Abstract

It is important to pay attention to the indirect effects of the social distancing implemented to prevent the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on children and adolescent health. The aim of the present study was to explore impacts of a reduction in physical activity caused by COVID-19 outbreak in pediatric patients diagnosed with obesity. This study conducted between pre-school closing and school closing period and 90 patients aged between 6- and 18-year-old were included. Comparing the variables between pre-school closing period and school closing period in patients suffering from obesity revealed significant differences in variables related to metabolism such as body weight z-score, body mass index z-score, liver enzymes and lipid profile. We further evaluated the metabolic factors related to obesity. When comparing patients with or without nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), only hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was the only difference between the two time points (p < 0.05). We found that reduced physical activity due to school closing during COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated obesity among children and adolescents and negatively affects the HbA1C increase in NAFLD patients compared to non-NAFLD patients.

Subject terms: Endocrinology, Medical research

Introduction

The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led governments of affected countries to impose strict confinement rules, that is social distancing, on their citizens including children and adolescents. All citizens in the Republic of Korea have been asked to restrict their social interactions and live under home-confinement for several months since February 2020. School classes have been replaced by online classes according to the social distancing and stay-at-home orders. The result of these policies has led to social, economic, psychological, and health implications.

It is important to pay attention to the indirect effects of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescent health caused by compulsory sedentary lifestyle. It is reported that there were decreased physical activity and weight gain in 56.7% of school-aged children and adolescents in the Republic of Korea during COVID-19 pandemic1. The school closing due to COVID-19 pandemic may reduce physical activity and aggravate obesity and increase the risk of other metabolic diseases in pediatric population. However, there are scarce data on the impact of COVID-19 related school closing on pediatric health.

Obesity occurs as the result of interactions between genetic and environmental factors2–4; however, school and out-of-school environments related to decreased physical activity are factors that may contribute to pediatric obesity in school-aged children5–7. Von Hippel et al. described that non-school environments contribute to excessive weight gain in childhood5, and Smith reported that children who have overweight or obesity tend to have more weight gain and increase in body mass index (BMI) compared to children who have normal weight during out-of-school period7. Other studies have also revealed metabolic impact of summer vacation or holiday on childhood obesity in terms of aggravating obesity since children have less opportunity for group exercise due to absence of physical education classes and school activities during vacation6,8–12.

There are well documented long-term effects of childhood obesity including asthma, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension13–15. Recent studies have emphasized that obesity can lead to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and metabolic syndrome and diabetes, which can persist into adulthood16,17. Therefore, efforts should be focused primarily on preventing, reducing and treating childhood and adolescent obesity.

The primary aim of the present study was to investigate change of laboratory results (e.g. liver enzymes, lipid profile, and hemoglobin A1c; HbA1c) according to the reduction in physical activity in pediatric patients with obesity during the period of school closing caused by COVID-19 outbreak. The secondary aim of this study was to evaluate the indirect metabolic effects of sedentary life style caused by COVID-19 outbreak in patients diagnosed with NAFLD among pediatric patients with obesity.

