Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Primary gastrointestinal (GI) melanomas, compared to cutaneous melanomas, have a much lower incidence. As a result, there is a paucity of data regarding their presentation, treatment, and prognosis. The aim of this study was to analyze the incidence, patient characteristics, treatment patterns, and survival of primary GI melanomas in comparison with cutaneous melanomas using a population-based cohort.

METHODS:

Patients diagnosed with primary GI and cutaneous melanomas were identified from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results 1973-2016 data.

RESULTS:

A total of 872 primary GI melanomas and 319,327 cutaneous melanomas were identified. GI melanoma incidence increased by an annual percent change of 1.82 (p<0.05) during the study period. The most common sites for GI melanoma were the anus (50%) and rectum (34%). Compared to cutaneous melanoma, patients diagnosed with GI melanoma were older, female (58% vs 45%), non-White (16% vs 6%), and presented with a higher stage (36% vs 4% distant stage, all p<0.001). GI melanomas had significantly worse cancer-specific survival (CSS) compared to cutaneous melanoma. Despite the poor prognosis, the CSS has increased in recent years. Among anorectal melanomas patients, local excision with chemotherapy and/or radiation had a similar CSS compared to those with major surgery only.

CONCLUSIONS:

Despite a steady increasing incidence since 1975, GI melanomas are rare, present with advanced stages, and have worse outcomes compared to cutaneous melanomas. The improved prognosis of these tumors in recent years might reflect the impact of novel targeted treatments and the more common use of local tumor excision over major resections.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal melanoma/cancer, anorectal melanoma, SEER program, cutaneous melanoma

Introduction

Melanoma accounts for approximately 6% of all primary cancers in the United States with over 100,350 new patients expected to be diagnosed in 2020 (1). While the majority of melanomas are cutaneous in origin, rare cases of primary gastrointestinal (GI) melanomas have been reported from mucosal membranes lining the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum, and anus (2-8). Cutaneous melanomas tend to metastasize to the GI tract and approximately 60% of cutaneous melanoma patients have GI metastases at autopsy (9), as a result majority of the clinically diagnosed melanomas in the GI tract represent metastatic disease. Therefore, the diagnosis of a primary GI melanoma requires consideration of a spontaneously regressed or undiagnosed cutaneous melanoma.

However even though melanocytes do not normally occur in the GI tract ectopic melanocytes have been found in the rectum (10, 11), esophagus (12), and other sites of the GI tract (13). Several hypotheses have been put forward regarding the origin of these melanocytes including (i) differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into melanocytes, (ii) migration of melanocytes from anus to the rectum, or (iii) anomalies in cell migration during fetal development (13). Primary GI melanomas are believed to arise from these ectopic melanocytes and several studies have (2-8) reported cases of GI melanoma in the absence of primary cutaneous melanoma, validating primary GI melanoma as a distinct entity.

Compared to cutaneous melanomas, primary GI melanomas have been reported to have a poorer prognosis due to delayed presentation at diagnoses and aggressive biology (8, 14-16). While treatment regimens for cutaneous melanoma are well established (17, 18), there is a paucity of data on prognostic factors and survival outcomes of patients with primary GI melanoma. As a result, there is limited literature to develop evidence-based treatment guidelines (19). Surgery remains the primary treatment for GI melanomas, although there is controversy regarding its extent as well as the role of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation (20, 21). Furthermore, in recent years, targeted immunotherapies have been found to extend survival for patients diagnosed with advanced cutaneous melanoma. Many of these new biologic treatments have also been used in the treatment of GI melanomas with response rates up to 40% (22, 23).

The aims of the current study were to compare demographic characteristics, incidence, treatment patterns and trends, as well as survival outcomes of patients diagnosed with primary GI melanomas and compare them to cutaneous melanoma patients utilizing a large population-based database.

Materials and Methods

Data source

Patients ages 18 to 100 who were diagnosed with primary malignant melanoma between 1973 and 2016 were identified from the SEER 18 Registries using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O-3) code. Primary GI melanoma (hereby referred to as GI melanoma) was characterized by melanoma histology ICD-O-3 8720-8799 and primary site codes for the esophagus (C150-C159), stomach (C160-C169), small intestine (C170-C179), colon (C180-C189 and C260), rectum (C199, C209), and anus (C210, C211, C212, C218). Anal and rectal melanoma patients were combined due to the overlap of these sites and referred to as anorectal melanoma. Due to the limited number of patients of esophageal, stomach, small intestinal, and colon melanoma, these sites were combined into one category defined as “other GI melanoma sites”. Cutaneous melanoma served as a comparison group and was defined by primary site codes C440-C449 and melanoma histology ICD-O-3 8720-8799. Patients retrieved from death certificates or autopsy results were excluded.

