Abstract

Postoperative peritoneal adhesions were frequent complications for almost any types of abdominal and pelvic surgery. This led to numerous medical problems and huge financial burden to the patients. Current anti-adhesion strategies focused mostly on physical barriers including films and hydrogels. However, they can only alleviate or reduce adhesions to certain level and their applying processes were far from ideal. This work reported the development of a biodegradable zwitterionic cream gel presenting a series of characters for an idea anti-adhesion material, including unique injectable yet malleable and self-supporting properties, which enabled an instant topical application, no curing, waiting or suturing, no hemostasis requirement, protein/cell resistance and biodegradability. The cream gel showed a major advancement in anti-adhesion efficacy by completely and reliably preventing a primary and a more severe recurrent adhesion in rat models.

Keywords: cream gel, zwitterionic material, postoperative adhesion, anti-adhesion, adhesiolysis

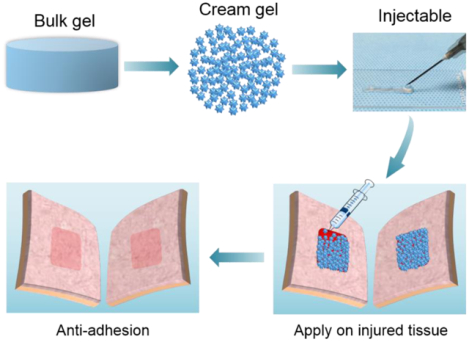

Graphical Abstract

Biodegradable zwitterionic cream gel presents injectable yet malleable and self-supporting properties and shows a series of characters for an idea anti-adhesion material including instant topical application, no waiting or suturing, no hemostasis requirement, protein/cell resistance. Cream gel shows a major advancement by completely and reliably prevent a primary and a more severe recurrent adhesion in rat models.

1. Introduction

Peritoneal adhesion is an inevitable consequence of almost any types of abdominal and pelvic procedures and is found in up to 90% of the patients.[1–3] It leads to numerous medical problems including pain both severe and chronic, female infertility, intestinal obstruction, etc.[4–7] Clinically, adhesiolysis, a second operation to release the adhesions, is typically conducted in patients experiencing post-operative adhesion-related complications.[1, 8, 9] This procedure, however, appeared to be even more complicated than primary surgery given the presence of primary or recurrent adhesions.[10,11] Even after adhesiolysis, the chance of adhesion reformation is still high since the new trauma caused by surgical lysis of established adhesions.[12–15] With high morbidity of postoperative adhesion and its related disorders, and huge associated economic burden to the patients,[16,17] there is an urgent clinical need for a safe and efficient anti-adhesion barrier to effectively prevent postoperative adhesion and the recurrent adhesion after adhesiolysis.

Current anti-adhesion strategies include mostly physical barriers. Film products such as Interceed® and Seprafilm® have been approved by FDA in the U.S., however their application process is inconvenient, i.e., requiring meticulous hemostasis and an effective suturing to be positioned on the injured tissue surface, susceptible to unwanted adherence to any wet surface including the surgeon’s gloves, and difficult in forming a conformal barrier on an irregular surface.[18–21] Comparatively injectable hydrogels, mostly under development, can be straightforwardly applied: the injected pre-gel solution is typically fluid-like and can completely cover the injured surface. This is followed by an in-situ polymerization, Michael addition thiol–ene reactions[25,26] or Schiff base amino-aldehyde reactions,[18,27,28] to form a chemically crosslinked hydrogel. Nevertheless, a dual valve applicator must be in place to separate the reactive components before they are mixed and extruded through the syringe. The applied pre-gel solution also require one to several minutes to completely cure,[18,25–28] which presents a burden in surgical duration and risk of infection. Certain chemical hydrogels require ultraviolet source for curing,[29,30] which poses further concerns on irradiation safety. By contrast, physical hydrogels such as thermo-responsive ones converted from liquid form to gel form at body temperature eliminate the need for chemical reaction or ultraviolet irradiation in vivo.[31,32,33] But minutes of waiting time still has to be allowed for the physical gels to solidify. With the problems above associating with the applying processes, current physical barriers remained under-performed and can only alleviate or reduce adhesions to some extent.

Here we report the development of the first-of-its-type cream gel formulation for anti-adhesion applications (Figure 1a) with a major leap of efficacy in completely and reliably preventing postoperative adhesion (Figure 1b, c), as demonstrated in two different but increasingly challenging rat models (abdominal wall defect-cecum abrasion adhesion model and repeated-injury adhesion model).

Figure 1.

Biodegradable zwitterionic PCBAA cream gel showed the characters of an ideal anti-adhesion material. a) Overview scheme showing the preparation of zwitterionic PCBAA cream gel with carboxybetaine acrylamide (CBAA) monomer and biodegradable N, N’-bis(acryloyl)cystamine (BAC) crosslinker. b) The injectable yet malleable and self-supporting cream gel can be applied through needles and immobilized on any irregular surface through convenient topical application. c) Schematic representation of applying the zwitterionic cream gel for preventing postoperative adhesion. d) Schematic representation of adhesion formation between two traumatized tissues without a treatment.

Unlike current anti-adhesive films or hydrogels replying on suturing or curing to be immobilized on the traumatized surface, the cream gel formulation can be immediately immobilized on any irregular surface through convenient topical application (no waiting), due to its injectable yet malleable and self-supporting properties (Figure 1a, d, Figure S1, Supporting Information). For instance, the cream gel can be conveniently injected through a syringe (Video S1, Supporting Information) or a needle (Video S2, Supporting Information) depending on the surgical need to fully cover a wound surface without performing hemostasis, and then immediately remain on the injured surface even when the surface was inverted or rotated (Video 3, Supporting Information).

