Abstract

Drosophila provides a powerful genetic system and an excellent model to study the development and function of the nervous system. The fly’s small brain and complex behavior has been instrumental in mapping neuronal circuits and elucidating the neural basis for behavior. The fast pace of fly development and the wealth of genetic tools has enabled systematic studies on cell differentiation and fate specification and has uncovered strategies for axon guidance and targeting. The accessibility of neuronal structures and the ability to edit and to manipulate gene expression in selective cells and/or synaptic compartments has revealed mechanisms for synapse assembly and neuronal connectivity. Recent advances in single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) have further enhanced our appreciation and understanding of neuronal diversity in a fly brain. However, due to the small sizes of the fly brain and of its constituent cells, the scRNA-seq methodologies require a few adaptations. Here we describe a set of protocols optimized for the scRNA-seq analysis of Drosophila larval ventral nerve cord (VNC), starting from tissue dissection and single cell dissociation to cDNA library preparation, sequencing and data analysis. We apply this workflow to three separate VNC samples and detail the technical challenges associated with successful application of scRNA-seq to studies on neuronal diversity. The accompanying manuscript presents a custom multistage analysis pipeline that integrates modules contained in different R packages to ensure high-flexibility, high-quality RNA-seq data analysis. These protocols are developed for Drosophila larval VNCs but could easily be extended to other tissues and model organisms.

Introduction

The proper function of any tissue of a multicellular organism is achieved through division of labor: different kinds of cells work in concert to perform different tasks. In many cases the number of different types of cells and how we define these cells and their contributions are still open questions. The longstanding quest to identify and define cellular diversity has been particularly challenging for neurobiologists due to the complexity and diversity of the nervous system. In recent years, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as a promising approach to tackle this problem, since transcriptional profiling at the cellular level provides a comprehensive landscape of the cell types within different regions of the brain and at various developmental stages. Moreover, the scRNA-seq data are connecting together neuroscience, computational biology and systems biology together, opening new opportunities to decipher the complexity of cell types, and their connectivity and functions within the nervous system (Li et al., 2019; Mu et al., 2019; Poulin et al., 2016; Wolbert et al., 2020).

ScRNA-seq technologies can be classified in two groups based on (1) full-length or (2) partial transcript coverage. Methodologies that achieve full-length transcript coverage include Smart-seq (Picelli et al., 2013; Ramskold et al., 2012), Quartz-seq (Sasagawa et al., 2013), and MATQ-seq (Sheng et al., 2017). Other technologies only capture and sequence the 3’-end of the transcript, for example Drop-seq (Macosko et al., 2015), InDrop (Klein et al., 2015), Chromium (Zheng et al., 2017), and Quartz-Seq2 (Sasagawa et al., 2018), or only the 5’-end, such as STRT-seq (Islam et al., 2011, 2012). The latest improvements in scRNA-seq technologies allow these to be scaled up to thousands of cells per experiment, opening the door for comprehensive analysis of cellular diversity (Prakadan et al., 2017; Svensson et al., 2018).

The Drosophila central nervous system (CNS) offers an excellent system to investigate the diversity of neuronal cell types in relationship either to their transcriptomes in adult animals or during earlier developmental stages. By the time the fly embryos hatch into the first larval stages, their CNS, consisting of two brain lobes and ventral nerve cord (VNC), has an estimated 10,000 cells (Scott et al., 2001) that expand to 100,000 cells in the adult brain (Kremer et al., 2017). Hundreds of neuronal types have been described based on the morphology of their projections, connectivity with other neurons, or their function in controlling a particular behavior (Berck et al., 2016; Eichler et al., 2017; Ohyama et al., 2015; Robie et al., 2017; Takemura et al., 2017a; Takemura et al., 2013; Takemura et al., 2017b; Tobin et al., 2017). However, the molecular features underlining these different cell types remain poorly understood. In recent years, single-cell RNA-seq approaches have been applied towards studies on cellular diversity in the Drosophila first instar larval brain (Brunet Avalos et al., 2019) or in adult central brain and nerve cord (Allen et al., 2020; Croset et al., 2018; Davie et al., 2018; Konstantinides et al., 2018). We and others are working toward describing the cellular complexity of the Drosophila third instar larval brain. Efforts to assemble comprehensive fly brain atlases are well under way, but they will only lay the foundation for studies that will utilize transcriptome analyses to address fundamental questions in neurobiology.

Here we describe a set of protocols for the isolation and dissociation of cells from Drosophila larval VNCs, single cell capture and preparation of cDNA libraries, sequencing and the initial processing of the raw sequencing data:

BASIC PROTOCOL 1.

Dissection of larval ventral nerve cords and preparation of single-cell suspensions

BASIC PROTOCOL 2.

Preparation and sequencing of single cell transcriptome libraries

BASIC PROTOCOL 3.

Align raw sequencing data into the Drosophila genome and generate count matrix.

In the accompanying paper, we analyze the resulting scRNA-seq data using a custom multistage analysis pipeline that integrates modules contained in different R packages to ensure high-flexibility, high-quality RNA-seq data analysis. Overall, these protocols serve as a guide through all the steps required to conceive and perform a single cell RNA-seq analysis using the larval VNC as an example. Nonetheless, the principles and the methodologies presented here can be easily expanded to any tissue of interest and beyond the Drosophila model system.

Strategic planning

To successfully embark in scRNA-seq using a 10X Genomics Chromium platform it should be noted that this method samples only a small proportion of the total transcript pool from each cell. One challenge will be to preserve the initial abundance of mRNA and to identify rare transcripts. It is critical that the investigators (i) minimize stress by keeping cells on ice as much as possible, (ii) minimize cells shearing during dissociation and (iii) minimize the time from tissue dissection and dissociation to subsequent preparation of cDNA libraries. Also, this method only reads a 3’UTR fragment and therefore cannot capture various isoforms. (There is one exception; isoforms with different 3’UTR can be differentiated by 10X Chromium, but first, the custom reference genome needs to be annotated to include the 3’UTR sequences and the corresponding transcripts.) One should plan on sequencing as many cells as possible to increase identification and definition of various cell clusters. Due to the significant cost of these analyses, one cannot usually plan for triplicate experiments for each genotype of interest.

At the beginning of scRNA-seq studies, we recommend investing in three control samples and introducing useful markers in one or two of these control samples. For example, transgenes and/or reporters can probably be found (or built) to mark subsets of cells of interest. A control genotype marked by various transgenes is still a control, but be mindful of the genetic background (see below). In addition, the presence of the marked cells could provide information about the presence and the representation of cells of interest in the dissociated mixture. FACS sorting of fluorescently marked cells will further enhance identification and characterization of these cell types. Please keep in mind that most of the available UAS-GFP and UAS-RFP transgenes share the same (Drosophila actin) 3’UTRs; in this case, FACS sorting will distinguish between GFP- or RFP-marked cells, but sequencing will not, as the 3’UTR sequencing reads will be identical.

When selecting the genotypes for the scRNA-seq experiments you should also be aware that different genetic backgrounds (especially when combined with stressed cells) can result in highly variable transcriptomes. This variability may distort subsequent analyses for clustering and identification of different cell types and thus preclude comparisons between samples. Later data mining analyses will greatly benefit from early efforts to backcross mutants of interest into a similar (preferably isogenized) genetic background and/or to mark selective cell populations with various reporters

BASIC PROTOCOL 1.

Dissection of larval ventral nerve cords and preparation of single-cell suspensions

The main goal of this protocol is to isolate the tissue of choice and prepare high-quality single cell suspensions. The condition of the cells and the quality of their RNAs are critical for efficient cell capture and encapsulation in droplets and for the generation of cDNA libraries. Incomplete cell dissociation may result in cells stuck together and will trigger their removal during the quality check stages. Harsh dissociation may damage cells and cause RNA degradation and RNA leakage. Finding the right balance is particularly challenging when working with neurons, which have long axons that are severed during this process.

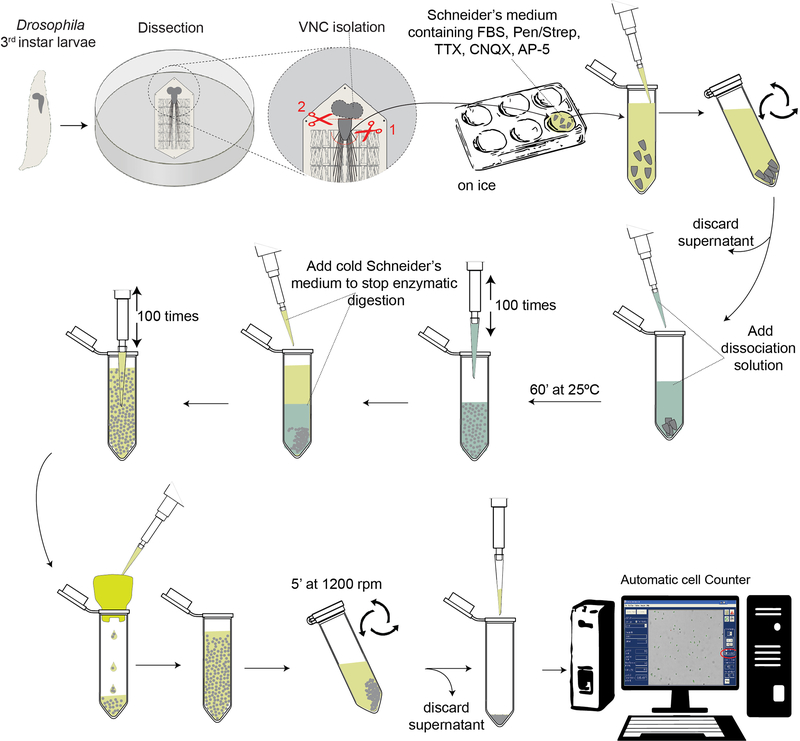

Here we describe the dissection of live tissues, the larval ventral nerve cords, and their dissociation into fresh viable single cells using mechanical and enzymatic treatment. The tissue dissections are usually performed in non-sterile conditions, but all the solutions should be prepared using nuclease-free reagents and sterile media to minimize cell damage and contamination. Various cocktails of enzymes, which include trypsin, papain, collagenase and liberase, can be used to dissociate live tissues (Lafzi et al., 2018). For the larval VNC, we have selected collagenase and liberase and have optimized the enzyme concentrations, the temperature and duration of enzymatic digestion, and the extent of trituration so that single-cell suspensions can be prepared without significant disruption of cell integrity. The steps of this protocol are diagramed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the Drosophila larval ventral nerve cord dissociation workflow

Dissect wandering third instar Drosophila larvae, excise the VNCs and immediately immerse them in ice-cold Schneider’s medium supplemented with toxins (TTX, CNQX, AP-5) to inhibit neuronal firing. When all the VNCs are collected, initiate tissue dissociation by incubation with enzymes and follow up by mechanical disruption via trituration. Filter the dissociated cells to remove any remaining cluster, concentrate the cells and check their number and quality and viability.

