Abstract

Artificial selection is a promising approach to manipulate microbial communities. Here, we report the outcome of two artificial selection experiments at the microbial community level. Both used “propagule” selection strategies, whereby the best-performing communities are used as the inocula to form a new generation of communities. Both experiments were contrasted to a random selection control. The first experiment used a defined set of strains as the starting inoculum, and the function under selection was the amylolytic activity of the consortia. The second experiment used multiple soil communities as the starting inocula, and the function under selection was the communities’ cross-feeding potential. In both experiments, the selected communities reached a higher mean function than the control. In the first experiment this was caused by a decline in function of the control, rather than an improvement of the selected line. In the second experiment, this response was fueled by the large initial variance in function across communities, and stopped when the top-performing community “fixed” in the metacommunity. Our results are in agreement with basic expectations from breeding theory, pointing to some of the limitations of community-level selection experiments which can inform the design of future studies.

Keywords: Artificial selection, microbial communities, propagule strategy, community functions

Introduction

Microbes form complex ecological communities consisting of large numbers of interacting taxa. The collective activity of all species within these communities can have important ecological and biotechnological impacts, for instance by affecting the health and life-history traits of their hosts (Berendsen et al. 2018; Santhanam et al. 2015; Fraune and Bosch 2010; Human Microbiome Project Consortium 2012; Hu et al. 2016), or by producing valuable products from waste materials (Minty et al. 2013; Bernstein and Carlson 2012; Wang et al. 2016; Shong, Jimenez Diaz, and Collins 2012). The collection of ecosystem services and all other emergent traits and properties of microbial communities can be referred to as their “functions” (Sanchez-Gorostiaga et al. 2019). Manipulating community composition towards desirable collective functions and away from undesirable ones has become an important aspiration in microbiome biology and biotechnology (U. G. Mueller and Sachs 2015; Sheth et al. 2016; Eng and Borenstein 2016; Rillig, Tsang, and Roy 2016).

To accomplish this goal, one approach has been to rationally engineer communities by mixing microbial species with known traits (Eng and Borenstein 2019; Minty et al. 2013; Gilbert, Walker, and Keasling 2003; Regot et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2016; R. P. Smith, Tanouchi, and You 2013). An important challenge of these synthetic approaches is the factorially growing number of interactions as the communities grow in size. This challenge is important, as these pairwise and high-order interactions can limit our ability to predict the function of even mid-size consortia (10 taxa or more) (Sanchez-Gorostiaga et al. 2019; Senay et al. 2019; Gould et al. 2018; Mickalide and Kuehn 2019; Sanchez 2019; Guo and Boedicker 2016). A second important challenge was pointed out by Goldman and Brown: engineered functions in synthetic consortia can be affected both by ecological processes (e.g. invasions, species extinctions, population dynamics) as well as by rapid evolution within the community (Goldman and Brown 2009; Escalante et al. 2015). As a result, a microbial consortium that is engineered to carry out a desired function must be also designed to be both evolutionarily and ecologically stable (a problem that is far from trivial (Rauch, Kondev, and Sanchez 2017; Shade et al. 2012)), if we want that function to be stable over time.

These challenges of engineering community functions have motivated a surge of interest in evolution inspired approaches, which treat the community as a unit of selection and explore its ecological landscape in search of consortia with desirable traits (Swenson, Wilson, and Elias 2000; Arias-Sánchez, Vessman, and Mitri 2019). This approach has been found to work in silico (Xie, Yuan, and Shou 2019; Williams and Lenton 2007a; A. Penn 2003; Williams and Lenton 2007b; Doulcier et al. 2020) and it has been attempted several times in the laboratory to optimize functions such as toxin removal (Swenson, Arendt, and Wilson 2000), the manipulation of environmental pH (Swenson, Wilson, and Elias 2000), or the modulation of various host traits (Panke-Buisse et al. 2015; Panke-Buisse, Lee, and Kao-Kniffin 2016; Swenson, Wilson, and Elias 2000; Ulrich G. Mueller et al. 2016; U. G. Mueller and Sachs 2015; Jochum et al. 2019; Gopal and Gupta 2016). The results of these experimental studies have been mixed (Blouin et al. 2015; Arora, Brisbin, and Mikheyev 2019), and it is becoming increasingly clear that the details of how exactly the “offspring” communities are generated from the “parental” communities can be critical for the success of this approach (Raynaud et al. 2019; Ulrich G. Mueller et al. 2016).

One way to generate offspring communities can be thought of as being akin (in a metaphorical sense) to “asexual” reproduction (Swenson, Wilson, and Elias 2000) and has been termed the “propagule method” (Charles J. Goodnight 2011; Michael J. Wade 1978). In this method, an “offspring” community is seeded by taking a small aliquot of its “parent” community (containing a randomly sampled group of individuals) and introducing it into fresh new habitats (Fig. 1A) (M. J. Wade 1976). Thus, each selected community acts as the single parental community that seeds a new crop of N>1 new offspring communities. This method was introduced in artificial single-species group selection experiments (See (Michael J. Wade 1978) and references therein), and it has been used in at least three additional artificial selection studies at the ecosystem level (Swenson, Wilson, and Elias 2000; Raynaud et al. 2019; Arora, Brisbin, and Mikheyev 2019).

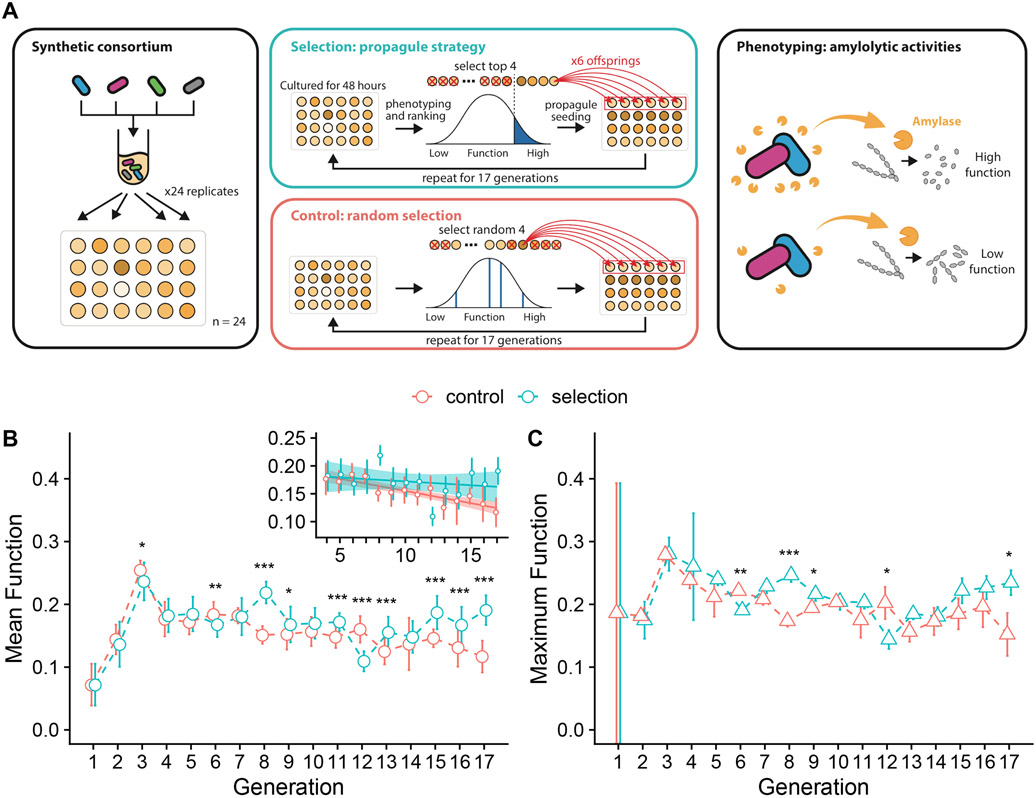

Fig. 1. Artificial selection of an amylolytic consortium.