Deviate from majority of current anti-adhesion materials that solely served as a physical barrier, our cream gel was made of non-fouling zwitterionic polymers (Figure 1a) that were known for remarkable prevention of protein and cell adhesions.[34,35] Since fibronectins and fibroblasts are major contributors during the development of tissue adhesion,[36,37] the use of zwitterionic materials likely explained the significant leap of anti-adhesion efficacy obtained.

Moreover, our cream gel can be easily prepared by grinding and repeatedly extruding a bulk hydrogel through needles (Figure 1a). During the preparation of the bulk hydrogel, a disulfide crosslinker was introduced. We showed that the resulting cream gel was biodegradable under reducing conditions, such as in presence of glutathione (GSH) which was normally found in bloodstreams and body fluids. It should be noted that degradability is commonly required for clinical anti-adhesion applications.

2. Results and Discussion

To prepare the biodegradable zwitterionic bulk hydrogel, carboxybetaine acrylamide (CBAA) monomer was crosslinked with a crosslinker containing disulfide bonds, N, N’-bis(acryloyl)cystamine (BAC). After complete equilibration in PBS, we processed the bulk gels into cream gels by grinding and repeatedly extruding through different gauge of needles. The resulting cream gel can be easily injected through a 26-gauge needle with a mean particle diameter of 20–50 μm (Figure S2, Supporting Information). It should be noted that the overall preparation process of the PCBAA cream gel is straightforward without any complicated chemical reactions, which enables an easy scale-up with required sterilization implemented. The particle size of the cream gel can be adjusted by changing the needle gauges.

