Abstract

In patients with HIV infection, lower limb weakness is a result of the pathological involvement of the brain, spinal cord or peripheral nervous system. The pathological process can be opportunistic infections, nutrient deficiencies, neoplastic infiltration or HIV itself. Here, we present the case of a 50-year-old manual labourer who presented with gradually progressive lower limb weakness, sensory disturbances, impotence and urinary urgency. He was diagnosed with HIV during evaluation. Based on the presentation and other supportive laboratory and radiological evidence, the following differentials were considered: vacuolar myelopathy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and myeloradiculopathy. The patient was initiated on antiretroviral therapy, and he showed significant improvement of symptoms on follow-up. We report this case to discuss the diagnostic puzzle.

Keywords: HIV / AIDS, tropical medicine (infectious disease), motor neurone disease, infection (neurology), spinal cord

Background

HIV infection can cause chronic neurological disease in all neuraxis levels, including the brain, meninges, spinal cord, nerve and muscle. Neurological disease is the first manifestation of symptomatic HIV in approximately 10%–20% of persons. Also, about 60% of patients with advanced HIV disease have clinically evident neurological dysfunction during their illness.1–3 Neurological complications of HIV are not confined to those developing directly from the infection with HIV itself; it may even occur due to opportunistic infections or treatment complications.

We discuss a case of a middle-aged man with HIV infection who presented with progressive flaccid paraparesis, sexual dysfunction and urge incontinence to highlight the diagnostic dilemmas faced during the management of such a case.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old married heterosexual man with no significant comorbidities, presented with a 4-month history of progressive, asymmetric (right>left) lower limb weakness (distal>proximal). He was asymptomatic 4 months ago when he noticed an inability to grip his footwear with the frequent slipping of slippers. This occurred more frequently on the right foot when compared with the left. He reported dull low backache that was localised and without any diurnal variation during the same time. There was no aggravation of the backache with activity or rest. Over 2 weeks, he also noticed that he was having difficulty getting up from the squatting position. He was initially able to ambulate with support, but over 3 weeks, he became bedridden. However, there was no involvement of trunk, upper limbs and neck. The patient noticed no involuntary movements or loss of sensation in the lower limbs. One and half month into the illness, he noticed a loss of bladder sensation, inability to initiate micturition, overflow incontinence and erectile dysfunction. There was no history suggestive of bowel disturbance, memory impairment, speech disturbances or cranial nerve involvement. He did not report fever, cough, respiratory distress or contact history with a patient of tuberculosis. There was no history suggestive of high-risk behaviours. He consumed a mixed diet and did not report the consumption of unpasteurised milk.

The general physical examination was unremarkable except for healed herpetic lesions over the left scapula. Higher mental function evaluation and cranial nerve examination were within normal limits. The muscle bulk was reasonably preserved in all four limbs, and no asymmetry was noted. The tone in both the lower limbs was decreased as compared with the upper limbs. Power in the lower limbs was decreased (2/5). Deep tendon reflexes were absent in both the lower limbs, but the plantar response was extensor. The sensory system was normal, except for an impaired vibration sense. The cerebellar examination was normal in the upper limbs but it could not be done in the lower limbs.

Investigations

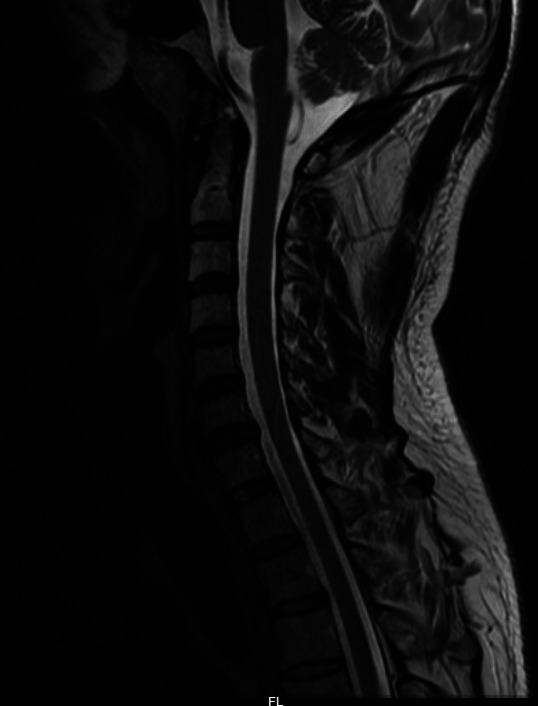

Routine laboratory investigations were unremarkable except for thrombocytopenia. Peripheral smear did not show any macrocytosis, and vitamin B12 levels were normal. Venereal disease research laboratory test and treponema pallidum haemagglutination assay from serum were negative. Contrast-enhanced MRI of the spine was normal (figure 1). An electromyogram was done which was reported as normal. As mandated by the national guidelines, a three-tiered testing algorithm was used for the diagnosis of HIV. This algorithm uses three different antibody-based tests that either target a differet antigen or are based on a different principle. The test was positive for HIV-1. An HIV-1 RNA viral load was sent which reported a viral load of 3.48×105 copies/mL. His CD4 count was 70 cells/μL. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed a cell count of 33 cells/μL (100% lymphocytes), a protein of 85 mg/dL and glucose of 154.3 mg/dL. CSF was also tested for tuberculosis, cytomegalovirus (CMV), syphilis, herpes zoster and varicella zoster virus, all of which turned out to be negative.

