Abstract

Objectives

In the United States, nursing facility residents comprise fewer than 1% of the population but more than 40% of deaths due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Mitigating the enormous risk of COVID-19 to nursing home residents requires adequate data. The widely used Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) COVID-19 Nursing Home Dataset contains 2 derived statistics: Total Resident Confirmed COVID-19 Cases per 1000 Residents and Total Resident COVID-19 Deaths per 1000 Residents. These metrics provide a misleading picture, as facilities report cumulative counts of cases and deaths over different time periods but use a point-in-time measure as proxy for number of residents (number of occupied beds in a week), resulting in inflated statistics. We propose an alternative statistic to better illustrate the burden of COVID-19 cases and deaths across nursing facilities.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting and Participants

Using the CMS Nursing Home Compare and COVID-19 Nursing Home Datasets, we examined facilities with star ratings and COVID-19 data passing quality assurance checks for each reporting period from May 31 to August 16, 2020 (n = 11,115).

Methods

We derived an alternative measure of the number of COVID-19 cases per 1000 residents using the net change in weekly census. For each measure, we compared predicted number of cases/deaths by overall star rating using negative binomial regression with constant dispersion, controlling for county-level cases per capita and nursing home characteristics.

Results

The average number of cases per 1000 estimated residents using our method is lower compared with the metric using occupied beds as proxy for number of residents (44.8 compared with 66.6). We find similar results when examining number of COVID-19 deaths per 1000 residents.

Conclusions and Implications

Future research should estimate the number of residents served in nursing facilities when comparing COVID-19 cases/deaths in nursing facilities. Identifying appropriate metrics for facility-level comparisons is critical to protecting nursing home residents as the pandemic continues.

Keywords: Nursing homes, coronavirus, measurement

Nursing facility residents comprise fewer than 1% of the US population, yet they accounted for more than 40% of deaths due to COVID-19 in 2020.1 Addressing the enormous risk of COVID-19 to nursing home residents and what can be done to mitigate this risk requires adequate data, largely missing early in the pandemic.2 On June 4, 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released the first installment of the COVID-19 Nursing Home Dataset. The dataset contains facility-reported statistics from Medicare- and/or Medicaid-certified nursing facilities on the weekly and cumulative number of COVID-19 confirmed resident cases; COVID-19 resident deaths; and total number of currently occupied beds. Two important derived statistics that attempt to scale the number of cases and deaths to the size of the facility are also provided: Total Resident Confirmed COVID-19 Cases per 1000 Residents and Total Resident COVID-19 Deaths per 1000 Residents. These statistics inform CMS pandemic-related policy in nursing homes, as alluded to in a CMS press release.3 However, there are 2 reasons the measures are unsuitable for comparing COVID-19 burden across facilities: the variables are (1) calculated using counts of cases/deaths over inconsistent time periods across facilities, and (2) scaled by the number of occupied beds at a point in time, and not as the variable name suggests, the cumulative number of residents the facility has served. This inconsistency in the time periods for calculating the cumulative numbers of residents and cases/deaths yields inflated statistics. Using inflated statistics to inform policy decisions may potentially lead to misallocation of limited resources.

In this study, we propose an alternative statistic that more accurately illustrates the burden of COVID-19 cases and deaths in nursing facilities.