Patient and tumor information included age, gender, race, marital status, year of diagnosis, SEER summary stage, tumor size, primary surgery site, radiation recipient status, chemotherapy recipient status, and vital status. Treatment variables were only available for patients diagnosed after 1988. For patients diagnosed before 1988 primary surgery site was categorized as follows from the site specific surgery (1973-1997) variable for patients diagnosed before 1998, local tumor excision (colon and rectum (code 20); stomach (10); esophagus, intestine, and anus (35); cutaneous (20-38)), major surgery (colon (30-80); rectum (30, 50-80); stomach (20-80); esophagus, intestine, anus, and cutaneous (40-80)), and none or local tumor destruction only (stomach (0-7); colon and rectum (0-7, 10); esophagus, intestine, and anus (0-7,10-30); cutaneous (0-7,10,18)). The surgery primary site 1998+ variable was used (24) for patients diagnosed after 1988 due to SEER updating this data item; the treatment groupings are as follows, local tumor excision (20-29), major surgery (colon (30-70); all other GI sites (30-80); cutaneous (60)), and none or local tumor destruction only (0-19). Unstaged, unknown tumor size, not otherwise specified (NOS) and unknown surgery values were categorized as missing and excluded from individual univariate analyses and the multivariate models.

Statistical analyses

The Pearson chi-squared test was used to compare baseline demographic, tumor, and treatment characteristics for patients diagnosed with GI melanoma by site and cutaneous melanoma. Three cancer-specific survival (CSS) Cox proportional hazard models were performed for patients diagnosed between 1988 and 2016; 1) model including both GI melanoma and cutaneous melanoma; 2) model including only cutaneous melanoma; 3) model including only anorectal melanoma. Cancer sites, age at diagnosis, gender, race, marital status, year of diagnosis, cancer site, SEER stage, tumor size, surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy were the variables considered for each model. Kaplan Meier plots were used to compare CSS between the anorectal and other GI melanoma sites and cutaneous melanoma. GI melanoma and cutaneous melanoma age-adjusted incidence for SEER-9 registries over time were examined using Joinpoint software (25). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The University of Iowa Human Subjects’ Office determined this study did not meet their criteria for human subjects’ research because it was limited to the analysis of deidentified data.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 872 patients with primary GI melanoma and 319,327 with cutaneous melanomas were identified between 1973 and 2016. Compared to cutaneous melanoma, patients diagnosed with GI melanoma were older (48.5% vs. 26% over 70 years), more commonly female (58% vs 45%), non-White (16% vs. 6%), and presented at higher stage (36% vs. 4% distant stage, all p <0.001; Table 1). Among GI melanomas, anus was the most common cancer site (50%) followed by rectum (34%) and other GI sites (16%; esophagus 6%, small intestine 5%, stomach 3%, and colon 2%). As compared to other GI melanoma sites, anorectal melanoma patients were more frequently female (61% vs. 44%), more likely to present with local/regional stage (67% vs. 50%), have smaller (<5 cm) tumor size (70% vs. 41%), and undergo local excision only (32% vs. <4%, all p <0.001). While in comparison to cutaneous melanomas, GI melanomas were less likely to be treated with local tumor excision only (27% vs. 82%) but were more likely to receive radiation and/or chemotherapy with or without surgery (34% vs. 4%, p <0.001).

Table 1.

Patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics between patients with primary GI melanoma and cutaneous melanoma, 1973-2016 (N=320,199)

| Cutaneous Melanoma (N=319,327) |

All GI Melanoma (N=872) |

Anorectal Melanoma (N=730) |

Other GI Melanoma Sites (N=142) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | p-value* | N | % | N | % | p-value** | ||

| Age at diagnosis | 18-49 | 102646 | 32.1 | 98 | 11.2 | <.001 | 82 | 11.2 | 16 | 11.3 | 0.94 |

| 50-69 | 134043 | 42.0 | 351 | 40.3 | 292 | 40.0 | 59 | 41.6 | |||

| 70-100 | 82638 | 25.9 | 423 | 48.5 | 356 | 48.8 | 67 | 47.2 | |||

| Sex | Female | 142144 | 44.5 | 509 | 58.4 | <.001 | 447 | 61.2 | 62 | 43.7 | <.001 |

| Male | 177183 | 55.5 | 363 | 41.6 | 283 | 38.8 | 80 | 56.3 | |||

| Race | White | 301336 | 94.4 | 736 | 84.4 | <.001 | 610 | 83.6 | 126 | 88.7 | 0.12 |

| Non-White | 17991 | 5.6 | 136 | 15.6 | 120 | 16.4 | 16 | 11.3 | |||

| Married | Yes | 164910 | 51.6 | 464 | 53.2 | 0.36 | 391 | 53.6 | 73 | 51.4 | 0.64 |

| No | 154417 | 48.4 | 408 | 46.8 | 339 | 46.4 | 69 | 48.6 | |||

| Year of diagnosis | 1973-1987 | 26710 | 8.4 | 68 | 7.8 | 0.98 | 54 | 7.4 | 14 | 9.9 | 0.37 |

