Abstract

Introduction

Prenatal anxiety and depression are major health problems all over the world. The negative sequela of prenatal comorbid anxiety and depression (CAD) has been suggested to be higher than that of anxiety or depression alone. CAD increases the odds of preterm birth, low birth weight, prolonged labor, operative deliveries, postpartum psychiatric disorders and long term cognitive impairment for the newborn. Despite its significant ill consequences, there is a dearth of studies in low-and middle-income countries. So far, to the best of our knowledge, no study assessed the prevalence of CAD in Ethiopia. Hence, the purpose of this study was to assess CAD and associated factors among pregnant women in Arba Minch Zuria district, Gamo zone, southern Ethiopia.

Methods

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 676 pregnant women from January 01 to November 30, 2019. Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scales were used to assess depression and anxiety respectively. The data were collected electronically using an open data kit (ODK) collect android application and analyzed using Stata version 15.0. Bivariate and multivariable analyses were carried out to identify factors associated with CAD using binary logistic regression. Statistical significance was set at p-value < 0.05.

Results

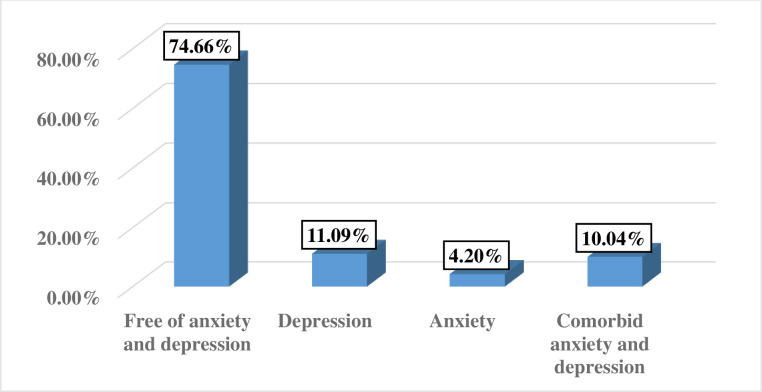

A total of 667 women were involved. The prevalence of CAD was 10.04% [95% confidence interval (CI): 7.76, 12.33]. Being married [adjusted odds ratio (AOR): 0.16, 95% CI: 0.05, 0.56], categorized in the highest wealth quintile [AOR: 2.83, 95% CI: 1.17, 6.84], having medical illness [AOR: 3.56, 95% CI: 1.68, 7.54], encountering pregnancy danger signs [AOR: 2.66, 95% CI: 1.06, 6.67], experiencing life-threatening events [AOR: 2.11, 95% CI: 1.15, 3.92] and household food insecurity [AOR: 3.51, 95% CI: 1.85, 6.64] were significantly associated with CAD.

Conclusions

In general, one in every ten women faced CAD in the study area. Nutritional interventions, early identification and treatment of pregnancy-related illness and medical ailments, prenatal mental health problems screening and interventions are imperative to minimize the risk of CAD in pregnant women.

Introduction

Globally, ~10% of pregnant women suffer from a mental disorder, primarily depression; this figure is higher (16%) in underdeveloped nations [1]. Depression and anxiety are common mental disorders in pregnant women and commonly co-occurred [2]. Findings from a systematic review comprising twenty-three studies suggested that common mental disorders (CMDs) during pregnancy are ranged from 1–37%; antenatal depression and anxiety alone are ranged from 1–30% and 1–26% respectively [3]. A meta-analysis conducted by Falah and coworkers after including 66 studies from 30 countries (i.e. most of the studies were from high-income countries) reported that comorbid anxiety and depression (CAD) is prevalent and seeks medical attention; 9.5% of pregnant women had self-reported co-morbid anxiety and mild to severe depressive symptoms [4]. Thiagayson and associates also reported that 5% of Singaporean women had prenatal CAD [5]. Likewise, studies from Spain, Turkey and Pakistan also demonstrated that 9.5%, 47.6% and 13.5% of pregnant women encountered CAD respectively [6, 7].

Though the co-morbidity of anxiety and depression was not addressed, a systematic review in Africa showed that the mean prevalence of antenatal depression and anxiety were 11.3% and 14.8% respectively [8]. A study from urban South Africa demonstrated that 7.6% and 9.7% of pregnant women experience CAD in early and late pregnancy respectively [9]. In Ethiopia, neither the status of CAD nor anxiety is reported but a systematic review carried out by Getinet and colleagues reported that the pooled estimate of antenatal depression is 23.6% [10].

Previously published evidences consistently reported that low socioeconomic status, adverse events in life, poor social support, intimate partner violence (IPV), previous episode of CMDs, history of chronic medical illness, unmarried status and unplanned pregnancy increases the odds of perinatal mental disorders [2, 3, 11, 12]. Also, Premji and associates reported that a high level of perceived stress, having ≥ 3 children and adverse childhood experience increases the odds of CAD [6]. Household food insecurity also increases the odds of mental health problems during pregnancy [13–15]. Moreover, poor emotional support is reported as one of the single most predictors for CAD symptoms in a multinational study conducted in Turkey and Spain [7].

