Abstract

The obesity epidemic is causing a rise in asthma incidence due to the appearance of an obesity-specific late-onset nonallergic (LONA) phenotype. We investigated why only a subset of obese participants develop LONA asthma by determining how obesity, both alone and in combination with LONA asthma, affects the volume dependence of respiratory system impedance. We also determined how obesity and asthma affect impedance during and following challenge with the PC20 dose of methacholine. We found during passive exhalation that all obese participants, in contrast to lean controls and lean asthmatics, experienced similarly profound elevations in lung elastance as they approached functional residual capacity. We also found, however, that the LONA asthmatics had a greater negative dependence of airway resistance on lung volume over the middle of the volume range compared with the other groups. Methacholine challenge with the PC20 dose led to comparable changes in respiratory system impedance in the four study groups, but the doses themselves were substantially lower in both obese and lean asthmatic participants compared with obese and lean controls. Also, the obese LONA asthmatics had higher breathing frequencies and lower tidal volumes postchallenge compared with the other participants. Taken together, these results suggest that all obese individuals experience substantial lung collapse as they approach functional residual capacity, presumably due to the weight of the chest wall. It remains unclear why obese LONA asthmatics are hyperresponsive to methacholine while obese nonasthmatic individuals are not.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Why only a subset of severely obese subjects develop late-onset nonallergic (LONA) asthma remains unknown, although it is widely assumed that compression of the lungs by the chest wall is somehow involved. We show that lung compression is common to obese individuals both without asthma and with LONA asthma but that those with LONA asthma may have increased airway wall compliance and possibly also a reduced ability to recruit collapsed lung.

Keywords: airway resistance, airway wall compliance, mathematical model, respiratory system impedance

INTRODUCTION

The public health burden of asthma in the U.S. has increased due to the dramatic rise in obesity in recent decades. Indeed, it is estimated that over 600 million people worldwide now suffer from obesity (1). Although a worsening of asthma severity in this context (2) is perhaps to be expected given that morbid obesity exacerbates a wide range of human pathologies, the incidence of asthma has also increased. This is due in large part to the appearance of an asthma phenotype that appears later in life, does not involve the Th2-type inflammation typical of allergic asthma, and resolves when patients lose weight (3). The pathophysiology underlying this late-onset nonallergic (LONA) form of obese asthma remains poorly understood, but it is tempting to think that it could involve the chronic lung compression caused by the excessive weight of the obese chest wall. This in turn could lead to airways hyperresponsiveness, a hallmark feature of asthma and something that is known to increase dramatically when lung volume descends below normal functional residual capacity (FRC) (4).

On the other hand, mass loading of the lungs by the chest wall is a feature of obesity in general, yet only a subset of severely obese individuals develops LONA asthma. The pathophysiology of this obesity-specific disease would thus seem to involve more than just reduced lung volume. We recently proposed (5) that the additional factor operative in LONA asthmatics could be higher than average airway wall compliance. This would predispose them to enhanced airway narrowing, or even complete collapse, at the depressed lung volumes characteristic of obesity.

The goal of the present study was to test this hypothesis by determining how obesity, both alone and in combination with LONA asthma, affects the volume dependence of airway resistance and respiratory elastance as evaluated from forced oscillation measurements of respiratory system impedance. We also measured impedance during and following methacholine challenge to characterize airways responsiveness in obese LONA asthma in comparison with obese nonasthma as well as in lean participants both with and without asthma. We used respiratory system impedance for these purposes because of the possibility it provides for interpretation in terms of structural models of the lung, the parameters of which can then be conveniently related to quantities of physiological interest (6).

METHODS

Details of baseline lung function testing and demographics have described in a previous publication (7). Briefly, spirometry and lung volumes were measured (Medgraphics Platinum Elite body plethysmograph, Saint Paul, MN) according to American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society guidelines (8, 9). Methacholine challenge testing, assessed by spirometry, was performed according to the 1999 ATS guidelines using the 2-min tidal breathing protocol (8), administering a maximum concentration of methacholine of up to 16 mg/mL for participants with asthma, and up to 64 mg/mL for controls. We used the same participants in the present study as in this previous publication, with small differences in the numbers per group due to a participant failing to return for the second study visit at which the oscillometry measurements were made.

Participants

The study protocol was approved by the University of Vermont Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study groups were Lean Control (n = 10), Lean Asthma (n = 10), Obese Control (n = 10), and Obese LONA Asthma (n = 11). Inclusion criteria were as follows: Obese LONA asthma: physician diagnosis of asthma at age ≥18 yr, body mass index (BMI) ≥35 kg/m2, ages 35–55 yr, serum IgE <100 IU/ml (10); Obese Control: no history of asthma, BMI ≥35 kg/m2, ages 35–55 yr, serum IgE <100 IU/ml; Lean Control: no history of asthma, BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, ages 35–55 yr, serum IgE <100 IU/ml; and Lean Asthma: physician diagnosis of asthma at age <18 yr, BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, ages 18–55 yr, serum IgE ≥100 IU/ml. The original protocol included only lean allergic asthmatics ages 35–55 yr, but because of difficulty recruiting such participants, the eligibility criteria were modified to include younger participants. Participants with forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) <60% predicted, other forms of lung disease, pregnancy, and ≥20 pack-years smoking history were excluded. Demographic and spirometry data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and lung function data for the 4 study groups

| Lean Control | Lean Asthma | Obese Control | LONA Obese Asthma | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/F | 3/7 | 2/8 | 1/6 | 2/6 | 0.88 |

| Age, yr | 42.4 ± 5.9 | 27.0 ± 7.8 | 43.0 ± 8.0 | 44.0 ± 7.6 | <0.01 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.5 ± 1.5 | 23.3 ± 1.5 | 46.4 ± 2.9 | 44.1 ± 9.3 | <0.01 |

| FEV1, % | 98.2 ± 9.2 | 89.4 ± 17.5 | 99.0 ± 12.9 | 84.4 ± 13.8 | 0.11 |

| FVC, % | 103.8 ± 5.4 | 99.0 ± 15.4 | 96.0 ± 11.6 | 82.8 ± 8.2 | <0.01 |

| RV, % | 124.1 ± 29.7 | 135.1 ± 32.2 | 99.1 ± 38.3 | 100.8 ± 29.5 | 0.07 |

| TLC, % | 102.4 ± 8.6 | 99.1 ± 14.4 | 97.3 ± 14.3 | 90.8 ± 8.2 | 0.22 |

| FRC, % | 93.7 ± 22.7 | 99.3 ± 10.3 | 74.3 ± 13.7 | 76.6 ± 17.3 | <0.01 |

| ERV, % | 67.8 ± 37.6 | 64.2 ± 26.2 | 40.5 ± 45.3 | 33.0 ± 28.6 | 0.11 |

| PC20, mg/ml | 64 (22.2-64) | 2.8 (0.14–12.8) | 64 (64) | 1.47 (0.03–13.3) | <0.01 |

Values shown are means ± SD for normally distributed quantities, and median (range) for nonnormally distributed quantities. LONA, late-onset nonallergic; M/F, male/female; BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced lung capacity; TLC, total lung capacity; PC20, concentration inducing a 20% fall in FEV1 from baseline; RV, residual volume; ERV, expiratory reserve volume.

Conventional Methacholine Testing

Participants underwent conventional methacholine aerosol challenge on their first study visit to establish their PC20 to methacholine (the concentration inducing a 20% fall in FEV1 from baseline). Methacholine challenge testing, assessed by spirometry (Medgraphics Platinum Elite, Saint Paul, MN), was performed according to the 1999 ATS guidelines using the 2-min tidal breathing protocol (8), administering a maximum concentration of methacholine of up to 16 mg/mL for participants with asthma and up to 64 mg/mL for controls. Testing was terminated when a participant reached either their PC20 concentration or the maximum concentration stipulated above. The highest concentrations received by the lean and obese controls were significantly greater (P < 0.05 with post hoc comparison with Bonferroni correction) than those of both the lean and obese asthmatic participants (Table 1).

