012. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hughes JR, Shiffman S, Callas P, Zhang J. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of over-the-counter nicotine replacement. Tob Control 2003; 12: 21–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hughes JR, Peters EN, Naud S. Effectiveness of over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapy: a qualitative review of nonrandomized trials. Nicotine Tob Res 2011; 13: 512–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walsh RA Over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapy: a methodological review of the evidence supporting its effectiveness. Drug Alcohol Rev 2008; 27: 529–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hyland A, Rezaishiraz H, Giovino G, Bauer JE, Michael Cummings K Over-the-counter availability of nicotine replacement therapy and smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res 2005; 7: 547–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.West R, Zhou X. Is nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation effective in the ‘real world’? Findings from a prospective multinational cohort study. Thorax 2007; 62: 998–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kishore SP, Bitton A, Cravioto A, Yach D Enabling access to new WHO essential medicines: the case for nicotine replacement therapies. Global Health 2010; 6: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raw M, Regan S, Rigotti NA, Mcneill A. A survey of tobacco dependence treatment guidelines in 31 countries. Addiction 2009; 104: 1243–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alberg AJ, Stashefsky Margalit R, Burke A, Rasch KA, Stewart N, Kline JA. et al. The influence of offering free transdermal nicotine patches on quit rates in a local health department’s smoking cessation program. Addict Behav 2004; 29: 1763–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.