Abstract

Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF) characterizes individuals with interstitial lung disease (ILD) and features of connective tissue disease (CTD) who fail to satisfy CTD criteria. Inclusion of myositis-specific antibodies (MSAs) in the IPAF criteria has generated controversy, as these patients also meet proposed criteria for an anti-synthetase syndrome. Whether MSAs and myositis associated antibodies (MAA) identify phenotypically distinct IPAF subgroups remains unclear.

A multi-center, retrospective investigation was conducted to assess clinical features and outcomes in patients meeting IPAF criteria stratified by the presence of MSAs and MAAs. IPAF subgroups were compared to cohorts of patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy-ILD (IIM-ILD), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and non-IIM CTD-ILDs. The primary endpoint assessed was three-year transplant-free survival.

Two hundred sixty-nine patients met IPAF criteria, including 35 (13%) with MSAs and 65 (24.2%) with MAAs. Survival was highest among patients with IPAF-MSA and closely approximated those with IIM-ILD. Survival did not differ between IPAF-MAA and IPAF without MSA/MAA cohorts. Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) morphology was associated with differential outcome risk, with IPAF patients with non-UIP morphology approximating survival observed in non-IIM CTD-ILDs.

MSAs, but not MAAs identified a unique IPAF phenotype characterized by clinical features and outcomes similar to IIM-ILD. UIP morphology was a strong predictor of outcome in others meeting IPAF criteria. Because IPAF is a research classification without clear treatment approach, these findings suggest MSAs should be removed from the IPAF criteria and such patients should be managed as an IIM-ILD.

Introduction

A sizeable minority of patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) display features of a connective tissue disease (CTD) but fail to meet established CTD criteria.(1–3) Such patients are often classified as having interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF) after the 2015 publication of a research guideline coining the term and proposing standardized classification criteria.(4) Several groups, including ours, have characterized large IPAF cohorts and identified clinical, genetic and molecular determinants of outcomes in these patients.(5–9)

Clinical, serologic and morphologic features comprising the IPAF criteria were selected for their association with CTD, but some criterion have been shown to more strongly predict a CTD-like disease trajectory than others.(9) These include features within the clinical domain and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) and surgical lung biopsy (SLB) features within the morphologic domain. Data assessing the association between serologic domain features and outcomes have been mixed,(9, 10) but low autoantibody prevalence often precludes robust hypothesis testing. Among these autoantibodies are myositis-specific antibodies (MSAs) and myositis-associated antibodies (MAAs), which are commonly found in patients with an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) and have variable association with inflammatory ILD.(11) Inclusion of MSAs in the IPAF criteria has generated controversy,(12–15) as patients with an MSA who fail to meet established criteria for an IIM often meet proposed criteria for an anti-synthetase syndrome.(16)

While there exists no gold standard confirming autoimmune disease among patients meeting IPAF criteria, subgroups with similar phenotypic features and outcomes as those with established CTD are more likely to have an occult CTD. Identifying these subgroups has treatment implications, as those with an inflammatory CTD-like phenotype may be best suited to receive immunosuppressive therapy, while anti-fibrotic therapy may be a better choice for those meeting IPAF criteria with a progressive fibrosing phenotype.(17) In this multi-center investigation, we assessed whether patients meeting IPAF criteria with MSAs (IPAF-MSA) or isolated MAAs without MSAs (IPAF-MAA) displayed distinct phenotypes compared to others meeting IPAF criteria without MSA/MAA. We hypothesized that IPAF-MSA and IPAF-MAA cohorts would demonstrate clinical features and outcomes similar to patients with IIM-ILD.

Methods

This investigation was conducted at the University of California at Davis (UC-Davis), University of Chicago (UChicago) and University of Texas-Southwestern (UTSW) and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each institution (UC-Davis protocol #875917, UChicago protocol #14163 and UTSW protocol #082010–127). ILD registries at each institution were used to identify all patients with longitudinal follow-up diagnosed with CTD-ILD or an idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP). IPAF criteria were systematically applied to all patients with an IIP at each institution using recently described methods by Newton et al.(8) A subset of patients meeting IPAF criteria from UChicago and UTSW have been previously characterized.(8, 9) MSAs were assessed at UC-Davis and UTSW using the Extended Myositis Panel (ARUP laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT) and at UChicago using the MyoMarker Panel (Mayo Clinical Laboratories, Rochester, MN). MSAs tested included Jo-1, PL7, PL12, EJ, OJ, Mi-2, SRP, NXP2, TIF1γ, SAE and MDA-5. Clinical assays used in our centers did not test for uncommonly encountered MSAs, including SC, JS, YRS, Zo, or HMGR antibodies. MAAs assessed included SSA60, SSA52, RNP (U1, U2 and U3 subtypes), Ku and Pm/Scl.(18)

The electronic medical record for all patients with IIM-ILD and IPAF-MSA was then reviewed by a rheumatologist at each institution (IBV, EJ, HS) and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)/American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for IIM applied using available data(19). Patients with a EULAR/ACR score ≥5.5 were classified as IIM-ILD and those with a score <5.5 were classified as IPAF-MSA assuming another IPAF domain was satisfied. Myositis antibody testing was performed prospectively for all but six patients (due to specimen clotting) with an IIP in the UCD cohort who met either the clinical or morphologic domain for IPAF. Myositis antibody testing was performed at the discretion of the treating physician in the UChicago and UTSW cohorts. CTD-ILD diagnoses other than IIM-ILD were determined by local investigators at each institution and were not reviewed for the purposes of this study. Patients were then stratified into six groups - IPAF without MSA/MAA, IPAF-MSA, IPAF-MAA, IIM-ILD, non-IIM CTD-ILD and IPF.

