Abstract

Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) play critical roles in protecting germline genome integrity and promoting normal spermiogenic differentiation. In mammals, there are two populations of piRNAs: pre-pachytene and pachytene. Transposon-rich pre-pachytene piRNAs are expressed in fetal and perinatal germ cells and are required for retrotransposon silencing, whereas transposon-poor pachytene piRNAs are expressed in spermatocytes and round spermatids and regulate mRNA transcript levels. MOV10L1, a germ cell-specific RNA helicase, is essential for the production of both populations of piRNAs. Although the requirement of the RNA helicase domain located in the MOV10L1 C-terminal region for piRNA biogenesis is well known, its large N-terminal region remains mysterious. Here we report a novel Mov10l1 mutation, named yama, in the Mov10l1 N-terminal region. The yama mutation results in a single amino acid substitution V229E. The yama mutation causes meiotic arrest, de-repression of transposable elements, and male sterility because of defects in pre-pachytene piRNA biogenesis. Moreover, restricting the Mov10l1 mutation effects to later stages in germ cell development by combining with a postnatal conditional deletion of a complementing wild-type allele causes absence of pachytene piRNAs, accumulation of piRNA precursors, polar conglomeration of piRNA pathway proteins in spermatocytes, and spermiogenic arrest. Mechanistically, the V229E substitution in MOV10L1 reduces its interaction with PLD6, an endonuclease that generates the 5′ ends of piRNA intermediates. Our results uncover an important role for the MOV10L1-PLD6 interaction in piRNA biogenesis throughout male germ cell development.

Author summary

Small non-coding RNAs play critical roles in silencing of exogenous viruses, endogenous retroviruses, and transposable elements, and also play multifaceted roles in controlling gene expression. Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are found in gonads in diverse species from flies to humans. An evolutionarily conserved function of piRNAs is to silence transposable elements through an adaptive mechanism and thus to protect germline genome integrity. In mammals, piRNAs also provide a poorly understood function to regulate postmeiotic differentiation of spermatids. More than two dozen proteins are involved in the piRNA pathway. MOV10L1, a germ-cell-specific RNA helicase, binds to piRNA precursors to initiate piRNA biogenesis. Here we have identified a single amino acid substitution (V229E) in MOV10L1 in the yama mouse mutant. When constitutively expressed as the only source of MOV10L1 throughout germ cell development, the yama mutation abolishes piRNA biogenesis, de-silences transposable elements, and causes meiotic arrest. When the mutant phenotype is instead revealed only later in germ cell development by conditionally inactivating a wild-type copy of the gene, the point mutant abolishes formation of later classes of piRNAs and again disrupts germ cell development. Point mutations in MOV10L1 may thus contribute to male infertility in humans.

Introduction

Transposable elements, which constitute around 40% of the mammalian genome, play important roles in genome evolution. However, their mobilization can disrupt gene function and cause diseases [1,2]. Production of piRNAs in the germline is one of the major mechanisms to silence retrotransposons to protect genome integrity. piRNAs are small (26–31 nt) non-coding RNAs with a preference for a 5′ uridine nucleotide [3]. piRNAs associate with homologs of the Drosophila melanogaster Piwi protein, which in mouse include MIWI (PIWIL1), MILI (PIWIL2), and MIWI2 (PIWIL4). In the mouse germline, two populations of piRNAs are present: pre-pachytene and pachytene. Pre-pachytene piRNAs associate with MILI and MIWI2 in embryonic and perinatal germ cells and are required for DNA methylation and retrotransposon silencing [4–7]. Pachytene piRNAs are present in spermatocytes and round spermatids and are associated with MILI and MIWI [8–10]. In contrast with the predominant role of pre-pachytene piRNAs in silencing transposable elements, pachytene piRNAs are implicated in cleavage of messenger RNAs in testis [11–14]. The mRNA cleavage is dependent on the slicer activity of MIWI [14,15]. In addition, MIWI binds to and stabilizes spermiogenic mRNAs directly [16]. MIWI and pachytene piRNAs also function in activating translation of a subset of spermiogenic mRNAs [17]. Thus, piRNAs perform diverse functions throughout male germ cell development in mammals.

In addition to the Piwi proteins, more than 20 other proteins are involved in the piRNA pathway [3]. A number of Tudor domain-containing (TDRD) proteins (TDRD1 [18–20], TDRD5 [21,22], TDRD9 [23,24], TDRD12 [25], and TDRKH [26,27]), in general, function as scaffold proteins in the assembly of piRNA ribonucleoprotein particles by binding to arginine-methylated Piwi proteins [28–31]. The Drosophila Zucchini protein functions as an endonuclease in piRNA biogenesis [32–34], and its mammalian orthologue PLD6 is essential for piRNA biogenesis in mouse [35,36]. Zucchini/PLD6 cleaves precursor transcripts into intermediate piRNA fragments, whose 5′ ends are bound and protected by Piwi proteins; subsequently the Piwi-bound fragments are trimmed to the length of mature piRNAs by the 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease PNLDC1 [37–40].

MOV10L1, a germ cell-specific RNA helicase, is a key regulator of piRNA biogenesis. MOV10L1 interacts with all Piwi proteins and binds to piRNA precursors to initiate primary piRNA biogenesis [41,42]. MOV10L1 helicase resolves G-quadruplex RNA secondary structures [42,43]. Constitutive inactivation of MOV10L1 by deletion of the helicase domain leads to loss of mature piRNAs, de-repression of retrotransposons, arrest during meiotic prophase, and male infertility [41,44]. In contrast, conditional deletion of the helicase domain-encoding region of Mov10l1 postnatally leads to arrest during postmeiotic spermatid differentiation, without overt defects in transposon silencing [45]. Two point mutations previously generated in the MOV10L1 C-terminal RNA helicase domain revealed an essential role for its RNA helicase activity in piRNA biogenesis [42,46]. However, the function of the large N-terminal region of MOV10L1 remains unknown, because it does not share any similarity with known protein domains. We address this question here using a Mov10l1 V229E missense mutant recovered as part of a recently described N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis screen for novel meiotic mutants [47,48]. This substitution attenuates the interaction between MOV10L1 and PLD6 and causes a profound failure in both pre-pachytene and pachytene piRNA biogenesis. We named this mutant allele yama, for ‘yields abnormal meiosis and Mov10l1-affected’. Other hits we previously described from the screen are rahu, ketu and shani [47–49]. Yama, Rahu, Ketu and Shani are harbingers of misfortune in Vedic mythology.

Results

Mov10l1yama/yama males exhibit meiotic arrest and sterility

The Mov10l1yama allele was isolated in an ENU mutagenesis screen for mutants with autosomal recessive defects in meiosis. Details of the screen are provided elsewhere [47,48]. Briefly, mutagenesis was performed on male mice of the C57BL/6J strain, and then a three-generation breeding scheme was carried out including outcrossing with females of the FVB strain (Fig 1A). Third-generation male offspring were screened for meiotic defects by immunostaining spermatocyte squash preparations for well-established meiotic markers SYCP3 and γH2AX, which enabled rapid assessment of defects in both synapsis and meiotic recombination.

Fig 1. Isolation of the Mov10l1yama allele.

