Enteroviruses include many known and emerging pathogens, such as poliovirus, enteroviruses 71 and D68, and others. However, licensed vaccines are available only against poliovirus and enterovirus 71, and specific anti-enterovirus therapeutics are lacking. Enterovirus infection induces the massive remodeling of intracellular membranes and the development of specialized domains harboring viral replication complexes, replication organelles. Here, we investigated the roles of small Arf GTPases during enterovirus infection. Arfs control distinct steps in intracellular membrane traffic, and one of the Arf-activating proteins, GBF1, is a cellular factor required for enterovirus replication. We found that all Arfs expressed in human cells, including Arf6, normally associated with the plasma membrane, are recruited to the replication organelles and that Arf1 appears to be the most important Arf for enterovirus replication. These results document the rewiring of the cellular membrane pathways in infected cells and may provide new ways of controlling enterovirus infections.

KEYWORDS: GBF1, GTPases Arf, RNA replication, enteroviruses, membrane metabolism, picornavirus, replication organelles

ABSTRACT

Enterovirus replication requires the cellular protein GBF1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for small Arf GTPases. When activated, Arfs associate with membranes, where they regulate numerous steps of membrane homeostasis. The requirement for GBF1 implies that Arfs are important for replication, but which of the different Arfs function(s) during replication remains poorly understood. Here, we established cell lines expressing each of the human Arfs fused to a fluorescent tag and investigated their behavior during enterovirus infection. Arf1 was the first to be recruited to the replication organelles, where it strongly colocalized with the viral antigen 2B and mature virions but not double-stranded RNA. By the end of the infectious cycle, Arf3, Arf4, Arf5, and Arf6 were also concentrated on the replication organelles. Once on the replication membranes, all Arfs except Arf3 were no longer sensitive to inhibition of GBF1, suggesting that in infected cells they do not actively cycle between GTP- and GDP-bound states. Only the depletion of Arf1, but not other class 1 and 2 Arfs, significantly increased the sensitivity of replication to GBF1 inhibition. Surprisingly, depletion of Arf6, a class 3 Arf, normally implicated in plasma membrane events, also increased the sensitivity to GBF1 inhibition. Together, our results suggest that GBF1-dependent Arf1 activation directly supports the development and/or functioning of the replication complexes and that Arf6 plays a previously unappreciated role in viral replication. Our data reveal a complex pattern of Arf activation in enterovirus-infected cells that may contribute to the resilience of viral replication in different cellular environments.

IMPORTANCE Enteroviruses include many known and emerging pathogens, such as poliovirus, enteroviruses 71 and D68, and others. However, licensed vaccines are available only against poliovirus and enterovirus 71, and specific anti-enterovirus therapeutics are lacking. Enterovirus infection induces the massive remodeling of intracellular membranes and the development of specialized domains harboring viral replication complexes, replication organelles. Here, we investigated the roles of small Arf GTPases during enterovirus infection. Arfs control distinct steps in intracellular membrane traffic, and one of the Arf-activating proteins, GBF1, is a cellular factor required for enterovirus replication. We found that all Arfs expressed in human cells, including Arf6, normally associated with the plasma membrane, are recruited to the replication organelles and that Arf1 appears to be the most important Arf for enterovirus replication. These results document the rewiring of the cellular membrane pathways in infected cells and may provide new ways of controlling enterovirus infections.

INTRODUCTION

Enterovirus is a genus of the family Picornaviridae of small plus-strand RNA [(+)RNA] viruses of vertebrate hosts. Enteroviruses include many important human pathogens, such as rhinoviruses, poliovirus, enteroviruses 71 and D68, and others. Licensed vaccines are currently available only against poliovirus and enterovirus 71 (1, 2), and no therapeutics are officially approved to treat any enterovirus infections, although the development of experimental drugs is ongoing (3).

Enteroviruses have a nonenveloped icosahedral capsid containing a (+)RNA genome. The viral proteins are synthesized as one polyprotein, which is processed co- and posttranslationally by viral proteases into about a dozen structural and replication proteins. Replication complexes of enteroviruses, like those of all (+)RNA viruses of eukaryotes, are formed in association with specialized membranous domains, replication organelles. Enteroviruses are known to hijack several cellular lipid synthesis and membrane metabolism pathways to induce the formation of these membranous structures and to create a specific biochemical environment necessary for the functioning of the viral replication machinery (4–6). Importantly, diverse enteroviruses often share requirements for the same cellular factors, which attract significant attention as potential targets for future development of broad-spectrum antiviral therapeutics (3).

One of the cellular factors critically important for enterovirus replication is GBF1 (Golgi-BFA-sensitive factor 1). GBF1 is a large multidomain protein mainly localized at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-Golgi interface, where it supports the structural integrity of the Golgi and the function of the cellular secretory pathway (7–9). A fraction of the cellular pool of GBF1 is also found on lipid droplets and the trans-Golgi network, but the role of the protein at these locations remains less well understood (10–12).

GBF1 acts as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for the small cellular GTPases Arf (Arf GEF). Arfs cycle between an inactive cytosolic GDP-bound and an activated, membrane-associated GTP-bound form. Arfs have low intrinsic ability to exchange GDP for GTP and require the GEFs to catalyze GDP expulsion, which allows the binding of the activating GTP. The GEF activity of GBF1 (and of all other Arf GEFs) is mediated by a highly conserved, centrally located, ∼200-amino-acid-long Sec7 domain. The Sec7 domain contains a critical glutamic acid residue that inserts and destabilizes the Arf-GDP binding, leading to GDP dissociation. The Sec7 domain of GBF1 is inhibited by the fungal metabolite brefeldin A (BFA) and similar molecules, which lock a transient complex of Arf-GDP and GBF1 in a nonfunctional conformation on the membrane (8, 13, 14).

Importantly, BFA is a potent inhibitor of replication of many (+)RNA viruses, including enteroviruses (15–19). The inhibitory effect of BFA and similar molecules on enterovirus replication can be relieved by the overexpression of wild-type GBF1 or GBF1 made BFA resistant by mutations within the BFA-binding residues in the Sec7 domain, directly implicating GBF1 in the enterovirus life cycle. Further experiments established that GBF1 is required to support the step of RNA replication (18, 19). Notably, the replication of enteroviruses in BFA-treated cells can be efficiently rescued by severely truncated GBF1 variants, deficient in supporting cellular metabolism, but not by GBF1 mutants containing a catalytically nonfunctional Sec7 domain (20, 21). This strongly suggests that GBF1-mediated Arf activation is required for enterovirus replication. However, the overexpression of either wild-type Arfs or Arf mutants locked in the activated conformation, so that their targeting to membranes and interaction with Arf effector proteins does not depend on GEF activity, could not relieve the BFA inhibition of enterovirus replication (18, 19). Moreover, depletions of individual Arfs produced controversial results. Knockdown or knockout of Arf1 to -5 individually or in pairwise combinations did not significantly affect replication of coxsackieviruses B3 (CVB3) and B4 (19, 22), but the simultaneous knockdown of Arf1 and -3 was reported to inhibit replication of enterovirus 71 (23). Thus, while the Arf-activating function of GBF1 appears to be critical for enterovirus replication, the role of individual Arfs in the replication process remains enigmatic.

There are six mammalian Arf proteins (Arf1 to -6), but primates have lost Arf2. Based on their structural properties, Arfs are divided into three classes. In human cells, class 1 comprises Arf1 and -3, class 2 has Arf4 and -5, and the most structurally diverse, Arf6, is the only member of class 3 (24). The activation of the distinct Arfs is subject to tight spatial and temporal regulation and is catalyzed by distinct cellular GEFs, including GBF1 (25). GBF1 extensively colocalizes with Arf1, -3, -4, and -5 at the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) and the Golgi, but not with Arf6, which is predominantly detected at the plasma membrane (26). Furthermore, GBF1 appears to activate Arf1, -3, -4, and -5 within the Golgi and at the trans-Golgi network but does not activate Arf6 in these compartments (9, 27, 28). The activated Arfs interact with numerous effector proteins, defining the specific composition of membrane-associated proteins on cellular organelles and coordinating multiple steps of intracellular membrane traffic (24, 25, 29).

To get a better insight into the role of different Arfs in enterovirus infection, we established cell lines stably expressing all human Arfs fused to fluorescent proteins. Such a system allowed us to observe the dynamics of Arf recruitment to replication organelles upon viral infection without the artifacts usually associated with transient transfections, such as activation of antiviral signaling due to the presence of plasmid DNA in the cytoplasm. Using these cell lines and other experimental systems, we systematically investigated the contributions of different Arf isoforms to the replication of enteroviruses.

We report that poliovirus induces a complex pattern of engagement of different Arfs. Only Arf1 was rapidly recruited to the replication membranes in the early-middle stages of the infectious cycle, while a significant proportion of other Arfs was not associated with viral antigens at early times. However, by the end of the replication cycle, all Arfs, including Arf6, were massively associated with the replication membranes. A similar recruitment of all Arf isoforms was observed for coxsackievirus B3, suggesting that a common complex pattern of engagement of different Arfs is induced by diverse enteroviruses. The different dynamics of Arf isoform recruitment was confirmed in cells expressing pairs of Arfs fused to different fluorescent proteins. Among the different viral antigens, 2B and mature virions demonstrated the strongest association with Arf1-enriched membranes, while the signal for double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) was strongly separated from that of Arf1, suggesting that dsRNA is sequestered in biochemically distinct membranous domains.

