Abstract

Objectives: Data indicate that some developmentally and behaviorally based early intervention programs can lead to a range of improvements in children with autism spectrum disorder. However, many such programs call for a fairly intensive amount of intervention. The objective of this preliminary study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a low-intensity therapist delivered intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder.

Methods: The study evaluated the outcomes of 3 hours per week of therapist-delivered early start Denver model intervention (ESDM) over a 12-week period for four preschool-aged boys with autism spectrum disorder. The effects of intervention on communication, imitation, and engagement were evaluated using a non-concurrent multiple probe across participants design.

Results: Following the intervention, all four children showed increases in imitation, engagement, and either functional utterances or intentional vocalizations. These results were maintained after 4 weeks and mostly generalized to each child’s mother.

Conclusion: These preliminary results suggest that low-intensity therapist delivered ESDM intervention may be of some benefit to children with autism spectrum disorder.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, early start Denver model, low-intensity therapy, preschool children

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a pervasive developmental disorder characterized by deficits in social communication and the presence of restricted and repetitive behaviors, interests, and activities (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Recent developments in identification techniques mean that many children can be reliably diagnosed with ASD before 2 years of age (Barbaro and Dissanayake 2010, Chawarska et al. 2007). The ability to identify children with, or at risk for, ASD, when they are very young means that intervention can also begin earlier (Dawson and Bernier 2013). Indeed, research suggests that young children with ASD may respond particularly well to interventions aimed at developing their social and communication skills and more generally improving cognitive and adaptive behavior functioning (Bibby et al. 2002, Granpeesheh et al. 2009, Harris and Handleman 2000). Contemporary early intervention programs for children with ASD make use of developmental and naturalistic behavioral principles and teaching techniques (Schreibman et al. 2015). A key feature of such naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions (NDBIs) is that they employ a range of empirically validated instructional procedures based on the principles of applied behavior analysis with a developmental/relationship-focused approach.

The early start Denver model (ESDM) is a NDBI with an emerging evidence base supporting its use as an early intervention approach for children with, or at risk for, ASD (Rogers and Dawson 2010). Indeed, more than 20 studies have been conducted evaluating the effectiveness of this approach, most of which have reported positive results (see Baril and Humphreys 2017 and Waddington et al. 2016, for reviews). The ESDM is designed for children between 12 and 60 months of age. It is based primarily upon two pre-existing models of intervention for children with ASD, that is pivotal response treatment (PRT) and the Denver model. In line with PRT, the ESDM incorporates procedures to increase children’s motivation to learn, such as incorporating opportunities for child choice, making use of natural reinforcers, and the application of systematic instructional procedures (Koegel et al. 2016, Rogers and Dawson 2010). Similar to the Denver Model, the ESDM uses techniques that are intended to promote positive relationships between therapist and child, and to establish social interactions as conditioned/natural reinforcers (Dawson 2008, Rogers et al. 1986). The ESDM is a comprehensive intervention, in that it targets skills across a wide range of developmental domains, including social skills, communication, imitation, and cognition (Odom et al. 2010). Refer to Rogers and Dawson (2010) for an in-depth description of the ESDM procedures.

When evaluating the evidence base for early intervention approaches such as the ESDM, one should consider both the efficacy and effectiveness research (Singal et al. 2014). In efficacy research, the intervention is implemented under controlled conditions. This includes interventions delivered in a clinical setting by specially trained research staff. In effectiveness research, the intervention is delivered under more ‘real-world’ conditions. For example, interventions delivered by parents or teachers in the home or classroom setting can be classified as effectiveness research.

Several studies have provided empirical evidence to support the use of ESDM when it is implemented for at least 15 hours per week either during one-on-one sessions or in small-group contexts (Dawson et al. 2010, Vivanti et al. 2014). For example, in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted by Dawson et al. (2010), the 24 children in the ESDM intervention group received an average of 15.2 hours per week of therapist-delivered intervention and 16.3 hours per week of parent-delivered intervention over a 2-year period. After 2 years, these children had significantly greater improvements on measures of cognition and adaptive behavior than the 24 children in the ‘treatment-as-usual’ group. However, there was no significant difference between the two groups on a measure of autism symptom severity or with respect to severity of behavior. A 2-year follow-up reported that the ESDM group maintained their improvement on measures of adaptive behavior and cognition and also showed improvement with respect to symptom severity (Estes et al. 2015).

The results of the intensive ESDM research are promising (Dawson et al. 2010, Estes et al. 2015, Vivanti et al. 2014). However, it is possible that, in some contexts, families might not be able to access or afford an intensive 2-year early intervention program. In many countries, including Italy, Germany, New Zealand, and parts of the United States, this type of early intervention is not funded by the government and obtaining private therapy is often hindered by a lack of qualified professionals (Colombi et al. 2016, Freitag et al. 2012, Kasilingam et al. 2019, Vismara et al. 2009). Thus, professionals are often only able to provide therapy for a few hours a week. Therefore, it seems essential to identify effective methods of delivering early intervention that require relatively few hours of professional input per week.

Researchers have evaluated two different low-intensity approaches to delivering ESDM intervention. These are parent coaching and an approach in which a trained therapist delivers the intervention for fewer than 6 hours per week. The results of research that has evaluated ESDM delivery via parent coaching are mixed. For example, Rogers et al. (2012) used an RCT design to evaluate the efficacy of a 12-week ESDM parent coaching program. At the end of the 12 weeks, they found no significant difference in cognitive or language abilities between toddlers who received the ESDM parent coaching intervention and those in the control group, although parents in the ESDM group reported significantly lower stress (Estes et al. 2014) In contrast, a more recent study by Zhou et al. (2018) found that children whose parents participated in a 26-week ESDM parent coaching program showed greater improvements in expressive and receptive language, and social communication, than children receiving ‘treatment-as-usual’. Further, parents in this program also had a significantly greater reduction in their reported levels of stress.

Two Italian studies have evaluated lower-intensity therapist-delivered versions of the ESDM (Colombi et al. 2016, Devescovi et al. 2016). Colombi et al. (2016) compared the effectiveness of 6 hours per week of clinic-based ESDM therapy for 22 young children with ASD with a ‘treatment-as-usual’ condition that involved 70 children. After 6 months, children in the ESDM therapy group showed significantly greater improvements on a measure of intelligence than did children in the ‘treatment-as-usual’ group, but there were no significant differences between groups on a measure of adaptive behavior functioning. Devescovi et al. (2016) provided 3 hours per week of clinic-based ESDM for an average of 15 months to 21 toddlers at risk for ASD. They reported significant increases in cognitive and language skills, but no significant reduction in autism symptom severity. The results of these two studies suggest that a low-intensity, therapist-delivered version of the ESDM could be of some benefit to young children with or at risk for ASD.

