Abstract

The position of immunotherapy as a pillar of systemic cancer treatment has been firmly established over the past decade. Immune checkpoint inhibitors are a welcome option for patients with different malignancies. This is in part because they offer the possibility of durable benefit, even for patients who have failed other treatment modalities. The recent demonstration that immunotherapy is effective for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a milestone in the history of this recalcitrant disease. The treatment of HCC has been a challenge, and for many years was limited to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib and to several novel tyrosine kinase inhibitors that have shown efficacy and have been approved. The current role of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the management of HCC, and how this role is likely to evolve in the years ahead, are key. Other than efforts evaluating single checkpoint inhibitors, potential combination strategies, including combinations with existing local and systemic approaches, including novel therapies are evolving. This is understandably of special interest considering the potential unique immune system of the liver, which may impact the use of immunotherapy in patients with HCC going forward, and how can it be enhanced further.

Keywords: checkpoint inhibitor, CTLA-4, durvalumab, hepatocellular carcinoma, PD-1, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, tremelimumab

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the leading causes of cancer-related death worldwide.1 Its incidence continues to rise in the United States, mostly secondary to hepatitis C (HCV) infection and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. HCV-related HCC is anticipated to decline with the advent of novel curative therapies for HCV,2,3 whereas nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-related HCC may become the principal cause of HCC in the United States due to the continued increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus and morbid obesity.4,5 Hepatitis B continues to drive the majority of the global burden of HCC, especially in southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.6

When patients are diagnosed with HCC, they are more likely to present with smaller tumors and undergo a curative approach. Despite those curative efforts, the majority of patients ultimately will experience a recurrence of their disease.7

Over the last few years, medicine has witnessed a paradigm shift in the treatment of patients with HCC. Patients with advanced HCC did not have an adequate therapy. Today, patients have access to several tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and immune checkpoint inhibitors, plus an abundant number of investigational agents and approaches. TKIs have added clinically meaningful and long-awaited improvements in overall survival (OS) for patients with advanced and metastatic disease. After the development of sorafenib,8,9 4 agents have demonstrated improved outcome data: lenvatinib10 in the first-line and regorafenib,11 cabozantinib,12 and ramucirumab13 after first-line disease progression.

Grounded in the unique liver immunobiology and unmet needs for patients with advanced and metastatic disease, immune checkpoint inhibitors has been explored extensively in patients with HCC. Herein, we focus on the unique liver immunobiology and the recent therapeutic advances from an immune-oncology perspective.

Hepatic Immunobiology

The adaptive immune system is speculated to have evolved as an accessory to the digestive system, which faces the immense challenge of distinguishing pathogenic from benign foreign antigens.14 Failure to respond to pathogenic nonself-antigens would markedly increase the risk of fulminant infection, whereas failure to tolerate nonself-antigens in the diet or the microbiota could lead to severe inflammatory disease.

To the best of our knowledge, the mechanisms by which these distinctions are made remain poorly understood. An important, but only partial, explanation is the presence of pathogen-associated molecular patterns that are associated with foreign proteins.15 As expected, highly specialized immune microenvironments exist at host tissues that are chronically exposed to nonself-antigens. These include, most prominently, the digestive mucosa and the hepatic parenchyma. The mucosa is exposed to dietary and microbial antigens in the lumen of the digestive tract, whereas the liver encounters the same molecules as they arrive from the gut via the portal vein.16

Central to the robust discriminatory capacity at both these sites, at the interface of the adaptive and innate immune systems, is the antigen-presenting cell (APC), most notably the dendritic cell (DC).17 Among other roles, DCs are particularly effective at priming T cells.18 Both DCs and T cells exist in multiple subtypes with divergent, and sometimes opposing, functions.

The hepatic microenvironment is rich in colony-stimulating factor 1 and hepatocyte growth factor, which act on local DCs to promote a tolerogenic phenotype. Such DCs express a relatively high level of interleukin 10, prostaglandin E2, and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and low expression of the cytokine interleukin 12 and APC activation markers including CD80, CD83, CD86, and CD40.19–21 APCs in this milieu are impaired in their ability to stimulate T cells via CD28 on T cells (so-called signal 2), whereas they retain their ability to signal to T cells via the T-cell receptor (signal 1). The result of this type of signaling is not merely an inability to prime T cells to their cognate antigen, but rather a functional loss of the specific T-cell populations. making it more difficult and potentially impossible to respond to the antigen upon subsequent exposure.22,23 This process of active tolerance is of great value in preventing undesirable immune reactions to benign targets, but it also may prevent protective immune responses in the case of malignancy.

