Abstract

Introduction

Developing and adapting health service models to effectively meet the needs of rural and remote communities is an international priority given inequities in health outcomes compared with metropolitan counterparts. This integrative review aims to inform rural and remote health service delivery systems by drawing on the WHO Framework building blocks to identify lessons learned from the literature describing experiences of rural and remote community health service planning and implementation; and inform recommendations to strengthen often disadvantaged rural and remote health systems for policy makers, health service managers, and those implementing international healthcare initiatives within these contexts.

Methods

The integrative review examined the literature reporting rural and remote community health service delivery published from 2007 to 2017 (the decade following the release of the WHO Framework). Using an analytic frame, a structured template was developed to extract data and categorized against the WHO building blocks, followed by a synthesis of the key findings.

Results

This integrative review identified that WHO Framework building blocks such as “Service Delivery” and “Health Workforce” are commonly reflected in rural and remote community health service delivery literature in the decade since the Framework's release. However, others such as “Sustainable Funding and Social Protection” are less commonly reported in the literature despite these elements being identified by the WHO as being integral to successful, sustainable health service delivery systems.

Conclusions

We found that collaboration across the health system governance continuum from local to policy level is an essential enabler for rural and remote health service delivery. Community‐based participatory action research provides an opportunity to learn from one another, build capacity, optimize service model suitability, and promotes cultural safety by demonstrating respect and inclusivity in decision‐making. Policy makers and funders need to acknowledge the time and resources required to build trust and community coalitions to inform effective planning and implementation.

Keywords: community health, health planning, integrative review, remote health, rural health, service models

1. INTRODUCTION

Differences between the health outcomes of people living in rural and remote areas as compared with their metropolitan counterparts have been identified as a world‐wide phenomenon. 1 , 2 Inequities in the health outcomes of people living in rural areas have highlighted the need for strategies to improve access to health services and health professionals outside of metropolitan areas. The United Nations International Labour Organization reported that “while 56% of the global rural population lacks health coverage, only 22% of the urban population is not covered,” further compounded by rural health workforce shortages resulting in a lack of access to urgently needed care for half the global rural population. 3 (pxiii) The deficits observed in access and health spending in rural areas have been identified as resulting in avoidable suffering with an example being “rural maternal mortality rates that are 2.5 times higher than urban rates.” 3 (pxiii)

The issue of access to healthcare within rural and regional settings is a complex challenge. The specific geography, transport availability, and the distance to various (or any) services can all create significant obstacles to timely appropriate diagnosis, treatment, and management of health conditions. 4 In addition, there is often stigma associated with help‐seeking, as well as privacy concerns in small communities. 2

The need to develop service models that effectively meet the healthcare needs of rural and remote communities in order to address the inequities currently experienced by populations outside large metropolitan centers has been identified as a key priority in both national and international healthcare systems. 5 , 6 An international call to action to address the health outcomes gap for those living in disadvantaged regions, including populations in rural areas, has been promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO), highlighting the need to: adapt effective interventions for rural contexts 7 ; scale‐up interventions from urban centers for “…rapid roll‐out in less‐resourced rural settings” 6 (p18); and implement strategies to retain appropriately trained healthcare workers. 8

In 2007, the World Health Organization (WHO) released their Framework for Action titled “Everybody's business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes.” 7 The framework acknowledged that despite sophisticated developments in interventions and technology, health outcomes gaps remained due to inadequacies in “…health systems to deliver them to those in greatest need, in a comprehensive way, and on an adequate scale.” 7 (piii) The primary purpose of the Framework is to “…promote common understanding of what a health system is and what constitutes health systems strengthening.” 7 (pv)

Central to the Framework are six building blocks of a health system: (a) service delivery; (b) health workforce; (c) information; (d) medical products, vaccines, and technologies; (e) financing; and (f) leadership and governance. In the decade since the release of the Framework, research has identified that “the WHO health system framework is instrumental in strengthening the overall health system and as a catalyst for achieving global health targets such as the Sustainable Development Goals.” 9 (p2)

The purpose of this integrative review is to identify evidence of the WHO health system building blocks in rural and remote health service literature. The review also sought to identify the published reports of challenges and barriers that need to be overcome to strengthen rural community health systems and improve the health outcomes of rural communities to address health inequities experienced by rural and remote populations.

2. METHOD

The integrative review method was utilized to enable the inclusion of data from theoretical and empirical literature, providing a variety of perspectives to inform a thorough understanding of phenomena. This method has been identified as a useful approach in healthcare research. 10

The literature search included the CINAHL, Cochrane, PubMed, and Scopus databases. In addition, the reference lists of key articles were reviewed and a hand search of key journals relating to Implementation Science and Rural Health was conducted. The searches focused on rural health service models, adaptation, implementation, and service delivery. The initial literature search parameters included articles published between 2002 and 2017, for which full‐text English versions were available. Key search terms included “rural health service,” “model,” “context,” “adaptation,” “implementation,” and “service delivery.”

The terms rural or rurality can be considered in relation to geographical, locational, and sociocultural domains. 11 Definitions of rural or remote are not homogenous and differ between countries and regions; however, the majority of rural communities experience similar challenges in terms of “… access to care, resource allocation, health inequalities and deprivation.” 12 (p4) For the purposes of this literature review, articles in which the context has been identified by authors as “rural” and/or “remote” have been included to draw upon learnings from a range of relevant studies.

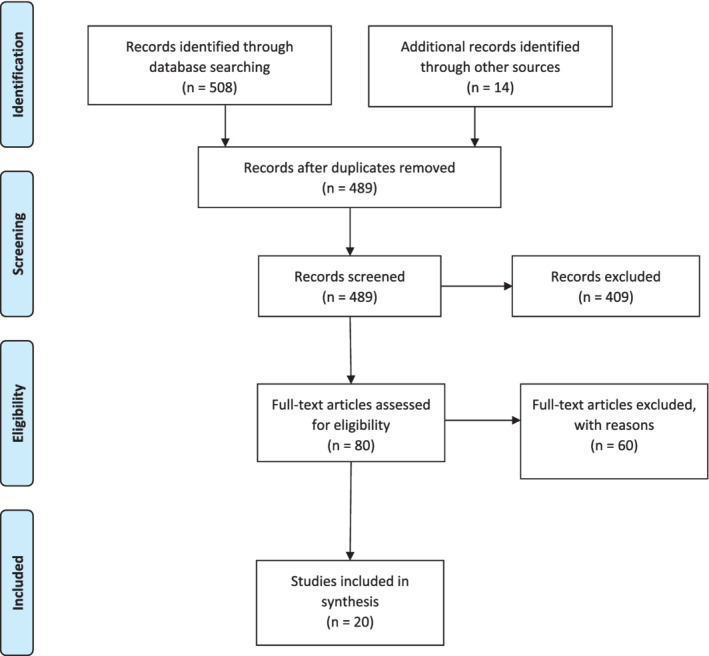

The PRISMA framework (Figure 1) provides a summary of the search and screening process. The initial search yielded 508 articles. This yield was reduced through the removal of duplicates and the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria that reduced the number of articles under consideration to 80. Empirical articles were retained for thorough analysis, which met the inclusion criteria: (a) focus on service intervention and provision within rural and/or remote health context; (b) adaptation of interventions and service model design for rural and/or remote primary and/or community health practice; (c) written in English language and published between 2002 and 2017; and (d) peer reviewed.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA framework of search process