Overall, the studies evaluating ESDM parent coaching have reported mixed results, while the results from studies involving low-intensity, therapist-delivered ESDM have consistently reported improvements in at least some child outcomes. This could be because therapists may implement the ESDM procedures with higher fidelity than parents. Therefore, the aim of this pilot study was to evaluate a low-intensity, home-based, direct ESDM therapy approach on outcomes for four young boys with ASD. These children each received 3 hours of intervention per week for 12 weeks, which is in line with the maximum amount of publically funded intervention that is available to families in New Zealand (Kasilingam et al. 2019). A secondary aim was to assess generalization from the therapist to each child’s mother. This study aimed to extend upon the previous ESDM literature in several ways:

The duration of this study was shorter than that used in the Colombi et al. (2016) and Devescovi et al. (2016) studies. It is possible that if an even shorter duration of low-intensity therapy could be of benefit to the children. If so, this might enable more children to access this intervention.

The study took place in the home rather than a clinic setting. This fits more with the model of early intervention delivery in New Zealand. Home-based therapy may also be more convenient families (Sweet and Appelbaum 2004), and, given that many children with ASD have difficulty generalizing new skills, it may be more appropriate to teach skills in the environment where the children live (Koegel et al. 2016).

Finally, this study directly assessed the degree of generalization of skills learned with the therapist to each child’s mother. This is because, arguably, skills that a young child develops with a therapist, but not with a parent, may be of limited benefit in the long-term.

Methods

Ethical considerations

The relevant University Ethics Committee approved the study. Parents gave informed consent for their child to participate because the children were minors and unable to provide informed consent.

Participants

Four children and their parents were recruited for this study. The parents of two of the children were referred to the therapist (first author) by the local government District Health Board. The other two parents made contact with the primary therapist after attending an ESDM introductory workshop. These families met the following inclusion criteria: (a) the child was under the age of 5 years (60 months) at the start of the study; (b) the child had a confirmed clinical diagnosis of ASD by an independent agency; (c) the child did not have another serious or specific medical, genetic, neurological, or sensory condition (e.g. Down syndrome, fragile X), and (d) the child was not receiving intensive (20 or more hours per week of) specialized early intervention of any type at any time during the study.

All four children were diagnosed by an independent multidisciplinary team, who use the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule – Second Edition (ADOS-2; Lord et al. 2012) as part of the diagnostic process. In addition, we assessed each child using the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ; Rutter et al. 2003) and the second edition of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Vineland-II; Sparrow et al. 2005). The SCQ and Vineland-II were administered by interviewing the parents at the start of the study. Table 1 provides a summary of each child’s age, ethnicity, and assessment results.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics, Vineland-II domain standard scores, and Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) results

| Charlie | Alan | Chris | Jeevan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at start of study | 2:3 | 4:3 | 3:2 | 3:8 |

| Age at diagnosis | 2:2 | 2:11 | 2:11 | 3:1 |

| Ethnicity | NZ European | NZ European | NZ European | Indian |

| Vineland-II domain | ||||

| Standard scores | ||||

| Communication | 45 | 52 | 81 | 69 |

| Daily living | 47 | 66 | 100 | 62 |

| Socialization | 68 | 63 | 68 | 61 |

| Motor skills | 93 | 72 | 64 | 78 |

| Maladaptive index | Elevated | Average | Elevated | Clin. sig. |

| Internalizing | Clin. sig. | Average | Clin. sig. | Clin. sig. |

| Externalizing | Average | Average | Average | Average |

| SCQ | 23 | 23 | 17 | 25 |

| Risk of ASD | Risk of ASD | Risk of ASD | Risk of ASD | |

| Additional treatment | EI Centre | EI Centre | Food Int. Hydrotherapy | EI Centre |

NZ: New Zealand; Clin. sig.: clinically significant; EI: early intervention.

Charlie attended playgroup every weekday morning and had one weekly session of early intervention involving services from a speech language therapist, an early intervention teacher, a music therapist, and a physiotherapist. Alan went to kindergarten for 4 days a week and attended the same early intervention center as Charlie. Chris attended in home childcare three times a week and was also participating in a food intervention and hydrotherapy. Jeevan attended kindergarten every weekday afternoon and began to attend the same early intervention center as Charlie and Alan on the 10th week of intervention. None of the parents were receiving any parent training/coaching over the duration of the study.

Setting and personnel

Sessions occurred in each child’s home. Specifically, for Jeevan and Chris, all sessions occurred in the living room. For Charlie, all sessions occurred in a play room. For Alan, sessions occurred in his living room during most phases of the study. However, some intervention sessions for Alan occurred outside in his yard because he appeared to be particularly motivated by the swings and the trampoline.

Parents and siblings were able to watch the therapist-led sessions, but were encouraged to limit interaction with the participating child during this time. Chris, Jeevan, and Alan’s mothers often observed parts of the therapist-led session; however, Charlie’s mother never directly observed the sessions. For this reason, the therapist gave Charlie’s mother several videos of the therapy sessions to observe. During parent-led sessions both before and after the intervention, parents were instructed to play with their child as they normally would for 10 min. During the intervention, parents did not receive any explicit coaching/training in the ESDM techniques.

The therapist (first author) had several years of experience working with children with ASD and she was a certified ESDM therapist. She had completed the introductory and advanced ESDM workshops and had obtained 80% correct fidelity on the ESDM teaching fidelity rating system (Rogers and Dawson 2010) as determined by an independent rating of two, 30-min videotapes by an Australian ESDM trainer.

Materials

During all sessions (including the generalization probes), the children were able to play with any toy that was already in the room. In addition, the therapist brought a large transparent plastic box containing a number of specific ‘therapy toys’ for each session based on the list provided in the ESDM therapists’ manual (Rogers and Dawson 2010).