A. Experimental scheme. B. Community function (f) is defined as the fraction of starch hydrolyzed by the community filtrate after a time t: Function (f=1-S[t]/S[0], where S[t] is the starch concentration in the reactor after a time t, S[0]=0.1%w/v; Methods). Turquoise circles represent the mean functions (± 1 SD) of the 24 communities in the selection line. Red open circles represent the random control line. Asterisks indicate generations in which the community functions differ significantly between selection and control lines (Welch’s two-sample t-test. *** indicates p < 0.001, ** indicates p<0.01, * indicates p<0.05; N=48 for each test). Inset shows the linear regression of mean community function to the rounds of selection (generations), starting right after the beginning of the stable phase at generation 4 (slope = −0.0013, P = 0.44 for selection line; slope = −0.004, P < 0.001 for control line). C. Highest community function in each generation for both the selection (red) and the control lines. Turquoise triangles represent the mean of the triplicate measurement of the best performed community (± 1 SE, N=3) in the selection line. Red triangles represent the control line. Asterisks denote the same significant levels as in B (Welch’s two-sample t-test; in all cases N=6).

The objective of this paper is to report the outcome of two independent experiments that used propagule strategies for community reproduction. We note that our intention is not to systematically and directly compare the outcomes of both experiments, as they differ in the amount of community variability in the starting community pool, in the experimental design, and in the function under selection. Despite these differences, some general patterns are found, and our goal is to make the results available to the community so they can be of use for the future design of new experiments and protocols. In the Results section we will limit ourselves to describe the two experiments and their outcomes, which we will then unpack in the Discussion.

Methods

Amylolytic communities. Strains, reagents, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC)(Manassas, VA, USA): Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 23857), Bacillus megaterium (ATCC 14581), Paenibacillus polymyxa (ATCC 842), Bacillus licheniformis (ATCC 14850). The ability of these strains to degrade starch was characterized in (Sanchez-Gorostiaga et al. 2019) (except for B. licheniformis, which is shown in Fig. S1) and their amylolytic rates are reported in Table S1. Glycerol stocks for each strain were struck out on nutrient broth agar (3 g beef extract; 5 g peptone; 15 g agar per 1 L of deionized water) supplemented with +0.2% starch (w/v, soluble, Sigma-Aldrich). Individual colonies were used to inoculate starter cultures (1 mL; overnight; 30°C). An initial inoculum was prepared by mixing 400 μL of overnight monocultures of each of the four strains at equal ratios (100 μL of each strain; target OD = 0.025 at 620 nm for each strain) in 1× bSAM media (Sanchez-Gorostiaga et al. 2019). To begin the amylolytic community selection experiment, all wells of a 24-well plate were filled with 900 μL of newly prepared 1× bSAM and each well was inoculated with 100 μL of the initial inoculum pool prepared above (initial OD620 = 0.01 in a 1 mL volume, i.e. ~107 cells). Such a high number of cells makes it very unlikely that species will go randomly extinct due to passaging alone. The plate was covered with aeroseal rayon film (Sigma) and grown for 48hr at 30°C without shaking. After that time, a 500 μL volume of each culture was filtered-sterilized (0.2 um centrifugal filter; nylon membrane; VWR 82031-358) and assayed in technical triplicate for enzymatic starch hydrolysis (see measuring amylolytic function below). OD620 (100 uL; Multiskan Spectrophotometer; Fisher Scientific) was measured for the four communities with the highest amylolytic function and for four randomly selected communities (chosen by random number generation in Mathematica). Each of the four communities with highest function was then used to inoculate six “offspring” communities (all in 1 mL 1× bSAM) in a 24-well artificial selection plate. Each of the four randomly selected communities was in turn used to inoculate the random selection plate. A third plate was established as a non-inoculated growth media-only control. The starting population density for all cultures was adjusted to OD620=0.01, by diluting from the parent cultures. Incubation, amylolytic assay, and inoculation of offspring communities were repeated every 48hr for a total of 17 cycles. Reagents used throughout the experiment were identical to those used in (Sanchez-Gorostiaga et al. 2019), and growth and assay media were prepared in the same manner as described therein.

Measuring amylolytic function.

A 500 μL volume of culture from each well was filtered-sterilized and assayed in technical triplicate for enzymatic starch hydrolysis. Three technical assays for each supernatant were carried out in a 96 well plate (Corning 3596). Per reaction, 20 μL of enzyme supernatant was added to 180 μL of 0.1% w/v starch solution and incubated for T=10 min at room temperature. The fraction of starch degraded over that incubation time was determined using the quantitative Lugol iodine staining method described in (Inaoka and Ochi 2011; Sanchez-Gorostiaga et al. 2019), and which was in turn adapted from the classic Fuwa method (Fuwa 1954), as fsta = 1 − (OD690(T)/OD690(0)), where OD690 is the optical density at 690 nm. For each assay plate, a negative control for both M9 media and 1× bSAM was also measured in triplicate as well as a standard curve (0.2%; 0.05%; 0.0125%; 0.003125% starch in M9). The amylolytic function of each community was determined as the fraction of starch degraded in the above assay.

Sample collection for cross-feeder communities.

12 soil or leaf samples were collected at 12 different sites in and around Yale University West Campus in West Haven, CT, USA, and Yale University Campus in New Haven, CT, USA. For each sample at one collection site, five leaves or five scoops of soil within one meter radius were collected and pooled into one sample using sterilized tweezers or spatula. One gram of collected sample was placed in a 15 mL sterile tube and resuspended in 10 mL of 1× phosphate buffered saline supplemented with 200 μg/mL of cycloheximide to inhibit eukaryotic growth. Samples were homogenized by vortexing and were allowed to sit for 48hr at room temperature. The supernatant solutions were used as inoculum for later experiments (see section below).

Habitat inoculation, media, and cross-feeder community growth.

Communities were grown in 0.2% citrate-M9 medium, prepared as described in (Lu et al. 2018) from the same stocks and reagents. 500 μL of culture media was added to each well of a 96-well deep-well plate (VWR). The first cell passage was supplemented with cycloheximide at a concentration of 200 μg/mL. Starting inocula were obtained directly from inoculating 4 μL of the supernatant of initial microbiota solution to 500 μL of culture media. Eight of the twelve environmental samples were sampled into eight wells each. The other four were inoculated into seven wells, obtaining a total of 92 inoculated wells on the initial 96-well plate. The remaining four wells on this plate were left for blank as media control (see Fig. 2A for 96-well plate layout). Plates were covered with Aerogel film (VWR) and incubated at 30°C for 48hr without shaking, then each community was homogenized by pipetting up and down 10 times. This initial plate was then replicated into two plates by inoculating 4 μL of grown media into 500 μL of fresh media. The two replicate plates corresponded to the selection line and the control line in the first community generation of the selection experiment. Both plates underwent six rounds of selection under the same incubation conditions described above, but differed in the communities selected to be propagated in each generation (top 25% or randomly selected 25% of communities are selected in the selection and the control plates, respectively, see selection schemes below).

