Abstract

Since the recent discovery of prostaglandin-associated peri-orbitopathy, a great deal of interest has developed concerning the side effects of anti-glaucoma medications toward periocular fatty tissue, especially their adipogenesis. Two- or three-dimension (2D or 3D) cultures of the 3T3-L1 cells were employed to elucidate the effects of the Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase inhibitor (ROCK-i) the anti-glaucoma drug, Ripasudil, and other ROCK-i, such as Y27632 on adipogenesis. Ultrastructure by electron microscopy and physical stiffness measurements by a micro-squeezer demonstrated the 3D organoids had essentially matured during the 7-day culture. The effects of ROCK-i on 3D organoid sizes, lipid staining, the mRNA expression of adipogenesis related genes, Pparγ, Cebpa and Leptin, and extracellular matrix (ECM) including collagen (COL) 1, 4 and 6, and fibronectin, and physical stiffness were then conducted. Upon adipogenesis, the sizes, lipid staining and mRNA expressions of adipogenesis related genes, Col 4 and Col 6 were dramatically increased, and were further enhanced by ROCK-i. Micro-squeezer analysis demonstrated that adipogenesis resulted in a marked less stiffed 3D organoid and this was further enhanced by ROCK-i. Our present study indicates that ROCK-i significantly enhanced the production of large lipid-enriched 3T3-L1 3D organoids.

Subject terms: Cell biology, Molecular biology

Introduction

Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinases (ROCKs), members of the serine-threonine protein kinase family, were first recognized as RhoA-binding proteins that regulate the remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton1,2. The amino acid composition and the carboxyl termini of ROCK 1 (ROKβ) and ROCK 2 (ROKα) are similar and the catalytic kinase domain and the Rho-binding domain (RBD) are also similar but the coiled-coil region of these proteins have a relatively low homology3. Functionally, ROCK isoforms play important roles including the regulation of actin cytoskeleton organization, cytokinesis, differentiation, apoptosis, glucose metabolism, cell adhesion/motility, and inflammation4–7. ROCKs are also distributed within the ocular and surrounding tissues, including the trabecular meshwork, ciliary muscles, and the retina8,9, and are recognized as being involved in the ocular physiology as well as in the pathogenesis of several ocular diseases including cataracts, retinopathy, and corneal dysfunction10–15. These observations, in turn, strongly suggest that ROCKs may be therapeutic targets for these diseases. In fact, ROCK inhibitors (ROCK-i) have recently been shown to reduce intraocular pressure (IOP) in several animal models16,17, and in Japan, Ripasudil hydrochloride hydrate (Rip), a non-selective ROCK-i, is currently being used as a new member of the class of anti-glaucoma medications for the treatment of glaucoma and ocular hypertension18,19.

Among long-term users of prostaglandin analogues (PGs), several recent reports indicated periocular side effects called “prostaglandin-associated peri-orbitopathy (PAP)”, which include deepening of the upper eyelid sulcus (DUES) and others20. As a possible mechanism for causing DUES, it has been suggested that PGs inhibit adipogenesis of the orbital lipid based upon MR imaging findings21. Since DUES has become apparent as periocular side effect caused by PGs, the effects of other anti-glaucoma medications toward periocular tissues, especially orbital fat, has attracted considerable interest. In order to elucidate molecular mechanisms for causing DUES by PGs, we recently replicated DUES models using three-dimension (3D) cell cultures of 3T3-L1 cells22 or human orbital fibroblasts (HOFs)23. The findings indicated that PGs significantly affected their adipogenesis as well as extracellular matrix (ECM) metabolism. Since ROCKs also affect adipogenesis, as evidenced by the in vitro studies as above, further studies of the role of ROCK-i toward adipogenesis in our DUES model is of great interest.

Therefore, in the present study, to report on the effects of the ROCK-is, Rip and Y27632 on the adipogenesis of the 3T3-L1 cells, a most widely used as adipocyte cell line for adipogenesis related research, we studied adipogenesis by lipid staining as well as adipogenesis related gene expressions, their ECM expressions (2D and 3D cell cultures), and sizes and physical stiffness by a micro-squeezer of the 3D organoid. In addition, during the course of the 3D 3T3-L1 organoid culture, their physical properties including the 3D organoid size, appearance by phase contrast and electron microscope images, and stiffness were also investigated.

Results

The objective of this current study was to evaluate the effects of ROCK-is toward adipogenesis and ECM expression in 3T3-L1 cells. In our previous studies, we found that the effects of PGF2α agonists and EP2 agonists on adipogenesis as well as the expression of ECM in 3T3-L1 cells were significantly different between their 2D and 3D cultures22,24, and the findings suggested that 3D cultures may become a reliable ex vivo model for use in this research field. However, our 3D drop-culture method has not yet fully characterized so far, especially in terms of the physical properties, sizes and stiffness of organoids during the period of their culture. Therefore, the effects of ROCK-is, Ripasudil (Rip) and Y27632 on adipogenesis and ECM expression on 2D cultured 3T3-L1 cells were initially examined and these effects were then investigated using 3D 3T3-L1 organoid cultures, in which their physical properties during the course of the culture were also characterized, as described below.

