Abstract

Introduction:

The outcome of laparoscopic extended cholecystectomy (EC) with wedge hepatic resection (LECW) in patients with gallbladder cancer (GBC) has been compared with that of open EC with wedge hepatic resection (OECW), but studies comparing laparoscopic EC with bi-segmentectomy (LECB) with open EC with bi-segmentectomy (OECB) are lacking.

Patients and Methods:

This retrospective study comprised of 68 patients with GBC who were offered either LECB or OECB from July 2011 to July 2018. Patients were divided into laparoscopic group (LG) and open group (OG), and appropriate statistical methods were used for comparison.

Results:

Out of the total 68 patients, 30 patients were in LG and 38 patients were in OG. Demographic, clinical and biochemical characteristics were similar except significantly higher number of male patients in OG (P = 0.01). In LG versus OG, the mean operation time was 286 versus 274 min (P = 0.565), mean blood loss was 158 versus 219 ml (P = 0.006) and mean hospital stay was 6.4 versus 9 days (P = 0.0001). The complication rate was 16.6% in LG and 31.5% in OG, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.259). The median number of lymph nodes was 12 in both LG and OG (P = 0.62). Distribution of patients among American Joint Committee on Cancer stages I to IV was similar in both the groups (P = 0.5). Fifty percent of the patients in both the groups received adjuvant treatment (P = 1). In LG versus OG, the recurrence rate was 20% versus 28.9% (P = 0.4), mean recurrence-free survival was 48 months versus 44 months (P = 0.35) and overall survival was 51 months versus 46 months (P = 0.45). In LG versus OG, 1, 3 and 5-year survival was 96% versus 94%, 79% versus 72% and 79% versus 62% (P = 0.45). The median follow-up was statistically significantly shorter (24 vs. 36 months) in LG versus OG (P = 0.0001).

Conclusions:

The oncological outcome and survival after LECB in patients with resectable GBC is not inferior to that after OECB. Laparoscopic approach has a potential to improve perioperative outcome in patients with GBC.

Keywords: Bi-segmentectomy, extended cholecystectomy, gallbladder cancer, laparoscopic, laparoscopic versus open, radical cholecystectomy

INTRODUCTION

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is the most common cancer of the biliary tract, and it has tendency to spread early.[1,2] Because of early spread and lack of specific symptoms, most patients with GBC are detected late when cure may be unlikely.[1] Neoadjuvant treatment for patients with locally advanced GBC (T3/T4) is still in evolution phase; therefore, surgery is the preferred treatment modality for potentially resectable GBC.[1] Extended (or radical) cholecystectomy (EC) has been the 'standard of care' for most patients with resectable GBC.[1,3] EC comprises of en bloc resection of gallbladder (GB) with a part of adjoining liver and the regional lymph nodes (LNs) (N1).[1,2,3] The optimum extent of hepatic resection in EC is mainly dependent on T stage, site of the involvement of GB and practices of a surgeon.[1,2,3,4,5,6] Kai et al. reported EC with bi-segmentectomy s4a and 5 (ECB) as an adequate treatment for pT2 GBC and also mentioned that ECB may provide a long-term survival in patients with pT3 and T4 GBC provided R0 resection is achieved. Horiguchi et al. compared the outcome of EC with wedge resection (ECW) with ECB s4a and 5 in patients with pT2 GBC and reported no difference in survival.[7]