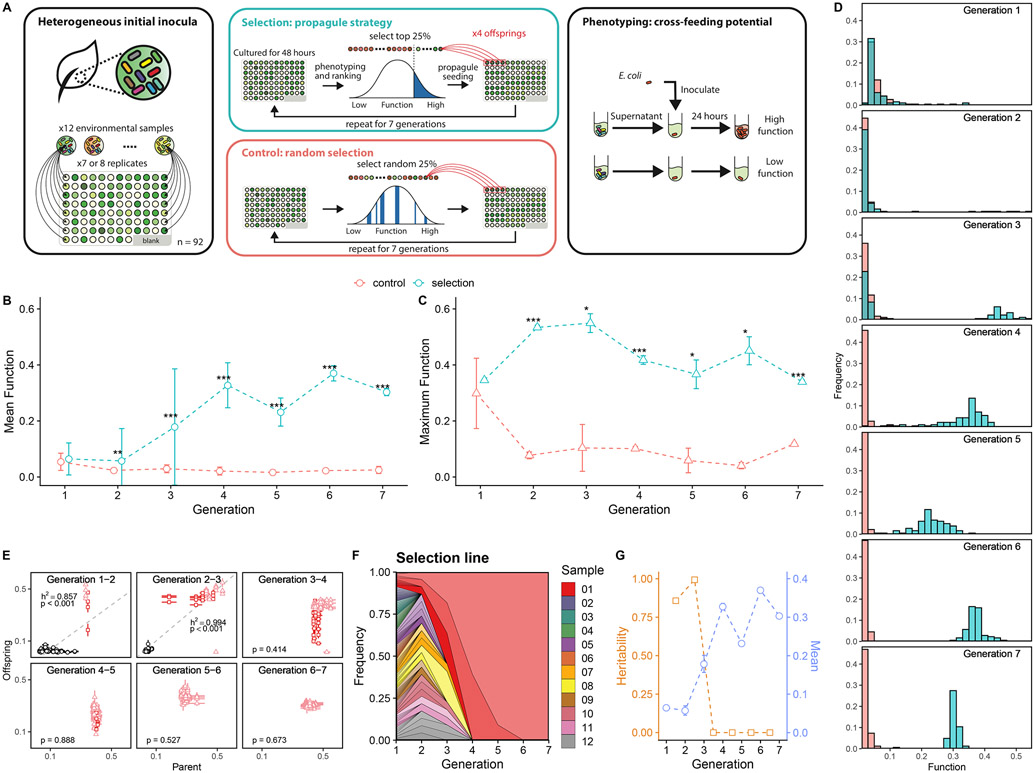

Fig. 2. Artificial selection of cross-feeder communities.

A. Experimental scheme: the artificial selection on the cross-feeding potentials of communities on a target organism E. coli. Cross-feeder communities were obtained from 12 leaf and soil samples and grown on citrate-M9 medium. Community function (f) is determined by f=Yc/Yg, where Yc is the yield of E. coli grown on community filtrate as the only carbon source and Yg is the E. coli yield growing on a glucose-M9 medium. B. Mean community function over generations. Green circles represent the mean functions of 92 cross-feeder communities (± 1 SD) in the selection line. Red circles represent the random control line. Asterisks indicate generations in which the community functions differ significantly between selection and control lines (Welch’s two-sample t test. *** indicates p < 0.001, ** indicates p<0.01, * indicates p<0.05; from generation one to seven: N=184, 184, 180, 184, 180, 176, 164, respectively. Sample sizes vary because of removal of cross-contaminated wells. Methods). As shown in Fig. S2, the unnormalized function Yc exhibits the same qualitative response to selection we find for the normalized case. C. Maximal community function. Green triangles represent the mean of the triplicate measurement of the best performed community (± 1 SE, N=3) in the selection line. Red triangles represent the control line. Asterisks denote the same significant levels as those shown. D. Distribution of community functions in the selection and control lines over the seven generations. Bins are semi-transparent to show the overlapped counts in each line. E. Community functions of parent-offspring pairs in the selection line. Light red triangles denote the lineage of the dominant community that eventually spread over, dark red squares denote the lineage of the second dominant community (the last community being dropped), and the black circles represent the other lineages. Error bars are the standard errors of mean in the triplicate measurements. Grey dashed line represents the mean fitted linear regression from 1000 bootstraps. P-value reported here represents the fraction of non-significant linear regression slopes in 1000 bootstraps, e.g. P<0.001 means that linear regression of every bootstrapped data gives a significant slope (see Methods). The regression slope is an estimate of the trait heritability at the community-level (Blouin et al. 2015; C. J. Goodnight 2000). F. Muller plot showing the fraction of the metacommunity in the selection line that is made up by the “descendants”of the different starting communities. The plot shows the rapid “fixation” of the dominant, highest function community. Each color represents one of the 12 soil and leaf samples from which the cross-feeder communities were initially inoculated. G. Heritability (h2) and mean function (± 1 SE) of the selection line at different rounds of selection (generations). The mean function is the as shown in A. The heritability drop after the fourth selection round coincides, as expected, with the lack of further response of the mean to selection.

Community phenotyping and selection scheme.

In the first community generation, communities in the 96-well plates were grown for 48hr in 0.2% citrate-M9 media. To obtain the supernatant for community phenotyping, 200 μL of the grown media was spinned down at 3000 rpm for 15 minutes in an Eppendorf 5810 tabletop centrifuge and its supernatant was filter-sterilized using a 0.2 uM membrane 96-well filter (VWR 97052-096). The rest of the unfiltered grown media was kept at 4°C for up to 30hr as the inoculum for the next generation. The filtrate of each community was mixed with 200 μL of 2× M9 salts to make 400 μL of 1× M9 medium with the filtrate as the only source of carbon. 100 μL of this filtrate-M9 medium was dispensed to three wells of a 384-well deep-well plate (VWR), which enables us to measure the community function in N=3 technical replicates. To 20 additional wells, we added 100 μL of 0.2% glucose-M9 medium as a positive control. The border wells of the 384-well plate were filled with water and not used for cell culture in order to reduce the edge effect caused by evaporation. To inoculate all the wells with media, we prepared a pre-culture of Escherichia coli (strain nohQ::Kan deletion strain from the Keio collection (Baba et al. 2006), derived from JW1541). The E. coli pre-culture was prepared by growing a colony in 15 mL of 1× LB medium with 15 μg/mL kanamycin in a 50 mL tube for 24hr at 37 °C. This was followed by a 3× washing procedure in which 4 mL of grown culture was centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 3 mins and the pellets were suspended in 4 mL of 1× PBS. The final washed E. coli inoculum was diluted with additional 16 mL of 1× PBS, and 2 μL of this washed pre-culture was used to inoculate each well of the cross-feeder community supernatant and M9-glucose medium on the 384-well plate. The 384-well plate was then incubated at 37 °C for 24hr without shaking, and then OD620 of the grown cultures was measured using a plate spectrophotometer (Fisher Scientific Multiskan Spectrophotometer). Unexpected bubbles in the wells of 384-well plates caused by pipetting may result in false high OD620 measures. Such replicates were detected by high standard errors (>0.05) of triplicate measurements and were removed from the analysis. The number of communities with a removed replicate are N=3 (one replicate in each of three communities) for the control line and N=7 for the selection line at the first generation.