Articles were excluded if their focus was: (a) purely workforce issues and health student training; (b) a description of population data analysis of specific locations; (c) a description of population health beliefs and attitudes specific to particular locations; (d) funding and health insurance in isolation from implementation issues; (e) a description of health promotion awareness raising programs rather than service provision models; (f) screening and diagnostics, acute care settings, and targeted programs without reference to the rural context.

To achieve the aim of reviewing strategies that inform policy and planning to strengthen rural community health services capacity to address health inequities, the inclusion criteria were further refined to focus on the decade (2007‐2017) since the release of the WHO Framework for Action: Everybody's Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes. 7 This resulted in 20 articles being retained, which were reviewed in full text and compared to the Building Blocks articulated in the WHO Framework (see Figure 1 for PRISMA Flowchart).

Of the 80 initial full‐text articles, 10% were reviewed by three of the authors independently (a combination of D.A.S., J.T., C.F., and D.D.) to check the reliability of the application of the criteria for inclusion and exclusion. A structured template was developed to support the extraction of relevant information (author/year/title, country, sample/setting, study purpose, design, and findings) and evidence of examples or difficulties relating to the six WHO Framework building blocks. Template analysis (King, 2012) was undertaken, involving sorting and categorizing from the structured template spreadsheet into tables (see Tables 1 and 2), followed by further summarizing of the data to facilitate synthesis of key concepts and learnings. 13

TABLE 1.

Results of articles identified by WHO building block

| Building block | Articles providing exemplars | Articles describing challenges or barriers |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Service Delivery | 20 | 11 |

| 2. Health Workforce | 13 | 8 |

| 3. Information | 2 | 2 |

| 4. Medical Products, Vaccines, and Technologies | 4 | 2 |

| 5. Sustainable Funding and Social Protection | 2 | 8 |

| 6. Leadership and Governance | 8 | 4 |

TABLE 2.

Table of evidence—Summary of key findings for rural health service delivery by article in relation to WHO building blocks

| Authors | Design | Purpose | Setting | WHO building blocks exemplars | WHO building blocks challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aljasir &Alghamdi 13 | Mixed methods | Assess consumer satisfaction with mobile clinics in Al‐Laith region of Saudi Arabia | Saudi Arabia: 13 villages serviced by mobile service in remote rural areas covering 12 administrative emirates. | BB1: Mobile service model to improve equity and reach to those in high need. | BB1: Differences noted in different localities and geographical challenges. Need to provide more screening and prevention services and tailor to the needs of each community. |

| Chilenski et al 14 | Mixed methods: longitudinal and randomized block design | Examine the impact of the PROSPER delivery system for evidence‐based prevention programs on multiple indicators of social capital in a rural and semirural community sample. | USA: 3137 individuals in 28 communities throughout Pennsylvania and Iowa, USA. | BB1: Results suggest community collaborative initiatives can build social capital. | BB1: Future research needs to explore social capital outcomes in collaborative community health initiatives |

| BB6: Governance led by health administrators of stakeholder groups enabling a community coalition of health, education, businesses, and other community stakeholders | |||||

| Cornwell et al 15 | Mixed Methods Program Implementation Evaluation | Evaluate adaptation and implementation of a coordinated school health program in a rural district. | USA (Rural county) | BB1: Broad professional and community stakeholder engagement from outset inclusive of program selection. | BB5: Unclear if funding was ongoing. |

| BB2: Staff education to understand unique local health needs and assets. | |||||

| BB3: Data used to inform priority goal settings | |||||

| BB5: Sourcing of external grants | |||||

| BB6: Governance teams composed of local community stakeholders established for decision making. | |||||

| Dooley et al 16 | Mixed Methods: Program description and evaluation | To describe and evaluate an obstetric care program delivered to 28 remote Aboriginal communities service by rural‐based health care. | Canada (28 remote communities; 350 rural primarily Aboriginal Sioux women) | BB1: Collaborative service planning enabled creative solutions to improve access, and model of care that incorporated Aboriginal values and culturally sensitive care | BB2: Incentives are required to attract the next generation of clinicians |

| BB2: A team approach with broad scope and multi‐skilled clinicians | BB5: Funding was needed for a range of service provision requirements including transport for transfer of care, mentoring, and training to enable sustainability. | ||||

| BB4: Telehealth consultations effectively reduced travel for obstetric assessments and access to clinician support from larger centers | |||||

| BB6: Organizational culture of sustainable programs includes champions | |||||

| Farmer &Nimegeer 17 | Community‐based participatory action research | To explore how community participation can be used in designing rural primary healthcare services by describing a study of Scottish communities. | United Kingdom (Scotland): Four rural Scottish case study communities | BB1: Community‐based participatory action research enabled identification of health priorities and customized, affordable healthcare models to address local community priorities. Standard service models can provide a basis for community participation discussions including adaptations and additions to meet local needs. | BB1: Greater clarity is required in regards to community participation in local service delivery. |

| Fitzpatrick et al 18 | Case study | To understand the dynamics of best practice integrated care for people with (severe and persistent mental illnesses) SPMI living in a small rural community in Australia. | Australia (NSW): A well‐established integrated care service in rural NSW (Mudgee) | BB1: Incremental processes of integration can build on success and trust, paying attention to local contexts and responsive to the needs of patients and stakeholders. There is a strong case for place‐based systems of care Locally driven approaches are designed within local resource capacity, are financially and clinically sustainable and embody the values of local practitioners. | BB1: Improvements are needed at the interface between primary and secondary services. Systems are required that reward collaborative practice to deliver truly integrated care. |

| BB2: Close working relationships with GPs is critical. | BB5: Bulk billing options under threat due to undersupply of GPs and uncertain funding. | ||||

