Abstract

The prevalence of autism continues to rise, yet the ability to receive treatment or caregiver training through traditional in-person methods continues to be a precluding factor for many families. Studies have shown that parent training provides benefits to caregivers and children through increased success of interventions, implementation, and generalization of skills. This study evaluated the effect of using technology for remote caregiver training of a token economy for use during routine non-preferred activities. A multiple-baseline design was implemented across two participants, through three phases. Additional surveys and interviews were conducted to evaluate social validity. Results revealed that caregivers acquired necessary skills to implement the fixed interval schedule of reinforcement with token system and participants reported experiencing greater positive interactions with the children. Limitations of this study included no data were collected on the children’s behavior, nor were they trained on token economy use. Extraneous variables may have affected the results, such as unplanned household events. Results suggest that remote caregiver training can increase desirable interactions between caregiver and child, improve socially significant behaviors, and extend resources not typically available to all families.

Keywords: Technology, parent training, remote training, fixed interval schedule of reinforcement, token economy

Introduction

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that 1 in 54 children are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a 15% increase over the previously reported figures from 2016 (Maenner et al. 2020). Autism prevalence is similar for rural (0.9%) versus urban (1.0%) populations; however, ASD awareness is 2.5 times greater in urban areas than rural, and doctors are more likely to recommend school resources for rural populations (40%) versus urban (28%) (Antezana et al. 2017). Interestingly, rural areas rely more heavily on schools for diagnosis and treatment; however, Antezana et al. (2017) note that individuals identified through schools are least likely to receive professional services. The contributing factors to the lack of professional services in rural areas include: geographic barriers, lacking ASD awareness, cultural perspectives, low socioeconomic status, low educational attainment, limited professional specialty or availability, and lack of evidence-based practices for screening and treatment of ASD (Antezana et al. 2017).

Early intervention has shown to greatly benefit the developmental prognosis of those with ASD (Boisvert and Hall 2014, McConachie et al. 2005). Along with early intervention, caregiver involvement in the treatment of children with ASD is paramount to the success of interventions, implementation, and generalization of skills (Boisvert and Hall 2014). The caregiver spends a majority of the interactive time with the client, therefore, involving the caregiver in the treatment plan allows for more exposure to the methods implemented. The behavioral skills taught are then more naturally generalized across individuals (both the therapist and caregivers) because there are a number of different individuals reinforcing the appropriate behaviors as opposed to the therapist alone (Boisvert and Hall, 2014). Additionally, caregiver training provides more in-depth understanding of the methods and procedures being implemented in treating the child, a better understanding of how to interpret the child’s needs, and increased confidence in both working with that particular child as well as in advocating for the child’s needs throughout development (Suppo and Floyd 2012). Caregiver training has been shown to produce a noticeable decrease in disruptive behavior of children with ASD over caregiver education alone (Bearss et al. 2015, Bearss et al. 2018, Iadarola et al. 2018).

Numerous studies have shown that caregiver training provides benefits to both caregivers and children alike (Boisvert and Hall 2014, Ingersoll and Berger 2015, Kuravackel et al. 2017, Suppo and Floyd 2012, Vismara et al. 2013); however, the ability to receive treatment and/or caregiver training through traditional in-person methods continues to be a precluding factor for many families (Bearss et al. 2018, Iadarola et al. 2018, Lindgren et al. 2016, Suppo and Floyd 2012, Tomlinson et al. 2018, Wainer and Ingersoll 2015). Cost, time, and availability of services in areas where board-certified behavior analyst (BCBA) services are sparse often impede successful treatment. Overextended family schedules, work schedules (especially within dual-income homes), cost (treatment session copays, transportation, time detracted from other family members or daily tasks), and the mental and physical strain of maintaining intensive in-person treatment often lead to lower adherence and attendance with treatment for children with ASD (Carr et al. 2016). The search for a feasible method of behavioral services and caregiver training, available to all individuals, leads to rapidly developing telehealth opportunities.

Telehealth is becoming more widely accepted and desirable as a convenient means of receiving health-related services where an office visit is not absolutely necessary (Ray and Topol 2016). In addition, given the COVID-19 pandemic, many practitioners are delivering services through telehealth that are not yet founded in ABA research. The current telehealth model is that of the medical one where patients receive general practitioner health diagnoses, follow-up consultations, mental health evaluations or treatment, and prescriptions for medication in states which allow remote prescription (Polinski et al. 2016). Services can be provided more conveniently to the client family, breaking down barriers of distance, mobility, and time. While telehealth is still an emerging technology, initial research has shown that these methods can be effective for providing behavioral treatment (Kuravackel et al. 2017, Tomlinson et al. 2018, Vismara et al. 2013), parent training in implementing treatment (Boisvert and Hall 2014), and in reducing the cost and overall caretaker stress levels in meeting treatment requirements (Langabeer et al. 2017, Lindgren et al. 2016, Suppo and Floyd 2012, Tomlinson et al. 2018, Wainer and Ingersoll 2015).