The function for each community was determined as f=Yc/Yg, where Yc is the yield of E. coli grown in the community filtrates and Yg is the yield of E. coli grown in glucose-M9 cultures Yields are determined by optical density (OD620). In the selection line, the top performing 23 communities (25% of 92 communities) were chosen to reproduce (parental communities) and each of them was used to inoculate four offspring communities in the next generation. The same procedures were implemented on the control line in which the only difference was that random 23 communities, instead of the top communities, were chosen to propagate. At generation four, an unexpected cross-contamination occurred in one of the four citrate-M9 blank wells on the selection line plate and it was accidently selected to propagate the later generations due to its high performance. Because we cannot trace the ancestral community of this lineage, we removed it from the analysis. Similar cross-contamination occurred in one blank well at generation two and was propagated to the next generation. Although these four offsprings were not passaged further, they were also removed from the analysis because we cannot trace their ancestry. From generation one to seven, the number of removed wells in the selection line due to cross-contamination are N=0, 0, 4, 0, 4, 8, and 20, respectively. The R script for the removal process is available on the corresponding GitHub repository.

Statistical analyses.

To compare the evolutionary trajectories between the selection and control lines, we performed the Welch’s t-tests on their average community functions at each generation. For amylolytic communities, N=48 (24 per line). For cross-feeding communities, N was variable due to the removal of cross-contaminated wells from the analysis. From generation one to seven, the sample sizes are N=184, 184, 180, 184, 180, 176, 164, respectively. To test whether the function of the best community improved in response to selection, we compared the maximum function in the selection line to that in the control line at each generation. In Fig.1, for the amylolytic communities To do so, we chose the single best community, each having triplicate technical readouts, from both selection and control lines, and compare the difference between these two communities in their functions using t-tests (N=6; three replicates per community per line). To test whether the aggregated community function metrics (mean and maximum) in the selection and random lines respectively show a monotonic trend over the time course of the selection experiment, we performed Mann-Kendall tests on the metrics in both of the experiments described in Fig. 1A-B and Fig. 2B-C. The sample size is related to the number of community generations: the first selection experiment has N=14 (excluding the first three generations of stabilization) and the second experiment has N=7. The analysis R scripts are available on the GitHub repository.

Heritability characterizes the fraction of the heritable variation in community-level functions relative to the total variation which also includes all non-heritable environmental sources, such as measurement and pipetting errors, temperature fluctuations in the incubator etc. By comparing the offspring and parent functions, one can estimate the heritability as the slope of linear regression following e.g. (Blouin et al. 2015). In Fig. 2E the function of the parent and offspring communities was measured in three biological replicates. To account for this, we performed a bootstrapped linear regression procedure to estimate the heritability for the selection line in the second experiment. For each parent-offspring measurement pair within a selection round, we randomly sampled the parent and offspring functions from their respective triplicate measurements. We then performed a simple linear regression of parent function over offspring function and recorded the significance level of its slope. This procedure was repeated 1000 times for each selection round. If more than 95% of the bootstrapped linear regression returns a statistically significant slope, we reported the mean of the bootstrapped slopes as the estimated heritability. Otherwise, we set h2=0.

Results

Artificial selection of an amylolytic consortium.

Designing communities for efficient biodegradation has long been an aspiration of synthetic ecology and community engineering (Piccardi, Vessman, and Mitri 2019; Gilbert, Walker, and Keasling 2003; Yoshida et al. 2009; Zanaroli et al. 2010), and it has also been a problem of interest in artificial community-level selection and microbial bioprospecting (Swenson, Arendt, and Wilson 2000; Zanaroli et al. 2010; Cortes-Tolalpa et al. 2016; Eng and Borenstein 2019). In particular, the hydrolysis of complex polymers into smaller molecular weight molecules (which can be then metabolized into useful byproducts by other community members) is often a limiting step in bioconversion (Yang et al. 2016; Kim et al. 2014; Minty et al. 2013). As a proof of concept, we set out to apply artificial selection to find a community with an enhanced ability to hydrolyze starch. While the hydrolysis of starch is not in general as challenging as that of other polymers (e.g. cellulose), it is also of value for industrial applications (de Souza and de Oliveira Magalhães 2010; Xu, Yan, and Feng 2016). In our experiments, we used soluble starch as a substrate, as its hydrolysis has been recently characterized as an ecological function at the community-level (Sanchez-Gorostiaga et al. 2019) that is relatively straightforward and inexpensive to characterize in high-throughput (Fuwa 1954).

Our starting point was a set of strains of soil bacteria whose amylolytic ability we have recently characterized (Sanchez-Gorostiaga et al. 2019), including B. subtilis, B. licheniformis, B. megaterium, and P. polymyxa (Methods). As described in the methods section, the four species were mixed together in equal ratios to form the initial inoculum, which contained 24 communities. The experimental population of communities (i.e. the metacommunity (David Sloan Wilson 1992; Charles J. Goodnight 2011)) contains 24 communities. To begin the experiment, all wells of a 24-well plate were seeded from the inoculum and allowed to grow for 48hr as described in Methods. The function of each community represents the fraction of starch degraded over a 10min incubation period by 20 μL of its filtered medium at 30°C (Methods). The four communities with the highest function were used as the inoculum for a new generation of communities (Fig. 1A, Methods). As a control, a random treatment was started where 4 communities were randomly selected in each generation as the inocula to seed the next generation (Fig. 1A, Methods).

The mean amylolytic activity for both treatments is shown in Fig. 1B. Both treatments are initially indistinguishable and follow identical trends, with an initial rise in the mean function that ends on the third generation, followed by a stable phase where the function varied little over time. The selected treatment had a higher mean function than the control in the last three days of the experiment (Welch’s two-sample t-test, P<0.01, N=48 in each test) (Fig. 1B). However, this is not caused by an increase in the mean function in response to selection, which in fact remains stable after the stabilization phase starts on generation 4 (Mann-Kendall Test τ = - 0.14, P=0.47, N=14), but rather by a statistically significant decline in the mean function of the control line over time (Mann-Kendall Test τ = −0.67, P<0.001, N=14)(Fig. 1B; Inset). The same pattern was observed when we measured the function of the top community (out of the N=24 communities in the metacommunity). The maximum function in the community is also stable in the artificial selection line (Mann-Kendall Test τ = −0.25, P=0.21, N=14) after the third generation, but it exhibits a statistically significant decline over time in the control (Mann-Kendall Test τ = −0.58, P=0.004, N=14) (Fig. 1C). The lack of response to artificial selection in our experiments is consistent with the absence of a significant heritable component of the community-level functional variance (C. J. Goodnight 2000) (h2=0.05, P=0.3, estimated by regressing the offspring to the parent functions following (Blouin et al. 2015)) .

Artificial selection of a cross-feeder community.

A promising application of microbial community engineering (Jousset et al. 2016; Wei et al. 2015) is biocontrol. Biocontrol encompasses both the suppression of pathogen growth (Berendsen et al. 2018; Mendes et al. 2011) and the promotion of other (potentially beneficial) organisms or hosts. In the second experiment, we set out to use artificial community-level selection to find a community that would strongly promote the growth of a target organism (Fig. 2A). Our target organism was an E. coli strain that cannot grow aerobically on citrate (the only externally supplied carbon source in the growth medium) (Fig. 2A). Although this strain cannot grow on its own on citrate minimal medium, it could potentially feed off the secreted metabolic byproducts of other taxa. We can thus quantify the cross-feeding ability of a given community towards this E. coli strain by measuring the growth yield (Yc) of said strain in citrate medium supplemented with the byproducts of that community (Fig. 2A; Methods). For internal consistency, and to control for batch effects and day-to-day errors in media preparation, incubator temperature, etc., this yield was normalized to the yield of the same E. coli strain growing in glucose minimal media (Yg) on the same plate, incubator, and media as the rest of the experiment. This ratio represents the function under selection (Methods).