A more complete discussion on best practices and general protocols for washing, counting and concentrating cells from both abundant and limited cell suspensions can be found in the 10X Genomics manual, Cell Preparation Guide:

Materials:

Bright field stereomicroscope

Fluorescence stereomicroscope

25°C shaking incubator

4°C table-top centrifuge

Tweezers (World Precision Instruments, Dumont Tweezers #5; cat. no. 14098)

Fine scissors (World Precision Instruments, Vannas Scissors, 8.5 cm; cat. no. 501232)

Jazz-Mix Fly food (Thermo Fisher; cat. no. AS153)

Fly vials

35mm petri dish

9-well glass depression slides

Sylgard plates (see Reagents and Solutions)

Insect pins

Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), no calcium, no magnesium (Thermo Fisher Scientific; cat. no. 14190136)

Schneider’s medium supplemented with toxins (see Reagents and Solutions)

Bovine Serum Albumin (Sigma Aldrich; cat. no. A9647)

30 μm pre-separation filters (Miltenyi Biotec; cat. no. 130–041-407)

2 mL RNase-free tubes (Thermo Fisher Scientific; cat. no. AM12475)

Pipettes and pipette tips (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 1000 μL barrier wide bore pipette tip, cat. no. 2079G; 200 μL barrier pipette tip, cat. no. 2069–05; 20 μL barrier pipette tip, cat. no. 2149P-05)

Trypan Blue (Life Technologies; cat. no. T10282)

Cellometer Cell Counting slide

Rear and collect the larvae of interest

-

1

Grow flies of the selected genotypes in vials with food at 25°C in a standard fly incubator.

Use your favorite Drosophila food recipe or commercial source. We prefer to cook our own food using Jazz-Mix (Thermo Fisher; cat. no. AS153). Please note that food made with this mix tends to become soupy at high larvae density, especially during humid periods. You could try to compensate by (slightly) reducing the amount of water utilized.

-

2

Collect third instar larvae just wandering out of food; these should be towards the end of the third instar stage, ~120 hours after egg laying at 25°C.

Our protocol describes analysis of wandering third instar larvae, but the same methodology could be applied to other developmental stages of interest.

-

3

Transfer larvae to a 35 mm Petri dish with DPBS (without Ca2+ and Mg2+) and wash them to remove any remaining food.

-

4

When needed, genotype larvae using visible dominant phenotypes, such as Bc (Black cells), or various fluorescent markers.

Dissect larvae and isolate ventral nerve cords

For the next steps you will need a bright field stereoscope. Nearby, place a depression slide/ tissue culture dish with Schneider’s medium supplemented with toxins on ice for the collection of samples.

To inhibit the firing of the neurons during cell dissociation, the Schneider’s medium should be supplemented with the following toxins: Tetrodotoxin (TTX)- a sodium channel blocker, D(−)-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (AP-5)- an NMDA receptor antagonist, and 6-Cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX)- an AMPA/Kainate receptor antagonist (Israel et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011).

-

5

Place a clean larva in a Sylgard covered dish; add a drop of ice-cold DPBS.

-

6

Orient larvae with dorsal side up, so you are looking at the two dorsal trachea trunks.

Pin down the anterior and the posterior ends the larvae.

These first steps are common to larval dissection for NMJ studies as previously described (Brent et al., 2009).

-

7

Using fine scissors, make an incision perpendicular to dorsal trunks close to the posterior spiracles. Next, open up the larva longitudinally, cutting between the dorsal trunks; start from the bottom and work your way to the head. Gently lift up the scissors in the anterior area to avoid cutting the brain. Expose the mouth hooks.

-

8

Use tweezers to gently pull out the mouth hooks with one hand while severing the motor neuron axons with scissors in the other hand.

This will separate the brain together with a few more anterior parts away from the larval body.

Do not pull the mouth hooks too much or too fast to minimize the stretching of the motor neuron axons (and their stimulation).

While still holding the mouth hooks, do a second cut just below the brain lobes to separate the ventral nerve cord (VNC). Pick up the VNC using a motor neuron bundle and move it into the iced dish. Gently push the VNC down to the bottom of the well with the tweezers.

You may need to remove fragments of fat body and discs and clean up the larval brain before gaining clear access to the VNC.

-

9

Isolate the rest of the VNCs as described above and collect all VNCs for one genotype in one depression well.

We collect ~30 VNCs per genotype to prepare a single-cell suspension of the entire VNC. This number represents an 8–10 fold excess over what is actually needed for library generation and sequencing. However, in our hands, the success of the cell dissociation step is highly variable when starting with less material.

Should you need to FACS sort your cells and enrich your sample for a particular cell population(s), you will have to scale up the dissection and perform a pilot experiment to estimate the recovery rate.

-

10

Transfer all dissected VNCs for one genotype to a 2 ml non-stick RNase-free tube using a 1 ml pipette tip (barrier wide bore pipette tip) pre-rinsed with 1% BSA in PBS.

In the interest of time and to further minimize experimental variability we perform the VNC dissections in a team of three: Each contributor dissects 10 VNCs per genotype. These are pooled together in one sample/ genotype. We allocate ~45 minutes for the dissection and pooling of VNCs for one genotype.

The dissected VNCs can be stored on ice in supplemented Schneider’s medium for up to 3 hours before proceeding to cell dissociation. Consequently, we usually organize our experiments in sets of four genotypes that are processed together starting from the cell dissociation steps.

Dissociate the cells

-

11

Spin down the VNCs-containing tubes at 1200 rpm for 5 minutes in a table-top centrifuge maintained at 4°C. Remove the supernatant.

-

12

Add 1 ml of 1X cell dissociation solution in each tube (800 μl of 1X Collagenase/Dispase plus 200 μl of 1X Liberase).

The cell dissociation efficacy is strongly affected by the quality of these enzymes. First, please be aware that these enzymes have a relatively short shelf live (about 3 months), even when reconstituted and stored correctly; you should buy them when you are ready to run the experiment. Secondly, the working solutions must be prepared and combined just before the cell dissociation step.

-

13

Incubate samples for 60 minutes at 25°C.

-

14

Triturate samples by gently pipetting up and down ~ 200 times using a 1 ml pipette tip rinsed with 1% BSA. Avoid making bubbles.

To minimize stress, the cells should be kept on ice as much as possible. Work gently to minimize shearing during dissociation.

Following this first round of trituration, no tissue clusters should be visible under the microscope. If tissue clusters are still visible, continue for an additional ~ 100 cycles until you achieve proper cell dissociation.

Trituration is a harsh, mechanical step that may drastically alter the quality and viability of the dissociated cells. Keep it to the minimum possible and stop as soon as cell clusters are no longer observed.

-

15

Stop the enzymatic activity by adding 1 ml ice-cold Schneider’s medium to the tubes. Mix and triturate for another 100 cycles.

Filter the cells to remove any remaining clumps

-

16

In preparation for cell filtration, pre-wash 30 μm pre-separation filters (Miltenyi Biotec; cat. No. 130–041-407) with ice-cold Schneider’s medium.

-

17

Filter the triturated cells and collect them in fresh 2ml non-stick RNase-free tubes.

-

18

Centrifuge the tubes at 1200 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C. Remove excess media without disturbing the cell pellet.

-

19

Adjust the final volume to 100 μl and resuspend the cells by pipetting ~ 100 times. The tubes should be placed on ice and rushed to loading onto the 10X Chromium.

The preferred buffer for final resuspension of the cells is 1x PBS + 0.04% BSA, but other buffers are acceptable.

To the maximum extent possible, you should minimize the time from removing the tissue to dissociation to loading onto the 10X Chromium. To accomplish this goal, in one day of experiments we process samples from four distinct genotypes (~ 3 hours). The entire workflow, from isolating the ventral cords, to cell dissociation and loading onto the 10X Chromium, takes about five hours.

BASIC PROTOCOL 2.

Preparation and sequencing single cell transcriptome libraries

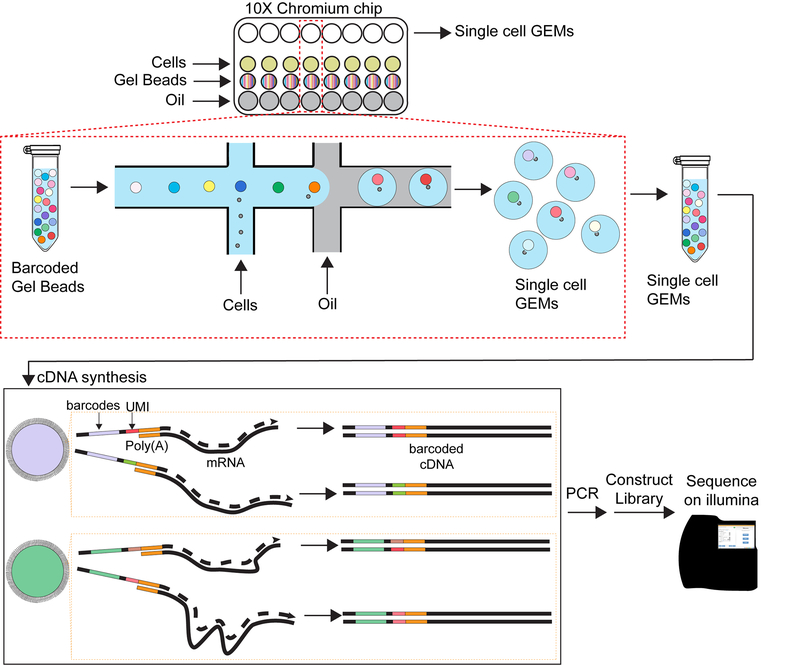

This protocol converts the transcripts of individual cells produced in Basic Protocol 1 into libraries suitable for sequencing in an Illumina sequencer. The cell suspension is added to a solution containing various reagents that enable reverse transcription. This is loaded onto a chip along with a suspension of beads in a solution that contains lysis buffer. The beads contain oligonucleotides with oligo-dT, cellular barcodes and unique molecular identifier (UMI). The cells are combined with the beads into small droplets in oil to form an emulsion. Every droplet contains a bead, but only a few percent of droplets contain a cell. The information encoded on each bead allows labeling of a transcript with a barcode corresponding to the cell from which it was derived and a UMI to differentiate it from other transcripts from the same cell. The formation of the droplet emulsion takes place inside the 10X Chromium machine.