Undiagnosed and untreated CAD during pregnancy increases the odds of perinatal adverse outcomes [16]. It has been suggested that CAD has a significant negative effect on neonates than those of anxiety or depression alone [17]. CAD in the third trimester is mainly associated with oligohydramnios, intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), diminished placental perfusion and preterm labor [18]. CAD also increases the likelihood of low birth weight (LBW), preterm birth, prolonged labor and delayed initiation of breastfeeding [19, 20]. Moreover, it results in poor infant cognitive development [21], mental health problems in late childhood [22], birth asphyxia and coronary heart disease [23]. Furthermore, prenatal mental disorders increase the number of non-scheduled antenatal care (ANC) visits, emergency health care visits [24], maternal postpartum mental health problems and infanticide [1, 25].

Though anxiety and depression are treatable, about one-third and less than half of pregnant women received appropriate treatment respectively [26]. Especially, in low and middle-income countries (including Ethiopia) maternal psychological interventions are very limited [27]. In Ethiopia, antenatal depression is ranged from 11.8% to 31.2% [28–37]. However, little emphasis has been given to prenatal anxiety and other mental health problems including CAD. So far, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that investigates the comorbidity of antenatal anxiety and depression in Ethiopia. Therefore, the purpose of the study was to assess the prevalence of CAD and associated factors among pregnant women in Arba Minch Zuria district, Gamo zone, southern Ethiopia.

Methods

Study setting, design and period

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Arba Minch Zuria district, Gamo zone, southern Ethiopia from January 01 to November 30, 2019. The district is bordered by Dirashe special woreda on the south, Bonke on the west, Dita and Chencha on the north and Oromia region on the east. Based on the 2007 census projection, the district had a total population of 164,529 in 2019; of whom 82,330 were women. Arba Minch Zuria district had a total of 31 kebeles (smallest administrative units) and it is included under Arba Minch Zuria Demographic and Health Development Program (AM-DHDP). The center was established in 2009 and became a member of INDEPTH in 2015. AM-DHDP is owned by Arba Minch University and it is one of the six public universities with Demographic and Surveillance System (HDSS) in Ethiopia [38].

Study population

All pregnant women who were living in Arba Minch Health and Demographic Surveillance Site (AM-HDSS) were the study population. Women were enrolled in the study irrespective of their age and pregnancy trimester. Those pregnant women who were unable to communicate due to serious illness and not available after three consecutive home visits were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination

The minimum sample size required for this study was determined by EpiInfo-7 StatCalc using single population proportion formula after fulfilling the following assumptions: 95% level of confidence, 5% margin of error, 26.2% proportion of mental distress in pregnant women [29]. After incorporating a design effect of 2 and a 10% non-response rate the final sample size for this study was 654. However, due to the nature of cluster sampling, all 676 pregnant women living in the selected clusters were included.

Sampling procedure

Out of 31 kebeles in Arba Minch Zuria district 9 (one small town and 8 rural Kebeles) were selected randomly and included under AM-DHDP [38]. For our study, the kebeles were considered as a cluster and all pregnant women who live in these clusters were included. Hence, the first step was identifying all pregnant women in the selected clusters. Thus, AM-HDSS and health extension worker’s pregnancy register was used to identify pregnant women. Besides, to minimize the chance of missing early pregnancies; the WHO and CDC pregnancy screening checklist was used [39]. During the study period a total of 676 pregnant women were identified from the selected clusters: 61, 41, 38, 109, 131, 66, 59, 104 and 67 from Chano Chalba, Kola Shara, Genta Meyche, Zigiti Merche, Gatse, Laka, Shelle Mella, Kolla Shelle, and Zeyse Dembele respectively.

Study variables and measurements

The data collection instrument was organized after reviewing previous literature [5, 12, 17, 24, 40]. The tool comprises socio-demographic information (age, marital status, religion, residence, educational status, occupation and husband education and occupation), socioeconomic status (assessed using locally available assets), obstetric characteristics (gravidity, parity, age at marriage, pregnancy status, ANC visit, gestational age, pregnancy danger signs), psychological problems and psychosocial relationships (social support, interpersonal relationship and experience of life-threatening events), medical illness (hypertension, diabetes, asthma, cardiac and renal disease), household food security status, substance abuse, anxiety and depression. The tool was prepared in XLSForm in excel and converted to XForms using XLSForm online converter to collect the data using Open Data Kit (ODK) tools. Then it was uploaded to the ODK aggregate server installed in AM-HDSS. ODK aggregate is a Java application that store, analyze and present XForm survey data collected using ODK Collect, which is an android application that replaces paper forms used for data collection [41].

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), originally designed by Spitzer and colleagues was used to measure antenatal depression. PHQ-9 score ranges from 0 to 27, each of the 9 items can be scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) [42]. PHQ-9 was validated in the Ethiopian context and it has good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha (α) = 0.81) and excellent intra-class correlation of 0.92 [43]. In our study, the reliability (α) coefficient of PHQ-9 was 0.87. In the current study, a score of ≥ 5 was used as a cut-off point for possible antenatal depression [24].

Anxiety was assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale; which was developed by Robert L. Spitzer (MD, professor of psychiatry) [44]. Although the GAD-7 scale was not validated in the Ethiopian context, the Spanish-language version was tested as a reliable (α = 0.89) screening tool for antenatal anxiety [45]. The reliability coefficient of the GAD-7 scale in the current study was 0.83. GAD-7 score ranges from 0 to 21, each of the items can be scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). In our study; a score of ≥ 5 was taken as the cut-off point to categorize pregnant women as having anxiety [45]. Participants who were screened positive both for anxiety and depression were categorized as having CAD [4].