Materials and methods

Patients and data collection

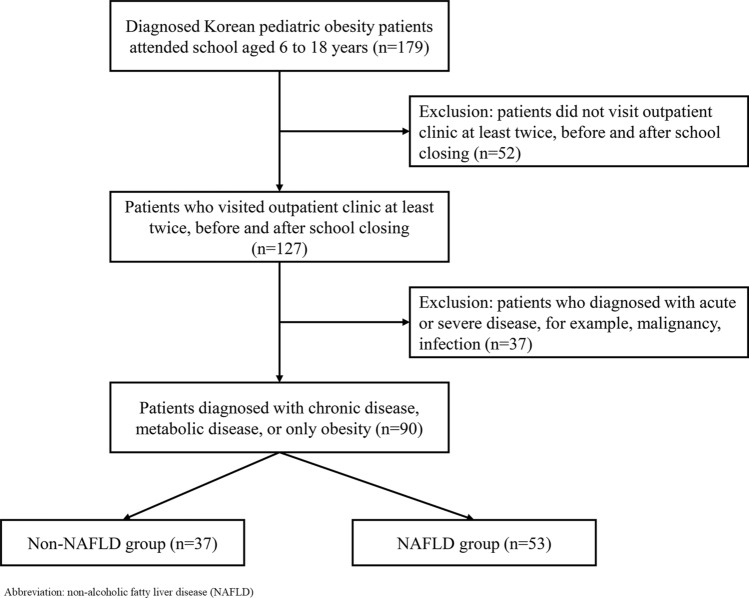

This study was a retrospective observational study conducted at the Department of Pediatrics of Samsung Medical Center between December 2019 and May 2020. The subjects were pediatric patients with obesity who attended school between aged 6 and 18, and visited the outpatient clinic at least twice before and during school closing period due to COVID-19 outbreak. During the study period, subjects were all at their homes because their school program was suspended due to COVID-19 outbreak. It was assumed that pre-school closing was from December 2019 to February 2020 and school closing was from March 2020 to May 2020. Patients were identified through a search of our electronic medical records system. In the database search, we identified 179 school-aged patients diagnosed with obesity and the number of patients visited outpatient clinic at least twice before and after social distancing was 127. Then, 37 patients were excluded because of alternative etiologies for elevated liver enzymes, and 90 patients were eligible for analysis finally (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

Demographic and clinical data including sex, age, body weight, height, and BMI were collected before and after school closing. BMI was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). Z-scores for body weight and BMI were calculated based on the 2017 Korean National Growth Charts for children and adolescents18. Data at each visit to the outpatient clinic were collected retrospectively from electronic charts and laboratory results, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), fasting glucose, uric acid, cholesterol, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and HbA1c. We compared data between pre-school closing and during school closing and also according to the presence of NAFLD.

Definitions

Obesity was defined as a BMI above the 95th percentile in children and adolescents in accordance with the Committee on Pediatric Obesity of the Korean Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition19. NAFLD was diagnosed by excluding alternative etiologies for elevated ALT and/or hepatic steatosis, such as medication (amiodarone, glucocorticoids, L-asparaginase, valproic acid) and the presence of co-existing chronic liver disease including Wilson’s disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C20. It is important to note that not all pediatric patients with obesity and chronic elevated liver enzymes are classified as NAFLD. The gold standard for establishing a NAFLD diagnosis is liver biopsy; however, there are the serious limitations to liver biopsy in pediatric patients in the real-world setting. Therefore, NAFLD was diagnosed based on three conditions; elevated ALT (> 50U/L in boys, > 44 U/L in girls)21, increased brightness of the liver parenchyma compared to the kidney in liver ultrasonography conducted by one pediatric radiology specialist20, and excluding other etiologies for hepatic steatosis as described above22.

Statistical analysis

Comparative data for continuous variables are reported as the median with interquartile range (IQR) or mean with standard deviation and for categorical variables with frequency and percentages. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to compare continuous variables while the chi-square test was used for discrete variables. We used paired t-tests to evaluate the significance of changes from pre-school closing to school closing period. In addition, we tested the significance of differences between patients with and without NAFLD in response to changes using independent two-sample t-tests. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Rex (Version 3.0.3, RexSoft Inc., Seoul, Korea).

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Samsung Medical Center and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki23. All patients and parents and/or legal guardian of subjects who are under 18 provided written informed consent. We confirmed that all methods were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines and regulations. We reported and presented data according to the STROBE statement.

Results

Baseline characteristics

During the period from December 2019 to May 2020, a total of 90 pediatric patients with obesity visited the clinic at least two times between the pre-school closing and during school closing period. Table 1 shows descriptive characteristics of subjects at baseline. The mean age of patients at pre-school closing was 12.2 ± 3.4 years and 70 patients (77.8%) were male. The median interval between first visit of outpatient clinic (pre-school closing) and second visit (during school closing) was 4.3 months. Mean body weight z-score was 2.0 and mean BMI z-score was 1.9. At baseline, 53 (58.9%) subjects had NAFLD, 10 (11.1%) had type 2 diabetes mellitus, and 14 (15.6%) had dyslipidemia. In addition, statin usage was observed in 13 subjects (14.4%), metformin usage was in 10 subjects (11.1%), and insulin usage was in 1 subject (1.1%), which was maintained during the study period. Other baseline demographics and clinical characteristics, as well as data collected at diagnosis, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of pediatric patients with obesity.