HCC and Immunomodulation

To a greater degree than most cancers, the treatment of HCC involves multiple diverse modalities. These include surgery, ablation, and various types of embolization for liver-limited disease and biologics and chemotherapy for the treatment of systemic disease. Each of these approaches impacts the immune system in ways that have potential clinical significance.

At this time, there are only 2 immunotherapeutic agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of HCC: the PD-1-blocking monoclonal antibodies nivolumab and pembrolizumab.24 Both act directly on immune cells and block the inhibitory T-cell receptor PD-1. This is not to say that treatments that act directly on malignant cells are immunologically inert. On the contrary, the way they induce tumor cell lysis has a profound impact on immunogenicity, particularly in an organ such as the liver that is strongly disposed to immune tolerance.

From an immunology perspective, cell death can be separated into 2 categories: immunogenic and nonimmunogenic. Although the distinction is not always absolute, in general, immunogenic cell death (ICD) is associated with the release of factors that attract and stimulate innate immune cells. For example, in a classic model, ICD is associated with the release of ATP to generate a gradient around the dying cell that allows innate immune cells to home to the target; the transfer of calreticulin to the cell surface, which promotes phagocytosis of the dying cell; and the release of HMGB-1, which activates TLR4, among other receptors, to activate the innate immune cell.25

Since the conditional approval of PD-1 blockade for systemic HCC,26 multiple avenues of research regarding the relationship between the immune system and HCC have opened (eg, the mechanism by which anti-PD-1 agents exert an anti-HCC effect remains not fully understood). To the best of our knowledge, there still is no decisive evidence that HCC etiology may impact response to treatment. Whether virally induced HCC (secondary to hepatitis B virus or HCV) is more prone to immune attack either secondary to the presence of foreign viral antigens or an immune response to the virus remains a valid, yet-to-be-answered question. If the presumption is that virally induced hepatitis is not more sensitive to immunotherapy, then the question as to what factors in non-virally induced HCC are responsible for potentiating a response to immunomodulation and whether this has a predictive value need to be answered. PD-L1 status on HCC cells, when considered in isolation, does not appear to clearly correlate with response to PD-1-based therapy26 as it does in certain other cancers.27 Given the unique role that DCs and other APCs play in the liver, it may be worth investigating whether PD-L1 expression on APCs, rather than malignant cells, may play a role in predicting response to therapy.

Such work would take place as multiple other biomarkers, including tumor mutation burden (TMB), are being actively investigated. Although the results from other tumor types cannot be directly applied to HCC, TMB among patients with non-small cell lung cancer has been correlated with response to anti-PD-1 therapy.28 TMB also has been used in melanoma to predict outcomes in response to the blockade of PD-129 as well as CTLA-4.30

It is likely that checkpoint inhibitors act via a distinct mechanism in HCC compared with other malignancies. Contrary to TMB in other tumors, the liver tumor microenvironment balance among different cells that promote or prevent tumor growth may well be the target of checkpoint inhibitors.17