Methods

Data and Sample

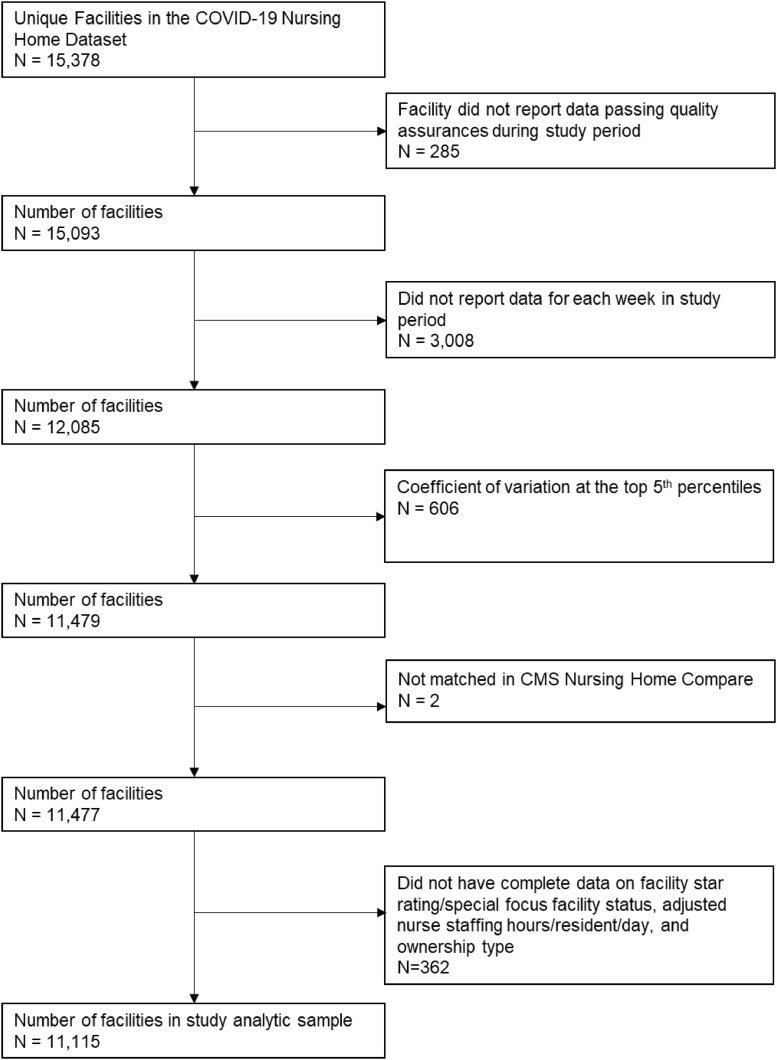

Using the COVID-19 Nursing Home Dataset released on August 25, 2020, we limited the study to facilities with data passing the CMS quality assurance check for all 12 weekly reporting periods May 31, 2020, to August 16, 2020. Facilities reported the number of occupied beds each week, thus reflecting changes in the resident census. For each facility, we calculated a coefficient of variation (CV, a standardized measure indicating variation of data) for the total number of occupied beds and excluded facilities in the top 5% to remove facilities with any potential data quality concerns. We estimated county-level COVID-19 cases per capita for the same reporting period (May 31, 2020, to August 16, 2020) using confirmed cases and population estimates from USAFACTS.org. We also used Nursing Home Compare, which includes overall star ratings, state, ownership type, and adjusted total nurse staffing hours per resident per day. We created a 3-level variable for nursing home rating: below average (Special Focus Facility or 1 or 2 stars), average (3 stars), and above average (4 or 5 stars). Special focus facilities have been flagged for prolonged quality concerns and do not receive a star rating. The final analytic sample size was 11,115 (study flow in Supplementary Figure 1).

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Study flow.

Replication

Our first objective was to replicate the CMS-derived facility-specific statistic of “total resident confirmed COVID-19 cases per 1000 residents” for the most recent reporting period (week ending August 16, 2020) by dividing the reported number of cumulative confirmed COVID-19 cases by the number of total occupied beds and then multiplying by 1000 (Equation 1).

| (1) |

The reporting period for the cumulative cases varies by facility and could reflect cases beginning as early as January 1, 2020, or as late as May 8.4 Similarly, we replicated the “total resident COVID-19 deaths per 1000 residents” using the same method with cumulative confirmed and suspected COVID-19 deaths reported per facility.

Estimated Number of Nursing Facility Residents and Proposed Alternative Measure

We derived an alternative measure to capture cumulative cases/deaths from May 25 through August 16 scaled by the estimated number of residents over that same period. The CMS COVID-19 Nursing Home dataset includes the weekly number of admissions due to COVID-19 and weekly deaths (for any reason). We calculated the net change in census by facility from the week prior due to non–COVID-19 admissions and discharges. If a net change is positive, then a facility admitted more people than discharged/died; that is, there were additional residents due to non-COVID admissions. We then added the number of COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 admissions to the facility's initial reported census, thereby estimating the number of total residents per facility during the study period (see Supplementary Table 1 for calculation). Notably, this estimate is undoubtedly an undercount of total residents, as it is possible that residents are admitted who we are not able to observe because a resident was discharged, resulting in a net change of zero.