Experimental design

The effects of the intervention were evaluated using a non-concurrent multiple probe across participants’ design (Kennedy 2005). A single subject design was selected because there were several aspects of the ESDM delivery approach (brief duration, home-based) which have not previously been evaluated. Therefore, the primary aim of this preliminary study was to conduct an in-depth analysis of effect of this novel approach on outcomes for four children. If this novel approach was associated with positive results in this small scale, then there would seem to be some potential value in larger controlled studies. In line with the requirements of the non-concurrent multiple probe across participants design, the baseline phase for each child started when the child was recruited and because the children were recruited at different times, each baseline phase started at a different point. Each child participated in the following sequence of phases: baseline, intervention, generalization, and follow-up.

Procedures

Baseline

One session occurred per week for each child. At the start of each session, the therapist started the video recorder and then placed the box of toys in front of the child. The therapist waited 10 s for the child to select a toy. If the child did not chose a toy, then the therapist placed a selection of toys from the box in front of the child. If the child still did not select a toy within 10 s, then the therapist selected a toy and probed an imitation skill or utterance before handing the toy to the child. The session continued for 10-min from the time the child selected a toy. When the opportunity arose, the therapist interspersed 10 naturalistic imitation probes (e.g. banging on a drum and looking at the child expectantly) and 10 naturalistic probes for functional utterances (e.g. holding up a car and asking What’s this?). No other response prompting procedures were used at any time during baseline. The therapist responded in an appropriate and friendly manner to all social initiations from the child. Parents and siblings were instructed not to interact with the child during the 10-min period.

Baseline generalization probe

Each child’s mother participated in the generalization probe that took place during the baseline phase for Alan, Chris, and Jeevan. This probe occurred during the 2nd week of intervention for Charlie due to difficulties with scheduling the probe during baseline. For the probe, each mother was instructed to ‘play with your child as you normally would.’ The box of toys used in each baseline session with the therapist was available in the room and parents were told that they could use those toys if they wished. Once the child was settled into play with his mother, the therapist began filming the 10-min session. The therapist did not make any comments nor give any feedback about the child’s play or the mother’s interaction with the child during or after the filming.

Intervention

During the first intervention session, the therapist played in a naturalistic way with the child for approximately 1 hr. A second therapist, who had completed the ESDM advanced workshop but was not certified, then noted on the ESDM curriculum checklist (Rogers and Dawson 2010) whether or not the child displayed a range of developmental skills and would instruct the therapist on further skills to probe during the play. Based on this first session, and in consultation with the parents, two to three goals were selected for each child from each of nine developmental domains (i.e. receptive communication, expressive communication, social skills, imitation, cognition, play, fine motor, gross motor, and behavior). Chris was the only child who was at a developmental level to have goals in the joint attention domain.

During the remaining sessions, the therapist implemented the therapy according to the principles of the ESDM, as detailed in the intervention manual (Rogers and Dawson 2010). Specifically, the therapist implemented the following ESDM fidelity items: (a) management of child attention; (b) behavioral teaching; (c) modulation of child affect and arousal; (d) management of unwanted behaviors; (e) quality of dyadic engagement; (f) optimization of child motivation; (g) positive affect; (h) sensitivity and responsivity; (i) use of multiple and varied communicative functions; (j) appropriateness of language; (k) use of joint activity routines; and (l) smooth transitions. Sessions were terminated after 1 hr or when the therapist determined from the child’s behavior that he no longer wanted to continue. For example, during the first couple of weeks of intervention, Alan would leave the therapy area after about 40-min of intervention. A 10-min sample was collected during each of the first 2 of the 3 weekly sessions and these samples were then coded. The starting point for coding was the activity which began closest to the 20-min mark of the 1-hr session.

During intervention, Alan showed challenging behavior associated with requesting access to cartoons at the start of many sessions. It was found that conducting the beginning of sessions outside caused a reduction in this challenging behavior. For this reason, an additional phase involving probes in the living room was conducted to ensure consistency between baseline and intervention. During this phase, Alan was required to begin the session in the living room before being allowed to go outside. Filming took place in the first 10-min of the session, rather than after 20-min of play.

Post-intervention generalization

These probes occurred 1 week after the final intervention session for each child. Procedures were identical to the baseline generalization probe, except that three 10-min videotapes (i.e. three probes) were taken during a single week.

Follow-up

Follow-up took place 4 weeks after the last intervention session for each child. These sessions were conducted by the therapist using the same procedures as intervention. These sessions lasted 10-min and the entire session was videotaped.

Dependent variables

Data on each dependent variable were collected by the first author from 10-min videotapes that were made during each baseline, generalization, and follow-up session, and on two of every three intervention sessions. Four dependent variables were defined: imitation, functional utterance, intentional vocalization, and engagement.

Each 10 min of video was divided into 60, 10-s intervals. Partial interval recording (Kennedy 2005) was used to record whether or not any instances of imitation, functional utterances, or intentional vocalizations (Alan only) had occurred during each 10-s interval. Whole-interval recording was used to measure whether each child showed behaviors indicating engagement for the entire 10 s of each interval (Kennedy 2005).

Imitation

Performing an action with or without an object, or producing a vocalization, within 10 s of an adult model and without prompting from an adult, such as the adult saying Do this or physically helping the child to perform the action.

Functional utterance

Any utterance by the child that: (a) occurred without adult prompting or modeling of the utterance within 10 s of its occurrence, (b) was contextually related to the interaction, for example, not unrelated speech, not repetitions of the child’s own speech, and not repetitions of adult’s prior speech, and (c) contained a phonetically and semantically correct approximation of the word or word combination (e.g. not saying horse when labeling a cow or saying ‘ooh’ to request a ball).

Intentional vocalization

Any utterance by the child that: (a) occurred without adult prompting or modeling of the vocalization, (b) was related to the interaction, for example, not unrelated speech, stereotypy, or echolalia, (c) did not contain a phonetically correct approximation of the word or word combination, and (d) did not consist of any whining, screaming, crying, or laughing. This measure was only recorded for Alan, because he was the only child for whom it was deemed to be developmentally appropriate. Specifically, he had an ESDM expressive language goal related to increasing his use of intentional vocalizations rather than functional utterances. The remaining three children had ESDM expressive language goals related to the use of functional utterances only.