Interestingly, only Arf3 required a continuous BFA-sensitive GEF activity to remain associated with the membranes in infected cells. Knockdown of expression of individual Arf isoforms had minimal effect on viral replication, confirming the previously reported data (19, 22). However, the knockdown of expression of Arf1 and, to a certain extent, Arf6, but not other Arfs, significantly increased the sensitivity of enterovirus replication to BFA, suggesting that GBF1-driven activation of Arf1 and, to a lesser extent, Arf6, directly supports the development and/or functioning of the viral replication complexes. Thus, our data demonstrate a complex dynamic pattern of recruitment of different Arf isoforms to the replication organelles of diverse enteroviruses and suggest a continuous remodeling of these membranes by effectors of these sequential Arfs during the replication cycle.

RESULTS

Establishing cell lines expressing human Venus-tagged Arfs.

To visualize Arf recruitment profiles upon infection, we established cell lines expressing all human Arfs (Arf1, -3, -4, -5, and -6) C-terminally fused to a green fluorescent protein (GFP), Venus. Such Arf fusions are well characterized and broadly used in cell biology research (30–33). They are usually transiently expressed after plasmid transfection, but DNA transfection-based systems are not well suited for studying viral infection, since the presence of the DNA in the cytoplasm triggers innate immune signaling (34). Thus, we transduced HeLa cells with retroviral vectors coding for the individual Arf-Venus constructs and established corresponding stable cell lines. These cell lines contain the combined populations of cells that survived in the selective medium after transduction, with ∼80% of cells showing Arf-Venus signals of various intensities. The heterogeneous composition of cells expressing Arf-Venus constructs allows minimizing possible artifacts associated with different provirus integration sites and the level of transgene expression in a particular population of transduced cells.

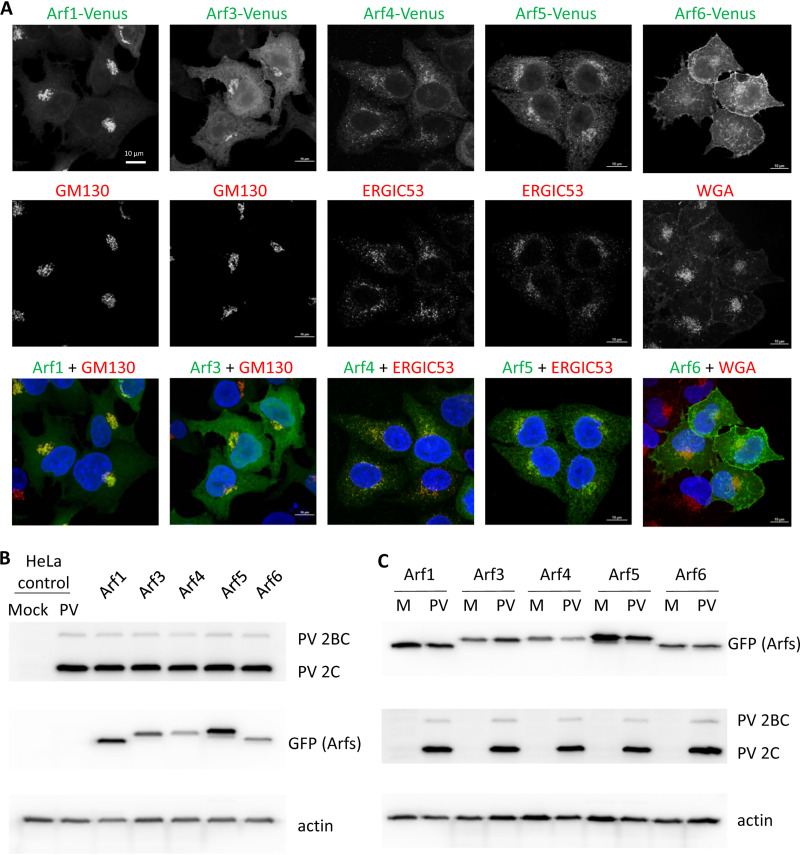

To assess whether the fluorescently tagged Arfs behave as authentic proteins, we analyzed their colocalization with markers for cellular organelles. Venus-tagged Arf1 and Arf3 were concentrated in a perinuclear Golgi-like pattern that colocalized with the cis-Golgi marker GM130, while Arf4 and Arf5 demonstrated a more diffuse perinuclear distribution characteristic of the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) and, accordingly, strongly colocalized with the ERGIC53 marker, in agreement with previously reported localizations of these Arfs (35) (Fig. 1A and data not shown). Arf6-Venus was mostly associated with the plasma membrane, the established localization of this Arf (36, 37), although a weak Arf6-Venus signal on the intracellular structures could be seen in some cells (Fig. 1A). These data demonstrate that stably expressed Arf-Venus constructs recapitulate the behavior expected from functional Arf isoforms.

FIG 1.

Characterization of cell lines expressing individual Arf-Venus fusions. (A) HeLa cells stably expressing corresponding Arf-Venus fusions were analyzed with antibodies against cis- and trans-Golgi markers ERGIC53 and GM130, respectively. Plasma membrane was stained with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA). Nuclear DNA was stained by Hoechst 33342 (blue). Fluorescently tagged Arfs demonstrated the expected behavior. (B) Expression of fluorescently tagged Arfs does not interfere with poliovirus replication. The original HeLa cell line and its derivatives stably expressing individual Arf-Venus fusions were mock infected or infected with poliovirus (50 PFU/cell), the cells were collected at 6 h p.i. in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer, and the total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with an antibody against viral antigen 2C and anti-GFP antibodies that recognize the Arf-Venus fusions. Actin is shown as a loading control. (C) Arf-Venus fusions are not significantly affected by poliovirus infection. Cell lines expressing corresponding Arf-Venus fusions were infected with poliovirus (PV; 50 PFU/cell) or mock infected (M), the cells were collected at 6 h p.i. in RIPA buffer, and the total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with an antibody against viral antigen 2C and anti-GFP antibodies that recognize the Arf-Venus fusions. Actin is shown as a loading control.

Finally, we tested if the expression of the Arf-Venus constructs interferes with poliovirus replication. As shown in Fig. 1B, the accumulation of poliovirus proteins upon infection of Arf-Venus-expressing cell lines was the same as that in control HeLa cells. It should be noted that sometimes we observed additional weak GFP-positive bands on the Western blots upon analysis of Arf-Venus fusions (see, for example, Fig. 1B, Arf5 sample). Analysis of lysates from infected and noninfected cells did not reveal any differences (Fig. 1C), thereby excluding infection-specific modification of Arf-Venus fusions. It is likely that such bands correspond to posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation or acetylation of Arf molecules (38). We also analyzed the virus yield and found it the same in Arf-Venus-expressing cells and the original HeLa cell line (data not shown). Thus, cell lines expressing Arf-Venus constructs recapitulate normal Arf phenotypes and provide a convenient tool for studying the role of these small cellular GTPases in enterovirus infection.

Poliovirus infection induces the dynamic recruitment of multiple Arfs to replication organelles.

To monitor the pattern of Arf activation during the time course of poliovirus infection, cells expressing Arf-Venus fusions were infected with 50 PFU/cell of poliovirus type I Mahoney (so that all of the cells are infected) and fixed at 2, 4, and 6 h postinfection (p.i.). By 6 h the replication cycle of poliovirus in HeLa cells is complete. Activation of Arfs induces their association with membranes, and, to maximally preserve the Arf localization pattern, the cells were not processed for any additional staining after fixation.

In mock-infected cells, the distribution of Arf isoforms was similar at all time points. Arf1, -3, -4, and -5 were concentrated in the perinuclear area, reflecting their association with the ERGIC and the Golgi, and Arf6 was associated with the plasma membrane (Fig. 2, mock infection). Poliovirus infection induced dramatic changes in the distribution of all Arf isoforms, including Arf6. As early as 2 h p.i., Arf1, -3, and -5 were redistributed in a noticeable percentage of the cells (up to 20% for Arf3) in multiple dots, likely reflecting Golgi fragmentation known to occur early in enterovirus infection (39, 40) (Fig. 2, 2 h p.i.). Arf4 was mostly associated with perinuclear structures, possibly Golgi remnants. Arf6 was still almost exclusively associated with the plasma membrane in the infected cells, similar to control cells (Fig. 2, and 2 h p.i.).

FIG 2.

Recruitment of Arfs to the replication organelles in poliovirus-infected cells. HeLa cell lines expressing individual Arf-Venus fusions were mock infected or infected with poliovirus type I Mahoney at 50 PFU/cell and fixed at the indicated times postinfection. To maximally preserve the pattern of Arf recruitment, no other manipulations with cells were performed. For quantifications, several random fields with no fewer than 100 total cells were counted. The cellular phenotypes were defined as Arf1 to -4, mostly at the Golgi membrane (Arf6 was at the plasma membrane), Arfs mostly distributed at the cytoplasmic dots, and Arfs mostly recruited to the perinuclear rings of replication organelles (RO).

In the middle of the infectious cycle, at 4 h p.i., in the majority of Arf1-Venus-expressing cells (∼80%) the signal was found in bright perinuclear rings, characteristic of localization of poliovirus replication organelles, extensively described previously (reviewed in references 4–6), while Arf3, -4, and -5 signals were found in almost equal numbers of cells either in distinct punctae (∼60%, ∼30%, and ∼30%, respectively) or in perinuclear rings (∼42%, ∼60%, or ∼62%, respectively). Interestingly, a redistribution of Arf6-Venus signal from the plasma membrane to the perinuclear region was also observed in almost all of the cells (80%); however, the level of Arf6 signal on the replication organelles was relatively low at this time point, especially compared to the bright, highly concentrated signal of Arf1 (Fig. 2, 4 h p.i.).

