Abstract

Introduction:

Dry socket is one of the most common postoperative complications following the extraction of permanent teeth, which is characterized by pain and exposed bone. The usual protocol followed for its management is irrigation of the socket and packing of the socket with medicated gel or paste to provide relatively faster pain relief and allow normal wound healing. In this study, we evaluated the outcome of management of dry socket with platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) and intraalveolar alvogyl dressing, in terms of improvement in pain and socket epithelialization after the treatment.

Methodology:

Thirty participants with established dry socket were randomly divided into two groups: Group A and Group B. The participants in Group A were treated with alvogyl and those in Group B were treated with PRF. Clinical parameters were assessed for both groups on the 1st day of the procedure and on the 3rd and 10th-day postoperatively for the reduction in pain and wound healing.

Results:

There was a significant decrease in pain and the number of socket wall exposure in both the groups by the 3rd postoperative day. In both the groups, the pain had completely resolved and socket fully epithelialized by the 10th postoperative day.

Discussion:

The use of PRF in the present study yielded promising results in terms of both pain reduction and improved wound healing which was comparable to the conventional alvogyl dressing. It may be concluded that PRF is an effective modality for the management of dry socket.

Keywords: Alvogyl, dry socket, platelet-rich fibrin

INTRODUCTION

The term dry socket has been used in the literature since 1896 after it was first described by Crawford.[1] Various other terms have been used referring to this condition, Birn labeled the complication as “fibrinolytic alveolitis.”[2,3]

Dry socket was first described as a complication of the disintegration of the intraalveolar blood clot with an onset of 2–4 days after an extraction. According to Fazakerlev and Field,[4] the alveolar socket empties, and there is denudation of the osseous surrounding after which there appears yellow-gray necrotic tissue layer with surrounding mucosal erythema. Clinically, it is characterized by intense radiating pain and putrid odor.

Studies have reported that the onset of alveolar osteitis occurs 1–3 days after extraction[5,6] presenting with exposed bone and moderate-to-severe pain, and its duration varies to some degree, depending on the severity, but it usually ranges from 5 to 10 days. The usual protocol followed for the management of dry socket is irrigation of the socket to flush out any food particles or debris that may lead to further infection and packing of the socket with medicated gel or paste to provide relatively faster pain relief and allow normal wound healing.

Systemic antibiotics, topical antibiotics, chlorhexidine, parahydroxybenzoic acid, tranexamic acid, polylactic acid, steroids, eugenol-containing dressings, etc., have been proposed to assist in the prevention of dry socket. However, this area remains controversial as no single method has gained universal acceptance.[7] Most agree that the primary aim of dry socket management, as indicated by Fazakerlev and Field,[4] is pain control until the commencement of normal healing.

The use of intraalveolar dressing materials is widely suggested in the literature, but different medicaments and carrier systems that are available commercially have little scientific evidence to guide a selection process for their use.[7] The most commonly used intraalveolar dressing material for dry socket is alvogyl (Septodent, Inc, Wilmington, DE), which rapidly provides pain relief and soothing effect throughout the healing process. The active ingredients of alvogyl include eugenol (effective analgesic action), butamben (effective anesthetic action), and iodoform (antimicrobial action).

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the outcome of management of dry socket with platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) and widely used intraalveolar alvogyl dressing, to determine the improvement in pain and socket epithelialization after treatment.