Substance abuse was measured using the Fast Alcohol Screening Test (FAST) scale developed from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) by Hodgson et al., 2002. FAST has 4 items with a score ranges from 0 to 16, where a score of ≥3 indicates harmful drinking [46].

IPV was measured using 5 items Women’s Abuse Screening Test (WAST) scale; which is originally developed by Brown et al., 1996 [47]. WAST score ranges from 0–16 where a score > 1 indicates the presence of violence [48]. Social support was measured using the Oslo Social Support Scale (OSSS-3). OSSS-3, originally developed in Neverland’s, has three items and its score ranges from 3–14. It was categorized into three as “poor social support” 3–8, “moderate support” 9–11 and “strong support” 12–14 [49]. The List of Threatening Experiences (LTE) developed by Brown & Harris (1978) was used to measure life events. LTE is a self-reported questionnaire with a list of 12 threatening events that invite a dichotomous response (yes/no). The number of life events were counted for each respondent and recorded as a value from 0 to 12 [50].

Household food security was assessed using the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) developed by the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) Program of the U.S. Agency for International Development. It has 9 items with a follow-up question about the frequency of occurrence if the response is “yes” for the main questions. HFIAS score ranges from 0 to 27. In the current study, household food security status was categorized into two as “food secure” when the participants didn’t experience food access conditions in the past 4 weeks and “food insecure” when they were unable to access sufficient food at all time to lead active and healthy life [51].

Data collectors and data collection procedure

Twelve experienced individuals working in AM-HDSS were recruited for data collection. Besides, four MSc holder supervisors were recruited. Theoretical and practical training was given for the data collectors and supervisors for two consecutive days. ODK collect version 1.17.2 application was installed on the data collector’s tablet given from the center and the blank form was downloaded from the server. Then, the tool was pre-tested on 34 pregnant women in Arba Minch town two weeks before the actual data assortment. Supervisors were kept in touch with the data collectors to regularly check the data collection procedure. Finally, the data collectors sent the completed data forms weekly to the server through a wireless connection.

Data quality control

A structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was prepared in English and translated into Amharic and vice versa to ensure its consistency. Experienced ODK Experts were consulted at each step of the data collection. The training was given to data collectors and supervisors about how to collect data using ODK and briefed on each question included in the tool. Moreover, a pretest was done to ensure the clarity of the tool. Supervisors were checked on the spot and review all the questionnaires to ensure completeness of the forms. Furthermore, the investigators were kept in touch with the server workers to regularly check the sent files from each data collector.

Data management and analysis

Each data files sent from the data collector’s tablet were downloaded from the server and saved as an excel file. Finally, the data set were imported to Stata version 15.0 for cleaning, coding and analysis. Descriptive statistical analyses such as simple frequencies, mean and standard deviation were used to describe the characteristics of participants. The wealth index was constructed via Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and the family wealth was grouped into three quartiles. Bivariate analysis was used to see the association between each independent variable and CAD using binary logistic regression. To control confounding factors; variables with a p-value of ≤ 0.25 in the bivariate analysis, significant in previous studies and biological plausibility were taken for the multivariable analysis. Standard error and Hosmer-Lemeshow tests were used to check multicollinearity and the model goodness of fit respectively. Adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to identify factors associated with CAD. The level of statistical significance was set at a p-value < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was received from Arba Minch University, college of medicine and health sciences, Institutional Review Board (IRB) with an ethical clearance number of CMHS/12031653/111. Moreover, this study was conducted under the Declaration of Helsinki, and the participants were informed of the purpose of the study. Furthermore, before the commencement of the data collection written informed consent was obtained from all participants. To maintain the confidentiality of information, code numbers were used throughout the study. Pregnant women who screened positive for depression or anxiety received onsite mindfulness interventions. Also, they were linked with the health extension workers for regular psychological interventions and referral to health facilities in case of severe cases like suicidal ideation.

Results

Socio-demographic and socioeconomic characteristics

Out of 676 pregnant women involved in the current study, 9 were excluded due to incomplete information. Hence, 667 (98.7%) pregnant women were eligible for analysis. The mean (±SD) age of the participants was 27.4 (±6) years. Of the study participants, 197 (29.6%) were within the age group of 25–29 years, 360 (54%) had no formal education, 646 (96.9%) were married, 533 (79.9%) were housewives and 650 (97.4%) were rural dwellers (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants in Arba Minch Zuria district, Gamo zone, southern Ethiopia 2019, (n = 667).

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in completed years | < 20 | 52 | 7.8 |