Other pertinent data collected included HRCT and surgical lung biopsy (SLB) morphology, which was determined by a chest radiologist and pulmonary pathologist, respectively, at each institution. Other data collected included pulmonary function testing, including forced vital capacity (FVC) and diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO), immunosuppressant exposure, defined as treatment with mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide and/or rituximab, and outcomes, including death and lung transplantation. Vital status was determined using review of medical records and telephone communication with patients and family members.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are reported as their means with standard deviations (SD) or median with interquartile range and were compared using a two-tailed Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test, as appropriate. Categorical variables were reported as counts and percentages and compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Unadjusted log rank testing along with univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression were used to assess the primary endpoint of three-year transplant-free survival (TFS), which accounted for shorter follow-up time in the UC-Davis cohort. Multivariable models were adjusted for center, race/ethnicity, usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) morphology on HRCT or SLB, immunosuppressant exposure and (gender, age, physiology) GAP score.(20) Survival was plotted using the Kaplan-Meier survival estimator. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp. 2015. Release 16. College Station, TX).

Results

Across institutions, 1361 and 366 patients with IIP and CTD-ILD were identified, respectively. Among those with an IIP, 770 had IPF and 269 met criteria for IPAF, including 35 (13%) patients with IPAF-MSA and 65 (24%) with IPAF-MAA (Figure S1). Among those with CTD-ILD, 70 (19%) had IIM-ILD and 296 (81%) had a non-IIM CTD-ILD. When assessing baseline characteristics for IPAF subgroups (Table 1), those with IPAF-MSA had a lower mean age, fewer white subjects and less UIP on HRCT and SLB when compared to those with IPAF without MSA/MAA. Except for a lower proportion of white subjects, those with IPAF-MAA were similar to those with IPAF without MSA/MAA.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics among patients meeting IPAF criteria stratified by presence of myositis antibodies

| IPAF without MSA/MAA (n=169)* | IPAF-MSA (n=35)** | p vs IPAF w/o MSA/MAA | IPAF-MAA (n=65)*** | p vs IPAF w/o MSA/MAA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 63.3 (11.2) | 58.6 (14.2) | 0.03 | 64.1 (12.9) | 0.69 |

| Male, n (%) | 77 (45.6) | 12 (34.3) | 0.22 | 25 (38.95 | 0.33 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||||

| White | 139 (82.3) | 20 (57.1) | 0.01 | 38 (58.5) | 0.002 |

| African American | 15 (8.9) | 7 (20.0) | 13 (20.0) | ||

| Hispanic | 8 (4.7) | 5 (14.3) | 9 (13.8) | ||

| Asian | 5 (3.0) | 3 (8.6) | 5 (7.7) | ||

| Mixed | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Ever smoker, n (%) | 90 (53.3) | 13 (37.1) | 0.08 | 34 (52.3) | 0.89 |

| HRCT Pattern, n (%) | |||||

| Usual Interstitial Pneumonia | 65 (38.7) | 5 (14.3) | 0.001 | 23 (35.9) | 0.45 |

| Non-specific Interstitial Pneumonia | 58 (34.5) | 13 (37.1) | 28 (43.8) | ||

| Non-specific Interstitial Pneumonia with Organizing | |||||

| Pneumonia | 12 (7.1) | 5 (14.3) | 5 (7.8) | ||

| Organizing Pneumonia | 3 (1.8) | 5 (14.3) | 2 (3.1) | ||

| Unclassifiable/Other | 30 (17.9) | 7 (20.0) | 6 (9.4) | ||

| SLB Pattern | |||||

| Usual Interstitial Pneumonia | 57 (64.8) | 4 (28.6) | 0.03 | 15 (44.1) | 0.19 |

| Non-specific Interstitial Pneumonia | 17 (19.3) | 4 (28.6) | 10 (29.4) | ||

| Organizing Pneumonia | 8 (9.1) | 3 (21.4) | 5 (14.7) | ||

| Unclassifiable/Other | 6 (6.8) | 3 (21.4) | 4 (11.8) | ||

| Pulmonary Function | |||||

| Forced vital capacity (% predicted), mean (SD) | 65.2 (19.9) | 63.5 (18.8) | 0.66 | 64.2 (21.1) | 0.74 |

| Diffusion capacity (% predicted), mean (SD) | 45.5 (18.9) | 46.1 (18.8) | 0.86 | 47.9 (19.2) | 0.4 |

| IPAF Domains | |||||

| Clinical domain met, n (%) | 93 (51.7) | 18 (51.4) | 0.95 | 35 (53.0) | 0.69 |

| Serologic domain met, n (%) | 163 (90.6) | 35 (100) | 0.06 | 66 (100) | 0.01 |

| Morphologic domain met, n (%) | 144 (80.0) | 27 (77.1) | 0.65 | 55 (83.3) | 0.65 |

| IPAF Criteria | |||||

| IPAF due to clinical and serologic criteria, n (%) | 36 (20.0) | 8 (22.9) | 0.26 | 11 (16.7) | 0.02 |

| IPAF due to clinical and morphologic criteria, n (%) | 17 (9.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| IPAF due to serologic and morphologic criteria, n (%) | 87 (48.3) | 17 (48.6) | 31 (47.0) | ||

| IPAF due to clinical, serologic and morphologic criteria, n (%) | 40 (22.2) | 10 (28.6) | 24 (36.3) |

Abbreviations: IPAF = interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features; MSA = myositis-specific antibody; MAA = myositis-associated antibody; HRCT = high resolution computed tomography; SLB = surgical lung biopsy; MSA = myositis specific antibody

n when data missing: HRCT n=168; SLB n=88; FVC n=153; DLCO n=149

n when data missing: SLB n=14; FVC n=33; DLCO n=33

n when data missing: HRCT n=64; SLB n=34, FVC n=64, DLCO n=64

When comparing IPAF cohorts across centers (Table S1), substantial heterogeneity was observed with regard to age and race/ethnicity, with older subjects in the UC-Davis cohort, a higher percentage of white subjects in the UTSW cohort and a higher percentage of African Americans in the UChicago cohort. HRCT and SLB patterns also varied, with UIP predominating in the UChicago cohort and NSIP predominating in the UC-Davis and UTSW cohorts. While a higher proportion of patients received immunosuppression at UC-Davis and UTSW than UChicago, outcomes were similar across centers.