Following previous work (Goldford et al. 2018; Lu et al. 2018) we started the experiment by suspending 12 different leaf and soil samples in M9 minimal medium, thus creating a heterogeneous set of starting inocula. Each inocula seeded seven or eight independent habitats as described in Methods. The plate was incubated at 30°C without shaking for 48hr. At the end of that period, a volume of 50 μL of the filtrate of each community, supplemented with 50 μL of 2× M9 salts, was added to a different replicate E. coli culture as the only carbon source. The cultures, containing E. coli on 100 μL 1× M9 with community fitrate, were grown on a 384-well plate for 24hr at 30°C without shaking. The yield of these cultures (Yc) were determined by spectrophotometry, and normalized by the yield of an E. coli culture in the same plate and using M9 glucose as the only carbon source (Yg). The 23 communities whose filtrate had yielded the highest E. coli growth (highest community functions; f=Yc/Yg) were selected, and used to inoculate four habitats each to a total of 92 communities in the offspring generation (Methods). This artificial selection process was repeated for seven generations. Similar to previous studies (Swenson, Arendt, and Wilson 2000; Swenson, Wilson, and Elias 2000) we generated a random selection control line, where each generation we selected 23 random communities and each was used to inoculate four new habitats. Other than that, the control experiments were performed in the exact same manner and using the same media and incubator as the artificial selection line (Methods).

We quantified the function of each community as described in the Methods section. We then determined the mean function in the metacommunity in each round of selection (generation), which we plot in Fig. 2B. The mean function of the random-selection control remained low throughout the experiment. By contrast, the mean function of the artificial selection line exhibited a strong initial response to selection, increasing by five-fold over the first three rounds of selection and leveling off after the fourth generation. At the same time, and despite this strong response of the mean, we also found that the function of the best performing community did not improve in response to selection, remaining high but approximately constant over the experiment (Mann-Kendall test τ = −0.24, P = 0.56, N=7) (Fig. 2C).

When we plotted the distribution of community-functions at different generations, we found that the initial distribution (i.e. for the communities that were seeded from the heterogeneous set of soil inocula) was long tailed (Fig. 2D). This heritability of this community-level trait is initially very high (h2>0.85 over the first two rounds of selection, P<0.001) (C. J. Goodnight 2000): offspring communities that were seeded from a high function parent also had a high-function in the next generation, whereas those seeded from a low function community remained low in the next generation (Fig. 2E). As community-level selection proceeded, the metacommunity became more functionally homogeneous as the fraction of descendants from the initial inoculum of highest function grew (Fig. 2E). By the fifth generation, all of the communities were “descendants” of the two high-function initial inocula, and in the sixth generation a single soil inocula dominated (Fig. 2F). Once the metacommunity is entirely made up of replicates of the top initial community and the initial functional variance is entirely “spent” (Fig. 2G), the response to selection stops: the heritability h2 plummets, and becomes non-significant in the last three selection rounds (Methods).

Discussion

We have presented the results of two artificial selection experiments on bacterial communities that utilized the “propagule” strategy (M. J. Wade 1976; Michael J. Wade 1978; Charles J. Goodnight 2011) to attempt to select for an optimized community function. The two experiments have important differences. However, they both highlight some of the main limitations of propagule based selection for communities of asexually reproducing microbes, and both illustrate the critical role of (heritable) community-level variability in artificial community-level selection (C. J. Goodnight 2000). In particular, we expect from the breeder’s equation that when the amount of heritable phenotypic variation is high, the response of the mean trait to selection will be strong, whereas when it is negligible, no response will be observed. As pointed out by others, any group-level selection requires (heritable) differences between the groups (M. J. Wade 1976; J. M. Smith 1964; Lewontin 1970).

One critical difference between the two experiments is the degree of functional variability in the starting community. When we designed the first experiment, part of what we wanted to learn is to what extent functional variability between communities in the metacommunity could be supplied by endogenous processes, such as spontaneous mutations or random transitions in ecological states. To that end, we seeded all 24 initial communities from the same synthetic, low diversity initial pool which consisted of four clonal strains of asexually reproducing bacteria. We found that the heritability was not significant, and consistent with that finding neither the mean nor the maximum community function in the selection line improved in response to selection. Yet, both were higher in the artificial selection line than in the random selection control at the end of the experiment. This relative difference between the experimental and control lines was caused by a decline in the function of the random selection control during the stabilization period. This outcome is in line with previously reported results (e.g. (M. J. Wade 1976; Swenson, Wilson, and Elias 2000)), where the effect of artificial community-level selection was more apparent in relative terms (i.e. by comparison to a random or no-selection control) than in absolute terms (i.e. as marked by an increase in function relative to the ancestral community). We observed little positive selection at the community level in this first selection experiment on amylolytic consortia.

We found this information helpful when we designed the second experiment. In previous successful artificial group-selection experiments, either populations or communities of sexually reproducing organisms (belonging to the beetle genus Tribolium) were started from a stock culture with high genetic variation (M. J. Wade 1976; Charles J. Goodnight 1990). Inspired by this and with the goal of stimulating a strong response to community-level selection, we sought to start a population of communities (a metacommunity) with high initial between-community functional and compositional variance, by seeding the communities from twelve different soil or leaf inocula. The initial functional variance in the metacommunity was indeed high (Fig. S3), and this variance was highly heritable (h2>0.85, P<0.001 over the first three generations). The large initial variance in community function fueled the strong response to selection observed in the first few rounds of selection. The increase in mean function ended when this heritable variance was “spent” (the heritability h2 was not statistically significant after the third selection round, P>0.05), and the highest performing community in the initial pool had fixed (Fig. 2F-G). The maximum function in the metacommunity did not increase and remained approximately constant over time. This finding indicates that the main effect of artificial selection was again to enrich the metacommunity with highly similar high-function communities (all of which were descendants of the same ancestral community), rather than improving the function of the highest performers. This suggests that the artificial selection protocol we implemented would have not worked better than simply taking the best performing community at the beginning of the experiment, and propagating it without selection (i.e. a simple exercise of bioprospecting at the community-level, or “eco-prospecting”)

For both of these experiments, it is reasonable to speculate that an improvement in the community-level function is likely to align against selection at the individual (cellular) level. For instance, a mutant with a higher amylase production than its ancestor may engage in an ecological public-goods evolutionary game (Hauert, Holmes, and Doebeli 2006; Rauch, Kondev, and Sanchez 2017; Hauert, Wakano, and Doebeli 2008), and be selected against due to the higher cost of amylase production (Harrington and Sanchez 2014; West et al. 2006). In the second experiment, mutants that are capable of using the metabolic byproducts secreted by other species in their community would have a growth advantage, by being able to expand into open niches. This expansion would in turn deplete those resources, lowering the amount of cross-feeding towards E. coli. We would thus anticipate that evolution is likely to erode both of those functions over time. Such potential conflicts between individual-level selection and desired community-level functions are recognized as important hurdles for the engineering of microbial consortia for biotechnological purposes (Xie, Yuan, and Shou 2019; Goldman and Brown 2009; Escalante et al. 2015). We speculate that, since cheater fixation will lead to lower community functions in both experiments, continuous artificial selection may prevent cheater invasion by removing from the metacommunity those communities where they arise.