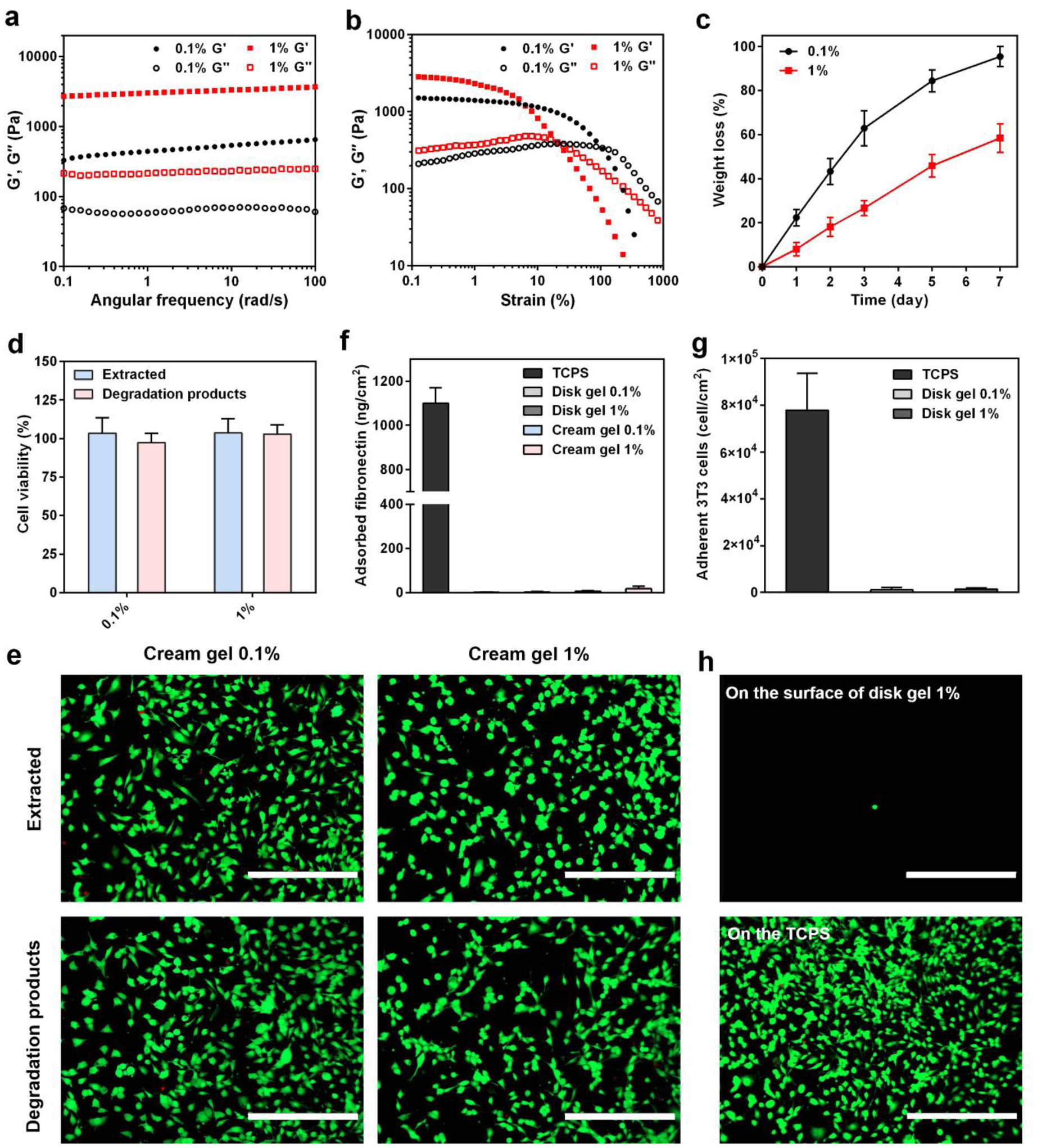

The viscoelastic properties of the cream gels were studied by rheological tests. Frequency-dependent oscillatory sweeps in the linear viscoelastic regime (under 1% strain) showed that the storage modulus (G′) was dominant over the loss modulus (G″) over the full angular frequency range (0.1–100 rad s−1) (Figure 2a). This indicated that cream gels with different crosslinker content (0.1% or 1% BAC) maintained a solid-like behavior over the entire frequency range. In a strain-dependent oscillatory rheological measurement, the cream gels maintained the solid-like behavior at the low strain range (0.1–10%) with G′ higher than G″, but adopt more viscous behavior at high strain region where G′ became lower than G″ (Figure 2b). It should be noted that the highest strain experienced by tissues in the body have been reported to be less than 10%.[38] This implies that our cream gels were likely to maintain the solid-like behavior at in vivo environment for anti-adhesion purpose.

Figure 2.

Rheological properties, biodegradability, cytotoxicity and protein/cell resistance of the cream gels. a,b) Frequency-dependent (a, under 1% strain, 25 °C) and strain-dependent (b, 10 rad/s frequency, 25 °C) oscillatory sweeps of cream gel formulations with different crosslinker content (0.1% or 1% BAC). c) In vitro biodegradation of cream gel formulations with different crosslinker content (0.1% or 1% BAC). Data presented as mean ± s.d. (n = 3). d,e) NIH/3T3 fibroblast cells were incubated with both the cream gel extract and the degradation products (cream gel degraded in DMEM with 20 mM GSH for 48 h at 37 °C) with different crosslinker content (0.1% or 1% BAC) for 24 h. Cytotoxicity was evaluated through the cell viability test (d, data presented as mean ± s.d. n = 6) and live/dead imaging (e, scale bar = 400 μm). f) Fibronectin adsorption on the surface of disk gels or cream gels using a BCA protein quantification assay. Data presented as mean ± s.d. (n = 6). g,h) Quantification (g, data presented as mean ± s.d. n = 6) and representative fluorescence images (h, scale bar = 400 μm) of NIH/3T3 fibroblasts adhered on the disk gel surface.Note: Please do not combine figure and caption in a textbox or frame.

The biodegradability of the cream gels was examined in 10 mL of PBS containing 20 μM GSH (mimicking the concentration in bloodstream and body fluids [39,40]) at 37 °C. All cream gels were found to gradually degrade over time as reflected by the weight loss (Figure 2c). Cream gel with 0.1% BAC crosslinker had more than 60% degraded on day 3 and almost totally degraded on day 7. Cream gel with 1% BAC showed a slower degradation rate, with less than 60% degraded on day 7.

We further examined the cytotoxicity of both the cream gel extract and the degradation products (cream gel degraded in DMEM with 20 mM GSH for 48 h at 37 °C) through in vitro cell viability test and live/dead imaging. Both the extract and degradation products exhibited no significant cytotoxicity on the 3T3 cells regardless of the BAC content (Figure 2d), which was also confirmed through live/dead staining (Figure 2e).

It has been well recognized that fibronectin adsorption and fibroblast adhesion were critical steps leading to a connection between damaged intra-abdominal surfaces and subsequent adhesion development.[36,37,41] Our in vitro study showed that few fibronectin was able to adhere on the surface of disk gels or cream gels using a BCA protein quantification assay (Figure 2f). This is because of their zwitterionic make with ultralow fouling properties that have been attributed to strong hydration capability of the material.[35] By contrast, a large number of fibronectin was found to adhere on the tissue culture plate (TCPS) surface (> 1000 ng/cm2). We further seeded fibroblasts (3T3 cells) on the surfaces of disk gels and cream gels followed by cell staining under a fluorescent microscopy. Few spherical cells were observed on the disk gel surface (data for cream gel surface not available due to light reflection of gel particles) whereas a large number of 3T3 cells settled and spread on the TCPS surface (Figure 2g, h, and Figure S3, Supporting Information).

Among the tested samples, the cream gel with 1% BAC crosslinking was selected for further in vivo anti-adhesion evaluation due to appropriate rheological, cell-compatibility, and protein/cell resistance properties. In particular, this formulation had a slower degradation profile to ensure the protection of traumatized surface during the first 3–4 days after the surgical injury, which is a key period for tissue adhesion formation when fibroblasts invasion and adhesion prevail.[36]