Oscillometry

At least 1 wk after the first visit the participants returned for further noninvasive assessment of lung physiology by oscillometry. The input impedance of the respiratory system (Zrs) was measured using a modified flexiVent ventilator (Scireq, Montreal, Canada). The usual piston-cylinder assembly employed for use with small experimental animals was replaced by a custom-designed assembly consisting of a 100-mL cylinder that connected directly to a heated pneumotachograph (3813 series, Hans Rudolph, Kansas City, MO) for measurement of mouth flow () and a piezoresistive pressure transducer (SC-24, Scireq, Montreal, Canada) for measurement of airway opening pressure (Pao). A lateral pathway to atmosphere between the piston-cylinder assembly and the site of and Pao measurement allowed the participant to breath normally while flow oscillations were being applied. To prevent all the flow oscillations from the piston simply exiting the system through the expiratory pathway, we connected to the outflow port a partial barrier to flow having a flow-dependent resistance of 1.2 + 63.0 × flow (L·s−1), the resistance units being cmH2O·s·L−1. This resistance presented a nonburdensome load to the participant’s breathing while also presenting a similar impediment to the flow oscillations to force enough oscillatory power to enter the lungs so that the impedance of the respiratory system could be reliably identified.

To assess airway wall stiffness, participants were instructed to take a maximal inspiration while on the mouth piece of the oscillometry system. During oscillometry measurements, the participants supported their cheeks with their hands, although some found this difficult due to body habitus, in which case a member of the research team performed cheek support with their own hands by standing behind the participant. When participants indicated to the operator with a finger movement that their lungs were full, the operator connected a stopper with a narrow orifice to the expiratory port of the system while instructing the participants to relax their respiratory muscles and allow expiration to occur passively, similar to the maneuver recently published by Nilsen et al. (11). The orifice resistance was nonlinear with constant and flow-dependent coefficients of ∼4 cmH2O·s·L−1 and 70 cmH2O·s2·L−2, which slowed the course of expiration such that it occupied most of the 16-s data collection period. Just before the beginning of expiration the ventilator piston began 16 s of oscillatory motion that resulted in the application of multifrequency forced oscillations in flow to be applied to the lungs so that impedance could be monitored continuously (see below). Not all participants found it easy to relax their respiratory muscles fully throughout the 16-s oscillation period, but it was a skill that developed with practice. Accordingly, we had each participant try three to four dummy runs at the maneuver before collecting data. Between three and six repeats of the maneuver with data collection were then performed, with 1–2 min of rest between each. We retained for analysis the maneuver that had the largest change in lung volume over the 16-s measurement period, our assumption being that this represented the most successful attempt each participant made at the relaxed expiration maneuver.

After completion of the relaxed expiration maneuver, we assessed the physiological signature of airways responsiveness in the participants by administering a 4.5-min challenge with continuous methacholine aerosol at the maximum concentration that had been administered during visit 1. Pilot testing had shown this dosing produced a similar change in spirometry to that produced by escalating doses of methacholine during the conventional challenge. Methacholine aerosol from an ultrasonic nebulizer (Hudson RCI, Teleflex Medical, Westmeath, Ireland) was directed into the breathing circuit at a point distal to the bacterial filter so that respiratory system impedance could be measured both during and following methacholine delivery. Oscillometry was performed throughout the methacholine challenge and for 3.5 min immediately afterwards for a total of 8 min.

Analysis of Oscillometry Data: Passive Expiration

The flow oscillations applied during relaxed expirations were comprised of five sinusoidal components having frequencies at 4, 6, 10, 14, and 22 Hz (these frequencies are noninteger multiples of each other to minimize harmonic cross talk) with roughly equal amplitudes at each frequency. This signal has a fundamental frequency of 2 Hz and thus a period of 0.5 s, so it comprised 32 repeats of the same 0.5-s signal. Respiratory system impedance could thus be followed throughout expiration with a high temporal resolution of 0.5 s. Because of the high-resistance pathway at the expiratory port the lungs emptied much more slowly than normal but reached FRC by the end of the 16-s oscillatory period. Airway opening pressure (Pao) and flow () were anti-alias filtered at 30 Hz (6-pole Bessel low-pass filter) and sampled continuously at 256 Hz throughout the 16-s oscillations and retained for analysis.

The Pao(t) and (t) signals were analyzed using custom-designed software. The signals were first low-pass filtered to isolate their spontaneous breathing waveforms [Pao,spon(t) and (t), respectively] from the imposed oscillations [Pao,osc(t) and (t), respectively]. This was done by convolving the signals with a series of finite windows of unity area, the window lengths equaling the periods of the various frequencies of the individual imposed oscillations. The oscillatory components were then determined as Pao,osc(t) = Pao(t) − Pao,spon(t) and (t) = (t) − (t).

Pao,osc(t) and (t) were then analyzed in 0.5-s windows that overlapped by 50%. Zrs(f) at each of the five frequencies was determined for each window by calculating the fast Fourier transform of Pao,osc(t) and (t) [denoted Pao,osc(f) and (f), respectively, where is frequency in Hz] and then computing their ratio at each frequency. That is,

| (1) |

where f = 4, 6, 10, 14, and 22 Hz and R(f) and X(f) are the real and imaginary parts, respectively, of impedance (also referred to as resistance and reactance, respectively). The five values of R(f) and X(f) determined in this way were then simultaneously fit with a single-compartment model of the respiratory system, which has impedance (Zmod−1) given by

| (2) |

Rrs is respiratory system resistance, which, over the frequency range 4–22 Hz, approximates the overall flow resistance of the airway tree (12) because the resistance of the lung tissues over this range is negligible and the contribution from the chest wall tissues is small and approximately constant (6). Irs and Ers are respiratory inertance and elastance, respectively. Values for Rrs, Ers, and Irs were determined by fitting Eq. 2 to Zrs(f) by multiple linear regression within each window, yielding time courses for all three parameters over the 16-s measurement period, that is, Rrs(t), Ers(t), and Irs(t), respectively. At the same time, the change in lung volume relative to total lung capacity (TLC) was computed as

| (3) |

Finally, Vspon(t) was normalized to begin at 1.0 and end at 0 over the 16-s measurement period, and Rrs(t), Ers(t), and Irs(t) were resampled to each have 1,000 points equally spaced in volume, so that the volume dependencies of Rrs(t), Ers(t), and Irs(t) for all participants within each group could be averaged.

Analysis of Oscillometry: Methacholine Challenge

During the 4.5 min of methacholine aerosolization and the 3.5 min immediately afterwards an oscillating flow of 8-s duration was applied four times per minute (every 15 s) to the lungs by the ventilator piston. The flow oscillations were comprised of 6 mutually prime frequency components at 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, and 19 Hz with roughly equal amplitudes at each frequency, creating a signal with a period of 1.0 s that repeated itself eight times. This longer period compared with the relaxed expiration measurements (see above) was used because we did not need to track such rapid changes with methacholine challenge as compared with relaxed expiration. It thus allowed us to identify more frequency components of impedance (6 vs. 5) over the desired frequency band to estimate more robust model parameter estimates (see below) but at the expense of temporal resolution.

The Pao(t) and (t) signals from each 8-s recording period were filtered into their spontaneous breathing and oscillatory components as for the passive expiration measurements above, and then the oscillatory components were analyzed by first dividing them into 1-s windows that overlapped by 50%. The mean cross and auto power spectral densities were calculated as

| (4) |

and

| (5) |

where the functions of f in Eqs. 4 and 5 are the fast Fourier transforms of the corresponding time-domain signals within each of the n overlapping windows and asterisk (*) denotes the complex conjugate. Impedance for the entire 8-s measurement period was then calculated as

| (6) |

where f = 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, and 19 Hz.