Our results hint at some of the limitations and strengths of the propagule selection strategy. On the strengths side, we find that community traits are reliably passed from parent to offspring communities. Additionally, we find in both experiments that artificial selection is efficient at purging from the metacommunity those communities whose function has degraded. On the weaknesses side, the propagule strategies failed to improve the function of the best performing communities in our experiments. We speculate that this may be due to the lack of new variation entering the metacommunity through mutational processes alone, which is thus unable to overpower the non-heritable variation in function between communities. The latter may arise from multiple sources, including measurement error when we quantify the function of each community, sampling stochasticity when we inoculate the offspring communities, and experimental day-to-day variation in media preparation, temperature fluctuations in the incubator, and other experimental artifacts (Xie, Yuan, and Shou 2019)

Beyond the propagule strategies, it is worth elaborating on the strength and limitations of applying artificial selection to microbiomes. A key strength is that, by contrast to purely synthetic approaches that seek to rationally engineer communities by mixing species with known traits, the directed evolution of microbiomes may help us find surprising or hitherto unknown combinations of species that carry out a function better than we would have originally predicted, and which are also ecologically and evolutionarily stable. Among the limitations is that selection is only efficient (see for instance Fig. 2G) when the amount of heritable variation (i.e. that which stems from differences in species composition) among the communities is high. Every round of selection, however, reduces this heritable variance. A result is that the response to selection declines rapidly after the first few selection rounds, as we have seen. It is thus critical in future approaches to devise strategies that replenish heritable variation after each selection step, through either ecological or mutational means.

It is important to remark, at this point, that only that variation that is heritable can respond to selection. Those differences in community composition that are due to transient ecological dynamics (i.e. to communities not being in equilibrium), stochastic fluctuations in species abundances, rapid and random fluctuations in environmental conditions, or simply experimental error in determining the function of all communities will not contribute to the success of artificial selection (Blouin et al. 2015; A. S. Penn and Harvey 2004; C. Y. Chang et al. 2020). Quite the contrary: if strong enough, these non-heritable sources of variation can mask the heritable variation, diminishing heritability and therefore the response to selection (Blouin et al. 2015; C. Y. Chang et al. 2020; Sanchez et al. 2020). Therefore, future attempts to apply artificial selection at the community level should take great care to minimize those sources of variation, for instance, as we have recently discussed at length, ensuring that the environment is as stable as possible, and that communities are in a generationally stable state before selection is applied (C. Y. Chang et al. 2020; A. S. Penn and Harvey 2004)

Other limitations of community-level selection include, as we point out above, conflicts between individual level fitness and the collective function we seek to optimize. The potential effect of these conflicts for artificial selection of microbial communities have been recently examined at length (Xie, Yuan, and Shou 2019), and they have also been discussed for many decades in theoretical studies of group-selection, e.g. (J. M. Smith 1964; Levin and Kilmer 1974; D. S. Wilson 1975; Traulsen and Nowak 2006). The theoretical framework of the social evolution theory of microorganisms (West et al. 2006) may inform us on how to devise protocols of artificial selection that ameliorate this limitation.

Our experiments have several limitations, which are shared with many other published experiments (Swenson, Wilson, and Elias 2000; Panke-Buisse et al. 2015) but may still limit the scope of our findings. First, we only had one artificial selection and one random selection line in each experiment. These two experiments are very labor-intensive and it would have been logistically challenging to even double the number of lines in both cases. Yet, it has been rightfully argued that a lack of replication in artificial selection experiments is an important concern (U. G. Mueller and Sachs 2015), and this critique would also extend to both experiments reported here. Investigating how the community composition varied between the selected and non-selected lines may have clarified the role of ecological versus evolutionary processes. We did not save those samples, so unfortunately this is beyond the scope of what is now possible.

Despite these shortcomings, we believe we have drawn valuable lessons from both of these experiments and thus that they are worth reporting. In the first experiment, the low positive selection we detected is concomitant with low heritability. In the second experiment, the strong positive selection we observed in the initial selection rounds was driven by high initial heritability, and it weakened as the heritability declined over time. These outcomes of artificial selection at the level of complex multispecies microbial communities are both consistent with standard expectations of evolutionary theory at any level of selection (Lewontin 1970). Looking to the future, and given the considerable challenges of doing these experiments in high-throughput (but see (Blouin et al. 2015)), we suggest that simulations such as those performed elsewhere (Williams and Lenton 2007a, [b] 2007; Xie, Yuan, and Shou 2019; Doulcier et al. 2020) will be very useful to explore different selection regimes, and thus to extract generic conclusions. Such efforts will be critical in order to develop a Theory of artificial selection of microbial communities that can guide the design of new protocols and experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Maria Rebolleda-Gomez, Sylvie Estrela, Jean Vila and all other members of the Sanchez lab for their input and comments on the manuscript. The funding for this work partly results from a Scialog Program sponsored jointly by Research Corporation for Science Advancement and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through grants to Yale University (AS). This work was also supported by a young investigator award from the Human Frontier Science Program (RGY0077/2016) and by the National Institutes of Health through grant 1R35 GM133467-01 to AS. CYC was supported by a graduate fellowship from the Ministry of Education, Taiwan (Government Scholarship to Study Abroad).

Footnotes

Data storage: All data in this paper and all data analysis scripts are publicly available and stored on Dryad (C.-Y. Chang et al. 2020).