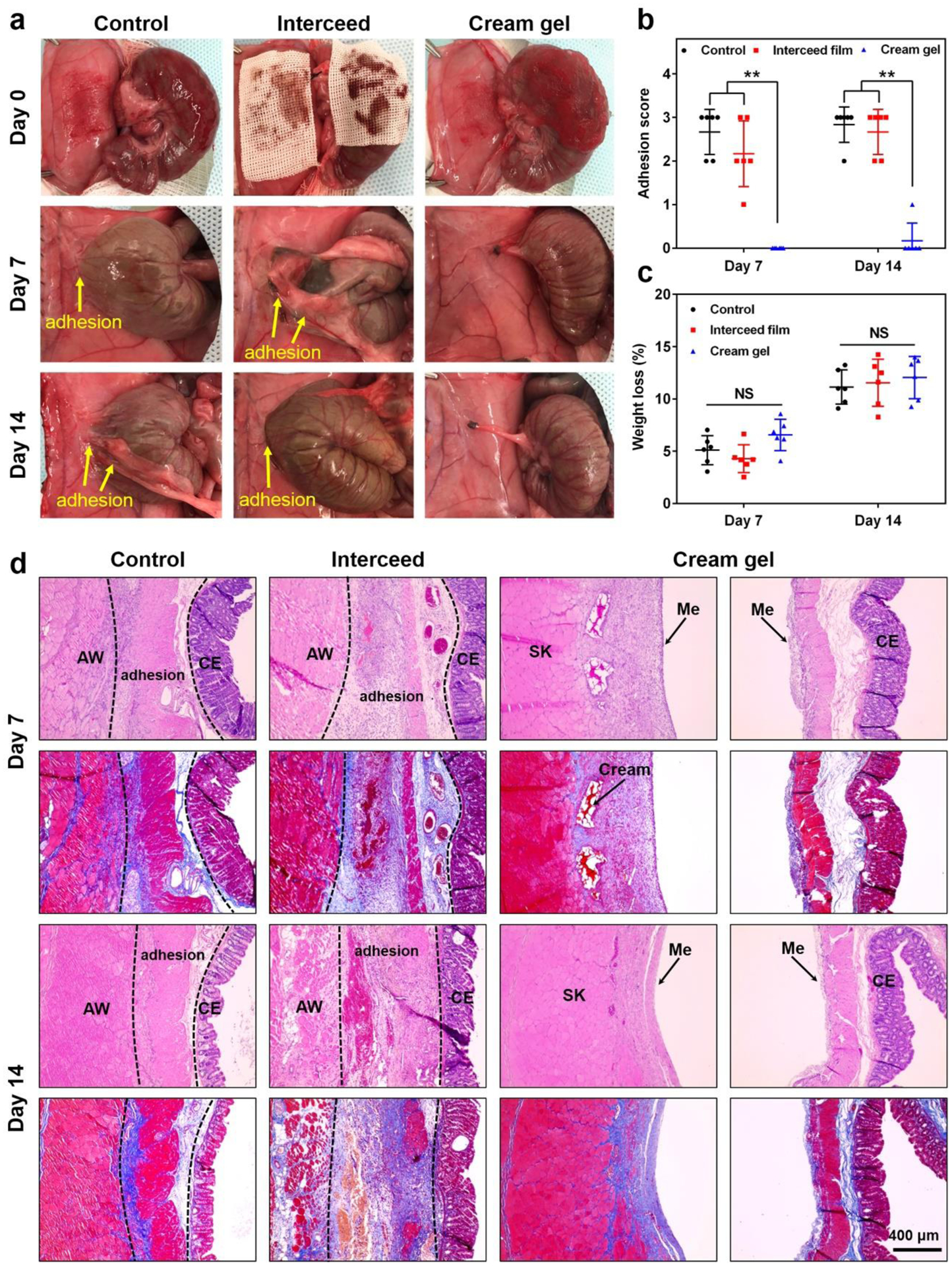

We first evaluated the anti-adhesion efficacy of the cream gel in a rat sidewall defect-cecum abrasion model. Defects on the cecum and the abdominal wall were created by abrasion and excision, respectively, followed by the application of 2 mL of cream gel on both traumatized surfaces (Figure 3a, Video S1, Supporting Information). On day 7 and 14 post-surgery, the peritoneum was opened and examined with the level of adhesion, if any, scored. Model group without any anti-adhesion treatment showed severe abdominal adhesions on day 7 and 14 (Figure 3a, b). Treatment with a commercial Interceed® film (2×2 cm) appeared to lower the adhesion score (alleviate the adhesion) compared with untreated group but still presented significant adhesions. Cream gel treatment, by contrast, showed nearly a complete protection: on day 7, 6 out of 6 showed no observable adhesion (score 0); on day 14, 5 out of 6 no observable adhesion and 1 out of 6 minor adhesion (score 1). The change of body weight 7 or 14 days post-surgery did not vary significantly among these groups (p > 0.05) (Figure 3c). Tissues from injured sites were collected for histological analysis for day 7 and 14. Results from Hematoxylin and Eosin, and Masson trichrome staining supported the observative scoring: connective/adhesive regions can be easily identified for the untreated and film treated groups (the deposited collagen in the adhesion site was stained in blue while muscle showed red in Masson trichrome staining), but can hardly be located in cream gel treated group since no adhesion developed at all (histology for injured abdominal wall and cecum was performed separately) (Figure 3d). It should be noted that majority of the cream gel was decomposed and disappeared from the injured sites by day 7, and by day 14 the cream gel was completely gone, as observed through autopsy and histology examination (Figure 3a, d). The degradation is potentially attributed to GSH (previously tested in vitro), which was normally found in blood streams and body fluids.[39] Tissue sections from major organs collected on day 7 and 14 indicated no damage or inflammatory reactions upon cream gel treatment when compared with healthy tissues (Figure S4, Supporting Information). Further examination on injured tissue treated with cream gel showed limited inflammatory reaction or immune cell infiltration induced by the cream gel or its degraded substances on day 7, and a completely healed injured surface without observable infiltrated immune cells on day 14 (Figure S5, Supporting Information). These results overall indicate that the biodegradable cream gel was able to completely and reliably prevent adhesion in the abdominal wall defect-cecum abrasion adhesion model, and be effectively cleared over time without eliciting toxicity.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of anti-adhesion efficacy in a rat sidewall defect-cecum abrasion adhesion model. a) The establishment of a rat sidewall defect-cecum abrasion adhesion model and the application of commercial Interceed film or cream gel onto the traumatized sites (day 0). On day 7 and 14 post-surgery, adhesions were observed in the untreated control and Interceed film groups while no adhesion was observed in rats treated with cream gel. b,c) Distribution of adhesion scores (b) and weight loss (c) in different groups on day 7 and 14 after the surgery. Data presented as mean ± s.d. (n = 6). **P < 0.01; NS, not significant. d) Representative histology images (H&E and Masson trichrome staining) of tissues from different groups on day 7 and 14 after surgery, respectively. AW: abdominal wall; CE: cecal mucosa; Me: mesothelial layer; SK: skeletal muscle of AW.