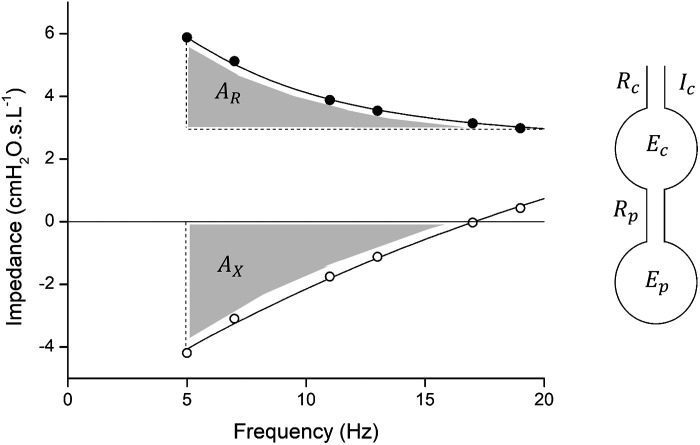

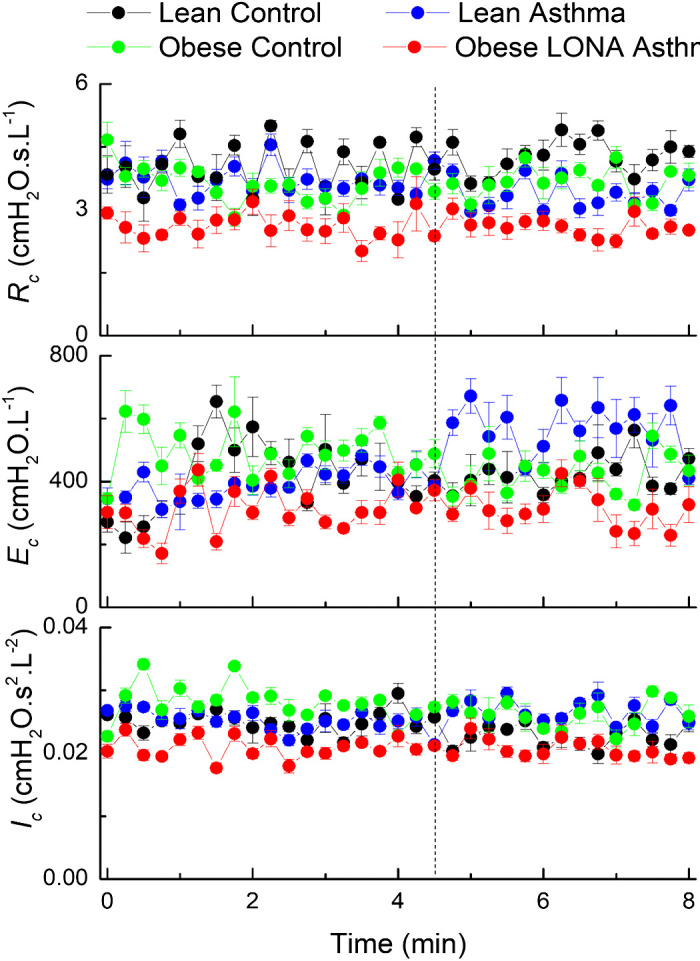

Zrs(f) calculated in this way was then fit with a two-compartment series model of the respiratory system (Fig. 1) having five free parameters: central compartment resistance, elastance, and inertance (Rc, Ec, and Ic, respectively) and peripheral compartment resistance and elastance (Rp and Ep, respectively). The impedance of this two-compartment model (Zmod−1) is given by the following system of coupled equations:

| (7) |

| (8) |

and was fit to Zrs(f) by repeatedly searching over a sequentially refined five-dimensional grid of values corresponding to the model parameters Rc, Ec, Ic, Rp, and Ep. This yielded time-courses of the model parameter over the course of the 8-min measurement period. The three parameters of the central compartment, Rc(t), Ec(t), and Ic(t), account for central structures at least some of which are likely proximal to the trachea, while the two parameters of the peripheral compartment, Rp(t) and Ep(t), account for the mechanical properties of distal lung structures (12).

Fig 1.

An example of real and imaginary parts of impedance [R(f) (closed circles) and X(f) (open circles)] together with the fits provided by the 2-compartment model. The areas AX and AR are shown as the shaded regions. The diagram at right shows the 2-compartment series model of the respiratory system characterized by the 5 parameters central airway resistance (Rc), central airway elastance (Ec), central airway gas inertance (Ic), peripheral airway resistance (Rp), and peripheral airway elastance (Ep).

We calculated means ± SE for all model parameters at each time point for the four groups of participants. Before this, any impedance measurements that had coherence values <0.85 were discarded as being of insufficient quality. Following the initial calculations of means ± SE of the remaining data that had acceptable coherences, we repeated the calculation after discarding those few data points that fell outside ± 2 SD in the original analysis. This was necessary because some of the participants had fits of coughing occasionally during the methacholine challenge that rendered the impedance measurements made during the fits uninterpretable.

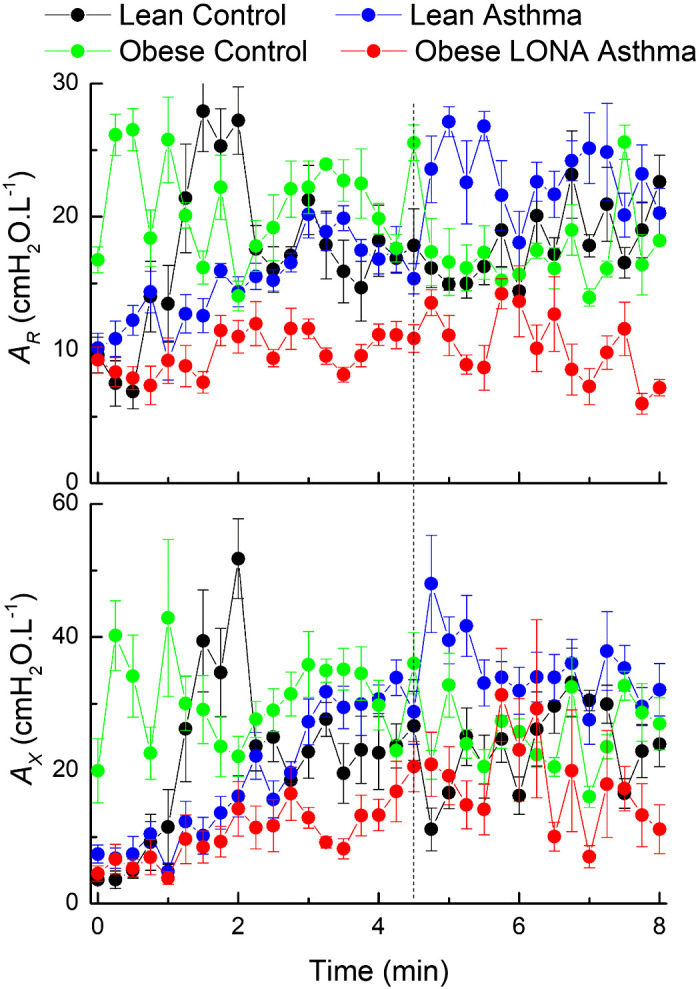

We also calculated two empirical parameters from the measured impedance spectra. The first parameter, designated AX, is derived from the imaginary part of impedance as the magnitude of the area between X(f) and the frequency axis between 5 Hz and the resonant frequency (13). AXhas become quite widely used in clinical studies because it is particularly sensitive to changes in respiratory system stiffness, and it is also robust to noise because it is an integrative measure of the data. As a somewhat corresponding parameter for the real part of impedance, we calculated the area between R(f) and R(20) over the frequency range 5 ≤ f ≤ 20 Hz, designated AR as illustrated in Fig. 1. AR carries essentially the same information as the commonly used difference R(5) − R(20) but again is more robust (less sensitive to noise) because it is an integrative measure of the data rather than being derived from only two data points. AX and AR have the same units of cmH2O·L−1 and were evaluated from the fits to the impedance data provided by the two-compartment model (Fig. 1). This model fit the data well and so provided a means for describing the deterministic components of the impedance measurements and for predicting resonant frequency in those cases where it occurred above the highest frequency used to measure impedance (19 Hz). The areas were calculated by numerical integration.

