Abstract

Spondylodiscitis (SD) is one of the main causes of back pain. Although the low mortality, high morbidity is related to spondilodiscitys, leading spine instability, chronic pain or neurological deficit. Diagnostic imaging plays a primary role in diagnosing spondylodiscitis. However different accuracy is highlighted by different diagnostic tool, depending also on timing of disease which represents a cardinal element for the phenotypic manifestation of the disease, beyond spatial resolution and tissue characterization proper of specific modality imaging. Conventional Radiology (CR), Computed Tomography (CT) and MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) all have proven to be of primary importance in the approach to spondylodiscitis, although magnetic resonance imaging has demonstrated the greatest advantage in identifying the disease from its earliest stages, demonstrating high sensitivity and specificity (92% and 96%, respectively). This review focus on the role of different imaging modality in the approach to the spondylodiscitis, also addressing the role of interventional radiology that is pivotal not only for a diagnosis of certainty through biopsy, but also for a minimally-invasive treatment of paravertebral abscesses spondylodiscitis-related. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: spondylodiscitis, spine infection disease, MRI, CT, CR, interventional radiology

Introduction

Spondylodiscitis (SD) is one of the main causes of back pain (1-6). The relative low incidence (5-5.3/106 per year; M>F) is unfortunately increasing as a consequence of wide-spread chronic and degenerative spine pathologies, spinal surgery, use of immunosuppressive therapies, vascular device, or extensive use of intravenous substances of abuse (7-12). SD refers to an infection involving the vertebral bodies (spondylitis) and intervertebral disc (discitis). Though the low mortality (2-4%), SD is related to a high morbidity, leading to spine instability, chronic pain or neurological deficit (13).

Different pathogenic mechanics and pathogens are identified as responsible for SD. Hematogenous diffusion, contamination by contiguity or direct inoculation are the leading mechanism of SD. Hematogenous diffusion is the main cause of SD (60-80%), mainly via arteriosus system. Primary discitis is a typical mechanism of infection only in children due to the high vascularization of the disc, while vascular anastomoses with the intradiscal vessels are involuted in adulthood. Direct inoculation is responsible for the 15-40% of cases, related mainly to spinal procedures, including the minimally invasive ones. Diffusion of the infection by contiguity from adjacent structures, such as abscesses or after aortic grafts, remains an infrequent cause (approximately 3%) (14). Pyogenic [S. aureus (60%), Enterobacter (30%), E. coli, Salmonella, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae (10%)] and granulomatous infection (m. tuberculosis, brucellosis) are differentiated, the latter less frequent. Pyogenic SD mainly involve the lumbar spine (58%), less frequent thoracic (30%) and cervical (11%) spine, reflecting their different vascularization; conversely, tuberculous SD primarily affect the thoracic spine, with an involvement of more than two levels often, a sign characteristic of tuberculous SD compared to the pyogenic ones.

Clinical considerations

Symptoms for SD are often non-specific, as laboratory testing generally used in clinical practice both for diagnosis and follow-up, which unfortunately show only a moderate diagnostic accuracy. Main symptom of SD is pain and, less frequent, fever. Non-specific pain occurs in 90% of cases, often as first symptom. Pain generally worsens during the night, often radiates to the abdomen, lower limbs, scrotum and perineum, and it could be exacerbated by movements (15). Fever can be present in 48% of patients with pyogenic spondylodiscitis and 17% of cases with tuberculous type. Neurological complications occur in approximately 12% of cases, related to spinal cord or nerve root compression, or meningitis. Paraspinal or epidural abscesses is found in 44% of cases of patient with neurological complications. White blood cell counts are often normal and can increase in 35% of patients without exceeding 12,000 cells / mm3 (4). Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) are sensitive markers with low specificity, although the latter is often considered the best marker for follow-up (16). Procalcitonin also is considered a highly specific and sensitive marker for the diagnosis and control of the effectiveness of the treatment, even higher than CRP. Blood cultures could be positive in approximately 50% of cases with hematogenous diffusion. Considering non-specificity of symptoms and laboratory testing, 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Native Vertebral Osteomyelitis in Adults outline specific consideration for a clinical suspicion of SD. Therefore, a progression of nuchal or back pain, or a back pain of recent onset with fever, increase in ESR and CRP and evidence of infection with hematogenous spread or endocarditis, is a strong recommendation for potential SD. Conversely, a patient with fever and neurological symptoms of recent onset, with or without pain, or a patient with nuchal or back pain of recent onset after a recent sepsis from S. aureus infection, is a weak recommendation (17).