Engagement

Engagement with therapist (or parent during generalization) was defined as any clear indication that the child was attending to the therapist’s face, voice, and actions, as well as any instances of the child showing social initiation. More specifically, this dependent measure was recorded when the child was observed to be: (a) orientated towards the therapist, that is facing the therapist; (b) smiling and/or laughing in response to the therapist’s action; (c) looking in the direction that the therapist was pointing/indicating; (d) giving, sharing, or showing objects to the therapist; (e) imitating the therapist’s actions; (f) taking turns with the therapist; (g) following directions given by the therapist; (h) communicating with the therapist through words, vocalizations, and/or gestures; and/or (i) continuing or elaborating on the therapist’s play actions.

Data analysis

Visual analysis of the graphs was used to determine changes in each child outcome variable (Kennedy 2005). Specifically, the changes in trend, level, and variability from baseline to intervention were described. The non-overlap of all pairs (NAP) statistic was also calculated to determine the effect size of improvements from baseline to intervention and baseline to follow-up for each primary outcome measure (Parker and Vannest 2009). The NAP is calculated by comparing each data point in baseline with each data point in intervention and noting whether the intervention or follow-up point overlaps (overlapping pair) does not overlap (non-overlapping pair) or ties (tied pair) with the baseline data point. The number of non-overlapping pairs is then divided by the total number of pairs to give an outcome between 0 (complete overlap) and 1.0 (no overlap). According to Parker and Vannest (2009), NAP scores between 0 and 0.65 indicate ‘weak effects,’ scores between 0.66 and 0.92 indicate ‘medium effects,’ and scores between 0.92 and 1.0 indicate ‘strong effects.’ It is important to note that NAP is a measure of the degree of overlap, rather than the size of the increase between baseline and treatment.

Interobserver agreement

Interobserver agreement (IOA) was assessed by having an independent observer (postgraduate student, who did not implement any of the therapy) collect data on the four dependent variables during 29 to 100% of the 10-min videos for each variable, each of the four children, and across all phases of the study. The observer was not blind to intervention phase. The first author taught the independent observer how to use the data collection sheets and ensured that she understood the operational definitions of each dependent variable. The observer then practiced coding a videotape of each of the children and discussed any issues that arose with the therapist, who directed her to the relevant sections of the operational definitions. These practice videotapes were not included in the overall IOA. The overall percentage of agreement for each session was calculated using the formula: Agreements/(Agreements + Disagreements) × 100%. Mean (standard deviation and range of) IOA was 91% (SD = 5.7; range = 73–100%) for imitation, 91% (SD = 7.6; range = 73–100%) for functional utterances, 84% (SD = 6.8; range = 77–98%) for intentional vocalizations, and 83% (SD = 9.3; range = 60–100%) for engagement. During the 10th intervention session for Jeevan and the 11th intervention session for Charlie, IOA was 68 and 60%, respectively, and IOA was at or above 73% in all other instances. It is hypothesized that IOA was particularly low in these sessions due to disagreement over whether the child was attending to the therapist and the toy, or just to the toy.

Procedural integrity

During the baseline and generalization phases, procedural integrity (PI) was assessed using a checklist that was completed by the same independent observer who conducted the IOA check (see Appendix G). During these phases, the checklist was completed for 30–50% of sessions for each child. The checklist described each step of the procedures during that phase, for example ‘the session lasted ten minutes from the child taking a toy’ and ‘therapist responded appropriately to any child attempts to initiate play or interaction.’ The percentage of PI was calculated using the formula: steps correct/total steps × 100%. Mean (and range of) PI during these phases was 99% (92–100%).

The therapist’s ongoing ESDM fidelity/PI during intervention and follow-up was evaluated by the independent observer using a modified version of the ESDM teaching fidelity rating system (Rogers and Dawson 2010). Specifically, it was rated using an 18-item checklist based on the 13 ESDM fidelity categories. Each item was rated on a Likert-type scale from 0, which indicated that the parent never used that specific technique, to 4, which indicated that the parent consistently used that specific technique. The fidelity sheet was modified in an attempt to focus the observer on the key elements of each fidelity item, and to reduce coding time. This measure can be obtained from the first author. This measure was completed for 25–29% of intervention sessions for each child. Mean (and range of) PI during these phases was 92% (range = 87–100%).