We estimated the tidal volume of spontaneous breathing within each 8-s measurement period as the peak-to-peak swing in Vspon(t) determined as in Eq. 3. We estimated the frequency of spontaneous breathing from the mean time interval between zero-crossings of Vspon(t) after its mean value had been subtracted.

Statistics

Pilot measurements of changes in Rrs from the single-compartment model from TLC to FRC indicated they start at ∼1 cmH2O·s·L−1 and approximately double with methacholine challenge, with SD = 0.2 cmH2O·s·L−1, a physiologically significant response. We also anticipated that the frequency dependence of Rrs from the two-compartment model in response to methacholine would be higher in LONA asthmatics compared with either obese controls or lean asthmatics, being ∼5.2 mH2O·s·L−1 in LONA asthmatics, and 3.1 mH2O·s·L−1 in obese controls and lean asthmatics (SD 1.7 mH2O·s·L−1), based on pilot data collected at our center. A one-way ANOVA suggested that a sample size of n = 10 participants per group would yield a 5% type I error level with a power of 80%, and thus enable us to see a statistically significant difference between groups if there was one. Unfortunately, because of some technical issues mostly related to difficulties some participants had in completing the study maneuvers (explained above), we did not always achieve this group size in every group, which reduced the power of our study accordingly.

Differences in the relationships between impedance parameters and lung volume obtained during the relaxed expiration maneuvers were determined by linear regression which provided confidence intervals about the slopes of the relationships. Differences across groups for the methacholine challenge tests were tested by ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis test. Group pairs were compared by t test with Bonferroni correction. Regression analysis was performed using Origin 8.6.0 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Statistical significance was interpreted as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Passive Exhalation

One participant in the Obese LONA Asthma group was physically unable to complete the passive relaxation test. The data from one participant in the Obese Control group had to be discarded because of equipment malfunction. Those who successfully completed the test returned a mean (±SD) exhaled volume of 2.52 (±0.85) liter. Some participants, however, returned aberrantly low exhaled volumes either because they were unable to perform the maneuver properly or because they did not seal their lips around the mouthpiece despite our training procedure. We therefore discarded the data from two participants in the Obese Control group and one participant from the Obese LONA Asthma group because they exhaled less than the arbitrarily designated threshold of 1.5 liter. One participant in the Obese LONA Asthma group returned impedance data (see below) that were much greater than those of the other participants (far outside 2 SD away from the group mean). We suspect that this participant was not able to relax their glottis properly during expiration, so the data from this participant were discarded. The final group numbers for the relaxed expiration test were thus n = 8 for Lean Control, n = 10 for Lean Asthma, n = 7 for Obese Control, and n = 8 for Obese LONA Asthma.

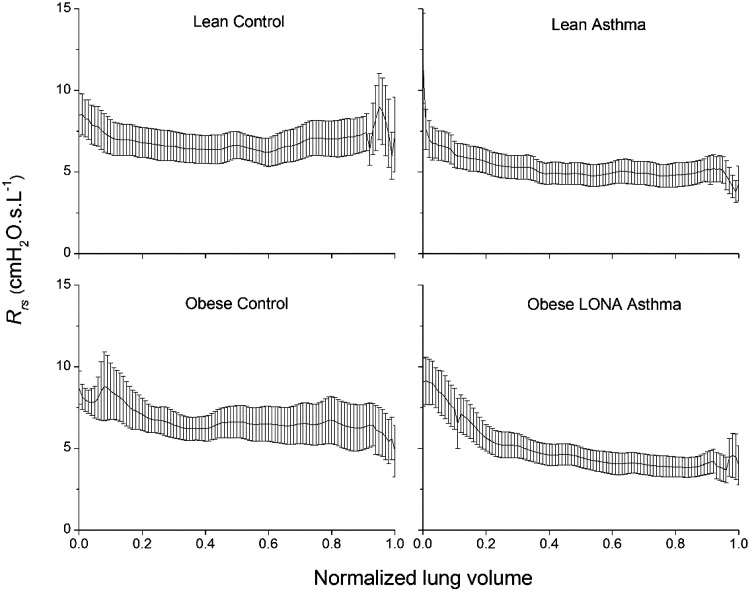

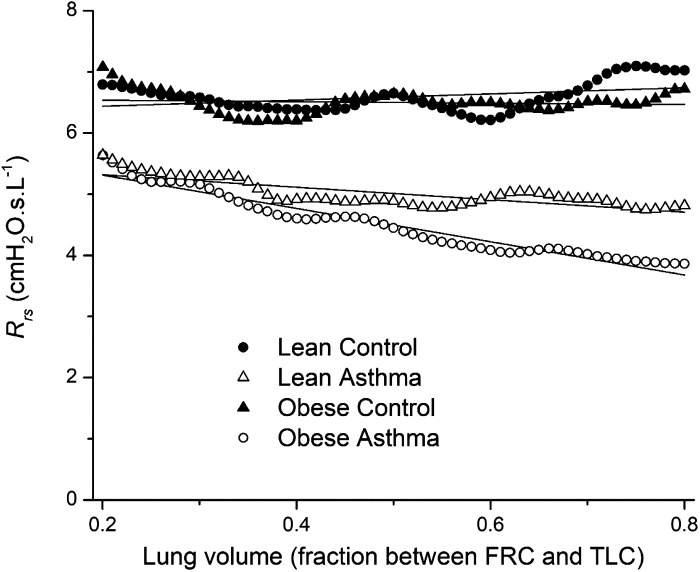

Figure 2 shows Rrsversus lung volume during slow expiration from TLC to FRC. The portions of the tracings close to TLC contain artifacts reflecting the opening of the expiratory valve and the fact that participants typically required a second or two to become comfortable once expiration was underway, so we discount the behavior of Rrs over the first 20% of the volume range. Rrs exhibited a marked upward trend in all groups over the lower 20% of the volume range (Fig. 2). Figure 3 shows mean Rrs for each of the four study groups between 20% and 80% of the volume range together with their respective lines of best fit. The slopes of these lines and their 95% confidence intervals are given in Table 2. None of these confidence intervals overlap, implying that the slopes are all significantly different from each other, and the only interval that included zero was that for the Lean Control group. Nevertheless, it is quite clear from inspection of Fig. 3 that neither control group exhibited a physiologically important dependence of Rrs on volume. In contrast, the two asthmatic groups both exhibited a marked negative dependence of Rrs on volume, suggesting that airway caliber and/or the fraction of open lung were noticeably reduced by decreases in lung volume. This negative volume dependence was significantly enhanced in the Obese LONA Asthma group. Curiously, Rrs was lower overall in the asthmatic groups compared with the control groups (Fig. 3 and Table 2).

Fig 2.

Respiratory system resistance (Rrs) during slow relaxed expiration from total lung capacity (1.0) to functional residual capacity (0.0). The data are presented as means ± SE.

Fig. 3.

Respiratory system resistance (Rrs) versus fraction of lung volume between functional residual capacity (FRC) (0) and total lung capacity (TLC) (1.0). The symbols are mean values for each of the study groups between 20% and 80% of the volume range. Symbols represent the experimental measurements; solid lines are linear fits to each group. Linear regression analysis was used to determine that all slopes are significantly different (P < 0.05, Table 2).

Table 2.

Slopes of Rrs versus lung volume from 80% to 20% of the volume range between FRC and TLC

| Slope of Group Mean, cmH2O·s·L-1 | SE of Slope, cmH2O·s·L-1 | 95% Confidence Limits, cmH2O·s·L-1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lean Control | 0.504 | 0.164 | [0.176, 0.832] |

| Lean Asthma | −1.019 | 0.103 | [−1.225, −0.813] |

| Obese Control | −0.122 | 0.135 | [−0.392, 0.148] |

| LONA Asthma | −2.724 | 0.084 | [−2.892, −2.556] |

The 95% confidence limits on the slopes are calculated as the mean slope ± 2 × SE, by which measure all the slopes are significantly different from each other. Rrs, respiratory system resistance.