To capture cumulative number of cases over a consistent period, we aggregated weekly reported confirmed COVID-19 cases during the study period (May 25–August 16). We then divided our estimated number of cumulative COVID-19 cases by the total estimated number of residents (as described previously) and multiplied by 1000 (see equation 2). We used the same method to estimate number of COVID-19 deaths per 1000 residents.

| (2) |

As our proposed measure uses a different numerator than the CMS measure, we created an additional statistic using the numerator from equation 2 divided by the denominator in equation 1 and multiplied by 1000 for a more appropriate comparison.

Assessing Utility of Metrics

Finally, to assess the utility of the CMS measure and our proposed measures, we examined differential associations of star ratings on the number of cases/deaths. We used negative binomial regression with constant dispersion adjusted for county-level cases per capita for the study period, state, ownership type, adjusted total nurse staffing hours per resident per day, and nursing home rating group.

Results

Replication

We confirmed the CMS statistics of “total resident confirmed COVID-19 cases per 1000 residents” and “total resident COVID-19 deaths per 1000 residents” are derived using the total number of occupied beds in a given week. As the total number of occupied beds per week is not subject to quality assurance checks, per CMS documentation, facilities could pass quality assurance checks yet have inaccurate estimated “total cases (deaths) per 1000 residents.” Using a facility-specific CV to standardize variation in reported number of total occupied beds during all reporting periods, we compared relative variances across facilities. The mean CV is 0.058 (SD 0.096, range 0–3.46), meaning that some facilities reported dramatic variations in number of occupied beds over time. The CV is one method to identify extreme outliers that may reflect data entry errors; see example in Supplementary Table 2.

Proposed and Alternative Statistics in the Analytic Sample

Using our proposed measure of cases per 1000 estimated residents (equation 2), we found the average number of cases was 43.8 (SD 97.3, range 0–1342.1) with 5929 (53.3%) facilities having zero confirmed cases. Using the CMS approach of total occupied beds in a given week as proxy for number of residents (numerator from equation 2 and denominator from equation 1), we found the average number of cases per 1000 occupied beds was 66.8 (SD 152.6, Range 0–1789.5). In contrast, the average CMS reported “total resident confirmed COVID-19 cases per 1000 residents” was 128.6 (SD 237.0, Range 0–2840). As all measures have maximum values exceeding 1000, this underscores all the proposed measures are undercounts.

Comparison of Measures in the Analytic Sample

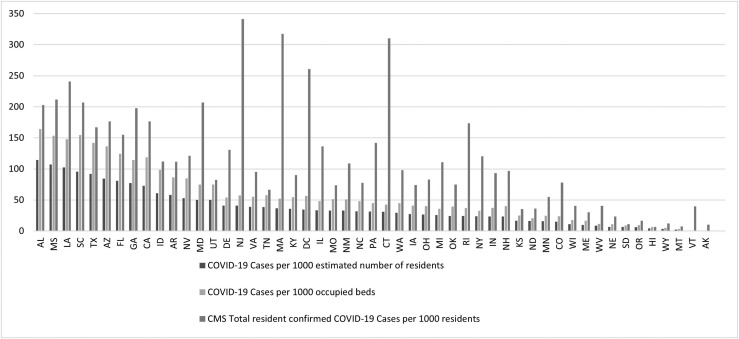

We then compared the 3 derived statistics for the reporting period ending August 16, 2020: (1) the CMS reported “total resident confirmed COVID-19 cases per 1000 residents”; (2) the proposed statistic (cases per 1000 estimated residents in equation 2); and (3) the alternative statistic (cases 05/25–08/16 per 1000 total occupied beds).” Modeled after the figure on the CMS Web site (https://data.cms.gov/stories/s/COVID-19-Nursing-Home-Data/bkwz-xpvg/), Figure 1 presents the mean number of cases by state for each metric.

Fig. 1.

Average cases per 1000 residents by state. Notes: Mean number of cases per 1000 residents by state are reported. The number of cases per 1000 estimated residents was derived by the authors by calculating the total number of cases reported by a facility between May 31, 2020, and August 16, 2020, divided by the estimated number of residents cared for between May 31, 2020, and August 16, 2020 times 1000. The cases per 1000 occupied beds was derived by the authors by calculating the total number of cases reported by a facility between May 31, 2020, and August 16, 2020 divided by the total number of occupied beds in the reporting period ending August 16, 2020, times 1000. Finally, CMS total resident confirmed COVID-19 cases per 1000 residents is the value as reported in the CMS Nursing Home COVID-19 dataset for reporting period August 16, 2020.