| 20–24 | 161 | 24.1 | |

| 25–29 | 197 | 29.6 | |

| 30–34 | 161 | 24.1 | |

| ≥ 35 | 96 | 14.4 | |

| Ethnicity | Gamo | 552 | 82.8 |

| Zeyisie | 65 | 9.7 | |

| Wolayita | 42 | 6.3 | |

| aOther | 8 | 1.2 | |

| Religion | Protestant | 480 | 72.0 |

| Orthodox | 184 | 27.6 | |

| bOther | 3 | 0.4 | |

| Marital status | Single | 14 | 2.1 |

| Married | 646 | 96.9 | |

| cOther | 7 | 1.0 | |

| Mother’s education | No formal education | 360 | 54.0 |

| Primary education (1–8) | 218 | 32.7 | |

| Secondary education (9–12) | 70 | 10.5 | |

| College and above | 19 | 2.8 | |

| Husband’s education | No formal education | 304 | 45.6 |

| Primary education (1–8) | 222 | 33.3 | |

| Secondary education (9–12) | 87 | 13.0 | |

| College and above | 37 | 5.5 | |

| Missing | 17 | 2.5 | |

| Mother’s occupation | Farmer | 93 | 14.0 |

| Housewife | 533 | 79.9 | |

| Trader | 28 | 4.2 | |

| dOther | 13 | 1.9 | |

| Husband’s occupation | Farmer | 439 | 65.8 |

| Daily laborer | 118 | 17.7 | |

| Trader | 48 | 7.2 | |

| Government employ | 20 | 3.0 | |

| eOther | 25 | 3.7 | |

| Missing | 17 | 2.5 | |

| Residence | Urban | 17 | 2.5 |

| Rural | 650 | 97.5 | |

| Family size | ≤ 5 | 414 | 62.1 |

| > 5 | 253 | 37.9 | |

| Wealth quintile | Low | 221 | 33.1 |

| Medium | 225 | 33.7 | |

| High | 221 | 33.1 |

aGofa, Gurag, Oromo.

bMuslim, Yewuha miskir.

cDivorced, widowed, married but not living together.

dGovernment employ, non-governmental employer, student.

eUnemployed, driver, non-governmental employer, student, a prophet.

Obstetrics characteristics

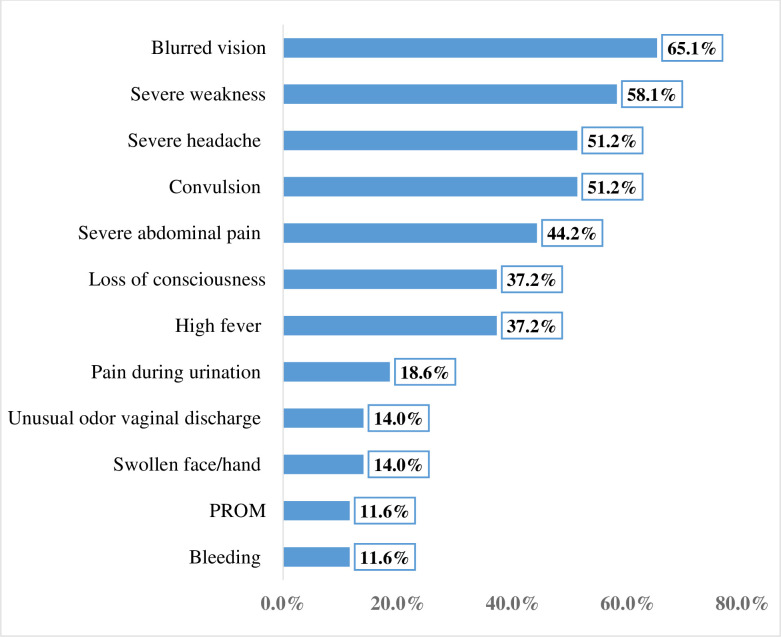

Of the participants, 315 (47.2%) got pregnant for the first time at the age of 20–24 years, 546 (81.8%) were multigravida and the current pregnancy was planned for 622 (93.3%). Among the participants, 380 (57.0%) initiated ANC and 43 (6.4%) experienced pregnancy danger signs; of them, 28 (65.1%) encountered blurred vision (Fig 1). Out of the total pregnant women enrolled in this study; 243 (36.4%) reported IPV, 176 (26.4%) experienced LTE, 51 (7.7%) had hazardous alcohol drinking habit and 186 (27.9%) were household food insecure (Table 2). Moreover, 543 (81.4%) of the participants had poor social support.

Fig 1. Experience of pregnancy danger signs among women in Arba Minch zuria district, Gamo zone, southern Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 43).

Table 2. Obstetrics characteristics of participants in Arba Minch Zuria district, Gamo zone, southern Ethiopia, 2019, (n = 667).

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first pregnancy | < 20 | 297 | 44.5 |

| 20–24 | 315 | 47.2 | |

| ≥ 25 | 55 | 8.3 | |

| Gravida | One | 121 | 18.2 |

| Two to four | 363 | 55.0 | |

| Five and above | 179 | 26.8 | |

| History of stillbirth | Yes | 26 | 3.9 |

| No | 520 | 78.0 | |

| Missing | 121 | 18.1 | |

| History of neonatal death | Yes | 72 | 10.8 |

| No | 474 | 71.1 | |

| Missing | 121 | 18.1 | |

| History of abortion | Yes | 47 | 7.0 |

| No | 499 | 74.8 | |

| Missing | 121 | 18.1 | |

| Gestational age in weeks | ≤ 12 | 46 | 6.9 |

| 13–24 | 254 | 38.1 | |

| ≥ 25 | 367 | 55.0 | |

| Reproductive intention | Planned | 622 | 93.3 |

| Unplanned | 45 | 6.7 | |

| ANC follow-up | Yes | 380 | 57.0 |

| No | 287 | 43.0 | |

| Place of ANC follow-up | Health post | 150 | 22.5 |

| Health center | 208 | 31.2 | |

| Hospital | 20 | 3.0 | |

| Private clinic | 2 | 0.3 | |

| Missing | 287 | 43.0 | |

| Number of ANC follow-up | < 4 | 259 | 38.8 |

| ≥ 4 | 121 | 18.1 | |

| Missing | 287 | 43.0 | |

| Experience of pregnancy danger signs | Yes | 43 | 6.4 |

| Medical illness | Yes | 59 | 8.9 |

| Intimate partner violence | Yes | 243 | 36.4 |

| Experience life-threatening events | Yes | 176 | 26.4 |

| Substance abuse | Yes | 51 | 7.7 |

| Household food security status | Secure | 479 | 72.1 |

| Insecure | 186 | 27.9 |

Prevalence of comorbid anxiety and depression

Overall, 10.04% [95% CI: 7.76, 12.33%] of the participants had CAD. Of the participants, 74 (11.09%) encountered depression alone (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Prevalence of common mental disorders among pregnant women in Arba Minch zuria district, Gamo zone, southern Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 667).