Once the emulsion comes out of the 10X Chromium processor, it is immediately put into a thermocycler to perform the reverse transcription reaction. Subsequent steps convert the single stranded cDNA into a sequenceable library. It is important to note that the standard library preparation only contains a fragment from the distal 3’UTR of each transcript. Also, this method only samples a small proportion of the total transcript pool of each cell. These are important considerations in processing and interpreting data from this protocol.

There are many methods for preparing libraries from individual cells. The field of single cell sequencing is evolving rapidly. Currently, 10X Genomics Chromium is the most popular method in use with large throughput of cells and a lower sequencing cost per cell (Ding et al., 2020; Mereu et al., 2020). This is the method that is described in this protocol (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic of 10X Chromium platform

Load the cell suspension and barcoded beads onto the 10X Chromium chip in lysis buffer. Cells and beads are combined into nanoliter-scale oil droplets to form an emulsion (called Gel bead-in emulsion). The single cell GEMs are immediately carried through reverse transcription reaction and PCR amplification. The resulting libraries are sequenced on an Illumina platform.

In general, it is not viable or advisable to try to combine reagents or harvest more droplets than intended for the 10X kits. You will find there are certain reagents and solutions that seem to be in excess, but everything is carefully calibrated and validated to work together.

Materials:

Cell suspension from Basic Protocol 1

10X Genomics Chromium Single Cell Processor

Cell Counter (Nexcelom, Cellometer Auto T4 Bright Field Cell Counter)

Thermocycler with a deep-well capacity that can efficiently heat samples with 100 μl volume (Bio-Rad C1000 Touch 96-Deep Well Reaction Module; cat. no. 1851197)

Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (cat. no. G2943CA)

Agilent Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA kit (cat. no. 5067–4626)

Illumina DNA Sequencer (HiSeq2500)

10X Genomics Reagent kit (Chromium™ Single Cell 3’ Library & Gel Bead Kit v2, 4 rxns; cat. no. 120267)

10X Genomics Chip kit (Chromium™ Single Cell A Chip Kit, 16 rxns; cat. no. 1000009). This consists of two chips, each capable of running up to 8 samples. The chips are single use only.

10X Genomics multiplex index kit (Chromium™ i7 Multiplex Kit, 96 rxns; cat. no. 120262). This is used for adding indexes on to each sample so multiple samples can be combined into the same sequencing run.

10X Genomics Vortex Adapter (cat. no. 330002)

10X Genomics Chip Holder (cat. no. 330019)

10X Genomics Magnetic Separator (cat. no. 230003)

Qubit Fluorometer (e.g., Thermo Fisher Scientific Qubit 2.0; cat. no. Q32866)

Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific; cat. no. Q32854)

Vortex Mixer (VWR, Vortex-Genie 2; cat. no. 10153–838). This model accepts the 10X Genomics Vortex Adapter and its vortex action does not cause foaming in the 10X Bead solution.

96-well metal block for efficient temperature transfer (optional)

50% Glycerol (Ricca Chemical Company, Glycerin (glycerol), 50% (v/v) Aqueous Solution; cat. no. 3290–32)

Lo TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.1 mM EDTA) (Thermo Fisher Scientific; cat. no. 12090–015)

10% Tween 20 (Bio-Rad; cat. no. 1610781)

100% ethanol

Nuclease-free water

DNA LoBind Tubes, 1.5 ml (Eppendorf; cat. no. 022431021)

PCR 8-tube strips (USA Scientific TempAssure; cat. no. 1402–4700)

DynaBeads® MyOne™ Silane Beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific; cat. no. 37002D)

SPRIselect Reagent Kit (Beckman Coulter; cat. no. B23318)

multichannel pipettor and tips

Set up the 10X Genomics Chromium Single Cell Processor

-

1

Thaw the 10X Chromium kit reagents.

Minimize the amount of time the dissociated cells have to sit prior to loading on the 10X Chromium, so have as much ready to go as possible.

Follow the instructions for thawing the reagents as given in the 10X protocol manual. For example, we used the Manual for the version 2 chemistry: Chromium Single Cell 3’ Reagent Kits v2 User Guide (manual number CG00052 Rev B). Reagents should be thawed for at least 30 minutes.

You can make up single cell master mix ahead of time but do not yet add the reverse transcriptase since there is only enough for the stated number of samples. This is to protect yourself in case something goes wrong with your cell preparation at the last minute.

-

2

Turn on the 10X Chromium Single Cell Processor.

-

3

Unpack the chip and place into the metal chip holder.

Keep the chip protected from dust (i.e., cover with a pipette tip lid or petri dish).

Count the cells

-

4

Count the cell suspension from Basic Protocol 1 using an automated cell counter.

We used a Cellometer, but you can use a hemocytometer. If cells are FACS sorted, often the FACS machine will provide cells counts.

During cell preparation, estimate the number of cells you expect to have and adjust the concentration of the final resuspension buffer so that you’ll have about 1,000 cells per microliter. This allows a suitable amount of cell suspension to be used for loading the 10X Chromium. Estimating cell number will save valuable time by not having to re-pellet and resuspend.

It is critical to count accurately; the number of cells loaded onto the 10X Chromium is important. You want to balance the number of cells measured with proportion of cells that occur as doublets. There are methods that attempt to identify and remove doublets (McGinnis et al., 2019; Wolock et al., 2019). You should decide how sensitive your goals are to the occurrence of doublets and how well you feel the available methods deal with doublets appropriately.

Many investigators, including us, consider that obtaining 3,000–4,000 cells per sample is a reasonable goal. There are new (combinatorial indexing) methods becoming available; they allow for barcoding multiple samples within a sample, thus loading more cells per sample.

-

5

Measure the proportion of viable cells using trypan blue.

Mix 10 μl cells with 10 μl of trypan blue and visually examine the cell suspension to determine whether cells take up or exclude dye. A viable cell will have a clear cytoplasm whereas a nonviable cell will appear blue.

This test can also be done by many automated cell counters. An alternative is staining with propidium iodide. Other methods are also available.

When combined with a live/dead fluorescent dye, FACS sorting can exclude dead cells. Non-viable cells may be read as a cell but produce an incorrect transcriptome profile. For instance, highly stressed or dying cells may show particular gene expression profiles, such as an enrichment in heat shock transcripts, or low library sizes. In many cases, non-viable cells are fragile enough that they lyse before they get incorporated into a droplet or they show an unusually high proportion of mitochondrial genes.

Load the cells and other reagents on the 10X Chromium and run the machine

-

6

Add the desired number of cells to the loading solution.

We used 9,000–10,000 cells per sample, because our normal recovery rate for this type of sample is about 40–50%. We loaded an excess number of cells to recover the target of 3,000–4,000 cells mentioned above.

-

7

Add the cell solution, the bead solution and the partitioning oil to the chip.

Please follow the instructions given in the 10X protocol closely.

Add 50% glycerol to all the wells that not being used for your samples.

It is convenient to add cells and reagents using a multichannel pipette.

-

8

Immediately load the chip into the 10X Chromium and start the instrument.

-

9

When the run ends transfer the emulsion from the chip to 0.2 ml strip tubes chilled on ice.

Pipette the emulsion out of the chip very slowly so the emulsion is not sheared open while being drawn into the pipette tip.

At this point the cells have been lysed, but the reverse transcriptase (RT) reaction has not taken place, so there is a potential for cross-contamination if the droplets are compromised.

Carefully examine the quality and quantity of the emulsion to be sure everything has gone well. You should get 100 μl of emulsion out of all wells. The entire volume should have a uniform “milky” appearance. If you see larger droplets, or significant clear solution, something has gone wrong. See the 10X Chromium protocol manual for what the emulsion should look like and to troubleshoot problems. In general, if something has gone wrong, it’s difficult to recover usable data from that sample.

Put the emulsion directly into a deep-well thermocycler and proceed with reverse transcription reaction as soon as possible (<60 minutes) using the parameters given in the 10X Chromium protocol. The reagents for this reaction are already in the droplets of the emulsion. The single stranded cDNA will be more stable than the RNA.

Convert the single stranded cDNA into a double stranded cDNA library

-

10

Add the organic Recovery Reagent provided in the 10X kit to break the emulsion and release the single stranded cDNA from all the droplets.

Pull out the cDNAs using DynaBead MyOne Silane magnetic beads and the magnetic stand provided by 10X kit. Wash twice with 80% ethanol and elute into Elution Solution as described.

All the reagents needed for these steps are provided in the 10X Chromium kit or given above.

At this point, each of the single stranded cDNAs from each of the transcripts has been labeled with a cell barcode and a UMI. There are sequences at each end that will be used for amplification in the next step.

-

11

Amplify the single strand cDNAs using the 10X primers and reagents and following the 10X instructions to produce a full-length double stranded DNA library.

The amplification employs primers complementary to sequences that have already been added to the ends of the single stranded cDNA. The number of PCR cycles depends on the number of cells you targeted for recovery. Since we targeted 3,000– 4,000 cells, we used 12 cycles.

Purify using SPRIselect magnetic beads, wash with 89% ethanol and elute into Elution Buffer.

This removes all the small fragments and oligonucleotides.