Among those meeting IPAF criteria, the most commonly encountered MSAs were anti-PL7 and anti-Mi2 antibodies (n=6 each), followed by anti-PL12 and anti-EJ antibodies (n=5 each) (Table 2). Anti-MDA5 and anti-SRP positivity was observed in 4 patients each. Only 2 patients with IPAF-MSA had an anti-Jo-1 antibody, as most patients with this antibody met ACR/EULAR criteria for an IIM.(19) The most commonly observed MAAs were SSA60 (15.6%) followed by anti-RNP and SSA52 (6.3% each). An MAA was present in 60% (n=21) of patients in the IPAF-MSA cohort. Sixty-five patients had MAAs without MSAs and comprised the IPAF-MAA cohort (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of myositis-specific and associated antibodies in patients meeting IPAF criteria (n=269)

| Myositis-specific antibodies | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Anti-Jo1 | 2 (0.8) |

| Anti-PL7 | 6 (2.3) |

| Anti-PL12 | 5 (1.9) |

| Anti-EJ | 5 (1.9) |

| Anti-OJ | 1 (0.4) |

| Anti-Mi2 | 6 (2.2) |

| Anti-SRP | 4 (1.5) |

| Anti-NXP2 | 1 (0.4) |

| Anti-T1F1γ | 1 (0.4) |

| Anti-MDA5 | 4 (1.5) |

| Total unique IPAF-MSA patients | 35 (13.0) |

| Myositis-associated antibodies | n (%) |

| anti-U1/U2/U3 RNP | 17 (6.3) |

| anti-SSA60 | 42 (15.6) |

| anti-SSA52 | 17 (6.3) |

| anti-Ku | 3 (1.1) |

| anti-PM-Scl | 7 (2.6) |

| Total unique IPAF-MAA patients | 65 (24.2) |

When comparing baseline characteristics, treatments and outcomes between IPAF without MSA/MAA, IPAF-MSA and IIM-ILD cohorts (Table 3), those with IPAF-MSA showed more similarity with the IIM-ILD cohort than the IPAF without MSA/MAA cohort. A UIP pattern was observed in a significantly lower proportion of patients with IPAF-MSA on HRCT (14.3% vs 38.7, respectively; p=0.006) and SLB (28.6% vs 64.8%, respectively; p=0.02) than IPAF without MSA/MAA. Immunosuppression was also prescribed in a significantly higher proportion of patients with IPAF-MSA compared to IPAF without MSA/MAA (74.3% vs 37.3%, respectively; p<0.001) and death or transplant occurred in a significantly lower proportion of patients with IPAF-MSA compared to IPAF without MSA/MAA (5.7% vs 35.5%, respectively; p<0.001). Except for a lower mean age and shorter median follow-up time in the IPAF-MSA cohort, no significant differences were observed between the IPAF-MSA and IIM-ILD cohorts. A marginally higher percentage of patients with IIM-ILD received immunosuppression compared to IPAF-MSA.

Table 3.

Clinical Characteristics, Treatment and Outcomes between IPAF subgroups and an IIM-ILD cohort

| Variable | IPAF without MSA/MAA (n=169) | IPAF-MSA (n=35) | p vs IPAF w/o MSA/MA A | IIM-ILD (n=70) | p vs IPAF - MSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 63.3 (11.2) | 58.6 (14.2) | 0.03 | 53.4 (12.1) | 0.05 |

| Male, n (%) | 77 (45.6) | 12 (34.3) | 0.22 | 26 (37.1) | 0.77 |

| White race/ethnicity, n (%) | 139 (82.3) | 20 (57.1) | 0.001 | 42 (60.0) | 0.78 |

| HRCT Pattern, n (%) | |||||

| Usual Interstitial Pneumonia | 65 (38.7) | 5 (14.3) | 0.006 | 15 (21.7) | 0.36 |

| Non-specific Interstitial | |||||

| Pneumonia/Organizing pneumonia | 73 (43.5) | 23 (65.7) | 0.02 | 42 (60.9) | 0.63 |

| SLB Pattern | |||||

| Usual Interstitial Pneumonia | 57 (64.8) | 4 (28.6) | 0.02 | 6 (30.0) | 1 |

| Non-specific Interstitial | |||||

| Pneumonia/Organizing pneumonia | 25 (28.4) | 7 (50.0) | 0.1 | 13 (65.0) | 0.38 |

| Treatment, n (%) | |||||

| Any Immunosuppressant | 63 (37.3) | 26 (74.3) | <0.001 | 62 (88.6) | 0.06 |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil | 37 (21.9) | 19 (54.3) | 39 (55.7) | ||

| Azathioprine | 37 (21.9) | 16 (45.7) | 37 (52.9) | ||

| Cyclophosphamide | 3 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 5 (7.1) | ||

| Rituximab | 1 (0.6) | 1 (2.9) | 7 (10.0) | ||

| Outcomes | |||||

| Death, n (%) | 50 (29.6) | 2 (5.7) | 0.002 | 2 (2.9) | 0.6 |

| Transplant, n (%) | 10 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 0.22 | 1 (1.4) | 1 |

| Death or Transplant, n (%) | 60 (35.5) | 2 (5.7) | <0.001 | 3 (4.3) | 0.75 |

| Follow-up time, median (IQR) | 28.5 (14.4–36.0) | 32.6 (24.2–36.0) | 0.12 | 36.0 (27.6–36.0) | 0.04 |