Figure 1.

T2-weighted images on sagittal section showing normal morphology and signal intensity of the spinal cord.

Differential diagnosis

The following clinical differentials were kept based on the history and examination findings: subacute combined degeneration (SACD), myeloradiculopathy, tabes dorsalis, motor neuron disease and multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction blocks. A provisional diagnosis of HIV vacuolar myelopathy versus HIV-related amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) was made based on examination and investigations (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of points in favour of or against various differentials of flaccid paraparesis in a patient with advanced HIV

| Points 'for' | Points 'against' |

| Subacute combined degeneration | |

| Impaired vibration sense Absent with extensor plantar |

Normal serum B12 levels |

| HIV amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | |

| Presence of UMN (extensor plantar) and LMN findings (bilateral lower limb hypotonia, absent deep tendon reflexes) | No evidence of wasting or fasciculations |

| HIV vacuolar myelopathy | |

| Paraparesis with LMN bladder and sexual dysfunction Extensor plantar Response to ART |

Absent deep tendon reflexes Flaccid paralysis |

| HIV myeloradiculopathy | |

| Paraparesis with LMN bladder and sexual dysfunction Absent deep tendon reflexes Response to ART |

CSF CMV PCR assay negative No radicular pain |

| Multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction blocks | |

| Slowly progressive asymmetric motor weakness Absent deep tendon reflexes |

Lack of involvement of the upper limbs No significant wasting/fasciculations |

| Chronic inflammatory demyelinating radiculopathy | |

| Pure motor involvement - distal and proximal Minimal or no sensory involvement |

Extensor plantar Response to ART |

| Acute motor axonal neuropathy | |

| Ascending paralysis with absent deep tendon reflexes No sensory involvement |

No preceding history of diarrhoea Improvement without treatment with IVIg or plasmapheresis |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; IVIg, intravenous immunoglobulin; LMN, lower motor neuron; NCV, nerve conduction velocity; UMN, upper motor neuron.

Treatment

The patient was started on antiretroviral therapy (ART) comprising of tenofovir, lamivudine and efavirenz as per the national guidelines for the management of HIV. Strict adherence to the medications was re-inforced.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was followed up after 6 months of the discharge. He showed an excellent response to the treatment and was able to walk independently without assistance and regained bladder control. His CD4+ had improved to 142 cells/mm3.

Discussion

This was a case of flaccid paraparesis in a patient with HIV. SACD and tabes dorsalis was considered as a possible differential because of absent jerks and extensor plantar response. However, nerve conduction studies did not show any large fibre involvement, and vitamin B12 levels were normal (table 1). Negative tests for syphilis in serum and CSF ruled out tabes dorsalis (table 1). Lower motor neuron findings, asymmetric onset and predominantly motor involvement suggested a possibility of multifocal motor neuropathy, but the presence of extensor plantar was against the diagnosis (table 1). Based on the positive HIV test, the asymmetric onset of progressive disease, predominant motor involvement, mixed upper and lower motor neuron findings, HIV-related ALS was considered. However, bladder involvement and erectile dysfunction were strong points against the same (table 1). Myeloradiculopathy was considered because of the back pain, presence of bladder involvement and impotence but the absence of sensory involvement, extensor plantar and normal MRI were against the diagnosis. Also, the CMV PCR assay in the CSF was negative.