By the end of the replication cycle, at 6 h p.i., all Arf isoforms in poliovirus-infected cells were found highly concentrated in perinuclear rings in 90 to 100% of cells (Fig. 2, and 6 h p.i.). It should be noted that starting from 4 h p.i., the confocal images demonstrate a much stronger signal of membrane-associated Arf1, -3, -5, and -6 in any section plane in infected than in mock-infected cells, reflecting a significantly higher level of Arf activation upon infection (Fig. 2).

Thus, during the poliovirus replication cycle, Arf1, -3, -4, -5, and -6 demonstrate distinct dynamics of recruitment to the replication organelles, suggesting that the biochemical properties of the replication membranes change during the time course of infection.

Diverse enteroviruses induce the same pattern of Arf activation.

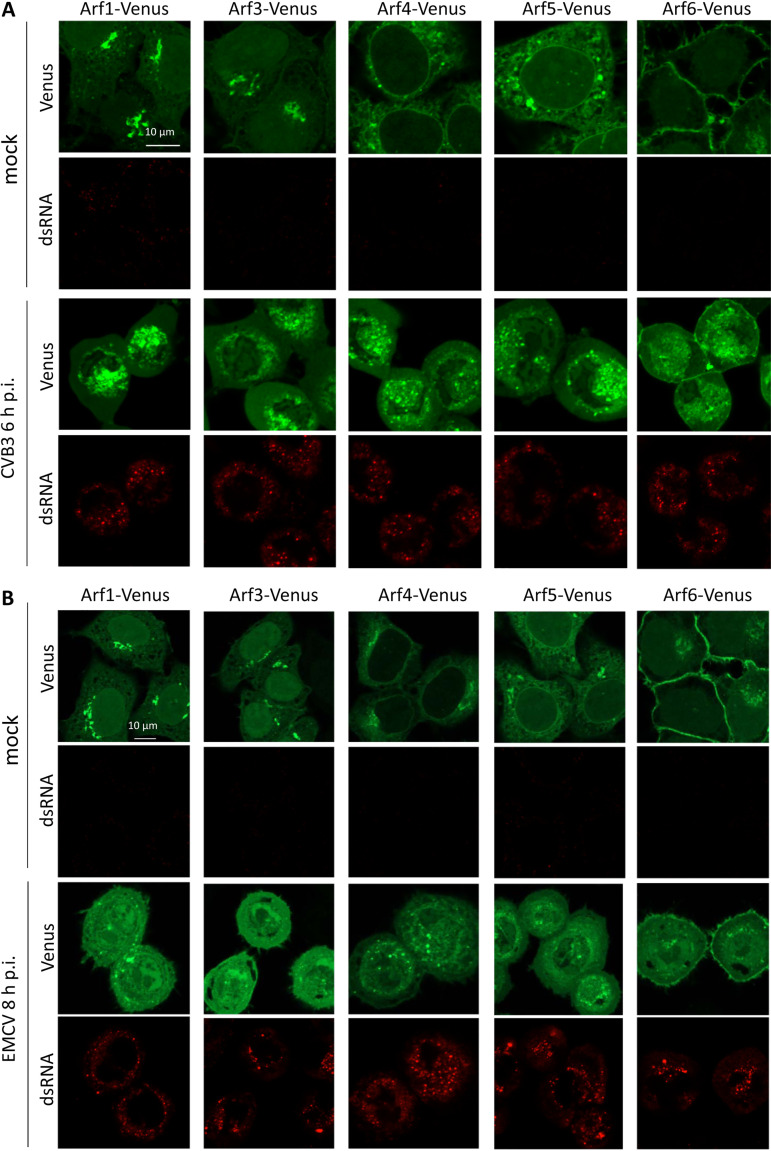

To see if the pattern of Arf recruitment to the replication organelles is virus specific, we infected cells expressing Arf-Venus fusions with coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3), an enterovirus distantly related to poliovirus. Poliovirus is classified within the enterovirus species C, while CVB3 belongs to the enterovirus species B in the Enterovirus genus of the Picornaviridae family (41). We also infected cells with encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV), a murine picornavirus of the Cardiovirus genus, which is known not to be sensitive to BFA and, thus, is unlikely to depend on Arf activation (42). CVB3 and EMCV replicate in HeLa cells with kinetics similar to that of poliovirus (the replication cycle is complete within 6 to 8 h).

Infection with CVB3 induced a pattern of Arf redistribution similar to that observed in poliovirus-infected cells, so that by the end of the replication cycle (6 h p.i.), all Arfs were found on the replication organelles (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

Recruitment of Arfs to the enterovirus but not cardiovirus replication organelles. HeLa cell lines expressing individual Arf-Venus fusions were mock infected or infected with 50 PFU/cell of coxsackievirus B3 (an enterovirus) (A) or encephalomyocarditis virus (a cardiovirus) (B) and fixed at 6 and 8 h p.i. The cells were counterstained for dsRNA, an intermediate product of replication of RNA viruses, to confirm the infection.

In contrast, in cells infected with EMCV, none of the Arfs was recruited to the replication organelles, even in cells with strong cytopathic effect, i.e., those at the end of the infectious cycle. Nevertheless, the effect of EMCV infection on Arf distribution was clearly visible. In infected cells, there were much less membrane-associated Arfs than in control cells, indicating that ArfGEF activity is likely severely inhibited during cardiovirus infection. In some cells, Arf1 and Arf4 were found in multiple membrane-associated dots (Fig. 3B and data not shown), but whether these dots represent the remnants of preexisting Arf-enriched structures, like the Golgi, or have an infection-specific significance requires further investigation.

Thus, the recruitment of multiple Arfs to the replication organelles is a shared feature of enterovirus, but not cardiovirus, infection.

Arf1 is the first to associate with functional replication organelles.

To directly compare the recruitment of different Arf isoforms to the replication organelles in the same cell, we developed cell lines coexpressing pairs of Arfs fused to either green or red fluorescent reporter proteins. As the red fluorescent reporter, we used FusionRed protein (FRP) that was specifically designed to be strictly monomeric (43), so that the residual propensity for oligomerization common to other red fluorescent reporter proteins does not interfere with Arf targeting. First, we verified that Arf1 tagged with FRP behaves the same as Venus-tagged Arf1 and monitored the colocalization of red and green signals in a HeLa cell line coexpressing Arf1-Venus and Arf1-FRP. As shown in Fig. 4, in both control and infected cells, the red and the green Arf1 signals were perfectly colocalized, confirming that the Arf1-FRP construct recapitulates the same Arf1 behavior.

FIG 4.

Arf1 fusions with red and green fluorescent proteins recapitulate the same Arf1 behavior. HeLa cells coexpressing Arf1-Venus (green) and Arf1-FRP (red) fusions were mock infected or infected with poliovirus type I Mahoney at 50 PFU/cell, and the cells were fixed at the indicated times postinfection. Nuclear staining was performed with a cell-permeable dye, Hoechst 33342, in live cells 30 min before fixation. To maximally preserve the pattern of Arf recruitment, no other manipulations with cells were performed.

We then analyzed the recruitment of different Arfs relative to Arf1 by coexpressing Arf1-FRP with other Arf isoforms fused to Venus. The cells were infected (or mock infected) with poliovirus type I Mahoney at a multiplicity of 50 PFU/cell, and the subcellular localization of both Arfs was analyzed at 3 h p.i. (early-middle time of the infectious cycle). At this multiplicity of infection at 3 h p.i., viral antigens are readily detectable, while the cells still maintain overall normal morphology. As shown in Fig. 5, in mock-infected cells, the Arf1 signal showed extensive colocalization in the Golgi area with all the Arfs except the plasma membrane-localized Arf6. However, in infected cells, the recruitment of Arf1 to the perinuclear replication organelles preceded the recruitment of other Arf isoforms. At later time points (4 to 6 h p.i.), all Arfs were extensively colocalized with Arf1 on the replication organelles (data not shown).

FIG 5.

Arf1 is the first to be recruited to the replication organelles. (A) HeLa cells coexpressing pairs of Arf1-FRP (red) with other Arf-Venus (green) fusions were infected with poliovirus type I Mahoney at 50 PFU/cell and fixed at 3 h p.i. To maximally preserve the pattern of Arf recruitment, no other manipulations with cells were performed. (B) HeLa cells coexpressing pairs of Arf1-FRP (red) with other Arf-Venus (green) fusions were infected with poliovirus type I Mahoney at 50 PFU/cell and fixed at 4 h p.i. The cells were stained with antibody A12 that recognizes only mature poliovirus capsids (35), and early in infection denotes the localization of the active replication organelles, since the assembly of poliovirus virions is intimately linked to active RNA replication (52). Nuclear DNA was stained by Hoechst 33342 (blue).

To directly identify the Arf isoforms that associate early in infection with the replication organelles, we took advantage of the fact that the assembly of poliovirus virions is tightly coupled to RNA replication (44). At 3 h p.i., the accumulation of the progeny virus first becomes apparent; thus, the virion signal should be localized at least close to the functional replication complexes. Cells expressing individual Arf-Venus fusions were infected with poliovirus at a multiplicity of infection of 50, fixed at 3 h p.i., and subsequently stained with a monoclonal antibody A12 that recognizes only the fully mature virions (45). We observed that only Arf1-Venus but not the other Arfs strongly colocalized with the virion signal (Fig. 5B).