Gumbs et al. reported laparoscopic ECB (LECB) in a patient with suspected GBC; however, the final histology was benign in this patient.[8] Gumb and Hoffman reported successful laparoscopic EC (LEC) in three patients with incidental GBC (IGBC).[9] Machado et al. also reported totally laparoscopic hepatic bi-segmentectomy (s4b and 5) in a patient with T1b IGBC.[10] Agarwal et al. compared LEC with wedge resection (LECW) and open ECW resection of hepatic segments 4b and 5 and concluded that laparoscopic approach is safe and feasible in selected patients with GBC, and the results were also comparable to those of open approach.[11] We compared the outcome of laparoscopic extended cholecystectomy involving bi-segmentectomy 4b and 5 (LECB) to that of open ECB 4b and 5 (OECB) in patients with resectable GBC and hereby report our results.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This retrospective study was conducted at a tertiary care centre in northern part of India. The duration of study was from July 2011 to July 2018. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients. As per institutional guidelines, approval from the committee of ethics was not required. Medical records of the patient with GBC were reviewed to collect data about patients who were treated with LECB or OECB. Pre-operative blood investigations included complete blood counts, liver function test (LFT), renal function test, international normalized ratio, serum markers for viral hepatitis B and C, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) and carcinoembryonic antigen. Radiological investigations included chest X-ray, real-time ultrasound of the abdomen and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was advised to look for locoregional LN metastasis. EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology was performed if metastatic involvement of coeliac, pancreaticoduodenal and inter-aortocaval LN was suspected. Patients with proved metastasis to coeliac LN/pancreaticoduodenal LN/inter-aortocaval LN/distant metastasis were referred for chemotherapy, and all such patients were excluded from the study. Patients with radiological evidence of involvement of portal vein, bile duct and hepatic artery were also excluded from the study. Most of the patients with definite evidence of involvement of extrahepatic organs such as duodenum and colon were considered for open surgery. Some of the patients in laparoscopic group (LG) were detected to have suspected involvement of extrahepatic organs during surgery and were included in LG, and an intention-to-treat analysis was performed. Patients detected to have unresectable disease on staging laparoscopy (SL) or later during the surgery were excluded from the study. Patients who received neoadjuvant treatment were excluded from the study. Adjuvant treatment was advised in patients with GBC >T2 and/or LN metastasis and/or with positive resection margins (R1/R2 resections). The American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition (AJCC 8th) classification system (tumour–node–metastasis) was used for disease stratification.[12] Post-operative complications were classified as described by Dindo et al.[13]

Technique of laparoscopic extended cholecystectomy with bi-segmentectomy

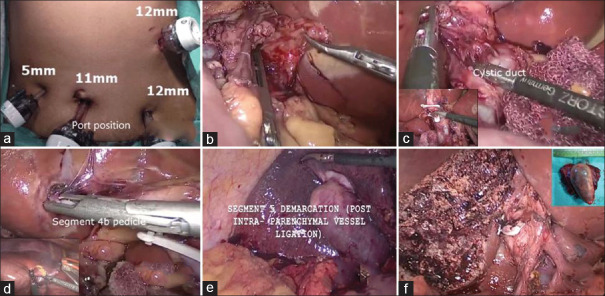

Patients were placed in 'reverse Trendelenburg position' with mild abduction of bilateral hip joints. Pneumoperitoneum was created by open method, and a total of five access ports (Endopath Xcel trocar, Ethicon Endo surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA) were used [Figure 1a]. The chief surgeon and the scrub nurse were on the left side of the patient, the first assistant surgeon was along the lower limbs of the patient and the second assistant surgeon was on the right side of the patient. A camera monitor unit was installed against the right shoulder of the patient. Intra-abdominal pressure was maintained at 10 mmHg. SL was performed through umbilical port, and surgery was abandoned if distant metastasis was confirmed on frozen biopsy. After SL, LNs along the hepatic artery and its branches, portal vein and bile duct posterior to the first part of the duodenum were removed [Figure 1b]. The GB was gently held with a fenestrated atraumatic forceps (KARL STORZ SE & Co. KG, Tuttlingen, Germany) to expose the hepatocystic triangle. The enough length of cystic artery and cystic duct was exposed to enable safe application of Hem-o-lock clips (Teleflex medicals, Durham, NC, USA) and to ensure enough margin of cystic duct for frozen biopsy [Figure 1c]. In the process of preparation for Pringle's manoeuvre, a 10 Fr polyvinyl tube (Romsons Scientific & Surgical Pvt. Ltd., Agra, UP, India) was used to encircle the structure contained in the hepatoduodenal ligament. This tube was brought out through a customised tube made from 34 to 36 Fr abdominal drainage tube (Romsons Scientific & Surgical Pvt. Ltd, Agra, UP, India). During hepatic transection, the central venous pressure was maintained below 5 mmHg. The portal pedicle of hepatic segment 4b (some authors referred as 4a) was approached through umbilical fissure and all the branches to s4b were ligated and divided [Figure 1d]. An ultrasonic dissector (Gen 4, Ethicon Endosurgery, USA) was used for parenchymal transection along the ischaemic demarcation line of s4b [Figure 1d inset]. The portal pedicle to hepatic segment 5 (s5) was approached through intraparenchymal dissection. Trial clamping of the s5 pedicle was done for confirmation and to avoid injury to the adjacent portal branches; the demarcation line guided resection of s5 and completion of bi-segmentectomy [Figure 1e and f]. If there was significant bleeding from the branches of middle hepatic vein, then suture ligation was done under Pringle's manoeuvre. The resected specimen was transferred to an endobag and delivered out through a small subcostal/infra-umbilical incision after achieving a satisfactory haemostasis. The peritoneal cavity was drained with a 24 Fr drainage tube (Romsons, India) in the right subhepatic space.