| Total (n = 90) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12.2 ± 3.4 |

| Male, n (%) | 70 (77.8) |

| Female, n (%) | 20 (22.2) |

| Interval between 1st and 2nd outpatient clinic visit (months) | 4.3 ± 1.8 |

| Body weight (kg) | 67.2 ± 23.8 |

| Body weight z-score | 2.0 ± 0.8 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7 ± 4.6 |

| BMI z-score | 1.9 ± 0.5 |

| Mean arterial pressure | 86.5 ± 9.1 |

| Co-existing diseases, n (%) | |

| NAFLD | 53 (58.9) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 10 (11.1) |

| Dyslipidemia | 14 (15.6) |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome | 2 (10) |

| Medication, n (%) | |

| Statins | 13 (14.4) |

| Metformin | 10 (11.1) |

| Insulin | 1 (1.1) |

| AST (U/L) | 35.2 ± 29.0 |

| ALT (U/L) | 53.0 ± 32.8 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 160.3 ± 33.4 |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 6.4 ± 1.9 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 160.3 ± 33.4 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 126.7 ± 70.0 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 46.9 ± 11.1 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 101.5 ± 31.0 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.0 ± 1.3 |

BMI body mass index, NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, AST aspartate transferase, ALT alanine transferase, HDL high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c.

Comparison of variables between pre-school closing and during school closing in patients with obesity

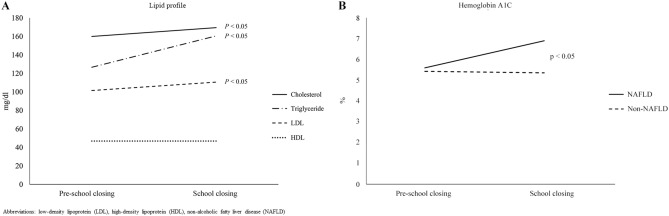

We investigated the changes in growth in weight, height, and BMI and other laboratory results associated with metabolism between the pre-school closing and during school closing. Comparing the variables between pre-school closing period and school closing period in patients suffering from obesity revealed significant differences in variables related to metabolism such as body weight (67.2 ± 23.8 vs. 71.1 ± 24.2, p < 0.001), body weight z-score (2.0 ± 0.8 vs. 2.2 ± 0.7, p < 0.001), BMI (26.7 ± 4.6 vs. 27.7 ± 4.6, p < 0.001), BMI z-score (1.9 ± 0.5 vs. 2.0 ± 0.4, p < 0.001), AST (35.2 ± 29.0 vs. 42.7 ± 33.8, p = 0.0085), ALT (53.0 ± 32.8 vs. 74.7 ± 41.8, p < 0.001). Also, lipid profile such as cholesterol (160.3 ± 33.4 vs. 169.5 ± 36.4, p < 0.001), triglycerides (126.7 ± 70.0 vs. 160.6 ± 94.0, p < 0.001), and LDL (101.5 ± 31.0 vs. 110.6 ± 33.7, p = 0.0016) increased remarkably during school closing compared to pre-school closing. (Fig. 2A). There were no statistically significant differences between the two time points in mean blood pressure (MBP), uric acid, HDL, and HbA1c. Detailed comparison results are presented in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Comparison laboratory results between the pre-school closing and during school closing. (A) Lipid profile, (B) HbA1C between with and without NAFLD group.

Table 2.