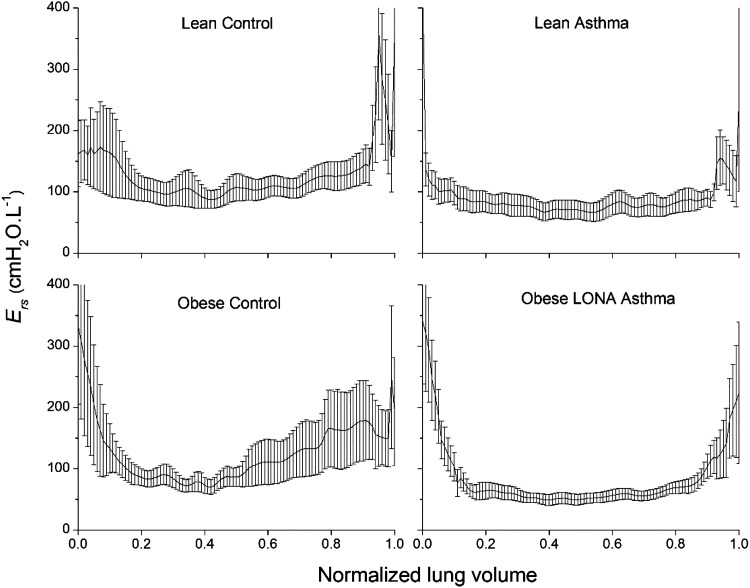

Figure 4 shows that Ers also exhibited an upward trend in all participant groups over the lower 20% of the volume range. This trend was dramatically increased in obesity, however, amounting to an increase of roughly fourfold from the minimum midrange value in both obese participant groups. The Lean Asthma group exhibited a sudden dramatic increase in Ers at the very lowest point in volume (Fig. 4); we cannot tell if this is anomalous or the sudden appearance of closing volume in these participants. We therefore determined the slopes of linear fits to Ers versus normalized volume over the lower 20% of the volume range, with the exception of the last point (volume of zero). These slopes are −535 (SE 45), −230 (SE 26), −1,132 (SE 103). and −1,328 (SE 149) cmH2O·L−1 for the Lean Control, Lean Asthma, Obese Control, and Obese LONA Asthma groups, respectively. The slopes for the two obese groups are thus substantially greater in magnitude and far beyond the ranges encompassed by the SE ranges, compared with the two lean groups.

Fig 4.

Respiratory system elastance (Ers) during slow relaxed expiration from total lung capacity (1.0) to functional residual capacity (0.0). The data are presented as means ± SE. We therefore determined the slopes of linear fits to Ers versus normalized volume over the lower 20% of the volume range, with the exception of the last point (volume of 0). These slopes of mean over the lower 20% of the volume range were determined by linear regression. The slopes for the 2 obese groups are significantly greater in magnitude compared with those of the 2 lean groups as assessed by the fact that their respective ± SE ranges do not overlap. LONA, late-onset nonallergic.

Methacholine Challenge

The methacholine challenge test was attempted by all the participants in the study. One participant in the Obese LONA Asthma group was unable to complete this test. The data from two participants in the Obese LONA Asthma group and one participant from the Obese Control group had to be discarded either because of equipment malfunction or failure to follow the correct protocol. The final group numbers for the methacholine challenge test were thus n = 10 for Lean Control, n = 10 for Lean Asthma, n = 9 for Obese Control, and n = 8 for Obese LONA Asthma. Figures 5–8 show means ± SE after elimination of outlier participants that fell more than 2 SE from the group mean at each time point.

Fig 5.

Time courses for the inertance, elastance, and resistance (Ic, Ec, and Rc, respectively) of the central compartment of the series 2-compartment model of respiratory system mechanics during aerosol methacholine challenge (0 to 4.5 min) and subsequently (4.5 to 8 min). The vertical dashed line indicates the time at which methacholine aerosolization was terminated. The data are presented as means ± SE. LONA, late-onset nonallergic.

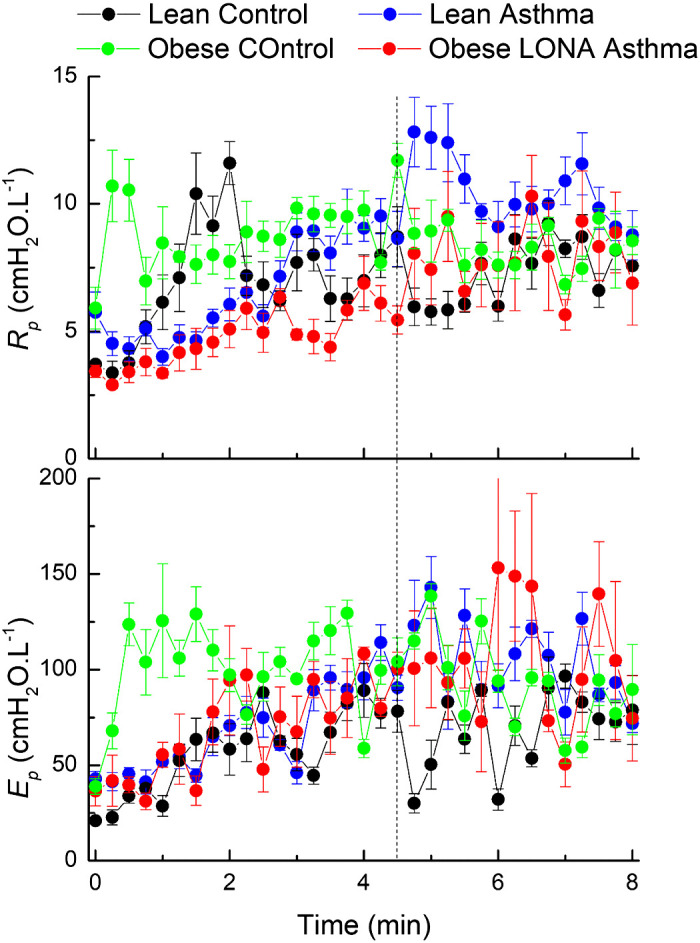

The mean residual between the impedance data and the two-compartment model fit had an average value across the 8-min measurement period of between 0.16 (SD 0.03) and 0.24 (SD 0.04) cmH2O·L−1 for the four study groups and remained essentially unchanged over time. These residuals are roughly an order of magnitude smaller than the magnitude of impedance itself over the range of frequencies we examined, indicating that the model fit the impedance well. None of the parameters defining the central compartment (Rc, Ec, and Ic) exhibited marked systematic variations over time, except possibly the Lean Asthma group in which Ec appears somewhat elevated following the challenge (Fig. 5). The different groups also had similar values between groups except Rc, which was slightly lower in the Obese LONA group compared with the other groups (Fig. 5, top). The parameters of the peripheral compartment (Rp and Ep) did, however, exhibit changes over time in some groups (Fig. 6). We compared slope differences between the four groups both during challenge (the first 4.5 min when methacholine aerosol was being delivered) and postchallenge (the final 3.5 min after aerosolization had been terminated). The slopes of Rp versus time (Fig. 6, top) were positive and significantly different between the groups during challenge (P = 0.025), with pairwise comparison showing the slope for lean asthmatics being greater than for obese controls (P = 0.01). Postchallenge, the slopes were also different among the groups (P = 0.045) and were positive for the lean controls and obese LONA participants but negative for the lean asthmatics and obese controls. The slopes of (Ep) versus time (Fig. 6, bottom) during challenge were also significantly different between the groups (P = 0.045), but the slopes were not different postchallenge.

Fig 6.

