Abstract

Forced expiratory time (FET) is a spirometrically derived variable thought to reflect lung function, but its physiological basis remains poorly understood. We developed a mathematical theory of FET assuming a linear forced expiratory flow-volume profile that terminates when expiratory flow falls below a defined detection threshold. FET is predicted to correlate negatively with both FEV1 and FVC if variations in the rate of lung emptying (relative to normal) among individuals in a population exceed variations in the amount of lung emptying. We retrospectively determined FET pre- and postmethacholine challenge in 1,241 patients (818 had normal lung function, 137 were obstructed, and 229 were restricted) and examined its relationships to spirometric and demographic variables in both hyperresponsive and normoresponsive individuals. Mean FET was 9.6 ± 2.2 s in the normal group, 12.3 ± 3.0 s in those with obstruction, and 8.8 ± 1.9 s in those with restriction. FET was inversely related to FEV1/FVC in all groups, negatively related to FEV1 in the obstructed patients, and positively related to FVC in both the normal and restricted patients. There was no relationship with methacholine responsiveness. Overall, our theory of the relationship between FET to the spirometric indices is supported by these findings and potentially explains how FET is affected by sex, age, smoking status, and possibly body mass index.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Forced expiratory time (FET) has long been felt to reflect important physiological information about lung function but exactly how has never been clear. Here, we use a model analysis to assess the contributions of airway narrowing versus airway closure to FET in a population of individuals and find support for the theory that FET correlates positively with FEV1 if the amounts of lung emptying over a forced expiration vary from predicted values more than variations in the rates of lung emptying, whereas the correlation is negative in the opposite case.

Keywords: airway closure, airway narrowing, forced expiratory time, methacholine challenge, spirometry

INTRODUCTION

The two primary lung function parameters derived from conventional spirometry are the volume of gas expired in the first second of a vital-capacity forced expiration (FEV1) and the forced vital capacity (FVC) itself (1–3). These two parameters together convey most diagnostic information used clinically. Nevertheless, there are many other ways of extracting information about the emptying rate and capacity of the lung from the forced expiratory volume-time profile. One that has periodically attracted attention, since its introduction ∼50 years ago, is the time required to completely empty the lungs. This is known as forced expiratory time (FET) (4, 5), and it conceivably represents a combination of the rate and capacity information embodied, respectively, in FEV1 and FVC (6). The clinical utility of FET, however, remains unclear despite a resurgence of interest in the parameter (7–10).

Intuition suggests that obstructive lung disease should lengthen FET due to a reduced rate of lung emptying (FEV1) in the face of a relatively preserved emptying capacity (FVC). Some findings support this hypothesis, such as an increase in FET with age and a slight decrease in nonsmokers compared with the general population (9). On the other hand, this notion is contradicted by a report that a positive methacholine challenge test is associated with a reduced FET at baseline (7). Such a finding could have been due to expiration ending early due to closure of small airways since enhanced airway closure and gas trapping is associated with increased airway secretions in inflammatory lung diseases (11, 12).

The above considerations imply the existence of two competing phenomena at play in the obstructed lung—airway narrowing that lengthens the duration of expiration and airway closure that terminates it prematurely. The overall effect on FET is presumably determined by which of these two phenomena is the more dominant, something that is likely highly variable among subjects. An additional complication, however, is provided by the question of exactly when expiration ends, since this is necessarily defined as the point at which expiratory flow falls to undetectable levels. The possibility exists that unexpired gas in the lungs could continue to exit below the level of detection if the subjects were able to continue expiratory efforts for long enough. The goal of the present study was to examine how these various factors might influence FET derived from spirometry one way or another and to evaluate their effects in a population of subjects both pre- and postmethacholine challenge.