| BB5: The importance of bulk billing to safeguard patient access and efficient operations | BB6: Policy makers need to recognize and support local solutions that meet systemic and community objectives. | ||||

| BB6: Team culture and leadership play an integral role in service sustainability. | |||||

| Gaudet et al 19 | Qualitative study using naturalistic and ethnographic strategies. | To bridge the knowledge gap that exists with respect to rural (Interprofessional Collaboration (IPC), particularly in the context of developing rural palliative care | Canada: Members of rural palliative care teams in four rural communities in north‐western Ontario. | BB1: Interprofessional team included a broad range of providers across government and non‐government service sectors, enabled an increased level of cooperation within their organizations, combining efforts to improve patient care. Informal relationships and networks increased confidence, supported collaborative practice, and improved service provision. | BB2: Decision makers should harness of knowledge of healthcare workers as advocates for patients, their communities, and service system improvements. |

| BB2: The role of healthcare workers as advocates for patients and service system improvements. | |||||

| BB6: Geographical distance from head office empowered satellite service providers. | |||||

| Haggarty et al 20 | Qualitative descriptive study | Synopsis of rural and isolated toolkit for Canadian Collaborative Mental Health Initiative (CCMHI) | Canada | BB1: Broad community stakeholder involvement can enable adaptation and “local solutions” to address priorities for rural and isolated communities. Diverse strategies to communicate healthcare information and transport are integral to rural service provision. | BB1: Research is needed to increase the evidence‐base to enhance planning and overcome challenges. Ethical foundations embracing diversity and inclusion are required for community participation. New models are required to improve integration and collaboration, including links with urban specialists. |

| BB2: Interprofessional teams supported by community advisory committees can work together to address emerging local health issues. | BB2: Core competencies for workers may assist effective support and capacity building. | ||||

| BB5: Funding related challenges were identified. Financial incentives are required to attract health professionals and mandate collaborative care. Longer‐term rather than short‐term funding is required. | |||||

| BB3: Local working groups collecting data to inform service planning. | BB6: A greater focus on government policy development and planning for rural and isolated services. Lack of alignment between federal and provincial jurisdictions limits service delivery. | ||||

| BB4: Telehealth to overcome challenges associated with distance and isolations | |||||

| Morgan et al 21 | Mixed methods | Describe the development, operation and evaluation of an interdisciplinary memory clinic designed to improve access to diagnosis and management of early stage dementia for older persons living in rural and remote areas in Canadian province of Saskatchewan. | Canada (Sparsely populated Canadian province of Saskatchewan) | BB1: Use of combination of telehealth and clinics to increase access, harnessing an inter‐ and trans‐disciplinary approach within the model of care. Early community consultation was critical to success. | BB2: Improvement in physician involvement in (end of day) team teleconferences is needed. |

| BB2: Team members rotate delivery of professional development | |||||

| BB3: Data reporting of travel distance saved through telehealth | |||||

| Ong et al 22 | Mixed methods | To develop template for economic evaluations of health services to quantify the differences in intervention delivery between best practice PHC via Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services and mainstream GPs | Australia: Indigenous communities: staff from 5 different health services including urban Melbourne (7), rural Vic (1) and remote central Australia and NT (8). | BB1: Templates for economic evaluations, including the differences in the way interventions are delivered, can enable appropriate resource allocation for targeted health service models for disadvantaged groups. | BB3: Context‐specific economics data are vital to assessing interventions for disadvantaged groups together with qualitative data to inform decision making. |

| Parker et al 23 | Realistic evaluation | Investigate the factors contributing to effective Interprofessional Practice (IPP) in rural contexts; to examine how IPP happens and to identify barriers and enablers. | Australia (33 participants: managers, policy makers, and representative across rural health care settings) | BB1: IPP enables increase access to comprehensive care for patients. Enablers of collaboration included co‐location and community connections. GPs play pivotal role in coordination | BB1: Workload constraints and “ways of working” constrained true IPP |

| BB2: IPP facilitates learning and support for health professionals. | BB2: Barriers include minimal numbers of some health disciplines and lack of understanding of the roles of others. | ||||

| BB5: Funding models such as Medicare rebates can enable “joined up care” (p. 9) | BB6: Requires a culture of open and critical engagement. Barriers including service fragmentation. | ||||

| BB6: Shared understanding can enable planning of integrated services | |||||

| Pesut et al 24 | Community‐based research using mixed methods approach | Test the feasibility and identify potential outcomes of implementing a rural palliative supportive service (RPaSS) for older adults living with life‐limiting chronic illness and their family caregiver in the community. | Canada (Two co‐located rural communities with populations approximately 10 000 with no specialized palliative services) | BB1: Community‐based advisory committee to draw on local knowledge and expertize of local context for planning; enabling community engagement and capacity building. Nurse coordinators role as a care navigator. Holistic care models utilizing a range of modes of delivery. | BB1: Need to allow time to build an understanding of local context and trust with local community. |

| BB2: Multidisciplinary support team for nursing team. | |||||

| Pidgeon 25 | Qualitative – observational design | Observation of similarities and differences in what occupational therapy “does” and ‘is’ in four different, but similar, very remote contexts. | Australia (Northern Territory), USA, and Canada | BB1: Flexible delivery models are needed to address costs of service provision in remote communities, for example, fly/drive‐in service. Use of coaching frameworks by health professionals can increase families'/community skills and capacity. | BB1: Best practice models should take into account local culture, beliefs, resources, environment, and have flexibility to address unique family/community goals. |

| BB2: Support can enable the extended scope of practice required for remote context. | BB2: Vital to increase health professionals' understanding of cultural safety through respectful communication and empowering clients through inclusive decision making. Access to professional development needed to support required extended scope of practice for remote settings. | ||||

| BB4: Community visits can be supplemented with telehealth | BB4: Telehealth requires reliable on the ground support to facilitate connectivity. | ||||

| Quinn et al 26 | Mixed methods | To investigate the perceptions, acceptability and barriers and enablers to the delivery of non‐medical primary maternity care models in Far West NSW, as an example of remote Australia | Australia (Far West NSW): 14 clinicians and/or policy makers | BB1: Enablers for service models for a remote context included funding and staff incentive programs, local access to professional development, accommodation for patients from remote communities in larger towns, collaboration, and shared vision between staff and community | BB2: Retention of well‐qualified health professionals in remote settings is a key challenge. Workforce shortages are felt more acutely in rural and remote areas, also impacting on capacity for interprofessional collaboration. |

