ABSTRACT

We present an 18-month-old girl with strabismus and a variable esotropia of the left eye. Fixation of the affected eye was intermittent with a relative afferent pupillary defect. A fundus photography of the left eye displayed a combination of features of both morning glory disc anomaly and peripapillary staphyloma. A B-scan ultrasonography examination of the left eye showed a conical excavation of the posterior pole. Cycloplegic refraction measurements showed a large amount of anisometropia. Correction with glasses and part-time occlusion was prescribed and a strict follow-up routine was advised. No other systemic associations with the disease have been discovered so far in our patient. We support the theory that morning glory disc anomaly and peripapillary staphyloma may represent two different morphologies in the spectrum of the same disease.

KEYWORDS: Morning glory disc anomaly, contractile staphyloma, esotropia, amblyopia

Introduction

Excavated optic disc anomalies include optic disc coloboma, morning glory disc anomaly (MGDA), peripapillary staphyloma, megalopapilla, optic pit, and the optic disc anomalies associated with periventricular leukomalacia and papillorenal syndrome.1 In MGDA and peripapillary staphyloma an excavation of the posterior globe surrounds and incorporates the optic disc. In the other conditions, the excavation is contained within the optic disc.2

MGDA is a congenital malformation of the optic nerve characterised by a funnel-shaped excavation of the posterior globe that incorporates the optic disc.3 The disc is markedly enlarged with neuroglial remnants in its centre surrounded by chorioretinal pigmentary disturbances.4 The blood vessels appear increased in number and arise from the periphery of the disc. They abandon the papilla in a radial fashion to continue in a straight course. It is often difficult to distinguish arterioles from venules.5 Kindler integrated the morphological characteristics of the anomaly into a syndrome, which he named after the morning glory flower due to its resemblance to the optic papilla in this condition.6 There is a female gender predisposition and a prevalence of 2.6/100,000.2,7 The pathogenesis is unknown. It usually presents as a non-heritable unilateral malformation.8 A hypothesis is that the anomaly is due to poor development of the lamina cribrosa and the posterior sclera. Mutations in the PAX 6 gene have recently been identified in these patients.9 The condition may present with nystagmus, strabismus, or amblyopia. The visual acuity can vary, but is usually very poor with only about 30% of patients having a visual acuity of 20/40 or better.8 Generally, it is an isolated ocular abnormality. However, some systemic associations have been reported, the most common of which are transsphenoidal basal encephalocele and midfacial malformations. Facial abnormalities include hypertelorism, cleft lip and cleft palate. Because the hypothalamus can be contained within the encephalocele, hypopituitarism can occur, affecting growth hormone and antidiuretic hormone production. Patients with MGDA should have a complete general physical examination and growth evaluation.10

Peripapillary staphyloma is a rare non-hereditary congenital optic disc anomaly in which a deep fundus excavation surrounds a relatively normal-appearing optic nerve head.11 Its exact pathophysiology is unknown. However, the clinical features of peripapillary staphyloma are thought to be most consistent with diminished peripapillary structural support, resulting from incomplete differentiation of the posterior sclera from neural crest cells in the fifth month of gestation.12 There is no central glial tuft overlying the disc and the retinal vascular pattern is normal. The staphylomatous excavation is deeper than that in the MGDA. Several cases of contractile peripapillary staphyloma have been documented,13,14 sometimes with transient visual obscurations. It is caused by one of two possible mechanisms, “pressure balance” or “muscular contraction.”15 It is generally unilateral and is accompanied by poor vision, although a bilateral case with normal visual acuity has been reported.16 Unlike other excavated optic disc anomalies, peripapillary staphyloma is known to be rarely associated with other congenital defects or systemic diseases.11

Case report

An 18-month-old girl was examined in the outpatient clinic in Stara Zagora, Bulgaria due to strabismus. She was born at term with a birth weight of 3150 g. The mother had undergone normal pregnancy and delivery without any complications. There were no facial anomalies pointing to a genetic disease. The child had undergone normal development so far. There was no family history of ocular disease, except for a cousin with strabismus. According to the grandmother the child hadhad strabismus since birth. Due to the young age of the child the visual acuity could not be formally recorded. The left eye had an esotropia, which was intermittent and variable measuring 10–15 prism dioptres. When the left eye was covered the child tried to look behind the hand and was bothered. Fixation of the right eye was centred and steady while that of the left was intermittent. No changes were discovered on biomicroscopy of both eyes. Pupillary reflex testing showed a relative afferent pupillary defect in the left eye. The interpupillary distance was 51 mm.

On indirect ophthalmoscopy an enlarged optic disc in the left eye was discovered surrounded by an annulus of chorioretinal pigmentary disposition. The base of the excavation could not be seen clearly due to its depth. There was some straightening of the retinal vessels arising from the disc margin and no foveal reflex. The macula of the other eye seemed well formed with a pink optic disc, normal in size, with normal appearing cup and sharp disc margins.