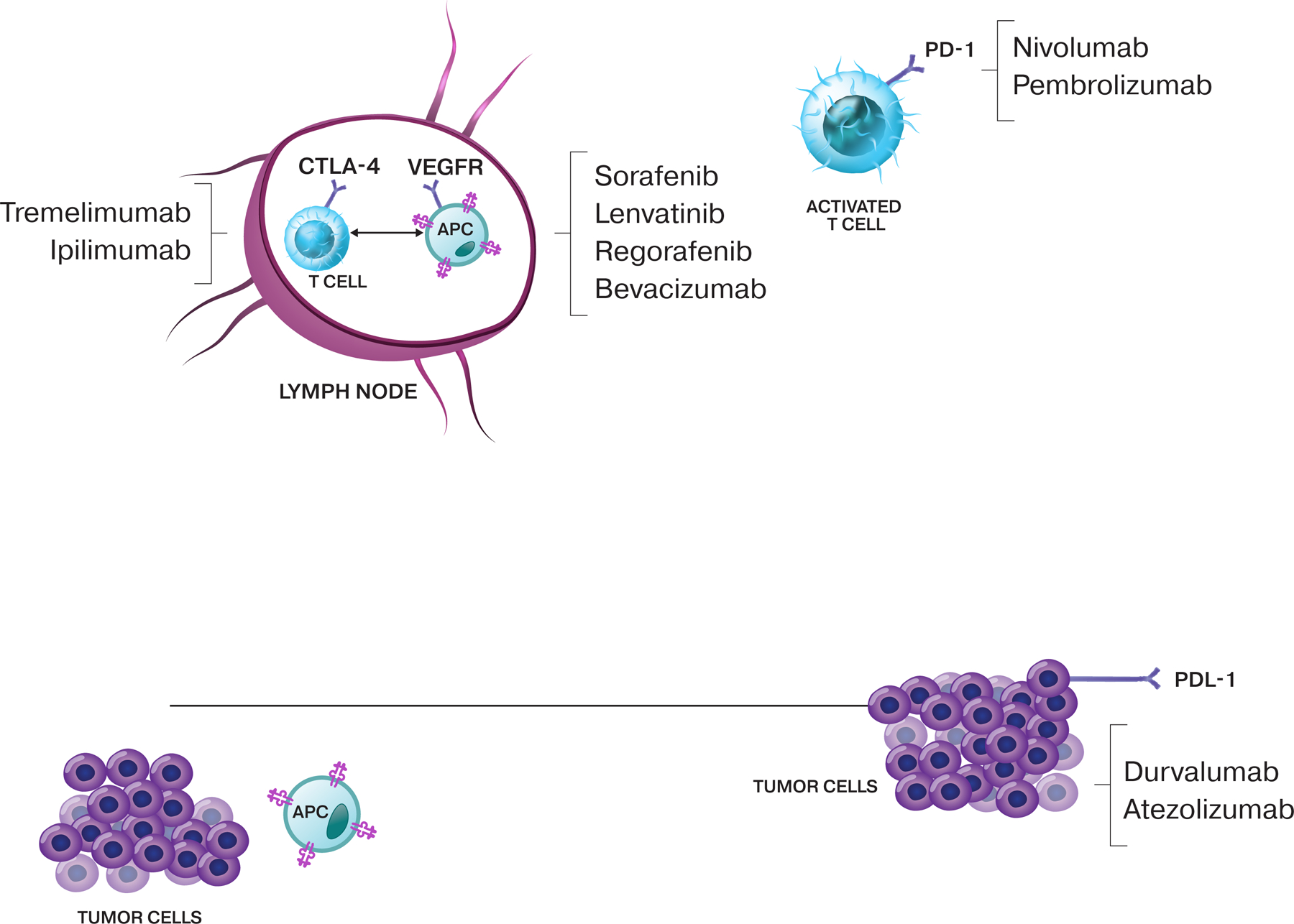

It is worth noting that both CTLA-4 and PD-1 blunt T-cell priming at the synapse between T cells and APCs (because APCs can express the ligands CD80/86 and PD-L1, respectively31), and blockade of these interactions may play a unique role in the liver, in which productive T-cell priming generally is curtailed (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The cycle of immunity to cancer. The cycle starts with the release of antigens from the cancer cells, which are taken up by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), which undergo priming and activation in the lymph node. Activated T cells circulate back to the tumor, in which they recognize and attack cancer cells. Immune checkpoint proteins, such as CTLA-4, can inhibit the development of an active immune response by acting primarily at the level of T-cell development and proliferation, whereas PD-L1 can have an inhibitory function that primarily acts to modulate active immune responses in the tumor. Examples of therapies and the factors at which they can act are shown.

Careful consideration should be given to whether the already approved anti-HCC therapies may potentiate a response to PD-1 blockade. For example, it has been reported that PD-L1 expression in HCC samples increases after treatment with sorafenib.32 This suggests that sorafenib treatment may recruit T cells to the tumor and then elicit PD-L1 expression (possibly by expression of interferon-γ). To the best of our knowledge, the mechanism of this change remains to be elucidated and may be related to the type of cell death induced by sorafenib or the inhibition of specific tyrosine kinases such as vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

A systematic evaluation of the T-cell infiltrate before and after treatment may shed light on which agents are most likely to potentiate checkpoint blockade. This would also help to determine whether the T-cell infiltrate itself is predictive of response to immunotherapy.

Biomarkers may play a role in the development of other agents designed to stimulate an antitumor T-cell response by blocking inhibitory T-cell receptors. These include antagonist monoclonal antibodies directed against TIM3 and LAG3. The latter is particularly promising given its elevated expression in HCC-infiltrating lymphocytes.33