| BB2: Staff exchange programs between metropolitan and remote health services to enable clinicians to maintain clinical competency. | BB5: Lack of funding to enable the delivery of new models of care in remote settings. | ||||

| BB6: Professional registration requirement standards identified as a barrier to new models of care in remote areas. | |||||

| Semansky et al 27 | Mixed methods. | Illuminate potential problem areas for rural agencies under USA national health reform. | USA (Rural health agencies in New Mexico) | BB1: Funding of large scale demonstration pilot of a service model informed national reform. Input from local stakeholders is required as early as possible in the planning stages including implementation logistics. | BB1: Significant modifications were needed to service models; targets and parameters need to be defined early. Transforming models requires tailoring to address additional changes and optimize opportunities. Additional support, sharing of resources and a long‐term commitment is required to “prevent disruptions in care” (p. 851) |

| BB2: Web‐based training and supervision to increase access to support for rural clinicians. | BB2: Recruitment and workforce support of specialist clinicians is required | ||||

| BB4: Telemedicine can improve access to range of services including behavioral health care. | BB3: Clarity of measures and “real‐time” evaluation is required to enable “mid‐course corrections” during implementation (p. 849) | ||||

| BB6: Leadership by state agencies mandating the creation of a “purchasing collaborative” of local stakeholders to maximize access, enhance quality, and improve use of public funds and consumer voice in operational planning (p. 844). | BB4: The use of telehealth has been constrained by technological requirements and insurance reimbursement limitations (p. 847) | ||||

| BB5: A tech based billing system led to unanticipated problems. Insufficient compensation was provided for additional responsibilities and liabilities. Financial system constraints can hamper community input into design. | |||||

| Smith et al 28 | Case Study | To describe, from the analytic standpoint of community control and cultural comfort, the main features of the “Family Model of Care” that underpins service operations and management processes | Australia (Northern Territory): Remote Aboriginal community in Central Australia | BB1: Model of care emphasizing the centrality of the local traditional community worldview and values into service design for mainstream services. Community control and cultural comfort were fundamental to address social determinants of health and increase access. The “Family Model of Care” integrates local social systems, capacity building, and responsiveness without compromising cultural protocols (p. 9) | |

| BB6: Mainstream services can function in a complementary and supportive manner, being accountable to a local management system inclusive of community tradition norms. | |||||

| Smith et al 29 | A descriptive, qualitative analysis of extensive document reviews. | Explore how communities translate evidence‐based and promising health practices to rural contexts | USA: (70 grantees representing rural and frontier areas in 36 states of USA) | BB1: Conceptual models can support effective rapid implementation into community practice. Adaptations of models are required to overcome challenges in specific contexts, including content, models, settings and wrap around components. Locally developed evidence‐based protocols can strengthen systems of care. | BB1: Barriers to translation of evidence‐based practices in rural settings include cultural misalignment, practical limitations, lack of commitment, insufficient capacity. The lack of evidence‐based models developed in rural contexts impacts ability for translation in these settings. Need to prioritize local program evaluation (and skills) to build evidence‐based for rural interventions. |

| BB2: Mentorship in implementation of evidence‐based programs from experts or model communities assisted in overcoming implementation challenges. | BB5: Short‐term time‐limited funding cycles for evidence‐based or promising models does not enable sustainability either locally nor the ability to generate evidence‐based models specifically for rural settings. | ||||

| Sullivan et al 30 | Action Research using mixed methods | To describe the action research approach taken to engage a multidisciplinary group of health professionals and managers from giver rural health services with government officers in redesigning their emergency care services and informing legislative change | Australia (Victoria): Multidisciplinary health professionals and managers from 5 rural health services with government officers | BB1: Collaborative practice model of multiple rural health services promoted by state government to test alternate model of service delivery. | |

| BB6: Action research shifted focus from technical to emancipatory approach, providing a safe approach to service system and legislative change (p. 12). | |||||

| Taylor et al 31 | Qualitative Evaluation using Participatory Action Research ‐ Realist Evaluation Approach | Evaluation of a consumer‐driven rural mental health service (The Station Community Mental Health Centre): describe, analyze, and promote the service governance model at The Station and determine how the model works and for whom and its sustainability. | Australia (South Australia): Mental health service in rural South Australia | BB1: Active support of local health system and stakeholders shown to be important for service legitimacy and confidence (p. 5). Contextual factors can support program mechanisms, for example, governance arrangements, support at local and state level, key stakeholders, and links to peak organization to provide conduit between government and the service (p. 6). | |

| Vanderpool et al 32 | Qualitative – Case Studies | To examine the collective experience of 13 West Virginia community organizations implementing evidence‐based cancer control interventions | USA (13 West Virginia community health organizations) | BB1: Adaptations required for successful implementation included modification of delivery methods, adjusting program timelines to suit funding period, creation of new or tailoring of materials for local context, adding activities or combining multiple programs, and evaluation design revisions. Intervention selection considered a range of factors including organizational capacity, target group socioeconomic demographics, literacy levels, and intervention complexity. | BB1: Further investigation is needed into the abilities of communities to identify core components of interventions to maintain programmatic fidelity while adapting for the context to avoid mismatch. Few evidence‐based interventions have originated in rural communities. Efficacious programs must be flexible to enable transportability to other settings. Researchers need to better understand the contextual realities. More focus is required on “how to select, adapt, implement and sustain evidence‐based interventions while maintaining scientific fidelity” (p. 11). |

| BB2: Training to specifically prepare for implementation was provided. | BB2: Standardized training needs to be relevant to the context. More “train‐the‐trainer” is required for sustainability. | ||||

| BB5: Linking funding to specific programs or interventions can deter providers. Service wants more time, flexibility, resources, and training to implement contextually appropriate interventions for their rural community. |

Abbreviation: BB, building block.

3. RESULTS

A total of 20 peer‐reviewed articles that met the selection criteria were included in this review. The review identified examples of rural health services in which the WHO Framework Building Blocks are reflected in delivery models and implementation. These examples serve as exemplars, providing rural health policy makers and planners with learnings to further strengthen local health systems. We also noted gaps where some WHO Building Blocks were not identified within rural health service research and authors' reports of challenges and barriers to the implementation of certain subsets of the Building Blocks.

Of the articles reviewed, 10 used a qualitative research design and 10 used a mixed methods design. The articles provided a cross section of settings including eight from Australia, five from United States, five from Canada, and one each from the United Kingdom and Saudi Arabia. Of these, the settings for four papers were Indigenous communities—two in Canada and two in Australia. The articles focused predominately on rural settings that were reflected in 11 articles with a further four focusing on remote health settings and five on a combination of rural and remote, with rural and/or remote being as defined by the authors.