Radiology in SD

Cross-sectional imaging (MRI, CT and CR) techniques, gained large application in standard practice, also on spine pathologies (18-26). Diagnostic imaging plays therefore a primary role in diagnosing of spondylodiscitis, advised MRI, CT and CR as first line techniques in the diagnosis, staging and follow-up. However, different techniques have an obvious different capability in detecting specific alteration SD-related. Moreover, timing of the disease represents a cardinal element for the phenotypic manifestation of the disease and thus consequently for the different techniques to detect specific SD findings.

Conventional Radiology (CR)

Conventional radiology is a low sensitive and specific technique (82% and 57%, respectively) (27) especially in the early diagnosis of spondylodiscitis, although conventional x-ray is often used for the first approach to the back pain. Notably, conventional radiology is capable in identifying later bone alterations which can occur from 3-6 weeks after the infection, as subchondral erosion, that is considered the first identifiable CR sign (15). With the progression of disease, some alterations become more evident, with possible fragmentation or erosion of the anterior angle of the vertebral plate, reduction of intervertebral space, loss of physiological lordosis and structural deformity. Later manifestation (about 8-12 weeks after) include reactive sclerosis and bony bridge formation between different soma. In case of effective treatment, the fusion of the vertebral bodies can be appreciated, while in case of ineffective treatment, a complete somatic collapse can occur (fig. 1).

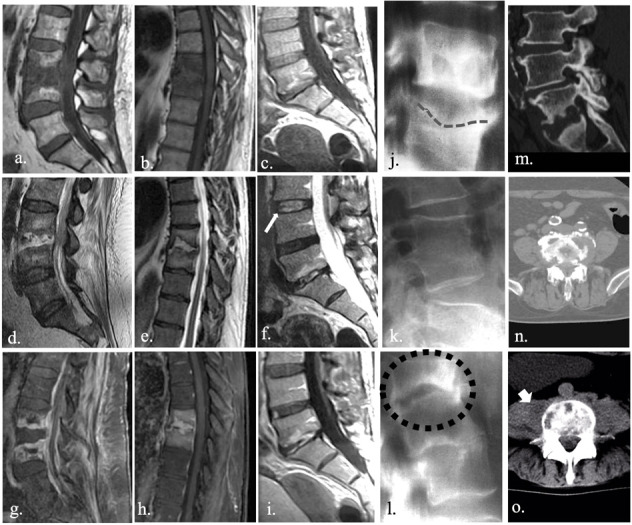

Figure 1.

MRI is an accurate tool in diagnosing spondylodyscitis. Typical presentation includes low T1 (a., b., c.) and high T2 (d., e., f.) signal intensity involving both disc and vertebral endplate. Structural alterations within the disc allow for a loss of typical intranuclear cleft (f., white arrow), which represents normal fibrous tissue within the nucleus polposus. Post-inflammatory vascularization and granulomatous tissue could be responsible for a sever enhancement after injection of contrast media (g., h., i.). Conversly, CR and CT are insensitive especially in the early stages of the infection. First CR sign is represented by subchondral erosion (j., dashed line), observable from 3-6 weeks after the infection. Fusion of vertebral bodies (k.) or complete somatic collapse (l., blak dots) could be observed in later stages, in case of effective or ineffective treatment, respectively. CT could be useful mainly in estimating the entity of osteolysis (m., n.), allowing also to evaluate the extension to perivertebral tissue (o. large arrow).