Checkpoint inhibitors

To the best of our knowledge, one of the earliest immunotherapy trials that established promising activity was a phase 2 study of the anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody tremelimumab in patients with advanced HCC and HCV-related cirrhosis who developed disease progression while receiving sorafenib. Of 17 patients, 3 (17.6%) achieved a partial response and 10 patients (58.8%) had stable disease. The disease control rate (DCR) was 76.4%, and the clinical benefit was >12 months in approximately one-third of patients. The median time to disease progression (TTP) was 6.5 months, which is favorable compared with historical controls. Clearance of HCV was observed, and the most common treatment-related adverse event was elevation in transaminases.34 In a previous report, MEDI4736 (durvalumab), a human immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody to PD-L1, was found to be well tolerated. Of 19 evaluable patients with HCC, there were no responders as per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1, although 21% of patients achieved DCR at 12 weeks.35

Nivolumab, a fully human immunoglobulin G4 monoclonal antibody to PD-1, was evaluated in an HCC-specific phase 1/2 clinical trial.26 A total of 262 patients were treated: 48 patients in the dose escalation phase and 214 patients in the dose expansion phase. During dose escalation, nivolumab demonstrated a manageable safety profile, including acceptable tolerability. Nivolumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg was chosen for dose expansion. The objective response rate (ORR) was 20% (95% CI, 15%−26%) in patients treated with nivolumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg in the dose expansion phase and 15% (95% CI, 6%−28%) in the dose escalation phase. The DCR was 58% (95% CI, 43%−72%) and the median TTP was 3.4 months (95% CI, 1.6–6.9 months). The median duration of response was 17 months (95% CI, 6–24 months) and the 6-month and 9-month OS rates were both 66% (95% CI, 51%−78%). The median OS for patients in the dose escalation phase was 15 months (95% CI, 9.6–20.2 months). Responses were observed regardless of etiology, tumor PD-L1 expression, and prior sorafenib exposure. An updated report from the phase 1/2 nivolumab clinical trial demonstrated the activity and tolerability of nivolumab in patients with Child-Pugh B cirrhosis with an ORR and DCR of 10% and 55%, respectively. Among the 40 patients evaluated, the median time to response was 2.7 months, and the median duration of response was 9.9 months with a median OS of 7.6 months.36 Understandably, a larger number of patients may be needed to help evaluate the safety and efficacy of nivolumab in patients with more advanced cirrhosis.

Based on this study, nivolumab was granted conditional FDA approval as second-line treatment of patients with advanced and metastatic HCC, pending the outcome of a phase 3, randomized, open-label study of first-line nivolumab versus sorafenib (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02576509). The study completed its accrual in 2018 and to our knowledge the results still are pending.

Although one may anticipate the study to be positive in favor of nivolumab, it is important to assess the scenario in which it is not. If we were not to observe a difference in OS, this may be attributed to the availability of nivolumab/other checkpoint inhibitors after disease progression while receiving sorafenib. This may suggest the agnostic timing to the treatment with a checkpoint inhibitor. More intriguing, one may speculate that prior exposure to sorafenib as a TKI might potentiate a response to subsequent treatment with PD-1 blockade.

Pembrolizumab, a PD-1 antibody, was evaluated in a nonrandomized, multicenter, open-label, phase 2 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02658019). The primary endpoint was ORR by RECIST version 1.1. A total of 104 patients who developed disease progression after sorafenib therapy were enrolled. The ORR was observed in 18 of 104 patients (17%; 95% CI, 11%−26%), with 1 (1%) complete response and 17 (16%) partial responses; meanwhile, 46 patients (44%) had stable disease, 34 (33%) had progressive disease, and 6 patients (6%) were not evaluable at the time of analysis.37 The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 4.9 months and the median OS was 12.9 months. In a prespecified subgroup analyses, the percentage of patients with an objective response generally was similar across prespecified subgroups of participants with various risk factors, including macrovascular invasion, viral infections, and reasons for the discontinuation of sorafenib. Based on those results, pembrolizumab was granted accelerated FDA approval in patients with HCC who have been previously treated with sorafenib. Pembrolizumab underwent further assessment in a phase 3, randomized, double-blind trial versus placebo as a second-line treatment in patients with HCC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifer NCT02702401). In a recent press release, it was reported that the study did not meet its coprimary endpoints of OS and PFS, with an OS hazard ratio of 0.78 (95% CI, 0.611–0.998; P=.0238) and a PFS hazard ratio of 0.78 (95% CI, 0.61–0.99; P=.0209).38 A similar study among Asian patients currently is ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03062358).