Certain Building Blocks from the WHO Framework were identified as more highly represented in the literature in the decade following the Framework's release than were others. Commentary regarding challenges or barriers relevant to the implementation of particular Building Blocks was also identified. Table 1 provides an overview of the number of articles that reported content regarding each of the Building Blocks. Table 2 (Table of Evidence) provides a summary of the key review findings for each article.

4. BUILDING BLOCK 1: SERVICE DELIVERY

The 20 articles reviewed included examples of the WHO Building Block 1: Service Delivery. This block includes six priorities: integrated service delivery models and packages; consumer engagement influencing demand for care; infrastructure and logistics; patient safety and quality of care; and leadership and management. Innovative service models identified in the rural health literature reviewed included examples of mobile services, 13 fly/drive‐in models, 25 and telemedicine. 16 , 20 , 21 , 25 , 27

Community collaborative engagement was identified in the literature as key to successful service model or program implementation. Authors reported the role of stakeholders as being vital to contextualization for a rural setting. This involvement ranged from early engagement to inform program selection and design, 15 , 21 , 27 input into solutions to improve access and ensure culturally sensitive care 16 , 29 to more formalized relationships such as community‐based governance committees. 24 Community stakeholder engagement and facilitation was reported as either being undertaken by project managers, 21 , 28 the key local agency fund‐holder 14 or in some instances was legislatively mandated as a condition of receiving government funding. 27 In rural settings, community advisory committees or similar entities to facilitate community engagement and guide health service planning and implementation can encompass a broad cross section of community actors including but not limited to “primary care, community agencies, faith groups, agricultural, Aboriginal, law enforcement, pharmacists, key employers” 20 (p8) in addition to representatives from other government agencies.

Community‐based participatory action research was reported as being an effective approach to the identification and customization of models and ensuring adaptations address local community needs 17 and service evaluation. 31 An example is participatory action research undertaken in Scotland to design primary healthcare services for local communities. The research was undertaken as a partnership between local health authorities and university‐based researchers who engaged community members through nominations by local organizations or self‐nominations following community advertising of the opportunity to participate. 17 Additional benefits of stakeholder engagement were noted in terms of building of social capital, 14 capacity building, 29 shared vision and local ownership, 26 promotion of trust and service legitimacy, 31 communication of healthcare information, and identifying innovative local solutions to implementation challenges. 20 , 28

The Service Delivery Building Block elements of integration and trust were reported in a number of articles, with Fitzpatrick and colleagues emphasizing the case for place‐based systems of care (2017). 18 Sullivan et al 30 reported a collaborative practice model consisting of multiple rural health services supported by a state government. Smith and colleagues described collaboration between mainstream services and the traditional Indigenous owners of the land enabling community health services to be delivered by ensuring that local culture was central to the service model design, seeking consistency with the worldview of the local Indigenous community. 28 Interprofessional practice was seen as integral in rural health, from implementation planning processes through both formal networks and informal relationships, 19 , 21 to service delivery collaboration and increasing access to comprehensive care to address diverse health needs of the community. 23

Rural service delivery exemplars commonly reported a systematic approach to planning, implementation, adaptation, and evaluation. This included an emphasis on taking the time to understand the health priorities and local contextual factors to be considered when choosing or customizing interventions. 17 , 18 Smith and colleagues described a conceptual model utilized to inform effective rapid implementation while retaining the flexibility to incorporate locally developed protocols to strengthen the systems of care. 29 Evaluation was identified as being vital, both in terms of enabling early intervention modifications to suit the context 27 and contributing to the body of rural health service evidence including economic evaluations to ensure appropriate resource allocation for disadvantaged populations. 22

A total of 11 articles noted challenges to the implementation of Service Delivery including improvements needed at the interface between services in order to effectively deliver integrated care, 18 and constraints on both macro and micro levels that impede collaboration and interprofessional practice. 23 Examples of such constraints include funding models and service fragmentation at a macro level in addition to lack of diversity in the health disciplines represented in the workforce at a local level and workload constraints at the micro level. The time constraints placed on those implementing funded initiatives were identified as a barrier to truly understanding the local context and building community trust. 24 Without such time, best practice models cannot be effectively implemented as this impacts the ability to fully explore and understand local environments, culture, beliefs, resources, and the local communities' health priorities. 13 , 25 Flexibility was noted as a key requirement in order to effectively implement service models and initiatives to address unique contextual factors and community needs. 25 , 27 , 32 In order to tailor models to address local community needs, long‐term commitment is needed with the sharing of resources between organizations providing an opportunity to optimize capacity. 27

Evidence‐based models developed and evaluated in rural settings are necessary to build the evidence‐base to inform implementation. 28 , 32 Increasing the evidence‐base will enhance planning and inform strategies to overcome challenges 20 , 32 while providing guidance and support to avoid misalignment of interventions that can become a mixture of different interventions and lack evidence of efficacy. 28

5. BUILDING BLOCK 2: HEALTH WORKFORCE

A total of 13 articles contained examples of the Building Block of Health Workforce to improve health service systems. This building block includes priorities relating to the recruitment of appropriately qualified health professionals with the skill sets required for the context, and the retention, professional development, and clinical support of staff. The literature included references to a broad range of health care providers working in rural settings including nurses, physicians, midwives, social workers, occupational therapists, pharmacists, psychologists, social workers, and Indigenous Health Workers.

Recruitment and retention for the rural and remote context are required in order to secure multi‐skilled health practitioners able to work across a broad scope of practice. 16 Local health professionals representing a range of disciplines and skill‐sets enables an inter‐professional team approach, 16 , 20 which in turn is required to address the diverse range of local health needs of rural and remote communities and maximize finite financial and workforce resources.