Time courses for the resistance and elastance (Rp and Ep, respectively) of the peripheral compartment of the series 2-compartment model of respiratory system mechanics during aerosol methacholine challenge (0 to 4.5 min) and subsequently (4.5 to 8 min). The vertical dashed line indicates the time at which methacholine aerosolization was terminated. The data are presented as means ± SE. The slopes of Rp versus time are significantly different between the groups during challenge (ANOVA, P = 0.025). The slopes for lean asthmatics are greater than for obese controls (pairwise comparison with Bonferroni correction, P = 0.01). Postchallenge, the slopes are different among the groups (P = 0.045). The slopes of Ep versus time during challenge are significantly different between the groups (P = 0.045) but are not different postchallenge. LONA, late-onset nonallergic.

The slopes of the novel parameter AR versus time were not different among the groups either during or postchallenge, but the values of AR themselves were clearly lower for the Obese LONA group than for the other groups (Fig. 7, top), possibly reflecting the fact that Rrs was lowest in this group (Fig. 3). The slopes of AX versus time during challenge were significantly different between groups (P = 0.003), with the Lean Asthma slope greater than both Obese Control (P = 0.001) and LONA (P = 0.045). The slopes of AX versus time were not different postchallenge.

Fig 7.

Time courses for the areas AR and AX calculated from the fits provided by the 2-compartment model, as illustrated in Fig. 1 during aerosol methacholine challenge (0 to 4.5 min) and subsequently (4.5 to 8 min). The vertical dashed line indicates the time at which methacholine aerosolization was terminated. The data are presented as means ± SE. The slopes of AX versus time during challenge are significantly different between groups (ANOVA, P = 0.003), with the Lean Asthma slope greater than both Obese Control (P = 0.001) and late-onset nonallergic (LONA) (P = 0.045). The slopes of AX versus time were not different postchallenge.

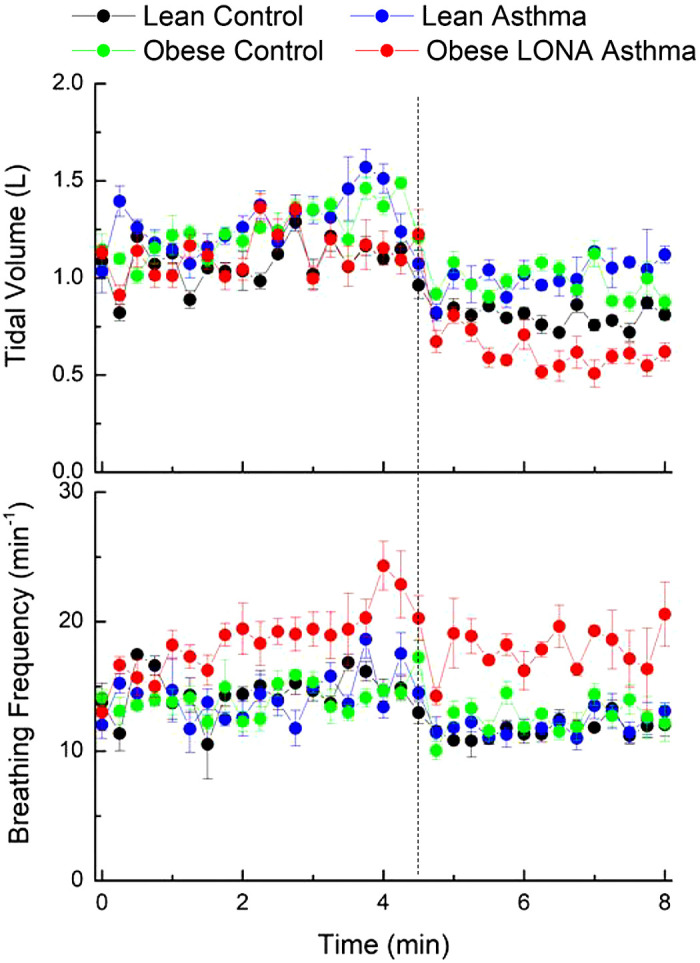

Figure 8 shows tidal volume versus time during the methacholine challenge test. Following cessation of aerosolization at 4.5 min the tidal volume fell immediately in all four groups (Fig. 8, top). This was presumably due in some way to the elimination of the bottom 100 mL·S−1 flow that was injected into the respiratory circuit by the nebulizer (note that this was a constant flow and thus would not have interfered with the measuring of impedance at frequencies of 5 Hz and above). Breathing frequency was significantly higher in the Obese LONA Asthma group compared with the other three groups, which themselves were not different to each other (Fig. 8, bottom). Also, with the exception of the Obese LONA Asthma group, there is a suggestion that breathing frequency decreased immediately upon cessation of aerosolization.

Fig 8.

Tidal volume and breathing frequency versus time during aerosol methacholine challenge (0 to 4.5 min) and subsequently (4.5 to 8 min). The vertical dashed line indicates the time at which methacholine aerosolization was terminated. The data are presented as means ± SE. Breathing frequency was significantly higher in the Obese Asthma late-onset nonallergic (LONA) group compared with the other 3 groups (ANOVA, P < 0.05), which themselves were not different to each other.

DISCUSSION

We recently showed (7) that chronic lung compression is a feature of both obese nonasthmatic and obese LONA asthmatic participants, as reflected in comparable reductions in plethysmographic FRC. However, spirometry and multiple breath nitrogen washout also suggested that obese LONA asthmatics have a reduced ability to recruit closed lung units compared with obese nonasthmatics. Further elucidating the phenotype of LONA obese asthma, however, requires a more precise and specific link between lung structure and function than is provided by the conventional methods of clinical lung function assessment. Oscillometry is a method for measuring impedance, a quantity that naturally lends itself to being interpreted in terms of simple models having components that represent important and readily identifiable physiological attributes of the respiratory system. Accordingly, in the present study we used oscillometry to determine how respiratory system impedance is affected by changes in lung volume and by methacholine challenge in the same groups of participants as in our previous study (7).

The most dramatic results of the present study relate to the way in which Ers changed with lung volume during exhalation in the obese versus lean participants. Although the early portions of the relationships starting from a normalized lung volume of 1.0 (corresponding to TLC) are somewhat unreliable because of the challenges a number of the participants had in relaxing into expiration, both obese groups exhibited a substantial degree of airway closure toward the end of exhalation as evidenced by sudden and profound upturns in Ers once volume descended to within ∼20% of FRC (Fig. 4). This marked stiffening of the respiratory system at low volume could potentially reflect a decreasing lung and/or chest wall compliance; it could also reflect progressive lung derecruitment as volume decreases. Indeed, the phenomenon of closing volume being greater than FRC in asthmatic participants has been reported previously (14), and our previous study (7) led us to expect the same might happen in both obese groups due to depression of FRC by the weight of adipose tissue around the trunk. That is, due to the excess weight of the chest wall, FRC is reduced in obese subjects to the extent that it can descend below closing volume. What we were not prepared for, however, was the magnitude of the effect. The two obese groups experienced increases in Ers from its lowest point at midexpiration to its value at end expiration by a factor of roughly 5, whereas the two lean groups experienced corresponding increases of only roughly 1.75-fold (Fig. 4). Assuming Ers to be inversely proportional to the fraction of open lung, these findings suggest that our obese participants had ∼15% of their lungs open at FRC while the lungs of the lean participants remained well over 50% open at FRC. This presumably has strong implications for daily living, particularly since the measurements were made in the sitting position; one would anticipate FRC to be further reduced in the supine position, raising serious concerns about the way in which sleep might be affected in obese participants.

There were also differences between the groups in the way that Rrs changed with lung volume during slow relaxed exhalation (Fig. 2), although these differences were not as dramatic as those in Ers. Over the central portion of the volume range between TLC and FRC, the two groups of asthmatic participants had greater negative dependencies of Rrs on lung volume compared with the two control participant groups (Fig. 3). This negative dependency was strongest in the participants with obese LONA asthma (Table 2), implying that their airways had an impaired ability to remain patent as parenchymal tethering forces decrease during expiration. This supports the hypothesis we previously advanced (5) that participants with obese LONA asthma have more collapsible airways than their nonasthmatic obese counterparts. Somewhat counterintuitively, Rrs itself was lower throughout expiration in the asthmatic compared with the control participants (Figs. 2 and 3). It is possible that this is simply coincidental, reflecting random differences in the mean lung function characteristics of the small number of participants in each group.