HIV vacuolar myelopathy was a relatively common neurological complication in the pre-ART era, occurring in 5%–20% of adult patients with HIV in clinical studies. This has drastically reduced with the advent of ART to less than 10%. However, it remains the most common cause of chronic myelopathy associated with HIV.4 It usually presents as a posterolateral spinal cord syndrome manifesting as a slowly progressive spastic paraparesis with an impaired vibration sense, sensory ataxia, bowel and bladder disturbances and sexual dysfunction.4–7 The upper limbs usually remain uninvolved. HIV-associated myelopathy usually occurs in conjunction with peripheral neuropathies and opportunistic infections or malignancies of the central or peripheral nervous system primarily in previously established and advanced cases of HIV. HIV vacuolar myelopathy as the initial manifestation of the disease has been reported in a handful of patients.6 The exact pathogenesis underlying HIV vacuolar myelopathy is yet to be elucidated entirely despite numerous available theories illustrating the same. One such hypothesis propounds on the concept of inflammation secondary to neurotoxic cytokines released from HIV infected mononuclear cells. HIV induced direct infection of astrocytes, and neurons are not a significant feature of vacuolar myelopathy. Impaired myelin synthesis and maintenance due to improper vitamin B12 utilisation as a methionine source in transmethylation metabolism is another such proposed theory.5 8 The diagnosis of HIV-associated vacuolar myelopathy remains a diagnosis of exclusion, therefore requiring a detailed evaluation for the negation of other possible aetiologies. MRI usually reveals spinal cord atrophy at the thoracic level with or without concomitant cervical cord involvement.5 7 Although management for vacuolar myelopathy encompasses primarily symptomatic and supportive care, with no specific approved treatment, viral control with ART’s effective use can result in clinical and radiological improvement.4

Subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord is a close differential of vacuolar myelopathy. It is characterised by demyelination of the dorsal and lateral spinal cord. The exact mechanism of cobalamin deficiency-mediated neurological manifestations are incompletely understood; however, Central Nervous System (CNS) demyelination secondary to reduced S-adenosyl methionine or elevated methylmalonic acid may be involved.9 These patients present with polyneuropathy, impaired vibration sense, motor weakness, gait disturbance and intellectual impairment.9 10 MRI in patients with evidence of myelopathy would reveal a regional T2 and Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintensities mainly in the posterior column and extending into the brainstem.10 11 In the case of chronic disease, spinal cord atrophy may be seen. Nerve conduction velocity shows evidence of axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy in up to 80% of the patients.10 Once the diagnosis and underlying aetiology has been confirmed, parenteral or oral cobalamin replacement results in normalisation of haematological parameters. It also helps in halting the progression of neurological weakness with subsequent clinical improvement.10

There have been several reported cases of ALS-like syndromes in patients with HIV.12 These cases differ from classical ALS in several ways. First, they occur in a much younger age than expected in classical ALS and usually have a more rapidly progressive course. Second, many of these cases respond to treatment and may even improve after ART’s institution.12 13 A retrospective case series showed that the mean CD4 count was 86/mm3 in six patients diagnosed with ALS. All six patients showed partial or complete recovery after the initiation of ART.14 It is thought that the ALS-like disorder seen in HIV is driven by the high degrees of viral replication in the CNS compartment and hence improves with a clearance of the virus from CSF.

Multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction blocks is an immune-mediated demyelinating neuropathy that is a rare although close differential of ALS. It is characterised by gradually progressive weakness, cramping and fasciculations without any significant sensory involvement. Nerve conduction study (NCS) will demonstrate the presence of both demyelinating and axonal neuronal injury. Response to immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory therapy further assists in cinching the diagnosis.15

Myeloradiculopathy is commonly but not exclusively associated with CMV infections in HIV positive individuals.16 The incidence of CMV myeloradiculopathy has decreased significantly since the advent of ART. It usually presents as a rapidly progressive ascending flaccid paralysis with both urinary retention and bowel dysfunction. Reflexes may be reduced or absent. CSF analysis usually shows polymorphonuclear or monocytic leucocytosis with elevated CSF protein and hypoglycorrhachia. MRI often reveals enhancing lesions in the conus medullaris, cauda equina and lumbosacral nerve roots. The key to diagnosis is detecting CMV in CSF by PCR which is positive in >90% of the cases. Neurological deficits either improve or stabilise after treatment with antiviral therapy.17

Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) in HIV positive individuals is thought to occur during the phase of seroconversion when the CD4 cell counts are still high.18 It rarely occurs in patients with low CD4 counts. Cranial nerve involvement may be present along with autonomic disturbances characterised by arrhythmias, orthostatic hypotension and urinary retention.19 Electromyography with nerve conduction studies shows a primary demyelinating process with secondary axonal degeneration. The treatment for AIDP is with either plasmapheresis or intravenous immunoglobulin.19

Unlike AIDP, Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) can occur at any phase of the disease. CIDP typically present with distal and proximal weakness, areflexia or hyporeflexia along with mild sensory reports. Atrophy and fasciculations may be prominent in CIDP. Steroids are used for the management of patients with CIDP.

Patient’s perspective.