After the initial examination, the fundi of the patient were photographed with a RetCam (Figures 1 and 2). Fundus photography of the left eye (Figure 1) displayed a combination of features which made the diagnosis difficult. The optic disc did not look normal, as it should be in a case of peripapillary staphyloma. However, it did not look exactly like the MGDA due to the very deep excavation of the peripapillary sclera, surrounded by mottled pigment epithelium, which is typical for peripapillary staphyloma. A pigmentary ring around the optic disc, characteristic for MGDA was observed, but only partially visible due to the depth of the surrounding excavation. Even though the centre of the excavation of the disc was quite unclear, gliosis was still observed, which further supported this diagnosis. The features of the blood vessels and the size of the disc, also corresponded with MGDA. After some consideration, a diagnosis of peripapillary staphyloma coexisting with MGDA was made.

Figure 1.

RetCam fundal photograph of the left eye demonstrating an enlarged papilla with an annulus of chorioretinal pigmentary disposition, blood vessels abandoning the papilla in a radial fashion to continue in a straight course, gliosis in the centre and deep peripapillary excavation with surrounding mottled pigment epithelium

Figure 2.

RetCam fundal photograph of the right eye demonstrating a normal fundus

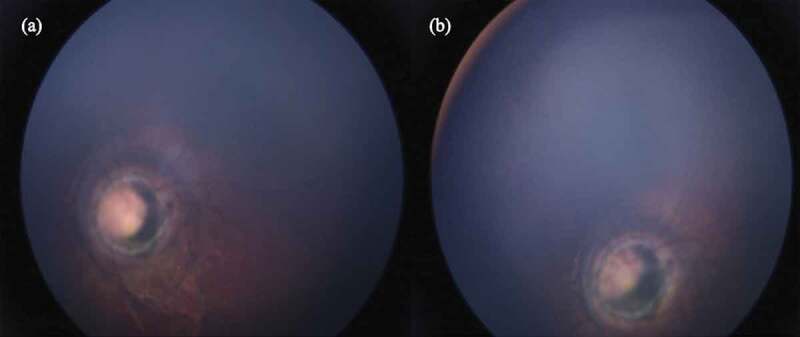

The other thing that made an impression on us was that the visible part of the disc and the pigmented ring changed, as seen in different photographs (Figure 3). We attributed this phenomenon to the contractility of the peripapillary staphyloma.

Figure 3.

Changes in the visible part of the left optic disc. (a) Relaxed phase. (b) Contractile phase

B-scan ultrasonography of the left eye showed a conical excavation of the posterior pole (Figure 4). The vitreous and retina were intact.

Figure 4.

Ultrasonography of the left eye demonstrating a conical excavation of the posterior pole (arrowed)

Cycloplegic refraction measurements showed a large amount of anisometropia (+1.00/-1.50x175 and -5.75/-0.5x5 for the right and left eyes respectively). The refractive error was corrected with glasses, and part-time occlusion of the right eye was prescribed. When assessed a month later the parents reported that the prescribed regimen was well tolerated.

She was referred to a paediatrician, ear, nose and throat specialist, and neurologist for further assessment. No other systemic associations with the disease have been discovered so far in her.

Discussion

In addition to the classic descriptions of peripapillary staphyloma and MGDA intermediate forms have been observed by other authors as well.17–19 Kumar et al. supported the theory that these two excavated disc anomalies represent two different morphologies in the spectrum of the same disease.18 A case series of patients with frontonasal dysplasia and basal encephaocele reported by Hodgkins et al. revealed that all patients had either peripapillary staphyloma or MGDA abnormalities. The authors suggested that these disc abnormalities have similar embryological origins.20 The case we reported is another example that there might be a connection between the two structural anomalies of the optic disc considered unrelated by most authors.

The MGDA is more commonly associated with systemic conditions than peripapillary staphyloma. But when we are dealing with an intermediate case, like the one we described here, in our opinion, the patient should still receive a full systemic work-up. The same may be considered for patients with peripapillary staphyloma due to the uncertainty in the spectrum of the condition.

One of the most common associations with MGDA, basal encephalocele, frequently escapes diagnosis and may not be detected until adulthood.10 There may be hypertelorism, expansion of the epipharynx and hypothalamohypophysial dysfunction, mainly growth hormone deficiency.21 Magnetic resonance imaging is the imaging modality of choice in investigating possible basal encephaloceles.22

Organic amblyopia in patients with severe optic nerve dysfunction due to a structural abnormality is often superimposed by a degree of functional amblyopia. Although standard visual acuity cannot be restored in patients with both types of amblyopia, occlusive therapy still plays an important role in the visual rehabilitation. Evidence has shown that prescription of refractive correction along with occlusion therapy can improve vision.23 According to Cavazos et al. every patient with an anatomical malformation diagnosed during the period of sensory maturation should be treated with occlusive therapy.4 With that in mind, we have some hope for improvement of the visual acuity of our patient, but our expectations are guarded. The patient should adhere to a strict follow-up routine due to the risk of inducing amblyopia in the normal eye.