The effects of methacholine challenge on respiratory system impedance (Figs. 5–7) were not nearly as different between groups as the effects of lung volume change, particularly compared with those shown in Fig. 4. This is not entirely surprising because we challenged each participant with their PC20 dose of methacholine, which had two consequences: 1) the PC20 dose targets a similar level of response in each participant, so similar changes in impedance parameters are to be expected; and 2) the response elicited by the PC20 dose is by definition quite modest for safety reasons, creating difficulties discerning intergroup differences above the noise. The PC20 doses themselves were very different between the control and asthmatic participants (Table 1), in keeping with the differences in airways responsiveness they imply. That aside, methacholine challenge had no discernible effects on the parameters Rc, Ec, and Ic of the more proximal of the two compartments in the model shown in Fig. 1. To the extent that this compartment reflects the mechanical properties of structures proximal to the resistive airways of the lung (12), such a lack of sensitivity to bronchoconstriction is to be expected. The one exception is a possible slight elevation in Ec toward the end of the maneuver in the Lean Asthma group, possibly reflecting strain stiffening of proximal compliant structures due to increased shunting of the flow oscillations caused by central airway constriction, a phenomenon expected in conventional asthma.

The peripheral compartment parameters Rp and Ep, on the other hand, did show increasing trends in response to methacholine challenge with the possible exception of the Obese Control group (Fig. 6). Some statistical differences were found between the slopes of these parameters versus time either during or postchallenge, and one might draw the impression from inspection of the plots in Fig. 6 that the parameters of the Obese Control group started somewhat higher than the other groups, possibly because this group was the heaviest and suffered the greatest degree of lung compression by the chest wall. Also, there is a suggestion of differences in the ways in which Rp and Ep change over time; both parameters increase early on in the two control groups and in the obese LONA asthma participants, while the obese control participants remained relatively steady throughout the 8-min measurement period. These observations must be made tentatively, though, given the level of noise in the data. This noise likely came from a number of sources, not the least of which was the difficulty that some of the participants had in tolerating the methacholine challenge. We excluded impedance measurements that were obviously affected by coughing on the basis of low coherence and obvious outlier data points, but breathing pattern variations that were undetectable on these bases still influence the ensemble results shown in Fig. 6. In addition, the participants were free to vary not only their breathing patterns throughout the 8-min challenge protocol but also their mean lung volumes. It is quite possible, or indeed even likely, that they may have elevated their lung volumes to counteract the bronchoconstriction they experienced due to the methacholine; increasing lung volume is well known to be an extremely potent means of reversing airway narrowing (5, 15).

The parameters shown in Figs. 5 and 6 characterize a model representation of the lung (Fig. 1) that typically gives good fits to respiratory system impedance data over the frequency range 5–20 Hz. Nevertheless, this model is still only a very crude representation of reality, its two compartments being difficult to interpret as corresponding to any readily identifiable anatomical counterparts. To avoid the ambiguities inherent in such a simple representation, it has become popular in recent years to summarize impedance spectra over this frequency range in terms of empirical quantities that do not invoke any particular model structure (13). The four quantities most commonly used are the value of resistance at 5 Hz, R(5), the value of resistance at 20 Hz, R(20), the value of reactance at 5 Hz, X(5), and the magnitude of the area between the reactance curve and the frequency axis from 5 Hz up to the resonant frequency, AX. Of these, AX has shown particular utility (16), likely due to the fact that bronchoconstriction is frequently accompanied by closure of lung units that imparts a substantial change in reactance. Also, AX is robust to noise in the data because multiple reactance data are used in its determination (Fig. 1) rather than only a single measurement as is the case with R(5), R(20), and X(5). Accordingly, we used AXas a model-independent quantity to characterize reactance. In addition, we devised a correspondingly robust quantity to summarize the frequency dependence of resistance in the quantity AR(Fig. 1). The responses in AR and AX to methacholine challenge in the four study groups (Fig. 7) present a somewhat similar picture to that given by the two peripheral compartment parameters of the two-compartment model (Fig. 6), although with perhaps slightly more intergroup discrimination. For example, exhibits essentially no change over time during challenge, and remains somewhat lower for the Obese LONA Asthma and Obese Control groups compared with the others. AXin contrast, clearly increases with challenge in all groups except the Obese Control group in which it begins relatively elevated and remains essentially constant. Overall, AR and AX increased rather substantially with methacholine challenge in the two lean groups but remained relatively unchanged in the obese groups. We might speculate that this could reflect less aerosol deposition throughout the lungs of the obese individuals due to increased derecruitment of the lung periphery.

We were, however, able to examine two key parameters of the pattern of breathing, tidal volume and breathing frequency (Fig. 8), and we found some surprising results. First, all participants exhibited a sudden drop in tidal volume when methacholine aerosolization was terminated at 4.5 min (Fig. 8, top) and, with the possible exception of the Obese LONA group, a corresponding but less marked drop in breathing frequency (Fig. 8, bottom). These findings suggest that the aerosolization was facilitating ventilation by somehow unloading the work of breathing. One possibility is that this was due to the 100 mL·S−1 airflow that generated the aerosol, as this would have helped stent open the lungs and support breathing, although the effective CPAP generated by this flow acting against the outflow resistance of the circuit would have amounted to only ∼1 cmH2O. On the other hand, the magnitude of the drops in tidal volume in Fig. 8 at 4.5 min are in the region of a few hundred milliliters, which could reflect the elimination of 100 mL/s to inspiratory flow for an inspiratory duration of a few seconds. Regardless of the cause, however, the Obese LONA Asthma group had the largest drop in tidal volume as well as consistently greater breathing frequencies than the other groups (Fig. 8, bottom) and showed the least degree of reduction postchallenge. Taken together, the results in Fig. 8 indicate a pattern of rapid shallow breathing in the Obese LONA group suggestive of respiratory distress compared with the other groups.

A potential explanation for these findings is that the participants with obese LONA asthma experienced greater loss of ventilatable lung volume with the removal of pressure assist that they are less able to recruit during inspiration, requiring them to increase their breathing frequency to maintain minute ventilation. This interpretation is speculative, but it fits with our previous study in these participants (7) that showed evidence of increased lung derecruitment in the participants with obese LONA asthma. Also, dynamic hyperinflation in obese asthmatics has been reported in response to methacholine (17) and exercise (18), possibly as a result of expiratory flow limitation and its concomitant intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure (19, 20), and it is known that blood flow becomes redistributed by local bronchoconstriction as a result of hypoxic vasoconstriction and other mechanisms (21), so it is possible that these mechanisms might be abnormal in obese asthmatic individuals. Alternatively, the changes in breathing pattern at 4.5 min may have reflected some degree of stimulation to breathing due to the sensation of an aerosol entering the lungs. The rapidity of the effect, however, makes it seem unlikely to have been due to the nebulizer flow washing out dead space gas.

The results of the present study thus show dramatic physiological effects of obesity on the lung, as well as effects specific to obese LONA asthma, but these findings must be viewed in light of the study limitations. For example, the four groups we studied were small, containing only 10–11 participants each, which limited our ability to discern biological signals above the noise. Also, the participants in the Lean Asthma group were ∼15 yr younger than those in the other groups due to difficulties in identifying older lean individuals with asthma in our community. It is difficult to know how this might have impacted our conclusions about the relative differences between groups. It is perhaps possible that the younger lungs in the lean asthmatics might have less age-related lung function decline that could have made them less prone to peripheral lung collapse than the older participants in the other groups, but with a mean age in the mid-40s such a difference would likely have been very mild (22). The use of methacholine challenge as a perturbation to probe respiratory physiology was especially affected by noise because of the ethical requirement that we use modest levels of challenge that elicited correspondingly modest responses. Decreasing lung volume from TLC to FRC during relaxed expiration was a substantially more robust perturbation to the respiratory system, and gave more dramatic differences in impedance between the study groups as a consequence. Nevertheless, we cannot be sure that the participants relaxed properly during the expirations and did not, for example, continue to push through below FRC using their expiratory muscles. We believe that this effect, however, would have been common to all four study groups and that by averaging results from multiple participants per groups we are able to converge toward a valid picture of impedance changes of the TLC-FRC volume range. Another limitation is that while respiratory system impedance in principle allows a link to be made between lung structure and function on the basis of mathematical models, the models themselves are necessarily simple and so have limited capacity to resolve structures of interest. Despite these limitations, however, we were still able to identify intergroup differences, some of them quite dramatic.