Computed Tomography (CT)

CT also is insensitive in detecting early SD alteration. More of SD-related CT-findings occur after 2 weeks from infection, and they could be identified in about one half of the patients. CT, indeed, could be useful mainly in identifying, describing and estimating the extension of osteolysis, or in showing an involvement of paravertebral tissue with a thickening of adipose tissue. However, CT contribution within the diagnostic process is very poor and its role is mainly limited to a preoperative planning of spinal procedures or as an alternative in case of contraindication to MRI (14)(fig. 1).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI, thanks to its excellent soft tissue contrast and multiplanar capability, is the primary imaging tool for a variety of conditions and diseases both for diagnostic and interventional purpose, especially in the neuroradiological field (28-33). Currently, MRI is the gold standard in the diagnosis of SD, with a high sensitivity and specificity (92% and 96%, respectively) especially in the early stages of diseases due to the excellent tissue characterization and ability in identifying bone edema and areas with anomalous vascularization (7, 27). Bone edema, indeed, is observed since the early phase of disease which is characterized by infiltration of inflammatory cells and thus by an increase of extracellular space. Increase in water content determines low T1-signal intensity of bone tissue and hyperintensity on T2-weighted sequences; moreover, highly water content within the disc is responsible for the loss a typical disc appearance known as “intranuclear” cleft (13)(fig. 1). Some authors suggest also high accuracy of high T2 signal intensity of psoas muscles as very-early sign of lumbar SD (34). Moreover, enhancement of disco-somatic structures can be observed in response to inflammatory alterations, potentially extended to adjacent structures. MRI shows high accuracy also in identifying later or post-infection alterations which include replacement of necrotized tissue with vascularized fibrous tissue, yellow marrow transformation, subchondral fibrosis and osteosclerosis.

Since etiologic characterization of SD is crucial for an adequate treatment, MRI could offer some advantages especially in differentiating between non-pyogenic forms (e.g., tubercular or brucellosis SD).

Differential diagnosis

Other conditions can mimic SD radiological feature and symptomatology. Osteochondritis, also known as discovertebritis or aseptic spondylodiscitis, is one of the great mimes of SD. Modic I or vascular pattern, indeed, often observed in presence of degenerative alteration of spine, is characterized by bony inflammation with low T1 and high T2 signal intensity of endplates, similar to SD (7)(fig. 2). Though disc alterations often permit an adequate differentiation, sometime the two forms are overlapped, especially between symptomatic forms, and biopsy remain the main discriminator. Although the poor representation of anatomical details, 18-FDG PET, also as hybrid methods (PET/MRI, mainly) has shown high efficacy in differentiating between degenerative and infectious disease. PET technique, indeed, has shown a good correlation with histological finding of infection severity and with the involvement of extraspinal structures (7). CRMO (Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis) also has to be considered for a proper differential diagnosis of SD. CRMO is a migrant forms characterized by litic lesion with a well-defined sclerotic hem. CRMO often involves different soma with bone edema and vertebral collapse. Spinal involvement is not so rare in CRMO (35)(fig. 3).

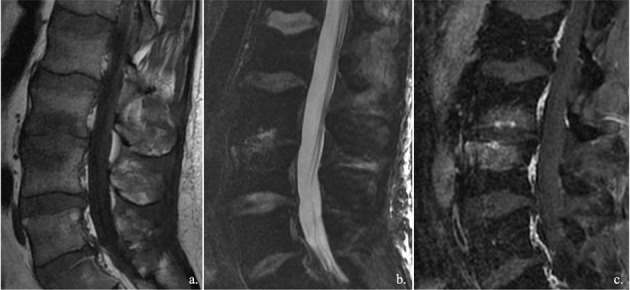

Figure 2.

Osteochondritis, also known as discovertebritis or aseptic spondylodiscitis, is one of the great mimes of spondylodyscitis. Inflammation mainly involved the vertebral endplates, with increase in water content and vascular granulation tissue, and consequently bone edema. Intervetebral disc often is degenerated.