Thus, Arf1 appears to be the first to associate with the replication organelles, followed by other Arf isoforms, which suggests that the composition of the proteins associated with the replication organelles are significantly different at different stages of the infectious cycle.

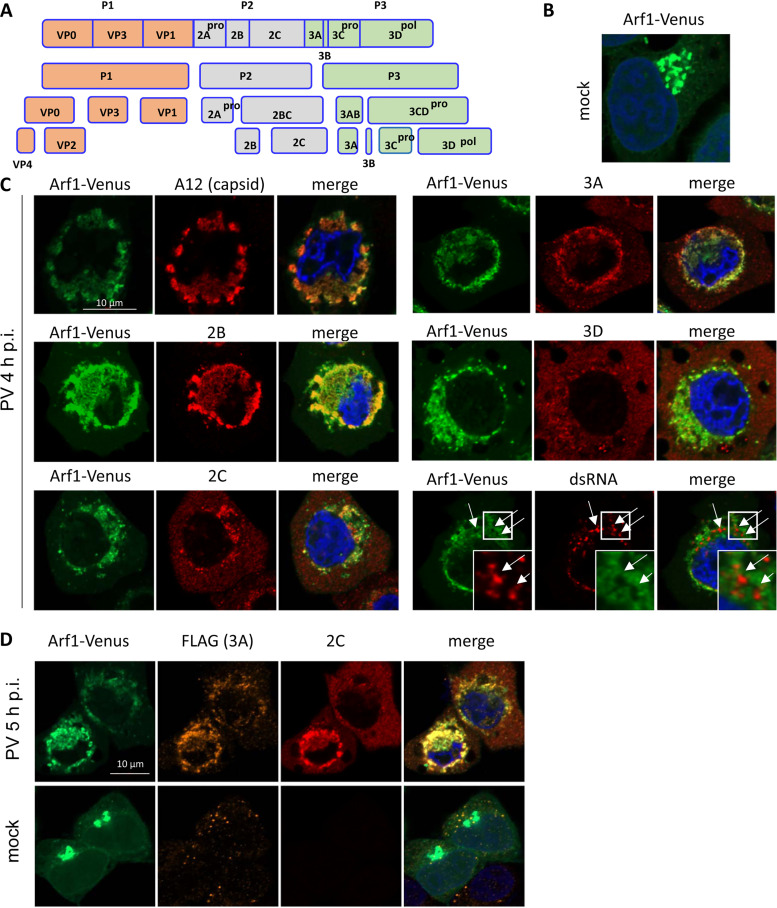

Viral antigens show distinct patterns of association with Arf-enriched membranes.

Enteroviral proteins are expressed as a single polyprotein, which is co- and posttranslationally processed by three viral proteases: 2A, 3C, and 3CD (Fig. 6A). It is generally assumed that the synthesis of the polyprotein results in a similar spatiotemporal distribution of viral antigens, yet it has not been explicitly addressed. Thus, we analyzed the localization of viral antigens relative to Arf1-enriched membranes. Cells expressing Arf1-Venus fusion were infected with 50 PFU/cell of poliovirus type I Mahoney and fixed at 4 h p.i. in the middle of the infectious cycle. The cells were stained with antibodies to dsRNA, an intermediate product of the viral RNA replication process, or with antibodies recognizing the mature capsid (A12) or the nonstructural proteins 2B, 2C, 3A, or 3D. Because of the polyprotein synthesis and processing scheme, the antibodies recognize the mature proteins as well as all the intermediate cleavage products containing the corresponding antigens (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

Poliovirus antigens differentially associate with Arf-enriched membranes. (A) Scheme of the processing of poliovirus polyprotein. (B) Mock-infected HeLa cells expressing Arf1-Venus fusion. (C) HeLa cells expressing Arf1-Venus fusion were infected with poliovirus type I Mahoney at 50 PFU/cell, fixed at 4 h p.i., and stained with antibodies recognizing dsRNA, mature poliovirus capsid (A12) (35), or the antigens in the viral nonstructural protein 2B, 3A, 2C, or 3D. (D) HeLa cells expressing Arf1-Venus fusion were infected with 50 PFU/cell of a poliovirus type I Mahoney mutant with FLAG-Y inserted in the nonstructural protein 3A (30). The cells were stained with anti-FLAG and anti-2C antibodies simultaneously. Nuclear DNA was stained by Hoechst 33342 (blue).

At 4 h p.i., Arf1 is strongly associated with the perinuclear rings of replication organelles (compare the distribution of Arf1-Venus in mock-infected cells [Fig. 6B] with that in the infected cells in Fig. 6C). We confirmed a very strong colocalization of the signal of the mature virions with Arf1-enriched membranes, similar to that observed at 3 h p.i. (Fig. 5B), indicating that at least at the early-middle stage of infection, the major part of the progeny virus is still tightly associated with the membranes of the replication organelles and is not significantly exported from the cell via possible nonlytic pathways (Fig. 6C).

The nonstructural proteins exhibited qualitatively distinct types of behavior. While we observed the strongest Arf1-Venus colocalization with the 2B antigen, the signal for the membrane-targeted proteins 2C and 3A was less colocalized with Arf1-Venus. Furthermore, the signal for the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase 3D colocalized poorly, with most of the protein found outside the areas enriched in Arfs (Fig. 6C). The level of the colocalization of the viral antigens with Arf1-Venus signal varied in different cells and was, in general, higher in cells expressing more of the viral proteins, i.e., those further in the replication cycle progression.

Surprisingly, dsRNA, while localized in the general Arf1-enriched region, was often clearly separated from the Arf1 signal, which appeared to encircle it (Fig. 6C, dsRNA panel, arrows). This phenomenon was observed in all cells analyzed, arguing that exclusion of dsRNA from Arf-enriched regions is an important feature of the fine organization of the replication organelles.

We did not observe any specific associations of the viral antigens with other Arfs early in the infection cycle, and when, at the middle-late stage of infection, other Arfs were massively recruited to the replication organelles, their colocalization with viral antigens was similar to that of Arf1 (data not shown).

To confirm that in the same cell viral nonstructural membrane-targeted proteins could have a significantly different localization relative to Arf-enriched membranes of replication organelles, we infected Arf1-Venus-expressing cells with a poliovirus with a modified FLAG insert (FLAG-Y) in the protein 3A. This virus replicates with almost wild-type kinetics (46). The simultaneous staining of cells infected with this virus with anti-FLAG and anti-2C antibodies at 5 h p.i. demonstrated that both viral antigens have distinct localizations relative to Arf1, with a substantial amount of 2C still outside the Arf-enriched area (Fig. 6D).

These data demonstrate that the full complement of viral proteins is assembled on the Arf1-enriched replication organelles at early-middle stages of replication. However, at least some of the nonstructural proteins, including the membrane-targeted proteins 2C and 3A, could have an extended localization outside the replication complexes. This suggests the existence of replication-independent functions of these proteins.

Only Arf3 requires constant GEF activity to remain associated with the replication organelles.

Under normal conditions, cellular Arfs constantly cycle through activated, GTP-bound and inactivated, GDP-bound states. To determine whether Arfs recruited to the viral replication organelles still undergo cycles of GDP/GTP exchange, we infected cells expressing Arf-Venus constructs with poliovirus type I Mahoney at 50 PFU/cell and incubated them for 5 h, so that the Arf-enriched replication organelles are well developed. At this point, the medium was supplemented with BFA and the cells were monitored to track the behavior of the Arfs (Fig. 7A). If the GTP hydrolysis arm of the Arf cycle is still functional, Arfs whose activation depends on BFA-sensitive GEFs are expected to be released from the membranes (Fig. 7B).

FIG 7.

Only Arf3 undergoes active cycling through GTP- and GDP-bound forms on the replication organelles. (A) Scheme of the experiment with the addition of brefeldin A (BFA), an inhibitor of GBF1, to the infected cells upon the formation of well-developed replication organelles. (B) Scheme of Arf cycling through membrane-bound GTP- and cytoplasmic GDP-bound forms. The guanidine nucleotide activating factors (GEFs) may be inhibited by BFA, while the GTPase-activating proteins (GAP) are still functional. (C) HeLa cells expressing individual Arf-Venus fusions were mock infected or infected with poliovirus type I Mahoney at 50 PFU/well, incubated for 5 h, and then incubated for 1 h in the presence of 1 μg/ml of BFA and fixed. No other manipulations with cells were performed to maximally preserve the pattern of Arf recruitment.

In mock-infected cells treated with BFA, Arf1 and -3 lost their association with the Golgi membranes. Arf4 and -5 were also mostly released from the membranes, although some residual association, likely with ERGIC/Golgi remnants, could be seen (Fig. 7C, mock infection). Arf6, which is activated by a BFA-insensitive GEF called ARNO, remained associated with the plasma membrane, as expected (Fig. 7C, mock infection). In contrast, in infected cells, only Arf3 was released to the cytoplasm in the presence of BFA, while the association of Arf1, -4, -5, and -6 with the replication membranes was not affected by the inhibitor (Fig. 7C, PV).

Thus, contrary to the rapid activation-deactivation cycle in noninfected cells, once recruited to the replication membranes, all Arfs, except Arf3, likely remain for a prolonged time in the GTP-bound state.