-

12

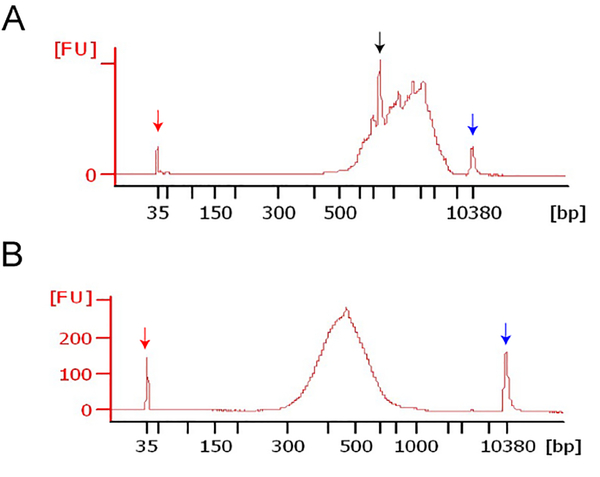

Run the cDNA on a Bioanalyzer to check the quality and quantity.

Use a high sensitivity DNA chip. The cDNA should have a high molecular weight with a wide distribution of sizes (Figure 3A). In our larval fly VNC samples we also observed an abundant specific transcript at about 700 bp.

Figure 3.

High sensitivity DNA analysis

Bioanalyzer assay of full-length double stranded cDNAs (A) and sequencing libraries (B). Peaks at 35bp (red arrow) and 10380 bp (blue arrow) represent low- and high-molecular weight markers. The cDNAs isolated from the Drosophila third instar larvae VNCs have relatively high molecular weight, with a peak at ~700bp (black arrow). Upon PCR amplification, the libraries appear as a smooth peak.

Convert the full-length, double stranded cDNA into a sequencing library

-

13Continue to use reagents provided by 10X kit and closely follow the protocols from the user guide that accompanies the Chromium Single Cell 3’ Reagent Kits (or the particular reagents that you are using). These steps can be briefly summarized as follows:

- Fragment the full-length cDNA. Only the distal end of the 3’UTR (adjacent to the polyA tail) will have the 10X cell barcode, UMI and primer adaptor appended.

- Perform end-repair and A-tailing to prepare fragments to accept an adapter with an over-hanging T.

- Clean up the fragments using SPRIselect magnetic beads to select fragments of a proper size range. Note this is a double-sided size selection, so the bead protocol has extra steps. The supernatant is kept after the first round and the beads are retained after the second round. Elute into Elution Buffer.

- Ligate the adaptor to the fragments. Only fragments from the distal end of the 3’UTR will have the 10X cell barcode, UMI and primer adaptor appended at one end and the second adapter at the other end.

- Amplify the fragment pool using primers provided by 10X targeting the adapters at both ends of the distal 3’UTR fragments. Only these fragments will amplify and be present in the final sequencing library. If appropriate, this is the step where the sample index is added by using a primer from 10X that has an appropriate set of indexes. The number of PCR cycles is dependent on the amount of full-length double stranded cDNA you obtained at the end of step 12 above.

- Clean up the library using SPRIselect magnetic beads to remove unincorporated primers. This is now your sequencing library.

-

14

Run the library on a Bioanalyzer to check the quality.

Use a high sensitivity DNA chip. The library should run as a smooth peak at about 450–500 bp (Figure 3B).

Run the samples on an Illumina DNA sequencer

-

15

Combine indexed samples as desired.

In most cases you will combine equal amounts of each library (based on Qubit or PCR quantification). However, if you expect different numbers of cells in each sample, then you may want to adjust amounts accordingly.

For the examples presented here and in the accompanying protocol, we combined two sample libraries in a single sequencing run.

-

16

Load the samples onto an Illumina sequencer.

Choose an appropriate sequencer and flow cell to achieve the targeted number of reads per cell. For the Chromium Single Cell 3’ Reagent Kit v2 used here, 10X Genomics recommends 50,000 reads per cell. Therefore, if you expect to get 3,000 cells per sample, and you have two samples, the total number of reads you would like to have is 50,000 (reads per cell) x 2 (samples) x 3,000 (cells per sample) = 300 million.

-

17

Sequence using Read 1 = 26 bp; Read 2 = 98 bp, and i7 index read = 8 bp.

This will generate raw files called base call files (BCLs) that are used by the Cell Ranger software for analysis. Read 1 contains the cell barcode and the UMI. Read 2 contains the sequence from the distal 3’UTR of the transcript. The i7 index read contains the sample index.

BASIC PROTOCOL 3.

Align raw sequencing data to indexed Drosophila genome and generate count matrices

This protocol describes the processing of raw scRNA-seq data generated by Illumina sequencers and the alignment of sequences with the reference genome of your choice. To speed up the computation required for these alignments, most available software start by creating a set of index files of the reference genome; this index genome is practically a reorganized version of the original genome that retains all the sequence information but reorders it to facilitate searching.

Initial handling of scRNA-seq datasets generated with the 10X platform begins with processing of data using the Cell Ranger software package, developed and provided by 10X Genomics (https://github.com/10XGenomics/cellranger). Cell Ranger is freely available and runs on a Unix platform (https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/pipelines/latest/installation). Cell Ranger combines Chromium-specific algorithms with the widely used RNA-seq aligner STAR (Dobin et al., 2013) to align reads, generate feature-barcoded matrices, and also perform cell clustering and gene expression analysis. In this protocol we will use Cell Ranger only for converting raw scRNA-seq data generated from sequencers into raw count matrices with gene annotation. The count matrix contains one column per cell barcode detected in the sequencing files and one row for each gene listed in the annotated transcriptome GFT file (see below). Each position in the matrix contains the number of counts determined for each gene in each cell. Further data analyses will be addressed in the accompanying manuscript, which describes a custom multistage algorithms pipeline.

To run the initial data processing pipeline, you will need high performance computing and a system with at least 16Gb of RAM and 16 cpu threads for handling the Drosophila genome. More memory will be required for larger genomes. The processing time generally scales with more available cpu threads. We have used the computational resources of the NIH HPC Biowulf cluster (http://hpc.nih.gov). A terminal window is available natively in Mac OSX installations under “utilities”, and a terminal window can be used in Windows with PuTTY (https://www.chiark.greenend.org.uk/~sgtatham/putty/latest.html) to connect to a Unix server.

More details on the algorithms included in the Cell Ranger software and the running of these pipelines are available the 10X Genomics website (https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/pipelines/latest/what-is-cell-ranger). Basic knowledge of Bash command language (http://www.gnu.org/directory/GNU/) is also required. The Cell Ranger pipelines have been optimized to convert the base call files (BCLs) (binary files with raw scRNA-seq output generated by Illumina sequencers) into FASTQ text-based sequence files. Depending on your sequencing facilities and instrumentation, you may also receive sequencing data directly as FASTQ files. In both cases, these FASTQ files are next analyzed internally by Cell Ranger suite algorithms that implement rigorous quality control checks. Importantly, the Cell Ranger package handles automatically the UMI and cell barcode information from a 10X experiment producing analysis-ready quantitation of expression at the single cell level.

The initial data processing includes three basic steps:

Generate a reference genome with optional addition of transgenes

Demultiplex 10X run data from Illumina sequencers

Align data to the reference genome and generate read count matrices

In this protocol we will describe the tools and the Cell Ranger pipelines required for these three steps.

Generate a reference genome with optional addition of transgenes

Generic mouse and human reference genomes are already provided by 10X Genomics. To build a custom reference genome (i.e. Drosophila reference transcriptome), you will need two pieces of information: (1) a genome sequence in FASTA format for read alignment, and (2) a gene transfer format (GTF) file of gene definitions for identifying the position and organization of the annotated genes. A genome sequence can be obtained from any of the genome databases. In our protocol, we have utilized the Drosophila melanogaster genome assembly BDGP6.28 along with gene annotation (GTF) from Ensembl release 48 (https://uswest.ensembl.org/Drosophila_melanogaster/Info/Index).

-

1Download and save the transcriptome gene transfer format (GTF) file from the Ensembl database. This will be downloaded as a zipped file (with extension .gz).

# download GTF file ~ users$ wget “ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/metazoa/release48/gtf/drosophila_melanogaster/Drosophila_melanogaster.BDGP6.28.48.gtf.gz”

-

2Download and save the genomic FASTA file from the Ensembl database. This will also be downloaded as a zipped file (with extension .gz).

# download FASTA file ~ users$ wget “ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/metazoa/release48/fasta/drosophila_melanogaster/dna/Drosophila_melanogaster.BDGP6.28.dna.toplevel.fa.gz”

Please use the most current genome assembly versions and make sure you are using (GTF) annotations that match your genome.

-

3Unzip the reference GTF and FASTA files downloaded in steps 1 and 2.

# unzip the reference GTF and FASTA ~ users$ gunzip Drosophila_melanogaster.BDGP6.28.dna.toplevel.fa.gz ~ users$ gunzip Drosophila_melanogaster.BDGP6.28.48.gtf.gz -

4

If your sample contains transgenes/reporters whose expression need to be tracked, the sequences of those reporters need to be added as additional “contigs” or “chromosomes” to the genomic FASTA. In addition, for quantitation purposes, a GTF entry must be added for each transgene to define those regions as belonging to the transgene. Please see https://uswest.ensembl.org/info/website/upload/gff.html for details on the GTF entry format. In this protocol, we have used GFP and RFP reporters. Note that most of the available GFP or RFP transgenes have been inserted upstream of a SV40 polyA cassette, therefore the 3’UTR sequence of most GFP and RFP transgenes will be common. Remember that in the 10X Genomics sequencing libraries only the distal 100–200 bases adjacent to the polyA tail are present; this is the only part of the reporter cassette that will be sequenced.