METHODS

Theory

The flow-volume (FV) profile during forced expiration from total lung capacity (TLC) manifests in a variety of shapes reflective of various lung diseases. To a first approximation, however, the FV profile can be considered linear, in which case

| (1) |

where expiratory flow is defined as being negative, and V(t) is defined as being zero at residual volume. The parameter τ is a time constant that defines how quickly the lungs empty; normal lungs have a small value of τ and thus empty rapidly, whereas τ is large in obstructed lungs that empty more slowly. Eq. 1 predicts that

| (2) |

where V0 is the volume of gas in the lungs (relative to residual volume) at the start of expiration.

The problem with this simple model, however, is that an exponential expiration continues indefinitely at an ever-decreasing rate, which means that FET is infinite. In practice, of course, expiration cannot proceed indefinitely if for no other reason than the subject will eventually need to take another breath. The end of expiration is thus defined as the point at which the subject and/or the measuring apparatus has decided that expiration is complete. At this point, the magnitude of expiratory flow has descended to some detection threshold ε below which it is considered to be effectively zero, even though some measurable volume of gas remains to be expired in the lungs. FET is thus defined as the time, from the beginning of expiration (t = 0), required for the magnitude of flow to descend to ε. Eqs. 1 and 2 show that FET satisfies the condition

| (3) |

giving

| (4) |

A finite value of ε causes FVC to be underestimated relative to its true value by the amount of expirable gas remaining in the lungs at t = FET. This causes the measured value of FVC to be, from Eq. 2,

| (5) |

We show in the appendix that when the variations in τ relative to its normal value in a population of individuals dominate over variations in V0, then FET is expected to correlate negatively with FVC. Conversely, if V0 dominates over τ, then FET and FVC are expected to correlate positively.

The volume of gas that exits the lungs during the first second of a forced expiration (FEV1) is, from Eq. 2,

| (6) |

FET is invariably longer than 1 s, so the presence of a finite flow detection threshold does not impact the determination of FEV1. However, as we show in the appendix, the way that FET varies with FEV1 again depends on whether variations in τ in the population are more or less dominant over variations in V0. Specifically, FET correlates positively with FEV1 if variations in V0 dominate over those in τ, whereas the correlation is negative in the opposite case. In addition, FET is always negatively correlated with the ratio FEV1/FVC.

Finally, airways hyperresponsiveness has the potential to either increase or decrease FET depending on whether its cause is more related to excessive airway narrowing or excessive airway closure, respectively. In the appendix, we show, based on the aforementioned model, that a hyperresponsive individual will experience an increase in FET compared with a normal individual following an airway challenge if the inequality holds for that individual, and vice versa.

Experimental Data

We extracted data from all 1,295 methacholine challenge tests performed at the Mount Sinai Hospital Pulmonary Function Laboratory between May 1, 2008, and August 7, 2013. The Institutional Review Board of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai approved the study with waiver of informed consent (HSM No. 13-00595). Among the studies examined, three had incomplete data, 14 had poor-quality spirometry [not repeatable per American Thoracic Society (ATS) criteria on the majority (>50%) of methacholine dose steps], and 37 were duplicate studies (in which case one study was randomly selected and retained for analysis).

Of the remaining 1,241 studies, 818 were classified as normal [FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC > lower limit of normal (LLN)], 137 as obstructed (FEV1 and FEV1/FVC < LLN), 229 as restricted (FVC < LLN but FEV1/FVC > LLN), 25 as mixed obstructed/restricted (FEV1/FVC < LLN and FVC < LLN), and 32 as unclassifiable. We performed an analysis on the three largest of these groups, which we designate normal, obstructed, and restricted, respectively. The mixed group had too few patients to allow meaningful conclusions to be drawn. Spirometric interpretation was based on an American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) Task Force definition (3), with the caveat that an FVC < LLN can only suggest restriction without confirmation by a reduced TLC. (Note that small airway obstructive syndrome cannot be differentiated from restrictive syndrome without body plethysmography (13), so the latter group could include some from the former group).