Abbreviations: IIM = idiopathic inflammatory myopathy; ILD = interstitial lung disease; IPAF = interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features; MSA = myositis specific antibody; HRCT = high resolution computed tomography; SLB = surgical lung biopsy;

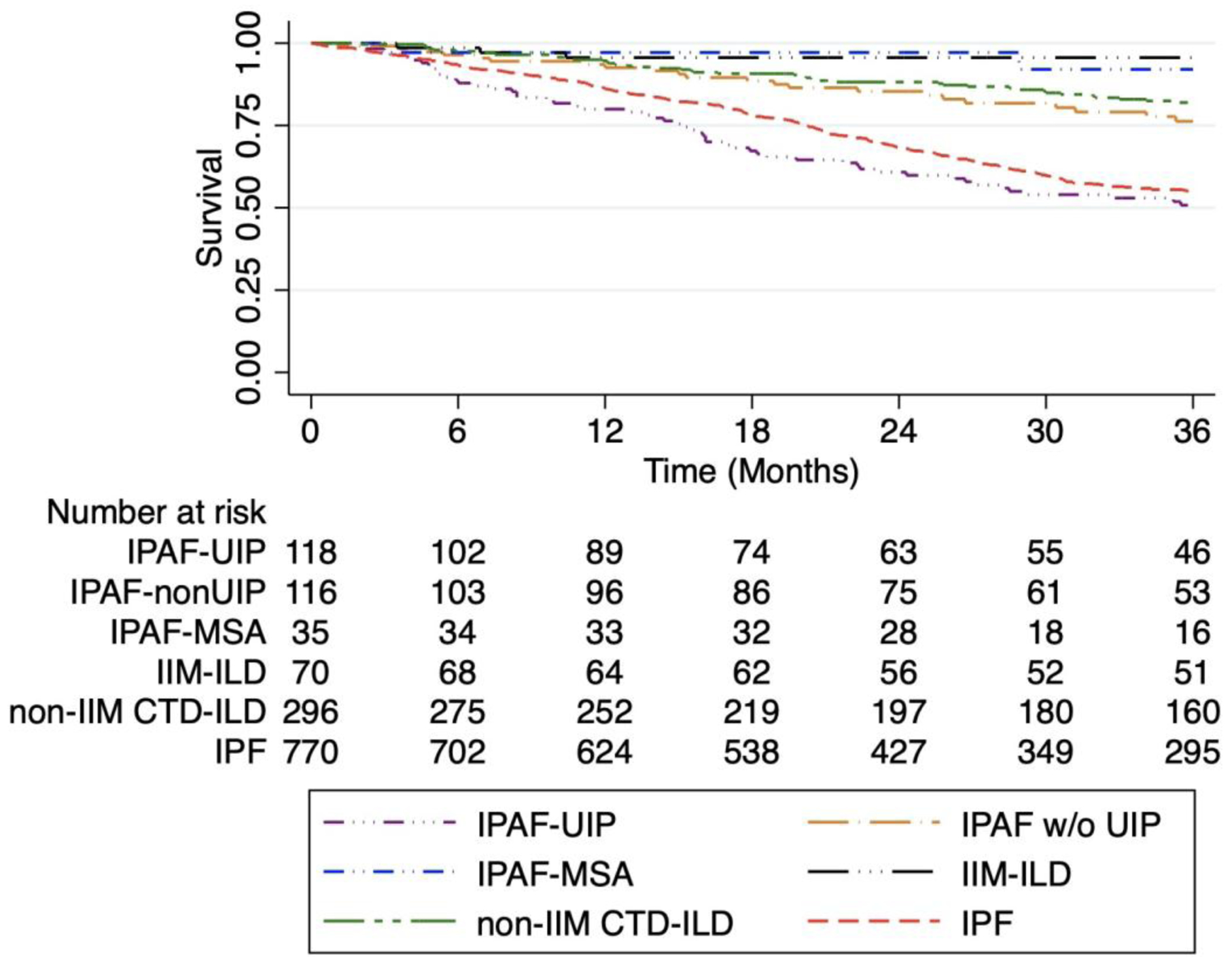

In outcome analysis, the IIM-ILD cohort demonstrated the best overall survival, followed by the non-IIM CTD-ILD, IPAF and IPF cohorts (Figure 1a). When stratifying the IPAF cohort by the presence of MSAs/MAAs, survival was similar between the IPAF-MSA/MAA and the non-IIM CTD-ILD cohorts and between the IPAF without MSA/MAA and IPF cohorts (Figure 1b). Further stratification of IPAF-MSA/MAA into IPAF-MSA and IPAF-MAA cohorts showed that the IPAF-MSA cohort had survival similar to the IIM-ILD, while the IPAF-MAA cohort had survival similar to non-IIM CTD-ILDs (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier survival curve for ILD subgroups without IPAF stratification (a), after IPAF stratification by presence of MSAs/MAAs (b) and after sub stratification of IPAF-MSA and IPAF-MAA (c). Those with IPAF-MSA display survival similar to those with an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy while those with IPAF without MAA/MSA display survival similar to those with IPF.

Compared to the IPAF without MSA/MAA cohort, outcome risk was lower in the IPAF-MSA (HR 0.13, 95% CI 0.03–0.55; p=0.005), IIM-ILD (HR 0.09, 95% CI 0.03–0.30; p<0.001) and other CTD-ILDs (HR 0.37, 95% CI 0.25–0.55; p<0.001). These associations were maintained after multivariable adjustment, with IPAF-MSA and IIM-ILD showing similar effect size (Table 4). Similar effect size and direction were observed for the IPAF-MSA and IIM-ILD cohorts across centers (Table S2). There was no difference in outcome risk between the IPAF without MSA/MAA, IPAF-MAA and IPF cohorts in unadjusted analysis, but outcome risk was lower in the IPF cohort compared to IPAF without MSA/MAA after multivariable adjustment. When assessing individual MAAs in the IPAF-MAA cohort, survival was highest in those with an anti-SSA-52 antibody and anti-Ku antibody and lowest in those with an anti-PM/Scl antibody (p<0.001)(Figure S2).