| 1988-1994 | 23032 | 7.2 | 62 | 7.1 | 52 | 7.1 | 10 | 7.0 | |||

| 1995-2001 | 47839 | 15.0 | 130 | 14.9 | 109 | 14.9 | 21 | 14.8 | |||

| 2002-2008 | 93167 | 29.2 | 258 | 29.6 | 209 | 28.6 | 49 | 34.5 | |||

| 2009-2016 | 128579 | 40.3 | 354 | 40.6 | 306 | 41.9 | 48 | 33.8 | |||

| GI cancer sites | Esophagus | - | - | 54 | 6.2 | - | - | - | 54 | 38.0 | - |

| Stomach | - | - | 28 | 3.2 | - | - | 28 | 19.7 | |||

| Intestine | - | - | 40 | 4.6 | - | - | 40 | 28.2 | |||

| Colon | - | - | 20 | 2.3 | - | - | 20 | 14.1 | |||

| Rectum | - | - | 295 | 33.8 | 295 | 40.4 | - | - | |||

| Anus | - | - | 435 | 49.9 | 435 | 59.6 | - | - | |||

| SEER Summary Stage (missing=16,817) | Localized | 261025 | 86.2 | 263 | 36.4 | <.001 | 226 | 37.5 | 37 | 30.8 | 0.001 |

| Regional | 29376 | 9.7 | 202 | 27.9 | 179 | 29.7 | 23 | 19.2 | |||

| Distant | 12258 | 4.1 | 258 | 35.7 | 198 | 32.8 | 60 | 50.0 | |||

| Tumor Sizea (missing=52,318) | <2 mm/cm | 229240 | 85.8 | 89 | 16.5 | - | 87 | 18.8 | 32b | 40.5 b | <.001 |

| 2-<5 mm/cm | 26374 | 9.9 | 267 | 49.4 | 237 | 51.3 | |||||

| >=5 mm/cm | 11726 | 4.4 | 185 | 34.2 | 138 | 29.9 | 47 | 59.5 | |||

| Treatment (year diagnosis ≥1988) | Local tumor excision only | 238343 | 81.5 | 220 | 27.4 | <.0001 | 217 | 32.1 | 53b | 41.4b | <.0001 |

| Major surgery only | 24819 | 8.5 | 186 | 23.1 | 136 | 20.1 | |||||

| Radiation only | 2320 | 0.8 | 55 | 6.8 | 44 | 6.5 | 11 | 8.6 | |||

| Chemotherapy only | 1356 | 0.5 | 26 | 3.2 | 19 | 2.8 | 7 | 5.5 | |||

| Radiation & chemotherapy | 1168 | 0.4 | 27 | 3.4 | 26 | 3.9 | c | c | |||

| Local excision & chemotherapy | 2185 | 0.8 | 29 | 3.6 | 28 | 4.1 | 15b | 11.7b | |||

| Major surgery & chemotherapy | 338 | 0.1 | 47 | 5.9 | 33 | 4.9 | |||||

| Local excision & radiation | 2405 | 0.8 | 47 | 5.9 | 47 | 7.0 | c | c | |||

| Major surgery & radiation | 332 | 0.1 | 18 | 2.2 | 14 | 2.1 | c | c | |||

| Local excision & Radiation & Chemotherapy | 554 | 0.2 | 20 | 2.5 | 25b | 3.7b | c | c | |||

| Major surgery & Radiation & Chemotherapy | 79 | 0.0 | 8 | 1.0 | 28 | 4.1 | c | c | |||

| No Treatment | 18718 | 6.4 | 121 | 15.1 | 87 | 12.9 | 34 | 26.6 | |||

p-value is between Cutaneous melanoma and all GI melanoma patients

p-value is between GI melanoma sites anorectal and other sites

Tumor size is thickness in mm for cutaneous melanoma and size in cm for GI melanoma

Treatment categories had to be collapsed for the Other GI Melanoma Sites due to small numbers

Treatment categories had to be suppressed for the Other GI Melanoma Sites due to small numbers