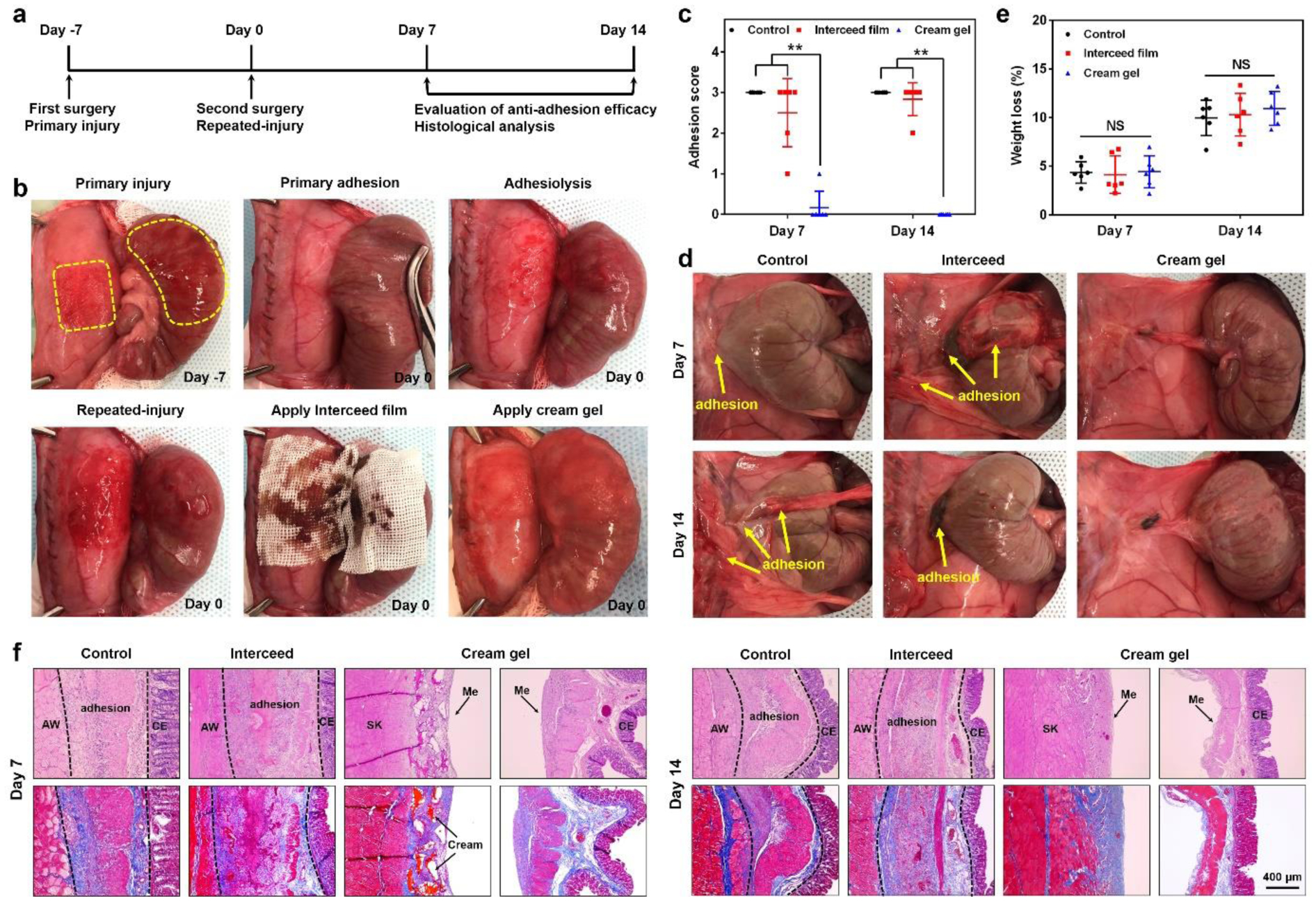

We further evaluated the anti-adhesion efficacy of the cream gel in a more rigorous rat repeated-injury adhesion model. This model mimics when a recurrent adhesion was developed after conducting adhesiolysis, which was indispensable to address a primary adhesion but created more severe trauma and adhesion. Despite of the high frequency for recurrent adhesion (> 55%), there is limited commercial barriers targeting its prevention.[12,15] Anti-adhesion materials under development showed an efficacy in a primary adhesion model[28, 42] but failed in a more rigorous recurrent or repeated-injury adhesion model.[43–45] To establish the repeated-injury adhesion model, a first abdominal wall and cecum injury was created without any anti-adhesion treatment. 7 days later, the primary adhesion was developed, adhesiolysis was conducted, and a second injury was created. This was followed by cream gel treatment, film treatment, or none of the treatment (Figure 4a, b). Compared with the primary adhesion model (Figure 3), this recurrent model presented a much more sever adhesion when no treatment applied (score 3 for all animals on both day 7 and 14 post surgery) (Figure 4c, d). Commercial film treatment can only slightly relieve the recurrent adhesion. But cream gel treatment remarkably achieved a nearly complete prevention: on day 7, 5 out of 6 showed no observable adhesion (score 0) and 1 out of 6 minor adhesion (score 1); on day 14, 6 out of 6 no observable adhesion. The change of body weight 7 or 14 days post-surgery also not differed significantly among groups (p > 0.05) (Figure 4e). Histological results for day 7 and 14 were consistent with the scoring results, supporting the reliably anti-adhesion efficacy of the cream gel (Figure 4f). The biodegradable cream gel appeared to be similarly cleared as in the primary adhesion model, with gel particles presented on the injured abdominal wall on day 7 but completely gone on day 14, as indicated by both autopsy and histology. Similar to the primary adhesion model, no significant inflammation or immune cell infiltration to the injured sites induced by the cream gel or its degraded substances was observed (Figure S5, Supporting Information). Further examination on day 30 post surgery showed that the more severely injured tissue after the cream gel treatment recovered to a condition as good as a healthy tissue (Figure S6, Supporting Information). Overall our results further support the efficacy of the cream gel in completely and reliably preventing the more rigorous recurrent adhesion in the rat repeated-injury adhesion model.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of anti-adhesion efficacy in a rat repeated-injury adhesion model. a) Schematic illustration of the procedure schedule. b) Procedures to establish the rat repeated-injury model and apply anti-adhesion materials onto the re-injured sites. A first abdominal wall and cecum injury was created without any anti-adhesion treatment (day −7). One week later, the developed primary adhesion was separated by adhesiolysis and a second injury was created (day 0). This was immediately followed by cream gel treatment or film treatment. c, d) Distribution of adhesion scores (c, Data presented as mean ± s.d., n = 6, **P < 0.01) and representative photographs (d) of recurrent adhesions in different groups on day 7 and 14 after the second surgery. e) Weight loss (as a percentage of starting body mass) in different groups on day 7 and 14 after the second surgery. Data presented as mean ± s.d. (n = 6). NS, not significant. f) Representative histology images of tissues from different groups on day 7 and 14 after the second surgery. AW: abdominal wall; CE: cecal mucosa; Me: mesothelial layer; SK: skeletal muscle of AW.