(A) Breeding scheme used to isolate mutants with autosomal recessive defects in meiosis. Male mice of the C57BL/6J strain (B6) were mutagenized with ENU and bred to wild-type females of the FVB/NJ strain (FVB) to generate founder (F1) males that were potential mutation carriers. Each F1 male was bred to wild-type FVB females to produce second generation (G2) offspring, and then G2 daughters were crossed back to their F1 sire to produce third-generation (G3) offspring. G3 males were screened for meiotic defects. For a line carrying a single autosomal recessive mutation of interest, roughly one half of G2 females were expected to be carriers and one eighth of all G3 males were expected to be homozygous. (B) Screen results obtained for the yama line where the F1 male was harem-bred to seven G2 females. This generated 27 G3 males; 18 males were wild-type and nine males displayed the yama phenotype. (C) SNP genotypes of four G3 yama mutants (A, B, C, D) obtained using the Illumina Medium Density Linkage Panel are shown on the left. As mutagenesis was performed on B6 males, we expected ENU-induced mutations to be linked to B6 variants for strain polymorphisms that differed between B6 and FVB. We also expected G3 mutants to be homozygous for those same linked B6 variants. Therefore, we mapped the phenotype-causing mutation by searching for regions of B6 homozygosity that are shared between mutants. The single 32.45-Mbp region of B6 SNP homozygosity that is shared between mutants A, B, C, and D is highlighted in grey. A detailed view of variants within this region is shown in the middle for two informative yama mutants (B, D). We narrowed this region by manually genotyping more G3 mutants and phenotypically normal siblings for additional SNPs within this region. We expected phenotypically normal G3 mice not to be homozygous for the phenotype-causing mutation or its linked B6 variants. A detailed view of variants used to refine the mapped region is shown on the right for one informative phenotypically normal mouse (E′). The final mapped region was a 17.44-Mbp interval on Chromosome 15, flanked by heterozygous SNPs rs31562483 (Chr15:85684090) and rs13482751 (Chr15:102951530).

In a screen line we named yama, nine of 27 third-generation males screened displayed abnormal SYCP3 and γH2AX immunostaining patterns indicative of meiotic defects (Fig 1B). The phenotype was first mapped using SNP genotyping arrays and manual genotyping of strain polymorphisms to a 17.44-Mb interval on Chromosome 15 (Fig 1C) [47]. Whole-exome sequencing was performed on DNA from one mutant, and un-annotated sequence variants within the mapped region were identified as previously described [47]. This analysis revealed a single exonic mutation located in Mov10l1. This variant is a T to A transversion at position Chr15:88994968 (GRCm38/mm10), resulting in a missense mutation in exon 5: V229E (codon GTG229GAG) (S1 Fig). Valine 229 in MOV10L1 is highly evolutionarily conserved (Fig 2A). As detailed below, the targeted Mov10l1 mutation and the yama mutation confer similar phenotypes and fail to complement one another. We conclude that the ENU-induced V229E mutation disrupts MOV10L1 function and is the cause of the yama mutant phenotype.

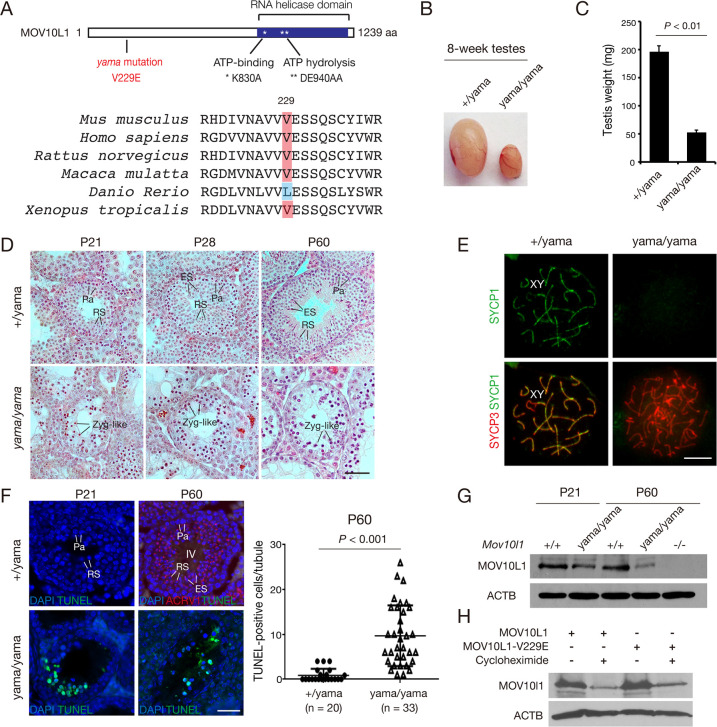

Fig 2. The Mov10l1 V229E mutation causes meiotic arrest and male sterility.

(A) Schematic diagram of the full-length mouse MOV10L1 protein (XP_006521619) and the conservation of the V229 residue. K830A and DE940.941AA mutations in the RNA helicase domain were previously reported and included for comparison [42,46]. (B) Dramatic size reduction of testis from 8-week-old Mov10l1yama/yama mice. (C) Reduction of testis weight in 8-week-old Mov10l1yama/yama mice (mean ± s.d.; n = 3 per genotype). (D) Histology (hematoxylin/eosin staining) of postnatal day 21 (P21), P28 and P60 testes from control and Mov10l1yama/yama mice. Abbreviations: Zyg-like, zygotene-like spermatocytes; Pa, pachytene spermatocytes; RS, round spermatid; ES, elongating spermatid. Scale bar, 50 μm. (E) Synapsis analysis of spermatocytes from P60 (adult) testes. Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) TUNEL analysis of seminiferous tubules from P21 and P60 testes. Quantification of TUNEL-positive spermatocytes at P60 is plotted. n, the number of stage IV tubules from Mov10l1+/yama testes or TUNEL-positive tubules from Mov10l1yama/yama testes. ACRV1, a marker of acrosome [67], is used for staging of seminiferous tubules in wild-type P60 testes. Scale bar, 50 μm. (G) Western blot analysis of MOV10L1 in P21 and P60 testes. Mov10l1-/- (knockout) testis serves as a negative control. ACTB serves as a loading control. (H) Western blot analysis of wild-type MOV10L1 and MOV10L1V229E in HEK293T cells. Transfected cells were collected after 24 hours with or without cycloheximide. Cycloheximide inhibits de novo protein synthesis so that protein stability can be compared in the absence of translation. The MOV10L1 antibody (G and H) was raised against the N-terminal region (amino acid 1–101) as previously reported [41].

Mov10l1yama/yama mice were viable and exhibited no obvious gross abnormalities. Mov10l1yama/yama females were fertile (7.3 ± 1.0 pups/litter, n = 4) but males were sterile. The body weight was comparable between 8-week-old Mov10l1yama/yama mice (24.2 ± 1.1 g, n = 3) and Mov10l1+/yama littermates (23.8 ± 0.9 g, n = 3). However, the testis weight of adult Mov10l1yama/yama males was sharply reduced in comparison with their heterozygous littermates (Fig 2B and 2C). We next examined histology of testes from juvenile and adult males at ages when testes are enriched for specific germ cell types. Germ cells enter meiosis in a semi-synchronous wave during the second week after birth [50]. At postnatal day 21 (P21), testes contain meiotic cells and round spermatids; elongated spermatids are present by P28; by adulthood (P60), several waves of meiosis have occurred and testes contain a mixed population of germ cells at all stages. Mov10l1+/yama P21 and P28 testes contained meiotic cells and spermatids, as expected, and adult (P60) testes contained a full spectrum of germ cells: spermatogonia, spermatocytes, round spermatids, and elongated spermatids (Fig 2D). In contrast, Mov10l1yama/yama testes from P21, P28, and P60 all lacked post-meiotic spermatids (Fig 2D). While Sertoli-cell-only tubules were not observed in P60 or younger Mov10l1yama/yama testes, tubules with a Sertoli-cell-only phenotype or a severe loss of germ cells accounted for 25% of all tubules in 4-month-old (n = 2 mice) and 71% of all tubules in 7-month-old (n = 2 mice) Mov10l1yama/yama testes, showing a progressive loss of germ cells with age (S2 Fig).

