Key Points

Question

In patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy, does a ventral surgical approach, compared with a dorsal surgical approach, improve patient-reported physical functioning at 1 year?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 163 patients, mean improvement in the Short Form 36 physical component summary score (range, 0-100) was 5.9 points in the ventral surgery group and 6.2 points in the dorsal surgery group at 1 year, a difference that was not statistically significant.

Meaning

Among patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy undergoing cervical spinal surgery, a ventral approach did not significantly improve patient-reported physical functioning at 1 year compared with outcomes after a dorsal approach.

Abstract

Importance

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy is the most common cause of spinal cord dysfunction worldwide. It remains unknown whether a ventral or dorsal surgical approach provides the best results.

Objective

To determine whether a ventral surgical approach compared with a dorsal surgical approach for treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy improves patient-reported physical functioning at 1 year.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized clinical trial of patients aged 45 to 80 years with multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy enrolled at 15 large North American hospitals from April 1, 2014, to March 30, 2018; final follow-up was April 15, 2020.

Interventions

Patients were randomized to undergo ventral surgery (n = 63) or dorsal surgery (n = 100). Ventral surgery involved anterior cervical disk removal and instrumented fusion. Dorsal surgery involved laminectomy with instrumented fusion or open-door laminoplasty. Type of dorsal surgery (fusion or laminoplasty) was at surgeon’s discretion.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was 1-year change in the Short Form 36 physical component summary (SF-36 PCS) score (range, 0 [worst] to 100 [best]; minimum clinically important difference = 5). Secondary outcomes included 1-year change in modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association scale score, complications, work status, sagittal vertical axis, health resource utilization, and 1- and 2-year changes in the Neck Disability Index and the EuroQol 5 Dimensions score.

Results

Among 163 patients who were randomized (mean age, 62 years; 80 [49%] women), 155 (95%) completed the trial at 1 year (80% at 2 years). All patients had surgery, but 5 patients did not receive their allocated surgery (ventral: n = 1; dorsal: n = 4). One-year SF-36 PCS mean improvement was not significantly different between ventral surgery (5.9 points) and dorsal surgery (6.2 points) (estimated mean difference, 0.3; 95% CI, −2.6 to 3.1; P = .86). Of 7 prespecified secondary outcomes, 6 showed no significant difference. Rates of complications in the ventral and dorsal surgery groups, respectively, were 48% vs 24% (difference, 24%; 95% CI, 8.7%-38.5%; P = .002) and included dysphagia (41% vs 0%), new neurological deficit (2% vs 9%), reoperations (6% vs 4%), and readmissions within 30 days (0% vs 7%).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy undergoing cervical spinal surgery, a ventral surgical approach did not significantly improve patient-reported physical functioning at 1 year compared with outcomes after a dorsal surgical approach.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02076113

This randomized trial compares the effects of ventral surgery (disk removal and fusion) vs dorsal surgery (laminectomy or laminoplasty) on patient-reported physical functioning 1 year after surgery among patients with multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy.

Introduction

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy is the most common cause of spinal cord dysfunction worldwide.1 Cervical myelopathy presents insidiously with clinical symptoms (gait instability, bladder dysfunction, fine finger motor difficulties) and signs (hyperreflexia, weakness, alteration of proprioception). Neurological dysfunction results from dynamic, repeated spinal cord compression from cervical spine degenerative arthritis, resulting in axonal stretch-associated injury2 and spinal cord ischemia.3 Surgery to decompress the spinal cord, usually with fusion, is frequently performed for severe or progressive symptoms. Of more than 112 400 cervical spine operations performed in the US annually,4 fusion for cervical myelopathy increased from 1993 to 2002.5 Surgery is associated with substantial postsurgical outpatient resource utilization6 and is expensive (US hospital charges exceeding $2 billion per year).4

The optimal surgical approach for treating cervical myelopathy remains unknown, and clinical equipoise exists for a randomized clinical trial.7 In US surgical practice, ventral and dorsal decompression/fusion dominate, with dorsal laminoplasty performed to a substantially lesser extent.8 In 2009, the Institute of Medicine designated cervical myelopathy as one of the top 100 national health priorities for comparative effectiveness research.9 Clinical outcomes are unsatisfactory in 30% of patients.10 Complications following cervical myelopathy surgery are common (17% in a 2013 prospective study),11 particularly for patients older than 74 years.12 Ventral fusion surgery has been associated with significantly better health-related quality of life with less neck pain (in a prospective observational study), and a state inpatient database showed a lower 5-year adjusted reoperation rate for ventral fusion surgery compared with dorsal fusion approaches (12% vs 17.7%, respectively).13,14

The objective of the Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy Surgical (CSM-S) trial was to determine whether a ventral surgical approach compared with a dorsal surgical approach for treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy improved patient-reported physical functioning at 1 year.

Methods

Study Design

The CSM-S trial was a randomized clinical trial performed at 14 sites in the US and 1 site in Canada between April 1, 2014, and March 30, 2018. Final 2-year follow-up was completed on April 15, 2020. Institutional review board approval at each site and written informed consent from all patients were obtained. Data were managed at the Stuart Spine Center at Lahey Hospital, Burlington, Massachusetts. The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are available in Supplement 1 and Supplement 2.

Patient Population

Inclusion criteria for screening and enrollment were age 45 to 80 years; cervical myelopathy, defined as having 2 or more of the following signs or symptoms: clumsy hands, gait disturbance, hyperreflexia, Babinski sign, bladder dysfunction, or ankle clonus; and 2 or more levels of spinal cord compression from the C3 to C7 vertebral levels, confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography myelography. Exclusion criteria included C2 to C7 kyphosis greater than 5° (measured on standing cervical lateral radiographs); segmental kyphotic deformity (defined as ≥3 disk osteophytes extending dorsal to a C2-C7 dorsal caudal line measured on cervical computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging)7; structurally significant ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament; previous cervical spinal surgery; or significant health-related comorbidity (American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status class ≥IV).15 Race/ethnicity data were collected from participants using fixed categories as required by federal sponsorship using the US Office of Management and Budget classification guidelines.