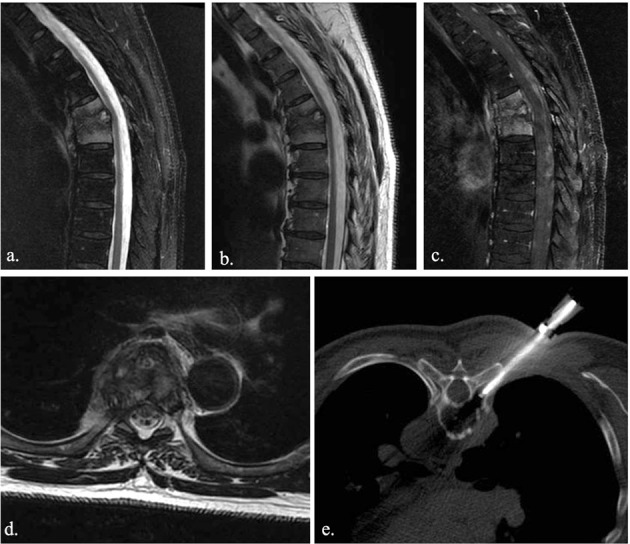

Figure 3.

Spinal involvement in CMRO is rare. Migrant erosion involved different soma with bone edema and vertebral collapse. Radiological evolution can occur within few months (a.-b. diagnostic imaging acquired in March; c.-d. diagnostic imaging acquired in July), with a rapid worsening of clinical status mainly related to severe pain. Bone biopsy (e., f.,) is commonly required in CMRO in order to exclude infection, neoplasia or histiocytosis, since the diagnosis of CRMO is made by exclusion.

Biopsy

Multidisciplinary approach has high sensitivity and specificity in detecting SD. However, identification of the specific pathogen remains the key point for a proper treatment and thus for setting up an adequate antibiotic therapy, especially for atypical or tuberculous pathogens (36). In this regard, blood cultures have a limited role, because of only the 50% of cases results positive if an hematogenous spread, other that they do not always correlate with the pathogen found at site of infection. For these reasons, biopsy plays a crucial role in the etiological diagnosis of SD. Open and percutaneous techniques could be performed, with a higher prevalence for the percutaneous one although the high variability showed in literature, ranging from 36% to 91% (37). CT-guided biopsy is the most performed percutaneous technique, indicated as soon as possible in patients with no neurological deficits, instability/deformity or sepsis. Otherwise, the surgery approach is recommended. Empirical antibiotic therapy is recommended only in high risk patients as with sepsis or medullar compression, neutropenia or in a neurologically compromised patient. A double specimen should be taken for cultural and histologic examinations. If coltural examination is of prior importance for the identification of the specific pathogen, histologic examination could be useful for distinguishing granulomatous forms (38). Potential complications of CT-guided biopsy are vascular or nervous damage, hematoma or non-target biopsy. In order to limit time and radiation dose exposure of procedure and avoid non-target region, lately CT navigation with volumetric acquisition has shown high advantages (39, 40). Specimen could be taken from bone or discal region, with costo-vertebral or transpeduncolar access depending on different thoracic or lumbar target respectively, or instead from paravertebral tissue if involved (fig. 4). Several reasons are responsible for high variability of percutaneous biopsies, as inadequate specimen or representation of pathogen within the specimen, or when an empirical therapy is administered before the biopsy. However, in patient with a non-diagnostic specimen, a second biopsy is recommended when other contraindication are absent.

Figure 4.

Bone biopsy plays a crucial role in the etiological diagnosis of spondylodyscitis. CT-guided biopsy is the most performed percutaneous technique. MRI shows thoracic spondylodyscitis (a., b., c.). A costo-vertebral approach (e.) was preferred in thoracic spine biopsy

As mentioned, the main indication to the “open” biopsy is the presence of severe neurological deficits due to structural damage. Open technique should be recommended also after a second inadequate percutaneous attempt, without further improvement after antibiotic therapy, or when the percutaneous technique is technically contraindicated. The “open” technique has shown an efficacy of about 75%, especially in the diagnosis of lumbar forms. However, diagnostic yield of open technique drops to similar percutaneous technique validity after empirical antibiotic therapy.