Spermatocytes from mice homozygous for a targeted deletion of the helicase domain of Mov10l1 (Mov10l1-/-) arrest early in meiosis leading to a complete lack of post-meiotic germ cells, hypogonadism and infertility [41,44]. Our initial observations indicated similar phenotypes for Mov10l1yama/yama, therefore we evaluated meiotic events more closely. We examined chromosomal synapsis in spermatocytes by immunofluorescence of nuclear spreads with antibodies against SYCP1 and SYCP3, components of the synaptonemal complex (SC). The SC is a tripartite proteinaceous structure that physically links homologous chromosomes during meiosis. SYCP3 is a component of the SC axial/lateral elements formed along the axis of each chromosome, and SYCP1 is a SC transverse element that connects the two lateral elements to synapse homologous chromosomes [51]. In control (Mov10l1+/yama) pachytene spermatocytes, all chromosomes were fully synapsed except the sex chromosomes (Fig 2E). In contrast, the most advanced Mov10l1yama/yama spermatocytes assembled the SC axial elements containing SYCP3 but lacked chromosomal synapsis as shown by the absence of SYCP1, and thus were considered zygotene-like spermatocytes (Fig 2E). This is consistent with our histological analyses where the most advanced spermatocytes in Mov10l1yama/yama appeared zygotene-like (Fig 2D). We interpret the absence of more advanced stages to be due to elimination of aberrant cells by apoptosis. Indeed, TUNEL analysis revealed that apoptosis was strongly increased in P21 (juvenile; when wild-type testes are enriched for meiotic cells and round spermatids) and in P60 (adult; when wild-type testes contain a full spectrum of germ cell types) Mov10l1yama/yama testes, suggesting that defective spermatocytes were eliminated in the mutants (Fig 2F). We conclude that the V229E mutation causes a blockade in early meiosis similar to that previously reported for the Mov10l1-/- mutant [41,44].

Western blot analysis showed that the abundance of MOV10L1 protein was modestly lower in Mov10l1yama/yama testis than wild-type at P21, and was more substantially reduced at P60 (Fig 2G). Because MOV10L1 is abundantly expressed in pachytene spermatocytes [41], and P21/P60 wild-type testes were rich in pachytene spermatocytes but the mutant testes were depleted of normal pachytene spermatocytes, the reduction of MOV10L1 abundance in the mutant testis could be due to depletion of spermatocytes. It is also possible that the MOV10L1 (V229E) protein was less stable. To test the latter possibility, we expressed MOV10L1 and MOV10L1V229E in HEK293T cells separately. The protein abundance of MOV10L1 and MOV10L1V229E was similar, indicating that the V229E substitution does not affect the intrinsic stability of MOV10L1 (Fig 2H).

De-repression of LINE1 and IAP retrotransposons in Mov10l1yama/yama testis

Because MOV10L1-dependent biogenesis of pre-pachytene pRNAs is required for silencing of retrotransposons [41,42], we sought to address whether transposable elements were affected in Mov10l1yama/yama testes. We examined the expression of LINE1 and IAP in P21 and P60 Mov10l1+/yama and Mov10l1yama/yama testis sections by immunostaining with anti-LINE1 ORF1 and anti-IAP GAG antibodies. LINE1 and IAP were barely detected in the Mov10l1+/yama testes but were highly upregulated in the Mov10l1yama/yama testes (Fig 3A and 3B). Consistent with the upregulation patterns in Mov10l1-null testes [41], LINE1 was mainly upregulated in spermatocytes, whereas IAP was de-repressed in spermatogonia in Mov10l1yama/yama testes (Fig 3A and 3B). These results were confirmed by Western blot and quantitative RT-PCR analyses in Mov10l1+/yama and Mov10l1yama/yama testes at different ages: P10, P21, and P60 (Fig 3C and 3D). P10 testes are expected to contain spermatogonia and pre-leptotene spermatocytes but no later germ cell types. These data demonstrate that retrotransposons are de-repressed in Mov10l1yama/yama testes, similar to Mov10l1-/- mice. We infer that this is likely due to disruption of pre-pachytene piRNA biogenesis. The differential de-repression of LINE1 and IAP in postnatal testes also occurs in Mili or Tex15-deficient mice, suggesting the presence of additional retrotransposon-specific regulating mechanisms in different germ cells [52–54].

Fig 3. De-repression of retrotransposons in Mov10l1yama/yama testis.

Sections of testes from P21 and P60 Mov10l1yama/yama and control males were immunostained with anti-LINE1 ORF1 (A) and anti-IAP GAG (B) antibodies [68]. DNA was stained with DAPI. (C) Western blot analysis of LINE1 ORF1 and IAP GAG proteins in testes. ACTB serves as a loading control. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of LINE1 and IAP transcripts (mean ± s.d.) in P10 (n = 4) and P21 (n = 3) testes. *, P < 0.05. (E, F) Sections of testes from P21 and P60 Mov10l1yama/yama and control males were immunostained with anti-MILI (E) and anti-MIWI (F). Abbreviations: Spg, spermatogonia; Pa, pachytene spermatocytes; Spc, spermatocytes. Scale bars, 50 μm.

We next examined the expression and localization of MILI and MIWI, two postnatal Piwi proteins, in P21 and P60 Mov10l1+/yama and Mov10l1yama/yama testes. As expected, MILI was detected in both spermatogonia and pachytene spermatocytes in Mov10l1+/yama testis (Fig 3E). However, MILI was only detected in spermatogonia in Mov10l1yama/yama testes, which may reflect the absence of normal pachytene spermatocytes in the mutant testes (Fig 3E). MIWI was expressed in pachytene spermatocytes but not in spermatogonia in Mov10l1+/yama testis, and not detected in the remaining spermatocytes in Mov10l1yama/yama testes, which again may reflect the absence of normal pachytene spermatocytes in mutants (Fig 3F).

Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre males display round spermatid arrest

The Mov10l1yama/yama testes are devoid of normal pachytene spermatocytes and thus are expected to lack pachytene piRNAs (Fig 2D and 2E). To assess the function of MOV10L1 N-terminal region in pachytene piRNA production, we bypassed the early meiotic block by using a Mov10l1fl conditional (floxed helicase domain-encoding region) allele and Ngn3-Cre mice, in which Cre expression begins in postnatal day 7 [41,55]. Complete postnatal inactivation of Mov10l1 (Mov10l1fl/- Ngn3-Cre) leads to post-meiotic arrest at the round spermatid stage [45]. We generated Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre mice and compared their phenotype to Mov10l1fl/- Ngn3-Cre mice. The testes from Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre males were smaller than controls (Fig 4A and 4B). Histological analysis showed that spermatogenesis from P21 (juvenile) Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre mice progressed to the round spermatid stage as in wild-type (Fig 4C). However, germ cells from P60 (adult) Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre mice were arrested at the round spermatid stage, as evidenced by the lack of elongated spermatids in P60 testes (Fig 4C). Therefore, in contrast with the meiotic arrest phenotype observed in Mov10l1yama/yama testis, Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre males displayed post-meiotic round spermatid arrest, similar to that observed in Mov10l1fl/- Ngn3-Cre males (Fig 4C) [45]. The lack of complementation of the targeted Mov10l1 mutant (Mov10l1-) allele by the yama allele confirms that the phenotype-causing mutation is the detected missense mutation V229E in Mov10l1.

Fig 4. Round spermatid arrest in adult Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes.

(A) Images of 8-week-old testes. (B) Reduction of testis weight in 8-week-old Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre mice (mean ± s.d; n = 3 per genotype). *, P < 0.05. (C) Histological analysis of P21 and P60 Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre and P60 Mov10l1fl/- Ngn3-Cre testes. Mov10l1fl/+ testes serve as wild-type controls. Abbreviations: Pa, pachytene spermatocytes; RS, round spermatids; ES, elongated spermatids. Scale bar, 50 μm. (D) Depletion of pachytene piRNAs in 6-week-old Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes. Total RNAs were 32P-end-labelled and separated by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The experiment was done twice with the same result. 28S and 18S ribosomal RNAs serve as loading controls. (E) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of pachytene piRNA precursor transcripts in 8-week-old testes. Values (mean ± s.d.; triplicates) are the fold change in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testis normalized to levels in wild-type testis defined as 1. Pre-let7g, a miRNA precursor, serves as a control. *, P < 0.005; ns, non-significant (Student’s t-test).