Factors associated with comorbid anxiety and depression

After adjustment six variables: marital status, wealth quintile, medical illness, pregnancy danger signs, experience of life-threatening events and household food insecurity were significantly associated with CAD. The likelihood of CAD were 84.0% (aOR = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.05, 0.56) lower among married women as compared to their counterparts. CAD was 2.8 times higher (aOR = 2.83, 95% CI: 1.17, 6.84) among participants in the highest wealth quintile as compared to participants in the lower quintile. Co-existing medical illness increases the odds of CAD by 3.6 times (aOR = 3.56, 95% CI: 1.68, 7.54) as compared to participants who were free from medical problems. Those participants who encountered pregnancy danger signs were 3 times (AOR = 2.66, (95% CI: 1.06, 6.67) higher risk to experience CAD as compared to their counterparts. The odds of CAD were 2 times (AOR = 2.11 (1.15, 3.92) higher among participants who experienced life-threatening events in the past six months. Likewise, the odds of CAD were 3.5 times (AOR = 3.51, 95% CI: 1.85, 6.64) higher among household food insecure participants (Table 3).

Table 3. Factors associated with comorbid anxiety and depression among pregnant women in Arba Minch Zuria district, Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2019, (n = 667).

| Variables | aCAD | bcOR (95% CI) | P-value | caOR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N, %) | No (N, %) | |||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 60 (9.3) | 586 (90.7) | 0.20 (0.10, 0.53) | 0.001 | 0.16 (0.05, 0.56)** | 0.004 |

| Otherd | 7 (33.3) | 14 (66.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Intimate partner violence | ||||||

| Yes | 42 (17.3) | 201 (82.7) | 3.33 (1.98, 5.63) | < 0.001 | 1.61 (0.88, 2.94) | 0.123 |

| No | 25 (5.9) | 399 (94.1) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Wealth quintile | ||||||

| Low | 9 (4.1) | 212 (95.9) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Medium | 28 (12.4) | 197 (87.6) | 3.35 (1.54, 7.27) | 0.002 | 1.54 (0.64, 3.69) | 0.333 |

| High | 30 (13.6) | 191 (86.4) | 3.70 (1.71, 7.99) | 0.001 | 2.83 (1.17, 6.84)* | 0.021 |

| Medical Illness | ||||||

| Yes | 22 (37.3) | 37 (62.7) | 7.4 (4.05, 13.67) | < 0.001 | 3.56 (1.68, 7.54)** | 0.001 |

| No | 45 (7.4) | 563 (92.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Gestational age in weeks | ||||||

| ≤12 | 2 (4.4) | 44 (95.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 13–24 | 20 (7.9) | 234 (92.1) | 1.9 (0.42, 8.33) | 0.406 | 1.62 (0.32, 8.10) | 0.559 |

| ≥25 | 45 (12.3) | 322 (87.7) | 3.1 (0.72, 13.12) | 0.129 | 2.40 (0.50, 11.58) | 0.276 |

| Presence of danger signs in the current pregnancy | ||||||

| Yes | 12 (27.9) | 31 (72.1) | 4.0 (1.95, 8.24) | < 0.001 | 2.66 (1.06, 6.67)* | 0.038 |

| No | 55 (8.8) | 569 (91.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Social support | ||||||

| Poor | 63 (11.6) | 480 (88.4) | 3.94 (1.4, 11.03) | 0.009 | 2.56 (0.80, 8.23) | 0.113 |

| Good | 4 (3.2) | 120 (96.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Experience of life-threatening events | ||||||

| Yes | 40 (22.7) | 136 (77.3) | 5.05 (2.99, 8.54) | < 0.001 | 2.11 (1.15, 3.92)* | 0.017 |

| No | 27 (5.5) | 464 (94.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Substance abuse (alcohol) | ||||||

| Yes | 10 (19.6) | 41 (80.4) | 2.39 (1.14, 5.03) | 0.021 | 1.96 (0.81, 4.75) | 0.137 |

| No | 57 (9.3) | 559 (90.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Household food security status | ||||||

| Secure | 25 (5.2) | 456 (94.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Insecure | 42 (22.6) | 144 (77.4) | 5.32 (3.13, 9.03) | < 0.001 | 3.51 (1.85, 6.64) ** | < 0.001 |

aComorbid anxiety and depression.

bCrude Odds Ratio.

cAdjusted Odds Ratio.

dDivorced, widowed, married but not living together.

*Significant at P-value < 0.05.