In preclinical studies, the combination of anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies enhanced antitumor activity compared with monotherapy, indicating that the 2 pathways are nonredundant. In a phase 1/2 open-label, randomized study of durvalumab combined with tremelimumab in patients with unresectable HCC, the DCR was 57.5% (23 of 40 patients).39 There were no unexpected safety signals with the combination. The phase 2 portion of the study still is ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02519348). Although clinical activity was observed for the most part in uninfected patients, the interpretation of potential differences in response based on viral etiology remains limited by the small number of patients and would require further evaluation as a possible part of the ongoing, multiple phase 3 clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03298451), which to the best of our knowledge is the first randomized, open-label, multicenter, phase 3 study to assess the efficacy and safety of durvalumab as monotherapy and in combination with tremelimumab versus sorafenib in the first-line treatment of patients with unresectable, histologically confirmed HCC. The primary endpoint is the evaluation of OS with durvalumab plus tremelimumab versus sorafenib.

Immunotherapy-based combinations

Investigators also have studied combining immune checkpoint blockade with antiangiogenic agents. The rationale behind the study is that the combination might result in a greater clinical benefit due to the additional immunomodulatory effects of bevacizumab. The combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab was evaluated for safety and tolerability.40 Secondary endpoints included ORR, TTP, and OS. Among 21 efficacy-evaluable patients, confirmed partial responses occurred in 13 patients (62%) regardless of HCC etiology, region, baseline α-fetoprotein levels (≥400 ng/mL or <400 ng/mL), or extrahepatic spread of tumor. Results later were updated, still in abstract form.41 The ORRs of 32% as per RECIST version 1.1 criteria and 34% as per modified RECIST criteria clearly appear more realistic than the initially reported ORR of 62%. Responses were observed in all clinically relevant subgroups, including patients with α-fetoprotein levels ≥400 ng/mL.

Similarly, a phase 1b trial of lenvatinib with pembrolizumab currently is underway (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03006926). Preliminary results have demonstrated that the combination was well tolerated. Exploratory endpoints included ORR and survival outcomes. Of 18 patients, 6 (46%) achieved partial responses by modified RECIST criteria and 6 (46%) had stable disease.42 Two cohorts were added to the phase 1/2 nivolumab clinical trial to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of nivolumab in combination with sorafenib and cabozantinib in 2 different cohorts (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01658878). Other ongoing immune checkpoint inhibitor trials are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Status of Current Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor and Combination Trials in Advanced HCC

| ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | Agent | Target | Design | Endpoints | Accrual Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT02576509 | Nivolumab vs sorafenib | PD-1 TKI |

Phase 3 | TTP/OS | Accrual complete |

| NCT02702401 | Pembrolizumab vs BSC | PD-1 | Phase 3 | PFS/OS | Accrual complete |

| NCT03298451 | Durvalumab +/−tremelimumab vs sorafenib | PD-L1 CTLA-4 TKI |

Phase 3 | OS | Active accrual |

| NCT03434379 | Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs sorafenib | PD-L1 VEGFR TKI |

Phase 3 | ORR/OS | Active accrual |

| NCT01658878 | Nivolumab plus ipilimumab | PD-1 CTLA-4 |

Phase 1/2 | Safety/ORR | Active accrual |

| NCT02519348 | Durvalumab +/−tremelimumab | PD-L1 CTLA-4 |

Phase 1/2 | Safety/ORR | Active accrual |

| NCT01658878 | Nivolumab plus cabozantinib +/− ipilimumab | PD-1 TKI CTLA-4 |

Phase 1/2 | Safety/ORR | Active accrual |

| NCT03006926 | Pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib | PD-1 TKI |

Phase 1 | Safety | Active accrual |

| NCT03289533 | Avelumab plus axitinib | PD-L1 TKI |

Phase 1 | Safety | Active accrual |

| NCT03418922 | Nivolumab plus lenvatinib | PD-1 TKI |

Phase 1 | Safety | Active accrual |

| NCT03347292 | Pembrolizumab plus regorafenib | PD-1 TKI |

Phase 1 | Safety | Not yet accruing |

| NCT03439891 | Nivolumab plus sorafenib | PD-1 TKI |

Phase 1/2 | Safety/ORR | Not yet accruing |

Abbreviations: BSC, best supportive care; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ORR, objective response rate; OS, overall survival; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; PFS, progression-free survival; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; TTP, time to disease progression; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Local Therapies and Checkpoint Inhibitors

Post-transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) cell necrosis is predicted to be associated with antigen release, and the exposure of damage-associated molecular patterns, which can activate APCs, which have phagocytosed tumor antigens.43 It was hypothesized that the concomitant administration of a checkpoint inhibitor may enable a robust tumor-specific immune response by bolstering the function of T cells primed by activated APCs. This theoretical strategy is being tested in early clinical trials that combine TACE with tremelimumab, durvalumab, or nivolumab.