MOV10L1 V229E mutation blocks the primary processing of pachytene piRNA precursors

Mov10l1fl/- Ngn3-Cre testis displays round spermatid arrest and lacks pachytene piRNAs [45]. To assess the production of pachytene piRNAs in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes, we isolated and radiolabeled total RNA from testes and found that Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes were devoid of pachytene piRNAs, which were expected to be ~30 nt (Fig 4D). Pachytene piRNAs are derived from long precursor transcripts from genomic clusters [8,10,56]. Long primary piRNA precursor transcripts are cleaved into intermediate RNAs and processed into mature piRNAs. The absence of pachytene piRNAs in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes could be due to the blockage of pachytene piRNA precursor processing, which requires MOV10L1 [45]. To test this possibility, we examined the level of precursors of three pachytene piRNAs: piR1, piR2 and piLR (Fig 4E). qRT-PCR analysis revealed that these three precursors accumulated to 2 to 5-fold higher levels in the mutant testes compared with the wild-type testes (Fig 4E). As expected, the abundance of miRNA precursor Pre-let7g remained constant (Fig 4E). These results demonstrate that the V229 residue of MOV10L1 is essential for the primary processing of piRNA precursor transcripts.

To evaluate whether the absence of pachytene piRNAs leads to de-repression of retrotransposons, such as LINE1 and IAP, in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre germ cells, we immunostained adult wild-type and Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testis sections with anti-LINE1 and anti-IAP antibodies. In comparison with the dramatic increase of retrotransposons in Mov10l1yama/yama and Mov10l1-/- testes, LINE1 and IAP were barely detected in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre adult testis (S3A Fig). Therefore, consistent with previous findings in Mov10l1fl/- Ngn3-Cre and other pachytene piRNA pathway mutants [27,45], pachytene piRNAs are not required for repression of LINE1 and IAP retrotransposons.

During the chromatin remodeling process in elongating spermatids, DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) are introduced into the germ cell genome by topoisomerase II beta (TOP2B) to resolve DNA supercoils [57]. The formation of DSBs in elongating spermatids triggers activation of phosphorylation of histone H2AX (γH2AX). Therefore, in wild-type testis, in addition to spermatocytes, γH2AX is present in germ cells that undergo chromatin reconfiguration: in elongating spermatids but not in round spermatids (S3B Fig). However, a dramatic increase of DNA damage visualized by γH2AX was observed in round spermatids from Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes (S3B Fig). This result was previously observed in Mov10l1fl/- Ngn3-Cre testes [45]. These findings confirm that pachytene piRNAs play a role in maintaining genome integrity in post-meiotic round spermatids.

Dissociation of MOV10L1 from piRNA pathway proteins in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes

We next evaluated the localization of piRNA pathway proteins, including MILI, MIWI and TDRD1 in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre and wild-type testes. In Mov10l1fl/- Ngn3-Cre spermatocytes, these proteins form a polar conglomeration along with mitochondria [45]. As expected, these three proteins were highly expressed in the cytoplasm of spermatocytes in wild-type testes. Strikingly, these proteins congregated to one pole in the cytoplasm of pachytene spermatocytes in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes (Fig 5A–5C), similar to Mov10l1fl/- Ngn3-Cre testes, revealing aberrant localization of the piRNA pathway components. However, MOV10L1V229E localized throughout the cytoplasm of spermatocytes and did not display polar aggregation (Fig 5D). In wild-type spermatocytes, piRNA pathway components localize to granules called nuage [58]. As expected, in spermatocytes from control testes, MILI and mitochondria colocalized and were distributed throughout the cytoplasm (S4 Fig). Mitochondria localized exclusively to polar aggregates in spermatocytes from Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes, showing that along with piRNA pathway proteins, the mitochondria are also abnormally clustered (S4 Fig).

Fig 5. Dissociation of MOV10L1V229E with MILI, MIWI, TDRD1, and PLD6 in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre mouse testes.

Polar congregation of piRNA pathway proteins MILI (A), MIWI (B), and TDRD1 (C) in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre spermatocytes from P21 and P60 testes. (D) Localization of MOV10L1 in Mov10l1fl/+ and Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes. Enlarged view of representative pachytene (Pa) spermatocytes (boxed) are shown in top right corners. Scale bars, 50 μm. (E-J) Co-immunoprecipitation analyses of MOV10L1 with MILI (E and F), MIWI (G), and TDRD1 (H) [69], and PLD6 (J). P21 testes were used for co-IP analyses in panels E, F, H, and J. P28 testes were used for co-IP analyses in G. (I) Western blot analysis of PLD6 in P14 and P21 Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre and control testes.

MOV10L1 interacts with MILI, MIWI, and TDRD1 [45]. Since these piRNA pathway proteins were still present in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes, we sought to address whether the associations between MOV10L1 and piRNA pathway proteins were affected in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes. MOV10L1 was abundant in MILI-immunoprecipitated complexes from wild-type testes but absent in MILI-containing complexes from Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes (Fig 5E). To confirm this result, we performed reciprocal immunoprecipitations and found that MILI was absent in MOV10L1-immunoprecipitated proteins from Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes (Fig 5F). Likewise, our co-immunoprecipitation assays revealed that MOV10L1 was sharply decreased in MIWI or TDRD1-immunoprecipitated proteins from Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes, in comparison with control testes (Fig 5G and 5H).

PLD6 is an endoribonuclease essential for the cleavage of piRNA precursor transcripts [32,33]. Western blot analyses showed that PLD6 was slightly reduced in P14 and P21 Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes (Fig 5I). To test the association of MOV10L1 and PLD6 in testes, we performed co-immunoprecipitation and found that they formed a complex in vivo in wild type (Fig 5J). Consistently, MOV10L1 and PLD6 are found in the same fractions from testis ribosome profiling experiments [59]. However, this association was abolished in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes (Fig 5J). These results demonstrate that the association of MOV10L1V229E with the piRNA pathway proteins is either abolished or severely reduced, which provides a molecular mechanism underlying the piRNA biogenesis defect.

The V229E substitution attenuates the MOV10L1-PLD6 interaction

To test whether the V229E mutation directly affects the interaction between MOV10L1 and the piRNA pathway proteins, we co-expressed these proteins in HEK293T cells. Wild-type MOV10L1 interacted with all Piwi proteins (MILI, MIWI, and MIWI2) in transfected cells (Fig 6A–6C). Strikingly, MOV10L1V229E was still associated with the Piwi proteins (Fig 6A–6C). MEIOB, a meiosis-specific ssDNA-binding protein required for meiotic recombination, served as a negative control [60,61]. As expected, MOV10L1 did not interact with MEIOB (Fig 6D). These results from co-transfection experiments in cultured cells were in stark contrast with the absent or reduced association of MOV10L1V229E with Piwi proteins in testes (Fig 5). It is possible that, in mutant testes, the piRNA biogenesis machinery is disrupted in a way that causes the piRNA pathway proteins to be segregated into different subcellular compartments, thus rendering them unable to interact.

Fig 6. The V229E substitution reduces the interaction between MOV10L1 and PLD6 in HEK293T cells.