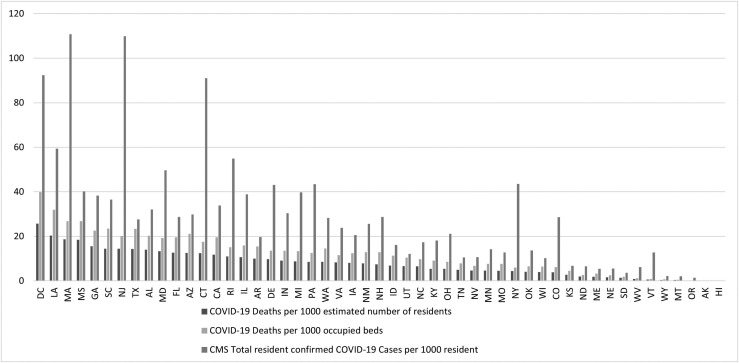

Despite our conservative estimated number of residents, we find number of cases per 1000 estimated residents by state is substantially lower, on average, than the metrics using total number of occupied beds in a week as proxy for number of residents. When applying the same methodology to estimate number of deaths per 1000 residents, we find similar results (Figure 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Average deaths per 1000 residents by state. Notes: Mean number of deaths per 1000 residents by state are reported. Deaths per 1000 estimated residents was derived by the authors by calculating the total number of deaths reported by a facility between May 31, 2020, and August 16, 2020, divided by the estimated number of residents cared for between May 31, 2020, and August 16, 2020 times 1000. The deaths per 1000 occupied beds was derived by the authors by calculating the total number of deaths reported by a facility between May 31, 2020, and August 16, 2020, divided by the total number of occupied beds in the reporting period ending August 16, 2020, times 1000. CMS total resident COVID-19 deaths per 1000 residents is the value as reported in the CMS Nursing Home COVID-19 dataset for the reporting period August 16, 2020.

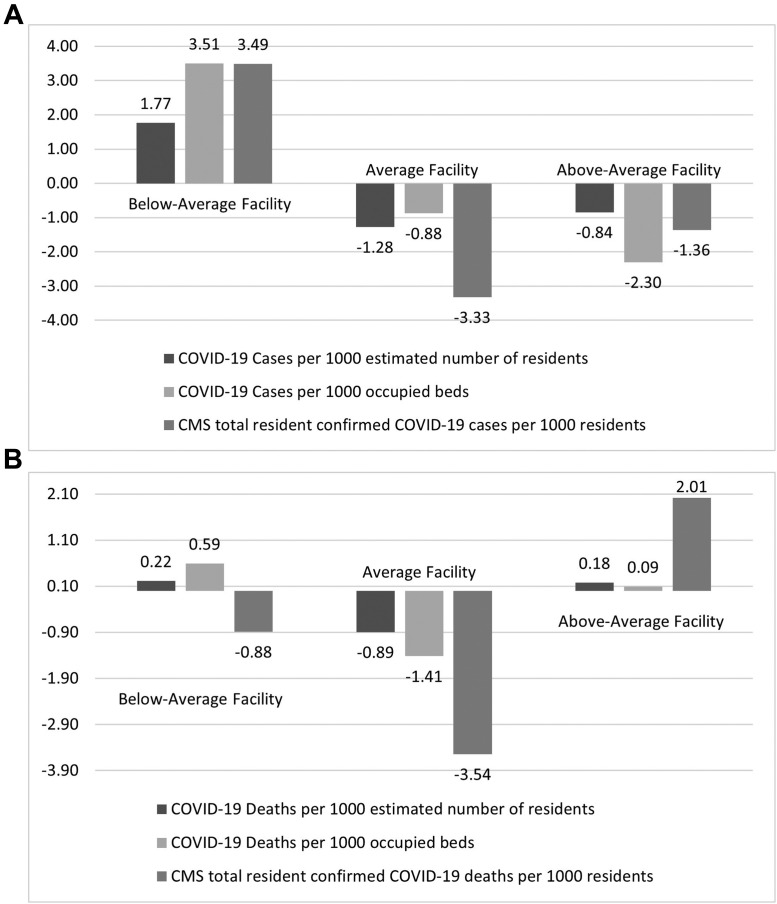

Finally, Figure 3 illustrates the residuals of number of cases/deaths per 1000 residents for each metric. Below-average rated facilities have 3.5 more COVID-19 cases per 1000 than expected using the CMS measure, but only 1.8 more COVID-19 cases per 1000 residents using our proposed measure. When examining the differential associations of star ratings, across all metrics, compared with below-average rated facilities, above-average rated facilities had statistically significantly fewer cases/deaths (P < .05), whereas average rated facilities were not significantly different (model output in Supplementary Table 3).