Gaps in the available research regarding telehealth applied to the ABA field justify further research focusing on specific treatment methods, generalization, and social validity measures within behavioral treatment. Much of the evidentiary benefits are derived from telehealth studies within adjacent disciplines such as mental health outcomes, hospitalization follow-up treatments, and cost-benefit analyses (Bagayoko et al. 2014, Bounthavong et al. 2018, Choi et al. 2014, Kruse et al. 2017, Soegaard Ballester et al. 2018). While the results may be transferable to behavioral treatment programs, direct measurement would be more beneficial to the Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) community than relying on inferred benefits (Tomlinson et al. 2018). Unfortunately, the access to qualified ABA parent educators is limited for those who live in remote areas, have time constraints to typical working hours and those that do not have qualified professionals in the area (Bloomfield et al. 2019, Ingersoll et al. 2016). Therefore, telehealth can bridge that gap and provide needed service to families who may not have another way to access these services. This may also help serve families who need services in various languages other than what the professionals in their areas speak (Butler and Titus, 2015). There is limited research in this area, yet delivery of services through telehealth is not yet an evidence-based practice (Bearss et al. 2018). It is widely reported that world-wide, there is a shortage of BCBAs to serve the needs of all those who seek the service (Wainer and Ingersoll 2015). Although there has recently been an increase in the research regarding telehealth, the lack of applied research with laypeople exists (Bearss et al. 2018, Benson et al. 2018, Bloomfield et al. 2019). There is also an increase in demand for research regarding telehealth with the current COVID-19 pandemic as services are being disrupted for many families due to social distancing requirements, It is imperative to conduct this research so consumers are provided with effective interventions to make socially significant gains. Lack of research in this area will prohibit recipients from receiving services that are proven to be effective. In addition, delivery of services through telehealth needs to be studied to inform stakeholders and funding sources if these services are effective and warrant coverage.

The current study explores the benefits and efficacy of caregiver training within a telehealth model for implementing a fixed interval schedule of reinforcement using token economy through various household activities or tasks. The token economy was chosen due to the ease in implementation for the participants, as well as being inclusive of densely scheduled reinforcement for their child. The parent was taught skills using behavior skills training (BST). The primary focus was for the parent to provide reinforcement on a fixed schedule of reinforcement and the token economy was a visual way to represent that to both the parent and child. Reinforcement offers a least-restrictive approach to treatment and is required within ABA to be implemented prior to punishment procedures (Cooper et al. 2020). In addition, in ABA punishment procedures must be in a treatment package that includes reinforcement interventions (Cooper et al. 2020). The training package designed for this study provided positive replacement tools for existing punitive methods that were already being utilized within the homes, to better equip participants in working with problem behaviors.

Methods

Participants

Two separate participants (1 male, 1 female) were caretakers recruited from a convenience sample of families receiving services through a private ABA-focused special needs school and clinic within the United States. Mark was of Caucasian ethnicity with English as the primary language. Carol was of Hispanic ethnicity with Spanish as the primary language, and general fluency in English. Both participants were over 30 years of age, married, and employed full-time outside of the home. Mark’s home environment included one child with an ASD diagnosis (6 years of age), the participant’s spouse, and one younger child. Carol’s home environment included one child with an ASD diagnosis (15 years of age), the participant’s spouse, and pets.

Both participants’ met the inclusion criteria of being primary caregivers for children with special needs who had prior experience with environmental token systems of various types (chore charts, token boards), reinforcement contingencies, and whose children met predetermined criteria for inclusion in this study (ability to attend to tasks, non-severe or destructive behaviors, interfering behaviors for completing tasks or remaining on-task, inclusion in center or school-based programs for private ABA center). The caregiver-participants did not have prior formal training on implementation of token systems for use in the home, or with telehealth technology. Both caregiver-participants worked outside of the home during the day, and were primarily responsible for facilitating engagement in homework and household chores after school/work. The participants were included in the study upon agreeing to partake in up to four sessions per week (e.g. baseline: two activity sessions; intervention: two training sessions with the instructor plus activity sessions: fading phase: one session with instructor and activity sessions).