(A-C) Co-immunoprecipitation analyses of MOV10L1 with MILI (A), MIWI (B), and MIWI2 (C). (D) No interaction was observed between MOV10L1 and MEIOB. MEIOB serves as a negative control. (E) Reduced interaction between PLD6 and MOV10L1-V229E. (F, G) Co-immunoprecipitation analyses of PLD6 with MOV10L1N (F), MOV10L1N-V229E (F) and MOV10L1C (G). Band quantification (A, B, C, and E): the band intensity in the 1st and 3rd lanes from left is set at 1.00 in both input and IP; the band intensity in 2nd and 4th lanes is normalized to that in 1st and 3rd lanes respectively. All co-IP experiments were performed twice. Western blotting was performed with anti-HA, anti-MYC, or anti-V5 antibodies. (H) Schematic diagram of the MOV10L1 full-length protein and its variants. The RNA helicase domain is shown. Asterisk denotes the V229E substitution. PLD6-binding: +, strong; +/-, reduced; -, no binding.

PLD6 plays a conserved role in piRNA biogenesis in Drosophila and mice [35,36,62]. Wild-type full-length MOV10L1 co-immunoprecipitated with PLD6 in HEK293T cells, however, the interaction of MOV10L1V229E with PLD6 was reduced (Fig 6E). To further investigate the MOV10L1-PLD6 interaction, MOV10L1 was divided into two halves: MOV10L1N (aa 1–708) and MOV10L1C (aa 709–1239) (Fig 6H). Co-transfection experiments in HEK293T cells showed that PLD6 was associated with MOV10L1N (Fig 6F), but not with MOV10L1C (Fig 6G). However, this interaction was absent between PLD6 and MOV10L1NV229E (Fig 6F). These results imply that the failure in piRNA biogenesis in Mov10l1 V229E mutant testes could be due to reduced interaction between MOV10L1 and PLD6 (Fig 7).

Fig 7. MOV10L1 V229 residue is critical for processing of piRNA precursors.

(A) A timeline of mouse spermatogenesis. MOV10L1 developmental expression pattern is shown along with two distinct piRNA populations. The point of spermatogenic arrest in each mouse mutant is indicated (X). The Ngn3-Cre expression start point is shown. Mov10l1-/- and Mov10l1fl/- Ngn3-Cre mice with deletion of the RNA helicase domain were reported previously and included for comparison [41,45]. (B) Working model for the essential role of the MOV10L1 V229 residue in the piRNA biogenesis. In wild-type germ cells, MOV10L1 C-terminal region contains the RNA helicase domain and binds to single-stranded piRNA precursors [42]. MOV10L1 interacts with Piwi proteins, TDRD1, and PLD6 to process piRNA precursors. This protein complex translocates on the piRNA precursor in the 5´ to 3´ direction [42,43]. PLD6, a mitochondrial outer membrane-associated endoribonuclease, cleaves the precursor transcript preferentially before RNA secondary structures such as G-quadruplexes to release the 5´ RNA fragment, which is bound by a Piwi protein and processed into a mature piRNA. In this process, the N-terminal half of MOV10L1 recruits PLD6 to the piRNA processing complex by interaction. In yama mutant spermatocytes, the V229E mutation disrupts the MOV10L1-PLD6 interaction, leading to a failure in the cleavage of piRNA precursors and lack of association of MOV10L1V229E with the mitochondrial membrane.

Discussion

The MOV10L1 C-terminal RNA helicase activity is essential for piRNA biogenesis (Figs 2A and 7A) [41,42,46]. Here, the identification of the mutation (V229E) in a phenotype-driven ENU mutagenesis screen has allowed us to probe the function of the MOV10L1 N-terminal region. We find that the V229 residue in the MOV10L1 N-terminal region is critical for piRNA biogenesis and spermatogenesis.

Mechanistically, the V229E substitution reduces the interaction between MOV10L1 and PLD6 (Fig 7B). MOV10L1 preferentially binds to RNA G-quadruplex both in vivo and in vitro [42,43]. Recent biochemical studies have shown that binding to G-quadruplex requires both the N- and C-termini of MOV10L1 [43]. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that the V229E substitution might affect G-quadruplex binding. The MOV10L1 C-terminal region alone does not interact with PLD6. Although MOV10L1N-V229E does not interact with PLD6, the MOV10L1-V229E (full-length) showed reduced interaction with PLD6, suggesting that the MOV10L1 C-terminal region contributes to this interaction but is not sufficient. In our working model (Fig 7B), MOV10L1 binds to piRNA precursors. The V229E substitution inhibits the recruitment of PLD6, resulting in a failure of piRNA precursor cleavage and thus a lack of mature piRNAs. As a consequence, piRNA precursor transcripts accumulate in the Mov10l1 mutant testis.

MOV10L1 interacts with all Piwi proteins [41]. Association of MILI and MIWI with MOV10L1V229E is either absent or dramatically reduced in the Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testis. However, when co-expressed in HEK293T cells, MOV10L1V229E still interacts with Piwi proteins. What accounts for this difference between in vivo (testis) and in vitro (HEK293T cells)? Normally, piRNA biogenesis factors localize to cytoplasmic granules called nuage or inter-mitochondrial cement [58]. We postulate that the piRNA biogenesis machinery has collapsed in the Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testis, due to defects in the very early steps of piRNA biogenesis (Fig 7B), and as a result, the piRNA pathway proteins are redistributed. One possible explanation is that MOV10L1V229E can still interact with Piwi proteins in vitro because they are overexpressed. Another possible but non-mutually exclusive explanation is that MOV10L1V229E is physically separated from other proteins such as Piwi and PLD6 in the mutant testes. The latter explanation is supported by the abnormal polar aggregation of MILI, MIWI, and TDRD1 in the cytoplasm of pachytene spermatocytes from the Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testis. It is further supported by the diffuse cytoplasmic distribution and the lack of polar aggregation of MOV10L1V229E in pachytene spermatocytes from the Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testis.

Here we report the unusual polar aggregation of piRNA pathway proteins away from their normal location in nuage in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testis. This was also observed previously in Mov10l1fl/- Ngn3-Cre testis [45], Pld6-/- testis [35], and TdrkhcKO testis [27]. Although the reason for polar aggregation of piRNA pathway proteins in mutant testes is unknown, it might result from perturbation of piRNA production. Proteins involved in piRNA biogenesis localize to nuage (also called inter-mitochondrial cement or germ cell granule) [58]. Nuages are membraneless electron-dense cytoplasmic condensates. It has been suggested that nuage in germ cells may form via liquid-liquid phase separation [63]. Notably, DDX4, an essential factor for piRNA biogenesis, undergoes phase separation both in vitro and in cells [64]. It is possible that disruption of piRNA production causes abnormal phase separation of evenly distributed multiple nuages, leading to fusion into one large polar aggregate per spermatocyte.

The abnormal polar aggregates described previously and those that form in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testis colocalized with mitochondria [27,35,45] (S4 Fig). Nuages are located closely to or between mitochondria, and both nuages and mitochondria are important for piRNA biogenesis [58,65]. While the piRNA pathway proteins such as Piwi and MOV10L1 mostly localize to nuage, notably, PLD6, PNLDC1, and TDRKH are mitochondrial outer membrane proteins [26,27,35–37]. TDRKH functions as a scaffold protein to recruit MIWI and PNLDC1 to mitochondria for 3′ trimming of piRNA intermediates [27]. Mitochondria-containing protein extracts are required for reconstitution of piRNA biogenesis in vitro, demonstrating that mitochondria play at least a structural role in piRNA biogenesis [65]. The importance of the interaction between MOV10L1, a component of nuage, with PLD6, which resides in mitochondria, for piRNA biogenesis provides another connection between nuage and mitochondria. It is possible that the reduced interaction between MOV10L1V229E and PLD6 causes or contributes to a failure in recruitment of MOV10L1 to mitochondria by PLD6, resulting in perturbation of piRNA biogenesis (Fig 7B).

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All experiments conformed to regulatory standards and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC protocol number 806616) of the University of Pennsylvania and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC).

Generation of the Mov10l1yama mutant

The Mov10l1yama allele was isolated in an N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis screen for mutants with autosomal recessive defects in meiosis (Fig 1). Mutagenesis and breeding for screening purposes were conducted at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC).