Effects of the ROCK-i of Ripasudil (Rip) or Y27632 on adipogenesis, and mRNA expressions of major ECMs including collagen (Col) 1, Col 4, Col 6 and fibronectin (Fn) of the 2D cultured 3T3-L1 cells

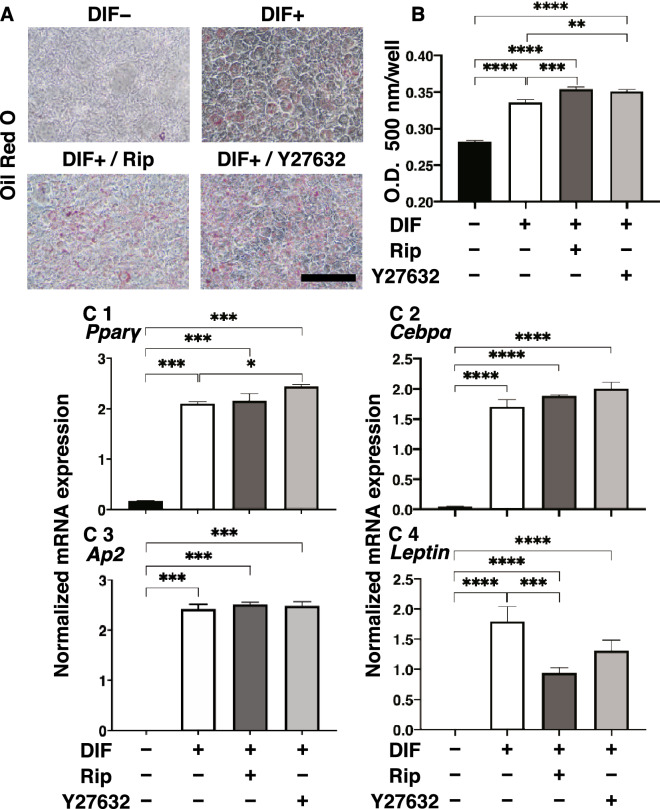

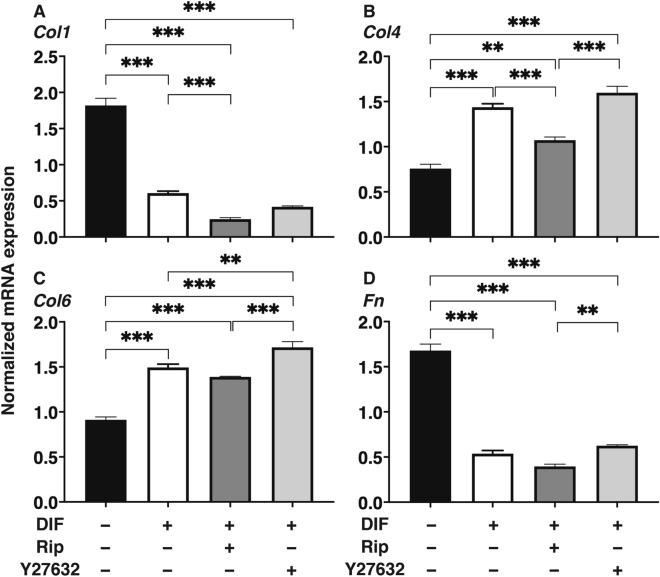

The effects of Rip or Y27632 toward adipogenesis and ECM expression in 2D cultured 3T3-L1 cells were evaluated by lipid staining and quantitative PCR of adipogenesis related genes including Pparγ, Cebpa, Ap2 and Leptin and major ECMs components, Col1, Col4, Col6 and Fn. As shown in Fig. 1, lipid staining by Oil Red O, and the mRNA expression of Pparγ, Cebpa, Ap2 and Leptin of the 2D cultured 3T3-L1 cells were significantly increased upon adipogenesis (DIF+). In the presence of 10 µM Rip or Y27632, lipid staining and mRNA expressions of transcriptional regulatory genes, Pparγ and Cebpa, were further enhanced, while the mRNA expression of the lipid secretory factors, Leptin, was significantly decreased, that of the lipid secretory factor, Ap2 was not altered. In terms of the mRNA expression of major ECMs components of the 2D cultured 3T3-L1 cells, significant down-regulation of Col1 and Fn (panel A and D) and up-regulation of Col4 and Col6 (panel B and C) were observed upon DIF+ (Fig. 2). mRNA expressions of the DIF+ induced up-regulated genes (Col4 and Col6) and those of down-regulated genes (Col1 and Fn) were decreased in the presence of 10 µM Rip. While in contrast, in the presence of 10 µM Y27632, both DIF+ induced up-regulated or down-regulated genes expression except Col1 were increased (Fig. 2). These findings indicated that ROCK-is, Rip and Y27632 have a significant effect on adipogenesis and ECM expression in 2D cultured 3T3-L1 cells, and these effects were similar regarding adipogenesis, but different with respect to ECM expression between the ROCK-is. Since, as stated as above, adipogenesis and ECM expression in 3T3-L1 cells are different depending on their culture status, i.e., for 2D and 3D, and in 3D organoid cultures. We therefore investigated additional features, including the influence of ROCK-was on the physical properties, size and stiffness using a 3D organoid culture system.

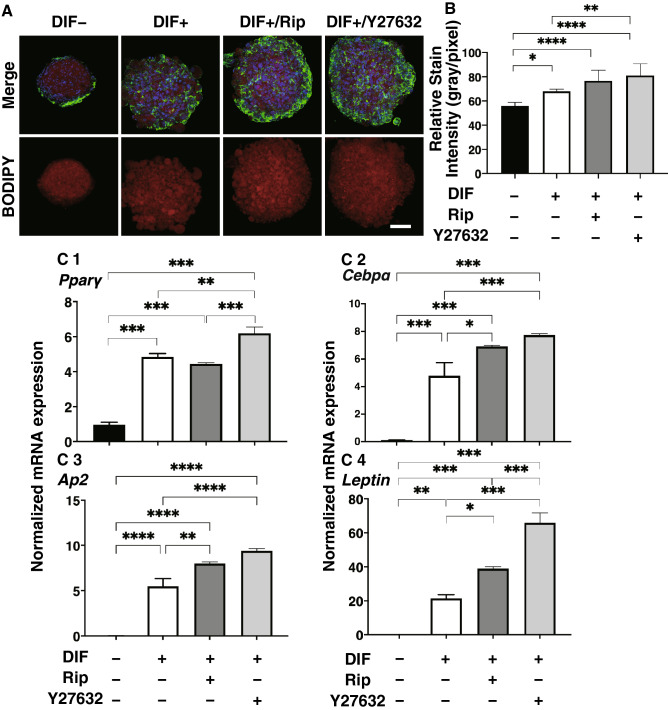

Figure 1.