Incidence trend

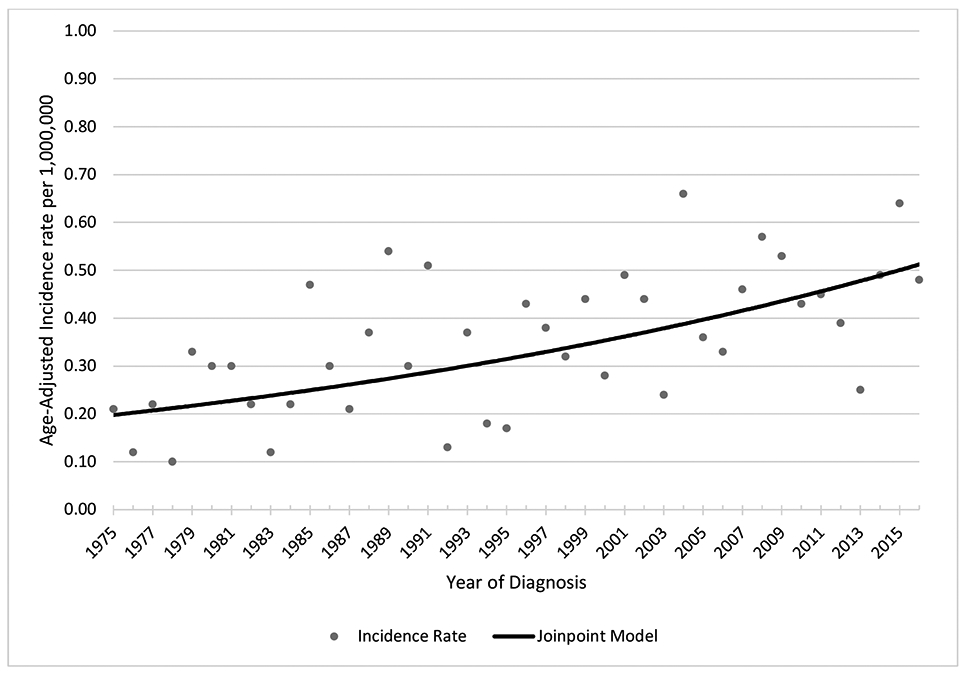

Age-adjusted incidence of GI melanoma increased from an average rate of 0.20 per million people in 1975-1979 to an average rate of 0.45 per million people in 2012-2016 (Figure 1), while cutaneous melanoma increased from an average rate of 81 per million people in 1975-1979 to 190 per million people in 2012-2016 (data not shown). A trend analysis of age-adjusted incidence between 1975 and 2016 was conducted using patients from the original SEER-9 registries. The rates increased with an average annual percent change of 1.82 for GI melanoma (p <0.05). For cutaneous melanoma, the rate increased 5.96 annually from 1975-1981, 2.27 from 1981-2005, and 0.90 from 2005-2016 (p <0.05; data not shown).

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted incidence rate of primary GI melanoma from 1975-2016, SEER 9

a Annual percentage change=1.82 significant at p<0.05; Final model 0 Joinpoints

Treatment patterns in GI melanoma

Among 226 anorectal patients with localized disease, 54% underwent local excision only, 15% major surgery only, 11% local excision plus radiation, and 11% no treatment or local tumor destruction only. For the 179 anorectal patients with regional disease, 41% underwent major surgery only, 18% local tumor excision, 13% no treatment or local tumor destruction only, and 8% received major surgery plus chemotherapy. Of the 198 anorectal patients with distant disease, 31% received radiation and/or chemotherapy only, 17% received no treatment, 14% received local tumor excision only, and 9% major surgery only, (data not shown).

In the 37 other GI melanoma site patients with localized disease, 51% received major surgery only, and 22% no treatment or local tumor destruction only, while for the 23 other GI melanoma patients with regional disease, 65% received major surgery only. Of those with distant disease, 33% received no treatment, 23% major surgery only, and 13% received radiation only (data not shown).

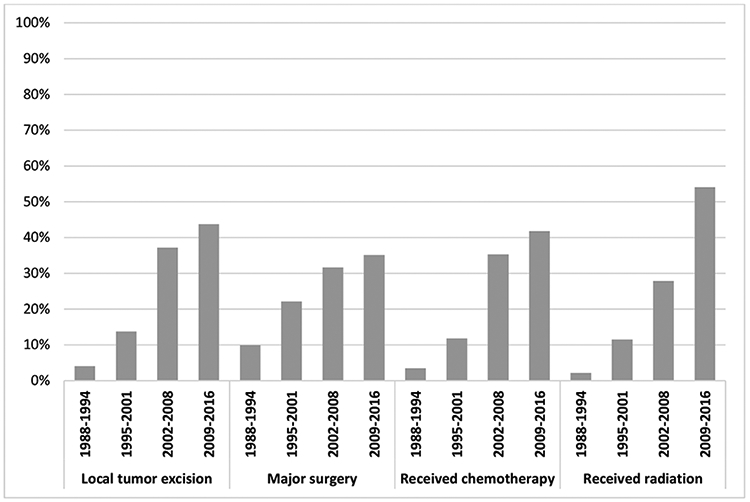

In the earlier time periods (1988-1994 and 1995-2001), major surgery with or without chemotherapy and radiation was the most common treatment approach for GI melanoma patients. While the proportion of patients undergoing major surgery increased to approximately one-third in the subsequent time periods, it became the least common treatment approach by the 2009-2016 time period when 42% received chemotherapy, 44% received local tumor excision, and 54% of patients received radiation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of GI melanoma patients who received treatment over time, by treatment type, 1988-2016.

a Treatment categories are not mutually exclusive.