Methacholine bronchoprovocation was performed and interpreted per ATS protocol (in effect during the study period) (1). The outcome was either positive or negative, with a positive test defined as PC20 (provocative concentration of methacholine causing at least a 20% reduction in FEV1 from baseline) ≤ 16 mg/mL. Currently, both the ATS and ERS recommend reporting methacholine response in terms of dose rather than concentration (14), but only PC20 data were available from the records analyzed. Data were extracted from the pulmonary function database (CareFusion, Vmax) and included demographic and anthropometric indices [age, sex, ethnicity, height, weight, and body mass index (BMI)] and physiological indices (FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC, FET). FEV1 and FVC were expressed as percent predicted values based on the NHANES III reference equations (15). FET was defined as the time interval between the beginning and the end of expiration. The end of expiration was identified by the CareFusion system as the point at which flow reversed direction from expiration to inspiration. Subjects were coached to exhale as forcibly as possible for at least 6 s, which implies that most of them terminated expiratory efforts beyond this point when they sensed that expiration was complete so started to inhale. The time of beginning of expiration was determined from the zero-crossing time of the tangent to the volume-time profile at its point of maximum slope (the back-extrapolation line shown in Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of forced expiratory time (FET) shown as a plot of exhaled volume versus time.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics are used to summarize the basic findings; mean and standard deviation (SD) are used for continuous variables, and n and percentage are used for discrete variables. We calculated Pearson correlation coefficients between baseline spirometry results and FET, with P values calculated from the t distribution. Contrasts across groups of patients are estimated using linear regression of FET on group indicator variables. Methacholine responsiveness of FET was estimated with a fixed-effects linear regression of FET on methacholine dose, an indicator of test result (positive vs. negative) and their interaction applied to the serial measurements obtained during the methacholine challenge.

RESULTS

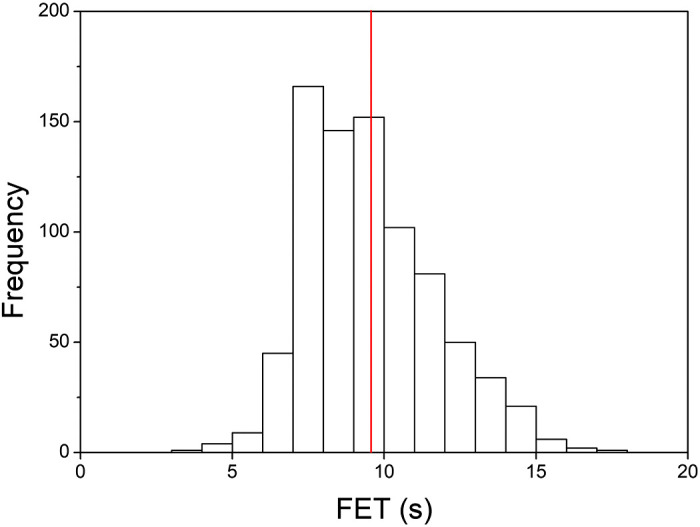

Figure 2 shows the distribution of FET values obtained from the normal group at baseline (i.e., before methacholine challenge). The mean (± SD) FET was 9.6 ± 2.2 s with a fifth percentile of 6.9 s. The means (± SD) FET for the obstructed and restricted groups were 12.3 ± 3.0 s and 8.8 ± 1.9 s, respectively. Table 1 stratifies the results from the normal group based on specific patient characteristics. FET was greatest in males, Caucasians, older patients, and current and former smokers. FET increased with increasing BMI, but the relationship was lost for the group with BMI > 40 kg/m2. For each characteristic, group differences in FET were statistically significant (P < 0.0005). Although 52.3% of the population carried a diagnosis of asthma, only 31.7% had a positive methacholine challenge.

Figure 2.

Distribution of forced expiratory time (FET) from baseline spirometry. The means ± SD FET was 9.6 ± 2.2 s with a fifth percentile of 6.9 s.

Table 1.