Comparison of variables between pre-school closing and during school closing in patients with obesity.

| Pre-school closing | School closing | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (kg) | 67.2 ± 23.8 | 71.1 ± 24.2 | < 0.001 |

| Body weight z-score | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7 ± 4.6 | 27.7 ± 4.6 | < 0.001 |

| BMI z-score | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 86.5 ± 9.1 | 89.2 ± 9.7 | 0.1073 |

| AST (U/L) | 35.2 ± 29.0 | 42.7 ± 33.8 | 0.0085 |

| ALT (U/L) | 53.0 ± 32.8 | 74.7 ± 41.8 | < 0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 160.3 ± 33.4 | 169.5 ± 36.4 | < 0.001 |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 6.4 ± 1.9 | 7.3 ± 10.6 | 0.4684 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 160.3 ± 33.4 | 169.5 ± 36.4 | < 0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 126.7 ± 70.0 | 160.6 ± 94.0 | < 0.001 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 46.9 ± 11.1 | 46.9 ± 10.7 | 0.9715 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 101.5 ± 31.0 | 110.6 ± 33.7 | 0.0016 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.0 ± 1.3 | 7.3 ± 6.0 | 0.1737 |

BMI body mass index, NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, AST aspartate transferase, ALT alanine transferase, HDL high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c.

Comparison of variable differences between patients with and without NAFLD

In this retrospective analysis of 90 pediatric patients with obesity, 53 patients (58.9%) had NAFLD. At the pre-school closing period, the NAFLD group showed higher AST (30 vs. 24, p <0.001), ALT (54 vs. 17, p <0.001), serum uric acid (4.4 vs. 4.0, p <0.001), and HbA1c (5.6 vs. 5.4, p <0.001), and lower LDL (95.2 vs. 109.8, p <0.05) relative to the non-NAFLD group. During the school closing period, the NAFLD group showed higher AST (44 vs. 23, p <0.001), ALT (70 vs. 22, p <0.001), HbA1c (6.9 vs. 5.4, p <0.001), and MBP (98 vs. 86.7, p <0.05) compared to the non-NAFLD group (Table 3). Other detailed comparison results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of variables according to the presence of NAFLD between pre-school closing and during school closing period.

| Variables | Pre-school closing | School closing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAFLD (n = 53) | Non-NAFLD (n = 37) | p value | NAFLD (n = 53) | Non-NAFLD (n = 37) | p value | |

| Age (years) | 12.9 (11.5, 14.6) | 10.3 (7.6, 12.7) | < 0.001 | |||

| Male, n (%) | 45 (84.9) | 25 (67.6) | 0.0912 | |||

| Female, n (%) | 8 (15.1) | 12 (32.4) | 0.0912 | |||

| Body weight z-score | 2.10 (1.74, 2.54) | 1.95 (1.65, 2.51) | 0.6025 | 2.17 (1.89, 2.77) | 2.14 (1.86, 2.57) | 0.9444 |

| BMI z-score | 1.96 (1.61, 2.06) | 1.97 (1.56, 2.28) | 0.6053 | 2.02 (1.76, 2.16) | 1.99 (1.75, 2.30) | 0.5576 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 86.3 (81.2, 89.3) | 85.7 (81.3, 91.7) | 0.9839 | 98.0 (90.3, 101.3) | 86.7 (82.6, 89.3) | 0.0027 |

| AST (U/L) | 30 (23, 41) | 24 (20. 27) | < 0.001 | 44 (31, 59) | 23 (21, 25) | < 0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 54 (35, 71) | 17 (14, 30) | < 0.001 | 70 (53, 117) | 22 (17, 26) | < 0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 97 (90, 104) | 97 (91, 104) | 0.8334 | 101 (93, 116) | 99 (92, 114) | 0.34 |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 5.5 (6.0, 7.2) | 4.9 (3.9, 5.0) | < 0.001 | 6.9 (5.7, 7.7) | 5.7 (4.3, 6.8) | 0.0021 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 151 (136, 171) | 160 (144, 184) | 0.1598 | 157 (142, 177) | 170 (150, 210) | 0.2488 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 118 (71, 138) | 114 (92, 149) | 0.8334 | 147 (85, 217) | 150 (87, 232) | 0.7604 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 47.0 ± 10.4 | 49.7 ± 12.7 | 0.3027 | 45.1 ± 9.0 | 48.5 ± 13.7 | 0.2629 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 95.2 ± 27.8 | 109.8 ± 29.6 | 0.0296 | 101.5 (89.0, 116.5) | 105.5 (89.5, 133.75) | 0.4744 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.6 (5.4, 8.6) | 5.4 (5.2, 5.6) | 0.0029 | 6.9 (5.6, 8.9) | 5.4 (5.3, 5.6) | < 0.001 |

BMI body mass index, NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, AST aspartate transferase, ALT alanine transferase, HDL high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c.