Figure 1.

(a) Port position. (b) Excision of regional lymph nodes. (c) Dissection of hepato-cystic triangle with inset showing excision of cystic duct margin for frozen biopsy. (d) Ligation of portal pedicle to hepatic segment 4b with inset showing transaction of parenchyma (s4b) along the demarcation line. (e) Ischaemic demarcation line after ligation of portal pedicle to hepatic segment 5. (f) Liver surface after completion of bi-segmentectomy s4b and s5 with inset showing resected specimen

Technique of open extended cholecystectomy with bi-segmentectomy

Patients were placed in supine position, and a right subcostal incision with partial extension to the left was used for laparotomy. The principles and technique of OECB were similar to that of LECB except the use of instruments and equipment designed for open surgery.

Statistical analysis

Statistical package IBM SPSS version 25 for Windows (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Numerical data were represented as mean and median. Categorical and ordinal data were represented as percentages. Parametric numerical data were compared with t-test. Non-parametric numerical data were compared with Mann Whitney U Test. Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used to compare categorical and ordinal data, respectively. Kaplan–Meier method and Cox regression method were used for survival analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Follow-up

Patients visited the outpatient department at every 3 months for the first 2 years and thereafter at every 6 months to death (events) or until they lost to follow-up (censored/free events). Clinical examination, including LFT, tumour markers and ultrasound of the abdomen, was advised at every visit. CECT and/or fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography was advised selectively.

RESULTS

The demographic, clinical, operative and post-operative parameters are depicted in Table 1. The total number of patients was 68: LG included 30 patients and open group (OG) included 38 patients. The mean age of the patients was 49 years in both the groups, but the number of male patients was higher in OG (P = 0.01). Serum bilirubin level, serum CA-19-9 level and percentage of patients with IGBC were similar in both the groups [Table 1]. In LG versus OG, the mean operation time was 286 versus 274 min (P = 0.565), the mean blood loss was 158 versus 219 ml (P = 0.006) and the mean hospital stay was 6.4 versus 9 days (P = 0.0001). Five patients in LG and 11 patients in OG required various procedures in addition to LECB or OECB (P = 0.2). Seven patients (23.3%) in LG required conversion to open approach because of distortion of anatomical landmarks and/or technical difficulty encountered due to suspected involvement of extrahepatic organs. Out of these seven patients, one patient required ligation of the right hepatic artery, three patients required bile duct excision with bilioenteric anastomosis, one patient required segmental resection of colon and duodenum with gastrojejunostomy and colocolostomy and one patient required sleeve resection of transverse colon. The incidence of complication was 16.6% (n = 5) in LG and 31.5% (n = 12) in OG, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.259). None of the patients in LG developed complication beyond Grade II [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic, clinical, operative and postoperative parameters

| Parameters | Lap (n=30) | Open (n=38) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD | 49.6±12.8 | 49±10.1 | 0.838 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 3 (10) | 15 (39.4) | 0.011 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 7 (23.3) | 5 (13.1) | 0.344 |