Table 4.

Outcome risk for ILD subgroups

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 0.13 | 0.03–0.55 | 0.005 | 0.20 | 0.05–0.84 | 0.03 |

| 0.65 | 0.37–1.12 | 0.12 | 0.68 | 0.38–1.21 | 0.19 |

| 0.09 | 0.03–0.30 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 0.05–0.54 | 0.003 |

| 0.37 | 0.25–0.55 | <0.001 | 0.52 | 0.34–0.80 | 0.003 |

| 1.11 | 0.84–1.46 | 0.47 | 0.70 | 0.51–0.97 | 0.03 |

| Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 0.37 | 0.23–0.61 | <0.001 | 0.46 | 0.28–0.78 | 0.004 |

| 0.10 | 0.02–0.41 | 0.001 | 0.14 | 0.03–0.58 | 0.007 |

| 0.07 | 0.02–0.23 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.04–0.42 | 0.001 |

| 0.28 | 0.19–0.42 | <0.001 | 0.43 | 0.27–0.66 | <0.001 |

| 0.83 | 0.62–1.11 | 0.22 | 0.63 | 0.46–0.86 | 0.003 |

Model 1 adjusted for center, race/ethnicity, presence of UIP, immunosuppressant exposure and GAP stage

Model 2 adjusted for center, race/ethnicity, immunosuppressant exposure and GAP stage

Abbreviations: ILD = interstitial lung disease; IPAF = interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features; MSA = myositis specific antibody; IIM-ILD = idiopathic inflammatory myopathy-associated ILD; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Because UIP has been shown to predict differential survival in those meeting IPAF criteria,(9) UIP-stratified survival among IPAF subgroups was then assessed. Outcomes were worse in the setting of UIP morphology compared to non-UIP morphology for the those with IPAF without MSA/MAA (p=0.001)(Figure 2a) and those with IPAF-MAA (p=0.04) (Figure 2b), but not IPAF-MSA (p=0.45)(Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier survival curve based on the presence or absence of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) morphology in those with IPAF without MSA/MAA (a), IPAF-MAA (b) and IPAF-MSA (c). Outcomes were worse in the presence of UIP morphology for IPAF without MSA/MAA and IPAF-MAA cohorts, but not the IPAF-MSA cohort.

Re-stratification of the IPAF cohort into IPAF-MSA (irrespective of UIP), IPAF-UIP and IPAF without UIP identified three distinct IPAF phenotypes that approximated survival observed in IIM-ILD, IPF and CTD-ILD cohorts, respectively (Figure 3). Compared to the IPAF-UIP cohort, outcome risk was significantly lower in the IPAF without UIP, IPAF-MSA, IIM-ILD and non-IIM CTD-ILD cohorts, which persisted after multivariable adjustment (Table 4, Table S3). Outcome risk was similar between IPAF-UIP and IPF cohorts in unadjusted analysis, but lower in those with IPF after multivariable adjustment. When comparing IPAF-UIP and IPF cohorts, those with IPAF-UIP were younger (65.4 vs 68.7 years, respectively; p=0.002) with lower percent predicted FVC (62% vs 68%, respectively; p=0.003) and similar DLCO (45% vs 48%, respectively; p=0.09). A significantly higher proportion of patients with IPAF-UIP were treated with immunosuppressant therapy compared to those with IPF (33.2% vs 9.5%, respectively; p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Kaplan Meier survival curve for ILD subgroups after reclassification of IPAF subgroups. Survival is similar between the IPAF-MSA and IIM-ILD cohorts, between the IPAF without UIP and non-IIM CTD-ILD cohorts and between the IPAF-UIP and IPF cohorts.

Discussion

In this investigation, we showed that patients meeting IPAF criteria with circulating MSAs, but not MAAs, have similar clinical features and outcomes as those with IIM-ILD, making these two groups largely indistinguishable. Large majorities of both groups were treated with immunosuppressive therapy and survival was >90% during the follow-up period. These findings stand in contrast to those patients meeting IPAF criteria without MSAs or MAAs, who demonstrated survival similar to patients with IPF. This observation was largely driven by the presence of UIP however, as patients meeting IPAF criteria with non-UIP morphology on HRCT and/or SLB demonstrated survival similar to patients with non-IIM forms of CTD-ILD irrespective of MAA status. To our knowledge, this study is among the first to assess the clinical implications of MSAs and MAAs in patients meeting IPAF criteria. Because the IPAF clinical course and treatment approaches are poorly defined, our findings support the removal of MSAs from the IPAF criteria and suggest that those with MSA-associated ILD should be managed as an IIM-ILD. Additionally, the strong association between MSAs and favorable outcome supports the acquisition of these antibodies in all patients with IIP irrespective of clinical presentation. This approach is also supported by the most recent American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society IPF diagnostic guideline.(21)

The identification of underlying CTD in patients with ILD is critical, as it informs both treatment and prognosis.(22–26) This can be difficult in practice, as a sizeable minority of patients with CTD may present with isolated ILD or subtle systemic autoimmune manifestations that are difficult to recognize.(3, 27–29) Updated diagnostic criteria for IIM were published in 2017 by the EULAR/ACR.(19) Due to the low frequency of most MSAs, EULAR/ACR criteria did not include MSAs other than anti-Jo-1, despite of the strong association of four other MSAs (anti-Mi-2, anti-SRP, anti-PL-7, anti-PL-12) with IIM.(19, 30) These criteria also failed to recognize ILD as a common manifestation of IIM, leaving the classification of patients with amyopathic, non-Jo-1 anti-synthetase syndrome-associated ILD and IPAF-MSA unclear. While some have argued that the IPAF research classification has filled a vacuum left by the absence of a diagnostic classification for anti-synthetase syndrome,(29) IPAF represents a highly heterogeneous classification without a clear natural history or defined treatment approaches.(14)