Interprofessional teams enable the sharing of knowledge and expertise and contribute to the professional development and clinical support of other rural healthcare team members. 21 , 23 , 24 Such support, both within the local community, through telehealth education, 27 or through clinician exchange programs with metropolitan centers, 26 enables clinicians to not only maintain clinical competency but also to work in the extended scope of practice often required within a remote context. 25

Education extended to more than clinical training, with education on the local health context—a unique element in the successful health service delivery in rural and remote settings. 15 Training and mentorship from health professionals in other communities and from experts help to overcome implementation challenges when establishing new services or programs. 28 , 32

Health workforce strategies in exemplar initiatives included working collaboratively across the health workforce and organizational boundaries, in order to provide effective integrated care in rural and remote settings. 19 Successful service systems highlighted the role of healthcare workers, including General Practitioners 19 and Nurse Coordinators, as both care coordinators and as advocates for their communities, including providing input to service system improvements. 19 , 20

Of the articles reviewed, eight identified key workforce challenges and provided recommendations to overcome these and other identified gaps. Authors proposed the need for strategies to address challenges to recruitment and retention of appropriately trained staff, 27 including incentive schemes. 16 Given the multifaceted nature of healthcare delivery in rural and remote communities, the development of core competencies for rural workers was recommended. 20 Some programs reported the negative impact of lack of health professionals from particular disciplines and lack of understanding of interprofessional roles on the opportunities for interprofessional practice. 23 , 26

Authors noted that healthcare workers should be acknowledged as holders of knowledge of local community needs and that decision makers should harness this knowledge to inform service system improvements. 19 Strategies to increase access to professional development, connection, and clinical support for isolated health care workers were identified. Challenges to engaging some health care providers in telehealth on a regular basis were identified, particularly due to competing demands. 21 Support and education were identified as being vital to health care workers with an extended scope of practice and building capacity to deliver culturally safe health care by being informed as to the values of the individual and community; communication, which is respectful of the belief systems of the clients; working collaboratively with “cultural translators” such as Indigenous Health Workers or family members; and ensuring inclusive treatment decision‐making. 25 Those implementing evidence‐based programs were warned that a standardized approach to training may not be relevant to rural and remote contexts and that train‐the‐trainer packages were recommended for the sustainability of such initiatives. 32

6. BUILDING BLOCKS 3 AND 4: “INFORMATION” AND “MEDICAL PRODUCTS, VACCINES, AND TECHNOLOGIES”

Only two articles were identified with explicit mention of Building Block 3: Information, while four articles discussed Building Block 4: Medical Products, Vaccines, and Technologies, with the references to Building Block 4, all relating to telehealth/telemedicine. Exemplar programs identified the importance of obtaining all relevant data to inform planning and priority setting, 15 with specific data being collected in some instances to demonstrate the impact of new interventions such as the travel distance saved through telehealth. 21

Only two articles discussed specific challenges or requirements in relation to “Information” while a further two authors identified particular challenges in relation to technology. Despite calls for data‐informed service planning decisions and robust evaluation design, there was little mention of data and information sources identified in the literature reviewed. This is somewhat surprising given the need to contribute to the body of rural health service evidence. 20 Ong et al 22 discussed the challenges in accessing contextually specific economics data to inform healthcare planning, particularly in relation to disadvantaged populations. The literature contained warnings that those planning healthcare implementation need to be clear on the data and measures from the outset, recommending that given the myriad of contextual factors that may or may not be foreseen, formative evaluations were needed to make changes progressively in real time. 27

Telehealth was identified by a number of authors as the predominant technological advance with the potential to improve access to services, overcome the barriers of geography, and isolation, and improve rural and remote health outcomes. 16 , 20 , 27 Telehealth was not seen as a replacement for local services, but rather as an adjunct, providing additional access between community visits by fly/drive‐in clinicians in remote areas. 25 In addition, telehealth technology was utilized in exemplars to increase clinician access to clinical support, consultation, and education. 16

While telehealth was identified in a number of exemplar service implementations, difficulties were encountered in relation to reliable internet and technological connectivity and a lack of on‐the‐ground support for technical support staff. 25 In addition, the opportunities afforded by telehealth were noted to be constrained in some instances by the narrow parameters of reporting, billing, and health insurance requirements. 27

7. BUILDING BLOCKS 5 AND 6: “SUSTAINABLE FINANCING AND SOCIAL PROTECTION” AND “LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNANCE”

While an emphasis was present throughout much of the literature on the importance of reliable and sustainable funding and resourcing, there was little commentary on how this could be achieved. Of the articles reviewed, two included reporting of examples of financial models to support rural health service delivery and implementation. Finance was discussed in relation to capitalizing on external grants. 15 Financial models such as bulk billing to address the financial barriers to healthcare access 18 and Medicare rebates to enable coordinated care 23 were identified as key strategies for rural and remote communities.

Several articles (eight) reported challenges in relation to sustainable funding and the associated social protection for rural communities. The WHO identified pooling of both financial risk and funding as a means to address some of the challenges experienced in rural and remote settings, 7 however evidence of this was lacking in the papers reviewed for this integrative review. Authors described the problems associated with short‐term funding or lack of clarity as to whether funding would continue for service sustainability. 15 , 16 , 18 , 20 Funding models with constraints and narrow requirements were noted as not being aligned with the realities of rural healthcare provision. 27 , 32 Others discussed the difficulties in relation to funding inadequacies to implement new models given specific challenges within the rural and remote health context, including distance and travel, 16 , 26 and the need for additional funding for recruitment and retention incentive schemes. 20

Of the articles reviewed, eight described leadership and governance models within the rural and remote health service contexts while four papers provided recommendations focusing on leadership and governance of rural health service systems. Exemplars of leadership and governance in rural healthcare systems consistently reported the benefits of local stakeholder involvement in planning and decision‐making. 14 , 15 Collaboration was further seen to be promoted when it was integrated into the model required at a macro level by state agencies who provided funding. 27 Examples of intersectoral and community‐based leadership were provided by Chilenski and colleagues, describing the establishment of local teams to oversee the selection and implementation of evidence‐based school‐based health programs. 14 The team drew on local knowledge and engagement through the inclusion of not only local health agency representatives, but importantly a diverse range of stakeholders including consumers, education sector, and prevention agencies and further extending to “businesses, law enforcement, faith‐based institutions, parent groups, the juvenile justice system and/or the media.” 14 (p127)

An example of such intersectoral collaboration and coalition building in action is the case study of a consumer‐driven mental health service established in South Australia. 31 The service was enabled through partnerships between the local mental health team with additional staffing resources provided by the regional health service and the state government, further supported through local government in‐kind contributions. The governance arrangements included the service becoming an incorporated organization with a management committee heavily weighted to community representation to facilitate the community‐led approach with community members, mental health service consumers, and a mental health professional.