I have never been to the hospital in my entire life for anything. Never been sick, never skipped a day of work due to health-related reasons. I cannot pinpoint as to the exact date when this happened. I was just tired, unexplainably tired after doing the same amount of work that I did daily for years. There was also this unexplainable back pain that somehow seemed to always be there. Walking became a task; my footwear would fall off no matter how much I tried to hold on to them. I would stumble and trip while walking. When it seemed like these problems were only worsening and that I had to do something about it is when I first consulted a doctor. I was admitted to the hospital and evaluated by a team of doctors. I was diagnosed with HIV. That itself was a major blow for me. It took me a while to accept my diagnosis. I was put through a lot of tests and scans to confirm my neurological diagnosis, following which I was started on treatment. Until now, I have not skipped a single dose. There were times in between where I thought that things might not get back to how it was before, but once I saw the improvement, I became hopeful. Here I am now; I have started to go to work now.

Learning points.

Clinical history and a thorough examination is the key to the evaluation of non-traumatic paraparesis in patients with HIV.

Routine testing to rule out vitamin deficiencies and opportunistic infections should be done in patients with HIV paraparesis.

HIV vacuolar myelopathy should be considered as a differential in a patient presenting with slowly progressive paraparesis.

Antiretroviral therapy may halt or even recede the natural history of the disease in many cases of paraparesis due to HIV myelopathy or HIV amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Footnotes

Contributors: AJ and NG were involved in the conception of the work and drafting of the article. AJ, NG and KS were involved in the patient management. Critical revision and overall supervision of the report was done by KS.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Koppel BS, Wormser GP, Tuchman AJ, et al. Central nervous system involvement in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Acta Neurol Scand 1985;71:337–53. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1985.tb03211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy RM, Bredesen DE, Rosenblum ML. Neurological manifestations of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): experience at UCSF and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 1985;62:475–95. 10.3171/jns.1985.62.4.0475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snider WD, Simpson DM, Nielsen S, et al. Neurological complications of acquired immune deficiency syndrome: analysis of 50 patients. Ann Neurol 1983;14:403–18. 10.1002/ana.410140404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rezaie A, Parmar R, Rendon C, et al. Hiv-Associated vacuolar myelopathy: a rare initial presentation of HIV. SAGE Open Med Case Rep 2020;8:2050313X20945562 10.1177/2050313X20945562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madden GR, Fleece ME, Gupta A, Lopes MB, et al. Hiv-Associated vacuolar encephalomyelopathy. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019;6. 10.1093/ofid/ofz366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wuliji N, Mandell MJ, Lunt JM, et al. Hiv-Associated vacuolar myelopathy and HIV-associated dementia as the initial manifestation of HIV/AIDS. Case Rep Infect Dis 2019;2019:1–4. 10.1155/2019/3842425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Rocco A, Simpson DM. Aids-Associated vacuolar myelopathy. AIDS Patient Care STDs 1998;12:457–61. 10.1089/apc.1998.12.457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan SV, Guiloff RJ. Hypothesis on the pathogenesis of vacuolar myelopathy, dementia, and peripheral neuropathy in AIDS. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;65:23–8. 10.1136/jnnp.65.1.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gürsoy AE, Kolukısa M, Babacan-Yıldız G, et al. Subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord due to different etiologies and improvement of MRI findings. Case Rep Neurol Med 2013;2013:1–5. 10.1155/2013/159649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemmer B, Glocker FX, Schumacher M, et al. Subacute combined degeneration: clinical, electrophysiological, and magnetic resonance imaging findings. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;65:822–7. 10.1136/jnnp.65.6.822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravina B, Loevner LA, Bank W. Mr findings in subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord. Am J Roentgenol 2000;174:863–5. 10.2214/ajr.174.3.1740863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowen LN, Tyagi R, Li W, et al. HIV-Associated motor neuron disease. Neurology 2016;87:1756–62. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.John AA, Sharma S, Madhusudhan BK, et al. A rare presentation of reversible ALS in HIV infection. HIV & AIDS Review 2015;14:90–2. 10.1016/j.hivar.2015.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moulignier A, Moulonguet A, Pialoux G, et al. Reversible ALS-like disorder in HIV infection. Neurology 2001;57:995–1001. 10.1212/WNL.57.6.995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lange DJ, Weimer LH, Trojaborg W, et al. Multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction block: slow but not benign. Arch Neurol 2006;63:1778–81. 10.1001/archneur.63.12.1778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakobsen J, Smith T, Gaub J, et al. Progressive neurological dysfunction during latent HIV infection. BMJ 1989;299:225–8. 10.1136/bmj.299.6693.225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahieux F, Gray F, Fenelon G, et al. Acute myeloradiculitis due to cytomegalovirus as the initial manifestation of AIDS. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1989;52:270–4. 10.1136/jnnp.52.2.270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thornton CA, Latif AS, Emmanuel JC. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection in Zimbabwe. Neurology 1991;41:812–5. 10.1212/WNL.41.6.812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verma A. Epidemiology and clinical features of HIV-1 associated neuropathies. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2001;6:8–13. 10.1046/j.1529-8027.2001.006001008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]