Abstract

Introduction:

Sexual minority (SM; e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual) youth are disproportionately more likely to use tobacco than non-SM youth, yet there exist several critical gaps in knowledge. This study assessed (a) the timing of SM tobacco use disparities (e.g., during adolescence or early adulthood), (b) whether disparities generalize across different tobacco products, and (c) whether disparities differ by sex.

Methods:

Data were from a 6-year prospective cohort of diverse high school students from Southern California who were followed into early adulthood (9 waves, 2013-2019). SM (vs. non-SM) differences in past 6-month use were assessed for: any tobacco products, cigarettes, e-cigarettes, other products (e.g., hookah), and multiple products. Disparities were modeled longitudinally across adolescence (high school) and the transition to early adulthood (end of high school to post-high school). Differences were tested by sex.

Results:

Among females, SM disparities were evident for all outcomes during both adolescence and early adulthood; no differences were observed among males. For example, SM (vs. non-SM) females had higher odds of cigarette (aOR=4.4 [3.0-6.5]) and e-cigarette (aOR=1.7 [1.2-2.4]) use, averaged across adolescence. The timing of disparities varied by product. For example, cigarette use disparities emerged prior to high school and persisted through adolescence and young adulthood, while e-cigarette use disparities were present in early adolescence and young adulthood only.

Conclusions:

Young SM females are at especially high risk for tobacco use, across various tobacco products, throughout adolescence and young adulthood. Interventions must consider differences in the timing of disparities by product type.

INTRODUCTION

There exist considerable disparities in tobacco product use between sexual minority (SM; e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer) and non-SM populations, with SM individuals being disproportionately more likely than non-SM individuals to report use of, and dependence on, tobacco products (American Lung Association, 2017; Lee et al., 2009). For instance, in a recent U.S. national sample of adults, approximately 35% of both lesbian females and gay males reported past-year cigarette smoking, compared to 20% and 26% of heterosexual females and males, respectively (McCabe et al., 2018). These disparities are long-standing and they are driven by a number of factors, including a long history of targeting marketing to SM populations by tobacco companies (Dilley et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2008), the historical significance of bars and other places where tobacco use is common as safe places for SM people to socialize (Blosnich et al., 2013), and use of tobacco to cope with social stressors such as discrimination (Krueger et al., 2020). However, several critical gaps in knowledge remain, limiting the degree to which SM tobacco use disparities can effectively be reduced.

The bulk of SM tobacco use research has focused on documenting disparities in cigarette use (Azagba et al., 2014; CDC, 2018b; Corliss et al., 2014; Hoffman et al., 2018; Watson et al., 2018), yet use of cigarettes has declined considerably over the past two decades in the United States (Johnston et al., 2019). While cigarette smoking remains an important public health concern, the landscape of commercially available tobacco products has changed markedly in recent years with the introduction and rapid increase in availability and use of e-cigarettes (e.g., JUUL) (CDC, 2020). Emerging evidence suggests SM populations use e-cigarettes at higher rates than non-SM populations (Dai, 2017; Hoffman et al., 2018; Wheldon et al., 2018). Further, poly-tobacco use refers to the use of multiple tobacco products (e.g., both cigarettes and e-cigarettes). Given higher rates of both cigarette and e-cigarette use among SM populations, it is possible SMs also use multiple products at higher rates than non-SMs. To our knowledge, no prior studies have assessed this question, though prior research has shown differences in poly-tobacco use among SM subgroups, with bisexual female adults reporting higher odds of poly-tobacco use than gay male adults (Delahanty et al., 2019). Thus, while tobacco use disparities are well-documented, they are not well-characterized. In order to adequately address SM tobacco use disparities, data on the specific products used by SM individuals, and patterns of use among SM and non-SM individuals, are needed.

Further, SM tobacco use disparities often emerge during adolescence (Marshal et al., 2008; Marshal et al., 2009), and earlier tobacco use initiation has been linked to higher risk for nicotine dependence in adulthood (Schuler and Collins, 2019; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). It is therefore vital to understand when disparities in SM and non-SM tobacco products first emerge; such information will help practitioners and policymakers to identify effective solutions for reducing tobacco product initiation among a high-risk population. However, the majority of related research – particularly with regard to use non-cigarette tobacco products – has been conducted using cross-sectional samples. As such, critical gaps remain related to when (e.g., early adolescence vs. later adolescence) these disparities emerge, for which products (e.g., cigarettes vs. e-cigarettes), and whether they persist, dissipate, or widen as youth transition to adulthood (Schuler and Collins, 2019).1 To effectively address SM disparities in tobacco use across the life course, it is important to identify critical periods for the onset of disparities among youth, for a variety of products.

Finally, there exist marked sex differences in tobacco product use among youth, with males generally using tobacco at higher rates than females among youth in the general population (Harrell et al., 1998; World Health Organization, 2007) (though it should be noted that tobacco use among young females is of increasing public health concern (CDC, 2018a)). Emerging research has shown sex differences in tobacco use within the SM population as well; however, this trend is often “flipped,” with SM females commonly using tobacco at higher rates than SM males (Austin et al., 2004; Dai, 2017). This sex difference is not well-understood, but it is important to compare females to males in terms of tobacco product use – both within SM populations and across SM and non-SM populations. Failure to do so may result in disparities being underestimated and ineffective policies being implemented that do not address those most at risk.

Current study

To address these research gaps, the current study uses data from a 6-year prospective cohort of youth and young adults in order to: (1) compare SM (versus non-SM) differences in past 6-month use of: any tobacco products, cigarettes, e-cigarettes, other products (e.g., cigars, hookah), and multiple products; (2) compare differences in the timing of the emergence of disparities across each of the outcomes; and (3) assess whether SM tobacco use disparities vary by sex.

METHODS

Study Design

Data were from a prospective cohort study of substance use among high school students in Southern California. The cohort was recruited during fall semester, 2013 from 10 high schools in Los Angeles County when students were in 9th grade (first year of high school, mean age: 14.1; N=3,396) and were subsequently followed bi-annually (each semester, approximately every 6 months) through the completion of high school in 2017 (waves 1-8). At each wave, surveys were administered in class via paper and pencil. Students who were not present in class instead completed surveys by telephone or Internet. The cohort had a total retention rate of 92.8% from wave 1 to wave 8. Respondents were surveyed again in January-September 2019 after graduation from high school via Internet (wave 9, mean age: 19.8; N=2,548; 81.3% retention from wave 8 to wave 9). Respondents who completed a wave 9 survey, and who had complete demographic information were eligible for the current study. The final analytic sample was 2,323 (see consort diagram, Figure S1).

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Southern California. Parents provided written or verbal informed consent, and students provided assent prior to data collection.

Study Variables

Tobacco product use. Five outcomes were assessed at each wave. Respondents were asked if they had used any of the following in the past 6 months (yes/no): any tobacco products, cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and all other tobacco products (inclusive of hookah, cigars, and cigarillos). Additionally, a three-level outcome assessed poly-tobacco product use at each wave (use of 0, 1, or 2+ different products).

Sexual minority status was assessed at the final wave (wave 9) using three survey items, each capturing a different component of sexual orientation: identity, attraction, and behavior. For identity, respondents were asked “do you consider yourself to be:” (single choice: asexual, bisexual, gay, straight, lesbian, pansexual, queer, questioning or unsure, another identity not listed here, prefer not to disclose). Those selecting “asexual” or “prefer not to disclose” were marked as missing for sexual identity. For sexual attraction, respondents were asked, “people are different in their sexual attraction to other people. Which best describes your feelings?” (Likert scale from only attracted to members of the same sex – only attracted to members of the opposite sex, attracted to all genders, not attracted to anyone, not sure, prefer not to disclose). Those selecting “not attracted to anyone,” “not sure,” or “prefer not to disclose” were marked as missing for attraction. For sexual behavior, respondents were asked “(“in the past year, who did you have sex with?” (single choice: males, females, transgender males, transgender females, gender variant/non-binary, additional gender category, have not had sex, prefer not to disclose). Those selecting “have not had sex” or “prefer not to disclose” were marked as missing for sexual behavior. For the present analyses, respondents were coded as SM if they reported a non-straight sexual identity (i.e., bisexual, gay, lesbian, pansexual, queer, questioning or unsure), reported being attracted to members of the same sex or all genders, and/or reported having engaged sexual activity with members or the same sex, transgender, or non-binary partners. Respondents were coded as non-SM if they identified as straight, reported exclusively opposite-sex attractions, and reported no same-sex behavior.

Covariates. Several sociodemographic characteristics, assessed at baseline (wave 1), were included as covariates. Sex was assessed with the question, “what is your sex?” (female, male). Age was assessed in years (continuous). Race/ethnicity was assessed using the question “please choose one term that best describes you,” (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White, Multiracial, Other), which was collapsed into a 6-level variable (Hispanic, Asian, White, Black, Other, Multiracial). Parental education was also assessed for each parent (“what is the highest grade completed by your [mother/father]?”), and a 4-level variable (less than high school, high school, college, advanced degree) was created for the parent with the highest level of education.

Data Analysis

Sociodemographic characteristics were first calculated, separately by sex. Then, we estimated the prevalence of each tobacco use outcome, averaged across adolescence (waves 1-8) and the transition to young adulthood (waves 8-9), separately by time period and SM status. Finally, we used a series of mixed effect logistic regression models to estimate the longitudinal differences between SM and non-SM respondents for each outcome, adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, parental education and random effects by wave (controlling for multiple observations per respondent) and school (controlling for nesting of respondents by school). All models were sex-stratified and were estimated separately across the two study periods.

To assess whether relative differences in tobacco product use varied on the basis of sex, each adjusted model was repeated in a pooled sample including both males and females and included a multiplicative interaction term (SM status*sex); significance of the interaction was used to determine whether estimates differed by sex. Similar models were used to evaluate whether estimates differed by wave, by including a SM*wave interaction term. All analyses were conducted using Stata SE version 15. For all analyses, Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted p values were calculated to adjust for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics

For detailed sociodemographic comparisons, refer to Supplemental Table S1. Compared to males (11.2%), a larger proportion of female respondents were sexual minorities (21.1%; p<0.001). There were also small, but significant age differences, with males (mean: 14.1, SD: 0.01) being older than females (mean: 14.0, SD: 0.1; p=0.005). There were no differences by race/ethnicity (p=0.108) or parental education (p=0.526).

SM Disparities in Tobacco Product Use Across Adolescence

Table 1 presents differences in tobacco product use by SM status across adolescence, separately by sex. Among females, SM respondents had higher prevalence rates of each tobacco use outcome across waves 1-8 (difference range: 3.4-8.6%). Unadjusted and adjusted mixed effects logistic regression models also estimated the association between SM status and each tobacco use outcome, across adolescence. In adjusted models, SM females had higher odds of using each tobacco product, compared to non-SM females averaged across the entire period (any: aOR=2.8 [1.9, 3.9]; cigarettes: aOR=4.4 [3.0, 6.5]; e-cigarettes: aOR=1.7 [1.2, 2.4]; other: aOR=1.8 [1.3, 2.6]; poly [1 vs. 0 products]: aOR=1.9 [1.3, 2.7]; poly [2+ vs. 0 products]: aOR=2.8 [2.0, 4.1]).

Table 1.

Associations between Sexual Minority Status and Tobacco Product Use During Adolescence (W1-W8)

| Females | Males | Females vs. Males | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Prevalence | Difference in Prevalence | Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model | Absolute Prevalence | Difference in Prevalence | Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model | ||

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | |

| Any Tobacco Use | 0.014 | ||||||||

| Non-Sexual Minority | 11.9 (11.2, 12.6) | Ref | Ref | 14.1 (13.3, 14.9) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Sexual Minority | 20.5 (18.8, 22.2) | 8.6 (6.7, 10.4) | 2.6 (1.8, 3.7) | 2.8 (1.9, 3.9) | 12.9 (10.7, 15.6) | −1.2 (−3.7, 1.4) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.6) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.6) | |

| Cigarettes | 0.011 | ||||||||

| Non-Sexual Minority | 4.8 (4.4, 5.3) | Ref | Ref | 7.5 (6.9, 8.2) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Sexual Minority | 12.7 (11.3, 14.2) | 7.9 (6.4, 9.4) | 4.4 (3.0, 6.4) | 4.4 (3.0, 6.5) | 9.1 (7.2, 11.4) | 1.6 (−0.6, 0.4) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.5) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.6) | |

| E-Cigarettes | 0.026 | ||||||||

| Non-Sexual Minority | 12.6 (11.9, 13.3) | Ref | Ref | 15.9 (15.1, 16.8) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Sexual Minority | 17.6 (16.0, 19.3) | 5.0 (3.2, 6.8) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.4) | 14.0 (11.6, 16.7) | −2.0 (−4.6, 0.7) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.3) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.2) | |

| Other Tobacco Products | 0.082 | ||||||||

| Non-Sexual Minority | 9.4 (8.8, 10.0) | Ref | Ref | 10.4 (9.7, 11.2) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Sexual Minority | 13.3 (11.9, 14.8) | 3.9 (2.3, 5.4) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.5) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.6) | 8.7 (6.8, 10.9) | −1.8 (−3.9, 0.4) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.3) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.4) | |

| Poly Tobacco Use | 0.020 | ||||||||

| Number of Products (ref = 0) | |||||||||

| 1 Product | |||||||||

| Non-Sexual Minority | 11.9 (11.3, 12.6) | Ref | Ref | 12.6 (11.8, 13.4) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Sexual Minority | 15.3 (13.8, 16.9) | 3.4 (1.7, 5.1) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.6) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.7) | 11.4 (9.3, 13.9) | −1.2 (−3.6, 1.2) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.5) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.4) | |

| 2+ Products | |||||||||

| Non-Sexual Minority | 6.7 (6.2, 7.2) | Ref | Ref | 9.2 (8.6, 9.9) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Sexual Minority | 12.4 (11.1, 13.9) | 5.7 (4.2, 7.2) | 2.7 (1.9, 3.8) | 2.8 (2.0, 4.1) | 8.4 (6.6, 10.6) | −0.8 (−3.0, 1.3) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.5) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.5) | |

Note. Adjusted models controlled for wave, school, race/ethnicity, age, parental education. Difference between females and males were tested between adjusted models using likelihood ratio tests. Though there were significant direct effects of wave on all outcomes, there were no significant sexual minority*wave interactions, for either females or males. Boldface indicates statistical significance. All significance tests were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction method

Among males, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of tobacco product use for any of the outcomes. Similarly, no significant differences were found between SM and non-SM males, in either unadjusted or adjusted models, for any of the outcomes (any: aOR=0.9 [0.5, 1.6]; cigarettes: aOR=1.3 [0.7, 2.6]; e-cigarettes: aOR=0.7 [0.4, 1.2]; other: aOR=0.7 [0.4, 1.2]; poly [1 vs. 0 products]: aOR=0.8 [0.4, 1.4]; poly [2+ vs. 0 products]: aOR=0.8 [0.4, 1.5]). For all outcomes except other tobacco products, the adjusted models estimating the associations between SM status and tobacco use differed significantly between females and males (p<0.008 for all likelihood ratio tests). However, for all models the sexual minority status*wave interaction was not significant, signifying that the magnitudes of the disparities did not differ significantly over time, relative to baseline (p>0.05 for all outcomes, data not shown).

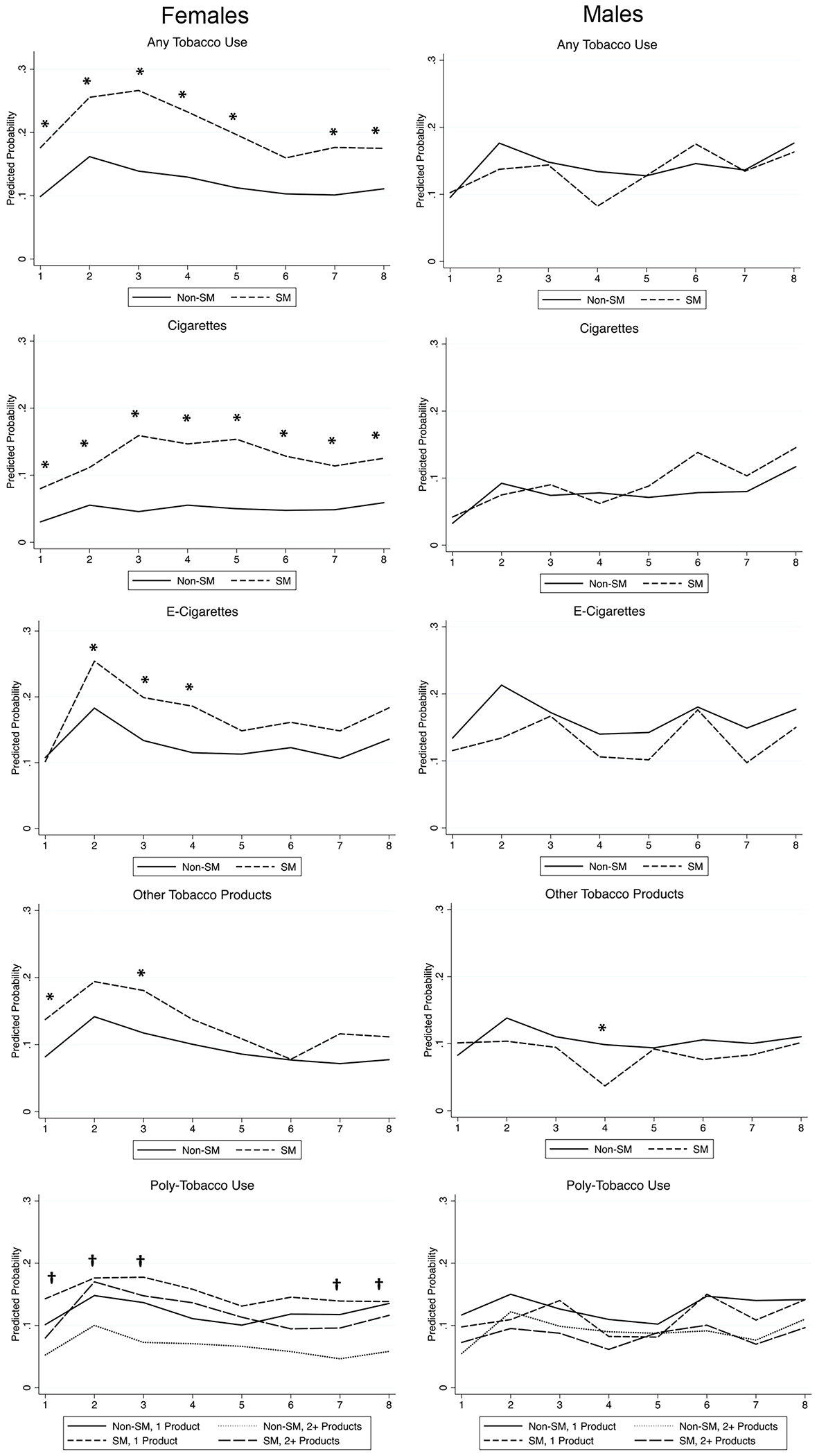

Figure 1 shows the predicted probability of each tobacco use outcome across adolescence (waves 1-8), separately by SM status and sex, controlling for covariates. For any tobacco product use except wave 6, SM females reported higher use than non-SM females at each wave of the study (p<0.05 for all pairwise comparisons). Similarly, SM females reported using cigarettes at higher rates than non-SM females across all study waves (all p<0.05). SM females and non-SM females used e-cigarettes at similar rates at wave 1, but a disparity emerged at waves 2 (1st year of high school, 2nd semester), and persisted through wave 4 (2nd year of high school, second semester; all p<0.05). However, this disparity lost significance across waves 5-8, (all p>0.05). There were also disparities for other tobacco product use between SM and non-SM females early in high school (waves 1 and 3), and for use of multiple products both in early and later high school (waves 1-3, 7-8; all p<0.05).

Figure 1. SM Disparities in Tobacco Product Use Across Adolescence, Separately by Sex.

Figure displays the predicted probability of each tobacco use outcome for SM and non-SM respondents across waves 1-8, separately by sex, and controlling for covariates. For all models except the poly-tobacco use model, asterisks signify a significant difference (p<0.05) between SM and non-SM respondents at each wave. For poly-product use, asterisks signify a significant difference (p<0.05) in use of 1 (versus 0) products between SM and non-SM respondents; crosses (†) signify a significant difference (p<0.05) in use of 2+ (versus 0) products between SM and non-SM respondents. All significance tests were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction method.

For all models except poly-tobacco use:

For poly-tobacco use model:

SM Disparities in Tobacco Product Use Across the Transition to Young Adulthood

Table 2 presents differences in tobacco product use by SM status across the transition to young adulthood, separately by sex. Among females, SM females had higher prevalence rates of any tobacco use (difference: 9.1%), cigarette use (difference: 10.0%), e-cigarette use (difference: 9.2%), and use of two or more tobacco products (difference: 9.9%). Unadjusted and adjusted mixed effects logistic regression models also estimated the association between SM status and use of each tobacco outcome, across the transition to young adulthood. In adjusted models, SM females had higher odds of most outcomes, compared to non-SM females (any: aOR=2.4 [1.6, 3.5]; cigarettes: aOR=4.7 [2.7, 8.0]; e-cigarettes: aOR=2.4 [1.6, 3.5]; other: aOR=1.7 [1.1, 2.6]; poly [2+ vs. 0 products]: aOR=3.9 [2.5, 6.0]).

Table 2.

Associations between Sexual Minority Status and Tobacco Product Use During Transition to Adulthood (W8-W9)

| Females | Males | Females vs. Males | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Prevalence | Difference in Prevalence | Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model | Absolute Prevalence | Difference in Prevalence | Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model | ||

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | |

| Any Tobacco Use | 0.159 | ||||||||

| Non-Sexual Minority | 22.7 (21.0, 24.5) | Ref | Ref | 28.7 (26.6, 30.9) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Sexual Minority | 31.8 (28.0, 35.9) | 9.1 (4.7, 13.4) | 1.7 (1.3, 2.2) | 2.4 (1.6, 3.5) | 28.7 (22.6, 35.6) | −0.0 (−6.9, 6.8) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.7) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.2) | |

| Cigarettes | 0.041 | ||||||||

| Non-Sexual Minority | 6.8 (5.8, 7.9) | Ref | Ref | 13.4 (11.8, 15.0) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Sexual Minority | 16.7 (13.8, 20.2) | 10.0 (6.6, 13.3) | 4.4 (2.7, 7.4) | 4.7 (2.7, 8.0) | 15.8 (11.2, 21.8) | 2.4 (−3.1, 7.9) | 1.3 (0.6, 3.0) | 1.4 (0.6, 3.1) | |

| E-Cigarettes | 0.040 | ||||||||

| Non-Sexual Minority | 22.0 (20.3, 23.8) | Ref | Ref | 26.8 (24.7, 28.9) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Sexual Minority | 31.2 (27.4, 35.3) | 9.2 (4.9, 13.5) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.5) | 2.4 (1.6, 3.5) | 25.0 (19.3, 31.8) | −1.8 (−8.4, 4.8) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.5) | 1.0 (0.5, 1.8) | |

| Other Tobacco Products | 0.503 | ||||||||

| Non-Sexual Minority | 8.9 (7.8, 10.1) | Ref | Ref | 12.3 (10.8, 14.0) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Sexual Minority | 11.7 (9.2, 14.7) | 2.8 (−0.2, 5.8) | 1.5 (1.0, 2.2) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.6) | 11.9 (8.0, 17.4) | −0.4 (−5.3, 4.5) | 1.0 (0.5, 2.0) | 1.3 (0.6, 2.6) | |

| Poly Tobacco Use | 0.032 | ||||||||

| Number of Products (ref = 0) | |||||||||

| 1 Product | |||||||||

| Non-Sexual Minority | 18.4 (16.8, 20.0) | Ref | Ref | 17.3 (15.6, 19.2) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Sexual Minority | 17.7 (14.7, 21.2) | −0.6 (−4.3, 2.9) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.9) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.4) | 17.8 (13.0, 24.0) | 0.5 (−5.3, 6.3) | 1.1 (0.6, 2.0) | 1.1 (0.6, 2.3) | |

| 2+ Products | |||||||||

| Non-Sexual Minority | 8.5 (7.4, 9.7) | Ref | Ref | 14.9 (13.3, 16.6) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Sexual Minority | 18.4 (15.4, 22.0) | 9.9 (6.4, 13.4) | 3.0 (2.1, 4.4) | 3.9 (2.5, 6.0) | 14.6 (10.2, 20.5) | −0.3 (−5.6, 5.1) | 1.0 (0.5, 1.9) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.5) | |

Note. Adjusted models controlled for wave, school, race/ethnicity, age, parental education. Difference between females and males were tested between adjusted models using likelihood ratio tests. Though there were significant direct effects of wave on all outcomes, there were no significant sexual minority*wave interactions, for either females or males. Boldface indicates statistical significance. All significance tests were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction method.

Among males, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of tobacco product use for any of the outcomes. Similarly, no significant differences were found between SM and non-SM males, in either unadjusted or adjusted models, for any of the outcomes (any: aOR=1.2 [0.6, 2.2]; cigarettes: aOR=1.4 [0.6, 3.1]; e-cigarettes: aOR=1.0 [0.5, 1.8]; other: aOR=1.3 [0.6, 2.6]; poly [1 vs. 0 products]: aOR=1.1 [0.6, 2.3]; poly [2+ vs. 0 products]: aOR=1.2 [0.6, 2.5]). For cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and poly-tobacco use, the adjusted models estimating the associations between SM status and tobacco use differed significantly between females and males (all p<0.015). The magnitudes of the disparities at Wave 9 did not differ significantly over time, relative to Wave 8 (p>0.05 for all outcomes, data not shown).

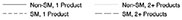

Figure 2 shows the predicted probability of each tobacco use outcome across the transition to young adulthood (waves 8-9), separately by SM status and sex, controlling for covariates. For any tobacco product use and cigarettes, SM females had higher rates of use than non-SM females across both waves (p<0.05 for all pairwise comparisons). SM and non-SM females did not differ in use of other tobacco products for either waves 8 or 9 (p>0.05 for all pairwise comparisons). SM females (vs. non-SM females) had a greater probability of e-cigarette use, and of using both 1 and 2+ tobacco products at wave 9.

Figure 2. SM Disparities in Tobacco Product Use Across the Transition to Young Adulthood, Separately by Sex.

Figure displays the predicted probability of each tobacco use outcome for SM (dashed lines) and non-SM (solid lines) respondents across waves 8-9, separately by sex, and controlling for covariates. For all models except the poly-tobacco use model, asterisks signify a significant difference (p<0.05) between SM and non-SM respondents at each wave. For poly-product use, asterisks signify a significant difference (p<0.05) in use of 1 (versus 0) products between SM and non-SM respondents; crosses (†) signify a significant difference (p<0.05) in use of 2+ (versus 0) products between SM and non-SM respondents. All significance tests were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction method.

For all models except poly-tobacco use:

For poly-tobacco use model:

DISCUSSION

This study found stark disparities in tobacco product use between SM and non-SM adolescents and young adults, across several tobacco use outcomes, inclusive of cigarettes, e-cigarettes, other tobacco products (e.g., hookah), and notably in use of multiple tobacco products. Interestingly, however, the largest differences in prevalence of use were observed for cigarettes. So, while cigarette use has been declining among youth overall (Johnston et al., 2019), SM youth (particularly females) make up a disproportionate fraction of the small population of cigarette smokers. Similar trends have been found for other disparate populations (e.g., those experiencing mental health problems, those of low socioeconomic status) (Drope et al., 2018), which may reflect a greater willingness to engage in “risky” health behaviors to cope with stress (Lehavot and Simoni, 2011; Revell et al., 1985). On the other hand, e-cigarette use was more widespread overall, possibly because e-cigarettes are perceived to be less harmful than cigarettes (Ambrose et al., 2014; Pearson et al., 2012). This might explain, in part, the smaller disparities in use of e-cigarettes observed between SM and non-SM youth.

Importantly, we found SM tobacco use disparities to be concentrated among SM females, consistent with a growing body of research (Austin et al., 2004; Dai, 2017). However, this research provides new evidence that these disparities persisted across a wide range of tobacco use outcomes, and across a 6-year period of follow-up during adolescence and young adulthood. By contrast, the disparity between SM and non-SM males was largely absent. In the general population of youth and young adults, males use tobacco products at higher rates than females, yet among SM youth, this trend is reversed, with females using more frequently than males (Austin et al., 2004; Dai, 2017) – a finding which is not well-understood. Prior research has shown that sensory factors (e.g., environmental cues) more strongly predict tobacco use among women, while pharmacologic factors (e.g., effects of nicotine) more strongly predict use among men (Perkins et al., 2006). Given the interpersonal stressors many SM youth face (e.g., discrimination, bullying) (Meyer, 2003; Russell et al., 2011; Toomey et al., 2013), it is possible SM females are especially drawn to tobacco products for sensory relief/stress management. More research is needed to understand the likely complex mechanisms contributing to sex differences in tobacco product use among SM youth. Regardless, our findings highlight the importance of assessing SM trends in tobacco use separately for females and males.

This study also adds novel information by examining the timing and onset of tobacco use disparities in a contemporary cohort of diverse adolescents and young adults in Los Angeles, CA. Given the rapidly evolving tobacco product marketplace, we were able to assess whether the timing and prevalence of disparities differed across distinct tobacco use products and outcomes. Importantly, we found that disparities for different tobacco use outcomes indeed varied by tobacco product. For some products (e.g., cigarettes and other tobacco products, such as cigars), a disparity between SM and non-SM youth was present across all waves of data collection, suggesting that SM youths’ higher rates of combustible tobacco use began prior to data collection (i.e., before high school). This may reflect concerted industry efforts to market e-cigarettes and other tobacco products to SM populations (Emory et al., 2018; Smith and Malone, 2003) and suggests that tailored prevention activities and policies should be enacted earlier than high school – perhaps in middle schools – particularly because SM youth are increasingly realizing and embracing their sexuality at earlier ages (Grov et al., 2006; Marios et al., 2015).

Conversely, use of e-cigarettes and of multiple products (poly-tobacco use) did not differ significantly between SM and non-SM respondents at baseline. Disparities in these outcomes emerged between SM and non-SM females at wave 2 (1st year of high school, spring semester). For e-cigarettes, the SM disparity dissipated after wave 4 (2nd year of high school, spring semester). This initial disparity may reflect greater susceptibility and willingness to try tobacco products among SM youth, which subsided over time. Conversely, poly-tobacco use disparities emerged early (waves 1-3), dissipated during mid-high school (waves 4-6), and re-emerged towards the end of high (waves 7-8). Together these findings highlight that disparities for various tobacco products may emerge at different time points in adolescence development. Importantly, preventing teen use of tobacco products is a priority for all teens (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012), and as such, prevention campaigns are commonplace in high schools across the country. However, these findings highlight that targeted prevention campaigns – enacted early during the first year of high school – may curb the added burden of tobacco use among SM youth.

The transition from high school to early adulthood may also represent a critical period for reducing SM tobacco use disparities. Indeed, SM females reported higher use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and poly-product use than non-SM females at wave 8 (end of high school). These disparities were maintained as respondents transitioned to early adulthood (wave 9), highlighting that the transition to adulthood is a critical period for tobacco use prevention interventions tailored to SM youth – particularly for SM females, for whom nearly half the sample had used a tobacco product in the past 6 months. However, while these disparities between SM and non-SM young adults widened somewhat over 1.5 years of follow-up, this change did not reach significance (i.e., the magnitude of the disparity did not change significantly). This finding may reflect a troubling trend of increased prevalence of tobacco product use increased among SM and non-SM young adults alike.

Limitations

This study has key limitations. First, low prevalence rates of “other” tobacco product use limited our ability to disaggregate this category into to more specific product types. Future research should assess differences in the timing and onset of disparities across specific tobacco products, such as cigars, cigarillos, and hookah. Additionally, a sensitive measure of SM status was used, which was inclusive of SM youth on the basis of their identities, attractions, and/or behaviors. As such, this study quantified the magnitude of tobacco use disparities experienced by SM youth, which is important for crafting effective policies and interventions. However, this measurement approach yields a heterogenous SM population of study. Future research should disentangle SM subgroups (e.g., analyze lesbian/gay and bisexual respondents separately) in analysis when possible. Third, information on SM status was not collected from respondents until early adulthood (wave 9). Sexual orientation development is a dynamic process that unfolds over adolescence (Floyd and Stein, 2002), and so respondents who reported different SM statuses at wave 9, compared to what they would have reported during high school, were miscategorized. Future research should assess SM status contemporaneously to tobacco product use. Finally, while there exist stark tobacco use disparities between transgender/non-binary and cisgender populations, we did not have enough transgender/non-binary respondents in our sample to make meaningful comparisons on the basis of gender identity. As such, we elected to stratify our analyses by sex (female vs. male), and to refer to respondents’ sex rather than their gender identity throughout the manuscript.

Conclusions

Using a diverse longitudinal sample of youth and young adults from Southern California, this study demonstrated marked disparities in tobacco product use between SM and non-SM youth. These disparities were concentrated among SM females, with use of tobacco products among SM males largely mirroring use by non-SM males. These findings highlight potential areas for interventions; tobacco cessation efforts must prioritize those most at risk for tobacco use – including SM females. Further, interventions must be appropriately timed, and depend on the tobacco product; cigarette disparities may be targeted prior to high school, while disparities in e-cigarette use may be more appropriately implemented during high school, and as students transition into young adulthood.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Sexual minority (SM) tobacco use disparities are concentrated among SM females.

SM tobacco use disparities extend across several tobacco products.

SM tobacco use disparities extend through both adolescence and young adulthood.

The timing of SM tobacco use disparities varies by product type.

Acknowledgements:

No other acknowledgements.

Role of Funding Sources: The funding sources were not involved in the conduct of this study.

Funding Sources: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant numbers U54CA180905, R01CA229617, and K01DA042950. This study was also funded by the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP), grant number 27-IR-0034. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or TRDRP.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: All study authors have indicated that they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Conflicts of Interest: None

The legal age to purchase tobacco products is 21 in California, and so this study reports on underaged use (the mean age of respondents during wave 9 was 19.8).

References

- Ambrose BK, Rostron BL, Johnson SE, Portnoy DB, Apelberg BJ, Kaufman AR, Choiniere CJ, 2014. Perceptions of the relative harm of cigarettes and e-cigarettes among US youth. American journal of preventive medicine 47(2), S53–S60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Lung Association, 2017. Smoking Out a Deadly Threat: Tobacco Use in the LGBT Community.

- Austin SB, Ziyadeh N, Fisher LB, Kahn JA, Colditz GA, Frazier AL, 2004. Sexual orientation and tobacco use in a cohort study of US adolescent girls and boys. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 158(4), 317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azagba S, Asbridge M, Langille D, Baskerville B, 2014. Disparities in tobacco use by sexual orientation among high school students. Preventive Medicine 69(1), 307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich J, Lee JG, Horn K, 2013. A systematic review of the aetiology of tobacco disparities for sexual minorities. Tobacco control 22(2), 66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2018a. Equality in Smoking & Disease: Nobody Wins! https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/health_effects/women-smoking/index.htm. (Accessed January 6 2020).

- CDC, 2018b. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Persons and Tobacco Use. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/disparities/lgbt/index.htm. (Accessed 09/23/2019.

- CDC, 2020. Quick Facts on the Risks of E-cigarettes for Kids, Teens, and Young Adults. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/Quick-Facts-on-the-Risks-of-E-cigarettes-for-Kids-Teens-and-Young-Adults.html. (Accessed January 6 2020).

- Corliss HL, Rosario M, Birkett MA, Newcomb ME, Buchting FO, Matthews AK, 2014. Sexual orientation disparities in adolescent cigarette smoking: intersections with race/ethnicity, gender, and age. American journal of public health 104(6), 1137–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, 2017. Tobacco Product Use Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adolescents. Pediatrics 139(4), e20163276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delahanty J, Ganz O, Hoffman L, Guillory J, Crankshaw E, Farrelly M, 2019. Tobacco use among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender young adults varies by sexual and gender identity. Drug and alcohol dependence 201, 161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilley JA, Spigner C, Boysun MJ, Dent CW, Pizacani BA, 2008. Does tobacco industry marketing excessively impact lesbian, gay and bisexual communities? Tobacco control 17(6), 385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drope J, Liber AC, Cahn Z, Stoklosa M, Kennedy R, Douglas CE, Henson R, Drope J, 2018. Who's still smoking? Disparities in adult cigarette smoking prevalence in the United States. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 68(2), 106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emory K, Buchting FO, Trinidad DR, Vera L, Emery SL, 2018. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) view it differently than non-LGBT: exposure to tobacco-related couponing, e-cigarette advertisements, and anti-tobacco messages on social and traditional media. Nicotine and Tobacco Research 21(4), 513–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Stein TS, 2002. Sexual orientation identity formation among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Multiple patterns of milestone experiences. Journal of Research on Adolescence 12(2), 167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Bimbi DS, Nanín JE, Parsons JT, 2006. Race, ethnicity, gender, and generational factors associated with the coming- out process among gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals. Journal of sex research 43(2), 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell JS, Bangdiwala SI, Deng S, Webb JP, Bradley C, 1998. Smoking initiation in youth: the roles of gender, race, socioeconomics, and developmental status. Journal of Adolescent Health 23(5), 271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L, Delahanty J, Johnson SE, Zhao X, 2018. Sexual and gender minority cigarette smoking disparities: An analysis of 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data. Preventive Medicine 113, 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME, 2019. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use 1975-2018: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger EA, Fish JN, Upchurch DM, 2020. Sexual Orientation Disparities in Substance Use: Investigating Social Stress Mechanisms in a National Sample. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 58(1), 59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JG, Griffin GK, Melvin CL, 2009. Tobacco use among sexual minorities in the USA, 1987 to May 2007: a systematic review. Tobacco Control 18(4), 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, Simoni JM, 2011. The impact of minority stress on mental health and substance use among sexual minority women. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 79(2), 159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, King KM, Miles J, Gold MA, Bukstein OG, Morse JQ, 2008. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction 103(1), 546–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, Thompson AL, 2009. Individual trajectories of substance use in lesbian, gay and bisexual youth and heterosexual youth. Addiction 104, 974–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martos AJ, Nezhad S, Meyer IH, 2015. Variations in sexual identity milestones among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 12(1), 24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Matthews AK, Lee JGL, Veliz P, Hughes TL, Boyd CJ, 2018. Tobacco Use and Sexual Orientation in a National Cross-sectional Study: Age, Race/Ethnicity, and Sexual Identity–Attraction Differences. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 54(6), 736–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, 2003. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological bulletin 129(5), 674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JL, Richardson A, Niaura RS, Vallone DM, Abrams DB, 2012. e-Cigarette awareness, use, and harm perceptions in US adults. American journal of public health 102(9), 1758–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Doyle T, Ciccocioppo M, Conklin C, Sayette M, Caggiula A, 2006. Sex differences in the influence of nicotine dose instructions on the reinforcing and self-reported rewarding effects of smoking. Psychopharmacology 184(3-4), 600–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revell A, Warburton DM, Wesnes K, 1985. Smoking as a coping strategy. Addictive behaviors 10(3), 209–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Ryan C, Toomey RB, Diaz RM, Sanchez J, 2011. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescent school victimization: Implications for young adult health and adjustment. Journal of School Health 81(5), 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MS, Collins RL, 2019. Early Alcohol and Smoking Initiation: A Contributor to Sexual Minority Disparities in Adult Use. American journal of preventive medicine 57(6), 808–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EA, Malone RE, 2003. The outing of Philip Morris: advertising tobacco to gay men. American Journal of Public Health 93(6), 988–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EA, Thomson K, Offen N, Malone RE, 2008. “If you know you exist, it’s just marketing poison”: meanings of tobacco industry targeting in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community. American Journal of Public Health 98(6), 996–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Card NA, Russell ST, 2013. Gender-nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: school victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014. The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Watson RJ, Lewis NM, Fish JN, Goodenow C, 2018. Sexual minority youth continue to smoke cigarettes earlier and more often than heterosexuals: Findings from population-based data. Drug and alcohol dependence 184, 64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheldon CW, Kaufman AR, Kasza KA, Moser RP, 2018. Tobacco use among adults by sexual orientation: findings from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study. LGBT health 5(1), 33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2007. Gender and tobacco control: a policy brief. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.