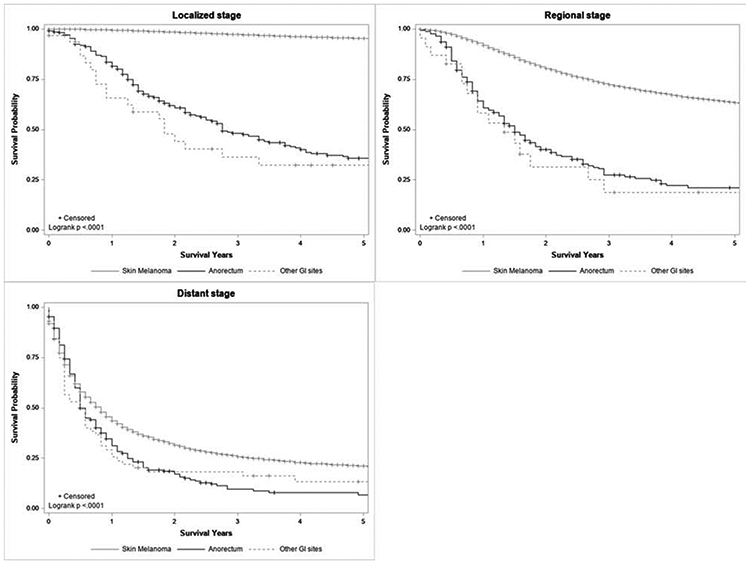

Cause-Specific Survival

For all stages, 5-year CSS differed significantly by melanoma site, with cutaneous melanoma having the highest survival (all p <0.001, Figure 3a-c). Median CSS for localized cutaneous melanoma was greater than 40 years, for regional was 21 years, and for distant was 10 months (all p <0.001). For localized (Figure 3a) and regional (Figure 3b) disease, anorectal melanoma had higher median CSS than other GI sites with a median CSS of 33 vs. 22 months and 18 vs. 16 months, respectively. For distant disease (Figure 3c), the median CSS was 6 months for both anorectal and other GI sites.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier cancer-specific survival curve comparing anorectal, other GI site, and cutaneous melanoma patients by stage, 1973-2016.

In multivariable analysis of all melanoma patients, anorectal (HR: 3.37, 2.96-3.83) and other GI site melanoma (HR: 2.10, 1.57-2.82) had worse CSS compared to cutaneous melanoma (Table 2, Model 1). CSS of all melanoma patients improved over time and survival was 28% better in 2009-2016 compared to 1988-1994. Once stratified by melanoma site, factors independently associated with cancer-specific mortality for cutaneous melanoma (Model 2) differed from those for anorectal melanoma (Model 3). For cutaneous melanoma, older age, male gender, White race, not being married, earlier year of diagnosis, higher stage, and receiving radiation and/or chemotherapy with or without surgery (vs. no treatment) were significantly associated with cancer-specific mortality. For anorectal melanomas, factors associated with cancer-specific mortality were older age, higher stage at presentation, and not receiving any form of treatment. No treatment combination had significantly better CSS compared to another.

Table 2.

Cancer-specific survival adjusted hazard ratios characterizing the association of patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics between GI melanoma and cutaneous melanoma 1988-2016 (n=243,627)

| Model 1: All Patients (GI + Cutaneous Melanoma) (N=243,627) |

Model 2: Cutaneous Melanoma Only (N=243,186) |

Model 3: Anorectal Melanoma Only (N=369) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||

| Cancer Type | Cutaneous Melanoma | 1.00 | REF | - | - | - | - |

| Anorectal Melanoma | 3.38 | (2.96, 3.85) | - | - | - | - | |

| Other GI site Melanoma | 2.36 | (1.75, 3.18) | - | - | - | - | |

| Age at diagnosis | 18-49 | 0.36 | (0.35, 0.37) | 0.41 | (0.40, 0.43) | 0.62 | (0.40, 0.95) |

| 50-69 | 0.54 | (0.53, 0.56) | 0.58 | (0.57, 0.60) | 1.04 | (0.78, 1.38) | |

| 70-100 | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | |

| Sex | Female | 0.66 | (0.65, 0.68) | 0.68 | (0.66, 0.70) | 0.94 | (0.72, 1.23) |

| Male | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | |

| Race | White | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF |

| Non-White | 0.75 | (0.69, 0.81) | 0.73 | (0.67, 0.79) | 1.13 | (0.82, 1.57) | |

| Married | Yes | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF |

| No | 1.09 | (1.06, 1.12) | 1.08 | (1.05, 1.11) | 0.92 | (0.70, 1.21) | |

| Year of diagnosis | 1988-1994 | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF |

| 1995-2001 | 0.85 | (0.80, 0.90) | 0.85 | (0.81, 0.90) | 1.17 | (0.66, 2.05) | |

| 2002-2008 | 0.82 | (0.77, 0.87) | 0.79 | (0.74, 0.83) | 1.04 | (0.62, 1.77) | |

| 2009-2016 | 0.72 | (0.68, 0.77) | 0.67 | (0.63, 0.71) | 0.73 | (0.43, 1.25) | |

| SEER Summary Stage | Localized | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF |

| Regional | 6.96 | (6.75, 7.17) | 3.61 | (3.48, 3.74) | 1.53 | (1.08, 2.17) | |

| Distant | 19.30 | (18.27, 20.40) | 10.36 | (9.77, 10.99) | 3.02 | (2.04, 4.48) | |

| Tumor Sizea | <2 mm/cm | - | - | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF |

| 2-<5 mm/cm | - | - | 3.14 | (3.03, 3.26) | 1.21 | (0.85, 1.72) | |

| >=5 mm/cm | - | - | 4.02 | (3.85, 4.20) | 1.23 | (0.82, 1.83) | |

| Treatment | No Treatment | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF |

| Major surgery only | 0.94 | (0.84, 1.04) | 0.81 | (0.73, 0.91) | 0.27 | (0.14, 0.53) | |

| Major surgery & radiation | 1.95 | (1.57, 2.43) | 1.58 | (1.26, 1.99) | 0.30 | (0.13, 0.72) | |

| Local excision & chemotherapy | 1.73 | (1.54, 1.95) | 1.46 | (1.30, 1.65) | 0.33 | (0.15, 0.74) | |

| Local excision & radiation | 1.67 | (1.48, 1.87) | 1.27 | (1.13, 1.44) | 0.34 | (0.15, 0.73) | |

| Local excision & radiation & chemotherapy | 3.16 | (2.72, 3.67) | 2.70 | (2.32, 3.16) | 0.35 | (0.15, 0.83) | |

| Chemotherapy only | 2.28 | (1.70, 3.05) | 3.20 | (2.34, 4.39) | 0.36 | (0.15, 0.88) | |

| Local tumor excision only | 0.68 | (0.62, 0.75) | 0.64 | (0.58, 0.71) | 0.40 | (0.21, 0.75) | |

| Major surgery & chemotherapy | 2.34 | (1.95, 2.81) | 1.87 | (1.54, 2.27) | 0.52 | (0.26, 1.05) | |

| Radiation only | 4.07 | (3.21, 5.15) | 5.74 | (4.44, 7.41) | 0.53 | (0.24, 1.14) | |

| Radiation & chemotherapy | 3.45 | (2.49, 4.79) | 4.27 | (2.94, 6.21) | 0.53 | (0.23, 1.23) | |

| Major surgery & radiation & chemotherapy | 2.32 | (1.62, 3.33) | 2.68 | (1.85, 3.89) | b | b | |

Tumor size is thickness in mm for cutaneous melanoma and size in cm for GI melanoma

Treatment category “Major surgery and radiation and chemotherapy” was excluded from Model 3 due to small numbers

Discussion.

In this updated SEER population-based analysis, we observed that primary GI melanomas continue to represent an uncommon entity with a poor prognosis. Despite its rarity, its incidence has increased over the past four decades in the United States. The current study found that overall, compared to cutaneous melanomas, GI melanomas were associated with older patients, female gender, higher stage at presentation, and more likely to be treated with chemotherapy and radiation. In the GI tract, anorectal melanomas were most common and tended to occur in women, present as smaller tumors and at lower stages compared to other GI melanomas. Furthermore, patients with anorectal melanoma who underwent local excision with chemotherapy and/or radiation had a similar CSS compared to those patients who only underwent major surgery. On stage-wise comparisons local and regional anorectal melanomas had a worse survival compared to patients with cutaneous melanoma, while patients with melanomas from other GI sites had the worst prognosis. Patients with metastatic melanoma regardless of location had a dismal prognosis with the median survival being less than a year.

The increasing incidence of GI melanoma and associated demographic factors found in our analyses are consistent with previous studies (15). In an earlier SEER analysis from 1973-2003 that compared the age-adjusted rates of esophageal and anorectal melanoma to cutaneous melanoma, it was found that the rates of both cutaneous and anorectal melanoma had increased by 1.4 and 1.8 fold, respectively and that whereas cutaneous melanoma were more frequent in males, GI melanoma was more common in females (16). In our current analysis we observed that the GI melanoma incidence had increased 2.3 fold during the study period and that 58% of GI melanoma patients were female. A more recent SEER study from 1973 to 2011 by Chen et al also found that anorectal melanoma incidence was increasing and confirmed higher incidence in females (26). While the cause for the higher rates in females remains unclear, the increase in incidence of GI melanomas over the past four decades may be attributable to the increased screening of colorectal cancer with endoscopy and/or the overall use of cross-sectional imaging modalities.

The treatment patterns in the current study cohort varied among melanoma sites and were reflective of the presentation stage at each site and consistent with previous analyses of national cohorts (26, 27). While local tumor excision was performed in the vast majority of cutaneous melanoma cases, it was used in less than half anorectal melanomas, and rarely in other GI sites where the applicability of local excision is very limited due to technical and anatomical considerations. Chemotherapy and radiation, which are infrequently used in cutaneous melanoma, were used in approximately 40% of patients diagnosed with GI melanomas between 2009 and 2016. This distribution of treatment modalities is similar to what was found in a National Cancer Database (NCDB) study where 92% of cutaneous melanomas received surgery only and 36% of mucous membrane melanomas received radiation or chemotherapy with or without surgery (28). Similarly a previous SEER study found that 19% of anorectal melanomas diagnosed between 1973 and 2011 received radiation, which during our study period had slightly increased, with 22% of anorectal patients receiving radiation (26).