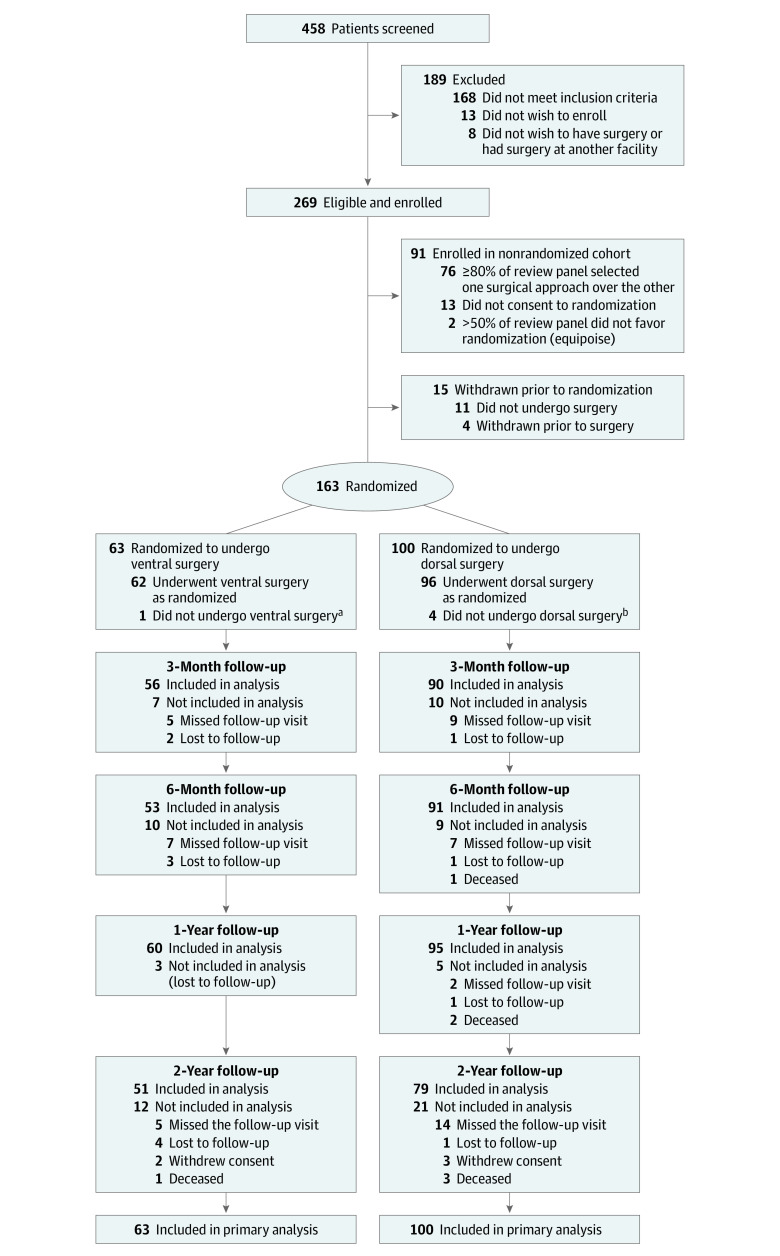

Radiology Image Analysis

Patients were screened and enrolled by trial coordinators at each site. Central site investigators reviewed screened case images to confirm eligibility prior to enrollment. An expert spine surgeon review panel (15 investigators) determined clinical equipoise/suitability for randomization and enrollment eligibility based on a brief clinical vignette plus 4 to 6 standardized images (Figure 1). Each expert made 2 assessments: (1) suitability for randomization (yes or no) and (2) characterization of preferred surgical approach (ventral or dorsal). Panel results of suitability for randomization were shared with each eligible patient, an approach that has resulted in increased rates of patient consent to randomization (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3).16,17 Clinical equipoise was defined as not met when either (1) 80% or more of panel members chose either ventral or dorsal surgery or (2) a simple majority voted against randomization.

Figure 1. Spinal Expert Review.

Clinical vignettes for each patient accompanied by relevant imaging studies were presented to an expert review panel. Imaging typically included sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MRI) image of the cervical spine, flexion-extension cervical radiographs, and relevant axial MRI images at the point of compression of the spinal cord. Ventral decompression and fusion would typically involve the removal of disks that are compressing the spinal cord from the front of the neck (blue arrow shown on sagittal T2-weighted MRI image). Dorsal decompression would involve decompression of the spinal column from the back of the neck (red arrow). A summary of expert opinion showing clinical equipoise was generated for surgeons and patients to review before accepting randomization (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3).

Study Interventions

Patients were randomized to either ventral or dorsal surgery, using a 2:3 block randomization scheme (5 or 10 patients per block) to provide roughly equal numbers of patients in ventral fusion and dorsal subgroups for analysis (since among patients randomized to a dorsal approach, surgeons chose whether to perform fusion or laminoplasty). Randomized assignment was site specific and was generated and transmitted electronically to each study coordinator from the study’s web-based research platform after each patient had consented to participate and after spinal expert review had confirmed clinical equipoise. Patients who wished to participate in the trial but did not consent to randomization and patients who did not meet criteria for clinical equipoise after expert review were placed in a nonrandomized cohort and were followed up. The goal of surgery was decompression of the spinal canal with restoration of circumferential cerebrospinal fluid around the spinal cord. Standardized surgical techniques are summarized below.

Ventral decompression with fusion18 was performed using a multilevel diskectomy (which could include partial- or single-level corpectomy) with fusion and plating.19,20 Allograft or autograft was used. Compressive osteophytes were removed using microsurgical technique. Fixation was performed using rigid, semiconstrained or dynamic titanium alloy plates.21

Dorsal decompression with fusion was performed using cervical laminectomy with application of lateral mass screws and rods.22 Local bone and allograft were used to perform a lateral mass fusion, which typically extended 1 level rostral to the uppermost decompressed level.

Dorsal laminoplasty was performed using an open-door approach (lamina opened unilaterally with hinge on the contralateral side of the lamina) with application of plates and screws at each treated level (eFigure 2 in Supplement 3). Ceramic or allograft laminar spacers were occasionally used with plates and screws to expand the canal diameter.23

Outcome Assessments

All functional and quality-of-life outcome measures were assessed by validated, standardized survey instruments (eAppendix in Supplement 3) administered in person by a site study coordinator (blinded to patient randomized group) preoperatively and 3, 6, 12, and 24 months postoperatively.