Setting

All sessions took place in the participant's home, with a virtual connection to the instructor in a remote location separate from the participant. All communications were done via email or chat/video conference within WhatsApp. The home setting included various locations within the home (e.g. living room, kitchen, dining room, and workshop).

Video data were collected through two applications offering encryption based on participant preference (WhatsApp and SendSafely). Equipment required for the treatment included existing high-speed internet connection and a video recording device (cell phone). Activity materials included the token board, timers, and participant-chosen activities within and around the respective homes. Participants were directed to choose a range of interactive activities that varied in task difficulty. The range of preference was included to give participants varied exposure to conditional elements and replicate the typical home natural environment.

Research design

A non-concurrent multiple-baseline design across participants was used to determine the effects of caregiver training within a token economy system over a telehealth medium. The study consisted of a 3-week baseline phase, a training intervention phase with variable timeline based on procedural fidelity being reached, and a fading intervention phase for the remainder of the study duration.

Procedure

The instructor provided preference-based materials to each participant consisting of a unique token board design for each child with preferred cartoon characters, relevant token symbols, and known preferred choices of reinforcers for the back-up reinforcer. An instructional email was sent for the first phase which consisted of a hard-copy document overview of the concepts the instructor would be teaching, informed consent papers, the timeline of the study, and contact information to relate any questions or concerns at any time. The instructor scheduled one video conference to answer questions regarding the email content, and to resolve all technical problems prior to the baseline phase.

Baseline: The baseline phase consisted of weekly video-recorded observations of the caregiver interacting with the child in caregiver-chosen activities, with only simple instructions for how long to allow each cycle and break to continue. No preceding ABA instruction or BST was given at this time, so that observers could identify the caregiver implementation process, the children’s behaviors present in the natural environment, and the children’s compliance level in the natural environment. Participants were instructed to implement the token economy, giving one token per 30 s of activity participation, and to give a 5-minute break after the child earned 10 tokens, with no further training or instruction. The participants were not instructed on how to respond to problem behavior, only to give the token for participation. Each video-recorded session was to last 30 min, including token delivery and 5-minute breaks provided each time the child met criteria. Participants were instructed to record and upload the video of the two activity sessions per week. The activities chosen for the dependent variable ranged in preference and included interactive crafting or woodwork in the garage, puzzles, games with the caregiver, household chores such as dishes or laundry, cleaning up toys, baking, and homework (reading or math) completion with the caregiver providing assistance as needed. Caregivers were instructed not to introduce the least-preferred tasks with high likelihood of escalated behavior (homework: reading or math) until training had been provided. Lesser degrees of behavior were still available for observation with the remaining activities through the baseline phase.

Training Intervention: Prior to beginning the intervention phase, the instructor watched the videos and made note of skills targeted for training. Two 30-minute training video conference sessions were conducted in addition to the continued 30-minute activity sessions each week. The instructor met with the caregiver-participants individually via live video call to introduce instruction topics, and practice the concepts through instructor modeling, where roles were established as caregiver (instructor) and child (caregiver) to act out typical responses to demands. Roles were then reversed for caregiver practice where the caregiver acted as implementer and the instructor responded as the child. Feedback was provided to caregivers before the end of each training session based on performance in accordance with the teaching procedure matching the procedural fidelity scoring data sheets. Concluding each role-play, the instructor answered questions from the participant and provided a follow-up summary via email. Caregivers were instructed to provide 1–2 video observations to the secure site prior to the next scheduled training session, for the instructor to observe and analyze fidelity of implementation techniques covered in the previous session.

In the first implementation phase, tokens were given on a fixed interval schedule of 30 s, provided the child was participating in the activity with the absence of predetermined problem behaviors (e.g. noncompliance in the form of vocal protest, physical protest, or no-response) at the end of each interval. Caregivers were instructed to begin the sessions with less aversive activities to build up behavioral momentum through successful responding and vocal praise paired with each token, followed by a 5-minute break of the child’s choice. The caregiver was instructed to prompt the child back to a specific activity with higher compliance likelihood to begin the next cycle, then alternate to a less-preferred or more difficult activity (such as homework), and ensure that the next break was offered on completion of the less-preferred activity. During activities, if the child exhibited undesirable behavior, the caregiver was instructed to pause the timer, facilitate appropriate communication, and redirect back to the task, using behavioral momentum techniques when necessary for more difficult tasks. Immediately upon successful redirection and compliance to the task, the timer resumed and the token with oral praise was given when the timer reached the 30-second alarm. If the child was engaged in problem behavior at the end of the interval, no token was delivered and the interval reset when the child complied to the directive to engage in the task.