Arf1 depletion strongly increases the sensitivity of viral replication to GBF1 inhibition.

The results obtained here and previously reported data suggest that activated Arfs constitute an important component of the specific biochemical environment of the enterovirus replication organelles, yet their mechanistic role in the replication process remains enigmatic. Moreover, investigations of the function played by the distinct Arfs in enterovirus replication reported conflicting results. Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated depletion or CRISPR/CAS-mediated knockout of individual or pairwise combinations of Arfs did not demonstrate a significant effect on the replication of coxsackievirus B3 or B4, but the simultaneous depletion of both Arf1 and Arf3 was reported to inhibit replication of enterovirus 71 (19, 22, 23).

We hypothesized that since enterovirus replication depends on the activity of GBF1 and is inhibited by BFA (18, 19), the depletion of the Arf isoform(s) that is important for the replication process will increase the sensitivity of infection to BFA. Since reliable Arf isoform-specific antibodies are not readily available, we first tested the efficacy and specificity of the previously reported Arf isoform-specific siRNAs (47, 48) using our cell lines expressing individual Arf-Venus constructs. Each Arf isoform was individually targeted by two different siRNAs. The loss of the corresponding fluorescent signal and the Western blot performed with anti-GFP antibodies confirmed the high specificity of the siRNAs, with the maximum depletion level achieved at day 3 after siRNA transfection (Fig. 8A and data not shown). We observed that treatment with one siRNA from the pair was sometimes more toxic to the cells, even though they showed similar depletion efficiency, and the siRNAs with the least toxicity were always chosen for subsequent experiments.

FIG 8.

Arf1 significantly increases the sensitivity of polio replication to GBF1 inhibition. (A) Specificity and efficacy of the Arf isoform-targeting siRNAs. HeLa cell lines expressing individual Arf-Venus fusions were transfected with isoform-specific siRNAs (e.g., 1A corresponds to anti-Arf1 siRNA) or scrambled siRNA control (C). The cells were lysed on the third day after siRNA transfection and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-GFP antibodies that recognize Arf-Venus fusions. The samples reflecting the effect of a specific siRNA on a cognate cell line (e.g., cells expressing Arf1-Venus treated with anti-Arf1 or control siRNAs) are highlighted. Actin is shown as a loading control. The siRNAs shown are those taken for further replication assay. (B) HeLa cells were treated with Arf isoform-specific siRNAs (or scrambled siRNA; siC) and, on the third day after siRNA transfection, were transfected with a poliovirus replicon RNA coding for a Renilla luciferase gene. (Left) The cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of BFA, and the Renilla signal was monitored in live cells every hour for 18 h after replicon RNA transfection (kinetic curves). (Middle) The total replication signal was calculated as the area under the curve, and normalization was performed for each sample for the replication signal in the absence of the inhibitor. (Right) A parallel sample of siRNA-transfected cells was used for cell viability assay. P values are indicated: ****, P < 0.0001; ***, P < 0.001. RLU, relative light units.

HeLa cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting a specific Arf isoform, and a quantitative polio replicon replication assay was performed on the third day after siRNA transfection, similar to the previously described approach (21, 49). The replication assay was performed in the absence of BFA or in the presence of 125 and 500 ng/ml of the inhibitor, concentrations that only partially (down to ∼40 to 50% and ∼10% to 20% of the control, respectively) inhibited the replication in cells treated with scrambled siRNA control (Fig. 8B).

In agreement with the previously reported data (19, 22, 23), replication in cells depleted of a single specific Arf in the absence of BFA generally proceeded similarly to that in control cells, except for Arf3, whose depletion was the most toxic to cells. However, the relative replication efficiencies of the polio replicon in Arf3-depleted cells were the same as those in control cells throughout the range of BFA concentrations (Fig. 8B). Similarly, in the cells depleted of Arf5 the replication was indistinguishable from that in control cells either in the presence or in the absence of BFA. The depletion of Arf4 repeatedly demonstrated a noticeable stimulatory effect on replication, regardless of the presence of the inhibitor. The most dramatic effect on BFA sensitivity was observed in cells depleted of Arf1. In the presence of even the smaller concentration of BFA, the replication was virtually completely inhibited, even though it was still effective in control cells (Fig. 8B). Surprisingly, replication of the polio replicon in cells with knockdown Arf6 expression was slightly but statistically significantly inhibited in the presence of BFA.

Collectively, these data support the conclusion that Arf1 is the isoform critically involved in the BFA-sensitive GBF1-controlled complex of reactions supporting enterovirus replication. In addition, our results suggest that Arf6 also specifically contributes to the development and functioning of the replication organelles.

DISCUSSION

The development of replication organelles is an essential step in the enterovirus replication cycle. The viral proteins reorganize the cellular membrane metabolism so that the cell develops novel membranous structures with unique lipid and protein composition harboring the viral replication complexes. The replication organelles are enriched in certain cellular membrane trafficking and lipid metabolism proteins whose activity is required to support the effective functioning of the viral replication machinery. However, the mechanistic details of how the cellular factors contribute to the viral RNA replication are still poorly understood (reviewed in reference 4–6 and 50–52).

A cellular protein, GBF1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for small cellular Arf GTPases (ArfGEF), is recruited to the replication organelles through interaction with the enterovirus protein 3A, and it is well established that its ArfGEF activity is essential for viral replication (18, 19, 21, 53–55). However, it is much less clear which Arf isoforms activated by GBF1 are required to support the replication and how these GTPases are involved in the replication process.

In this paper, we developed cell lines expressing fluorescent fusions of all five human Arfs, which allowed us to investigate their individual behavior in enterovirus-infected cells. We report that early in infection, only Arf1 is massively recruited to the replication organelles, followed by all other Arfs during the middle and late stages of infection. Surprisingly, even Arf6, which in noninfected cells is almost exclusively localized on the plasma membrane and is not normally activated by GBF1, was significantly enriched on the replication organelles by the end of the infectious cycle. Importantly, the similar recruitment of all Arfs to the replication organelles was observed upon infection of such distantly related enteroviruses as poliovirus and coxsackievirus B3, suggesting that it represents a commonality of requirements for enterovirus replication.

Sequential recruitment of distinct Arfs to the replication organelles creates unique biochemical environments.

In noninfected cells, different Arfs are activated and thereby localize to specific cellular sites, and the tight control of Arf activation is important for maintaining the dynamic homeostasis of the cellular membrane metabolism (reviewed in reference 25). Activated Arfs interact with multiple effector proteins and recruit them to the membranes. Among Arf effectors are proteins involved in lipid transfer, synthesis, and modifications, such as ceramide transfer protein (CERT), phosphatidylinositol 4 and phosphatidylinositol 4-5 kinases, phospholipase D, and components facilitating and regulating membrane traffic (reviewed in references 56 and 57). Thus, the simultaneous association of all Arf isoforms with the replication organelles likely creates a unique combination of Arf effectors that generate a biochemical environment never found on organelles in noninfected cells. However, the differences in the kinetics of recruitment of the distinct Arfs also imply the dynamic changes of the Arf-controlled biochemical environment of the replication organelles during the time course of infection. This may guide the transition of the infectious cycle from the early stage, when viral proteins and RNAs are accumulated, to the later phases associated with increasing virion assembly, maturation, and release.

The details of recruitment of Arf6 to the replication organelles require further investigation. Arf6 is the most structurally divergent member of Arf GTPases, it is normally activated by a BFA-insensitive ArfGEF ARNO, and it is predominantly associated with the plasma membrane. However, Arf6 is also implicated in endocytic traffic (reviewed in reference 58), and it is possible that the relocation of Arf6 to the replication membranes is linked to the redirection of endocytic traffic required for the enrichment of the replication membranes in cholesterol from the plasma membrane depot (59). The possible involvement of Arf6 also implies that ARNO or other members of the cytohesin family of ArfGEFs (reviewed in reference 25) may be other host factors important for the development of infection.

In noninfected cells, Arfs undergo rapid cycling between membrane-associated GTP-bound and cytoplasmic GDP-bound forms. However, once recruited to the replication membranes, all Arfs except Arf3 became insensitive to the inhibition of ArfGEF activity, indicating that they remain for a prolonged time in a GTP-bound form. This again underscores that the metabolism of Arf-associated reactions is very different between infected and noninfected cells. Whether the distinctive behavior of Arf3 has a particular significance for infection requires further investigation.

Viral antigens show different association with Arf-containing membranes, and dsRNA is excluded from Arf-enriched regions.

The detailed analysis of the localization of viral antigens revealed that nonstructural protein 2B and the fully assembled virions show the strongest colocalization with Arf-enriched membranes. It should be stressed that since the poliovirus proteins are expressed upon sequential processing of the polyprotein precursor, the 2B signal may indicate the localization of the fully processed 2B, a stable precursor, 2BC, or any other higher-level precursor containing the 2B antigen. A compelling body of evidence indicates that picornavirus 2B is a viroporin that assembles in oligomers forming pores spanning the membrane bilayer, thus permitting ion flux through the membranes (60–65). Enterovirus replication organelles represent massive membranous agglomerates (66, 67), and it is likely that 2B pores facilitate the supply of the viral replication complexes buried inside these membranes with nucleotides and other water-soluble molecules and the release of the newly synthesized RNA into the cytoplasm. Functionally analogous pores have been described in other positive-strand RNA virus systems. Oligomerized nodavirus replication protein A forms a channel in the narrow neck connecting the membrane invagination harboring the replication machinery with the cytoplasm (68, 69). Recently, coronavirus nonstructural protein 3 (ns3)-formed pores, allowing communication between the inner cavity of the double membrane vesicles containing coronavirus replication complexes and the cytoplasm, have been identified (70). Poliovirus 2B and 2BC were previously found to have a strong Golgi tropism when expressed individually (71–73). Since Golgi membranes are enriched in activated Arfs and our results demonstrate a very strong colocalization of 2B and Arf signals, it is tempting to speculate that 2B could be an Arf effector; thus, Arfs may be necessary for the proper formation and/or stabilization of 2B pores necessary for the functioning of the replication complexes.