Primary Outcome Measure

The primary outcome measure was 1-year change in the physical component summary (PCS) score of the Short Form 36 (SF-36; version 2). The SF-36 PCS score represents patient-reported perceived physical functioning, limitations in work and activities due to bodily pain, and physical and general health. Scores range between 0 (worst) and 100 (best). The SF-36 PCS scores are calculated using population-adjusted norms to generate normalized scores with a mean of 50 (SD, ±10). The meaningful clinically important difference (MCID) is 5 points or more.24,25,26,27

Secondary Outcome Measures

Disease-specific function was assessed using the modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association (mJOA) scale (range, 0-18; higher scores indicate less myelopathy; MCID, 2 points)28,29 and the Neck Disability Index (NDI; range, 0-100; higher scores indicate more disability; MCID, 15 points).30,31 Preference-based health-related quality of life, reflecting US population values for calculation of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), was assessed using the EuroQol 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) score (0 indicates death; 1, perfect health; MCID, 0.05).32,33 Assessments were made 3, 6, 12, and (except the mJOA) 24 months postoperatively. Sagittal vertical axis34 was measured at 1 year postoperatively.

Participants logged workdays missed, and return to work was recorded at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. Adverse outcomes were recorded at 30 days and 1 year postoperatively. Major and minor adverse events were categorized by investigators who were blinded to the treatment received, but this was done in a post hoc fashion. Minor complications were defined as those that resolved within 3 months of surgery. Major complications included those that did not resolve within 3 months or required reoperation within 2 years or readmission to the hospital within 30 days. Health resource utilization information (imaging procedures, physician office visits, physical therapy sessions, and opioid medication utilization) was obtained using patient diaries reviewed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively with study coordinators.

Interim Analysis

No interim analysis was planned or performed. The data and safety monitoring board reviewed complications and mortality data at prespecified study intervals.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size estimates were calculated based on a 2-sided t test with α = .05 at 90% power using Power Analysis and Sample Size software, version 14 (NCSS LLC). Preliminary observational data from a nonrandomized, prospective, clinical pilot trial showed mean 1-year differences in SF-36 PCS scores of 8.7 points for ventral surgery compared with 4.0 points for dorsal fusion procedures. The estimated within-group standard deviation for the primary outcome was 9 points.13 A total sample size (2:3 ventral-dorsal randomization) required to detect a 5-point difference between the ventral and dorsal groups was calculated. A minimum sample size of 137 across both study groups was inflated by 15% to accommodate attrition during follow-up, for a final accrual goal of 159 participants randomized.

Primary analysis compared 1- and 2-year changes in SF-36 PCS scores for patients as randomized using a linear mixed-effects model. The model included baseline SF-36 PCS score, treatment group, time point (1 or 2 years), treatment × time point interaction, and surgeon as a random effect. Pairwise contrasts and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from the parameter estimates. Prespecified secondary analyses included 1- and 2-year change in secondary outcomes (NDI and EQ-5D) using the same modeling approach as the primary outcome and pairwise comparisons of the laminoplasty, dorsal fusion, and ventral fusion groups. These secondary analyses (analyzing patients in their actual treatment cohort) also reflected nonrandom treatment assignment in the dorsal group (dorsal laminoplasty vs dorsal fusion, as selected by the treating surgeon). Categorical outcomes (risk of complications, health resource utilization, return to work) were compared using χ2 tests with 95% confidence intervals for differences in proportions. No imputation was performed for missing data. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory. All tests were 2-sided with α = .05. Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Patient Characteristics