Observation videos of the caregiver and child interaction were graded and training intervention continued until the participant reached 90% procedural fidelity through role-play. Mark met the criterion after two role-plays while Carol required three. Both participants maintained treatment fidelity levels over 90% throughout the study.

Fading Intervention: Within the fading phase, the 30-second token interval was increased to 60-seconds. Additionally, the training video conference sessions were reduced to once per week and excluded role-play provided the participant’s remained at or above 80% fidelity throughout activity engagement. Procedural fidelity remained above 80% for both participants, and re-training was not required throughout the remaining training sessions.

Concluding the study, one final video conference session was conducted to discuss transferring the token system to different settings or other caregivers, as well as further fading instruction. Any remaining questions were answered, feedback from overall observation was provided, and the social validity survey was completed.

Measurement

Token economy procedural fidelity was scored via predetermined data sheets, which included observation points within the following categories: appropriately prompting through transitions to activity and break using the token system (+/-, frequency per session), frequency for token adherence (30 s/60s +/-, depending on treatment phase), vocal praise provided with each token (30 s/60s +/-, depending on treatment phase), redirection to activity when appropriate (+/-, frequency per session), break timer adherence (+/-, frequency per session), appropriate prompts for transition back to activities (+/-, frequency per session), and duration of each work session.

Prompt to activity given appropriately was defined as the caregiver prompting the child to join the next activity for the initial start of session, and after each break. Each opportunity was scored + for appropriate prompts (stating “come [join activity],” or “it’s time to [join activity]”), or - for inappropriate (i.e. asking if the child wants to [join activity]) or non-prompt. Prompt to break was defined as the caregiver prompting the child to engage in chosen break activity. Each opportunity was scored + for appropriate prompts (stating “good working, time to [break activity]”), or - for inappropriate (i.e. asking if the child wants to [go to break activity]) or non-prompt. Token adherence was defined as: tokens given/withheld appropriately, wherein tokens were given appropriately within 10 s of the end of the interval, and withheld appropriately during target behavior until criteria for next available token was met. Vocal praise provided with each token was defined as positive verbal feedback provided with each token (e.g. “good reading! Let’s read a little more”) out of available opportunities. Redirection to activity when appropriate was further defined in the data sheet as: verbal redirection during target behavior (i.e. “what are we working for?” or “first let’s read this and get three more tokens, then break.”) out of opportunities to provide redirection (target behavior instances). During verbal redirection, there were no cost-contingencies for behavior (removal of tokens), and any responses other than redirection were recorded as (-) (i.e. threats, punishment, reprimands). Break timer adherence was defined as the caregiver setting the timer for 5 min during chosen break activity, and following through with return to activity at alarm sounding. Each opportunity was scored + for appropriate timer adherence, or - for inappropriate (i.e. not setting timer or not following through with return to task).

Interobserver agreement

Observers were trained in correct implementation of the token economy procedure utilizing one baseline session until Interobserver agreement (IOA) reached 95%. IOA was then conducted within activity sessions for 20–30% of each phase and reported at an average of 93.29% (range 84%-100%) for Mark, and 95.15% (range 90%-100%) for Carol. Treatment integrity was analyzed through the training phase to ensure treatment was delivered at 90% fidelity. Treatment integrity was scored on the following components: cordial greeting to participants, positive feedback from activity video, constructive feedback/coaching given in understandable behavioral terms, questions prompted and answered, role-play session administered, feedback for role-play (in-the-moment or directly following), and cordial dismissal prior to ending the call. Overall treatment integrity averaged 92.86% for Mark and 100% for Carol; therefore, no retraining was necessary throughout the phased implementation.

Social validity

Participants completed surveys prior to and after the training which included social validity questions surrounding the current state of interaction between the participant and the child via a 1–5 point Likert scale. Questions focused on participant perceptions of how the child’s behavior affected daily life and the participant’s ability to participate in various activities inside and outside of the home. Closing interviews with participants addressed the perceived value of the training through questions regarding confidence and ability to maintain the token system going forward.