3. Conclusion

To summarize, we presented for the first time a zwitterionic polymer based cream gel was able to completely and reliably prevent a primary and a more severe recurrent adhesion in rat models. The novel cream gel was unique in injectable yet malleable and self-supporting properties, and showed a series of characters for an idea anti-adhesion material, including instant topical application, no curing, waiting or suturing, no hemostasis requirement, protein/cell resistance and biodegradability. We expect the cream gel to be next generation anti-adhesion materials addressing safety, efficacy and operational convenience to meet current clinical need.

4. Experimental Section

Materials:

The carboxybetaine acrylamide (CBAA) monomer was prepared following a previously published method.[46] N, N’-bis(acryloyl)cystamine (BAC), ammonium persulfate (APS), glutathione (GSH), rat plasma fibronectin (F0635), phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS), and paraformaldehyde were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Hyclone Laboratories. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), 0.25% trypsin-EDTA, and Live/Dead viability/cytotoxicity kit were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Commercially available Interceed® Absorbable Adhesion Barrier (Johnson & Johnson) was obtained from Medex Supply. National Institutes of Health 3T3 (NIH/3T3) mouse embryonic fibroblast cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection without further authentication.

Preparation of zwitterionic PCBAA bulk gel and cream gel:

N, N’-bis(acryloyl)cystamine (BAC) crosslinker (0.1 or 1 % relative to monomer by weight) and APS initiator (0.2% relative to monomer by weight) were added to the 40 wt % CBAA monomer solution, then the resulting solution was purified by a 0.22-μm filter. After thorough mixing and degassing, the solution was stored at a vial to prepare the bulk hydrogel at 37 °C for 24 h or transferred into two glass slides with a 0.1 mm polytetrafluoroethylene spacer to prepare hydrogel disk, followed by equilibration in sterile PBS for 3 days. The bulk gel was further repeatedly extruded through sterile 18G, 20G, 22G, and 26G needles to obtain cream gel.

Rheological measurements:

Rheological characterization was performed using an ARG2 rheometer (TA Instruments Inc., New Castle, DL) equipped with 20 mm or 40 mm diameter parallel plates at 25 °C. For oscillatory frequency sweep test, a solvent trap bar was loaded to avoid evaporation. All results were recorded and analyzed using TA Instruments TA Orchestrator software.

In vitro degradation of PCBAA cream gel:

In vitro degradation of PCBAA cream gel was monitored by measuring weight loss over time. 1 mL of cream gel was lyophilized and recorded as the initial weight. Then 1 mL of cream gel was immersed in 10 mL of PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4) containing 20 μM GSH and incubated in a shaking bath at 37 °C at 125 rpm. The degradation media were refreshed daily to ensure the GSH concentration. At predetermined time points, the cream gels were lyophilized and weighed.