Effects of ROCK-i on adipogenesis of 2D cultured 3T3-L1 cells. 2D cultures of 3T3-L1 cells were performed under several conditions; preadipocytes of 3T3-L1 cells (DIF−) and their adipogenic differentiation (DIF+) with or without 10 µM Ripasudil (Rip) or Y27632. These were stained by Oil Red O (A, scale bar: 100 μm) and their staining intensities were plotted (B). The mRNA expressions of adipogenesis related genes including Pparγ, Cebpa and Leptin under the above conditions were plotted in (C) 1–3. All experiments were performed in triplicate using fresh preparations, each consisted of 5 samples. Data are presented as arithmetic means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, ****P < 0.001, and other pairs were not statistically significant (ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

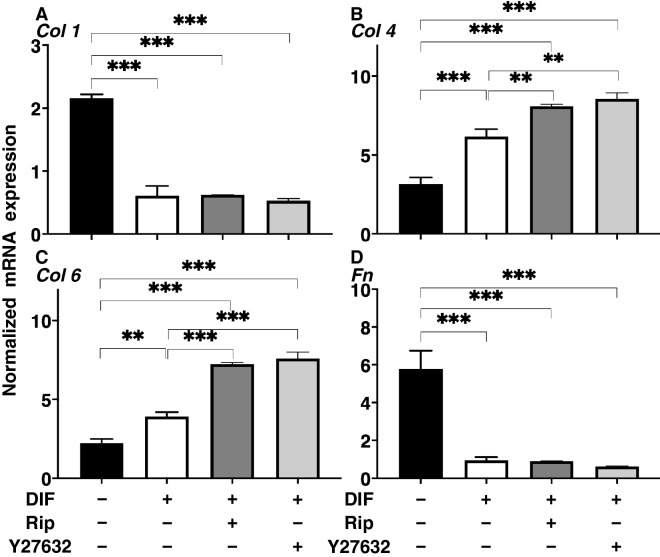

Figure 2.

Effects of ROCK-i on ECM expression of 2D cultured 3T3-L1 cells. The 2D cultured 3T3-L1 preadipocytes (DIF−) and their adipogenic differentiation (DIF+) without or with 10 µM Ripasudil (Rip) or Y27632 were subjected to qPCR analysis to estimate mRNA expression of ECMs (Col1: collagen 1, Col4: collagen 4, Col6: collagen 6, Fn: fibronectin). All experiments were performed in triplicate using fresh preparations, each consisted of 5 samples. Data are presented as the arithmetic means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, and other pairs were not statistically significant (ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

Characterization of physical properties including size and stiffness, and adipogenesis of the 3D cultured 3T3-L1 cells

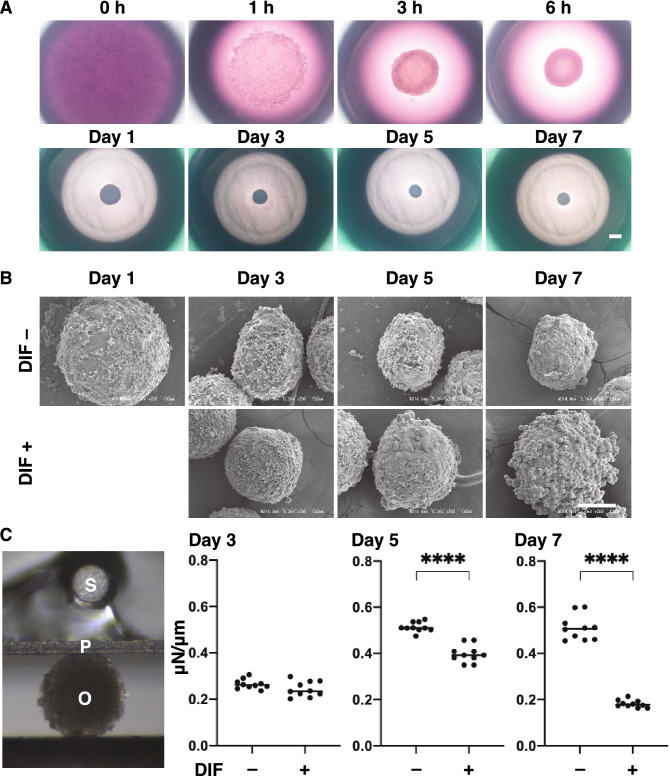

In advance of the next study using 3D 3T3-L1 organoids, changes in their physical properties, sizes and stiffness were evaluated during the course of the 3D culture. Phase contrast microscopy (PC) demonstrated that the 3T3-L1 preadipocytes (DIF–, approximately 20,000 cells within a 28 μl portion of the 3D organoid culture medium) started to coalesce at 1 h after the seeding, and formed premature organoids by 6 h. Thereafter, the 3D organoid became more apparent and a smaller round shaped mature 3D organoid during Day 1 through Day 7 (Fig. 3A). Electron microscopy (EM) revealed that the 3D organoid adopted a more distinct shape that was clearly surrounded with ECM deposits as their maturation proceeded, and upon DIF+ , the oil droplets became readily apparent (Fig. 3B). These PC and EM images indicated that the hardness of the 3D organoid appeared to increase as to their maturation proceeded, and adipogenesis induced an abundance of oil droplets that may decrease the organoid stiffness. These speculations were entirely confirmed by an analysis of the physical stiffness of the organoids using a micro-squeezer (Fig. 3C). These results indicated that the physical properties, size and stiffness of the 3D 3T3-L1 organoid became evident as above during their 7 day-culture.