Preliminary results from a phase 1 trial were presented in abstract form.44 Patients with HCC (32 patients) or biliary tract carcinoma (9 patients) were treated with TACE, radiofrequency ablation, or cryoablation in combination with tremelimumab. Of the evaluable patients, 23.5% (4 of 17 patients) achieved a partial response. Tumor biopsy at 6 weeks suggested that the clinical response was associated with activation of CD4-positive and CD8-positive T cells. The median PFS among the evaluable patients with HCC was 5.7 months. At least 2 additional studies of local ablative therapy with immunotherapy are expected. A phase 1/2 trial currently is recruiting patients for a comparative study of durvalumab plus tremelimumab in combination with TACE, radiofrequency ablation, or cryoablation (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02821754). To the best of our knowledge, one of the earliest efforts in this regard is a pilot study evaluating the combination of nivolumab and drug-eluting bead TACE in patients with locally advanced HCC. This is a multicenter phase 1 study of the combination in patients with unresectable HCC with Child-Pugh A hepatic function. The primary objectives are to assess the safety and tolerability and to define the optimal dosing schedule of the combination. Correlative objectives include sequential whole-blood sampling and biopsies (pretreatment, while receiving treatment, and at the time of disease progression) to define mechanisms of anti-PD-1 resistance.45 The study is actively accruing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03143270).

Arguably, the most thoroughly studied therapeutic modality that induces ICD is external radiation. More than any other therapy, radiation is associated with the most clinically meaningful readout of true ICD, namely an abscopal effect. An abscopal effect (whether induced by radiation, intratumoral injection, or any other local treatment) is defined by the response in a distant tumor that is not in direct contact with the local treatment. The reason that this is such an important indicator of ICD is that it suggests activation of an APC (whether that be a professional APC, another immune cell, or even the tumor cell itself) such that it becomes capable of priming lymphocytes capable of acting systemically and controlling a distant tumor. Although the abscopal effect from radiation is rare, it has been observed anecdotally for decades, even in the absence of systemic therapy.46–48 More recently, intratumoral viral therapy has been shown to induce an abscopal effect in patients with melanoma.49 In addition, the direct injection of tumors with antibodies to generate an abscopal effect currently is under active investigation (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02706353). In the future, we expect to see more clinical trials along these lines with agents such as TLR agonists (eg, TLR3, TLR4, and TLR9) and other APC-activating compounds. Given that these agents usually are intended to ultimately stimulate a systemic antitumor T-cell response, coupling them with systemic T-cell stimulatory agents (such as anti-PD-1 or anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies) should be tested.

Such APC-directed intratumoral therapy is of particular interest in the liver, in which tolerogenic APCs actively resist activation. This suggests that therapy that successfully surmounts this barrier would allow the immune system to act on HCC in a way not previously possible. Conversely, it also may lead to greater toxicity because it would reverse the physiologic immune tolerance that is important for avoiding inflammatory diseases, as discussed above.

Systemic therapy, although by definition not able to induce an abscopal effect, can induce ICD. For reasons that to our knowledge are not fully elucidated, certain chemotherapies such as oxaliplatin have been shown to induce ICD,50,51 whereas others such as cisplatin appear unable to do so.25 Oxaliplatin (together with 5-fluorouracil) can be used in the treatment of systemic HCC52 and in combination with other immunotherapies, such as anti-PD-1 agents, and thus may warrant testing.

Doxorubicin, another chemotherapy agent shown to induce ICD,53 often is used in chemoembolization for patients with liver-limited HCC.54 To the best of our knowledge, how much of this effect is due to an immune response has not yet been investigated thoroughly. However, it remains entirely feasible that, when used in this way, doxorubicin can stimulate APCs exposed to tumor antigens that would, in turn, prime antitumor T cells. This strongly suggests that its combination with systemic immunotherapy warrants testing, as is currently underway in a clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03143270) that tests the combination of chemoembolization with doxorubicin drug-eluting beads administered with nivolumab. Similar studies with radioembolization, which also is a standard approach for the treatment of patients with liver-limited HCC, also would be of interest.

Conclusions

Immune checkpoint therapy remains interesting and currently is evolving in the field of HCC. Checkpoint inhibitors already have been shown to result in clinically significant improvements in certain outcomes, yet we still are awaiting the observation of a clear improvement in the survival signal. Immunotherapy-based combinations and combinations with TKIs have demonstrated notable objective responses and are being evaluated further with the goal of demonstrating an improvement in OS. Other efforts evaluating checkpoint inhibitors with local therapies currently are underway. Initial data have demonstrated these different combinations to be safe, yet this is to be explored further in ongoing and future studies, in addition of course to hands-on clinical experience. To the best of our knowledge, it remains unclear whether underlying etiology or the addition of ICD-generating therapies exerts a substantial effect on treatment response. However, future directions will concentrate on identifying biomarkers of response and the optimal lining of various available therapies in patients with HCC.