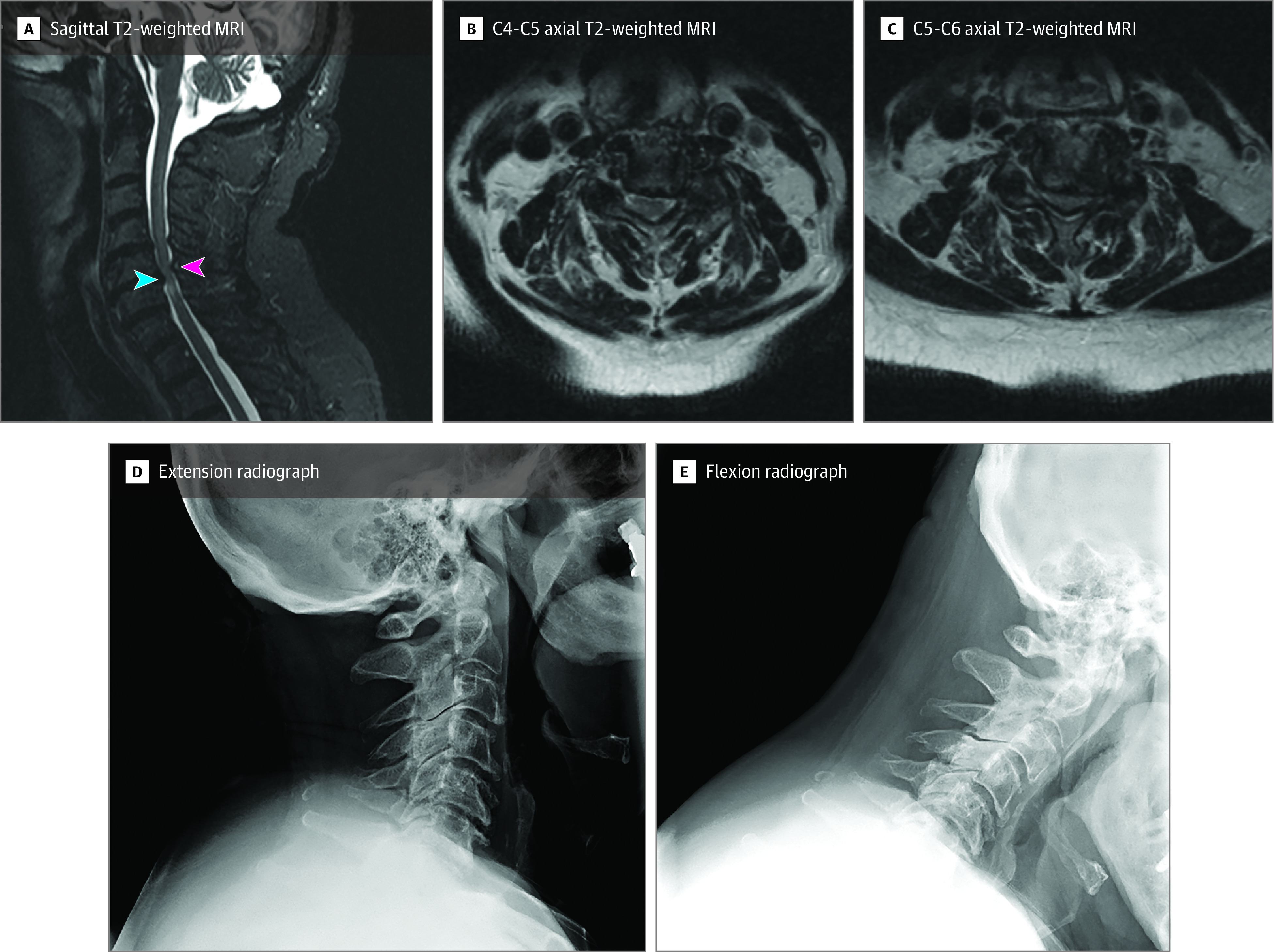

Participant flow through the trial is presented in Figure 2. At the 15 study sites, 458 patients were screened for eligibility, 269 were enrolled, and 163 were randomized for treatment (eTable 1 in Supplement 3). One-year follow-up was 95% for the randomized cohort; 6 patients (3 in the ventral group; 3 in the dorsal group) were lost to follow-up and 2 (1 with dorsal fusion; 1 with dorsal laminoplasty) died of unrelated causes (as adjudicated by the data and safety monitoring board). Of the 63 participants randomized to ventral fusion, 1 underwent a dorsal fusion procedure; of the 100 patients randomized to dorsal surgery, 4 underwent a ventral fusion procedure. Alternative surgery different from randomized strategy occurred because of either patient preference (n = 4) or surgeon preference (n = 1) regarding which operation they perceived was better. Ultimately, 66 patients underwent ventral fusion, 69 underwent dorsal fusion, and 28 underwent dorsal laminoplasty. All baseline variables were comparable between randomized groups (Table 1) and across actual treatment groups (eTable 2 in Supplement 3).

Figure 2. Flow of Participants in the Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy Surgical Trial.

The majority of the 189 patients screened who did not enroll were not eligible. Some were unwilling to complete study questionnaires or to consider randomization. A few ultimately did not choose to have surgery or had their surgery at another institution.

aOne patient randomized to ventral surgery underwent dorsal fusion surgery.

bFour patients randomized to dorsal surgery underwent ventral fusion surgery.

Table 1. Baseline Participant Characteristics.

| Characteristics | Ventral fusion (n = 63) | Dorsal fusion or laminoplasty (n = 100) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 62.0 (7.2) | 62.5 (8.8) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 34 (54.0) | 49 (49.0) |

| Female | 29 (46.0) | 51 (51.0) |

| Race, No. (%) | ||

| White | 54 (85.7) | 85 (85.0) |

| Black | 6 (9.5) | 7 (7.0) |

| Asian | 2 (3.2) | 3 (3.0) |

| American Indian | 1 (1.6) | 3 (3.0) |

| Not provided | 0 | 2 (2.0) |

| Hispanic ethnicity, No. (%) | 2 (3.2) | 4 (4.0) |

| Baseline work status, No. (%) | n = 63 | n = 98 |

| Working full-time | 17 (27.0) | 40 (40.8) |

| Retired | 14 (22.2) | 29 (29.6) |

| Not working, unable to work | 17 (27.0) | 18 (18.4) |

| Not working but able to work | 8 (12.7) | 7 (7.1) |

| Working part-time | 7 (11.1) | 4 (4.1) |

| ASA physical status class, No. (%)a | n = 61 | n = 98 |

| I (healthy) | 0 | 1 (1.0) |

| II (mild systemic disease) | 31 (50.8) | 46 (46.9) |

| III (significant systemic disease) | 30 (49.2) | 51 (52.0) |

| No. of stenotic levels | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.8 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.8) |

| No. (%) | ||

| 1 | 0 | 3 (3.0) |

| 2 | 22 (34.9) | 29 (29.0) |

| 3 | 33 (52.4) | 55 (55.0) |

| 4 | 8 (12.7) | 11 (11.0) |

| 5 | 0 | 2 (2.0) |

| NDI score, mean (SD)b | 38.6 (19.1) | 35.3 (20.4) |

| SF-36 summary score, mean (SD)c | ||

| Mental component | 45.6 (12.2) | 46.6 (12.1) |

| Physical component | 37.4 (8.8) | 37.3 (9.9) |

| mJOA scale score, mean (SD)d | 12.2 (2.7) | 12.1 (2.2) |

| EQ-5D score, mean (SD)e | 0.64 (0.21) | 0.61 (0.21) |

| EQ-5D visual analog scale score, mean (SD)f | 61.7 (20.9) | 63.1 (21.7) |

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification is used to assess a patient’s physical health and comorbidities to predict perioperative risk prior to surgery. Patients with class IV status (systemic disease that is life threatening) or higher were excluded from the study.15

The Neck Disability Index (NDI) ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores representing less disability. A typical patient with moderate neck pain and disability would have a score between 20 and 40.

Short Form 36 (SF-36) mental component and physical component summary scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better quality of life. A typical patient with cervical myelopathy who is being recommended surgery would have a score between 30-40.

The modified Japanese Orthopedic Association (mJOA) scale ranges from 0 to 17, with higher scores representing less dysfunction due to myelopathy. A typical patient with moderate cervical myelopathy has an mJOA score between 12 and 14. Many surgical studies show that patients with cervical myelopathy have mJOA scores in this range.11

For the EuroQol 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) score, 0 indicates death and 1 indicates a perfect health state. EQ-5D scores between 0.6 and 0.7 represent a moderate but significant reduction in overall health-related quality of life.

For the EQ-5D visual analogy scale, patients score their health state on a scale from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better health.