Generally, it is recommended to apply the “exon” designation to the blocks of sequence added. These can be appended (concatenated) to the existing reference sequences and gene definitions as in the example below. Here we have used just some 3’UTR sequence common to both RFP and GFP reporters. In the second line, “→” indicates a tab.# generate FASTA and GTF for exogenous transgene(s) ~ users$ cat transgenes.gtf RFP_GFP→CUSTOM→gene→1→526→.→+→. gene_id “RFP GFP”; transcript_id “RFP_GFP”; gene_name “RFP GFP”; gene_source “custom”; gene_biotype “protein coding” ~ users$ cat transgenes.fa >RFP_GFP TAATCCGCGGTAGATCATAATCAGCCATACCACATTTGTAGAGGTTTTACTTGCTTTAAAAAACCTCCCACACCT CCCCCTGAACCTGAAACATAAAATGAATGCAATTGTTGTTGTTAACTTGTTTATTGCAGCTTATAATGGTTACAA ATAAAGCAATAGCATCACAAATTTCACAAATAAAGCATTTTTTTCACTGCATTCTAGTTGTGGTTTGTCCAAACT CATCAATGTATCTTAAGGCGTAAATTGTAAGCGTTAATACTAGTTGGCCACGTAATAAGTGTGCGTTGAATTTAT TCGCAAAAACATTGCATATTTTCGGCAAAGTAAAATTTTGTTGCATACCTTATCAAAAAATAAGTGCTGCATACT TTTTAGAGAAACCAAATAATTTTTTATTGCATACCCGTTTTTAATAAAATACATTGCATACCCTCTTTTAATAAA AAATATTGCATACTTTGACGAAACAAATTTTCGTTGCATACCCAATAAAAGATTATTATATTGCATACCCGTTTT T

-

5Combine transgene GTF and FASTA to the reference GTF and FASTA, respectively.

# combine transgene GTF and FASTA to the reference ~ users$ cat Drosophila_melanogaster.BDGP6.28.dna.toplevel.fa transgenes.fa >combined.fa ~ users$ cat Drosophila_melanogaster.BDGP6.28.48.gtf transgenes.gtf > combined.gtf -

6

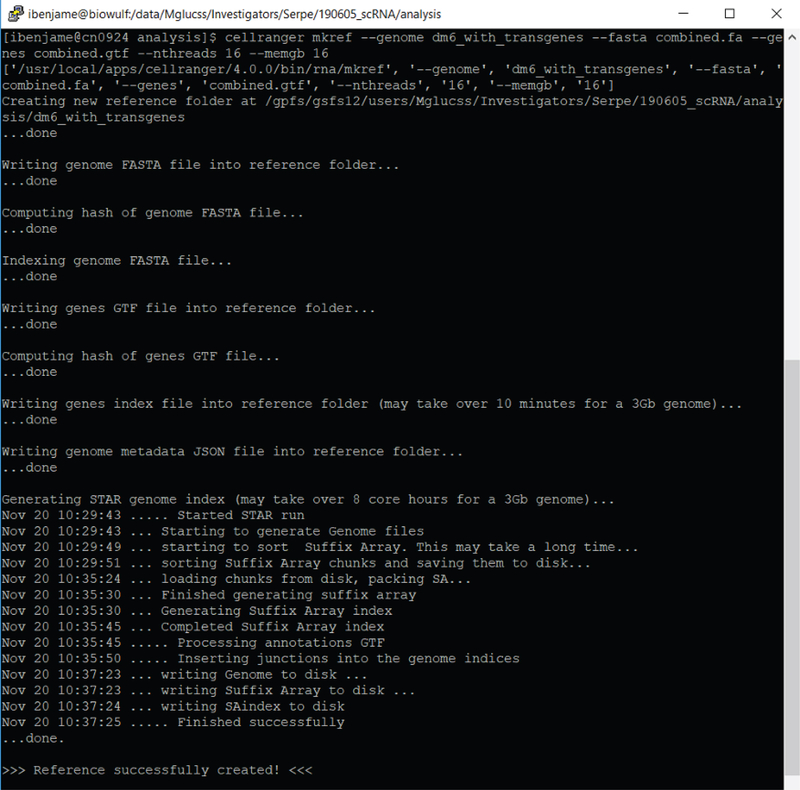

Use cellranger mkref to match combined transgene GTF and combined FASTA and generate a genome index.

For this protocol, we generated an output folder named “dm6_with_transgenes”.

# generate genome index

~ users$ cellranger mkref --genome dm6_with_transgenes --fasta combined.fa

--genes combined.gtf --nthreads 16 --memgb 16

Figure 4 illustrates an example of preparing a genome index with additional transgene using cellranger mkref.

Figure 4.

Preparing the index genome “dm6_with_transgenes” with cellranger mkref

The time needed for index generation will vary depending on genome size and the system resources utilized. Larger mammalian genomes may require more indexing memory. Please refer to 10X documentation for additional details (https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/pipelines/latest/advanced/references).

Demultiplex 10X raw data from Illumina sequencer

Molecular indexing or multiplexing allows for pooling of multiple samples and thus optimizing sequencing cost and data output. Demultiplexing is the process by which the sequencing reads are assigned to their sample index sequence. Note the sample index is not the same as the barcode. This step separates the samples; a subsequent step assigns reads to individual cells.

Ideally, the cellranger mkfastq function should be used to demultiplex a raw Illumina dataset (run folder consisting of unmodified BCL files from the instrument run). You will also need a sample sheet in simple CSV format which tells the mkfastq pipeline which sample libraries are sequenced on which sequencer flow cell lanes and what are the associated sample index sets/ barcodes. This CSV file has three fields: (1) “Lane” – (lane number on the sequencer flow cell to thread, or ‘*’ for all); (2) “Sample” (the sample name to be used in files), and (3) “Index” (the sample index set attached to the sample during library construction). Note that 10X indexes typically consist of 4 balanced indexes per sample and are combined automatically by the mkfastq process.

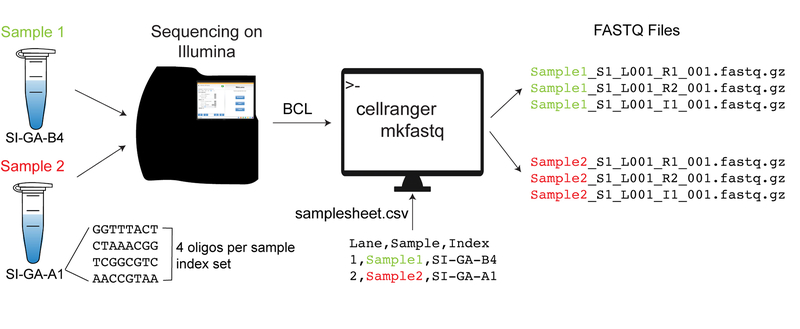

A diagram of the demultiplexing process is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Diagram of the demultiplexing process with cellranger mkfastq for two samples/libraries sequenced together

The base call files (BCLs) (binary files with raw scRNA-seq output generated by Illumina sequencers) and the sample sheet CSV files constitute the input for the cellranger mkfastq function. The output consists of three FASTQ files per sample; these are immediately subjected to quality control checks internally, by Cell Ranger suite algorithms. The FASTQ files are next used to identify and sort out the cells/barcodes, the unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and the sample ID.

-

7

Create a CVS sample sheet for cellranger mkfastq.

In this example, “RP2_GFP” and “isoW” are the names of two of our samples. Each subsequent line would list another sample.

# create csv sheet for various samples

~ users$ cat samplesheet_example.csv

Lane, Sample, Index

*,RP2_GFP, SI-GA-B4

*,isoW, SI-GA-A1

-

8

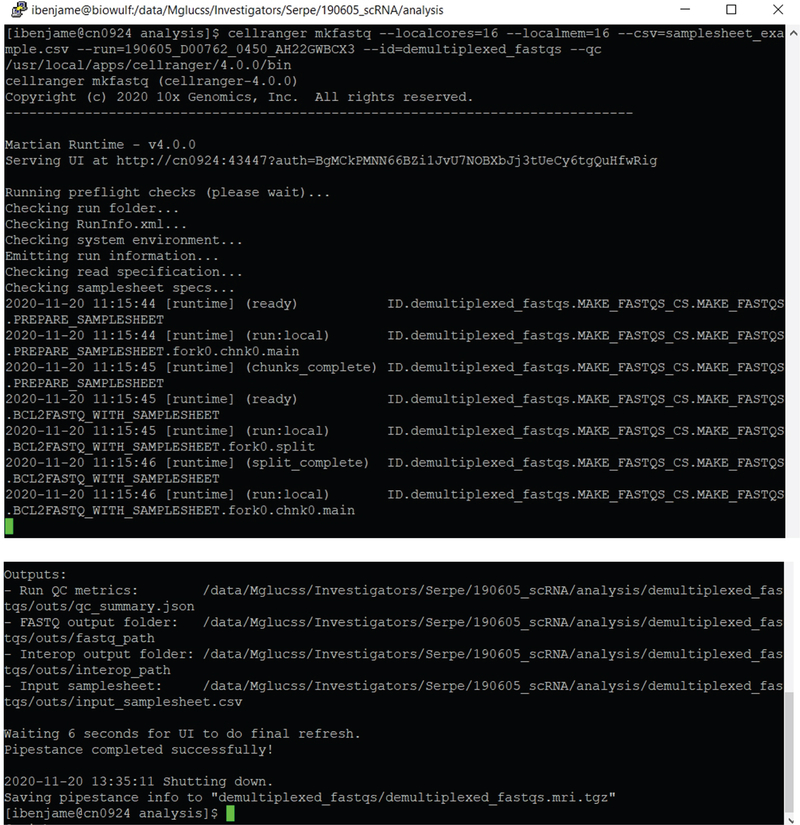

Use the cellranger mkfastq function to demultiplex the samples.

This command uses the CSV file made in step 8 above.

# run the cellranger mkfastq function

~ users$ cellranger mkfastq --localcores=16 --localmem=16 --

csv=samplesheet_example.csv --run=190605_D00762_0450_AH22GWBCX3 --

id=demultiplexed_fastqs --qc/usr/local/apps/cellranger/4.0.0/bin

In this example “190605_D00762_0450_AH22GWBCX3” is the name of the run folder automatically generated by the Illumina sequencer that held our two samples. It contains all the raw BCL files from a single run. It also has other files, some of which are used by Cell Ranger to process the data.

If samples have been repeatedly sequenced over multiple flow cells, the cellranger mkfastq pipeline should be repeated for each run providing a separate “id” destination folder for each.