METHODOLOGY

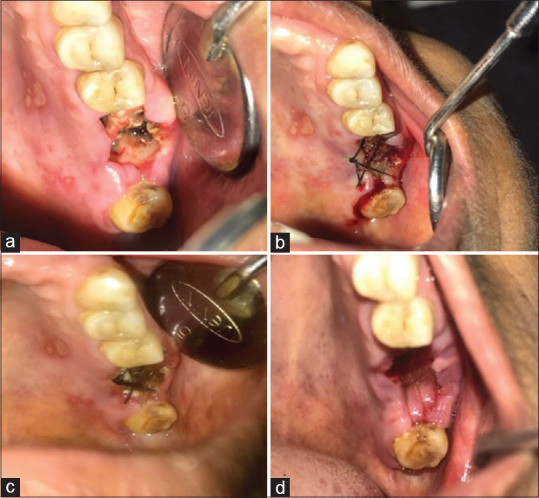

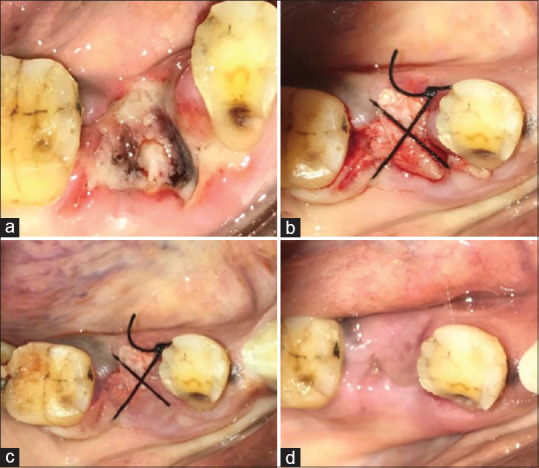

Patients reporting with postextraction pain, who fit the criteria for dry socket, were selected for this study after an informed consent. Patients who did not consent for the study and patients below 14 and above 60 years of age were excluded from the study. A detailed history consisting of chief complaint, relevant past medical history, drug history/allergy, and personal history were recorded for every patient. Patients were examined both symptomatically and clinically. A total of thirty patients were included in the study based on the prevalence of dry socket (0.5%–5.6%)[8] and were randomly divided into two Groups (Group A and Group B), with 15 patients in each group using simple randomization. The participants in Group A (control group) were treated for dry socket with gentle irrigation with warm saline. After isolation and debridement, the socket was then packed with alvogyl and sutured using 3.0 Mersilk with a figure of eight to avoid immediate elimination of the dressing from the socket [Figure 1]. The participants in Group B (test group) were treated with PRF in the extraction socket. The standard-operating procedure was followed by irrigating the socket with warm saline. After isolation and debridement, the PRF membrane was placed in the socket and sutured using 3.0 Mersilk with a figure of eight [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Alvogyl group. (a) = Day 1 (at the time of presentation), (b) = Day 1 (after alvogyl and suturing), (c) = Day 3 postoperative, (d) = Day 10 postoperative

Figure 2.

Platelet rich fibrin group. (a) = Day 1 (at the time of presentation), (b) = Day 1 (After platelet rich fibrin and suturing), (c) = Day 3 postoperative, (d) = Day 10 postoperative

Preparation of platelet-rich fibrin

Under aseptic precautions, 10 ml of venous blood was drawn from the antecubital vein of the patients. This blood was centrifuged in two vacutainers (Becton Dickinson) of 5 ml each that were devoid of any anticoagulants. The vacutainers were then centrifuged at a speed of 3000 rpm for 10 min in a table-top centrifuge (Remy C-852) to obtain PRF gel. Three layers were isolated after centrifugation with the first layer of red blood cells at the bottom, the second layer of white blood cells in the middle, and the PRF layer at the top. The topmost PRF gel layer was isolated and squeezed on sterile saline-soaked gauze pieces to obtain the PRF membrane which was then used for the study.

Both groups were prescribed paracetamol 500 mg thrice daily for analgesia postoperatively and oral hygiene instructions were given. Clinical parameters were assessed for both groups on the 1st, 3rd, and 10th day postoperatively for the reduction in pain and wound healing. The pain was measured using a subjective 10-point Visual Analog Scale by the patient in the presence of the operator. The wound healing was assessed by the number of socket walls that were exposed. The results of the above documentations were tabulated in a case pro forma, analyzed, and inferences were made.