In addition, organizational culture and champions were identified as being key to program implementation and sustainability in rural settings. 16 , 18 Interestingly, Gaudet et al 19 reported an unexpected benefit of the geographical distance between an organization's head office and more remote service providers, which was seen to empower the local providers in their decision‐making for their local community. While some papers identified examples of support for local stakeholder engagement in governance, others identified service fragmentation as presenting barriers to open engagement, 23 with collaborative governance needing to be supported at a macro level by policy makers. 18 The need for government policy development to consider rural and remote contexts to avoid a malalignment between policy and service delivery was emphasized. 20 This was also highlighted in terms of professional registration requirements that can present barriers to new models of care in remote communities. 26

8. DISCUSSION

Evidence of innovation was apparent within rural health delivery exemplars as health services sought to adapt and overcome local contextual challenges. Examples were seen of seeking community engagement to better understand population health needs, local barriers, and opportunities, and input into planning to identify suitable solutions to overcome challenges, with some harnessing Participatory Action Research to enable this. 17 , 31

Leadership and governance were discussed explicitly in the literature, 15 , 18 , 27 and also referred to when describing service delivery models. Consistent with the key functions of this WHO building block, collaboration and coalition building across jurisdictional and sectoral boundaries was identified as a key enabler to effective rural and remote health service delivery. 14 , 31

Such collaboration is required at both the macro level to inform policy 33 and at a service system level between service system interagency and community partners, mirroring the requirement for collaborative interprofessional health care at the direct service delivery level. Restrictive and narrow policy and governance requirements can and do impede the ability of health service managers and clinicians to be responsive to the needs of local communities. Flexibility is required if contextual needs and challenges are to be understood and service delivery models adapted to effectively address these. 31

The WHO building blocks have been utilized by authors of reviews and research reports for varying purposes. These include a framework for the review of health sector reform and strategies to strengthen health systems 34 ; and reviewing the status of health systems in particular countries, with an area of focus being countries of low or middle income. 9 , 35 , 36 This integrative review adds to this body of literature by utilizing the WHO building blocks as a lens through which to review rural and remote health literature, to gain learnings to inform future areas of focus for rural health systems strengthening.

Differing opinions exist regarding the utility of the WHO building blocks for evaluation, acknowledging that the framework was not originally developed for this purpose but rather to guide resource investment to strengthen health systems. 37 Authors have reported the effectiveness of using the building blocks to inform a framework for research, 9 , 35 while others have proposed using a formative approach, enabling the adaptation of the building blocks framework to the research context. 37

A critique of the WHO building blocks framework by Sacks and colleagues suggested expanding the framework to include an explicit focus on community health, noting that without such attention, the focus of policy makers and therefore funding often centers on facility‐ and specialist‐based health services. 38 While the WHO framework identifies the vital nature of “civil society organizations in service delivery planning and oversight” 7 (p16) and for the building of coalitions and intersectoral collaboration, the authors propose the expanded framework includes specific attention to societal partnerships and community organizations in order to effectively address the social determinants of health and acknowledge the role of household production of health. Research into unlocking community capabilities has emphasized the extent to which a thorough understanding of local community context and the development of effective collaborations is intimately connected to the building of trust with communities, particularly when this has been compromised by previous experiences. 39

A limitation of this review is that it does not explore the interrelationship between the building blocks, but rather reports on the presence of each as an individual element. Mounier‐Jack et al 37 discussed the value of the WHO framework in providing a shared language for researchers and service planners, while warning that “… it is not suitable for analysing dynamic, complex and inter‐linked systems impacts.” There is much to be learned through seeking to understand the relationships and interactions between building blocks, noting that challenges in certain building blocks will impact other functions. 34 , 36 In addition, a lack of weighting of the building blocks may be of concern, presenting each as being of equal importance although this may differ between contexts. 37

9. CONCLUSION: FUTURE IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE AND RESEARCH

While there is international acknowledgment of the need to address the inequities in health outcomes between populations living in rural and remote communities and their metropolitan counterparts, further commitment and action are required in regards to sustainable funding models and the “rural proofing” of policy and service models. 12 Policy makers and funding bodies need to acknowledge the time, resources, and funding required to build trust and local coalitions, providing the scope to engage community and local stakeholders in planning, implementation, and evaluation in order to identify and, where needed, effectively adapt service models and interventions for rural and remote contexts, which are by very nature not homogenous but rather present unique challenges and opportunities. 13 , 18 , 24 , 38 , 39

Collaboration is an essential enabler for rural and remote community health service delivery. 14 , 16 This spans the health system governance continuum from national and state governments and policy makers, to local health service decision makers, stakeholders, and importantly consumers. Collaboration is required up, down, and across this continuum to enable services to be delivered, which address local health priorities while being reflective of local culture and inclusive of all population groups, particularly minorities who are often those with the greatest need. The expanded Building Blocks Framework presented by Sacks and colleagues provides further guidance for those involved in planning, funding, and implementation of rural community health services by explicitly focusing on the role of community‐based health services and societal partnerships in order to effectively address local health priorities. 38

Community‐based participatory action research provides an opportunity to learn from those who understand the contextual nuances best, those living and working in their local communities. 17 , 30 Working together with researchers enables learning from one another, between traditional and mainstream services, building capacity of both community members, researchers, and health service personnel alike, while importantly contributing to the body of rural health research knowledge.

Researchers should consider collecting data and reporting to not only increase the evidence‐base regarding rural and remote health interventions and evaluation, 28 , 32 but also the process of engaging communities and the impact of such community engagement. 14 , 20 , 32 , 39 Such evidence will be invaluable to inform future planning from a policy level to local implementation decision‐making, enabling an informed approach to addressing the health inequities currently experienced in rural and remote populations and strengthening rural health systems as envisaged in the WHO Framework.

FUNDING

This research is supported through an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, supporting the doctoral research undertaken by D.A.S. This supporting source had no involvement in the study design, data analysis, report writing, or decision to submit for publication.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Deborah Stockton, Joanne Travaglia, Cathrine Fowler, Deborah Debono.

Data Curation: Deborah Stockton.

Formal Analysis: Deborah Stockton.

Funding Acquisition: Deborah Stockton.

Methodology: Deborah Stockton, Joanne Travaglia, Cathrine Fowler, Deborah Debono.

Project Administration: Deborah Stockton.

Supervision: Joanne Travaglia, Cathrine Fowler, Deborah Debono.

Validation: Joanne Travaglia, Cathrine Fowler, Deborah Debono.

Visualization: Deborah Stockton.

Writing ‐ Original Draft Preparation: Deborah Stockton (lead), Joanne Travaglia, Cathrine Fowler, Deborah Debono.

Writing ‐ Reviewing and Editing: Deborah Stockton, Joanne Travaglia, Cathrine Fowler, Deborah Debono.

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Deborah Stockton had full access to all of the data in this study and takes complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

TRANSPARENCY STATEMENT

Deborah Stockton affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the integrative review being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This integrative review forms part of the doctoral research undertaken by D.A.S. J.T., C.F. and D.D. were employed by University of Technology Sydney and completed their contributions to this paper in their roles as doctoral supervisors of D.A.S.