Example of syntax for running cellranger mkfastq and the outputs are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Example of syntax for running cellranger mkfastq

When demultiplexing using the cellranger mkfastq pipeline, the output will consist of three FASTQ files per lane, as follows:

a sample index file

a first, short read (containing the cell barcode with UMI)

a second, longer read (containing the 3’ polyA-linked read for the gene - used for mapping and quantitation).

These FASTQ files can be used to identify and sort out the cells/barcodes, the unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and the sample ID. This is the heart of the scRNA-seq and cellranger mkfastq pipeline performs all these tasks internally. A more detailed documentation on the cellranger mkfastq process is available from the 10X website (https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-geneexpression/software/pipelines/latest/using/mkfastq).

These output files also have a number of quality control metrics that can be used to decide whether to proceed to the subsequent, resource intensive cellranger count pipeline. Some examples include the percentage of indexes and barcodes matching those expected, and the overall quality of each of the categories of reads.

Align data to the reference genome and generate read count matrices

Once demultiplexing is complete, the sequencing data is now ready for alignment to the previously created index genome and quantitation. To accomplish this, run the cellranger count pipeline using the FASTQ files output from above. The cellranger count utilizes the RNA-seq aligner STAR (Dobin et al., 2013) to align the data to the previously prepared genome index. This pipeline also quantitates gene expression based on their overlap with the GTF-defined features (usually “exons”). Please note that the “count” process comprises both the alignment and quantitation steps combined. Nonetheless, a separate cellranger count process should be utilized for each individual sample from an experimental set.

-

9

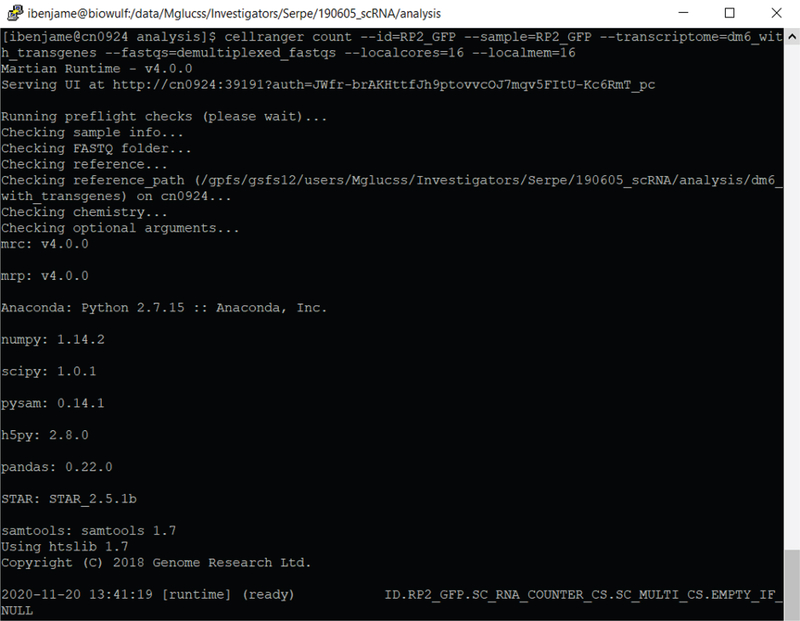

Run the cellranger count pipeline

In this example we use the sample “RP2_GFP”.

# run cellranger count for sample “RP2_GFP” with genome index

“dm6_with_transgenes” into folder “RP2_GFP”

~ users$ cellranger count --id=RP2_GFP --sample=RP2_GFP --

transcriptome=dm6_with_transgenes --fastqs=demultiplexed_fastqs --

localcores=16 --localmem=16

The cellranger count function first aligns the single 3’ polyA-adjacent read to the index reference genome using the STAR aligner producing an indexed BAM file. The BAM file contains the chromosome number and the coordinates for each read. Additional read metadata derived from the other FASTQ files (including the cell barcode, the UMI, and any overlapping exon gene definition) is attached to the BAM entry for the read at this step.

In an additional pass over the aligned and tagged read data, quality control and logical filtering is applied to generate final quantitative gene expression at the single cell level:

Reads that were confidently mapped to the transcriptome are placed into groups sharing the same cell barcode, UMI and gene annotation.

If two groups of reads have the same barcode and gene, but their UMIs differ by a single base-pair (Hamming distance 1 apart), this UMI will be grouped together, and considered derived from the same transcript and the same cell.

If two or more groups of reads have the same cell barcode and UMI, but different gene annotations, cellranger count retains the gene annotation with the most supporting reads for UMI counting.

A screenshot during the run of cellranger count is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Example of cellranger count for sample “RP2_GFP” with built index “dm6_with_transgenes” deposited into folder “RP2_GFP”

-

10

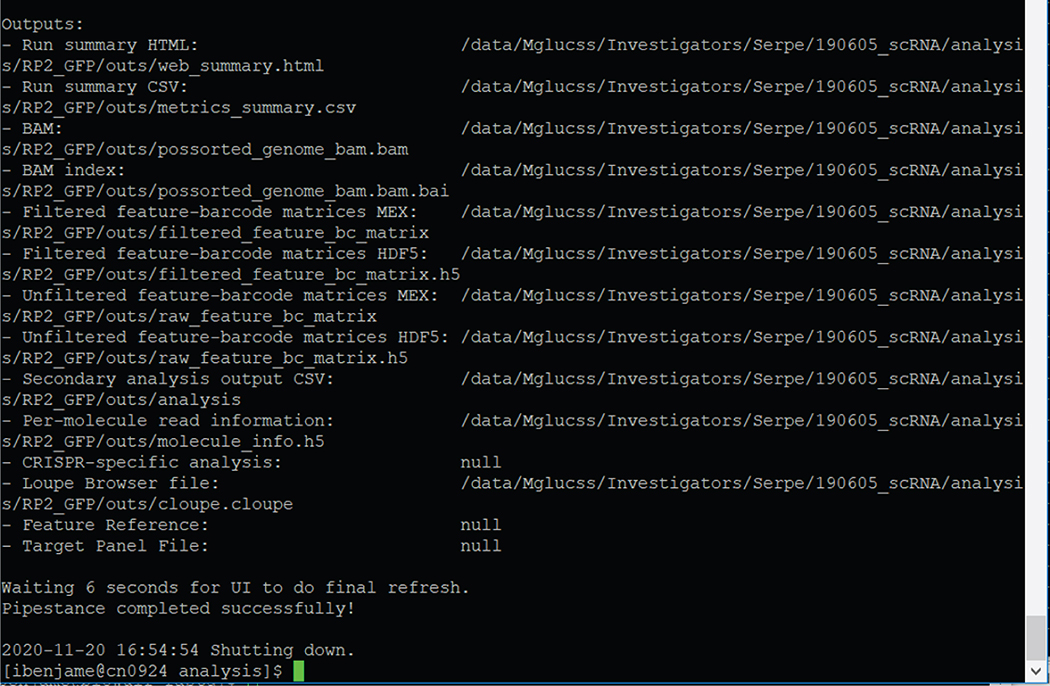

Generate read count matrices

Once reads are aligned and flagged, UMI-treated count data in reduced matrix format are prepared in the output folder under “outs/filtered_feature_bc_matrix” for cells identified by cellranger, or under “outs/raw_feature_bc_matrix” for all unfiltered cell barcodes regardless of read content. Each UMI count folder contains 3 different files (barcodes.tsv, genes.tsv and matrix.mtx) which records each observed cell barcode, gene annotation and UMI count, respectively. The folder outs will also contain the sorted and indexed alignment BAM as well as a cloupe file for use in the 10X Loupe Browser. See 10X documentation for more details on the cellranger count process (https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/pipelines/latest/using/count).

Figure 8 shows a screenshot of the list of the files contained in the folder outputs of cellranger count.

Figure 8.

Example of cellranger count outputs for sample “RP2_GFP” with built index “dm6_with_transgenes” deposited into folder “RP2_GFP”

Please note that the “raw_feature_bc_matrix” includes all of the cell barcodes regardless of the number of UMIs; this includes background “cells” arising from non-cellular RNA that is incorporated into droplets during emulsion formation on the 10X Chromium (see above). This free RNA is derived from cell lysis during processing. We use this unfiltered count matrix (raw_feature_bc_matrix) for downstream data analysis, as described in the accompanying manuscript.

Optionally, samples may be combined using the cellranger aggr function to aggregate multiple samples together. When samples have uneven depth, i.e. one sample has a higher number of genes or transcripts detected per cell, the Cell Ranger normalizes the samples during aggregation. This is done by down-sampling, or randomly reducing, the reads assigned to each cell such that all samples have a median UMI count per cell equal to the lowest sample. Such adjustment facilitates samples comparisons without depth-based artifacts caused by uneven sequencing or counting. This step is unnecessary for most non-10X-based analysis pipelines but may be helpful when visualizing the data for multiple samples with the 10X Loupe Browser. In the accompanying manuscript we also describe an alternative way to address the differences in sequencing depth using a custom multistage analysis pipeline.

Reagents and solutions:

Cell dissociation solutions

Collagenase/Dispase (Millipore-Sigma; cat. no. 10269638001)

Liberase (Millipore-Sigma; cat. no. 05401054001)

Collagenase/Dispase

Reconstitute 100 mg of lyophilized Collagenase/Dispase in 1 ml of RNase/DNase free water to obtain a stock concentration of 100 mg/ml (100X). Make 10 μl aliquots and store at −20°C. Add 10 μl of this stock to 990 μl of DPBS to obtain 1X working solution.

Liberase

Reconstitute 5 mg of lyophilized Liberase in 2 ml of RNase/DNase free water to obtain a stock concentration of 13 Wunsch units/ml. Make 10 μl aliquots and store at −20°C. Add 8 μl of the stock to 1032 μl of DPBS to obtain 1X working solution of 0.10 Wunsch units/ml.

Combine 800 μl of 1X Collagenase/Dispase and 200 μl of 1X Liberase to make 1 ml of cell dissociation solution.

Schneider’s medium

Schneider’s Insect Medium (Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific; cat. no. 21720024) Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific; cat. no. 15140122);

Heat Inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum, FBS (Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific; cat. no. 16140063)

To make 50 ml of Schneider’s medium, add 5 ml of FBS and 0.5 ml of penicillin-streptomycin to 44.5 ml of Schneider’s Insect medium.