The yama mutation (T to A) creates a novel BseRI restriction site (S1 Fig). The wild-type and mutant alleles were assayed by primers ACACGACATTGTCAATGCTGTG and GTGGTATGATCTAGTGGAACCAGAA followed by BseRI restriction enzyme digestion at 37°C for 3 hours. Both alleles produce a 220-bp PCR product and only the mutant PCR product can be digested into 179-bp and 41-bp fragments by BseRI.

The Mov10l1+/- and Mov10l1fl/fl mice were previously generated (MMRRC stock number for Mov10l1fl/fl mice: 036983-UNC) [41]. The Ngn3-Cre mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Stock number: Neurog3-Cre, 006333) [55].

Histological and immunofluorescence analyses

For histological analysis, testes were fixed in Bouin’s solution at room temperature overnight, embedded with paraffin and sectioned. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. In terms of immunofluorescence analysis, testes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (in 1x PBS) for 6 hours at 4°C, dehydrated in 30% sucrose (in 1x PBS) overnight and sectioned. For surface nuclear spread analysis, testicular tubules were extracted in hypotonic treatment buffer (30 mM Tris, 50 mM Sucrose, 17 mM Trisodium Citrate Dihydrate, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF). Cells were suspended in 100 mM sucrose and were then spread on a slide which was soaked in paraformaldehyde solution containing Triton X-100.The sections were blocked with 10% goat serum at room temperature for 1 hour and then incubated with primary antibodies at 37°C for 3 hours. The sections were washed with 1xTBS three times and then incubated with a fluorescein secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories) at 37°C for 1 hour. After three washes, mounting medium with DAPI (H-1200, Vector Laboratories) was added to the sections. The primary and secondary antibodies used for immunofluorescence analyses were listed in S1 Table.

RNA extraction and detection of pachytene piRNAs

Total testis RNA was extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 1 μg RNA was dephosphorylated and radiolabeled as described previously [20].

Reverse transcription and quantitative real-time PCR

1 μg RNA was treated with DNase I and reverse transcribed to cDNA with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (ThermoFisher Scientific). The primers for real-time PCR were listed in S2 Table. Each sample was assayed in triplicates. Quantification was normalized to Actb using the ΔCt method.

Expression constructs

The MOV10L1, MILI, MIWI and MIWI2 expression constructs were previously described [41]. PLD6 expression plasmid was constructed by subcloning mouse PLD6 cDNA to pcDNA3 vector harboring a C-terminal V5 tag. MOV10L1-V229E mutation was generated by overlapping PCR [66] and subcloned into the pCI-neo vector harboring an N-terminal HA tag. MOV10L1 truncated plasmids were engineered by subcloning into pCI-neo vector. All the constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing on an ABI 3730 DNA analyzer.

Cell culture and transfections

HEK293T cells were maintained in DMEM/high glucose (Mediatech) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma) and penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNA transfections in HEK293T cells were carried out using a standard calcium phosphate method. Briefly, transfections were performed when HEK293T cells were 80% confluent. The transfection mixture (2 μg plasmid, 12.5 μl 2 M CaCl2, 85 μl ddH2O and 100 μl 2xHEPES, pH 7.15) was incubated at room temperature for 30 min before being added to one well of a 6-well plate in a dropwise manner. Cells were collected 24–36 hours after transfection for further analysis. For cycloheximide treatment experiment, 24 hours after transfection, the cells were treated with cycloheximide (20 μg/ml) for 24 hours to inhibit de novo protein synthesis. Cells were collected in 2xSDS PAGE buffer for immunoblotting analysis.

Co-immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting assays

1x107 cells were collected after transfection for in vitro co-immunoprecipitation and 2 pairs of P21 or P28 juvenile testes were used for in vivo co-immunoprecipitation. Cells or testes were lysed in 1 ml RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 140 mM NaCl, 1% Trion X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with 1mM PMSF. For immunoprecipitation (IP), 1.5% of the lysates were used as inputs. The remaining lysates were pre-cleared with 15 μl protein G Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for two hours, incubated with 1–2 μg primary antibodies at 4°C for 1 hour, and then incubated with 30 μl protein G Dynabeads overnight. The immunoprecipitated complexes were washed with the RIPA buffer four times and boiled in 30 μl 2× SDS-PAGE loading buffer for 10 min. 20 μl of supernatants were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes using iBlot (Invitrogen), and immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. The primary and secondary antibodies used for co-IP and western blot analyses were listed in S1 Table. Band quantification was performed with ImageJ (Version 1.51).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with Student’s t-test.

Supporting information

Exon 5 sequence is shown in red (Reference cDNA sequence: NCBI accession number XM_006521556). The mutation is highlighted in green in exon 5 (GTG229GAG ➔ V229E). BseRI site is underlined: GAGGAG(N)10. PCR genotyping primers: Forward primer is highlighted in yellow. Reverse primer is highlighted in magenta.

(DOCX)

Histology of testes from 4-month and 7-month-old males. Asterisks indicate tubules with Sertoli-cell-only phenotype or severe depletion of germ cells. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(TIF)

(A) Sections of testes from 6-week-old wild-type and Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre males were immunostained with anti-LINE1 and anti-IAP antibodies. Mov10l1-/- (knockout) testis serves as a positive control [41]. (B) Presence of γH2AX in round spermatids from 6-week-old Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes (right panels). Elongating spermatids in Mov10l1fl/+ (control) stage XI tubules are γH2AX-positive (left panels). Round spermatids in Mov10l1fl/+ (control) early stage (before IX) tubules are γH2AX-negative (middle panels) but round spermatids in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre testes (right panels) are γH2AX-positive. Abbreviations: Spg, spermatogonia; Spc, spermatocytes; RS, round spermatids; ES, elongating spermatids; Zyg, zygotene spermatocytes; Pa, pachytene spermatocytes; Dip, diplotene spermatocytes. Scale bars, 25 μm.

(TIF)

Testis sections from P60 Mov10l1fl/+ (control) and Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre mice were immunostained with anti-MILI antibody and OXPHOS. OXPHOS is a cocktail of five monoclonal antibodies against mitochondrial proteins (S2 Table). MILI and mitochondria colocalize but are distributed throughout the cytoplasm in Mov10l1fl/+ pachytene spermatocytes. However, only polar aggregates in Mov10l1fl/yama Ngn3-Cre pachytene spermatocytes are OXOPHOS-positive. Representative polar aggregates are indicated by arrows. Inset shows an enlarged view of the boxed spermatocyte. Scale bar, 25 μm.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Ramesh S. Pillai for LINE1 ORF1 antibody, Bryan Cullen for anti-IAP antibody, Shinichiro Chuma for TDRD1 antibody, Prabhakara Reddi for anti-SP10 (ACRV1) antibody, Joseph Baur and Narayan Avadhani for mitochondrial protein antibodies. We thank Wang lab members (Jessica Chotiner, Rui Guo, Rong Liu, and Fang Yang) for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Keeney lab members Luis Torres and Jacquelyn Song for assistance with genotyping and mouse husbandry. We thank the Genetic Analysis Facility (Centre for Applied Genomics, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada) for microarray analysis. For whole-exome sequencing, we thank Nathalie Lailler at the MSKCC Integrated Genomics Operation.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