We also compared incremental change (delta value) in each variable at the two time points of pre-school closing and during school closing according to the presence of NAFLD. The delta values were calculated by subtracting the value of the pre-school closing from the value of the school closing period. Comparison of the delta values between patients with or without NAFLD revealed significant difference in only HbA1c levels at the two time points (0.35 vs. 0.05, p < 0.05) except for liver enzymes. There were no other significant differences between the two time points in the NAFLD and non-NAFLD groups (Table 4 and Fig. 2B).

Table 4.

Comparison of difference in each variable at pre-school closing and during school closing according to the presence of NAFLD.

| School closing—pre-school closing | Total (n = 90) | NAFLD group (n = 53) | Non-NAFLD group (n = 37) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| △ BMI z-score | 0.06 (0, 0.12) | 0.06 (0.03, 0.12) | 0.06 (− 0.01, 0.12) | 0.33 |

| △ Body weight z-score | 0.18 (0.1, 0.29) | 0.18 (0.1, 0.25) | 0.17 (0.09, 0.35) | 0.95 |

| △ MAP (mmHg) | 4.33 (− 1.33, 7.33) | 3.67 (− 1.5, 7.33) | 5.33 (0.83, 11) | 0.20 |

| △ Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 9.21 ± 18.06 | 7.3 ± 15.65 | 12.31 ± 21.33 | 0.28 |

| △ AST (U/L) | 4 (− 1.5, 14) | 10 (0, 25) | − 0.5 (− 3.75, 3.75) | < 0.01 |

| △ ALT (U/L) | 8 (0, 35.5) | 17 (3, 59) | 2 (− 1, 7) | < 0.01 |

| △ Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 2 (− 2, 11) | 5 (− 0.5, 13.5) | 0 (− 2.75, 4.75) | 0.16 |

| △ Uric acid (mg/dl) | 0.35 (− 0.2, 0.7) | 0.4 (0, 0.6) | 0.2 (− 0.5, 0.8) | 0.94 |

| △ Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 33.89 ± 61.15 | 26.39 ± 50.59 | 46.71 ± 75.37 | 0.25 |

| △ HDL (mg/dl) | − 0.03 ± 6.87 | − 0.45 ± 6.2 | 0.71 ± 8.01 | 0.54 |

| △ LDL (mg/dl) | 9 (− 3, 14) | 9.5 (− 2.75, 13) | 5 (− 3.25, 16.75) | 0.76 |

| △ HbA1c (%) | 0.1 (0, 0.42) | 0.35 (0.08, 1.55) | 0.05 (0, 0.1) | < 0.05 |

delta, △ Subtracting the value of the pre-social distancing from the value of the social distancing period, BMI body mass index, NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, MAP mean arterial pressure, AST aspartate transferase, ALT alanine transferase, HDL high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c.

Discussion

To date, most studies have described the relationship between life style behaviors affected by COVID-19 and weight gain based on questionnaires, however there is scarce data about children and adolescents24–29. As far as we know, this is the first study to objectively investigate the indirect impact of COVID-19 pandemic on metabolic problems in pediatric patients with obesity using laboratory results.

In this study, the results show that COVID-19 pandemic has had a substantial negative impact on the health in pediatric patients with obesity and its comorbidities regardless of infection status of COVID-19. As a result of the current situation in which almost all people, even children and adolescents, are confined to their homes, physical activity drastically declined while dietary habits remained unchanged or failed to offset physical inactivity. We show that reduced physical activity caused by school closing in COVID-19 pandemic era could lead to a rapid decline in metabolic homeostasis. Notably, during the school closing period, there were remarkable increases in body weight, BMI, and laboratory results related to metabolic disease, such as AST, ALT, triglyceride, and LDL, which were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