Toxin solutions

Tetrodotoxin (TTX) (Biotium; cat. no. 00060)

D(−)-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (AP-5) (Abcam; cat. no. ab120271)

6-Cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) (Tocris Bioscience; cat. no. 1045)

These toxins are extremely potent poisons.

They should be stored at −20°C in a locked box and their usage monitored. Since many institutions regulate the distribution and storage of these compounds, please contact your chemical safety office to learn about and comply with the appropriate requirements.

Prepare stock solutions for each of the three toxins as indicated below:

50.0 mM AP-5 stock solution in water

20.0 mM CNQX stock solution in water

1.0 mM TTX stock solution in citrate buffer (pH 4.8).

Aliquot and store them at −20°C (in a locked boxed) until the day of the experiment.

Schneider’s medium supplemented with toxins

To 30 ml of previously prepared Schneider’s medium (with 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin) add 3 μl of 1.0 mM TTX, 30 μl of 50.0 mM AP-5 and 30 μl of 20.0 mM CNQX stock solutions. Keep this solution on ice.

Sylgard plates

Sylgard 184 Silicone Elastomer Kit (World Precision Instruments: cat. no. SYLG184)

Insect pins

Thoroughly mix Sylgard 184 in a weight ratio of 10 parts base to 1 part curing agent. Stir gently to reduce the amount of air introduced. Allow mixture to set for 30 minutes then pour a ~6 mm layer into (35 mm or 90 mm) Petri dishes. The Sylgard elastomer should be cured at 25°C; it will become solid in 24 hours and will be ready to use in 7 days.

This bed of Sylgard elastomer provides a very convenient surface for pinning and dissecting various Drosophila tissues. Larvae dissection usually requires 6 pins for each specimen. The pins (cut to the desired length from tungsten wire or from commercially available insect pins) should be inserted in the Sylgard elastomer in clusters of 6 or more. Several 90 mm Petri dishes with 8 or more pin clusters (of 6 pins/cluster) will accommodate the fast-paced dissections required in this protocol.

Commentary

Background information

In just a few years, the single cell analysis of the Drosophila brain has transitioned from picking up targeted neuroblasts using a custom device for robotic single-cell picking (Yang et al., 2016) to sophisticated FACS- and microfluidics-based high-throughput methods that can be used to sample the entire fly brain (Davie et al., 2018).

Whether or not FACS-based separation of cells is used, single cell transcriptome analysis is instrumental in illuminating the types, functions and responses of cells in neural tissue. There are numerous single cell technologies available and the scope and variety is rapidly evolving. A number of recent reviews offer additional details and side-by-side comparisons (Papalexi and Satija, 2018; Valihrach et al., 2018), but a few comments are included here to provide a context for where these protocols fit into the larger picture and why we chose this method for our purposes. This is not intended to endorse a specific product, but to explain our particular decision.

Based on how the cells are physically isolated, single cell transcriptomic technologies can be divided into three categories. The first category includes plate-based technologies, that sort individual cells into distinct physical compartments. These are usually relatively low throughput but provide more control over the selection of the cells to be interrogated. Some of these techniques enable sequencing of the entire transcriptome. Examples include Smart-Seq2 (Picelli et al., 2013), Seq-well (Aicher et al., 2019), iCell8 (Takara, Inc.), or Fluidigm C1 (Fluidigm, Inc). Since they are relatively labor intensive, these methods usually only interrogate hundreds of cells at a time, albeit Seq-well can do more.

To overcome this limitation, a second category of methods was developed that uses microfluidics to encapsulate single cells in emulsion droplets with reagents that allow barcoding of transcripts from the same cell and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to enable more accurate counting of transcripts. These high throughput methods include Drop-Seq (Macosko et al., 2015), inDrop (Klein et al., 2015), and 10x Genomics Chromium (Zheng et al., 2017). These droplet-based methods can generate transcriptomic libraries for thousands to tens of thousands of single cells.

As the advantages of single cell transcriptomics became more apparent, and bioinformatics analyses became more powerful, a third category of methods were developed that utilize combinatorial indexing to further increase the throughput. Examples of such methods include sci-RNA-Seq (Cao et al., 2020) and SPLiT-Seq (Rosenberg et al., 2018). These laborious methods result in interrogation of tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of single cell transcriptomes. Because of the scale of these experiments, more sequencing is required, often with fewer reads per cell.

Within this landscape of possibilities, we chose to use the 10X Genomics Chromium Single Cell Processor platform (10X Chromium) because it addressed our needs, was the simplest to use and had a good track record of performance. We wished to identify subsets of larval neurons and to determine and compare gene expression levels under various conditions and in different mutants. This can be accomplished using expression of the distal end of the 3’ UTR, near the polyA tail; however, this does not provide any information regarding alternative splicing. The advantage of obtaining a single sequencing read per transcript is that it requires many fewer sequencing reads than interrogating the entire transcript. This usually results in better count data in comparative gene expression analyses. A disadvantage is that it is common to have substantial variability in per-gene transcript counts across individual cells, including dropout of genes that are actually expressed. If information on expression of splice variants is desired then a different, more appropriate method (i.e., Smart-Seq) should be chosen.

As evident from the protocols described here, 10X Chromium is also a fairly simple method to use. In contrast, initial trials with the Fluidigm C1 system resulted in too few cells for our efforts. Then, experience with Drop-Seq, which generated data from enough cells, showed the disadvantage of processing samples one at a time, rather than in parallel. Using the 10X Chromium platform we were able to run multiple samples in parallel to minimize batch effects. Since we wanted count data rather than splicing information, and since a scale of thousands of cells is sufficient for the larval VNCs, 10X Chromium emerged as a good option for our studies. Because 10x Chromium is widely used, we also found many software tools available for data analysis. In our hands, this method generated a rich dataset and abundant bioinformatic insights.

The richness of the scRNA-seq data has already been harnessed to derive general principles that govern how transcription factors regulate cell-type diversity in the optic lobe (Konstantinides et al., 2018) or how homeobox genes and other neuronal lineage markers maintain the segmentally repeating nature of the adult ventral cord neurons (Allen et al., 2020). The entire fly brain has been profiled across the fly lifespan and a comprehensive single-cell transcriptome atlas of the adult brain has been built. This atlas maps gene regulatory networks underlying neuronal and glial cell types but also describes brain-wide cell-state changes that occur during aging (Davie et al., 2018). More details on scRNA-seq studies in Drosophila CNS as well as other tissues are discussed in a recent review (Li, 2020).

Troubleshooting

As for any scRNA-seq experiment, the biggest challenge in profiling the larval VNC will be to separate and unequivocally identify different cell types. This will be discussed more in the accompanying manuscript.

Flies have a small but remarkably complex nervous system. In preparation for the scRNA-seq experiments you should mine the literature for previously described cell markers/specific transcripts that may help in assigning cell identity. In parallel, you should invest in identifying and refining labeling strategies for the cells of interest starting with screening through the large collections of driver/Gal4 lines that include regulatory elements of neurally-expressed genes (Pfeiffer et al., 2008). Keep in mind that highly-specific marking of neurons usually requires combinatorial, split methods, that restrict the expression of regulatory targets to cells where the two or more components of a split system are co-expressed (Luan et al., 2006). The multiple transgenes required may complicate the genetic background and induce transcriptional changes and sometimes cellular stress. Use multiple labeling to identify and define the cells of interest only for the initial step of your analysis. Should you need to compare transcriptional profiles of a particular cell type in various mutants, first exploit the multiple labeling strategy to identify the cluster of interest; next, identify new markers for that cell type. Then run scRNA-seq on various mutants leaving out the multiple transgenes and using the new markers to follow the cells of interest. These precautions will minimize cell stress and the appearance of unexpected cell clusters during subsequent analysis. Moreover, if the mutants of interest distort the Gal4 expression pattern, cell types may be incorrectly assigned.

Flies have very small cells. It is challenging to dissociate the fly CNS into high-quality single cell suspensions and to efficiently capture single cells for library preparation. To ensure a high-quality suspension, one first needs to minimize the cell stress during the tissue dissection and cell dissociation steps. If the larvae are stretched excessively during the dissection, prior to immersion into the Schneider’s medium supplemented with toxins, the neurons will be activated and will fire, altering the state of the VNC cells.

Technical and biological noise may dramatically influence the biological outcome of the scRNA-seq results (Brennecke et al., 2013; Marinov et al., 2014). For example, enzymatic treatment of a tissue may have profound effects on cell viability and/or transcriptional profile (Kolodziejczyk et al., 2015). Prolonged dissociation may induce alterations in gene expression in subpopulations of cells (van den Brink et al., 2017). Tissue dissociation in cold condition will generally minimize stress responses (O’Flanagan et al., 2019). To make sure that you can prepare high quality single-cell suspensions, practice steps 13–17 from Basic protocol 1 for a few times keeping the cells on ice for most of the time and examining the cells often by counting them and checking their viability (using the trypan blue exclusion test). The dissociating enzymes used here were optimized for larval brain (Takemura et al., 2011; Yin et al., 2018). However, further optimization of the enzymatic reaction time and the trituration conditions may be needed until you achieve a well dispersed cell solution but before you start observing cell debris and dead cells. Vigorous trituration will create mechanical stress and cell shearing. Patience and care at this stage cannot be overstated.

The scRNA-seq experiments are expensive and the data analysis is complex and time consuming. Fewer but high-quality cells will be a lot more informative and desirable than plenty of damaged cells. Dead or damaged cells will have poor RNA quality and will generate weak cDNA libraries that introduce noise in the transcriptome data. Cell debris such as pieces of membranes or other cell parts, will bind to and occupy barcoded beads but yield no cDNA, ultimately reducing the efficiency of cell capture. A low mRNA capture efficiency and suboptimal cDNA amplification will further increase technical noise (Brennecke et al., 2013; Marinov et al., 2014). In contrast, even when you load a less than optimal number of cells on the 10X Chromium chip, if these cells are healthy and generate good cDNA libraries, then your results will be informative.