Stockton DA, Fowler C, Debono D, Travaglia J. World Health Organization building blocks in rural community health services: An integrative review. Health Sci Rep. 2021;4:e254. 10.1002/hsr2.254

Funding information Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adongo PB, Phillips JF, Aikins M, et al. Does the design and implementation of proven innovations for delivering basic primary health care services in rural communities fit the urban setting: the case of Ghana's community‐based health planning and services (CHPS). Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;12(1):1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allan J, Ball P, Alston M. ‘You have to face your mistakes in the street’: the contextual keys that shape health service access and health workers' experiences in rural areas. Rural Remote Health. 2008;8(1):1‐10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. International Labour Office 2015, Global evidence on inequities in rural health protection, social protection department, Geneva, Switzerland, ESS Document no 47.

- 4. McCabe S, Macnee CL. Weaving a new safety net of mental health care in rural America: a model of integrated practice. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2002;23(3):263‐278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Standing Council on Health . National Strategic Framework for Rural and Remote Health. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization . Scaling up Health Services: Challenges and Choices. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization . Everybody's Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes – WHO's Framework for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization . Increasing Access to Health Workers in Remote and Rural Areas through Improved Retention ‐ Global Policy Recommendations. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manyazewal T. Using the World Health Organization health system building blocks through survey of healthcare professionals to determine the performance of public healthcare facilities. Arch Public Health. 2017;75(1):50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546‐553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Farmer J, Clark A, Munoz SA. Is a global rural and remote health research agenda desirable or is context supreme? Aust J Rural Health. 2010;18(3):96‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Swindlehurst HF, Deaville JA, Wynn‐Jones J, Mitchinson KM. Rural proofing for health: a commentary. Rural Remote Health. 2005;5(2):411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aljasir B, Alghamdi MS. Patient satisfaction with mobile clinic services in a remote rural area of Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16(10):1085‐1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chilenski S, Ang P, Greenberg M, Feinberg M, Spoth R. The impact of a prevention delivery system on perceived social capital: the PROSPER project. Prev Sci. 2014;15(2):125‐137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cornwell L, Hawley SR, Romain T. Implementation of a coordinated school health program in a rural, low‐income community. J School Health. 2007;77(9):601‐606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dooley J, Kelly L, St. Pierre‐Hansen N, Antone I, Guilfoyle J, O'Driscoll T. Rural and remote obstetric care close to home: program description, evaluation and discussion of Sioux Lookout Meno Ya win health Centre obstetrics. Can J Rural Med. 2009;14(2):75‐79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Farmer J, Nimegeer A. Community participation to design rural primary healthcare services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):130‐139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fitzpatrick SJ, Perkins D, Luland T, Brown D, Corvan E. The effect of context in rural mental health care: understanding integrated services in a small town. Health Place. 2017;45:70‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gaudet A, Kelley ML, Williams AM. Understanding the distinct experience of rural interprofessional collaboration in developing palliative care programs. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14(2):2711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haggarty JM, Ryan‐Nicholls KD, Jarva JA. Mental health collaborative care: a synopsis of the rural and isolated toolkit. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(3):1‐10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morgan DG, Crossley M, Kirk A, et al. Improving access to dementia care: development and evaluation of a rural and remote memory clinic. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(1):17‐30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ong KS, Carter R, Kelaher M, Anderson I. Differences in primary health care delivery to Australias indigenous population: a template for use in economic evaluations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parker V, McNeil K, Higgins I, et al. How health professionals conceive and construct interprofessional practice in rural settings: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pesut B, Hooper B, Robinson C, Bottorff J, Sawatzky R, Dalhuisen M. Feasibility of a rural palliative supportive service. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15(2):1‐16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pidgeon F. Occupational therapy: what does this look like practised in very remote indigenous areas? Rural Remote Health. 2015;15(2):1‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Quinn E, Noble J, Seale H, Ward JE. Investigating the potential for evidence‐based midwifery‐led services in very remote Australia: viewpoints from local stakeholders. Women Birth. 2013;26(4):254‐259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Semansky R, Willging C, Ley DJ, Rylko‐Bauer B. Lost in the rush to national reform: recommendations to improve impact on behavioral health providers in rural areas. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(2):842‐856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith K, Grundy JJ, Nelson HJ. Culture at the centre of community based aged care in a remote Australian indigenous setting: a case study of the development of Yuendumu old People's Programme. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(4):1‐15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smith TA, Adimu TF, Martinez AP, Minyard K. Selecting, adapting, and implementing evidence‐based interventions in rural settings: an analysis of 70 community examples. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(4a):181‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sullivan E, Hegney DG, Francis K. An action research approach to practice, service and legislative change. Nurse Res. 2013;21(2):8‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Taylor J, Jones RM, O'Reilly P, Oldfield W, Blackburn A. The station community mental health Centre Inc: nurturing and empowering. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(3):1‐12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vanderpool RC, Gainor SJ, Conn ME, Spencer C, Allen AR, Kennedy S. Adapting and implementing evidence‐based cancer education interventions in rural Appalachia: real world experiences and challenges. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11(4):1‐14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Humphreys JS, Wakerman J, Wells R, Kuipers P, Jones JA, Entwistle P. "Beyond workforce": a systemic solution for health service provision in small rural and remote communities. Med J Aust. 2008;188(8 Suppl):S77‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Senkubuge F, Modisenyane M, Bishaw T. Strengthening health systems by health sector reforms. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:23568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Adam T, Ahmad S, Bigdeli M, Ghaffar A, Rottingen J. Trends in health policy and systems research over the past decade: still too little capacity in low income countries. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mutale W, Bond V, Mwanamwenge MT, et al. Systems thinking in practice: the current status of the six WHO building blocks for health system strengthening in three BHOMA intervention districts of Zambia: a baseline qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mounier‐Jack S, Griffiths UK, Closser S, Burchett H, Marchal B. Measuring the health systems impact of disease control programmes: a critical reflection on the WHO building blocks framework. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sacks E, Morrow M, Story WT, et al. Beyond the building blocks: integrating community roles into health systems frameworks to achieve health for all. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(Suppl 3):e001384‐e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Asha GS, Scott K, Sarriot E, Kanjilal B, Peters DH. Unlocking community capabilities across health systems in low‐ and middle‐income countries: lessons learned from research and reflective practice. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(7):43‐46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. King N, Symon G , Cassell C . ‘Doing Template Analysis’. Qualitative Organizational Research ‐ Core Methods and Challenges. London: Sage; 2012:426‐450. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.