The nonstructural proteins 2C and 3A with known membrane-targeting domains showed less colocalization with Arfs, especially at the early stages of infection. Only a minimal amount of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase 3D was colocalizing with Arfs on replication membranes, with most of the protein found in the cytoplasm without apparent association with any membranous structures. This is consistent with the earlier reports of a significant amount of 3D in the soluble cytoplasmic fractions of infected cells (74, 75). Such extensive localization of the viral nonstructural proteins outside the replication organelles suggests that they have important replication-independent functions that remain virtually unexplored. One can envision that viruses must allocate significant resources to overcome the host antiviral responses. Indeed, different mechanisms have been implicated in the prevention of activation and/or suppression of the cellular antiviral response upon enterovirus infection, such as general inhibition of cellular transcription and translation, protection of the dsRNA replication intermediates by the membranes of the replication organelles, inhibition of cellular secretion, and targeted cleavage of the cellular sensors of infection and signaling molecules by viral proteases (76–86). However, it is likely that early in infection the membranous scaffold of the replication organelles is not well developed to effectively hide the dsRNA, and the amount of viral proteases is insufficient to cause significant degradation of the signaling molecules, let alone the global inhibition of translation and transcription. At this stage, the nonstructural proteins localized on the membranes outside the replication organelles may interfere with the cellular signaling cascades, which often require the formation of membrane-localized signal transduction platforms (87). Interestingly, our data demonstrate the most diverse distribution of viral nonstructural proteins outside the replication organelles at early stages of infection.

Interestingly, we observed that the signal for the dsRNA, an intermediate of the RNA replication process, was localized adjacent to the Arf-enriched areas but was often strictly separated in distinct Arf-free loci. It cannot be said with certainty if the signal of an anti-dsRNA antibody reflects the location of active replication complexes or accumulating long dsRNA dead-end replication by-products, or possibly both. The active replication complexes likely contain relatively short dsRNA regions because of the active displacement of the nascent RNA molecules and the presence of the viral and cellular proteins preventing the annealing of complementary RNA regions (88, 89). Irrespective of the mechanism, such sequestration of dsRNAs within biochemically distinct membranous domains may be functionally analogous to the confinement of the dsRNA within membrane invaginations and double-membrane vesicles observed in other (+)RNA virus systems (90–96). This may explain the importance of the proper development of the membranous scaffold of the enterovirus replication organelles in evading the innate immune response (85). Collectively, our data indicate that the replication organelles are not homogenous membrane agglomerates but likely have compositionally and structurally distinct microdomains, most likely reflecting the different requirements during distinct stages of the viral life cycle. Further studies with higher-resolution microscopy techniques are required to elucidate the fine organization of the replication organelles.

Arf1 and Arf6 appear to be the most important Arfs for the development of enterovirus infection.

The published data regarding the contribution of individual Arfs to the enterovirus replication process are controversial. The inhibition of enterovirus infection by compounds blocking the ArfGEF activity of GBF1 could be relieved only by overexpression of GBF1 itself but not by any individual Arf in either the wild-type or the constitutively active form (18, 19). Moreover, the depletion or knockdown of expression of individual Arfs, or pairs thereof, was tolerated by diverse enteroviruses remarkably well, suggesting a higher level of Arf redundancy in the viral replication than in the cellular metabolism (19, 22). Indeed, we also observed that upon siRNA-mediated depletion of individual Arfs, poliovirus replicon replication proceeded similarly to that in the control cells, except for the cells with knockdown of Arf3. However, Arf3 depletion was noticeably toxic to cells, which can at least partially explain the only report of a significant decrease in the replication of an enterovirus after the simultaneous depletion of Arf1 and Arf3 (23).

Here, we investigated if depletion of individual Arfs changes the sensitivity of infection to inhibition of the ArfGEF activity of GBF1. Indeed, we observed that knockdown of Arf1 and, to a lesser extent, Arf6 significantly decreased replicon replication in the presence of an inhibitor of GBF1 at concentrations that only partially suppressed the replication in control cells. Curiously, depletion of Arf4 was somewhat stimulatory for viral replication both in the absence and in the presence of BFA, suggesting that Arf4 may be competing with another GBF1-activated Arf(s) that promotes replication. Together with the observations that Arf1 was the first Arf associated with the replication organelles at the beginning of infection, our data suggest that the GBF1-Arf1 axis is the most important contributor to the development and/or functioning of the replication organelles.

Overall, our work elucidated important details of the dynamic changes in the GBF1-dependent activation of small Arf GTPases during enterovirus infection and documented that unique Arf-mediated alterations in cellular membrane metabolism occur at distinct stages of viral replication. Our work provides foundational knowledge that could be exploited in the development of therapeutics targeting only infected cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

HeLa cells were maintained in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 mM sodium pyruvate and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Retrovirus packaging cell line GP2-293 (TaKaRa) was maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and nonessential amino acids. Poliovirus type I Mahoney, poliovirus type I with FLAG-Y insert in the 3A protein (46), coxsackievirus B3 Nancy, and encephalomyocarditis virus E9 variant with a shortened poly(C) tract (97) were propagated in HeLa cells, and their titers were determined by plaque assays. For infection, HeLa cells were seeded in either 12-well plates (with or without a coverslip depending on the future analysis) or 8-well μ-slides (Ibidi) with a glass bottom. For adsorption, the cells were incubated with the required amount of the virus resuspended in DMEM for 30 min at room temperature and then at 37°C in DMEM with 10% FBS for the indicated times postinfection (h p.i.).

Plasmids.

Plasmid pXpA-RenR, coding for a poliovirus replicon with the Renilla luciferase gene replacing the capsid P1 region, was described in reference 98. Retroviral vector pLNCX2 was purchased from TaKaRa. Plasmids pArf1-Venus, pArf3-Venus, pArf4-Venus, pArf5-Venus, and pArf6-Venus were a gift from Catherine Jackson (Université Paris Diderot-Paris). For the construction of retroviral vectors, fragments containing corresponding Arf-Venus open reading frames (ORFs) were cloned under the control of a cytomegalovirus promoter into XhoI and NotI restriction sites of the pLNCX2 vector. For the generation of the pLNCX2-Arf1-FRP, expressing Arf1 fused to a monomeric red fluorescent protein, FusionRed (43), an Arf1-FRP fragment maintaining the same linkers as the Arf1-Venus construct was synthesized by GeneArt (Thermo Fisher). Cloning details are available upon request.

Antibodies, siRNAs, and other reagents.

Anti-poliovirus mouse monoclonal anti-2B, -2C, and -3A and rabbit polyclonal anti-3D antibodies were described in references 99 and 20, respectively. Human monoclonal antibody A12, recognizing a conformational epitope present only in mature poliovirus capsids, was described in reference 45. Rabbit monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody was from Cell Signaling. Mouse monoclonal anti-GM130 and anti-ERGIC53 antibodies were from BD Bioscience and Santa Cruz, respectively. Rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP antibodies were from Abcam. Wheat germ agglutinin, Alexa Fluor 594 conjugate, and secondary antibody conjugates with Alexa fluorescent dyes were from Molecular Probes (Thermo Fisher). Scrambled siRNA mix siControl1 was from Ambion. siRNAs against human Arfs were ordered from Dharmacon according to the following sequences: Arf1A, ACCGUGGAGUACAAGAACA; Arf1B, UGACAGAGAGCGUGUGAAC; Arf3A, UGUGGAGACAGUGGAGUAU; Arf3B, ACAGGAUCUGCCUAAUGCU; Arf4A, UCUGGUAGAUGAAUUGAGA; Arf4B, AGAUAGCAACGAUCGUGAA; Arf5A, UCUGCUGAUGAACUCCAGA; Arf5B, ACCAUAGGCUUCAAUGUAGA; Arf6A, CGGCAUUACUACACUGGGA; and Arf6B, UCACAUGGUUAACCUCUAA, published in references 47 (Arf1 to -5) and 48 (Arf6). siRNA transfection was performed using Dharmafect1 transfection reagent (Dharmacon) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Brefeldin A was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. EnduRen cell-permeable substrate for Renilla luciferase was from Promega. DNA and RNA transfection reagents Trans-it 2020 and Trans-it mRNA, respectively, were from Mirus. The cell viability luciferase-based assay kit was from Promega.

Generation of stable HeLa cell lines expressing Arf fusions.