In results according to the presence of NAFLD, NAFLD group had significantly higher MBP and HbA1c levels relative to non-NAFLD group during school closing period, which is consistent with other existing studies that reported children affected by obesity and NAFLD had a higher cardiovascular and metabolic risk, including hypertension30,31. In Table 2, HbA1c did not seem to change between before and during school closing; however, when subgroup analysis was performed with or without NAFLD, difference of HbA1c was significantly confirmed between the two time points (Table 3). Furthermore, in accordance with previous studies, children with NAFLD were more susceptible to increases in HbA1c than non-NAFLD pediatric patients caused by reduced physical activity during COVID-19 pandemic (p < 0.05)16. In other words, NAFLD may be an important predisposing factor in pediatric patients with obesity for the development of glucose intolerance, especially in environments with reduced physical activity16,32.

These observations not only recommend that patients with obesity do physical activities such as home training to the extent possible during school closing, but also emphasize that family members and pediatricians should pay attention to the lifestyle of pediatric patients with obesity. Although further studies in post-school closing are needed, aggravated obesity and other metabolic diseases during out-of-school circumstances may not be easily reversible and might contribute to excess adiposity and cardiometabolic or non-cardiometabolic comorbidities, which can persist into adulthood2,19,33.

Previous research has demonstrated that children gained significantly more body weight and showed increased BMI during out-of-school periods5,6,8–12. Some studies have suggested that individual weight gain during the holiday period was quite variable; however, this period is more important especially for those who have already been diagnosed with obesity9,11. Our findings are consistent with those of recent studies and indicate that out-of-school circumstances, such as school closing caused by COVID-19 outbreak, contribute to childhood and adolescent obesity and its comorbidities caused by low physical activity level.

The strength of this study is that body weight, BMI, and laboratory results associated with metabolic disease were objectively compared between two time points, pre-school closing and during school closing. On the other hand, our study has some limitations. First, as a retrospective study, it has certain limitations compared to a prospective design. However, all patients attended an outpatient clinic at least two times between pre-school closing and school closing periods and the extraction of objective clinical and biochemical results from the medical records was possible. Second, the lack of information about subject diet and exercise time is a limitation; however, such information is subjective, thus eliminating potential bias was possible in this study. Third, selection bias may have been introduced as patients who had not visited twice between the two time points were excluded from this study. Therefore, further well-designed prospective post-social distancing studies are required to address these limitations.

In conclusion, we found that reduced physical activity due to social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated obesity among school-aged children and adolescents and negatively affects the HbA1C increase in NAFLD patients compared to non-NAFLD patients. These results lend support to the fact that physical activity is important in the prevention and treatment of obesity. Therefore, physicians should pay attention to life style modification as well as pharmacotherapy and surgery in pediatric patients with obesity. Moreover, physicians should carefully monitor the development of glucose intolerance in pediatric NAFLD patients during physical inactivity periods caused by school closing during COVID-19 pandemic.

Author contributions

ESK contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafting of the initial manuscript, and critical revision for important intellectual content. YYK contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. YHC contributed to the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision for important intellectual content. MJK contributed to the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Data availability

Please contact the corresponding author for data requests.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, Eun Sil Kim, Yiyoung Kwon, Yon Ho Choe and Mi Jin Kim were incorrectly affiliated with ‘Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea’.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

7/6/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-021-93375-6

Contributor Information

Yon Ho Choe, Email: i101016@skku.edu.

Mi Jin Kim, Email: mijin1217.kim@samsung.com.