FET values for the cohort (n = 818) with normal lung function

| Characteristics | FET, means ± SD |

|---|---|

| Sex* | |

| Female (n = 325) | 8.6 ± 1.7 |

| Male (n = 493) | 10.2 ± 2.2 |

| Ethnicity* | |

| Asian (n = 24) | 9.0 ± 1.9 |

| African American (n = 129) | 8.9 ± 1.9 |

| Hispanic (n = 263) | 9.3 ± 2.0 |

| Caucasian (n = 402) | 9.9 ± 2.3 |

| Age (% of cohort)* | |

| 17–29 (n = 43) | 7.5 ± 1.0 |

| 30–39 (n = 126) | 9.0 ± 1.8 |

| 40–49 (n = 269) | 9.6 ± 2.1 |

| 50–59 (n = 236) | 9.9 ± 2.2 |

| >60 (n = 144) | 10.0 ± 2.3 |

| BMI (% of cohort)* | |

| <25 (n = 161) | 8.9 ± 2.2 |

| 25–29.9 (n = 300) | 9.6 ± 2.2 |

| 30–39.9 (n = 322) | 9.9 ± 2.1 |

| >40 (n = 35) | 9.0 ± 1.6 |

| Smoking status* | |

| Never (n = 427) | 9.2 ± 2.0 |

| Current (n = 38) | 10.0 ± 2.5 |

| Former (n = 235) | 10.1 ± 2.3 |

| Data not available | – |

P < 0.0005. BMI, body mass index; FET, forced expiratory time; SD = standard deviation.

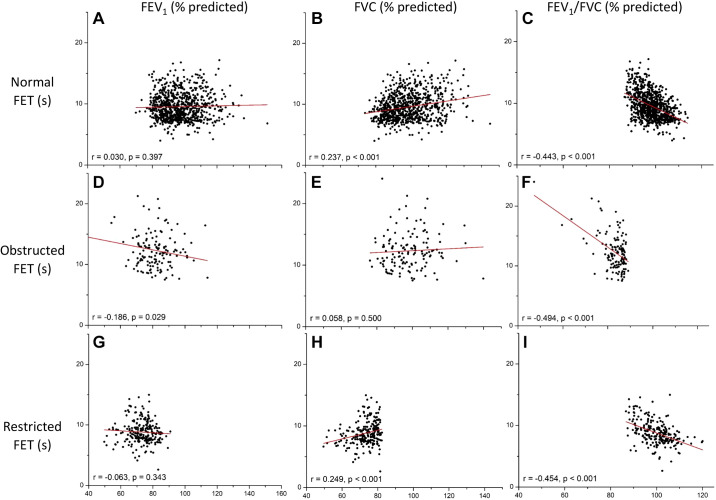

Figure 3 shows the relationships between baseline FET and the percent predicted values of the three spirometric indices FEV1, FET, and FEV1/FVC for the normal, obstructed, and restricted patient groups. We found a strongly significant inverse relationship between FET versus FEV1/FVC for all groups (Fig. 3, right-hand column). FET correlated negatively with FEV1 in the obstructed group, but there was no correlation in either the normal or the restricted group (Fig. 3, left-hand column). FET correlated positively with FVC in both normal and restricted groups, whereas there was no correlation in the obstructed group (Fig. 3, middle column).

Figure 3.

Correlations between forced expiratory time (FET) and first second of a vital-capacity forced expiration (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) (A), FVC (% predicted) (B), and FEV1 (% predicted) (C).

The normal group also exhibited a positive dependence of FET on age, with r = 0.233 (P < 0.001) and a slope of 0.044 s ·yr−1.

Of the 818 normal subjects examined, 598 had a negative methacholine challenge test (not hyperresponsive), whereas 220 had a positive test. In the negative test group, the average value of FET after the last (highest) dose of methacholine was 0.21 s shorter than at baseline, whereas for the positive test group, FET after the last dose was 0.57 s shorter than at baseline. In the methacholine-positive group, the slope of the FET-methacholine dose relationship was −0.001 ± 0.008 s·mL·mg−1 (means ± SE) with a 95% confidence interval of −0.016 to ± 0.015 s·mL·mg−1, P = 0.91. In the methacholine-negative subjects, the slope was +0.006 ± 0.003 s·mL·mg−1 with a 95% confidence interval of −0.001 to +0.002 s·mL·mg−1, P = 0.094. Taking all subjects together, the decrease in FET was not statistically significant (P = 0.245).