Results

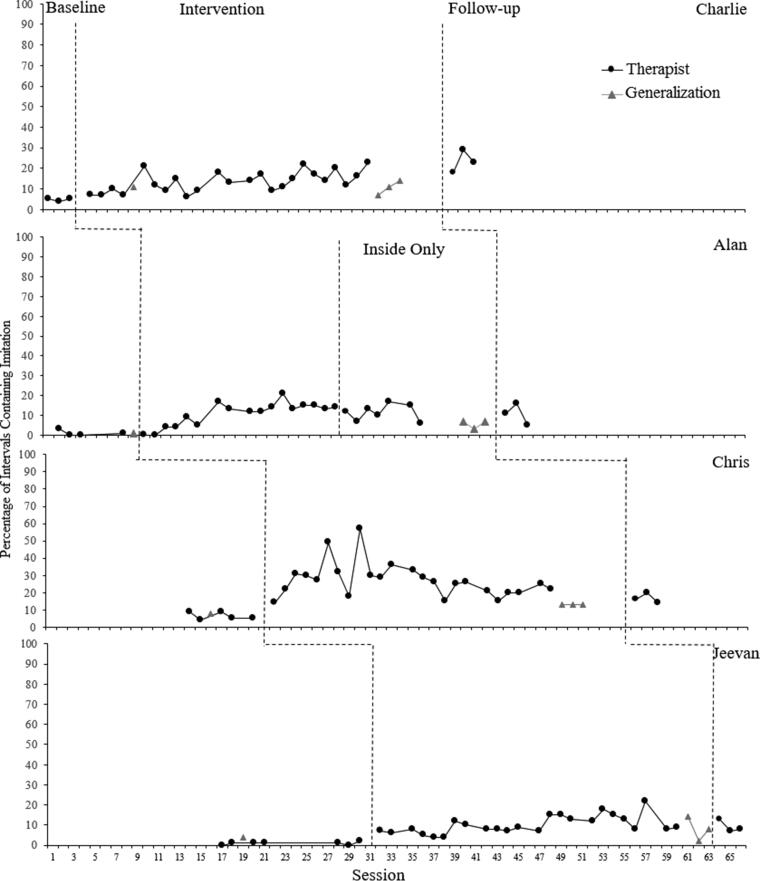

Imitation

Figure 1 shows the percentage of intervals containing independent (unprompted) instances of imitation for each child during each 10-min play sample. The mean percentage of intervals containing imitation for each child is presented below. For Charlie, imitation increased from 7.8% in baseline to 20.5% in intervention (NAP = 1.0) and 30.4% at follow-up (NAP = 1.0). During intervention, there was an immediate increase, a slight positive trend, and minimal variability. For Alan, imitation increased from 1.7% in baseline to 17.3% in intervention (NAP = 0.94) and 15.6% at follow-up (NAP = 1.0). During intervention, there was a delayed increase, minimal variability, and an initial positive trend which became flat from the 7th data point. For Chris, imitation increased from 11% in baseline to 38.5% in intervention (NAP = 1.0) and 27.7% at follow-up (NAP = 1.0). There was an immediate increase during intervention and a variable positive trend for the first nine data points which was followed by a slight negative trend with minimal variability. For Jeevan, imitation increased from 1.4% in baseline to 15.5% in both intervention and follow-up (NAP = 1.0). The was a small immediate increase in Jeevan’s imitation during intervention, with a positive trend and minimal variability. For all children, imitation with their mothers increased from the baseline generalization probe to the post-intervention generalization phase. For Charlie this increased from 15 to 16.7%, for Alan this increased from 1.7 to 8.9%, for Chris this increased from 13.3 to 20.5%, and for Jeevan this increased from 5 to 14.4%.

Figure 1.

Percentage of 10-s intervals containing at least one independent (unprompted) instance of imitation per 10-min play sample for each child across phases

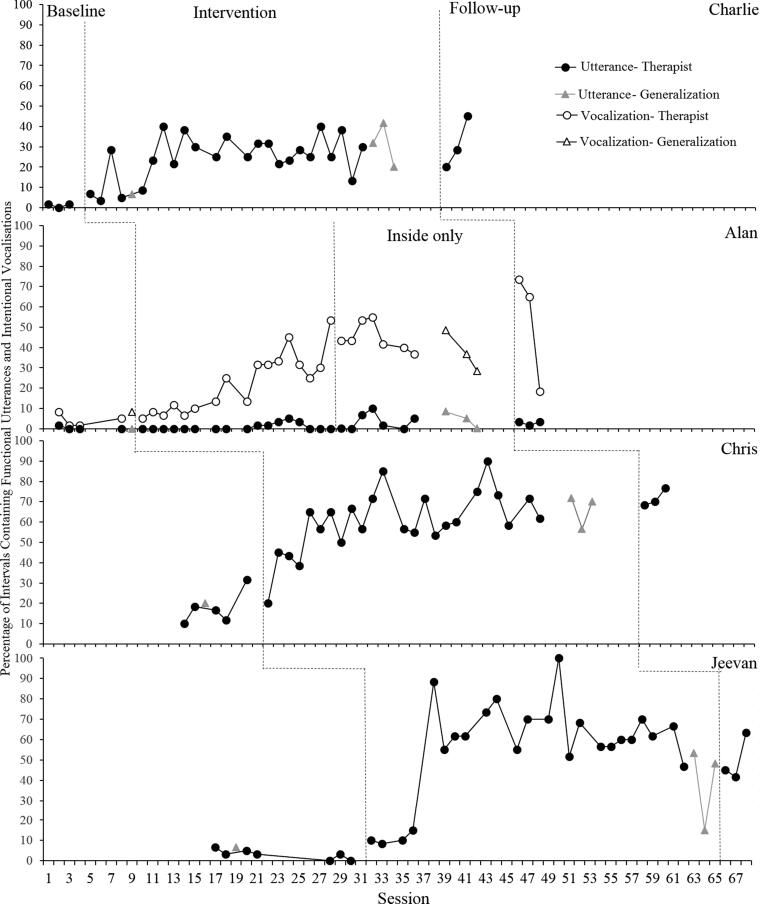

Functional utterances/intentional vocalizations

Figure 2 shows the percentage of 10-s intervals containing independent (unprompted) functional utterances and intentional vocalizations (Alan only) for each child during each 10-min play sample. The mean percentage of intervals containing functional utterances and intentional vocalizations for each child is presented below. For Charlie, functional utterances increased from 1.1% in baseline to 24.9% in intervention (NAP = 1.0) and 31.1% at follow-up (NAP = 1.0). There was a small immediate increase during intervention, moderate variability, and a positive trend for the first seven data points, which then became flat. For Alan, functional utterances increased slightly from 0.4% in baseline to 1.6% in intervention (NAP = 0.59) and 2.8% at follow-up (NAP = 0.96). In intervention there was no increase, a relatively flat trend, and minimal variability. For Alan, intentional vocalizations increased from 4.2% in baseline to 29% in intervention (NAP = 0.96) and 52.2% at follow-up (NAP = 1.0). There was an increase in intervention with a positive trend and moderate variability. The trend was flat with moderate variability during the ‘inside only’ phase. For Chris, functional utterances increased from 17.7% in baseline to 60.3% in intervention (NAP = 0.99) and 71.7% at follow-up (NAP = 1.0). There was a delayed increase in intervention, moderate variability, and a positive trend for the first 12 data points, which then became flat. For Jeevan, functional utterances increased from 3.1% in baseline to 56.5% in intervention (NAP = 1.0) and 50% at follow-up (NAP = 1.0). There was a small immediate increase in intervention, and the trend was flat for the first four points, followed by a large increase, and then flat and moderately variable for the rest of the phase. For all children, functional utterances with their mothers increased from the baseline generalization probe to the post-intervention generalization phase. For Charlie, this increased from 6.7 to 31.1%, for Alan this increased from 0 to 4.4%, for Chris this increased from 20 to 66.1%, and for Jeevan this increased from 6.7% to 38.9%. Intentional vocalizations with Alan’s mother also increased from 8.3% during the generalization probe to a mean of 37.7% during the post-intervention generalization phase.

Figure 2.