Results

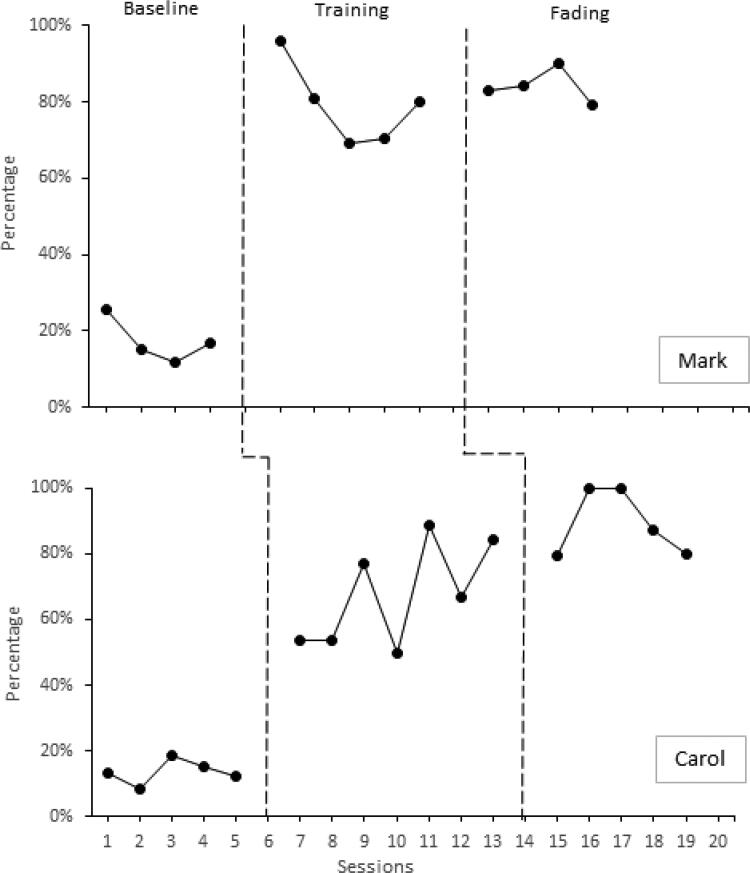

Baseline data showed steady responding for both participants at an average implementation accuracy of 17.41% for Mark and 13.45% for Carol. During the training intervention phase there was a rapid increase in implementation accuracy for both participants. Mark averaged 81.98% at the beginning of the training phase with an average of 75.23% at the end of training. Carol averaged 58.52% at the beginning of the training with an increase to 80% average at the end of the training phase. Mark’s accuracy through fading averaged 84.08%, while Carol’s accuracy averaged 89.3% (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Token economy accuracy per session through a telehealth training medium.

Social validity is an important aspect often neglected in research, yet important in obtaining buy-in from caregivers and the community when designing treatment programs for individuals with autism (Snodgrass et al. 2018). The social validity component is especially important for transitioning these services to caregiver implementation beyond the professional services provided. Social validity measures included in this study showed a decrease in perceived disruption to family activities, an increase in ability to interact with the child through a range of preferred and non-preferred activities, and confidence in continuing the token system. Both participants noted continued and expanded use of the token economy beyond the recorded sessions with positive results in responding from the respective children. Participants both reported convenience and ease of scheduling as benefits to the telehealth medium over in-home scheduled training. Both participants also concluded that they would participate again in online caregiver training opportunities.

Discussion

Results from this study were consistent with prior telehealth and caregiver training results within autism and behavioral treatment (Bearss et al. 2018, Boisvert and Hall 2014, Ingersoll and Berger 2015, Suess et al. 2014, Vismara et al. 2013). Despite variability in the level of change from baseline to treatment, both participants responded with definitive increases in accuracy for implementing the token economy through the treatment phase. The accuracy in implementation was maintained once the training role-play and review components were removed; however, minor fluctuation in accuracy through this maintenance phase indicate that further observation would be needed to conclude that results would continue at treatment levels over extended periods. These initial results, however, do indicate that the telehealth medium is feasible for teaching caretakers how to implement a token economy for at-home use.

One explanation for the different levels of change in baseline to treatment accuracy between Mark’s and Carol’s results was attributed to consistency and repetitive practice. Carol was consistent with adhering to two activity sessions and two training calls per week, whereas Mark was often limited to single activity and training sessions per week due to scheduling conflicts or illness. Carol incorporated the token economy into household activities, through illnesses and scheduling adjustments. Without further study, it is not possible to conclusively determine if the difference in change was due to the higher consistency, differences in family dynamic, or other extraneous variables.

Although maintenance data were unavailable for formal review, a 6-month follow-up call with both participants revealed that Mark’s family had not received prior structured ABA services beyond the summer camp sessions at the clinic, and Mark stated that this exposure to ABA techniques and the visible outcomes from the study was a catalyst to beginning in-home services. Mark further elaborated that the son was now able to perform any level of work with minimal undesirable behaviors shown before, and was now excelling in school andsocially. Mark also reported that he was able to fade out of the token system completely through the in-home services. Carol’s response to follow-up was similar, in that the child regularly interacted with the caregivers in activities and around the community without previous undesirable behaviors following the study. Carol was able to continue using the token system across varied new activities with confidence and self-reported success. Carol stated eagerness to participate in any future training available to caregiver families to help support positive interactions with their children.