Treatment

Goals of the treatment in SD are eradication of the infection, stabilization of spine and recovery of potential neurological deficits. Although no standard therapeutic approach are defined, antibiotic therapy, immobilization of the spine and spinal decompression are of great importance for an effective treatment that allows a complete recovery. Generally, conservative and surgical therapies could be considered. Conservative therapy is often the primary option especially for elderly patients or in patients with a physical decay (41). Antibiotic strategies mainly depend on specific etiological definition. As a general rule, it is advisable to administer intravenous antibiotics for at least 2/4 weeks to improve bioavailability, although the treatment should be more prolonged in high risk patients.

Therapy for tuberculous spondylodiscitis should be carried out for at least 18-24 months to allow a complete healing and avoid recurrence. Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy should be considered in patients with sepsis or fulminant SD. Conversely, surgical approach aims to physically remove the septic focus, allowing also the collection of samples for microbiological testing. Primary advantage offered by surgical approach is the spinal decompression in case medullar extension with stabilization and recovery of the infected column segment. Compared to conservative therapy, this approach allows for safer and faster treatment, with earlier mobilization (42). Recently, new scoring system has been developed to simplify decisional algorithm in order to identify when surgical intervention may be required (43).

Interventional radiology

The interventional radiology plays a key role both in diagnosing and treatment also in SD (44-45).

As mentioned CT-guided biopsy are considered of primary importance in the clinical setting of SD patients. CT, indeed, is a valuable diagnostic tool for the diagnosis and the guidance of interventional procedures in a wide range of organs (46-51). Moreover, interventional approach is of primary importance also for the treatment of psoas muscle abscess, which is a potentially life-threatening infection. Mortality rate in psoas pyogenic abscess ranges from 50% to 100%. Death is usually due to inadequate / delayed treatment, with mortality close to 100% in septic patients. In the acute phase, in the presence of psoas muscle abscess, this procedure has the purpose of draining the collection and possibly injecting local antibiotic. When the abscess is drained, the patient’s pain gradually decreases as the pressure inside the collection decreases with consequent relief of the symptoms. The procedure is performed with aseptic precautions under local anesthesia with the patient usually in a prone position, performed with a CT or a US guide. Contraindications for percutaneous treatment are represented by coagulopathies and lack of patient’s collaboration (52).

Follow-up

The 2015 the American Society of Infectious Diseases (IDSA) guidelines suggest that persistent pain, residual neurological deficits, unchanged or increased inflammation markers and radiographic findings do not necessarily indicate a failure of therapy (17). MRI is not recommended routinely and should not be performed in the follow-up of patients with good clinical-laboratory response, since CRP values have been shown to improve in patients with vertebral infection and are closely related to the clinic. Moreover, MR-signs of inflammation, included post-contrastographic enhancement, could be detected after several time after the infection, even in case of effective therapy (53). In the case of clinical suspicion of treatment failure, systemic follow-up of markers and MRI are recommended to confirm the suspicion and highlights the presence of abscesses or column instability that could benefit from specific treatments. Particular attention during the follow-up of MRI must be paid to the paravertebral and epidural tissues, for possible involvement and therefore progression of the pathology. CT and MRI can highlight severe forms of non-typical inflammation, involvement of two discs or paravertebral extension. CT, compared to MRI, can be useful in distinguishing advanced stages in which bone destruction can be achieved (54).

Conclusion

Multidisciplinary approach is of primary importance in diagnosis and intervention of traumatic, tumoral and infectious MSK diseases (55-59). MRI plays a primary role in diagnosing spondylodiscitis with a high sensitivity and specificity. However, the biopsy currently represents the ultimate diagnostic level, essential for the identification of the specific pathogen responsible of the infection and thus for the setting of a specific therapeutic strategy. MRI is recommended during the follow only with clinical and laboratory findings indicative of ineffective treatment or neurological complication.