References

- Arias-Sánchez Flor I., Vessman Björn, and Mitri Sara. 2019. “Artificially Selecting Microbial Communities: If We Can Breed Dogs, Why Not Microbiomes?” PLoS Biology 17 (8): e3000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora Jigyasa, Brisbin Margaret Mars, and Mikheyev Alexander S.. 2019. “The Microbiome Wants What It Wants: Microbial Evolution Overtakes Experimental Host-Mediated Indirect Selection.” bioRxiv. 10.1101/706960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baba Tomoya, Ara Takeshi, Hasegawa Miki, Takai Yuki, Okumura Yoshiko, Baba Miki, Datsenko Kirill A., Tomita Masaru, Wanner Barry L., and Mori Hirotada. 2006. “Construction of Escherichia Coli K-12 in-Frame, Single-Gene Knockout Mutants: The Keio Collection.” Molecular Systems Biology 2 (February): 2006.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen Roeland L., Vismans Gilles, Yu Ke, Song Yang, de Jonge Ronnie, Burgman Wilco P., Burmølle Mette, Herschend Jakob, Bakker Peter A. H. M., and Pieterse Corné M. J.. 2018. “Disease-Induced Assemblage of a Plant-Beneficial Bacterial Consortium.” The ISME Journal 12 (6): 1496–1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein Hans C., and Carlson Ross P.. 2012. “Microbial Consortia Engineering for Cellular Factories: In Vitro to in Silico Systems.” Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 3 (December): e201210017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin Manuel, Karimi Battle, Mathieu Jérôme, and Lerch Thomas Z.. 2015. “Levels and Limits in Artificial Selection of Communities.” Ecology Letters 18 (10): 1040–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Chang-Yu, Osborne Melisa L., Bajic Djordje, and Sanchez Alvaro. 2020. “Artificially Selecting Bacterial Communities Using Propagule Strategies.” Dryad. 10.5061/dryad.2547d7wp4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CY, Vila JCC, Bender M, Mankowski MC, Li R, Bassette M, Borden J, et al. 2020. “Top-down Engineering of Complex Communities by Directed Evolution.” BioRxiv. 10.1101/2020.07.24.214775v2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes-Tolalpa Larisa, Jiménez Diego Javier, de Lima Brossi Maria Julia, Salles Joana Falcão, and van Elsas Jan Dirk. 2016. “Different Inocula Produce Distinctive Microbial Consortia with Similar Lignocellulose Degradation Capacity.” Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, May. 10.1007/s00253-016-7516-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doulcier Guilhem, Lambert Amaury, De Monte Silvia, and Rainey Paul B.. 2020. “Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics of Nested Darwinian Populations and the Emergence of Community-Level Heredity.” eLife, July, 53433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng Alexander, and Borenstein Elhanan. 2016. “An Algorithm for Designing Minimal Microbial Communities with Desired Metabolic Capacities.” Bioinformatics 32 (13): 2008–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2019. “Microbial Community Design: Methods, Applications, and Opportunities.” Current Opinion in Biotechnology 58 (August): 117–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalante Ana E., Rebolleda-Gómez María, Benítez Mariana, and Travisano Michael. 2015. “Ecological Perspectives on Synthetic Biology: Insights from Microbial Population Biology.” Frontiers in Microbiology 6 (February): 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraune Sebastian, and Bosch Thomas C. G.. 2010. “Why Bacteria Matter in Animal Development and Evolution.” BioEssays: News and Reviews in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology 32 (7): 571–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuwa Hidetsugu. 1954. “A New Method for Microdetermination of Amylase Activity by the Use of Amylose as the Substrate.” Journal of Biochemistry 41 (5): 583–603. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert ES, Walker AW, and Keasling JD. 2003. “A Constructed Microbial Consortium for Biodegradation of the Organophosphorus Insecticide Parathion.” Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 61 (1): 77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldford Joshua E., Lu Nanxi, Bajić Djordje, Estrela Sylvie, Tikhonov Mikhail, Sanchez-Gorostiaga Alicia, Segrè Daniel, Mehta Pankaj, and Sanchez Alvaro. 2018. “Emergent Simplicity in Microbial Community Assembly.” Science 361 (6401): 469–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman Robert P., and Brown Sam P.. 2009. “Making Sense of Microbial Consortia Using Ecology and Evolution.” Trends in Biotechnology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnight Charles J. 1990. “Experimental Studies of Community Evolution I: The Response to Selection at the Community Level.” Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution 44 (6): 1614–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2011. “Evolution in Metacommunities.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 366 (1569): 1401–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnight CJ 2000. “Heritability at the Ecosystem Level.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal Murali, and Gupta Alka. 2016. “Microbiome Selection Could Spur Next-Generation Plant Breeding Strategies.” Frontiers in Microbiology 7 (December): 1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould Alison L., Zhang Vivian, Lamberti Lisa, Jones Eric W., Obadia Benjamin, Korasidis Nikolaos, Gavryushkin Alex, Carlson Jean M., Beerenwinkel Niko, and Ludington William B.. 2018. “Microbiome Interactions Shape Host Fitness.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115 (51): E11951–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Xiaokan, and Boedicker James Q.. 2016. “The Contribution of High-Order Metabolic Interactions to the Global Activity of a Four-Species Microbial Community.” PLoS Computational Biology 12 (9): e1005079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington Kyle I., and Sanchez Alvaro. 2014. “Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics of Complex Social Strategies in Microbial Communities.” Communicative & Integrative Biology 7 (1): e28230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauert Christoph, Holmes Miranda, and Doebeli Michael. 2006. “Evolutionary Games and Population Dynamics: Maintenance of Cooperation in Public Goods Games.” Proceedings. Biological Sciences / The Royal Society 273 (1600): 2565–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauert Christoph, Wakano Joe Yuichiro, and Doebeli Michael. 2008. “Ecological Public Goods Games: Cooperation and Bifurcation.” Theoretical Population Biology 73 (2): 257–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Jie, Wei Zhong, Friman Ville-Petri, Gu Shao-Hua, Wang Xiao-Fang, Eisenhauer Nico, Yang Tian-Jie, et al. 2016. “Probiotic Diversity Enhances Rhizosphere Microbiome Function and Plant Disease Suppression.” mBio 7 (6). 10.1128/mBio.01790-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Microbiome Project Consortium. 2012. “Structure, Function and Diversity of the Healthy Human Microbiome.” Nature 486 (7402): 207–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaoka Takashi, and Ochi Kozo. 2011. “Scandium Stimulates the Production of Amylase and Bacilysin in Bacillus Subtilis.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology 77 (22): 8181–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jochum Michael D., McWilliams Kelsey L., Pierson Elizabeth A., and Jo Young-Ki. 2019. “Host-Mediated Microbiome Engineering (HMME) of Drought Tolerance in the Wheat Rhizosphere.” PloS One 14 (12): e0225933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jousset Alexandre, Eisenhauer Nico, Merker Monika, Mouquet Nicolas, and Scheu Stefan. 2016. “High Functional Diversity Stimulates Diversification in Experimental Microbial Communities.” Science Advances 2 (6): e1600124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim In Jung, Lee Hee Jin, Choi In-Geol, and Kim Kyoung Heon. 2014. “Synergistic Proteins for the Enhanced Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Cellulose by Cellulase.” Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 98 (20): 8469–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin Bruce R., and Kilmer William L.. 1974. “Interdemic Selection and the Evolution of Altruism: A Computer Simulation Study.” Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution 28 (4): 527–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin RC 1970. “The Units of Selection.” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 1 (1): 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Nanxi, Sanchez-Gorostiaga Alicia, Tikhonov Mikhail, and Sanchez Alvaro. 2018. “Cohesiveness in Microbial Community Coalescence.” bioRxiv. 10.1101/282723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes Rodrigo, Kruijt Marco, de Bruijn Irene, Dekkers Ester, van der Voort Menno, Schneider Johannes H. M., Piceno Yvette M., et al. 2011. “Deciphering the Rhizosphere Microbiome for Disease-Suppressive Bacteria.” Science 332 (6033): 1097–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickalide Harry, and Kuehn Seppe. 2019. “Higher-Order Interaction between Species Inhibits Bacterial Invasion of a Phototroph-Predator Microbial Community.” Cell Systems 9 (6): 521–33.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minty Jeremy J., Singer Marc E., Scholz Scott A., Bae Chang-Hoon, Ahn Jung-Ho, Foster Clifton E., Liao James C., and Lin Xiaoxia Nina. 2013. “Design and Characterization of Synthetic Fungal-Bacterial Consortia for Direct Production of Isobutanol from Cellulosic Biomass.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110 (36): 14592–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller UG, and Sachs JL. 2015. “Engineering Microbiomes to Improve Plant and Animal Health.” Trends in Microbiology 23 (10): 606–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller Ulrich G., Juenger Thomas E., Kardish Melissa R., Carlson Alexis L., Burns Kathleen, Smith Chad C., and De Marais David L.. 2016. “Artificial Microbiome-Selection to Engineer Microbiomes That Confer Salt-Tolerance to Plants.” bioRxiv. 10.1101/081521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panke-Buisse Kevin, Lee Stacey, and Kao-Kniffin Jenny. 2016. “Cultivated Sub-Populations of Soil Microbiomes Retain Early Flowering Plant Trait.” Microbial Ecology, September. 10.1007/s00248-016-0846-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panke-Buisse Kevin, Poole Angela C., Goodrich Julia K., Ley Ruth E., and Kao-Kniffin Jenny. 2015. “Selection on Soil Microbiomes Reveals Reproducible Impacts on Plant Function.” The ISME Journal 9 (4): 980–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn Alexandra. 2003. “Modelling Artificial Ecosystem Selection: A Preliminary Investigation.” In Advances in Artificial Life, 659–66. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- Penn Alexandra S., and Harvey Inman. 2004. “The Role of Non-Genetic Change in the Heritability, Variation and Response to Selection of Artificially Selected Ecosystems.” In , 352–57. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Piccardi Philippe, Vessman Björn, and Mitri Sara. 2019. “Toxicity Drives Facilitation between 4 Bacterial Species.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116 (32): 15979–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch Joseph, Kondev Jane, and Sanchez Alvaro. 2017. “Cooperators Trade off Ecological Resilience and Evolutionary Stability in Public Goods Games.” Journal of the Royal Society, Interface / the Royal Society 14 (127). 10.1098/rsif.2016.0967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raynaud Tiffany, Devers Marion, Spor Aymé, and Blouin Manuel. 2019. “Effect of the Reproduction Method in an Artificial Selection Experiment at the Community Level.” Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 7: 416. [Google Scholar]