| Incidental GBC, n (%) | 11 (36.6) | 6 (15.7) | 0.089 |

| Serum bilirubin (mg/dl), mean±SD | 0.5±0.2 | 0.9±1.2 | 0.076 |

| Preoperative haemoglobin (g/dl), mean±SD | 10.6±1.5 | 11.4±2.3 | 0.133 |

| Serum albumin (mg/dl), mean±SD | 3.7±0.5 | 3.7±0.5 | 0.811 |

| Serum CA19-9 (U/ml), mean±SD | 15.9±21.5 | 20.2±35.1 | 0.561 |

| Blood loss (ml), mean±SD | 158.6±85.7 | 219.4±87.7 | 0.006 |

| Duration of surgery (min), mean±SD | 286.5±71.6 | 274.2±96.3 | 0.565 |

| Hospital stay (days), mean±SD | 6.4±3.1 | 9±8.0 | 0.0001 |

| Additional procedure performed, n (%) | 5 (16.6) (bile duct excision: 3, segmental colonic + duodenal resection: 1, colonic sleeve resection: 1) | 11 (28.9) (bile duct excision: 6, bile duct excision + distal gastrectomy: 1, colonic resection: 3, segmental duodenal resection: 1) | 0.266 |

| Complications, n (%) | |||

| Overall | 5 (16.6) | 12 (31.5) | 0.259 |

| Grade I | 3 (10) | 5 (13.1) | |

| Grade II | 2 (6.6) | 3 (7.8) | |

| Grade III | 0 | 1 (2.6) | |

| Grade IV | 0 | 2 (5.2) | |

| Grade V | 0 | 1 (2.6) |

GBC: Gallbladder cancer, SD: Standard deviation, CA: Carbohydrate antigen, LG: Laparoscopic group, OG: Open group

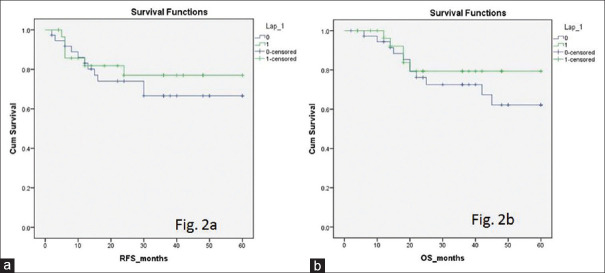

Oncological parameters, histopathological characteristics and survivals are summarised in Table 2. All the resection margins were free (R0) in patients of LG, whereas in OG, one patient (2.6%) had positive hepatic resection margin (P = 0.9). The median number of LNs examined was 12 in both the groups (P = 0.62). The mean of minimum hepatic margin was 13.5 mm in LG and 15.9 mm in OG. Distribution of patients among different AJCC stages (I–IV), T stages (T1–T4) and N stages (N0–N2) was not different [Table 2]. Tumour type and tumour grade were comparable between LG and OG. The proportion of patients received adjuvant treatment was comparable. Adjuvant treatment comprised of chemotherapy alone in all but one patient; a single patient in OG received chemoradiotherapy. The median follow-up was 24 months in LG and 36 months in OG (P = 0.0001). Recurrence could be detected in six patients (20%) of LG and in 11 (28.9%) patients of OG (P = 0.41). Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was 48.6 months in LG and 44.6 months in OG (P = 0.3); overall survival (OS) was 51 months in LG and 46 months in OG (P = 0.4) [Figure 2]. One-, 3 and 5-year survival was higher in LG than in OG, but it was not statistically significant [Figure 2b]. The number of censored patients was 25 (83.3%) in LG and 26 (70.3%) in OG.

Table 2.

Comparison of oncological outcome and survival

| Parameters | LG (n=30) | OG (n=38) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph nodes, mean±SD | 11.9±5.2 | 12.7±4.2 | 0.503 |

| Negative margins (R0), n (%) | 30 (100) | 37 (97.3) | 0.9 |

| Minimum hepatic margin, (mm), mean±SD | 13.5±5.8 | 15.9±12.2 | 0.371 |

| GBC stage (AJCC 8th Ed.), n (%) | |||

| Stage 1 | 8 (26.6) | 5 (13.1) | 0.556 |

| Stage 2 | 8 (26.6) | 12 (31.5) | |

| Stage 3 | 10 (33.3) | 16 (42.1) | |

| Stage 4 | 4 (13.3) | 5 (13.1) | |

| T stage, n (%) | T1: 8 (26.6) | 6 (15.7) | 0.530 |

| T2:12 (40) | 17 (44.7) | ||

| T3:8 (26.6) | 15 (39.4) | ||

| T4:2 (6.6) | 0 (0) | ||

| N stage, n (%) | N0: 20 (66.7) | 25 (65.7) | 0.732 |

| N1: 7 (23.3) | 7 (18.4) | ||

| N2:3 (10) | 6 (15.7) | ||

| Histological type | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 25 | 30 | 0.206 |