Main Treatment Effects

Primary Outcome Measure

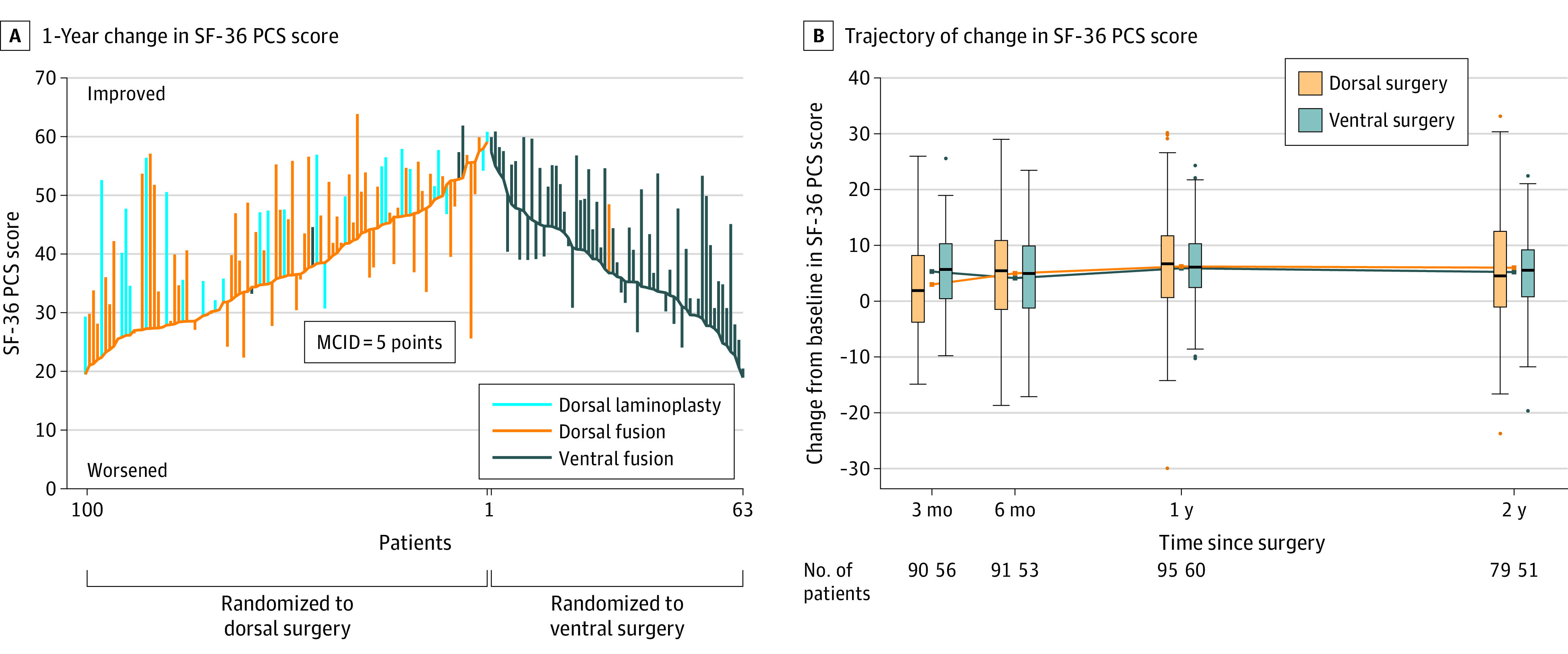

Five percent of participants had missing data for the primary outcome. Mean changes in SF-36 PCS scores did not differ significantly between the ventral and dorsal fusion groups at 1 year (estimated mean change, 5.9 vs 6.2 points, respectively; estimated mean difference, 0.3 points; 95% CI, −2.6 to 3.1; P = .86). At 2 years, mean changes in SF-36 PCS scores also did not significantly differ (estimated mean change, 5.2 [ventral] vs 6.0 [dorsal] points; estimated mean difference, 1.1 points; 95% CI, −1.9 to 4.2; P = .46) (eTable 3 in Supplement 3). A parallel-line plot35 of 1-year changes in SF-36 PCS scores for each patient is shown in Figure 3A, and the trajectory of mean change in SF-36 PCS scores over time for both groups is shown in Figure 3B. Both ventral and dorsal surgeries were associated with a clinically meaningful improvement in patient-reported physical functioning (at 1 year: ventral group, 5.9 points; dorsal group, 6.2 points; at 2 years: ventral group, 5.2 points; dorsal group, 6.0 points).

Figure 3. Comparative Outcomes Assessment.

MCID indicates minimum clinically important difference. A, Change in Short Form 36 physical component summary (SF-36 PCS) score for each patient in the trial from baseline to 1 year. Each bar extends from a patient’s baseline score to their 1-year score, with patients in each group ordered by baseline score. At baseline, mean SF-36 PCS scores for the dorsal and ventral groups were 37.3 (SD, 9.9) and 37.4 (SD, 8.8) points, respectively. The 1-year mean change from baseline in the SF-36 PCS score was 6.2 (SD, 10.2) points for dorsal surgery and 5.9 (SD, 8.2) points for ventral surgery. B, Trajectory of change in SF-36 PCS score by randomized group, with box plots showing distribution of change in SF-36 PCS scores at each time point. Box plots represent the distribution of SF-36 PCS scores: the center line of the box is the median, with the box tops and bottoms indicating the interquartile range (IQR). The upper whisker is the largest value that is less than or equal to the third quartile plus 1.5 times the IQR, and the lower whisker is the smallest value that is greater than or equal to the first quartile minus 1.5 times the IQR. Circles represent more extreme values.

Secondary Outcome Measures

There were no significant differences in 6 of 7 prespecified secondary outcomes (Table 2; eTables 4-5 and eFigure 3A in Supplement 3). Of 63 patients who were working preoperatively, 45 (71%) returned to work by 1 year; this did not differ significantly between the ventral and dorsal groups (69.6% vs 72.5%, respectively; difference, −2.9%; 95% CI, −26.2% to 20.4%; P = .80) (eFigure 3A in Supplement 3). Ventral surgery was associated with a significantly greater risk of any complications than dorsal surgery (47.6% vs 24.0%; difference, 23.6%; 95% CI, 8.7%-38.5%; P = .002), including dysphagia (41% vs 0%, respectively), new neurological deficit (2% vs 9%), reoperations (6% vs 4%), and readmissions within 30 days (0% vs 7%). There was no significant difference in the risk of major complications (22.2% [ventral] vs 17.0% [dorsal]; difference, 5.2%; 95% CI, −7.4% to 17.9%; P = .41), although ventral surgery was associated with greater risk of minor complications (27.0% vs 7.0%; difference, 20.0%; 95% CI, 7.9%-32.0%; P < .001), of which dysphagia was the most prevalent. Specific complications by surgical approach are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Adverse Events by Surgical Strategy.