Fig. 3.

(A) Mean residual cases per 1000 residents by facility rating between May 31, 2020, and August 16, 2020. (B) Mean residual deaths per 1000 residents by facility rating between May 31, 2020, and August 16, 2020. Notes: Below-average facilities are those designated as a Special Focus Facility, that is, no rating, or those receiving a 1- or 2-star rating. Average facilities are those with a 3-star rating. Above-average facility had a 4- or 5-star rating. Mean of the residuals reported from negative binomial regression controlling for cases per capita per county, facility rating, facility ownership, state, and adjusted nurse staffing hours per resident per day.

Discussion

We replicated the CMS-derived measures by dividing the total reported cases over the duration of CMS reporting by the number of occupied beds at a single point in time. Although the numerator is a cumulative count of cases/deaths for differing time periods by facility, the denominator is a snapshot of occupied beds per reporting period (ie, on a particular day in a given week). As demonstrated in Figure 1, the CMS-provided metric indicates differing trends across states compared with the 2 other measures. Even when aligning reporting periods for the numerator and denominator, using the occupied beds in a facility for a given week as proxy for the number of residents results in inflated estimates of cases/deaths per 1000 residents. Although our measure is mechanically lower than the CMS measure, as we exclude cases/deaths reported before May 25, it is critical to have a statistic to compare facilities, especially if informing future resource allocation.

Unlike prior years when researchers could estimate current resident counts using prior facility censuses, these methods may not be appropriate during the COVID-19 pandemic, as multiple forces influence a facility's census, with some forces suggesting an increase in census and others a decrease. To date, the dominating force is ambiguous. For example, experts initially projected insufficient capacity of skilled nursing facility beds during the pandemic with estimates up to 30% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 requiring short-term rehabilitative care in a nursing facility.5, 6, 7 As of June 20, 2020, CMS estimated 23% of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with COVID were discharged to skilled nursing facilities.8 These estimates suggest an expected increase in nursing facility census. Yet simultaneously, the reduction in elective procedures in hospitals and the increased rates of discharge of patients from nursing facilities suggests an expected reduction in occupancy in nursing facilities.9 Researchers found decreased census in sample of skilled nursing facilities from Cleveland, Detroit, and New York in March to May 2020 compared with 2019.10 Thus, a weekly census may be lower compared with prior years, but conditional on length of stay and demand for beds (ie, local transmission rates), the cumulative number of patients at a nursing facility may be higher compared with past years due to greater turnover among residents.

Conclusions and Implications

Our results illustrate the importance of having accurate data during the pandemic, as aligned with recommendations from the Coronavirus Commission on Safety and Quality in Nursing Homes.2 Estimating the number of residents has meaningful implications when considering policies to penalize nursing homes with worse outcomes. When predicting number of cases/deaths, we found no statistically significant differences between average and below-average rated facilities, but significantly fewer cases/deaths in facilities rated above average compared with those rated below average. Multiple rigorous studies found no relationship between overall star rating and nursing home outcomes.11, 12, 13 Although we consistently found lower-rated facilities had more cases, we did not control for time-varying state policies (eg, some states such as Massachusetts designated facilities must receive patients with COVID-19, but this policy was rescinded). The analysis is subject to additional limitations. We excluded facilities based on quality control, weekly submissions, and on CV, which may limit generalizability.

To develop evidence-based strategies to mitigate future COVID-19 outbreaks and reduce mortality in nursing facilities, the metrics matter. Future research should directly estimate the number of residents served in nursing facilities in 2020 while controlling for selection biases to evaluate the effectiveness of policies. Yet identifying appropriate metrics for facility-level comparisons is time-sensitive and critical to protecting nursing home residents as the pandemic and vaccination efforts continue. Our proposed metric uses publicly available data to quantify COVID-19 burden more accurately in nursing facilities.

Footnotes

This research did not receive any funding from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Dr. Van Houtven and Ms. Miller are supported by the Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation at the Durham VA Health Care System (Grant No. CIN 13–410). Dr. Gorges was supported by the National Institute on Aging, United States under Grant Award Number T32 AG000243.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Table 1.