Percentage of 10-s intervals containing functional utterances and intentional vocalizations per 10-min play sample for each child across phases

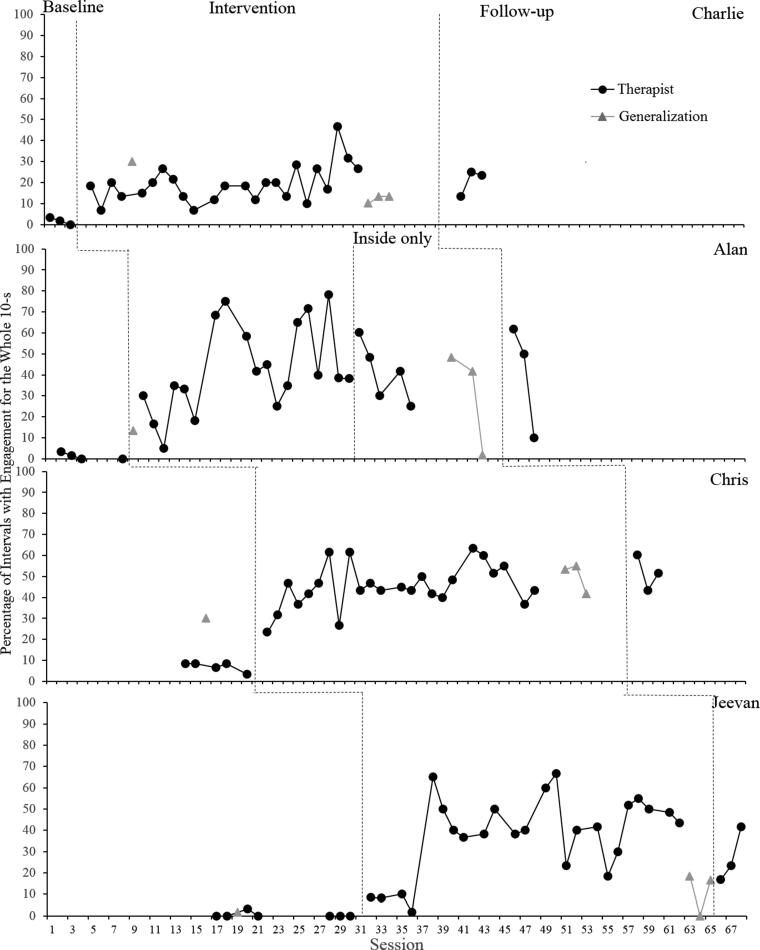

Engagement

Figure 3 shows the percentage of 10-s intervals in which the child was engaged for the entire interval for each 10-min play sample. The mean percentage of intervals containing engagement for each child is presented below. For Charlie, full engagement increased from 1.7% in baseline to 19.2% in intervention (NAP = 1.0) and 20.6% at follow-up (NAP = 1.0). There was an immediate increase in intervention, moderate variability, and a slight positive trend. For Alan, full engagement increased from 1.7% in baseline to 42.6% in intervention (NAP = 1.0) and 20.6% at follow-up (NAP = 1.0). There was an immediate increase in intervention, high variability, and a generally positive trend. There was a moderately variable, decreasing trend during the inside only phase. For Chris, full engagement increased from 7% in baseline to 37.6% in intervention (NAP = 1.0) and 51.6% at follow-up (NAP = 1.0). For Jeevan, full engagement increased from 0.5% in baseline to 31.8% in intervention (NAP = 0.99) and 27.2% at follow-up (NAP = 1.0). There was a small immediate increase in intervention, and the trend was flat for the first four data points, followed by a large increase, and then flat and highly variable for the rest of the phase. For Alan, Chris, and Jeevan, full engagement with their mothers increased from the baseline generalization probe to the post-intervention generalization phase. For Alan, this increased from 13.3 to 40.6%, for Chris this increased from 30 to 50%, and for Jeevan this increased from 1.7 to 11.6%. Charlie’s engagement with his mother decreased from 30% of intervals in the generalization probe at the start of intervention to a mean of 12.2% of intervals in the post-intervention generalization probe.

Figure 3.

Percentage of 10-s intervals with full engagement per 10-min play sample for each child across phases

Discussion

The results of this preliminary study suggest that a low intensity, therapist-delivered trial of the ESDM was associated with increased engagement and imitation among four preschool children who received the 12-week program. In addition, three of the four children (Charlie, Chris, and Jeevan) appeared to have shown an increase in their use of functional utterances. The increase in functional utterances for Alan was more modest, but he did appear to show an increase in intentional vocalizations during the intervention. All of these recorded improvements remained at levels above baseline 4 weeks after the intervention had finished. These apparent positive intervention effects also seemed to have generalized to some degree to play sessions delivered by the children’s mothers.

Overall, these results suggest that the current intervention led to some improvements for the children who participated. This is in line with previous studies investigating other low-intensity versions of the ESDM and other types of autism-specific early intervention programs, which also reported generally positive results (Colombi et al. 2016, Devescovi et al. 2016, Eldevik et al. 2006, Peters-Scheffer et al. 2013). However, it is not possible to directly compare the current results with these studies because of differences in the respective outcome measures.

Given that each of the children appeared to have showed some increase with respect to imitation, functional utterances/vocalizations, and engagement, this suggests that it may be possible to successfully target more than one behavior even in a relatively low-intensity version of the ESDM. More research is needed into the relative improvement in child outcomes following more comprehensive interventions such as ESDM compared to interventions that target fewer specific skills, such as interventions focused on increasing imitation (Ingersoll et al. 2007, Ingersoll and Schreibman 2006), joint attention, and/or symbolic play (Kasari et al. 2006).

A study connected to the current intervention evaluated the parents’ perceptions of this low-intensity direct therapy approach (Ogilvie and McCrudden 2017). The results of that separate social validity study indicated that all four of the parents found the ESDM therapy to be highly beneficial in terms of its outcomes for their children. This suggests that the apparent improvements in the child dependent variables were perceived by the parents of these children to be of some benefit to the child. However, as the changes in the child dependent variables that were targeted in this study were not considered in relation to the abilities that would be seen in typically developing children of the same age, it is not possible to draw conclusions about the clinical significance of these improvements.

In this study, intervention only lasted for 12 weeks, whereas in previous research, the low-intensity therapist-delivered intervention lasted from 6 months (Colombi et al. 2016) to 2 years (Eldevik et al. 2006, Peters-Scheffer et al. 2013). Therefore, the fact that each of the children appeared to show some increase in most of the dependent variables with intervention, and that these changes were observed to have been maintained above baseline levels 1 month later, suggests that this short duration low-intensity approach may also be somewhat beneficial in promoting positive changes for young children with ASD. If replicated on a larger scale, this could be an important finding because, in areas where funding and resources are limited, a shorter duration of low-intensity therapy could potentially increase the number of children who are able to access a potentially effective amount of intervention.