After controlling for available confounders, we observed that compared to cutaneous melanoma, anorectal and other GI site melanoma patients had a 3.4- and 2.1-times increased risk of death, respectively. Studies using 1973-2004 SEER data and 1985-1994 NCDB data found similar disease specific survival patterns (28, 29). Case reports and single institution series have investigated the feasibility of using immunotherapy in the treatment of mucosal melanoma, including anorectal melanoma (22, 23, 30-32). In this study, disease specific survival for GI melanoma increased over time and was highest from 2009-2016, which coincides with the introduction of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved immunotherapies for cutaneous melanoma (23). It is possible the use of these therapies for GI melanomas accounted for the observed improvement in disease specific survival (23). These agents may therefore represent promising treatment modalities for GI melanomas, which due to their late presentation may have limited surgical treatment options.

Abdominoperineal resection (APR) was initially considered to be the treatment standard for anorectal melanoma (33, 34). However, both small institutional series and a recent retrospective analysis of the NCDB found no significant survival difference between APR and wide local excision (WLE), which is usually associated with lower perioperative morbidity and avoids a permanent colostomy (27, 35, 36). Furthermore, single center studies of local excision combined with adjuvant radiation have shown that the regimen is well tolerated and has adequate local-regional disease control (21, 37). Ballo et al achieved 74% and 84% 5-year local and regional nodal control in 23 patients after local excision, nodal dissection, and adjuvant radiation [38], while Kelly et al reported a 5-year local control rate of 82% among 54 patients undergoing similar treatment [28]. In this study, after controlling for available variables, we also found no significant difference in survival between local excision only and major resection only. This is in line with the current recommendations of WLE for local disease when complete resection is possible with consideration of lymphadenectomy, adjuvant radiation and/or chemotherapy for regional disease.

Limitations of this study include the lack of recurrence information for cancer patients that are not collected by SEER, which is an important consideration when comparing oncologic outcomes by surgical treatment. We were also unable to account for metastatic burden and specific tumor locations, e.g. esophagus and stomach, which may affect treatment decisions. Additionally, the higher risk of death associated with chemotherapy and radiation in cutaneous melanoma in the multivariate models suggests that we were unable to completely control for extent of disease, comorbidities, and other factors that lead to a worse outcome. The limited number of primary GI melanoma patients due to the rarity of the disease reduced the potential stratifications that could be done with these patients, such as stratifying other GI melanoma sites further. Despite the high quality of SEER data, radiation and chemotherapy are sometimes underreported due to treatment increasingly being received outside of the hospital setting. Nonetheless, SEER data provide detailed information about cancer stage, disease specific survival, and treatment at time of diagnosis representing diverse geographical regions (38). Our study is among the few population-based studies that characterizes the epidemiology of all primary GI melanoma sites, their treatment, and potential prognostic factors compared to cutaneous melanoma patients. Furthermore, this is the only GI melanoma SEER study that includes chemotherapy data, which allowed us to compare different first course treatment combinations of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation.

Conclusion

Primary GI melanomas, the most common of which are in the anorectal region, are rare malignancies with poor prognosis that have had an increasing incidence over the past four decades. The low survival rates may be related to advanced disease at presentation and lack of standardized treatments. The improved survival observed in the recent years coincides with the introduction of immunotherapy regimens for cutaneous melanoma, suggesting the use of these biologic agents may also have had a beneficial impact in the treatment of primary GI melanomas. Further studies are warranted to investigate the optimal management of patients affected by this rare disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH/NCI contract number HHSN261201800012I/ HHSN26100001 (MEC, ARK); NIH grant T32 CA 148062 (XG), and NIH/NCI P30 CA086862 (MEC, ARK).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: None Declared