Method to Estimate Facility Census for Example Facility

| Reporting Period∗ | Number of Occupied Beds | Weekly COVID-19 Admissions | Weekly All Deaths | Initial Census | Prior Week Census | Non–COVID-19 Admissions | Weekly New Admissions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period t>0 | A | B | C | D | E = A[_n-1] | F = A – E – B + C | B + F |

| Example Facility A | |||||||

| 5/31/2020 | 40 | 2 | 1 | 40 | . | . | . |

| 6/7/2020 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 40 | −2 | −2 |

| 6/14/2020 | 41 | 2 | 0 | 40 | 38 | 1 | 3 |

| 6/21/2020 | 39 | 1 | 5 | 40 | 41 | 2 | 3 |

| 6/28/2020 | 38 | 0 | 3 | 40 | 39 | 2 | 2 |

| 7/5/2020 | 40 | 2 | 2 | 40 | 38 | 2 | 4 |

| 7/12/2020 | 41 | 3 | 2 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 3 |

The decimal places indicate missing data.

Total number of estimated residents = initial census [D] + sum of weekly new admissions greater than zero.

➢ Initial census = 40.

➢ Sum of weekly new admissions where value is greater than 0: 3 + 3 + 2 + 4 + 3 = 15.

➢ Total number of estimated residents = 40 + 15 = 55.

Reporting period pertains to the week ending in that date.

Supplementary Table 2.

Example Facility

| Reporting Period | Number of Occupied Beds | Cumulative COVID-19 Cases | CMS Reported Total Number of Cases per 1000 Residents | Cumulative COVID-19 Deaths | CMS Reported Total Number of Deaths per 1000 Residents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5/31/2020 | 36 | 6 | 166.7 | 1 | 27.8 |

| 6/7/2020 | 2 | 6 | 3000 | 1 | 500 |

| 6/14/2020 | 38 | 6 | 157.9 | 1 | 26.3 |

| 6/21/2020 | 38 | 6 | 157.9 | 1 | 26.3 |

| 6/28/2020 | 38 | 6 | 157.9 | 1 | 26.3 |

| 7/5/2020 | 38 | 7 | 184.2 | 1 | 26.3 |

| 7/12/2020 | 38 | 7 | 184.2 | 1 | 26.3 |

Supplementary Table 3.

Model Output

Supplementary Table 3A includes the model coefficients from the negative binomial model with constant dispersion when modeling the number of cases per 1000 residents using the 3 different measures.

| COVID-19 Cases per 1000 Estimated Number of Residents | COVID-19 Cases per 1000 Occupied Beds | CMS Total Resident Confirmed COVID-19 Cases per 1000 Residents | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Star rating | |||

| Below average (Special focus facility, 1 star or 2 stars) | ref | ref | ref |

| Average (3 stars) | −0.0590 | −0.0601 | −0.0525 |

| (0.0385) | (0.0386) | (0.0359) | |

| Above average (4 or 5 stars) | −0.211∗∗∗ | −0.217∗∗∗ | −0.193∗∗∗ |

| (0.0328) | (0.0329) | (0.0304) | |

| Cases per capita per county | 0.000331∗∗∗ | 0.000331∗∗∗ | 0.000385∗∗∗ |

| (0.0000168) | (0.0000168) | (0.0000147) | |

| Adjusted total nurse staffing hours per resident per day | −0.138∗∗∗ | −0.139∗∗∗ | −0.0915∗∗∗ |

| (0.0226) | (0.0226) | (0.0204) | |

| Facility ownership type | |||

| For-profit | ref | ref | ref |

| Government | −0.211∗∗ | −0.210∗∗ | −0.259∗∗∗ |

| (0.0688) | (0.0689) | (0.0645) | |

| Non-profit | −0.102∗∗ | −0.101∗∗ | −0.0908∗∗ |

| (0.0382) | (0.0383) | (0.0349) | |

| lndelta | 5.703∗∗∗ | 6.201∗∗∗ | 6.639∗∗∗ |

| (0.0299) | (0.0306) | (0.0279) |

All models also included state fixed effects.

Standard errors in parentheses

∗P < .05.

∗∗P < .01.

∗∗∗P < .001.