Patients with MGDA should also be carefully examined in order to recognise and treat on time the eventual occurrence of serous retinal detachment. This complication is observed in 30% of cases of MGDA.24 Retinal detachment has also been observed in patients with peripapillary staphyloma.25 While there are some cases of spontaneous resolution, most require immediate treatment.26,27

Conclusion

We support the theory that peripapillary staphyloma and MGDA may represent two different morphologies in the spectrum of the same disease. Excavated optic disc abnormalities are rare conditions, but they must be suspected in children referred for nystagmus, strabismus, or amblyopia. Early treatment of superimposed functional amblyopia can improve visual acuity. Regular follow-up is also recommended, to allow the early treatment of complications such as retinal detachment, as well as the timely diagnosis of associated general health problems.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Brodsky M. Congenital optic disk anomalies. Surv Ophthalmol. 1994;39(2):89–112. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(94)90155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller NR, Walsh FB, Hoyt WF, eds. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Vol. 1. 2005:59. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quah BL, Hamilton J, Blaser S, Héon E, Tehrani NN.. Morning glory disc anomaly, midline cranial defects and abnormal carotid circulation: an association worth looking for. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35(5):525–528. doi: 10.1007/s00247-004-1345-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavazos-Adame H, Olvera-Barrios A, Martinez-Lopez-Portillo A, Mohamed-Hamsho J. Morning glory disc anomaly, a report of a successfully treated case of functional amblyopia. J Clin Diagn Res. October 9, 2015;10:ND01–ND03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.BJ L, EI T. Update on the morning glory disc anomaly. Ophthalmic Genet. 2008. June;29(2):47–52. doi: 10.1080/13816810801901876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kindler P. Morning glory syndrome: unusual congenital optic disk anomaly. Am J Ophthtalmol. 1970;69(3):376–384. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(70)92269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ceynowa DJ, Wickström R, Olsson M, et al. Morning glory disc anomaly in childhood - a population-based study. Acta Ophthalmol. November 2015;93(7):626–634. doi: 10.1111/aos.12778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harasymowycz P, Chevrette L, Décarie JC, et al. Morning glory syndrome: clinical, computerized tomographic, and ultrasonographic findings. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2005;42(5):290–295. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-20050901-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azuma N, Yamaguchi Y, Handa H, et al. Mutations of the PAX6 gene detected in patients with a variety of optic-nerve malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2003. June;72(6):1565–1570. doi: 10.1086/375555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eustis HS, Sanders MR, Zimmerman T. Morning glory `syndrome in children. Association with endocrine and central nervous system anomalies. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994. February;112(2):204–207. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090140080027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blair MP, Blair NP, Rheinstrom SD, Jednock NJ. A case of peripapillary staphyloma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1138–1139. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.8.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollock S. The morning glory disc anomaly: contractile movement, classification, and embryogenesis. Doc Ophthalmol. 1987;65:439–460. doi: 10.1007/BF00143047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farah ME, Uno F, Bonomo PP, Nóbrega M, Höfling-Lima AL. Contractile peripapillary staphyloma with light stimulus to the contralateral eye. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(8):1216–1217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michel E, Farah MD, Fausto Uno MD, et al. Contractile peripapillary staphyloma with light stimulus to the contralateral eye. Ophthalmol. 2001;119(8):1216–1217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kral K, Svarc D. Contractile peripapillary staphyloma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;71(5):1090–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caldwell JB, Sears ML, Gilman M. Bilateral peripapillary staphyloma with normal vision. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;71:423–425. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(71)90421-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giuffré G, Distefano MG. Peripapillary staphyloma and asymmetric morning glory anomaly. Neuroophthalmol. 2006;Vuori ML. Morning glory disc anomaly with pulsating peripapillary staphyloma. A case history. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1987;65:602–6. doi: 10.1080/01658100600651823. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar V, Surve A, Chandra P, Kumar A. Morning glory anomaly with peripapillary staphyloma. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016216729. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-216729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Risma J, Morning glory disc anomaly with peripapillary staphyloma. www.eyeround.org

- 20.Hodgkins P, Lees M, Lawson J, et al. Optic disc anomalies and frontonasal dysplasia. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:290–293. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.3.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minotto I, Abdala N, Miachon AA, et al. Basal encephalocele associated with morning glory syndrome: case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. December 2007;65(4A):988–991. doi: 10.1590/S0004-282X2007000600013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokoda A, Matsukado Y, Fuwa I, Moroki K, Nagahiro S. Anterior basal encephalocele of neonatal and infantile period. Neurosurgery. 1986;19:468–478. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198609000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lengyel D, Klainguti G, Mojon DS. Does amblyopia therapy make sense in eyes with severe organic defects?. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 2004;221(5):386–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trabouisi E. Morning glory disc anomaly or optic disc coloboma. Arch Ophthtalmol. 1994;112(2):153.doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090140027003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim SH, Choi MY, Yu YS, Huh JW. Peripapillary staphyloma: clinical features and visual outcome in 19 cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(10):1371–1376. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.10.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choudhry N, Ramasubramanian A, Shields CL, Brown G, Shields JA. Spontaneous resolution of retinal detachment in morning glory disk anomaly. J Aapos. 2009. October;13(5):499–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho CL, Wei LC. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in morning glory syndrome pathogenesis and treatment. Int Ophthalmol. 2002;24:21–24. doi: 10.1023/A:1014498717741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]