Retroviral virions were generated by transfecting the packaging cell line GP2-293 according to the manufacturer’s directions. Briefly, GP2-293 cells seeded into a 6-well plate were cotransfected with pLNCX2 vectors expressing Arf fusions and the plasmid coding for the vesicular stomatitis virus envelope glycoprotein. Eighteen hours after transfection, the medium was replaced with a fresh complete growth medium, and cells were kept in the incubator overnight. The infectious virions were collected in the culture supernatant 48 h after the start of transfection. HeLa cells seeded into a 6-well plate were transduced with the freshly harvested supernatant supplemented with 10 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich). The plate was centrifuged at 1,200 × g for 1 h at 32°C and then incubated at 37°C for 18 h. The next day, the medium was replaced with fresh complete growth medium, and cells were kept in the incubator overnight. Forty-eight hours after the start of transduction, cells were transferred into a T-25 flask, and the drug-resistant colonies were selected with 300 μg/ml G418 (Thermo Scientific) for 10 days. The resistant colonies were pooled and the stable cell lines were maintained in the complete growth medium supplemented with 300 μg/ml G418. Cells coexpressing green and red Arf fusions were generated similarly, but the original HeLa culture was transduced by a mixture of retroviral vectors coding for the corresponding Arf fusions, and after the G418 selection the double-positive cells were sorted using BD FACSAria II cell sorter. This method generated cultures with 10% to 20% of cells coexpressing both green and red Arf fusions.

Polio replicon assay.

The polio replicon assay was performed essentially as described in reference 100. Briefly, HeLa cells grown in a 96-well plate were transfected with a purified RNA coding for a polio replicon with the Renilla luciferase gene substituting for the capsid coding region. The cells were incubated in the growth medium supplemented with 5 μM EnduRen cell-permeable Renilla luciferase substrate in the heated chamber of a multiwell plate reader (ID3; Molecular Devices) at 37°C, and the Renilla signal was measured in live cells every hour for 18 h after replicon RNA transfection. The signal from at least 12 wells was averaged for each sample for each time point. The total replication signal was calculated as the area under the curve for the replication kinetics signal.

Microscopy.

Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for antibody staining. The cells were incubated sequentially for 1 h in primary and secondary antibody solutions in PBS containing 3% ECL Advance blocking reagent (GE Healthcare) with 3× wash in PBS before and after each antibody incubation. Confocal images were taken with either Zeiss LSM 510 or Zeiss LSM 800 microscope systems or a PerkinElmer Ultraview ERS 6FE spinning disk confocal attached to a Nikon TE 2000-U microscope, while nonconfocal images were taken with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope. For image analysis, several random fields with at least 100 total cells were analyzed.

Data processing and analysis.