One of the more important components of the training package, both for providing a better understanding of ABA methods and for social validity factors, was educating participants on the value of reinforcement versus punishment. Mark had a lower threshold for frustration with problem behavior and would often resort to reprimands, threats, or punishment. In teaching Mark why and how to use reinforcement prior to problem behavior or upon successful redirection to task, Mark stated that he had much more patience when working through problem behaviors. Mark cited the most important benefit of this training being his child’s excitement in participating in activities after implementing the token system (where any shared activities prior were major points of contention). Carol was also very interested in learning why and how to use reinforcement appropriately. She was able to apply the instruction relatively quickly and successfully, which showed through the interactions within activities, where her son had higher levels of on-task behavior and showed more excited interest in the activities and interactions. Carol was especially looking forward to continuing the token system with more frequent use throughout the week, as well as with activities outside of the home (e.g. dog-walking, car trips, shopping outings).

Limitations

There were some limitations of this study. Primarily, controlling for extraneous variables within the home setting presented challenges (e.g. interruptions from other family members, environmental mishaps, child medication lapses/changes, illness, and activity or equipment difficulties). There was a time-delay between the procedure and the feedback with BST and implementation errors could occur over time. The ability to reschedule missed activity and video conference sessions was limited due to time constraints. While live-training may be more effective in countering these limitations, telehealth specifically reaches underserved populations within the ASD community where in-person services are not as readily available (Boisvert and Hall 2014, Ingersoll and Berger 2015, Kuravackel et al. 2017, Vismara et al. 2013). The second limitation was with regard to the technological aspect. The technology available is still emerging and, while there are more robust platforms available within a paid corporate healthcare system (e.g. dedicated servers, more expansive recording systems, and proprietary software), free or lower-cost platforms are not readily available to the general public at this time. The technology used within this study did present some technical difficulties which disrupted the fluidity of collecting and observing session data. These difficulties, although minor, could detract from perceived convenience benefits of a telehealth form of service delivery. Furthermore, currently available technology does not readily include the ability to record video conference calls for quality assurance (i.e. additional software components were required to include this feature). For official telehealth methods to be effective, these points would need to be addressed to ensure a truly convenient and consistent model. Most importantly, since IRB approval for child data were not obtained, therefore, that was not collected nor reported other than through parent report.

Additional limitations included the lack of instruction in baseline on how to respond to problem behavior. The participants were simply told to give a token for engagement in the activity with no direction on how to redirect the child should problem behavior occur. Lastly, this study was limited to a convenience sample for recruitment and known peers for observation and scoring. Ideally, it would be preferable to have a broader scope to draw from for participants and blind observers for collecting data and scoring IOA, as well as multiple trained instructors to provide treatment instruction for comparison and repeatability. Further benefits to this study could have been achieved through follow-up procedural checks beyond the final phase to ensure that results maintained over time.

Future research

Future research should investigate whether the number of sessions per week affects accuracy in implementation of the token system within the telehealth medium. Observing the implementation through a single-case design over alternating number of sessions per week would offer conclusive answers to whether the change in accuracy was due to consistency in sessions vs. external variables. Future research expanding upon this study should explore the methods available for fading of the implemented token system once successful compliance has been achieved over time. The ultimate goal of any behavior plan is to acquire the highest potential of independence and live without interventions. With this understanding, more extensive structured fading would be a necessary component for any token system implemented to achieve this result. Additionally, it would be interesting to see how real-time training affects accuracy of implementation through use of an in-ear device or the video-conference system. Real-time training may relieve errors compounded over time due to the time-delay structure of the current study, and would provide in vivo learning opportunities directly with the child rather than solely learning through role-play.

Future research should also include the transition of a token system to a self-management system led by caregiver-participants. Self-management has been shown to increase performance quality and frequency with non-preferred tasks (Falkenberg and Barbetta 2013), and decrease problem behaviors (Axelrod et al. 2009). Self-management increases the level of independence for the individual which is the ultimate goal within any ABA intervention (Koyama and Wang 2011). With regard to social validity, self-management also may increase quality of life for the immediate family members responsible for the individual, and the ability to self-manage may increase potential employment and academic opportunities for that individual. One of the children showed continued interest in the token process which could be transitioned to self-monitoring with training from the caretaker.