In summary, respiratory system impedance measured from TLC to FRC suggests that the lungs of very obese individuals experience profound degrees of collapse during expiration as a result of the weight of the obese chest wall depressing FRC to levels below the closing volume of the lung. This collapse does not, however, appear to distinguish individuals with obese LONA asthma from obese individuals who do not have asthma. On the other hand, the conducting airways of individuals with obese LONA asthma are more dependent on lung volume than are the airways of nonasthmatic obese individuals, indicating either that the airways are more compliant or airway-parenchyma interdependence is reduced. Examination of respiratory impedance during and postmethacholine challenge also suggests that obese individuals with LONA asthma experience greater respiratory distress that their nonasthmatic and lean counterparts. Although the biologic mechanisms underlying this unique physiological signature of obese LONA asthma remain to be fully elucidated, they may involve an increased propensity of the lungs to derecruit and to be more recalcitrant to re-recruitment with a deep breath.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01-HL-130847 (to J.H.T.B. and A.E.D., co-principal investigators).

DISCLOSURES

J.H.T.B is a consultant for and shareholder in Oscillavent, LLC (Iowa City, IA), a consultant for Healthy Design, LLC (Chittenden, VT), and a consultant for Johnson & Johnson. He also is coinventor on the following patents: “Noninvasive Pulmonary Airway Resistance Measurement System,” US7945303 B2, issued May 17, 2011 (C168); “Device and Method for Lung Measurement” U.S; patent application US 20160007882 A1, filed on January 29. 2013, patent pending (C501); and “Variable Ventilation as a Diagnostic Tool for Assessing Lung Mechanical Function,” PCT Application WO2015127377 A1, filed on February 23, 2014 (C538). None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.H.B., D.A.K., and A.E.D. conceived and designed research; U.P., N.D., E.S.M. and K.H. performed experiments; J.H.B., S.B., and A.E.D. analyzed data; J.H.B., U.P., D.A.K., S.B., and A.E.D. interpreted results of experiments; J.H.B. prepared figures; J.H.B. drafted manuscript; J.H.B., U.P., N.D., E.S.M., K.H., D.A.K., S.B., and A.E.D. edited and revised manuscript; J.H.B., U.P., N.D., E.S.M., K.H., D.A.K., S.B., and A.E.D. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seidell JC, Halberstadt J. The global burden of obesity and the challenges of prevention. Ann Nutr Metab 66: 7–12, 2015. doi: 10.1159/000375143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holguin F, Bleecker ER, Busse WW, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Erzurum SC, Fitzpatrick AM, Gaston B, Israel E, Jarjour NN, Moore WC, Peters SP, Yonas M, Teague WG, Wenzel SE. Obesity and asthma: an association modified by age of asthma onset. J Allergy Clin Immunol 127: 1486–1493, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sideleva O, Suratt BT, Black KE, Tharp WG, Pratley RE, Forgione P, Dienz O, Irvin CG, Dixon AE. Obesity and asthma: an inflammatory disease of adipose tissue not the airway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186: 598–605, 2012. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0573OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding DJ, Martin JG, Macklem PT. Effects of lung volume on maximal methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction in normal humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 62: 1324–1330, 1987. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.62.3.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bates JH, Dixon AE. Potential role of the airway wall in the asthma of obesity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 118: 36–41, 2015. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00684.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bates JH, Irvin CG, Farre R, Hantos Z. Oscillation mechanics of the respiratory system. Compr Physiol 1: 1233–1272, 2011. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/cphy.c100058]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dixon AE, Peters U, Walsh R, Daphtary N, MacLean ES, Hodgdon K, Kaminsky DA, Bates JH. Physiological signature of late-onset non-allergic asthma of obesity. Eur Respir J Open Res 26: 319–338, 2020. [https://openres.ersjournals.com/content/6/3/00049-2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crapo RO, Casaburi R, Coates AL, Enright PL, Hankinson JL, Irvin CG, MacIntyre NR, McKay RT, Wanger JS, Anderson SD, Cockcroft DW, Fish JE, Sterk PJ. Guidelines for methacholine and exercise challenge testing-1999. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161: 309–329, 2000. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.ats11-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wanger J, Clausen JL, Coates A, Pedersen OF, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, Hankinson J, Jensen R, Johnson D, Macintyre N, McKay R, Miller MR, Navajas D, Pellegrino R, Viegi G. Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes. Eur Respir J 26: 511–522, 2005. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunyer J, Anto JM, Castellsague J, Soriano JB, Roca J. Total serum IgE is associated with asthma independently of specific IgE levels. The Spanish Group of the European Study of Asthma. Eur Respir J 9: 1880–1884, 1996. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09091880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nilsen K, Thien F, Thamrin C, Ellis MJ, Prisk GK, King GG, Thompson BR. Early onset of airway derecruitment assessed using the forced oscillation technique in subjects with asthma. J Appl Physiol (1985) 126: 1399–1408, 2019. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00534.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bates JH. The role of airway shunt elastance on the compartmentalization of respiratory system impedance. J Eng Sci Med Diagnost Ther 2: 011001–110018, 2019. doi: 10.1115/1.4042308. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32328571/]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman MD. Clinical application of forced oscillation. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 14: 341–350, 2001. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2001.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly VJ, Sands SA, Harris RS, Venegas JG, Brown NJ, Stuart-Andrews CR, King GG, Thompson BR. Respiratory system reactance is an independent determinant of asthma control. J Appl Physiol (1985) 115: 1360–1369, 2013. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00093.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bates JH, Lauzon AM, Dechman GS, Maksym GN, Schuessler TF. Temporal dynamics of pulmonary response to intravenous histamine in dogs: effects of dose and lung volume. J Appl Physiol (1985) 76: 616–626, 1994. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.2.616. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8175571/]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldman MD, Carter R, Klein R, Fritz G, Carter B, Pachucki P. Within- and between-day variability of respiratory impedance, using impulse oscillometry in adolescent asthmatics. Pediatr Pulmonol 34: 312–319, 2002. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutherland TJ, Cowan JO, Taylor DR. Dynamic hyperinflation with bronchoconstriction: differences between obese and nonobese women with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 177: 970–975, 2008. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1738OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferreira PG, Freitas PD, Silva AG, Porras DC, Stelmach R, Cukier A, Fernandes FL, Martins MA, Carvalho CR. Dynamic hyperinflation and exercise limitations in obese asthmatic women. J Appl Physiol (1985) 123: 585–593, 2017. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00655.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King GG, Brown NJ, Diba C, Thorpe CW, Munoz P, Marks GB, Toelle B, Ng K, Berend N, Salome CM. The effects of body weight on airway calibre. Eur Respir J 25: 896–901, 2005. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00104504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pankow W, Podszus T, Gutheil T, Penzel T, Peter J, Von Wichert P. Expiratory flow limitation and intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure in obesity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 85: 1236–1243, 1998. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.4.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly VJ, Hibbert KA, Kohli P, Kone M, Greenblatt EE, Venegas JG, Winkler T, Harris RS. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction does not explain all regional perfusion redistribution in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 196: 834–844, 2017. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201612-2438OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner JM, Mead J, Wohl ME. Elasticity of human lungs in relation to age. J Appl Physiol 25: 664–671, 1968. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1968.25.6.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]