Digital images were processed with microscope operating software Zen (Zeiss) or Volocity 6.2 (PerkinElmer) and Adobe Photoshop. All images belonging to one experiment were processed the same way, and the adjustments were applied evenly to the whole image area. Statistical calculations were performed using the GraphPad Prism software package, all calculations are presented as mean values and standard deviation bars. Data comparison for statistical significance was performed using the two-tailed unpaired t test.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant R01AI125561 to G.A.B. and E.S. and NIH grant R01 GM122802 to E.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reed Z, Cardosa MJ. 2016. Status of research and development of vaccines for enterovirus 71. Vaccine 34:2967–2970. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.02.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melnick JL. 1996. Current status of poliovirus infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 9:293. doi: 10.1128/CMR.9.3.293-300.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer L, Lyoo H, van der Schaar HM, Strating JRPM, van Kuppeveld FJM. 2017. Direct-acting antivirals and host-targeting strategies to combat enterovirus infections. Curr Opin Virol 24:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belov GA, Sztul E. 2014. Rewiring of cellular membrane homeostasis by picornaviruses. J Virol 88:9478–9489. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00922-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson WT. 2014. Poliovirus-induced changes in cellular membranes throughout infection. Curr Opin Virol 9:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strating JRPM, van Kuppeveld FJM. 2017. Viral rewiring of cellular lipid metabolism to create membranous replication compartments. Curr Opin Cell Biol 47:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manolea F, Claude A, Chun J, Rosas J, Melancon P. 2008. Distinct functions for Arf guanine nucleotide exchange factors at the Golgi complex: GBF1 and BIGs are required for assembly and maintenance of the Golgi stack and trans-Golgi network, respectively. Mol Biol Cell 19:523–535. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e07-04-0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saenz JB, Sun WJ, Chang JW, Li JM, Bursulaya B, Gray NS, Haslam DB. 2009. Golgicide A reveals essential roles for GBF1 in Golgi assembly and function. Nat Chem Biol 5:157–165. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawamoto K, Yoshida Y, Tamaki H, Torii S, Shinotsuka C, Yamashina S, Nakayama K. 2002. GBF1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for ADP-ribosylation factors, is localized to the cis-golgi and involved in membrane association of the COPI coat. Traffic 3:483–495. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouvet S, Golinelli-Cohen MP, Contremoulins V, Jackson CL. 2013. Targeting of the Arf-GEF GBF1 to lipid droplets and Golgi membranes. J Cell Sci 126:4794–4805. doi: 10.1242/jcs.134254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takashima K, Saitoh A, Hirose S, Nakai W, Kondo Y, Takasu Y, Kakeya H, Shin HW, Nakayama K. 2011. GBF1-Arf-COPI-ArfGAP-mediated Golgi-to-ER transport involved in regulation of lipid homeostasis. Cell Struct Funct 36:223–235. doi: 10.1247/csf.11035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowery J, Szul T, Styers M, Holloway Z, Oorschot V, Klumperman J, Sztul E. 2013. The Sec7 guanine nucleotide exchange factor GBF1 regulates membrane recruitment of BIG1 and BIG2 guanine nucleotide exchange factors to the trans-Golgi network (TGN). J Biol Chem 288:11532–11545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.438481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peyroche A, Antonny B, Robineau S, Acker J, Cherfils J, Jackson CL. 1999. Brefeldin A acts to stabilize an abortive ARF-GDP-Sec7 domain protein complex: involvement of specific residues of the Sec7 domain. Mol Cell 3:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80455-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mossessova E, Gulbis JM, Goldberg J. 1998. Structure of the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Sec7 domain of human Arno and analysis of the interaction with ARF GTPase. Cell 92:415–423. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80933-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farhat R, Ankavay M, Lebsir N, Gouttenoire J, Jackson CL, Wychowski C, Moradpour D, Dubuisson J, Rouille Y, Cocquerel L. 2018. Identification of GBF1 as a cellular factor required for hepatitis E virus RNA replication. Cell Microbiol 20:e12804. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verheije MH, Raaben M, Mari M, Lintelo EGT, Reggiori F, van Kuppeveld FJM, Rottier PJM, de Haan CAM. 2008. Mouse hepatitis coronavirus RNA replication depends on GBF1-mediated ARF1 activation. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000088. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goueslain L, Alsaleh K, Horellou P, Roingeard P, Descamps V, Duverlie G, Ciczora Y, Wychowski C, Dubuisson J, Rouille Y. 2010. Identification of GBF1 as a cellular factor required for hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J Virol 84:773–787. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01190-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belov GA, Feng Q, Nikovics K, Jackson CL, Ehrenfeld E. 2008. A critical role of a cellular membrane traffic protein in poliovirus RNA replication. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000216. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanke KHW, van der Schaar HM, Belov GA, Feng Q, Duijsings D, Jackson CL, Ehrenfeld E, van Kuppeveld FJM. 2009. GBF1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Arf, is crucial for coxsackievirus B3 RNA replication. J Virol 83:11940–11949. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01244-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belov GA, Kovtunovych G, Jackson CL, Ehrenfeld E. 2010. Poliovirus replication requires the N-terminus but not the catalytic Sec7 domain of ArfGEF GBF1. Cell Microbiol 12:1463–1479. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viktorova EG, Gabaglio S, Meissner JM, Lee E, Moghimi S, Sztul E, Belov GA. 2019. A redundant mechanism of recruitment underlies the remarkable plasticity of the requirement of poliovirus replication for the cellular ArfGEF GBF1. J Virol 93:e00856-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferlin J, Farhat R, Belouzard S, Cocquerel L, Bertin A, Hober D, Dubuisson J, Rouille Y. 2018. Investigation of the role of GBF1 in the replication of positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses. J Gen Virol 99:1086–1096. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang JM, Du J, Jin Q. 2014. Class I ADP-ribosylation factors are involved in enterovirus 71 replication. PLoS One 9:e99768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moss J, Vaughan M. 1995. Structure and function of Arf proteins—activators of cholera-toxin and critical components of intracellular vesicular transport processes. J Biol Chem 270:12327–12330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sztul E, Chen P-W, Casanova JE, Cherfils J, Dacks JB, Lambright DG, Lee F-JS, Randazzo PA, Santy LC, Schürmann A, Wilhelmi I, Yohe ME, Kahn RA. 2019. ARF GTPases and their GEFs and GAPs: concepts and challenges. Mol Biol Cell 30:1249–1271. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E18-12-0820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cavenagh MM, Whitney JA, Carroll K, Zhang CJ, Boman AL, Rosenwald AG, Mellman I, Kahn RA. 1996. Intracellular distribution of Arf proteins in mammalian cells—Arf6 is uniquely localized to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 271:21767–21774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Claude A, Zhao BP, Kuziemsky CE, Dahan S, Berger SJ, Yan JP, Armold AD, Sullivan EM, Melancon P. 1999. GBF1: a novel Golgi-associated BFA-resistant guanine nucleotide exchange factor that displays specificity for ADP-ribosylation factor 5. J Cell Biol 146:71–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niu TK, Pfeifer AC, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Jackson CL. 2005. Dynamics of GBF1, a brefeldin A-sensitive Arf1 exchange factor at the Golgi. Mol Biol Cell 16:1213–1222. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e04-07-0599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cherfils J. 2014. Arf GTPases and their effectors: assembling multivalent membrane-binding platforms. Curr Opin Struct Biol 29:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chun J, Shapovalova Z, Dejgaard SY, Presley JF, Melancon P. 2008. Characterization of class I and II ADP-ribosylation factors (Arfs) in live cells: GDP-bound class II Arfs associate with the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment independently of GBF1. Mol Biol Cell 19:3488–3500. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e08-04-0373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altan-Bonnet N, Phair RD, Polishchuk RS, Weigert R, Lippincott-Schwartz J. 2003. A role for Arf1 in mitotic Golgi disassembly, chromosome segregation, and cytokinesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:13314–13319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234055100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Presley JF, Ward TH, Pfeifer AC, Siggia ED, Phair RD, Lippincott-Schwartz J. 2002. Dissection of COPI and Arf1 dynamics in vivo and role in Golgi membrane transport. Nature 417:187–193. doi: 10.1038/417187a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moorhead AM, Jung JY, Smirnov A, Kaufer S, Scidmore MA. 2010. Multiple host proteins that function in phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate metabolism are recruited to the chlamydial inclusion. Infect Immun 78:1990–2007. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01340-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu MM, Shu HB. 2019. Innate immune response to cytoplasmic DNA: mechanisms and diseases. Annu Rev Immunol 38:79–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-070119-115052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao XH, Lasell TKR, Melancon P. 2002. Localization of large ADP-ribosylation factor-guanine nucleotide exchange factors to different Golgi compartments: evidence for distinct functions in protein traffic. Mol Biol Cell 13:119–133. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-08-0420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.D'souza-Schorey C, Li GP, Colombo MI, Stahl PD. 1995. A regulatory role for Arf6 in receptor-mediated endocytosis. Science 267:1175–1178. doi: 10.1126/science.7855600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peters PJ, Hsu VW, Ooi CE, Finazzi D, Teal SB, Oorschot V, Donaldson JG, Klausner RD. 1995. Overexpression of wild-type and mutant Arf1 and Arf6—distinct perturbations of nonoverlapping membrane compartments. J Cell Biol 128:1003–1017. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hornbeck PV, Zhang B, Murray B, Kornhauser JM, Latham V, Skrzypek E. 2015. PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D512–D520. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beske O, Reichelt M, Taylor MP, Kirkegaard K, Andino R. 2007. Poliovirus infection blocks ERGIC-to-Golgi trafficking and induces microtubule-dependent disruption of the Golgi complex. J Cell Sci 120:3207–3218. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quiner CA, Jackson WT. 2010. Fragmentation of the Golgi apparatus provides replication membranes for human rhinovirus 1A. Virology 407:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker PJ, Siddell SG, Lefkowitz EJ, Mushegian AR, Dempsey DM, Dutilh BE, Harrach B, Harrison RL, Hendrickson RC, Junglen S, Knowles NJ, Kropinski AM, Krupovic M, Kuhn JH, Nibert M, Rubino L, Sabanadzovic S, Simmonds P, Varsani A, Zerbini FM, Davison AJ. 2019. Changes to virus taxonomy and the International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2019). Arch Virol 164:2417–2429. doi: 10.1007/s00705-019-04306-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gazina EV, Mackenzie JM, Gorrell RJ, Anderson DA. 2002. Differential requirements for COPI coats in formation of replication complexes among three genera of Picornaviridae. J Virol 76:11113–11122. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.21.11113-11122.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shemiakina II, Ermakova GV, Cranfill PJ, Baird MA, Evans RA, Souslova EA, Staroverov DB, Gorokhovatsky AY, Putintseva EV, Gorodnicheva TV, Chepurnykh TV, Strukova L, Lukyanov S, Zaraisky AG, Davidson MW, Chudakov DM, Shcherbo D. 2012. A monomeric red fluorescent protein with low cytotoxicity. Nat Commun 3:1204. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nugent CI, Johnson KL, Sarnow P, Kirkegaard K. 1999. Functional coupling between replication and packaging of poliovirus replicon RNA. J Virol 73:427–435. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.1.427-435.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Z, Chumakov K, Dragunsky E, Kouiavskaia D, Makiya M, Neverov A, Rezapkin G, Sebrell A, Purcell R. 2011. Chimpanzee-human monoclonal antibodies for treatment of chronic poliovirus excretors and emergency postexposure prophylaxis. J Virol 85:4354–4362. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02553-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teterina NL, Pinto Y, Weaver JD, Jensen KS, Ehrenfeld E. 2011. Analysis of poliovirus protein 3A interactions with viral and cellular proteins in infected cells. J Virol 85:4284–4296. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02398-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Volpicelli-Daley LA, Li YW, Zhang CJ, Kahn RA. 2005. Isoform-selective effects of the depletion of ADP-ribosylation factors 1–5 on membrane traffic. Mol Biol Cell 16:4495–4508. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e04-12-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montagnac G, Sibarita JB, Loubery S, Daviet L, Romao M, Raposo G, Chavrier P. 2009. ARF6 interacts with JIP4 to control a motor switch mechanism regulating endosome traffic in cytokinesis. Curr Biol 19:184–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siltz LAF, Viktorova EG, Zhang B, Kouiavskaia D, Dragunsky E, Chumakov K, Isaacs L, Belov GA. 2014. New small-molecule inhibitors effectively blocking picornavirus replication. J Virol 88:11091–11107. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01877-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Belov GA. 2016. Dynamic lipid landscape of picornavirus replication organelles. Curr Opin Virol 19:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Belov GA. 2014. Modulation of lipid synthesis and trafficking pathways by picornaviruses. Curr Opin Virol 9:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Belov GA, van Kuppeveld FJM. 2012. (+)RNA viruses rewire cellular pathways to build replication organelles. Curr Opin Virol 2:740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wessels E, Duijsings D, Lanke KH, Melchers WJ, Jackson CL, van Kuppeveld FJ. 2007. Molecular determinants of the interaction between coxsackievirus protein 3A and guanine nucleotide exchange factor GBF1. J Virol 81:5238–5245. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02680-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wessels E, Duijsings D, Lanke KH, van Dooren SH, Jackson CL, Melchers WJ, van Kuppeveld FJ. 2006. Effects of picornavirus 3A proteins on protein transport and GBF1-dependent COP-I recruitment. J Virol 80:11852–11860. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01225-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wessels E, Duijsings D, Niu TK, Neumann S, Oorschot VM, de Lange F, Lanke KH, Klumperman J, Henke A, Jackson CL, Melchers WJ, van Kuppeveld FJ. 2006. A viral protein that blocks Arf1-mediated COP-I assembly by inhibiting the guanine nucleotide exchange factor GBF1. Dev Cell 11:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nie ZZ, Hirsch DS, Randazzo PA. 2003. Arf and its many interactors. Curr Opin Cell Biol 15:396–404. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(03)00071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jackson CL. 2014. Arf proteins and their regulators: at the interface between membrane lipids and the protein trafficking machinery. Wittinghofer A (ed), Ras superfamily small G proteins: biology and mechanisms 2. Springer, Cham, Switzerland. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-07761-1_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.D'Souza-Schorey C, Chavrier P. 2006. ARF proteins: roles in membrane traffic and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7:347–358. doi: 10.1038/nrm1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ilnytska O, Santiana M, Hsu NY, Du WL, Chen YH, Viktorova EG, Belov G, Brinker A, Storch J, Moore C, Dixon JL, Altan-Bonnet N. 2013. Enteroviruses harness the cellular endocytic machinery to remodel the host cell cholesterol landscape for effective viral replication. Cell Host Microbe 14:281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aldabe R, Barco A, Carrasco L. 1996. Membrane permeabilization by poliovirus proteins 2B and 2BC. J Biol Chem 271:23134–23137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Madan V, Redondo N, Carrasco L. 2010. Cell permeabilization by poliovirus 2B viroporin triggers bystander permeabilization in neighbouring cells through a mechanism involving gap junctions. Cell Microbiol 12:1144–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Jong AS, de Mattia F, Van Dommelen MM, Lanke K, Melchers WJG, Willems PHGM, van Kuppeveld FJM. 2008. Functional analysis of picornavirus 2B proteins: effects on calcium homeostasis and intracellular protein trafficking. J Virol 82:3782–3790. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02076-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martinez-Gil L, Bano-Polo M, Redondo N, Sanchez-Martinez S, Nieva JL, Carrasco L, Mingarro I. 2011. Membrane integration of poliovirus 2B viroporin. J Virol 85:11315–11324. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05421-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Kuppeveld FJ, Melchers WJ, Kirkegaard K, Doedens JR. 1997. Structure-function analysis of coxsackie B3 virus protein 2B. Virology 227:111–118. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.de Jong AS, Melchers WJG, Glaudemans DHRF, Willems PHGM, van Kuppeveld FJM. 2004. Mutational analysis of different regions in the coxsackievirus 2B protein—requirements for homo-multimerization, membrane permeabilization, subcellular localization, and virus replication. J Biol Chem 279:19924–19935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314094200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Belov GA, Nair V, Hansen BT, Hoyt FH, Fischer ER, Ehrenfeld E. 2012. Complex dynamic development of poliovirus membranous replication complexes. J Virol 86:302–312. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05937-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Limpens RW, van der Schaar HM, Kumar D, Koster AJ, Snijder EJ, van Kuppeveld FJ, Barcena M. 2011. The transformation of enterovirus replication structures: a three-dimensional study of single- and double-membrane compartments. mBio 2:e00166-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]