Another possible direction for future research would be to explore how the token system implemented within this study might generalize across different implementing persons other than caregivers (e.g. caregivers vs. teachers, caregivers vs. employers). Depending on the level of ability within the individual, tokens could be adjusted to more societally available tokens such as money or points toward time off. This translation may be effective as a generalization tool into adaptive living situations for those transitioning from in-home care to residential facilities which offer employment opportunities within the community, again increasing potential for independence.

Finally, future research should explore caregiver training for other ABA methods. Crisis prevention through antecedent manipulations, reinforcement methods versus punishment, and how to successfully complete community outings are all common challenges faced by caregivers of children with ASD and special needs. The telehealth connection and video recording or conferencing technology could be useful with any of these topics to help provide socially meaningful tools for caregivers to be able to interact with their children in a variety of settings and situations. Providing training that encompasses daily life and interactive points has the strongest possibility for promoting generalization, and brings the caregivers one step closer to enjoying positive family-life balance.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dorothy Kim for supporting this research and conducting IOA, Suhad Abdallah for inspirational support, Sarah Russell for reviewing the paper prior to submission and the Sage Colleges for devoting resources to the thesis track program. We would also like to thank, our “anonymous reviewer one” for the excellent feedback to improve the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflicts of interests to declare.

References

- Antezana, L., Scarpa, A., Valdespino, A., Albright, J. and Richey, J. A.. 2017. Rural trends in diagnosis and services for autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod, M. I., Zhe, E. J., Haugen, K. A. and Klein, J. A.. 2009. Self-management of on-task homework behavior: A promising strategy for adolescents with attention and behavior problems. School Psychology Review, 38, 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Bagayoko, C. O., Traoré, D., Thevoz, L., Diabaté, S., Pecoul, D., Niang, M., Bediang, G., Traoré, S. T., Anne, A. and Geissbuhler, A.. 2014. Medical and economic benefits of telehealth in low- and middle-income countries: Results of a study in four district hospitals in mali. BMC Health Services Research, 14, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearss, K., Burrell, T. L., Challa, S. A., Postorino, V., Gillespie, S. E., Crooks, C. and Scahill, L.. 2018. Feasibility of parent training via telehealth for children with autism spectrum disorder and disruptive behavior: A demonstration pilot. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 1020–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearss, K., Johnson, C., Smith, T., Lecavalier, L., Swiezy, N., Aman, M., McAdam, D. B., Butter, E., Stillitano, C., Minshawi, N., Sukhodolsky, D. G., Mruzek, D. W., Turner, K., Neal, T., Hallett, V., Mulick, J. A., Green, B., Handen, B., Deng, Y., Dziura, J. and Scahill, L.. 2015. Effect of parent training vs parent education on behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 313, 1524–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson, S. S., Dimian, A. F., Elmquist, M., Simacek, J., McComas, J. J. and Symons, F. J.. 2018. Coaching parents to assess and treat self-injurious behaviour via telehealth. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: JIDR, 62, 1114–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield, B., Fischer, A., Clark, R. and Dove, M.. 2019. Treatment of food selectivity in a child with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder through parent teleconsultation. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 121, 33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert, M. and Hall, N.. 2014. The use of telehealth in early autism training for parents: A scoping review. Smart Homecare Technology and TeleHealth, 2014, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bounthavong, M., Pruitt, L. D., Smolenski, D. J., Gahm, G. A., Bansal, A. and Hansen, R. N.. 2018. Economic evaluation of home-based telebehavioural health care compared to in-person treatment delivery for depression. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 24, 84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, A. M. and Titus, C.. 2015. Systematic review of engagement in culturally adapted parent training for disruptive behavior. Journal of Early Intervention, 37, 300–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr, T., Shih, W., Lawton, K., Lord, C., King, B. and Kasari, C.. 2016. The relationship between treatment attendance, adherence, and outcome in a caregiver-mediated intervention for low-resourced families of young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 20, 643–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, N. G., Marti, C. N., Bruce, M. L., Hegel, M. T., Wilson, N. L. and Kunik, M. E.. 2014. Six-month postintervention depression and disability outcomes of in-home telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed, low-income homebound older adults. Depression and Anxiety, 31, 653–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E. and Heward, W. L.. 2020. Applied behavior analysis. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson/Merrill-Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Falkenberg, C. A. and Barbetta, P. M.. 2013. The effects of a self-monitoring package on homework completion and accuracy of students with disabilities in an inclusive general education classroom. Journal of Behavioral Education, 22, 190–210. [Google Scholar]