A portion of these data were presented at the annual North American Association of Central Cancer Registries June 2018 in Pittsburgh, PA.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. Atlanta: 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lens M, Bataille V, Krivokapic Z Melanoma of the small intestine. The Lancet Oncology 2009:10:516–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenney B, Dotto J, Homer R, Shafi N, Davydova L Primary Malignant Melanoma of the Transverse Colon: Report of a Case and Review of the Literature. International Journal of Surgical Pathology 2007:15:401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li W-X, Wei Y, Jiang Y, Liu Y-L, Ren L, et al. Primary colonic melanoma presenting as ileocecal intussusception: Case report and literature review. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2014:20:9626–9630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atmatzidis KS, Pavlidis TE, Papaziogas BT, Papaziogas TB Primary Malignant Melanoma of the Small Intestine: Report of a Case. Surgery Today 2002:32:831–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amar A, Jougon J, Edouard A, Laban P, Marry JP, et al. [Primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine]. Gastroenterologie clinique et biologique 1992:16:365–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jelincic Z, Jakic-Razumovic J, Petrovic I, Cavcic AM, Unusic J, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the stomach. Tumori 2005:91:201–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuchter LM, Green R, Fraker D Primary and metastatic diseases in malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Current Opinion in Oncology 2000:12:181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel JK, Didolkar MS, Pickren JW, Moore RH Metastatic pattern of malignant melanoma. The American Journal of Surgery 1978:135:807–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werdin C, Limas C, Knodell RG Primary malignant melanoma of the rectum. Evidence for origination from rectal mucosal melanocytes. Cancer 1988:61:1364–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicholson AG, Cox PM, Marks CG, Cook MG Primary malignant melanoma of the rectum. Histopathology 1993:22:261–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Pava S, Nigogosyan G, Pickren JW, Cabrera A Melanosis of the esophagus. Cancer 1963:16:48–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karamchandani DM, Patil DT, Goldblum JRGI Tract Tumors With Melanocytic Differentiation. Advances In Anatomic Pathology 2013:20:398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinstock MA Epidemiology and prognosis of anorectal melanoma. Gastroenterology 1993:104:174–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cagir B, Whiteford MH, Topham A, Rakinic J, Fry RD Changing epidemiology of anorectal melanoma. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum 1999:42:1203–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coté TR, Sobin LH Primary melanomas of the esophagus and anorectum: epidemiologic comparison with melanoma of the skin. Melanoma Research 2009:19:58–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garbe C, Eigentler TK Diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous melanoma: state of the art 2006*. Melanoma Research 2007:17:117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsao H, Atkins MB, Sober AJ Management of Cutaneous Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2004:351:998–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nam S, Kim CW, Baek SJ, Hur H, Min BS, et al. The clinical features and optimal treatment of anorectal malignant melanoma. Annals of Surgical Treatment and Research 2014:87:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moozar KL, Wong CS, Couture J Anorectal malignant melanoma: treatment with surgery or radiation therapy, or both. Canadian Journal of Surgery 2003:46:345–349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly P, Zagars GK, Cormier JN, Ross MI, Guadagnolo BA Sphincter-sparing local excision and hypofractionated radiation therapy for anorectal melanoma. Cancer 2011:117:4747–4755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eggermont AMM, Maio M, Robert C Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Melanoma Provide the Cornerstones for Curative Therapies. Seminars in Oncology 2015:42:429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim BJ, Jang HJ, Kim HS, Kim JH Current Status of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Journal of Cancer 2017:8:1460–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SEER Appendix C: Site Specific Coding Modules. 2018.

- 25.Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.6.0.0 - February 2018. Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen H, Cai Y, Liu Y, He J, Hu Y, et al. Incidence, Surgical Treatment, and Prognosis of Anorectal Melanoma From 1973 to 2011: A Population-Based SEER Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016:95:e2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fields AC, Goldberg J, Senturk J, Saadat LV, Jolissaint J, et al. Contemporary Surgical Management and Outcomes for Anal Melanoma: A National Cancer Database Analysis. Annals of surgical oncology 2018:25:3883–3888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang AE, Karnell LH, Menck HR The National Cancer Data Base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma: a summary of 84,836 cases from the past decade. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Cancer 1998:83:1664–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheung MC, Perez EA, Molina MA, Jin X, Gutierrez JC, et al. Defining the role of surgery for primary gastrointestinal tract melanoma. J Gastrointest Surg 2008:12:731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schaefer T, Satzger I, Gutzmer R Clinics, prognosis and new therapeutic options in patients with mucosal melanoma: A retrospective analysis of 75 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017:96:e5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satzger I, Kuttler U, Volker B, Schenck F, Kapp A, et al. Anal mucosal melanoma with KIT-activating mutation and response to imatinib therapy--case report and review of the literature. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland) 2010:220:77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fox MC, Lao CD, Schwartz JL, Frohm ML, Bichakjian CK, et al. Management options for metastatic melanoma in the era of novel therapies: A primer for the practicing dermatologist. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2013:68:13.e11–13.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brady MS, Kavolius JP, Quan SH Anorectal melanoma. A 64-year experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. Dis Colon Rectum 1995:38:146–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abbas JS, Karakousis CP, Holyoke ED Anorectal melanoma: clinical features, recurrence and patient survival. Int Surg 1980:65:423–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pessaux P, Pocard M, Elias D, Duvillard P, Avril MF, et al. Surgical management of primary anorectal melanoma. Br J Surg 2004:91:1183–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thibault C, Sagar P, Nivatvongs S, Ilstrup DM, Wolff BG Anorectal melanoma--an incurable disease? Dis Colon Rectum 1997:40:661–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ballo MT, Gershenwald JE, Zagars GK, Lee JE, Mansfield PF, et al. Sphincter-sparing local excision and adjuvant radiation for anal-rectal melanoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2002:20:4555–4558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF Overview of the SEER-Medicare Data. Medical Care 2002:40:IV-3–IV-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]