Despite significant progress in the characterization of MSAs, the commercially available assays used for their identification are not standardized, lack harmonization between manufactures, and can suffer from low specificity.(30–32) These issues have led to concerns around cost and clinical interpretation as MSA testing has been gradually adopted by the scientific community.(31, 33) Though two different assays were used to assess MSAs in our study, the consistency of our results across institutions with regard to outcomes suggest that these differences did not bias our results. Irrespective of potential differences between MSA assays, these results add to a growing body of literature characterizing MSAs and their association with the clinical phenotype of patients with IIM and ILD.

The most immediate implication of our findings stems from management of patients with IPAF-MSA. While anti-fibrotic therapy was shown to slow lung function decline in patients with progressive ILD,(17) Huapaya and colleagues recently showed that immunosuppressive therapy was associated with long-term disease stability in patients with IIM-ILD, with azathioprine associated with lower concurrent prednisone dose compared to mycophenolate mofetil.(34) Given the similarities observed between IPAF-MSA and IIM-ILD, we propose that a similar treatment approach should be applied to patients with IPAF-MSA. That 75% of IPAF-MSA patients in this study were treated with immunosuppressive therapy suggests that the collective experience of pulmonologists and rheumatologists at our centers has led to a similar approach to patients with MSAs, irrespective of whether they meet criteria for IIM-ILD or IPAF. Whether this experience extends to the community setting is unknown. Because failure to appreciate that IPAF-MSA likely represents an inflammatory, autoimmune-driven process may result in delayed treatment, we favor a unified myositis-associated ILD classification for patients with IIM-ILD and IPAF-MSA. This is supported by the recent findings of Scirè and colleagues, who reported that 42% of patients with MSAs meeting IPAF criteria would ultimately meet CTD criteria within 12 months.(35)

We did not find that presence of MAAs influenced survival in patients meeting IPAF criteria, but this appeared to be MAA-dependent. No events occurred in patients with anti-SSA52 antibodies, while outcomes were poor in those with anti-PM/Scl antibodies. Our results support those published by Sclafani and colleagues, who reported similar outcomes between patients with isolated SSA52 antibodies and those with MSAs with either IIM-ILD or IPAF-MSA.(36) The poor survival we observed in those with anti-PM/Scl antibodies was limited by small sample size, but deserves further attention. Few patients had an anti-Ku antibody, but addition of this antibody to IPAF serologic domain should be considered.

While additional research is needed to identify distinct IPAF treatment groups, our data suggest that anti-fibrotic therapy in patients with IPAF-UIP (without MSAs) would be reasonable. This stems from our observation that those with IPAF-UIP demonstrated worse survival than a large IPF cohort. While the reason underpinning this observation remains unclear, 33% of patients with IPAF-UIP were treated with immunosuppression compared to 9% of patients with IPF. The PANTHER trial(37) showed that patients with IPF treated with immunosuppression had increased risk of death and hospitalization, which may explain our observation. Additionally, patients with IPAF-UIP were also recently shown to have shorter telomere length compared to those meeting IPAF criteria without UIP.(8) Adverse outcomes were significantly higher in IPF patients with short telomere length treated with immunosuppression,(38) which may also explain our findings to some extent.

While UIP predominated among others meeting IPAF criteria, NSIP and/or OP predominated in IPAF-MSA and IIM-ILD cohorts, which is consistent with previous reports.(16, 39) This may explain some of the discordance previously reported between IPAF cohorts with regard to morphologic features and survival. Whereas our prior study of IPAF(9) showed a predominance of UIP and included a single patient with MSAs, these antibodies were present in 35% of the IPAF cohort characterized by Chartrand and colleagues, who showed a predominance of NSIP.(7) Sambataro and colleagues recently characterized a prospective IPAF cohort, which also showed NSIP to be the predominant pattern and included a higher proportion of patients with MSAs, supporting this observation.(40) The demonstrated IPAF heterogeneity underscores the need for more precisely defined groups for whom IPAF criteria should be applied and higher level of objectivity when applying various IPAF criterion.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, this was a retrospective investigation, limiting our conclusions to assessment of association rather than causation. Our data also did not allow for further assessment of the impact of immunosuppression on these IPAF subtypes given the uncontrolled nature of the study. Additionally, the use of prednisone was not captured for this study. Prednisone monotherapy is rarely used to treat patients at our centers, so prednisone use itself was likely to be collinear with dichotomized immunosuppressant exposure in our analysis. However, prednisone dose can vary in patients with IIM-ILD, so inclusion of concurrent prednisone dosage may have influenced our adjusted point estimates in Table 4 to an unknown extent. Next, given the retrospective nature of this study, it was not possible to reliably ascertain the percentage of patients who developed overt IIM-ILD after initially presenting with IPAF-MSA. We did not adjust for multiple testing so one or more of our results may have been incorrectly considered statistically significant by way of Type I error. Despite systematic application of the IPAF criteria, substantial heterogeneity was observed between centers which likely reflects differing IIP populations to which the IPAF criteria are applied and subjectivity in the interpretation of the IPAF criteria. The consistency of results with regard to outcomes in those with IPAF-MSA suggests this heterogeneity is not relevant with regard to this particular research question. Finally, the institutions that contributed to this effort are large ILD referral centers and patients included in this center may not be representative of the community at large. Our regional diversity does likely improve the generalizability of our results, but further research is needed to determine diagnostic and treatment patterns in community settings for patients meeting IPAF criteria.

Conclusions

Our findings supported the hypothesis that IPAF-MSA represents a distinct phenotype among patients meeting IPAF criteria. This phenotype was largely indistinguishable from a sizeable cohort of patients with IIM-ILD, supporting a common diagnostic classification of myositis-associated ILD and treatment approach for both groups. Prospective studies are needed to better define IPAF as a potential diagnostic classification and IIM guidelines should consider incorporating ILD into future diagnostic criteria.

Supplementary Material

Take Home Message:

Myositis-specific antibodies identify a distinct interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features phenotypes characterized by clinical features and outcomes similar to patients with ILD due to an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This manuscript has recently been accepted for publication in the European Respiratory Journal. It is published here in its accepted form prior to copyediting and typesetting by our production team. After these production processes are complete and the authors have approved the resulting proofs, the article will move to the latest issue of the ERJ online.

References

- 1.Cottin V Interstitial lung disease: are we missing formes frustes of connective tissue disease? Eur Respir J 2006; 28: 893–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cottin V Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias with connective tissue diseases features: A review. Respirology 2016; 21: 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer A, West SG, Swigris JJ, Brown KK, du Bois RM. Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease: a call for clarification. Chest 2010; 138: 251–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer A, Antoniou KM, Brown KK, Cadranel J, Corte TJ, du Bois RM, Lee JS, Leslie KO, Lynch DA, Matteson EL, Mosca M, Noth I, Richeldi L, Strek ME, Swigris JJ, Wells AU, West SG, Collard HR, Cottin V, CTD-ILD EATFoUFo. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society research statement: interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. The European respiratory journal 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad K, Barba T, Gamondes D, Ginoux M, Khouatra C, Spagnolo P, Strek M, Thivolet-Bejui F, Traclet J, Cottin V. Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features: Clinical, radiologic, and histological characteristics and outcome in a series of 57 patients. Respir Med 2017; 123: 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alqalyoobi S, Adegunsoye A, Linderholm A, Hrusch C, Cutting C, Ma SF, Sperling A, Noth I, Strek ME, Oldham JM. Circulating Plasma Biomarkers of Progressive Interstitial Lung Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 201: 250–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chartrand S, Lee JS, Fischer A. Longitudinal assessment of interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features is encouraged. Respir Med 2017; 132: 267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newton CA, Oldham JM, Ley B, Anand V, Adegunsoye A, Liu G, Batra K, Torrealba J, Kozlitina J, Glazer C, Strek ME, Wolters PJ, Noth I, Garcia CK. Telomere length and genetic variant associations with interstitial lung disease progression and survival. Eur Respir J 2019; 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oldham JM, Adegunsoye A, Valenzi E, Lee C, Witt L, Chen L, Husain AN, Montner S, Chung JH, Cottin V, Fischer A, Noth I, Vij R, Strek ME. Characterisation of patients with interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 1767–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito Y, Arita M, Kumagai S, Takei R, Noyama M, Tokioka F, Nishimura K, Koyama T, Notohara K, Ishida T. Serological and morphological prognostic factors in patients with interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. BMC Pulm Med 2017; 17: 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lega JC, Reynaud Q, Belot A, Fabien N, Durieu I, Cottin V. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and the lung. Eur Respir Rev 2015; 24: 216–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jee AS, Bleasel JF, Adelstein S, Keir GJ, Corte TJ. A call for uniformity in implementing the IPAF (interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features) criteria. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 1811–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JS, Fischer A. POINT: Does Interstitial Pneumonia With Autoimmune Features Represent a Distinct Class of Patients With Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonia? Yes. Chest 2019; 155: 258–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oldham JM, Danoff SK. COUNTERPOINT: Does Interstitial Pneumonia With Autoimmune Features Represent a Distinct Class of Patients With Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonia? No. Chest 2019; 155: 260–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strek ME, Oldham JM, Adegunsoye A, Vij R. A call for uniformity in implementing the IPAF (interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features) criteria. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 1813–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connors GR, Christopher-Stine L, Oddis CV, Danoff SK. Interstitial lung disease associated with the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: what progress has been made in the past 35 years? Chest 2010; 138: 1464–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flaherty KR, Wells AU, Cottin V, Devaraj A, Walsh SLF, Inoue Y, Richeldi L, Kolb M, Tetzlaff K, Stowasser S, Coeck C, Clerisme-Beaty E, Rosenstock B, Quaresma M, Haeufel T, Goeldner RG, Schlenker-Herceg R, Brown KK, Investigators IT. Nintedanib in Progressive Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Diseases. N Engl J Med 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Satoh M, Tanaka S, Ceribelli A, Calise SJ, Chan EK. A Comprehensive Overview on Myositis-Specific Antibodies: New and Old Biomarkers in Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2017; 52: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lundberg IE, Tjärnlund A, Bottai M, Werth VP, Pilkington C, Visser M, Alfredsson L, Amato AA, Barohn RJ, Liang MH, Singh JA, Aggarwal R, Arnardottir S, Chinoy H, Cooper RG, Dankó K, Dimachkie MM, Feldman BM, Torre IG, Gordon P, Hayashi T, Katz JD, Kohsaka H, Lachenbruch PA, Lang BA, Li Y, Oddis CV, Olesinska M, Reed AM, Rutkowska-Sak L, Sanner H, Selva-O’Callaghan A, Song YW, Vencovsky J, Ytterberg SR, Miller FW, Rider LG, International Myositis Classification Criteria Project consortium TeEraTJDCBSaRJUaI. 