DISCUSSION

We have developed a theory to explain the genesis of the FET based on the balance between two phenomena with opposing effects—airway narrowing that prolongs the duration of expiration and airway closure that shortens it. The theory is based on the assumption that forced expiratory flow is judged to have reached zero when its magnitude descends below a detection threshold ε. This threshold could be determined by the measurement resolution of the spirometer and/or the subject’s own perception of the end of their expiration as well as possible sensations of air hunger, which may influence their motivation to continue expiratory efforts. Since τ in Eq. 1 represents the time taken for of expirable gas to exit the lungs during forced expiration, and the range of normal to pathologic FEV1 is roughly 60%–80% of the expirable volume in the lungs, we may take τ to be on the order of 1 s. In addition, the mean value of FET found in the present study is close to 10 s (Fig. 2), whereas a typical value for V0 is 5 L. Substituting these various values in Eq. 3 gives a value for ε of ∼0.2 mL· s − 1. This is very much less than the spirometer resolution of 25 mL·s − 1 stipulated by the ATS/ERS Task Force (2), suggesting perhaps that ε represents not the flow detection threshold of the measuring equipment but rather the detection threshold of the subjects themselves.

General support for our theory is provided by the finding of a negative correlation between FET and FEV1/FVC for all three subject groups (Fig. 3, right-hand column), since this is predicted to always be the case (Eq. A12). More quantitative support for the theory, however, is provided by the magnitudes of the positive correlations between FET and both FVC and FEV1, as follows.

First, our theory predicts that FET will be negatively correlated with FVC if variations in the rate of lung emptying between individuals in the population are greater than variations in the amount of lung emptying (Eq. A4), whereas the correlation will be positive if the reverse applies (Eq. A5). Our findings indicate the latter to be the case in the normal group (Fig. 3B). The slope of the relationship between FET and FVC is given by Eq. A5. Using the abovementioned values of τ = 1 s and ε = 0.2 mL·s − 1 along with V0 = 100% predicted, this slope is estimated to be 0.01 s·%−1, which is the same order of magnitude of the observed slope of 0.04 s·%−1 in Fig. 3B. This finding, therefore, suggests that variations in the amount, rather than the rate, of lung emptying among our normal subjects was paramount in determining variations in FET. This is to be expected given that these subjects were judged to be normal based on their rates of emptying (i.e., normal FEV1) and not their amounts of emptying. Our FET theory is further supported by the other two groups. The restricted group, in which patients were classified as having abnormal amounts of emptying, had an even greater positive slope between FET and FVC of 0.07 s (Fig. 3H), whereas the slope for the obstructed group was not different from zero (Fig. 3E).

Our theory also predicts that FET correlates negatively with FEV1 if variations in the rates of lung emptying dominate over the amounts of emptying (Eq. A8). Again, this theory is supported by the results, since there was a negative correlation for the obstructed group (Fig. 3D) and no correlation for the restricted group (Fig. 3G). There was also no correlation with the normal group (Fig. 3A), but linear regression nevertheless yielded a small positive slope of 0.006 s· %−1. Using the parameter values used earlier in the analysis of FVC, Eq. A9 predicts the value of this slope to be 0.016 s·%−1, which is comparable with the observed slope.

Methacholine challenge in the normal group did not cause a significant decrease in FET. This suggests that air hunger, which one might expect to increase during bronchoconstriction, did not play a physiologically significant role in causing the subjects to terminate expiration. In the only other study to evaluate the relationship between FET and methacholine challenge outcome, Goldstein et al. (7) reported that a short FET (<4 s) was associated with increased likelihood of a positive methacholine test. Their cohort was much smaller than ours (n = 184). Also, the mean FET in their study was <6 s in those with both positive and negative methacholine challenge tests.