This appears to be the first study to evaluate home-based provision of low-intensity direct ESDM therapy. Home-based therapy may be more convenient for parents (Sweet and Appelbaum 2004) and is arguably a more natural, and thus less restrictive, setting for children to receive intervention than a clinic (United Nations General Assembly 2007). In light of these advantages, the generally positive results of this study suggest that, when possible, therapists could consider providing at least some therapy sessions in the child’s home.

A strength of the present study was the assessment of generalization from therapist to parent. Indeed, this appears to be first study that seems to suggest there was some degree of generalization from the therapist to parent. Specifically, Alan, Chris, and Jeevan showed some increase on all of the dependent variables with their mothers following the intervention and Charlie showed generalization in his use of functional utterances. It is possible that these improvements represent generalization across person, in that what the child had learned with the therapist may have generalized to the parent (Stokes and Baer 1977). However, it is also possible that parents might have learned to implement some of the ESDM techniques as a result of observing the therapist-conducted sessions (Bandura et al. 1963). If this were the case, then what seems to be generalization might instead be attributed to the fact that the parents were using more ESDM techniques. In either case, the children’s behavior with their mothers in the generalization probes was usually not at the same level as it was with the therapist. This suggests that comparable levels of performance might have been obtained between parent and therapist sessions if parents had been using more of the ESDM techniques or applying the techniques with the same level of skill as the therapist.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it is not possible to attribute Chris’ improvements in intervals containing functional utterances to the ESDM intervention. This is because his baseline data suggest that his utterances were increasing prior to the start of intervention (Kennedy 2005). Further, partial interval recording of functional utterances may not have been the most developmentally appropriate or sensitive measure for Chris or Jeevan. This is because both Chris and Jeevan produced many functional utterances during intervention, which led to ceiling effects for the variable. Other measures such as mean length of utterance and variety of utterance may have been a more appropriate primary measure for these two children. Further, the children’s specific ADOS-2 scores (Lord et al. 2012) were not reported as they were collected by an independent clinician who was not able to share this information. Due to the non-concurrent design of this study, children did not begin baseline at the same time. Although there was some degree of overlap between phases for each child, this does compromise the rigor of the experimental design. In order to increase ease of coding and agreement between observers, the therapist fidelity of implementation of ESDM techniques was measured using an adapted, simplified version of the ESDM fidelity rating scale used in previous research (Rogers and Dawson, 2010). Therefore, it is not possible to directly compare therapist fidelity in the current study to fidelity in previous ESDM research. Also, the individuals who rated the videos were not blind to treatment phase or aims of the study, which could have led to expectancy bias. It is important to note that the four participants in the present study were different in terms of several relevant characteristics (e.g. language abilities, developmental level, and interests). This may be reflective of the heterogeneity of the larger autism spectrum (Dawson 2008). However, despite these differences, the intervention appeared to have been of some benefit to each child. This suggests that the present approach may be applicable to children with varying adaptive behavior profiles. However, the current findings also need to be replicated with a larger and more diverse sample of children with, or at risk for, ASD. Specifically, only four children participated in this study and all of these children were male. Three of the children were New Zealand European and Jeevan was Indian. Therefore, it is not clear how effective this intervention would have been for females with ASD or children of other cultural backgrounds or ethnicities. Finally, the therapy was only implemented by one therapist, who had relatively high fidelity, and it is not clear how this influenced the results.

In future studies, researchers could compare child outcomes following low-intensity therapist-delivered ESDM intervention with those following parent-delivered ESDM intervention. Some research suggests that parents are able to learn to implement ESDM intervention techniques and that their use of these techniques may lead to improvements for their children with ASD (e.g. Zhou et al. 2018). However, other research suggests that parent implementation was not better than ‘treatment-as-usual’ for improving parent use of ESDM techniques or child outcomes (Rogers et al. 2012). Logically, if parent-delivered intervention led to the same improvements in child outcomes as therapist-delivered intervention, then professional input may be better spent training the parents to implement the intervention. This is because parents may be able to implement the intervention for many more hours per day than the therapist and could also continue to implement the intervention in the long term (Rogers et al. 2012).

The positive results of this study should not be interpreted as implying that low-intensity intervention can be an equally effective replacement for more intensive early intervention. Overall, data indicate that the more hours of early intervention a child receives, the greater their improvement in outcomes (e.g. Klintwall et al. 2015, Reed et al. 2007, Smith et al. 2000), although some authors question the methods which are generally used to measure treatment intensity (Strauss et al. 2013). Nevertheless, our present findings do imply that lower-intensity interventions may still be of some benefit. In future, researchers should compare different intensities of ESDM intervention in order to determine the relations between outcomes and ‘dosage.’

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained for all individual participants included in the study.

Funding Statement

This research was supported in part by a PhD scholarship awarded to Hannah Waddington from the Autism Intervention Trust, through Victoria University of Wellington.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A., Ross, D. and Ross, S. A. 1963. Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66,3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaro, J. and Dissanayake, C. 2010. Prospective identification of autism spectrum disorders in infancy and toddlerhood using developmental surveillance: the social attention and communication study. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 31,376–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baril, E. M. and Humphreys, B. P. 2017. An evaluation of the research evidence on the early start Denver model. Journal of Early Intervention, 39,321–338. [Google Scholar]