| Adenosquamous | 0 | 4 | |

| Intracystic papillary | 4 | 4 | |

| Neuroendocrine | 1 | 0 | |

| Tumour differentiation | |||

| Well differentiated | 11 | 8 | 0.045 |

| Moderately differentiated | 19 | 24 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 0 | 6 | |

| Vascular/lymphatic microinvasion | |||

| Yes | 8 | 13 | 0.504 |

| No | 22 | 25 | |

| Fundus | 17 | 23 | 0.534 |

| Fundus and body | 6 | 5 | |

| Body | 5 | 4 | |

| Neck | 2 | 6 | |

| Recurrence, n (%) | 6 (20) | 11 (28.9) | 0.410 |

| Local recurrence, n (%) | 4 (13.3) | 6 (15.7) | 0.627 |

| Distant metastasis, n (%) | 2 (6.7) | 5 (13.1) | |

| Adjuvant treatment, n (%) | 15 (50) | 19 (50) | 1.0 |

| Median follow-up (months) | 24 | 36 | 0.0001 |

| RFS (months), mean±SE | 48.6±4.1 | 44.6±3.8 | 0.352 |

| Overall survival (months), mean±SE | 51.0±3.58 | 46.4±3.39 | 0.457 |

| One-year survival (%) | 96 | 94 | 0.457 |

| Three-year survival (%) | 79 | 72 | |

| Five-year survival (%) | 79 | 62 |

GBC: Gallbladder cancer, SE: Standard error, LG: Laparoscopic group, OG: Open group, AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer, RFS: Recurrence-free survival

Figure 2.

(a) Recurrence-free survival curve. (b) Overall survival curve

DISCUSSION

The basic surgical principle in patients with GBC is to achieve negative resection margins (R0) because in patients with positive resection margins (R1/R2), survival is poor or equivalent to that without surgical resection.[1,14] Hepatic micro-metastasis is the most common mode of spread in GBC, and about 70% of early metastatic foci occur in segment 4b and 5; therefore, resection bi-segmentectomy s4b and 5 was considered an adequate hepatic resection for patients with subserosal invasion by Endo et al.[15] Endo et al. further studied the clinical significance of micro-metastasis in twenty patients with pT2 GBC and found hepatic micro-metastasis in five patients which were predominantly located within 1 cm of GB and hepatic metastasis showed a strong correlation with the extent of blood vessel invasion and four of five patients with hepatic micro-metastasis died due to recurrence in remnant liver.[16] Yoshikawa studied 201 patients of GBC and suggested that resection of segment IV inferior (s4b) and segment V (s5) of the liver may be beneficial in patients with liver bed-type invasion <20 mm in depth. Scheingraber et al. and Suzuki et al. also recommended bi-segmentectal hepatic resection.[17,18,19] However, Goetze and Paolucci studied 883 of IGBC patients and recommended that wedge or non-anatomical hepatic resection technique is an effective procedure for T1b and T2 IGBC but for T3 tumours requiring more radical operation.[20] Horiguchi et al. compared the outcome of ECB to that of ECW in patients with pT2 GBC and reported similar survival with both the techniques.[8] D'Angelica et al. also analysed the extent of hepatic resection in patients with GBC and concluded that it is the tumour biology rather that the extent of hepatic resection which decides prognosis in patients with resectable GBC.[5] The basis for the recommendation of bi-segmentectomy over wedge resection of liver was the pattern of venous drainage of GB consequent to that of a relatively high risk of occurrence of metastasis in segments 4b and 5 of liver, but several authors have reported comparable outcome after ECW provided R0 resection could be achieved.[5,8,21,22]