Work in the Wang lab was supported by NIH/NICHD grants R01 HD069592 and P50 HD068157 (PJW). Work in the Keeney lab was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (SK). DJ was supported in part by a fellowship from the Human Frontier Science Program. Core facilities at MSK are supported by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Goodier JL, Kazazian HH. Retrotransposons revisited: The restraint and rehabilitation of parasites. Cell. 2008;135:23–35. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang CR, Burns KH, Boeke JD. Active transposition in genomes. Annu Rev Genet. 2012;46:651–675. 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozata DM, Gainetdinov I, Zoch A, O’Carroll D, Zamore PD. PIWI-interacting RNAs: Small RNAs with big functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20:89–108. 10.1038/s41576-018-0073-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, Watanabe T, Gotoh K, Totoki Y, Toyoda A, Ikawa M, et al. DNA methylation of retrotransposon genes is regulated by piwi family members MILI and MIWI2 in murine fetal testes. Genes Dev. 2008;22:908–917. 10.1101/gad.1640708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aravin AA, Sachidanandam R, Bourc’his D, Schaefer C, Pezic D, Toth KF, et al. A piRNA pathway primed by individual transposons is linked to de novo DNA methylation in mice. Mol Cell. 2008;31:785–799. 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Fazio S, Bartonicek N, Di Giacomo M, Abreu-Goodger C, Sankar A, Funaya C, et al. The endonuclease activity of mili fuels piRNA amplification that silences LINE1 elements. Nature. 2011;480:259–263. 10.1038/nature10547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Z, Chen KM, Pandey RR, Homolka D, Reuter M, Janeiro BK, et al. PIWI slicing and EXD1 drive biogenesis of nuclear piRNAs from cytosolic targets of the mouse piRNA pathway. Mol Cell. 2016;61:138–152. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aravin A, Gaidatzis D, Pfeffer S, Lagos-Quintana M, Landgraf P, Iovino N, et al. A novel class of small RNAs bind to MILI protein in mouse testes. Nature. 2006;442:203–207. 10.1038/nature04916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girard A, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ, Carmell MA. A germline-specific class of small RNAs binds mammalian piwi proteins. Nature. 2006;442:199–202. 10.1038/nature04917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grivna ST, Beyret E, Wang Z, Lin H. A novel class of small RNAs in mouse spermatogenic cells. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1709–1714. 10.1101/gad.1434406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gou LT, Dai P, Yang JH, Xue Y, Hu YP, Zhou Y, et al. Pachytene piRNAs instruct massive mRNA elimination during late spermiogenesis. Cell Res. 2014;24:680–700. 10.1038/cr.2014.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goh WS, Falciatori I, Tam OH, Burgess R, Meikar O, Kotaja N, et al. piRNA-directed cleavage of meiotic transcripts regulates spermatogenesis. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1032–1044. 10.1101/gad.260455.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang P, Kang JY, Gou LT, Wang J, Xue Y, Skogerboe G, et al. MIWI and piRNA-mediated cleavage of messenger RNAs in mouse testes. Cell Res. 2015;25:193–207. 10.1038/cr.2015.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe T, Cheng EC, Zhong M, Lin H. Retrotransposons and pseudogenes regulate mRNAs and lncRNAs via the piRNA pathway in the germline. Genome Res. 2015;25:368–380. 10.1101/gr.180802.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reuter M, Berninger P, Chuma S, Shah H, Hosokawa M, Funaya C, et al. Miwi catalysis is required for piRNA amplification-independent LINE1 transposon silencing. Nature. 2011;480:264–267. 10.1038/nature10672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vourekas A, Zheng Q, Alexiou P, Maragkakis M, Kirino Y, Gregory BD, et al. Mili and miwi target RNA repertoire reveals piRNA biogenesis and function of miwi in spermiogenesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:773–781. 10.1038/nsmb.2347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai P, Wang X, Gou LT, Li ZT, Wen Z, Chen ZG, et al. A translation-activating function of MIWI/piRNA during mouse spermiogenesis. Cell. 2019;179:1566–1581. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chuma S, Hosokawa M, Kitamura K, Kasai S, Fujioka M, Hiyoshi M, et al. Tdrd1/Mtr-1, a tudor-related gene, is essential for male germ-cell differentiation and nuage/germinal granule formation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15894–15899. 10.1073/pnas.0601878103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Saxe JP, Tanaka T, Chuma S, Lin H. Mili interacts with tudor domain-containing protein 1 in regulating spermatogenesis. Curr Biol. 2009;19:640–644. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reuter M, Chuma S, Tanaka T, Franz T, Stark A, Pillai RS. Loss of the mili-interacting tudor domain-containing protein-1 activates transposons and alters the mili-associated small RNA profile. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:639–646. 10.1038/nsmb.1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun YH, Jiang F, Li XZ. Disruption of Tdrd5 decouples the stepwise processing of long precursor transcripts during pachytene PIWI-interacting RNA biogenesis. Biol Reprod. 2018;99:684–685. 10.1093/biolre/ioy110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding D, Liu J, Midic U, Wu Y, Dong K, Melnick A, et al. TDRD5 binds piRNA precursors and selectively enhances pachytene piRNA processing in mice. Nat Commun. 2018;9:127. 10.1038/s41467-017-02622-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shoji M, Tanaka T, Hosokawa M, Reuter M, Stark A, Kato Y, et al. The TDRD9-MIWI2 complex is essential for piRNA-mediated retrotransposon silencing in the mouse male germline. Dev Cell. 2009;17:775–787. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wenda JM, Homolka D, Yang Z, Spinelli P, Sachidanandam R, Pandey RR, et al. Distinct roles of RNA helicases MVH and TDRD9 in PIWI slicing-triggered mammalian piRNA biogenesis and function. Dev Cell. 2017;41:623–637.e9. 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandey RR, Tokuzawa Y, Yang Z, Hayashi E, Ichisaka T, Kajita S, et al. Tudor domain containing 12 (TDRD12) is essential for secondary PIWI interacting RNA biogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:16492–16497. 10.1073/pnas.1316316110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saxe JP, Chen M, Zhao H, Lin H. Tdrkh is essential for spermatogenesis and participates in primary piRNA biogenesis in the germline. Embo j. 2013;32:1869–1885. 10.1038/emboj.2013.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding D, Liu J, Dong K, Melnick AF, Latham KE, Chen C. Mitochondrial membrane-based initial separation of MIWI and MILI functions during pachytene piRNA biogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:2594–2608. 10.1093/nar/gky1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirino Y, Kim N, de Planell-Saguer M, Khandros E, Chiorean S, Klein PS, et al. Arginine methylation of piwi proteins catalysed by dPRMT5 is required for Ago3 and aub stability. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:652–658. 10.1038/ncb1872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen C, Jin J, James DA, Adams-Cioaba MA, Park JG, Guo Y, et al. Mouse piwi interactome identifies binding mechanism of tdrkh tudor domain to arginine methylated miwi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20336–20341. 10.1073/pnas.0911640106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirino Y, Vourekas A, Sayed N, de Lima Alves F, Thomson T, Lasko P, et al. Arginine methylation of aubergine mediates tudor binding and germ plasm localization. RNA. 2010;16:70–78. 10.1261/rna.1869710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vagin VV, Wohlschlegel J, Qu J, Jonsson Z, Huang X, Chuma S, et al. Proteomic analysis of murine piwi proteins reveals a role for arginine methylation in specifying interaction with tudor family members. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1749–1762. 10.1101/gad.1814809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ipsaro JJ, Haase AD, Knott SR, Joshua-Tor L, Hannon GJ. The structural biochemistry of zucchini implicates it as a nuclease in piRNA biogenesis. Nature. 2012;491:279–283. 10.1038/nature11502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishimasu H, Ishizu H, Saito K, Fukuhara S, Kamatani MK, Bonnefond L, et al. Structure and function of zucchini endoribonuclease in piRNA biogenesis. Nature. 2012;491:284–287. 10.1038/nature11509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voigt F, Reuter M, Kasaruho A, Schulz EC, Pillai RS, Barabas O. Crystal structure of the primary piRNA biogenesis factor zucchini reveals similarity to the bacterial PLD endonuclease nuc. RNA. 2012;18:2128–2134. 10.1261/rna.034967.