- Iadarola, S., Levato, L., Harrison, B., Smith, T., Lecavalier, L., Johnson, C., Swiezy, N., Bearss, K. and Scahill, L.. 2018. Teaching parents behavioral strategies for autism spectrum disorder (ASD): Effects on stress, strain, and competence. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 1031–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, B. and Berger, N. I.. 2015. Parent engagement with a telehealth-based parent-mediated intervention program for children with autism spectrum disorders: Predictors of program use and parent outcomes. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17, e227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, B., Wainer, A. L., Berger, N. I., Pickard, K. E. and Bonter, N.. 2016. Comparison of a self-directed and therapist-assisted telehealth parent-mediated intervention for children with ASD: A pilot RCT. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 2275–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama, T. and Wang, H.. 2011. Use of activity schedule to promote independent performance of individuals with autism and other intellectual disabilities: A review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 2235–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, C. S., Krowski, N., Rodriguez, B., Tran, L., Vela, J. and Brooks, M.. 2017. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open, 7, e016242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuravackel, G. M., Ruble, L. A., Reese, R. J., Ables, A. P., Rodgers, A. D. and Toland, M. D.. 2017. COMPASS for hope: Evaluating the effectiveness of a parent training and support program for children with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2018, 404–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langabeer, J. R., Champagne-Langabeer, T., Alqusairi, D., Kim, J., Jackson, A., Persse, D. and Gonzalez, M.. 2017. Cost-benefit analysis of telehealth in pre-hospital care. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 23, 747–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren, S., Wacker, D., Suess, A., Schieltz, K., Pelzel, K., Kopelman, T., Lee, J., Romani, P. and Waldron, D.. 2016. Telehealth and autism: Treating challenging behavior at lower cost. Pediatrics, 137, S167–S175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConachie, H., Randle, V., Hammal, D. and Couteur, A. L.. 2005. A controlled trial of a training course for parents of children with suspected autism spectrum disorder. The Journal of Pediatrics, 147, 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Baio, J., Washington, A., Patrick, M., DiRienzo, M., Christensen, D. L., Wiggins, L. D., Pettygrove, S., Andrews, J. G., Lopez, M., Hudson, A., Baroud, T., Schwenk, Y., White, T., Rosenberg, C. R., Lee, L.-C., Harrington, R. A., Huston, M., Hewitt, A., Esler, A., Hall-Lande, J., Poynter, J. N., Hallas-Muchow, L., Constantino, J. N., Fitzgerald, R. T., Zahorodny, W., Shenouda, J., Daniels, J. L., Warren, Z., Vehorn, A., Salinas, A., Durkin, M. S. and Dietz, P. M.. 2020. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years —Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 69, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polinski, J. M., Barker, T., Gagliano, N., Sussman, A., Brennan, T. A. and Shrank, W. H.. 2016. Patients' Satisfaction with and Preference for Telehealth Visits. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31, 269–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray, D. E. and Topol, E. J.. 2016. State of telehealth. The New England Journal of Medicine, 375, 154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suess, A. N., Romani, P. W., Wacker, D. P., Dyson, S. M., Kuhle, J. L., Lee, J. F., Lindgren, S. D., Kopelman, T. G., Pelzel, K. E. and Waldron, D. B.. 2014. Evaluating the treatment fidelity of parents who conduct in-home functional communication training with coaching via telehealth. Journal of Behavioral Education, 23, 34–59. [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass, M. R., Chung, M. Y., Meadan, H. and Halle, J. W.. 2018. Social validity in single-case research: A systematic literature review of prevalence and application. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 74, 160–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soegaard Ballester, J. M., Scott, M. F., Owei, L., Neylan, C., Hanson, C. W. and Morris, J. B.. 2018. Patient preference for time-saving telehealth postoperative visits after routine surgery in an urban setting. Surgery, 163, 672–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppo, J. and Floyd, K.. 2012. Parent training for families who have children with autism: A review of the literature. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 31, 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, S. R., Gore, N. and McGill, P.. 2018. Training individuals to implement applied behavior analytic procedures via telehealth: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Behavioral Education, 27, 172–222. [Google Scholar]

- Vismara, L. A., McCormick, C., Young, G. S., Nadhan, A. and Monlux, K.. 2013. Preliminary findings of a telehealth approach to parent training in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2953–2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainer, A. L. and Ingersoll, B. R.. 2015. Increasing access to an ASD imitation intervention via a telehealth parent training program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 3877–3890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]