Gumb and Hoffman reported LECB in three patients with IGBC and later on other authors also published their experience about LECW and LECB in patients with GBC.[9,10,11,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] Piccolo and Piozzi reviewed published literature regarding laparoscopic management of 129 patients and observed that most patients with laparoscopic radical cystectomy were with pT2 GBC; both LECW and LECB were performed; LN count ranged from 3 to 21; bile leakage was the most common complication and 5-year survival was from 68.7 to 90.7 months.[30] Palanisamy et al. (2016) reported 14 patients with LECB with a mean operation time of 212 min, blood loss of 194 ml and hospital stay of 5 days.[26] Ratti et al. compared the long-term outcome of laparoscopic versus open EC and reported lower blood loss (200 vs. 350 ml) and shorter hospital stay (4 vs. 6 days) in LG; however, there was no difference regarding LN count and survival, but this study included patients with cholangiocarcinoma and GBC.[31] Feng et al. also reported shorter hospital stay (5.8 vs. 9.5 days) in laparoscopic arm; however, complication and survival were comparable to open approach.[32] Recently, Jang et al. also compared laparoscopic and open surgery in pT2 GBC and reported significantly shorter hospital stay (5.8 vs. 9.5 days) and higher diseasefree survival with laparoscopic approach, but there was no difference in OS.[33] We observed significantly lower blood loss and shorter hospital stay in LG, whereas most of other parameters were comparable to OG.

A high conversion rate in our study was mainly due to inclusion of patients with extrahepatic organ involvement and a low threshold for conversion to ensure patient safety. Patients with extrahepatic organ involvement require more tissue manipulation and dissection which increases the risk of iatrogenic tumour rupture; therefore, we prefer to convert such patients as and when its detected. In seven patients, we missed extrahepatic organ involvement on preoperative imaging and it was detected during laparoscopic evaluation and/or dissection after completing SL; therefore, we included them in LG. In order to avoid excessive dissection and tissue manipulation, we prefer to keep a low threshold for conversion because tumour rupture and/or bile leak may lead to dissemination of an otherwise resectable GBC. Earlier, Z'graggen et al. have reported 40% recurrence rate in patients with GB perforation and 9% recurrence rate in patients without GB perforation.[34] Fong et al. also cautioned against the hazard of laparoscopic violation of GB integrity in patients with GBC and suggested modification of management based on awareness of such hazard.[35] The matter of port site/peritoneal metastasis was discussed during a recent consensus meeting and experts were of opinion that risk of port site/peritoneal metastasis has been abated by improved preoperative recognition and careful manipulation to avoid bile spillage; the outcome of laparoscopic surgery in early stage GBC is not inferior to open surgery; however, experience with LEC is limited to few centres; therefore, more evidence is required to draw a final conclusion on this matter.[36]

In our study, recurrence rate, RFS and OS in LG were comparable to those of OG. None of the patients in LG had positive resection margin on histological examination and no port site recurrence was encountered. We could not get an estimate of median survival because survival probability in both the arms was >0.5 and there was a high prevalence of free events (censored patients) in both the groups. It is apparent from our results that a good survival may be achieved in patients with GBC after LECB. Palanisamy et al. (2016) reported cumulative 5-year survival of 68% and Zhang et al. reported OS as 78.5%.[26,37] In both these studies, LEC was performed. Wakabayashi et al. reported a survival rate of 83.3% in Stage III, 46.2% in Stage IVA and 16.7% in Stage IV b.[38] Suzuki et al. reported a 5year survival of 77% (in pT2 GBC).[19] Several other authors have also reported improvement in survival even in patients with advance GBC.[1] Adjuvant chemotherapy also had a positive impact on survival in both LG and OG in our study. Positive impact of adjuvant chemotherapy has been reported by Takada et al., (2002) Ma et al. and Kasumova et al.[39,40,41] A recent survey result revealed that laparoscopic surgery for GBC is performed in highly selected cases; however, present opinion and evidence suggest that LEC for GBC will be performed more frequently in the future.[42]