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe T, Chuma S, Yamamoto Y, Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, Totoki Y, Toyoda A, et al. MITOPLD is a mitochondrial protein essential for nuage formation and piRNA biogenesis in the mouse germline. Dev Cell. 2011;20:364–375. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang H, Gao Q, Peng X, Choi SY, Sarma K, Ren H, et al. piRNA-associated germline nuage formation and spermatogenesis require MitoPLD profusogenic mitochondrial-surface lipid signaling. Dev Cell. 2011;20:376–387. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Izumi N, Shoji K, Sakaguchi Y, Honda S, Kirino Y, Suzuki T, et al. Identification and functional analysis of the pre-piRNA 3’ trimmer in silkworms. Cell. 2016;164:962–973. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding D, Liu J, Dong K, Midic U, Hess RA, Xie H, et al. PNLDC1 is essential for piRNA 3’ end trimming and transposon silencing during spermatogenesis in mice. Nat Commun. 2017;8:819. 10.1038/s41467-017-00854-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Guo R, Cui Y, Zhu Z, Zhang Y, Wu H, et al. An essential role for PNLDC1 in piRNA 3’ end trimming and male fertility in mice. Cell Res. 2017;27:1392–1396. 10.1038/cr.2017.125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishimura T, Nagamori I, Nakatani T, Izumi N, Tomari Y, Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, et al. PNLDC1, mouse pre-piRNA trimmer, is required for meiotic and post-meiotic male germ cell development. EMBO Rep. 2018;19:e44957. 10.15252/embr.201744957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng K, Xiol J, Reuter M, Eckardt S, Leu NA, McLaughlin KJ, et al. Mouse MOV10L1 associates with piwi proteins and is an essential component of the piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA) pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11841–11846. 10.1073/pnas.1003953107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vourekas A, Zheng K, Fu Q, Maragkakis M, Alexiou P, Ma J, et al. The RNA helicase MOV10L1 binds piRNA precursors to initiate piRNA processing. Genes Dev. 2015;29:617–629. 10.1101/gad.254631.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X, Yu L, Ye S, Xie J, Huang X, Zheng K, et al. MOV10L1 binds RNA G-quadruplex in a structure-specific manner and resolves it more efficiently than MOV10. iScience. 2019;17:36–48. 10.1016/j.isci.2019.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frost RJ, Hamra FK, Richardson JA, Qi X, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. MOV10L1 is necessary for protection of spermatocytes against retrotransposons by piwi-interacting RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11847–11852. 10.1073/pnas.1007158107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng K, Wang PJ. Blockade of pachytene piRNA biogenesis reveals a novel requirement for maintaining post-meiotic germline genome integrity. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003038. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu Q, Pandey RR, Leu NA, Pillai RS, Wang PJ. Mutations in the MOV10L1 ATP hydrolysis motif cause piRNA biogenesis failure and male sterility in mice. Biol Reprod. 2016;95:103. 10.1095/biolreprod.116.142430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jain D, Meydan C, Lange J, Claeys Bouuaert C, Lailler N, Mason CE, et al. Rahu is a mutant allele of Dnmt3c, encoding a DNA methyltransferase homolog required for meiosis and transposon repression in the mouse male germline. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006964. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jain D, Puno MR, Meydan C, Lailler N, Mason CE, Lima CD, et al. Ketu mutant mice uncover an essential meiotic function for the ancient RNA helicase YTHDC2. Elife. 2018;7:e30919. 10.7554/eLife.30919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petrillo C, Barroca V, Ribeiro J, Lailler N, Livera G, Keeney S, et al. Shani mutation in mouse affects splicing of Spata22 and leads to impaired meiotic recombination. Chromosoma. 2020;129:161–179. 10.1007/s00412-020-00735-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bellve AR, Cavicchia JC, Millette CF, O’Brien DA, Bhatnagar YM, Dym M. Spermatogenic cells of the prepuberal mouse. isolation and morphological characterization. J Cell Biol. 1977;74:68–85. 10.1083/jcb.74.1.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang F, Wang PJ. The mammalian synaptonemal complex: A scaffold and beyond. Genome Dyn. 2009;5:69–80. 10.1159/000166620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Di Giacomo M, Comazzetto S, Saini H, De Fazio S, Carrieri C, Morgan M, et al. Multiple epigenetic mechanisms and the piRNA pathway enforce LINE1 silencing during adult spermatogenesis. Mol Cell. 2013;50:601–608. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang F, Lan Y, Pandey RR, Homolka D, Berger SL, Pillai RS, et al. TEX15 associates with MILI and silences transposable elements in male germ cells. Genes Dev. 2020;34:745–750. 10.1101/gad.335489.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang F, Wang PJ. Multiple LINEs of retrotransposon silencing mechanisms in the mammalian germline. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;59:118–125. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schonhoff SE, Giel-Moloney M, Leiter AB. Neurogenin 3-expressing progenitor cells in the gastrointestinal tract differentiate into both endocrine and non-endocrine cell types. Dev Biol. 2004;270:443–454. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li XZ, Roy CK, Dong X, Bolcun-Filas E, Wang J, Han BW, et al. An ancient transcription factor initiates the burst of piRNA production during early meiosis in mouse testes. Mol Cell. 2013;50:67–81. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leduc F, Maquennehan V, Nkoma GB, Boissonneault G. DNA damage response during chromatin remodeling in elongating spermatids of mice. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:324–332. 10.1095/biolreprod.107.064162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pillai RS, Chuma S. piRNAs and their involvement in male germline development in mice. Dev Growth Differ. 2012;54:78–92. 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2011.01320.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun YH, Zhu J, Xie LH, Li Z, Meduri R, Zhu X, et al. Ribosomes guide pachytene piRNA formation on long intergenic piRNA precursors. Nat Cell Biol. 2020;22:200–212. 10.1038/s41556-019-0457-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luo M, Yang F, Leu NA, Landaiche J, Handel MA, Benavente R, et al. MEIOB exhibits single-stranded DNA-binding and exonuclease activities and is essential for meiotic recombination. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2788. 10.1038/ncomms3788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Souquet B, Abby E, Herve R, Finsterbusch F, Tourpin S, Le Bouffant R, et al. MEIOB targets single-strand DNA and is necessary for meiotic recombination. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003784. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pane A, Wehr K, Schupbach T. Zucchini and squash encode two putative nucleases required for rasiRNA production in the drosophila germline. Dev Cell. 2007;12:851–862. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dodson AE, Kennedy S. Phase separation in germ cells and development. Dev Cell. 2020;55:4–17. 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nott TJ, Petsalaki E, Farber P, Jervis D, Fussner E, Plochowietz A, et al. Phase transition of a disordered nuage protein generates environmentally responsive membraneless organelles. Mol Cell. 2015;57:936–947. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Izumi N, Shoji K, Suzuki Y, Katsuma S, Tomari Y. Zucchini consensus motifs determine the mechanism of pre-piRNA production. Nature. 2020;578:311–316. 10.1038/s41586-020-1966-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang PJ, Page DC. Functional substitution for TAFII250 by a retroposed homolog that is expressed in human spermatogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2341–2346. 10.1093/hmg/11.19.2341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reddi PP, Naaby-Hansen S, Aguolnik I, Tsai JY, Silver LM, Flickinger CJ, et al. Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid cloning and characterization of mSP-10: The mouse homologue of human acrosomal protein SP-10. Biol Reprod. 1995;53:873–881. 10.1095/biolreprod53.4.873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bogerd HP, Wiegand HL, Doehle BP, Lueders KK, Cullen BR. APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B are potent inhibitors of LTR-retrotransposon function in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:89–95. 10.1093/nar/gkj416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chuma S, Hiyoshi M, Yamamoto A, Hosokawa M, Takamune K, Nakatsuji N. Mouse tudor repeat-1 (MTR-1) is a novel component of chromatoid bodies/nuages in male germ cells and forms a complex with snRNPs. Mech Dev. 2003;120:979–990. 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00181-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]