Supplementary Table 3B includes the model coefficients from the negative binomial model with constant dispersion when modeling the number of deaths per 1000 residents using the 3 different measures.

| COVID-19 Deaths per 1000 Estimated Number of Residents | COVID-19 Deaths per 1000 Occupied Beds | CMS Total Resident COVID-19 Deaths per 1000 Residents | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Star rating | |||

| Below average (Special focus facility, 1 star or 2 stars) | ref | ref | ref |

| Average (3 stars) | −0.0410 | −0.0415 | −0.0470 |

| (0.0511) | (0.0512) | (0.0456) | |

| Above average (4 or 5 stars) | −0.317∗∗∗ | −0.322∗∗∗ | −0.253∗∗∗ |

| (0.0449) | (0.0450) | (0.0394) | |

| Cases per capita per county | 0.000447∗∗∗ | 0.000447∗∗∗ | 0.000530∗∗∗ |

| (0.0000227) | (0.0000227) | (0.0000193) | |

| Adjusted total nurse staffing hours per resident per day | −0.156∗∗∗ | −0.157∗∗∗ | −0.113∗∗∗ |

| (0.0316) | (0.0316) | (0.0268) | |

| Facility ownership type | |||

| For-profit | ref | ref | ref |

| Government | −0.210∗ | −0.211∗ | −0.264∗∗ |

| (0.0977) | (0.0978) | (0.0873) | |

| Non-profit | −0.0136 | −0.0125 | −0.0493 |

| (0.0519) | (0.0520) | (0.0450) | |

| lndelta | 4.796∗∗∗ | 5.334∗∗∗ | 5.814∗∗∗ |

| (0.0413) | (0.0427) | (0.0367) |

Notes: All models also included state fixed effects.

Standard errors in parentheses.

∗P < .05.

∗∗P < .01.

∗∗∗P < .001.

References

- 1.Girvan G., Roy A. 2020. Nursing Homes & Assisted Living Facilities Account for 42% of COVID-19 Deaths. FREOPP.https://freopp.org/nursing-home-deaths-from-covid-19-u-s-historical-data-b4ad44cfc48e Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Girvan G., Roy A. Nursing Homes & Assisted Living Facilities Account for 42% of COVID-19 Deaths. The Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity. 2020. https://freopp.org/the-covid-19-nursing-home-crisisby-the-numbers-3a47433c3f70

- 3.Trump Administration Unveils Enhanced Enforcement Actions Based on Nursing Home COVID-19 Data and Inspection Results. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. June 1, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/trump-administration-unveils-enhanced-enforcement-actions-based-nursing-home-covid-19-data-and Available at:

- 4.Chidambaram P., Garfield R. June 15, 2020. Limits and Opportunities of Federal Reporting on COVID-19 in Nursing Facilities. The Kaiser Family Foundation.https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/limits-and-opportunities-of-federal-reporting-on-covid-19-in-nursing-facilities/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arora V.S., Fried J.E. How will we care for coronavirus patients after they leave the hospital? By building postacute care surge capacity. Health Affairs Blog. April 13, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200408.641535/full/ Available at:

- 6.Grabowski D.C., Joynt Maddox K.E. Postacute care preparedness for COVID-19: Thinking ahead. JAMA. 2020;323:2007–2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CarePort Preparing for what comes next: Where will COVID-19 patients recover? An analysis of 23K nursing home residents in New York and COVID-19 survey results from 8,942 nursing homes across the United States. https://careporthealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/COVID-19-Report-2-Nursing-Home-Final.pdf Available at:

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Preliminary Medicare COVID-19 data snapshot Medicare claims and encounter data: Services 1 to August 15, 2020, Received by September 11, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/medicare-covid-19-data-snapshot-fact-sheet.pdf Available at:

- 9.Silver-Greenberg J., Harris A.J. They just dumped him like trash. Nursing homes evict vulnerable residents. The New York Times. 2020 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/21/business/nursing-homes-evictions-discharges-coronavirus.html Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnett M.L., Hu L., Martin T., Grabowski D.C. Mortality, admissions, and patient census at SNFs in 3 US cities during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324:507–509. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorges R.J., Konetzka R.T. Staffing levels and COVID-19 cases and outbreaks in US nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:2462–2466. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abrams H.R., Loomer L., Gandhi A., Grabowski D.C. Characteristics of U.S. nursing homes with COVID-19 cases. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1653–1656. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White E.M., Kosar C.M., Feifer R.A. Variation in SARS-CoV-2 prevalence in U.S. skilled nursing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:2167–2173. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]