FACS sorting requires more time and may introduce additional cell stress but it does confer several advantages. First, this method can substantially enrich a population of specific, marked cells and allow for their independent analysis. Second, when combined with a live/dead fluorescent dye, FACS sorting can remove the dead cells from a suspension and thus effectively remove a large source of technical artefacts. Furthermore, FACS can isolate single cells away from larger cell doublets and aggregates or smaller cell debris, both of which could decrease the efficiency of the single cell capture. One critical limitation of the FACS-based methods is the ability to specifically label the cells of interest and separate them away from other cell types. In flies, such labeling is usually genetic and based on the Gal4/upstream activating sequence system or its newer derivatives (Caygill and Brand, 2016).

Sometimes the cells of interest are very frail and cannot be enzymatically and/or mechanically dispersed without significant damage. To preserve the integrity of such cells and of their transcriptomes, recent efforts have sought to introduce fixation steps in the scRNA-seq pipelines. Addition of fixation steps may also increase the flexibility of sample handling and allow for storage before processing, alleviating some of the time constraints of profiling live cells. However, paraformaldehyde (PFA) is incompatible with the protocols described here, since PFA fixation-induced cross-linking prevents primer annealing in the reverse transcription reaction. Methanol fixation could provide a possible solution, albeit to our knowledge this type of fixation was only applied successfully on Drosophila embryos (Alles et al., 2017). In brief, embryos dissociated into single cell suspension, were filtered and resuspended in a small amount of dissociation buffer, then fixed by adding 4 volumes of ice-cold 100% methanol (for a final concentration of 80% methanol). Fixed cells were stored for up to 2 weeks at −20°C. For library preparation, cells were moved to 4°C, and rehydrated in PBS + 0.01% BSA in the presence of RNAse inhibitor (RiboLock 1U/μl). Cells were washed once in this same buffer before filtration and resuspension in PBS + 0.04% BSA, or in your preferred resuspension buffer for loading the 10X Chromium chip. It is important to point out that the quality of scRNA-seq data from fixed embryonic cells resembled that of fresh cells. We think that a methanol fixation step may help alleviate some of the low-quality single-cell problems posed by sensitive VNC cells. Alternatively, the development of single-nucleus (sn) RNA-seq methodologies may offer new solutions in the future, since nuclear transcripts appear to contain sufficient information to identify and define distinct neuronal cell types (Bakken et al., 2018).

Results

We performed scRNA-seq on third instar control VNCs isolated from wondering larvae using the 10X Chromium methods and the protocols described above. We run three replicates on separate days using 30 VNCs (larvae) per sample. Each experiment used a different Drosophila line as follows:

w1118 with RFP-labeled subsets of neurons

w1118 with GFP-labeled subsets of neurons

isogenized w1118

Approximately 10,000 cells of each genotype were loaded on 10X Chromium. Based on the number of barcodes, we sequenced ~9,000 cells for VNC1, ~6,000 cells for VNC2 and ~7,000 cells for VNC3. The three runs produced comparable results with a median sequencing depth of ~30,000 sequence reads per cell (Table 1).

Table 1:

Summary of scRNA-seq sequence results

| Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing | VNC1 | VNC2 | VNC3 | Average |

| Number of Reads | 233,891,627 | 269,163,359 | 234,297,127 | 245,784,038 |

| Valid Barcodes | 98.2% | 98.2 | 98.3% | 98.2% |

| Mapping | ||||

| Reads mapped to genome | 96.3% | 96.9% | 96.7% | 96.6% |

| Reads mapped confidently to genome | 95.0% | 95.5% | 95.5% | 95.3% |

| Reads mapped confidently to intronic regions | 2.5% | 2.7% | 1.8% | 2.3% |

| Reads mapped confidently to exonic regions | 92.0% | 92.3% | 93.3% | 92.5% |

| Reads mapped confidently to transcriptome | 88.7% | 89.0% | 90.3% | 89.3% |

The quality of the sequencing data summarized in Table 1 is very high, with high number of reads and >98% valid barcodes recovered. An average of 96.6% of the reads mapped to genome and, after using the cellranger count to correct the barcode, UMI and gene annotation, an average of 95.3% reads mapped confidently to genome. Most of these reads mapped to exonic regions and less than 3% mapped to intronic regions. This reflects the fact that with this methodology the library preparation is restricted to only a fragment from the distal 3’UTR of each transcript.

As will be detailed in the accompanying paper, scRNA-seq only samples a small proportion of the total transcript pool of each cell. In our example, the total number of genes detected was ~12,000 along with ~2,000 non-coding RNAs. The number of genes per cell averaged ~ 1,500.

Acknowledgments

M.S. is funded by a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) intramural research award.

References

- Aicher TP, Carroll S, Raddi G, Gierahn T, Wadsworth MH 2nd, Hughes TK, Love C, and Shalek AK (2019). Seq-Well: A Sample-Efficient, Portable Picowell Platform for Massively Parallel Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Methods Mol Biol 1979, 111–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen AM, Neville MC, Birtles S, Croset V, Treiber CD, Waddell S, and Goodwin SF (2020). A single-cell transcriptomic atlas of the adult Drosophila ventral nerve cord. Elife 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alles J, Karaiskos N, Praktiknjo SD, Grosswendt S, Wahle P, Ruffault PL, Ayoub S, Schreyer L, Boltengagen A, Birchmeier C, et al. (2017). Cell fixation and preservation for droplet-based single-cell transcriptomics. BMC Biol 15, 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakken TE, Hodge RD, Miller JA, Yao Z, Nguyen TN, Aevermann B, Barkan E, Bertagnolli D, Casper T, Dee N, et al. (2018). Single-nucleus and single-cell transcriptomes compared in matched cortical cell types. PLoS One 13, e0209648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berck ME, Khandelwal A, Claus L, Hernandez-Nunez L, Si G, Tabone CJ, Li F, Truman JW, Fetter RD, Louis M, et al. (2016). The wiring diagram of a glomerular olfactory system. Elife 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke P, Anders S, Kim JK, Kolodziejczyk AA, Zhang X, Proserpio V, Baying B, Benes V, Teichmann SA, Marioni JC, et al. (2013). Accounting for technical noise in single-cell RNA-seq experiments. Nat Methods 10, 1093–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent JR, Werner KM, and McCabe BD (2009). Drosophila larval NMJ dissection. J Vis Exp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet Avalos C, Maier GL, Bruggmann R, and Sprecher SG (2019). Single cell transcriptome atlas of the Drosophila larval brain. Elife 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Zhou W, Steemers F, Trapnell C, and Shendure J (2020). Sci-fate characterizes the dynamics of gene expression in single cells. Nat Biotechnol 38, 980–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caygill EE, and Brand AH (2016). The GAL4 System: A Versatile System for the Manipulation and Analysis of Gene Expression. Methods Mol Biol 1478, 33–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croset V, Treiber CD, and Waddell S (2018). Cellular diversity in the Drosophila midbrain revealed by single-cell transcriptomics. Elife 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie K, Janssens J, Koldere D, De Waegeneer M, Pech U, Kreft L, Aibar S, Makhzami S, Christiaens V, Bravo Gonzalez-Blas C, et al. (2018). A Single-Cell Transcriptome Atlas of the Aging Drosophila Brain. Cell 174, 982–998 e920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Adiconis X, Simmons SK, Kowalczyk MS, Hession CC, Marjanovic ND, Hughes TK, Wadsworth MH, Burks T, Nguyen LT, et al. (2020). Systematic comparison of single-cell and single-nucleus RNA-sequencing methods. Nat Biotechnol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, and Gingeras TR (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler K, Li F, Litwin-Kumar A, Park Y, Andrade I, Schneider-Mizell CM, Saumweber T, Huser A, Eschbach C, Gerber B, et al. (2017). The complete connectome of a learning and memory centre in an insect brain. Nature 548, 175–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam S, Kjallquist U, Moliner A, Zajac P, Fan JB, Lonnerberg P, and Linnarsson S (2011). Characterization of the single-cell transcriptional landscape by highly multiplex RNA-seq. Genome Res 21, 1160–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam S, Kjallquist U, Moliner A, Zajac P, Fan JB, Lonnerberg P, and Linnarsson S (2012). Highly multiplexed and strand-specific single-cell RNA 5’ end sequencing. Nat Protoc 7, 813–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel JM, Poulain DA, and Oliet SH (2010). Glutamatergic inputs contribute to phasic activity in vasopressin neurons. J Neurosci 30, 1221–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AM, Mazutis L, Akartuna I, Tallapragada N, Veres A, Li V, Peshkin L, Weitz DA, and Kirschner MW (2015). Droplet barcoding for single-cell transcriptomics applied to embryonic stem cells. Cell 161, 1187–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziejczyk AA, Kim JK, Svensson V, Marioni JC, and Teichmann SA (2015). The technology and biology of single-cell RNA sequencing. Mol Cell 58, 610–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinides N, Kapuralin K, Fadil C, Barboza L, Satija R, and Desplan C (2018). Phenotypic Convergence: Distinct Transcription Factors Regulate Common Terminal Features. Cell 174, 622–635 e613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer MC, Jung C, Batelli S, Rubin GM, and Gaul U (2017). The glia of the adult Drosophila nervous system. Glia 65, 606–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafzi A, Moutinho C, Picelli S, and Heyn H (2018). Tutorial: guidelines for the experimental design of single-cell RNA sequencing studies. Nat Protoc 13, 2742–2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H (2020). Single-cell RNA sequencing in Drosophila: Technologies and applications . Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol, e396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Cheng Z, Zhou L, Darmanis S, Neff NF, Okamoto J, Gulati G, Bennett ML, Sun LO, Clarke LE, et al. (2019). Developmental Heterogeneity of Microglia and Brain Myeloid Cells Revealed by Deep Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Neuron 101, 207–223 e210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan H, Peabody NC, Vinson CR, and White BH (2006). Refined spatial manipulation of neuronal function by combinatorial restriction of transgene expression. Neuron 52, 425–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macosko EZ, Basu A, Satija R, Nemesh J, Shekhar K, Goldman M, Tirosh I, Bialas AR, Kamitaki N, Martersteck EM, et al. (2015). Highly Parallel Genome-wide Expression Profiling of Individual Cells Using Nanoliter Droplets. Cell 161, 1202–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]