The values of FET we found in our normal cohort are comparable with those of previous studies (9, 16). Our values of FET were somewhat greater in males, Caucasians, and older patients (Table 1). The sex difference may partly reflect greater expiratory muscle strength in males leading to greater exhaled volumes accruing over longer times. Kainu et al. (9) also showed a trend toward higher FET values in males, but this was not significant and, in contrast to our cohort, they studied a random population sample that was predominantly female (59%). Our finding of a longer FET in older patients may simply relate to age-related changes in pulmonary mechanics (e.g., decreased elastic recoil pressure) and respiratory muscle strength. Indeed, both FEV1 and FEV1/FVC have been shown to decrease with normal aging (17), although in the present study, the strongest correlation between age and a spirometric parameter was with FVC (r = −0.130). The significant positive association of FET with age also held true in the Kainu study (9), but these investigators did not find a significant relationship between FET and FVC (liters) again possibly reflecting differences between our respective study populations. We currently have no explanation for the ethnic differences.

We also found that FET increased with increasing BMI, as in the study of a somewhat leaner cohort by Kainu et al. (9) who attributed the effect to “altered lung mechanics.” The obese state is characterized by airways dysfunction, particularly of the small airways (18, 19), so our findings may have been a manifestation of small airways obstruction. Curiously, the positive relationship between FET and BMI did not persist in the few severely obese patients (BMI > 40 kg/m2) in our study. In addition, FET was shorter in those who never smoked compared with former and current smokers. Kainu et al. (9) reported similar findings that they attributed to airflow limitation.

Our study has several limitations related to the measurement of FET, which has an intrinsic variability that far exceeds that of other spirometric parameters such as FEV1 and FVC (8). Our laboratory has a strict quality assurance program that includes technicians coaching patients to produce their best efforts for at least 6 s, but coaching intensity is inevitably variable from subject to subject, as is the ability of subjects to respond to the coaching. We therefore cannot guarantee that all subjects performed complete forced expirations (note, however, that the finding of FET < 6 s in a number of the subjects shown in Fig. 3 does not mean these subjects ceased their expiratory efforts early; rather, they achieved their volume plateaus, as shown in Fig. 1, at these early time points). Another source of variability is the lack of guidelines on the acceptability of an FET measurement. Although ATS/ERS standards recommend that back extrapolation should not affect estimates of FVC by more than 5% or 150 mL (2, 20), they do not specifically deal with the determination of FET (Fig. 1). In addition, approximately half of our cohort reported exposure at the World Trade Center disaster, so they may have had small airways disease. Thus, our cohort does not represent the general population even though our findings are still similar to those of Kainu et al. (9) who did study a nonselected population sample.

Our mathematical analysis of FET and its relationship to spirometric parameters also has limitations due to the assumptions that this analysis is based on. To arrive at manageable equations that make specific predictions, we had to invoke a particularly simple model of the forced expiratory process in which lung volume decreases exponentially with time toward residual volume. This model is perhaps defensible on account of the approximately straight relationship between expiratory volume and flow in normal lungs, but in lung disease and following induced bronchoconstriction, it becomes significantly more questionable. Thus, while a qualitative agreement between model prediction and experimental data might support the theory with some degree of confidence, the validity of the quantitative predictions remains more equivocal, which is why we limited our discussion of these predictions to only order-of-magnitude calculations.

In summary, the current study represents the largest analysis to date on spirometrically measured FET in a cohort of predominantly nonsmokers. We have developed a mathematical theory of the determinants of FET based on a simple model of forced expiration that explains the relationship of FET to the spirometric indices FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC. This theory suggests that the effect of methacholine was to induce a greater degree of airway closure compared with prolonging lung emptying in our study population. The theory also offers potential explanations for the way in which FET is affected by sex, age, smoking status, and possibly BMI. This may help clarify the role of FET as yet another spirometric index to complement those already in common clinical use, thereby helping to maximize the diagnostic yield of spirometry itself.