- Bibby, P., Eikeseth, S., Martin, N. T., Mudford, O. C. and Reeves, D. 2002. Progress and outcomes for children with autism receiving parent-managed intensive interventions. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 23,81–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawarska, K., Klin, A., Paul, R. and Volkmar, F. 2007. Autism spectrum disorder in the second year: stability and change in syndrome expression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48,128–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombi, C., Narzisi, A., Ruta, L., Cigala, V., Gagliano, A., Pioggia, G., Siracusano, R., Rogers, S. J., and Muratori, F. 2016. Implementation of the early start Denver model in an Italian community. Autism, 22,126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, G. 2008. Early behavioral intervention, brain plasticity, and the prevention of autism spectrum disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 20,775–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, G. and Bernier, R. 2013. A quarter century of progress on the early detection and treatment of autism spectrum disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 25,1455–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, G., Rogers, S., Munson, J., Smith, M., Winter, J., Greenson, J., Donaldson, A., and Varley, J. 2010. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the early start Denver model. Pediatrics, 125,17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devescovi, R., Monasta, L., Mancini, A., Bin, M., Vellante, V., Carrozzi, M. and Colombi, C. 2016. Early diagnosis and early start Denver model intervention in autism spectrum disorders delivered in an Italian public health system service. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12,1379–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldevik, S., Eikeseth, S., Jahr, E. and Smith, T. 2006. Effects of low-intensity behavioral treatment for children with autism and mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36,211–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes, A., Munson, J., Rogers, S. J., Greenson, J., Winter, J. and Dawson, G. 2015. Long-term outcomes of early intervention in 6-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54,580–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes, A., Vismara, L., Mercado, C., Fitzpatrick, A., Elder, L., Greenson, J., Lord, C., Munson, J., Winter, J., Young, G., Dawson, G., and Rogers, S. 2014. The impact of parent delivered intervention on parents of very young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44,353–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag, C. M., Feineis-Matthews, S., Valerian, J., Teufel, K. and Wilker, C. 2012. The Frankfurt early intervention program FFIP for preschool aged children with autism spectrum disorder: a pilot study. Journal of Neural Transmission, 119,1011–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granpeesheh, D., Dixon, D. R., Tarbox, J., Kaplan, A. M. and Wilke, A. E. 2009. The effects of age and treatment intensity on behavioral intervention outcomes for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3,1014–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, S. L. and Handleman, J. S. 2000. Age and IQ at intake as predictors of placement for young children with autism: a four-to six-year follow-up. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30,137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, B., Lewis, E. and Kroman, E. 2007. Teaching the imitation and spontaneous use of descriptive gestures in young children with autism using a naturalistic behavioral intervention. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37,1446–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, B. and Schreibman, L. 2006. Teaching reciprocal imitation skills to young children with autism using a naturalistic behavioral approach: effects on language, pretend play, and joint attention. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36,487–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari, C., Freeman, S. and Paparella, T. 2006. Joint attention and symbolic play in young children with autism: a randomized controlled intervention study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47,611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasilingam, N., Waddington, H. and van der Meer, L. 2019. Early intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders in New Zealand: what children get and what parents want. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, C. 2005. Single-case designs for educational research. Boston, MA: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Klintwall, L., Eldevik, S. and Eikeseth, S. 2015. Narrowing the gap: effects of intervention on developmental trajectories in autism. Autism, 19,53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel, L. K., Ashbaugh, K. and Koegel, R. L. 2016. Pivotal response treatment. In Lang R., Hancock T. B. and Singh N. N., eds. Early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder. New York, NY: Springer, pp.85–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., Risi, S., Gotham, K. and Bishop, S. L. 2012. Autism diagnostic observation schedule, second edition (ADOS-2) manual (part I): modules 1-4. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Odom, S. L., Boyd, B. A., Hall, L. J. and Hume, K. 2010. Evaluation of comprehensive treatment models for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40,425–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie, E. and McCrudden, M. T. 2017. Evaluating the social validity of the early start Denver model: a convergent mixed methods study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47,2899–2910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, R. I. and Vannest, K. 2009. An improved effect size for single-case research: nonoverlap of all pairs. Behavior Therapy, 40,357–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters-Scheffer, N., Didden, R., Mulders, M. and Korzilius, H. 2013. Effectiveness of low intensity behavioral treatment for children with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7,1012–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, P., Osborne, L. A. and Corness, M. 2007. Brief report: relative effectiveness of different home-based behavioral approaches to early teaching intervention. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37,1815–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S. J. and Dawson, G. 2010. Early start Denver model for young children with autism: promoting language, learning, and engagement. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S. J., Dawson, G. and Vismara, L. A. 2012. An early start for your child with autism: using everyday activities to help kids connect, communicate, and learn. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S. J., Estes, A., Lord, C., Vismara, L., Winter, J., Fitzpatrick, A., Guo, M., and Dawson, G. 2012. Effects of a brief early start Denver model (ESDM)-based parent intervention on toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51,1052–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S. J., Herbison, J. M., Lewis, H. C., Pantone, J. and Reis, K. 1986. An approach for enhancing the symbolic, communicative, and interpersonal functioning of young children with autism or severe emotional handicaps. Journal of Early Intervention, 10,135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M., Bailey, A. and Lord, C. 2003. The social communication questionnaire manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Schreibman, L., Dawson, G., Stahmer, A. C., Landa, R., Rogers, S. J., McGee, G. G., Kasari, C., Ingersoll, B., Kaiser, A., Bruinsma, Y., McNerney, E., Wetherby, A. and Haliday, A.. 2015. Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45,2411–2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singal, A. G., Higgins, P. D. R. and Waljee, A. K. 2014. A primer on effectiveness and efficacy trials. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology, 5,e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, S., Balla, D. and Cicchetti, D. 2005. Vineland adaptive behavior scales: interview edition. 2nd ed. Circle Pines, MN: AGS. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T., Groen, A. D. and Wynn, J.W. 2000. Randomized trial of intensive early intervention for children with pervasive developmental disorder. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 105,269–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, T. F. and Baer, D. M. 1977. An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10,349–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, K., Mancini, F., Fava, L. and Specialisation in Cognitive Psychotherapy Group . 2013. Parent inclusion in early intensive behavior interventions for young children with ASD: a synthesis of meta-analyses from 2009 to 2011. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34,2967–2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet, M. A. and Appelbaum, M. I. 2004. Is home visiting an effective strategy? A meta‐ analytic review of home visiting programs for families with young children. Child Development, 75,1435–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly, 2007. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities [online]. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vismara, L. A., Colombi, C. and Rogers, S. J. 2009. Can one hour per week of therapy lead to lasting changes in young children with autism? Autism, 13,93–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivanti, G., Paynter, J., Duncan, E., Fothergill, H., Dissanayake, C., Rogers, S. J., and the Victorian ASELCC Team . 2014. Effectiveness and feasibility of the early start Denver model implemented in a group-based community childcare setting. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44,3140–3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddington, H., van der Meer, L. and Sigafoos, J. 2016. Effectiveness of the early start Denver model: a systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 3,93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B., Xu, Q., Li, H., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Rogers, S. J. and Xu, X. 2018. Effects of parent‐implemented early start Denver model Intervention on Chinese toddlers with autism spectrum disorder: a non‐randomised controlled trial. Autism Research, 11,654–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]