Figure 3.

Characterization of the maturation process of the 3T3-L1 3D organoid with (DIF+) or without adipogenesis (DIF−). Representative phase contrast microscopy (PC) images at several time points (0, 1, 3, or 6 h, or Day1, 3, 5 or 7) of 3T3-L1 3D organoids without adipogenesis (DIF−) are shown in (A) (Scale bar: 100 µm). Electron microscope (EM) images at several time points (Day1, 3, 5 or 7) of the 3T3-L1 organoids without (DIF−) or with adipogenesis (DIF+) (B, Scale bar: 100 µm). Since adipogenic differentiation was induced from Day 1, the EM image of DIF+ at Day 1 is omitted. A single 3D organoid was compressed by a micro-squeezer, and the compression process was continuously monitored by a microscopic camera (C left, S: sensor, P: plate, O: organoid). As the physical stiffness at several time points (Day 3, 5 or 7) of 3D organoids without (DIF−) or with adipogenesis (DIF+), the force (μN) required to induce deformation until their half diameter (μm) was reached were measured, and force/displacement (μN/μm) was potted (C right). ****P < 0.001, and other pairs were not statistically significant (ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

Effects of the ROCK-i of Ripasudil (Rip) or Y27632 on structures and adipogenesis of the 3D cultured 3T3-L1 cells

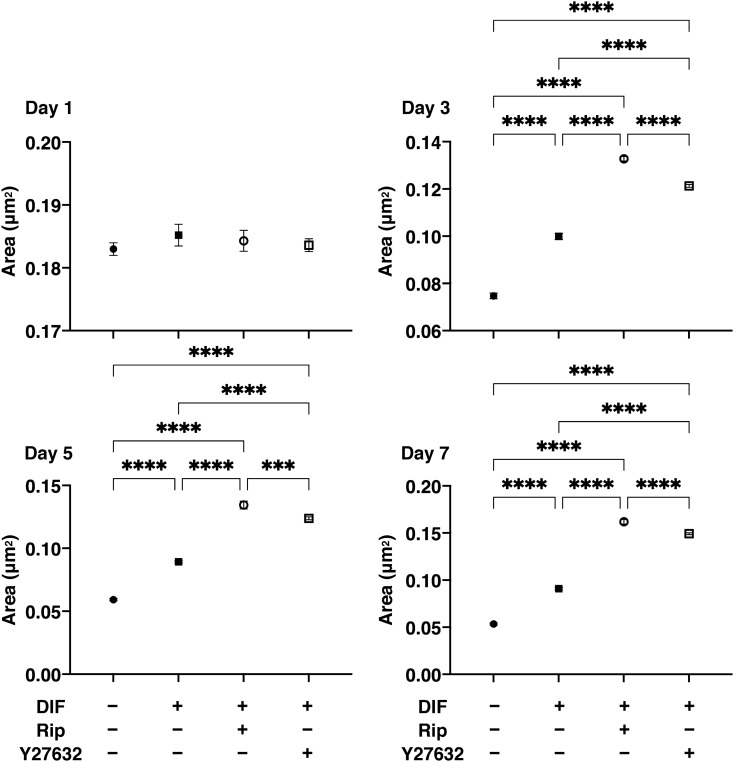

Effects of Rip or Y27632 on the structural features of the 3D 3T3-L1 organoids were investigated by measuring their size, and the level of adipogenesis was evaluated by lipid staining and quantitative PCR of adipogenesis related genes including Pparγ, Cebpa, Ap2 and Leptin. As shown in Fig. 4, consistent with our previous study, uniform round-shape spheroidal organoids of the 3T3-L1 cells were formed and those grew into smaller and matured forms during the 7-day culture. Their mean area sizes were significantly larger upon DIF+ , and such effects by DIF+ were enhanced greatly in the presence of 10 µM Rip or Y27632. In association with the changes in the sizes of areas of the organoids, lipid staining by BODIPY and the mRNA expression of adipogenesis related genes, including Pparγ, Cebpa, Ap2 and Leptin of the 3T3-L1 organoids, were also significantly increased upon DIF+ (Fig. 5). In the presence of 10 µM Rip or Y27632, the expression of the transcriptional regulatory gene, Cebpa and that for the secretory factors, Ap2 and Leptin were further enhanced (Fig. 5). These findings indicated that ROCK-is induced the formation of larger 3D 3T3-L1 organoids and an enhancement in adipogenesis. To elucidate the underlying mechanisms responsible for causing these RCOK-is’ effects, the mRNA expression of ECM and the stiffness of the 3D 3T3-L1 organoids were evaluated.

Figure 4.

Effects of ROCK-i on area sizes of the 3T3-L1 3D organoids during adipogenesis. The mean area sizes (μm2) of the 3D organoids of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes (DIF−, closed circles) and their adipogenic differentiation (DIF+ , closed squares) without or with 10 µM Ripasudil (Rip, open circles) or Y27632 (open squares) were measured. Fluctuations of those during 7-day culture were plotted (left panel) and those at Day 7 were compared among experimental groups (right panel). All experiments were performed in triplicate using fresh preparations, each consisting of 16 organoids. Data are presented as arithmetic means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). ****P < 0.001, and other pairs were not statistically significant (ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

Figure 5.