GRANT

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 HL-130847.

DISCLOSURES

J. H.T. Bates is a consultant for Oscillavent, LLC (Iowa), Healthy Design, LLC (Vermont), and Johnson & Johnson. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

G.S.S. and J.H.T.B. conceived and designed research; G.S.S., K.L.O-C., C.B.S., D.J.M., and J.H.T.B. analyzed data; G.S.S., K.L.O.-C., C.B.S., D.J.M., and J.H.T.B. interpreted results of experiments; G.S.S., K.L.O.-C., and J.H.T.B. prepared figures; G.S.S. and J.H.T.B. drafted manuscript; G.S.S., K.L.O.-C., C.B.S., D.J.M., and J.H.T.B. edited and revised manuscript; G.S.S., K.L.O.-C., C.B.S., D.J.M., and J.H.T.B. approved final version of manuscript.

APPENDIX

From Eqs. 1–5, and noting that both V0 and τ are variables, the differential of FVC is

| (A1) |

Similarly, from Eq. 5,

| (A2) |

Equations A1and A2 then give

| (A3) |

Changes in this ratio can arise as result of changes in τV0. When the changes in τ dominate over the changes in V0 (i.e., ), then

| (A4) |

which is invariably negative because ε is extremely small, so we expect , which means that . This situation pertains when the individuals in a population vary more in the rates at which their lungs empty during a forced expiration compared with the total amounts by which their lungs empty (both rates and amounts being expressed as % predicted). Conversely, if V0 dominates over τ in Eq. A3 (i.e., ), then

| (A5) |

which is always positive.

From Eq. 6, the differential of FEV1 is

| (A6) |

so

| (A7) |

As with FVC above, the way that FET varies with FEV1 depends on whether changes in τ in the population in question dominate over changes in V0, or vice versa. In the case that , Eq. A7 becomes

| (A8) |

which, as with Eq. A4 above, is invariably negative.

Conversely, when , Eq. A7 becomes

| (A9) |

which is always positive.

The rate of change of FEV1 with respect to FVC is given by the ratio of Eq. A6 and to Eq. A1, thus:

| (A10) |

the differential of which is

| (A11) |

Accordingly,

| (A12) |

The numerator of Eq. A12 is always positive, whereas the terms in the denominator are both always negative. This means that FET is always negatively correlated with the ratio FEV1/FVC.

In the case of airway narrowing, Eq. 4 shows, for fixed values of ε and V0, that

| (A13) |

which, as we showed above, is invariably positive. In the case of airway closure, Eq. 4 shows, for a fixed value of τ, that