CONCLUSIONS

The oncological outcome and survival after LECB in patients with resectable GBC is not inferior to that after OECB. Laparoscopic approach has a potential to improve perioperative outcome in patients with GBC.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank our patients and all the supportive departments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jarnagin WR, Allen PJ, Chapman WC, D'Angelica MI, DeMatteo RP, Gian RK, et al. Blumgart Jeejo's and KK's Surgery of the Liver and Biliary Tract, and Pancreas. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017. pp. 786–804. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wakai T, Shirai Y, Sakata J, Nagahashi M, Ajioka Y, Hatakeyama K. Mode of hepatic spread from gallbladder carcinoma: An immunohistochemical analysis of 42 hepatectomized specimens. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:65–74. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181c467d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glenn F, Hays DM. The scope of radical surgery in the treatment of malignant tumors of the extrahepatic biliary tract. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1954;99:529–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamaguchi K, Chijiiwa K, Shimizu S, Yokohata K, Tsuneyoshi M, Tanaka M. Anatomical limit of extended cholecystectomy for gallbladder carcinoma involving the neck of the gallbladder. Int Surg. 1998;83:21–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Angelica M, Dalal KM, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR, et al. Analysis of the extent of resection for adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:806–16. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy SK, Marroquin CE, Kuo PC, Pappas TN, Clary BM. Extended hepatic resection for gallbladder cancer. Am J Surg. 2007;194:355–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horiguchi A, Miyakawa S, Ishihara S, Miyazaki M, Ohtsuka M, Shimizu H, et al. Gallbladder bed resection or hepatectomy of segments 4a and 5 for pT2 gallbladder carcinoma: Analysis of Japanese registration cases by the study group for biliary surgery of the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:518–24. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0584-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gumbs AA, Milone L, Geha R, Delacroix J, Chabot JA. Laparoscopic radical cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:519–20. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gumbs AA, Hoffman JP. Laparoscopic completion radical cholecystectomy for T2 gallbladder cancer. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:3221–3. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machado MA, Makdissi FF, Surjan RC. Totally laparoscopic hepatic bisegmentectomy (s4b+s5) and hilar lymphadenectomy for incidental gallbladder cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(Suppl 3):S336–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4650-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agarwal AK, Javed A, Kalayarasan R, Sakhuja P. Minimally invasive versus the conventional open surgical approach of a radical cholecystectomy for gallbladder cancer: A retrospective comparative study. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:536–41. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Switzerland: Springer; 2017. pp. 303–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kai M, Chijiiwa K, Ohuchida J, Nagano M, Hiyoshi M, Kondo K. A curative resection improves the postoperative survival rate even in patients with advanced gallbladder carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1025–32. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Endo I, Takimoto A, Fujii Y, Togo S, Shimada H. Hepatic resection for advanced carcinoma of the gallbladder. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1998;99:711–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Endo I, Shimada H, Takimoto A, Fujii Y, Miura Y, Sugita M, et al. Microscopic liver metastasis: Prognostic factor for patients with pT2 gallbladder carcinoma. World J Surg. 2004;28:692–6. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshikawa T, Araida T, Azuma T, Takasaki K. Bisubsegmental liver resection for gallbladder cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:14–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheingraber S, Justinger C, Stremovskaia T, Weinrich M, Igna D, Schilling MK. The standardized surgical approach improves outcome of gallbladder cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:55. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki S, Yokoi Y, Kurachi K, Inaba K, Ota S, Azuma M, et al. Appraisal of surgical treatment for pT2 gallbladder carcinomas. World J Surg. 2004;28:160–5. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7080-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goetze TO, Paolucci V. Incidental T1b-T3 gallbladder carcinoma. Extended cholecystectomy as an underestimated prognostic factor-results of the German registry. Chirurg. 2014;85:131–8. doi: 10.1007/s00104-013-2587-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugita M, Ryu M, Satake M, Kinoshita T, Konishi M, Inoue K, et al. Intrahepatic inflow areas of the drainage vein of the gallbladder: Analysis by angio-CT. Surgery. 2000;128:417–21. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.107380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shirai Y, Yoshida K, Tsukada K, Muto T, Watanabe H. Radical surgery for gallbladder carcinoma. Long-term results. Ann Surg. 1992;216:565–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199211000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho JY, Han HS, Yoon YS, Ahn KS, Kim YH, Lee KH. Laparoscopic approach for suspected early-stage gallbladder carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2010;145:128–33. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Itano O, Oshima G, Minagawa T, Shinoda M, Kitago M, Abe Y, et al. Novel strategy for laparoscopic treatment of pT2 gallbladder carcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:3600–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4116-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoon YS, Han HS, Cho JY, Choi Y, Lee W, Jang JY, et al. Is laparoscopy contraindicated for gallbladder cancer. A 10-year prospective cohort study. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:847–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palanisamy S, Patel N, Sabnis S, Palanisamy N, Vijay A, Palanivelu P, et al. Laparoscopic radical cholecystectomy for suspected early gall bladder carcinoma: Thinking beyond convention. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2442–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nag HH, Raj P, Sisodia K. The technique of laparoscopic hepatic bisegmentectomy with regional lymphadenectomy for gallbladder cancer. J Minim Access Surg. 2018;14:124–9. doi: 10.4103/jmas.JMAS_181_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castro CM, Santibañez SP, Rivas TC, Cassis NJ. Totally laparoscopic radical resection of gallbladder cancer: Technical aspects and long-term results. World J Surg. 2018;42:2592–8. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4490-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng G, Teo NZ, Goh BK. Short-term outcomes of minimally invasive surgery for patients presenting with suspected gallbladder cancer: Report of 8 cases. J Min Access Surg. 2019;15:109–14. doi: 10.4103/jmas.JMAS_229_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piccolo G, Piozzi GN. Laparoscopic radical cholecystectomy for primary or incidental early gallbladder cancer: The new rules governing the treatment of gallbladder cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:8570502. doi: 10.1155/2017/8570502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ratti F, Fiorentini G, Cipriani F, Paganelli M, Catena M, Aldrighetti L. Perioperative and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic versus open lymphadenectomy for biliary tumors: A Propensity-score-based, case-matched analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:564–75. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6811-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng JW, Yang XH, Liu CW, Wu BQ, Sun DL, Chen XM, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic and open approach in treating gallbladder cancer. J Surg Res. 2019;234:269–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jang JY, Han HS, Yoon YS, Cho JY, Choi Y. Retrospective comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic and open surgery for T2 gallbladder cancer-thirteen-year experience. Surg Oncol. 2019;29:142–7. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2019.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Z'graggen K, Birrer S, Maurer CA, Wehrli H, Klaiber C, Baer HU. Incidence of port site recurrence after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for preoperatively unsuspected gallbladder carcinoma. Surgery. 1998;124:831–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fong Y, Brennan MF, Turnbull A, Colt DG, Blumgart LH. Gallbladder cancer discovered during laparoscopic surgery. Potential for iatrogenic tumor dissemination. Arch Surg. 1993;128:1054–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420210118016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han HS, Yoon YS, Agarwal AK, Belli G, Itano O, Gumbs AA, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for gallbladder cancer: An expert consensus statement. Dig Surg. 2019;36:1–6. doi: 10.1159/000486207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang LF, Hou CS, Xu Z, Guo LM, Ling XF, Wang LX, et al. Laparoscopic treatment for incidental gallbladder cancer: A retrospective 10 years study from a single institution. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2019;57:277–81. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5815.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wakabayashi H, Ishimura K, Hashimoto N, Otani T, Kondo A, Maeta H. Analysis of prognostic factors after surgery for stage III and IV gallbladder cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:842–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takada T, Amano H, Yasuda H, Nimura Y, Matsushiro T, Kato H, et al. Is postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy useful for gallbladder carcinoma. A phase III multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial in patients with resected pancreaticobiliary carcinoma? Cancer. 2002;95:1685–95. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma N, Cheng H, Qin B, Zhong R, Wang B. Adjuvant therapy in the treatment of gallbladder cancer: A meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:615. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1617-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kasumova GG, Tabatabaie O, Najarian RM, Callery MP, Ng SC, Bullock AJ, et al. Surgical management of gallbladder cancer: Simple versus extended cholecystectomy and the role of adjuvant therapy. Ann Surg. 2017;266:625–31. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoon YS, Han HS, Agarwal A, Belli G, Itano O, Gumbs AA, et al. Survey results of the expert meeting on laparoscopic surgery for gallbladder cancer and a review of relevant literature. Dig Surg. 2019;36:7–12. doi: 10.1159/000486208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]