RESULTS

Statistical methods applied

Friedman test

Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

DISCUSSION

One of the most commonly encountered complications of exodontia is a dry socket. Studies have reported that the onset of dry socket occurs 1–3 days after tooth extraction.[5,6,9] Duration of the dry socket varies depending on its severity, but usually, it ranges from 5 to 10 days.[9]

The management of dry socket has been a less controversial one[6] than its etiology and prevention. Many authors agree that the primary aim is pain control until the commencement of normal healing as suggested by Fazakerley.[4] In some instances, systemic analgesics or antibiotics may be necessary or indicated.[10] The use of intraalveolar dressing materials is also suggested in the literature,[11,12] although it is generally acknowledged that dressings delay healing of the extraction socket.[13]

Alvogyl has been widely used in the management of dry socket and is frequently mentioned in the literature. It is known to rapidly provide pain relief and soothing effect throughout the healing process. Some authors[7,14] noted that there was delayed healing when the sockets were packed with Alvogyl, but there has been no definite literature evidence against its usage.

PRF is characterized by the slow polymerization during its preparation that generates a fibrin network very similar to the natural one that enhances cell migration and proliferation.[15] PRF is a reservoir of platelets, leukocytes, cytokines, and growth factors. It is reported to allow the slow release of cytokines, transforming growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and epidermal growth factor play a vital role on angiogenesis, tissue healing, and cicatrization.[16,17]

Choukroun et al.[17] in France advocated the use of PRF which is a second-generation platelet concentrate. PRF is a stringently autologous fibrin matrix. Dohan et al.[16] suggested that PRF addition can correct destructive reactions in the natural process of healing of wound tissues suggesting that PRF contributes to the immune regulatory mechanism. Choukroun et al.[17] demonstrated a clinical example in which they used the PRF as a filling material in the extraction socket. They confirmed that neovascularization and epithelial coverage of the extraction socket can be achieved with the use of PRF.

In this study, we found, in terms of pain, a statistically significant difference for pain reduction in both Group A and Group B. Therefore, patients of both groups showed a similar decrease in pain by the 10th postoperative day [Table 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Group A (Alvogyl) NPar tests of Visual Analog Scale scores

| Descriptive statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

| vas_d1 | 15 | 9.6667 | 0.48795 | 9.00 | 10.00 |

| vas_d3 | 15 | 1.1333 | 0.83381 | 0.00 | 2.00 |

| vas_d10 | 15 | 0.0000 | 0.00000 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Friedman test Ranks | |||||

| Mean rank | |||||

| vas_d1 | 3.00 | ||||

| vas_d3 | 1.87 | ||||

| vas_d10 | 1.13 | ||||

| Test statisticsa | |||||

| n | 15 | ||||

| χ2 | 28.429 | ||||

| df | 2 | ||||

| Asymptotic significant | 0.000 | ||||

aFriedman test. SD=Standard deviation

Table 2.

Group B (platelet-rich fibrin) NPar tests of Visual Analog Scale scores

| Descriptive statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

| vas_d1 | 15 | 9.5333 | 0.51640 | 9.00 | 10.00 |

| vas_d3 | 15 | 0.2667 | 0.45774 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| vas_d10 | 15 | 0.0000 | 0.00000 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Friedman test Ranks | |||||

| Mean rank | |||||

| vas_d1 | 3.00 | ||||

| vas_d3 | 1.63 | ||||

| vas_d10 | 1.37 | ||||

| Test statisticsa | |||||

| n | 15 | ||||

| χ2 | 28.204 | ||||

| df | 2 | ||||

| Asymptotic significant | 0.000 | ||||

aFriedman test. SD=Standard deviation

In terms of the degree of epithelialization, a statistically significant reduction was noted in the number of socket walls exposure posttreatment in both Group A and Group B. Both groups showed satisfactory healing by the 10th postoperative day [Table 3 and 4].

Table 3.