| (A14) |

which is always negative. The relative influences on FET of narrowing versus closure are given by the relative magnitudes of Eq. A13 versus Eq. A14, respectively. Specifically, a hyperresponsive individual will experience an increase in FET compared with a normal individual following an airway challenge if the inequality holds for that individual, and vice versa.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crapo RO, Casaburi R, Coates AL, Enright PL, Hankinson JL, Irvin CG, MacIntyre NR, McKay RT, Wanger JS, Anderson SD, Cockcroft DW, Fish JE, Sterk PJ. Guidelines for methacholine and exercise challenge testing-1999. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161: 309–329, 2000. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.ats11-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, Jensen R, Johnson DC, MacIntyre N, McKay R, Navajas D, Pedersen OF, Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Wanger J; ATS/ERS Task Force. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 26: 319–338, 2005. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, Crapo RO, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, Hankinson J, Jensen R, Johnson DC, MacIntyre N, McKay R, Miller MR, Navajas D, Pedersen OF, Wanger J. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J 26: 948–968, 2005. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enright P, Vollmer WM, Lamprecht B, Jensen R, Jithoo A, Tan W, Studnicka M, Burney P, Gillespie S, Buist AS. Quality of spirometry tests performed by 9893 adults in 14 countries: the BOLD Study. Respir Med 105: 1507–1515, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schapira RM, Schapira MM, Funahashi A, McAuliffe TL, Varkey B. The value of the forced expiratory time in the physical diagnosis of obstructive airways disease. JAMA 270: 731–736, 1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03510060077036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cochrane GM, Benatar SR, Davis J, Collins JV, Clark TJ. Correlation between tests of small airway function. Thorax 29: 172–178, 1974. doi: 10.1136/thx.29.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein MF, Veza BA, Lauf-Goldstein A, Dvorin DJ, Dunsky EH, Belecanech GA. Forced expiratory time and bronchial hyperresponsiveness to methacholine. J Asthma 39: 143–150, 2002. doi: 10.1081/jas-120002195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kainu A, Lindqvist A, Sarna S, Sovijärvi A. Intra-session repeatability of FET and FEV6 in the general population. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 28: 196–201, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2008.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kainu A, Lindqvist A, Sarna S, Sovijärvi A. Spirometric and anthropometric determinants of forced expiratory time in a general population. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 28: 38–42, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2007.00771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Straus SE, McAlister FA, Sackett DL, Deeks JJ; CARE-COAD2 Group. Accuracy of history, wheezing, and forced expiratory time in the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Gen Intern Med 17: 684–688, 2002. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.20102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundblad LK, Thompson-Figueroa J, Allen GB, Rinaldi L, Norton RJ, Irvin CG, Bates JH. Airway hyperresponsiveness in allergically inflamed mice: the role of airway closure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 768–774, 2007. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1410OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagers S, Lundblad LK, Ekman M, Irvin CG, Bates JH. The allergic mouse model of asthma: normal smooth muscle in an abnormal lung? J Appl Physiol (1985) 96: 2019–2027, 2004. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00924.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chevalier-Bidaud B, Gillet-Juvin K, Callens E, Chenu R, Graba S, Essalhi M, Delclaux C. Non specific pattern of lung function in a respiratory physiology unit: causes and prevalence: results of an observational cross-sectional and longitudinal study. BMC Pulm Med 14: 148, 2014. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coates AL, Wanger J, Cockcroft DW, Culver BH; Bronchoprovocation Testing Task Force: Kai-Håkon C, Diamant Z, Gauvreau G, Hall GL, Hallstrand TS, Horvath I, de Jongh FHC, Joos G, Kaminsky DA, Laube BL, Leuppi JD, Sterk PJ. ERS technical standard on bronchial challenge testing: general considerations and performance of methacholine challenge tests. Eur Respir J 49: 1601526, 2017. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01526-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159: 179–187, 1999. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai AG, Christie JD, Gaughan CA, Palma WR Jr, Margolis ML. Change in forced expiratory time and spirometric performance during a single pulmonary function testing session. Respir Care 51: 246–251, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaz Fragoso CA, Gill TM. Respiratory impairment and the aging lung: a novel paradigm for assessing pulmonary function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 67: 264–275, 2012. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapman DG, Irvin CG, Kaminsky DA, Forgione PM, Bates JH, Dixon AE. Influence of distinct asthma phenotypes on lung function following weight loss in the obese. Respirology 19: 1170–1177, 2014. doi: 10.1111/resp.12368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skloot G, Schechter C, Desai A, Togias A. Impaired response to deep inspiration in obesity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 111: 726–734, 2011. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01155.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Culver BH, Graham BL, Coates AL, Wanger J, Berry CE, Clarke PK, Hallstrand TS, Hankinson JL, Kaminsky DA, MacIntyre NR, McCormack MC, Rosenfeld M, Stanojevic S, Weiner DJ; ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Pulmonary Function Laboratories. Recommendations for a standardized pulmonary function report. An Official American Thoracic Society Technical Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 196: 1463–1472, 2017. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201710-1981ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]