**significant at P-value < 0.01.

Discussion

In our study, 10.04% of the pregnant women had antenatal CAD. High socioeconomic status, medical illness, pregnancy danger signs, life-threatening events and household food insecurity increased the odds of CAD. This finding is in line with the studies conducted in Pakistan 13.5% [6], Spain (9.5%) [7], South Africa (7.6% early and 9.7% in late pregnancy) [9] and a meta-analysis conducted by Falah and coworkers (9.5%) [4]. On the other hand, this finding is higher than the study conducted in Singapore (5.0%) [5] and very much lower than the study in Turkey (47.6%) [7]. These discrepancies might be due to differences in anxiety and depression measurement scales and cut-off point used, geographical settings, pregnancy trimester, socio-economic status and socio-cultural differences.

The likelihood of developing CAD during pregnancy was 84.0% lower among married women as compared to their counterparts. This finding is in agreement with the study conducted in Tanzania, where CAD was 4.5 times higher among single [40]. The possible justification is that presence of a husband with pregnant mother increases self-esteem, decreases stress and improves psychological wellbeing [52]. Furthermore, getting pregnant without formal marriage is strongly stigmatized by the community that results in stress and abortion, which further exposes the mother to depression and anxiety [53].

The odds of CAD were about three times higher among participants ranked in the highest wealth quintile. This is contrary to previous studies, where low socio-economic status is a risk factor for depression and anxiety [54, 55]. The possible justification is that economic status and necessity are parallel; struggle to attain more wealth leads to stress and tension. Also, in some cultures the household’s resources are merely controlled by the husband, the woman always needs the permission of her husband to do anything despite the household wealth. Besides, when a man is rich enough the likelihood of polygyny (i.e. marriage between a man and multiple women) also increased; which further increases the odds of emotional abuse for the woman [56].

The odds of facing CAD were nearly four times higher among participants with co-existing medical illnesses. This is supported by previous studies, where the history of chronic medical illness increases the occurrence of mental disorders [11, 12]. Moreover, the presence of pregnancy danger signs increases the odds of CAD by threefold. This is consistent with a previous study in which the presence of obstetrics complications are associated with depression and anxiety [29]. This is probably due to increased frequency of health facility visits, incur extra cost and inhibition of the mother to lead a healthy life secondary to pregnancy-related ailments.

Those participants who experienced life-threatening events within the last six months were two times higher risk of encountering CAD. This finding is supported by previously published studies where adverse and stressful life events increase the likelihood of antenatal depression and anxiety [2, 57]. The possible justification is that stressful life events aggravate pregnancy-related complications including mental health problems.

Our study, also revealed that household food insecurity increases the odds of CAD by fourfold. Although no study exactly supports our finding, previously published studies consistently reported that household food insecurity increases the risk of perinatal common mental disorders [13, 14]. Besides, a study from South Africa also demonstrated that household food insecurity increases the odds of depression by fivefold; on the other hand, depression increases the odds of food insecurity by fourfold [15]. It is difficult to justify the exact mechanism by which household food insecurity results in depression and/or anxiety. But it might be because as the parents do not maintain their daily food requirements for them and their children they feel guilty and exposed to mental health problems.

In summary, the present study revealed that prenatal CAD is common in the study area. The study provides invaluable information for healthcare providers to address potential risk factors for CAD. Despite prenatal CAD results in serious health squeal both on the mother and her fetus, mental health services are very poor in Ethiopia [27]. Scholars suggested that mindfulness-based cognitive therapies (MBCT) are imperative to decrease depression and anxiety in pregnant women [58]. However, in Ethiopia, guidelines/manuals used to treat pregnant women with depression/anxiety are not available and the healthcare providers working in the antenatal care units are not able to screen and manage these conditions. In low-income countries like Ethiopia with limited mental health centers and very low psychiatry professionals, any healthcare provider working in the antenatal care unit must be trained about common mental disorders screening and mindfulness interventions given for pregnant women. Besides, maternal mental health services must be integrated with other services like reproductive, maternal and child health care services. Moreover, psychiatry professionals in collaboration with the federal ministry of health should develop easily accessible and understandable maternal mental health intervention guidelines.

Even though this study follows scientific methodology it might encounter the following limitations: social desirability bias might underestimate the response of some measurements such as IPV, substance abuse and household food insecurity. Moreover, the GAD-7 used to measure anxiety was not validated in the Ethiopian context; which might affect the result of the current study. Thus, researchers and psychiatry professionals must develop locally validated mental disorder screening tools.

Conclusions

Generally, one in ten women encountered CAD in the study area. Being married, ranked in the highest wealth quintile, having medical illness, encountering pregnancy danger signs, experiencing life-threatening events and household food insecurity was significantly associated with CAD. Thus, incorporating psychological and psychosocial counseling as part of the routine ANC, early detection and treatment of pregnancy-related ailments and medical illness, and marriage counseling are pillars to diminish the onset of mental disorders during pregnancy.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge senior staffs in Arba Minch University, study participants, data collectors, supervisors and staff of AM-HDSS for their priceless support.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

AB received award from Arba Minch University (www.amu.edu.et), with an award number of GOV/AMU/TH/CMHS/NUR/DSS/03/10.The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (2014) Maternal mental health.