Group A (Alvogyl) NPar tests of socket-wall exposure

| Descriptive statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Socket_1 | 15 | 2.8667 | 0.63994 | 2.00 | 4.00 |

| Socket_3 | 15 | 0.6667 | 0.48795 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Socket_10 | 15 | 0.0000 | 0.00000 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Friedman test Ranks | |||||

| Mean rank | |||||

| Socket_1 | 3.00 | ||||

| Socket_3 | 1.83 | ||||

| Socket_10 | 1.17 | ||||

| Test statisticsa | |||||

| n | 15 | ||||

| χ2 | 28.182 | ||||

| df | 2 | ||||

| Asymptotic significant | 0.000 | ||||

aFriedman test. SD=Standard deviation

Table 4.

Group B (platelet-rich fibrin) NPar tests of socket wall exposure

| Descriptive statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

| socket_1 | 15 | 3.4667 | 0.51640 | 3.00 | 4.00 |

| socket_3 | 15 | 0.2000 | 0.41404 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| socket_10 | 15 | 0.0000 | 0.00000 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Friedman test Ranks | |||||

| Mean rank | |||||

| socket_1 | 3.00 | ||||

| socket_3 | 1.60 | ||||

| socket_10 | 1.40 | ||||

| Test Statisticsa | |||||

| n | 15 | ||||

| χ2 | 28.500 | ||||

| df | 2 | ||||

| Asymptotic significant | 0.000 | ||||

aFriedman test

Within the Group A, there was a statistically significant decrease in terms of both parameters, i.e. pain and the number of socket walls exposed, from day 1 to day 3, day 3 to day 10, and day 1 to day 10. This showed that there was a gradual reduction of pain and continued healing process from the 1st day to the 10th postoperative day [Table 5].

Table 5.

Group A (Alvogyl) Wilcoxon signed-rank test

| Ranks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean rank | Sum of ranks | ||

| vas_d3 - vas_d1 | ||||

| Negative ranks | 15a | 8.00 | 120.00 | |

| Positive ranks | 0b | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Ties | 0c | |||

| Total | 15 | |||

| socket_3 - socket_1 | ||||

| Negative ranks | 15d | 8.00 | 120.00 | |

| Positive ranks | 0e | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Ties | 0f | |||

| Total | 15 | |||

| Test statisticsa | ||||

| vas_d3 - vas_d1 | socket_3 - socket_1 | |||

| Z | −3.443b | −3.457b | ||

| Asymptotic significant (two-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

aWilcoxon signed-ranks test, bBased on positive ranks. avas_d3 < vas_ d1, bvas_d3 > vas_d1, cvas_d3=vas_d1, dsocket_3 < socket_1, esocket_3 > socket_1, fsocket_3=socket_1

Within the Group B, there was a statistically significant decrease in terms of pain from day 1 to day 3 and day 1 to day 10. In terms of the number of socket wall exposure, there was a statistically significant decrease from day 1 to day 3 and day 1 to day 10. There was a significant reduction in the number of socket walls exposed in all the patients who were treated with PRF by the 3rd postoperative day [Table 6].

Table 6.

Group B (platelet-rich fibrin) Wilcoxon signed-rank test

| Ranks | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean rank | Sum of ranks | |

| vas_d3 - vas_d1 | |||

| Negative ranks | 15a | 8.00 | 120.00 |

| Positive ranks | 0b | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ties | 0c | ||

| Total | 15 | ||

| socket_3 - socket_1 | |||

| Negative ranks | 15d | 8.00 | 120.00 |

| Positive ranks | 0e | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ties | 0f | ||

| Total | 15 | ||

| Test statisticsa | |||

| vas_d3 - vas_d1 | socket_3 - socket_1 | ||

| Z | −3.464b | −3.578b | |

| Asymptotic significant (two-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.000 | |

avas_d3 < vas_d1, bvas_d3 > vas_d1, cvas_d3=vas_d1, dsocket_3 < socket_1, esocket_3 > socket_1, fsocket_3=socket_1. aWilcoxon signed-rank test, bBased on positive ranks

The findings of the present study are in conjunction with the studies done by Sam Paul et al.,[18] Ravi Bhujbal et al.,[19] Ashish Sharma et al.,[20] Srinivas Chakravarthi,[21] and Ivan Chenchev,[22] all of whom have concluded that PRF can be successfully used in the treatment of dry socket.