Conflict of interest:

Authors declare that they have no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- 1.Bruno F, Smaldone F, Varrassi M, et al. MRI findings in lumbar spine following O2-O3 chemiodiscolysis: A long-term followup. Interv Neuroradiol. 2017;23:444–50. doi: 10.1177/1591019917703784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Splendiani A, Bruno F, Patriarca L, et al. Thoracic spine trauma: advanced imaging modality. Radiol Med. 2016;121:780–92. doi: 10.1007/s11547-016-0657-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perri M, Grattacaso G, di Tunno V, et al. T2 shine-through phenomena in diffusion-weighted MR imaging of lumbar discs after oxygen-ozone discolysis: a randomized, double-blind trial with steroid and O2-O3 discolysis versus steroid only. Radiol Med. 2015;120:941–50. doi: 10.1007/s11547-015-0519-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michelini G, Corridore A, Torlone S, et al. Dynamic MRI in the evaluation of the spine: state of the art. Acta Biomed. 2018;89:89–101. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i1-S.7012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruno F, Palumbo P, Tommasino E, et al. Evaluation of intervertebral disc using T2 mapping sequences in patients undergoing O2-O3 chemiodiscolysis: an instrumental study with clinical correlation. Neuroradiology. 2020;62:55–61. doi: 10.1007/s00234-019-02308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Splendiani A, Bruno F, Marsecano C, et al. Modic I changes size increase from supine to standing MRI correlates with increase in pain intensity in standing position: uncovering the “biomechanical stress” and “active discopathy” theories in low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2019;28:983–92. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-05974-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fahnert J, Purz S, Jarvers JS, et al. Use of Simultaneous 18FFDG PET/MRI for the Detection of Spondylodiskitis. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1396–401. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.171561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cipriani P, Berardicurti O, Masedu F, et al. Biologic therapies and infections in the daily practice of three Italian rheumatologic units: a prospective, observational study. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:251–60. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3444-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giacomelli R, Afeltra A, Alunno A, et al. Guidelines for biomarkers in autoimmune rheumatic diseases - evidence based analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18:93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giacomelli R, Liakouli V, Berardicurti O, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: current and future treatment. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37:853–63. doi: 10.1007/s00296-016-3636-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cipriani P, Di Benedetto P, Ruscitti P, et al. Perivascular Cells in Diffuse Cutaneous Systemic Sclerosis Overexpress Activated ADAM12 and Are Involved in Myofibroblast Transdifferentiation and Development of Fibrosis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:1340–9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salaffi F, Carotti M, Di Carlo M, Farah S, Gutierrez M. Adherence to Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy Administered Subcutaneously and Associated Factors in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2015;21:419–25. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duarte RM, Vaccaro AR. Spinal infection: state of the art and management algorithm. Eur Spine J. 2013;22:2787–99. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2850-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sans N, Faruch M, Lapegue F, Ponsot A, Chiavassa H, Railhac JJ. Infections of the spinal column--spondylodiscitis. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2012;93:520–9. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skaf GS, Domloj NT, Fehlings MG, et al. Pyogenic spondylodiscitis: an overview. J Infect Public Health. 2010;3:5–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gouliouris T, Aliyu SH, Brown NM. Spondylodiscitis: update on diagnosis and management. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(Suppl 3 iii):11–24. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berbari EF, Kanj SS, Kowalski TJ, et al. Executive Summary: 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Native Vertebral Osteomyelitis in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:859–63. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reginelli A, Silvestro G, Fontanella G, et al. Validation of DWI in assessment of radiotreated bone metastases in elderly patients. Int J Surg. 2016;33(Suppl 1):S148–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruno F, Arrigoni F, Palumbo P, et al. New advances in MRI diagnosis of degenerative osteoarthropathy of the peripheral joints. Radiol Med. 2019;124:1121–1127. doi: 10.1007/s11547-019-01003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruno F, Arrigoni F, Palumbo P, et al. The Acutely Injured Wrist. Radiol Clin North Am. 2019;57:943–55. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Orazio F, Splendiani A, Gallucci M. 320-Row Detector Dynamic 4D-CTA for the Assessment of Brain and Spinal Cord Vascular Shunting Malformations. A Technical Note. Neuroradiol J. 2014;27:710–7. doi: 10.15274/NRJ-2014-10096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mariani S, La Marra A, Arrigoni F, et al. Dynamic measurement of patello-femoral joint alignment using weight-bearing magnetic resonance imaging (WB-MRI) European journal of radiology. 2015;84:2571–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Splendiani A, D’Orazio F, Patriarca L, et al. Imaging of postoperative spine in intervertebral disc pathology. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101:75–84. doi: 10.1007/s12306-017-0453-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agostini A, Mari A, Lanza C, et al. Trends in radiation dose and image quality for pediatric patients with a multidetector CT and a third-generation dual-source dual-energy CT. Radiol Med. 2019;124:745–52. doi: 10.1007/s11547-019-01037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zappia M, Maggialetti N, Natella R, et al. Diagnostic imaging: pitfalls in rheumatology. Radiol Med. 2019;124:1167–74. doi: 10.1007/s11547-019-01017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salaffi F, Carotti M, Bosello S, et al. Computer-aided quantification of interstitial lung disease from high resolution computed tomography images in systemic sclerosis: correlation with visual reader-based score and physiologic tests. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:834262. doi: 10.1155/2015/834262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herren C, Jung N, Pishnamaz M, Breuninger M, Siewe J, Sobottke R. Spondylodiscitis: Diagnosis and Treatment Options. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114:875–82. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carotti M, Salaffi F, Di Carlo M, Giovagnoni A. Relationship between magnetic resonance imaging findings, radiological grading, psychological distress and pain in patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Radiol Med. 2017;122:934–43. doi: 10.1007/s11547-017-0799-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Filippo M, Pesce A, Barile A, et al. Imaging of postoperative shoulder instability. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101:15–22. doi: 10.1007/s12306-017-0461-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pogliacomi F, De Filippo M, Paraskevopoulos A, Alesci M, Marenghi P, Ceccarelli F. Mini-incision direct lateral approach versus anterior mini-invasive approach in total hip replacement: results 1 year after surgery. Acta Biomed. 2012;83:114–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zoccali C, Arrigoni F, Mariani S, Bruno F, Barile A, Masciocchi C. An unusual localization of chondroblastoma: The triradiate cartilage; from a case report a reconstructive technique proposal with imaging evolution. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2017;8:S48–s52. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masciocchi C, Arrigoni F, La Marra A, Mariani S, Zugaro L, Barile A. Treatment of focal benign lesions of the bone: MRg-FUS and RFA. Br J Radiol. 2016;89:20150356. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Di Pietto F, Chianca V, de Ritis R, et al. Postoperative imaging in arthroscopic hip surgery. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101:43–49. doi: 10.1007/s12306-017-0459-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ledbetter LN, Salzman KL, Shah LM. Imaging Psoas Sign in Lumbar Spinal Infections: Evaluation of Diagnostic Accuracy and Comparison with Established Imaging Characteristics. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37:736–41. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hospach T, Langendoerfer M, von Kalle T, Maier J, Dannecker GE. Spinal involvement in chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) in childhood and effect of pamidronate. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:1105–11. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spira D, Germann T, Lehner B, et al. CT-Guided Biopsy in Suspected Spondylodiscitis--The Association of Paravertebral Inflammation with Microbial Pathogen Detection. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nam KH, Song GS, Han IH, Choi BK, Cha SH. Diagnostic Value of Biopsy Techniques in Lumbar Spondylodiscitis: Percutaneous Needle Biopsy and Open Biopsy. Korean J Spine. 2011;8:267–71. doi: 10.14245/kjs.2011.8.4.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michel SC, Pfirrmann CW, Boos N, Hodler J. CT-guided core biopsy of subchondral bone and intervertebral space in suspected spondylodiskitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:977–80. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carrafiello G, Fontana F, Mangini M, et al. Initial experience with percutaneous biopsies of bone lesions using XperGuide cone-beam CT (CBCT): technical note. Radiol Med. 2012;117:1386–97. doi: 10.1007/s11547-012-0788-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carrafiello G, Lagana D, Nosari AM, et al. Utility of computed tomography (CT) and of fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) in early diagnosis of fungal pulmonary infections. Study of infections from filamentous fungi in haematologically immunodeficient patients. Radiol Med. 2006;111:33–41. doi: 10.1007/s11547-006-0004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zarghooni K, Rollinghoff M, Sobottke R, Eysel P. Treatment of spondylodiscitis. Int Orthop. 