The recent demonstration that immunotherapy is effective for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma is a milestone in the history of this recalcitrant disease. Other than efforts evaluating single checkpoint inhibitors, potential combination strategies, including combinations with existing local and systemic approaches, as well as with novel therapies are evolving.

FUNDING SUPPORT

No specific funding was disclosed.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Danny N. Khalil has a patent PCT/US2016/045970 pending. Ghassan K. Abou-Alfa has received grants from Acta Biologica, Agios, Array, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BeiGene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Casi, Celgene, Exelixis, Genentech, Halozyme, Incyte, Lilly, MabVax, Novartis, OncoQuest, Polaris Puma, QED, and Roche and has acted as a paid consultant for 3DMedcare, Agios, Alignmed, Amgen, Antengene, Aptus, Aslan, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BeiGene, BioLineRx, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boston Scientific, BridgeBio, CARsgen, Celgene, Casi, Cipla, CytomX, Daiichi, Debio, Delcath, Eisai, Exelixis, Genoscience, Gilead, Halozyme, Hengrui, Incyte, Inovio, Ipsen, Jazz, Jansen, Kyowa Kirin, LAM, Lilly, Loxo, Merck, Mina, NewLink Genetics Corporation, Novella, Onxeo, PCI Biotech, Pfizer, PharmaCyte, Pharmacyclics, Pieris, QED, Redhill, Sanofi, Servier, Silenseed, Sillajen, Sobi, Targovax, Tekmira, TwoXAR, Vicus, Yakult, and Yiviva for work performed as part of the current study. Imane El Dika made no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wallace MC, Preen D, Jeffrey GP, Adams LA. The evolving epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a global perspective. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;9:765–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ioannou GN, Green PK, Berry K. HCV eradication induced by direct-acting antiviral agents reduces the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma [published online September 5, 2017]. J Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, Chayanupatkul M, Cao Y, El-Serag HB. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology 2017;153:996–1005.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2012;142:1264–1273.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mittal S, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: consider the population. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47(suppl):S2–S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kew MC. Epidemiology of chronic hepatitis B virus infection, hepatocellular carcinoma, and hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2010;58:273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stravitz RT, Heuman DM, Chand N, et al. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis improves outcome. Am J Med 2008;121:119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. ; SHARP Investigators Study Group. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008;359:378–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2018;391:1163–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al. ; RESORCE Investigators. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;389:56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced and progressing hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018;379:54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu AX, Galle PR, Kudo M, et al. A study of ramucirumab (LY3009806) versus placebo in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and elevated baseline alpha-fetoprotein (REACH-2). J Clin Oncol 2018;36:TPS538. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsunaga T, Rahman A. What brought the adaptive immune system to vertebrates?-the jaw hypothesis and the seahorse. Immunol Rev 1998;166:177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol 2010;11:373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau AH, Thomson AW. Dendritic cells and immune regulation in the liver. Gut 2003;52:307–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eggert T, Greten TF. Tumor regulation of the tissue environment in the liver. Pharmacol Ther 2017;173:47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 1998;392:245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li G, Kim YJ, Broxmeyer HE. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor drives cord blood monocyte differentiation into IL-10(high)IL-12absent dendritic cells with tolerogenic potential. J Immunol 2005;174:4706–4717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutella S, Bonanno G, Procoli A, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor favors monocyte differentiation into regulatory interleukin (IL)-10++IL-12low/neg accessory cells with dendritic-cell features. Blood 2006;108:218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia G, He J, Leventhal JR. Ex vivo-expanded natural CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells synergize with host T-cell depletion to promote long-term survival of allografts. Am J Transplant 2008;8:298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2003;21:685–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clemente-Casares X, Blanco J, Ambalavanan P, et al. Expanding antigen-specific regulatory networks to treat autoimmunity. Nature 2016;530:434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Food and Drug Administration. Hematology/oncology (cancer) approvals & safety notifications https://www.fda.gov/drugs/informationondrugs/approveddrugs/ucm279174.htm. Accessed March 8, 2019.