CONCLUSIONS

The PRF dressing is a good biological material that causes enhanced-tissue healing and a significant reduction in pain in dry socket. The use of PRF in the present study yielded promising results in terms of both pain reduction and improved wound healing which was comparable to the conventional Alvogyl dressing. It may be concluded that PRF is an effective modality for the management of dry socket.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crawford JY. Dry socket. Dent Cosmos. 1896;38:929. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birn H. Bacterial and fibrinolytic activity in 'dry socket'. Acta Odontolol Scand. 1970;28:773–83. doi: 10.3109/00016357009028246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birn H. Fibrinolytic activity of alveolar bone in “dry socket”. Acta Odontol Scand. 1972;30:23–32. doi: 10.3109/00016357209004589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fazakerley M, Field EA. Dry socket: A painful post-extraction complication (a review) Dent Update. 1991;18:31–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fridrick KL, Olson Raj. Alveolar osteitis following removal of mandibular third molars. Anaesth Prog. 1990;37:32–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nitzan DW. On the genesis of 'dry socket'. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:706–10. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(83)90185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antonia K. Alveolar osteitis: A comprehensive review of concepts and controversies. Int J Dent. 2010;1:10. doi: 10.1155/2010/249073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akinbami BO, Godspower T. Dry socket: incidence, clinical features, and predisposing factors. Int J Dent. 2014;2014:796102. doi: 10.1155/2014/796102. doi:10.1155/2014/796102. Epub 2014 Jun 2. PMID: 24987419; PMCID: PMC4060391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blum IR. Contemporary views on dry socket (alveolar osteitis): A clinical appraisal of standardization, aetiopathogenesis and management: A critical review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;31:309–17. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heasman PA, Jacobs DJ. A clinical investigation into the incidence of dry socket. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;22:115–22. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(84)90023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vezeau PJ. Dental extraction wound management: Medicating postextraction sockets. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:531–7. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(00)90016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swanson AE. A double-blind study on the effectiveness of tetracycline in reducing the incidence of fibrinolytic alveolitis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:165–7. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(89)80110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloomer CR. Alveolar osteitis prevention by immediate placement of medicated packing. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:282–4. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.108919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Summers L, Matz LR. Extraction wound sockets.Histological changes and paste packs – A trial. Br Dent J. 1976;141:377–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4803851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Hamed FS, Tawfik MA, Abdelfadil E. Clinical effects of platelet rich fibrin (PRF) following surgical extraction of lower third molar. Saudi J Dent Res. 2016;5:2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate.Part II: Platelet-related biologic features. Oral Surg Oral Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joseph C, Antoine D, Alain S, Marie-Odile G, Christian S, Steve ID, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate.Part IV: Clinical effects on tissue healing. Oral Sur Oral Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paul S, Choudhury R, Kumari N, Rastogi S, Sharma A, Singh V, et al. Is treatment with platelet-rich fibrin better than zinc oxide eugenol in cases of established dry socket for controlling pain, reducing inflammation, and improving wound healing? J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;45:76. doi: 10.5125/jkaoms.2019.45.2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19.Bhujbal R, Malik NA, Kumar N, Kv S, Parkar MI, Mb J. Comparative evaluation of platelet rich plasma in socket healing and bone regeneration after surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2018;12:153–8. doi: 10.15171/joddd.2018.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rastogi S, Sharma A, Aggarwal N, Choudhury R, Tripathi S. Effectiveness of platelet-rich fibrin in the management of pain and delayed wound healing associated with established alveolar osteitis (dry socket) Eur J Dent. 2017;11:508. doi: 10.4103/ejd.ejd_346_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chakravarthi S. Platelet rich fibrin in the management of established dry socket. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;43:160. doi: 10.5125/jkaoms.2017.43.3.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chenchev I, Ivanova V, Dobreva D, Neychev D. Treatment of dry socket with platelet-rich fibrin. J IMAB. 2017;23:1702–5. [Google Scholar]