2012;36:405–11. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1425-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Homagk L, Homagk N, Klauss JR, Roehl K, Hofmann GO, Marmelstein D. Spondylodiscitis severity code: scoring system for the classification and treatment of non-specific spondylodiscitis. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:1012–20. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-3936-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Appalanaidu N, Shafafy R, Gee C, et al. Predicting the need for surgical intervention in patients with spondylodiscitis: the Brighton Spondylodiscitis Score (BSDS) Eur Spine J. 2019;28:751–61. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5775-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ierardi AM, Piacentino F, Fontana F, et al. The role of endovascular treatment of pelvic fracture bleeding in emergency settings. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:1854–64. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arrigoni F, Napoli A, Bazzocchi A, et al. Magnetic-resonance-guided focused ultrasound treatment of non-spinal osteoid osteoma in children: multicentre experience. Pediatric radiology. 2019;49:1209–1216. doi: 10.1007/s00247-019-04426-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lagana D, Carrafiello G, Mangini M, et al. Indications for the use of the Amplatzer vascular plug in interventional radiology. Radiol Med. 2008;113:707–18. doi: 10.1007/s11547-008-0306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carrafiello G, Lagana D, Pellegrino C, et al. Ablation of painful metastatic bone tumors: a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2008;6(Suppl 1):S47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carrafiello G, Piffaretti G, Lagana D, et al. Endovascular treatment of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: aorto-uni-iliac or bifurcated endograft? Radiol Med. 2012;117:410–25. doi: 10.1007/s11547-011-0717-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carrafiello G, Mangini M, Fontana F, et al. Suprarenal inferior vena cava filter implantation. Radiol Med. 2012;117:1190–8. doi: 10.1007/s11547-012-0851-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carrafiello G, Ierardi AM, Duka E, et al. Usefulness of Cone-Beam Computed Tomography and Automatic Vessel Detection Software in Emergency Transarterial Embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2016;39:530–7. doi: 10.1007/s00270-015-1213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cazzato RL, Arrigoni F, Boatta E, et al. Percutaneous management of bone metastases: state of the art, interventional strategies and joint position statement of the Italian College of MSK Radiology (ICoMSKR) and the Italian College of Interventional Radiology (ICIR) Radiol Med. 2019;124:34–49. doi: 10.1007/s11547-018-0938-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arrigoni F, Bruno F, Zugaro L, et al. Developments in the management of bone metastases with interventional radiology. Acta Biomed. 2018;89:166–74. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i1-S.7020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dave BR, Kurupati RB, Shah D, Degulamadi D, Borgohain N, Krishnan A. Outcome of percutaneous continuous drainage of psoas abscess: A clinically guided technique. Indian J Orthop. 2014;48:67–73. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.125506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cottle L, Riordan T. Infectious spondylodiscitis. J Infect. 2008;56:401–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foreman SC, Schwaiger BJ, Meyer B, et al. Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Parameters Associated with Poor Clinical Outcome in Spondylodiscitis. World Neurosurg. 2017;104:919–26 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.05.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barile A, Conti L, Lanni G, Calvisi V, Masciocchi C. Evaluation of medial meniscus tears and meniscal stability: weightbearing MRI vs arthroscopy. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:633–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruscitti P, Cipriani P, Liakouli V, et al. Subclinical and clinical atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis: results from the 3-year, multicentre, prospective, observational GIRRCS (Gruppo Italiano di Ricerca in Reumatologia Clinica e Sperimentale) study. Arthritis research & therapy. 2019;21:204. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1975-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruscitti P, Cipriani P, Masedu F, et al. Increased Cardiovascular Events and Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: 1 Year Prospective Single Centre Study. PloS one. 2017;12:e0170108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zappia M, Castagna A, Barile A, Chianca V, Brunese L, Pouliart N. Imaging of the coracoglenoid ligament: a third ligament in the rotator interval of the shoulder. Skeletal radiology. 2017;46:1101–1111. doi: 10.1007/s00256-017-2667-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]