| Adverse events | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ventral fusion (n = 66) | Dorsal fusion (n = 69) | Dorsal laminoplasty (n = 28) | |

| Any complicationsa | 31 (47) | 20 (29) | 3 (11) |

| Major complicationsb | 14 (21) | 15 (22) | 2 (7) |

| Prolonged dysphagia | 9 (14) | 0 | 0 |

| Motor radiculopathyc | 1 (2) | 8 (12) | 0 |

| Spinal cord injury | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.6) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Delayed wound healing | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Minor complicationsd | 18 (27) | 5 (7) | 1 (4) |

| Dysphagia | 18 (27) | 0 | 0 |

| Infection | 0 | 2 (3) | 1 (4) |

| Motor radiculopathyc | 0 | 2 (3) | 0 |

| Delayed wound healing | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Reoperations | 4 (6) | 4 (6) | 0 |

| Readmissions within 30 days | 0 | 6 (8.7) | 1 (3.6) |

| Cervical (C5) paresis | 0 | 2 (2.9) | 0 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 |

| Ileus | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 |

| Uncontrolled neck pain | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 |

| Infection | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 |

| Fever (unknown source) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.6) |

Patients may have had more than 1 complication, so totals may be less than the sum of categories.

Major complications included adverse events that were ongoing at 3 months, reoperations within 2 years, and 30-day readmissions.

All cases of postoperative motor radiculopathy were related to C5 nerve root dysfunction.

Minor complications were those that resolved within 3 months.

Health resource utilization data (eTable 5 in Supplement 3) were obtained for all patients. At 1 year, there were no significant differences between groups in the proportions who received any diagnostic testing, opioid treatment, or physical therapy.

Dorsal Procedure Selection

Not all spine surgeons are trained to perform dorsal laminoplasty. Of the 24 enrolling surgeons, 8 with dorsal laminoplasty skills chose between dorsal laminoplasty and dorsal fusion for patients randomized to dorsal surgery (eTable 6 in Supplement 3). Among 58 dorsal patients treated by surgeons who performed both laminoplasty and fusion, baseline demographic characteristics were comparable for dorsal laminoplasty vs dorsal fusion patients. The majority (5 of 8) of these surgeons chose dorsal laminoplasty more frequently than dorsal fusion.

Secondary Analyses

In nonrandomized comparisons, secondary analyses were conducted by the type of surgery received (ie, ventral fusion, dorsal fusion, or dorsal laminoplasty). Overall, there was a significant association between type of surgery and change in SF-36 PCS scores (P = .02). Specifically, at 1 year, dorsal laminoplasty was associated with significantly greater improvement in SF-36 PCS scores compared with dorsal fusion (estimated mean change, 9.6 vs 4.6 points; estimated mean difference, 5.0; 95% CI, 0.95-9.0; P = .02). Changes in SF-36 PCS scores were not statistically significantly different between dorsal laminoplasty and ventral fusion at 1 year (estimated mean change, 9.6 vs 5.7 points; estimated mean difference, 3.9; 95% CI, −0.2 to 7.9; P = .06) or between dorsal fusion and ventral fusion (estimated mean change, 4.6 vs 5.7 points; estimated mean difference, −1.1; 95% CI, −4.1 to 1.9; P = .46). At 2 years, dorsal laminoplasty was associated with a significant improvement in SF-36 PCS outcomes that was sustained compared with dorsal fusion (estimated mean change, 10.1 vs 4.3 points; estimated mean difference, 5.8; 95% CI, 1.5-10.1; P = .01) and ventral fusion (estimated mean change, 10.1 vs 5.0 points; estimated mean difference, 5.1; 95% CI, 0.8-9.4; P = .02). There was no statistically significant difference in SF-36 PCS scores between the ventral and dorsal fusion groups at 2 years (estimated mean change, 5.0 vs 4.3 points; estimated mean difference, −0.7 points; 95% CI, −3.9 to 2.4; P = .65) (eTable 7 and eFigure 4 in Supplement 3). Changes in the EQ-5D, the NDI, the mJOA, and postoperative sagittal vertical axis are summarized in eTable 8 in Supplement 3. Comparisons by surgical approach of the proportion of patients who returned to work are summarized in eFigure 3B in Supplement 3.

Type of surgery was associated with a significant difference in the risk of complications (ventral fusion, 47.0% [95% CI, 34.6%-60.0%]; dorsal fusion, 29.0% [95% CI, 18.7%-41.2%]; dorsal laminoplasty, 10.7% [95% CI, 2.3%-28.2%]; P = .002). At 1 year, type of surgery was also associated with a statistically significant difference in the rate of any diagnostic testing (ventral fusion, 78.8% [95% CI, 67.0%-87.9%]; dorsal fusion, 87.0% [95% CI, 76.7%-93.9%]; dorsal laminoplasty, 60.7% [95% CI, 40.6%-78.5%]; P = .02), opioid treatment (ventral fusion, 45.5% [95% CI, 33.1%-58.2%]; dorsal fusion, 65.2% [95% CI, 52.8%-76.3%]; dorsal laminoplasty, 39.3% [95% CI, 21.5%-59.4%]; P = .02), and ongoing physical therapy (ventral fusion, 16.7% [95% CI, 8.6%-27.9%]; dorsal fusion, 21.7% [95% CI, 12.7%-33.3%]; dorsal laminoplasty, 0% [95% CI, 0%-12.3%]; P = .03) (eTable 9 in Supplement 3).

Discussion

Among patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy undergoing cervical spinal surgery, a ventral surgical approach, compared with a dorsal surgical approach, did not significantly improve patient-reported physical functioning at 1 or 2 years. Both ventral and dorsal surgeries were associated with clinically meaningful improvements in patient-reported physical functioning.

This trial is the first randomized clinical trial, to our knowledge, of alternative surgical approaches for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. This trial randomized one-third of patients with cervical myelopathy who were screened from multiple regions within North America, making the results more likely to be generalizable. Unlike the randomized assignment to ventral vs dorsal approach, in the dorsal group, the surgeon chose between laminectomy with fusion vs laminoplasty, resulting in potential selection bias when comparing between dorsal approaches. In the nonrandomized analysis by type of treatment (disaggregating dorsal fusion and dorsal laminoplasty), laminoplasty was associated with significantly better patient-reported functioning, significantly fewer complications, and significantly less health service and resource utilization compared with ventral fusion and dorsal fusion. The differences observed at 1 year were sustained and significant at 2 years postoperatively.