- 2.Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, Pariante CM (2016) Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: a systematic review. Journal of affective disorders 191: 62–77. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jha S, Salve HR, Goswami K, Sagar R, Kant S (2018) Burden of common mental disorders among pregnant women: A systematic review. Asian journal of psychiatry 36: 46–53. 10.1016/j.ajp.2018.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R, Dennis CL (2017) The prevalence of antenatal and postnatal co-morbid anxiety and depression: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 47: 2041–2053. 10.1017/S0033291717000617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thiagayson P, Krishnaswamy G, Lim ML, Sung SC, Haley CL, et al. (2013) Depression and anxiety in Singaporean high-risk pregnancies—prevalence and screening. General hospital psychiatry 35: 112–116. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Premji SS, Lalani S, Shaikh K, Mian A, Forcheh N, et al. (2020) Comorbid Anxiety and Depression among Pregnant Pakistani Women: Higher Rates, Different Vulnerability Characteristics, and the Role of Perceived Stress. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.González-Mesa E, Kabukcuoglu K, Blasco M, Körükcü O, Ibrahim N, et al. (2020) Comorbid anxiety and depression (CAD) at early stages of the pregnancy. A multicultural cross-sectional study. Journal of affective disorders 270: 85–89. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawyer A, Ayers S, Smith H (2010) Pre- and postnatal psychological wellbeing in Africa: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 123: 17–29. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redinger S, Pearson RM, Houle B, Norris SA, Rochat TJ (2020) Antenatal depression and anxiety across pregnancy in urban South Africa. J Affect Disord 277: 296–305. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Getinet W, Amare T, Boru B, Shumet S, Worku W, et al. (2018) Prevalence and Risk Factors for Antenatal Depression in Ethiopia: Systematic Review. Depress Res Treat 2018: 3649269. 10.1155/2018/3649269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gadanya MA, Abulfathi AA, Ahmad FA (2018) Anxiety and depression in pregnancy: prevalence and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital Kano, Nigeria. Annals of African Medical Research 1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woldetsadik AM, Ayele AN, Roba AE, Haile GF, Mubashir K (2019) Prevalence of common mental disorder and associated factors among pregnant women in South-East Ethiopia, 2017: a community based cross-sectional study. Reprod Health 16: 173. 10.1186/s12978-019-0834-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Power M, Uphoff E, Kelly B, Pickett KE (2017) Food insecurity and mental health: an analysis of routine primary care data of pregnant women in the Born in Bradford cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 71: 324–328. 10.1136/jech-2016-207799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jebena MG, Taha M, Nakajima M, Lemieux A, Lemessa F, et al. (2015) Household food insecurity and mental distress among pregnant women in Southwestern Ethiopia: a cross sectional study design. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 15: 250. 10.1186/s12884-015-0699-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abrahams Z, Lund C, Field S, Honikman S (2018) Factors associated with household food insecurity and depression in pregnant South African women from a low socio-economic setting: a cross-sectional study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 53: 363–372. 10.1007/s00127-018-1497-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonari L, Pinto N, Ahn E, Einarson A, Steiner M, et al. (2004) Perinatal risks of untreated depression during pregnancy. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 49: 726–735. 10.1177/070674370404901103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M, Figueiredo B, Deeds O, et al. (2010) Comorbid depression and anxiety effects on pregnancy and neonatal outcome. Infant Behav Dev 33: 23–29. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sabri Y, Nabel H (2015) The impact of anxiety and depression during pregnancy on fetal growth and the birth outcome. Egyptian Journal of Psychiatry 36: 95. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Accortt EE, Cheadle AC, Dunkel Schetter C (2015) Prenatal depression and adverse birth outcomes: an updated systematic review. Matern Child Health J 19: 1306–1337. 10.1007/s10995-014-1637-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanlon C, Medhin G, Alem A, Tesfaye F, Lakew Z, et al. (2009) Impact of antenatal common mental disorders upon perinatal outcomes in Ethiopia: the P‐MaMiE population‐based cohort study. Tropical Medicine & International Health 14: 156–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibanez G, Bernard JY, Rondet C, Peyre H, Forhan A, et al. (2015) Effects of antenatal maternal depression and anxiety on children’s early cognitive development: a prospective cohort study. PloS one 10. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Capron LE, Glover V, Pearson RM, Evans J, O’Connor TG, et al. (2015) Associations of maternal and paternal antenatal mood with offspring anxiety disorder at age 18 years. Journal of affective disorders 187: 20–26. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shahhosseini Z, Pourasghar M, Khalilian A, Salehi F (2015) A review of the effects of anxiety during pregnancy on children’s health. Mater Sociomed 27: 200–202. 10.5455/msm.2015.27.200-202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bitew T, Hanlon C, Kebede E, Medhin G, Fekadu A (2016) Antenatal depressive symptoms and maternal health care utilisation: a population-based study of pregnant women in Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16: 301. 10.1186/s12884-016-1099-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pampaka D, Papatheodorou SI, AlSeaidan M, Al Wotayan R, Wright RJ, et al. (2019) Postnatal depressive symptoms in women with and without antenatal depressive symptoms: results from a prospective cohort study. Arch Womens Ment Health 22: 93–103. 10.1007/s00737-018-0880-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization (2013) Mental health action plan 2013–2020.