Effects of ROCK-i on adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 3D organoids. 3T3-L1 3D organoids from Day 7 was prepared under several conditions; preadipocytes of the 3T3-L1 cells (DIF−) and their adipogenic differentiation (DIF+) without or with 10 µM Ripasudil (Rip) or Y27632. These samples were immunostained with DAPI (blue), phalloidin (green) and BODIPY (red) (A, scale bar: 100 μm) and their staining intensities were plotted (B). The mRNA expressions of adipogenesis related genes including Pparγ, Cebpa and Leptin under above conditions were plotted in (C) 1–3. All experiments were performed in duplicate using fresh preparations, each consisting of 16 organoids. Data are presented as arithmetic means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, ****P < 0.001, and other pairs were not statistically significant (ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

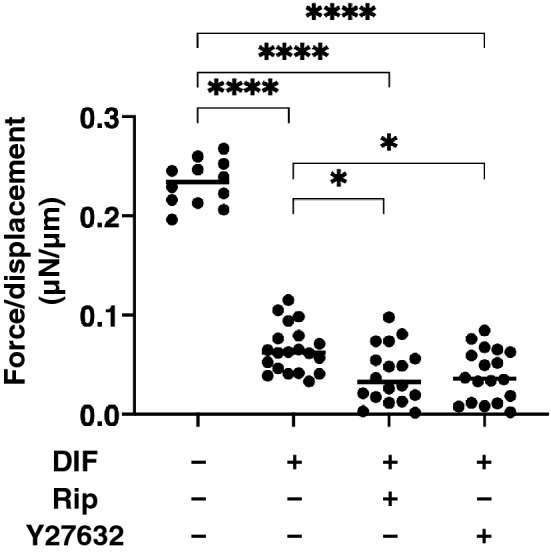

Effects of the ROCK-i of Ripasudil (Rip) or Y27632 on mRNA expressions of major ECMs including collagen (Col) 1, Col 4, Col 6 and fibronectin (Fn) and physical stiffness of the 3D cultured 3T3-L1 cells

The effects of Rip or Y27632 on ECM expression, and the physical stiffness of the 3D 3T3-L1 organoids were evaluated by quantitative PCR of the major ECM components, Col1, Col4, Col6 and Fn, and a micro-squeezer analysis, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6, a significant down-regulation of Col1 and Fn (panel A and D), and up-regulation of Col4 and Col6 (Panel B and C) were observed upon DIF+ as similar to the results from the 2D culture experiments for the mRNA expressions of ECMs (Fig. 2). While in contrast, the ROCK-i induced effects in the 3D 3T3-L1 organoid were different from those for the 2D cultured 3T3-L1 cells, as shown above. That is, mRNA expressions of the DIF+ induced up-regulated genes (Col4 and Col6) were increased and those of down-regulated genes (Col1 and Fn) were not affected in the presence of 10 µM Rip or 10 µM Y27632. Such discrepancy of the effects of the ROCK-is on the ECM expressions between 2D (Fig. 2) and 3D (Fig. 6) cell cultures, which was also recognized in our precedent study may presumably be ascribed to the spatial changes of their ECM expressions in the 3D but not 2D culture22. In fact, the ROCK-is induced up-regulated genes, Col4 and Col6, are basement ECM protein, and thus those may be related to the 3D organoid structure. Taken together, these findings indicate that ROCK-is induced a significant enlargement of the 3D 3T3-L1 organoids with a more abundant lipid content and network derived from collagens (Col4 and Col6), in which the former and the latter appear to be related to physical stiffness and stability, respectively. This rationale was confirmed by a physical stiffness analysis using a micro-squeezer. As shown in Fig. 7, the 3D 3T3-L1 organoid became less stiffness upon DIF+ as above, and these effects were further enhanced in the presence of ROCK-is.

Figure 6.

mRNA expression of ECMs in 3T3-L1 3D organoids under several conditions. At Day 7, the 3T3-L1 3D organoids of preadipocytes (DIF−) and their adipogenic differentiation (DIF+) without or with 10 µM Ripasudil (Rip) or Y27632 were subjected to a qPCR analysis to estimate the mRNA expression of ECMs (Col1: collagen 1, Col4: collagen 4, Col6: collagen 6, Fn: fibronectin). All experiments were performed in duplicate using fresh preparations, each of which consisted of 16 organoids. Data are presented as arithmetic means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, and other pairs were not statistically significant (ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

Figure 7.

Effects of ROCK-i on physical stiffness of the 3T3-L1 3D organoids. At Day 7, the 3T3-L1 3D organoids of preadipocytes (DIF−) and their adipogenic differentiation (DIF+) without or with 10 µM Ripasudil (Rip) or Y27632 were subjected to a physical solidity analysis by a micro-squeezer. The force required to induce deformation until half diameter was reached (μN/μm force/displacement) were measured and potted. All experiments were performed using fresh prepared 12–20 organoids. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.001, and other pairs were not statistically significant (ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

Discussion

A 3D organoid culture was recently been used to stimulate a variety of human pathological conditions25. For this purpose, a conventional 2D organoid culture technique conjugated with synthetic scaffolds such as collagen hydrogels26, or a liquid-based droplet spheroid culture were employed27. Based upon the latter methodology, our group recently developed 3D cultures using a 318-well drop culture plate and successfully obtained 3D organoids from several cells22,23,28. In the present study, we characterized the formation and maturation of 3D organoids of the 3T3-L1 cells during the 7-day culture (Fig. 3). Phase contrast microscope (PC) images demonstrated that the 3T3-L1 cells that were dispersed within a 28 μl 3D organoid culture medium formed immature 3D organoids within 6 h after the seeding, and then developed into matured organoids. As examination of the ultrastructure by electron microscopy (EM) revealed that the ECM surrounding the 3D organoid formed a network during Day 5 and oil droplets then became apparent at Day 7. Consistent with this ECM network formation, a micro-squeezer analysis indicated that the 3D organoid stiffness increased and reached a plateau by Day 5. These observations that both an ECM network and adipogenesis maturation reached completion by Day 7 are the rationale for this study using the 3D organoid culture method. These findings also confirm the validity of our recent studies using this 3D organoid from human orbital fibroblast (HOF) cells23,28 and 3T3-L1 cells22.

Several lines of evidences also indicate that ROCKs are negative regulators of adipocyte differentiation29. In terms of 3T3-L1 cells, it was reported that ROCK 2, but not ROCK 1, is responsible for the suppression of the adipogenesis, and in turn, their inhibitors, Y-27632 and fasudil have been identified to promote adipocyte differentiation29. In the current study, another pan ROCK inhibitor, Rip also enhanced adipogenesis of the 2D and 3D organoids of the 3T3-L1 cells. Again, such a ROCK-i induced enhancement of lipid staining intensities was clearly evident in the 3D organoid cultures (approximately 10–15% increase) compared to the 2D culture (approximately a 4–5% increase) as shown in Figs. 1 and 5. As a possible reason for this difference between the 2D and 3D culture, we speculate that 3D cultures have considerably more space available for adipogenesis of the 3T3-L1 cells, as compared to the 2D culture. In terms of the mRNA expression of the adipogenesis related genes, Pparγ, Cebpa, and Leptin, were increased upon adipogenesis in both 2D and 3D cultures. However, some differences were observed in terms of the effects of ROCK-i on the expression of these genes between 2D (enhancement of Pparγ, Cebpa, and suppression of Leptin) and 3D culture (enhancement of Cebpa and Leptin, and suppression of Pparγ) (Figs. 1 and 5). There were also some differences between Rip and Y27632 in terms of their efficacies toward the of these genes (Figs. 1 and 5). In addition, those different effects were also varied between adipogenesis regulatory genes, Pparγ and Cebpa, and secretory hormone, Leptin. This may be attributed to differences in their preference for ROCK 1 or ROCK 2 inhibitory activities (Rip; ROCK 1 < ROCK 2, Y-27632; ROCK 1 > ROCK 2)30,31, in addition, direct effects toward adipogenesis as well as indirect effects by modulating 3D organoid architectures.

There are many reports concerning the expression of COL1, 4, and 6, and FN in adipocytes or adipose tissues and it has been reported that they are modified during adipogenesis32–34. It has been reported that a main type of adipose ECM is the main fibril-forming COL1 and microfibrillar COL6. Collagens (COLs) are triple helical proteins that are present in the ECM and at the interface between cell and ECM35. There are various types of COLs and COL-related proteins36. Among the COLs, the fibril-forming COL subfamily includes COLs1, 2, 3, 10 and 11, and its structure includes an uninterrupted triple helical domain of approximately 300 nm35. COL1 is the most abundant protein and comprises the bulk of COL fibrils, which serve to impart stiffness to tissues and organs37. COL4 and 6 belong to network-forming COLs which are involved in the regulation of fibril assemblies and organization as well as integrating cells and matrix structures and/or the integration of different matrix structures such as basement membranes38. COL4 networks form the backbone of the basement membrane, and also interacts with basement membrane proteoglycans and glycoproteins that determine its function38,39. COL6 binds a large number of extracellular molecules including: COLs1, 2, 9 and 16, microfibril-associated glycoprotein (MAGP-1), FN, integrins and others40,41. Based upon these findings, COL6 has the capacity to organize the 3D tissue architecture, which may influence cell migration, differentiation and apoptosis/proliferation to maintain of tissue homeostasis42. FN has a weak molecular conformation that can be changed by the binding of allosteric partners or strain resulting from cell contractile forces43. The expression of ECM changes characteristically during in vivo and in in vitro adipogenesis44. Previous studies using a 2D or 3D cultures of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes revealed the in vitro remodeling from COL1- and FN-rich ECM in preadipocyte cells into further basal membrane type-rich ECMs, such as COL4 and 6, in adipocyte cells22,32–34. In the current study, we again confirmed the down regulation of COL1 and FN, and the upregulation of COL4 and COL6 expression upon adipogenesis in both 2D and 3D cultures of the 3T3-L1 cells. In terms of the effects of ROCK-i toward these ECMs expressions, ROCK-i enhanced the adipogenesis-induced upregulation of COL4 and COL6, which was more evident in the 3D organoids than in 2D cultured 3T3-L1 cells, but had no effect on the expression of COL1 and FN. Since COL4 and COL6 are known to belong to network-forming COLs as above, such ROCK-i induced effects toward COL4 and COL6 may facilitate the enlargement of the 3D organoids of the 3T3-L1 cells. Similarly, it has been recognized that the inhibition of ROCK reduces the extent of mechanical tension and stiffness in cells, and decreases ECM synthesis and rigidity in various cell types including the trabecular meshwork45.

The molecular mechanisms causing the ROCK-i induced enlarged and less stiff 3D 3T3-L1 organoid remained to be elucidated. As shown in Fig. 5, in the presence of ROCK-i, no cell death and cell proliferation occurred since significant increase or decrease were not detected in the series of sections of the 3D organoid stained by DAPI cell nuclear staining.

Our analysis of the physical stiffness of the single 3D organoid most likely reflects amounts of lipid contents as well as structure foaming proteins including ECMs. Since our result indicated ROCK-i significantly enhanced adipogenesis and basement membrane related ECMs; Col4 and Col6, but not other major ECMs; Col 1 and Fn. Therefore, we speculated that ROCK-i mainly induced increase of lipid contents and simultaneously, basement membrane related ECMs also increase to foam an enlarged 3D organoid to contain such enriched lipid. However, in order to prove this speculation, additional study using inhibitions at different signaling by several specific inhibitors or Si-RNA will be required as our new project.

Recently, a great attention has been paid concerning the periocular side effects of anti-glaucoma medications on orbital adipocytes46,47. Since Rip is used as an anti-glaucoma medication, our present data using 3T3-L1 cells suggested that Rip may also affect toward the orbital adipocyte. However, it was revealed that the physiological properties of human orbital fatty tissues are different from those of 3T3-L1 cells. Therefore, effects of ROCK-is to human orbital fibroblasts (HOFs) rather than 3T3-L1 cells will be investigated as our next project.

Materials and methods

Adipocyte culture and differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells

To obtain 3T3-L1 organoids, 3T3-L1 preadipocytes (#EC86052701-G0, KAK) grown in two-dimension (2D) cultures until reaching confluence at 37 °C in a 2D growth medium (HG-DMEM containing 8 mg/L d-biotin, 4 mg/L calcium pantothenate, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin (b.p. HG-DMEM), and 10% CS) were then subjected to our recently described hanging droplet spheroid three-dimension (3D) culture system29. Briefly, approximately 90% confluence of the cells cultured in 100 mm or 150 mm dishes were washed with a phosphate buffered saline (PBS), detached using 0.25% Trypsin/EDTA and resuspended in an organoid medium (2D growth medium supplemented with 0.25% w/v Methocel A4M). Approximately 20,000 cells in the 28 μL organoid medium were placed into each well of the drop culture plate (defined as 3D/Day 0). On every following day, 14 μL of the organoid medium was substituted with a fresh 14 μL organoid medium in each well.

Adipogenic differentiation of 2D or 3D cultured 3T3-L1 cells with or without ROCK inhibitors (ROCK-i)

The induction of adipogenic differentiation was processed in the 2D growth medium (2D culture) of the organoid medium (3D culture) supplemented with 250 nM dexamethasone, 10 nM T3, 10 μM troglitazone, and 1 μg/ml insulin for two days, and thereafter in the 2D or 3D culture medium supplemented with 10 μM troglitazone and 1 μg/ml insulin. To study the efficacy of ROCK-i, 10 µM Ripasudil (Rip, a generous gift from the Kowa Company Ltd., Nagoya, Japan) or Y27632 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) were added during the adipogenic differentiation.

Histocytology

Oil Red O lipid staining of the 2D cultured 3T3-L1 cells and BODIPY lipid staining of the 3D 3T3-L1 organoids were performed as described previously24. To quantify their staining levels, measurements of optical density of the extracted Oil Red O dye, and the fluorescence intensity of the BODIPY-stained lipid droplets were used, respectively24.

Real-time PCR

The RNA extracted from 16 organoids of each groups were processed to reverse transcription, and each respective gene expression was quantified by real-time PCR as described previously24. In terms of assay specificity for qPCR, to guarantee a high quality of the assay, predesigned primers shown in the supplemental Table 1 from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. Iowa USA, were used.

Micro-indentation force measurement

The micro-indentation force of the organoids was measured using micro-squeezer (CellScale, Waterloo, ON, Canada) as described previously29. Briefly, a single organoid placed on a 3-mm × 3-mm plate was compressed to achieve a 50% deformation during 20 s under monitoring by an equipped micro-camera. The required strain (μN) was measured, and force/displacement (μN/μm) was calculated.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Graph Pad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). To analyze the difference between groups, a grouped analysis with two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparison test was performed. Data are presented as arithmetic means ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Supplementary information

Author contributions

Y.I. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the paper. H.O. analyzed the data and provided conceptual advice. F.H. designed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yosuke Ida and Fumihito Hikage.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-84955-7.

References

- 1.Tang L, et al. RhoA/ROCK signaling regulates smooth muscle phenotypic modulation and vascular remodeling via the JNK pathway and vimentin cytoskeleton. Pharmacol. Res. 2018;133:201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xue Y, et al. Methamphetamine reduces expressions of tight junction proteins, rearranges F-actin cytoskeleton and increases the blood brain barrier permeability via the RhoA/ROCK-dependent pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019;509:395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.12.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zanin-Zhorov A, Flynn R, Waksal SD, Blazar BR. Isoform-specific targeting of ROCK proteins in immune cells. Small GTPases. 2016;7:173–177. doi: 10.1080/21541248.2016.1181698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mack NA, Georgiou M. The interdependence of the Rho GTPases and apicobasal cell polarity. Small GTPases. 2014;5:10. doi: 10.4161/21541248.2014.973768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Julian L, Olson MF. Rho-associated coiled-coil containing kinases (ROCK): Structure, regulation, and functions. Small GTPases. 2014;5:e29846. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.29846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun KH, et al. Regulation of glucose transport by ROCK1 differs from that of ROCK2 and is controlled by actin polymerization. Endocrinology. 2012;153:1649–1662. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Street CA, Bryan BA. Rho kinase proteins–pleiotropic modulators of cell survival and apoptosis. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:3645–3657. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakagawa O, et al. ROCK-I and ROCK-II, two isoforms of Rho-associated coiled-coil forming protein serine/threonine kinase in mice. FEBS Lett. 1996;392:189–193. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00811-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukiage C, Mizutani K, Kawamoto Y, Azuma M, Shearer TR. Involvement of phosphorylation of myosin phosphatase by ROCK in trabecular meshwork and ciliary muscle contraction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;288:296–300. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokota T, et al. Involvement of the rho/rho kinase signaling pathway in platelet-derived growth factor BB-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression in diabetic rat retina. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2007;51:424–430. doi: 10.1007/s10384-007-0471-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arita R, et al. Rho kinase inhibition by fasudil ameliorates diabetes-induced microvascular damage. Diabetes. 2009;58:215–226. doi: 10.2337/db08-0762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollanders K, et al. The effect of AMA0428, a novel and potent ROCK inhibitor, in a model of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015;56:1335–1348. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okumura N, et al. The new therapeutic concept of using a rho kinase inhibitor for the treatment of corneal endothelial dysfunction. Cornea. 2011;30:S54–S59. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182281ee1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertrand J, Winton MJ, Rodriguez-Hernandez N, Campenot RB, McKerracher L. Application of Rho antagonist to neuronal cell bodies promotes neurite growth in compartmented cultures and regeneration of retinal ganglion cell axons in the optic nerve of adult rats. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:1113–1121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3931-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan H-B, Zhong Y-S, Cheng Y, Shen X. Rho/ROCK pathway and neural regeneration: A potential therapeutic target for central nervous system and optic nerve damage. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2011;4:652–657. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2011.06.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kameda T, et al. The effect of rho-associated protein kinase inhibitor on monkey Schlemm's canal endothelial cells. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012;53:3092–3103. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van de Velde S, et al. AMA0076, a novel, locally acting rho kinase inhibitor, potently lowers intraocular pressure in New Zealand white rabbits with minimal hyperemia. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014;55:1006–1016. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue T, Tanihara H. Rho-associated kinase inhibitors: A novel glaucoma therapy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2013;37:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanihara H, et al. Intra-ocular pressure-lowering effects of a Rho kinase inhibitor, ripasudil (K-115), over 24 hours in primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension: A randomized, open-label, crossover study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93:e254–e260. doi: 10.1111/aos.12599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peplinski LS, Albiani Smith K. Deepening of lid sulcus from topical bimatoprost therapy. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2004;81:574–577. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000141791.16683.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serrero G, Lepak NM. Prostaglandin F2alpha receptor (FP receptor) agonists are potent adipose differentiation inhibitors for primary culture of adipocyte precursors in defined medium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;233:200–202. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ida Y, Hikage F, Itoh K, Ida H, Ohguro H. Prostaglandin F2α agonist-induced suppression of 3T3-L1 cell adipogenesis affects spatial formation of extra-cellular matrix. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:7958. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64674-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itoh K, Hikage F, Ida Y, Ohguro H. Prostaglandin F2alpha agonists negatively modulate the size of 3D organoids from primary human orbital fibroblasts. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020;61:13. doi: 10.1167/iovs.61.6.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ida Y, Hikage F, Umetsu A, Ida H, Ohguro H. Omidenepag, a non-prostanoid EP2 receptor agonist, induces enlargement of the 3D organoid of 3T3-L1 cells. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:16018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72538-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thoma CR, Zimmermann M, Agarkova I, Kelm JM, Krek W. 3D cell culture systems modeling tumor growth determinants in cancer target discovery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014;69–70:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chun TH, et al. A pericellular collagenase directs the 3-dimensional development of white adipose tissue. Cell. 2006;125:577–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tung YC, et al. High-throughput 3D spheroid culture and drug testing using a 384 hanging drop array. Analyst. 2011;136:473–478. doi: 10.1039/c0an00609b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hikage F, Atkins S, Kahana A, Smith TJ, Chun TH. HIF2A-LOX pathway promotes fibrotic tissue remodeling in thyroid-associated orbitopathy. Endocrinology. 2019;160:20–35. doi: 10.1210/en.2018-00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diep DTV, et al. Anti-adipogenic effects of KD025 (SLx-2119), a ROCK2-specific inhibitor, in 3T3-L1 cells. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:2477. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20821-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang J, Ruan F, Zheng Z. Ripasudil attenuates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated apoptosis and inflammation in pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells via ROCK2/eNOS signaling. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018;24:3212–3219. doi: 10.12659/MSM.910184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang H, et al. CXCL16/ROCK1 signaling pathway exacerbates acute kidney injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;98:347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gregoire FM, Smas CM, Sul HS. Understanding adipocyte differentiation. Physiol. Rev. 1998;78:783–809. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.3.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Divoux A, Clement K. Architecture and the extracellular matrix: The still unappreciated components of the adipose tissue. Obes. Rev. 2011;12:e494–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiner FR, Shah A, Smith PJ, Rubin CS, Zern MA. Regulation of collagen gene expression in 3T3-L1 cells. Effects of adipocyte differentiation and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Biochemistry. 1989;28:4094–4099. doi: 10.1021/bi00435a070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gordon MK, Hahn RA. Collagens. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:247–257. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0844-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kadler KE, Hill A, Canty-Laird EG. Collagen fibrillogenesis: Fibronectin, integrins, and minor collagens as organizers and nucleators. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2008;20:495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith SM, Birk DE. Focus on molecules: Collagens V and XI. Exp. Eye Res. 2012;98:105–106. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yurchenco PD. Basement membranes: Cell scaffoldings and signaling platforms. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khoshnoodi J, Pedchenko V, Hudson BG. Mammalian collagen IV. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2008;71:357–370. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonnemann CG. The collagen VI-related myopathies: Muscle meets its matrix. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2011;7:379–390. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lamande SR, Bateman JF. Collagen VI disorders: Insights on form and function in the extracellular matrix and beyond. Matrix Biol. 2018;71–72:348–367. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gregorio I, Braghetta P, Bonaldo P, Cescon M. Collagen VI in healthy and diseased nervous system. Dis. Model Mech. 2018 doi: 10.1242/dmm.032946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zollinger AJ, Smith ML. Fibronectin, the extracellular glue. Matrix Biol. 2017;60–61:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mori S, Kiuchi S, Ouchi A, Hase T, Murase T. Characteristic expression of extracellular matrix in subcutaneous adipose tissue development and adipogenesis; comparison with visceral adipose tissue. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2014;10:825–833. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.8672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pattabiraman PP, Maddala R, Rao PV. Regulation of plasticity and fibrogenic activity of trabecular meshwork cells by Rho GTPase signaling. J. Cell. Physiol. 2014;229:927–942. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seibold LK, Ammar DA, Kahook MY. Acute effects of glaucoma medications and benzalkonium chloride on pre-adipocyte proliferation and adipocyte cytotoxicity in vitro. Curr. Eye Res. 2013;38:70–74. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2012.733055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taketani Y, et al. Activation of the prostanoid FP receptor inhibits adipogenesis leading to deepening of the upper eyelid sulcus in prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014;55:1269–1276. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.