There is substantial practice variation associated with surgical treatment of cervical myelopathy. Laminoplasty, initially described in Japan in the early 1980s, is a common form of cervical myelopathy treatment in Asia and Europe, whereas ventral or dorsal fusions are favored in North America.36,37 In general, fusion surgery is preferred for patients with neck pain.38 Ventral surgery is preferable to laminoplasty in patients with cervical kyphosis greater than 13° or poor cervical sagittal alignment.28,39

As confirmed by this trial, surgery is effective for treatment of myelopathy. But only recently, in response to patient advisers (including those who participated in this trial’s design), has significant attention focused on postoperative function, quality of life, and surgical complications. Complications were observed in 48% of ventral surgery patients (most of which were minor, including dysphagia that resolved within 1 year after surgery). Complications were recorded by independent study coordinators who asked patients about specific concerns including problems with swallowing, which may have identified a higher frequency of dysphagia and other complications compared with studies using alternative methods. Laminoplasty was associated with the lowest complication rate.

In this trial, laminoplasty was associated with improved outcomes and less outpatient medical service utilization than ventral fusion or dorsal fusion surgery. Charges and Medicare payments from laminoplasty procedures are lower than for fusion procedures.40 The current study’s clinical outcomes results underscore the importance of producing a more extensive and formal economic analysis to examine the societal cost-effectiveness of these 3 alternative surgical approaches.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, laminoplasty was not included in the randomization because it is not widely used in the US (at the time this trial was designed, only 5 of the 15 major centers routinely performed the procedure, limiting available surgeon experience and skill to generate clinical equipoise for randomization among ventral fusion, dorsal fusion, and laminoplasty). Therefore, this trial’s design randomized more patients to the dorsal group with the aim to permit secondary (nonrandomized) analyses comparing laminoplasty with ventral fusion and dorsal fusion surgery. The results observed for laminoplasty, however, should be interpreted with caution. Second, the number of patients available for subgroup analysis was limited. Third, although there were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics collected in this trial among the surgical groups, surgeon selection bias could have occurred in the trial’s dorsal group. There may have been subtle differences suggestive of less severe disease among those who received laminoplasty. Future surgical education on laminoplasty techniques and indications would be important for US spine surgeons to refine the appropriate population of patients with cervical myelopathy who are candidates for laminoplasty.

Conclusions

Among patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy undergoing cervical spinal surgery, a ventral surgical approach did not significantly improve patient-reported physical functioning at 1 year compared with outcomes after a dorsal surgical approach.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. CSM-S Trial Enrollment by Site and Strategy

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of Patients by Actual Treatment Groups

eTable 3. Comparison of 1- and 2-Year Change in SF-36 Physical Component Summary Score

eTable 4. Primary Analysis, Secondary Outcomes: Mixed Effects Model Comparisons of 1- and 2-Year Change in Outcome Scores by Randomized Groups

eTable 5. Cumulative Health Resource Utilization Over 1-Year Between Ventral and Dorsal Approach

eTable 6. Baseline Characteristics of Dorsal Laminoplasty and Dorsal Fusion Patients Treated by Surgeons Who Performed Both Procedures

eTable 7. Secondary Analysis, Primary Outcome: Mixed Effects Model Comparisons of 1- and 2-Year Change in Outcome Scores by Actual Treatment Groups

eTable 8. Secondary Analysis, Secondary Outcomes: Mixed Effects Model Comparisons of 1- and 2-Year Change in Outcome Scores by Actual Treatment Groups

eTable 9. Cumulative Health Resource Utilization Over 1-Year Varied by Actual Treatment Groups

eFigure 1. Spinal Experts Review Polling Results

eFigure 2. Surgical Strategies for Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy

eFigure 3. Return to Work

eFigure 4. Secondary Analysis, Primary Outcome

eAppendix. Outcome Assessment Documents

CSM-S Trial Investigators

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Badhiwala JH, Ahuja CS, Akbar MA, et al. Degenerative cervical myelopathy: update and future directions. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16(2):108-124. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0303-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henderson FC, Geddes JF, Vaccaro AR, et al. Stretch-associated injury in cervical spondylotic myelopathy: new concept and review. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(5):1101-1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akter F, Yu X, Qin X, et al. The pathophysiology of degenerative cervical myelopathy and the physiology of recovery following decompression. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:138. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patil PG, Turner DA, Pietrobon R. National trends in surgical procedures for degenerative cervical spine disease: 1990-2000. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(4):753-758. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000175729.79119.1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lad SP, Patil CG, Berta S, et al. National trends in spinal fusion for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Surg Neurol. 2009;71(1):66-69. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2008.02.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witiw CD, Tetreault LA, Smieliauskas F, et al. Surgery for degenerative cervical myelopathy: a patient-centered quality of life and health economic evaluation. Spine J. 2017;17(1):15-25. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2016.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghogawala Z, Coumans JV, Benzel EC, et al. Ventral versus dorsal decompression for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: surgeons’ assessment of eligibility for randomization in a proposed randomized controlled trial: results of a survey of the Cervical Spine Research Society. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(4):429-436. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000255068.94058.8a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Research, statistics, data, and systems physician supplier procedure summary. Accessed December 2, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Physician-Supplier-Procedure-Summary/index

- 9.Institute of Medicine . Appendix C, Table 5-13: musculoskeletal disorders priority topics. In: Learning What Works: Infrastructure Required for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Accessed April 30, 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64788/table/appendixes.app3.t13/?report=objectonly