- 27.Baron EC, Hanlon C, Mall S, Honikman S, Breuer E, et al. (2016) Maternal mental health in primary care in five low- and middle-income countries: a situational analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 16: 53. 10.1186/s12913-016-1291-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayele TA, Azale T, Alemu K, Abdissa Z, Mulat H, et al. (2016) Prevalence and associated factors of antenatal depression among women attending antenatal care service at gondar university hospital, northwest Ethiopia. PloS one 11. 10.1371/journal.pone.0155125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bekele D, Worku A, Wondimagegn D (2017) Prevalence and Associated Factors of Mental Distress during Pregnancy among Antenatal Care Attendees at Saint Paul’s Hospital, Addis Ababa. Obstetrics & Gynecology International Journal 7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biratu A, Haile D (2015) Prevalence of antenatal depression and associated factors among pregnant women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Reproductive health 12: 99. 10.1186/s12978-015-0092-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.bekele D, worku A, wondmagegn D (2017) Prevalence and Associated Factors of Mental Distress during Pregnancy among Antenatal Care Attendees at Saint Paul’s Hospital, Addis Ababa. Obstet Gynecol Int J 7: 00269. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biratu a, Haile D(2015) Prevalence of antenatal depression and associated factors among pregnant women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Reproductive Health 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahile M, Segni M, Awoke T, Bekele D (2017) Prevalence and predictors of antenatal depressive symptoms among women attending Adama Hospital Antenatal Clinic, Adama, Ethiopia. International Journal of Nursing and Midwifery 9: 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bitew T, Hanlon C, Kebede E, Honikman S, Fekadu A (2017) Antenatal depressive symptoms and perinatal complications: a prospective study in rural Ethiopia. BMC psychiatry 17: 301. 10.1186/s12888-017-1462-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belay YA, Moges NA, Hiksa FF, Arado KK, Liben MLJDr, et al. (2018) Prevalence of Antenatal Depression and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care at Dubti Hospital: A Case of Pastoralist Region in Northeast Ethiopia. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ayele TA, Azale T, Alemu K, Abdissa Z, Mulat H, et al. (2016) Prevalence and Associated Factors of Antenatal Depression among Women Attending Antenatal Care Service at Gondar University Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. PLOS ONE 11: e0155125. 10.1371/journal.pone.0155125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bisetegn TA, Mihretie G, Muche T (2016) Prevalence and Predictors of Depression among PregnantWomen in Debretabor Town, Northwest Ethiopia. PLOS ONE 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.(2013) Ethiopian Universities Health and Demographic Surveillance System Network Data Sharing and Release Policy. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whiteman MK, Tepper NK, Kottke M, Curtis KM, Goedken P, et al. (2014) Using a checklist to assess pregnancy in teenagers and young women. Obstetrics and gynecology 123: 777. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ngocho JS, Watt MH, Minja L, Knettel BA, Mmbaga BT, et al. (2019) Depression and anxiety among pregnant women living with HIV in Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. PLoS One 14: e0224515. 10.1371/journal.pone.0224515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh H (2013) Mobile data collection using an android device. IJCST 4: 200–202. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2001) The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16: 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gelaye B, Williams MA, Lemma S, Deyessa N, Bahretibeb Y, et al. (2013) Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for depression screening and diagnosis in East Africa. Psychiatry Res 210: 653–661. 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166: 1092–1097. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhong Q-Y, Gelaye B, Zaslavsky AM, Fann JR, Rondon MB, et al. (2015) Diagnostic validity of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among pregnant women. PloS one 10. 10.1371/journal.pone.0125096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hodgson R, Alwyn T, John B, Thom B, Smith AJA, et al. (2002) The FAST alcohol screening test. 37: 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown JB, Lent B, Brett PJ, Sas G, Pederson LL (1996) Development of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool for use in family practice. Fam Med 28: 422–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rabin R, Jennings J, Campbell J, Bair-Merritt M (2009) Intimate partner violence screening tools. American Journal of Prev Med 36: 439. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boen H (2012) Characteristics of senior centre users–and the impact of a group programme on social support and late-life depression. Norsk Epidemiologi 22: 261. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brugha T, Cragg D (1990) The List of Threatening Experiences: the reliability and validity of a brief life events questionnaire. Acta Psychiatr Scand 82: 77. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb01360.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coates J, Swindale A, Bilinsky P (2007) Household Food Insecurity Access Scale for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Washington DC: 29pp. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sokoya M, Farotimi A, Ojewole F (2014) Women’s perception of husbands’ support during pregnancy, labour and delivery. IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science 3: 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fubam RM, Odukogbe A, Dairo MD (2019) Psychological and social effects of pregnancy in unmarried young women in Bui, Northwest, Cameroon. Am J Biomed Life Sci 7: 190–198. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nasreen HE, Kabir ZN, Forsell Y, Edhborg M (2011) Prevalence and associated factors of depressive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy: a population based study in rural Bangladesh. BMC Womens Health 11: 22. 10.1186/1472-6874-11-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pampaka D, Papatheodorou SI, AlSeaidan M, Al Wotayan R, Wright RJ, et al. (2018) Depressive symptoms and comorbid problems in pregnancy—results from a population based study. J Psychosom Res 112: 53–58. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ebrahim NB, Atteraya MS (2020) Polygyny and Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Among Ethiopian Women. Global Social Welfare: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nasreen HE, Rahman JA, Rus RM, Kartiwi M, Sutan R, et al. (2018) Prevalence and determinants of antepartum depressive and anxiety symptoms in expectant mothers and fathers: results from a perinatal psychiatric morbidity cohort study in the east and west coasts of Malaysia. BMC Psychiatry 18: 195. 10.1186/s12888-018-1781-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zemestani M, Fazeli Nikoo Z (2020) Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for comorbid depression and anxiety in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Womens Ment Health 23: 207–214. 10.1007/s00737-019-00962-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]