In vitro cytotoxicity and live/dead assay:

In vitro cytotoxicity was evaluated by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay using National Institutes of Health (NIH) 3T3 mouse embryonic fibroblast cells. 3T3 cells were seeded on 96-well plates (2 × 104 cells well−1) in DMEM with 10% FBS and cultured in 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C for 24 h. Then culture media were substituted by DMEM containing PCBAA cream gel extraction or degradation products for another 24 h incubation. The cream gel extraction was obtained by incubating 1 mL of cream gel in DMEM with 10% FBS for 48 h at 37 °C. The media containing degradation product was prepared by incubating 1 mL of cream gel in DMEM with 20 mM GSH for 48 h at 37 °C. After the challenge, the cell media were replaced with 150 μL of HBSS containing MTT (0.5 mg mL−1), followed by a further incubation at 37 °C for 4 h. Subsequently, the supernatant was replaced by dimethyl sulfoxide (150 μL well−1). The absorbance was tested by microplate reader (Bio-Rad) at 570 nm. The cells cultured with regular DMEM medium were used as a negative control for 100% cell viability. Live/dead assay was conducted by staining the 3T3 cells with 150 μl of PBS buffer containing 2 μM Calcein and 4 μM ethidiumhomodimer-1 (Live/Dead viability/cytotoxicity kit, Invitrogen) for 30 min at room temperature and observed under a EVOS FL fluorescence microscope (AMG).

Fibronectin adsorption assay:

The fibronectin adsorption on disk and cream gel was evaluated by a standard bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method as follows. After being equilibrated with PBS for 3 days, PCBAA hydrogel disk (12 mm in diameter and 0.2 mm in thickness) or 100 μL of PCBAA cream gels were immersed in 0.5 mL of fibronectin solution (50 μg mL−1) at 37 °C for 2 h. Then fibronectin solution was removed and the cream gels were carefully rinsed with fresh PBS three times. The cream gels were then soaked in 0.5 mL of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for 1 h to detach the adsorbed protein. The concentration of the adsorbed protein was determined using a micro-BCA™ protein assay reagent kit by microplate reader at 562 nm.

Cell adhesion assay:

2 × 104 of 3T3 cells were seeded on the surface of PCBAA hydrogel disk (12 mm in diameter and 0.2 mm in thickness) and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 48 h. Then cell media were removed and the hydrogel disk was gently rinsed with HBSS to remove the unattached cells. 3T3 cells attached on the surface was stained by Live/Dead kit and the morphology was observed by the EVOS FL fluorescence microscope (AMG). 3T3 cells seeded in the tissue culture plate (TCPs) were used as a control.

In vivo anti-adhesion evaluation in a rat abdominal wall and cecum defect model:

The animal work involved in this study has been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Wayne State University. Sprague-Dawley rats (Male, 250 ± 20 g, purchased from Charles River Laboratory) received buprenorphine SR (0.4 mg kg−1) prior to surgery. Under an appropriate anesthesia (isoflurane inhalation), the abdominal skin was shaved and prepped with three alternating scrubs of betadine and 70% alcohol, followed by a single incision (4–5 cm long) along the linea alba on the abdominal wall using surgical scissors. The serosal surface of the cecum was gently abraded using a dry surgical gauze (50 strokes) to result in a visible hemorrhaging. A peritoneal defect on the right lateral abdominal wall (1.5 × 2 cm; including the parietal peritoneum and ~1 mm of muscle) was further created using a scalpel. The injured cecum and abdominal wall were forced to contact each together by suturing the surrounding mesentery with 3–0 PDS suture. For anti-adhesion treatment, cream gel was injected onto the injured abdominal wall and cecum without hemostasis. For the film treatment group, a commercial Interceed® film was used to cover the defects. 7 and 14 days after the surgery, rats were euthanized to open the peritoneum and examine the adhesion level. A standard adhesion scoring system was used: score 0, no adhesion; score 1, mild, easily separable intestinal adhesion; score 2, moderate intestinal adhesion, separable by blunt dissection; and score 3, severe intestinal adhesion requiring sharp dissection to separate. Cecum and abdominal wall tissues relating to the injury and/or adhesion were collected and processed for histological evaluation (Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and Masson trichrome) under an EVOS XL Core microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

In vivo anti-adhesion evaluation in a rat repeated-injury adhesion model:

The repeated-injury adhesion model was established first by creating a primary adhesion as described in the sidewall defect-cecum abrasion model without applying any anti-adhesion material. 7 days later, a second laparotomy was performed, and the primary adhesion was separated by an appropriate dissection, followed by abrading the separated abdominal wall and cecum monodirectionally with a sterilized brush to produce a bleeding surface. For anti-adhesion treatment, cream gel or Interceed® film was similarly applied as described in the prior model. 7 and 14 days after the surgery, rats were subject to adhesion scoring and histological evaluation as described in the prior model.

Statistical analysis:

All data were presented as mean ± s.d. and statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software. Adhesion scores did not always follow a normal distribution, so statistical analysis was performed using a non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test. The data of body weight were normal distributed and analysed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multi-comparison tests. For all statistical analyses, significance was accepted at the 95% confidence level, and all analyses were two-tailed. Statistical differences were defined as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and differences with P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the faculty start-up fund at Wayne State University, National Science Foundation (1410853 and 1809229) and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (DP2DK111910 and R01DK123293). We thank Prof. Weiping Ren of Wayne State University Biomedical Engineering for the access of rheometer.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Menzies D, Ellis H, Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl 1990, 72, 60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Okabayashi K, Ashrafian H, Zacharakis E, Hasegawa H, Kitagawa Y, Athanasiou T, Darzi A, Surg. Today 2014, 44, 405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Brochhausen C, Schmitt VH, Planck CN, Rajab TK, Hollemann D, Tapprich C, Krämer B, Wallwiener C, Hierlemann H, Zehbe R, J. Gastrointest. Surg 2012, 16, 1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Diamond MP, Freeman ML, Hum. Reprod 2001, 7, 567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Liakakos T, Thomakos N, Fine PM, Dervenis C, Young RL, Dig. Surg 2001, 18, 260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ten Broek RP, Stommel MW, Strik C, van Laarhoven CJ, Keus F, van Goor H, Lancet 2014, 383, 48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Vrijland W, Jeekel J, Van Geldorp H, Swank D, Bonjer H, Surg. Endosc 2003, 17, 1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brown CB, Luciano AA, Martin D, Peers E, Scrimgeour A, Group AARS, Fertil. Steril 2007, 88, 1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Swank D, Swank-Bordewijk S, Hop W, Van Erp W, Janssen I, Bonjer H, Jeekel J, Lancet 2003, 361, 1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Robinson JK, Colimon LMS, Isaacson KB, Fertil. Steril 2008, 90, 409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tittel A, Treutner K, Titkova S, Öttinger A, Schumpelick V, Langenbecks Arch. Surg 2001, 386, 141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhang E, Guo Q, Ji F, Tian X, Cui J, Song Y, Sun H, Li J, Yao F, Acta Biomater 2018, 74, 439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tittel A, Treutner K, Titkova S, Öttinger A, Schumpelick V, Surg. Endosc 2001, 15, 44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cai H, Qiao L, Song K, He Y, J. Minim. Invasive. Gynecol 2017, 24, 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yang JH, Chen CD, Chen SU, Yang YS, Chen MJ, BJOG 2016, 123, 618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].ten Broek RP, Strik C, Issa Y, Bleichrodt RP, van Goor H, Ann. Surg 2013, 258, 98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ten Broek RP, Issa Y, van Santbrink EJ, Bouvy ND, Kruitwagen RF, Jeekel J, Bakkum EA, Rovers MM, van Goor H, BMJ 2013, 347, f5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Li L, Wang N, Jin X, Deng R, Nie S, Sun L, Wu Q, Wei Y, Gong C, Biomaterials 2014, 35, 3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Li J, Xu W, Chen J, Li D, Zhang K, Liu T, Ding J, Chen X, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2017, 4, 2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Stapleton LM, Steele AN, Wang H, Hernandez HL, Anthony CY, Paulsen MJ, Smith AA, Roth GA, Thakore AD, Lucian HJ, Nat. Biomed. Eng 2019, 3, 611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].GYNECARE INTERCEED® Absorbable Adhesion Barrier. Instructions for Use. Ethicon US, LLC. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Verco SJ, Peers EM, Brown CB, Rodgers KE, Roda N, diZerega G, Hum. Reprod 2000, 15, 1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Diamond MP, Group TSAS, Fertil. Steril 1998, 69, 1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Grainger DA, Meyer WR, Decherney AH, Diamond MP, J. Gynecol. Surg 1991, 7, 97. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhu W, Gao L, Luo Q, Gao C, Zha G, Shen Z, Li X, Polymer Chemistry 2014, 5, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Guo Q, Sun H, Wu X, Yan Z, Tang C, Qin Z, Yao M, Che P, Yao F, Li J, Chem. Mater 2020, 32, 6347. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hu W, Zhang Z, Zhu L, Wen Y, Zhang T, Ren P, Wang F, Ji Z, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2020, 6, 1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yeo Y, Highley CB, Bellas E, Ito T, Marini R, Langer R, Kohane DS, Biomaterials 2006, 27, 4698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yang Y, Liu X, Li Y, Wang Y, Bao C, Chen Y, Lin Q, Zhu L, Acta Biomater 2017, 62, 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hill-West JL, Chowdhury SM, Sawhney AS, Pathak CP, Dunn RC, Hubbell JA, Obstet. Gynecol 1994, 83, 59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sultana T, Van Hai H, Abueva C, Kang HJ, Lee S-Y, Lee B-T, Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl 2019, 102, 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhang E, Li J, Zhou Y, Che P, Ren B, Qin Z, Ma L, Cui J, Sun H, Yao F, Acta Biomater. 2017, 55, 420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sultana T, Gwon JG, Lee BT, Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2020, 110, 110661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jiang S, Cao Z, Adv. Mater 2010, 22, 920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chen S, Zheng J, Li L, Jiang S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 14473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Moris D, Chakedis J, Rahnemai-Azar AA, Wilson A, Hennessy MM, Athanasiou A, Beal EW, Argyrou C, Felekouras E, Pawlik TM, J. Gastrointest. Surg 2017, 21, 1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Boland GM, Weigel RJ, J. Surg. Res 2006, 132, 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Evans ND, Oreffo RO, Healy E, Thurner PJ, Man YH, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 2013, 28, 397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lee MH, Yang Z, Lim CW, Lee YH, Dongbang S, Kang C, Kim JS, Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 5071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Talelli M, Vicent MJ, Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 4168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Alpay Z, Saed GM, Diamond MP, Semin. Reprod. Med 2008, 26, 313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yang B, Gong C, Zhao X, Zhou S, Li Z, Qi X, Zhong Q, Luo F, Qian Z, Int. J. Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Wu Q, Wang N, He T, Shang J, Li L, Song L, Yang X, Li X, Luo N, Zhang W, Sci. Rep 2015, 5, 13553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].He T, Zou C, Song L, Wang N, Yang S, Zeng Y, Wu Q, Zhang W, Chen Y, Gong C, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 33514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Yeo Y, Adil M, Bellas E, Astashkina A, Chaudhary N, Kohane DS, Control Release J 2007, 120, 178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wang W, Lu Y, Zhu H, Cao Z, Adv. Mater 2017, 29, 1606506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.