References

- 1.Lim S, Lim H, Després JP. Collateral damage of the COVID-19 pandemic on nutritional quality and physical activity: perspective from South Korea. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) 2020;28(10):1788–1790. doi: 10.1002/oby.22935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohut T, Robbins J, Panganiban J. Update on childhood/adolescent obesity and its sequela. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2019;31:645–653. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garver WS. Gene-diet interactions in childhood obesity. Curr. Genom. 2011;12(3):180–189. doi: 10.2174/138920211795677903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurnani M, Birken C, Hamilton J. Childhood obesity: causes, consequences, and management. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2015;62(4):821–840. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Hippel PT, Powell B, Downey DB, Rowland NJ. The effect of school on overweight in childhood: gain in body mass index during the school year and during summer vacation. Am. J. Public Health. 2007;97(4):696–702. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Hippel PT, Workman J. From kindergarten through second grade, U.S. children's obesity prevalence grows only during summer vacations. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016;24:2296–2300. doi: 10.1002/oby.21613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith DT, Bartee RT, Dorozynski CM, Carr LJ. Prevalence of overweight and influence of out-of-school seasonal periods on body mass index among American Indian schoolchildren. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2009;6(1):A20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, et al. Summer effects on body mass index (BMI) gain and growth patterns of American Indian children from kindergarten to first grade: a prospective study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:951. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branscum P, Kaye G, Succop P, Sharma M. An evaluation of holiday weight gain among elementary-aged children. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2010;2:167–171. doi: 10.4021/jocmr414w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoeller DA. The effect of holiday weight gain on body weight. Physiol. Behav. 2014;134:66–69. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreno JP, Johnston CA, Woehler D. Changes in weight over the school year and summer vacation: results of a 5-year longitudinal study. J. Sch. Health. 2013;83(7):473–477. doi: 10.1111/josh.12054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diaz-Zavala RG, et al. Effect of the holiday season on weight gain: a narrative review. J. Obes. 2017;2017:2085136. doi: 10.1155/2017/2085136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Technical Report Series894:i–xii, 1–253 (2000). [PubMed]

- 14.Dietz WH, Gortmaker SL. Preventing obesity in children and adolescents. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2001;22:337–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Llewellyn A, Simmonds M, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Childhood obesity as a predictor of morbidity in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2016;17(1):56–67. doi: 10.1111/obr.12316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams LA, Waters OR, Knuiman MW, Elliott RR, Olynyk JK. NAFLD as a risk factor for the development of diabetes and the metabolic syndrome: an eleven-year follow-up study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009;104:861–867. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fabbrini E, Sullivan S, Klein S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: biochemical, metabolic, and clinical implications. Hepatology. 2010;51:679–689. doi: 10.1002/hep.23280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JH, et al. The 2017 Korean National Growth Charts for children and adolescents: development, improvement, and prospects. Korean J. Pediatr. 2018;61:135–149. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2018.61.5.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yi DY, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric obesity: recommendations from the Committee on Pediatric Obesity of the Korean Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2019;22:1–27. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2019.22.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vos MB, et al. NASPGHAN clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children: recommendations from the Expert Committee on NAFLD (ECON) and the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017;64:319–334. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwimmer JB, et al. SAFETY study: alanine aminotransferase cutoff values are set too high for reliable detection of pediatric chronic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1357–1364. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crespo M, Lappe S, Feldstein AE, Alkhouri N. Similarities and differences between pediatric and adult nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2016;65:1161–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almandoz JP, et al. Impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders on weight-related behaviors among patients with obesity. Clin. Obes. 2020;10(10):e12386. doi: 10.1111/cob.12386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pietrobelli A, et al. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle behaviors in children with obesity living in Verona, Italy: a longitudinal study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28(8):1382–1385. doi: 10.1002/oby.22861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rundle AG, Park Y, Herbstman JB, Kinsey EW, Wang YC. COVID-19-related school closings and risk of weight gain among children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:1008–1009. doi: 10.1002/oby.22813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zachary Z, et al. Self-quarantine and weight gain related risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020;14(3):210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He M, Xian Y, Lv X, He J, Ren Y. Changes in body weight, physical activity and lifestyle during the semi-lockdown period after the outbreak of COVID-19 in China: an online survey. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2020;14:1–6. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Workman JA. How much may COVID-19 school closures increase childhood obesity? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28(10):1787. doi: 10.1002/oby.22960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwimmer JB, et al. Longitudinal assessment of high blood pressure in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):e112569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goyal NP, Schwimmer JB. The progression and natural history of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Liver Dis. 2016;20:325–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki A, et al. Chronological development of elevated aminotransferases in a nonalcoholic population. Hepatology. 2005;41:64–71. doi: 10.1002/hep.20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franks PW, et al. Childhood obesity, other cardiovascular risk factors, and premature death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362(6):485–493. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Please contact the corresponding author for data requests.