- 10.Zaveri GR, Jaiswal NP. A comparison of clinical and functional outcomes following anterior, posterior, and combined approaches for the management of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Indian J Orthop. 2019;53(4):493-501. doi: 10.4103/ortho.IJOrtho_8_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fehlings MG, Barry S, Kopjar B, et al. Anterior versus posterior surgical approaches to treat cervical spondylotic myelopathy: outcomes of the Prospective Multicenter AOSpine North America CSM Study in 264 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38(26):2247-2252. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang MC, Chan L, Maiman DJ, et al. Complications and mortality associated with cervical spine surgery for degenerative disease in the United States. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(3):342-347. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000254120.25411.ae [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghogawala Z, Martin B, Benzel EC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of ventral vs dorsal surgery for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Neurosurgery. 2011;68(3):622-630. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31820777cf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King JT Jr, Abbed KM, Gould GC, et al. Cervical spine reoperation rates and hospital resource utilization after initial surgery for degenerative cervical spine disease in 12,338 patients in Washington State. Neurosurgery. 2009;65(6):1011-1022. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000360347.10596.BD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurwitz EE, Simon M, Vinta SR, et al. Adding examples to the ASA-Physical Status Classification improves correct assignment to patients. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(4):614-622. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghogawala Z, Schwartz JS, Benzel EC, et al. Increased patient enrollment to a randomized surgical trial through equipoise polling of an expert surgeon panel. Ann Surg. 2016;264(1):81-86. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghogawala Z, Dziura J, Butler WE, et al. Laminectomy plus fusion versus laminectomy alone for lumbar spondylolisthesis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(15):1424-1434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1508788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith GW, Robinson RA. The treatment of certain cervical-spine disorders by anterior removal of the intervertebral disc and interbody fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1958;40-A(3):607-624. doi: 10.2106/00004623-195840030-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillard VH, Apfelbaum RI. Surgical management of cervical myelopathy: indications and techniques for multilevel cervical discectomy. Spine J. 2006;6(6)(suppl):242S-251S. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart TJ, Schlenk RP, Benzel EC. Multiple level discectomy and fusion. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(1)(suppl 1):S143-S148. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000217015.96212.1B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwon BK, Vaccaro AR, Grauer JN, Beiner JM. The use of rigid internal fixation in the surgical management of cervical spondylosis. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(1)(suppl 1):S118-S129. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000249222.57709.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang RC, Girardi FP, Poynton AR, Cammisa FP Jr. Treatment of multilevel cervical spondylotic myeloradiculopathy with posterior decompression and fusion with lateral mass plate fixation and local bone graft. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16(2):123-129. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200304000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heller JG, Edwards CC II, Murakami H, Rodts GE. Laminoplasty versus laminectomy and fusion for multilevel cervical myelopathy: an independent matched cohort analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(12):1330-1336. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200106150-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JEJ, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A Manual for Users of Version 1. 2nd ed. QualityMetric Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Copay AG, Glassman SD, Subach BR, et al. Minimum clinically important difference in lumbar spine surgery patients: a choice of methods using the Oswestry Disability Index, Medical Outcomes Study questionnaire Short Form 36, and pain scales. Spine J. 2008;8(6):968-974. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glassman S, Gornet MF, Branch C, et al. MOS Short Form 36 and Oswestry Disability Index outcomes in lumbar fusion: a multicenter experience. Spine J. 2006;6(1):21-26. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birkmeyer NJ, Weinstein JN, Tosteson AN, et al. Design of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT). Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(12):1361-1372. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206150-00020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suda K, Abumi K, Ito M, et al. Local kyphosis reduces surgical outcomes of expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(12):1258-1262. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000065487.82469.D9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tetreault L, Nouri A, Kopjar B, et al. The minimum clinically important difference of the modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association scale in patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(21):1653-1659. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coric D, Finger F, Boltes P. Prospective randomized controlled study of the Bryan cervical disc: early clinical results from a single investigational site. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4(1):31-35. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.4.1.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badhiwala JH, Witiw CD, Nassiri F, et al. Patient phenotypes associated with outcome following surgery for mild degenerative cervical myelopathy: a principal component regression analysis. Spine J. 2018;18(12):2220-2231. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suhonen R, Virtanen H, Heikkinen K, et al. Health-related quality of life of day-case surgery patients: a pre/posttest survey using the EuroQoL-5D. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(1):169-177. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9292-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato S, Oshima Y, Matsubayashi Y, et al. Minimum clinically important difference in outcome scores among patients undergoing cervical laminoplasty. Eur Spine J. 2019;28(5):1234-1241. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-05945-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang JA, Scheer JK, Smith JS, et al. The impact of standing regional cervical sagittal alignment on outcomes in posterior cervical fusion surgery. Neurosurgery. 2012;71(3):662-669. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31826100c9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schriger DL. Graphic portrayal of studies with paired data: a tutorial. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(2):239-246. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurokawa R, Kim P. Cervical laminoplasty: the history and the future. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2015;55(7):529-539. doi: 10.2176/nmc.ra.2014-0387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bakhsheshian J, Mehta VA, Liu JC. Current diagnosis and management of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Global Spine J. 2017;7(6):572-586. doi: 10.1177/2192568217699208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Highsmith JM, Dhall SS, Haid RW Jr, et al. Treatment of cervical stenotic myelopathy: a cost and outcome comparison of laminoplasty versus laminectomy and lateral mass fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;14(5):619-625. doi: 10.3171/2011.1.SPINE10206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lau D, Winkler EA, Than KD, et al. Laminoplasty versus laminectomy with posterior spinal fusion for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy: influence of cervical alignment on outcomes. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017;27(5):508-517. doi: 10.3171/2017.4.SPINE16831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warren DT, Ricart-Hoffiz PA, Andres TM, et al. Retrospective cost analysis of cervical laminectomy and fusion versus cervical laminoplasty in the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Int J Spine Surg. 2013;7:e72-e80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsp.2013.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. CSM-S Trial Enrollment by Site and Strategy

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of Patients by Actual Treatment Groups

eTable 3. Comparison of 1- and 2-Year Change in SF-36 Physical Component Summary Score

eTable 4. Primary Analysis, Secondary Outcomes: Mixed Effects Model Comparisons of 1- and 2-Year Change in Outcome Scores by Randomized Groups

eTable 5. Cumulative Health Resource Utilization Over 1-Year Between Ventral and Dorsal Approach

eTable 6. Baseline Characteristics of Dorsal Laminoplasty and Dorsal Fusion Patients Treated by Surgeons Who Performed Both Procedures

eTable 7. Secondary Analysis, Primary Outcome: Mixed Effects Model Comparisons of 1- and 2-Year Change in Outcome Scores by Actual Treatment Groups

eTable 8. Secondary Analysis, Secondary Outcomes: Mixed Effects Model Comparisons of 1- and 2-Year Change in Outcome Scores by Actual Treatment Groups

eTable 9. Cumulative Health Resource Utilization Over 1-Year Varied by Actual Treatment Groups

eFigure 1. Spinal Experts Review Polling Results

eFigure 2. Surgical Strategies for Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy

eFigure 3. Return to Work

eFigure 4. Secondary Analysis, Primary Outcome

eAppendix. Outcome Assessment Documents

CSM-S Trial Investigators

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement