Abstract

Purpose:

To determine whether the administration of a microenema immediately prior to rectal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) decreases the level of gas-related artifacts on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences.

Methods:

This retrospective analysis included 492 (183 baseline and 309 post total neoadjuvant treatment [TNT]) consecutive MRI scans for rectal cancer from January 2019–January 2020. Scan-related factors were identified including microenema use (yes or no), field of view (FOV) in DWI (b=800 or b=1500), and magnet strength (1.5T or 3T). Two readers scored DWI studies for gas-related artifacts and T2-weighted sequences for the amount of intraluminal gas on a 5-point scale. Fisher’s exact test and the Rao–Scott Chi-squared test were used to examine associations between microenema use and other factors. Generalized estimating equation and multivariable regression models were performed to examine the effect of microenema use in subgroups for each reader. Cohen’s κ was used to assess inter-reader agreement.

Results:

Gas-related artifact levels decreased in scans with microenema (P < 0.001) as well as when stratified by FOV (P ≤ 0.003). For both readers, post-TNT scans with microenema showed lower artifact levels overall (P < 0.014 and P < 0.001), and in post-TNT subgroups of axial DWI (P ≤ 0.006 and P < 0.001) and scans acquired with a 3T magnet (P ≤ 0.001 for both FOV). No evidence of decreased artifact level was found for baseline studies. Decreased gas was seen with microenema use (P < 0.001 for both readers). Inter-reader agreement on artifact level and gas level assessments ranged from slight to substantial (κ=0.273–0.685).

Conclusion:

Microenema use prior to rectal MRI reduces gas-related artifacts on DWI, including both large and small FOV sequences and particularly on post-TNT scans performed at 3T, and offers a viable solution to improve DWI quality.

Keywords: rectal neoplasms, microenema, magnetic resonance imaging, diffusion-weighted imaging, susceptibility artifact

Introduction

Colorectal cancer represents the third leading cause of new cancer cases and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in men and women combined. In 2020, approximately 43,340 new cases of rectal cancers will be diagnosed in the United States. The estimated overall number of people to die from colorectal malignancies in 2020 is 53,200 [1]. Currently, management plans are tailored for patients upon diagnosis, based on clinical evaluation and diagnostic imaging. Rectal MRI is an established examination in both baseline and post-total neoadjuvant treatment (TNT) evaluation in rectal cancer patients [2,3]. Within post-TNT rectal MRI, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences have shown added value, particularly to determine the presence of viable tumor [4–7]. As such, the latest recommendations from the 2016 European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal radiology (ESGAR) consensus meeting included the routine use of DWI sequences in rectal cancer imaging, particularly for restaging to evaluate response to TNT [8]. However, clinically utilized DWI sequences in rectal MRI are prone to susceptibility artifacts, including gas-related artifacts due to a gas-filled bowel [9].

Magnetic susceptibility artifacts occur at the interface of two matters secondary to differences in the level of magnetization, leading to image ghosting and distortion. These artifacts are reportedly exaggerated at higher field strengths [2,10–12]. In the case of a gas-filled bowel, when the rectum is evaluated, gas-induced susceptibility artifacts can markedly compromise the diagnostic image quality, sometimes even rendering the images non-diagnostic leading to decreased accuracy in interpretation.

Decreasing gas-induced susceptibility artifacts is essential for accurate imaging interpretation. Attempts to minimize gas-related artifacts have largely relied on manipulating DWI parameters [13,14]. Recently, several institutions have implemented different preparatory approaches, including the use of microenema. The use of microenema prior to rectal MRI post TNT demonstrated significant reduction in the incidence and severity of gas-related artifacts when evaluating artifacts performed on 1.5T systems using a b-value of 1000 s/mm2 [15].

The purpose of our study was to determine whether administration of microenema prior to rectal MRI decreases the level of gas-related artifacts on DWI sequences in various imaging scenarios when the rectum is the organ of investigation. We hypothesized that there would be fewer and less severe artifacts when a microenema is used in both baseline and post-neoadjuvant treatment imaging under varying b-values and magnetic field strengths.

Materials and methods

Study population

This retrospective, single-institution study was approved by the Institutional Review Board with a waiver of written informed consent and was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. We retrospectively examined our database for consecutive patients who underwent rectal MRI after the introduction of microenema to our routine rectal MRI protocol on January 30, 2019, and identified all scans performed until January 30, 2020. The inclusion criterion for this study was MRI scan performed for a diagnosis of rectal cancer at baseline (i.e. baseline MRI) or within one year of completion of TNT (i.e. post-TNT MRI). The exclusion criteria were lack of information whether microenema was used or not, duplicate studies, same-day enema for a different procedure, post-surgical studies, non-rectal cancer patients, recurrences, patients with stents in situ, post-induction-chemotherapy scans, and post-TNT scans performed one year after completion of chemoradiotherapy. The study selection process is outlined in Figure 1.

Fig 1.

Flowchart of included MRI rectal scans

Rectal MRI protocol

All scans were acquired using different GE Healthcare System platforms (Discovery 2MR750, Optima MR450w, Signa EXCITE, and Signa PET MRI; Waukesha, WI) with either 1.5 Tesla (1.5T) or 3 Tesla (3T) magnet strength and a pelvic phased-array coil. Our routine rectal MRI protocol included a straight axial T2-weighted sequence and two separate DWI sequences in addition to other T2-weightd multiplanar sequences. Axial DWI included a large field of view (FOV) axial sequence (24 cm) with a b-value of 800 s/mm2 and matched the straight axial T2-weighted sequence slice locations from the iliac crest to anal verge. FOV optimized and constrained undistorted single-shot (FOCUS) DWI included a smaller FOV axial sequence (varied based on patient size) with a b-value of 1500 s/mm2 and matched to the straight axial T2-weighted sequence slice locations (16 slices only) covering the area of the tumor. Table 1 details the the routine acquisition protocol for T2-weighted axial and DWI sequences for both 1.5T and 3T magnet strength scanners. Table 1 shows our acquisition parameters for the axial T2 and DWI sequences used for scoring in our study for both 1.5T and 3T magnet strength scanners. It does not include our complete imaging protocol.

Table 1.

MRI protocol for the axial T2 and DWI sequences used for scoring in our study.

| 1.5T magnet strength scanner | 3T magnet strength scanner | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Series Descriptor | Axial T2 | Axial DWI b 800 | Focus DWI b 1500 | Axial T2 | Axial DWI b 800 | Focus DWI b 1500 |

| Generic sequence name | FSET2 | 2D | Focus Diffusion | FSET2 | 2D | Focus Diffusion |

| Plane | Axial | Axial | Axial | Axial | Axial | Axial |

| Field of View (cm) | 20–24 | 24 | 24 | 20–24 | 24 | 20–24 |

| Slice Thickness (mm) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Gap (mm) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| b-value | 800 | 1500 | 800 | 1500 | ||

| Saturation Pulse | S/I/A | N/A | N/A | S/I/A | N/A | N/A |

| TE1/TE2 | 110 | Min | Min | 110 | Min | Min |

| TR | 4000–6000 | Auto-TR (4000–10000) | Auto-TR (4000–10000) | 4000–6000 | Auto-TR (4000–10000) | Auto-TR (4000–10000) |

| Flip Angle | 90 | N/A | N/A | 90 | N/A | N/A |

| Bandwidth (kHz) | 32 | N/A | N/A | 41 | N/A | N/A |

| ETL | 24 | N/A | N/A | 24 | N/A | N/A |

| NEX | 3 | 16 | 16 | 3 | 16 | 16 |

| Frequency Steps | 320 | 128 | 128 | 320 | 128 | 140 |

| Phase Encoding Steps | 224 | 128 | 128 | 224 | 128 | 70 |

| Frequency Direction | A/P | R/L | R/L | A/P | R/L | R/L |

TE, echo time; TR, repetition time; ETL, echo train length; NEX, number of excitations; FSE, fast spin echo; A/P, Anterior/Posterior; R/L, Right/Left.

The perscribed microenema was a hyperosmolar docusate sodium laxative in 5 ml liquid (Enemeez®). The onset of action is reported to be within 2–15 mins of application and was self-administered by the patient immediately before the imaging acquisition. Microenema was not administered in patients who had colostomy, known anal stricture, rectal abscess or fistula, anal or rectal pain, current feeling of malaise, nausea, or abdominal pain, or if patients expressed personal preference of not having the microenema.

MRI image assessment

We evaluated the presence and severity of gas-related artifacts (i.e. artifact level) within the rectum in all DWI studies with and without microenema as well as the presence and amount of rectal gas (i.e. gas level) in all axial T2-weighted studies.

DWI studies were scored by two readers (VSJ and SJT) with experience in oncologic imaging blinded to clinical information, to each other’s scores, as well as to whether microenema was or was not administrated prior to the scan. Artifact level was scored based on a 5-point scale as: 1 = no artifact, complete visualization of the rectal wall and lumen; 2 = mild artifact (no effect on diagnostic image quality, < 25% rectal wall distortion), 3 = moderate artifact (some effect on diagnostic image quality, 25–50% rectal wall distortion), 4 = severe artifact (considerable effect on diagnostic image quality but still interpretable, 50–75% rectal wall distortion), and 5 = extensive artifact (non-diagnostic images, > 75% rectal wall distortion) [16,17] (Figure 2). The initial 20 studies were jointly read by both readers in order to normalize the subsequent scoring and the remaining studies were read independently. There was a one-week period between the scoring of axial DWI and FOCUS DWI studies to reduce recall bias. Axial T2-weighted studies were similarly assesed for gas level based on a 5-point scale as: 1 = no gas, 2 = minimal gas, 3 = small amount of gas, 4 = moderate amount of gas, and 5 = large amount of gas [16,17] (Figure 3).

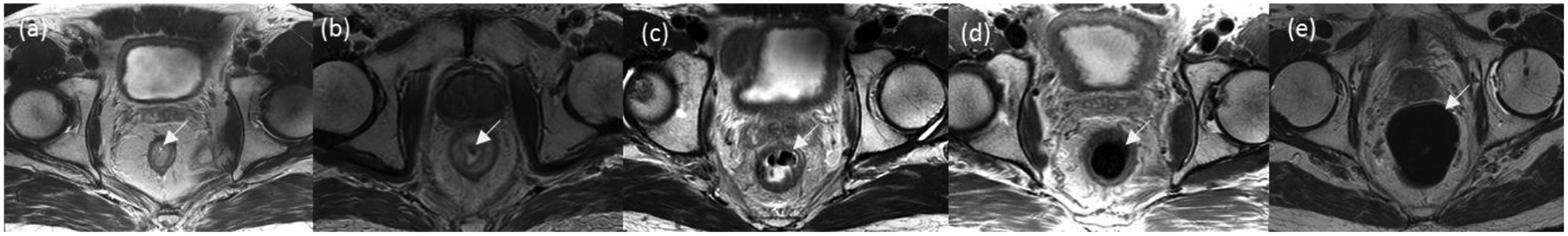

Fig 2.

Representative axial slices depicting the presence and severity of artifacts within the large field of view axial DWI sequences with b = 800. The scoring system was based on 5-point scale as follows: Score 1 = No artifact (a). Score 2 = Mild artifact (b) (arrow). Score 3 = Moderate artifact (c). Score 4 = Severe artifact (d). Score 5 = Extensive artifact (e)

Fig 3.

Representative T2 axial slices depicting the presence and amount of gas within axial T2 sequences. The scoring system was based on a 5-point scale as follows: 1 = No gas (a). 2 = Minimal amount of gas (b). 3 = Small amount of gas (c). 4 = Moderate amount of gas (d). 5 = Large amount of gas (e)

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test was used to examine the associations between microenema use and patient characteristics, artifact level (no/mild vs moderate/severe/extensive), and gas level (no/minimal/small vs moderate/large). The Rao–Scott Chi-squared test was used to examine the overall association between microenema use and artifact level for each reader separately. Some patients had multiple studies included; we analyzed these studies independently considering that the artifact level is primarily gas-level related rather than patient-level related.

Subsequently, two sets of multivariable regression models were performed for each reader to examine the effect of microenema use under specified combinations of DWI view (axial DWI and FOCUS DWI views), scan timing (baseline and post-TNT groups), field strength (1.5 and 3T), and gas level.

Model I: To examine the effects of microenema use on artifact level in subsets of baseline and post TNT, and within each timing group, on axial DWI and on focus DWI views, and further under 1.5 and 3T field strength, we adopted general estimating equations (GEE) regressions with interactions terms, a logit link function and an exchangeable correlation structure. No model selection was performed. Adjustment for multiple testing was applied on confidence interval (CI) estimations and p-values using the simultaneous inference approach [18] on multiple contrasts.

Model II: To test whether the effect of microenema use on artifact level is different under different gas levels in all scans, GEE with a logit link function and an exchangeable correlation structure was used. Adjustment for multiple testing was also applied.

To assess inter-reader agreement on artifact level and gas level, Cohen’s kappa (κ) was estimated with bootstrapping 95% CIs. κ values were interpreted as follows: 0.00–0.20 = slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 = fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 = moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 = substantial agreement, and 0.81–1.00 = almost perfect agreement.

All statistical analyses were performed in software packages R version 3.6.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

The study group consisted of 394 patients (236 males and 158 females) with a mean age of 59 years (ranging from 19 to 96 years) and a total of 492 MRI scans. A lower proportion of women had scans with microenema compared to men (P = 0.008). There was no significant difference in the number of scans with microenema and without microenema based on scan timing (baseline vs. post-TNT) and magnet field strength (1.5T vs. 3T). A summary of scan characteristics is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of patient characteristics, scan artifact levels, and associations with microenema (ME) use.

| Overall1 | ME Used1 | ME not used1 | p-value2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 492 | 196 | 296 | |

| Age at diagnosis | 59 (19, 96) | 58 (22, 88) | 60 (19, 96) | 0.046 |

| Sex | 0.008 | |||

| Male | 301 (61%) | 134 (68%) | 167 (56%) | |

| Female | 191 (39%) | 62 (32%) | 129 (44%) | |

| Scan timing | 0.6 | |||

| Baseline | 183 (37%) | 76 (39%) | 107 (36%) | |

| Post CRT | 309 (63%) | 120 (61%) | 189 (64%) | |

| Field strength | 0.7 | |||

| T1.5 | 113 (23%) | 43 (22%) | 70 (24%) | |

| T3 | 379 (77%) | 153 (78%) | 226 (76%) | |

Statistics presented: median (minimum, maximum); n (%)

Statistical tests performed: Wilcoxon rank-sum test; Fisher’s exact test

Both readers reported a significant decrease in artifact level in studies with microenema compared to studies without microenema in the entire cohort (P < 0.001) as well as within axial DWI views (P < 0.001) and FOCUS DWI views (P ≤ 0.003).

Overall, for post-TNT studies, microenema use showed a significant decrease in artifact level. Post-TNT studies performed with axial DWI views showed consistently lower odd ratios (ORs) of moderate to extensive artifacts with microenema use. For post-TNT FOCUS DWI views, one reader showed significant decrease in the level of artifacts with microenma use. When stratified according to field strength, among the post-TNT studies performed with a 3T field strength, both readers reported a significant decrease in artifact level with microenema use; however, among the post-TNT studies performed using a 1.5T scanner, only one reader reported a significant decrease in artifact level with microenema use for both axial and FOCUS DWI views (Figure 4).

Fig 4.

Forest plot on odds ratio estimates of artifact levels for studies performed with microenema (ME) vs without microenema (ME vs No ME) in all post-TNT studies for reader 1 (R1) and reader 2 (R2), as well as stratified first by field of view (axial DWI and FOCUS DWI) followed by magnet strength (1.5T and 3T). Except for studies performed on FOCUS DWI and 1.5 magnet strength for one reader, there was a significant decrease in artifact level for all post-TNT studies.

On the other hand, for baseline studies, microenema use did not show any significant improvement in artifact level, including when further stratified acording to DWI view or field strength (Figure 5).

Fig 5.

Forest plot on odds ratio estimates of artifact level for studies performed with microenema (ME) vs without microenema (ME vs No ME) in all baseline studies for reader 1 (R1) and reader 2 (R2), as well as stratified first by field of view (axial DWI and FOCUS DWI) followed by magnet strength (1.5T and 3T). There was no significant decrease in artifact level with microenema use in any baseline group.

Between the axial DWI and FOCUS views, there was no significant difference in artifact level either overall or when categorized by field strength (P > 0.1 for both readers in all groups).

Regarding microenema use and gas level, studies with microenema showed a signficantly decreased gas level (P < 0.001 for both readers). However, if the gas level was moderate to large, there was no significant difference in artifact level whether or not microenema was used (OR = 0.79 for both readers; 95% CI: 0.45–1.4 and 0.41–1.52 for R1 and R2, respectively). Similar results were seen in studies with no or small amount of gas (OR = 0.61 and 0.55, 95% CI 0.33–1.13 and 0.3–1.02 for R1 and R2, respectively).

Inter-reader agreement on artifact level and gas level assessments ranged from slight to substantial between the two readers (κ = 0.273–0.685) for overall scans and in subgroups of scan timing, scan type, field strength, and gas level (Figure 6).

Fig 6.

Cohen’s κ along with bootstrapping confidence intervals for inter-reader agreement on artifact levels for all studies performed with microenema vs without microenema as well as in all subgroups and for rectal gas.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated whether microenema use prior to rectal MRI reduces gas-related artifacts on diffusion-weighted images. Our results showed that, overall, when microenema is administered just before the acquisition of MRI rectal studies, significantly lower levels of artifacts are present on diffusion-weighted images compared to studies performed without microenema. This remained true when results were stratified for the axial DWI views and FOCUS DWI views. When comparing the effect of microenema on artifact level between post-TNT studies and baseline studies, post-TNT studies (both axial DWI and FOCUS DWI) performed with a 3T magnet showed a significant decrease in artifact level with microenema use.

DWI sequences are an integral part of the restaging MRI post TNT as they aid in lesion detection and characterization [18,19]. Previously, Van Griethuysen et al. studied the effect of administering microenema to improve the image quality of DWI of the rectum at 1.5T after long course chemoradiotherapy [15]. The study reported an excellent interobserver agreement and showed a significant decrease in the incidence and severity of the susceptibility artifact in the group with microenema. Our study featured a larger sample size and all studies were scored by both readers. In addition, the majority of our scans were performed on 3T scanners and we analyzed post-TNT scans using two FOVs in DWI. The added value in our study is that we showed that microenema use can significantly improve the quality of post-TNT rectal MRI performed at 3T magnet strength in both axial DWI and FOCUS DWI sequences.In addition to post-TNT studies, we also included baseline MRI studies for evaluation. Although the recent literature suggests that DWI sequences can help in tumor delineation and also provide prognostic information [20], the routine use of DWI in the baseline evaluation of rectal MRI is still debated and performed based on each institution’s preference. Our study did not show any significant decrease in the level of gas-related artifacts in baseline studies in general or when stratified according to FOV or magnet field strength when microenema was administered. This lack of significance may in part be due to the small number of baseline studies compared to the post-TNT studies, especially when further stratified into various subgroups (field strength, DWI view).

At our institution, we routinely perform two DWI sequences in the straight axial plane, one with a large FOV with the highest b-value of 800 s/mm2 and a second with a small FOV with the highest b-value of 1500 s/mm2 centered over the tumor. The effect of microenema use under a high b-value of 1500 s/mm2 has not been studied. Thus, our study newly shows that microenema use can significantly decrease the level of artifacts on a sequence with a high b-value of 1500 s/mm, although it did not demonstrate that the level of improvement was better with a higher or lower b-value.

In our study, microenema use showed a significant decrease in the amount of rectal gas. An important consideration here is that the microenema was administered just before MRI aquisition. Rectal gas may accumulate if there is a considerable time lapse between emptying the bowel and MRI acquisition, although this time interval may vary between individuals. When there was a moderate to large amount of gas in the rectum, we did not detect any significant improvement in the level of artifacts despite microenema use. This suggests that rectal gas plays an important role in the development of higher levels of artifacts and we postulate that improvements in image quality in studies with microenema is secondary to emptying bowel gas immediately before the scan. This theory might be applied to baseline studies where the gaseous dilatation of bowel may be limited by the presence of significant intraluminal tumor causing luminal rigidity, thereby questioning the value of microenema in these cases. However, further studies will be required to prove this concept.

One interesting observation is that there was a significant sex imbalance in our cohort, with a higher proportion of male patients undergoing microenema administration compared to female patients. We did not specifically study the effect of microenema based on the anatomical differences between male and female patients as it was beyond the scope of this study. However, this could certainly be investigated in furture studies. The exact cause for not administering microenema was not recorded consistently in our database; however, the most common cause was felt to be patient preference. This may in part explain the greater proportion of females undergoing studies without microenema and strengthens the argument for patient as well as clinician education on the usefulness of microenema in this clinical scenario.

Our study has certain limitations. First, we were limited by an imbalanced cohort, with the majority of patients undergoing studies on a 3T scanner compared to 1.5T which probably affected lack of statistical significance in the 1.5T group. However, susceptibility artifacts are exaggerated at 3T [10], and thus our results in the 3T group are particularly relevant. Second, we did not separate our analyses based on the initial staging of the disease or whether residual disease was present on the post-treatment scans. However, whether the presence of significant intraluminal tumor volume impacts the value of microenema would require further research and was beyond the scope of current study. Third, image quality was assessed based on the subjective assessment of individual readers. We are aware that such subjective judgment has the potential to yield inconsistency between observers, and we may have introduced observer bias. To alleviate this limitation, we used a 5-point scale and implemented joint training by the two readers at the commencement of study. Fourth, patients were scanned on different scanners and we did not evaluate the technical acquisition parameters. However, the goal of this study was not to optimize the technical parameters of DWI. Finally, this was a retrospective analysis with its inherent limitations. However, the acquisition of rectal MRI scans and the administration of microenema in our institute are very much standardized.

In conclusion, our study shows microenema use in bowel preparation immediately before acquisition of rectal MRI significantly reduces susceptibility artifacts in both axial DWI and FOCUS DWI sequences. The effect is most consistently seen on post-TNT studies performed with a 3T magnet strength. The presence of rectal gas has a significant impact on the severity of artifacts and is appreciably reduced by the administration of microenema just before the acquisition of scan.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Joanne Chin, MFA, ELS, and Regina C. Loccisano BS R.T.(R)(M)(CT)(MR), for their editorial support of this article.

Funding: This research was funded in part by the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (institutional review board at Memorial Sloan Kettering cancer Center, IRB 16–923 and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Availability of data and material: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, (eds). CK SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2017, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2017/, based on November 2019 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gowdra Halappa V, Corona Villalobos CP, Bonekamp S, Gearhart SL, Efron J, Herman J, Kamel IR (2012) Rectal imaging: part 1, High-resolution MRI of carcinoma of the rectum at 3 T. AJR Am J Roentgenol 199 (1):W35–42. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.8134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horvat N, Carlos Tavares Rocha C, Clemente Oliveira B, Petkovska I, Gollub MJ (2019) MRI of Rectal Cancer: Tumor Staging, Imaging Techniques, and Management. Radiographics 39 (2):367–387. doi: 10.1148/rg.2019180114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambregts DM, Vandecaveye V, Barbaro B, Bakers FC, Lambrecht M, Maas M, Haustermans K, Valentini V, Beets GL, Beets-Tan RG (2011) Diffusion-weighted MRI for selection of complete responders after chemoradiation for locally advanced rectal cancer: a multicenter study. Ann Surg Oncol 18 (8):2224–2231. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1607-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park MJ, Kim SH, Lee SJ, Jang KM, Rhim H (2011) Locally advanced rectal cancer: added value of diffusion-weighted MR imaging for predicting tumor clearance of the mesorectal fascia after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Radiology 260 (3):771–780. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11102135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambregts DM, Lahaye MJ, Heijnen LA, Martens MH, Maas M, Beets GL, Beets-Tan RG (2016) MRI and diffusion-weighted MRI to diagnose a local tumour regrowth during long-term follow-up of rectal cancer patients treated with organ preservation after chemoradiotherapy. Eur Radiol 26 (7):2118–2125. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-4062-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambregts DMJ, Boellaard TN, Beets-Tan RGH (2019) Response evaluation after neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer using modern MR imaging: a pictorial review. Insights Imaging 10 (1):15. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0706-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beets-Tan RGH, Lambregts DMJ, Maas M, Bipat S, Barbaro B, Curvo-Semedo L, Fenlon HM, Gollub MJ, Gourtsoyianni S, Halligan S, Hoeffel C, Kim SH, Laghi A, Maier A, Rafaelsen SR, Stoker J, Taylor SA, Torkzad MR, Blomqvist L (2018) Magnetic resonance imaging for clinical management of rectal cancer: Updated recommendations from the 2016 European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) consensus meeting. Eur Radiol 28 (4):1465–1475. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5026-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Bihan D, Poupon C, Amadon A, Lethimonnier F (2006) Artifacts and pitfalls in diffusion MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 24 (3):478–488. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenkrantz AB, Oei M, Babb JS, Niver BE, Taouli B (2011) Diffusion-weighted imaging of the abdomen at 3.0 Tesla: image quality and apparent diffusion coefficient reproducibility compared with 1.5 Tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging 33 (1):128–135. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merkle EM, Dale BM (2006) Abdominal MRI at 3.0 T: the basics revisited. AJR Am J Roentgenol 186 (6):1524–1532. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrmann KA, Paspulati RM, Lauenstein T, Reiser MF (2010) Benefits and challenges in bowel MR imaging at 3.0 T. Top Magn Reson Imaging 21 (3):165–175. doi: 10.1097/RMR.0b013e31822a3294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Q, van Houdt PJ, Lambregts DMJ, van Triest B, Kop MPM, Coolen BF, Strijkers GJ, van der Heide UA, Nederveen AJ (2020) Locally advanced rectal cancer: 3D diffusion-prepared stimulated-echo turbo spin-echo versus 2D diffusion-weighted echo-planar imaging. Eur Radiol Exp 4 (1):9. doi: 10.1186/s41747-019-0138-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nasu K, Kuroki Y, Kuroki S, Murakami K, Nawano S, Moriyama N (2004) Diffusion-weighted single shot echo planar imaging of colorectal cancer using a sensitivity-encoding technique. Jpn J Clin Oncol 34 (10):620–626. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Griethuysen JJM, Bus EM, Hauptmann M, Lahaye MJ, Maas M, Ter Beek LC, Beets GL, Bakers FCH, Beets-Tan RGH, Lambregts DMJ (2018) Gas-induced susceptibility artefacts on diffusion-weighted MRI of the rectum at 1.5 T - Effect of applying a micro-enema to improve image quality. Eur J Radiol 99:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim C, Quon J, McInnes M, Shabana WM, El-Khodary M, Schieda N (2015) Does a cleansing enema improve image quality of 3T surface coil multiparametric prostate MRI? J Magn Reson Imaging 42 (3):689–697. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davenport MS, Viglianti BL, Al-Hawary MM, Caoili EM, Kaza RK, Liu PS, Maturen KE, Chenevert TL, Hussain HK (2013) Comparison of acute transient dyspnea after intravenous administration of gadoxetate disodium and gadobenate dimeglumine: effect on arterial phase image quality. Radiology 266 (2):452–461. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padhani AR, Liu G, Koh DM, Chenevert TL, Thoeny HC, Takahara T, Dzik-Jurasz A, Ross BD, Van Cauteren M, Collins D, Hammoud DA, Rustin GJ, Taouli B, Choyke PL (2009) Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging as a cancer biomarker: consensus and recommendations. Neoplasia 11 (2):102–125. doi: 10.1593/neo.81328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie H, Sun T, Chen M, Wang H, Zhou X, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Wang J, Fu W (2015) Effectiveness of the apparent diffusion coefficient for predicting the response to chemoradiation therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 94 (6):e517. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakke KM, Hole KH, Dueland S, Grøholt KK, Flatmark K, Ree AH, Seierstad T, Redalen KR (2017) Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of rectal cancer: tumour volume and perfusion fraction predict chemoradiotherapy response and survival. Acta Oncol 56 (6):813–818. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1287951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]