- 25.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Zitvogel L. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy. Annu Rev Immunol 2013;31:51–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet 2017;389:2492–2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmermann S, Peters S, Owinokoko T, Gadgeel SM. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in the management of lung cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2018;(38):682–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 2015;348:124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hugo W, Zaretsky JM, Sun L, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic features of response to anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cell 2016;165:35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2189–2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khalil DN, Smith EL, Brentjens RJ, Wolchok JD. The future of cancer treatment: immunomodulation, CARs and combination immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;13:273–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu LC, Lee YH, Chang CJ, et al. Increased expression of programmed death-ligand 1 in infiltrating immune cells in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues after sorafenib treatment. Liver Cancer 2018:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Yarchoan M, Xing D, Luan L, et al. Characterization of the immune microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:7333–7339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sangro B, Gomez-Martin C, de la Mata M, et al. A clinical trial of CTLA-4 blockade with tremelimumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2013;59:81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Segal NH, Hamid O, Hwu W, et al. 1058PDA phase I multi-arm dose-expansion study of the anti-programmed cell death-ligand-1 (PD-L1) antibody MEDI4736: preliminary data. Ann Oncol 2014;25:iv365. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kudo MMA, Santoro A, et al. Nivolumab in patients with Child-Pugh A advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in the CheckMate 040 study. Abstract presented at: 2018 Annual Liver Meeting; November 9–13, 2018; San Francisco, CA. Abstract LB-2. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, et al. ; KEYNOTE-224 investigators. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:940–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merck. Merck provides update on KEYNOTE-240, a phase 3 study of KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) in previously treated patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma [press release]. https://investors.merck.com/news/press-release-details/2019/Merck-Provides-Update-on-KEYNOTE-240-a-Phase-3-Study-of-KEYTRUDA-pembrolizumab-in-Previously-Treated-Patients-with-Advanced-Hepatocellular-Carcinoma/default.aspx. Accessed March 2, 2019.

- 39.Kelley RK, Abou-Alfa GK, Bendell JC, et al. Phase I/II study of durvalumab and tremelimumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): phase I safety and efficacy analyses. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:4073. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stein S, Pishvaian MJ, Lee MS, et al. Safety and clinical activity of 1L atezolizumab + bevacizumab in a phase Ib study in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). J Clin Oncol 2018;36:4074. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pishvaian M, Lee M, Ryoo B, et al. LBA26 updated safety and clinical activity results from a phase Ib study of atezolizumab+ bevacizumab in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Ann Oncol 2018;29:mdy424. Abstract 028. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ikeda M, Sung MW, Kudo M, et al. A phase 1b trial of lenvatinib (LEN) plus pembrolizumab (PEM) in patients (pts) with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC). J Clin Oncol 2018;36:4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greten TF, Duffy AG, Korangy F. Hepatocellular carcinoma from an immunologic perspective. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:6678–6685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duffy AG, Ulahannan SV, Makorova-Rusher O, et al. Tremelimumab in combination with ablation in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2017;66:545–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harding JJ, Erinjeri JP, Tan BR, et al. A multicenter pilot study of nivolumab (NIVO) with drug eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization (deb-TACE) in patients (pts) with liver limited hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). J Clin Oncol 2018;36:TPS4146. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nobler MP. The abscopal effect in malignant lymphoma and its relationship to lymphocyte circulation. Radiology 1969;93:410–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ehlers G, Fridman M. Abscopal effect of radiation in papillary adenocarcinoma. Br J Radiol 1973;46:220–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Postow MA, Callahan MK, Barker CA, et al. Immunologic correlates of the abscopal effect in a patient with melanoma. N Engl J Med 2012;366:925–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andtbacka RH, Kaufman HL, Collichio F, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec improves durable response rate in patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2780–2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tesniere A, Schlemmer F, Boige V, et al. Immunogenic death of colon cancer cells treated with oxaliplatin. Oncogene 2010;29:482–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michaud M, Martins I, Sukkurwala AQ, et al. Autophagy-dependent anticancer immune responses induced by chemotherapeutic agents in mice. Science 2011;334:1573–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qin S, Cheng Y, Liang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of the FOLFOX4 regimen versus doxorubicin in Chinese patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a subgroup analysis of the EACH study. Oncologist 2014;19:1169–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Casares N, Pequignot MO, Tesniere A, et al. Caspase-dependent immunogenicity of doxorubicin-induced tumor cell death. J Exp Med 2005;202:1691–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dhanasekaran R, Kooby DA, Staley CA, Kauh JS, Khanna V, Kim HS. Comparison of conventional transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and chemoembolization with doxorubicin drug eluting beads (DEB) for unresectable hepatocelluar carcinoma (HCC). J Surg Oncol 2010;101:476–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]