- Regot Sergi, Macia Javier, Conde Núria, Furukawa Kentaro, Jimmy Kjellén Tom Peeters, Hohmann Stefan, de Nadal Eulàlia, Posas Francesc, and Solé Ricard. 2011. “Distributed Biological Computation with Multicellular Engineered Networks.” Nature 469 (7329): 207–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rillig Matthias C., Tsang Alia, and Roy Julien. 2016. “Microbial Community Coalescence for Microbiome Engineering.” Frontiers in Microbiology 7 (December): 1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Alvaro. 2019. “Defining Higher-Order Interactions in Synthetic Ecology: Lessons from Physics and Quantitative Genetics.” Cell Systems 9 (6): 519–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Alvaro, Vila Jean C. C., Chang Chang-Yu, Diaz-Colunga Juan, Estrela Sylvie, and Rebolleda-Gomez Maria. 2020. “Directed Evolution of Microbial Communities.” EcoevoRxiv, July. 10.32942/osf.io/gsz7j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Gorostiaga Alicia, Bajić Djordje, Osborne Melisa L., Poyatos Juan F., and Sanchez Alvaro. 2019. “High-Order Interactions Distort the Functional Landscape of Microbial Consortia.” PLoS Biology 17 (12): e3000550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhanam Rakesh, Luu Van Thi, Weinhold Arne, Goldberg Jay, Oh Youngjoo, and Baldwin Ian T.. 2015. “Native Root-Associated Bacteria Rescue a Plant from a Sudden-Wilt Disease That Emerged during Continuous Cropping.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (36): E5013–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senay Yitbarek, John Guittar, Knutie Sarah A., and Ogbunugafor C. Brandon. 2019. “Deconstructing Higher-Order Interactions in the Microbiota: A Theoretical Examination.” bioRxiv. 10.1101/647156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shade Ashley, Peter Hannes, Allison Steven D., Baho Didier L., Berga Mercè, Bürgmann Helmut, Huber David H., et al. 2012. “Fundamentals of Microbial Community Resistance and Resilience.” Frontiers in Microbiology 3 (December): 417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth Ravi U., Cabral Vitor, Chen Sway P., and Wang Harris H.. 2016. “Manipulating Bacterial Communities by in Situ Microbiome Engineering.” Trends in Genetics: TIG 32 (4): 189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shong Jasmine, Rafael Manuel Diaz Jimenez, and Collins Cynthia H.. 2012. “Towards Synthetic Microbial Consortia for Bioprocessing.” Current Opinion in Biotechnology 23 (5): 798–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. Maynard. 1964. “Group Selection and Kin Selection.” Nature 201 (4924): 1145–47. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Robert P., Tanouchi Yu, and You Lingchong. 2013. “Chapter 13 - Synthetic Microbial Consortia and Their Applications.” In Synthetic Biology, edited by Zhao Huimin, 243–58. Boston: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Paula Monteiro, and Pérola de Oliveira Magalhães. 2010. “Application of Microbial α-Amylase in Industry - A Review.” Brazilian Journal of Microbiology: [publication of the Brazilian Society for Microbiology] 41 (4): 850–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson W, Arendt J, and Wilson DS. 2000. “Artificial Selection of Microbial Ecosystems for 3-Chloroaniline Biodegradation.” Environmental Microbiology 2 (5): 564–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson W, Wilson DS, and Elias R. 2000. “Artificial Ecosystem Selection.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97 (16): 9110–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traulsen Arne, and Nowak Martin A.. 2006. “Evolution of Cooperation by Multilevel Selection.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (29): 10952–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade Michael J. 1978. “A Critical Review of the Models of Group Selection.” The Quarterly Review of Biology 53 (2): 101–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wade MJ 1976. “Group Selections among Laboratory Populations of Tribolium.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 73 (12): 4604–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang En-Xu, Ding Ming-Zhu, Ma Qian, Dong Xiu-Tao, and Yuan Ying-Jin. 2016. “Reorganization of a Synthetic Microbial Consortium for One-Step Vitamin C Fermentation.” Microbial Cell Factories 15 (January): 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Zhong, Yang Tianjie, Friman Ville-Petri, Xu Yangchun, Shen Qirong, and Jousset Alexandre. 2015. “Trophic Network Architecture of Root-Associated Bacterial Communities Determines Pathogen Invasion and Plant Health.” Nature Communications 6 (September): 8413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West Stuart A., Griffin Ashleigh S., Gardner Andy, and Diggle Stephen P.. 2006. “Social Evolution Theory for Microorganisms.” Nature Reviews. Microbiology 4 (8): 597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams Hywel T. P., and Lenton Timothy M.. 2007a. “Artificial Ecosystem Selection for Evolutionary Optimisation.” In Advances in Artificial Life, 93–102. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2007b. “Artificial Selection of Simulated Microbial Ecosystems.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (21): 8918–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson David Sloan. 1992. “Complex Interactions in Metacommunities, with Implications for Biodiversity and Higher Levels of Selection.” Ecology 73 (6): 1984–2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DS 1975. “A Theory of Group Selection.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 72 (1): 143–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Li, Yuan Alex E., and Shou Wenying. 2019. “Simulations Reveal Challenges to Artificial Community Selection and Possible Strategies for Success.” PLoS Biology 17 (6): e3000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Qiang-Sheng, Yan Yu-Si, and Feng Jia-Xun. 2016. “Efficient Hydrolysis of Raw Starch and Ethanol Fermentation: A Novel Raw Starch-Digesting Glucoamylase from Penicillium Oxalicum.” Biotechnology for Biofuels 9 (October): 216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Min, Zhang Kun-Di, Zhang Pei-Yu, Zhou Xia, Ma Xiao-Qing, and Li Fu-Li. 2016. “Synergistic Cellulose Hydrolysis Dominated by a Multi-Modular Processive Endoglucanase from Clostridium Cellulosi.” Frontiers in Microbiology 7 (June): 932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Ogawa N, Fujii T, and Tsushima S. 2009. “Enhanced Biofilm Formation and 3-Chlorobenzoate Degrading Activity by the Bacterial Consortium of Burkholderia Sp. NK8 and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa PAO1.” Journal of Applied Microbiology 106 (3): 790–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanaroli Giulio, Di Toro Sara, Todaro Daniela, Varese Giovanna C., Bertolotto Antonio, and Fava Fabio. 2010. “Characterization of Two Diesel Fuel Degrading Microbial Consortia Enriched from a Non Acclimated, Complex Source of Microorganisms.” Microbial Cell Factories 9 (February): 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.