2017 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76: 1955–1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryerson CJ, Vittinghoff E, Ley B, Lee JS, Mooney JJ, Jones KD, Elicker BM, Wolters PJ, Koth LL, King TE Jr., Collard HR. Predicting survival across chronic interstitial lung disease: the ILD-GAP model. Chest 2014; 145: 723–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, Richeldi L, Ryerson CJ, Lederer DJ, Behr J, Cottin V, Danoff SK, Morell F, Flaherty KR, Wells A, Martinez FJ, Azuma A, Bice TJ, Bouros D, Brown KK, Collard HR, Duggal A, Galvin L, Inoue Y, Jenkins RG, Johkoh T, Kazerooni EA, Kitaichi M, Knight SL, Mansour G, Nicholson AG, Pipavath SNJ, Buendia-Roldan I, Selman M, Travis WD, Walsh S, Wilson KC, American Thoracic Society ERSJRS, Latin American Thoracic S. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 198: e44–e68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer A, Brown KK, Du Bois RM, Frankel SK, Cosgrove GP, Fernandez-Perez ER, Huie TJ, Krishnamoorthy M, Meehan RT, Olson AL, Solomon JJ, Swigris JJ. Mycophenolate mofetil improves lung function in connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. J Rheumatol 2013; 40: 640–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navaratnam V, Ali N, Smith CJ, McKeever T, Fogarty A, Hubbard RB. Does the presence of connective tissue disease modify survival in patients with pulmonary fibrosis? Respir Med 2011; 105: 1925–1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oldham JM, Lee C, Valenzi E, Witt LJ, Adegunsoye A, Hsu S, Chen L, Montner S, Chung JH, Noth I, Vij R, Strek ME. Azathioprine response in patients with fibrotic connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. Respir Med 2016; 121: 117–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park JH, Kim DS, Park IN, Jang SJ, Kitaichi M, Nicholson AG, Colby TV. Prognosis of fibrotic interstitial pneumonia: idiopathic versus collagen vascular disease-related subtypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175: 705–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Clements PJ, Furst DE, Khanna D, Kleerup EC, Goldin J, Arriola E, Volkmann ER, Kafaja S, Silver R, Steen V, Strange C, Wise R, Wigley F, Mayes M, Riley DJ, Hussain S, Assassi S, Hsu VM, Patel B, Phillips K, Martinez F, Golden J, Connolly MK, Varga J, Dematte J, Hinchcliff ME, Fischer A, Swigris J, Meehan R, Theodore A, Simms R, Volkov S, Schraufnagel DE, Scholand MB, Frech T, Molitor JA, Highland K, Read CA, Fritzler MJ, Kim GHJ, Tseng CH, Elashoff RM, Sclerodema Lung Study III. Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): a randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4: 708–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corte TJ, Copley SJ, Desai SR, Zappala CJ, Hansell DM, Nicholson AG, Colby TV, Renzoni E, Maher TM, Wells AU. Significance of connective tissue disease features in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2012; 39: 661–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vij R, Noth I, Strek ME. Autoimmune-featured interstitial lung disease: a distinct entity. Chest 2011; 140: 1292–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilfong EM, Lentz RJ, Guttentag A, Tolle JJ, Johnson JE, Kropski JA, Kendall PL, Blackwell TS, Crofford LJ. Interstitial Pneumonia With Autoimmune Features: An Emerging Challenge at the Intersection of Rheumatology and Pulmonology. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018; 70: 1901–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tjärnlund A, Lundberg IE. Response to: ‘Response to: ‘Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and antisynthetase syndrome: contribution of antisynthetase antibodies to improve current classification criteria’ by Greco. Ann Rheum Dis 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Infantino M, Tampoia M, Fabris M, Alessio MG, Previtali G, Pesce G, Deleonardi G, Porcelli B, Musso M, Grossi V, Benucci M, Manfredi M, Bizzaro N. Combining immunofluorescence with immunoblot assay improves the specificity of autoantibody testing for myositis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019; 58: 1239–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahler M, Fritzler MJ. Detection of myositis-specific antibodies: additional notes. Ann Rheum Dis 2019; 78: e45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vulsteke JB, De Langhe E, Claeys KG, Dillaerts D, Poesen K, Lenaerts J, Westhovens R, Van Damme P, Blockmans D, De Haes P, Bossuyt X. Detection of myositis-specific antibodies. Ann Rheum Dis 2019; 78: e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huapaya JA, Silhan L, Pinal-Fernandez I, Casal-Dominguez M, Johnson C, Albayda J, Paik JJ, Sanyal A, Mammen AL, Christopher-Stine L, Danoff SK. Long-Term Treatment With Azathioprine and Mycophenolate Mofetil for Myositis-Related Interstitial Lung Disease. Chest 2019; 156: 896–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scire CA, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Selva-O’Callaghan A, Cavagna L. Clinical spectrum time course of interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features in patients positive for antisynthetase antibodies. Respir Med 2017; 132: 265–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sclafani A, D’Silva KM, Little BP, Miloslavsky EM, Locascio JJ, Sharma A, Montesi SB. Presentations and outcomes of interstitial lung disease and the anti-Ro52 autoantibody. Respir Res 2019; 20: 256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research N, Raghu G, Anstrom KJ, King TE Jr., Lasky JA, Martinez FJ. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1968–1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newton CA, Zhang D, Oldham JM, Kozlitina J, Ma SF, Martinez FJ, Raghu G, Noth I, Garcia CK. Telomere Length and Use of Immunosuppressive Medications in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 200: 336–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chartrand S, Swigris JJ, Stanchev L, Lee JS, Brown KK, Fischer A. Clinical features and natural history of interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features: A single center experience. Respir Med 2016; 119: 150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambataro G, Sambataro D, Torrisi SE, Vancheri A, Colaci M, Pavone M, Pignataro F, Del Papa N, Palmucci S, Vancheri C. Clinical, serological and radiological features of a prospective cohort of Interstitial Pneumonia with Autoimmune Features (IPAF) patients. Respir Med 2019; 150: 154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.